Abstract

Dairy and livestock farms produce considerable amounts of wastewater, which could pose an environmental risk if not properly treated and discharged. Conventional treatment plants can represent an inadequate and costly solution in terms of operation and maintenance, especially for small and medium-sized farms. Thus, a valid and sustainable alternative can be provided by constructed wetland (CW). This paper analyzed the use of CW systems at different scales to treat dairy wastewater (DWW) and livestock wastewater (LWW) all around the world over the last thirty years. This systematic review identified 50 case studies reported in 50 publications from 22 countries: 20 CW for LWW and 30 for DWW. Per each type of WW, the analysis reported and compared the following: CW layout, type of substrates, vegetations planted, design parameters, removal efficiencies and management aspects. Gravel and sand are the most common substrates used in CW to treat both types of WW. Regarding vegetation, Phragmites australis is the most commonly used species in CWs treating LWW, whereas Typha spp. are the most frequently used in CWs treating DWW. Hybrid CW showed the highest removal performance for all parameters reported. This review can improve knowledge on CW, offering a technical and practical overview of the status of CW for treating LWW and DWW.

1. Introduction

The dairy industry generates large quantities of wastewater (WW), which is responsible for the most environmental impact in the sector. Every year, an estimated 4 to 11 million tons of dairy waste are generated and released into the environment worldwide, posing a significant threat to biodiversity [1]. Similarly, billions of liters of livestock wastewater (LWW) are inadequately managed and discharged, compounding environmental issues [2]. In addition, estimates suggest that the number of animals reared will double by 2050 [2]. This increase would significantly affect both the generation and disposal of wastewater from farms. Although reclaimed water enriched with fertilizers, nutrients and macro-nutrients can be used for agricultural irrigation [3], untreated LWW continues to pose substantial environmental risks. Consequently, effective treatment of LWW is essential to reduce pollution and limit eutrophication processes in aquatic ecosystems [4,5]. In this context, understanding the intrinsic characteristics of these effluents becomes essential for selecting appropriate treatment solutions.

Generally, the dairy wastewater (DWW) and LWW are characterized by high concentrations of Total Solids (TS), organic matter (BOD—biochemical oxygen demand; COD—chemical oxygen demand) and nutrients (TN—total nitrogen; NH4-N—ammonia; TP—total phosphorus) [6,7,8]. In particular, DWW is generated by production activities, washing, cleaning and disinfection of machinery [9]. Obviously, the qualitative and quantitative characteristics of these effluents depend on both the size and type of activity [9]. As reported in Ref. [10], these effluents show high concentrations of dissolved organic compounds (lactose, colloidal suspensions of proteins, mineral salts) and inorganic compounds (chlorine, phosphates, nitrogen); the latter result from the use of detergents and disinfectants during cleaning operations. LWW consists of urine, excrement residues, feed residues, wash water and civil water produced by livestock farms [11]. Generally, it concerns wastewater from swine (SW), cattle (CW) and poultry (PW).

Consequently, sustainable management of these wastewaters is crucial for environmental protection and water quality, as water scarcity is expected to increase in the coming years, due to pollution [12]. Nevertheless, the significant presence of pollutants in DWW and LWW leads to high operation and maintenance costs and energy requirements for effluent treatment [13,14]. This scenario highlights the need to evaluate existing treatment technologies and explore more efficient alternatives.

Typically, these WW are treated using conventional systems (CS), involving chemical, physical and biological processes (flotation, oxidation, precipitation, carbon adsorption, solvent extraction, ion exchange, membrane filtration, biodegradation, phytoremediation and electrochemistry) [15]. However, these systems often prove to be insufficient to mitigate environmental impacts due to inadequate management caused by high associated costs, which lead to low pollutant removal efficiencies [4]. A viable alternative could be nature-based solutions, such as constructed wetlands (CWs).

CWs, while performing the same function of CSs, are considered to be sustainable treatment systems in economic, environmental and energy terms [16]. Due to their low operating and maintenance costs (i.e., 1–2% of plant costs), CW systems are the most economical way to treat wastewater. These systems can be used to treat various types of WW, such as agricultural WW, industrial dairy WW, industrial tannery WW, industrial textile WW, pulp and paper industry WW, acid mine drainage WW, etc. [17]. CW treatment reduces the concentration of pollutants in the effluent discharged into surface water bodies. [18]; indeed, they are highly efficient in removing organic matter and TSS [17], as well as in reducing ammonia nitrogen and phosphorous [19].

CWs can be classified into two different categories: Free Water Surface Flow (FWSF) CWs and Sub-Surface Flow (SSF) CWs. In particular, SSF systems can be further classified as follows: Vertical Flow (VF) CW, Horizontal Flow (HF) CW, French Vertical Flow (FVF) CW and hybrid type CW [20]. The FWSFs are free-surface systems in which WW flows on the surface. These systems achieve an average removal efficiency of TSS, BOD and COD and N of 70–80%, 50–60% and 50–65%, respectively [21]. In HF systems, the effluent flows horizontally inside the unit. The system operates mainly under anaerobic conditions, triggering denitrification processes. HF systems are efficient in removing TSS, COD, BOD, nitrate nitrogen, phosphates and other pollutants [22,23]. In VF systems, WW is distributed over the surface through distribution pipes, percolates vertically through the substrate and is subsequently drained from the bottom by means of drainage pipes [24]. These systems operate under aerobic conditions, triggering nitrification processes and achieving a high removal efficiency of organic matter and other pollutants [17]. FVF CWs are two-stage vertical flow systems, arranged in parallel and operating in series. They have a removal efficiency that is similar to VF systems but save on construction costs [17]. Hybrid CWs are characterized by multi-stage treatment systems, i.e., a combination of HF and VF [25]. Hybrid CWs show higher removal efficiencies than other types of CWs. However, their performance varies depending on operational conditions (aerobic or anaerobic) and the characteristics of the WW [26,27,28].

Generally, SSF CWs are composed of appropriate filling media, which play a crucial role in the accumulation (e.g., organic matter and nutrients) and removal of pollutants (e.g., pathogens). Sand (permeable and with high purification efficiency) and gravel (permeable and with lower purification efficiency) are the most commonly used substrates [29].

Plants help prevent clogging of the substrate through root and rhizome development, or by the movement of plants due to the wind. Additionally, the root surface provides a favorable breeding ground for microorganisms [29]. The most commonly used plants are macrophytes (e.g., reed, rush, bulrush, etc.), with reeds being the most suitable due to their roots, which can extend more than 50 cm deep and are resistant to changes in water level and nutrient load [29]. Despite these advantages, CW systems are not without limitations.

Clogging and occlusion of distribution pipes are the most common issues in CW systems. Clogging is typically caused by the presence of TSS in the influent, biofilm development in the filling medium, precipitates and plant residues in the medium [30]. It consists of the obstruction of the filling medium due to the slow flow of treated wastewater [31].

Some disadvantages are related to maintenance costs, such as mowing and biomass removal as well as the appropriate disposal of (contaminated) vegetation [17]. There is also seasonality in removal efficiency (higher in summer than in winter) [32] and variability of treatment, depending on the pollutants in the effluent (not applicable to all compounds in the effluent) [33].

Although several studies have reported high removal efficiencies of CWs for DWW and LWW treatment, existing reviews have primarily addressed broad or general aspects of these systems. The present article provides an in-depth examination of the technical features of CWs that are specifically applied to DWW and LWW, thereby filling a relevant gap and updating the current knowledge base.

Accordingly, this review offers a more comprehensive and up-to-date perspective on DWW and LWW treatment, with a focus on the design, technical and management aspects of CWs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This review was written to provide a general and relevant overview of the treatment of dairy and livestock wastewater by constructed wetland systems. It includes the identification of the layout types, sizes, substrates and vegetation used, as well as the concentration and removal efficiencies of the main chemical and physical contaminants. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol [34] was used for this work. The PRISMA approach gives a precise, reproducible, scientific and transparent protocol [35].

2.2. Search and Research Sources

The first step involved searching through multidisciplinary and reliable databases, such as SCOPUS and Web of Science. Studies were identified using a search string with terms contained in the titles, abstracts and keywords. The research focused on the use of CW systems for the treatment of dairy and livestock WW from small and medium-sized cattle farms. The keywords used in the final string were as follows: “Constructed wetland” AND “Livestock wastewater” OR “Dairy wastewater” OR “Cheese wastewater” OR “milk wastewater” OR “cow wastewater” OR “cattle wastewater” OR “milkhouse wash water” OR “milk parlor” OR “dairy parlor”) AND “farm” OR “cattle farm” AND “removal efficiency”. The following string was used: (“Constructed wetland*”) AND (“Livestock wastewater*”) OR (“Dairy wastewater*”) OR (“Cheese wastewater*”) OR (“milk wastewater*”) OR (“cow wastewater*”) OR (“cattle wastewater*”) OR (“milkhouse wash water*”) OR (“milk parlor*”) OR (“dairy parlor*”) AND (“farm*”) OR (“cattle farm*”) AND (“removal efficiency*”). The same search query and criteria (e.g., year, document type, keywords and language) were applied to both search engines. The first keyword search produced 416 and 1508 matches on SCOPUS and Web of Science, respectively.

