Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Degradation of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PHACs) in Wastewater: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Ozone-Based AOPs for Water Treatment

2.1. Reaction Mechanism of Ozone-Based AOPs

2.1.1. Oxidation–Reduction Reaction

2.1.2. Cycloaddition Reaction

2.1.3. Electrophilic Substitution Reaction

2.1.4. Nucleophilic Reaction

2.1.5. Indirect Reaction Mechanism

2.2. Ultraviolet Radiation/Ozonation

2.3. Hydrogen Peroxide/Ozonation

2.4. Ultrasonication/Ozonation

2.5. Biological Treatment/Ozonation

3. Effects of Catalysts on Ozonation Degradation of PHACs

3.1. Metallic Oxides

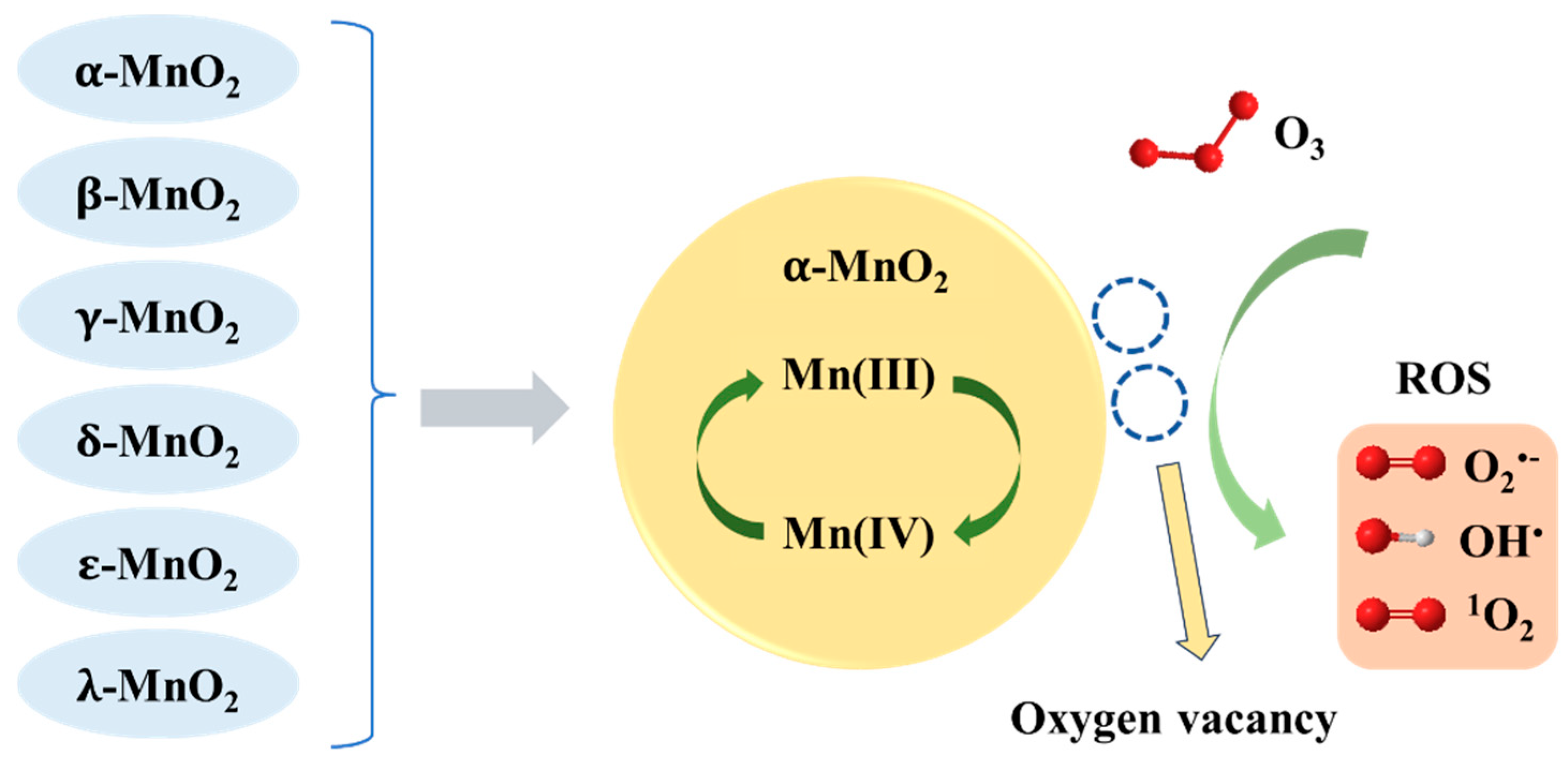

3.1.1. Manganese Oxide

3.1.2. Oxides/Iron Hydroxides

3.1.3. Aluminum Oxides

3.2. Carbon Materials

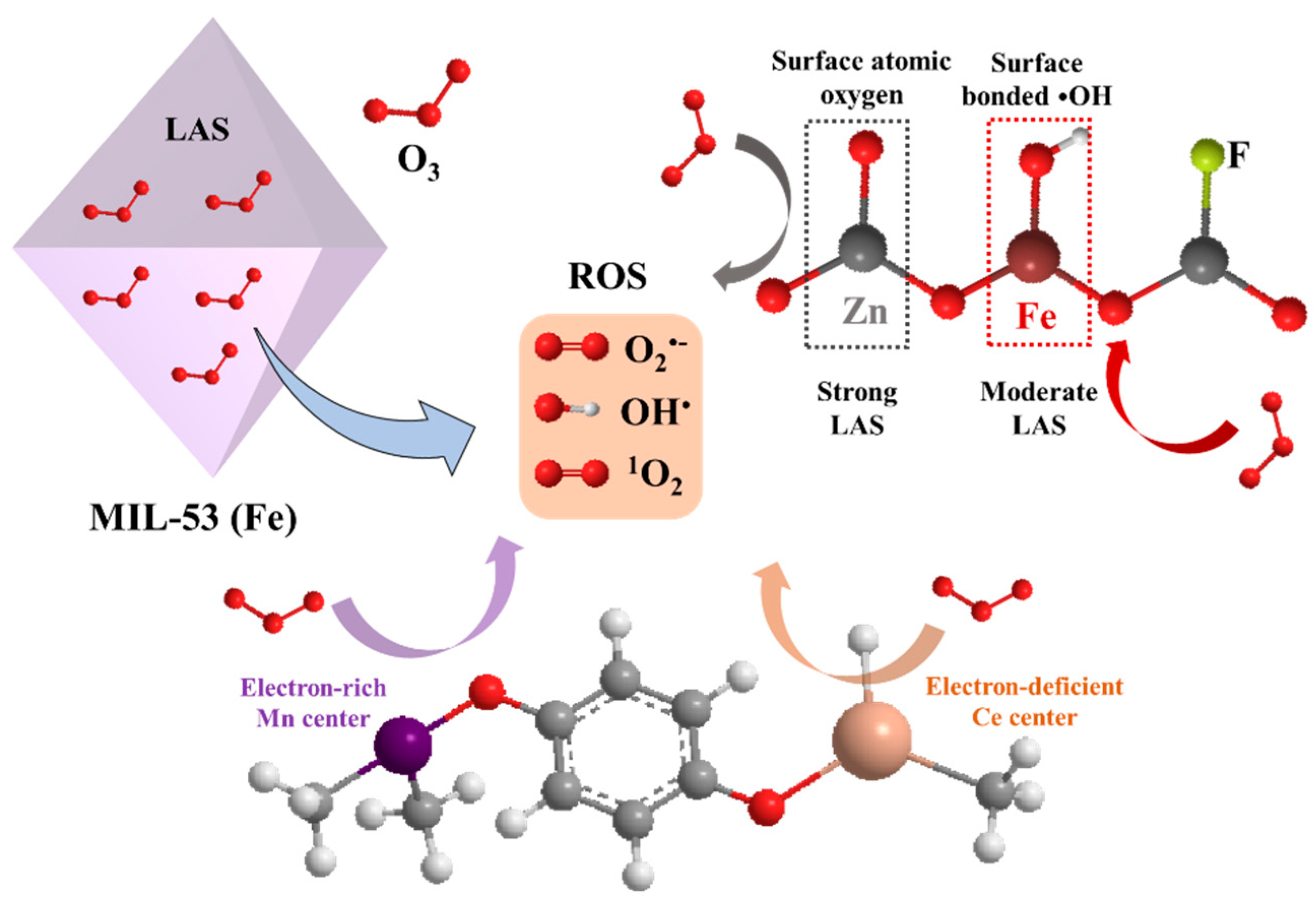

3.3. Metal–Organic Frameworks

3.4. Metal/Metallic Oxides Loaded on Support Materials

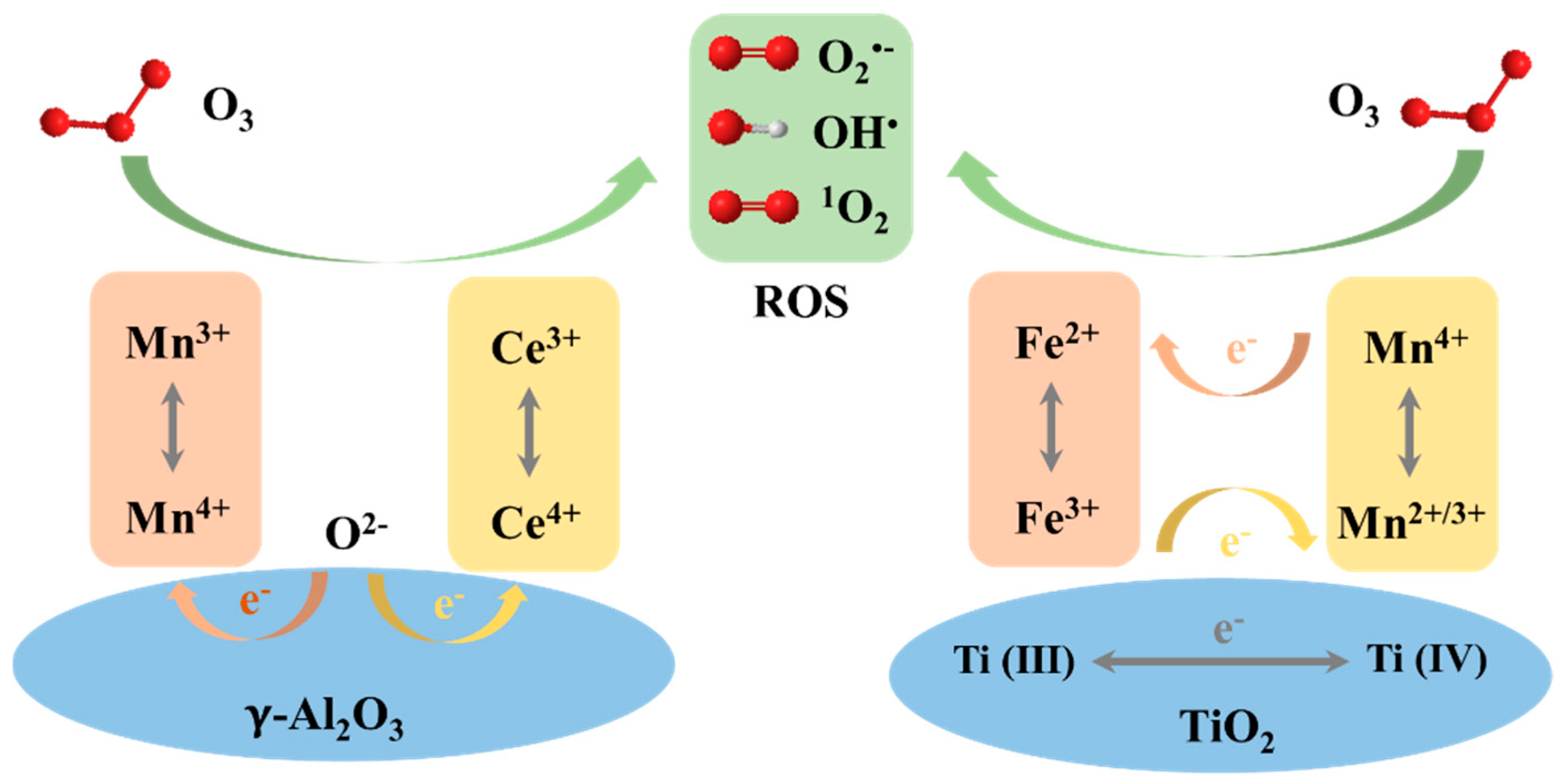

3.4.1. Metallic Oxides as Supports

3.4.2. Carbon Materials as Supports

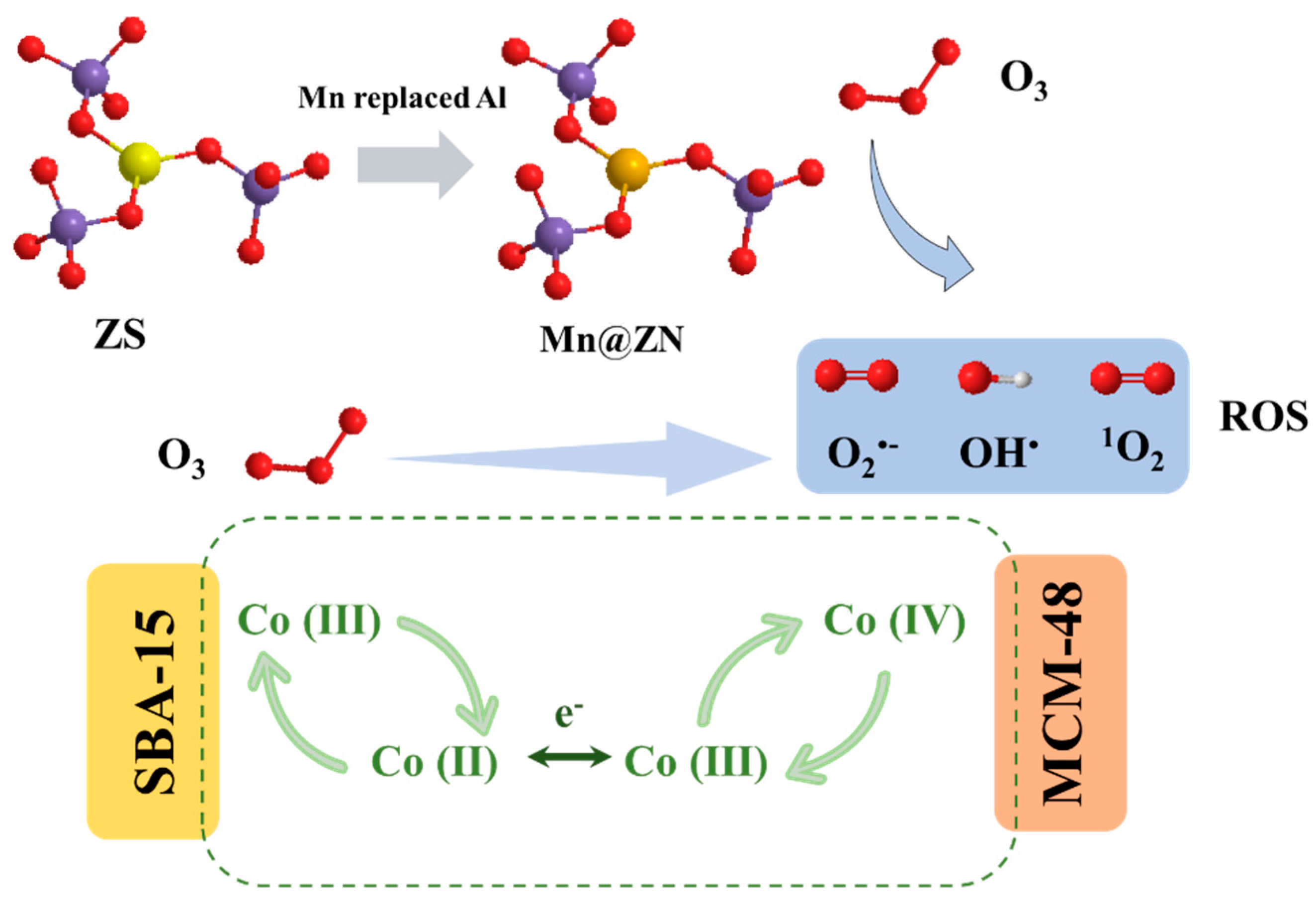

3.4.3. Molecular Sieves as Supports

3.4.4. Membrane Sieves as Supports

4. Methods to Enhance Mass Transfer Efficiency of Ozone in Water

4.1. High-Gravity Rotating Packed Bed

4.2. Hydrodynamic Cavitation Reactor

4.3. Micro–Nano-Bubble Technology

4.4. Membrane Transfer Technology

5. Challenges in Practical Applications

5.1. Catalyst Performance

5.2. Catalyst Separation and Recovery

5.3. Catalyst Regeneration and Reuse

5.4. Removal of Mixed Pollutants

5.5. Dynamic Changes in Solution pH

5.6. Ozone Utilization Efficiency

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valdez-Carrillo, M.; Abrell, L.; Ramírez-Hernández, J.; Reyes-López, J.A.; Carreón-Diazconti, C. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants in the aquatic environment of Latin America: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 44863–44891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.-K.; Lin, C.; Bui, X.-T.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Nguyen, H.-L.; Truong, Q.-M.; Hoang, H.-G.; Tran, H.-T.; Malafaia, G.; Idris, A.M. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceutical pollutants in wastewater: Insights on ecotoxicity, health risk, and state–of–the-art removal. Chemosphere 2024, 354, 141678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, T.A. Occurrence of drugs in German sewage treatment plants and rivers. Water Res. 1998, 32, 3245–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, B.; Camacho-Muñoz, D. Analysis, fate and toxicity of chiral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in wastewaters and the environment: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 43–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, V.; Murugan, S.; Kumaresan, R.; Narayanan, M.; Sillanpää, M.; Viet N Vo, D.; Kushwaha, O.S.; Jenis, P.; Potdar, P.; Gadiya, S. Sustainable adsorbents for the removal of pharmaceuticals from wastewater: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M.; Skrbic, B.; Zivancev, J.; Ferrando-Climent, L.; Barcelo, D. Determination of 81 pharmaceutical drugs by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry with hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap in different types of water in Serbia. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, B.K.; Velayudan, A.; Petrović, M.; Álvarez-Muñoz, D.; Čelić, M.; Oelofse, G.; Colenbrander, D.; le Roux, M.; Ndungu, K.; Madikizela, L.M.; et al. Occurrence and potential hazard posed by pharmaceutically active compounds in coastal waters in Cape Town, South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 174800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Sui, Q.; Xu, D.; Yu, G. Seasonal occurrence and source analysis of pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) in aquatic environment in a small and medium-sized city, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolini, M. Toxicity of the Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol, diclofenac, ibuprofen and naproxen towards freshwater invertebrates: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Nuzhat, S.; Chowdhury, A.T.; Rafa, N.; Uddin, M.A.; Inayat, A.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Ong, H.C.; Chia, W.Y.; et al. Recent developments in physical, biological, chemical, and hybrid treatment techniques for removing emerging contaminants from wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataee, A.; Arefi-Oskoui, S.; Fathinia, M.; Fazli, A.; Hojaghan, A.S.; Hanifehpour, Y.; Joo, S.W. Photocatalysis of sulfasalazine using Gd-doped PbSe nanoparticles under visible light irradiation: Kinetics, intermediate identification and phyto-toxicological studies. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 30, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhao, H.; Xie, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species and Catalytic Active Sites in Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Water Purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 5931–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, G.A.; Devrajani, S.K.; Memon, S.A.; Qureshi, S.S.; Anbuchezhiyan, G.; Mubarak, N.M.; Shamshuddin, S.Z.M.; Siddiqui, M.T.H. Holistic insight mechanism of ozone-based oxidation process for wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2024, 359, 142303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. Reactive species in advanced oxidation processes: Formation, identification and reaction mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M.; Das, I.