Towards a Structured Approach to Advance Sustainable Water Management in Higher Education Institutions: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- -

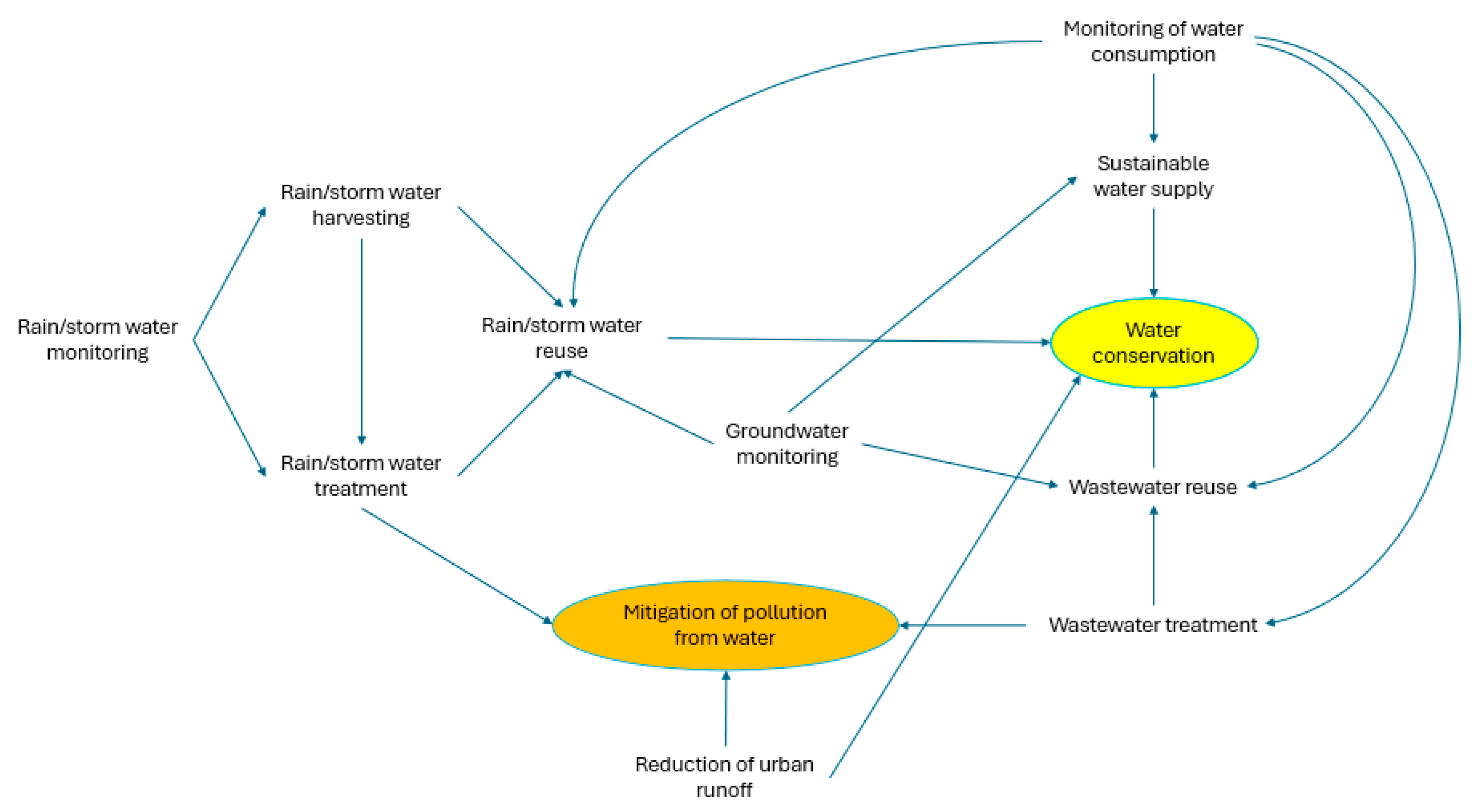

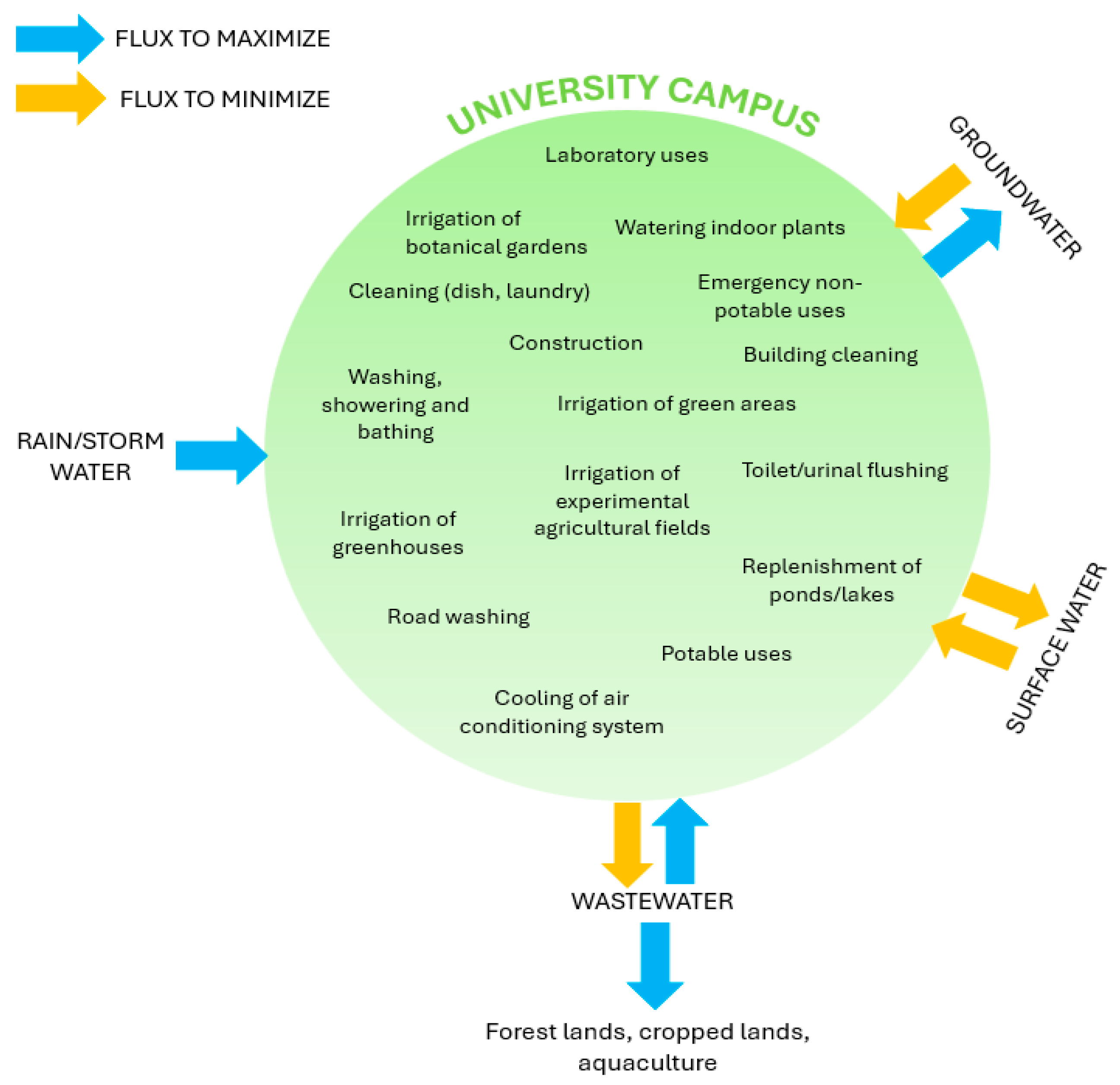

- Water conservation.

- -

- Mitigation of pollution due to contaminated water release.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Identified Core Actions for Sustainable Water Management in University Campuses

- (a)

- Monitoring of consumed water (Section 3.2.1),

- (b)

- Monitoring of rain and storm waters (Section 3.2.2),

- (c)

- Harvesting of rain and storm waters (Section 3.2.3),

- (d)

- Water reuse from rain and storm waters (Section 3.2.3),

- (e)

- Treatment of rain and storm waters (Section 3.2.4),

- (f)

- Reduction in urban runoff (Section 3.2.5),

- (g)

- Wastewater treatment (Section 3.2.6),

- (h)

- Water reuse from treated wastewater (Section 3.2.6),

- (i)

- Monitoring of groundwater (Section 3.2.7),

- (j)

- Sustainable water supply (Section 3.2.8).

3.2. Analysis of Sustainable Water Management Measures by HEIs Emerged from the Literature

3.2.1. Monitoring of Water Consumption

- (1)

- The energy sources employed for extraction, pumping and purification,

- (2)

- The water source and water quality policies determining the intensity of the purification treatments required,

- (3)

- The height of buildings,

- (4)

- The amount of water consumed,

- (5)

- The amount of hot water consumed.

- -

- Drinking,

- -

- Cooking in universities’ kitchens,

- -

- Research laboratories,

- -

- Gardening,

- -

- Washing (e.g., hand washing in washbasins),

- -

- Sanitation (e.g., toilet and urinal flushing),

- -

- Cleaning,

- -

- Bathing,

- -

- Dish washing.

- -

- A total of 72% for personal use, such as water used in toilets, urinals, washbasins, showers and fountains of which toilet water consumption contributes 58% on total personal use,

- -

- A total of 19% for cleaning activities,

- -

- A total of 9% for other water consumptions.

