Abstract

Water quality has traditionally been measured via in situ sensors and satellites. The latter has limited applicability for smaller inland water bodies, while the former requires significant logistics, labor, and expense for routine sampling, and reactive/spurious sampling is often not feasible as a result (e.g., sampling pre-/post-storm). Consequently, small uncrewed aircraft system-based (sUAS-based) sampling has emerged as a potential solution to bridge these sampling gaps and challenges. But sampling from an sUAS is complicated by the need to pump water from depth, rather than suspending a sensor from the sUAS, due to concern over sampling sUAS-impacted waters. Here, we measure the water flow below a hovering sUAS in a laboratory by applying the particle image velocimetry flow measurement technique. Observations suggest the development of two counter-rotating vortices under the sUAS, where, in the center of the vortex pair, water is upwelled to the surface, which would, therefore, be a sampling location relatively free of contamination by the sUAS. This location coincides with the still spot on the water surface underneath the sUAS; thus, if one wanted to sample water by suspending a sensor underneath an sUAS, then the optimal sampling location would be within this still spot.

1. Introduction

The health of waterways, terrestrial and marine, impacts human and animal life in a profound way, supporting Earth’s ecosystems by providing an essential element for life on Earth. Although society has recognized the importance of healthy waterways, monitoring, remediation, and assessment of waterways remain a non-trivial task [1]. There still remains no generally accepted, holistic, and practical solution to water quality monitoring [1], much less an economical one.

Water quality has traditionally been monitored by satellite and in situ sensors [2]. In situ measurements are accurate but labor and logistically intensive to maintain over extended periods of time at multiple locations because they can only measure one point at a time (e.g., Ref. [2]). Satellite sensors infer measured quantities, which reduces their accuracy and they are also estimated at a coarse resolution; thus, satellite measurements may offer no help for smaller inland bodies of water. In recent years, small uncrewed aircraft systems (sUAS, widely known as aerial drones) have emerged, particularly as a means to monitor water properties at scales that fill the gap between these two traditional methods. sUASs offer relatively broad spatial coverage at relatively fine resolution at low cost, but the accuracy of such measurements remains uncertain. sUAS-based water sampling would be particularly helpful for water bodies that are difficult to access, when fast mobilization of sampling is needed (e.g., before/after storms), and/or simply anytime labor is a limiting factor for water quality monitoring [3,4]. Since 1980, sUASs have been used to monitor or estimate chemical oxygen demand, total nitrogen, dissolved oxygen, total phosphorus, electrical conductivity, pH, chlorophyll, turbidity, temperature, total suspended solids, and CDOM (colored dissolved organic matter) [5,6]. Pillay et al. [6] show a steep increase in the number of studies using solely sUAS-based data, especially since 2020. Typically, sUAS-based water quality measurements rely on either hyperspectral/imaging methods that collect data using non-invasive (i.e., remote sensing/imaging) methods [6,7,8] or use pumps and water bottles to collect samples that are either processed on-board and discarded, or stored on-board for subsequent analysis [3,9,10]. For the former, water properties are inferred and require calibrations to ensure the inferred water properties are accurate. The latter approach stems from concern that the sUAS presence and operation may affect or “contaminate” the measurements, so water must be pumped up to the sUAS from well below the surface (typically > 1 m). By contamination, we simply mean that the water’s properties have been impacted in some way by the presence of the sUAS. The weight of the payload due to the pump, sampling sensor, and stored (or flow-through) water makes the requirements for the sUAS mission much more demanding [5,11]. Discrepancies, especially in chemical composition, have been observed between sUAS-based water quality measurements and in situ measurements [3,9], which begs the question of whether the discrepancies stem from sUAS-based contamination of the sampled water and/or inaccuracies of hyperspectral/imaging methods.

