Abstract

Localising leaks in pressurised water distribution networks (WDNs) is crucial for reducing water loss but remains challenging because of model uncertainties and limited sensor data. Nevertheless, many state-of-the-art methods rely on idealised assumptions that are perfectly known, like time-invariant demands, noise-free pressure sensors, a single, stationary leak, and a known leak-free baseline. These assumptions rarely hold in practice, creating a gap between expected performance and field reality. This article provides a comprehensive review of current leak localisation techniques based on sensor data and hydraulic or data-driven models. This study critically examines how recent studies have addressed these unrealistic assumptions. Advanced methods incorporate demand uncertainty and sensor noise into leak detection algorithms to improve robustness, estimate unknown demand variations using physics-informed machine learning, and employ Bayesian inference to locate multiple simultaneous leaks. The analysis indicates that accounting for such real-world complexities markedly improves localisation accuracy; for instance, even minor demand estimation errors or sensor noise can dramatically degrade performance if not addressed. Finally, bridging the gap between the models and reality is essential for the practical deployment of water utilities. Thus, this review recommends that future studies integrate uncertainty quantification, adaptive modelling, and enhanced sensing into leak localisation frameworks, thereby guiding the development of more resilient and field-ready leak management solutions.

1. Introduction

Water leaks in distribution networks are a crucial problem for water operators, causing a significant waste of resources (up to 30%, or even more, of the water introduced can be lost [1]) and potential health risks owing to contaminant infiltration during pressure drops. Globally, the scale of water leakage is enormous: the World Bank estimates that over 32 billion cubic metres of treated water are lost annually through leaks worldwide [2], underscoring the critical importance of effective leakage control. Therefore, minimising losses is essential for economic, environmental, and quality of service reasons. In recent decades, leak localisation in the network has become a major technical challenge, with increasingly sophisticated methods exploiting field sensors and mathematical models of the network. Modern regulatory frameworks emphasise leakage reduction and network reliability as key performance indicators for water utilities. For example, in Italy, these factors are formally measured to guide asset management plans [3], underscoring the need for leak localisation methods that can meet both operational and reliability objectives.

In general, modern approaches combine monitoring data (typically pressure and flow rates measured by distributed sensors) with a hydraulic network model. Under normal conditions, a well-calibrated model accurately reproduces the pressure values recorded in the network; however, the presence of a leak introduces discrepancies. This additional runoff caused larger-than-expected pressure drop. In model-based methods, this principle is exploited by systematically comparing the measured pressures with those simulated by the model. A significant difference indicates a hydraulic anomaly that can be attributed to a leak [4]. Localisation is performed by simulating different hypotheses of loss in the model (varying position and flow rate) and searching for the one whose response (in terms of pressures to the sensors) best approximates the real data. In practice, water companies often partition networks into District Metering Areas (DMAs) to monitor and reduce losses at the zone level (a strategy shown to be effective in lowering leakages by optimising sectorisation and pressure control [5]). However, this structural approach complements rather than replaces advanced leak localisation methods. Leak management measures can have unintended effects on water quality. For instance, Giustolisi et al. (2023) [6] showed that aggressive leakage reduction (through pressure control and DMA isolation) may increase the water residence time in parts of the network, indicating the need to balance leak reduction while maintaining acceptable water quality. Effective leak localisation does not exist in isolation; it is part of a larger trend towards smarter network monitoring. For example, La Cognata et al. (2025) [7] presented a comprehensive review of pollutant monitoring solutions in water and wastewater networks, highlighting the parallel challenges of integrating sensor data with models, a perspective that complements the present focus on leak detection by emphasising holistic network monitoring.

Various model-based approaches based on this concept have been proposed, including sensitivity matrix methods [8], optimization/calibration methods [9], and hybrid model/data techniques. In all cases, the focus was on comparing the measurements and simulations to identify the leak point.

In parallel with model-based methods, data-driven approaches have become widespread, leveraging statistical analysis and artificial intelligence applied only to sensor data without requiring an explicit network model or using only one to generate synthetic training data. Such approaches include supervised machine learning algorithms, which recognise the abnormal pressure pattern associated with leaks after training on historical normal operating data and simulated leak scenarios, and unsupervised models, which detect sudden or outlier changes in pressure and flow signals. Data-driven methods are gaining popularity owing to the increasing availability of sensors and real-time data (smart water networks) and advances in the fields of big data and deep learning [10]. They have the advantage of not requiring detailed knowledge of the network, which is useful when a hydraulic model is unavailable or unreliable. However, they often require large amounts of complete historical data for training and may be less generalisable outside the conditions observed in the training phase. In many cases, hybrid solutions are adopted by combining the strengths of the two approaches, such as generating synthetic data from a model to train leak classification algorithms or performing an initial statistical detection of anomalies in measurements and then applying a model to refine the location [11,12].

Despite the variety of proposed methods, model-based contributions remain central because of their ability to directly exploit the physical equations of flow under pressure. Recent studies indicate that, where a well-calibrated hydraulic model and adequate sensors are available, model-based methods can offer highly accurate localisation performance, which is difficult to match using promising data-driven algorithms [13]. However, these methods are often based on simplifying assumptions that facilitate their theoretical application but limit their validity in complex real-world contexts [14,15]. Some typical hypotheses are as follows: (i) known and stationary water demands, (ii) measurements without material error, (iii) the presence of only one leak at a time, and (iv) stationary losses and the possibility of having an initial reference state without losses. These “hidden” simplifications risk creating a gap between theory and operational reality because the conditions in real water networks are much more uncertain and dynamic. Consequently, excellent simulation results could degrade dramatically in the field if these assumptions are not met. Javadiha et al. (2019) [11] and Wachla et al. (2015) [16] show how intelligent model-based algorithms achieve optimal performance only by assuming a perfect model of the network, exact demands and low-noise measurements. If these conditions are not satisfied, more robust data-driven alternative methodologies must be used.

The purpose of this article is to critically review model-based leak localisation methods considering their simplifying assumptions, highlighting the progress made to bring such methods closer to real-world conditions. The following section describes the methodology adopted for the bibliographic search of the literature. Subsequently, the main simplifying hypotheses underlying standard model-based approaches are analysed in detail, discussing their implications and presenting examples of studies that have attempted to remove or mitigate them. This includes the most recent advanced approaches that have partially overcome the limitations of traditional approaches. Finally, conclusions are drawn by outlining prospects for more robust and operationally applicable leak location methods.

2. Materials and Methods

The present literature review was conducted following a systematic approach to identify the most relevant literature on the topic of water leakage localisation using modelling tools and sensor data. First, existing reviews and reference works in the field were consulted and used as a basis for mapping the state-of-the-art. These include the classic review by Puust et al. (2010) [17] on leak management methodologies in pressurised water networks and more recent contributions, such as the detailed review by Romero-Ben et al. (2023) [13], which focused on the evolution from model-based to data-driven methods, and the survey by Wan et al. (2022) [18], which was dedicated to the analysis of pressure/flow data for leak detection in smart water networks. Building on insights from these references, a comprehensive search was then performed in major scientific databases (Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) using a broad set of keywords related to leak localisation (e.g., “leak localization,” “water distribution leaks,” “model-based leak detection,” “leakage fault diagnosis,” “pressure sensors”), in order to capture both historical seminal works and the most recent advances in the field.