2.3. Screening and Eligibility Process

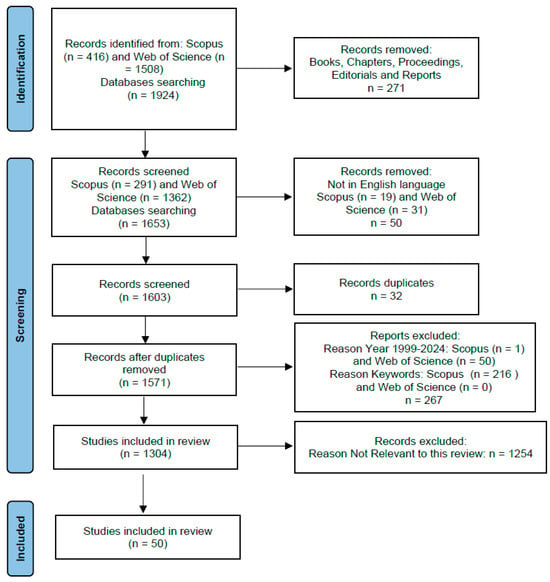

The next phase involved the selection of the relevant literature through the screening and eligibility process. In the second phase, during the screening phase, the primary exclusion criteria were applied—only published academic articles were included in this phase. The articles identified by SCOPUS and Web of Science were reduced from 1924 to 1653 records. At this point, only articles were considered; proceeding paper, conference papers, books, book chapters, early access, data papers and reviews were excluded. In the eligibility stage, non-English language papers were eliminated, excluding 50 documents, which reduced the number of papers from 1653 to 1603. Duplicates (32) were then removed, bringing the total from 1603 to 1571 articles. Finally, additional articles were excluded based on their relevance to this review, focusing on the year range (1999−2024) and keywords, resulting in the exclusion of 1521 papers. In the last phase, the included stage, a sample of 50 documents was selected to answer our research question. Obviously, these parameters are inherent parameters in all reviews; therefore, even although a systematic search was carried out, the primary studies could be biased. The flow chart shows the selection and exclusion criteria of scientific works (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing number of publications identified, screened and excluded, and their exclusion criteria.

2.4. Bibliometric Analysis

Based on the selected documents, the results were presented using bar charts and line charts with indicators. The graphs report the 50 selected works, grouped by trend in the number of publications over the years, articles by journal and articles by country.

In order to analyze the co-occurrence of keywords and visualize search trends, bibliometric mapping was performed using VOSviewer (v1.6.20).

3. Results and Discussions of the Literature Review

3.1. Preliminary Overview of Selected Articles

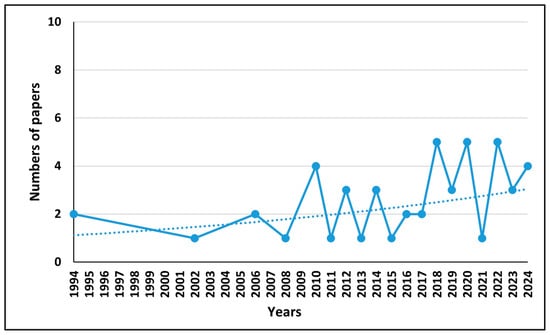

Figure 2 shows the trend in the scientific literature in relation to the period 1994−2024, indicating the number of articles published each year. In general, until 2006, the number of articles per year was rather limited. In fact, from 1994 to 2006, the average number of publications per year was less than that since 2008; the annual number of articles showed a slight exponential increase, demonstrating an increasing interest in this field. The highest number of publications was recorded between 2010 and 2024, peaking in 2018 with five publications.

Figure 2.

Trend in the number of publications over the years.

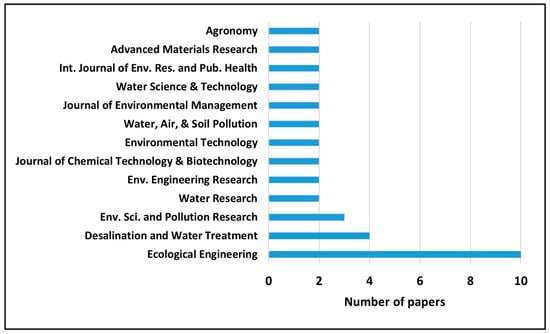

Figure 3 shows the journals with at least two articles. Journals with fewer publications are not included in the graph (Figure 3). The highest number of publications was recorded by Ecological Engineering with 10 articles, followed by Desalination and Water Treatment (4 articles) and Environmental Science and Pollution Research (3 articles), Water Research, Environmental Engineering Research, Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, Environmental Technology, Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, Journal of Environmental Management, Water Science & Technology, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Advanced Materials Research and Agronomy (2 articles), Innovation Engineering, Biosystems Engineering, Advances in Environmental Technology, Journal of Environmental Engineering, Water, Journal of Applied Life Sciences and Environment, Catena, Environmental Research, Bioresource Technology, and Agricultural Water Management (1 article).

Figure 3.

Number of papers per journal.

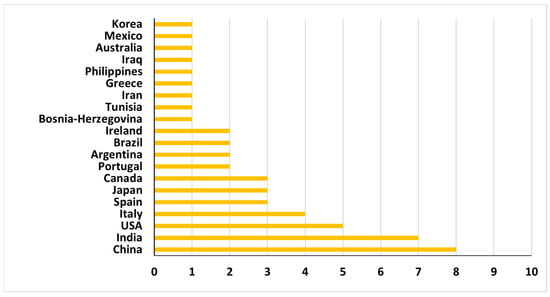

Regarding the area of interest, Figure 4 shows the number of publications per country. The country with the most articles is China (eight), followed by India (seven), the USA (five), Italy (four), Spain, Japan and Canada (three), Portugal, Argentina, Brazil and Ireland (two), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Tunisia, Iran, Greece, Philippines, Iraq, Australia, Mexico and Korea (one).

Figure 4.

Number of papers per country.

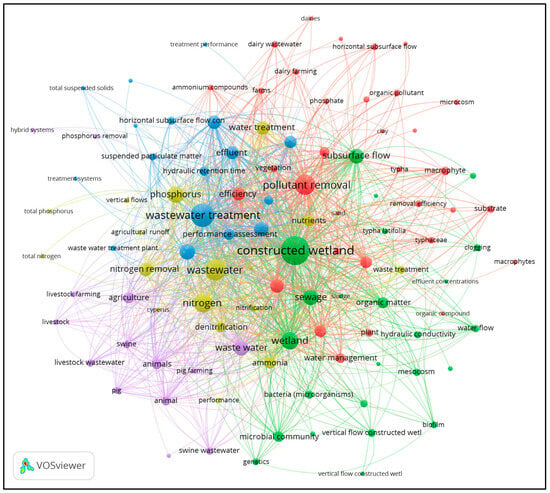

Bibliometric Analysis of the Themes

Using the VOSviewer software, a bibliometric map was created in order to visualize the network between the data. VOSviewer allows the visualization of bibliometric networks and co-occurrence links through keywords. The keywords in the titles and abstracts of the articles were analyzed according to their occurrence to generate an occurrence map of all the keywords used in the 1304 selected articles. The map of the most common keywords was created by selecting ‘co-occurrence’ as the kind of analysis, ‘all keywords’ as the unit of analysis and ‘five shared keywords’ as the minimum level.

Subsequently, VOSviewer transformed the data into a graphical format, classifying the common keywords into five main clusters in the network view. Greater importance and significance are highlighted by larger circles and map labels. Similarly, keywords of the same color belong to the same cluster (Figure 5). Specifically, the size of the circles corresponds to the frequency of the keywords, while the distance between them reflects their correlation. The colors red, green, blue, yellow and purple differentiate the clusters in the graphic map (Figure 5). All five clusters validate the search flows derived from the bibliographic matching.

Figure 5.

Keyword co-occurrence analysis map. The size of each node indicates the occurrence of the keyword in all 1304 publications. Red, cluster 1: dairy wastewater; Green, cluster 2: hydraulic characteristics; Blue, cluster 3: treatment performance; Purple, cluster 4: livestock wastewater.

The nodal results obtained from the bibliometric analysis help us to understand the similarity and pertinence of keywords and to identify potential gaps and insights. Five main clusters were created. The first cluster, comprising 33 elements, is represented in red. The second cluster, colored green, includes 23 elements. The third and fourth clusters, shown in yellow and blue, respectively, both contain 17 elements. Lastly, the fifth cluster, represented in purple, consists of 14 elements.

A keyword cloud was also generated to show the frequency and interrelationships of the most commonly occurring keywords in the papers selected for this research. “Constructed wetland”, “Wastewater treatment”, “Pollutant removal”, “Wastewater”, “Nitrogen”, “Phosphorus”, “Water treatment”, “Ammonia” and “Sewage” seem to be much-studied topics. “Constructed wetland” was the most frequent keyword, appearing 219 times, followed by “Wastewater treatment” with 144 occurrences, “Wastewater” with 111 occurrences and “Pollutant removal” with 110 occurrences. All other keywords scored lower.

Through keyword analysis and recurrence evaluation, five clusters of main search topics were identified (Figure 5).

