1. Introduction

River confluences are widely recognized as geomorphic nodes where hydrological, sedimentological, and ecological processes interact to shape channel morphology and sediment routing [

1,

2,

3]. Among the depositional landforms associated with these confluences are alluvial fans that form at tributary–mainstream junctions, hereafter referred to as tributary–junction fans (TJFs) [

4]. These features represent localized sediment-storage systems whose activity depends strongly on upstream hydrological and geomorphic conditions. Although TJFs have been documented across a wide range of geomorphic and climatic settings [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], their behaviour in humid, postglacial landscapes remains comparatively underexplored, despite the pronounced hydrological seasonality and material heterogeneity characteristics of cold–temperate environments.

In such postglacial regions, sediment calibre, erodibility, and internal stratigraphy vary sharply over short distances due to the juxtaposition of tills, glaciofluvial deposits, and marine clays. These substrate contrasts strongly influence local TJF morphology, but their spatial and vertical (3D) heterogeneity occurs at scales too discontinuous to be represented reliably in basin-scale morphometric datasets. For this reason, substrate variability is considered here as geomorphic context rather than an explicit predictor, while complementary sedimentological work addresses these controls separately.

TJFs occupy key positions within drainage networks because they mediate sediment transfer between tributaries and trunk channels through varying degrees of structural and functional coupling [

13,

14,

15,

16]. They therefore serve as indicators of where sediment pathways are strongly connected or, conversely, where local decoupling occurs [

17]. In cold–temperate settings, characterized by rapid snowmelt, rain-on-snow events, and high-intensity summer rainfall, the efficiency of sediment delivery to confluences fluctuates markedly. As a result, TJFs capture how hydrological thresholds, confinement, and sediment availability interact to modulate depositional efficiency. These hydrological contrasts also mediate transitions along the fluvial–debris–flood continuum, influencing whether fans aggrade, incise, or remain geomorphically inactive over decadal timescales.

Fan sensitivity in these environments reflects the combined influence of basin morphology, sediment-transfer dynamics, and inherited Quaternary topography [

14,

18]. Numerous studies have shown that morphometric thresholds condition whether tributaries favour debris-flow or fluvial processes [

4,

19,

20]. Indices such as drainage density, hypsometric integral, and the Melton ratio—defined as basin relief divided by the square root of the drainage area—are widely used to infer sediment-transport potential and the likelihood of short-duration, high-energy flows [

21,

22,

23]. In the Chaudière basin, this index is informative because steep headwaters debouch into reaches of variable confinement, producing strong contrasts in sediment-routing efficiency. In humid temperate systems, however, transitions between debris-flow and fluvial dominance are often gradual and strongly modulated by confinement, sediment supply, material properties, and runoff intensity [

10,

24]. Accordingly, the spatial distribution of TJFs can be interpreted as an expression of the connectivity gradient within the watershed [

13,

25]. While Quaternary deposits shape local sediment availability, their fine-scale variability exceeds the resolution of basin-scale metrics and thus provides contextual rather than predictive information in our analysis.

The evolution of alluvial fans typically reflects alternating phases of aggradation and incision driven by both internal feedback and external forcing [

26,

27,

28]. Autogenic adjustments can arise from sediment–topography interactions even under constant boundary conditions, as demonstrated by experimental studies of fan avulsion and topographic compensation [

29,

30]. In natural systems, this behaviour implies that fans serve not only as active sediment conveyors but also as stratigraphic archives recording past changes in sediment supply, flood regime, and climate [

11,

12,

14].

Among the commonly used morphometric indicators, the Melton ratio remains one of the most widely applied proxies for evaluating sediment-transport potential [

31,

32]. However, recent reassessments show that single indices cannot adequately capture the non-linear interactions among relief, slope, drainage configuration, and anthropogenic modification that shape fan behaviour [

11,

19,

27]. In the Chaudière system, these limitations are particularly important because TJFs interact with a structurally controlled mainstem whose varying degrees of valley confinement strongly influence whether fans can accumulate, be preserved, or be rapidly reworked. These limitations underscore the need for integrated approaches that combine morphometric, statistical, and geomorphic analyses to identify thresholds and spatial patterns more robustly. This study adopts such a multivariate framework to link the presence or absence of TJFs along Chaudière tributaries to variations in slope, relief, contributing area, and valley confinement within a cold-region fluvial system. This integrated approach is necessary because TJFs emerge from the combined effects of basin geometry, hydrological variability, sediment availability, and land-use alteration, factors that cannot be captured through bivariate morphometric indices alone.

At tributary–mainstream junctions, fan morphology and occurrence depend on sediment supply, hydrological regime, the degree of coupling with the main channel, and valley confinement [

10,

15]. In the Chaudière River basin, these processes operate within a complex Quaternary mosaic of tills, glaciofluvial sands and gravels, and fine-grained marine deposits inherited from repeated glacial advances and marine submersion [

33,

34,

35]. Field observations indicate that TJF surfaces typically overlie these heterogeneous substrates, reflecting the superposition of recent high-energy floods on older sediment frameworks. Detailed sedimentological and stratigraphic reconstructions at the fan scale fall outside the scope of this basin-wide morphometric study and are treated in complementary work.

Recent hydroclimatic events, such as Tropical Storm Irene in 2011 and the torrential floods of July 2002, when several small tributaries generated damaging flash floods following nearly 100 mm of rainfall, demonstrate the sensitivity of these confluences to short-duration, high-magnitude runoff [

36]. Several tributaries produced coarse gravel lobes, localized avulsions, and rapid sediment pulses. These events demonstrate that, beyond morphometric predisposition, event-scale forcing plays a decisive role in determining whether fans become activated or remain geomorphically inactive within a given hydrological cycle. Such threshold-driven responses are consistent with observations from other humid temperate, postglacial environments, where small catchments exhibit sharp transitions in sediment delivery under extreme discharge conditions [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Against this background, the present study focuses on identifying the basin-scale morphometric controls that govern the spatial occurrence of TJFs across the Chaudière River network and how these controls interact with hydroclimatic variability and local confinement. Because the objective is to characterize spatial patterns at the scale of the entire basin, sedimentological, volumetric, or stratigraphic analyses of individual TJFs fall outside the scope of this exploratory work but provide essential context for interpreting morphometric patterns. Understanding how geomorphic, sedimentary, and hydroclimatic factors combine to shape TJF development in this cold-region fluvial system is therefore central to the broader interpretation of sediment connectivity dynamics across postglacial landscapes [

33,

34,

35].