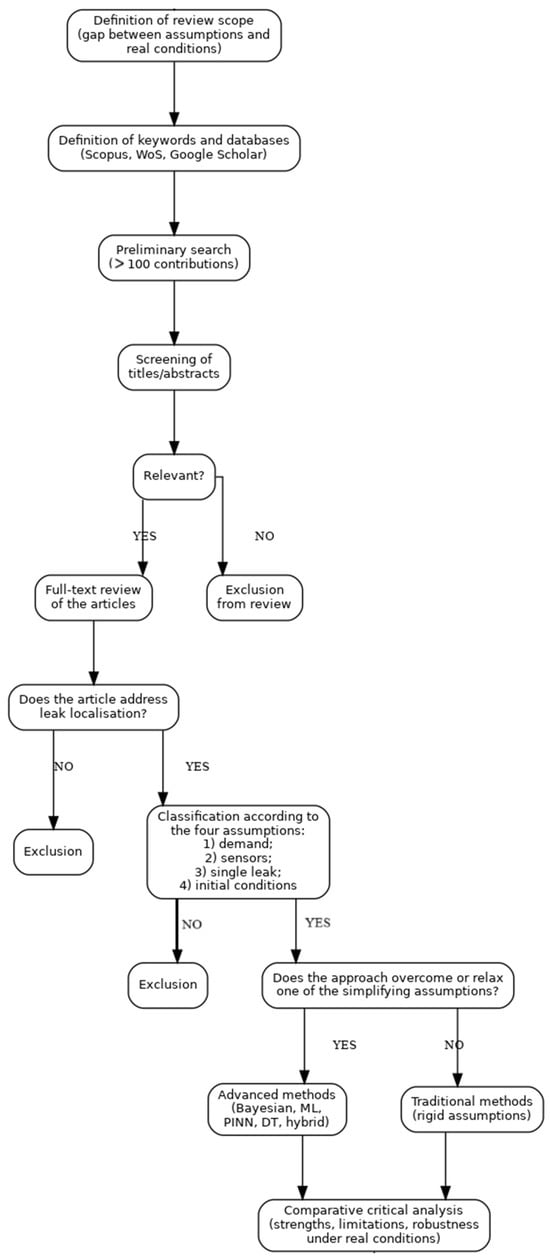

An initial screening of the search results was carried out to ensure relevance to the topic of leak localisation. Inclusion criteria required that a study explicitly addresses leak localisation (pinpointing leak positions) in water distribution networks using models or data-driven approaches informed by sensor measurements. Exclusion criteria were applied to filter out publications that were not focused on localisation (for instance, studies dealing solely with leak detection without localisation, or those unrelated to water distribution systems). As a result of this screening stage (Figure 1), a large number of records were discarded for not meeting the above criteria. In total, the database queries returned several hundred unique records; after title/abstract screening based on relevance, just over 100 studies were deemed pertinent and retained for closer examination. Each of these ~100 studies was then reviewed in full text to assess its contribution and alignment with the objectives of this review. About 60 of these were subsequently excluded upon full-text analysis (e.g., due to insufficient focus on the review’s core questions or use of methodologies outside the scope), resulting in approximately 40 key publications that were ultimately selected for in-depth analysis. Figure 1 provides a flow chart illustrating the literature screening and selection process, from the initial identification of records to the final inclusion of key studies. After finalising the selection of literature, the focus of the review was organised around four main simplifying assumptions that are commonly found in model-based leak localisation methods. These four assumption areas are: (i) known and stationary water demands, (ii) measurements without material error, (iii) the presence of only one leak at a time, and (iv) stationary losses and the possibility of having an initial reference state without losses. Each of the selected studies was classified according to which of these key assumptions it adopts. The extent to which each assumption has been addressed or mitigated by the various approaches was assessed, i.e., whether the method can still function if the assumption is violated or whether it explicitly incorporates techniques to mitigate the limitations of that assumption. For each assumption category, representative examples of traditional model-based methods that rely on the given simplifying hypothesis were identified, as well as advanced methods that have attempted to relax or remove that assumption. In particular, the review highlights how recent approaches have introduced greater realism into leak localisation algorithms: for example, by integrating demand uncertainty and sensor noise into model-based analyses, by using physics-informed machine learning to estimate or adjust unknown demand patterns, or by employing Bayesian inference to handle multiple simultaneous leaks and other uncertainties, in order to underscore the progress made in overcoming the limitations of earlier techniques.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the present critical review.

Throughout the review process, key information was extracted from each selected study regarding the validity and role of the assumptions in its methodology, the effects on localisation performance under varying non-ideal conditions (e.g., sensor noise, demand uncertainty, multiple concurrent leaks), and any strategies proposed to deal with deviations from ideal theoretical conditions. This comparative analysis enabled us to assess how “relaxable” each simplifying assumption is in practice and which innovations are most effective in bridging the gap between theoretical models and field reality. Moreover, results from relevant benchmark exercises and laboratory/field experiments documented in the literature [19] were considered to objectively compare the effectiveness of different leak localisation approaches under complex, realistic scenarios.

3. Simplifying Assumptions in Leak Location Methods

3.1. Stationary and Well-Known Water Demands

One of the most common assumptions in hydraulic models is the consideration of known and invariable water consumption patterns. Many localisation algorithms assume that the flow rates requested by users are perfectly known or derived from aggregated consumption measurements, keeping them fixed during the leak detection analysis. This hypothesis greatly simplifies the problem, as the differences between the measured and simulated pressures can only be attributed to the presence of a leak because the possibility of unexpected changes in demand causing the deviations is excluded. Different methodologies operate in conditions close to the steady state, analysing quasi-quiescent states (typically at night) in which consumption is assumed to be constant and reduced [20,21]. Zaman et al. (2020) [22], in their review of steady-state leak detection methods, point out that such approaches achieve good results by isolating the system from load fluctuations, but in fact they presuppose deterministic and known demands in each district.

Water demand is highly variable and uncertain over time, as it depends on random human behaviour and weather conditions, and often has oscillations and peaks that are difficult to predict. Even well-calibrated models can quickly diverge from measurements if the actual demand deviates from the expected value. Perez et al. (2014) [8], Adedeji et al. (2017) [23], and Hu et al. (2021) [24] showed that the effectiveness of model-based localisation drops dramatically in the presence of errors in consumption estimation, making the results unreliable. In addition, many networks do not have widespread flow metres at the nodes (smart metres); therefore, the nodal demands are estimated by calibrating the model on the main pressures and flows.

Some researchers have proposed solutions to relax the perfectly known demand hypothesis in the literature. One strategy is to integrate the process of estimating/updating demands in parallel with the location of the leak into the method. Wu et al. (2010) [25] introduced a pressure-dependent demand model in which the leak was treated as an additional “emitter”: by appropriately calibrating the emission and demand parameters, the position of the leak could be identified by simultaneously calibrating consumption and losses. Another approach is demand forecasting. Hutton and Kapelan (2015) [26] used a Bayesian model to predict the expected consumption in a district in real time and compared it with measured consumption to identify anomalous deviations attributable to leaks. This demand forecasting technique eliminates the need to know the demand in advance, as it is constantly updated with the latest data, increasing the robustness to unexpected variations. Similarly, Loureiro et al. (2016) [20] and Lee et al. (2016) [27] employed statistical analyses to distinguish natural demand fluctuations from typical loss signals without relying on predefined consumption patterns.

Giustolisi et al. (2008) [28] showed the practical unfeasibility of determining the exact position of leaks (especially with respect to background ones). They developed a pressure-driven simulation model that explicitly incorporates demand uncertainty and leak outflows into network analysis, providing a more realistic hydraulic baseline for leak detection algorithms (i.e., pressure drops owing to leaks are simulated under varying demand conditions).