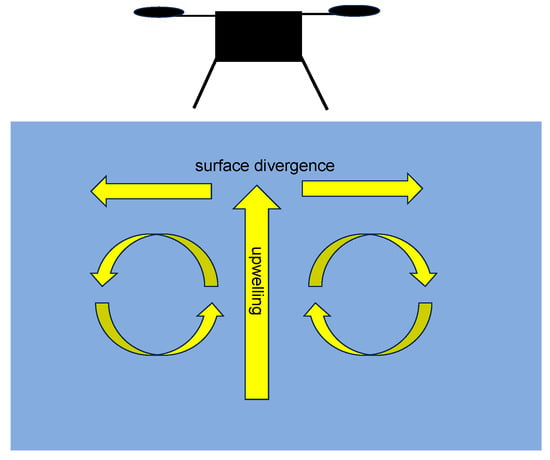

Suspending an in situ water sensor from an sUAS could offer a much simpler and more cost-effective sampling strategy if the influence of the sUAS on the water were better understood. Removal of the pump or stored water samples would typically reduce the sUAS payload because those components are likely to be heavier than basic water property sensors. Furthermore, such sampling could be used to occasionally collect calibration and/or validation data for hyperspectral/imaging methods to increase their accuracy, making accurate, large-scale (broad coverage) measurements more feasible. When an sUAS or helicopter hovers over a water surface, waves and presumably surface waters are transported outward, usually leaving a “still spot” of water beneath the center of the sUAS, as shown in Figure 1. In this location, it is entirely feasible that water is rising toward the surface, and if so, it would provide a sampling location in situ that is relatively free of contaminated water (e.g., contaminated by enhanced oxygenation of the water from sUAS-induced surface mixing) and thus, be similar to the water sample that is pumped from depth for on-board processing in many current approaches. To explore this hypothesis, laboratory experiments were conducted in a water flume to measure the circulation underneath an sUAS while it hovers above the surface. These measurements provide important insights regarding sampling approaches for water quality monitoring using sUASs by examining where water samples can be collected with minimal interference from the presence of the sUAS.

Figure 1.

“Still spot” that occurs directly under a hovering sUAS (drone).

2. Water Circulation Experiments

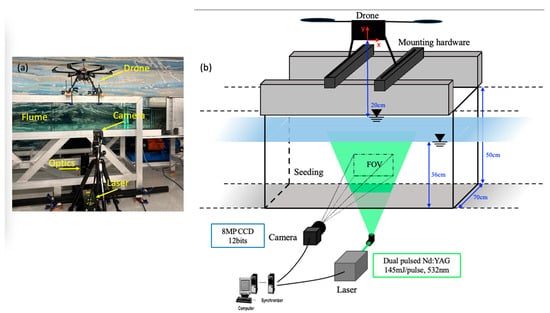

Experiments were conducted in a water flume with a cross section of 0.7 m (wide) × 0.5 m (deep) and a length of 16 m that was filled with fresh water to a depth of 36 cm. The water in the flume was stagnant at the start of each experiment. A customized Aurelia X6 hexacopter sUAS developed at the University of South Carolina [4] was utilized in the experiments. It consisted of six rotors (or “blades”) spanning approximately 147 cm, with each rotor having a length of 46.5 cm. The sUAS was secured across the top of the flume at 20 cm above the water line, shown in Figure 2, and its rotors turned on at various speeds. The air flow speed underneath the sUAS was estimated at the start of each experiment with a digital air flow meter by measuring the maximum air flow speed over an approximately 30 s period at the elevation of the sUAS’s feet. The sUAS was operated for 1–2 min before flow measurements were initiated. Measurements were performed using the particle image velocimetry (PIV) technique along the center of the water channel, imaging 2D flow velocities (u, v) in the along-channel (x) and vertical directions (y) (see Figure 2). The PIV setup, data acquisition, and processing are described in the subsequent subsections.

Figure 2.

(a) Image and (b) schematic representation of the experimental setup.