- (a)

- Ensuring quality standards of distributed water,

- (b)

- Guaranteeing reliability of water supply,

- (c)

- Avoiding water wastages (e.g., by detecting leakages),

- (d)

- Maintaining water infrastructure,

- (e)

- Reducing the cost of water and of electricity used for water pumping,

- (f)

- Engaging consumers in water conservation practices.

3.2.2. Rain and Storm Water Monitoring

Quality Monitoring of Rain and Storm Waters

Quantity Monitoring of Rain and Storm Waters

3.2.3. Rain and Storm Water Harvesting and Reuse

3.2.4. Rain and Storm Water Treatment

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- Floating CWs built up in the following:

- (4)

- Infiltration systems, such as:

- -

- -

- Seepage wells [241],

- -

- Biopower infiltration units [199],

- -

- -

- -

- Biofilters [214,226,238], referred to as biofiltration cells in Grover et al. [210] or as eco-biofilters in Maniquiz-Redillas and Kim [217] and in Maniquiz-Redillas et al. [100], including tree box filters as reported in Geronimo et al. [209], Haque et al. [212] and Houle et al. [213] and rain gardens [53,98,99,101,103,132,137,163,169,186,197,199,200,204,206,207,211,212,216,223,229,231,232,234,235,241,243,302],

- -

- -

- Planter box [228],

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Bioinfiltration ponds [220],

- -

- Bioretention curb extension [225],

- -

- Bioretention planter [225],

- -

- Infiltration planter [212],

- -

- -

- Infiltration wadis [191],

- -

- Infiltration shallow pools [241],

- -

- (5)

- Storage systems such as:

- (6)

3.2.5. Reduction in Urban Runoffs

- -

- -

- Stormwater infiltration systems [30,53,71,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,124,132,137,149,163,165,169,186,191,195,197,198,199,200,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,219,220,221,223,224,225,226,228,229,231,232,234,235,236,237,238,239,241,243,264,301,302,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,332,333,334],

- -

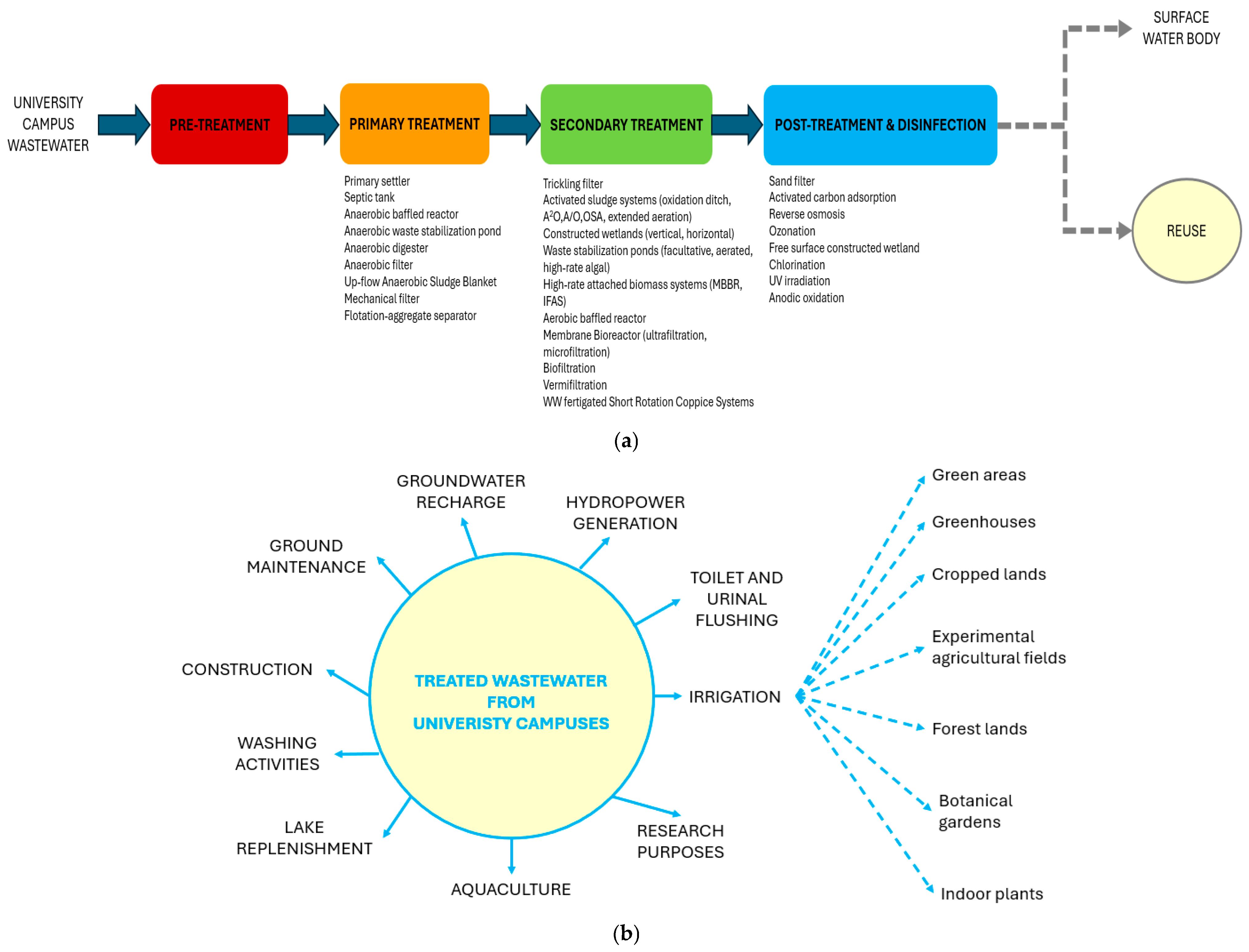

3.2.6. Treatment and Reuse of University Campus Wastewaters

- (a)

- When the university campus is located in places where a connection to a sewer system could result physically and/or economically unfeasible, by preventing the direct discharge of wastewater pollutants into the environment [337],

- (b)

- When the university campus is close to gardens and/or agricultural fields [338], by increasing the chances for water reuse and resource recovery,

- (c)

- When the centralized wastewater treatment plant eventually serving the university campus along with other wastewater streams is under-sized, by reducing the pollutant load to the same facility.

3.2.7. Groundwater Monitoring

3.2.8. Sustainable Water Supply

- (a)

- Installing a reverse-driven centrifugal pump—otherwise known as Pump as Turbine—for water supply, which contextually produces energy from the gravitational flow of supplied water; such produced energy can then be used to pump water at various outlets in the building,

- (b)

- Implementing wood stave pipelines, which makes the water supply system more sustainable given the low-energy material employed, especially if wood is obtained from local forests, compared to steel.

3.3. Summary of Key Findings and Critical Considerations

- Measures minimizing the release of micropollutants in wastewater. With the objective of preventing pollution due to release of contaminated water from university campuses, one topic that did not emerge from this review is the issue of micropollutant release through HEIs’ wastewater in the environment. Among the typical micropollutants released in wastewater that can be input into the water cycle through the human usage of PPCPs, such as detergents for the cleaning of toilets and other washroom accessories as well as soaps used for personal hygiene, there are several molecules that are persistent and therefore cannot be removed from wastewater through conventional treatment technologies, nor undergo significant degradation in the environment. Specific energy-demanding treatment processes would need to be installed [457]. If not removed from wastewaters, these molecules accumulate in bodies of water [457], thereby potentially threatening fish species and humans [458]. This problem has become such a concern that the recast of urban wastewater treatment directive in the European Union has prescribed quaternary treatment for the removal of a selected list of micropollutants from urban wastewaters [459]. The input of persistent micropollutants into water bodies by HEIs can be particularly concerning given the fact that people tend to spend a large portion of the day in them and hygiene measures require, in most cases, that toilets and washbasins be cleaned daily, contrary to what happens to domestic household infrastructures, besides frequent handwashing [460]. Therefore, preventing water micro-pollution is key to reducing the workload of wastewater treatment plants and safeguarding the environment and can be considered a core action for water sustainability in HEIs. Specific actions that can be undertaken by HEIs are as follows:

- (i)

- Sensitizing students and academic staff regarding the use of soap for handwashing, discouraging usages beyond the normal need;

- (ii)

- Sensitizing cleaning staff regarding proper usage of detergents for toilet and washbasin cleaning, avoiding overuse;

- (iii)

- (iv)

- Teaching HEIs’ staff and students about the environmental and health hazards of the micropollutants typically contained in PPCPs;

- (v)

- Researching and teaching to increase the understanding and awareness of the side effects of micropollutants on the environment and on human health;

- (vi)

- Researching and teaching about sustainable technologies for micropollutant removal from wastewater.

