Abstract

In deep underground engineering projects, the rock mass is frequently subjected to extreme environments characterized by high geostress and high permeation pressure. This makes the rock mass highly prone to disasters such as collapses, significant deformations, and water seepage. Among these factors, the direction of seepage plays a critical role. In this study, true triaxial tests were performed to investigate the characteristic stress and failure behaviors of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions. The test results indicate that, under permeation pressure (σp), the characteristic stresses are significantly reduced. After TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, the permeability of the mudstone decreases significantly. A volumetric dilation hysteresis effect of mudstone was discovered. Furthermore, the increase in β1 and decrease in β2 indicate that, after the transition from TTS-1 to TTS-2, the stable crack propagation stage in the mudstone is prolonged, while the unstable crack propagation stage is shortened. In the σ1–σ3 plane, after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, the change in the included angle between the mudstone fracture surface and the σ1 direction shows a reverse trend with the increase in σp.

1. Introduction

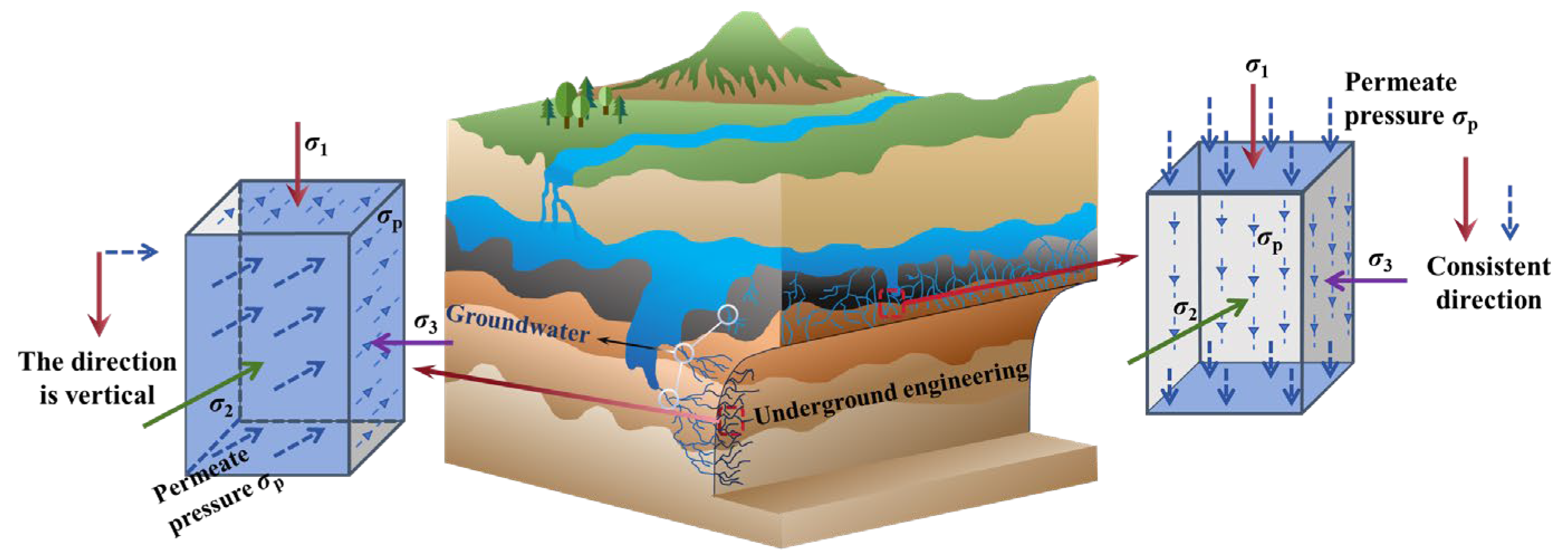

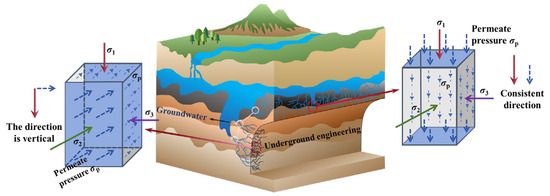

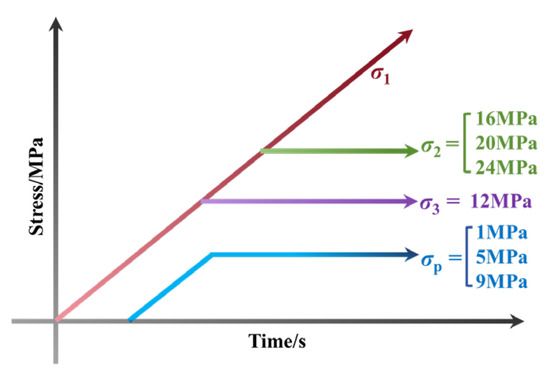

Deep resource exploitation and deep underground space utilization have become the norm, and deep engineering development will be an important field for humans in the future. However, the typical high-geostress and high-water pressure environment of deep rock masses may induce engineering disasters [1,2,3,4], and the combined effect of in situ stress and seepage pressure is very likely to cause the evolution of the original fractures within the rock [5,6,7]. Among them, different seepage directions can lead to significant differences in rock mechanical behavior, which greatly increases the complexity of underground engineering stability analysis [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The internal factors influencing rock deformation and failure are the propagation and connection of cracks. Characteristic stress, as an important basis for the division of crack evolution stages, is of great significance for research [14,15]. In addition, the intermediate principal stress has a crucial influence on the above process and is a factor that cannot be ignored [16,17]. Therefore, studying the evolution of characteristic stresses in rock under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions is of great importance for ensuring the stability of deep engineering under such complex seepage conditions. The seepage conditions in different principal stress directions are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of seepage conditions in different principal stress directions.

Against this background, many researchers have conducted in-depth research on the characteristic stress under seepage conditions. Du et al. [18] conducted triaxial seepage tests on sandstone specimens containing pre-existing fractures and found that σci, σcd, and σc all showed a nonlinear increasing trend with the increase in fracture dip angle. Du et al. [19] conducted hydraulic coupling tests on sandstone specimens and found that, due to the existence of two fractures, the ratio of crack initiation threshold to peak strength and the ratio of crack damage threshold to peak strength decreased by up to 31.8% and 12.2%, respectively. Xue et al. [20] conducted triaxial seepage tests on concrete specimens and found that, when the seepage pressure increased from 1 MPa to 3 MPa, the average crack initiation stress, crack damage stress, and peak stress of the specimens decreased by 13.1%, 16.9%, and 15.6%, respectively. Kou et al. [21] conducted triaxial seepage tests on rock specimens and found that, when the seepage pressure increased, the crack initiation stress and crack damage stress of the specimens decreased. Yang et al. [22] conducted seepage tests on rock specimens and found that, as the seepage pressure increased, the initial stress and peak stress of the specimens decreased. Wei et al. [23] conducted seepage tests on rock specimens and found that, with an increase in the concave angle, both the crack initial stress of the wing crack and the peak strength of the specimens showed a trend of first decreasing and then increasing, regardless of the existence of seepage pressure. Zhang et al. [24] conducted unloading surrounding rock seepage tests on sandstone and found that, as the seepage pressure increased, crack initial stress decreased, whereas the crack damage stress and the expansion rate of peak stress increased.

The ultimate outcome of crack development is rock failure [25]. Liu et al. [26] conducted seepage tests on sandstone and found that, as the seepage pressure increased, the number of tensile cracks gradually increased, and the failure mode transformed into a tensile–shear mixed failure mode. Yang et al. [27] studied the failure process of rock mass under water pressure and found that three failure modes occurred in the rock mass under the influence of water pressure. Mei et al. [28] conducted stress–seepage coupling tests on rock masses and discovered that, under the long-term coupling effect of the two, the failure mode of the rock was directly controlled. Du et al. [19] conducted hydraulic coupling tests on rock masses and discovered that, under the condition of hydraulic–mechanical coupling, five failure modes were observed in the double-fracture specimens. Wang et al. [29] conducted experiments on rocks under uniaxial and triaxial stress paths and found that, as the water content increased, the rock specimens changed from brittle–fractured to ductile–fractured.

In conclusion, significant progress has been made in the field of characteristic stress of rocks under seepage conditions. Nevertheless, in deep engineering scenarios, the seepage direction is not limited to a single direction but rather shows multi-directional characteristics. Different seepage directions will inevitably lead to differences in characteristic stress and affect the stability of the surrounding rock. In addition, strata can be rich in mudstone [30,31], which is prone to softening when exposed to water. This characteristic may trigger geological disasters [32,33,34,35]. Mudstone serves as a natural impermeable layer; under the disturbance of engineering activities and environmental changes, the structural integrity of mudstone can be damaged, promoting the development of permeation channels and ultimately leading to the loss of its waterproof property [36]. After encountering water, due to the rich mineral content within the mudstone, its seepage characteristics become quite complex [37]. In the stability analysis of underground engineering, the study of the seepage characteristics of mudstone is of great significance [38]. Therefore, this study assesses the variation law of characteristic stress of mudstone under different seepage directions and simultaneously analyzes the influence of seepage conditions in different principal stress directions on the failure characteristics of mudstone. The findings can provide valuable references for the assessment and analysis of rock mass excavation stability under high-permeability pressure seepage conditions in different principal stress directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rock Specimen Preparation

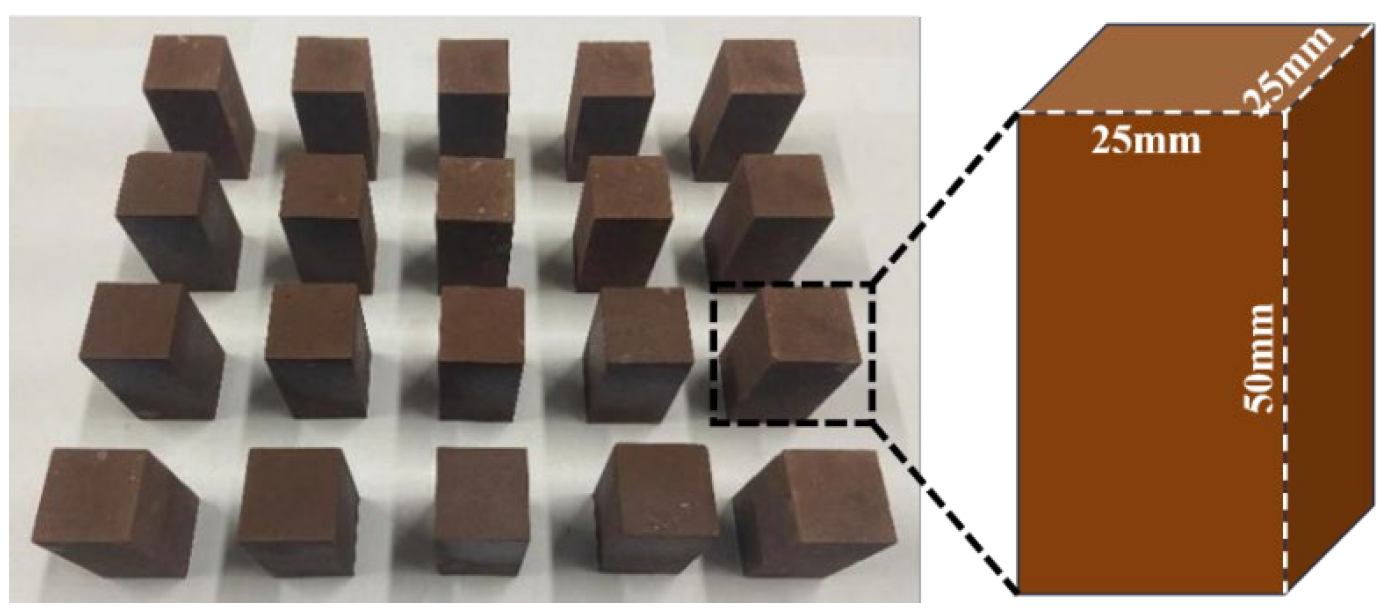

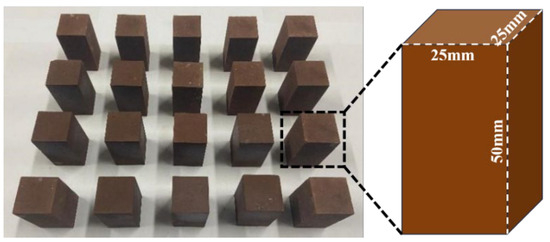

Mudstone, as a typical sedimentary rock in the shallow layer of the Earth’s crust, exhibits characteristics such as softening, disintegration, and even slurry formation when exposed to water [39]. It is widely observed in underground engineering projects. In this study, mudstone was selected as the research subject. Considering the inherent discreteness of rocks, specimens were collected from the same parent rock and then processed using an automatic rock-cutting machine and a grinding machine. To preserve the integrity of the specimens, water-cooled lubrication was maintained throughout the processing with low-speed and stable cutting and grinding operations. The final dimensions of the processed specimens were 25 mm × 25 mm × 50 mm. The processed rock specimens are presented in Figure 2. Following processing, unqualified specimens with obvious surface defects or substantial disparities in appearance were eliminated. Afterwards, rock specimens with similar wave velocities were selected through wave velocity monitoring to further reduce the discreteness. The average wave velocity of the final selected specimens is 2.451 km/s.

Figure 2.

The mudstone specimens.