2. Study Area

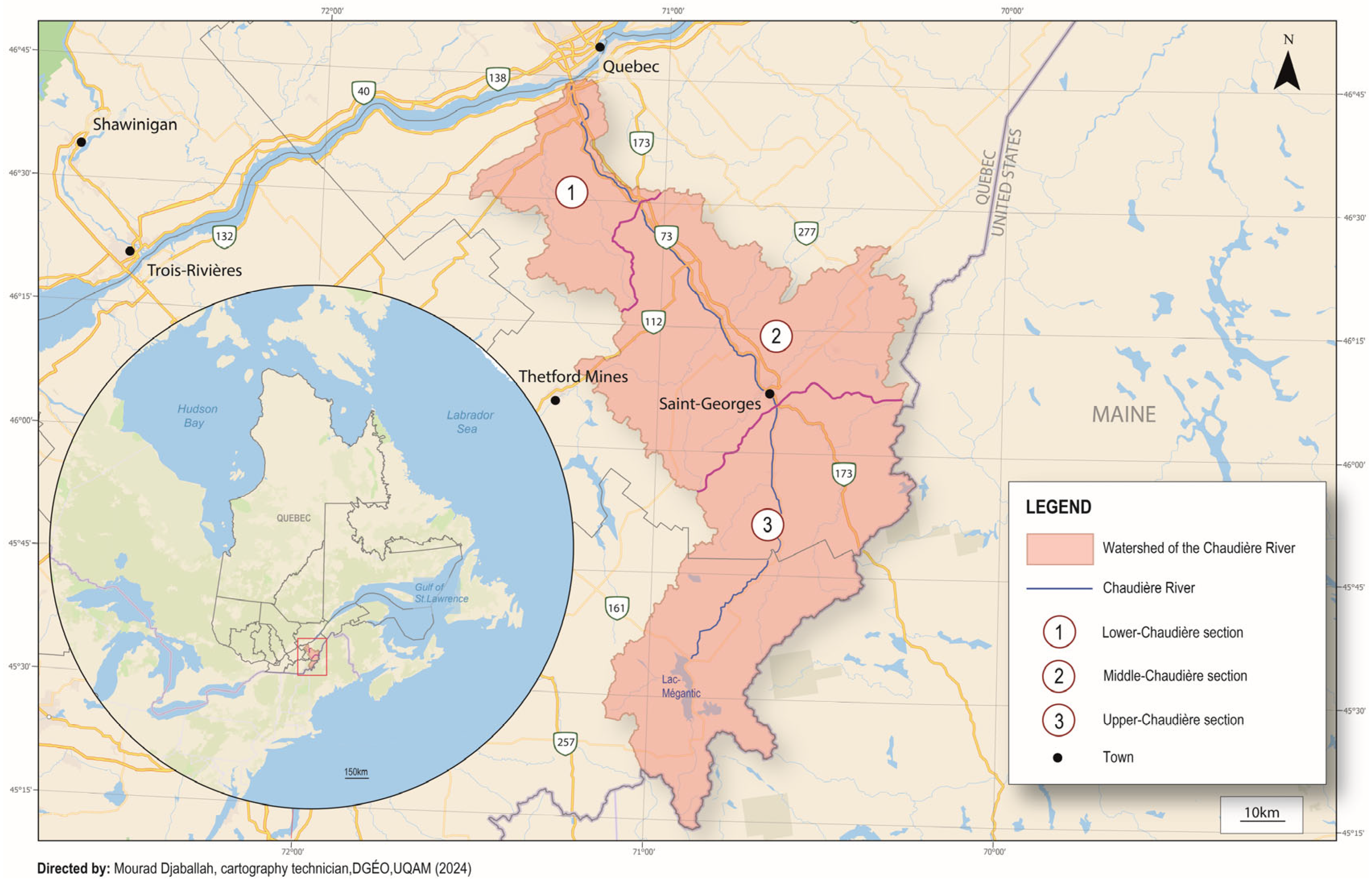

The Chaudière River watershed is located in southeastern Québec, Canada, and covers approximately 6700 km

2 (

Figure 1). The river flows northward over 185 km from Lake Mégantic to the St. Lawrence River, descending a total of about 530 m. Its morphology is strongly conditioned by the Appalachian geological framework, composed mainly of folded and faulted sedimentary rocks, including sandstones, shales, and limestones, that impart pronounced structural control on valley orientation and drainage geometry. The valley network includes narrow, V-shaped tributaries in the upstream portion of the basin and broader, glacially incised troughs downstream [

33,

37,

38]. The watershed is dominated by mixed forest and agricultural land, with urban areas primarily concentrated in its lower part. Such morphological contrasts are characteristic of postglacial fluvial systems in cold–temperate regions, where inherited valley confinement and glacial overdeepening strongly condition sediment connectivity and channel adjustment [

11,

12,

14].

Surficial deposits form a highly heterogeneous Quaternary mosaic of tills, glaciofluvial sands and gravels, and fine-grained marine deposits. This patchwork produces sharp spatial contrasts in substrate erodibility and sediment calibre and locally modifies valley confinement, influencing how individual tributaries deliver sediment to the mainstem. In most tributaries, surface and near-surface sediment is derived primarily from these glacial and glaciofluvial deposits rather than from local, weathered bedrock, reinforcing the strong inherited control on sediment calibre and availability. However, this variability occurs at a finer spatial scale than can be resolved with basin-scale morphometric metrics, and, therefore, it provides geomorphic context rather than an explicit predictor in this analysis.

Three physiographic sectors can be distinguished along the longitudinal profile (

Figure 1). The Upper Chaudière, extending from Lake Mégantic to Saint-Georges, is dominated by steep slopes (gradient of 2.5 m km

–1), coarse sediments, and highly confined tributaries draining the Appalachian Highlands. The Middle Chaudière, between Saint-Georges and Vallée-Jonction, has gentler slopes (gradient of 0.5 m km

–1), broader valley floors, and transitions from confined to semi-confined reaches, including several depositional zones where small TJFs and terraces reflect local sediment storage. The Lower Chaudière, from Vallée-Jonction to the St. Lawrence River, exhibits mixed morphology with alternating confined reaches, short alluvial plains (gradient of 3.0 m km

–1), and a strong anthropogenic imprint from agriculture and urbanization. These longitudinal contrasts mirror those described in other postglacial or tectonically segmented basins, where relief amplitude and valley confinement jointly govern sediment connectivity and TJF development [

7,

8,

10].