- Measures for water pollution prevention from waste mismanagement. Besides micropollutants, another source of water pollution in HEIs can derive from waste mismanagement. HEIs tend to produce various amounts of organic waste from the canteen leftovers of various sources. If mismanaged, percolate generated by stormwater infiltration into organic waste can infiltrate underground, thus contaminating underground water reservoirs [463]. Mismanaged waste can also in some cases be carried by runoffs to surface water bodies, thereby compromising the living organisms inhabiting them and their eventual human consumption [464,465]. Contamination of stormwater by mismanaged waste in a university campus was studied only by Akpanke et al. [143]. The issue of stormwater contamination by mismanaged waste highlights the interconnection between water sustainability and other sustainability actions within HEIs: water sustainability cannot be achieved without sustainability actions on other important items, such as waste management.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABR | Anaerobic Baffled Reactor |

| AF | Anaerobic Filter |

| AO | Anodic Oxidation |

| AS | Activated Sludge |

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CW | Constructed Wetland |

| DWTR | Drinking Water Treatment Residual |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GR | Green Roof |

| HEI | Higher Education Institutions |

| HRAP | High-Rate Algal Pond |

| IFAS | Integrated Fixed-film Activated Sludge |

| MBBR | Moving Bed Biofilm Reactors |

| MBR | Membrane Bioreactor |

| NbS | Nature-based Solutions |

| OSA | Oxic-Settling-Anoxic/anaerobic |

| PAH | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon |

| PPCP | Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Product |

| RWH | Rainwater harvesting |

| SWH | Stormwater harvesting |

| SWM | Sustainable Water Management |

| ST | Septic Tank |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solid |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solid |

| UASB | Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket |

| wfSRC | Wastewater fertigated Short Rotation Coppice systems |

| WSP | Waste Stabilization Pond |

References

- Cosgrove, W.J.; Loucks, D.P. Water Management: Current and Future Challenges and Research Directions. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 4823–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization UNITED NATIONS WORLD. WATER DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2023: Partnerships and Cooperation for Water; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gawel, E.; Bedtke, N. Economic Requirements and Instruments for Sustainable Urban Water Management. In Urban Water Management for Future Cities. Future City; Köster, S., Reese, M., Zuo, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-01488-9. [Google Scholar]

- Braden, J.B.; Van Ierland, E.C. Balancing: The Economic Approach to Sustainable Water Management. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 39, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Economic Analysis of Sustainable Water Use: A Review of Worldwide Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clothier, B.; Jovanovic, N.; Zhang, X. Reporting on Water Productivity and Economic Performance at the Water-Food Nexus. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 237, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrijos, V.; Soto, M.; Calvo Dopico, D. SOSTAUGA Project: Reduction of Water Consumption and Evaluation of Potential Uses for Endogenous Resources. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1391–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.T.; Nguyen, D.C.; Han, M.; Kim, M.; Park, H. Rainwater as a Source of Drinking Water: A Resource Recovery Case Study from Vietnam. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 39, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, A.D.; Nguyen, V.A.; Han, M. Benefit of the Drinking Water Supply System in Office Building by Rainwater Harvesting: A Demo Project in Hanoi, Vietnam. Environ. Eng. Res. 2013, 18, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.P.; Jackson, S.; Tharme, R.E.; Douglas, M.; Flotemersch, J.E.; Zwarteveen, M.; Lokgariwar, C.; Montoya, M.; Wali, A.; Tipa, G.T.; et al. Understanding Rivers and Their Social Relations: A Critical Step to Advance Environmental Water Management. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2019, 6, e1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. The Role of Governance Modes and Meta-Governance in the Transformation towards Sustainable Water Governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 91, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, L. Reconnecting People and Water: Public Engagement and Sustainable Urban Water Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781315851679. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavon, M.; Giurea, R.; Ionescu, G.; Magaril, E.; Cristina, E. Agro-Tourism Structures, SARS-CoV-2: The Role of Water. Matec Web Conf. 2022, 354, 00070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogardi, J.J.; Dudgeon, D.; Lawford, R.; Flinkerbusch, E.; Meyn, A.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Vielhauer, K.; Vörösmarty, C. Water Security for a Planet under Pressure: Interconnected Challenges of a Changing World Call for Sustainable Solutions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankareddy, S.; Dorfleitner, G.; Zhang, L.; Ok, Y.S. Embedding Sustainability in Higher Education Institutions: A Review of Practices and Challenges. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 17, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Statistics Division. United Nations The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations Statistics Division: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Abubakar, I. An Integrated Approach to Achieving Campus Sustainability: Assessment of the Current Campus Environmental Management Practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, M.R.; John, V.M. Towards More Sustainable Universities: A Critical Review and Reflections on Sustainable Practices at Universities Worldwide. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 56, 284–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauen, T.R.S.; Lezana, Á.G.R.; da Silva, V. Environmental Management: An Overview in Higher Education Institutions. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 3682–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, A.T.; Kovalski, M.L.; Regina, V.B.; Riva, P.B.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Galvão, C.B.; Takahashi, B.T. Environmental Education for Sustainable Management of the Basins of the Rivers Pirapó, Paranapanema III and Parapanema IV. Braz. J. Biol. 2015, 75, S137–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, E.; Annis, A.; Apollonio, C.; Pumo, D.; Urru, S.; Viola, F.; Deidda, R.; Pelorosso, R.; Petroselli, A.; Tauro, F.; et al. Multilayer Blue-Green Roofs as Nature-Based Solutions for Water and Thermal Insulation Management. Hydrol. Res. 2022, 53, 1129–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarov, A.S.; Semenescu, A. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Romanian Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) within the SDGs Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Blacky, T.; Zoubek, M. Comparison of a Watercooler and Other Alternatives in Terms of Their Environmental Impacts Using the Lca Method. MM Sci. J. 2023, 2023, 6582–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherianfar, M.; Dolati, A. Strategies for Social Participation of Universities in the Local Community; Perspectives of Internal and External Beneficiaries. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2023, 15, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Barth, M.; von Wehrden, H. The Patterns of Curriculum Change Processes That Embed Sustainability in Higher Education Institutions. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1579–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, S.; Logan, L.; Willison, D.; Bain, R.; Roberts, J.; Mitchell, I.; Yarr, R. Reflections on Developing a Collaborative Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Embedding Education for Sustainable Development into Higher Education Curricula. Emerald Open Res. 2021, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurea, R.; Carnevale Miino, M.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C. Approaching Sustainability and Circularity along Waste Management Systems in Universities: An Overview and Proposal of Good Practices. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1363024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Borreguero, G.; Maestre-Jiménez, J.; Mateos-Núñez, M.; Naranjo-Correa, F.L. Water from the Perspective of Education for Sustainable Development: An Exploratory Study in the Spanish Secondary Education Curriculum. Water 2020, 12, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourredine, H.; Barjenbruch, M.; Million, A.; El Amrani, B.; Chakri, N.; Amraoui, F. Linking Urban Water Management, Wastewater Recycling, and Environmental Education: A Case Study on Engaging Youth in Sustainable Water Resource Management in a Public School in Casablanca City, Morocco. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grehl, E.; Kauffman, G. THE UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE RAIN GARDEN: ENVIRONMENTAL MITIGATION OF A BUILDING FOOTPRINT. J. Green Build. 2007, 2, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiocchi, R.; Adami, L.; Rada, E.C.; Schiavon, M. Towards Context-Independent Indicators for an Unbiased Assessment of Environmental Sustainability in Higher Education: An Application to Italian Universities. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Rêgo, J.R.S.; Meiguins de Lima, A.M. A Percepção Dos Alunos Do Ensino Fundamental Sobre o Uso Da Água Consumida No Município de Belém-PAThe Perception of Fundamental Education Students on the Use of Consumed Water in the County of Belém-PALa Percepción de Los Alumnos de La Enseñanza. REMEA-Rev. Eletrônica do Mestr. em Educ. Ambient. 2018, 35, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehmaa, A.; Karvinen, M.; Keskinen, M. Building a More Sustainable Society? A Case Study on the Role of Sustainable Development in the Education and Early Career of Water and Environmental Engineers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, L.L.; Marder, L.; Benvenuti, T.; Bernardes, A.M. Electrodialysis Applied to the Treatment of an University Sewage for Water Recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, T.B.; Zerwes, F.V.; Kist, L.T.; Machado, Ê.L. Constructed Wetland and Photocatalytic Ozonation for University Sewage Treatment. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 63, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Su, X.; Tong, L.; ÙZhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Davies. A Warning from an Ancient Oasis: Intensive Human Activities Are Leading to Potential Ecological and Social Catastrophe. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.; Bachega, S.J.; Tavares, D.M. Framework Proposal for the Environmental Impact Assessment of Universities in the Context of Green IT. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.; Sousa, V.; Silva, C.M. Methodology for Estimating Energy and Water Consumption Patterns in University Buildings: Case Study, Federal University of Roraima (UFRR). Heliyon 2021, 7, e08642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novita, E.; Andriyani, I.; Hartiningsih, E.S.; Pradana, H.A. Characterisation of Laboratory Wastewater for Planning Wastewater Treatment Plants in a University Campus in Indonesia. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2022, 28, S45–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Park, J. Exploring Circular Water Options for a Water-Stressed City: Water Metabolism Analysis for Paju City, South Korea. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; Drechsel, P.; Jiménez Cisneros, B.; Kim, Y.; Pramanik, A.; Mehta, P.; Olaniyan, O. Global and Regional Potential of Wastewater as a Water, Nutrient and Energy Source. Nat. Resour. Forum 2020, 44, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, U.; Vahmani, P.; Jones, A.D. Quantifying the City-Scale Impacts of Impervious Surfaces on Groundwater Recharge Potential: An Urban Application of WRF–Hydro. Water 2022, 14, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Delkash, M.; Tajrishy, M. Evaluation of Permeable Pavement Responses to Urban Surface Runoff. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 187, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, J.M.F.; Marques, D.G.; Campos, V.; Nolasco, M.A. Analysis of the Water Indicators in the UI GreenMetric Applied to Environmental Performance in a University in Brazil. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiocchi, R.; Ragazzi, M.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C. Critical Analysis of the GreenMetric World University Ranking System: The Issue of Comparability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green Supply Chain Management: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A Comparative Analysis; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 126, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, S.A.; Turco, M.; Principato, F.; Piro, P. Hydrological Effectiveness of an Extensive Green Roof in Mediterranean Climate. Water 2019, 11, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keffala, C.; Jmii, G.; Mokhtar, A.; Zouhir, F.; Liady, N.D.; Tychon, B.; Jupsin, H. Diagnosis and Assessment of a Combined Oxylag and High Rate Algal Pond (COHRAP) for Sustainable Water Reuse: Case Study of the University Campus in Tunisia. Water 2025, 17, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannina, G.; Alduina, R.; Badalucco, L.; Barbara, L.; Capri, F.C.; Cosenza, A.; Di Trapani, D.; Gallo, G.; Laudicina, V.A.; Muscarella, S.M.; et al. Water Resource Recovery Facilities (WRRFs): The Case Study of Palermo University (Italy). Water 2021, 13, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, A.I. Constructed Wetlands for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment in Hot and Arid Climates: Opportunities, Challenges and Case Studies in the Middle East. Water 2020, 12, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahho, M.; Vale, B. A Demonstration Building Project: Promoting Sustainability Values. J. Green Build. 2020, 15, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Wu, L.; She, N.; Lucas, W.; Li, B. Innovative Design of a Suite of Low Impact Development Facilities in Civil Structure Experimental Building Complex. In Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 859–866. [Google Scholar]

