1.1. Mechanisms and Limitations of Chlorination and UV Disinfection

Conventional chlorination and ultraviolet (UV) irradiation technologies remain widely used for water disinfection; however, their efficiency is constrained by fundamental physicochemical mechanisms. During chlorination, natural organic matter (NOM) reacts with chlorine molecules, forming carcinogenic disinfection by-products (DBPs) such as trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetonitriles (HANs):

In some cases, the concentration of these by-products in treated water can reach ≈ 0.1 mg/L [

5,

6,

7,

8]. This formation pathway is further influenced by chlorine hydrolysis–dissociation equilibria:

At elevated pH values, hypochlorous acid (HOCl) partially transforms into hypochlorite ions, altering its reactivity and increasing DBP production potential, despite retaining biocidal activity.

UV disinfection performance is governed by the Beer–Lambert law, which determines the light penetration in water:

where

and

are the incident and transmitted UV intensities, α is the absorption coefficient, and L is the optical path length. In waters with high turbidity or complex organic composition, α increases, thereby reducing photon penetration depth and lowering UV efficiency by 20–40% [

9,

10]. Microbial inactivation during UV irradiation can also be described by first-order decay kinetics:

where

and

are the initial and remaining microorganism concentrations,

k is the inactivation rate constant, and

t is the exposure time. As turbidity increases, the value of

k decreases, requiring higher UV doses (mJ/cm

2) to achieve equivalent disinfection performance.