Tributaries across the watershed display heterogeneous relief–energy relationships, with basin areas ranging from 2 to 80 km

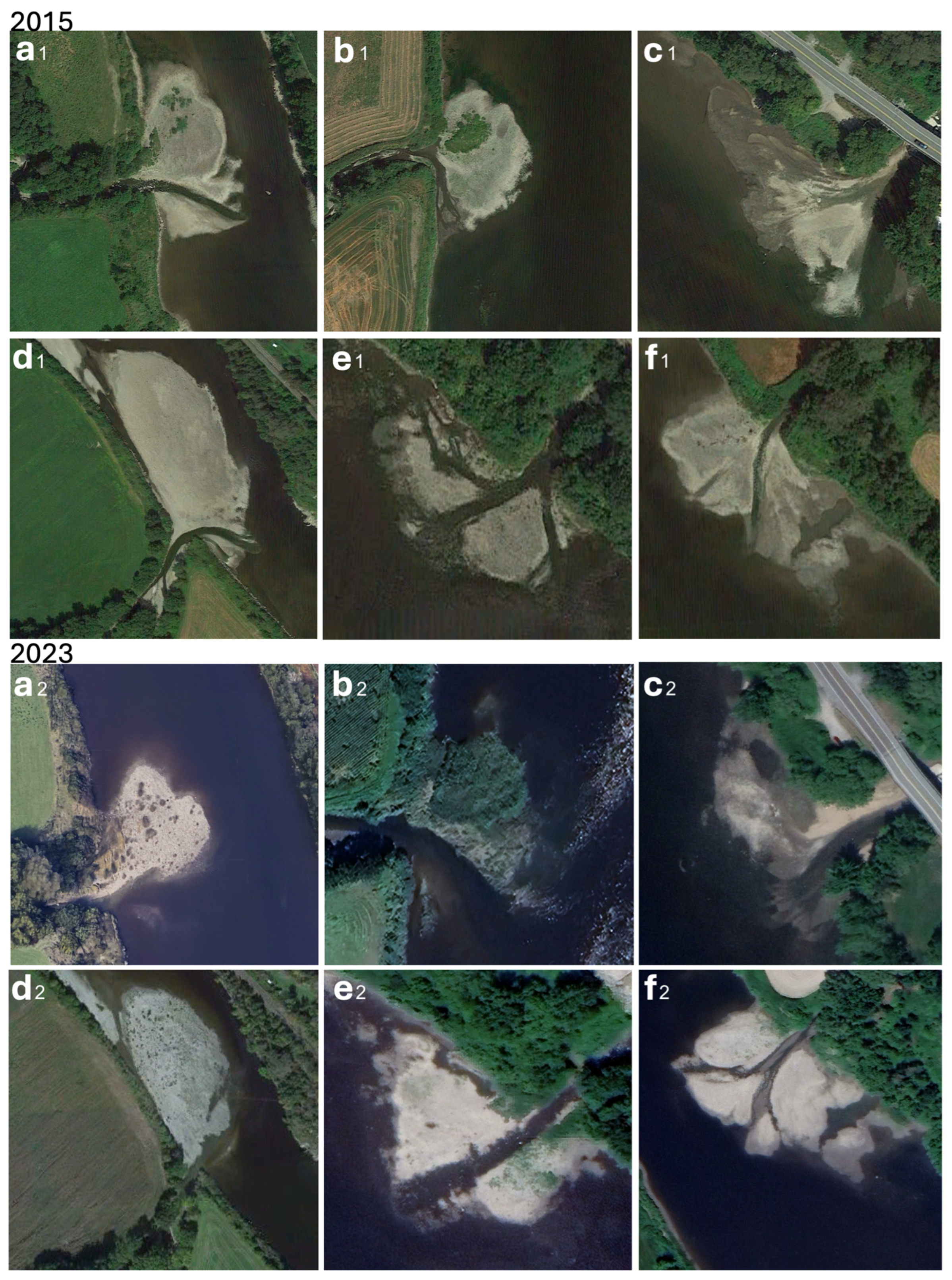

2 and mean slopes from 2° to 22°. Most tributaries enter the mainstem at acute angles (<45°), often producing small depositional lobes or fan–shaped accumulations at their mouths (

Figure 2), some of which persist because local channel geometry shields them from direct mainstem erosion. TJF surfaces vary from <0.05 to >0.5 km

2, reflecting marked differences in sediment-transfer efficiency among sub-catchments.

Recent hydroclimatic events provide insights into sediment-delivery thresholds. The regional-scale floods of 2011 (Tropical Storm Irene) and 2002 (torrential floods) mobilized large sediment volumes in many tributaries, reworking several TJFs [

39,

40,

41]. Field inspections further show that most TJF surfaces consist of thin gravel and cobble veneers draped over heterogeneous glacial or glaciofluvial deposits, typically less than ~1 m thick. This indicates that surficial morphology reflects recent high-energy events, while deeper stratigraphy, although not examined in this study, likely preserves older inherited postglacial frameworks.

The region experiences a humid continental climate with cold winters and warm summers (mean annual temperature ~3.5 °C), and a mean annual precipitation of ~1050 mm. Hydrology is influenced by two distinct but complementary forcing mechanisms operating at different spatial scales, each shaping TJF dynamics in characteristic ways. At the basin-wide scale, snow accumulation in winter, rapid meltwater peaks in April–May, and episodic rain-on-snow events generate high discharges that affect the mainstem and medium-to-large tributaries, driving the reactivation of larger fans and promoting floodplain adjustment. At a finer scale, highly localized small-to-medium tributaries (1–20 km

2) respond sharply to intense, short-duration convective summer rainfall storms, which can produce localized flash floods whose peak discharges may temporarily exceed those in the main channel. These short-lived but powerful events mobilize coarse sediment and generate sediment pulses capable of constructing or reworking TJFs. Together, these regional spring floods and highly localized summer thunderstorms create a strongly pulsed sediment-transfer regime [

3,

19] characterized by alternating periods of disconnection (winter freezing, snowpack accumulation) and reconnection (spring melt, summer convective runoff). This duality contrasts with the predictable seasonality of alpine basins and the event-driven intermittency typical of arid systems [

11,

12], but it is broadly representative of cold–temperate postglacial rivers where both basin-wide melt events and localized convective storms co-determine sediment delivery. This context highlights the distinctive hydrogeomorphic signature of TJF dynamics in the Chaudière watershed.

Overall, the Chaudière River provides an ideal natural laboratory for studying tributary-driven depositional dynamics. Its tributaries span wide morphometric contrasts, and its heterogeneous Quaternary deposits create strong local variations in sediment calibre and availability. The hydroclimatic regime further enhances this variability; basin-wide spring floods and highly localized convective summer storms both produce threshold-controlled sediment delivery capable of activating or reworking TJFs. Because these fans respond sensitively to both regional and tributary-scale forcing, they serve as valuable indicators of sediment connectivity in cold–temperate postglacial settings. As this study focuses on basin-scale morphometric patterns, detailed sedimentological or stratigraphic reconstructions of individual fans are addressed in complementary work.

3. Methods

This study combines geomorphometric, GIS-based, and statistical analyses to examine the spatial distribution of TJFs along the Chaudière River. The methodological workflow includes three main components: (1) morphometric data extraction from high-resolution topographic and hydrological datasets; (2) systematic and criteria-based identification of TJF presence or absence at tributary–mainstem junctions; and (3) multivariate statistical analyses to evaluate the influence of morphometric controls on TJF occurrence. This structured workflow was designed to ensure reproducibility, transparent identification criteria, and robust evaluation of morphometric predictors, directly addressing common challenges in fan-mapping and confluence studies.