2.2. Test Equipment

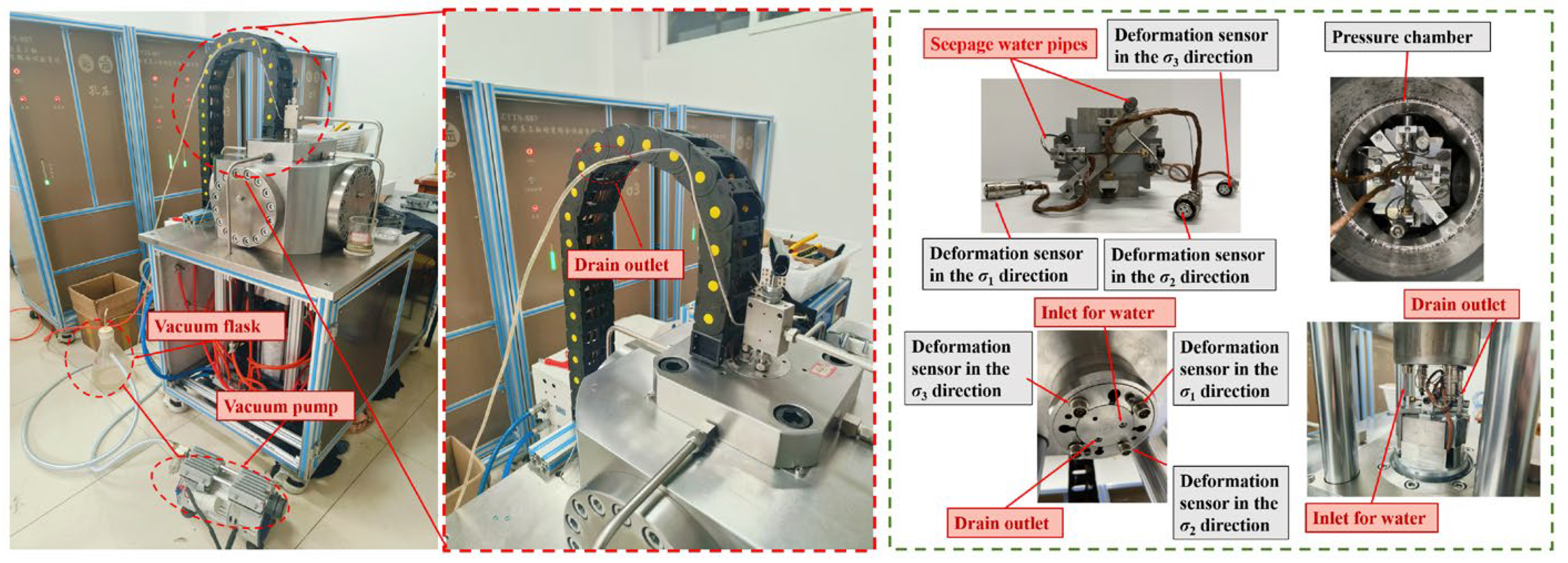

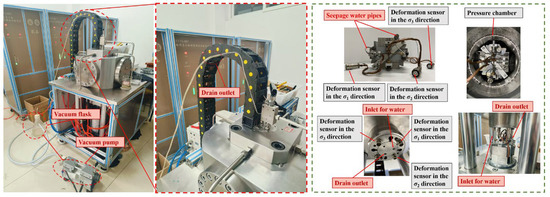

As illustrated in Figure 3, the ZTTS-887 true triaxial testing instrument (Changchun Zhantuo Geotechnical Instruments, Ltd., Changchun City, China) was used for the tests. This system utilizes a loading configuration consisting of two rigid axes and one flexible axis, combined with dual-cylinder linkage servo control to ensure synchronized loading. The maximum values of σ1, σ2, and σ3 are 800 MPa, 70 MPa, and 70 MPa, respectively. Meanwhile, the maximum permeation pressure (σp) that can be achieved is 40 MPa. The testing system allows for independent control in various principal stress directions. Moreover, it can perform seepage tests either along the σ1 direction or along the σ2 direction.

Figure 3.

True triaxial test system.

2.3. Test Scheme

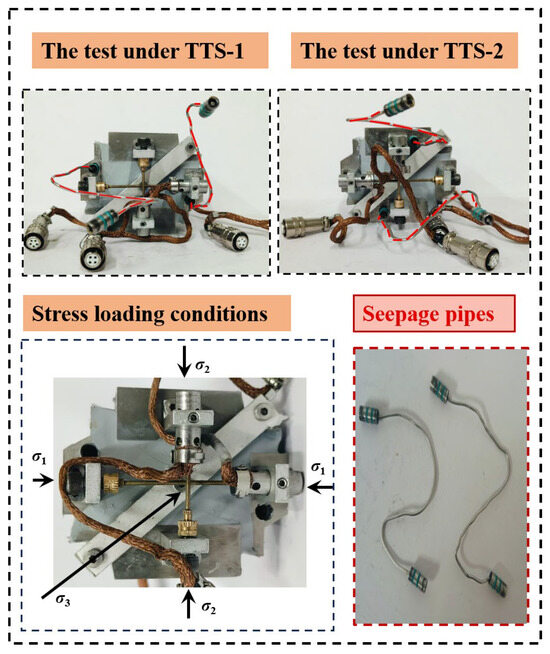

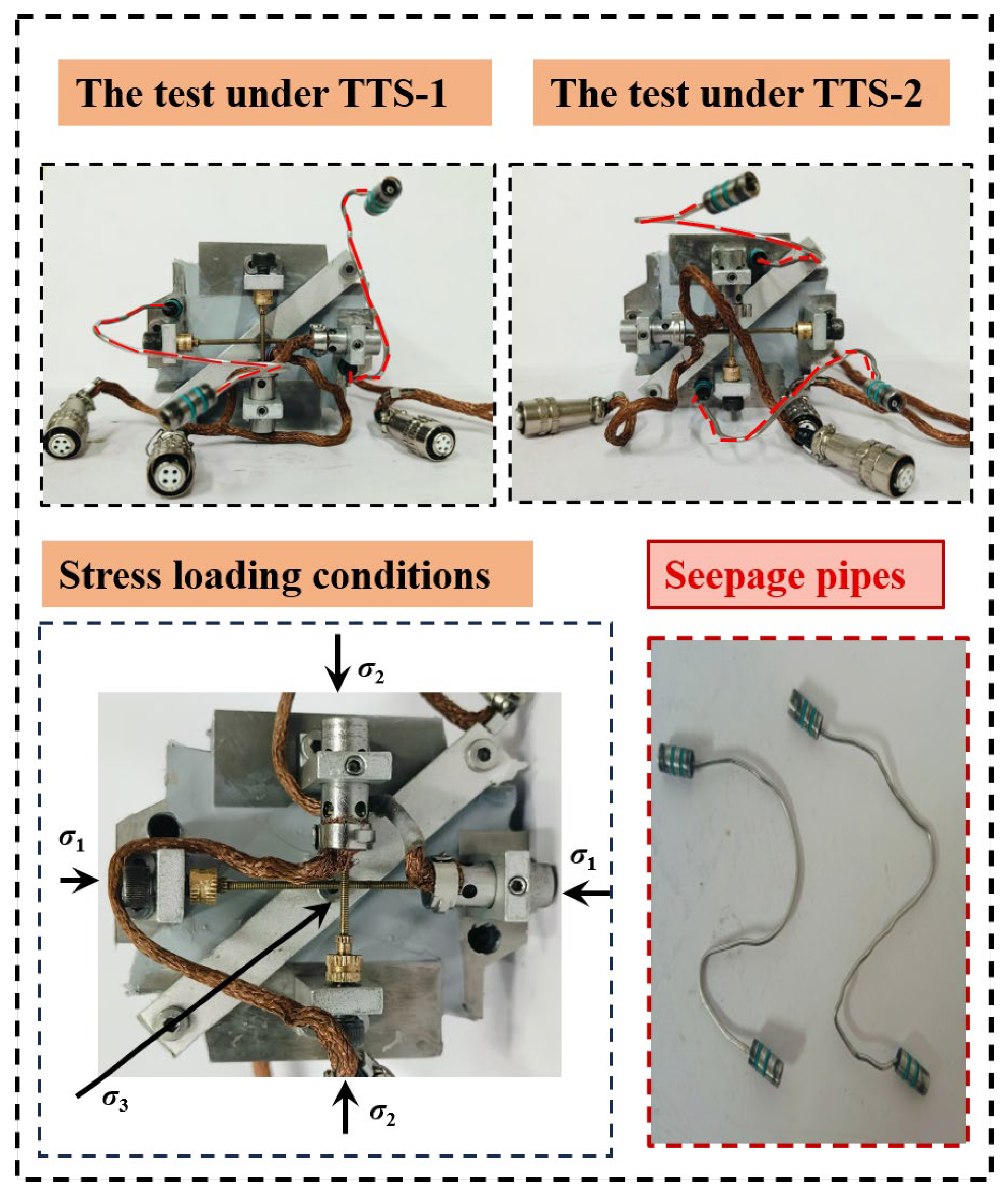

The test design included three different permeation pressures and three different intermediate principal stresses. True triaxial seepage tests were conducted with the seepage direction aligned with the σ1 direction and the σ2 direction, respectively. In this study, TTS-1 is defined as the test condition in which the seepage direction is parallel to the σ1 direction, whereas TTS-2 refers to the condition where the seepage direction is aligned with the σ2 direction. Specimens with different seepage directions are shown in Figure 4. The test parameters are listed in Table 1 below, and the detailed procedures are as follows:

(1) The deformation sensors were installed. When conducting the seepage test along the σ1 direction, the seepage pipes were installed along the seepage channel in the σ1 direction (when conducting the seepage test along the σ2 direction, the seepage pipes were installed along the seepage channel in the σ2 direction). Then, the pressure chamber was closed.

(2) Continuous vacuuming was performed for a duration of one hour to facilitate the internal saturation of the rock specimen. Seepage could be carried out after the flow rate at the outlet end had stabilized.

(3) The specimen was loaded to the hydrostatic pressure state where σ1 = σ2 = σ3 = 12 MPa, and σp was continuously applied.

(4) σ3 and σp were kept constant while simultaneously loading σ1 and σ2 to their preset values at an identical rate. The loading path is illustrated in Figure 5.

(5) σ2, σ3, and σp were kept constant, and then σ1 was loaded at a constant rate until rock specimen failure occurred.

Figure 4.

Specimens with different seepage directions.

Figure 4.

Specimens with different seepage directions.

Table 1.

The parameters of true triaxial seepage tests.

Table 1.

The parameters of true triaxial seepage tests.

| Seepage Direction | σ1 (MPa) | σ2 (MPa) | σ3 (MPa) | σp (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No seepage | Loaded to failure | 16, 20, 24 | 12 | 0 |

| TTS-1, TTS-2 | 1, 5, 9 |

Figure 5.

Stress path diagram.

Figure 5.

Stress path diagram.

3. Results

3.1. The True Triaxial Loading Test Under Different Seepage Directions

The permeability of the rock specimens in this seepage test was determined through the steady-state method. Many researchers make the following assumptions when using the steady-state method [40,41,42]: (1) the seepage water is an incompressible fluid; (2) the initial distribution of pores and micro-cracks within the rock mass is relatively uniform and can be regarded as a porous medium; and (3) constant-pressure stable seepage is considered continuous seepage. During the testing process, the measurements and calculations of permeability adhered strictly to Darcy’s Law. The specific formula employed for permeability calculation is presented below [43]:

where k denotes the permeability of the rock (m2); Q denotes the fluid flow rate (m3/s); μ denotes the average viscosity coefficient of the fluid (Pa∙s); P0 denotes the standard atmospheric pressure (Pa); L denotes the length of the rock specimen (m); P1 denotes the fluid pressure at the inlet end (Pa); A denotes the cross-sectional area of the rock specimen (m2).

The fluid flow rate was measured using the true triaxial testing system. In this study, the μ value at 25 °C was taken as 8.90 × 10−4 Pa·s. The cross-sectional area A of the specimen was 6.25 × 10−4 m2.

