A Theoretical Model for Pipe Roof Support in Shallow Buried Tunnels Considering Changes in Water Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

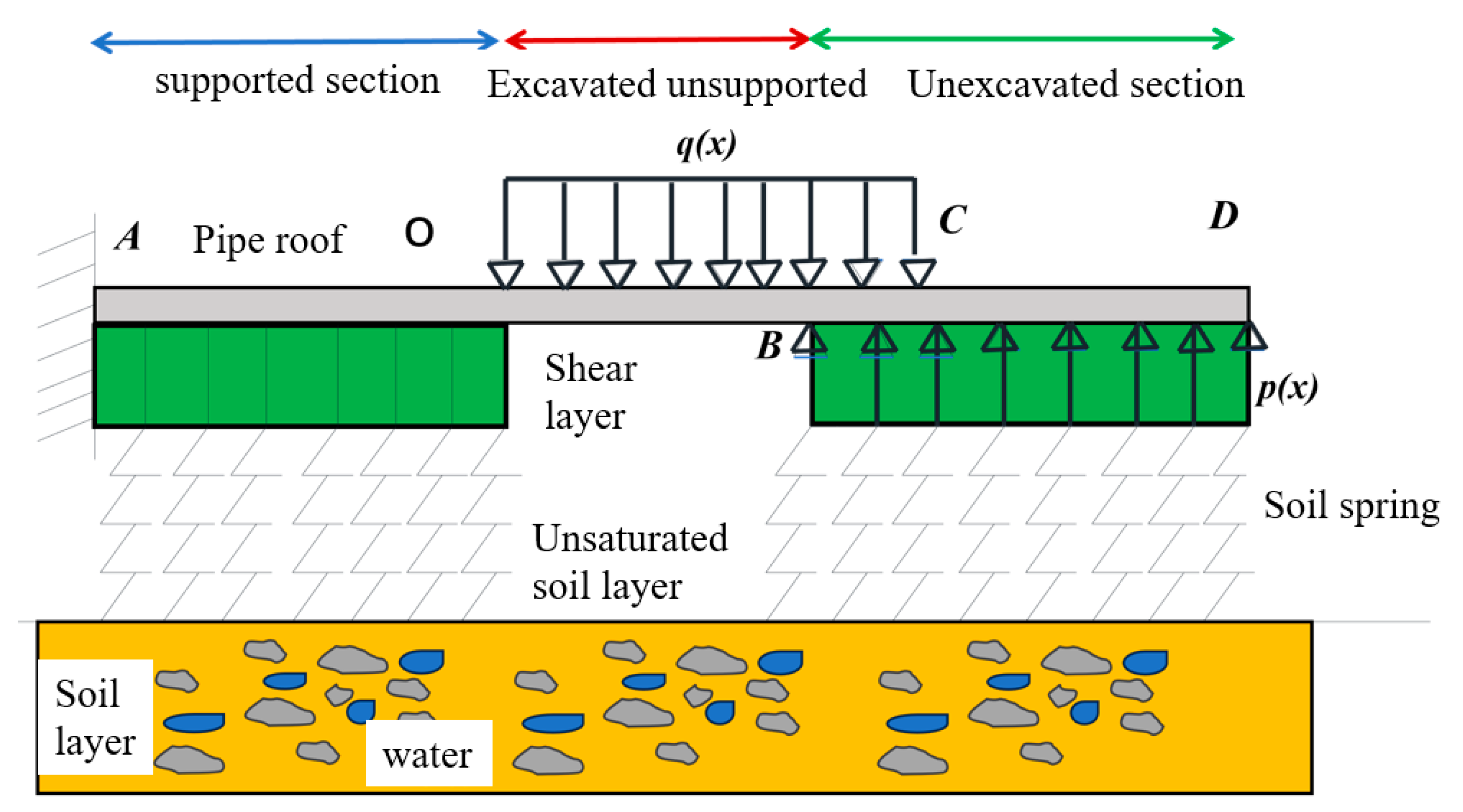

2. Model Development Model for Pipe Roof on Pasternak Foundation Considering Water Content

2.1. Influence of Water Content on the Two Parameters of Pasternak Foundation Theory

2.2. Longitudinal Mechanical Model of Pipe Roof in Unsaturated Stratum Based on Pasternak Foundation Theory