The related strand explicitly incorporates uncertainty into the decision-making process using Bayesian and probabilistic approaches to model demands as random variables instead of fixed values, propagating uncertainty in the hydraulic model. Soldevila et al. (2016) [12] proposed a model-based Bayesian method in which the uncertainty of demands (and measures) is represented by probability distributions. The leak location is achieved by step-by-step updating of the credibility of each possible fault location as new pressure measurements arrive [29]. Thus, the algorithm considers the possibility that a simulated/measured pressure discrepancy is due not only to a leak but also to an error in demand, thereby increasing the reliability of the detection. Another interesting technique is the Error-Domain Falsification (EDF) technique proposed by Goulet et al. (2013) [30], and subsequently applied to water networks by Moser et al. (2018) [31]. This approach generates multiple model instances with different demand realisations from their uncertainty range and then compares the actual measurements with the outputs of each model. Models that are incompatible with measurements are progressively discarded (falsified), thereby narrowing the range of possible loss scenarios. Essentially, the EDF allows for loss localisation by exclusion, without requiring a single deterministic demand model, but by exploring an uncertainty space.

Despite this progress, its application remains a significant challenge. As observed by Alves et al. (2023) [1], uncertainty in nodal demands is an important source of error that can interfere with the performance of the localisation method. The current trend is to combine information from real-time measurements (e.g., use of AMI/AMR data, Automatic Metre Reading, if available) to constantly recalibrate or adapt the demand model during the operation of the leak detection system [32]. In the absence of this, some operators adopt the expedient of focusing on periods of near-zero demand (e.g., late at night) to reduce uncertainty; if abnormally high residual consumption is recorded at that time, it is likely that there is an ongoing leak (analysis of minimum nighttime flow rates). However, this empirical approach identifies the presence of leaks but not their location and does not help locate small leaks in the presence of variable background consumption. Table 1 summarises representative studies addressing the demand-related assumption, including their approaches and main contributions.

Table 1.

Summary of studies addressing the assumption of perfectly known or constant water demand in leakage localisation methods.

3.2. Ideal Sensors and Error-Free Measurements

The second hypothesis frequently adopted in academic work is to obtain perfect data from sensors, that is, pressure or flow measurements without noise or with negligible errors. Many simulation studies generate “synthetic” data assuming ideal sensors or add only modest Gaussian noise to the simulated values such that the model-measurement comparison is not complicated by stochastic perturbations. In some cases, it is implicitly assumed that the sensors have been calibrated accurately and that there are no drifts, gross errors, or failures in the measuring instruments. This assumption simplifies localisation because the pressure differences observed are attributable almost exclusively to real hydraulic effects (losses or variations in demand) without false signals due to instrumental errors. In sensitivity matrix methods or deterministic methods based on matrix inversion [33,34], linear or linearised equations that link pressure changes and losses work best if each data point is reliable.

However, in real applications, all measurements contain noise and possible systematic errors. Pressure sensors have typical tolerances in the range of ±0.1 m (for high-quality devices) up to several metres of water columns for cheaper or poorly calibrated sensors. In addition, spurious readings may occur because of electrical noise, interference, and data transmission problems. Even an instrumental error of a few metres can distort the analysis. Considering that the pressure drop caused by a small leak is often on the order of a few metres in a localised area, comparable noise can confuse localisation modelling [35].

The scientific community has addressed this problem by introducing techniques that make these methods more robust to noise. One solution is to apply filtering and signal preprocessing, for example, using low-pass filters or moving averages to eliminate high-frequency transients and white noise, or using advanced denoising techniques (wavelets and Kalman filters) to extract the “clean” leaky signal from a noisy background. Mashford et al. (2012) [36] and Mounce et al. (2011) [37] employed neural networks and fuzzy systems trained with noise-affected data, thus endowing them with the ability to generalize and ignore unsystematic fluctuations. In the model-based field, Soldevila et al. (2016) [12] and Kapelan et al. (2003) [38] integrated an explicit model of measurement error into their algorithms. Assuming that the error was Gaussian with a certain known standard deviation, they calculated the probability that a certain observed discrepancy was due to noise rather than real loss, thus avoiding false alarms. Levinas et al. (2021) [35] explored the use of high-resolution sensors combined with signal correlation techniques, demonstrating that by increasing the granularity of the data, it is possible to identify characteristic patterns of losses even in the presence of noise. With 1 Hz data, it is possible to notice small time-correlated pressure drops on nearby sensors, distinguishing them from random noise.

An alternative approach for dealing with imperfect measures is to incorporate a margin of tolerance into the model-data comparison. Instead of searching for an exact match, some methods have defined acceptable bands. In this case, the difference between the measured and simulated pressures must exceed a certain threshold to be considered indicative of leakage. Steffelbauer et al. (2022) [39] in their study on pressure-leak duality propose a theoretical framework for quantifying the smallest detectable pressure change attributable to a leak given the overall uncertainty of the system. In this way, they establish the minimum leak size distinguishable from noise (Leak Detectability Limit) and provide confidence in the localization results. This helps quantify the reliability of the position estimate. The method not only provides a candidate point but also a degree of confidence related to the measured signal-to-noise ratio.

Despite these improvements, many studies have tested their algorithms with near-ideal data, whereas field implementation often highlights the need for additional calibration and fault detection algorithms for the sensors themselves (to distinguish a failed sensor from an actual leak signal). In the future, increasing the quality and reliability of sensors (e.g., fibre-optic pressure sensors, immune to electromagnetic disturbances) and integrating redundant data (multi-sensor fusion) will help reduce the impact of this assumption. As pointed out by Romero-Ben et al. (2023) [13], more realistic tests of methods should always include the injection of noise and variability into synthetic data to verify their robustness under conditions similar to the operational conditions. The work analysed shows that the best model-based methods are often those that explicitly consider errors and uncertainties in measurements during the design phase rather than relying on perfect data. Table 2 provides a summary of studies addressing the assumption of perfect sensor data, along with the strategies proposed to handle measurement noise in leak localization.

Table 2.

Summary of studies addressing the assumption of perfect sensor data and strategies for handling measurement noise in leak localisation methods.

3.3. Single Leak Assumption (One Failure at a Time)

Most traditional methods assume that there is at most one significant loss in the network during the analysis period. This single-fault hypothesis is rooted in many algorithms because it simplifies both the comparison of pressure patterns and the possible simulation phase. In the literature, many studies have formulated the localisation problem as a search for a leaking node/path by finding the one that minimises the error between the simulated and measured pressures [17,34,40,41]. This is evident in sensitivity methods, where the derivative matrix ∂p/∂q (change in pressure in a sensor per unit of leakage at a given node) is used, which is properly defined for only one leak at a time. Similarly, inversion methods solve a system of equations in which the number of unknowns (extent of loss and position) is limited to one. Data-driven methods often train binary (present/no loss) or multiclass (loss location) classification models by assuming that a single loss event must be identified [42].

Water networks can simultaneously suffer multiple leaks. In large systems, it is common for widespread leaks (small leaks on joints, illegal branches) to coexist with more than one major failure in the same time horizon, especially after critical events (e.g., winter frosts that cause serial breaks). Even outside the leak-detection context, studies on network mechanical vulnerability have shown that multiple simultaneous pipe failures can severely disrupt services [43], highlighting why assuming a single leak can be an oversimplification in practice and motivating methods capable of handling multi-leak scenarios. Therefore, the hypothesis of a single leak is not guaranteed in practice; indeed, large utilities often record dozens of concomitant leaks in the network. Romero-Ben et al. (2023) [13] similarly noted that most known methods still assume a single leak—an unrealistic oversimplification—and found that only a minority explicitly address multiple simultaneous leaks. They identify the multi-leak scenario as an open challenge that must be overcome to move leak localisation techniques from academic studies to real-world practice.