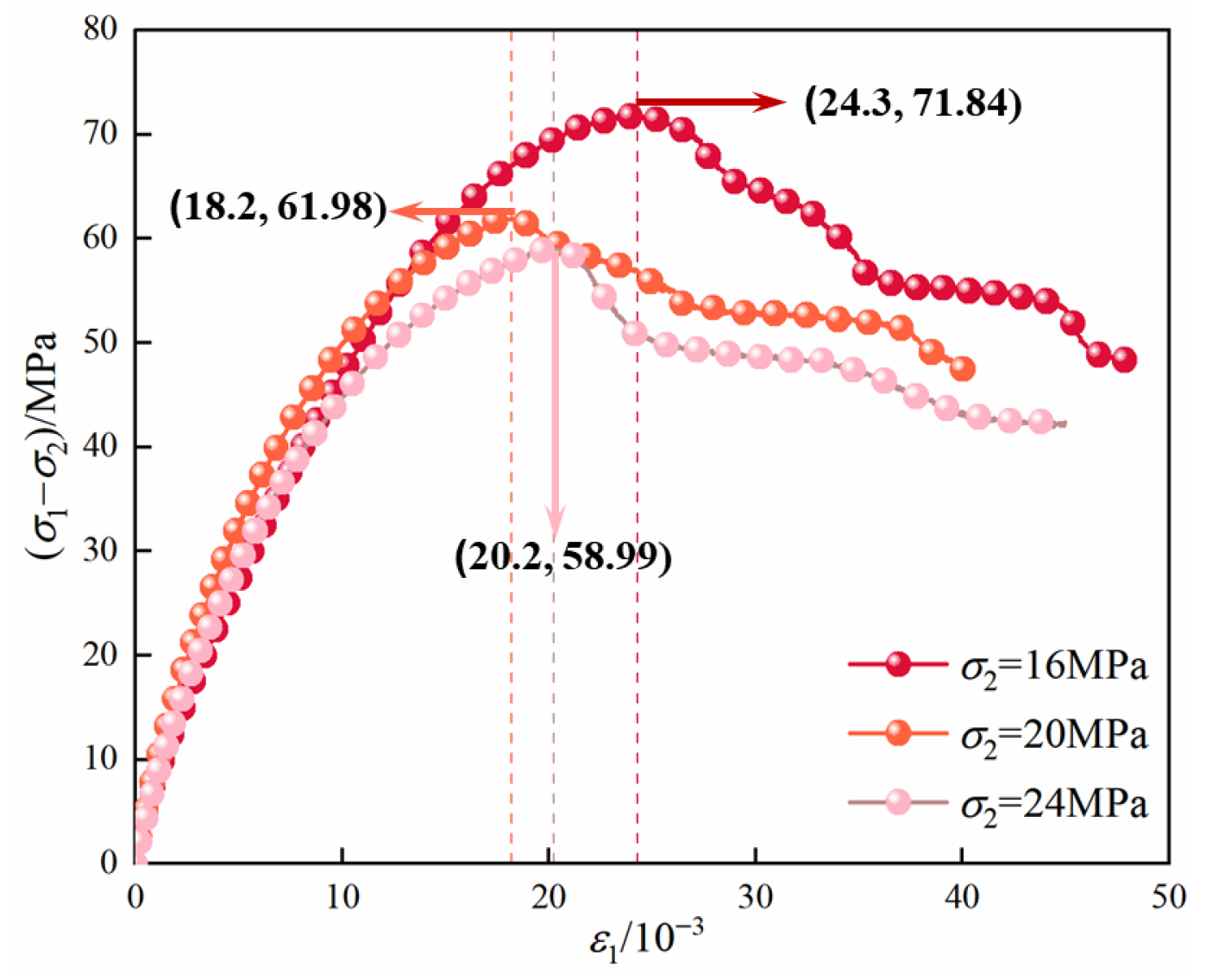

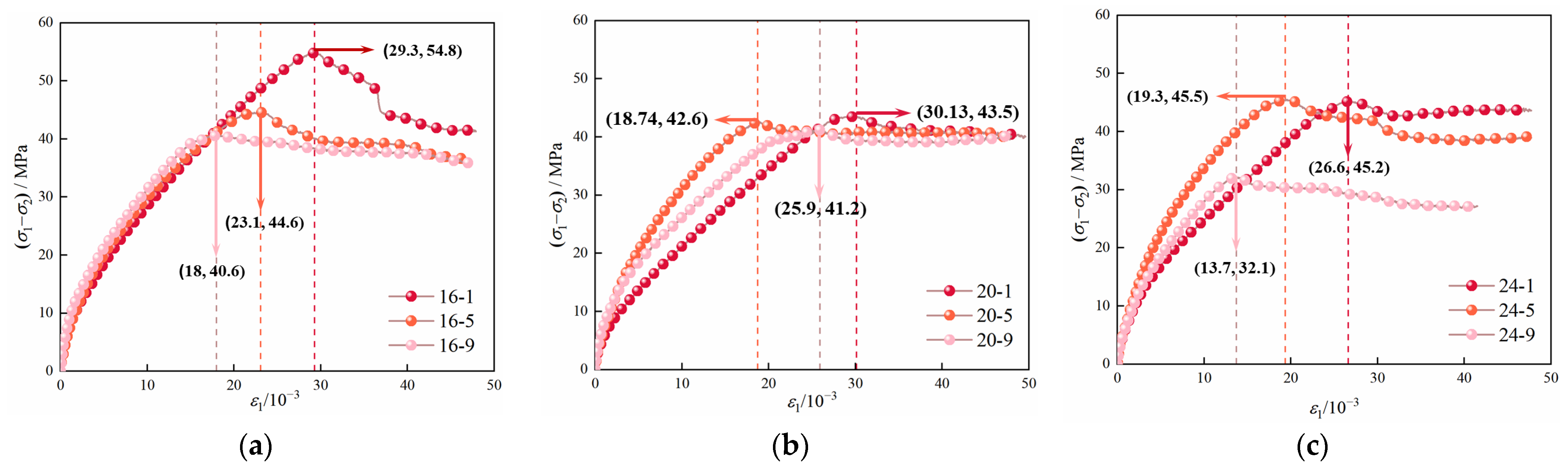

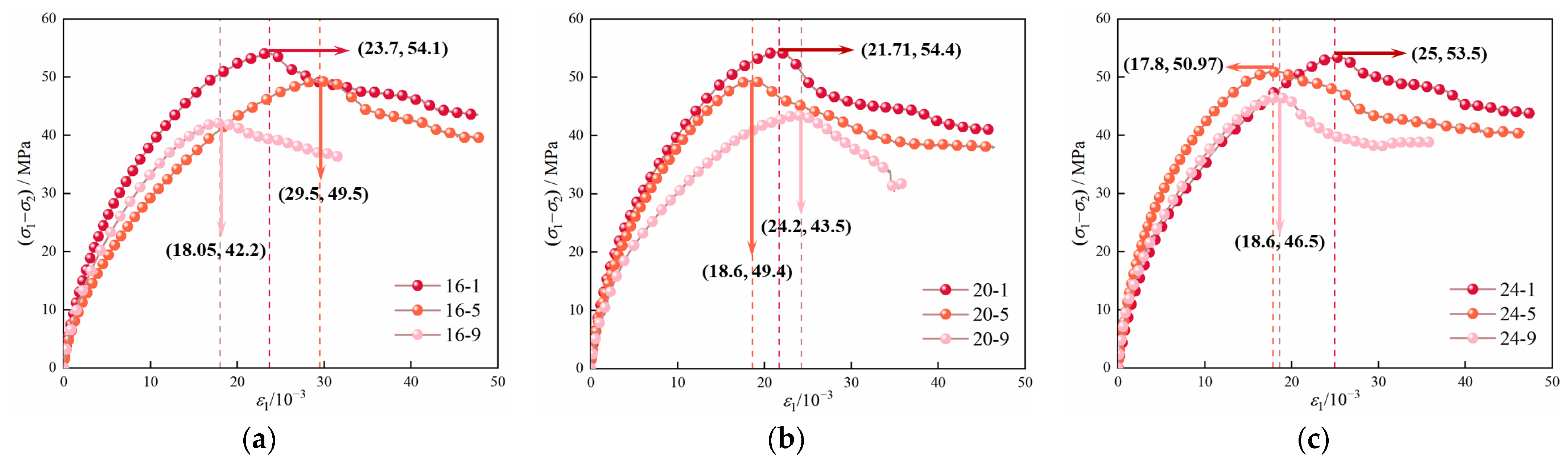

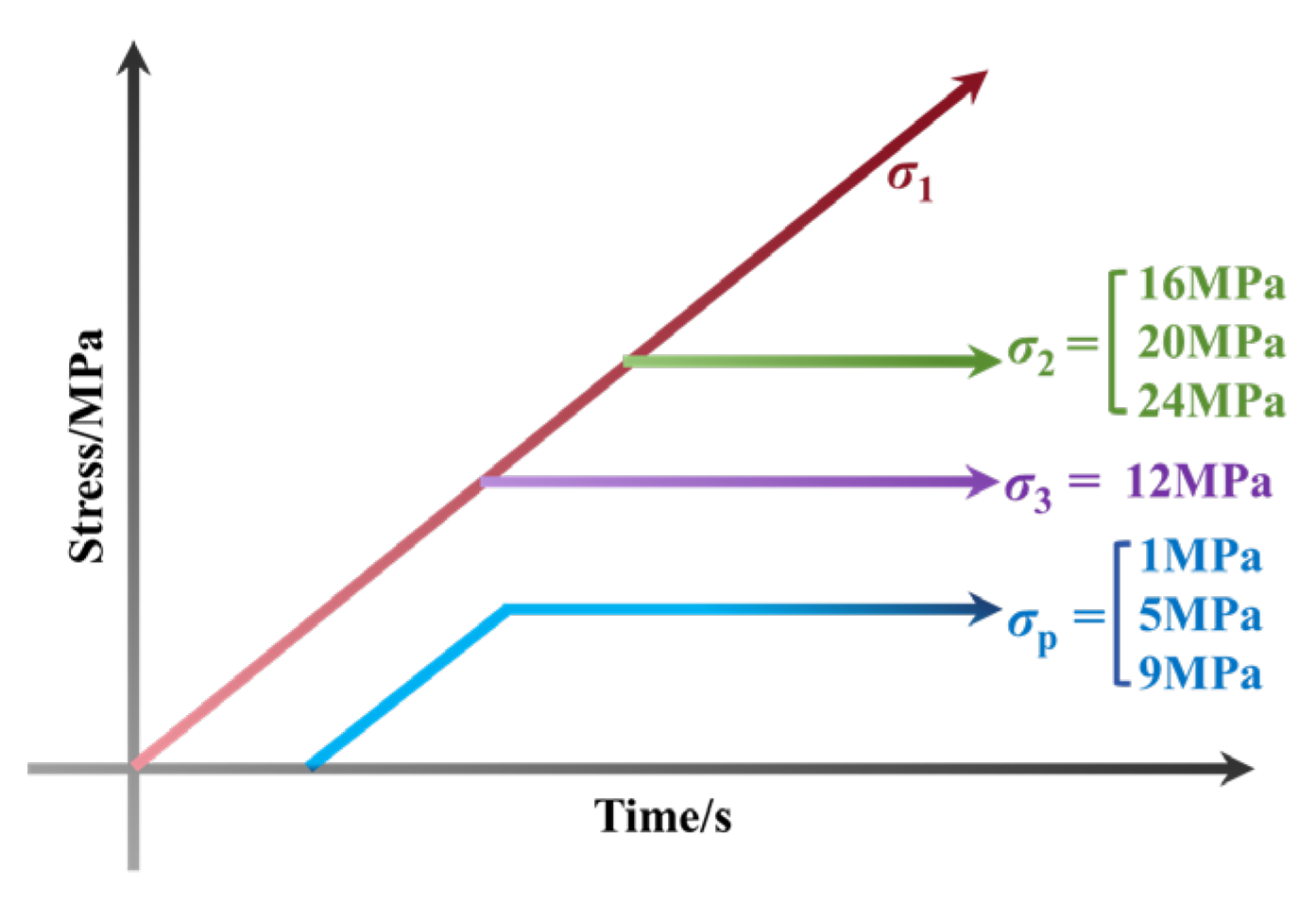

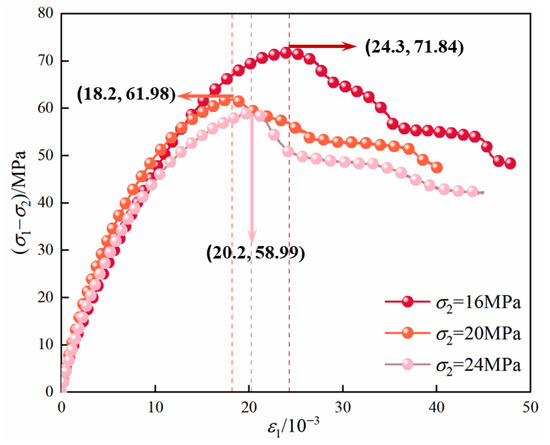

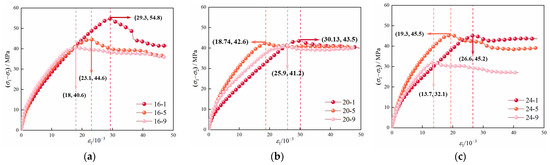

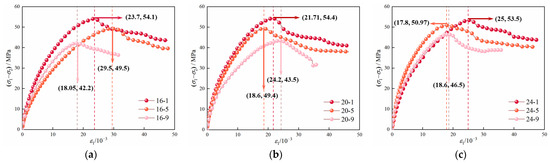

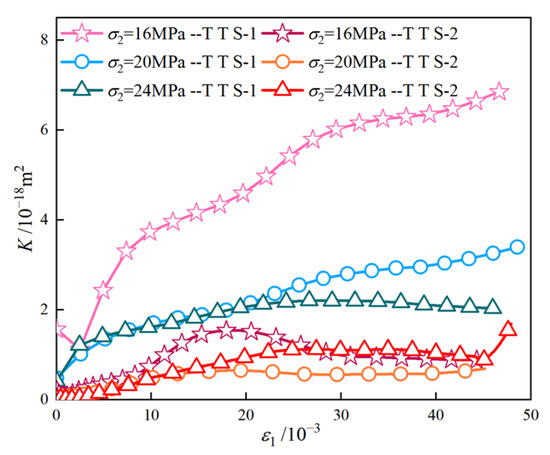

The stress–strain curves of mudstone under different seepage directions and non-seepage conditions are shown in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. In these figures, 16-1 indicates that σ2 is 16 MPa, σp is 1 MPa, and the meanings of the other legends are similar. It is evident from Figure 7 and Figure 8 that, under the same σ2, the peak stress σf of mudstone decreases as σp increases. Taking the case of σp = 1 MPa as an example, the relationship between the permeability and strain of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions is analyzed, as shown in Figure 9. As can be observed from the figure, after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, permeability significantly decreases. The analysis suggests that, as the maximum principal stress generates fractures with a smaller angle to its direction during loading [44,45], under the seepage condition in the direction of the intermediate principal stress, the permeability may decrease due to the obstruction of water flow by the fractures. Specifically, when σ2 is 16 MPa, permeability decreases by 5.85 × 10−18 m2; when σ2 is 20 MPa, permeability decreases by 2.71 × 10−18 m2; and when σ2 is 24 MPa, permeability decreases by 0.93 × 10−18 m2. Under the TTS-2 condition, permeability decreases as σ2 increases.

Figure 6.

Stress–strain curves of mudstone under non-seepage condition.

Figure 7.

Stress–strain curves of mudstone under TTS-1: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa; (b) σ2 = 20 MPa; (c) σ2 = 24 MPa.

Figure 8.

Stress–strain curves of mudstone under TTS-2: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa; (b) σ2 = 20 MPa; (c) σ2 = 24 MPa.

Figure 9.

Permeability–strain curves of mudstone under different seepage directions when σp is 1 MPa.