The red cluster includes studies focused on the removal efficiency of the main pollutants, with particular reference to WW management from dairy farms, as well as the use of vegetation (macrophytes) and substrates (e.g., clay). The second cluster, colored green, includes documents concerning CW, with a focus on hydraulic characteristics (e.g., water flow), as well as the presence of organic matter and possible clogging problems. Additionally, this cluster highlights studies addressing the treatment of WW, with a particular focus on the main contaminants, such as phosphorus and nitrogen and their denitrification and nitrification processes. The blue cluster refers to treatment performance, focusing on plant configuration, unit type (e.g., horizontal sub-surface flow systems) and hydraulic retention time. Finally, the purple cluster concentrates on LWW, particularly from swine farms.

3.2. Wastewater Composition

This section describes the technical characteristics of CW systems for the treatment of LWW and DWW, post preliminary overview of the selected articles, and exclusively focused on the 50 case studies. Specifically, the characteristics of the raw WW, the type of substrates and vegetation used, plant species and configuration, as well as the flow rate, hydraulic loading rate (HLR) and hydraulic retention time (HRT) of the CW are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Minimum and maximum concentrations of physico-chemical parameters in dairy wastewater.

Table 2.

Characteristics of dairy wastewater treatment systems, based on about 30 sources. Removal efficiency (%) is related to the entire ww treatment system.

Table 2 and Table 3 show the characteristics of the raw WW entering the entire treatment system. Therefore, the removal efficiencies reported refer to the overall system.

Table 3.

Characteristics of livestock wastewater treatment systems, based on about 20 sources. Removal efficiency (%) is related to the entire ww system.

3.2.1. Dairy Wastewater (DWW) Characteristics

The various production processes in the dairy sector generate considerable volumes of wastewater [4]. Generally, the main waste produced is wastewater (sanitary, processing and cleaning), processing sludge and whey.

DWW is characterized by a high concentration of dissolved organic components (e.g., lactose, whey protein, minerals and fat) and washing products such as detergents and sanitizers [1]. In particular, lactose, casein, fat, organic matter and nutrients (N, P and K) are found in dairy sludge [74].

Typically, DWW has a high concentration of TSS, COD and BOD (Table 3). Usually, the COD concentration in dairy effluents is mainly influenced by the presence of milk, buttermilk or whey [75]. BOD reflects the amount of dissolved and suspended organic substances in the WW. Its aerobic removal requires suitable low-cost substrates (gravel/sand, etc.), microbial communities, and proper aeration on the CW bed surfaces [36]. TSS consist of suspended particles in the WW, which can increase BOD values and cause clogging of CW unit [76,77,78]. Their composition varies significantly, depending on activities and products [79].

For instance, Ref. [47] reports a DWW composition with 5060 mg/L of COD, 3020 mg/L of BOD and 3040 mg/L of TSS. In contrast, Ref. [40] documents a composition of influent with lower COD (2996 mg/L), BOD (1371 mg/L) and TSS content (746 mg/L). Similarly, Ref. [46] notes an influent composition with COD, BOD and SS contents of 3612, 1393 and 662 mg/L, respectively, whereas Ref. [38] reports nine times lower COD content (384 mg/L), almost seven times lower BOD content (215 mg/L) and three times lower SS content (250 mg/L). The high concentration of organic matter and TSS reported by [47] was probably caused by the raw whey content (20% whey) in the influent. Indeed, the undiluted influent had concentrations of 25,300 mg/L, 15,100 mg/L and 15,200 mg/L for COD, BOD and TSS, respectively. The much lower values reported by [38] can be explained by the composition of the influent, which included WW from the waiting room (after solid/liquid separation), the milking parlor and domestic WW.

Nutrients concentrations are as variable as those of organic matter and TSS. Nitrogen originating primarily from milk proteins can be present as organic form compounds (proteins, urea and nucleic acids) or as nitrates (NO3-N), nitrites (NO2-N) and ammonia (NH4-N). The total phosphorus consists of inorganic and organic phosphorus [38]. Additionally, washing and sanitizing operations increase phosphates: for example, through the use of phosphoric acid and phosphorous-containing detergents. These results highlight the chemical–physical variability of the main contaminants, depending on activities, farm type and seasons.

For instance, Ref. [49] reports an average TP concentration of 39 mg/L, similar to values report in [4,47], with TP concentrations of about 36 mg/L and 32 mg/L, respectively. Conversely, lower values were reported by [38,48], with average TP concentrations of 10 mg/L and 13 mg/L, respectively. Similar concentrations were observed by [13], ranging from 8 to 15 mg/L. Regarding NH4-N, the average concentrations observed in this review are highly variable, probably due to farm characteristics (e.g., number of animals), effluent pre-treatment and on-farm activity. Many studies report NH4-N values ranging from 50 mg/L to 70 mg/L, while others report lower values between 9 mg/L and 41 mg/L.

3.2.2. Livestock Wastewater Characteristics

The composition of livestock wastewater (LWW) varies significantly depending on its source: e.g., whether it is swine wastewater (SW), poultry wastewater (PW), or cattle wastewater (CW) [80].

In particular, 55% of the selected articles refer to SW. CW or similar wastewater (slaughterhouse WW, cattle manure, milk parlor wash water) was used in about 20% of the total. The remaining 25% is characterized by WW from different activities (e.g., sheep, pigs, cattle and horses). The LWW production worldwide is estimated at 6.01 × 107 tons [81].

Generally, WW generated by livestock activities contains excrement, excrement residues, urine, wash water and civil water. These WWs, mainly generated by washing water, are characterized by high concentrations of solids, organic matter, nutrients and coliforms [82] (Table 4). In addition, pharmaceuticals and metals are also present [11]; in fact, Zn and Cu are frequently used to reinforce the immune system of animals [83].

Table 4.

Minimum and maximum concentrations of physico-chemical parameters in livestock wastewater.

Thus, the environmental impact of LWW causes great concern among researchers and the public, due to the characteristics of the effluent [11].

TSS and organic matter (COD and BOD5) are two of the main constituents of LWW. In this review, the highest concentrations of COD and BOD5 of 8900 mg/L and 6200 mg/L, respectively, was reported in [8]. In contrast, Ref. [64] reports significantly lower values for COD (2500 mg/L) and BOD5 (1100 mg/L). This difference could be explained by the different number of pigs on the farm—5000 and 50, respectively—in [8,64]. Ref. [69] reports TSS concentrations of 13,200 mg/L, which is clearly higher than the value reported by [14] of 140 mg/L. This could be explained by the different characteristics of the effluents, which are certainly more concentrated in [69] (SW) and significantly more diluted in [14] (pig urine and wash water).

Other main contaminants in LWW are nutrients such as TN and TP. TN can be present in different forms: more precisely, in ammoniacal and nitric form. Regarding TN concentrations in the selected papers, average values are reported to be between 630 mg/L and 731 mg/L. Higher values were reported by [66,68], with concentrations equal to 1395 mg/L and 1600 mg/L, respectively. Among the studies reviewed, only 15% reported TN concentrations below 100 mg/L [60,71,72]. Generally, TP concentrations range from 5 mg/L to 36 mg/L [66,69]. Nevertheless, Refs. [11,67] report higher TP concentrations of 60 mg/L and 151 mg/L, respectively.

3.3. Plant System, Substrates and Vegetation

3.3.1. Pre-Treatment

DWW and LWW, due to their high content of TSS and organic matter compared to, e.g., domestic WW, need to undergo pre-treatment before being refined with CW [38].

Pre-treatment of DWW is indispensable, as its organic content is one of the main factors affecting the biodegradability coefficient [84,85]. As in conventional municipal wastewater treatment, these wastewaters undergo standard preliminary and primary operations. A preliminary treatment includes coarse screening, which removes large solids and provides an initial reduction in organic matter, and the use of degreasers, which reduce COD by capturing fat-rich fractions that would otherwise elevate the organic load of the influent. Primary treatment is performed through sedimentation, which significantly reduces TSS concentrations and, given the predominantly organic nature of these solids, also contributes to COD removal.

In this context, the implementation of appropriate pre-treatment steps becomes crucial for ensuring stable and efficient CW performance.

These preliminary and primary treatments significantly reduce the COD in WW and provide a more favorable environment for the metabolism of aerobic microorganisms in secondary treatments [86,87].

For instance, fats and oils, which are slow-degrading compounds, can cause problems in aeration and pumping systems. Additionally, the presence of grease may inhibit gas transfers, with negative repercussions on biological degradation [88].

As reported by [89], screening and/or water/oil separators are commonly employed as pretreatment methods. Furthermore, it is highlighted that over 65% of industries utilize an equalization tank to homogenize the flow and pollutant load during treatment. In the case of LWW, which is characterized by a higher solids content, preliminary and primary treatment are essential to prevent sludge accumulation. For example, anaerobic tanks equipped with filters or screens could be used in order to considerably reduce organic loads [90]. In fact, as reported in the literature, pretreatment could increase TSS and COD removal efficiencies by 90% and 50%, respectively [38].

Generally, all full-scale CWs include preliminary and/or primary treatment. Several case studies often included a sedimentation or settling tank, a degreaser and an Imhoff tank [38,43,46,48].