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Blaney, L. Advanced oxidation processes: Performance, advantages, and scale-up of emerging technologies. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelle, E.I.; Macfarlane, A.; Cusack, M.; Burns, A.; Okolie, J.A.; Mackay, W.; Rateb, M.; Yaseen, M. Ozone application in different industries: A review of recent developments. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Chang, J.; Ding, J.; Yin, Y. Impact of coexisting components on the catalytic ozonation of emerging contaminants in wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H. Catalytic ozonation for water and wastewater treatment: Recent advances and perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, J. Catalytic ozonation of sulfamethoxazole over Fe3O4/Co3O4 composites. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Quan, X.; Chen, S.; Yu, H.; Liu, G. Enhanced catalytic ozonation by highly dispersed CeO2 on carbon nanotubes for mineralization of organic pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 368, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Liang, L.; Cao, P.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Yu, H.; Quan, X. MgAl2O4 incorporated catalytic ceramic membrane for catalytic ozonation of organic pollutants. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 343, 123527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Yuan, R.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B.; Luo, S. Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation for the removal of antibiotics in water: A review. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, T.; Yin, M.; Chen, S.; Ouyang, C.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X. Single-Atom Fe-N4 Sites for Catalytic Ozonation to Selectively Induce a Nonradical Pathway toward Wastewater Purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3623–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-L. Homogeneous catalytic ozonation of C.I. Reactive Red 2 by metallic ions in a bubble column reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, G.; Feng, H.; Miao, X.; Zhou, S.; Wang, D.; Huang, L.; Wang, K. Preparation of sludge-based materials and their environmentally friendly applications in wastewater treatment by heterogeneous oxidation technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W.; Ervin, K.M. Anharmonicity and bond angle of matrix-isolated ozone. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1981, 88, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Xu, L.J. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment: Formation of Hydroxyl Radical and Application. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 42, 251–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisgen, R. Cycloaddition—Definition, Classification, and Characterization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1968, 7, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criegee, R. Mechanism of Ozonlysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1975, 14, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Miao, J.; Li, X.; Xu, W. Cycloaddition of ozone to allyl alcohol, acrylic acid and allyl aldehyde: A comparative DFT study. Chem. Phys. 2013, 415, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekle-Röttering, A.; von Sonntag, C.; Reisz, E.; Eyser, C.v.; Lutze, H.V.; Türk, J.; Naumov, S.; Schmidt, W.; Schmidt, T.C. Ozonation of anilines: Kinetics, stoichiometry, product identification and elucidation of pathways. Water Res. 2016, 98, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoigné, J.; Bader, H. Rate constants of reactions of ozone with organic and inorganic compounds in water—I: Non-dissociating organic compounds. Water Res. 1983, 17, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebel, A.H.; Erickson, R.E.; Abshire, C.J.; Bailey, P.S. Ozonation of Carbon-Nitrogen Double Bonds. I. Nucleophilic Attack of Ozone1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Niu, Q.; Wu, S.; Lin, Y.; Biswas, J.K.; Yang, C. Hydroxyl radicals in ozone-based advanced oxidation of organic contaminants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 3059–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlinskii, B.Y.; Altshuler, H.N. Ozonolysis of isoquinoline in a polystyrene-based sulfonate cation exchanger. Coke Chem. 2017, 60, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, W.; Roddick, F.; Porter, N. Formation of hazardous by-products resulting from the irradiation of natural organic matter: Comparison between UV and VUV irradiation. Chemosphere 2006, 63, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratpukdi, T.; Siripattanakul, S.; Khan, E. Mineralization and biodegradability enhancement of natural organic matter by ozone–VUV in comparison with ozone, VUV, ozone–UV, and UV: Effects of pH and ozone dose. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3531–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeb, M.B.; Criquet, J.; Zimmermann-Steffens, S.G.; von Gunten, U. Oxidative treatment of bromide-containing waters: Formation of bromine and its reactions with inorganic and organic compounds—A critical review. Water Res. 2014, 48, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X. O3 and UV/O3 oxidation of organic constituents of biotreated municipal wastewater. Water Res. 2008, 42, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Feng, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, T. Degradation of sodium n-butyl xanthate by vacuum UV-ozone (VUV/O3) in comparison with ozone and VUV photolysis. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 102, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chi, H.; He, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Ma, J. Efficient removal of halogenated phenols by vacuum-UV system through combined photolysis and OH oxidation: Efficiency, mechanism and economic analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Song, Y.; Chang, F.; Wang, K. Evaluation of chemistry and key reactor parameters for industrial water treatment applications of the UV/O3 process. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Sun, D. Degradation characteristics of refractory organic matter in naproxen pharmaceutical secondary effluent using vacuum ultraviolet–ozone treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Bai, C.-W.; Huang, X.-T.; Sun, Y.-J.; Chen, X.-J. Ozone meets peroxides: A symphony of hybrid techniques in wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merényi, G.; Lind, J.; Naumov, S.; Sonntag, C. Reaction of Ozone with Hydrogen Peroxide (Peroxone Process): A Revision of Current Mechanistic Concepts Based on Thermokinetic and Quantum-Chemical Considerations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3505–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, A.; von Sonntag, J.; von Sonntag, C.; Schmidt, T.C. The •OH Radical Yield in the H2O2 + O3 (Peroxone) Reaction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 9959–9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Kang, J.; Yan, P.; Shen, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, X.; Tan, Q.; Shen, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, S. Surface oxygen vacancies prompted the formation of hydrated hydroxyl groups on ZnOx in enhancing interfacial catalytic ozonation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 341, 123325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, S.; Kumar Ponnusamy, V.; Ashokkumar, M. A review on hybrid techniques for the degradation of organic pollutants in aqueous environment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 67, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıdak, R.; Doğan, Ş. Medium-high frequency ultrasound and ozone based advanced oxidation for amoxicillin removal in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 40, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekhate, C.V.; Srivastava, J.K. Recent advances in ozone-based advanced oxidation processes for treatment of wastewater- A review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 3, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.P.; Dhara, S.; Samanta, N.S.; Purkait, M.K. Advancements on ozonation process for wastewater treatment: A comprehensive review. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2024, 202, 109852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.; Kim, T.; Jeon, H.; Lee, G.; Jung, S.; Seo, S.; Jang, A. Pilot scale application of a hybrid process based on ozone and BAF process: Performance evaluation for livestock wastewater treatment in a real environment. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 66, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onesios, K.M.; Yu, J.T.; Bouwer, E.J. Biodegradation and removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in treatment systems: A review. Biodegradation 2009, 20, 441–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gijn, K.; van Dam, M.R.H.P.; de Wilt, H.A.; de Wilde, V.; Rijnaarts, H.H.M.; Langenhoff, A.A.M. Removal of micropollutants and ecotoxicity during combined biological activated carbon and ozone (BO3) treatment. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Tian, Q.; Yang, R.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Q.; Fang, G. Ozone/biological aerated filter integrated process for recycled paper mill wastewater: A pilot-scale study. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 211, 109466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollice, A.; Laera, G.; Cassano, D.; Diomede, S.; Pinto, A.; Lopez, A.; Mascolo, G. Removal of nalidixic acid and its degradation products by an integrated MBR-ozonation system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 203–204, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancheros, J.C.; Madera-Parra, C.A.; Caselles-Osorio, A.; Torres-López, W.A.; Vargas-Ramírez, X.M. Ibuprofen and Naproxen removal from domestic wastewater using a Horizontal Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetland coupled to Ozonation. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 135, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Du, P.; Zhou, B.; Meng, F.; Wei, C.; Zhou, L.; Wen, G.; Wang, Y. Manganese oxide catalytic materials for degradation of organic pollutants in advanced oxidation processes: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 66, 106048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, W.; Si, W.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. A novel γ-like MnO2 catalyst for ozone decomposition in high humidity conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.; Cao, H.; Xie, Y.; Xiao, J.; Chen, Y.; Ghazi, Z.A. Selection of active phase of MnO2 for catalytic ozonation of 4-nitrophenol. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Shen, B.; Wei, J.; Zeng, P.; Wen, X. Catalytic ozonation for metoprolol and ibuprofen removal over different MnO2 nanocrystals: Efficiency, transformation and mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzany Janet, D.L.C.; Rodríguez Santillán, J.L.; Fuentes, I.; Tiznado, H.; Vazquez-Arce, J.L.; Romero-Ibarra, I.; Guzmán, C.J.I.; Gutiérrez, H.M. Effect of crystalline phase of MnO2 on the degradation of Bisphenol A by catalytic ozonation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, X.; Sans, C. Insights into the role of β-MnO2 and oxalic acid complex expediting ozonation: Structural properties and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 341, 126904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.