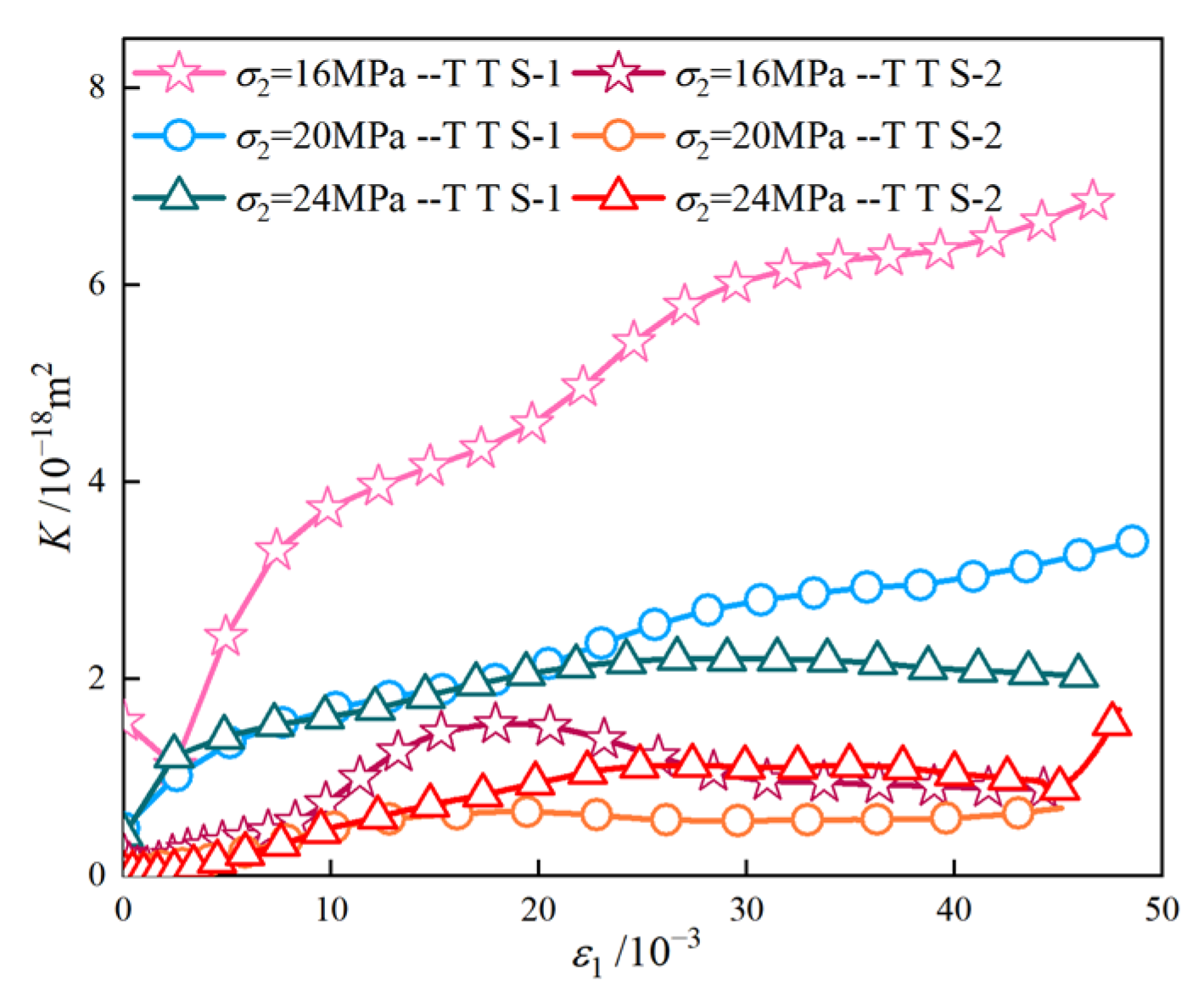

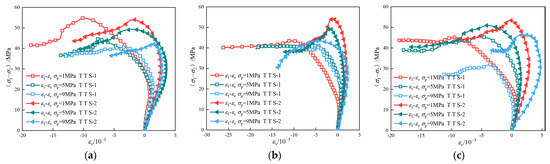

Figure 10 illustrates the stress–volumetric strain curves of mudstone under different seepage directions. As deformation progresses, the volumetric strain initially increases and then gradually tends towards stabilization.

Figure 10.

Stress–volumetric strain curves of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa; (b) σ2 = 20 MPa; (c) σ2 = 24 MPa.

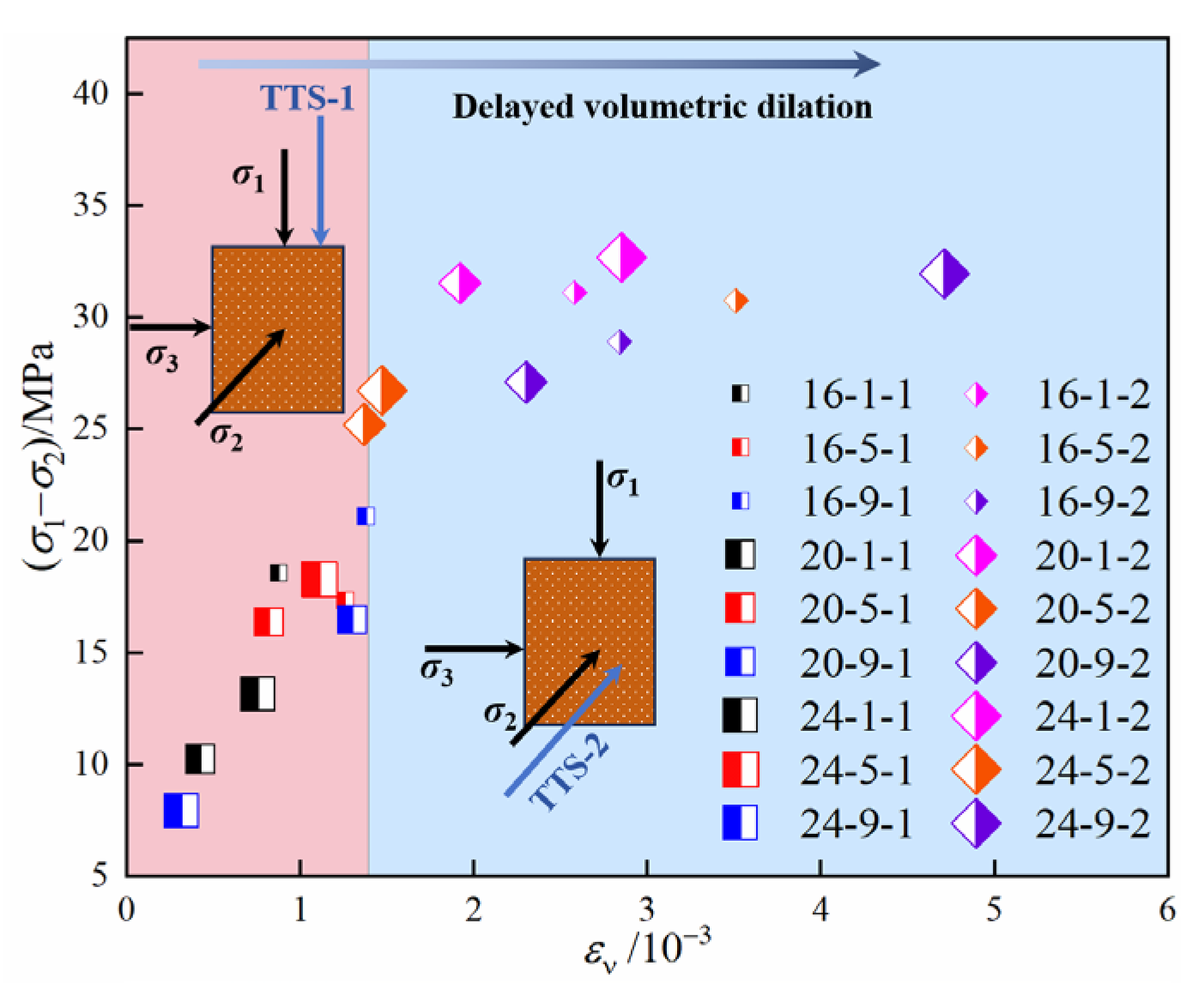

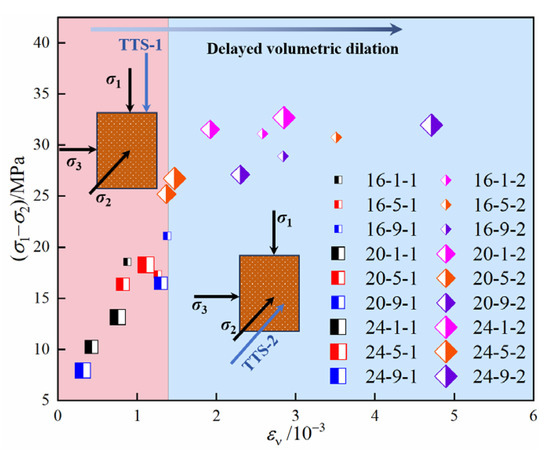

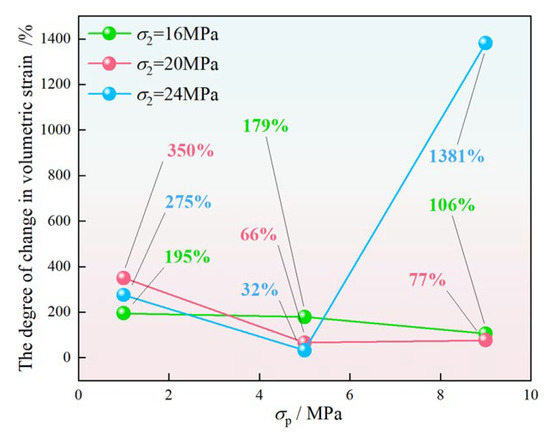

Figure 11 shows the volumetric dilation points of mudstone under different seepage directions. In this figure, 16-1-1 indicates that σ2 is 16 MPa, σp is 1 MPa, the seepage direction is as in the TTS-1 condition, and the meanings of the other legends are similar. The dividing line in Figure 11 separates the volumetric dilation points under seepage conditions in the σ1 and σ2 directions. It is located between the maximum value of volumetric strain under seepage in the σ1 direction and the minimum value under seepage in the σ2 direction, indicating that all volumetric dilation points under the σ2 direction seepage condition are greater than those under the σ1 direction condition. This observation suggests a hysteresis effect in volumetric dilation. After TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, the volumetric dilation of mudstone is notably delayed. To quantify the change in volumetric strain, its relative change was computed as the difference between εv under TTS-2 and εv under TTS-1, divided by εv under TTS-1. Considering the conditions of σ2 being 16 MPa and σp being 9 MPa as an example, under TTS-1 conditions, εv = 0.138%, and under TTS-2 conditions, εv = 0.284%. Therefore, the value of volume dilation hysteresis under these conditions is (0.284% − 0.138%)/0.138% = 106%.

Figure 11.

Volumetric dilatancy points of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions.

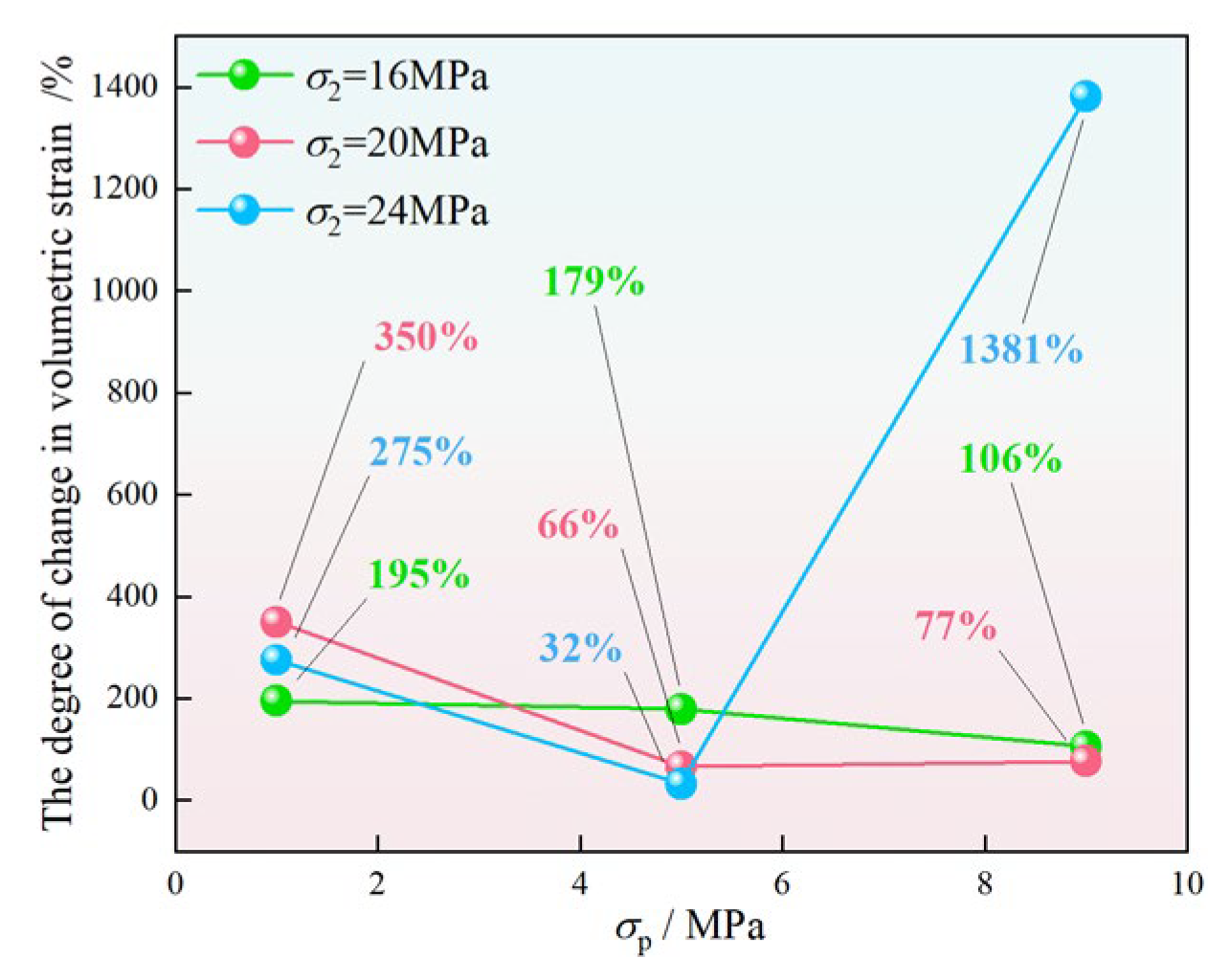

As shown in Figure 12, the average volumetric strain change rate of 296% is obtained by summing all the data in Figure 12 and then taking the average. The maximum variation (1381%) occurs under the conditions of high σ2 and high σp. As demonstrated above, a volumetric dilation hysteresis effect of mudstone can be discovered when the seepage direction is in the TTS-2 condition.