3.1. Data Sources and Processing

Topographic and hydrological variables were derived from a 1 m LiDAR Digital Elevation Model (DEM) provided by the Québec Ministry of Environment. Hydrological features (river network, watershed boundaries) were obtained from the provincial BDTQ geospatial database and manually validated against high-resolution orthophotos (2020–2022). Land-cover layers were incorporated only to identify anthropogenic surfaces (agriculture, roads, urbanized areas) that could influence drainage pathways or modify local slope conditions.

The integration of LiDAR and orthophotographic datasets follows recent best practices in fan-mapping and confluence-scale geomorphology [

16]. This ensured consistent detection of slope breaks, fan lobes, and valley geometry, and avoided misclassification of bars and terraces as fans. It also aligns with recent advances emphasizing the role of topographic thresholds, sediment-routing pathways, and energy gradients in TJF genesis and connectivity [

7,

25]. All GIS processing was conducted using ArcGIS Pro 3.0 (ESRI) and QGIS 3.22, while morphometric computations, watershed delineation, and database assembly were performed in R, with all hydrological parameters applied consistently across the 142 tributaries to ensure comparability among basins.

3.2. Morphometric Variables

For each tributary watershed, morphometric parameters were extracted, including drainage area (A), basin relief (Rf), and the slope × area product (S × A), used as a proxy for sediment-supply potential. Secondary morphometric indices were computed from these variables: drainage density (Dd), Gravelius compactness index (Kg), hypsometric integral (Hi), and the Melton coefficient (Mc). Their definitions, calculation methods, and geomorphic significance are summarized in

Table 1. These variables were selected because of their widespread relevance in alluvial fan morphometry and confluence dynamics [

22,

42,

43].

Relief, slope, and drainage area jointly define the tributary’s energetic potential for sediment transfer and influence whether material is stored or efficiently evacuated [

25,

30]. The S×A index was included to integrate both topographic forcing and contributing area, following approaches that couple sediment-supply and transport-efficiency predictors [

16]. Although the Melton ratio is frequently used to infer debris-flow propensity, in this study it is used only as a geomorphometric descriptor, not a process-based classifier.

Each tributary watershed was also assigned an anthropogenic disturbance level based on the proportion of surface area visible modified by human activities. Disturbance was assessed using Google Earth Pro and recent high-resolution orthophotos (2020–2022) and quantified as the percentage of land affected by agriculture, road networks, channelization, bank stabilization, or urban development. These categories were defined as follows: A (>50% anthropogenic cover), strongly modifies basins with extensive agricultural or urban footprints; B (10–50%), moderately disturbed tributaries with mixed land use; C (<10%), minimally disturbed, mostly forested basins. These thresholds were selected because mapping revealed clear breaks in land-use dominance around 10% and 50%, and sensitivity tests using alternate boundaries (5–30–60%) produced similar patterns. This confirms that the A/B/C classes capture meaningful shifts in disturbance intensity rather than arbitrary divisions. The categories were used as categorical predictors in the statistical analyses to test whether human disturbance moderates morphometric controls on TJF occurrence.

Presence or absence of TJFs was determined from multi-temporal aerial imagery. A fan was classified as present when exhibiting (i) an outward convex depositional form, (ii) a slope break between tributary and the trunk channel, and (iii) visible textural contrasts consistent with coarse clastic deposition [

26,

32,

49]. Each confluence was assigned a binary value (1 = fan; 0 = no fan), enabling categorical analyses. A total of 142 tributary watersheds were delineated, of which 41 exhibited clearly identifiable TJFs. Ambiguous landforms (e.g., lateral benches, point bars, abandoned channels) were excluded. Multi-temporal imagery from Google Earth (2004–2023) and historical aerial photographs were used to verify that mapped TJFs were persistent features visible across several decades. This step ensured that TJFs were not misinterpreted from short-lived gravel lobes, temporary sediment tongues, or periods when high water levels submerged the fan surface. Only landforms consistently detectable through time were retained, providing confidence that the mapped features represent stable depositional forms rather than transient flood deposits.

Field validation was conducted in the Middle Chaudière, identified as the most flood-prone sector [

40,

41,

50]. A total of 20 TJFs were visited to verify mapping accuracy, but only 10 were selected for grain-size analysis based on accessibility, safety, and logistical feasibility. This ensured consistent sampling across representative fan surfaces while avoiding sites where steep terrain, private property, or restricted access prevented fieldwork. Grain-size analysis was conducted using dry sieving (<0.063 mm to >32 mm) following standard procedures, and particle-size distributions were classified according to Blott & Pye [

51]. For each TJF, the 100 largest clasts were also measured along their a-axis to document maximum particle size. Field visits also showed that surficial fan deposits are generally composed of thin gravel and cobble veneers overlying heterogeneous glacial or glaciofluvial substrates. Grain-size data were collected to characterize surface texture but were not included as predictors in the statistical analyses.

3.3. Statistical Analyses

Three complementary statistical methods were used to explore the relationships between morphometric variables and TJF presence/absence: principal component analysis (PCA), classification and regression tree (CART), and linear discriminant analysis (LDA). This integrated framework was designed to reduce data dimensionality, identify the most influential morphometric predictors, and evaluate classification performance. These multivariate approaches were selected to move beyond the limits of traditional bivariate regressions [

52,

53,

54,

55], which capture only linear relations and cannot resolve non-linear interactions among basin geometry, relief, and anthropogenic disturbance. PCA, CART, and LDA are widely used in geomorphology and together allow the detection of both gradient-based (PCA, LDA) and threshold-based (CART) signals.

In addition, Chi-square tests and contingency tables were used to evaluate interdependencies among categorical variables, particularly anthropogenic disturbance (A > 50%, B = 10–50%, C < 10%) and TJF presence/absence. All Chi-square tests were evaluated at α = 0.05.

PCA was first used to summarize covariation among morphometric parameters and to identify the dominant geomorphic gradients structuring the dataset [

56,

57]. The analysis was based on a correlation matrix using standardized variables (Z-scores), ensuring that all parameters contributed equally regardless of their original scales. Components with eigenvalues >1 were retained for interpretation. Variable loadings were examined to identify the combination of slope, relief, and drainage area that captured the greatest proportion of variance. PCA thus served to visualize tributary clustering and to highlight the energy–relief–size continuum influencing sediment-transfer potential [

11,

16].

A CART model [

58,

59] was then used to discriminate between confluences with and without fans. This non-parametric method recursively partitions the dataset based on threshold values of morphometric predictors. The algorithm minimizes within-group variance of the dependent variable (fan = 1; no fan = 0) using the Gini impurity index as the splitting criterion. Tree complexity was controlled through 10-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting. The relative importance of predictors was derived from total reduction in node impurity. This approach provides a transparent, rule-based framework to identify morphometric thresholds potentially associated with TJF formation [

21,

60]. Because the dataset is unbalanced (41 fans vs. 101 non-fans), CART sensitivity was expected to be limited; this issue is explicitly addressed in the Discussion.