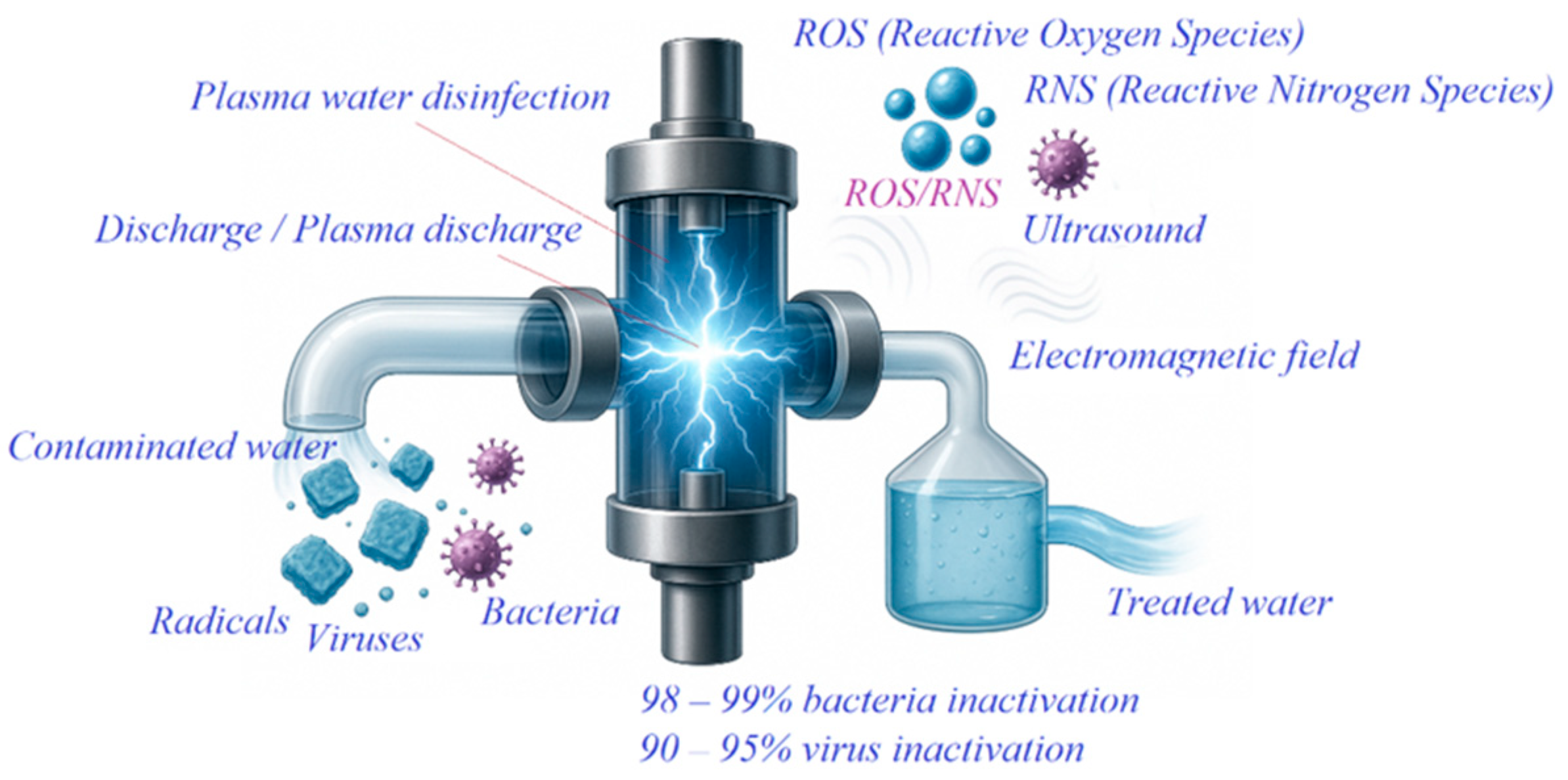

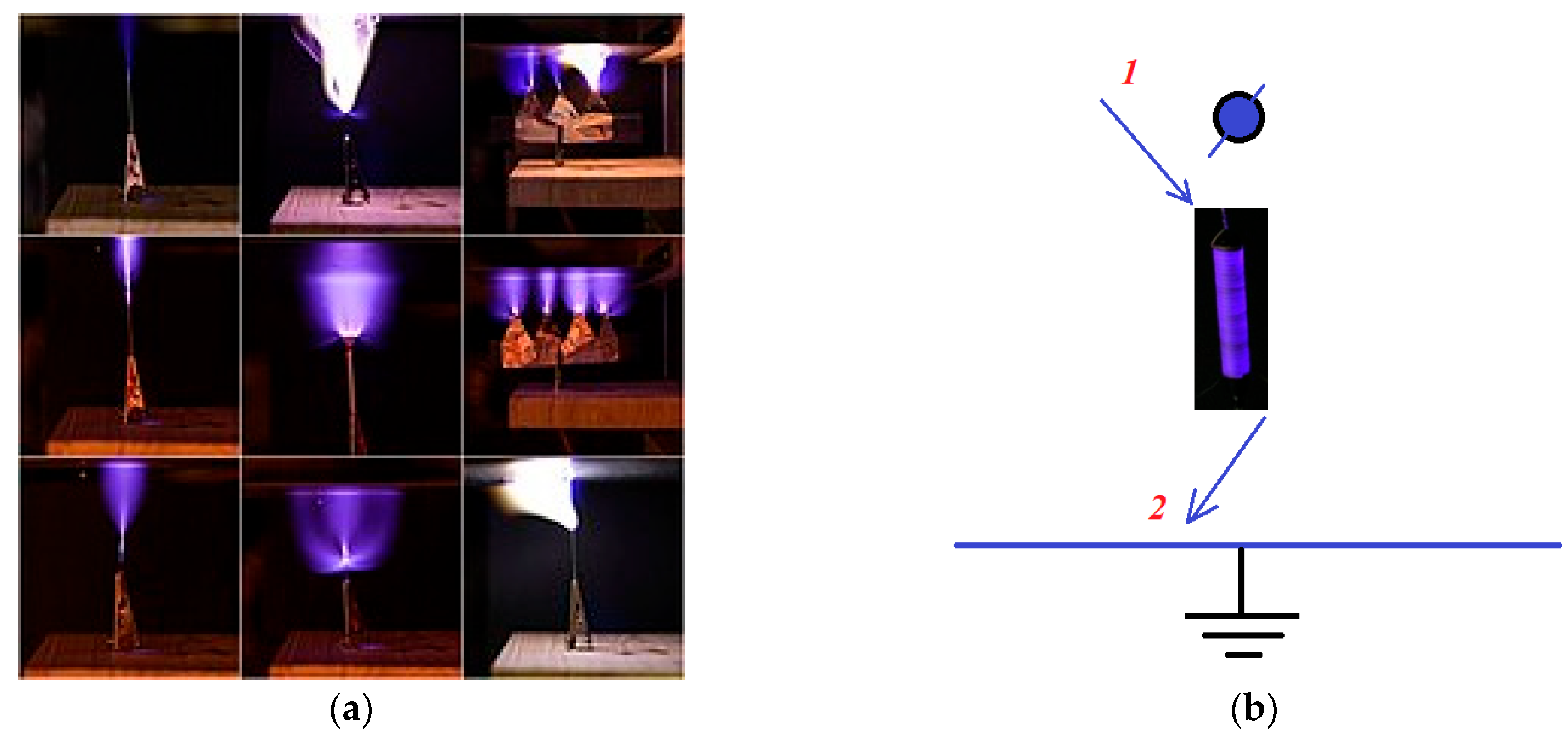

1.5. Plasma-Based Water Disinfection

The first comprehensive analysis of plasma technologies applied to water purification was presented in the work of Zeghioud H. et al. [

