Identifying Urban Pluvial Frequency Flooding Hotspots Using the Topographic Control Index and Remote Sensing Radar Images for Early Warning Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To show the applicability of Sentinel-1 radar imagery to generate a flood frequency map.

- To detect flood hot spots by integrating radar imagery and TCI evaluated depression areas.

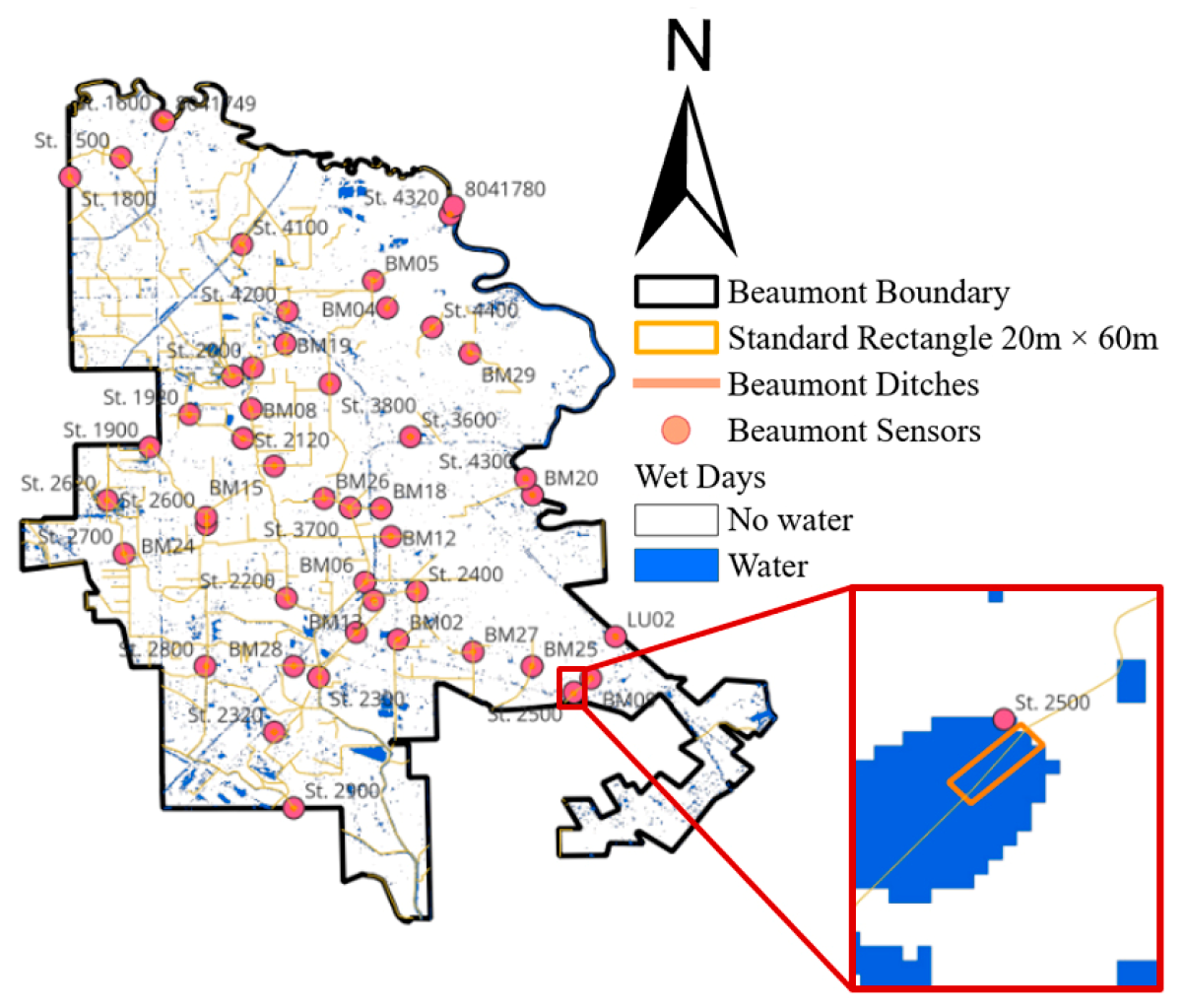

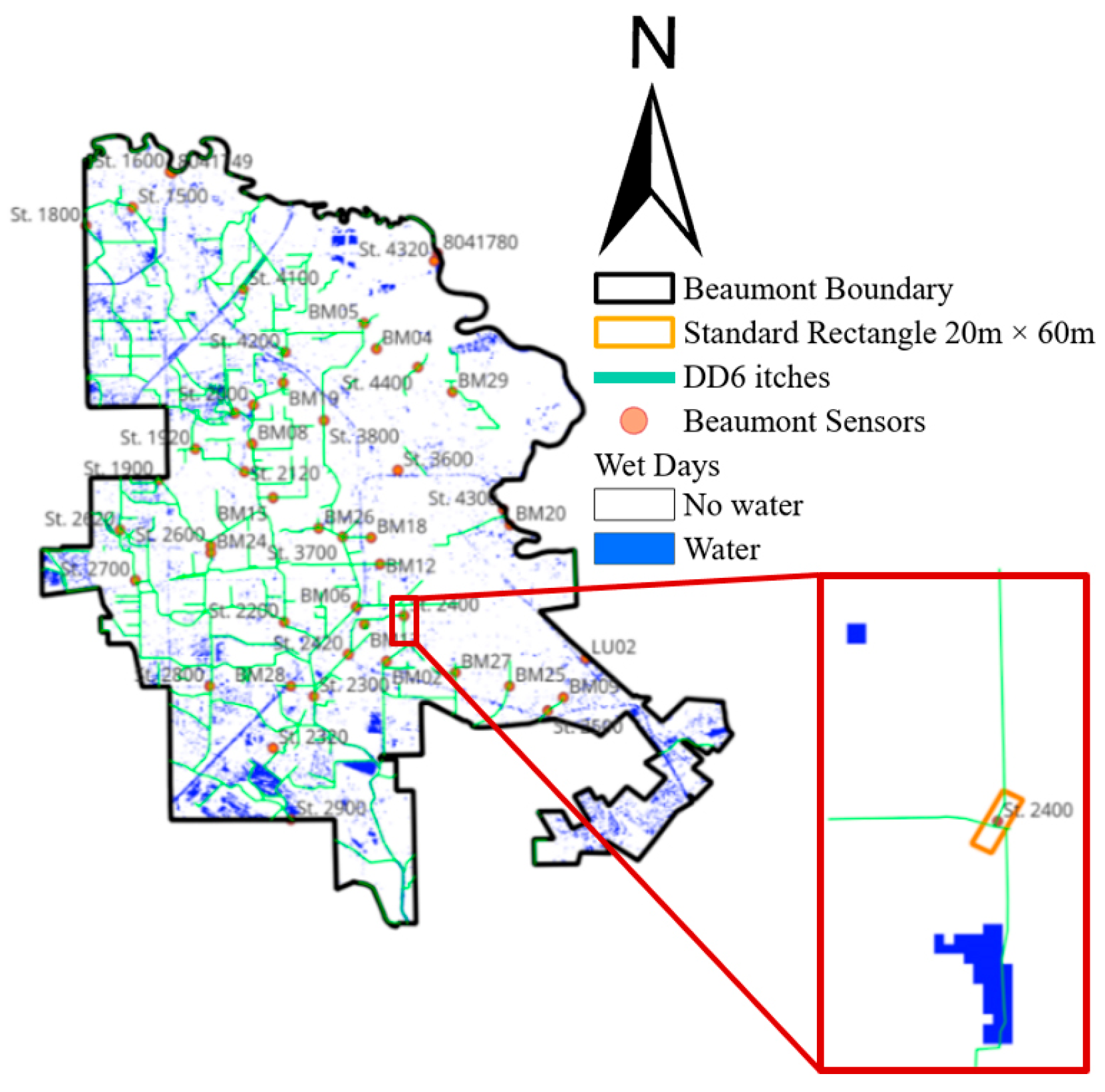

Study Area

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Topographic Analysis to Generate TCI

2.2. Radar Image Analysis for Water Pixel Detection

| Algorithm 1. Wet day selection algorithm | |

| Select rainy days from the precipitation dataset. Check whether those rainy days also show a water-level rise in ground flood monitoring sensors. | |

| |

| For the remaining days, check whether radar imagery is available. | |

| |

Ragdar Imagery Validation

- True Positive (TP): at least one water pixel is detected and the sensor stage > 0.