-P.; Liu, W.-P.; Leng, W.-H.; Zhang, Q.-Q. Characteristics of MnO2 catalytic ozonation of sulfosalicylic acid and propionic acid in water. Chemosphere 2003, 50, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.-X.; Luo, K.; Wang, Y.-F.; Zhao, S.-J.; Zhang, X. Synthesis of petal-like δ-MnO2 and its catalytic ozonation performance. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 6770–6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelalak, R.; Alizadeh, R.; Ghareshabani, E. Enhanced heterogeneous catalytic ozonation of pharmaceutical pollutants using a novel nanostructure of iron-based mineral prepared via plasma technology: A comparative study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 392, 122269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelalak, R.; Heidari, Z.; Alizadeh, R.; Ghareshabani, E.; Nasseh, N.; Marjani, A.; Albadarin, A.B.; Shirazian, S. Efficient oxidation/mineralization of pharmaceutical pollutants using a novel Iron (III) oxyhydroxide nanostructure prepared via plasma technology: Experimental, modeling and DFT studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oputu, O.; Chowdhury, M.; Nyamayaro, K.; Fatoki, O.; Fester, V. Catalytic activities of ultra-small β-FeOOH nanorods in ozonation of 4-chlorophenol. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 35, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari, G.; Salari, M.; Faraji, H. Performance of heterogeneous catalytic ozonation process using Al2O3 nanoparticles in dexamethasone removal from aqueous solutions. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 189, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati Sani, O.; Fezabady, A.A.N.; Yazdani, M.; Taghavi, M. Catalytic ozonation of ciprofloxacin using γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles in synthetic and real wastewaters. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 32, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehmeidani, M.; Mahnaee, S.; Ghaedi, M.; Heidari, H.; Roy, V. Carbon based materials: A review of adsorbents for inorganic and organic compounds. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 598–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijer, K.; Björlenius, B.; Shaik, S.; Lindberg, R.H.; Brunström, B.; Brandt, I. Removal of pharmaceuticals and unspecified contaminants in sewage treatment effluents by activated carbon filtration and ozonation: Evaluation using biomarker responses and chemical analysis. Chemosphere 2017, 176, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, B.; Ianes, J.; Bertolo, B.; Ziccardi, S.; Maffini, F.; Antonelli, M. Adsorption on activated carbon combined with ozonation for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern in drinking water. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 350, 119537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.G.; Órfão, J.J.M.; Pereira, M.F.R. Catalytic ozonation of sulphamethoxazole in the presence of carbon materials: Catalytic performance and reaction pathways. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 239–240, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orge, C.A.; Graça, C.A.L.; Restivo, J.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Soares, O.S.G.P. Catalytic ozonation of pharmaceutical compounds using carbon-based catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2024, 187, 106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeguer Esquerdo, A.; Sentana Gadea, I.; Varo Galvañ, P.J.; Prats Rico, D. Efficacy of atrazine pesticide reduction in aqueous solution using activated carbon, ozone and a combination of both. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 144301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Polo, M.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Prados-Joya, G.; Ferro-García, M.A.; Bautista-Toledo, I. Removal of pharmaceutical compounds, nitroimidazoles, from waters by using the ozone/carbon system. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4163–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Restivo, J.; Órfão, J.J.M.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Lapkin, A.A. The role of multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) in the catalytic ozonation of atrazine. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 241, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Sun, H.; Xiao, J.; Cao, H.; Wang, S. Efficient Catalytic Ozonation over Reduced Graphene Oxide for p-Hydroxylbenzoic Acid (PHBA) Destruction: Active Site and Mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 9710–9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Hou, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, J.; Nan, J.; Li, T. Recent advances in the application of metal organic frameworks using in advanced oxidation progresses for pollutants degradation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 5013–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, B.; Nabavi, S.R.; Ghani, M. Magnetic nanohybrid derived from MIL-53(Fe) as an efficient catalyst for catalytic ozonation of cefixime and process optimization by optimal design. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 177, 1054–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Wu, M.; Hu, Q.; Wang, L.; Lv, C.; Zhang, L. Iron-based metal-organic frameworks as novel platforms for catalytic ozonation of organic pollutant: Efficiency and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 367, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebali, H.; Moussavi, G.; Karimi, M.; Giannakis, S. Catalytic ozonation of Acetaminophen with a magnetic, Cerium-based Metal-Organic framework as a novel, easily-separable nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 434, 134614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, W.; Liu, D.; Liao, G.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Li, L. Enhancing water purification through F and Zn-modified Fe-MCM-41 catalytic ozonation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebali, H.; Moussavi, G.; Karimi, M.; Giannakis, S. Development of a magnetic Ce-Zr bimetallic MOF as an efficient catalytic ozonation mediator: Preparation, characterization, and catalytic activity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 315, 123670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, L. Efficient catalytic ozonation for ibuprofen through electron-deficient/rich centers over cerium-manganese doped carbon. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 334, 126013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Pan, J.; Gao, B.; Yue, Q. Catalytic ozonation performance and mechanism of Mn-CeOx@γ-Al2O3/O3 in the treatment of sulfate-containing hypersaline antibiotic wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; He, C.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J. Catalytic ozonation of atenolol by Mn-Ce@Al2O3 catalysts: Efficiency, mechanism and degradation pathways. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, J.; Hu, C.; Zhang, L. Enhanced mineralization of pharmaceuticals by surface oxidation over mesoporous γ-Ti-Al 2O3 suspension with ozone. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 202, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, Z.; Liao, X.; Liu, X.; Gao, M.; Zhang, H.; Zou, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, B.; Yang, Z. Catalytic ozonation performance and mechanisms of Cu-Co/γ-Al2O3 to achieve antibiotics and ammonia simultaneously removal in aquaculture wastewater. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 191, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, N.; Deng, S.-H.; He, H.; Hu, J. Ferromanganese oxide-functionalized TiO2 for rapid catalytic ozonation of PPCPs through a coordinated oxidation process with adjusted composition and strengthened generation of reactive oxygen species. Water Res. 2024, 258, 121813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zong, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lei, Z.; Wu, D. High-efficient M-NC single-atom catalysts for catalytic ozonation in water purification: Performance and mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Qian, M.; Pan, J.; Ding, J.; Guan, B. Amino-functionalized synthesis of MnO2-NH2-GO for catalytic ozonation of cephalexin. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 256, 117797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.; Xing, S.; Sheng, L.; Huang, S.; Guo, H. Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation of ciprofloxacin in water with carbon nanotube supported manganese oxides as catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 227–228, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Wei, J.; Song, Y.; Ren, Y.; Xu, D.; Lai, B. Catalytic ozonation of penicillin G using cerium-loaded natural zeolite (CZ): Efficacy, mechanisms, pathways and toxicity assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Liang, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, R.; Li, L. Degradation of clofibric acid by ozonation assisted by Co-Ce-SBA-15: Role of interfacial electron migration. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Zhao, P.; Xu, G.; Meng, F.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, L.; Jin, S. High efficiency manganese cobalt spinel structure catalytic ozonation ceramic membrane for In Situ BPA degradation and membrane fouling elimination. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; An, S.; Jho, E.H.; Bae, S.; Choi, Y.; Choe, J.K. Exploring reductive degradation of fluorinated pharmaceuticals using Al2O3-supported Pt-group metallic catalysts: Catalytic reactivity, reaction pathways, and toxicity assessment. Water Res. 2020, 185, 116242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares-Reyna, D.; Carrera-Crespo, J.E.; Sosa-Rodríguez, F.S.; Romero-Ibarra, I.C.; Castañeda-Galván, A.A.; Morales-García, S.S.; Vazquez-Arenas, J. Degradation of cefadroxil by photoelectrocatalytic ozonation under visible-light irradiation and single processes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 431, 113995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, E.; Jesus, F.; Alvim, M.; Cotas, C.; Mazierski, P.; Pereira, J.L.; Gomes, J. PPCPs abatement using TiO2-based catalysts by photocatalytic oxidation and ozonation: The effect of nitrogen and cerium loads on the degradation performance and toxicity impact. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 887, 164000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, G. The Role of Functionalization in the Applications of Carbon Materials: An Overview. C-J. Carbon Res. 2019, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, C.; Ma, J.; Yan, C.; Mu, S.; Yu, M. Efficient degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride wastewater by microbubble catalytic ozonation with sludge biochar-loaded layered polymetallic hydroxide. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhuo, Q.; Dai, L.; Guan, B. Mn anchored zeolite molecular nest for enhanced catalytic ozonation of cephalexin. Chemosphere 2023, 335, 139058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Sun, X.; Gu, F.; Zhang, L.; He, H.; Li, L. Mechanism of Synergistic Effect on Electron Transfer over Co-Ce/MCM-48 during Ozonation of Pharmaceuticals in Water. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 23957–23971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, L.; Wei, J.; He, H.; Guo, Z.; Wang, C.; Wen, X.; Song, Y. Progress in ceramic membrane coupling ozonation process for water and wastewater treatment: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.; Davies, S.H.; Alpatova, A.L.; Corneal, L.M.; Baumann, M.J.; Tarabara, V.V.; Masten, S.J. Mn oxide coated catalytic membranes for a hybrid ozonation–membrane filtration: Comparison of Ti, Fe and Mn oxide coated membranes for water quality. Water Res. 2011, 45, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, G.; Voblikova, V.; Sabitova, L.; Tkachenko, I.; Tkachenko, S.; Lunin, V. Ozone Solubility in Water. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Bull. 2015, 70, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Luo, S.; He, Z.; Liu, Y. Applications of high gravity technologies for wastewater treatment: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 912–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Li, Z.; Miao, F.; Shang, R.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, W. Preparation of Mn-FeOX/ZSM-5 by high-gravity method for heterogeneous catalytic ozonation of nitrobenzene. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Shao, S.; Yang, P.; Gao, K.; Liu, Y. Kinetics and mechanism of nitrobenzene degradation by hydroxyl radicals-based ozonation process enhanced by high gravity technology. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Wei, X.; Shao, S.; Liu, Y. Catalytic decomposition and mass transfer of aqueous ozone promoted by Fe-Mn-Cu/γ-Al2O3 in a rotating packed bed. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 45, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Cheng, T.; Wang, L.; Li, K.; Bao, M.; Ma, C.; Nie, K.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, W. Treatment of high-salt phenol wastewater by high-gravity technology intensified Co-Mn/γ-Al2O3 catalytic ozonation: Treatment efficiency, inhibition and catalytic mechanism. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 292, 120019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gągol, M.; Przyjazny, A.; Boczkaj, G. Wastewater treatment by means of advanced oxidation processes based on cavitation—A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 338, 599–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, J.; Bhoi, R.G.; Saharan, V.K. Improved degradation of oseltamivir phosphate, an antiviral drug, through hydrodynamic cavitation based hybrid advanced oxidation processes: An insight into geometrical parameter optimization. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2024, 200, 109796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohod, A.V.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Bagal, M.V.; Gogate, P.R.; Giudici, R. Degradation of organic pollutants from wastewater using hydrodynamic cavitation: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, R.; Yu, S.; Li, L.; Snyder, S.A.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Togbah, C.F.; Gao, N. Micro and nanobubbles-assisted advanced oxidation processes for water decontamination: The importance of interface reactions. Water Res. 2024, 265, 122295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, E.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Jin, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Tian, J. Ultra-high efficient catalytic degradation of BPA by ozone-function microbubble aerated ceramic membrane for water purification. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 54447–54457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Ng, W.J.; Liu, Y. Principle and applications of microbubble and nanobubble technology for water treatment. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Ye, S.; Zou, X.; Fei, R.; Hu, X.; Li, J. High-efficiently utilizing micro-nano ozone bubbles to enhance electro-peroxone process for rapid removal of trace pharmaceutical contaminants from hospital wastewater. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bein, E.; Zucker, I.; Drewes, J.E.; Hübner, U. Ozone membrane contactors for water and wastewater treatment: A critical review on materials selection, mass transfer and process design. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z. Bubbleless membrane contactor for enhanced ozone mass transfer and ozonation for water purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 349, 127823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Gunten, U. Oxidation Processes in Water Treatment: Are We on Track? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5062–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberman, A.; Gozlan, I.; Avisar, D. Pharmaceutical Transformation Products Formed by Ozonation—Does Degradation Occur? Molecules 2023, 28, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Compound | Reaction Conditions | Removal Rate (%) | Mineralization Rate (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-MnO2 | Metoprolol (MET) | [O3] = 0.5 mg/min [Cat.] = 0.20 g/L [C0(MET)] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 30 min pH = 7 | 99.62 | ~38 | [61] |