14]. The authors theoretically described the microbiological effects of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) generated by high-voltage electrical discharges, as well as their interactions with organic pollutants in water. During plasma discharge, collisions between high-energy electrons and water molecules lead to molecular excitation and subsequent dissociation according to the reaction:

The hydroxyl () and hydrogen () radicals formed in this process are highly reactive oxidants capable of damaging microbial cell membranes and DNA structures, resulting in effective microbial inactivation.

In addition, the interaction of nitrogen and oxygen molecules within the plasma phase produces secondary reactive species:

These reactions generate nitrogen oxides (NO and NO2), which dissolve in water to form nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−) ions. Simultaneously, long-lived oxidizing agents such as ozone (O3) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are produced, enhancing the overall disinfection efficiency of the plasma-treated water.

Furthermore, the reactive species generated by plasma interact with dissolved organic contaminants, initiating oxidative degradation reactions:

This chain of reactions leads to the progressive oxidation of organic compounds, eventually converting them into harmless end products such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). Consequently, plasma discharges can simultaneously remove both biological and chemical pollutants from water.

Overall, the theoretical models described by Zeghioud H. and colleagues established the scientific foundation of plasma-chemical disinfection methods. The combined action of short- and long-lived reactive species (•OH, O3, NO2−, H2O2) generated in plasma promotes efficient microbial inactivation and complete mineralization of organic compounds. Therefore, high-voltage plasma discharge technology is considered an environmentally safe, reagent-free, and effective approach for advanced water disinfection and purification.

In the works of Barjasteh et al. (“Recent Progress in Applications of Non-Thermal Plasma for Water Purification, Bio-Sterilization, and Decontamination”, 2021) and Foster et al. (“Perspectives on the Interaction of Plasmas with Liquid Water for Water Purification”, 2012), the multifactorial effects of plasma discharge on the inactivation of bacteria and viruses in water are comprehensively discussed [

15,

16]. The studies demonstrated that plasma discharge acts not only through the generation of chemically active species (•OH, O

3, H

2O

2) but also via the combined influence of acoustic shocks and electromagnetic fields that disrupt the structural integrity of microorganisms. Overall,

Table 2 presents the dependence of microbial inactivation on plasma power and exposure time in an aqueous medium.

The table shows that as plasma discharge power and exposure time increase, the inactivation level of microorganisms also rises significantly. The highest efficiency was observed for E. coli at 140 W and 60 s exposure, achieving 99.999% inactivation, which demonstrates the strong microbiological effectiveness of plasma-based disinfection.

In 2021, Rathore et al. in their work “Investigation of Physicochemical Properties of Plasma Activated Water and Its Bactericidal Efficacy” comprehensively examined the physicochemical characteristics and bactericidal performance of plasma-activated water (PAW) [

17]. Meanwhile, Zhang et al. (2024) demonstrated the strong antibacterial effect of PAW against Vibrio parahaemolyticus and elucidated its oxidative damage mechanism on bacterial cell membranes [

18]. These findings indicate that plasma-activated water can serve as an eco-friendly and highly effective alternative to conventional reagent-based disinfection methods. Overall,

Table 3 presents the characteristic parameters of reactive species in plasma-activated water (PAW).

The table shows that the reactive species generated in plasma-activated water (PAW) differ significantly in their lifetimes and oxidation potentials. Short-lived radicals such as •OH and O3 exhibit high oxidative potentials (2.07–2.80 V) and can damage bacterial cell membranes with an efficiency of up to 95–99%.