In the flume, water flow generated by the downdraft from the rotor blades is constrained laterally in the cross-channel direction. This constraint impacts results in two ways. First, divergence of flow at the surface due to the downdraft from the sUAS may be minimized by flow reflected back towards the sUAS center from the channel side walls. Thus, any observed effects from flow divergence at the surface from the sUAS, such as upwelling, could be less than what would be expected in nature, where flow is typically unconstrained in all directions. Secondly, strong cross-channel reflections make accurate PIV measurements more challenging due to more out-of-plane motion in the PIV images. For this reason, experiments were conducted at two magnifications using a 50 mm and 105 mm lens (see Section 2.1). At larger magnification, larger pixel displacements are possible before errors due to out-of-plane motion become too large, increasing the accuracy of velocity measurements (due to less reliance on sub-pixel interpolation); however, at high magnification, the entire water column is not visible in the PIV field-of-view (FOV), making interpretation of larger-scale flow patterns difficult. Here, we choose to only show results from the smaller magnification experiments because the entire water column was measured, but the mean velocities over the same area were similar from both magnification experiments, indicating that the results from the larger FOV with smaller pixel displacements are accurate. See [12] for more details about PIV measurements and discussion of the above trade-offs between magnification, time between images, and velocity errors.

2.1. PIV Configuration

PIV flow measurements were performed along the center of the channel. Measurement sets, each consisting of 400 PIV image pairs, were acquired at two locations along the channel—under the center of the sUAS (Figure 2) and under the center of a rotor/blade. A Quantel ND:YAG 145 mJ/pulse dual-head laser, along with a 45-degree mirror, cylindrical lens, and a spherical lens, was used to form a light sheet of approximately 1 mm thickness along the channel center. An 8 megapixel 12-bit CCD cross-correlation (i.e., double exposure) camera with a 50 mm Nikon lens was positioned perpendicular to the light sheet and acquired images at ~8 Hz (PIV image pairs at ~4 Hz). A synchronizer was used to coordinate the camera image acquisition with the laser pulses. Before each experiment (as needed), the flume was locally seeded with tracer particles (Potters glass microspheres of diameter ~10 microns) below the sUAS before it was turned on. The propellers ran for 1–2 min to circulate the water before PIV experiments were initiated, allowing the tracer particles to disperse. At each location, experiments were conducted for maximum target air flow speeds of approximately 5 m s−1, 7.5 m s−1, and 10 m s−1.

Calibration of the PIV measurements was performed using a calibration plate, where the conversion factor was 0.013 cm pixel−1 for all experiments, and the time between PIV images in a pair was 29 ms. These parameters are used to convert pixel displacements into flow velocities. The PIV FOV covered the air–sea interface to the channel bottom and was approximately 42 cm long in the along-channel direction, approximately centered on either the sUAS center or blade/rotor center. Target (maximum) air flow speeds could not be obtained exactly due to a lack of precise repeatability in the sUAS operation and its associated air flow; Table 1 shows the measured maximum air flow speeds for each PIV experiment.

Table 1.

Target maximum air flow speeds and the measured maximum air flow speeds (over ~30 s period) for PIV measurements taken under the body and under the blade.