- University Indonesia Green Metric Ranking System. Available online: https://greenmetric.ui.ac.id/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Lin, S.; Chu, W.; Liu, A. Characteristics of Dissolved Organic Matter in Two Alternative Water Sources: A Comparative Study between Reclaimed Water and Stormwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Poly Industries. What Is the Difference Between Stormwater and Rainwater? Available online: https://nationalpolyindustries.com.au/2018/06/14/what-is-the-difference-between-stormwater-and-rainwater/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Parker, E.A.; Grant, S.B.; Sahin, A.; Vrugt, J.A.; Brand, M.W. Can Smart Stormwater Systems Outsmart the Weather? Stormwater Capture with Real-Time Control in Southern California. ACS Environ. Sci. Technol. Water 2022, 2, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Österlund, H.; Marsalek, J.; Viklander, M. The Pollution Conveyed by Urban Runoff: A Review of Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 136125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, K.; Bondelind, M.; Karlsson, A.; Karlsson, D.; Sokolova, E. Hydrodynamic Modelling of the Influence of Stormwater and Combined Sewer Overflows on Receiving Water Quality: Benzo(a)Pyrene and Copper Risks to Recreational Water. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bdour, A.; Hejab, A.; Almakhadmah, L.; Hawwa, M. Management Strategies for the Efficient Energy Production of Brackish Water Desalination to Ensure Reliability, Cost Reduction, and Sustainability. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2023, 9, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, A.; Piotrowska, B.; Słyś, D. Greywater as an Undervalued Tool for Energy Efficiency Enhancement and Decarbonizing the Construction Sector: A Case Study of a Dormitory in Poland. Energy Build. 2025, 330, 115337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulidevi, N.U.; Aji, B.S.K.; Hikmawati, E.; Surendro, K. Modeling Integrated Sustainability Monitoring System for Carbon Footprint in Higher Education Buildings. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 135365–135376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.M.; Hebala, A.; Hamad, M.S. Carbon Footprint Assessment for Higher Educational Institutions: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Telecommunications Conference, ITC-Egypt 2024, Cairo, Egypt, 22–25 July 2024; pp. 374–379. [Google Scholar]

- Talpur, B.D.; Ullah, A.; Ahmed, S. Water Consumption Pattern and Conservation Measures in Academic Building: A Case Study of Jamshoro Pakistan. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangita Mishra, S.; Shuruthi, B.K.; Jeevan Rao, H. Design of Rooftop Rainwater Harvesting Structure in a University Campus. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2020, 8, 3591–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchan, S.S.; Shiva Prasad, H.C. Feasibility of Roof Top Rainwater Harvesting Potential - A Case Study of South Indian University. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Qu, X.; Yu, Y. Enhancing Capacity Building to Climate Adaptation and Water Conservation among Chinese Young People. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control 2021, 28, 27614–27628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleki, N.; Kulaksiz, S.B.; Arslan, F.; Guney Coskun, M. The Evaluation of Menus’ Adherence to Sustainable Nutrition and Comparison with Sustainable Menu Example in a Turkish University Refectory. Nutr. Food Sci. 2023, 53, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.F.; Eini-Zinab, H.; Anari, F.M.; Amirolad, M.; Babaei, Z.; Sobhani, S.R. Food Waste Reduction and Its Environmental Consequences: A Quasi-Experimental Study in a Campus Canteen. Agric. Food Secur. 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, F.; Kern, A.; Braganca, L. Comparative Analysis of Sustainable Development Environmental Indicators between Worldwide, Portugal and Brazil and between Two Universities within These Countries. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 503, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, R.M. Environmental Management and Monitoring for Education Building Development. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1013, 012105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, D.A.; Ghisi, E. Potential for Potable Water Savings Using Rainwater: A Case Study in a University Building in Southern Brazil. Urban Water J. 2024, 21, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Kumar, M.; Werner, D. Real-World Sustainability Analysis of an Innovative Decentralized Water System with Rainwater Harvesting and Wastewater Reclamation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakar, V.; Sihag, N.; Gieschen, R.; Andrew, S.; Herrmann, C.; Sangwan, K.S. Environmental Impact Analysis of a Water Supply System: Study of an Indian University Campus. Procedia CIRP 2015, 29, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Qdais, H.; Saadeh, O.; Al-Widyan, M.; Al-tal, R.; Abu-Dalo, M. Environmental Sustainability Features in Large University Campuses: Jordan University of Science and Technology (JUST) as a Model of Green University. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, L.; Munguia, N.; Ojeda, M. Optimizing Water Use in the University of Sonora, Mexico. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 46, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antão-Geraldes, A.M.; Ohara, G.; Afonso, M.J.; Albuquerque, A.; Silva, F. Towards Sustainable Water Use in Two University Student Residences: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghayedi, A.; Michell, K.; Hübner, D.; Le Jeune, K.; Massyn, M. Examine the Impact of Green Methods and Technologies on the Environmental Sustainability of Supportive Education Buildings, Perspectives of Circular Economy and Net-Zero Carbon Operation. Facilities 2024, 42, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.E.P.; Silva, J.K.D.; Nunes, L.G.C.F.; Rios Ribeiro, M.M.; Silva, S.R.D. Water Conservation Potential within Higher Education Institutions: Lessons from a Brazilian University. Urban Water J. 2023, 20, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parece, T.E.; Grossman, L.; Geller, E.S. Reducing Carbon Footprint of Water Consumption: A Case Study of Water Conservation at a University Campus. In Climate Change and Water Resources. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 25, pp. 199–218. ISBN 9783642375859. [Google Scholar]