From a technical perspective, the difficulty in detecting multiple leaks lies in the fact that the hydraulic effects overlap nonlinearly. The pressure drop measured at a point is a combination of the effects of all leaks in the system. An algorithm calibrated to isolate a single leak signal may be misled by multiple factors. However, some researchers have proposed approaches that are suitable for identifying multiple leaks simultaneously. Pudar and Liggett (1992) [33] formulated the inverse problem by admitting the presence of multiple losses and attempted to solve for multiple unknowns by optimisation. Although limited by huge solution gaps and the non-uniqueness of the results, their study demonstrated the feasibility of considering multiple failure scenarios by solving cases with two leaks in the test network. In recent years, more effective methods have emerged owing to increased computational power and new intelligent algorithms. Wang et al. (2022) [44] presented a multi-stage methodology for the detection and isolation of multiple leaks in districts, combining clustering analyses on pressure residues and a multipurpose genetic algorithm to simultaneously estimate the locations of multiple leaks. Li et al. (2022) [10] proposed a hybrid approach in which hydraulic simulations and machine learning collaborate to quickly identify multiple leaks: in practice, they generate a simulated dataset with combinations of two leaks and train a learning model to recognize the pressure patterns associated with each combination, achieving good results in locating up to two leaks simultaneously in a medium-sized network.

Another strand involves iteration and readjustment: the most dominant leak is identified, it is “removed” from the system (e.g., by adapting the model as if it were repaired or calibrating local demand to absorb its effect), and then the algorithm is applied again to the remaining residuals to look for a second leak. This iterative technique of progressive isolation was explored by Casillas et al. (2014) [45] and Seyoum et al. (2017) [46]. Casillas et al. (2014) [45] introduced the Angle Method, which calculates the angles between measured residual vectors and characteristic loss vectors: if a first leak is identified (minimum angle), its contribution is subtracted and the angles are recalculated to identify a second fault. A similar method was implemented by Vrachimis et al. (2022) [19] as part of the BattLeDIM contest: Some of the participating methods divided the network into zones and applied search algorithms to find multiple leaks in one zone at a time, taking advantage of the fact that sensors close to a leak react more.

The multi-leak problem can quickly become intractable as the number of possible losses increases. With N candidate nodes, choosing k losses implies exploring combinations of N on k that grow exponentially. Therefore, many practical methods limit k to 2 or 3 at most or restrict the search to certain areas through additional information (e.g., field signals or sensor clustering that suggests groups of suspicious nodes). Romero et al. (2022) [47] presented a clustering learning approach in which the network is clustered and the algorithm indicates which cluster is most likely to contain a loss; This helps to locate even more leaks because if anomalous residues appear in two different areas, the method can trigger reports in distinct clusters in parallel.

Despite some initial successes, the location of multiple leaks remains problematic. Methods designed for multiple leaks are often less accurate and reliable in terms of estimating leak flow rates and have a higher incidence of false positives (attributing two modelling when only one causes all the effects). In addition, there is the problem of discriminating between true and false losses: an imperfect model or noise could make the algorithm believe that it has two losses (explaining the discrepancies with two distinct causes) when there is perhaps only one leak and a modelling error elsewhere. Table 3 summarizes key studies that address the single-leak assumption and propose methods for multiple-leak localization.

Table 3.

Summary of studies addressing the single-leak assumption and methods for multiple-leak localization.

3.4. Stationary Losses and Known Initial Conditions (Temporal Aspects)

The last category of assumptions concerns the temporal dynamics of losses. It is often assumed that losses appear as point events and then remain constant throughout the analysis period. In other words, once breakage occurs, the leak rate is assumed constant (until repair), and cases of leaks that progressively worsen over time are not considered. In addition, many methods assume that data are available in at least one lossless period (baseline) to calibrate the model or define a reference threshold. Both hypotheses are related to time management in leak detection analysis.

This assumption of a constant leak rate throughout the analysis effectively treats the leak flow as pressure-independent, whereas in reality, leaks follow a pressure-dependent behaviour (often described in the Fixed and Variable Area Discharge (FAVAD) model [48]). Higher pressure in the pipe causes a greater leakage flow. Consequently, lowering pressure via pressure-regulation valves can significantly reduce leak rates. However, active pressure control can also mask leaks from detection in pressure readings, since the regulator will maintain downstream pressure by allowing more flow to compensate for the leak. In such cases, a leak primarily manifests as an increased flow through the valve rather than a local pressure drop, meaning traditional extended-period simulation (EPS) models with coarse time steps may not capture the leak’s effect. More dynamic analysis or high-frequency monitoring is required to observe subtle pressure transients or flow anomalies indicative of leakage. Leak localisation in networks with aggressive pressure management or significant system inertia may need to rely on flow tracking and transient pressure analysis, as standard steady-state or EPS-based methods could render manometric readings less meaningful in those scenarios.

Losses can exhibit varying temporal behaviours. A sudden burst (sudden rupture of a pipe) introduces an almost instantaneous increase in the dispersed flow rate; however, other losses are incipient and progressive [49]. A crack that gradually widens increases the dispersed flow over time. Many algorithms based on steady-state comparisons (before/after loss) struggle to detect slow and increasing leaks because anomalous signals are confused with natural daily variability. In extreme scenarios, a small leak might start and increase slowly without ever causing a noticeable “jump” in the data at any given time, thus escaping change detectors (if calibrated to detect sudden changes).

In the literature, most studies focus on losses modelled as step changes: at a certain time t0, the loss appears and then remains constant [50]. This is also due to the fact that many methods work in quasi-steady state, analysing pre- and post-loss states separately. For a localisation method, a slowly increasing leak can be nearly invisible until it reaches a significant threshold value. Some works such as Misiunas et al. (2006) [51] have addressed continuous network failure monitoring by trying to intercept warning signals of failures (e.g., small pressure transients or increasing noise indicating incipient breaks), but integrating additional techniques and sensors (acoustic or vibrational) in addition to hydraulic data alone.

The second part of the temporal assumption concerns the availability of an initial moment without losses, which is often essential for calibrating the model. Many studies assume that they know the “healthy” state of the network [52]. This allows the residues to be zero, as the model is calibrated to that condition, and any subsequent deviation is attributed to leaks. However, what if there was already a hidden leak at the time of the initial calibration? The risk is to absorb it into the model (through the calibration of the questions or characteristic curves of the pipes) and never detect it. For example, if a network has chronic background leaks, a model calibrated to slightly higher flow rates will interpret them as normal consumption, and a leak detection algorithm will only be able to detect additional leaks above the bottom. This implies that many methods do not detect pre-existing leaks, but only new leaks, compared to a baseline considered leak-free.

Some approaches have attempted to overcome this constraint. One is the use of change detection methods applied to time series of measurements. The CUSUM sequential test (CUmulative SUM) employed by Eliades and Polycarpou (2012) [53] accumulates the differences between measures and expected values and checks whether there is a persistent drift trend that exceeds a statistical threshold, indicating the onset of a loss. The advantage is that you do not need to know the absolute level “without loss”; you just need to detect a significant change in behaviour over time. This can also allow you to spot leaks that start small and grow. Wu et al. (2016) [54] applied clustering algorithms to temporal patterns of flow in districts to discover gradual deviations, demonstrating the possibility of detecting incipient leaks without a perfectly known reference but exploiting past historical data for comparison. In addition, some modern data-driven models use machine learning not only to locate but also to estimate the time of initiation and evolution of the loss. For instance, Dong et al. (2024) [55] integrated LSTM with pressure-sensitive embedding to partition networks and detect leak zones, whereas Peng et al. (2025) [56] employed LSTM-FCN models on high-frequency pressure data to distinguish leakage breaks with high accuracy. A bottom-up leakage estimation method by Mazzolani et al. (2017) [57] uses only the inlet flow time series to quantify background losses and track their increase over time, enabling the detection of gradually worsening leaks even when no truly “leak-free” baseline period is available.