Figure 12.

Degree of change in volumetric strain under different seepage directions.

3.2. The Characteristic Stress of Mudstone Under Different Seepage Directions

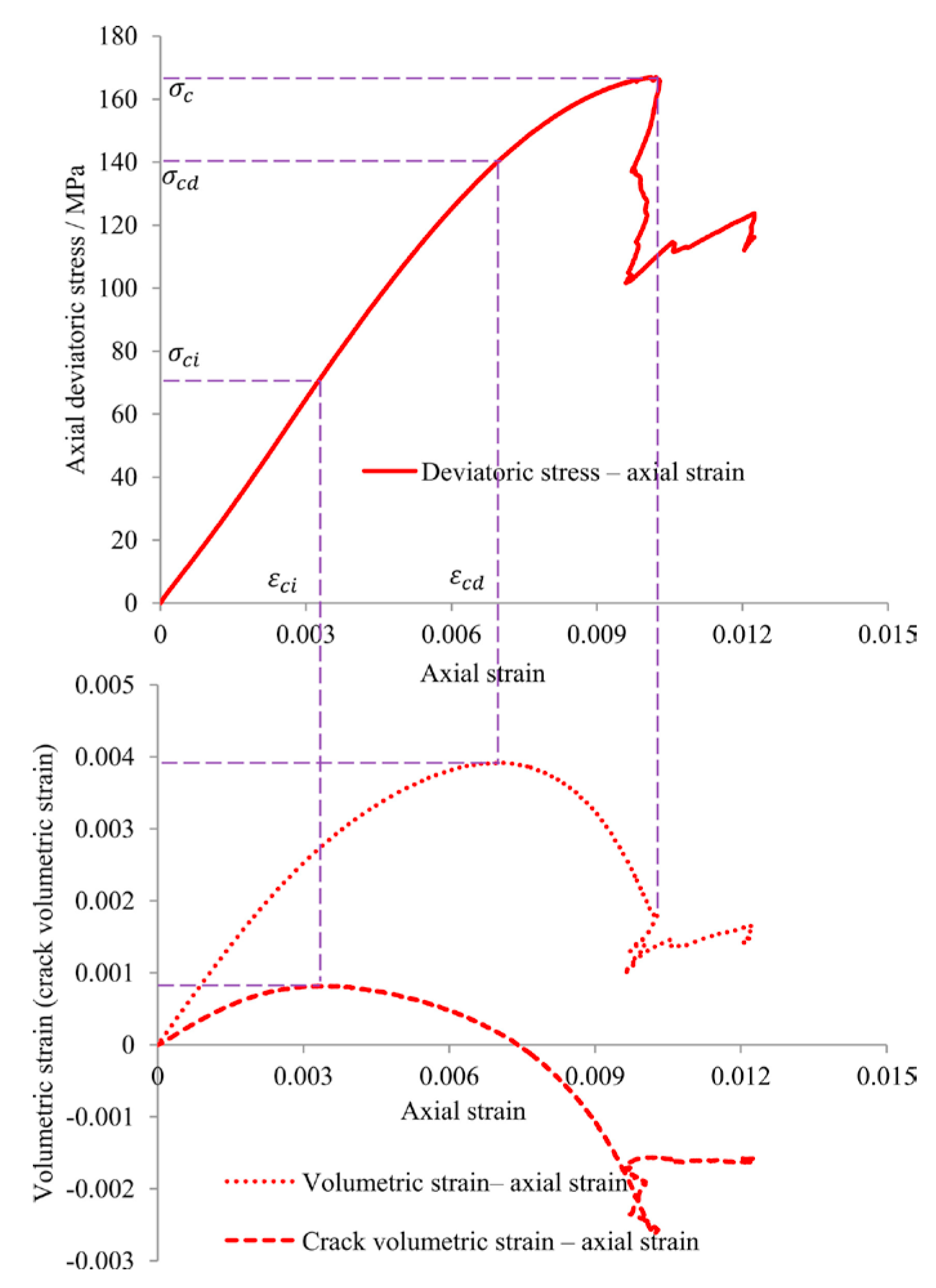

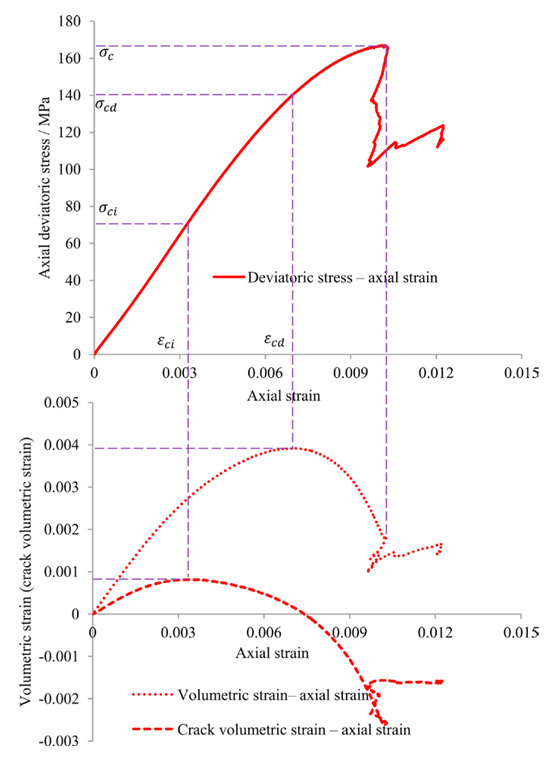

Many researchers have conducted research on the determination methods for crack initiation stress σci and crack damage stress σcd; for example, the fracture volume strain method for determining crack initiation stress σci and crack damage stress σcd and the acoustic emission method for determining crack initiation stress σci and crack damage stress σcd were studied in [46,47,48]. The schematic diagrams of these stresses and strains are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagrams of peak stress (σc), crack initiation stress (σci), crack damage stress (σcd), crack initiation strain (εci), and crack damage strain (εcd) [49].

In this study, the crack initiation stress σci and crack damage stress σcd were determined using the fracture volumetric strain method, which involves utilizing the fracture volumetric strain and the inflection point of the volumetric strain curve to ascertain the values of these two stresses. The volumetric strain of mudstone can be composed of elastic volumetric strain and fracture volumetric strain, which is calculated as follows [50,51]:

where εv represents the volumetric strain; represents the crack volumetric strain; represents the elastic volumetric strain; E represents the elastic modulus; υ represents Poisson’s ratio; σ1 represents the maximum principal stress; σ2 represents the intermediate principal stress; and σ3 represents the minimum principal stress.

In accordance with Equations (2) and (3), the fracture volumetric strain can be calculated as follows:

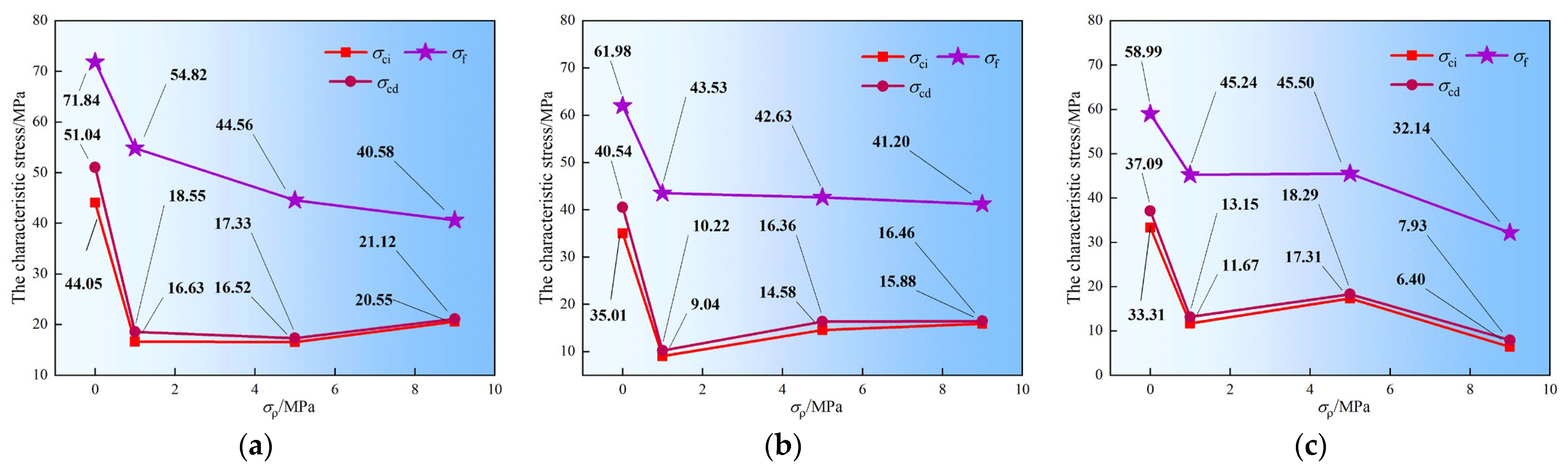

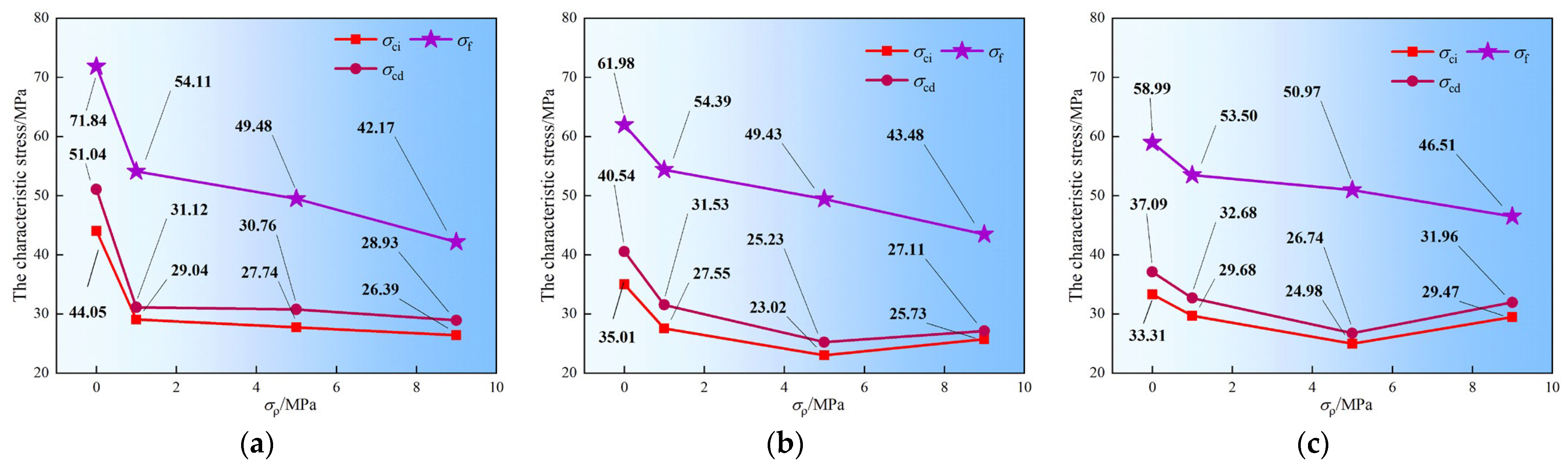

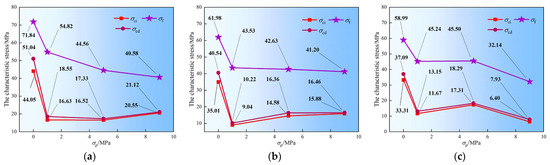

The characteristic stress curves of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions are presented in Figure 14 and Figure 15. Overall, under the influence of σp, all characteristic stresses decrease. Figure 14 shows that, under the TTS-1 condition, σf decreases as σp increases. The analysis shows that, under constant σ2 conditions, an increase in σp leads to a gradual decrease in the strength of mudstone, attributable to the reduction in effective stress and its inherent softening behavior upon exposure to water. In addition, at σ2 = 16 MPa and 20 MPa, σci and σcd increase as σp rises from 1 MPa to 9 MPa, showing similar growth trends. When σ2 is 24 MPa, their maximum values all occur when σp is 5 MPa. The minimum values of these two parameters all occur when σp reaches 9 MPa.

Figure 14.

Characteristic stresses of mudstone under TTS-1: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa; (b) σ2 = 20 MPa; (c) σ2 = 24 MPa.

Figure 15.

Characteristic stresses of mudstone under TTS-2: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa; (b) σ2 = 20 MPa; (c) σ2 = 24 MPa.

The characteristic stress of the mudstone shows significant differences under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions. The characteristic stress curves of mudstone under the TTS-2 condition are presented in Figure 15. When σ2 is 16 MPa, both σci and σcd exhibit a decreasing trend as σp increases from 1 MPa to 9 MPa. Conversely, under the TTS-1 condition, both σci and σcd demonstrate an overall increasing trend. Under the TTS-2 condition, when σ2 is 20 MPa and σp rises to 9 MPa, σf decreases, while the values of σci and σcd generally show a downward trend. In contrast, under the TTS-1 condition, both σci and σcd show an increasing trend.