2.2. Post-Processing of PIV Measurements

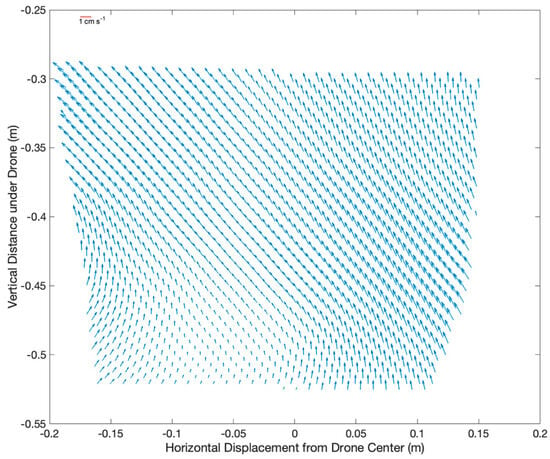

The images within a PIV image pair were cross-correlated using a recursive Nyquist grid in the PIV software, Insight 4G™. The grid started with interrogation windows of 64 pixels × 64 pixels and ended with windows of 32 pixels × 32 pixels with 50% overlap. Prior to correlation, the water surface and flume bottom were masked out of the PIV images (including slightly below the surface, if surface deflections or waves were present on the surface). Subsequent to the correlation, results were globally filtered for outliers greater than three standard deviations from the map mean vector, and locally filtered at 3 × 3 interrogation windows for outliers greater than two pixels from this neighborhood median. Outliers were replaced by the local neighborhood (3 × 3 interrogation windows) median. Finally, PIV vector maps were smoothed with a 5 × 5 interrogation window lowpass filter run over each map. After converting pixel displacements to velocities (see Section 2.1 for conversion factors), data were ensemble-averaged over the 400 PIV velocity maps to explore the mean circulation induced by the sUAS. An example ensemble-mean PIV velocity map for the 7.5 m s−1 target air flow speed under the sUAS body (Vair = 7.8 m s−1; Table 1) is shown in Figure 3, where the coordinate system is referenced to the sUAS center with negative vertical coordinates indicating distance below the sUAS (Figure 2). Velocity measurements have a spacing of 2.1 mm.

Figure 3.

Ensemble-mean PIV velocity map for the 7.5 m s−1 target air flow speed under the sUAS center. Every 5th vector is displayed for clarity. See red scale vector.

3. sUAS-Induced Water Circulation

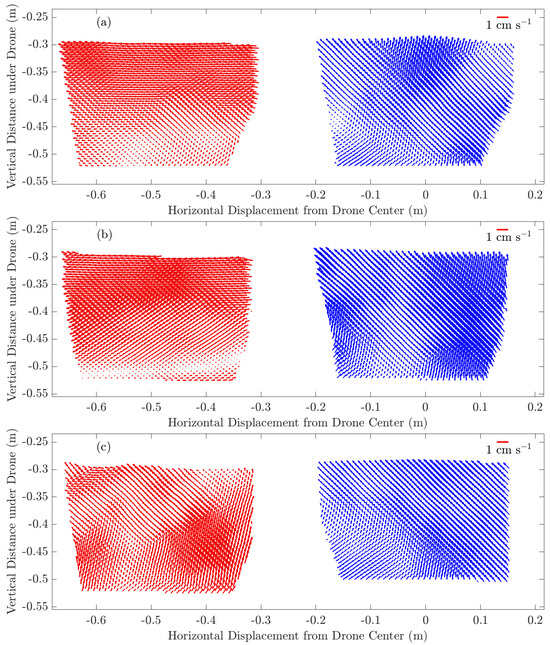

The ensemble-averaged water velocities for both under the body and rotor/blade [13] are shown in Figure 4. These velocity maps show a clear circulation pattern with flow under the body of the sUAS moving upward, or upward and outward, while the flow under the blade clearly shows outward movingoutward-moving surface flow (i.e., away from the sUAS center). This pattern establishes support for a circulation cell under the sUAS, where, if present, one should observe directly under the sUAS upward flow, and as one moves toward the blade from the sUAS center, vertical velocities should become smaller, until they change direction and are downward (indicating the far/opposite side of the circulation cell). For velocities in the horizontal direction, near the circulation cell’s center, where there would be small vertical velocities, one would expect outward horizontal surface currents to dominate. The flow fields shown in Figure 4 are consistent with this pattern. As such, it is noteworthy that for the lower air flow speeds, there are regions of downward flow or small positive vertical velocities under the blade, evidencing the opposite/far side of the circulation cell. In contrast, at the 10 m s−1 target air flow speed, the velocities under the blade continue to show upward velocities, which indicates that the circulation cell might become larger as the air flow speed increases. In general, the induced-flow velocities are on the order of millimeters per second for air flow speeds on the order of meters per second, consistent with the order of magnitude of the density difference between air and water, providing evidence of the momentum transfer from the wind to the water.

Figure 4.