Despite these developments, in operational contexts, it is still preferable to ensure that grid conditions are as loss-free as possible. In practical activities, utilities often carry out model calibration campaigns after checking for known leaks or periodically introducing reset moments. This is because a localisation method is typically calibrated to a model that, by definition, represents the “normal” network. As Romero-Ben et al. (2023) [13] pointed out that assuming the availability of an initial leak-free period for model calibration is an intrinsic limitation. If the system never achieves a truly lossless state, then any baseline dataset will inevitably contain some level of undetected leakage.

There are few examples in the literature of methods capable of identifying existing leaks without external intervention. A notable case is the concept of leakage trending: by monitoring the long-term trend of minimum nighttime flow rates in a district, the rate of background leakage can be estimated, and a gradual increase over time can be identified, a sign of worsening losses. It is not a real “localization” (it does not indicate where the leaks are), but it is useful for detecting chronic leaks even without ever having had a zero moment. This approach has been institutionalised in some contexts through the Infrastructure Leakage Index [58], but it is more part of the management of losses at the macroscopic level than of the punctual location, which is the subject of this article. Table 4 summarizes studies addressing these temporal assumptions in leak detection and localization, including how they deal with leak evolution over time and the need for a known baseline.

Table 4.

Summary of studies addressing temporal assumptions in leak detection and localization.

Neglecting these simplifying assumptions can cause leak localisation performance to deteriorate severely under real-world conditions. In fact, model-based algorithms often achieve their best results only under idealised circumstances, using a perfectly calibrated model with exact demands and noise-free sensor data. Even minor deviations from these assumptions, such as small demand estimation errors or measurement noise, can produce pressure residuals that mimic leak signatures, leading to false alarms or missed detections. As a result, methods that do not explicitly account for demand uncertainty, sensor noise or other uncertainties tend to lose reliability when applied in practice. Furthermore, commonly adopted simplifications like assuming a single isolated leak or having a leak-free baseline rarely hold in operational networks.

3.5. Advanced Approaches Beyond Traditional Standards

In light of the critical issues with traditional leak localisation methods, recent research has shifted towards advanced approaches that partially overcome standard simplifying assumptions, making leak detection and localisation more robust for real-world conditions. A promising direction is the synergistic combination of model-based and data-driven techniques to exploit their advantages. Romero-Ben et al. (2023) [13] propose a hybrid methodology that applies a model-based approach in well-modelled areas of the network and a data-driven approach in others lacking a reliable model. In their L-Town case study, they used the model-based method in two districts where an accurate hydraulic model and pressure sensors were available, and a data-driven algorithm (graph-based interpolation of pressures) in a third district without a calibrated model [59]. This adaptive strategy demonstrated that each approach, when used where most appropriate, can complement the other and effectively pinpoint leaks that would be difficult to detect using either method alone. Similarly, Daniel et al. (2022) [60] presented a sequential detection-and-localisation approach: a real-time data-driven module first detects the onset of a leak (by statistical analysis of pressure residuals) and identifies the “most affected” sensor; then, a hydraulic model is triggered to localise the leak in the vicinity of that sensor. This two-stage approach allows rapid detection of incipient leaks while narrowing the search modelling model-based localisation, addressing both temporal (quick detection) and spatial (accurate pinpointing) aspects. In general, such hybrid solutions offer flexibility: where the model is unreliable, data-driven analytics fill the gap; where data are sparse (few sensors or scarce historical data), physical modelling takes over. Indeed, studies such as Javadiha et al. (2019) [11] and Sun et al. (2020) [15] show that even deep learning algorithms can benefit from model-generated inputs, for instance, enriching training sets with simulated leak scenarios under varied conditions. The result is model-informed data-driven localisation systems capable of operating in less-than-ideal situations (incomplete models, noisy, or limited data), an approach that is attracting considerable interest for practical applications.

In addition to hybrid combinations, there is a trend towards applying advanced AI techniques directly to the leak localisation problem in ways that overcome traditional limitations. A digital twin framework integrates physical modelling and real-time data assimilation to address several core challenges. By continuously calibrating against updated sensor inputs, a digital twin can dynamically adjust to changes in demand, use sensor redundancy or filtering to mitigate noise, and simulate diverse leakage scenarios, including evolving or multiple leaks within the network. As described by Ciliberti et al. (2023) [61], a digital twin is conceptually structured to compare model-simulated values against real-time field data, detect anomalies, and refine the system state through iterative feedback loops. A well-implemented digital twin serves as both a decision support system and a leakage management tool. It identifies deviations from expected behaviour and highlights areas of potential concern, thereby enabling proactive leak localization and minimization under real-world uncertainty. Rajabi et al. (2023) [62] introduced a conditional deep convolutional generative adversarial network (CDCGAN) for leak detection and localization. The key idea is to artificially generate numerous pressure scenarios with and without leaks at various positions, training the network to distinguish between them while conditioning its output on the leak location. Once trained, this CGAN-based model can analyse real sensor data and directly output the probability of a leak at each network node, effectively learning to filter out noise and demand variability (which are incorporated into the training data) to detect the subtle “signature” of a leak. This purely data-driven approach was designed for robustness to uncertainties. However, it requires a large volume of simulated scenarios for training, often generated by a hydraulic model, which circles back to the importance of having at least an approximate system model or ample labelled data. Another cutting-edge example is the use of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). Daniel and Cominola (2023) [63] presented a framework in which a neural network is trained not only on data but also with a penalty for violating physical laws (for example, Bernoulli’s equation and mass continuity) within the model domain. Their PINN effectively embeds hydraulic physics into the learning process: it estimates unknown demand anomalies hidden in the pressure data and simultaneously monitors a residual (the discrepancy between observed and learned pressures). A change detection test (CUSUM) was applied to this residual to detect flag leaks. This innovative method aims to lessen the dependence on a perfectly calibrated model by incorporating first-principles knowledge directly into the algorithm’s structure. Initial results have shown a notable ability to identify leaks more reliably, reducing false alarms, and improving detection time. Nevertheless, the authors reported some limitations, such as the complexity of hyperparameter tuning and the need for pre-training the PINN on periods without leaks to establish a baseline. To clarify how each of these emerging techniques mitigates one or more of the previous assumptions, Table 5 summarises the advanced approaches and the specific simplifying assumption(s) that they help to overcome.

Table 5.

Mapping of advanced leak localisation approaches to the simplifying assumptions they address.

A distinguishing feature of these advanced approaches is their focus on practical implementations. While traditional research often emphasises only localisation accuracy under idealised assumptions, newer studies evaluate real-world requirements and trade-offs: How many sensors are needed? How much computing power is required for real-time analysis? How generalisable is this method to other networks? How should the uncertainty of the result be communicated to the operators? Romero-Ben et al. (2023) [13] devote considerable discussion to the practical applicability of various methods, highlighting advantages and limitations from a utility perspective. A key insight is that pure model-based methods, for all of their high fidelity, require highly calibrated network models and very accurate field measurements—conditions that rarely hold for an entire water network. In practice, constructing and maintaining a truly accurate hydraulic model is challenging owing to many factors (ageing infrastructure with uncertain parameters, incomplete network documentation, temporal changes in pipe conditions, and unknown real-time demand patterns), and extensive sensor instrumentation is often infeasible owing to cost and operational complexity [64,65]. Thus, model-based approaches tend to perform well only in a few portions of a system that are well-instrumented and well-modelled [66,67,68]. However, purely data-driven methods typically require large numbers of sensors and substantial historical data for training, which can be prohibitively expensive in large networks with hundreds of nodes. This has led to a conscious effort to relax the strong assumptions of new research. Instead of assuming a “perfect model and abundant sensors”, advanced approaches seek to operate with “imperfect models and sparse sensors”, leveraging more sophisticated computations to compensate. For instance, information fusion techniques are being explored to combine pressure and flow readings with other data sources—even qualitative indicators such as acoustic leak noise or customer complaints—to enrich the diagnostic information available from limited instrumentation. Vrachimis et al. (2021) [69] presented a modelling method that localises leaks despite partially calibrated models, by systematically identifying regions of the network that cannot explain the observed measurements (thus invalidating those regions as leak candidates) and narrowing down the possible leak location is an alternative way to cope with modelling uncertainty: instead of precisely predicting where the leak is, the method predicts where it cannot be, given what the model can and cannot reproduce. Such approaches mitigate the need for a perfectly tuned model and can reduce false search areas, even with modelling errors.

