Abstract

Groundwater quantity and quality are under pressure due to massive urbanization and intensive agriculture (irrigated crop land and livestock production) which threaten its sustainability as well as dependent ecosystems. This article explores the (i) environmental aspects of human activities that contribute to groundwater depletion and contamination, and (ii) actions that could be implemented into integrated planning for water resources to reduce groundwater vulnerability. A literature review was conducted in conjunction with the application of the DPSIR framework to identify critical factors (environmental aspects and impacts) that threaten groundwater sustainability and propose the best management practices aligned with sustainable development goal (SDG) 6. The DPSIR framework is useful in synthesizing threats to GW and for recommendations on proactive actions to overcome them and achieve sustainability.

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

Water resources are currently under serious pressure worldwide; as a result, groundwater (GW) plays an increasingly important role in complementing the available surface water [1,2,3,4], and water-stress forecasts suggest extreme scarcity mainly in parts of Africa, the Middle East, Asia, USA, and Australia by 2040 [5]. The situation is of major concern in rapidly urbanized mega cities, and the main challenges comprise water security, demand management, conservation (quantity and quality), equity, the water and energy nexus, and minimum daily consumption [6,7,8]. For instance, in the United States of America (USA), GW use increased by 8.3% while surface water use decreased by 13.9% in the period of 2010 to 2015 (US Geological Survey, 2014, 2018 [9,10]). Currently, GW is the most extracted (982 km3/year) raw material on the earth [11]. Conversely, the increased vulnerability of GW quality is among the major environmental issues concerning researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers [12,13,14]. Land-use change and pollution already threaten GW sustainability all over the world. For instance, the intensification of irrigated agriculture (e.g., nitrate contamination frequently exceeds the threshold of 50 mg/L set by the standards of the World Health Organization—WHO—for drinking water) [15] and wastewater treatment systems [13] engenders negative environmental impacts on GW quality. The situation is critical, since approximately 50% of habitable land is currently used for agriculture, with 77% of this portion used for livestock production and 23% for crops [16]. It deserves to be recognized as a major concern, because GW contributes to flow in many water courses (and vice versa; see [17]) and has also a strong influence on river and wetland habitats for plants and animals [12] and represents a relevant share of the water supply [12,18,19,20] used mainly for irrigation purposes (>50% in USA [12]; 70% is the world average [21], with 90% in India [22] and 93% in Morocco [18]). Indeed, various studies suggest that GW will face increasing pressure in the near future if human production [21] and behavior [19] continue along current trajectories. Agriculture uses 70% of global freshwater withdrawals [21,23] and this high share defines the GW irrigation economy on which world food security depends [24]. The Food Agricultural Organization (FAO) forecasted that irrigated food production will increase over 50% by 2050, which might increase irrigation water by only 10% in an optimistic scenario (i.e., under improvements in irrigation techniques and crop yield) [21]). Hence, sustainability demands the consideration of quality, quantity (constrained by land-use climate change), and its impact on dependent ecosystems [12,25,26]. Therefore, it is an essential resource that requires integrated planning to be appropriately protected [18,27]. Fortunately, stakeholder awareness is emerging in different areas, facilitating proactive policies (e.g., shifts in agricultural practices, improvements in land-use planning) that are mandatory to prevent and reduce threats to water security [28,29], food security [20,21] and global biodiversity [30].

The key issue of this work is that effective GW planning and conservation measures are of critical importance because global demophoric growth (increases in population + industrial production) is projected to increase, with population set to increase by 4 billion people over the 21st century (as forecasted by the United Nations; see [31]).

1.2. Objective and Research Question

Bearing the above concern in mind, this work aims to explore current threats to GW sustainability and their drivers and recommend what ought to be carried out to enhance GW planning and management from the viewpoint of sustainability (i.e., continuously minimize or prevent negative impacts). The objective of this work reflects the sustainable development goal SDG 6 (to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all) as stated by the United Nations Development Programme [32]. The research question to be answered is as follows: considering the driving forces inherent to human activities, what responses (adaptive actions) are required for the sustainable use of GW?