- False Positive (FP): water pixels are detected, but the sensor stage ≤ 0.

- False Negative (FN): no water pixels are detected, but the sensor stage > 0.

- True Negative (TN): no water pixels are detected, and the sensor stage ≤ 0.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- = number of water pixels detected in the radar image;

- = number of non-water pixels in the radar image.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Topographic Result

3.2. Flood Frequency Mapping Using Sentinel-1 Radar Imagery

- = peak (maximum) water level during the event;

- = water level at the radar image acquisition time.

| Wet Dates | Mean Delta T (h) | Mean % Change in Water Levels (%) | Number of Active Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 April 2016 | 10.11 | 10.95 | 11 |

| 20 January 2017 | 6.01 | 8.67 | 6 |

| 16 June 2021 | 4.37 | 13.79 | 16 |

| 10 July 2021 | 4.26 | 10.89 | 19 |

| 25 January 2023 | 6.31 | 38.27 | 39 |

| 12 June 2024 | 2.99 | 17.03 | 38 |

3.2.1. Validation of Radar Imagery Using Sensors

3.2.2. Identification of Pluvial Nuisance Flooding Hotspots

3.3. Statistical Results

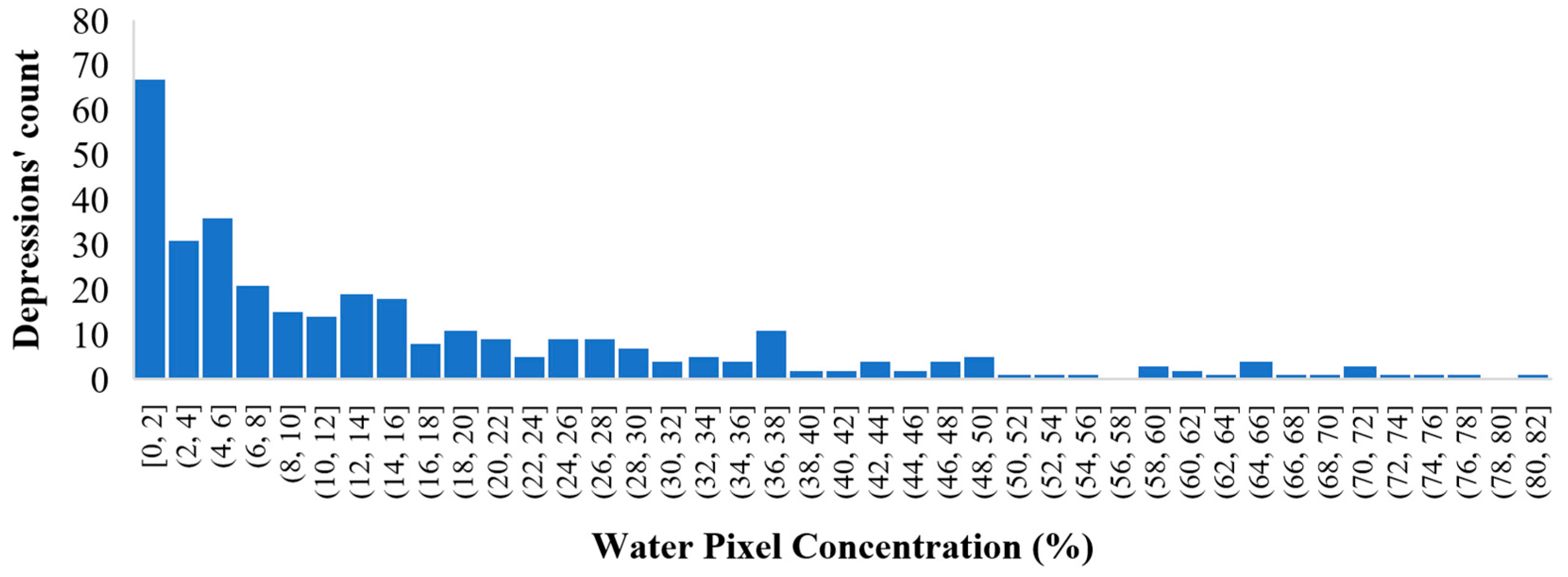

3.3.1. Comparison of the Flood Frequency Map with Depression

3.3.2. Comparison of Flood Frequency Map Within the Depressions (Friedman Test)

3.3.3. Comparison of Flood Frequency Map Inside and Outside the Depressions (Sign Test)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M. Natural disasters. In Our World in Data; Global Change Data Lab: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moftakhari, H.R.; AghaKouchak, A.; Sanders, B.F.; Matthew, R.A. Cumulative hazard: The case of nuisance flooding. Earths Future 2017, 5, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moftakhari, H.R.; AghaKouchak, A.; Sanders, B.F.; Allaire, M.; Matthew, R.A. What is nuisance flooding? Defining and monitoring an emerging challenge. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 4218–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, W.W.V.; Dusek, G.; Obeysekera, J.; Marra, J.J. Patterns and Projections of High Tide Flooding Along the US Coastline Using a Common Impact Threshold; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, A.J.; Miller, P.W.; Rohli, R.V.; Heavilin, J. Synoptic climatology of nuisance flooding along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts, USA. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 1281–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, W.; Park, J.; Marra, J.; Zervas, C.; Gill, S. Sea Level Rise and Nuisance Flood Frequency Changes Around the United States; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 7th ed.; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Justice, C.; Townshend, J.; Vermote, E.; Masuoka, E.; Wolfe, R.; Saleous, N.; Roy, D.; Morisette, J. An overview of MODIS Land data processing and product status. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, X.; Liu, D. Blending MODIS and Landsat images for urban flood mapping. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 3237–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjusree, P.; Prasanna Kumar, L.; Bhatt, C.M.; Rao, G.S.; Bhanumurthy, V. Optimization of threshold ranges for rapid flood inundation mapping by evaluating backscatter profiles of high incidence angle SAR images. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2012, 3, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossu, R.; Schoepfer, E.; Bally, P.; Fusco, L. Near real-time SAR-based processing to support flood monitoring. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2009, 4, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberstadler, R.; Hönsch, H.; Huth, D. Assessment of the mapping capabilities of ERS-1 SAR data for flood mapping: A case study in Germany. Hydrol. Process. 1997, 11, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizbahr, M.; Brake, N.; Arbabkhah, H.; Hariri Asli, H.; Woods, K. Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning and Geospatial-Sentinel-1 SAR Integration for Enhanced Early Warning Systems. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinis, S.; Rieke, C. Backscatter analysis using multi-temporal and multi-frequency SAR data in the context of flood mapping at River Saale, Germany. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 7732–7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, L. A depression-based index to represent topographic control in urban pluvial flooding. Water 2019, 11, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Huang, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. An integrated approach for urban pluvial flood risk assessment at catchment level. Water 2022, 14, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wahl, T.; Talke, S.A.; Jay, D.A.; Orton, P.M.; Liang, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, L. Evolving tides aggravate nuisance flooding along the US coastline. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau, U.S.C. Quick Facts: Beaumont City, Texas. In United States Population Estimates; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/beaumontcitytexas/PST045223#PST045223 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Asli, H.H.; Brake, N.; Kruger, J.; Haselbach, L.; Adesina, M. Field surveying data of low-cost networked flood sensors in southeast Texas. Data Brief 2023, 50, 109504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Huang, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Spatial heterogeneity of controlling factors’ impact on urban pluvial flooding in Cincinnati, US. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 125, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselbach, L.; Adesina, M.; Muppavarapu, N.; Wu, X. Spatially estimating flooding depths from damage reports. Nat. Hazards 2023, 117, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS. Neches River Basin LiDAR. 2017. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/neches-river-basin-lidar (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Alaska Satellite Facility. ASF Data Search (Vertex); Alaska Satellite Facility: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Space Agency. Sentinel Application Platform (SNAP), Version 9.1; European Space Agency: Paris, France, 2023.

