Different Alternate Bar Dynamics Under Different Channel Width and Flow Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Basic Equations

2.2. Channel Conditions

2.3. Discharge Conditions

3. Results

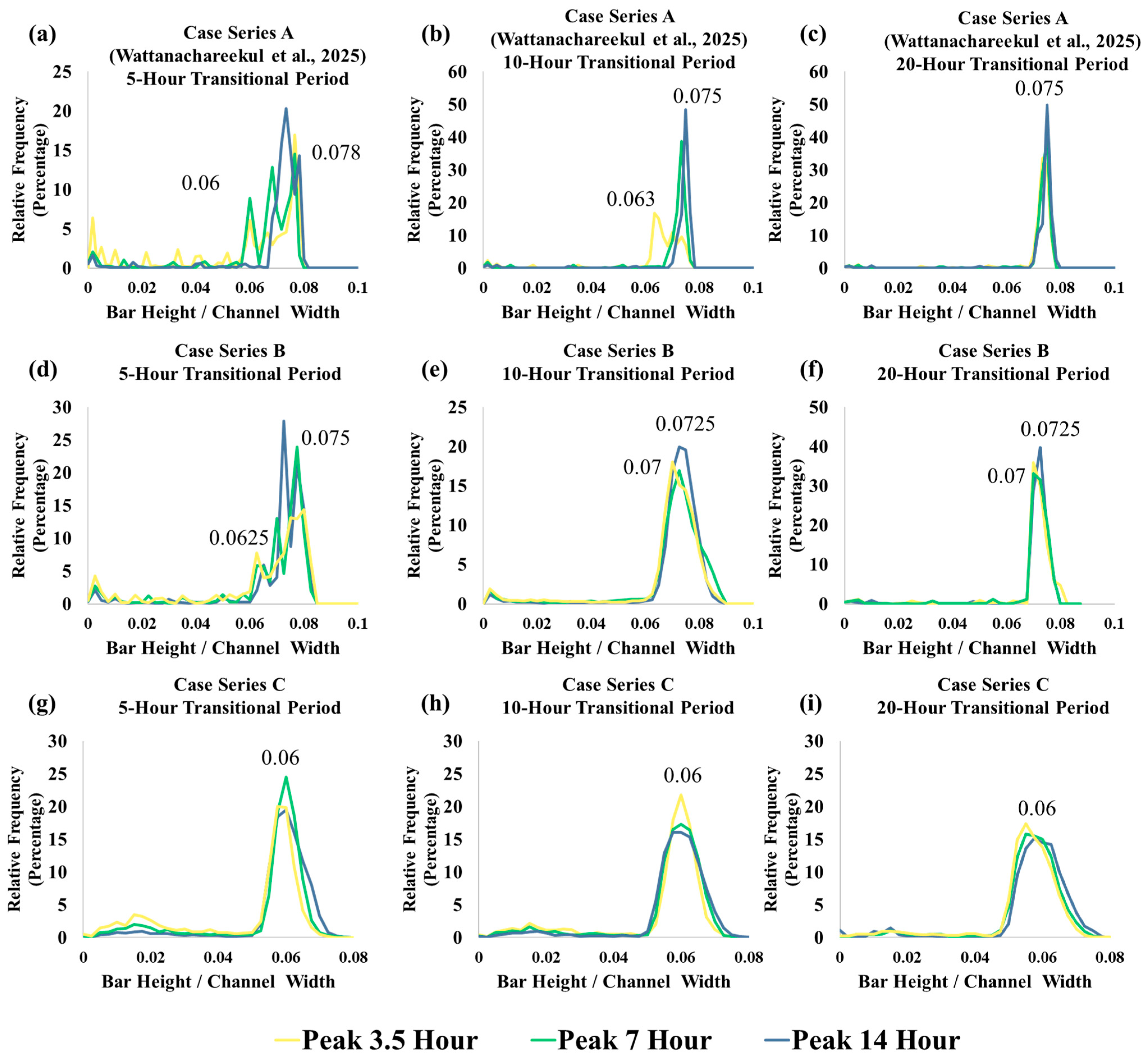

3.1. Case Series A [18]

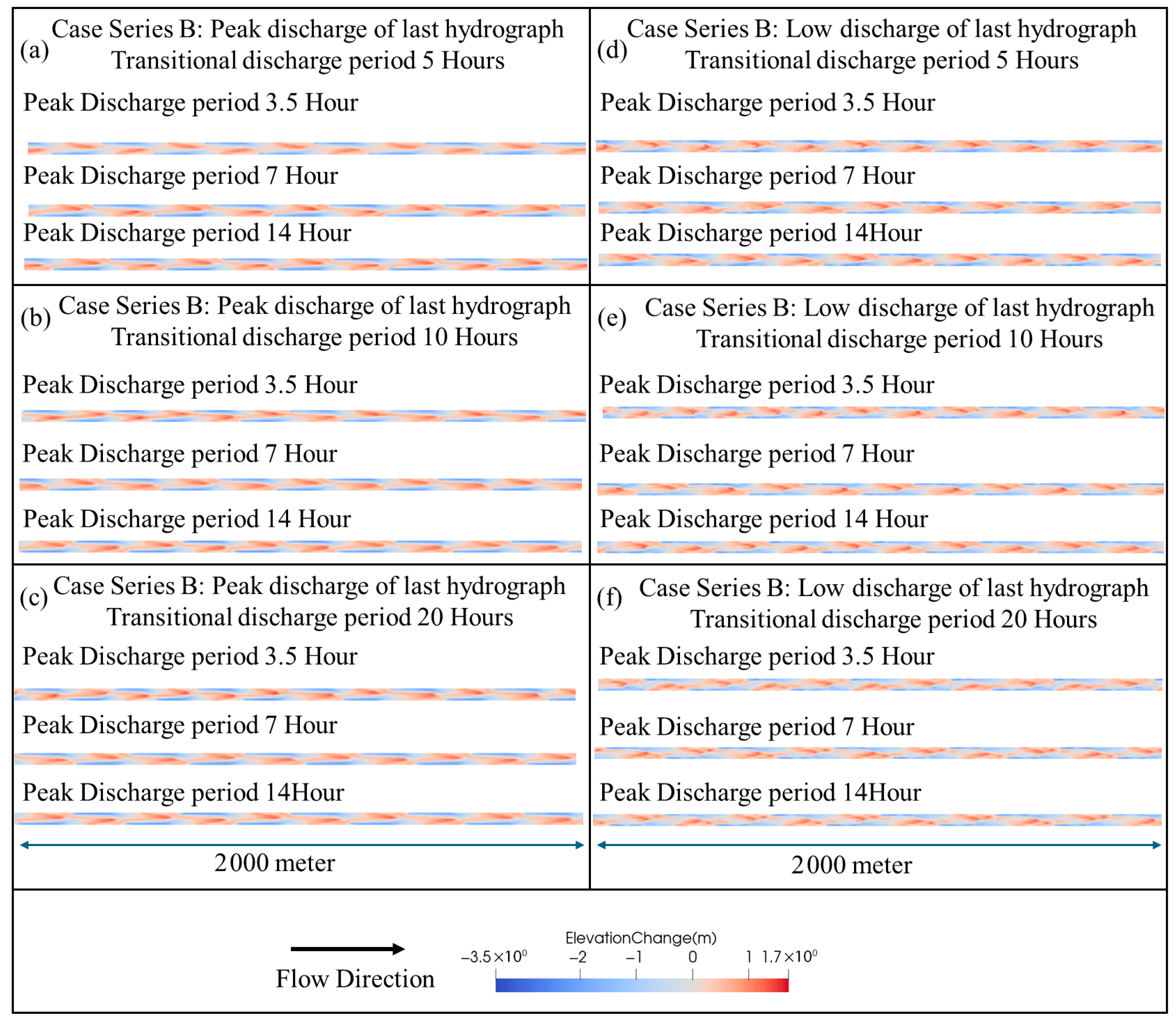