| β-MnO2 | 4-Chlorobenzoic acid (pCBA) | [O3] = 2 mg/L [Cat.] = 50 mg/L [C0(pCBA)] = 50 mg/L [Time] = 120 min pH = 7 | 90.40 | - | [63] |

| δ-MnO2 | Bisphenol A (BPA) | [O3] = 10 mg/L [Cat.] = 100 mg/L [C0(BPA)] = 50 mg/L [Time] = 20 min pH = 7 | 68.20 | - | [65] |

| γ-MnO2 | Bisphenol A (BPA) | [O3] = 15 ± 0.1 mg/L [Cat.] = 100 mg/L [C0(BPA)] = 50 mg/L [Time] = 120 min pH = 7 | 100 | 51 | [62] |

| α-FeOOH | Sulfasalazine (SSZ) | [O3] = 5 mg/min [Cat.] = 1.5 mg/L [C0(SSZ)] = 10 mg/L [H2O2] = 0.1 mmol/L [Time] = 40 min pH = 7 | 96.05 | 56.69 | [66] |

| FeO/FeOOH | Phenazopyridine (PhP) | [O3] = 15 mg/L [Cat.] = 1.2 g/L [C0(PhP)] = 0.2 mmol/L [Time] = 120 min pH = 6.7 | 98.60 | 80.40 | [67] |

| β-FeOOH | 4-Chlorophenol (4-CP) | [O3] = 0.6 mg/min [Cat.] = 0.1 g/L [C0(4-CP)] = 2 mmol/L [Time] = 40 min pH = 3.5 | 99 | - | [68] |

| Al2O3 | Dexamethasone (DEX) | [O3] = 5 mL/min [Cat.] = 1.0 g/L [C0(DEX)] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 30 min pH = 7 | ~100 | ~60 | [69] |