The importance of benchmarking and competition should also be underscored in driving these advanced methods forward. International events such as the Battle of the Leakage Detection and Isolation Methods (BattLeDIM) [19,70] have provided researchers with a common platform to test and compare their algorithms on shared, realistic datasets. In these competitions, a virtual but highly realistic water network (e.g., the “L-Town” network, based on a real city’s network) is used as a benchmark, with multiple leak scenarios under variable demand and noise conditions. Researchers have applied a wide range of techniques side by side, from traditional engineering heuristics and simple statistical thresholds to complex machine-learning models and detailed hydraulic model-based algorithms. The 2020 BattLeDIM involved 18 teams from academia and industry, all analysing the same SCADA-like pressure and flow modelling for leak events. The outcomes revealed valuable insights: no single approach dominated all aspects, and the methods often had complementary strengths. The best performance was achieved by teams that combined multiple techniques. In fact, the top finalists typically used ensemble strategies fusing physical modelling with machine learning to compensate for each method’s individual limitations. The detailed results showed that purely model-based methods were very reliable in detecting almost all leaks (few missed detections), but their pinpointing of the leak’s exact location could be ambiguous or less precise if the hydraulic model was not perfect or if sensor coverage was sparse, sometimes yielding a broad zone as the suspected area. Conversely, data-driven methods (including statistical change detection and learned models) often reacted quickly and were adept at recognising known leak patterns, but they occasionally misidentified the location or raised false alarms when a leak’s characteristics differed from those seen in the training data. Overall, the competition confirmed that hybrid or multi-model approaches tend to outperform any single-method strategy on complex, realistic problems. Another important outcome of these benchmarks is the creation of common datasets and evaluation standards [71]. An integrated leakage control platform described by Mazzolani et al. (2016) [72] optimises the placement of pressure sensors and prioritises likely leak locations, demonstrating how strategic monitoring design and model-based analysis together can significantly improve leak localisation outcomes in a real network.

Crucially, the latest research stresses the need to align methodological assumptions with real operational conditions. Water utilities operate under budget constraints, with ageing infrastructure and limited sensor deployments, and their staff may not be specialised in data science or hydraulic modelling. Thus, for an advanced leak localisation technique to be adopted in practice, it must be robust, relatively easy to integrate, and reliable under nonideal conditions. Improving the network’s isolation capability and resilience goes hand in hand with leak localisation. A recent study [73] used complex network theory to analyse and enhance isolation valve layouts, ensuring that when leaks are detected, the network can be promptly segmented and service disruptions minimised. For instance, many academic works have assumed that, at most, a single leak occurs at one time. However, in real networks, multiple concurrent leaks or other concurrent anomalies are common. Methods tuned only for isolated single-leak scenarios can fail or yield confusing results when confronted with multiple-leak situations, leading to missed detections or false positives. Practical implementation requires algorithms that can handle multiple simultaneous leaks and adapt to changing network states. Moreover, the use of real data (and plenty of it) is essential both in developing and calibrating the models. Uncertainties in boundary conditions (e.g., demand fluctuations, valve operations) and measurement noise must be explicitly accounted for, either through robust statistical thresholds or by training algorithms on data augmented with these uncertainties. Studies have shown that including such uncertainty modelling can significantly improve the robustness of leak detectors in the field. The consensus in the recent literature is that we must bridge the gap between theoretical research and field practice by designing with real-world constraints in mind. As Romero-Ben et al. (2023) [13] put it in their review, it is necessary to “avoid the classic assumptions of academic works and instead consider real constraints to ensure successful implementations”. Table 6 summarizes a range of recent methods along with their key features.

Table 6.

Summary of Studies Addressing Advanced Approaches for Leak Detection and Localization.

3.6. Interplay Among Assumptions

In real-world scenarios, the simplifying assumptions discussed in the previous sections seldom occur in isolation. Instead, they interact in ways that significantly complicate leak localisation. A first key interaction arises between demand uncertainty and sensor noise. Both phenomena produce deviations between measured and simulated pressures, making it difficult to discern whether the source of an anomaly is a real leak or an artefact of uncertain operating conditions. Several studies have shown that even small errors in demand estimation can generate pressure residuals comparable to those produced by leaks [8,23,24], while probabilistic frameworks explicitly highlight that demand uncertainty and measurement noise are often indistinguishable in the residual space [12]. At the same time, sensor noise can mimic leak signatures, creating false positives [35,38]. Recent studies further emphasise that distinguishing the effects of noisy sensors from unexpected consumption variations remains a major challenge in operational applications [13].

A second important interplay concerns multiple leaks and temporal evolution. When more than one leak occurs simultaneously, their hydraulic effects overlap nonlinearly, producing composite pressure anomalies that do not correspond to the characteristic pattern of any single leak. Early works already demonstrated the non-uniqueness of multileak inverse problems [33], while more recent multi-leak methodologies confirm that overlapping effects can obscure the individual contribution of each leak [10,44]. Iterative localisation strategies repeatedly show that a dominant leak can partially mask a second one, delaying or preventing its detection [45,46]. Temporal leak evolution introduces an additional layer of complexity: leaks that develop gradually over time may not produce the abrupt deviations typically targeted by change-detection techniques. Studies based on CUSUM and pattern-clustering have shown that slowly increasing leaks tend to blend with the natural diurnal variability of the network, escaping timely detection [53,54]. Research on incipient pipe failures similarly demonstrates that small early-stage bursts produce subtle pressure variations that are easily masked by operational noise and demand shifts [51]. Overall, reviews underline that realistically evolving multi-leak scenarios remain challenging for most existing detection and localisation strategies [13,24].

These interdependencies illustrate how compounding uncertainties make leak localisation significantly more challenging in practice than in controlled academic settings. For instance, a moderate leak occurring in a district with fluctuating consumption and noisy sensors may remain undetected for extended periods, while small modelling imperfections introduced during baseline calibration can absorb pre-existing leaks and prevent their later identification [52,58]. As emphasised by recent reviews, the combined impact of uncertain demands, noisy measurements, evolving leaks and limited baseline knowledge can easily exceed the robustness of traditional localisers, reinforcing the need for advanced hybrid, probabilistic, and physics-informed approaches capable of operating effectively under realistic conditions [13,24].

4. Conclusions

In recent years, research on leak locations in water networks has made significant progress in bridging the gap between simplified model assumptions and the complexity of real-world operating conditions. From the points examined in this review, the following key conclusions emerge:

- Traditional model-based methods offer high performance under ideal conditions (accurate model, known demand, clean data, and single loss). However, such conditions rarely occur in real networks. The assumptions of deterministic demand, ideal sensors, single faults, and stationary losses are all critical issues that can compromise the effectiveness in the field.