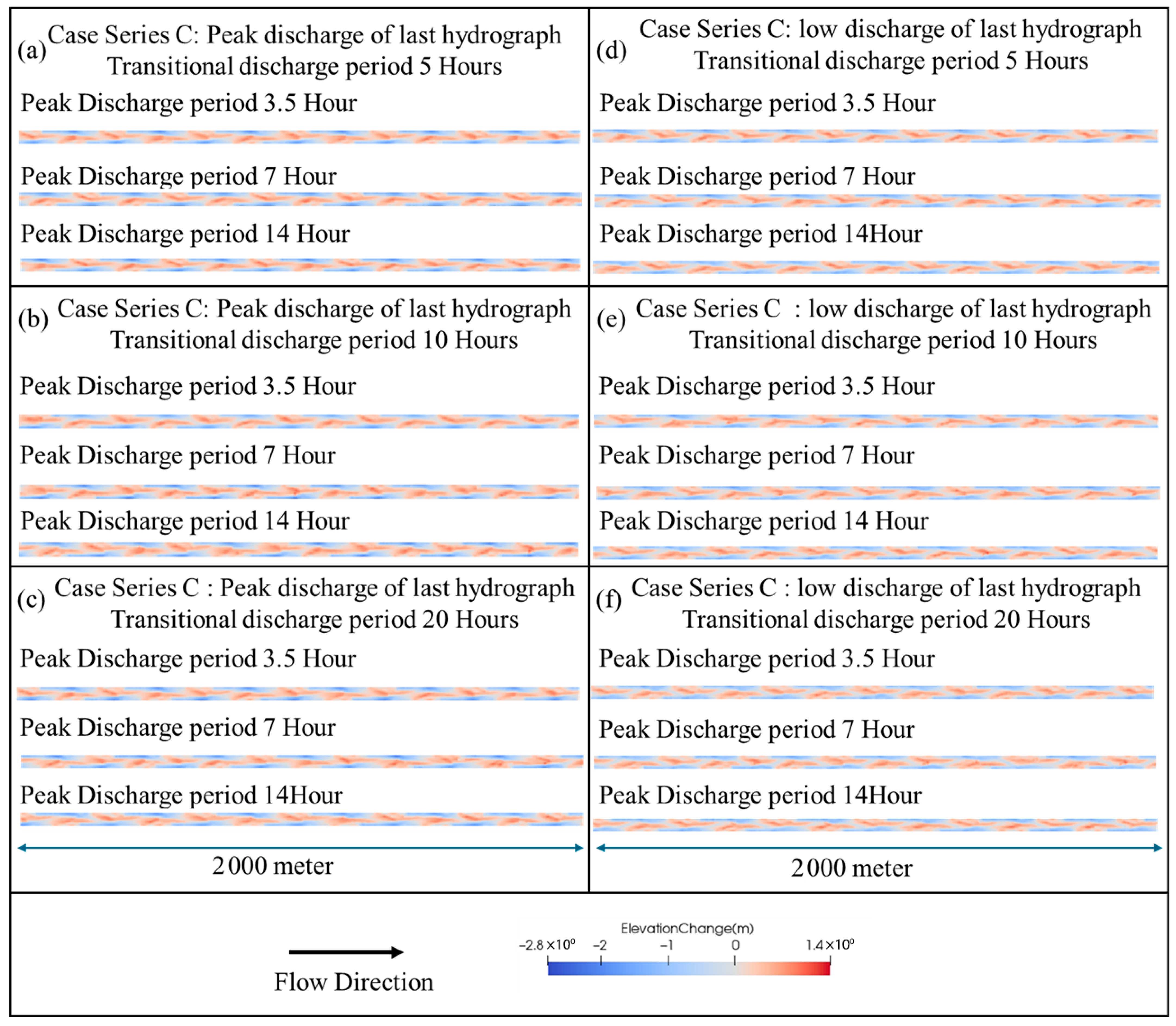

3.2. Case Series B

3.3. Case Series C

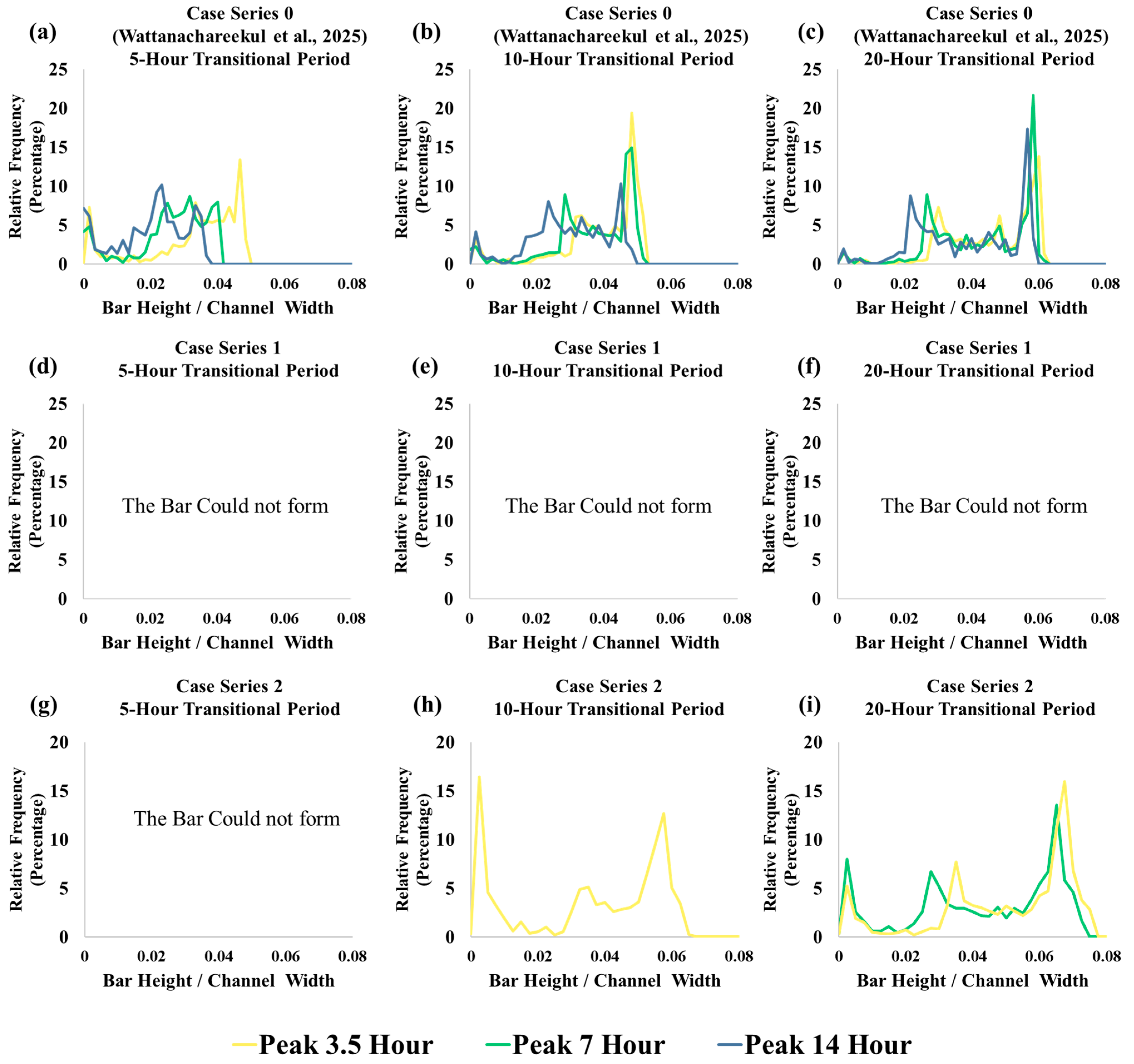

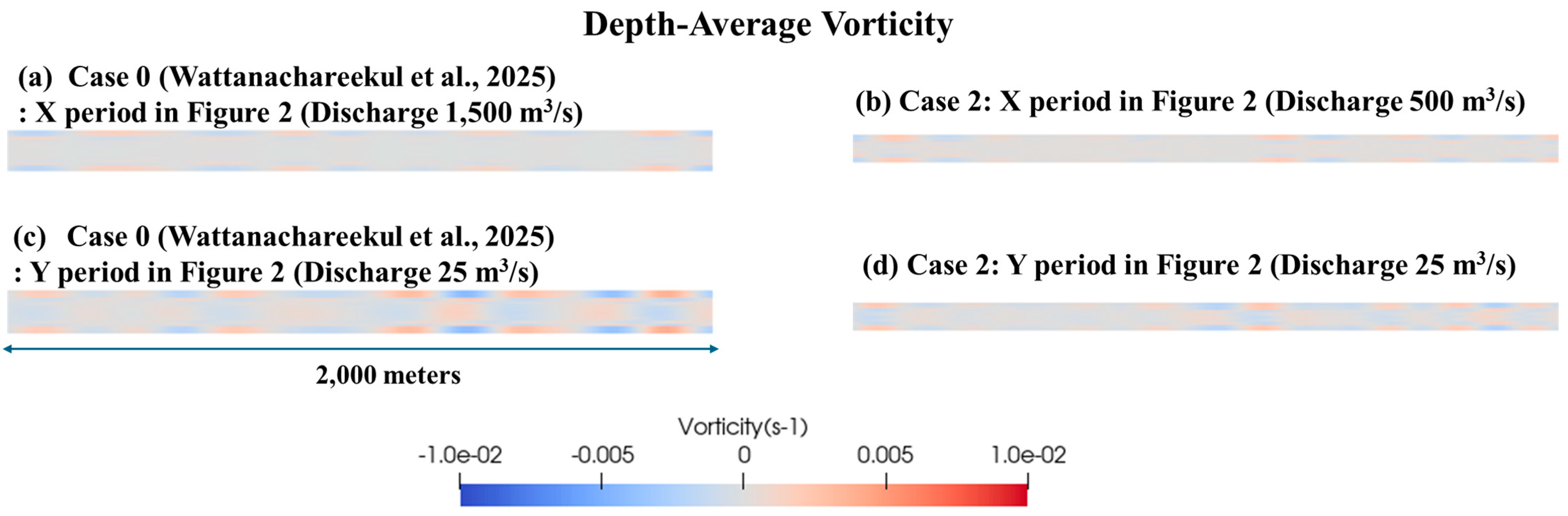

3.4. Case Series 0 [18]