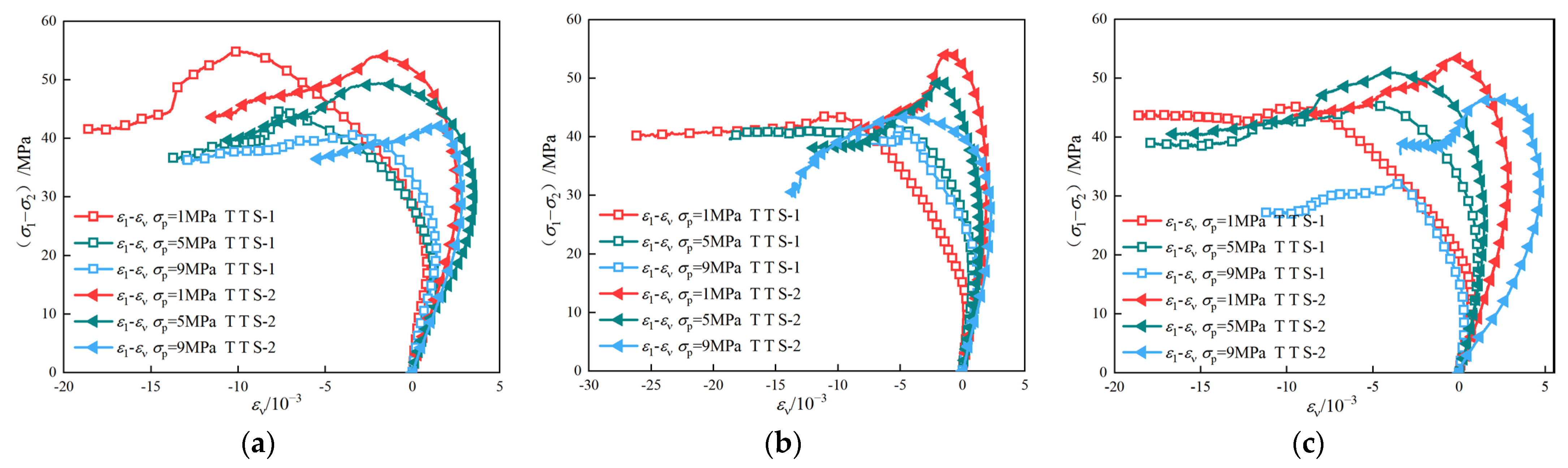

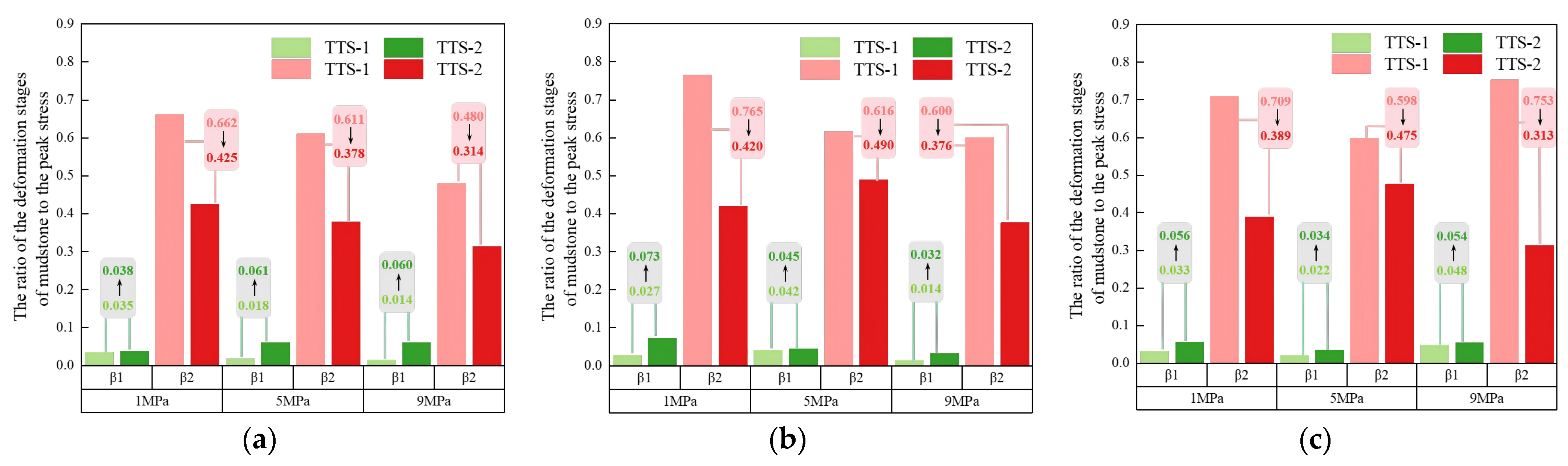

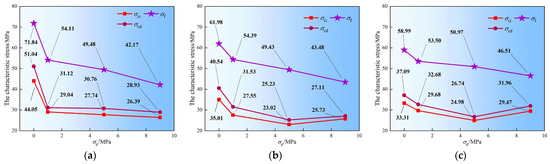

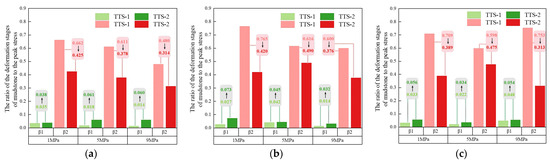

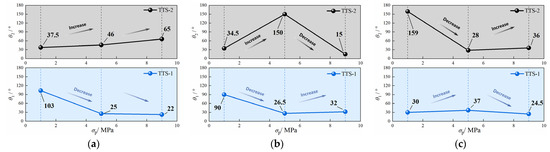

β1 is defined as the ratio of (σcd − σci) to σf, and β2 is defined as the ratio of (σf − σcd) to σf. In this formula, σf denotes is the corresponding peak stress under different σp. Figure 16 presents the ratio of the deformation process of mudstone to the peak stress under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions. Under constant σ2 conditions, β1 increases after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, while β2 decreases. Consequently, after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, the stable crack propagation stage of mudstone is prolonged, while the unstable crack propagation stage is shortened.

Figure 16.

Ratio of deformation stage to peak stress of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa; (b) σ2 = 20 MPa; (c) σ2 = 24 MPa.

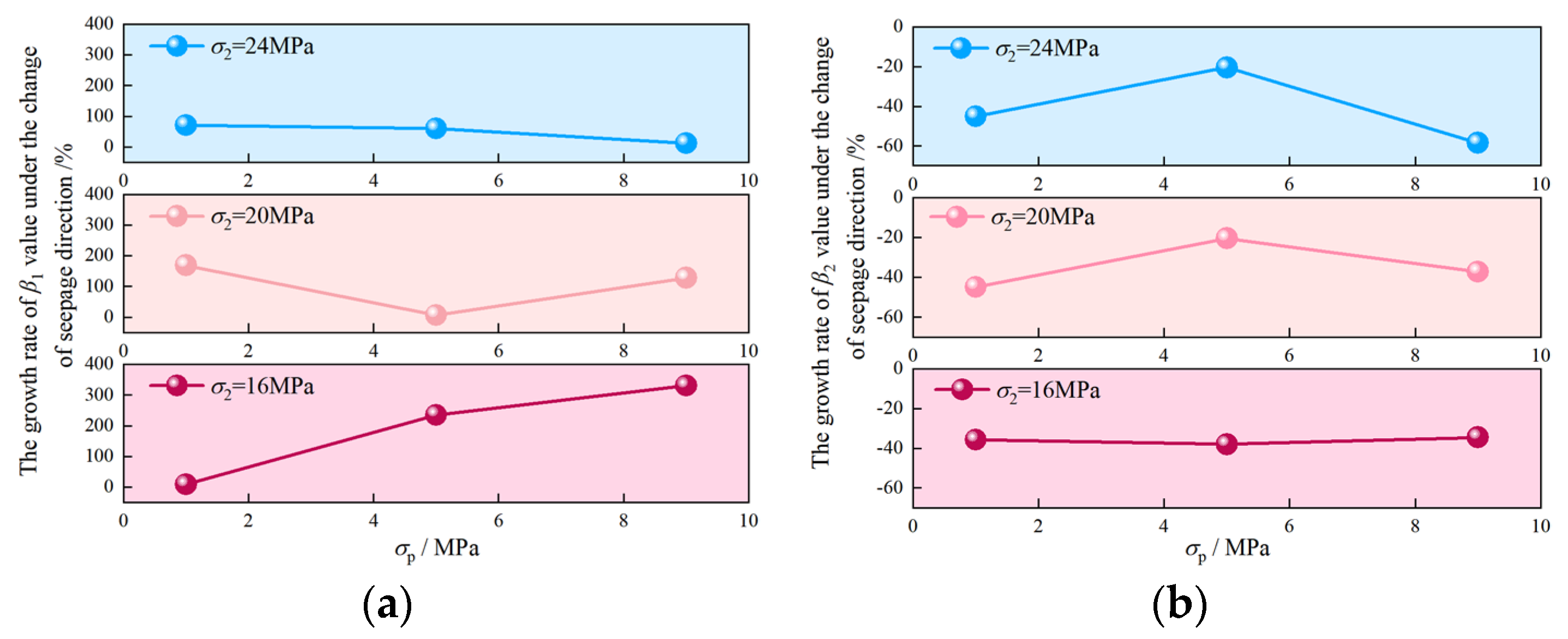

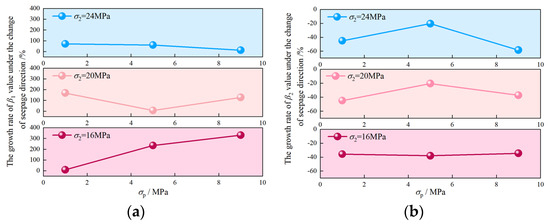

Its change was computed as the difference between βi under TTS-2 and βi under TTS-1, divided by βi under TTS-1 (i = 1, 2). It is evident from Figure 17 that, after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, β1 shows a growth range from 6.7% to 330.8%. At σ2 = 16 MPa, β2 decreases by 35.8%, 38.1%, and 34.5%, respectively. At σ2 = 20 MPa, β2 decreases by 45.1%, 20.5%, and 37.3%, respectively. At σ2 = 24 MPa, β2 decreases by 45.1%, 20.5%, and 58.5%, respectively. This implies an increased likelihood of sudden instability in mudstone and a reduced response time for engineering projects to address potential disasters.

Figure 17.

Relative change rates of β1 and β2 after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2: (a) β1 and (b) β2.