For example, Ref. [48] highlights how pre-treatment through a sedimentation tank, degreaser and two Imhoff tanks enabled efficient WW treatment through physical, chemical and biological processes. Ref. [39] carried out pre-treatment using floating technology to remove oils and fats from effluents, while TSS reduction was achieved using a precipitation device, which reduced TSS by 70%. Ref. [40] submitted WW to pre-treatment with thin aluminum grids, a grit chamber, a grease trap and finally, by a pond with optional aeration. In addition, in a study conducted by [52], a filter consisting of several layers of geonet was installed after the Imhoff tank to retain TSS. The treated WW in the pond had a COD/BOD5 ratio of 2.6 (±0.4), indicating an already biodegradable WW [91]. In a study on a pilot-scale system without pre-treatment, used an EAF steel slag filter at the outlet of CWs to remove TP [44].

3.3.2. Type, Layout and Global Distribution of Dairy CW

In terms of plant design, system type, layout and scale were considered. The scale of the system influences the pollutant removal efficiencies. Certainly, transitioning from a microcosm to a full-scale system increases the variables in the system, due to the shift from a controlled to a natural environment [92,93].

In this regard, studies conducted on ‘microcosm’ systems use small scales to understand biogeochemical processes (e.g., absorption, phytoremediation, microbial activity) in controlled environments [93,94]. In contrast, full-scale systems replicate the main processes in the natural environment. However, their main limitations are the large surface areas and high costs required for their implementation [92]. Mesocosms, by comparison, are more cost-effective systems for studying pollutant removal in wetlands. They provide useful predictions through treatment replicates and controls, enabling the study of wetland effectiveness in controlled, natural environments [92,95].

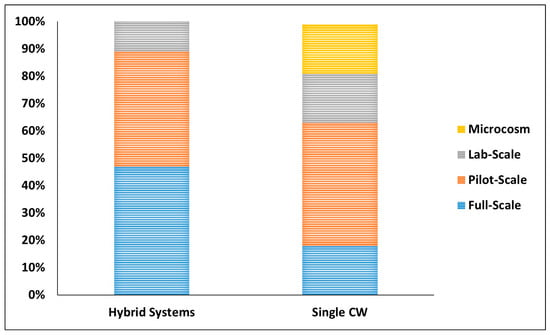

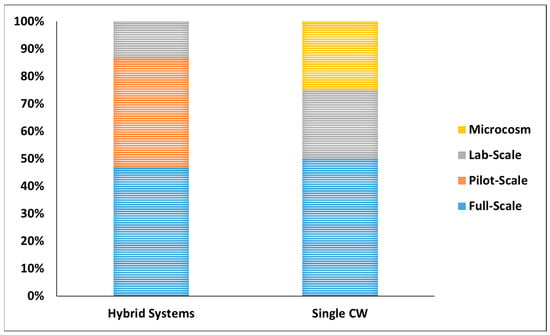

Regarding the systems shown in Figure 6, 63% are hybrid systems, while the remaining are single CW systems. Hybrid systems represent 47%, 42% and 11% of full-scale, pilot-scale and lab-scale systems, respectively. Among single CW systems, 45% are pilot-scale, 18% are full-scale, 18% are microcosm and 18% are lab-scale systems.

Figure 6.

Percentage distribution of different scales of CW systems examined for dairy wastewater treatment.

Generally, hybrid systems consist of at least one VF and one HF unit. Usually, the VF unit is used as the first stage of treatment, due to its efficiency in reducing TSS, organic matter and nitrification processes (owing to the increased presence of oxygen).

For example, Refs. [13,36] report systems with the following similar layout: VF–HF and VF–HF–VF system configuration, respectively. In both cases, comparable TSS removals were shown: 85–97% [13] and 92% [75]. Hybrid systems are also efficient in removing TP. Ref. [36] (VF-HF-VF) and Ref. [13] (VF-HF) report similar TP removal efficiencies of 86% and 72–87%, respectively. VF and HF used as single units, reduced the TP content in WW by 57% and 49%, respectively [49,53]. These differences in TP removal are not only attributable to the system layout, but also to factors such as TP uptake by plant roots, microbial uptake, precipitation processes and HRT.

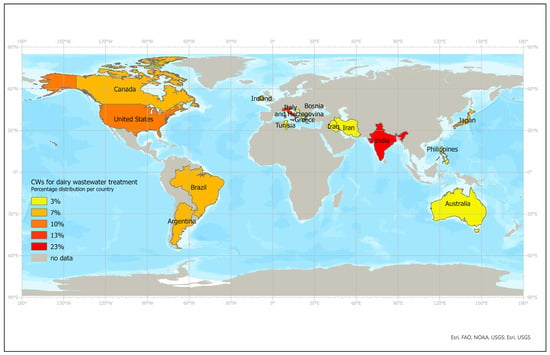

Constructed wetland systems to treat dairy wastewater have been implemented in several countries, as is shown in Figure 7. A comprehensive review of the literature reveals that there are currently 30 CW systems that are specifically designed for this purpose. These systems are spread across 15 countries, with the highest concentration found in India (23%), followed by Italy (13%) and the USA (10%). A total of 3% of the total systems are located in other countries.

Figure 7.

Global distribution of CW systems for dairy wastewater treatment.

3.3.3. Type, Layout and Global Distribution of Livestock CW

Concerning the systems shown in Figure 8, related to LWW treatment, 75% are hybrid systems, 20% are single CW systems and the remaining 5% are unspecified.

Figure 8.

Percentage distribution of different scales of CW systems examined for livestock WW treatment.

Among the hybrid systems, full-scale configurations predominate with 47%, followed by pilot-scale systems at 40% and lab-scale systems at 13%.

In single CWs, compared to hybrid systems, the number of full-scale systems is similar, with 50%; 25% are represented by both lab-scale and microcosm systems. Specifically, in single CWs, all full-scale systems are represented by FWSF configurations, whereas laboratory and microcosm scales consist of tidal flow systems.

Ref. [66] conducted a study on a pilot-scale hybrid system consisting of three tidal flow units. The average removal efficiencies of COD, BOD and TN were 54%, 68% and 49%, respectively. A similar system with the same layout and scale was reported by [64], showing the comparable removal efficiencies of COD, BOD and TN between 26 and 94%, 63–79% and 27–90%, respectively. In contrast, in a study conducted on a full-scale hybrid system (SF–HF), preceded by preliminary (Decanter) and primary treatments (Septic tank), higher removal efficiencies for TSS, COD and BOD were achieved equal to 83%, 91% and 93%, respectively [59]. Similarly, Ref. [78] investigated a system where WW underwent primary treatment (anaerobic tanks), followed by a full-scale hybrid treatment (HF–HF–FWSF–SF–HF–HF), demonstrating COD and BOD removal efficiencies of 90–96% and 92–97%, respectively.

Ref. [73], using a pre-treatment involving a slurry tank, phase separator, aeration tank and settling tank, followed by secondary treatment with a hybrid CW system (HF-HF), reports high removal efficiencies for TSS (92–93%), COD (77–82%) and TP (95–97%). Comparable performances for TSS (84–97%), COD (91–96) and TP (71–90) were highlighted by [67], with the following plant configuration: a solid/liquid separation tank followed by a full-scale hybrid system (VF–VF–VF–HF–VF–VF–VF–HF–VF–VF–HF).

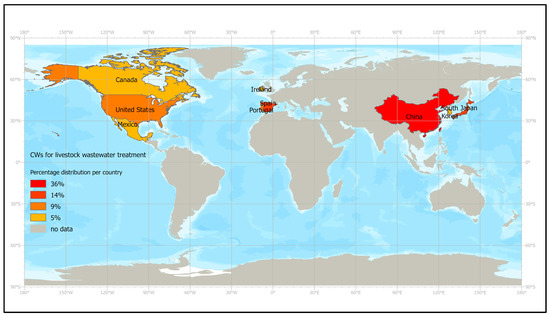

CW systems for livestock WW treatment have been applied across various countries, as illustrated in Figure 9. Based on a global synthesis of the literature, there are currently 20 CW systems for livestock WW treatment. These systems are distributed in nine countries, with the majority being in China (36%), Spain (14%) and Japan (14%), followed by the USA (9%) and Portugal (9%).

Figure 9.

Global distribution of CW systems for livestock WW treatment.

3.3.4. Substrates of Dairy CW Systems

Table 1 shows 30 papers on CW treatment of dairy wastewater. In particular, the substrates examined can be grouped into 13 macro-groups, regardless of system type (full-scale, pilot-scale and laboratory-scale) and layout.

Substrates are among the main components of CW that are responsible for the removal of pollutants from WW. Gravel and sand are the most commonly used substrates, mainly in full-scale systems. This is likely because they are affordable, readily available, and above all, efficient. In fact, gravel is used as a substrate due to its high aeration and nitrification capacity [49]. Additionally, it provides a surface for biofilm development, facilitating the mineralization of organic nitrogen and the oxidation of ammonium ions [96].

In contrast, in systems with significantly smaller surfaces, such as lab-scale or microcosm systems, different substrates have been used to experiment with innovative materials, such as recycled construction and demolition waste, recycled rock processing residues, zeolite, clay, lava rock or mineralized refuse [3,13,14].