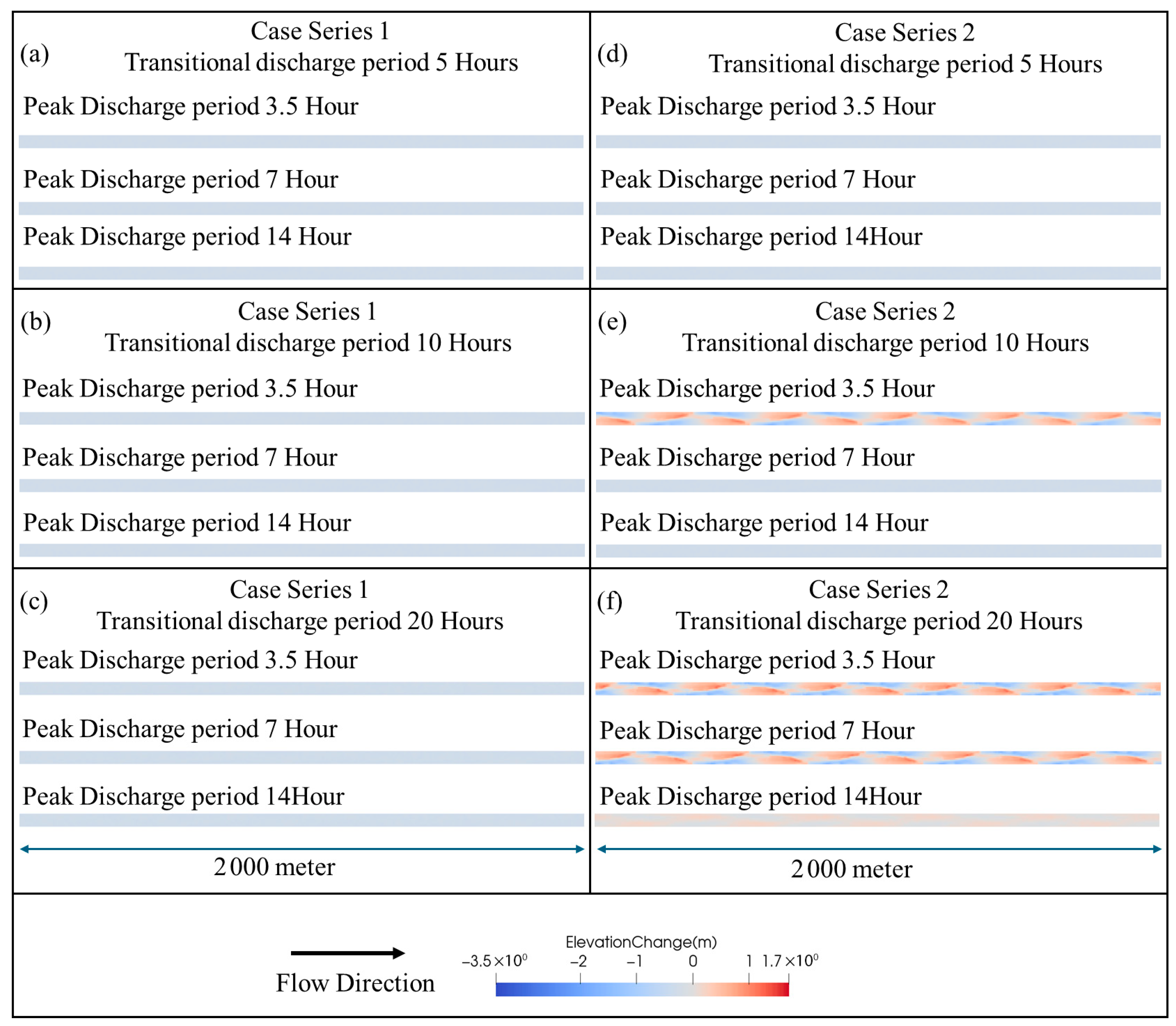

3.5. Case Series 1

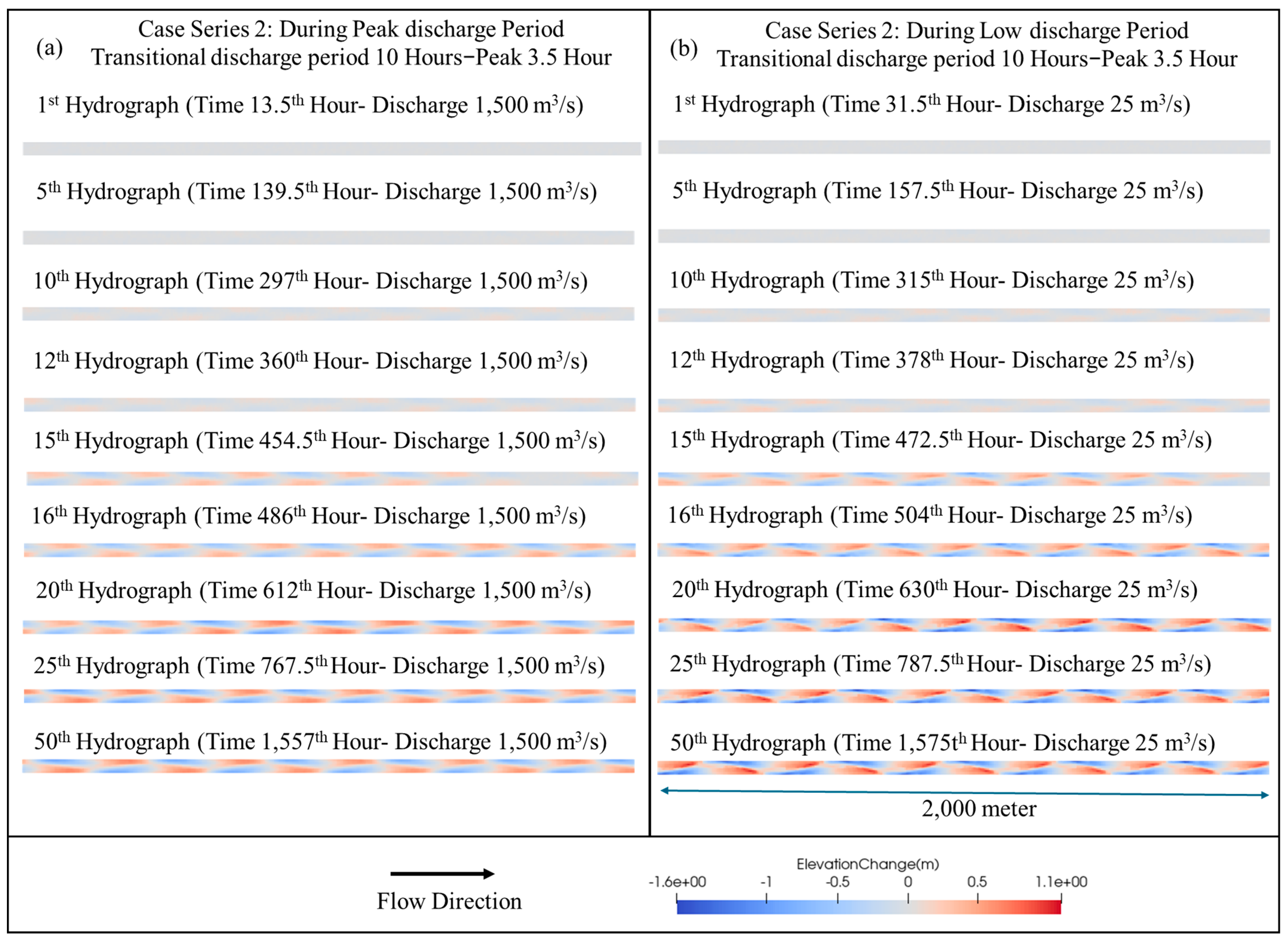

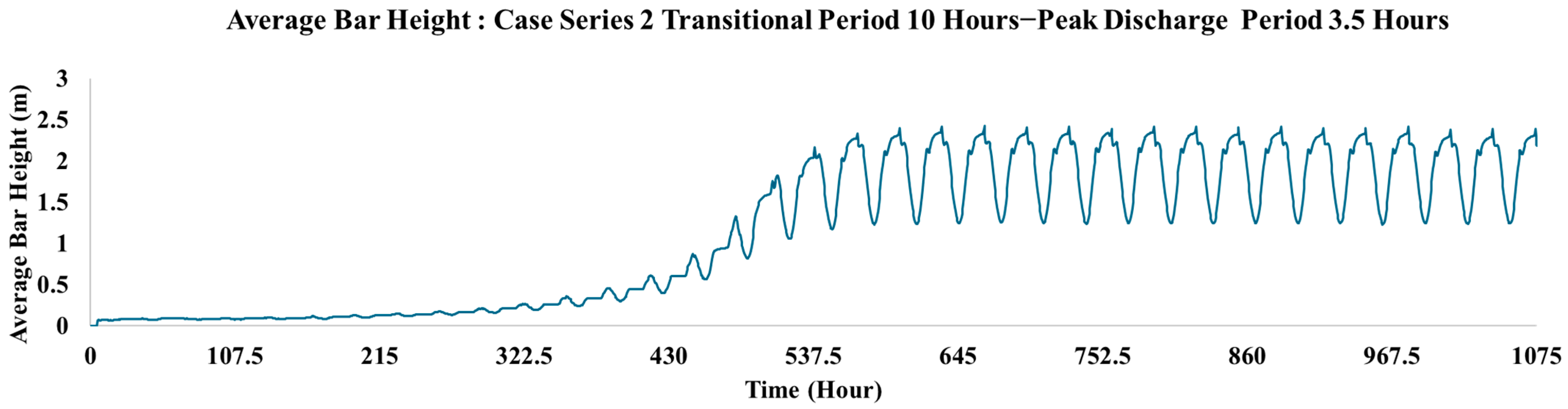

3.6. Case Series 2