- Lanchipa-Ale, T.; Bruz-Baltuano, A.; Molero-Yañez, N.; Chucuya, S.; Vera-Barrios, B.; Pino-Vargas, E. Assessment of Greywater Reuse in a University Building in a Hyper-Arid Region: Quantity, Quality, and Social Acceptance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmhan, Y.; Ravindra, P.; Chaturvedi, S.; Hegde, M.; Ballamajalu, R. Towards a Data-Driven IoT Software Architecture for Smart City Utilities. Softw.-Pract. Exp. 2018, 48, 1390–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, S.; Santoyo-Ramón, J.A.; Palacios, D.; Baena, E.; Mora-García, R.; Medina, M.; Mora, P.; Barco, R. The Campus as a Smart City: University of Málaga Environmental, Learning, and Research Approaches. Sensors 2019, 19, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, S.; Bustos, P.; Núñez, P. Towards a Cyber-Physical System for Sustainable and Smart Building: A Use Case for Optimising Water Consumption on a SmartCampus. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 6379–6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Choudhary, M.; Sørensen, K. Demonstration of Real-Time Monitoring in Smart Graded-Water Supply Grid: An Institutional Case Study. AQUA Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2023, 72, 2152–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz, N.A.A.; Musa, T.A.; Musliman, I.A.; Omar, A.H.; Wan Aris, W.A. Smart Water Network Monitoring: A Case Study at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci.-ISPRS Arch. 2022, 46, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, O.C.; Olaleye, T.O.; Arogundade, O.T.; Ifeanacho, F.; Adesemowo, A.K. Contextual Use of IoT Based Water Quality Control System. In Proceedings of the Co-Creating for Context in the Transfer and Diffusion of IT, Maynooth, Ireland, 15–16 June 2022; pp. 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, J.; Royapoor, M.; Acharya, K.; Jonczyk, J.; Werner, D. Performance Gaps of Sustainability Features in Green Award-Winning University Buildings. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, A.K.; Terala, A.; Goyal, A.; Chaudhari, S.; Rajan, K.S.; Chouhan, S.S. Behavioural Analysis of Water Consumption Using IoT-Based Smart Retrofit Meter. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 113597–113607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarpellon, B.O.; De Oro Arenas, L.; Paciencia Godoy, E.; Pinhabel Marafao, F.; Morales Paredes, H.K. Design and Implementation of a Smart Campus Flexible Internet of Things Architecture on a Brazilian University. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 113705–113725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Villacrés, D.V.; Gallegos Rios, D.F.; Chiliquinga López, Y.A.; Córdova Córdova, J.J.; Arroba Giraldo, A.M. The Implementation of IoT Sensors in Fog Collector Towers and Flowmeters for the Control of Water Collection and Distribution. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, E.; Shahrour, I. Use of Data-Driven Methods for Water Leak Detection and Consumption Analysis at Microscale and Macroscale. Water 2024, 16, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.P.; Murray, S.N.; O’Sullivan, D.T.J. The Water Energy Nexus, an ISO50001 Water Case Study and the Need for a Water Value System. Water Resour. Ind. 2015, 10, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Kumar, A.; Rathod, N.; Jain, P.; Mallikarjun, S.; Subramanian, R.; Amrutur, B.; Kumar, M.M.; Sundaresan, R. Towards and IoT Based Water Management System. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE First International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Guadalajara, Mexico, 25–28 October 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Lv, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, R. Water Demand Prediction Model of University Park Based on BP-LSTM Neural Network. Water 2025, 17, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, O.O.; Owolabi, T.A.; Fatoyinbo, I.O.; Ayodele, O.E.; Obasaju, D.O. Characterization of Factors Influencing Water Quality in Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta and Its Environ, Southwestern Nigeria. Int. J. Energy Water Resour. 2021, 5, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, X.; Mahmud, S.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Zhu, Y. Permeable Pavement Design Framework for Urban Stormwater Management Considering Multiple Criteria and Uncertainty. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Sun, Y.; Ren, X. Comprehensive Assessment of Water Sensitive Urban Design Practices Based on Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis via a Case Study of the University of Melbourne, Australia. Water 2020, 12, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, M.E.; Arnold, C.L.; Milardo, K.D.; Miller, R.A. The Care and Feeding of a Long-Term Institutional Commitment to Green Stormwater Infrastructure: A Case Study at the University of Connecticut. J. Green Build. 2015, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniquiz-Redillas, M.C.; Geronimo, F.K.F.; Kim, L.H. Investigation on the Effectiveness of Pretreatment in Stormwater Management Technologies. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 1824–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amur, A.; Wadzuk, B.; Traver, R. Analyzing the Performance of a Rain Garden over 15 Years: How Predictable Is the Rain Garden’s Response? In Proceedings of the International Low Impact Development Conference 2020, Bethesda, MD, USA, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Papuga, S.A.; Seifert, E.; Kopeck, S.; Hwang, K. Ecohydrology of Green Stormwater Infrastructure in Shrinking Cities: A Two-Year Case Study of a Retrofitted Bioswale in Detroit, MI. Water 2022, 14, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kazemi, H.; Rockaway, T.D. Performance Assessment of Stormwater GI Practices Using Artificial Neural Networks. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toran, L. Water Level Loggers as a Low-Cost Tool for Monitoring of Stormwater Control Measures. Water 2016, 8, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmayani, A.N. Urban Runoff and Pollutant Reduction by Retrofitting Green Infrastructures in Storm Water Management System. In Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2019, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 19–23 May 2019; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Niu, S.; Yu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, T. Microplastics and Microorganisms in Sediments from Stormwater Drain System. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 889, 164284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, V.C.; Kao, M.H.; Liu, J.C. Assessment of Rainwater Harvesting Systems at a University in Taipei. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 67, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dronjak, L.; Kanan, S.; Ali, T.; Mortula, M.M.; Mohammed, A.; Ramos, J.N.; Aga, D.S.; Samara, F. Stormwater in the Desert: Unveiling Metal Pollutants in Climate-Intensified Flooding in the United Arab Emirates. Water 2025, 17, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufault, R.; Batal, K.; Decoteau, D. Design, Construction, and Operation of a Demonstration Rainwater Harvesting System for Greenhouse Irrigation at McGill University, Canada. Horttechnology 2013, 23, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A.; Rathnayake, U. Stormwater Runoff Quality in Malabe, Sri Lanka. Eng. Appl. Sci. Res. 2018, 45, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jv, X.; Dzakpasu, M.; Wang, X.C. Evolution of Water Quality in Rainwater Harvesting Systems during Long-Term Storage in Non-Rainy Seasons. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gispert, M.Í.; Hernández, M.A.A.; Climent, E.L.; Flores, M.F.T. Rainwater Harvesting as a Drinking Water Option for Mexico City. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazizan, A.b.A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Hayder, G. Assessment of Stormwater Runoff Quality in Various Location in University Campus. Water Resour. Dev. Manag. 2020, 1, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehata, K.; Espindola, C.A.; Ashraf, A.; Adams, H. Augmentation of Reclaimed Water with Excess Urban Stormwater for Direct Potable Use. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbashi, N.A.; Jami, M.S.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Puad, N.I.M. Rainwater Harvesting Quality Assessment and Evaluation: IIUM Case Study. IIUM Eng. J. 2020, 21, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, S.; Hadler, G.; Opitz, L.; Thoms, A. Using Stormwater in a Sponge City as a NewWing of Urban Water Supply—A Case Study. Water 2023, 15, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Tong, L.; Li, K.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L. Volatile Organic Compounds in Stormwater from a Community of Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Z. Transport Process and Source Contribution of Nitrogen in Stormwater Runoff from Urban Catchments. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marko, I.; Škultétyová, I.; Hrudka, J.; Rózsa, G. Studying the effect of urban runoff from the roadway and analysis of the chemical composition of stormwater. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConference Surv. Geol. Min. Ecol. Manag. SGEM 2020, 20, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, A.; Puszczało, E.; Szymańska, K.; Sroka, M.; Kudlek, E.; Generowicz, A. Application of Mesoporous Silicas for Adsorption of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants from Rainwater. Materials 2024, 17, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maykot, J.K.; Martins Vaz, I.C.; Ghisi, E. Characterisation of First Flush for Rainwater Harvesting Purposes in Buildings. Water 2025, 17, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElmurry, S.P.; Long, D.T.; Voice, T.C. Stormwater Dissolved Organic Matter: Influence of Land Cover and Environmental Factors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddeo, V.; Scannapieco, D.; Belgiorno, V. Enhanced Drinking Water Supply through Harvested Rainwater Treatment. J. Hydrol. 2013, 498, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, N.; Bhandari, S.; Mafuzur Rahaman, M.; Wagner, K.; Kalra, A.; Ahmad, S.; Gupta, R. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Bioswales and Catch Basin Inserts for Treating Urban Stormwater Runoff in Detroit, Michigan. In Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2019, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 19–23 May 2019; pp. 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Osawa, T.M.; Pereira, M.C.S.; Leite, B.C.C.; Martins, J.R.S. Impact of an Aged Green Roof on Stormwater Quality and First-Flush Dynamics. Buildings 2025, 15, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, A.; Chandra, I.; Setyawati, W.; Tanti, D.A.; Indrawati, A.; Alawi, A.F.; Karo, B.F.B.; Sabilla, V.A.; Prihatini, A.P.A. Central Tendency Data Real-Time Acid Rain Measurement to Evaluate Tool’s Performance Using Statistical Analysis. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 14, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T.T.; Alim, M.A.; Rahman, A. Simple and Effective Filtration System for Drinking Water Production from Harvested Rainwater in Rural Areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiquzzaman, M.; Haider, H.; Ghazaw, Y.M.; Alharbi, F.; Alsaleem, S.S.; Almoshaogeh, M. Evaluation of a Low-Cost Ceramic Filter for Sustainable Reuse of Urban Stormwater in Arid Environments. Water 2020, 12, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiquzzaman, M.; Uddin, B. Evaluating Preamble Clay Bricks for Mitigating Urban Heat Island Effects and Stormwater Pollution. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza de Carvalho, J.; Bello-Mendoza, R.; O’Sullivan, A. Field Performance of an Innovative Downpipe Roof Runoff Treatment System: Effect of Roof Material, Stormwater Characteristics, and System Age on Heavy Metals Removal. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, G.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Basapuram, G.; Dutta, A.; Duttagupta, S. Molecular and Ionic Signatures in Rainwater: Unveiling Sources of Atmospheric Pollution. Environments 2025, 12, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Lyu, F.; Liu, F.; Liu, L.; Su, Y.; Yuan, S.; Xiao, W.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Hydrological Reduction and Control Effect Evaluation of Sponge City Construction Based on One-Way Coupling Model of SWMM-FVCOM: A Case in University Campus. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, Q.; Ai, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Pollutant Concentrations and Pollution Loads in Stormwater Runoff from Different Land Uses in Chongqing. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Yu, H. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Heavy Metals Concentration in Urban Stormwater Runoff. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 726–731, 1801–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewantha, H.L.S.S.; Dharaka, B.D.P.; Deeyamulla, M.P.; Priyantha, N. Monitoring of Rainwater Quality in Kandy and Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Loc, H.H.; Babel, M.S.; Stamm, J. A Community-Scale Study on Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for Stormwater Management under Tropical Climate: The Case of the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), Thailand. J. Hydroinformatics 2024, 26, 1080–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, C.; Jia, B.; Cheng, B. Cumulative Risk of Heavy Metals in Long-Term Operational Rain Garden. Water 2025, 17, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulistyorini, A.; Idfi, G.; Fahmi, E.D. Enhanced Rooftop Rainwater Harvesting Quality through Filtration Using Zeolite and Activated Carbon. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 204, 03016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, G.; Bortolini, L.; Borin, M. Assessing Stormwater Nutrient and Heavy Metal Plant Uptake in an Experimental Bioretention Pond. Land 2018, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Hong, N.; Yang, B.; Du, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, A. Toxicity Variability of Urban Road Stormwater during Storage Processes in Shenzhen, China: Identification of Primary Toxicity Contributors and Implications for Reuse Safety. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraini, N.A.; Alias, N.; Abd Rahman, N.; Harun, S.; Ibrahim, Z.; Azman, S.; Jumain, M. Influence of Rainfall Characteritics on Total Suspended Solid Concentration. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1049, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ho, Y.W.; Fang, J.K.H.; Li, Y. Characterization and Ecological Risks of Microplastics in Urban Road Runoff. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpanke, J.; Henry, I.I.; Ugbadu, J.I.; Abuh, S.A. In Vitro Antibiotics Resistance Patterns of Selected Genera of Bacteria from Waste Collection Sites in University of Calabar Campus, Cross River State, Nigeria. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2023, 19, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amoush, H.; Al-Ayyash, S.; Shdeifat, A. Harvested Rain Water Quality of Different Roofing Material Types in Water Harvesting System at Al Al-Bayt University/Jordan. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 12, 228–244. [Google Scholar]