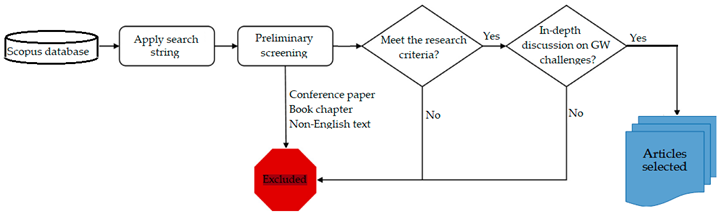

2. Methods: The Road to Identify Threats and Preventive Measures

To fulfill the work purposes the research approach was based in a literature review—combining relevant topics such as GW sustainability, land-use planning, strategic environmental assessment, adaptation to climate change, demophoric growth, and DPSIR (Driver–Pressure–State–Impact–Response) framework—to addresses GW threats and challenges, as well as recommend adaptive actions to prevent mismanagement. First, a literature review based on articles published in leading journals and European Directives was conducted to characterize the state-of-the-art concerning GW availability, usage, depletion, recharge, pollution, and protection according to best management practices (as depicted in Table 1). Secondly, DPSIR framework was used to contextualize the problem and concisely identify the Drivers (or driving forces: economic sectors, human activities), Pressure (emissions, waste, discharge), State (physical, chemical, and biological), and Impact ((eco)systems, human health, and functions) to derive adequate Response (adaptive actions, prioritization, target setting, indicators) that will contribute to enhancing GW planning and sustainable management (see [33]).

Table 1.

Search strategy on database to retrieve relevant articles.

This framework originated in 1979 as Stress–Response (S-R). Thereafter, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) proposed Pressure–State–Response (P-S-R), which evolved into DPSIR as proposed by the European Environmental Agency [34] and has been consolidated from then on [35,36,37]. The use of this framework assumes that socio-economic development causes Pressure on GW, which imposes changes on its State (quality and quantity).

As a result, impacts regarding water scarcity (due to overexploitation) and risk to human health (due to contamination) arise. Such impacts demand responses that can include adaptive actions—either structural or non-structural actions. This set of responses is of the utmost importance because it must comply with the sustainable development goals and, consequently, all the features of the response must satisfy the following five principles: (i) environmentally sustainable, (ii) technologically feasible, (iii) economically viable, (iv) socially acceptable, and (v) legally permissible.

3. Main Findings Linked to SDG 6

3.1. Human-Driven Groundwater Vulnerability

The use of GW as a complimentary means of water supply is essential because surface water resources are becoming scarce, influencing the socio-economic development of a region [38]. There are several countries/territories that already have a domestic water sector 100% dependent upon GW (e.g., the following nine: Bahrain, Malta, Montenegro, Oman, Qatar, Libya, Croatia, Saudi Arabia, and Mongolia), as reported by Margat and van der Gun [11]. Therefore, determining the sustainable discharge of water extraction (i.e., the optimal specific discharge measured as gallon extracted/second/meter of aquifer thickness) requires the quantification of GW recharge from rainfall and streamflow (Table 2) and is of critical importance for GW development projects since it prevents overexploitation.

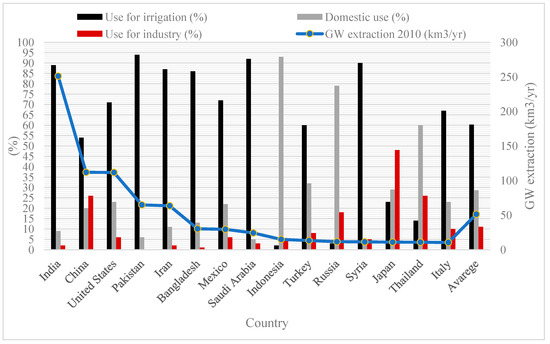

GW resources (e.g., the top three countries responsible for GW extraction are India, China, and USA, see Figure 1) have been extracted primarily to satisfy irrigation demand [11]. Saha et al. [22] stressed that the main GW sources in India are experiencing excessive withdrawal in comparison with their annual replenishment, which has caused overexploitation, obliterating the natural GW regime. This scenario is also observed in many other places in the world, such as Mexico City, Bangkok, North China Plain, Spain, and Los Angeles [1,39]. In addition, the geogenical (not a focus of the current study) and anthropogenical contamination of GW also threaten its sustainability [22,27]. The risk is higher in areas where urban water supply is dependent on GW, as in the case of the nine aforementioned countries/territories and in other regions that use GW to satisfy their drinking-water demand [12] such as, for instance, Dhaka City in Bangladesh [7], Europe (e.g., Denmark, Austria, Switzerland, Italy; see [40]), and in many areas of the USA where it is the only source for rural communities, with a notable proportion in western regions (e.g., Los Angeles; see [41]).