In the papers collected for this review, gravel and sand (washed sand, coarse sand, sandy loam) are the most commonly used substrates, being present in 77% and 43% of the surveyed works, respectively. These are followed by soils (e.g., local top soil, natural soil) and clays (expanded clay, LECA) (9%), boulders, ash (e.g., ash clinker ash), silt, zeolite and recycled materials (construction and demolition, rock processing residues and ground ceramic wastes) (6%) and silica quartz river gravel, sandy loam, lava rock and mineralized refuse (2%).

Ref. [37] uses sand and gravel as the filling medium for a full-scale hybrid CW, showing high TSS and COD removal efficiencies of 99.6% and 98.5%, respectively. Similar values, using only gravel, are reported by [40], with removal efficiencies of 99.6% and 92% for TSS and COD, respectively.

Conversely, the use of gravel with a different grain size or the presence of debris or residues in the substrates could have an impact on TSS reduction, as reported by [49,53], who observed lower removal efficiencies (70%). Ref. [67] uses ash in addition to gravel and sand, achieving high BOD5 removal efficiency (94–98%). Similar efficiency values (99.6%) are reported by [40], despite the exclusive use of gravel.

Although these studies used the same substrate, Ref. [49] shows that BOD5 removal was lower (55%). Similarly to TSS, gravel size or retention time may have affected the BOD5 removal efficiencies, as the best performance was recorded at 48 h HRT.

The presence of sub-composted vegetation material in the substrate, as well as oxygen levels in the system, can influence nutrient removal performance. This would explain the different removal efficiencies reported by [36,38] for TN, NH4-N, TP (84%, 68%, 86% and 45%, 37%, 41%, respectively). Moreover, these differences could also be attributed to the different substrates used by [36] (gravel–sand) and [38] (silica quartz river gravel–coarse gravel).

3.3.5. Substrates of Livestock CW Systems

Twenty scientific articles concerning WW treatment by CW were reviewed and are reported in Table 2. Regarding the substrates used, a notable heterogeneity in their application was observed.

Specifically, gravel was used in 45% of the works listed in the table; sand in 20% of the cases; clay and volcanic rock in 15%; ash in 10%; and zeolite, mineralized refuse, alum sludge, aggregate, DAS cakes and rice straw in 5%.

Compared to the treatment systems examined for DWW, these substrates were predominantly employed as filling media in pilot-scale or microcosm systems. This heterogeneity could be attributed to the use of innovative materials in order to test their efficiency and applicability in full-scale systems.

Generally, gravel and sand are the most commonly used substrates. Both were applied by [69,73], resulting in different TSS removal efficiencies of 93% and 20%, respectively. This difference may be due to the sedimentation processes of the particles during treatment, suggesting that a longer retention time is needed, as in the case of [66].

The use of gravel (2–5 cm) alone in HF units [11], and pumice gravel, sand and ash in several units (HF-VF) [66] returned COD removal efficiencies between 90 and 96%. In contrast, the use of gravel and DAS (dewatered alum sludge) exhibited lower performance (54%) [66]. DAS was mainly used to enhance TN removal, rather than organic matter. Refs. [64,66] used alum sludge and DAS cakes, respectively.

Regarding BOD, the removal efficiencies of BOD5 for alum sludge (63–79%) and DAS (68%) were not particularly high. In contrast, gravel and compost used in a hybrid system achieved higher efficiencies, ranging from 84% to 94% [44].

Among the studies reviewed, Ref. [14] used mineralized refuse as a filling medium, specifically employing the finer-sieved fraction. Mineralized refuse was used as a substrate in anaerobic systems to evaluate the denitrifying process. Despite this, high removal efficiencies of NH4-N (>95%) were reported. Similar performance (NH4-N removal efficiency of 92%) was obtained using coarse gravel (4–8 mm) and washed sand, both of which reveal a high NH4-N adsorption capacity [69].

Gravel and sand appear to be the most efficient substrates for removing TP. Refs. [73,97] report efficiencies of 95–97% and 84–88%, respectively. These high performances are likely due to phosphorus binding to substrates as a result of precipitation phenomena [98].

3.3.6. Dairy CW Vegetation

Vegetation plays a crucial role in CW systems. The growth and development of plants, as well as the associated microbial activity, are essential for system performance [99].

It has been demonstrated that planted CWs generally perform better than non-planted systems. However, a study by [100] highlighted that in 29–35% of cases, pollutant removal efficiencies were not significantly affected by the presence or absence of vegetation. This could be attributed to several factors, such as reduced root system development (especially in lab-scale systems), insufficient replication and variation in experimental conditions.

While vegetation certainly provides an esthetic benefit, it also influences other factors, such as temperature and water flow within the systems [101,102]. The root systems of plants enhance aeration in the treatment units and prevent clogging of the bed material by the roots and the development of bacterial colonies in the rhizomes [46]. Furthermore, plants contribute to the removal of pollutants through direct or indirect uptake and degradation processes [103,104].

In the articles revised in this review, 17 different plant species, used in CWs for the DWW treatment, were identified (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of the vegetation used in the examined CWs for dairy wastewater treatment.

Phragmites australis is the most commonly used plant, appearing in 47% of the studies examined. Typha latifolia follows with 35%, Arundo donax with 29%, Schoenoplectus fluviatilis with 24%, Typha angustifolia with 18%, Canna indica, Lemna and Typha domingensis with 12% and Atriplex halimus, Brachiaria ruziziensis, Chrysopogon zizanioides, Cyperus alternifolius, Cyperus papyrus, Hibiscus esculentus, Scirpoides holoschoens, Scirpus and Solanum melongena with 6%.

In 66% of the selected studies, vegetation was present in monoculture. The most frequently used plants were Phragmites australis (24%), Typha angustifolia and Schoenoplectus fluviatilis (14%). In the remaining 34%, which were characterized by the use of several plant species, 22% employed only two species, such as Typha latifolia and Phragmites australis, Schoenoplectus fluviatilis and Scirpus, Arundo donax and Cyperus alternifolius or Typha spp. and Lemna, etc.

Phragmites australis or ‘common reed’ is the most commonly used plant due to its numerous advantages, such as rapid growth, even in wet conditions, a deep root system, longevity and its ability to treat WW [105]; for these reasons, it is the most widely used plant worldwide [104,106].

Ref. [53] reports TSS removal efficiencies of 70%, using Chrysopogon zizanioides in VF systems. Generally, higher efficiencies (around 90%) are reported in the literature.

For instance, Ref. [27] shows TSS removal efficiencies of 86%, 84% and 79%, respectively, with Phragmites australis, Juncaeae and a non-vegetated system. This highlights the importance of vegetation in CWs. In particular, these macrophytes were selected for their tolerance to mild, tropical and subtropical climates, as well as their ability to grow in substrates saturated with brackish or saline water. Furthermore, plants influence ammonification and nitrification processes, having the capacity to absorb nitrogen in both ammoniacal and nitric form [107,108].

For example, Ref. [40] reports that the presence of microalgae such as Brachiaria ruziziensis led to a reduction in NH4-N uptake. Ref. [4] uses Typha domingensis in a hybrid system (VF-FWSF-HF), achieving an average TP removal efficiency of around 65%. Higher average removals (86%) were reported by [36] in a hybrid system (VF-HF-VF) using Arundo donax, Hibiscus esculentus and Solanum melongena. Nevertheless, in both cases, lower efficiencies were observed in the VF systems, demonstrating that HF and FWSF are more effective at removing TP through plant uptake than through substrate adsorption processes. Ref. [51] demonstrates that Typha domingensis exhibited faster growth after the systems were filled with DWW, due to the higher nutrient supply. In contrast, under conditions of high temperatures and different substrates, plant growth was inhibited.

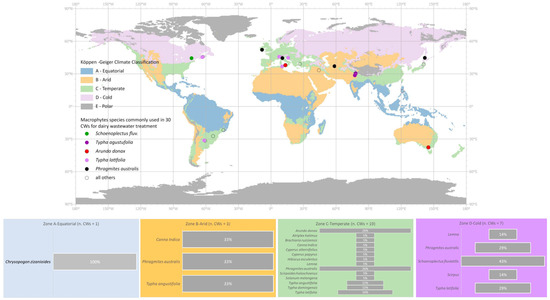

The spatial distribution of vegetation species used in CW systems for dairy WW treatment indicated that Phragmites australis has been utilized across all climate zones (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Koppen–Geiger climate classification and spatial distribution of macrophyte species used in CW for dairy wastewater treatment.

Chrysopogon zizanioide (vetiver grass), a native species of southern and south-eastern Asia [109], has been planted in the only CW system located in the A-equatorial zone (Figure 10), in the Republic of the Philippines [53]. It is a species that has been introduced to this archipelagic country, and now it is widely distributed [110,111].