- Allameh, Z.; Kouchakzadeh, M.; Imteaz, M.A. Investigation of Stormwater Quality from Successive First Flush Diverted from Roof for Different Roofing Materials. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 8149–8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang Ali, A.N.; Bolong, N. Determination of Water Quality in Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS), Kota Kinabalu: The Effectiveness of Stormwater Management Systems. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio-Vallejo, E.; Düker, U.; Nogueira, R. Rainwater Management and Associated Health Risks: Case Study on the Welfengarten Campus of the Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1590548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, S.; Dzakpasu, M.; Wang, X.C. Optimizing Roof-Harvested Rainwater Storage: Impact of Dissolved Oxygen Regime on Self-Purification and Quality Dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniquiz-Redillas, M.C.; Kim, L.H. Understanding the Factors Influencing the Removal of Heavy Metals in Urban Stormwater Runoff. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 2921–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberascher, M.; Kinzel, C.; Kastlunger, U.; Schöpf, M.; Grimm, K.; Plaiasu, D.; Rauch, W.; Sitzenfrei, R. Smart Water Campus—A Testbed for Smart Water Applications. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 2834–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Fang, W.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Mu, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, P.; Zainol, M.R.R.M.A.; Zawawi, M.H.; Chong, K.L.; et al. Optimizing the Deployment of LID Facilities on a Campus-Scale and Assessing the Benefits of Comprehensive Control in Sponge City. J. Hydrol. 2024, 635, 131189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badriyyah, M.N.; Adistya, N.; Sagita, S.D.; Saputri, U.S.; Sari, N.K.; Marifah, S.L. Analysis of Rainwater Harvesting for Toilet and Landscaping Needs of Building B, Nusa Putra University. BIO Web Conf. 2025, 148, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogano, M.M.; Okedi, J. Toward a Water-Sensitive Precinct with Stormwater Harvesting: A Case Study in South Africa. Water Supply 2024, 27, 2367–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, Y.; Ne’eman, N.; Gimburg, A.; Benenson, I. Integrative Runoff Infiltration Modeling of Mountainous Urban Karstic Terrain. Hydrology 2025, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Wang, S.; Ha, M.; Kang, A.; Lei, X.; Chen, B.; Yu, Y.; Chai, B. Comparative Hydrologic Performance of Cascading and Distributed Green-Gray Infrastructure: Experimental Evidence for Spatial Optimization in Urban Waterlogging Mitigation. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 133979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Xue, C.; Qiu, R.; Sun, S.; Yang, Z.; Qiao, Y. Assessing the Effectiveness of a Residential-Scale Detention Tank Operated in a Multi-Objective Approach Using SWMM. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 89, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGauley, M.W.; Zaremba, G.; Wadzuk, B.M. A Complete Water Balance of a Constructed Stormwater Wetland. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR039045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebicho, S.W.; Lou, B.; Anito, B.S. A Multi-Parameter Flexible Smart Water Gauge for the Accurate Monitoring of Urban Water Levels and Flow Rates. Eng 2024, 5, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakimov, B.N.; Zaznobina, N.I.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Bolshakova, A.D.; Kovaleva, T.A.; Markelov, I.N.; Onishchenko, V.V. University Campuses as Vital Urban Green Infrastructure: Quantifying Ecosystem Services Based on Field Inventory in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia. Land 2025, 14, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.B.; Fahmy, M.I.; Abed, A.M.; Kazem, H.A.; Chaichan, M.T.; Rahmat, M.A.A. Malaysian Rainwater Harvesting System for In-House Power Generation. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2024, 922, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.K.; Dolui, S.; Dutta, K.; Baruah, B.; Ranjan, R.K.; Wanjari, N. Sustainable Water Management in Sikkim Himalayan Region: Innovative Solutions for Rainwater Harvesting Reservoirs. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2024, 9, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mazijk, R.; Smyth, L.K.; Weideman, E.A.; West, A.G. Isotopic Tracing of Stormwater in the Urban Liesbeek River. Water SA 2018, 44, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, A.L.; Mandarano, L.; Greising, K.; Mastrocola, K. Application of a Monitoring Plan for Storm-Water Control Measures in the Philadelphia Region. J. Environ. Eng. 2013, 139, 1108–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnecco, I.; Palla, A.; Lanza, L.G.; La Barbera, P. The Role of Green Roofs as a Source/Sink of Pollutants in Storm Water Outflows. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 4715–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Macedo, M.B.; do Lago, C.A.F.; Mendiondo, E.M. Stormwater Volume Reduction and Water Quality Improvement by Bioretention: Potentials and Challenges for Water Security in a Subtropical Catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, L.; Zanin, G. The Experimental and Educational Rain Gardens of the Agripolis Campus (North-East Italy): Preliminary Results on Hydrological and Plant Behavior. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1189, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagchaudhuri, A.; Mitra, M.; Ford, T.; Pandya, J.R. Towards Efficient Irrigation Management with Solar-Powered Wireless Soil Moisture Sensors and Real-Time Monitoring Capability. In Proceedings of the 2021 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, Virtual, 26 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowska, E.; Gajewska, M.; Nawrot, N.; Kilanowska, M.; Obarska-Pempkowiak, H. Combination of architectural, environmental and social aspects in urban stormwater management. A case study of the university campus. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 12, 681–700. [Google Scholar]