Figure 1.

The world nations responsible for extracting the most GW. Source: author’s elaboration based on Margat and van der Gun [11]. Among the countries represented, Saudi Arabia has the largest GW share (95%) in terms of total freshwater withdrawal.

The overexploitation of GW in the countries included in Figure 1 is causing land subsidence. Taking some countries as an example, these indicators are of major concern, since (i) Mexico City in Mexico [42], (ii) Tehran Basin in Iran [43], and (iii) Hengshui City in China [44] are experiencing, respectively, 300, 250, and 141 mm/year of land subsidence. Among the problems caused by land subsidence, there is the instability of surface-built environments (e.g., building, road) [45].

Table 2.

Indicators of pressure and state related to groundwater.

Table 2.

Indicators of pressure and state related to groundwater.

| Dimensions | Sustainability Goals | Main Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Decrease energy use for pumping Decrease pumping contribution to climate Change Reduce non-point source contribution to GW pollution Increase GW replenishment rate Evaluate GW productivity Assess GW availability and climate effects | Specific energy consumption (kWh/m3) GHG emission during operation (ton CO2e) Contaminant concentration (mg/L) Total renewable groundwater resources (m3/year) Renewable GW volume per capita (m3/hab.year) Groundwater abstraction and recharge index (%); index of total abstraction ratio to total exploitable GW (%); groundwater share index in water supply for all uses (%); index of change in groundwater storage (%); percent of basin area under natural vegetation (%) Water-level trend index in observation wells (%) Specific discharge (m3/s/m) Groundwater drought index Groundwater resources vulnerability index (%) Stress index (m3 of GW consumed/m3 Renewable GW) (%) Index of non-conventional water resources supply in the study area, relative to conventional water resources in the period studied. |

| Protect GW quality | Index of change in groundwater quality in a given period (yeari–yearn) (%); index of change in groundwater quality compared to short-term and long-term periods (%); electrical conductivity index | |

| Socio-economy | Increase GW system efficiency | Affordability or cost (USD/m3) Management expenditure index (%) Index of change in human development index (HDI) (%) |

Note: Source: the author’s elaboration, based on Samani [46].

3.2. Relevant Groundwater Indicators

The use of indicators is essential to quantify the Pressure (P) on GW and describe its State (S) when applying the DPSIR framework or any management assessment. A detailed list of relevant quantitative and qualitative indicators is given in Table 2.

4. DPSIR Framework: Identifying GW Factors of Vulnerability and Corrective/Preventive Actions

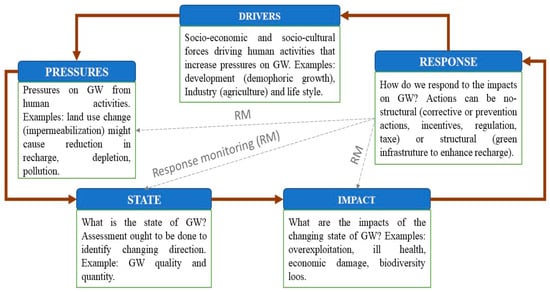

The main DPSIR components regarding GW sustainability were identified as those depicted concisely in Figure 2, with the main goal of providing practitioners and decision makers with useful information/indicators to reduce uncertainty in GW planning and management.

Figure 2.

The levels of the DPSIR framework applied to GW. The responses (actions to enhance GW planning and management) must be monitored to measure their effect on each component of the DPSIR framework.

The components of DPSIR applied to GW, as introduced in Figure 2, are developed considering the threats that have been reported in many studies across the last few decades (Table 3) and the expert opinion of the author on the subject. Thereafter, a synthetic relationship among DPSIR components—that represents an up-to-date and user-friendly guide—was developed to support integrated GW planning and management, as presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Main threats to groundwater quantity and quality indicators.

Table 4.