An LDA was applied to test the predictive performance of morphometric variables and to quantify classification accuracy. LDA assumes multivariate normality within groups and seeks a linear combination of predictors that maximizes the separation between the two classes (fan presence/absence). Model performance was evaluated as the percentage of correctly classified confluences. LDA was chosen because of its interpretability and its frequent application in morphometric studies dealing with categorical outcomes and limited sample sizes. Confusion matrices were used to report sensitivity, specificity, and overall classification accuracy.

The combined use of PCA, CART, and LDA provides complementary insights: PCA reduces redundancy and highlights dominant gradients in the dataset; CART identifies threshold values and interaction effects; LDA maximizes group separation and quantifies classification accuracy. To assess model robustness, 1000 bootstrap simulations were conducted for both CART and LDA. In each iteration, 100 watersheds were randomly selected for model construction, and the remaining 42 were used for validation. Performance was evaluated using sensitivity (correct classification of fan presence), specificity (correct classification of fan absence), and overall accuracy. This repeated resampling procedure reduces the risk of overfitting and yields more reliable performance metrics than a single-model calibration. Bootstrap distributions (median, interquartile range) were later used to interpret classification performance in

Section 5.3.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Morphometry and Tributary–Junction Fan Distribution

A total of 142 tributary watersheds were delineated along the Chaudière River basin, of which 41 exhibit TJFs at their confluence with the main channel. Fan-bearing tributaries represent roughly 29% of all junctions and are predominantly concentrated in the Middle Chaudière (28/41, ~68%) where slopes are gentler and accommodation space is greater. In contrast, Upper tributaries are narrower, steeper, and more confined, limiting the potential for TJF development or preservation. Summary statistics of the main morphometric parameters for the Upper, Middle, and Lower sections are provided in

Table 2.

Drainage areas range from 0.8 km2 to 81 km2 (mean = 18.7 km2), and mean basin slopes between 2.1° and 21.8° (mean = 9.6°). Fan-forming tributaries generally display larger contributing areas (mean = 26.4 km2) and lower mean slopes (7.8°) than non-fan basins (mean = 15.2 km2; 10.4°, respectively). Relief varies from 52 m to 621 m, producing Melton ratios between 0.15 and 0.62. These contrasts indicate that TJFs tend to occur under intermediate relief–energy conditions, neither excessively steep (favouring sediment evacuation) nor too subdued (limiting transport capacity). Differences in means between fan and non-fan basins are statistically significant for the drainage area, basin slope, and relief (p < 0.05).

Fan surfaces range from 0.03 km

2 to 0.58 km

2 (mean = 0.21 km

2). Most are asymmetrical and elongate downstream, indicating partial avulsion and lateral reworking driven by interactions with the main channel (

Figure 3). The mean fan-to-basin area ratio (0.9%; range 0.2–3.1%) is consistent with values reported for temperate fluvial systems. Orthophoto comparison suggests limited planform modification over decadal scales, although image timing and water levels limit the inference of activity.

Field validation confirmed that fan surfaces consist of coarse, clast-supported gravel and cobble deposits, with median grain sizes (d

50) ranging from 18 to 36 mm. The 100 largest clast measurements include occasional boulders of >0.5 m. Grain-size analyses for the ten surveyed TJFs are summarized in

Table 3 and document the coarse texture of surface veneers, characterized by high gravel proportions (typically 60–90%) and minimal fines (<1% in most cases).

Fan orientation predominantly follows the regional structural grain toward the northwest. Field validation confirmed that TJF surfaces consist of coarse, clast-supported gravel and cobble deposits, with median grain size (d

50) ranging from 18 to 36 mm and occasional boulders of >0.5 m (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Grain-size distributions for the ten surveyed are given.

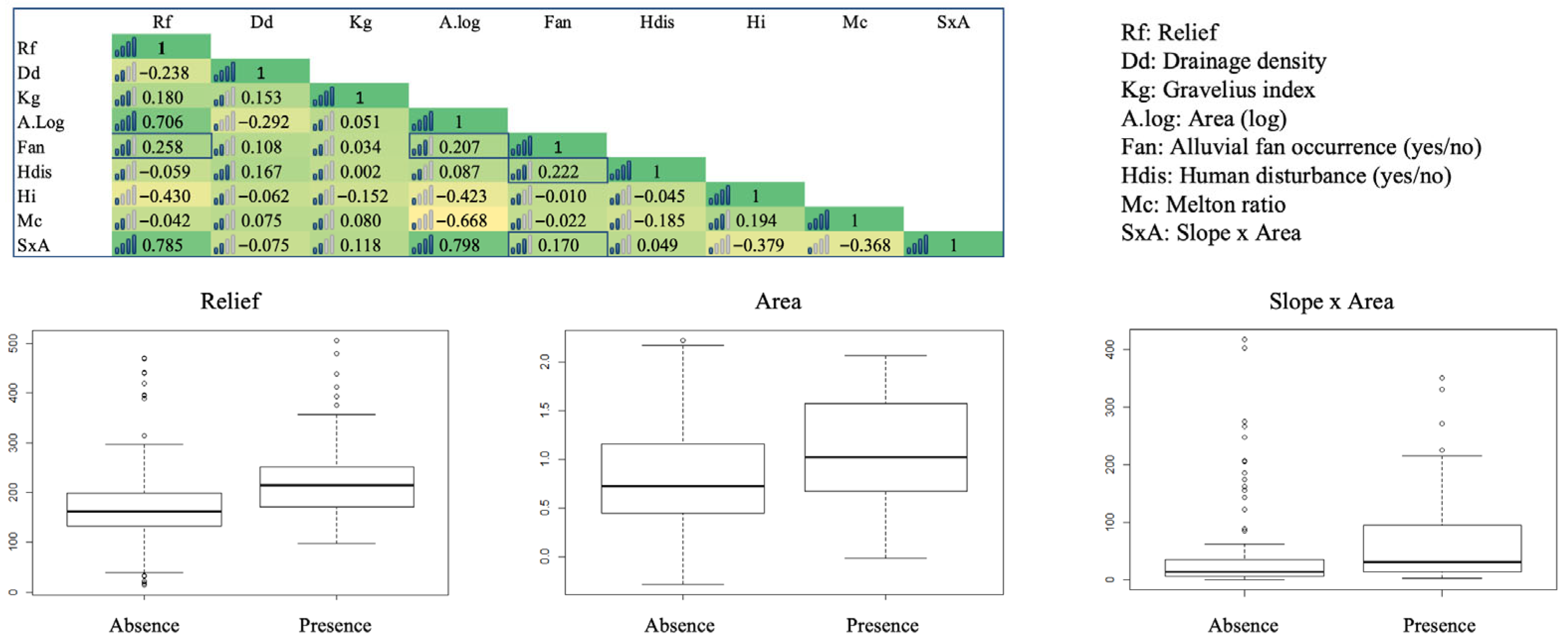

To explore the relationships among morphometric variables and their association with TJF occurrence, a Pearson correlation matrix was computed (

Figure 4). Basin relief (Rf), drainage density (Dd), and log-transformed drainage area (A.log) show the strongest correlations with fan presence. Complementary boxplots illustrate systematic contrasts between basins with and without fans. These exploratory patterns motivated the applications of PCA, CART, and LDA to evaluate the combined morphometric and anthropogenic influences on TJF occurrence.