- Amur, A.; Wadzuk, B.; Traver, R. Exploring Storm Intensities and the Implications on Green Stormwater Infrastructure Design. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e15333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchán-Sanmartín, B.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Suárez-Zamora, S.; Aguilar-Aguilar, M.; Cruz-Cabrera, O.; Hidalgo-Calva, K.; Morante-Carballo, F. Stormwater Sewerage Masterplan for Flood Control Applied to a University Campus. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1279–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochodyła-Ducka, E.; Glinska-Lewczuk, K.G.; Jaszczak, A. Changes in Stormwater Quality and Heavy Metals Content along the Rainfall–Runoff Process in an Urban Catchment. Water 2023, 15, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisano, A.; Butler, D.; Ward, S.; Burns, M.J.; Friedler, E.; DeBusk, K.; Fisher-Jeffes, L.N.; Ghisi, E.; Rahman, A.; Furumai, H.; et al. Urban Rainwater Harvesting Systems: Research, Implementation and Future Perspectives. Water Res. 2017, 115, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, I.; Goodarzi, M. Rainwater Harvesting System: A Sustainable Method for Landscape Development in Semiarid Regions, the Case of Malayer University Campus in Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 1579–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosonen, H.; Kim, A. Rainwater System to Concrete Laboratory—An Interdisciplinary Approach to Sustainability Education. In Proceedings of the 6th CSCE-CRC International Construction Specialty Conference 2017 - Held as Part of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering Annual Conference and General Meeting 2017, Vancouver, WA, Canada, 31 May–3 June 2017; pp. 1226–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Paschoalin, R.; Pace, R.; Isaacs, N. Urban Resilience: Potential for Rainwater Harvesting in a Heritage Building. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Architectural Science Association, Auckland, New Zealand, 26–27 November 2020; pp. 1331–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.P.; Liberalesso, T.; Silva, C.M.; Sousa, V. Dynamic Modelling of Rainwater Harvesting with Green Roofs in University Buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, A.; Zeleňáková, M. An Analysis of the Effectiveness of Two Rainwater Harvesting Systems Located in Central Eastern Europe. Water 2019, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Page, D.; Zhou, Y.; Vanderzalm, J.; Dillon, P. Roof Runoff Replenishment of Groundwater in Jinan, China. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2015, 20, B5014005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyani, D.; Wulandari, A.; Juniati, A.; Nur Arini, R. Rainwater Harvesting for Water Security in Campus (Case Study Engineering Faculty in University of Pancasila). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1858, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukkaya, E.; Kelesoglu, A.; Gunaydin, H.; Kilic, G.A.; Unver, U. Design of a Passive Rainwater Harvesting System with Green Building Approach. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2020, 40, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.; Liberalesso, T.; Silva, C.M.; Sousa, V. Combining Green Roofs and Rainwater Harvesting Systems in University Buildings under Different Climate Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 887, 163719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.G.; Wang, B. Recycled Water Reuse and Rainwater Utilization Project of Jilin Jianzhu University. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 448–453, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, T.; Han, M.; Park, H.; Kim, T.-I. Design and Technical Evaluation of Improved Rainwater Harvesting System on a University Building in Ethiopia. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2015, 15, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaimoon, N. The Observation of Rainwater Harvesting Potential in Mahasarakham University (Khamriang Campus). Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 807–809, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana, G.V.; Sudheer, C.S.S.; Suresh Kumar, R. An Identification of Suitable Location to Construct Underground Sump for Rooftop Rainwater Harvesting in the Campus of Debre Tabor University. In Advanced Modelling and Innovations in Water Resources Engineering; Rao, C.M., Patra, K.C., Jhajharia, D., Kumari, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Sun, S.; Ji, X. The Inspiration of Rainwater Utilization of Foreign Sponge Campus Landscape Planning for Beijing. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 227, 052019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Sanchez, M.A.; Del Aguila, M.; Kim, S. Green Building Strategies for LEED Certified Recreational Facilities. J. Green Build. 2017, 12, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Wen, G.; Liu, A. Urban Stormwater Disinfection, Quality Variability during Storage and Influence on the Freshwater Algae: Implications for Reuse Safety. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, P.; Medhi, H.; Sagar, A.; Garg, P.; Singh, A.; Karna, U. Runoff Estimation Using Digital Image Processing for Residential Areas. AQUA Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2022, 71, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wu, Z.; Kong, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Gao, W. Enhancing Water Reliability and Overflow Control Through Coordinated Operation of Rainwater Harvesting Systems: A Campus–Residential Case in Kitakyushu, Japan. Buildings 2025, 15, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Moustakas, S.; Bezak, N.; Radinja, M.; Alivio, M.B.; Mikoš, M.; Dohnal, M.; Bares, V.; Willems, P. Assessing the Performance of Blue-Green Solutions through a Fine-Scale Water Balance Model for an Urban Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacki, A.; Pathirana, S. Effect of Green Building Features on Energy Efficiency of University Buildings in Tropical Climate. Sustain. Future 2025, 10, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintura, I.; Arenas, A. Multi-Scale Assessment of Rainwater Harvesting Availability across the Continental U.S. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupido, A.; Steinberg, L.; Baetz, B. Water Conservation: Observations from a Higher Education Facility Management Perspective. J. Green Build. 2016, 11, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Willems, P. Assessing Blue-Green Infrastructures for Urban Flood and Drought Mitigation under Changing Climate Scenarios. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 62, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.; Schmidt, S. Designing Wetlands as an Essential Infrastructural Element for Urban Development in the Era of Climate Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mehedi, M.A.; Amur, A.; Metcalf, J.; McGauley, M.; Smith, V.; Wadzuk, B. Predicting the Performance of Green Stormwater Infrastructure Using Multivariate Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Network. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 130076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ament, M.R.; Roy, E.D.; Yuan, Y.; Hurley, S.E. Phosphorus Removal, Metals Dynamics, and Hydraulics in Stormwater Bioretention Systems Amended with Drinking Water Treatment Residuals. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2022, 8, 04022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Itzhaki, Z.; Tifferet, S.; Berkowic, D.; Arviv, T.; Daya, A.; Carasso Romano, G.H.; Levi, A. Strategies and Challenges for Green Campuses. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1469274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumgarner, N.R.; Ludwig, A.L.; Collett, B.P.; Stewart, C.E. Establishing Campus Rain Gardens That Link Student Experiential Learning with Stakeholder Education and Outreach. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1189, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.C.; Thomas, S.; Rotz, R.R.; Missimer, T.M. Stormwater Pond Evolution and Challenges in Measuring the Hydraulic Conductivity of Pond Sediments. Water 2023, 15, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Bensi, M.; Davis, A.P.; Kjellerup, B.V. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in Dissolved and Particulate Phases of Urban Stormwater before and after Bioretention Treatment. ACS ES T Water 2023, 3, 3235–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasena, G.I.; Deletic, A.; McCarthy, D.T. Survival of Escherichia coli in Stormwater Biofilters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 5391–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasena, G.I.; Deletic, A.; McCarthy, D.T. Biofiltration for Stormwater Harvesting: Comparison of Campylobacter Spp. and Escherichia Coli Removal under Normal and Challenging Operational Conditions. J. Hydrol. 2016, 537, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, K.; Kjellerup, B.V.; Davis, A.P. Interactions of Particulate- and Dissolved-Phase Heavy Metals in a Mature Stormwater Bioretention Cell. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Accumulation Characteristics and Risk of Heavy Metals and Microbial Community Composition in Bioretention Systems: A Case Study of a University Campus. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 193, 106996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K.M.; Traver, R.G. Green Infrastructure Life Cycle Assessment: A Bio-Infiltration Case Study. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 55, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galella, J.G.; Kaushal, S.S.; Mayer, P.M.; Maas, C.M.; Shatkay, R.R.; Stutzke, R.A. Stormwater Best Management Practices: Experimental Evaluation of Chemical Cocktails Mobilized by Freshwater Salinization Syndrome. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1020914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimo, F.K.F.; Maniquiz-Redillas, M.C.; Kim, L.-H. Treatment of Suspended Solids and Heavy Metals from Urban Stormwater Runoff by a Tree Box Filter. Desalin. Water Treat. 2013, 51, 4044–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.P.P.; Cohan, A.; Chan, H.S.; Livesley, S.J.; Beringer, J.; Daly, E. Occasional Large Emissions of Nitrous Oxide and Methane Observed in Stormwater Biofiltration Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 465, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Influences of Stormwater Concentration Infiltration on the Heavy Metal Contents of Soil in Rain Gardens. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 81, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.T.; Geronimo, F.K.F.; Robles, M.E.L.; Vispo, C.; Kim, L.H. Comparative Evaluation of the Carbon Storage Capacities in Urban Stormwater Nature-Based Technologies. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 212, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.J.; Roseen, R.M.; Ballestero, T.P.; Puls, T.A.; Sherrard, J. Comparison of Maintenance Cost, Labor Demands, and System Performance for LID and Conventional Stormwater Management. J. Environ. Eng. 2013, 139, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.C.; Rugh, M.; Feraud, M.; Avasarala, S.; Kurylo, J.; Gutierrez, M.; Jimenez, K.; Truong, N.; Holden, P.A.; Grant, S.B.; et al. Influence of Soil Characteristics and Metal(Loid)s on Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Green Stormwater Infrastructure in Southern California. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imteaz, M.A.; Ahsan, A.; Rahman, A.; Mekanik, F. Modelling Stormwater Treatment Systems Using MUSIC: Accuracy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 71, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, M.; Trach, Y.; Trach, R.; Tkachenko, T.; Mileikovskyi, V. Improving the Efficiency and Environmental Friendliness of Urban Stormwater Management by Enhancing the Water Filtration Model in Rain Gardens. Water 2024, 16, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniquiz-Redillas, M.; Kim, L.H. Fractionation of Heavy Metals in Runoff and Discharge of a Stormwater Management System and Its Implications for Treatment. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranan, C.; Cruz, G.; Santos, F. Quantifying Blue, Green, and Gray Water Footprints in a Mixed Land Use Urban Catchment for Sustainable Urban Water Management. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1655691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhillips, L.; Goodale, C.; Walter, M.T. Nutrient Leaching and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Grassed Detention and Bioretention Stormwater Basins. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navickis-Brasch, A.S.; Bormann, N.E.; Niezgoda, S.L.; Zarecor, M. Expanding the Presence of Stormwater Management in Undergraduate Civil Engineering. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 15–18 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamutdinova, Z.F.; Potonova, N.A. Determination of Territorial Compactness and Analysis of Optimization of Energy-Efficient Characteristics of the University Campus. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 751, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, N.; Bhandari, S.; Mafuzur Rahaman, M.; Wagner, K.; Kalra, A.; Ahmad, S.; Gupta, R. Improvements to SIU’s Engineering Campus Parking and Walkways along Campus Lake Melissa. In Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2016, West Palm Beach, FL, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Cui, H.; Ji, M. Sustainable Rainwater Utilization and Water Circulation Model for Green Campus Design at Tianjin University. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2018, 4, 04017015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinasseau, L.; Wiest, L.; Volatier, L.; Mermillod-Blondin, F.; Vulliet, E. Emerging Polar Pollutants in Groundwater: Potential Impact of Urban Stormwater Infiltration Practices. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poor, C.; Membrere, T.; Miyasato, J. Impact of Green Stormwater Infrastructure Age and Type on Water Quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Dai, Y. Reshaping Resilient Cities from an Educational Perspective: The Case of IZJU. In Sustainable and Smart Cities: Governance, Economy and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 131–142. ISBN 9781040335857. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, C.J.; Flanagan, N.E. Water Quality and Wetland Vegetation Responses to Water Level Variations in a University Stormwater Reuse Reservoir: Nature-Based Approaches to Campus Water Sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippy, M.A.; Pierce, G.; Feldman, D.; Winfrey, B.; Mehring, A.S.; Holden, P.A.; Ambrose, R.; Levin, L.A. Perceived Services and Disservices of Natural Treatment Systems for Urban Stormwater: Insight from the next Generation of Designers. People Nat. 2022, 4, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample-Lord, K.M.; Smith, V.; Gallagher, P.; Welker, A.L. Using Your Campus as a Laboratory: An Adaptable Field Trip on Geomorphology for Engineering Geology. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, Tampa, FL, USA, 15–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharuddin, S.; Zakaria, N.A.; Ghani, A.; Wan Maznah, W.O. Assessing Phytoplankton Distribution and Water Quality in Constructed Wetlands during Dry and Wet Periods: A Case Study in USM Engineering Campus. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 380, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Yusof, M.J.M.; Zhao, J.; Liu, R. Exploring Herbaceous Plant Biodiversity Design in Chinese Rain Gardens: A Literature Review. Water 2024, 16, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.B.; McGauley, M.W.; Newman, M.; Garzio-Hadzick, A.; Kurzweil, A.; Wadzuk, B.M.; Traver, R. A Relational Data Model for Advancing Stormwater Infrastructure Management. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2023, 9, 04022023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strybos, J.W.; Lanford, M.L. Water Conservation, Management and Re-Use at Northwest Vista College John. In Proceedings of the Water Conservation, Management, and Re-Use at Northwest Vista College, San Antonio, TX, USA, 21 May 2015; pp. 2707–2715. [Google Scholar]