Ensemble-averaged flow velocities for the target air flow speeds of (a) 5 m s−1, (b) 7.5 m s−1, and (c) 10 m s−1. Flow under the rotor/blade is in red and flow under the body is in blue, and also, see the scale vector in the upper right corner of each subfigure. Every 5th vector is shown for clarity.

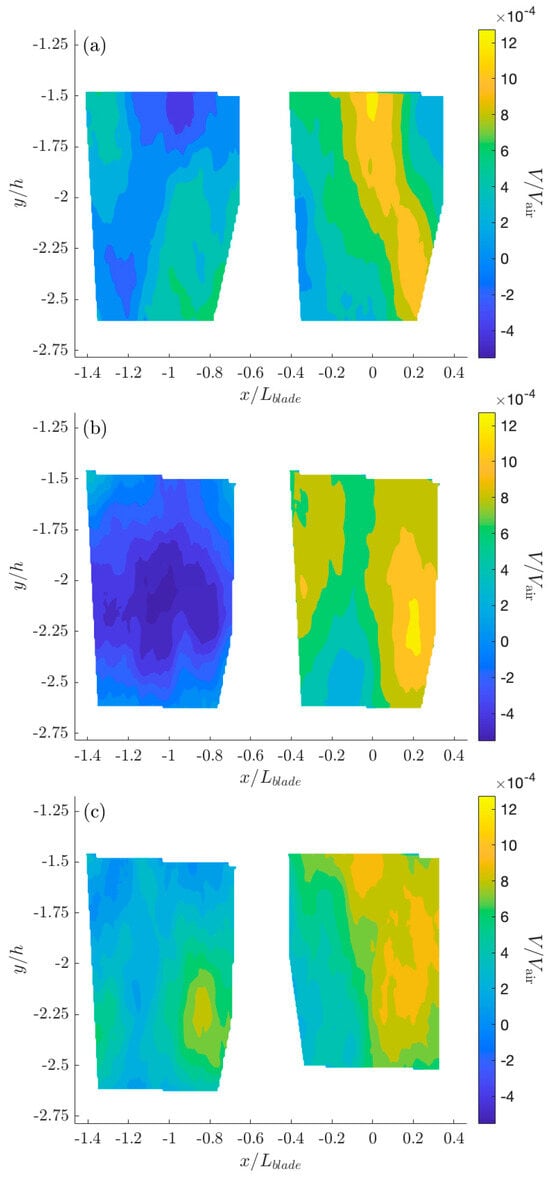

To better evaluate the presence of upwelling due to surface divergence of the flow, we show contour plots of the vertical velocities under the sUAS body and blade in Figure 5 that are normalized by the measured air flow speed (Vair), the hover height of the sUAS above the water (h = 20 cm), and the length of the blade (Lblade = 46.5 cm). In Figure 5, the region of upwelling below the sUAS is very apparent and widens as the air flow speed increases. For the 5 m s−1 and 7.5 m s−1 target air flow cases, under the blade, very small upward or downward velocities are observed; recall that the differences between the actual air flow speeds and the target speeds under the blade for the 5 m s−1 and 7.5 m s−1 target speeds were more similar to each other, relative to the differences for the measurements performed under the sUAS body at these target speeds (Table 1). This similarity in air flow speed may lead to more similar circulation under the blade relative to the 10 m s−1 target air flow speed case. Furthermore, it is important to recall that the under-body and under-blade measurements were not performed at the same time; thus, perfect continuity across the two FOVs is not expected.

Figure 5.

Normalized ensemble-averaged vertical velocities for target air flow speeds of (a) 5 m s−1, (b) 7.5 m s−1, and (c) 10 m s−1.

Collectively, the results suggest the presence of a pair of counter-rotating vortices under the sUAS body, similar to that shown schematically in Figure 6. Qualitatively, the size of these vortices is related to the air flow speed; however, to quantify that relationship more precisely, a larger range of air flow speeds is needed, as well as more trials at the same air flow speed to evaluate this relationship with statistical significance.

Figure 6.