4.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

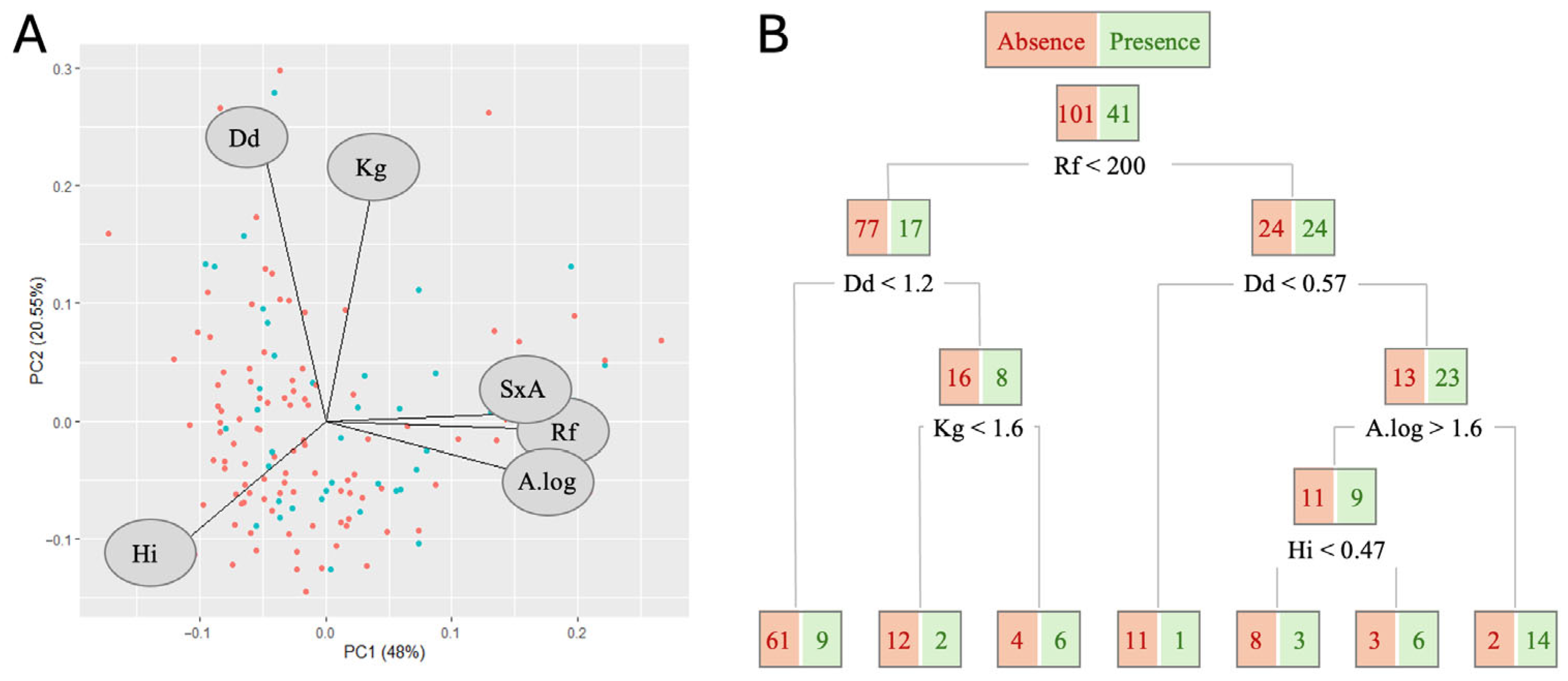

The PCA identified three principal components with eigenvalues >1, explaining 68.6% of the variance. PC1 (48.0%) is strongly influenced by basin relief (Rf), drainage area (A), and S × A, representing a general energy–size gradient associated with sediment production and transport capacity (

Figure 5).

PC2 (20.6%) is controlled by drainage density (Dd) and the Gravelius index (Kg), describing basin elongation and drainage organization (

Figure 5). PC3 (9.8%) captures the residual variability associated with the hypsometric integral (Hi), reflecting headwater relief and topographic maturity. Notably, PCA reveals a partial but distinct clustering of fan-bearing tributaries toward higher PC1 values, corresponding to larger and more energetic basins.

4.3. Classification and Regression Tree (CART)

CART identified basin relief (Rf) as the primary discriminator between basins with and without fans, with a first threshold at Rf = 200 m (

Figure 5B). Low-relief basins (Rf < 200 m) contain a higher proportion of fans.

Within high-relief basins (Rf > 200 m), drainage density (Dd = 0.57) forms the next key split. Tributaries with less dense networks (Dd < 0.57) remain transport dominated. Additional thresholds in the log-transformed drainage area (A.log = 1.6) and hypsometric integral (Hi = 0.47) distinguish basins with a greater likelihood of TJF formation (14 out of 16 cases). These splits correspond to physically interpretable transitions in the relief–energy configuration, drainage-network structure, and the morphological expression of basin dissection in depositional potential.

The final pruned tree yields an accuracy of 66%, with sensitivity of 0.32 (true positives) and specificity of 0.81 (true negatives). Low sensitivity reflects both the unbalanced datasets (41 fans, 101 non-fans) and the inability of morphometric factors alone to capture event-scale hydrological forcing or substrate variability. Cross-validation and bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) confirm the stability of primary splits but underline the limitations of morphometry only prediction. Chi-square analysis (

Table 4) indicates that moderately and highly disturbed basins (10–50% and >50% anthropogenic cover) show higher TJF frequencies, suggesting that land-use changes may modulate morphometric predispositions, either enhancing or suppressing local conditions.

4.4. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

LDA further evaluates predictive performance. LD1 explains 86.7% of between-group variance, and LD2 accounts for 13.3%. Standardized coefficients show that relief (Rf), drainage density (Dd), and A.log contribute most to group separation, followed by hypsometric integral (Hi).

The LDA achieves 76.0% accuracy, with sensitivity of 0.66 and specificity of 0.78. This represents a notable improvement over CART, reflecting the linear structure of the morphometric contrasts. Cross-validation (mean accuracy = 74.8%) confirms model stability. Bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) shows that relief and drainage density were selected in >95% of the iterations, reinforcing their dominant influence. The classification results are summarized in the contingency table (

Table 5).

4.5. Summary of Controlling Factors

The combined results from PCA, CART, and LDA reveal consistent patterns in the morphometric controls associated with the occurrence of TJFs along the Chaudière River. Across all three methods, basin relief, drainage density, and contributing area appear as the most influential predictors.