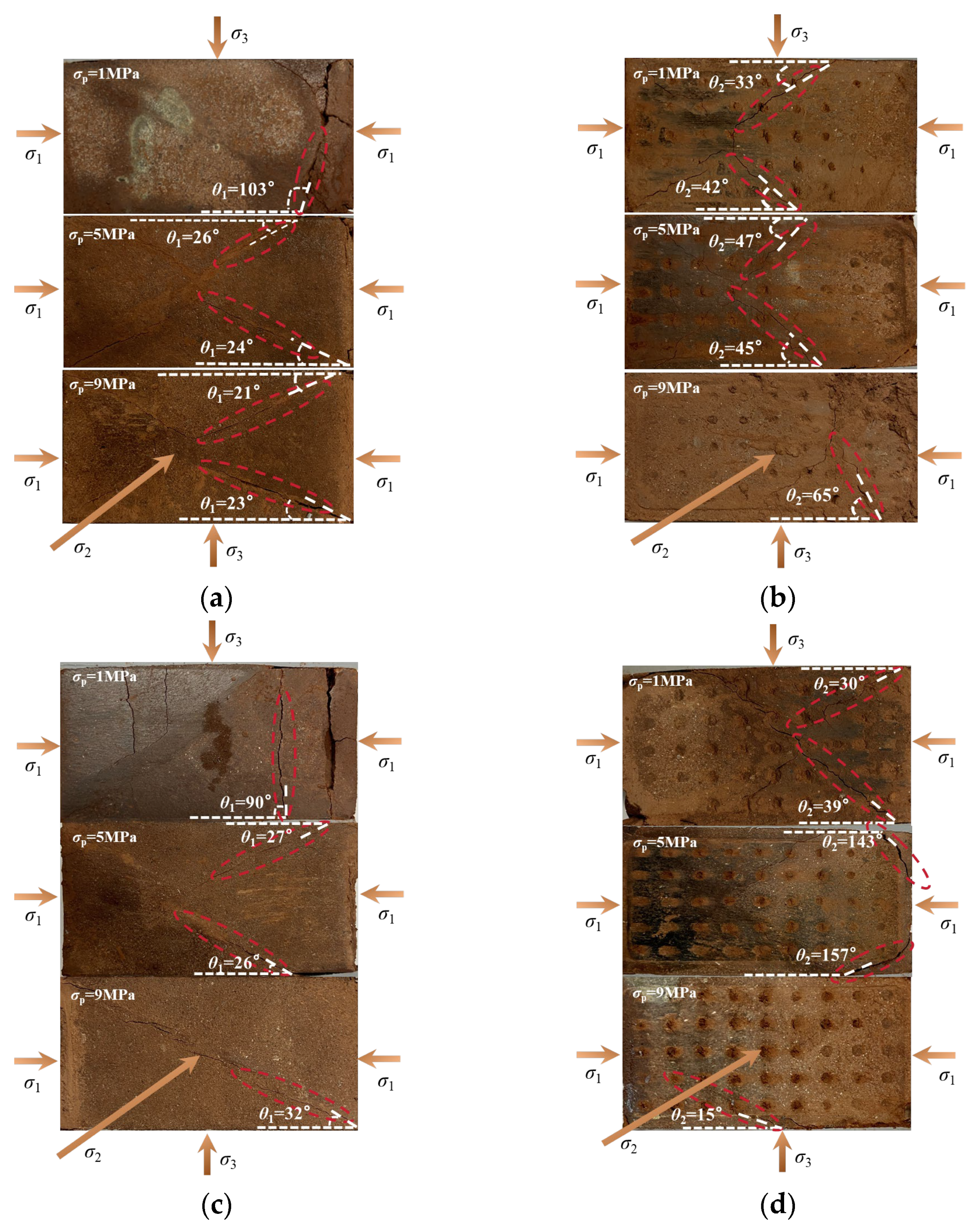

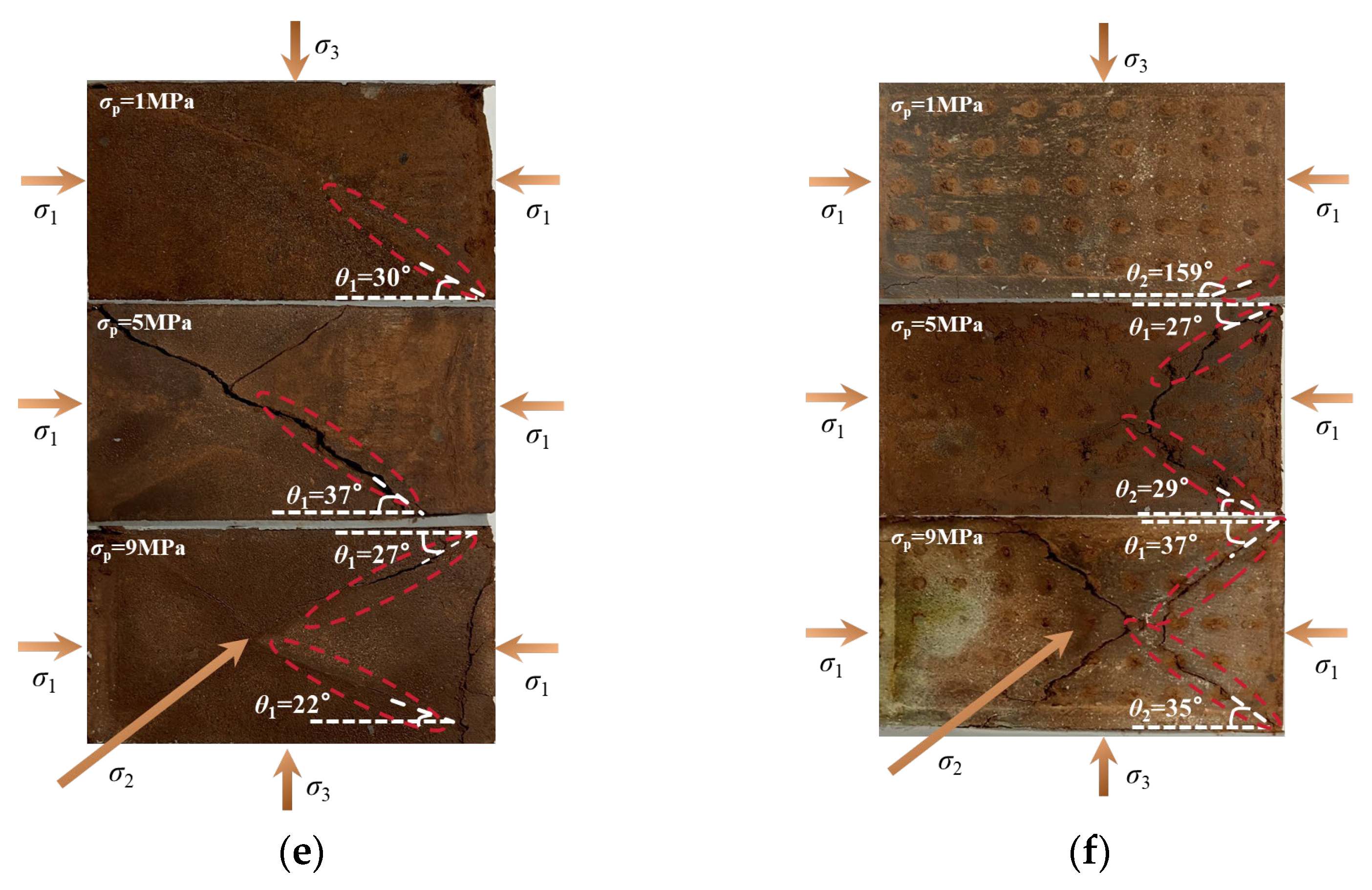

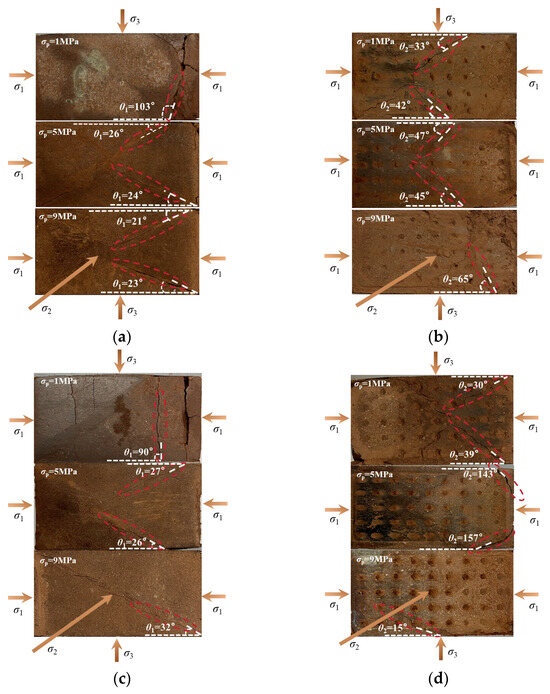

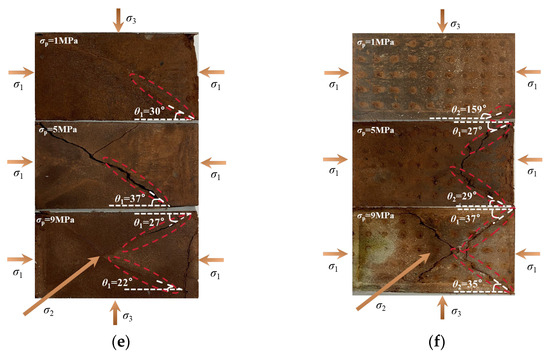

3.3. Failure Modes of Mudstone Under Different Seepage Directions

Figure 18 illustrates the failure modes of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions. The specific method for measuring the rock fracture angle is as follows: After the rock specimen fails, take a photo of its σ1–σ3 plane, crop the photo as per the format shown in Figure 18 of this article, and then use an online protractor to take multiple measurements [52,53]. In the σ1–σ3 plane, let θ1 denote the angle between the fracture surface and the σ1 direction under the TTS-1 condition, and let θ2 represent the corresponding angle under the TTS-2 condition. As shown in Figure 18a,b, under the TTS-1 condition at σp = 1 MPa, the measured θ1 is 103°. This suggests that, under lower σp, the fracture surface of the mudstone forms a larger angle with the σ1 direction. With increasing σp, θ1 gradually decreases, indicating that the mudstone fracture surface progressively converges towards the σ1 direction. This trend indicates that, under high-σp conditions, the fracture surface of mudstone is more inclined to be consistent with the σ1 direction. However, under the TTS-2 condition, θ2 increases as σp rises. This indicates that, as σp increases, the fracture surface of mudstone progressively deviates from the σ1 direction. When σ2 = 16MPa and σp = 1 MPa, under the TTS-2 condition, at a lower σp, the angle between the fracture surface of the mudstone and the σ1 direction is smaller, and the fracture surface is relatively close to the σ1 direction.

Figure 18.

Failure modes of mudstone: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa (TTS-1) and (b) σ2 = 16 MPa (TTS-2); (c) σ2 = 20 MPa (TTS-1) and (d) σ2 = 20 MPa (TTS-2); (e) σ2 = 24 MPa (TTS-1) and (f) σ2 = 24 MPa (TTS-2).

When σ2 is 20 MPa under the TTS-1 condition, as σp increases, the angle θ1 first decreases and then increases. After the seepage direction shifts from TTS-1 to TTS-2, the variation in the angle θ2 shows an inverse trend, increasing first and then decreasing. Under the TTS-1 condition with σ2 = 24 MPa, as σp increases, the angle θ1 first increases and then decreases. After the seepage direction shifts from TTS-1 to TTS-2, the variation in the angle θ2 shows an inverse trend, decreasing first and then increasing.

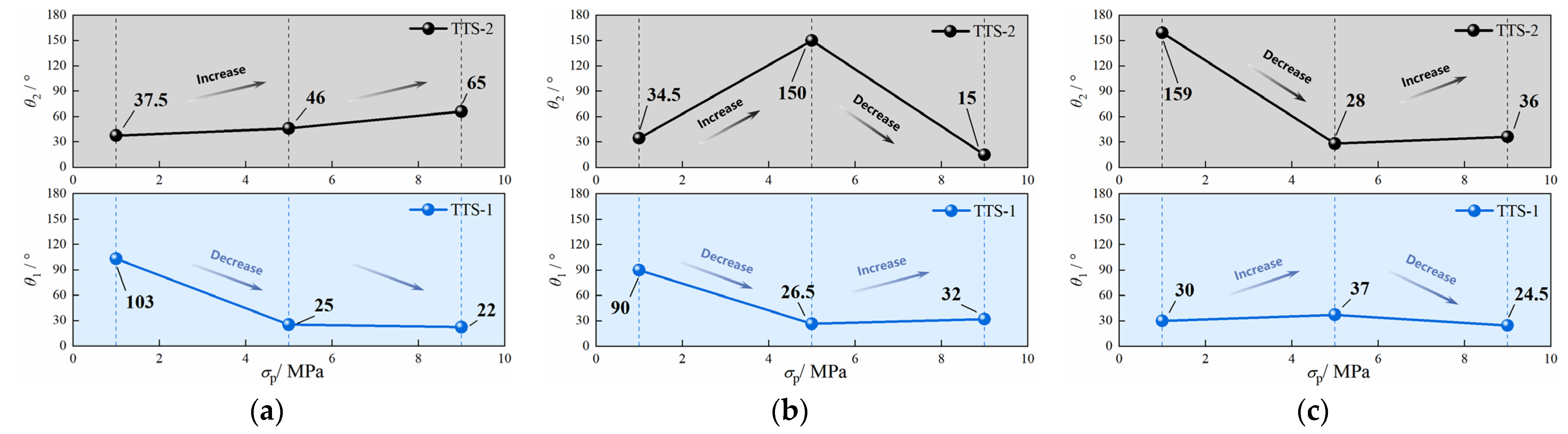

Figure 19 shows the variation pattern of the angle between the fracture surface and the σ1 direction under different seepage directions. If the mudstone fracture angles in Figure 18 contain both upper and lower angles, then the angle in Figure 19 is the average of these two angles. Under the TTS-1 condition, at σ2 = 16 MPa, θ1 decreases from 103° to 22° as the σp increases. At σ2 = 20 MPa, as σp increases, θ1 decreases from 90° to 26.5° and then increases to 32°. At σ2 = 24 MPa, as σp increases, θ1 increases from 30° to 37° and then decreases to 24.5°. Under the TTS-2 condition, at σ2 = 16 MPa, θ2 increases from 37.5° to 65° as the σp increases. At σ2 = 20 MPa, the measured values of θ2 show a non-monotonic trend with the increase in σp. They rise from 34.5° to 150° before dropping to 15°. At σ2 = 24 MPa, as σp increases, θ2 decreases from 159° to 28° and then increases to 36°. Based on the above findings, it can be concluded that the change in the seepage direction reverses the trend of the variation in the angles θ1 and θ2 with the increase in σp.

Figure 19.

Angle between fracture surface and σ1 direction under different seepage directions: (a) σ2 = 16 MPa; (b) σ2 = 20 MPa; (c) σ2 = 24 MPa.