Conceptual model of water circulation under a hovering sUAS.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Laboratory flow measurements, using the PIV technique, were performed in a water flume to examine the water circulation pattern underneath an sUAS while it hovered above the water. Three target air flow speeds were examined, and the flow field under the body of the sUAS, as well as under a blade, was measured for each target flow speed (six PIV datasets). Inconsistencies and unpredictability in the sUAS’s air flow speeds made precisely achieving the target air flow speeds impractical, so there were some inconsistencies in the measured air flow speeds under the body relative to under the blade, and target speeds were only nominally achieved (Table 1). Nonetheless, a clear circulation pattern was observed. Letting the flow develop over a longer period of time (here, only a couple minutes) may result in development of stronger circulation because air has a relatively low viscosity that could take the full circulation a longer period to establish; however, the results presented herein show that the circulation does at least begin to develop within minutes of the hovering being initiated at a given location.

The downdraft from the rotor blades impinges on the water surface and then drives flow outward from the sUAS center. This surface divergence was evident at all three target air flow speeds. As a result of the surface divergence, upwelling under the sUAS body is observed that extends outward all the way to the region under the blade at the highest target air flow speed, demonstrating that the upwelling region/area may be related to the air flow speed. Because the volume over which the upwelling occurs changes with the air flow speed, a clear pattern of increased upwelling intensity with increased air flow speed was not evident. Future research should consider how to quantitatively determine a relationship between sUAS air flow speed and the magnitude of the upwelling.

These results demonstrate that a sensor suspended directly beneath an sUAS while it hovers would be primarily measuring true water properties of the lower waters in the water column (i.e., below surface-waters) due to upwelling and would likely not be contaminated by the presence of the sUAS if taken directly under the body of the sUAS (in this “still-water patch”). This result is significant, as it suggests that it is possible to take water quality measurements from an sUAS in this manner, which greatly reduces the cost of continuous water quality monitoring as long as a measurement anywhere within the water column would be sufficient. Such a method is also not as susceptible to mechanical failures of the water-sampling payload [3]. Removal of the pump and water sample collections via sUAS-based sampling greatly simplifies the drone mission, making sUAS-based sampling more simplified and, therefore, more accessible to a wider range of water quality monitoring initiatives (e.g., able to be utilized by both scientists and non-scientists). The measurements reported in this manuscript cannot determine from what depth the upwelled water would originate, but future work should help to quantify this relationship. Nonetheless, these results pave the way for advances in water quality monitoring using sUASs. Use of sUASs would be particularly beneficial for assessing changes to water quality before and after storms, as they can be mobilized quickly with minimal labor.

While inland water bodies can be quite calm and thus similar to conditions tested here (e.g., storm water retention ponds or small tidal creeks), it is important to note that in other natural settings, these sUAS-induced water velocities could be competing with other natural phenomena such as currents and surface waves generated by winds or tides, and such interactions may impact the results reported herein. For example, when currents and wave-induced flow are much larger than the sUAS-induced circulation, the depth of the sampled water (origin of upwelled water) might be shallower, or the surface divergence under the sUAS diminished, leading to weak-to-no upwelling; however, in such cases, one might expect the disappearance of this “still spot”. Furthermore, wind-related surface currents may horizontally displace the “still spot” under a hovering sUAS, in which case the upwelling is likely to occur in that location rather than directly under the sUAS, as found here. Adjustment of sensor placement within the upwelling region, wherever it may be, will help avoid sampling waters that have been at the surface for some time and would likely be impacted (e.g., oxygenated) by the sUAS’s downwash. These sorts of interactions should be further studied in the field with co-occurring water quality and flow measurements in addition to nearby traditional measures of water quality. Such field studies would need to be performed over a range of environmental conditions (e.g., seasons, wind conditions, tidal phases, etc.) in order to quantitatively assess how such natural phenomena would interact with sUAS-induced air and water flows.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E.H., N.V. and M.L.M.; methodology, E.E.H.; formal analysis, B.F. and J.C.C.; investigation, E.E.H.; resources, E.E.H., N.V. and M.L.M.; data curation, E.E.H., D.D.-E., N.V., W.E.S., P.K.W. and M.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.E.H.; writing—review and editing, E.E.H., B.F., J.C.C., D.D.-E., N.V. and M.L.M.; visualization, B.F.; supervision, E.E.H. and M.L.M.; project administration, E.E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All ensemble-averaged water velocity fields for each air flow speed and field-of-view location are available at the Mendeley Data Repository (doi:10.17632/ttmghxd4j3.1). Associated metadata are included.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hadar Ben-Gida for providing a graphic of a PIV setup, which was modified for the schematic shown in Figure 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCD | Charge-coupled device |