2.3. Model Solution

3. Model Verification and Parametric Analysis

3.1. Model Verification

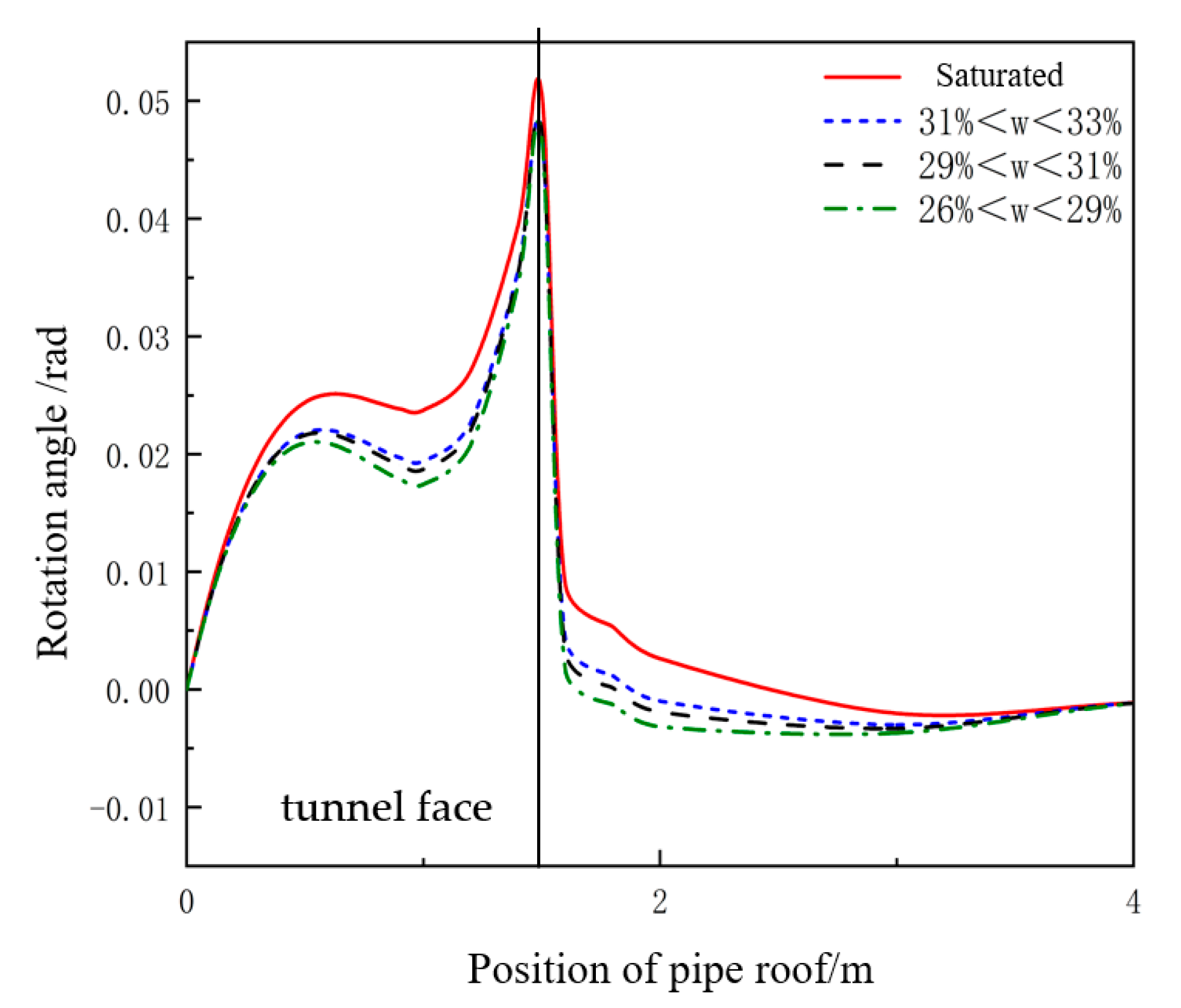

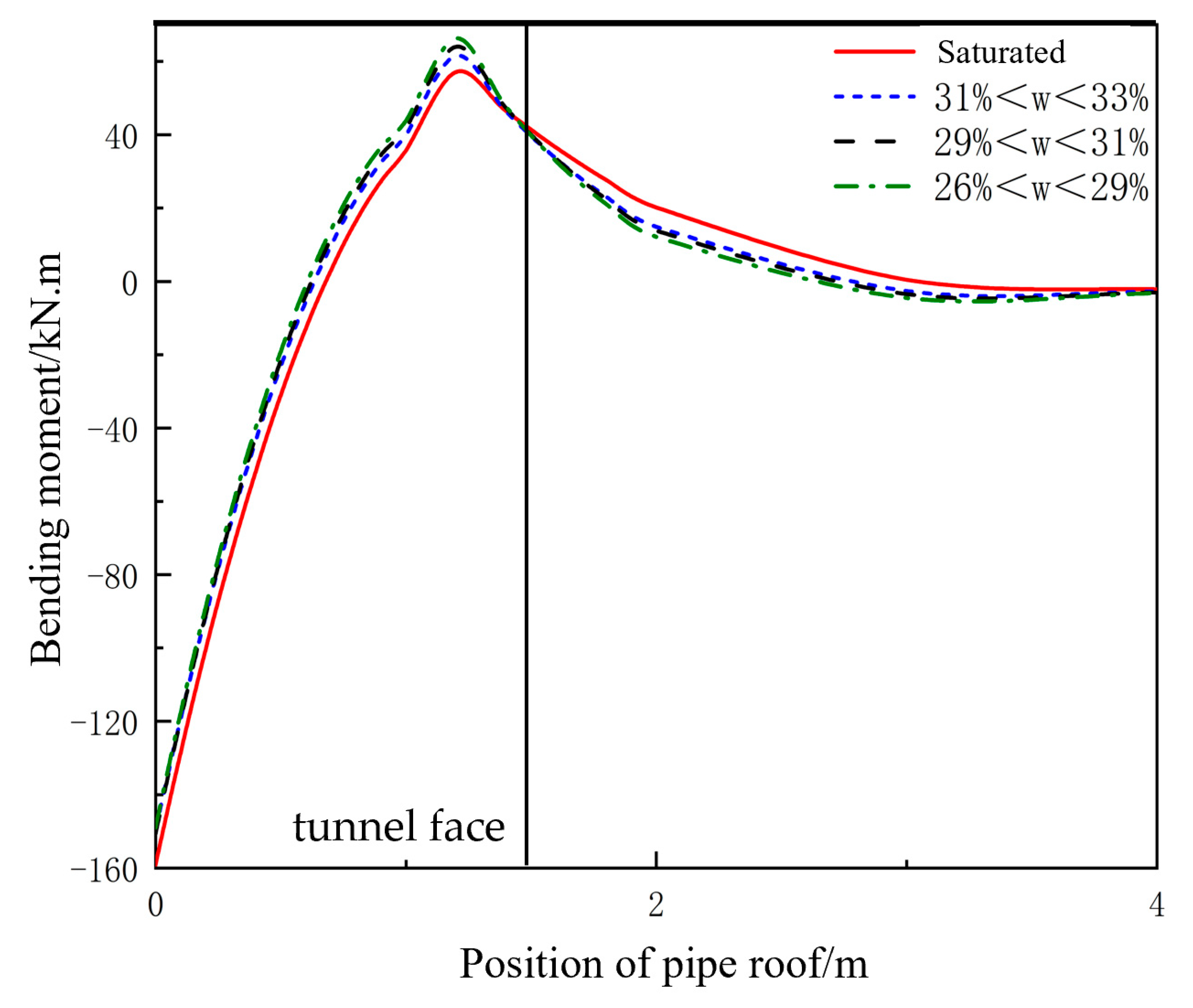

3.2. Parametric Analysis of Pipe Roof Mechanical Behavior Under Different Soil Water Contents

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Units | Meaning |

| a | m | advance length of a single-cycle excavation |

| b | m | equivalent width of the foundation shear layer |

| D | m | diameter of pipe |

| E, Esat, Eunsat | GPa | Young’s modulus and the one at saturated and unsaturated conditions, respectively |

| G, Gunsat | kN/m | shear modulus and the one at unsaturated condition |

| h | m | burial depth of the tunnel pipe roof |

| H | m | excavation Height |

| I | m4 | cross-sectional moment of inertia |

| k, kunsat | kN/m3 | soil subgrade reaction coefficient and the one at unsaturated condition |