Relief and drainage area define the dominant gradient in the dataset, as indicated by the high loading on PC1 and the main discriminant coefficients in LD1. Fan-bearing tributaries generally plot toward the higher end of this gradient. Drainage density also contributes strongly to group separation, being highlighted in both PC2 and the main CART splits.

Secondary variables, including the hypsometric integral (Hi) and the Gravelius index (Kg), show weaker but measurable contributions in both PCA (PC2–PC3) and the secondary axes of LDA. These variables appear in deeper CART splits, indicating additional structure in the dataset.

Model performance varies among methods. CART achieves 66% accuracy (sensitivity = 0.32; specificity = 0.81), whereas LDA reaches 76% accuracy (sensitivity = 0.66; specificity = 0.78). Bootstrap resampling confirms that relief, drainage density, and contributing area are consistently selected as the most important predictors across iterations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Morphometric Controls, Connectivity Patterns, and Floodplain Dynamics

The morphometric and statistical analyses indicate that TJF occurrence along the Chaudière River is governed by a consistent set of basin-scale controls, primarily relief, drainage density, and contributing area. These variables delimit an intermediate morphometric domain in which sediment supply and transport capacity tend to balance, favouring deposition at tributary confluences, a pattern also reported in other temperate, Mediterranean, and alpine basins [

4,

7,

11,

12,

14,

19,

61]. Across PCA, CART, and LDA, TJFs are consistently associated with moderate relief energy, larger drainage areas, and lower drainage densities, reflecting partially coupled sediment-transfer conditions at confluence nodes [

13,

15,

62]. The clustering of fan-bearing tributaries toward higher values of PC1 in the results further reinforces that fan-producing basins populate an intermediate segment of the relief–energy continuum rather than its extremes.

Field grain-size data further support this interpretation. The dominance of gravel and cobble fractions (d50 = 18–36 mm) confirms that the TJFs are constructed by high-energy fluvial or debris-flood processes rather than low-energy overbank deposition. The consistent presence of coarse, clast-supported veneers also suggests a limited long-term storage efficiency, which is consistent with partially coupled sediment-transfer regimes at confluences.

This coherence across independent methods strengthens the interpretation that TJF development reflects a reproductible morphometric envelope rather than isolated or site-specific conditions. The concentration of TJFs in the Middle Chaudière corresponds to tributaries entering a sector where the main channel slope decreases and the valley floor widens significantly. This combination reduces longitudinal energy and increases lateral channel mobility, thereby enhancing local accommodation space at confluence nodes. Such settings are well known to favour fan construction and preservation in structurally segmented or postglacial catchments [

7,

8,

10,

24].

However, both CART and LDA exhibit moderate predictive skill, indicating that basin geometry alone cannot fully explain TJF presence. This limitation is consistent with the low CART sensitivity (0.32) and the only moderate discriminatory capacity of LDA (76%), as highlighted in the results. These model behaviours indicate that TJF activation depends not only on morphometric predisposition but also on event-scale hydrological forcing, threshold exceedance, and local variations in substrate or confinement, none of which are explicitly encoded within morphometric predictors. This aligns with studies demonstrating that fan activation often results from the superimposition of discrete hydrological events on pre-existing morphometric thresholds [

12,

17,

27]. These thresholds help explain the persistence of TJFs between major floods, since coarse surficial deposits remain largely immobile under normal discharge conditions. Model limitations also stem from the absence of substrate-related controls, as lithological contrasts and material properties strongly influence sediment availability and transport thresholds yet remain unrepresented in basin-scale indices. As a result, model skill likely reflects both intrinsic morphometric variability and unmodelled substrate controls, which together help to explain why TJFs respond so sensitively to threshold-exceeding events.

Recent hydrometeorological events, particularly those of 2011 and 2002, illustrate this interaction, as several mapped TJFs were reactivated during intense rainfall [

39,

40,

41]. These episodes demonstrate that TJFs operate as sensitive, threshold-controlled nodes, where relatively small variations in discharge or sediment availability can shift the system from throughput to deposition. TJFs in the Chaudière basin therefore reflect confluence zones where sediment coupling fluctuates dynamically between storage and transfer depending on both basin structure and recent hydrological conditions at both local and regional scales.

5.2. Energy Thresholds and Sediment-Transfer Regimes

The morphometric patterns identified along the Chaudière River indicate that TJFs develop within an intermediate energy domain defined by contributing area, mean slope, and drainage density. These variables jointly delimit a range of basin configurations where sediment supply is sufficient for deposition but not high enough to promote continuous downstream evacuation. Similar threshold-like behaviour has been documented in cold–temperate, alpine, and postglacial basins, where fan formation is associated with moderate relief energy and partially efficient drainage networks [

12,

24,

25,

27,

61].

In the Chaudière system, this intermediate domain includes tributaries with drainage areas of 20–40 km

2, moderate slope (6–9°), and relatively low drainage densities. These conditions align with the functional connectivity framework described by Harvey [

13,

14], in which TJFs act as transient storage zones at transitions between transport-dominated and storage-dominated reaches.

Grain-size results reinforce this interpretation. The prevalence of coarse gravels and cobbles indicates that only high-energy floods can meaningfully construct or rework TJFs. The minimal fine fraction (<5%) implies low trapping efficiency, supporting the idea that TJFs serve as intermittently activated storage zones subject to reworking during high-magnitude events. Thus, the granulometric evidence is consistent with a threshold-controlled sediment-transfer regime rather than continuous aggradation.

While CART and LDA reinforce the existence of these indicative morphometric ranges, their broad classification margins and moderate predictive power suggest that thresholds are diffuse rather than sharply defined. This diffuseness reflects the complex interplay of inherited Quaternary deposits, variability in surface material calibre, and fluctuations in channel confinement, which collectively blur simple morphometric boundaries. This is consistent with our results showing that fan-bearing tributaries cluster within, but not tightly around, the intermediate PC1 domain.

Comparable mid-energy confluence systems have been documented in the southern Alps [

25] and glaciated Icelandic catchments [

7,

61], where short tributaries feeding confined trunk channels generate fans that are periodically reworked during high-magnitude events. The Chaudière results align with this broader category; TJFs are not purely morphometric products but process-mediated landforms shaped by periodic exceedance of hydrological thresholds. Thus, TJFs in the Chaudière basin occupy a morphometric niche consistent with similar cold–temperate settings. They form under intermediate energy and drainage configurations that favour partial decoupling, intermittent sediment storage, and rapid reactivation under event-driven forcing.

5.3. Anthropogenic Disturbance and Disrupted Connectivity

The results indicate that anthropogenic disturbance exerts a secondary but measurable influence on TJF occurrence. Tributaries with moderate disturbance levels (10–50%) contain the highest proportion of fans, whereas heavily modified or minimally disturbed basins show lower frequencies. This pattern suggests that land-use alteration, channel modification, and infrastructure placement can locally modify sediment pathways and affect the balance between storage and transfer [

14,

18,

63,

64,

65].