Three CW systems are located in the B-Arid zone, with each one planted with different macrophytes that are used as a monoculture: Typha angustifolia, Canna indica and Phragmites australis (Figure 10). Typha angustifolia, a native species of the temperate zone [111], was used in a pilot CW system located in the north of India [55]. Canna Indica, common to tropical regions of Latin America [112], was planted in a CW located in Iraq [50], even though it is not native and was not introduced in this country [111]. Schoenoplectus fluviatilis, widely distributed across most of the temperate zone of North America, Australia and New Zealand [111], is a perennial sedge used in 43% of CWs located in the D-cold zone, followed by Typha latifolia (29%), Phragmites australis (29%), Scirpus (14%) and Lemna (14%) (Figure 10).

The C-Temperate zone is the climate zone with the highest number of different macrophytes used (n.14). Arundo donax and Phragmites australis have been utilized in 19% of the CW systems located in the C-Temperate climate, followed by Typha angustifolia (11%). All other vegetation species have limited applications in few CW systems.

3.3.7. Livestock CW Vegetation

Concerning vegetation used in CWs for the treatment of LWW, Table 6 shows the 22 species investigated in this study.

Table 6.

Results of the vegetation used in studied CWs for livestock wastewater treatment.

As with DWW treatment systems, Phragmites australis is the most frequently used species, appearing in 60% of the cases, followed by Typha latifolia (14%), Carex paniculata and Suaeda vera (9%) and several other species (5%). These include Acorus calamus, Canna indica, Chrysopogon zizanioides, Cyperus alternifolius, Eichhornia crassipes, Eleocharis palustris, Ipomoea aquatica, Miscanthus sacchariflorus, Myriophyllum aquaticum, Nasturtium officinale, Nelumbo nucifera, Phragmites japonica, Polygonum hydropiper, Schoenoplectus luviatilis, Scirpus, Typha angustifolia, Typha latifolia, Typha orientalis, Zizania latifolia and Zizania palustris.

Phragmites australis was used by [69,73], as it is the most commonly used macrophyte in wetland treatments. These studies also used Suaeda vera (a halophyte) to remove soluble salts from swine WW during pre-treatment. In both cases, 50% of each species was distributed at a density of 10 plants per m2. Several other authors have exclusively used Phragmites australis.

For example, Ref. [66] observed the vigorous growth of Phragmites australis within two months. Ref. [63] underlines how Phragmites australis probably had high removal efficiencies. Indeed, ammonia reduction may also be influenced by plant uptake.

Ref. [59] highlights the effectiveness of Carex paniculata in removing about 50% of nutrients and microorganisms, compared to a septic tank. Results from [3] indicated that nutrient removal efficiency increased over time with Typha Latifolia; for example, NH4-N removal improved from 62% to 94%. In contrast, Phragmites australis showed no clear trend over time, with removal efficiencies ranging from 62% to 84%.

In general, LWW had a negative impact on the vegetation, as evidenced by a change in the appearance of the plants. Initially, the plants appeared vigorous, but by the end of the experiment, they exhibited signs of weakness and malnutrition.

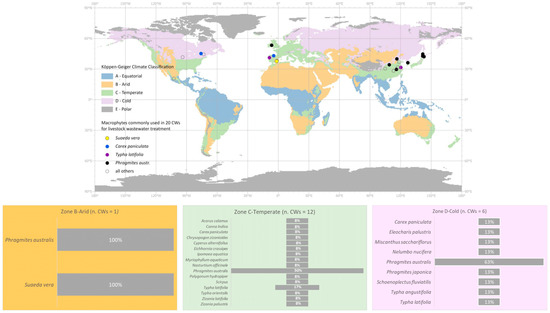

The spatial distribution of the vegetation species used in CW systems for livestock WW treatment indicated that Phragmites australis has been utilized from the B-Arid to the D-cold zone (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Koppen–Geiger climate classification and spatial distribution of macrophytes species used in CW systems for livestock wastewater treatment.

Typha latifolia, a perennial wetland plant distributed worldwide in tropic and temperate climates [57], has been planted in 17% of the CWs located in the C-Temperate zone and in 13% of the CWs located in the D-Cold zone (Figure 11). Carex paniculate can be found in Europe and Asia and prefers temperate climates [111]. It was used as a monoculture in the full-scale CW system located in the C-Temperate zone of Spain [59] and in the full-scale CW system located in the D-Temperate zone of Canada, which is also planted with Typha latifolia and Eleocharis palustris [71].

C-Temperate zone is the climate zone with the highest number of different macrophytes used (n.16), followed by nine different species used in the CWs located in the D-cold zone and only two vegetation species (Suaeda vera and Phragmites australis) planted in CWs distributed in the B-Arid zone (Figure 11). Suaeda vera, primarily diffused in the temperate zone of Europe and northern countries in Africa [111], was planted together with Phragmites australis in a full-scale and pilot-scale CW system, both located in Spain [69,73].

4. Main Management Aspects

The proper management of CWs can only be achieved through continuous monitoring. Indeed, the data collected during monitoring enable simple, periodic maintenance operations that do not require specialized personnel. For example, the water level should be monitored, especially in sub-surface flow systems. In these systems, the water level must remain constantly below the substrate to prevent runoff or sludge formation.

In particular, WWs generated by dairy and livestock farming are characterised by a high sludge content. Therefore, appropriate management of both pre-treatment and CW systems is essential to ensure proper functioning, optimal performance and a long service life of the entire system. Adequate management (removal, emptying and cleaning) of the pre-treatment (sedimentation and degreasing) and primary (Imhoff tank) systems is necessary. In CWs, the first treatment stage may be subject to clogging of the filling medium if it receives effluent with high sludge and TSS concentrations. Excessive sludge accumulation at the first treatment stage (e.g., VF) can be mitigated by temporarily stopping feed to the bed; it dries completely, allowing for subsequent removal. The drying process creates macropores, restoring regular effluent percolation. Furthermore, to avoid clogging and maintain uniform distribution within the pipeline, it may be necessary to clean the distribution holes. In some cases, removal and replacement of the clogged substrate layer may be required [29]. Each CW must be managed according to the quali-quantitative characteristics of the treated WW; otherwise, long-term management difficulties may arise [29,113].

In hybrid CWs treating DWW, the daily influent flow ranged from 0.1 to 15 m3·day−1. The reported HRTs varied between 3 and 14 days. Overall, the COD removal efficiencies ranged from 62% to 99%, with a mean value of 82% (±12% SD). Case studies reporting COD removal efficiencies greater than 90% suggest that reliable system performance is typically achieved when the first treatment stage operates at an average HLR of 25–33 mm·day−1. The daily flow rate of LWW treatment systems was approximately five times higher than that observed for DWW, ranging from 0.4 to 100 m3·day−1. Consequently, HRT appears higher, showing values ranging from 4 to 29 days. COD removal efficiency varied from 26% to 94%, with a mean value of 73% (±21% SD). Case studies reporting removal efficiencies greater than 90% indicate that a stable and effective treatment performance is achieved when the first stage units operate at an average HLR of 6–40 mm·day−1.

To optimize system management, it is ideal to monitor certain water parameters, such as NH4-N and pH. In general, LWW shows high NH4-N concentrations at the system inlet. Therefore, it is recommended to use a VF unit as the first treatment stage. Operating under aerobic conditions, the VF unit effectively promotes nitrification activity, reducing NH4-N concentrations and minimizing odors caused by its decomposition.

Additionally, it is recommended to monitor the influent pH values throughout the year to evaluate the need for pH correction, particularly for water from production activities, washing, cleaning and disinfection of machinery. This correction is achieved by adding calcium or similar alkaline chemicals.

With regard to vegetation, cutting operations are typically required once a year. In such cases, it is crucial to remove plant residues, as their degradation over time may lead to substrate clogging. Moreover, substances released by these residues could inhibit microbial growth, affecting the proper functioning of processes inside the CW [114].

5. Conclusions

The recovery and reuse of DWW and LWW have attracted considerable interest. This review highlights the physico-chemical characteristics of DWW and LWW and the advantages of treating them through CWs. It examined numerous published studies that employed CWs for treating several wastewaters. Monitoring activities were conducted at different locations, using systems of varying scales (full-scale, pilot-scale, lab-scale and microcosm) and configurations (single units or hybrid systems), employing different substrates and vegetation. Efforts were made to consider and tabulate only the operational parameters that are consistently reported across all the reviewed studies. The performance of CWs in treating WW varied considerably, due to numerous biotic and abiotic factors affecting the key biological, physical and chemical processes occurring in the systems. Despite these variations, all the reviewed WW treatment systems demonstrated high efficiency in pollutant removal. It is evident, however, that pre-treatment (preliminary and primary) is necessary to reduce TSS and remove fats, which negatively influence microbial activity in DWW and reduce coarse solids in LWW, thereby minimizing sludge accumulation. A pre-treated effluent appears to achieve improved performance when processed through hybrid systems. Specifically, hybrid configurations such as VF-HF showed high performance in reducing TSS and organic matter in DWW, as well as NH4-N in LWW, due to the nitrification (VF) and denitrification (HF) processes. Furthermore, the use of gravel and sand as filling substrates for the different units proved to be the most effective. Gravel, in particular, was found to be efficient in removing TP concentrations. Regarding vegetation, Phragmites australis, Arundo donax and Phragmites australis, Typha spp. were the most commonly used species for DWW and LWW, respectively. These plants were chosen not only for their tolerance to different climates, but also for their ability to grow in highly saline waters. Laboratory-scale systems and microcosms were used in many studies, often to test alternatives. Such investigations aim to evaluate the efficiency of these materials in treating dairy and livestock effluents under controlled conditions. Optimizing substrate efficiency could facilitate their application in full-scale systems, potentially reducing the required surface area, which remains one of the primary limitations of CWs. Therefore, the knowledge and skills gained from these studies could be utilized as a valuable foundation for future WW treatment activities. In conclusion, nature-based solutions for the treatment of DWW and LWW through CWs represent a sustainable management approach, enabling the recovery and reuse of WW while reducing contaminant levels in water bodies and soil.