DPSIR can be applied to groundwater as follows: Drivers to GW consumption and pollution, Pressure on GW, State changes in GW, Impact upon GW quantity and quality, and Response to overcome threats and create conditions for sustainability.

5. Discussion and Recommendations

Groundwater is a critical component for socio-economic development worldwide. It provides water for domestic supply, industry and irrigation, and baseflow support to surface water (rivers and lakes) and wetlands. The European Water Framework Directive [65] was designed to cope with the well-know environmental aspects (Pressure) that include the discharge of nutrients, organic matter, water bodies, etc. At present, there are new environmental aspects, such as climate change and the discharge of contaminants of emerging concerns (pharmaceuticals, personal care products, microplastics, endocrine disruptors, and industrial chemicals), that threaten GW [55].

In this study, the Drivers⟶Pressure⟶State⟶Impact upon GW (quality and quantity) were identified and analyzed to derive Responses to guide GW sustainability. The way the causal relationships between DPSIR components are clearly presented differ in this study from the previous one and highlight the GW issues that might impair SGD 6 and the inherent adaptive measures.

The Drivers (D) of change in the GW State (S) are related to the pattern of urban (e.g., human concentration with heavy utilization of the resources, waste production, …), and agricultural settings as well as the dense concentration of multiple landscape changes that impact GW quantity (including land subsidence that impairs aquifer transmissivity by reducing its thickness and void connectivity) and quality [44,55]. The effects of climate change are another driver threatening the GW system [48].

Some studies that dealt with DPSIR framework in urban areas found Pressures and Response (P-R) to have the greatest effects on system resilience [66,67]. Although this study did not involve performing a quantitative analysis, P-R seems to be the two components of major concern when promoting GW sustainability. The issue must be posed as the following: what should be done to mitigate Pressure on (GW quantity and quality)? Some concise answers/measures (Responses) are provided in Table 4, and their effectiveness must be assessed through long-term planning and monitoring (Response monitoring—RM, Figure 2). Additionally, some of the adaptive actions are expanded on below:

- ♦

- An estimation of the sustainable yield of the aquifers to maintain a suitable future supply of water. Aquifer transmissivity and natural recharge must be characterized to allow for the establishment of sustainable yield. The pressure of population and industry growth combined with climate change and leakage in water-supply systems are contributing to GW overexploitation in order to satisfy the increasing demand in many regions [7,48,50,52]. Therefore, efforts must be made to establish a sustainable yield for each aquifer according to their replenishment [49,51].

- ♦

- An assessment of the effects of pumping on seasonal fluctuations in GW levels near sensible ecosystems (e.g., lake, wetland), and on springs. The estimation of changes in aquifer storage is difficult due to the lack of investment in data gathering, but it is of utmost importance in defining the pumping schedule and intensity to prevent ecosystem disturbance [44,46] and guarantee sustainable yield [7] in the context of the food–energy–water nexus [20].

- ♦

- An assessment of the spatiotemporal effects of anthropogenic non-point pollution (from irrigated agriculture and livestock production) on GW quality attributes (e.g., physico-chemical, bacteriological). In relation to this matter, Sarah et al. [53] contributed to the quantification of the volume of contaminated GW and the GW virtually lost due to contamination. Another example is the European Nitrate Directive that requires the establishment of Nitrate-Vulnerable Zones, i.e., areas where agriculture was likely to result in nitrate concentrations of 50 mg/L or above in water bodies [66,68].

- ♦

- The monitoring of piezometric pressure and an analysis of historical fluctuations in GW levels to understand the impact of land-use changes, as a consequence of demophoric growth that impairs GW replenishment, contributes to generate potential contaminants, and might cause land subsidence [20,44,66].

- ♦

- An assessment of the risk of salt intrusion (SI) to constrain the exploitation of aquifers to a minimum safe level of water. The risk of SI increases with the possibility of sea-level rise (climate change effect) and land subsidence [62].