Moderate disturbance may enhance partial decoupling at confluences, for example, when small-scale agricultural clearing on lower slopes increases sediment availability, or when road crossings, culverts, and embankments subtly modify tributary hydraulics and local confinement. Disturbed basins are also prone to producing higher unit runoff during storm events because reduced infiltration, soil compaction, and increased imperviousness promote rapid overland flow. This hydrological response can amplify peak discharges at tributary outlets and mobilize short, sediment-rich pulses capable of constructing or reworking TJFs.

In addition, anthropogenic structures may also locally steepen or smooth tributary channel slopes. Straightened reaches or roadside ditches can accelerate sediment delivery, whereas bank stabilization or channel rectification can reduce roughness and promote hydraulically efficient low-gradient segments. These adjustments influence whether sediment is rapidly exported or instead deposited near tributary mouths, thereby modulating the likelihood of TJF construction or preservation. Conversely, high disturbance (>50%) may suppress fan formation by confining channels or limiting sediment supply, while low-disturbance basins maintain more efficient sediment evacuation. In minimally disturbed catchments, intact riparian corridors and unmodified planforms typically sustain natural connectivity and limit opportunities for local fan development.

These results agree with recent work showing that human interventions can modify geomorphic connectivity by influencing contributing areas, floodplain width, and confluence hydraulics [

15,

66]. In the Chaudière system, such disturbance likely contributes to local deviations from the morphometric trends highlighted by PCA, CART, and LDA. These non-linearities help explain why morphometric models display moderate accuracy despite clear underlying patterns.

5.4. Hydrogeomorphic Implications and Conceptual Analysis

The combined morphometric, hydroclimatic, and anthropogenic patterns identified in this study indicate that TJFs function as localized sediment-storage zones responding to basin-scale geometry and episodic forcing. Their position at confluence nodes allows them to modulate downstream sediment delivery, lateral channel behaviour, and floodplain adjustment [

3,

12,

25,

62].

Recent flood events (2011, 2002) confirm that several TJFs remain hydraulically active, undergoing deposition or reworking during intense rainfall events [

39,

40,

41]. These basin-wide events mobilize sediment across large portions of the watershed and tend to reactivate the larger TJFs connected to higher-order tributaries. In contrast, short-duration convective storms produce highly localized floods in small, steep tributaries, generating coarse sediment pulses that can exceed mainstem discharge at the moment of impact. These local events are particularly effective at constructing or reworking smaller TJFs whose contributing areas fall within the intermediate energy domain identified by the morphometric analyses.

TJFs also align with broader concepts of sediment connectivity, functioning as partial buffers within basin-scale cascades, storing sediment during low-energy intervals and releasing it during high-magnitude floods [

13,

14,

66]. Their granulometric signatures, dominated by gravel and cobble fractions, further indicate their construction by episodic, high-energy flows rather than sustained background transport. This dual role shows that TJFs act both as archives of past events and as active agents shaping modern sediment redistribution.

Overall, the Chaudière River provides a representative example of how structurally controlled cold–temperate drainage networks express varying degrees of connectivity at confluence nodes. Although morphometric thresholds delineate the general conditions under which TJFs form, their reactivation strongly depends on the combined effects of basin-wide hydrological forcing and localized, tributary-scale floods, as well as the mediating influence of anthropogenic disturbance. Recognizing this interplay is essential for predictive fluvial geomorphology, where the propensity for TJF formation or reactivation emerges from the interactions between inherent basin-scale morphometric controls and short-term, event-driven forcing.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the factors controlling the occurrence and spatial distribution of TJFs along the Chaudière River by combining morphometric indices, field validation, and multivariate statistical analyses (PCA, CART, LDA). The results highlight a consistent suite of basin-scale predictors—relief, drainage density, contributing area, and slope–area coupling—that delimit an intermediate morphometric domain favourable to TJF formation. Within this range, sediment supply and transport capacity tend to equilibrate, promoting partial geomorphic coupling at confluence nodes. Agreement across PCA, CART, and LDA demonstrates that TJFs emerge from broad and reproductible morphometric conditions rather than sharply defined thresholds. Model performance remains moderate because morphometric structure alone cannot capture substrate heterogeneity, localized confinement, or event-scale hydrological forcing. In particular, the absence of explicit substrate information likely contributes to this unexplained variability, as lithological and material properties exert strong controls on sediment availability and transport thresholds. These findings underscore that TJF formation in humid postglacial environments reflects the interaction of inherited basin geometry with threshold-exceeding hydroclimatic events, rather than strict morphometric control.

Anthropogenic disturbance also influences TJF occurrence in context-dependent ways. Moderate disturbance levels coincide with higher TJF frequencies, whereas extensive modification tends to reduce depositional potential by constraining floodplain space or altering sediment-routing pathways. These patterns show that land-use alteration can either amplify or suppress morphometric predispositions, generating hybrid connectivity configurations characteristic of inhabited cold-region basins. Such interactions highlight the importance of integrating land-use dynamics into connectivity assessments, especially in regions experiencing increased hydroclimatic variability.

At the system scale, TJFs function as localized nodes of sediment storage and reactivation, modulating sediment transfer between upland sources and downstream floodplains. Their intermittent activity during recent flood events confirms their role as sensitive indicators of hydrogeomorphic variability in cold–temperate, postglacial landscapes. The Chaudière River thus provides a representative case showing how intermediate energy tributaries within structurally segmented basins can produce disproportionate geomorphic responses when morphometric predispositions align with threshold-exceeding hydrological events.

Beyond their geomorphic significance, TJF occurrence and grain-size characteristics provide a useful indicator of localized flood and sediment hazards. Because these landforms are activated primarily during threshold-exceeding events, confluences exhibiting the intermediate morphometric configurations identified in this study, particularly those combining moderate slopes, drainage areas of 20–40 km2, and low to intermediate drainage densities, represent areas where sediment-charged floods may rapidly alter channel capacity or induce short-term aggradation during extreme rainfall or rain-on-snow events. These responses can have direct implications for infrastructures, agricultural land, and floodplain management in cold–temperate basins. Incorporating TJF mapping and morphometric thresholds into river-management frameworks could therefore improve the identification of confluence-scale hazard zones and support more proactive responses to future high-magnitude events.

Future work should integrate morphometric approaches with temporal monitoring, such as repeated LiDAR surveys, sediment stratigraphy, and hydrological modelling, to quantify rates of TJF reactivation and sediment export. Applying similar multivariate frameworks to other cold-region basins will help validate the indicative morphometric ranges identified here and advance our understanding of connectivity dynamics under evolving hydroclimatic and anthropogenic pressures. Incorporating sedimentary architecture, substrate variability, and flood-frequency analyses will be essential for advancing from indicative morphometric prediction to more process-based, predictive geomorphology in fan-dominated systems.