4. Discussion

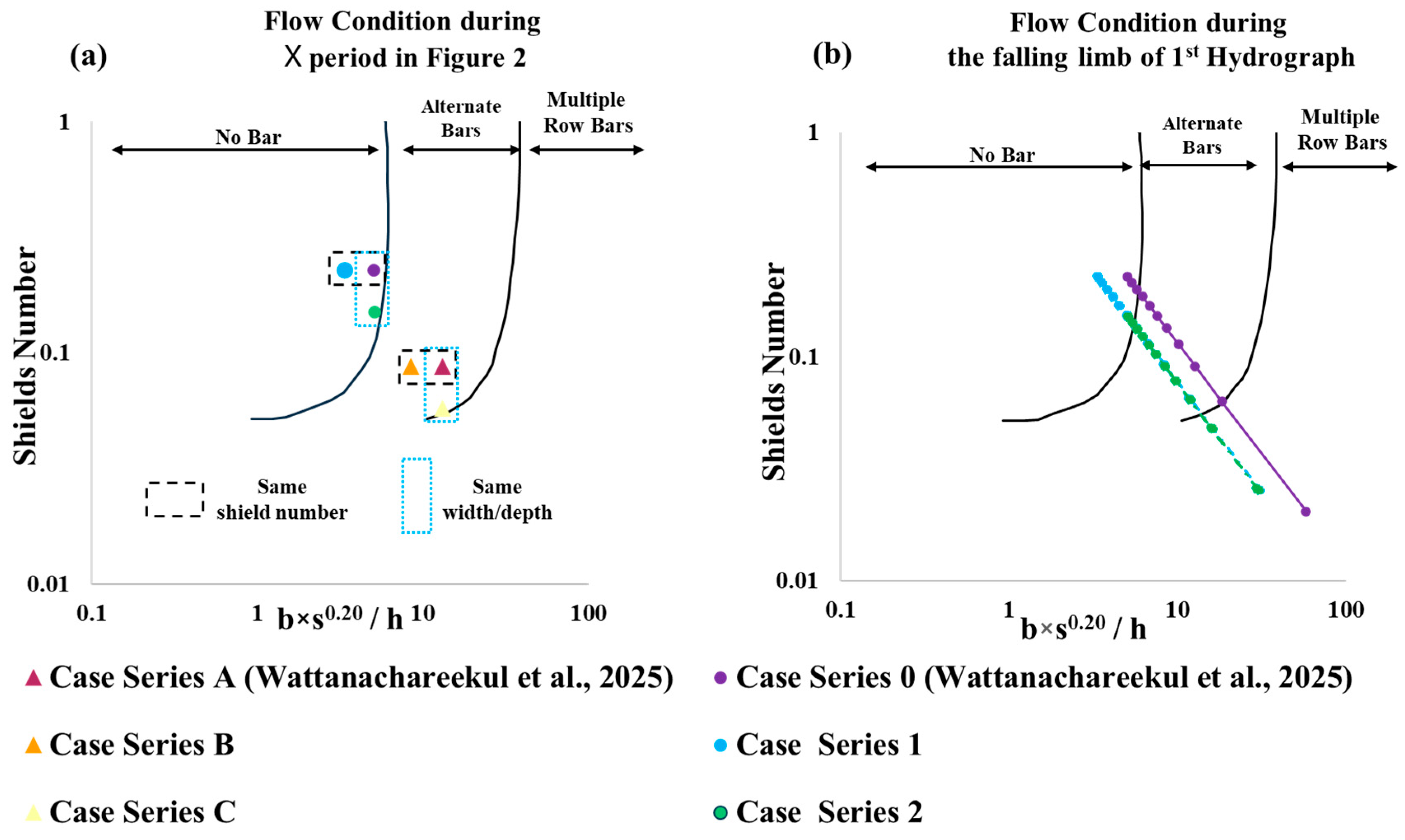

4.1. Similar Shields Number Condition

4.2. Similar Half of Width-to-Depth Ratio Condition

4.3. Implication from This Study

4.4. Recommendation for Further Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| iRIC | International River Interface Cooperative |