Author Contributions

S.B.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. A.C.M.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. M.M.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out within the Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR)—MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.4–40 D.D. 1032 17 June 2022, CN00000022). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions; neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ahmad, T.; Aadil, R.M.; Ahmed, H.; ur Rahman, U.; Soares, B.C.V.; Souza, S.L.Q.; Pimentel, T.C.; Scudino, H.; Guimarães, J.T.; Esmerino, E.A.; et al. Treatment and utilization of dairy industrial waste: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, A.; Silva-Gálvez, A.L.; Aguilar-Juárez, Ó.; Senés-Guerrero, C.; Orozco-Nunnelly, D.A.; Carrillo-Nieves, D.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. Microalgae-based livestock wastewater treatment (MbWT) as a circular bioeconomy approach: Enhancement of biomass productivity, pollutant removal and high-value compound production. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.; Mucha, A.P.; Duarte Crespo, R.; Rodrigues, P.; Almeida, C.M.R. Livestock Wastewater Treatment in Constructed Wetlands for Agriculture Reuse. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocetti, E.; Hadad, H.R.; Maine, M.A.; Di Luca, G.A.; de las Mercedes Mufarrege, M. Effect of pollutant loading rate and macrophyte uptake on the performance of a pilot-scale hybrid wetland system for the final treatment of dairy wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 204, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Liu, Z.; Pan, X.; Huang, E.; Chen, D.; Xiao, Z. Effects of dilution ratio on nutrient removal, sedimentation efficiency, and lipid production by Scenedesmus obliquus in diluted cattle wastewater. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2019, 42, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Fernandez, G.; Barker, A.; Gregory, J.; Cumby, T. Efficiency of reed beds in treating dairy wastewater. Biosyst. Eng. 2007, 98, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierano, M.C.; Panigatti, M.C.; Maine, M.A.; Griffa, C.A.; Boglione, R. Horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland for tertiary treatment of dairy wastewater: Removal efficiencies and plant uptake. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 272, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jin, W.; Xiong, J.; Wang, S.F.; Gu, P. Investigation of a full-scale anaerobic-aerobic and constructed wetlands integrated system treating livestock wastewater. Adv. Mater. Res. 2010, 113–116, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.D.; Saraiva, C.B.; Bottrel, S.E.C.; Dias, E.H.O. Feasibility study of constructed wetlands for the treatment of dairy effluents. Rev. AIDIS Ing. Cienc. Ambientales Investig. Desarro. Pr’actica 2021, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, M.; Peñaloza, R.; Espinoza, C.; Espinoza, W.; Mezarina, J. Treatment of dairy industry wastewater using bacterial biomass isolated from eutrophic lake sediments for the production of agricultural water. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Li, X.; Wu, S.; Yang, C. Sustainable livestock wastewater treatment via phytoremediation: Current status and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinjie, W.; Xin, N.; Qilu, C.; Ligen, X.; Yuhua, Z.; Qifa, Z. Vetiver Dictyosphaerium sp. co-culture for the removal of nutrients ecological inactivation of pathogens in swine wastewater. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 20, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsia, D.; Sympikou, T.; Topi, E.; Pappa, F.; Matsoukas, C.; Fountoulakis, M.S. Use of recycled construction and demolition waste as substrate in constructed wetlands for the wastewater treatment of cheese production. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 362, 121324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Sun, C.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Jia, B.; Zhang, Y. Roles of vegetation, flow type and filled depth on livestock wastewater treatment through multi-level mineralized refuse-based constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 39, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E. Advantages and disadvantages of techniques used for wastewater treatment. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, A.; Akratos, C.S.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Vertical Flow Constructed Wetlands: Eco-Engineering Systems for Wastewater and Sludge Treatment; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parde, D.; Patwa, A.; Shukla, A.; Vijay, R.; Killedar, D.J.; Kumar, R. A review of constructed wetland on type, treatment and technology of wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melbourne Water. Constructed Shallow Lake System: Design Guideline for Developers, Version 2; Melbourne Water: Melbourne, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsan, J.S.; Subramani, S.; Rajan, R.J.; Shah, I.; Nithiyanantham, S. Simulation of constructed wetland in treating wastewater using fuzzy logic technique. J. Phys. 2018, 1000, 012137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J.; Kröpfelová, L. Wastewater Treatment in Constructed Wetlands with Horizontal Sub-Surface Flow; Springer Science & Business Media: Durham, NC, USA, 2008; Volume 14, pp. 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, M.A.; Saleh, H.I.; El-Quosy, D.E.; Mahmoud, A.A. Improving water quality in polluted drains with free water surface constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, M.L.; Soriano, P.; Ciria, M.P. Constructed wetlands as a sustainable solution for wastewater treatment in small villages. Biosyst. Eng. 2004, 87, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steer, D.; Fraser, L.; Boddy, J.; Seibert, B. Efficiency of small constructed wetlands for subsurface treatment of single-family domestic effluent. Ecol. Eng. 2002, 18, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, E.; Ulrich, L.; Luthi, C. Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies, 2nd ed.; Eawag: Dübendorf, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.; Edwards, R.; Garber, L.; Isaacs, B. A Handbook of Constructed Wetlands, General Considerations; US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, T.; Afrin, R.; Al Muyeed, A.; Sun, G. Treatment of tannery wastewater in a pilot-scale hybrid constructed wetland system in Bangladesh. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdania, V.; Golestanib, H.A. Advanced treatment of dairy industrial wastewater using vertical flow constructed wetlands. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019, 162, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, A.C.; Cirelli, G.L.; Cavallaro, V.; Di Silvestro, I.; Pacifici, P.; Castiglione, V.; Milani, M. Growth and biomass production of different plant species in two different constructed wetland systems in Sicily. Desalination 2009, 246, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, D. Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment. Građevinar 2017, 69, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Does clogging a ect long-term removal of organics and suspended solids in gravel-based horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands? Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 331, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, A.; Sciuto, L.; Licciardello, F.; Cirelli, G.L.; Milani, M.; Barbera, A.C. Effects of solids accumulation on greenhouse gas emissions, substrate, plant growth and performance of a Mediterranean horizontal flow treatment wetland. Environments 2019, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintakovid, W.; Visoottiviseth, P.; Khokiattiwong, S.; Lauengsuchonkul, S. Potential of the hybrid marigolds for arsenic phytoremediation and income generation of remediators in Ron Phibun District, Thailand. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 1532–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, S.; Karlson, U. Aspects of phytoremediation of organic pollutants. J. Soil. Sediment. 2001, 1, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardonville, M.; Bockstaller, C.; Therond, O. Review of quantitative evaluations of the resilience, vulnerability, robustness and adaptive capacity of temperate agricultural systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, G.; Gautam, D.; Bedi, M.K. Optimization of dairy sludge for growth of Rhizobium cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 845264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildbrett, G. Bewertung von reinigungus-und desinfektionsmitteln imabwasser, Dtsch. Milchwirtschaft 1998, 39, 616–620. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.K.; Rausa, K.; Rani, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, M. Biopurification of dairy farm wastewater through hybrid constructed wetland system: Groundwater quality and health implications. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.C. Plants for constructed wetland systems—A comparison of the growth and nutrient uptake of eight emergent species. Ecol. Eng. 1996, 7, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.F.; Pomeroy, J.W.; Ellis, C.R. Multivariable evaluation of hydrological model predictions for headwater basin in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 1635–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maine, M.A.; Hadad, H.R.; S’anchez, G.C.; Di Luca, G.A.; Mufarrege, M.M.; Caffaratti, S.E.; Pedro, M.D. Long-term performance of two free-water surface wetlands for metallurgical effluent treatment. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 98, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Prazeres, A.R.; Rivas, J. Cheese whey wastewater: Characterization and treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 445–446, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.; Hannachi, C.; Mhiri, F.; Hamrouni, B. Performances of constructed wetland system to treat whey and dairy wastewater during a macrophytes life cycle. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 318, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendonça, H.V.; Otenio, M.H.; Lomeu, A.A.; Santa Rita, A.V. Post-treatment of an aerated facultative pond with constructed wetland: First two years of operation in a dairy industry. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 179, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, J.; Inoue, T.; Kato, K.; Uraie, N.; Sakuragi, H. Performance evaluation of hybrid treatment wetland for six years of operation in cold climate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 12861–12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, M.T.T. The use of constructed wetlands for the treatment of agro-industrial wastewater—A case study in a dairy-cattle farm in Sicily (Italy). Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 76, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakshi, D.; Sharma, P.K.; Rani, A.; Malaviya, P.; Srivastava, V.; Kumar, M. Performance evaluation of vertical constructed wetland units with hydraulic retention time as a variable operating factor. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 19, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, M.; Farruggia, D.; Tuttolomondo, T.; Iacuzzi, N.; Leto, C.; Di Miceli, G. Seasonal Response of Vegetation on Pollutants Removal in Constructed Wetland System Treating Dairy Wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 182, 106727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mohsein, H.S.; Feng, M.; Fukuda, Y.; Tada, C. Remarkable Removal of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria During Dairy Wastewater Treatment Using Hybrid Full-scale Constructed Wetland. Water Air Soil Pollut 2020, 231, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toromanović, M.; Ibrahimpašić, J.; Dragičević, T.L. Horizontal Flow Pilot Constructed Wetland For Dairy Wastewater Purification. Spring 2023, 56, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelissari, C.; Sezerino, P.H.; Decezaro, S.T.; Wolff, D.B.; Bento, A.P.; de Carvalho Junior, O.; Philippi, L.S. Nitrogen transformation in horizontal and vertical flow constructed wetlands applied for dairy cattle wastewater treatment in southern Brazil. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 73, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Suthar, S. Performance assessment of horizontal and vertical surface flow constructed wetland system in wastewater treatment using multivariate principal component analysis. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 116, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçsiper, B.; Drizo, A.; Twohig, E. Constructed wetlands as a potential management practice for cold climate dairy effluent treatment VT, USA. CATENA 2015, 135, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Drizo, A.; Rizzo, D.M.; Druschel, G.; Hayden, N.; Twohig, E. Evaluating the efficiency and temporal variation of pilot-scale constructed wetlands and steel slag phosphorus removing filters for treating dairy wastewater. Water Res. 2010, 44, 4077–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adera, S.; Drizo, A.; Twohig, E.; Jagannathan, K.; Benoit, G. Improving Performance of Treatment Wetlands: Evaluation of Supplemental Aeration, Varying Flow Direction, and Phosphorus Removing Filters. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.A.; Ismail, Z.Z. Green sustainable technology for biotreatment of actual dairy wastewater in constructed wetland. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierano, M.C.; Maine, M.A.; Panigatti, M.C. Dairy farm wastewater treatment using horizontal subsurface flow wetlands with Typha domingensis and different substrates. Environ. Technol. 2016, 38, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovi, P.; Marmiroli, M.; Maestri, E.; Tagliavini, S.; Piccinini, S.; Marmiroli, N. Application of a Horizontal Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetland on Treatment of Dairy Parlor Wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 88, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, P.P.; Dala, P.S.; Sundo, M.B.; De Padua, V.M.N.; Madlangbayan, M.S. Effect of Varying Retention Times and Feeding Schemes on the Performance of Vertical Constructed Wetlands Planted with Vetiver Grass in Treating Dairy Wastewater in the Philippines. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2024, 33, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Rani, A.; Minakshi, D.; Malaviya, P. Effect of influent load fluctuation on the efficiency of vertical constructed wetlands treating dairy farm wastewater. Adv. Environ. Technol. 2023, 9, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Gopal, B. Effect of hydraulic retention time on the treatment of secondary effluent in a subsurface flow constructed wetland. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorra, R.; Freppaz, M.; Zanini, E.; Scalenghe, R. Mountain Dairy Wastewater Treatment with the Use of a ‘Irregularly Shaped’ Constructed Wetland (Aosta Valley, Italy). Ecol. Eng. 2014, 73, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.G. Typha: Its taxonomy and the ecological significance of hybrids. Arch. Hydrobiol. Beih. 1987, 27, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, S.M.; Jones, P.L.; Salzman, S.A.; Croatto, G.; Allinson, G. Evaluation of the giant reed (Arundo donax) in horizontal subsurface flow wetlands for the treatment of dairy processing factory wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 3525–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero Fernandez, D.; Expósito Camargo, J.A.; Peña Fernandez, M.; Antizar-Ladislao, B. Carex paniculata constructed wetland efficacy for stormwater, sewage and livestock wastewater treatment in rural settlements of mountain areas. Water Sci. Technol. 2019, 79, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.C.; Li, T.X.; Zeng, F.F.; Zhang, X.Z.; Yu, H.Y.; Wang, Y.D.; Liu, T. Accumulation characteristics of and removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from livestock wastewater by Polygonum hydropiper. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 117, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorme, J.B.; Maniquiz, M.C.; Lee, S.; Kim, L.H. Seasonal changes of plant biomass at a constructed wetland in a livestock watershed area. Desalination Water Treat. 2012, 45, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian-sheng, H.; Hong-liang, L.; Bei-dou, X.; Ying-bo, Z. Effects of effluent recirculation in vertical-flow constructed wetland on treatment efficiency of livestock wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2006, 54, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Marisa, C.; Almeida, R.; Ribeiro, I.; Mucha, A.P. Potential of constructed wetland for the removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria from livestock wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 129, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.S.; Kumar, J.L.G.; Akintunde, A.O.; Zhao, X.H.; Zhao, Y.Q. Effects of livestock wastewater variety and disinfectants on the performance of constructed wetlands in organic matters and nitrogen removal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2011, 18, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Wu, S.B.; Sun, F.; Lv, T.; Dong, R.J.; Pang, C.L. Performance of Lab-Scale Tidal Flow Constructed Wetlands Treating Livestock Wastewater. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 518–523, 2631–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, D.; Dong, J.; Tan, S.K. Application of Constructed Wetlands for Treating Agricultural Runoff and Agro-Industrial Wastewater: A Review. Hydrobiologia 2018, 805, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Inoue, T.; Kato, K.; Izumoto, H.; Harada, J.; Wu, D.; Sugawara, Y. Multi-stage hybrid subsurface flow constructed wetlands for treating piggery and dairy wastewater in cold climate. Environ. Technol. 2016, 38, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Luo, P.; Liu, F.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, R.; Yin, L.; Zhou, J.; Wu, J. Nitrogen removal and distribution of ammonia-oxidizing and denitrifying genes in an integrated constructed wetland for swine wastewater treatment. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 104, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valero, A.; Acosta, J.A.; Faz, Á.; Gómez-López, M.D.; Carmona, D.M.; Terrero, M.A.; El Bied, O.; Martínez-Martínez, S. Swine Wastewater Treatment System Using Constructed Wetlands Connected in Series. Agronomy 2024, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Mora-Orozco, C.; González-Acuña, I.J.; Saucedo-Terán, R.A.; Flores-López, H.E.; Rubio-Arias, H.O.; Ochoa-Rivero, J.M. Removing Organic Matter and Nutrients from Pig Farm Wastewater with a Constructed Wetland System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayman, D.; Maaskant, K. Research Sub-Program, Environmental Monitoring of Agricultural Constructed Wetlands—A Provincial Study. COESA Report No.: LMAP-014/94. 1994. Agriculture Canada. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10214/15026 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Brenton, W. A Constructed Wetland in USE: 28 Years. In Constructed Wetlands for Animal Waste Management, Proceedings of the Workshop Sponsored by the Conservation Technology Information Center, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Soil Conservation Service (SCS), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Region V, and Purdue University Agricultural Research Program, Lafayette, IN, USA, 4–6 April 1994; DuBowy, P., Reaves, R., Eds.; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Terrero, M.A.; Muñoz, M.Á.; Faz, Á.; Gómez-López, M.D.; Acosta, J.A. Efficiency of an Integrated Purification System for Pig Slurry Treatment under Mediterranean Climate. Agronomy 2020, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Gálvez, A.L.; López-Sánchez, A.; Camargo-Valero, M.A.; Prosenc, F.; González-López, M.E.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. Strategies for livestock wastewater treatment and optimised nutrient recovery using microalgal-based technologies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 384, 120258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Huang, S.; Scholz, M. Nutrient removal in wetlands during intermittent artificial aeration. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2008, 25, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.S.; Liu, Y.W.; Zhou, J.L.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Bui, X.T.; Zhang, X.B. Bioprocessing for elimination antibiotics and hormones from swine wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 1664–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, M.; Moscatelli, A.; Stroppa, N.; Onelli, E.; Pilu, S.; Baldi, A.; Rossi, L. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals from wastewater through a Typha latifolia and Thelypteris palustris phytoremediation system. Chemosphere 2020, 241, 125018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirel, B.; Yenigun, O.; Turgut, T. Anaerobic Treatment of Dairy Wastewaters: A Review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 2583–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamsari, R.; Karmanshahi, R.; Nosrati, M.; Amani, T. Enzymatic pre-hydrolysis of high fat content dairy wastewater as a pretreatment for anaerobic digestion. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2012, 6, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshiba, G.J.; Senthil Kumar, P.K.; Femina, C.C.; Jayashree, E.; Racchana, R.; Sivanesan, S. Critical review on biological treatment strategies of dairy wastewater. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019, 160, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.R.; Bhuvaneshwari, S.; Majeed, F.; Jose, E.; Mohan, A. Different treatment methodologies and reactors employed for dairy effluent treatment—A review. J. Water Process. Eng. 2022, 46, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]