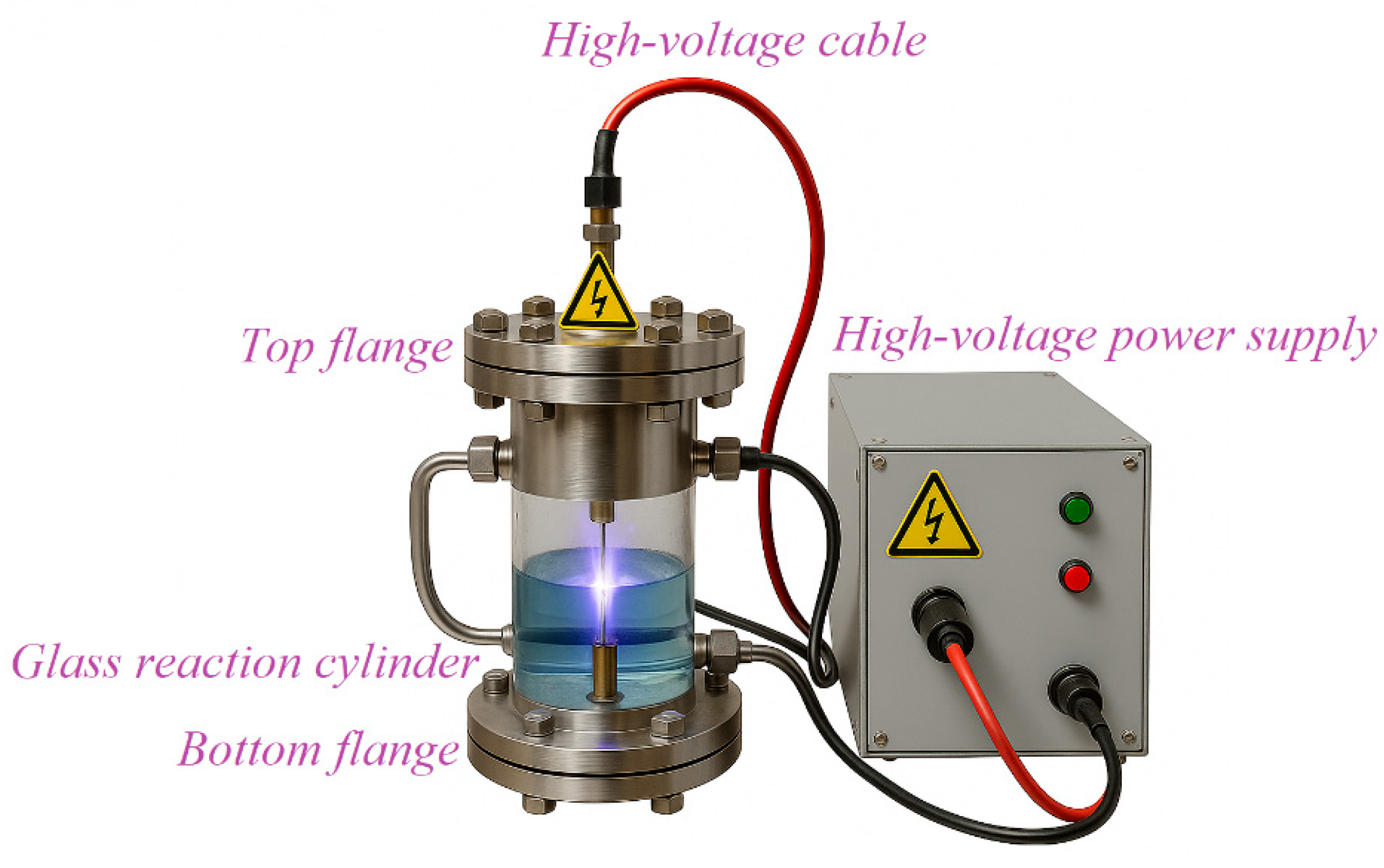

Malyushevskaya et al. (2024), in their study “Hybrid Water Disinfection Process Using Electrical Discharges”, investigated a hybrid water disinfection method based on high-voltage underwater electrical discharge and identified the key physicochemical factors responsible for microbial inactivation [

19]. The research highlighted the critical role of cavitation, shock waves, and ultrasonic effects in enhancing disinfection efficiency. However, the authors did not provide a detailed analysis of the influence of energy consumption and reactor operating parameters (such as frequency and voltage). Overall,

Figure 1 illustrates the relative contribution of physicochemical factors to microbial inactivation under high-voltage underwater electrical discharge. The relative contribution of cavitation, shock waves, ultrasound, and reactive species shown in

Figure 1 is adapted from Malyushevskaya et al. (2024) [

19].

The figure shows that during high-voltage underwater discharge, cavitation and shock waves have the highest contribution to microbial inactivation, accounting for 35% and 25%, respectively. Ultrasound and reactive species contribute between 15–20%, indicating their secondary yet significant role in the overall disinfection process.

Mai-Prochnow et al. (2021), in their study “Interactions of Plasma-Activated Water with Biofilms: Inactivation, Dispersal Effects and Mechanisms of Action”, investigated in detail the effects of plasma-activated water (PAW) on biofilms and microorganisms [

20]. The authors identified the mechanisms by which PAW disrupts biofilm structures, inactivates microbial cells, and inhibits their regrowth—including oxidative stress, disruption of intercellular communication, and degradation of the biopolymeric matrix. However, the results were mainly limited to laboratory-scale experiments and have not yet been fully adapted for practical engineering applications. Overall,

Table 4 presents the antibiofilm and antimicrobial efficacy of plasma-activated water (PAW) under laboratory conditions.