Appendix A

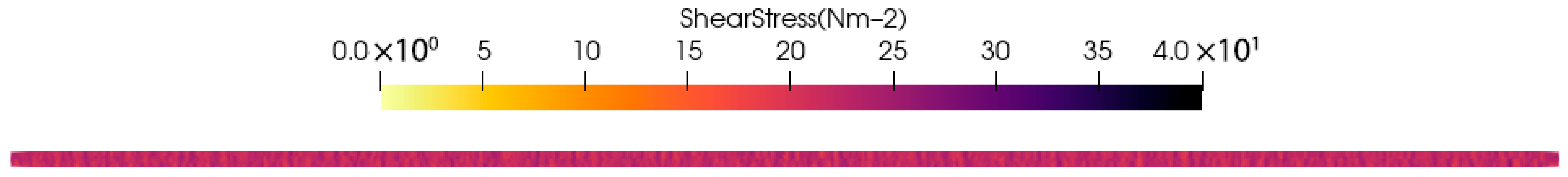

Appendix A.1. The Shear Stress During Low Discharge (25 m3/s)

Appendix A.2. The Alternate Bar Morphology of Case Series B and C

Appendix B

The Dynamic of Alternate Bar Morphology of Case Series 2 with Transitional Discharge Period 10 h–Peak 3.5 h

References

- Francalanci, S.; Solari, L.; Toffolon, M.; Parker, G. Do Alternate Bars Affect Sediment Transport and Flow Resistance in Gravel-Bed Rivers? Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2012, 37, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancey, C.; Recking, A. Scaling Behavior of Bedload Transport: What If Bagnold Was Right? Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 246, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude, N.; Rodrigues, S.; Bustillo, V.; Bréhéret, J.-G.; Tassi, P.; Jugé, P. Interactions between Flow Structure and Morphodynamic of Bars in a Channel Expansion/Contraction, Loire River, France. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 2850–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Mishra, J.; Kato, K.; Sumner, T.; Shimizu, Y. Supplied Sediment Tracking for Bridge Collapse with Large-Scale Channel Migration. Water 2020, 12, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Johnson, J.P.L.; Dempo, J.; Mishra, J. Ratio of River Channel Bar to Bank Height Sets Bank Erosion Rate. JGR Earth Surf. 2025, 130, e2024JF007965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Johnson, J.P. Morphological and Sediment Supply Controls on Lateral Bedrock Channel Erosion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL113436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duró, G.; Crosato, A.; Tassi, P. Numerical Study on River Bar Response to Spatial Variations of Channel Width. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 93, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Deng, J.; Xiong, H.; Li, D. Mechanisms of Bar Adjustments in the Jingjiang Reach of the Yangtze River in Response to the Operation of the Three Gorges Dam. J. Hydrol. 2023, 616, 128802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaballah, M.; Camenen, B.; Pénard, L.; Paquier, A. Alternate Bar Development in an Alpine River Following Engineering Works. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 81, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google LLC. Google Earth Pro, version 7.3.6; Google LLC: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2025.