4. Discussion

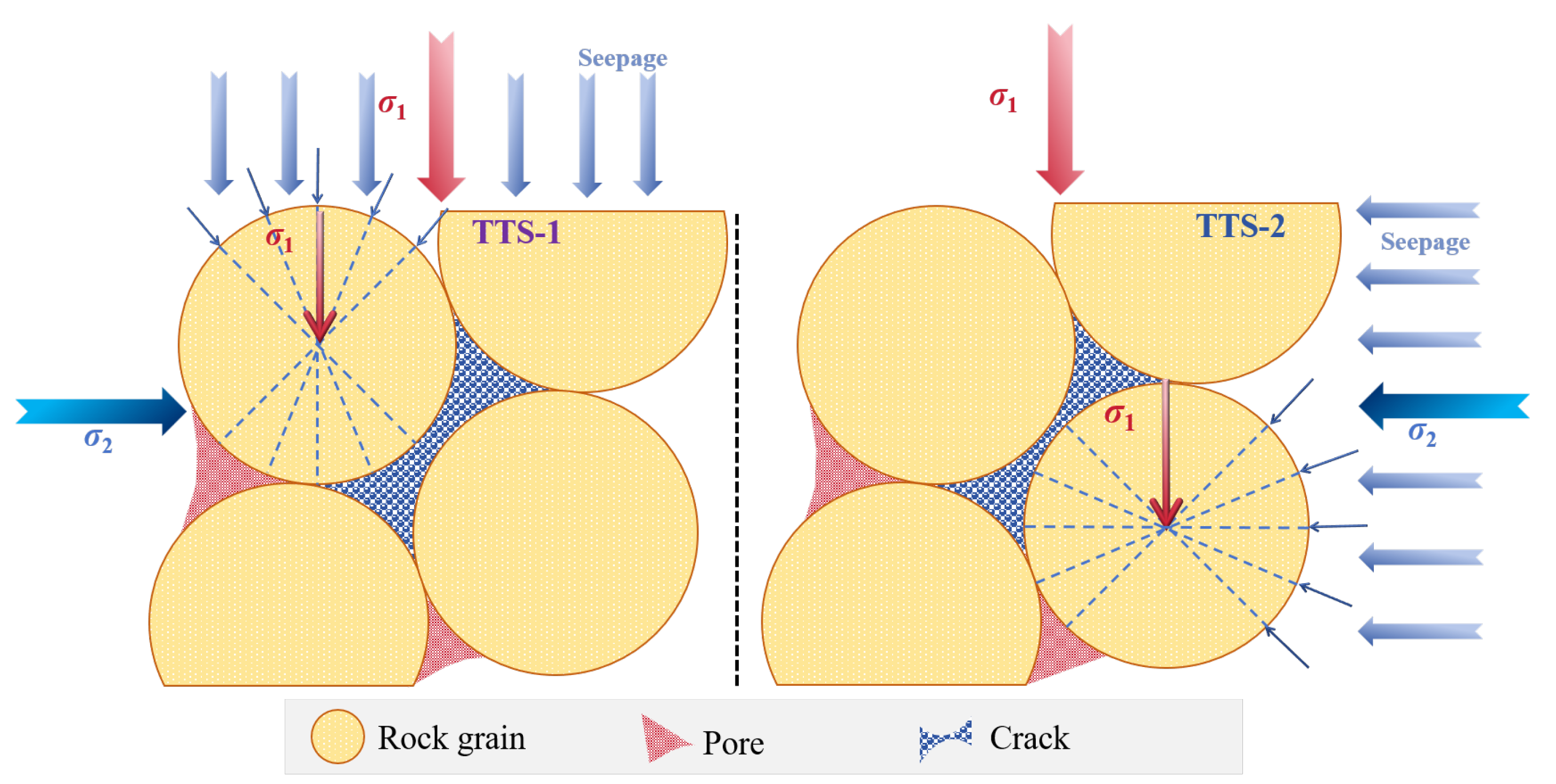

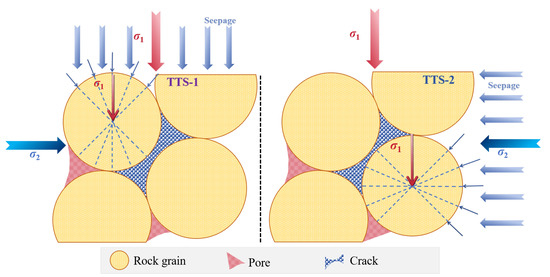

This study investigates the mechanical properties of mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions by conducting true triaxial tests. The study results reveal that the seepage direction significantly influences the characteristic stresses, deformation and failure stages, and failure characteristics of mudstone. This effect primarily stems from the relative relationship between the seepage direction, the principal stress direction, and the cracks as shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Failure mechanism diagrams for different seepage directions.

The differences in the variation patterns of characteristic stress under different seepage directions, shown in Figure 15a,b as well as Figure 16a,b, are usually because, under the loading condition of the maximum principal stress, the direction of crack propagation is closer to the direction of the maximum principal stress [44,45]. If the seepage direction is the same as the maximum principal stress direction, the fine particles in the mudstone temporarily block the seepage channels [54,55], weakening the influence of the permeation effect in a short period of time. Therefore, σci and σcd increase with an increase in permeation pressure. However, this influence disappears when the rock is about to fail; thus, strength still decreases with an increase in permeation pressure. Under the seepage condition in the direction of the intermediate principal stress, water can enter the crack through the entire crack surface, and the efficiency of reducing the effective stress is higher. Therefore, σci and σcd of the mudstone decrease with an increase in permeation pressure. In terms of volumetric dilation hysteresis effect, based on previous research inferences, under the seepage condition of the intermediate principal stress direction, since the water flow is impeded by the cracks, the softening of mudstone is relatively slower than that under the seepage condition of the maximum principal stress direction. Therefore, its dilatancy point is relatively delayed.

The study results highlight a critical insight: considering seepage in only one direction may lead to significant deviations in assessing the stability of the surrounding rock. In practical engineering applications, it is essential to consider not only the permeability of the surrounding rock but also the influence of seepage direction on its mechanical behavior.

5. Conclusions

A series of true triaxial seepage tests were conducted to comprehensively analyze the variation laws of characteristic stresses in mudstone under seepage conditions in different principal stress directions. Moreover, the failure characteristics of mudstone under different seepage conditions were systematically investigated. The key findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

1. σci, σcd, and σf show a relatively high sensitivity to increase in σp.

2. There is a volumetric dilation hysteresis effect of mudstone when the seepage direction aligns with the σ2 direction.

3. Under the same σ2, β1 increases after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, whereas β2 decreases. This suggests that the stable fracture propagation stage of mudstone is prolonged, while the unstable fracture propagation stage is shortened.

4. In the σ1–σ3 plane, under the same σ2, after TTS-1 shifts to TTS-2, the change in the included angle between the mudstone fracture surface and the σ1 direction shows a reversed trend with an increase in σp.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y.; methodology, W.Y.; software, P.Z.; validation, P.Z. and X.Z.; formal analysis, W.Y.; investigation, W.Y. and P.Z.; resources, W.Y.; data curation, P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.Y. and X.Z.; visualization, W.Y. and J.Y.; supervision, W.Y. and Y.G.; project administration, W.Y. and J.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Supported Project of the Joint Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Geology (No. U2444220), the Natural Science Foundation of Xiamen, China (No. 3502Z202372047), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52374090), the Science and Technology Research Project of Xiamen University of Technology (No. YKJ22045R), and the Engineering Innovation Center for Urban Underground Space Exploration and Evaluation, Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China (No. USEEOS-2024-01).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest exist in the publication of our manuscript, and the manuscript was approved by all authors for submission. The work described is original research that has not been published previously and not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

References

- He, M.; Wang, Q. Rock dynamics in deep mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Niu, Z.; Que, X.; Liu, C.; He, Y.; Xie, X. Study on Permeability Characteristics of Rocks with Filling Fractures Under Coupled Stress and Seepage Fields. Water 2020, 12, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W.; Liao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. A Review of Hydromechanical Coupling Tests, Theoretical and Numerical Analyses in Rock Materials. Water 2023, 15, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Xu, Q.; Ren, K.; Wei, L.; Wang, W. Critical State Analysis for Iron Ore Tailings with a Fine-Grained Interlayer: Effects of Layering Thickness and Dip Angle. Water 2024, 16, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, M.; Ibemesi, P.; Benson, P.; Bedoya-González, D.; Sauter, M. The Role of Rock Matrix Permeability in Controlling Hydraulic Fracturing in Sandstones. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 5269–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Wang, H.; Mehmood, F.; Cheng, C.; Hou, Z. An anisotropic damage-permeability model for hydraulic fracturing in hard rock. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 3661–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gan, Q.; Hurst, A.; Elsworth, D. Investigation of coupled hydro-mechanical modelling of hydraulic fracture propagation and interaction with natural fractures. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 169, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yin, G.; Xu, J.; Cao, J.; Song, Z. Permeability evolution of shale under anisotropic true triaxial stress conditions. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 165, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Duan, K.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Jiang, R.; Wang, L. Investigation of the permeability anisotropy of porous sandstone induced by complex stress conditions. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 157, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, M.; Wu, J. Influence of permeability anisotropy of seepage flow on the tunnel face stability. Undergr. Space 2023, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Huang, X.; Lei, Q. Characterizing the Permeability Anisotropy of Coral Reef Limestone Based on CT Scanning and CFD Modeling. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 11715–11737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongandembou, M.; Yu, Q. Blockiness and hydraulic conductivity of rocks with different fracture geometries. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, H.; Tang, C. Scale effect in macroscopic permeability of jointed rock mass using a coupled stress-damage-flow method. Eng. Geol. 2017, 228, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Wu, R. Full-field strain evolution and characteristic stress levels of rocks containing a single pre-existing flaw under uniaxial compression. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 3145–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhang, J.; Hu, M. Damage Evolution and Failure Mechanism of Red-Bed Rock under Drying–Wetting Cycles. Water 2023, 15, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Xie, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, D.; Peng, S.; Zhang, T. True triaxial unloading test on the mechanical behaviors of sandstone: Effects of the intermediate principal stress and structural plane. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 2025, 17, 2208–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Long, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, X. A true triaxial experiment investigation of the mechanical and deformation failure behaviors of flawed granite after exposure to high-temperature treatment. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 306, 110273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Q. Experimental study on mechanical characteristics and permeability evolution during the coupled hydromechanical failure of sandstone containing a filled fissure. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 4055–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, T.; Li, W.; Ren, Y.; Wang, G.; He, P. Experimental Study of Mechanical and Permeability Behaviors During the Failure of Sandstone Containing Two Preexisting Fissures Under Triaxial Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 3673–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Wang, Z.; Alam, M.; Xu, L.; Xu, J. Mechanical and seepage characteristics of polyvinyl alcohol fiber concrete under stress-seepage coupling. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, S. Laboratory investigations on failure, energy and permeability evolution of fissured rock-like materials under seepage pressures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 247, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Zhao, N.; Wu, K. A damage-based analytical model to evaluate seepage pressure effect on rock macro mechanical behaviors from the perspective of micro-fracture. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2025, 34, 496–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Lin, C. Fracture Propagation of Rock like Material with a Fluid-Infiltrated Pre-existing Flaw Under Uniaxial Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 875–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Crack propagation behavior in sandstone during unloading confining pressure under different seepage pressures. J. Cent. South Univ. 2023, 30, 2657–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cai, M.; Wang, J.; Ma, L. Damage stress and acoustic emission characteristics of the Beishan granite. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 2013, 64, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Luo, J. Effects of seepage pressure on the mechanical behaviors and microstructure of sandstone. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 2024, 16, 2033–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, L.; Sun, P.; Wang, S.; Li, F. Laboratory investigation of the shear failure process and strength characteristics of a rock mass containing discontinuous joints under water pressure influence. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Sheng, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, W. Time-dependent propagation and interaction behavior of adjacent cracks in rock-like material under hydro-mechanical coupling. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 122, 103618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gao, R.; Yan, C. Dynamic fragmentation and chip formation of water-soaked rock in linear cutting with a coupled moisture migration-fracture model. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 163, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, K.; Sun, J.; Deng, T.; Wang, Q. Creep behavior of carbonaceous mudstone under triaxial hydraulic coupling condition and constitutive modelling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 164, 105357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Liu, Y.; Ren, J.; Wu, R.; Zhang, Y. Laboratory test on crack development in mudstone under the action of dry-wet cycles. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yan, C.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, G. Microfracture behavior and energy evolution of heterogeneous mudstone subjected to moisture diffusion. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 150, 104918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yan, C. Investigating the influence of water on swelling deformation and mechanical behavior of mudstone considering water softening effect. Eng. Geol. 2023, 318, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lan, T.; Lai, Y.; Li, M.; Ma, Q. Softening mechanism and characteristics of mudstone after absorbing moisture. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 254, 107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, J. Experimental study of the influence of water and temperature on the mechanical behavior of mudstone and sandstone. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 2017, 76, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Yin, X.; Tang, H.; Cheng, X. Reliability analysis and geometric optimization method of cut slope in spatially variable soils with rotated anisotropy. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 158, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Teng, T.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Tan, Y. Characterization and Modeling Study on Softening and Seepage Behavior of Weakly Cemented Sandy Mudstone after Water Injection. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 7799041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Miao, X.; Chen, Z.; Mao, X. Experimental Investigation of Seepage Properties of Fractured Rocks Under Different Confining Pressures. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2013, 46, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ma, Y.; Song, S.; Tang, M.; Li, Y. Deformation behavior and damage-induced permeability evolution of sandy mudstone under triaxial stress. Nat. Hazards 2022, 113, 1729–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, W.; Wang, R.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Feng, S. Permeability of dense rock under triaxial compression. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2015, 3, 40–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Yang, S. Experimental investigation on permeability evolution law during course of deformation and failure of rock specimen. Rock Soil Mech. 2006, 27, 1703–1708. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, C.; Hou, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, X. Experimental study on seepage characteristics of deep sandstone under temperature-stress-seepage coupling conditions. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2020, 39, 1957–1974. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Loosveldt, H.; Lafhaj, Z.; Skoczylas, F. Experimental study of gas and liquid permeability of a mortar. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Haimson, B. Failure characteristics of two porous sandstones subjected to true triaxial stresses. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2016, 121, 6477–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Haimson, B.; Li, X.; Chang, C.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Ingraham, M.; Suzuki, K. ISRM Suggested Method: Determining Deformation and Failure Characteristics of Rocks Subjected to True Triaxial Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X. Influences of Mechanical Contrast on Failure Characteristics of Layered Composite Rocks Under True-Triaxial Stresses. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 5363–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Yi, Y.; Luo, X.; Liu, K.; Li, P.; Wang, S. Novel damage constitutive models and new quantitative identification method for stress thresholds of rocks under uniaxial compression. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 2658–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhong, R.; Pel, L.; Smeulders, D.; You, Z. A New Volumetric Strain-Based Method for Determining the Crack Initiation Threshold of Rocks Under Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 1329–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xie, H.; Wang, J. Anisotropic characteristics of crack initiation and crack damage thresholds for shale. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 2020, 126, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Rong, G.; Cai, M.; Zhou, C. A model for characterizing crack closure effect of rocks. Eng. Geol. 2015, 189, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. Crack evolution behavior of rocks under confining pressures and its propagation model before peak stress. J. Cent. South Univ. 2019, 26, 3045–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Kong, R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C. Experimental Study of Failure Differences in Hard Rock Under True Triaxial Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 2109–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, R.; Wu, M. True triaxial energy evolution characteristics and failure mechanism of deep rock subjected to mining-induced stress. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 2024, 176, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, X.; Yin, Z.; Chen, X. Clogging effect of fines in seepage erosion by using CFD–DEM. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 152, 105013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, G.; Jin, W.; Tang, N.; Ren, H.; Chen, X. Characteristics and quantification of fine particle loss in internally unstable sandy gravels induced by seepage flow. Eng. Geol. 2023, 321, 107150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).