The table shows that plasma-activated water (PAW) reduces biofilm thickness by 60–80% and decreases microbial cell viability by an average of 4–5 log units. These results demonstrate the high efficacy of PAW against complex microbiological structures and confirm its potential as an alternative to conventional disinfection methods.

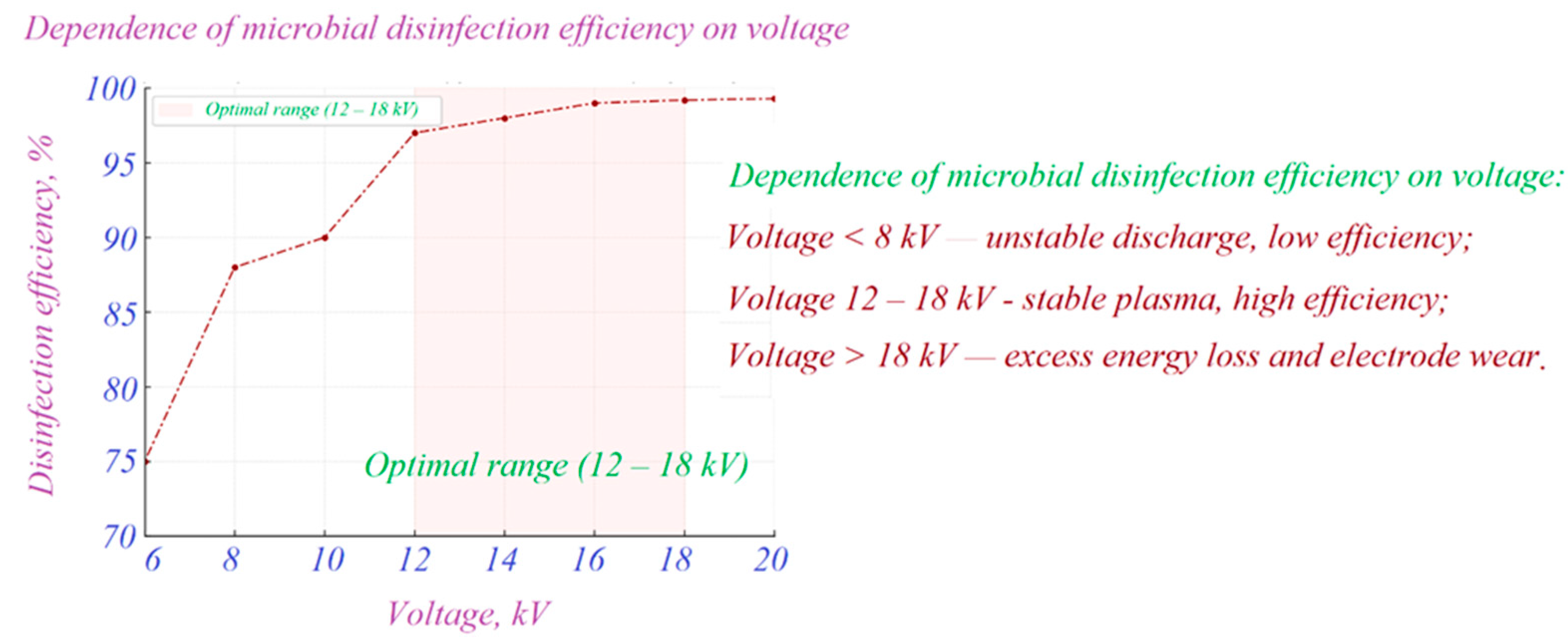

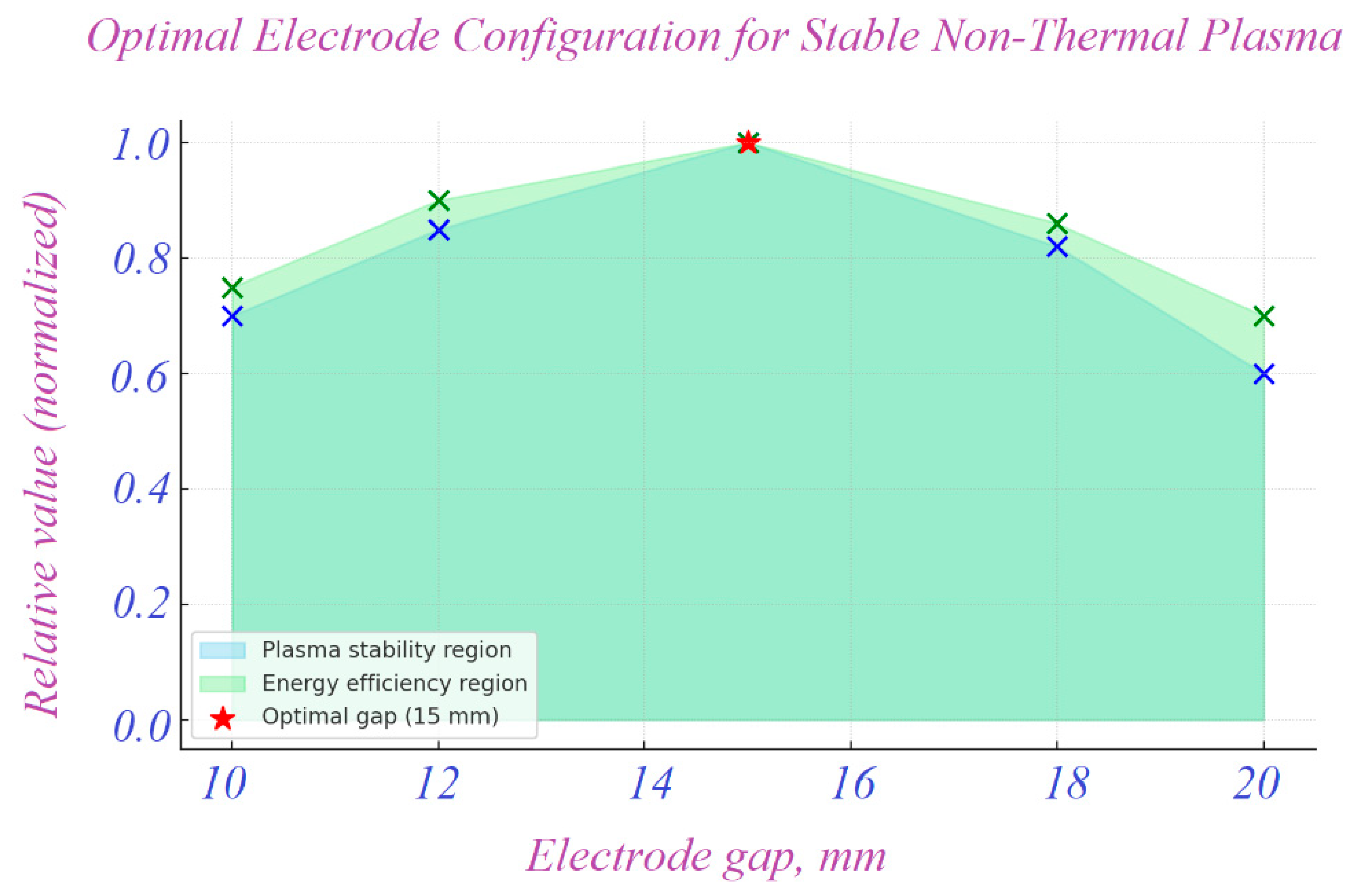

The ecological and sanitary efficiency of plasma was comprehensively studied by Hamza I.A. et al. (2023) [