| γ-Al2O3 | Ciprofloxacin (CPF) | [O3] = 14 mg/min [Cat.] = 0.55 g/L [C0(CPF)] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 60 min pH = 9.5 | 93 | - | [70] |

| Catalyst | Compound | Reaction Conditions | Removal Rate (%) | Mineralization Rate (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | Dimetridazole (DMZ) | [O3] = saturated solution [AC] = 250 mg/L [C0(DMZ)] = 30 mg/L [Time] = 30 min pH = 6 | ~100 | ~25 | [77] |

| MWCNTs | Atrazine (ATZ) | [O3] = 50 mg/min [MWCNTs] = 100 mg/L [C0(ATZ)] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 120 min pH = 5.25 | ~100 | ~80 | [78] |

| MWCNTs | Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) | [O3] = 50 mg/L [MWCNTs] = 100 mg/L [C0(SMX)] = 50 mg/L [Time] = 180 min pH = 6 | ~100 in 30 min | 35 | [74] |

| GAC | Ibuprofen (IBU) | [O3] = 50,000 mg N m−3 [GAC] = 500 mg/L [C0(IBU)] = 20 mg/L [Time] = 180 min | ~100 in 60 min | 81 | [75] |

| rGO | p-Hydroxybenzoic acid (PHBA) | [O3] = 20 mg/L [rGO] = 0.1 g/L [C0(PHBA)] = 20 mg/L [Time] = 60 min pH = 3.5 | ~100 in 30 min | ~90 | [79] |

| Catalyst | Compound | Reaction Conditions | Removal Rate (%) | Mineralization Rate (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4@Ce-UiO-66 | Acetaminophen (ACT) | [O3] = 0.8 mg/min [Cat.] = 0.08 g/L [C0] = 25 mg/L [Time] = 10 min pH = 7 | >99 | 14.1 | [83] |

| Fe3O4/CeZrUiO-66 | Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | [O3] = 200 mL/min [Cat.] = 0.1 g/L [C0] = 30 mg/L [Time] = 60 min pH = 8 | 94 in 30 min | 54 | [85] |

| CeOx/MnOx/C-MOF | Ibuprofen (IBU) | [O3] = 23 mg/h [Cat.] = 0.1 g/L [C0] = 5 mg/L [Time] = 90 min pH = 5 | ~100 | - | [86] |

| CM-500 | Cefixime (CFX) | [O3] = 2.15 mg/min [Cat.] = 0.5 g/L [C0] = 20 mg/L [Time] = 30 min pH = 4 | 97 | 66 | [81] |

| F-Fe-Zn-MCM-41 (FFeZnM) | Ibuprofen (IBU) | [O3] = 50 mg/h [Cat.] = 0.5 g/L [C0] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 120 min pH = 5 | 93.4 in 30 min | 46.6 | [84] |

| Catalyst | Compound | Reaction Conditions | Removal Rate (%) | Mineralization Rate (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-CeOx@γ-Al2O3 | Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | [O3] = 13.96 mg/L [Cat.] = 0.08 g/L [C0] = 50 mg/L [Time] = 120 min pH = 8.5 | ~100 in 40 min | 71.2 | [87] |

| Mn-Ce@Al2O3 | Atenolol (ATL) | [O3] =14.8 mg/L [Cat.] = 0.1 g/L [C0] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 60 min pH = 9.2 | ~100 | 62.8 | [88] |

| γ-Ti-Al2O3 | Ibuprofen (IBU) | [O3] = 30 mg/L [Cat.] = 1.5 g/L [C0] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 60 min pH = 7 | ~100 | ~100 | [89] |

| Cu-Co/Al2O3 | Tetracycline (TC) | [O3] = 30 mg/L [Cat.] = 0.2 g/L [C0] = 100 uM/L [Time] = 30 min pH = 4 | ~100 | - | [90] |

| Ferromanganese oxide (MFOx) MFOx@TiO2 | Ibuprofen (IBU) | [O3] = 15 mg/L [Cat.] = 0.5 g/L [C0] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 30 min pH = 7 | 100% in 10 min | 46 | [91] |

| Cobalt and nitrogen-doped carbon (Co-NC) | Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) | [O3] = 15 mg/L [Cat.] = 0.1 g/L [C0] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 15 min pH = 6.1 | 99.13 | 11.93 | [92] |

| MnO2-NH2-GO | Cefalexin (CLX) | [O3] = 0.12 mg/L [Cat.] = 25 mg/L [C0] = 1 mg/L [Time] = 5 min pH = 6.2 | 50.3 | - | [93] |

| MnOx/MWCNTs | Tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) | [O3] = 0.4 mg/min [Cat.] = 1 g/L [C0] = 30.2 uM/L [Time] = 15 min pH = 7 | >85 | 38.3 | [94] |

| Cerium-loaded natural zeolite (CZ) | Penicillin G (PG) | [O3] = 6 mg/min [Cat.] = 2 g/L [C0] = 50 mg/L [Time] = 20 min pH = 4.5 | ~99.5 | 21.2 | [95] |

| Co-Ce-SBA-15 (SBA: Santa Barbara Amorphous) | Clofibric acid (CA) | [O3] = 50 mg/h [Cat.] = 0.5 g/L [C0] = 10 mg/L [Time] = 90 min pH = 4.5 | 98.7 in 30 min | 58.3 | [96] |

| MCOs-modified ceramic membrane (CCM) | Bisphenol A (BPA) | [O3] = 4 g/h [Cat.] = diameter of 2 cm [C0] = 20 mg/L [Time] = 60 min pH = 6 | 90.6 | - | [97] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X. Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Degradation of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PHACs) in Wastewater: A Review. Water 2025, 17, 3490. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243490

Yang Y, Peng J, Zhang X. Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Degradation of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PHACs) in Wastewater: A Review. Water. 2025; 17(24):3490. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243490

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yifeng, Jianbiao Peng, and Xin Zhang. 2025. "Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Degradation of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PHACs) in Wastewater: A Review" Water 17, no. 24: 3490. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243490

APA StyleYang, Y., Peng, J., & Zhang, X. (2025). Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Degradation of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PHACs) in Wastewater: A Review. Water, 17(24), 3490. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243490