- Colombini, M.; Seminara, G.; Tubino, M. Finite-Amplitude Alternate Bars. J. Fluid Mech. 1987, 181, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielen, R.; Doelman, A.; de Swart, H.E. On the Nonlinear Dynamics of Free Bars in Straight Channels. J. Fluid Mech. 1993, 252, 325–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosato, A.; Mosselman, E. An Integrated Review of River Bars for Engineering, Management and Transdisciplinary Research. Water 2020, 12, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmari, H.; Da Silva, A.M.F. Regions of Bars, Meandering and Braiding in Da Silva and Yalin’s Plan. J. Hydraul. Res. 2011, 49, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, M.; Kishi, T. Regime Criteria on Bars and Braids in Alluvial Straight Channels. Proc. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1984, 1984, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, P.A.; Morgan, J.A. Flume Experiments on Flow and Sediment Supply Controls on Gravel Bedform Dynamics. Geomorphology 2018, 323, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Iwasaki, T.; Yamada, T.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Shimizu, Y. Morphodynamic Equilibrium of Alternate Bar Dynamics under Repeated Hydrographs. Adv. Water Resour. 2023, 175, 104427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanachareekul, P.; Inoue, T.; Uchida, T.; Kido, R. The Effect of the Alteration in Flow Discharge on the Development of the Alternate Bar. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2025, 19, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, M.; Yasuda, H. On the Migrating Speed of Free Alternate Bars. JGR Earth Surf. 2022, 127, e2021JF006485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Cao, Z.; Liu, H.; Pender, G. Numerical Modelling of Alternate Bar Formation, Development and Sediment Sorting in Straight Channels. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2017, 42, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankert, A.R.; Nelson, P.A. Alternate Bar Dynamics in Response to Increases and Decreases of Sediment Supply. Sedimentology 2018, 65, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, F.; Tassi, P.; Claude, N.; Crosato, A.; Rodrigues, S.; Pham Van Bang, D. Numerical Study of Alternate Bars in Alluvial Channels with Nonuniform Sediment. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 2976–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, Z.; He, Y.; Yu, G.A.; Yao, W. Morphological Adjustments of Alternate Bars in a Channelized River of the Tibetan Plateau and Their Hydro-sedimentary Implications. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2025, 50, e70141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Brousse, G.; Jodeau, M. Gravel Replenishment Downstream of Dams: Insights from a Flume Experiment in a Straight Embanked Channel. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR037928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.-L.; Shimizu, Y. Numerical Simulations of the Behavior of Alternate Bars with Different Bank Strengths. J. Hydraul. Res. 2005, 43, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redolfi, M.; Carlin, M.; Tubino, M. The Impact of Climate Change on River Alternate Bars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, W.; Siviglia, A.; Tettamanti, S.; Toffolon, M.; Vetsch, D.; Francalanci, S. Modeling Vegetation Controls on Fluvial Morphological Trajectories. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 7167–7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertagni, M.B.; Perona, P.; Camporeale, C. Parametric Transitions between Bare and Vegetated States in Water-Driven Patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8125–8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serlet, A.J.; Gurnell, A.M.; Zolezzi, G.; Wharton, G.; Belleudy, P.; Jourdain, C. Biomorphodynamics of Alternate Bars in a Channelized, Regulated River: An Integrated Historical and Modelling Analysis. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 43, 1739–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponi, F.; Koch, A.; Bertoldi, W.; Vetsch, D.F.; Siviglia, A. When Does Vegetation Establish on Gravel Bars? Observations and Modeling in the Alpine Rhine River. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Luna, A.; Duró, G.; Crosato, A.; Uijttewaal, W. Morphological Adaptation of River Channels to Vegetation Establishment: A Laboratory Study. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2019, 124, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, C.; Claude, N.; Tassi, P.; Cordier, F.; Antoine, G. Morphodynamics of Alternate Bars in the Presence of Riparian Vegetation. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 1100–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvani, G.; Francalanci, S.; Solari, L. Insights Into the Dynamics of Vegetated Alternate Bars by Means of Flume Experiments. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR032536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanachareekul, P.; Inoue, T.; Johnson, J.P.L. Modeling the Effects of Vegetation Growth Rate on the Dynamics of Alternate Bars. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2025, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Shimizu, Y.; Abe, T.; Asahi, K.; Gamou, M.; Inoue, T.; Iwasaki, T.; Kakinuma, T.; Kawamura, S.; Kimura, I.; et al. The International River Interface Cooperative: Public Domain Flow and Morphodynamics Software for Education and Applications. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 93, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Nelson, J.; Arnez Ferrel, K.; Asahi, K.; Giri, S.; Inoue, T.; Iwasaki, T.; Jang, C.-L.; Kang, T.; Kimura, I.; et al. Advances in Computational Morphodynamics Using the International River Interface Cooperative (iRIC) Software. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recking, A.; Frey, P.; Paquier, A.; Belleudy, P.; Champagne, J.-Y. Feedback between Bed Load Transport and Flow Resistance in Gravel and Cobble Bed Rivers. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W05412, Erratum in Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W08701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashida, K.; Michiue, M. Study on Hydraulic Resistance and Bed-Load Transport Rate in Alluvial Streams. Proc. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1972, 1972, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, K. Universal Bank Erosion Coefficient for Meandering Rivers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1989, 115, 744–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Kimura, I. Sensitivity of Free Bar Morphology in Rivers to Secondary Flow Modeling: Linear Stability Analysis and Numerical Simulation. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 92, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Mishra, J.; Parker, G. Numerical Simulations of Meanders Migrating Laterally as They Incise Into Bedrock. JGR Earth Surf. 2021, 126, e2020JF005645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Iwasaki, T.; Parker, G.; Shimizu, Y.; Izumi, N.; Stark, C.P.; Funaki, J. Numerical Simulation of Effects of Sediment Supply on Bedrock Channel Morphology. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2016, 142, 04016014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, A.C.; Potts, D.F. Analysis of Flow Competence in an Alluvial Gravel Bed Stream, Dupuyer Creek, Montana. Water Resour. Res. 2007, 43, W07433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Peter, E.; Müller, R. Formulas for Bed-Load Transport. 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Redolfi, M.; Welber, M.; Carlin, M.; Tubino, M.; Bertoldi, W. Morphometric Properties of Alternate Bars and Water Discharge: A Laboratory Investigation. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2020, 8, 789–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Dynamics of Braided Rivers. In River Dynamics: Geomorphology to Support Management; Rhoads, B.L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 234–251. ISBN 978-1-107-19542-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.-H.; Wang, L.-L.; Tang, K.-M.; Luo, R.-T.; Zhang, X.C. Effects of Sediment Size on Transport Capacity of Overland Flow on Steep Slopes. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2011, 56, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Series A [18] | Case Series B | Case Series C | Case Series 0 [18] | Case Series 1 | Case Series 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel width (m) | 60 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 40 | 40 |

| Peak flow discharge (m3/s) | 300 | 200 | 100 | 1500 | 1000 | 500 |

| Low flow discharge (m3/s) | 25 | |||||

| Periods for the peak discharge (h) | 3.5, 7, 14 | |||||

| Periods for the rising and falling limbs (h) | 5, 10, 20 | |||||

| Averaged half of width-to-depth ratio * | 19.07 | 12.67 | 19.07 | 7.29 | 4.83 | 7.29 |

| Averaged shields number * | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.15 |

| Averaged velocity (m/s) * | 3.19 | 3.19 | 2.42 | 6.06 | 6.06 | 4.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wattanachareekul, P.; Inoue, T.; Uchida, T.; Kasagi, Y.; Eguchi, K. Different Alternate Bar Dynamics Under Different Channel Width and Flow Conditions. Water 2025, 17, 3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243494

Wattanachareekul P, Inoue T, Uchida T, Kasagi Y, Eguchi K. Different Alternate Bar Dynamics Under Different Channel Width and Flow Conditions. Water. 2025; 17(24):3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243494

Chicago/Turabian StyleWattanachareekul, Pawat, Takuya Inoue, Tatsuhiko Uchida, Yutaka Kasagi, and Kotomi Eguchi. 2025. "Different Alternate Bar Dynamics Under Different Channel Width and Flow Conditions" Water 17, no. 24: 3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243494

APA StyleWattanachareekul, P., Inoue, T., Uchida, T., Kasagi, Y., & Eguchi, K. (2025). Different Alternate Bar Dynamics Under Different Channel Width and Flow Conditions. Water, 17(24), 3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243494