| M | kN·m | bending moment |

| Pa | kPa | atmospheric pressure |

| q | kPa | overlying surrounding pressure on the pipe roof |

| V | kN | shear force |

| ua | kPa | pore air pressure |

| uw | kPa | pore water pressure |

| α, β | / | fitting parameters in Equation (3) |

| α1 α2 | 1/m | attenuation rate parameters in Equations (11) and (12) |

| μ | / | Poisson’s ratio |

| γ | kN/m3 | unit weight of the overlying soil on the tunnel pipe roof |

| φ | ° | internal friction angle |

| w, w0 | m | deflection of the beam and initial deflection |

| ρ3 to ρ6 | / | abbreviations used for parameter expressions |

| π1, π2, π3, π4 | / | integral constants in Equation (8) |

| ζ1, ζ2, ζ3, ζ4 | / | integral constants in Equations (9) and (10) |

References

- Wei, G.; Xu, R. Prediction of longitudinal ground deformation due to tunnel construction with shield in soft soil. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2005, 27, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Zheng, J.; Cui, L. Analysis of responses of pile groups due to tunnelling during excavation and operation periods considering rheological behavior of soft soils. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2018, 55, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Tian, X.; Zhou, G.; Li, W. Theoretical analysis of mechanical behavior of advanced pre-support of pipe-roof in tunnel. China, J. Highw. Transp. 2020, 33, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Shi, C. Study on deformation control technology of shallow and large cross-section tunnel beneath expressway in soft rock. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2018, 15, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, W.; Yi, X.; Bai, H.; Li, S.; Zhao, J. Microstructural changes of granite residual soil during humidification process. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2025, 57, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- An, R.; Kong, L.; Li, C. Strength attenuation and microstructure damage of granite residual soils under hot and rainy weather. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2020, 39, 1902–1911. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wang, Z.; Wei, C.; Yan, R. Effect of saturation on shear strength characteristics of weathered granite slope soils. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Khoshghalb, A.; Russell, A.R. Fractal-based estimation of hydraulic conductivity from soil–water characteristic curves considering hysteresis. Géotech. Lett. 2014, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ni, J.; Li, J. Stress-dependent water retention of granite residual soil and its implications for ground settlement. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 129, 103835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Kaya, M. A power law for elastic moduli of unsaturated soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2014, 140, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, C.; Chen, F.; Cai, G. Study on mechanical characteristics of pipe umbrella support in shallow buried tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 145, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Li, G.; Shi, X. Load transferring mechanism of pipe umbrella support in shallow-buried tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2014, 43, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhou, S.; Sun, Y. Stability analysis and case study of shallow tunnel using pipe roof support. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2019, 37, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yuan, J.; Li, J.; Peng, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, H. Deformation prediction of pipe roof in shallow soft portal section of tunnels considering construction feature. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2017, 36, 716–724. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Xu, Z.; Huang, L.; Lin, C.G. A pasternak foundation-based theoretical model for pipe roof support in shallow buried biased pressure tunnel. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 3148–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jia, C.; Lei, M.; He, Y.; Shi, C.; Li, A. An improved model of the pasternak foundation beam umbrella arch considering the generalized shear force. J. Cent. South Univ. 2025, 32, 1503–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chou, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. Analysis of horizontal displacement of single pile induced by lateral penetration of tunnel based on the pasternak shear layer theory. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2023, 60, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, W.T.; Vanapalli, S.K.; Puppala, A.J. Semi-empirical model for the prediction of modulus of elasticity for unsaturated soils. Can. Geotech. J. 2009, 46, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. Mechanical Mechanism of Pipe Roofs Based on the Pasternak Model with Variable Coefficient of Subgrade Reaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Wang, W.; Sun, W. Theoretical analysis of bearing mechanism of pipe sheds. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2025, 60, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Lu, Z.; Guo, L.; Zhang, L.M. Experimental study on soil-water characteristic curve for silty clay with desiccation cracks. Eng. Geol. 2017, 218, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, G.M. Rock mass pipe roof support interaction measured by chain inclinometers at the birgltunnel. In Proceedings of the Geotechnical Measurements and Modelling, Karlsruhe, Germany, 23–26 September 2003; pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Russell, A.R. Cavity expansion in unsaturated soils exhibiting hydraulic hysteresis considering three drainage conditions. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2015, 39, 1975–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Melinda, F.; Leong, E.C.; Rezaur, R.B. Stiffness of a compacted residual soil. Eng. Geol. 2011, 120, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Excavation Advance, a/(m) | Circumferential Spacing, b/(m) | Excavation Height H/(m) | Surrounding Rock Pressure q/(kPa) | Equivalent Moment of Inertia, I/(mm4) | Equivalent Elastic Modulus, E/(GPa) | Tunnel Burial Depth h/(m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2 | 0.4 | 5 | 97.5077 | 21,510,000 | 91.7 | 5.137 |

| Tunnel Burial Depth h/m | Elastic Modulus E/MPa | Pipe Diameter D/mm | Pipe Spacing b/cm | Internal Friction Angle φ/(°) | Soil Unit Weight γ/(kN/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 100 | 114 | 40 | 30 | 18.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wei, Y.; Yang, H. A Theoretical Model for Pipe Roof Support in Shallow Buried Tunnels Considering Changes in Water Content. Water 2025, 17, 3521. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243521

Chen J, He M, Wang Y, Wu J, Wei Y, Yang H. A Theoretical Model for Pipe Roof Support in Shallow Buried Tunnels Considering Changes in Water Content. Water. 2025; 17(24):3521. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243521

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jingsong, Mu He, Yan Wang, Jianbo Wu, Yujing Wei, and Hongwei Yang. 2025. "A Theoretical Model for Pipe Roof Support in Shallow Buried Tunnels Considering Changes in Water Content" Water 17, no. 24: 3521. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243521

APA StyleChen, J., He, M., Wang, Y., Wu, J., Wei, Y., & Yang, H. (2025). A Theoretical Model for Pipe Roof Support in Shallow Buried Tunnels Considering Changes in Water Content. Water, 17(24), 3521. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243521