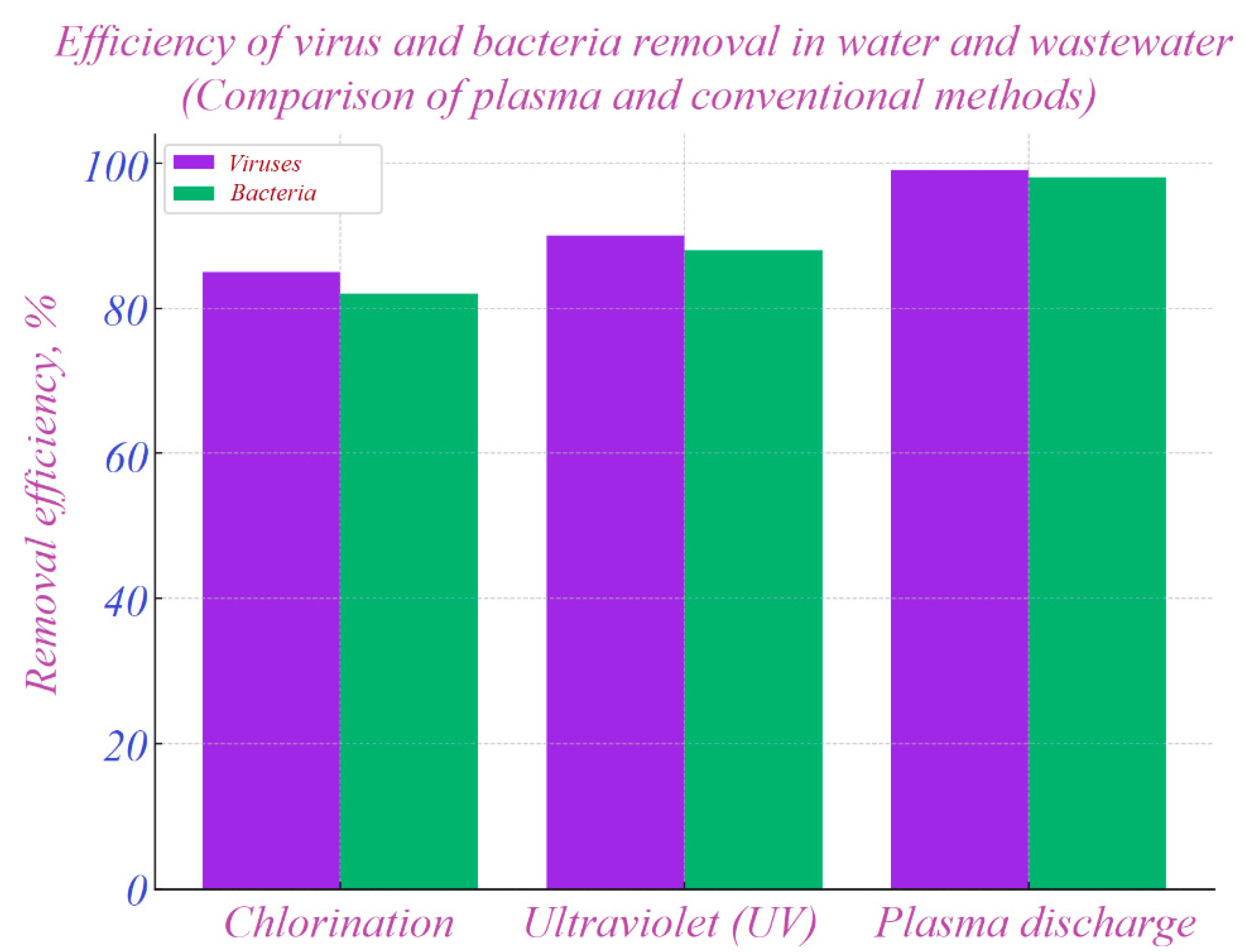

21]. The researchers demonstrated that cold atmospheric plasma exhibits significantly higher effectiveness in the inactivation of viruses, bacteria, and protozoa in water and wastewater compared to conventional chlorination and ultraviolet methods (

Figure 2). Moreover, the plasma technology was found to be capable of degrading organic pollutants; however, high energy consumption and electrode erosion remain technical limitations that need further improvement.

According to

Figure 2, the plasma discharge method demonstrated the highest efficiency: 99% of viruses and 98% of bacteria were eliminated. In comparison, ultraviolet and chlorination methods showed 90–88% and 85–82% efficiency, respectively, clearly highlighting the superiority of plasma technology.