- Guo, H. Spaceborne and airborne SAR for target detection and flood monitoring. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2000, 66, 611–617. [Google Scholar]

- McVittie, A. SENTINEL-1 Flood Mapping Tutorial; SkyWatch Space Applications Inc.: Kitchener, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://step.esa.int/docs/tutorials/tutorial_s1floodmapping.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Tanim, A.H.; McRae, C.B.; Tavakol-Davani, H.; Goharian, E. Flood detection in urban areas using satellite imagery and machine learning. Water 2022, 14, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.A.; DePuy, V. An Overview of Non-Parametric Tests in SAS: When, Why, and How; Paper TU04; Duke Clinical Research Institute: Durham, NC, USA, 2004; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, D.W. A note on the influence of outliers on parametric and nonparametric tests. J. Gen. Psychol. 1994, 121, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, C.J.; Zivney, T.L. The Specification and Power of the Sign Test in Event Study Hypothesis Tests Using Daily Stock Returns. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1992, 27, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Radar Image|Sensor Stage | Stage > 1 In | Stage < 1 In |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Sensors surrounded by water pixels in radar image | 90 (True Positive) | 0 (False Positive) |

| Number of Sensors not surrounded by water pixels in radar image | 37 (False Negative) | 2 (True Negative) |

| Performance Metrics | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Precision | 100 |

| Recall | 70.87 |

| F-1 score | 82.95 |

| Accuracy | 71.32 |

| Water Pixel Concentration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Water | Extremely Low | Low | Medium | High | Extremely High | ||

| TCI Class of Depression | Low | 10 | 11 | 11 | 21 (1) | 3 | 3 (1) |

| Medium | 21 | 98 | 62 (4) | 55 (5) | 19 (5) | 13 (7) | |

| High | 3 | 22 | 16 | 7 (3) | 0 | 3 (3) | |

| TCI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Flood frequency | Low | 16.54% | 12.04% | 11.29% |

| Medium | 4.50% | 2.94% | 4.04% | |

| High | 1.58% | 0.83% | 1.63% | |

| Null | 77.38% | 84.19% | 83.04% | |

| ||||

| Depressions/Pixels | Mean Water Pixel Concentration (%) | Median Water Pixel Concentration (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Inside depressions | 16.67 | 8.16 |

| Outside depressions | 8.66 | 8.66 |

| ||

| Description | Count |

|---|---|

| Total number of depressions | 378 |

| Number of positive differences | 186 |

| Number of negative differences | 192 |

| Number of ties | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakhrel, U.; Brake, N.; Feizbahr, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Hariri Asli, H.; Haselbach, L.; Macon, S.J. Identifying Urban Pluvial Frequency Flooding Hotspots Using the Topographic Control Index and Remote Sensing Radar Images for Early Warning Systems. Water 2025, 17, 3500. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243500

Bakhrel U, Brake N, Feizbahr M, Kim YJ, Hariri Asli H, Haselbach L, Macon SJ. Identifying Urban Pluvial Frequency Flooding Hotspots Using the Topographic Control Index and Remote Sensing Radar Images for Early Warning Systems. Water. 2025; 17(24):3500. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243500

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakhrel, Unique, Nicholas Brake, Mahdi Feizbahr, Yong Je Kim, Hossein Hariri Asli, Liv Haselbach, and Slater J. Macon. 2025. "Identifying Urban Pluvial Frequency Flooding Hotspots Using the Topographic Control Index and Remote Sensing Radar Images for Early Warning Systems" Water 17, no. 24: 3500. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243500

APA StyleBakhrel, U., Brake, N., Feizbahr, M., Kim, Y. J., Hariri Asli, H., Haselbach, L., & Macon, S. J. (2025). Identifying Urban Pluvial Frequency Flooding Hotspots Using the Topographic Control Index and Remote Sensing Radar Images for Early Warning Systems. Water, 17(24), 3500. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243500