Regarding DPSIR, some authors highlighted its ability to capture the key relationships in environmental management as the main strength [69], and others stressed the discrepancies in the application of DPSIR [70]. For example, land-use change is a Driver for Spangenberg [71] and Zaldívar et al. [72], while Haase and Nuissi [73] and Omann et al. [74] considered it a Pressure. This misuse of DPSIR occurs in several studies (see [70]), meaning that this work also contributes to preventing the misuse of DPSIR in the GW sector.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundacão Araucária grant number 111/2022, and the APC was funded by the same organization.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Molle, F.; Berkoff, J. Cities vs. agriculture: A review of intersectoral water re-allocation. Nat. Resour. Forum 2009, 33, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, T.; Alley, W.M.; Allen, D.M.; Sophocleous, M.A.; Zhou, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; VanderSteen, J. Towards sustainable groundwater use: Setting long-term goals, backcasting, and managing adaptively. Ground Water 2011, 50, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Weber, K.; Padowski, J.; Flörke, M.; Schneider, C.; Green, P.A.; Gleeson, T.; Eckman, S.; Lehner, B.; Balk, D.; et al. Water on an urban planet: Urbanization and the reach of urban water infrastructure. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 27, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laccarino, M. Why there is water scarcity. AIMS Geosci. 2021, 7, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.A.; Ghannadi-Maragheh, M.; Torab-Mostaedi, M.; Torkaman, R.; Asadollahzadeh, M. A review on the water-energy nexus for drinking water production from humid air. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Report. The EU Water Framework Directive; European Commission Report: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfanuzzaman, M.; Atiq Rahman, A. Sustainable water demand management in the face of rapid urbanization and ground water depletion for sociale-cological resilience building. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 10, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Lee, C.-M. Designing an optimal water supply portfolio for Taiwan under the impact of climate change: Case study of the Penghu area. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maupin, M.A.; Kenny, J.F.; Hutson, S.S.; Lovelace, J.K.; Barber, N.L.; Linsey, K.S. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2010; Circular 1405; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2014; 56p. [CrossRef]

- Dieter, C.A.; Maupin, M.A.; Caldwell, R.R.; Harris, M.A.; Ivahnenko, T.I.; Lovelace, J.K.; Barber, N.L.; Linsey, K.S. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2015; Circular 1441; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2018; 65p. [CrossRef]