- More recent research has tended to incorporate uncertainty and variability within algorithms. These include online demand estimation, probabilistic models for measurement errors, multiple loss tolerance, and continuous dynamic analysis. Bayesian and robust optimization methods explicitly integrate model and data uncertainties, improving the resilience of diagnoses. At the same time, the combined use of data-driven techniques makes it possible to alleviate reliance on perfect patterns and to learn loss patterns from the data.

- When a calibrated model and good data are available, model-based methods provide highly accurate localisations. The challenge is to extend these benefits to the entire network, overcoming the constraints of the calibrated models. In this sense, a key contribution is the optimisation of sensor placement; placing an optimal number of sensors in the right places can reduce uncertainty and make a less calibrated model useful for detecting leaks.

- In real-world settings, providing the manager with not only information about the presence of the leak but also a confidence interval or probability of correctness is critical for decisions (prioritising interventions and allocating leak detection resources). Many recent methods have adopted this probabilistic approach by assigning likelihoods to possible locations. This represents a bridge to industrial adoption, as it helps integrate leak detection systems into utility decision-making in a transparent and phased manner.

- However, some future challenges remain to be resolved. In particular, as emphasised by several authors, it is a priority to address the multileakage problem systematically. In addition, the scalability of algorithms to very large networks with thousands of nodes requires further improvements in computational efficiency; model reduction techniques, expeditious hydraulic simulation methods, and more efficient optimisation algorithms will be crucial for applying real-time model-based analysis to entire cities. Another strand is the integration of heterogeneous data sources, for example, correlating the results of hydraulic models with data from acoustic leak sensors, GIS information on pipes (material, age, and breakage history), and citizen reports to have a complete and robust diagnostic system.