- Veracka, M. Delivering Better Water Quality: Rethinking Storm Water Management. In Proceedings of the 2013 Energy and Sustainability Conference, Farmingdale, NY, USA, 22 March 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Dick, W.A.; McCoy, E.L.; Phelan, P.L.; Grewal, P.S. Field Evaluation of a New Biphasic Rain Garden for Stormwater Flow Management and Pollutant Removal. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 54, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Davis, A.P.; Kaya, D.; Kjellerup, B.V. Distribution and Biodegradation Potential of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Accumulated in Media of a Stormwater Bioretention. Chemosphere 2023, 336, 139188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarezadeh, V.; Lung, T.; Dorman, T.; Shipley, H.J.; Giacomoni, M. Assessing the Performance of Sand Filter Basins in Treating Urban Stormwater Runoff. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, L. A Type of Rainwater Ecological Treatment Technology: Rainwater Biofiltration System. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 295–298, 1502–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, P. Numerical Simulation Study of Urban Hydrological Effects under Low Impact Development with a Physical Experimental Basis. J. Hydrol. 2023, 618, 129191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Cho, E.; Lee, M.; Kim, S. Observation Experiment of Wind-Driven Rain Harvesting from a Building Wall. Water 2022, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Yan, P.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Lyu, J.; He, B.; Duan, W.; Wang, S.; Zha, X. Historical and Comparative Overview of Sponge Campus Construction and Future Challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, B.; Alodah, A. Multivariate Analysis of Harvested Rainwater Quality Utilizing Sustainable Solar-Energy-Driven Water Treatment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.F.; Linn, C.; Hunt, D.; Dabney, B.; Hartrick, J.; Ekhator, K.; Lyon, N.; Miller, C.J.; Mitra, R.; Serreyn, M.; et al. Designing Community Facing Tools for Green Stormwater Infrastructure and Groundwater Monitoring: A Model of Interdisciplinary Action Research. Environ. Res. Commun. 2025, 7, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Zamora, S.; Velásquez-Molina, A.; Rosales-Serrano, P.; Arias-Hidalgo, M.; Jaya-Montalvo, M.; Aguilar-Aguilar, M. Water Availability in a University Campus: The Role of an Artificial Lake as a Nature-Based Solution. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1631938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, P.; Mazzeo, D.; Bruno, R.; Arcuri, N. Surface Temperature Analysis of an Extensive Green Roof for the Mitigation of Urban Heat Island in Southern Mediterranean Climate. Energy Build. 2017, 150, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, P.; Mazzeo, D.; Bruno, R.; Arcuri, N. Experimental Investigation of the Thermal Performances of an Extensive Green Roof in the Mediterranean Area. Energy Build. 2016, 122, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, A.; Conte, A.; Maglionico, M.; Stojkov, I. Green Roofs for Sustainable Water Management in Urban Areas. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, G.; Šimůnek, J.; Piro, P. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Variably Saturated Hydraulic Behavior of a Green Roof in a Mediterranean Climate. Vadose Zone J. 2016, 15, vzj2016-04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, T.B.; Marasco, D.E.; Culligan, P.J.; McGillis, W.R. Hydrological Performance of Extensive Green Roofs in New York City: Observations and Multi-Year Modeling of Three Full-Scale Systems. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 024036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, S.S.; Maglionico, M.; Stojkov, I. A Long-Term Hydrological Modelling of an Extensive Green Roof by Means of SWMM. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 95, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pecoraino, M.; Pagliaro, M. Solar Green Roofs: A Unified Outlook 20 Years On. Energy Technol. 2019, 7, 1900128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, E.; Urru, S.; Farris, S.; Ruggiu, D.; Deidda, R.; Viola, F. Analysis of Potential Benefits on Flood Mitigation of a CAM Green Roof in Mediterranean Urban Areas. Build. Environ. 2020, 183, 107179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkwa, J.; Suba, G.; Kokogiannakis, G. An Investigation into the Thermophysical Properties and Energy Dynamics of an Intensive Green Roof. JP J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 7, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Darkwa, J.; Kokogiannakis, G.; Suba, G. Effectiveness of an Intensive Green Roof in a Sub-Tropical Region. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2013, 34, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksi, M.; Rowe, D.B.; Wichman, I.S.; Andresen, J.A. Effect of Substrate Depth, Vegetation Type, and Season on Green Roof Thermal Properties. Energy Build. 2017, 145, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassman-Beck, E.; Voyde, E.; Simcock, R.; Hong, Y.S. 4 Living Roofs in 3 Locations: Does Configuration Affect Runoff Mitigation? J. Hydrol. 2013, 490, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Hewage, K. Energy Saving Performance of Green Vegetation on LEED Certified Buildings. Energy Build. 2014, 75, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, P.; La Gennusa, M.; Peri, G.; Rizzo, G.; Scaccianoce, G. Vegetation Growth Parameters and Leaf Temperature: Experimental Results from a Six Plots Green Roofs’ System. Energy 2016, 115, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, G.; Porti, M.; Carbone, M.; Nigro, G.; Piro, P. Effects of Evapotranspiration in the Energy Performance of a Vegetated Roof: First Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the 15th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference: SGEM 2015, Albena, Bulgaria, 18–24 June 2015; SGEM: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Fang, X.; Yin, D.; Xie, P.; Nie, L. Factors Affecting the Ability of Extensive Green Roofs to Reduce Nutrient Pollutants in Rainfall Runoff. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimdavar, R.; Culligan, P.J.; Finazzi, M.; Barontini, S.; Ranzi, R. Scale Dynamics of Extensive Green Roofs: Quantifying the Effect of Drainage Area and Rainfall Characteristics on Observed and Modeled Green Roof Hydrologic Performance. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 73, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Babcock, R.W. Green Roofs against Pollution and Climate Change. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, J.; Tran, S.; Gebert, L. Plant Functional Traits Predict Green Roof Ecosystem Services. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, H.V.; Carvalho, P.; Gajewska, M.; Ursino, N.; Masi, F.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Kazak, J.K.; Exposito, A.; Cipolletta, G.; Andersen, T.R.; et al. A Review of Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Water Management in European Circular Cities: A Critical Assessment Based on Case Studies and Literature. Blue-Green Syst. 2020, 2, 112–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, T.M.; Leite, B.C.C.; Martins, J.R.S. Improving Stormwater Retention in Humid Subtropical Cities: Environmental Controls on Green Roof Performance. Blue-Green Syst. 2025, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouldboukhitine, S.E.; Belarbi, R.; Sailor, D.J. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Urban Street Canyons to Evaluate the Impact of Green Roof inside and Outside Buildings. Appl. Energy 2014, 114, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianella, A.; Aye, L.; Chen, Z.; Williams, N.S.G. Effects of Substrate Depth and Native Plants on Green Roof Thermal Performance in South-East Australia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 588, 022057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, P.; Carbone, M.; De Simone, M.; Maiolo, M.; Bevilacqua, P.; Arcuri, N. Energy and Hydraulic Performance of a Vegetated Roof in Sub-Mediterranean Climate. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirouz, B.; Palermo, S.A.; Maiolo, M.; Arcuri, N.; Piro, P. Decreasing Water Footprint of Electricity and Heat by Extensive Green Roofs: Case of Southern Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzuti, G.; Lamonaca, F.; Arcuri, N. Data Acquisition for Green Roof. In Proceedings of the 19th IMEKO TC4 Symposium - Measurements of Electrical Quantities 2013 and 17th International Workshop on ADC and DAC Modelling and Testing, Barcelona, Spain, 18–19 July 2013; pp. 661–665. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi, A.; Marchioni, M.; Sanfilippo, U.; Becciu, G. Vegetation Survival in Green Roofs without Irrigation. Water 2021, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, T.; Dal Borgo, A.; Love, V.L.; Andri, S.; Tretiach, M.; Nardini, A. Drought versus Heat: What’s the Major Constraint on Mediterranean Green Roof Plants? Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566–567, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, A.W.; Robinson, C.E.; Smart, C.C.; Voogt, J.A.; Hay, G.J.; Lundholm, J.T.; Powers, B.; O’Carroll, D.M. Retention Performance of Green Roofs in Three Different Climate Regions. J. Hydrol. 2016, 542, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skala, V.; Dohnal, M.; Votrubova, J.; Vogel, T.; Dusek, J.; Sacha, J.; Jelinkova, V. Hydrological and Thermal Regime of a Thin Green Roof System Evaluated by Physically-Based Model. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speak, A.F.; Rothwell, J.J.; Lindley, S.J.; Smith, C.L. Metal and Nutrient Dynamics on an Aged Intensive Green Roof. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speak, A.F.; Rothwell, J.J.; Lindley, S.J.; Smith, C.L. Rainwater Runoff Retention on an Aged Intensive Green Roof. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 461–462, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speak, A.F.; Rothwell, J.J.; Lindley, S.J.; Smith, C.L. Reduction of the Urban Cooling Effects of an Intensive Green Roof Due to Vegetation Damage. Urban Clim. 2013, 3, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Bou-Zeid, E.; Wang, Z.H.; Zerba, E.; Ni, G.H. Hydrometeorological Determinants of Green Roof Performance via a Vertically-Resolved Model for Heat and Water Transport. Build. Environ. 2013, 60, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, D.; Driscoll, C.T.; Todorova, S.; Montesdeoca, M. Water Quality Function of an Extensive Vegetated Roof. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, S.A.; Midden, K.S. Sustainability of Urban Agriculture: Vegetable Production on Green Roofs. Agriculture 2018, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.S.G.; Rayner, J.P.; Lee, K.E.; Fletcher, T.D.; Chen, D.; Szota, C.; Farrell, C. Developing Australian Green Roofs: Overview of a 5-Year Research Program. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1108, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Hao, X.; Lin, Y.; Tan, H.; Yang, K. Experimental Investigation on the Thermal Performance of a Vertical Greening System with Green Roof in Wet and Cold Climates during Winter. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.Y.; Li, D.; Sun, T.; Ni, G.H. Saturation-Excess and Infiltration-Excess Runoff on Green Roofs. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 74, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, P.; Bruno, R.; Arcuri, N. Green Roofs in a Mediterranean Climate: Energy Performances Based on in-Situ Experimental Data. Renew. Energy 2020, 152, 1414–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Alim, M.A.; Rahman, A.; Haque, M.M. A Review on Chlorination of Harvested Rainwater. Water 2023, 15, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Alim, M.A.; Rahman, A. Disinfection Methods for Domestic Rainwater Harvesting Systems: A Scoping Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 46, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilca, A.F.; Teodosiu, C.; Fiore, S.; Musteret, C.P. Emerging Disinfection Byproducts: A Review on Their Occurrence and Control in Drinking Water Treatment Processes. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnisa, S.A.; Deepthi, P. Water Purification: A Sustainable Technology for Rural Development. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2010, 13, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]