- Margat, J.; van der Gun, J. Groundwater Around the World: A Geographic Synopsis; CRC Press/Balkema: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Twarakavi, N.K.C.; Kaluarachchi, J.J. Sustainability of ground water quality considering land use changes and public health risks. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 81, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, L.; Zwiener, C.; Zemann, M. Tracking artificial sweeteners and pharmaceuticals introduced into urban groundwater by leaking sewer networks. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 430, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Gojenko, B.; Yu, J.; Wei, L.; Luo, D.; Xiao, T. A review of water pollution arising from agriculture and mining activities in Central Asia: Facts, causes and effects. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The EU Nitrates Directive. 2010. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b2f78dad-e7cb-41c7-8f31-c71653f95631/language-en/format-PDF/source-100865477 (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Driscoll, M. Planetary Impacts of Food Production and Consumption; Alpro Foundation: Wevelgem, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Buerge, I.J.; Buser, H.-R.; Kahle, M.; Müller, M.D.; Poiger, T. Ubiquitous occurrence of the artificial sweetener acesulfame in the aquatic environment: An ideal chemical marker of domestic wastewater in groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4381–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetouani, S.; Sbaa, M.; Vanclooster, M.; Bendra, B. Assessing ground water quality in the irrigated plain of Triffa (north-east Morocco). Agric. Water Manag. 2008, 95, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogesteger, J.; Wester, P. Intensive groundwater use and (in) equity: Processes and governance challenges. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 51, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes-Santos, E.C.; Dias, R.A.; Balestieri, J.A.P. Groundwater and the water-food-energy nexus: The grants for water resources use and its importance and necessity of integrated management. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucatariu, C.A. The concept of (virtual) water in the food industry. In The Interaction of Food Industry and Environment; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Marwaha, S.; Mukherjee, A. Groundwater Resources and Sustainable Management Issues in India. In Clean and Sustainable Groundwater in India; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGWA. Facts About Global Groundwater Usage; Compiled by the Ground Water Association; NGVA: Westerville, OH, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.ngwa.org/what-is-groundwater/About-groundwater/facts-about-global-groundwater-usage (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Joshi, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Sinha, R.; Densmore, A.L.; Rai, S.P.; Shekhar, S.; Mason, P.J.; van Dijk, W. Strongly heterogeneous patterns of groundwater depletion in Northwestern India. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.; Bonsor, H.; Ahmed, K.; Burgess, W.G.; Basharat, M.; Calow, R.C.; Dixit, A.; Foster, S.S.D.; Gopal, K.; Lapworth, D.J.; et al. Groundwater quality and depletion in the Indo-Gangetic Basin mapped from in situ observations. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre, E.; Kristensen, L.S.; Engesgaard, P.; Højberg, A.L. Drivers and barriers for taking account of geological uncertainty in decision making for groundwater protection. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.-L.; Zhang, M.; He, L.-X.; Zou, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Li, B.-B.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Liu, C.; He, L.-Y.; Ying, G.-G. Contamination profile of antibiotic resistance genes in ground water in comparison with surface water. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigas, H. Water Security & the Global Water Agenda. A UN-Water Analytical Brief; Institute for Water, Environment and Health, United Nations University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, F.; Qin, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; He, Y. Spatiotemporal assessment of water security in China: An integrated supply-demand coupling model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmford, A.; Green, R.E.; Scharlemann, J.P.W. Sparing land for nature: Exploring the potential impact of changes in agricultural yield on the area needed for crop production. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poot, J.; Pawar, S. Is demography destiny? Urban population change and economic vitality of future cities. J. Urban Manag. 2013, 2, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. The Sustainable Development Goals in Actions. 2017. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Kristensen, P. The DPSIR framework. In Paper Presented at the 27–29 September 2004 Workshop on a Comprehensive/Detailed Assessment of the Vulnerability of Water Resources to Environmental Change in Africa Using River Basin Approach; UNEP Headquarters: Nairobi, Kenya, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Europe’s Environment: The Dobris Assessment; European Environmental Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, J.P.; Burdon, D.; Elliott, M.; Gregory, A.J. Management of the marine environment: Integrating ecosystem services and societal benefits with the DPSIR framework in a systems approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelble, C.R.; Loomis, D.K.; Lovelace, S.; Nuttle, W.K.; Ortner, P.B.; Fletcher, P.; Boyer, J.N. The EBM-DPSER Conceptual Model: Integrating Ecosystem Services into the DPSIR Framework. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Higgins, T.; Farmer, A.; Daskalov, G.; Knudsen, S.; Mee, L. Achieving good environmental status in the Black Sea: Scale mismatches in environmental management. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andualem, T.G.; Demeke, G.G.; Ahmed, I.; Dar, M.A.; Yibeltal, M. Groundwater recharge estimation using empirical methods from rainfall and streamflow records. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 37, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbach-Hertig, W.; Gleeson, T. Regional strategies for the accelerating global problem of groundwater depletion. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, R. Lessons learnt from the impact of the neglected role of groundwater in Spain’s water policy. Water Resour. Perspect. Eval. Manag. Policy 2003, 50, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.L.; Kenway, S.J.; Lant, P.A. Energy use for water provision in cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmanoğlu, B.; Dixon, T.H.; Wdowinski, S.; Cabral-Cano, E.; Jiang, Y. Mexico City subsidence observed with persistent scatterer InSAR. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2011, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, D.L.; Burbey, T.J. Review: Regional land subsidence accompanying groundwater extraction. Hydrogeol. J. 2011, 19, 1459–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Shen, Q.; Shum, C.; Gao, F.