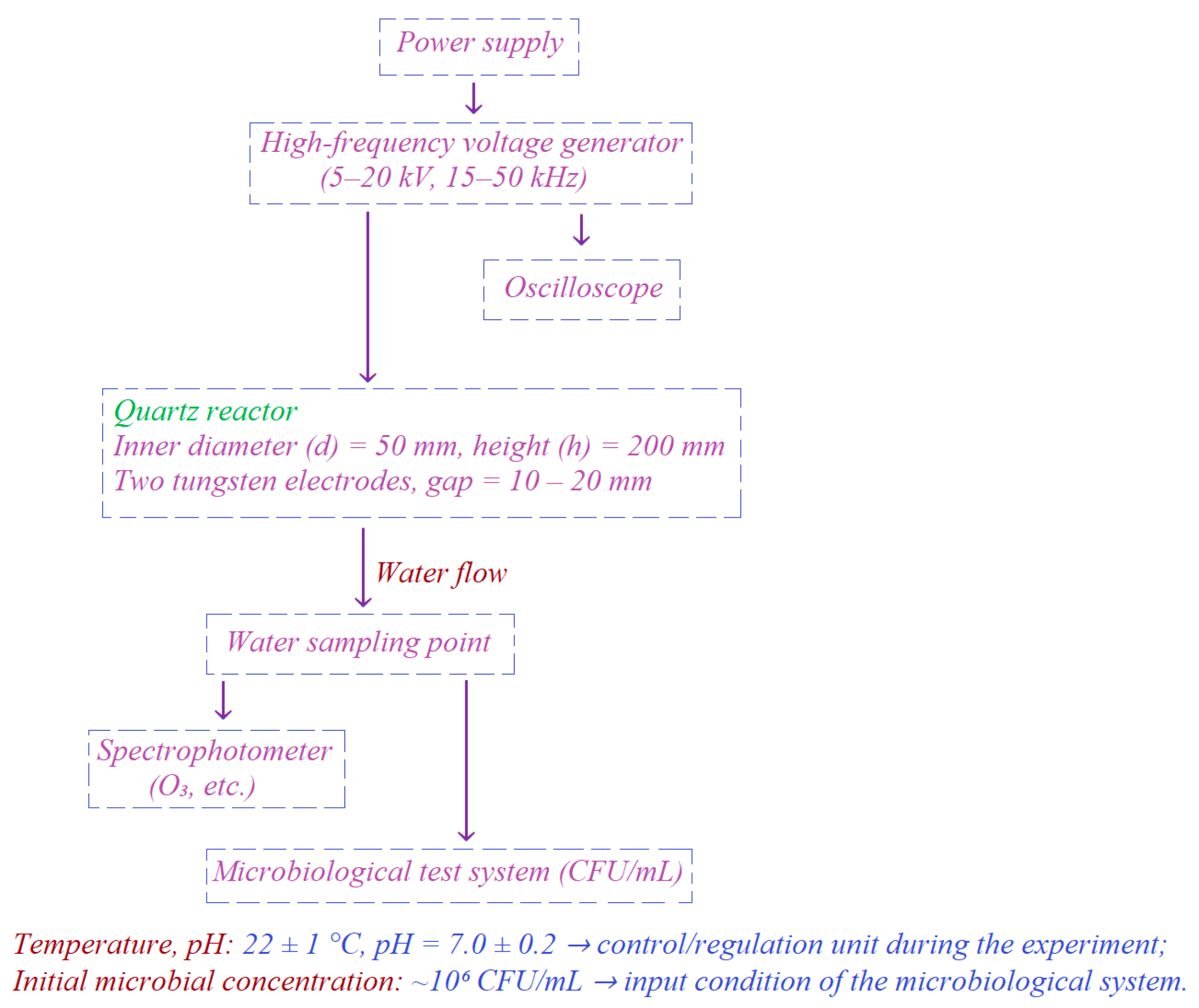

Research on modeling the interaction between plasma and water has been actively developing in recent years. In the study by Nahrani N.M. et al. (2022), the process of discharge formation inside a gas bubble in water was analyzed through numerical modeling [

22]. The authors described the propagation of the electric field, the dynamics of charged particles, and the energy exchange at the bubble boundary, thereby analyzing the complex physico-chemical phenomena occurring at the plasma–water interface. Meanwhile, Lu X. et al. (2022) investigated various discharge modes of plasma bubbles and their interaction mechanisms with liquids using both experimental and theoretical approaches [

23]. Although these studies have laid the scientific foundation for understanding the plasma–water interface, the developed models and obtained results still require further extensive experimental validation. In general,

Figure 3 below presents the time-dependent variation in plasma discharge parameters inside a gas bubble, illustrating the interrelation between the dynamics of the electric field, temperature, and pressure.

Figure 3 shows the time-dependent variation in plasma discharge parameters inside a gas bubble. Over the 0–10 s measurement interval, the electric field gradually decreases from approximately 25 kV/cm to 20 kV/cm. The temperature remains within the range of 10–15 °C, exhibiting sinusoidal oscillations that indicate the rhythmic nature of energy exchange in the plasma process. Meanwhile, the pressure fluctuates slightly within 0.8–1.2 atm, reflecting the relative stability of the system and the dynamic equilibrium at the plasma–water interface.

As seen from the reviewed domestic and international studies, several challenges remain in water disinfection using high-frequency electric discharge. Firstly, the influence of reactor parameters on microbiological efficiency has not been fully determined, while the energy consumption of about 5–20 kWh/m3 limits the large-scale application of this technology. In addition, the resistance of various microorganisms and their ability to recover after plasma exposure are still insufficiently studied. Therefore, comprehensive research aimed at improving energy efficiency and accurately evaluating biological effects is of great scientific and practical relevance today.