In conclusion, the evolution of leak location methods is progressing towards solutions that combine physical rigour and adaptability to data, gradually reducing the distance between theory and practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.L.C. and S.P.; methodology, S.P.; formal analysis, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L.C.; writing—review and editing, S.P.; and supervision, G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was carried out in the framework of the RETURN (National Recovery and Resilience Plan—NRRP, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3—D.D. 12432/8/2022, PE0000005) project.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alves, D.; Blesa, J.; Duviella, E.; Rajaoarisoa, L. Data-driven leak localization in WDN using pressure sensor and hydraulic information. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom, B.; Liemberger, R.; Marin, P. The Challenge of Reducing Non-Revenue Water (NRW) in Developing Countries—How the Private Sector Can Help: A Look at Performance-Based Service Contracting; Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Board Discussion Paper Series; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Giustolisi, O. Water Distribution Network Reliability Assessment and Isolation Valve System. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, I.; Alvisi, S.; Franchini, M. A Comparison of Model-Based Methods for Leakage Localization in Water Distribution Systems. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 5711–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucelli, D.B.; Simone, A.; Berardi, L.; Giustolisi, O. Optimal Design of District Metering Areas for the Reduction of Leakages. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustolisi, O.; Ciliberti, F.G.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.B. Leakage Management Influence on Water Age of Water Distribution Networks. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2021WR031919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cognata, R.; Piazza, S.; Freni, G. Pollutant Monitoring Solutions in Water and Sewerage Networks: A Scoping Review. Water 2025, 17, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.; Sanz, G.; Puig, V.; Quevedo, J.; Escofet, M.A.C.; Nejjari, F.; Meseguer, J.; Cembrano, G.; Tur, J.M.M.; Sarrate, R. Leak Localization in Water Networks: A Model-Based Methodology Using Pressure Sensors Applied to a Real Network in Barcelona. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2014, 34, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, A.; Areti, V.S.; Brill, D.; Mahinthakumar, G.K. Successive Linear Approximation Methods for Leak Detection in Water Distribution Systems. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Yan, H.; Li, S.; Tao, T.; Xin, K. Fast Detection and Localization of Multiple Leaks in Water Distribution Network Jointly Driven by Simulation and Machine Learning. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 05022005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadiha, M.; Blesa, J.; Soldevila, A.; Puig, V. Leak Localization in Water Distribution Networks using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Paris, France, 23–26 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Soldevila, A.; Blesa, J.; Tornil-Sin, S.; Duviella, E.; Fernandez-Canti, R.M.; Puig, V. Leak localization in water distribution networks using a mixed model-based/data-driven approach. Control Eng. Pract. 2016, 55, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ben, L.; Alves, D.; Blesa, J.; Cembrano, G.; Puig, V.; Duviella, E. Leak detection and localization in water distribution networks: Review and perspective. Annu. Rev. Control 2023, 55, 392–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelieri, A.; Soldi, D.; Conti, D.; Archetti, F. Analytical Leakages Localization in Water Distribution Networks through Spectral Clustering and Support Vector MACHINES. The Icewater Approach. Procedia Eng. 2014, 89, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Parellada, B.; Puig, V.; Cembrano, G. Leak Localization in Water Distribution Networks Using Pressure and Data-Driven Classifier Approach. Water 2020, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachla, D.; Przystalka, P.; Moczulski, W. A Method of Leakage Location in Water Distribution Networks using Artificial Neuro-Fuzzy System. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puust, R.; Kapelan, Z.; Savic, D.A.; Koppel, T. A review of methods for leakage management in pipe networks. Urban Water J. 2010, 7, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Kuhanestani, P.K.; Farmani, R.; Keedwell, E. Literature Review of Data Analytics for Leak Detection in Water Distribution Networks: A Focus on Pressure and Flow Smart Sensors. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 03122002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrachimis, S.G.; Eliades, D.G.; Taormina, R.; Kapelan, Z.; Ostfeld, A.; Liu, S.; Kyriakou, M.; Pavlou, P.; Qiu, M.; Polycarpou, M.M. Battle of the leakage detection and isolation methods. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louriero, D.; Amado, C.; Martins, A.; Vitorino, D.; Mamade, A.; Coelho, S.T. Water distribution systems flow monitoring and anomalous event detection: A practical approach. Urban Water J. 2016, 13, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, I.; Alvisi, S.; Franchini, M. Analysis of MNF and FAVAD Model for Leakage Characterization by Exploiting Smart-Metered Data: The Case of the Gorino Ferrarese (FE-Italy) District. Water 2021, 13, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, D.; Tiwari, M.K.; Gupta, A.K.; Sen, D. A review of leakage detection strategies for pressurised pipeline in steady-state. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 109, 104264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, K.B.; Hamam, Y.; Abe, B.T.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M. Leakage Detection and Estimation Algorithm for Loss Reduction in Water Piping Networks. Water 2017, 9, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Tan, D.; Shen, D. Review of model-based and data-driven approaches for leak detection and location in water distribution systems. Water Supply 2021, 21, 3282–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; Sage, P.; Turtle, D. Pressure-Dependent Leak Detection Model and Its Application to a District Water System. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2010, 136, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, C.; Kapelan, Z. Real-time Burst Detection in Water Distribution Systems Using a Bayesian Demand Forecasting Methodology. Procedia Eng. 2015, 119, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, G.; Suh, J.C.; Lee, J.M. Online Burst Detection and Location of Water Distribution Systems and Its Practical Applications. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2016, 142, 04015033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustolisi, O.; Savic, D.A.; Kapelan, Z. Pressure-Driven Demand and Leakage Simulation for Water Distribution Networks. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2008, 134, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mücke, N.T.; Pandey, P.; Jain, S.; Bohté, S.M.; Oosterlee, C.W. A Probabilistic Digital Twin for Leak Localization in Water Distribution Networks Using Generative Deep Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, J.A.; Coutu, S.; Smith, I.F.C. Model falsification diagnosis and sensor placement for leak detection in pressurized pipe networks. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2013, 27, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G.; Paal, S.G.; Smith, I.F.C. Leak Detection of Water Supply Networks Using Error-Domain Model Falsification. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2018, 32, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menapace, A.; Avesani, D.; Righetti, M.; Bellin, A.; Pisaturo, G. Uniformly Distributed Demand EPANET Extension. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 2165–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudar, R.S.; Liggett, J.A. Leaks in Pipe Networks. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1992, 118, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.; Puig, V.; Pascual, J.; Quevedo, J.; Landeros, E.; Peralta, A. Methodology for leakage isolation using pressure sensitivity analysis in water distribution networks. Control Eng. Pract. 2011, 19, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinas, D.; Perelman, G.; Ostfeld, A. Water Leak Localization Using High-Resolution Pressure Sensors. Water 2021, 13, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashford, J.; De Silva, D.; Burn, S.; Marney, D. Leak Detection in Simulated Water Pipe Networks Using SVM. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2012, 26, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounce, S.R.; Mounce, R.B.; Boxall, J.B. Novelty detection for time series data analysis in water distribution systems using support vector machines. J. Hydroinform. 2011, 13, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapelan, Z.S.; Savic, D.A.; Walters, G.A. A hybrid inverse transient model for leakage detection and roughness calibration in pipe networks. J. Hydraul. Res. 2003, 41, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffelbauer, D.B.; Deuerlein, J.; Gilbert, D.; Abraham, E.; Piller, O. Pressure-Leak Duality for Leak Detection and Localization in Water Distribution Systems. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 04021106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A.F.; Lee, P.; Karney, B.W. A selective literature review of transient-based leak detection methods. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2009, 2, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-J.; Lambert, M.F.; Simpson, A.R.; Liggett, J.A.; Vı’tkovský, J.P. Leak Detection in Pipelines using the Damping of Fluid Transients. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2002, 128, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítkovský, J.P.; Simpson, A.R.; Lambert, M.F. Leak Detection and Calibration Using Transients and Genetic Algorithms. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2000, 126, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, L.; Ugarelli, R.; Røstum, J.; Giustolisi, O. Assessing Mechanical Vulnerability in Water Distribution Networks under Multiple Failures. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 2586–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Yu, X.; Ma, Z. Multiple Leakage Detection and Isolation in District Metering Areas Using a Multistage Approach. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, M.V.C.; Castañón, L.E.G.; Cayuela, V.P. Model-based leak detection and location in water distribution networks considering an extended-horizon analysis of pressure sensitivities. J. Hydroinform. 2014, 16, 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, S.; Alfonso, L.; van Andel, S.J.; Koole, W.; Groenewegen, A.; Van De Giesen, N.C. A Shazam-like Household Water Leakage Detection Method. Procedia Eng. 2017, 186, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.; Blesa, J.; Puig, V.; Cembrano, G. Clustering-Learning Approach to the Localization of Leaks in Water Distribution Networks. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaller, J.; van Zyl, J.E.; Kabaasha, M. Characterising the pressure-leakage response of pipe networks using the FAVAD equation. Water Supply 2015, 15, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.S.; Zhang, J.X.; Xie, C.L.; Yang, Y.L. Detection of multiple leakage points in water distribution networks based on convolutional neural networks. Water Supply 2019, 19, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Shi, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. A Real-Time Method to Detect the Leakage Location in Urban Water Distribution Networks. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiunas, D.; Vítkovský, J.; Olsson, G.; Lambert, M.; Simpson, A. Failure monitoring in water distribution networks. Water Sci. Technol. 2006, 53, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunone, B.; Ferrante, M. Pressure waves as a tool for leak detection in closed conduits. Urban Water J. 2004, 1, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliades, D.G.; Polycarpou, M.M. Leakage fault detection in district metered areas of water distribution systems. J. Hydroinform. 2012, 14, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Guan, Y. Burst detection in district metering areas using a data driven clustering algorithm. Water Res. 2016, 100, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Shu, S.; Li, D. A Unified Spatial-Pressure Sensitivity Partitioning and Leakage Detection Method within a Deep Learning Framework. Water 2024, 16, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zeng, H.; Wu, X.; Zheng, G. Leakage Break Diagnosis for Water Distribution Network Using LSTM-FCN Neural Network Based on High-Frequency Pressure Data. Water 2025, 17, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolani, G.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.; Simone, A.; Martino, R.; Giustolisi, O. Estimating Leakages in Water Distribution Networks Based Only on Inlet Flow Data. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A. What Do We Know About Pressure: Leakage Relationships in Distribution Systems? In Proceedings of the IWA Specialised Conference—System Approach to Leakage Control and Water Distribution Systems Management, Brno, Czech Republic, 16–18 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T. Data-Driven Leak Detection and Identification in Water Distribution Networks using Transductive Long Short-Term Memory. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Data Science and Information System (ICDSIS), Hassan, India, 17–18 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, I.; Pesantez, J.; Letzgus, S.; Fasaee, M.A.K.; Alghamdi, F.; Berglund, E.; Mahinthakumar, G.; Cominola, A. A Sequential Pressure-Based Algorithm for Data-Driven Leakage Identification and Model-Based Localization in Water Distribution Networks. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, F.G.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.B.; Ariza, A.D.; Enriquez, L.V.; Giustolisi, O. From digital twin paradigm to digital water services. J. Hydroinform. 2023, 25, 2444–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.M.; Komeilian, P.; Wan, X.; Farmani, R. Leak detection and localization in water distribution networks using conditional deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. Water Res. 2023, 238, 120012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, I.; Cominola, A. Estimating irregular water demands with physics-informed machine learning to inform leakage detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.02935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; He, Y. Time Series Data Decomposition-Based Anomaly Detection and Evaluation Framework for Operational Management of Smart Water Grid. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Huang, H.; Xin, K.; Tao, T. A review of methods for burst/leakage detection and location in water distribution systems. Water Supply 2015, 15, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrachimis, S.G.; Eliades, D.G.; Polycarpou, M.M. Leak Detection in Water Distribution Systems Using Hydraulic Interval State Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA), Copenhagen, Denmark, 21–24 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sophocleous, S.; Savić, D.; Kapelan, Z. Leak Localization in a Real Water Distribution Network Based on Search-Space Reduction. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugueró-Escofet, M.A.; Puig, V.; Quevedo, J. Optimal pressure sensor placement and assessment for leak location using a relaxed isolation index: Application to the Barcelona water network. Control Eng. Pract. 2017, 63, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrachimis, S.G.; Timotheou, S.; Eliades, D.G.; Polycarpou, M.M. Leakage detection and localization in water distribution systems: A model invalidation approach. Control Eng. Pract. 2021, 110, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, R.; Galelli, S.; Tippenhauer, N.O.; Salomons, E.; Ostfeld, A.; Eliades, D.G.; Aghashahi, M.; Sundararajan, R.; Pourahmadi, M.; Banks, M.K.; et al. Battle of the Attack Detection Algorithms: Disclosing Cyber Attacks on Water Distribution Networks. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrachimis, S.G.; Kyriakou, M.S.; Eliades, D.G.; Polycarpou, M.M. LeakDB: A benchmark dataset for leakage diagnosis in water distribution networks. In Proceedings of the 1st International WDSA/CCWI 2018 Joint Conference, Kingston, ON, Canada, 23–25 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzolani, G.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.; Martino, R.; Simone, A.; Giustolisi, O. A Methodology to Estimate Leakages in Water Distribution Networks Based on Inlet Flow Data Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2016, 162, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustolisi, O.; Ciliberti, F.G.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.B. A Novel Approach to Analyze the Isolation Valve System Based on the Complex Network Theory. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR031304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).