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H. TS-InSAR assessment of groundwater overexploitation-land subsidence linkage: Hengshui case study. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 60, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Shi, X.; Luo, G.; Hellwich, O.; Ma, X.; Shang, M.; Wang, Y.; Ochege, F.U. Ground subsidence and disaster risk induced by groundwater overexploitation: A comprehensive assessment from arid oasis regions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 119, 105328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, S. Assessment of groundwater sustainability and management plan formulations through the integration of hydrogeological, environmental, social, economic and policy indices. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.L.; Lawrence, A.R.L.; Chilton, P.J.C.; Adams, B.; Calow, R.C.; Klinck, B.A. Groundwater and Its Susceptibility to Degradation: A Global Assessment of the Problem and Options for Management; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2003; 126p, Available online: https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/19395/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Stuart, M.E.; Gooddy, D.C.; Bloomfield, J.P.; Williams, A.T. A review of the impact of climate change on future nitrate concentrations in groundwater of the UK. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 2859–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, Y.; Wisser, D.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Global modeling of withdrawal, allocation and consumptive use of surface water and groundwater resources. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2014, 5, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, J. The global groundwater crisis. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.F.; Caineta, J.; Nanteza, J. Global assessment of groundwater sustainability based on storage anomalies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.F.; Famiglietti, J.S. Identifying Climate-Induced Groundwater Depletion in GRACE Observations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, S.; Ahmed, S.; Violette, S.; de Marsily, G. Groundwater sustainability challenges revealed by quantification of contaminated groundwater volume and aquifer depletion in hard rock aquifer systems. J. Hydrol. 2021, 597, 126286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannibal, B.; Portney, K. The impact of water scarcity on support for hydraulic fracturing regulation: A water-energy nexus study. Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, X.; Jiang, W.; Xi, Y.; Li, S. Comprehensive review of emerging contaminants: Detection technologies, environmental impact, and management strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-Y.; Zhao, J.-L.; Liu, Y.-S.; Liu, W.-R.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Yao, L.; Hu, L.-X.; Zhang, J.-N.; Jiang, Y.-X.; Ying, G.-G. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) and artificial sweeteners (ASs) in surface and ground waters and their application as indication of wastewater contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.G.; Eberts, S.M.; Kauffman, L.J. Using Cl/Br ratios and other indicators to assess potential impacts on groundwater quality from septic systems: A review and examples from principal aquifers in the United States. J. Hydrol. 2011, 397, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Bhowmick, S.; Chatterjee, D.; Figoli, A.; van der Bruggen, B. Remediation of inorganic arsenic in groundwater for safe water supply: A critical assessment of technological solutions. Chemosphere 2013, 92, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-L.; Li, H.; Zhou, X.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Su, J.-Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, F.-Y. An underappreciated hotspot of antibiotic resistance: The groundwater near the municipal solid waste landfill. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.-L.; An, X.-L.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Su, J.-Q.; Cui, L. Do manure-borne or indigenous soil microorganisms influence the spread of antibiotic resistance genes in manured soil? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 114, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.J.; Anderson, R. Potable reuse: Experiences in Australia. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 2, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, N.; Vuillaume, J.-F.; Purnama, I.L.S. Salt intrusion in coastal and lowland areas of Semarang City. J. Hydrol. 2013, 494, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gago-Ferrero, P.; Gao, Q.; Ahrens, L.; Blum, K.; Rostvall, A.; Björlenius, B.; Andersson, P.L.; Wiberg, K.; Haglund, P.; et al. Evaluation of five filter media in column experiment on the removal of selected organic micropollutants and phosphorus from household wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 246, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Ku, C.Y.; Ni, C. Deep learning time-series modeling for assessing land subsidence under reduced groundwater use. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. In Official Journal of the European Communities; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2000; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Liu, Y. Evaluating the low-carbon development of urban China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 19, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Fang, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, X. Evaluating urban ecosystem resilience using the DPSIR framework and the ENA model: A case study of 35 cities in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikollaidis, N.P.; Poikane, S.; Bouraoui, F.; Herrero, F.S.; Free, G.; Varkitzi, I.; van de Bund, W.; Kelly, M.G. Comparison of eutrophication assessment for the Nitrates and Water Framework Directives: Impacts and opportunities for streamlined approaches. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, V.N.; Pinto, R.; Turner, R.K. Integrating ecological, economic and social aspects to generate useful management information under the EU Directives ‘ecosystem approach’. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2012, 68, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gari, S.R.; Newton, A.; Icely, J.D. A review of the application and evolution of the DPSIR framework with an emphasis on coastal social-ecological systems. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 103, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Biodiversity pressure and the driving forces behind. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaldívar, J.; Cardoso, A.; Viaroli, P.; Newton, A.; Wit, R.; Ibanez, C.; Reizopoulou, S.; Somma, F.; Razinkovas, A.; Basset, A.; et al. Eutrophication in transitional waters: An overview (JRC-EU). Transitional Waters Monogr. 2008, 1, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Nuissi, H. Does urban sprawl drive changes in the water balance and policy? The case of Leipzig (Germany) 1870–2003. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omann, I.; Stocker, A.; Jäger, J. Climate change as a threat to biodiversity: An application of the DPSIR approach. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).