| CDOM | Colored dissolved organic matter |

| FOV | Field of view |

| ND:YAG | Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet |

| PIV | Particle image velocimetry |

| sUAS | Small uncrewed aircraft system |

References

- Behmel, S.; Damour, M.; Ludwig, R.; Rodriguez, M.J. Water quality monitoring strategies—A review and future perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 1312–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastore, D.M.; Peterson, R.N.; Fribance, D.B.; Viso, R.; Hackett, E.E. Hydrodynamic drivers of dissolved oxygen variability within a tidal creek in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Water 2019, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koparan, C.; Koc, A.B.; Privette, C.V.; Sawyer, C.B. In Situ Water Quality Measurements Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) System. Water 2018, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanim, K.R.I.; Kalaitzakis, M.; Kosaraju, B.; Kitzhaber, Z.B.M.; English, C.M.; Vitzilaios, N.; Myrick, M.L.; Hodgson, M.E.; Richardson, T.L. Development of an Aerial SUAS System for Water Analysis and Sampling. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 June 2022; pp. 1061–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Sanim, K.R.I.; English, C.M.; Kitzhaber, Z.B.; Kalaitzakis, M.; Vitzilaios, N.; Myrick, M.L.; Hodgson, M.E.; Richardson, T.L. Autonomous UAS-based Water Fluorescence Mapping and Targeted Sampling. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2023, 108, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, S.J.; Bangira, T.; Sibanda, M.; Gurmessa, S.K.; Clulow, A.; Mabhaudhi, T. Assessing sUAS-based remote sensing for monitoring water temperature, suspended solids, and CDOM in inland waters: A global systematic review of challenges and opportunities. Drones 2024, 8, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, B.J.; Stocker, M.D.; Valdes-Abellan, J.; Kim, M.S.; Pachepsky, Y. SUAS-based imaging to assess the microbial water quality in an irrigation pond: A pilot study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 135757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridolfi, E.; Manciola, P. Water level measurements from sUASs: A pilot case study at a dam site. Water 2018, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelare, S.D.; Aglawe, K.R.; Waghmare, S.N.; Belkhode, P.N. Advances in water sample collections with a sUAS—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 4490–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, C.M.; Kitzhaber, Z.B.; Sanim, K.R.I.; Kalaitzakis, M.; Kosaraju, B.; Pinckney, J.L.; Hodgson, M.E.; Vitzilaios, N.; Richardson, T.L.; Myrick, M.L. Chlorophyll Fluorometer for Intelligent Water Sampling by a Small Uncrewed Aircraft System (sUAS). Appl. Spectrosc. 2022, 77, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, M.E.; Vitzilaios, N.; Myrick, M.L.; Richardson, T.L.; Duggan, M.; Sanim, K.R.I.; Kalaitzakis, M.; Kosaraju, B.; English, C.M.; Kitzhaber, Z.B. Mission Planning for Low Altitude Aerial sUASs during Water Sampling. Drones 2022, 6, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, M.; Willert, C.; Kompenhans, J. Particle Image Velocimetry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, E.E.; Fleenor, B.; Coggin, J.C.; Dickerson-Evans, D.; Vitzilaios, N.; Schuler, W.E.; Williams, P.K.; Myrick, M.L. Water Circulation Measurements Under a Hovering Drone; Mendeley Data; 2025; V1. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ttmghxd4j3/1 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).