Abstract

Oil and grease (O&G) pollution in municipal effluents represents a critical environmental challenge. This study contributes a novel experimental assessment of how pressure and recirculation time influence oxygen transfer, microbubble generation, and pollutant removal in a pilot-scale DAF system, providing new insights into process optimization for municipal wastewater treatment. This study evaluated the efficiency of a DAF system in removing organic pollutants and solids from municipal effluent by varying gauge pressure (1–5 bar) and recirculation time (1–20 min). The initial concentrations present in the effluent were 800 mg/L total solids (TS), 590 mg/L total suspended solids (TSS), 450 mg/L oil and grease (O&G), 360 mg/L biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5), and 710 mg/L chemical oxygen demand (COD). The concentration of dissolved air (interpreted as dissolved oxygen supersaturation) reached 102.3 mg/L and removal efficiencies of 84.4% for O&G, 88.9% for BOD5, 88.7% for COD, and 85% for TSS were achieved, while pH and dissolved solids (DS) remained stable. The saturation factor (f = 0.8) confirmed efficient oxygen-liquid transfer, attributed to the use of Raschig rings in the absorption column. The significance of this work lies in demonstrating that operating conditions directly enhance oxygen dissolution and flotation performance, highlighting an optimization pathway rarely reported for municipal effluents. The results demonstrate that DAF is a robust, stable, and energy-efficient technology capable of effectively removing organic and lipid loads from municipal effluent, providing a sustainable alternative for the pretreatment and reuse of urban wastewater.

1. Introduction

Water is an essential resource for life and human development, but its contamination has intensified due to population growth and anthropogenic activities [1,2]. As demand for fresh water increases, large volumes of wastewater are generated from domestic, industrial and agricultural sectors, threatening the sustainability of this resource and highlighting the urgent need to implement effective solutions [3,4].

Although water covers approximately 70% of the Earth’s surface, only 3% is fresh water available for human consumption, while the remaining 97% is saline [5,6]. This limited availability, coupled with population growth, industrialization and agricultural expansion, has increased the global demand for water, placing unprecedented pressure on this essential resource [3]. As a result, water pollution has become a critical challenge that concerns industrial sectors, governments and society in general [7,8].

Water is essential for life and the balance of ecosystems, but population growth and economic activities have increased the generation of large volumes of domestic, industrial and agricultural wastewater [1,3]. In addition, the growing industrial demand for water has intensified pressure on freshwater availability [9].

Increased water demand and anthropogenic pollution have seriously compromised the availability of fresh water, posing a global threat that requires innovative and sustainable solutions based on scientific evidence [10,11]. Therefore, the increasing discharge of untreated and highly polluted wastewater highlights the urgent need to strengthen water management practices and promote sustainable measures to minimise environmental risks [12].

Water pollution is a complex and multifactorial environmental challenge, caused mainly by the direct discharge of untreated wastewater into water bodies [13]. This problem is exacerbated by interrelated factors such as high energy consumption, the generation of radioactive waste [14], effluents from the textile and laundry industries [15], uncontrolled urban growth [16], inadequate wastewater management [17], as well as industrial waste, mining activities, spills, leaks and excessive use of pesticides and chemical fertilisers [18,19]. As a result, water pollution has become inevitable due to the widespread use of this resource in the industrial, domestic and agricultural sectors [20]. Therefore, the continuous generation of wastewater with high levels of hazardous pollutants urgently requires effective strategies for the protection and sustainable conservation of water resources [21].

In recent years, various technologies for wastewater treatment have been developed and optimised, such as conventional filtration, dissolved air flotation, coagulation-flocculation and biological systems [3,22,23]. These technologies comply with current environmental regulations and stand out for their high efficiency and adaptability to different types of effluents. The selection of the treatment method depends on the characteristics of the wastewater, operating costs, and the level of regulatory compliance required. Among the advanced alternatives, dissolved air flotation (DAF), reverse osmosis (RO), and anaerobic sequential batch reactor (ANSBR) have shown high efficiencies, with DAF standing out with removals of up to 98.6% of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) and 97.9% of chemical oxygen demand (COD), superior to RO (97.9%) and ANSBR (90%). These technologies offer sustainable and effective solutions for water recycling and industrial waste reduction [24,25].

DAF has established itself as a highly efficient technology for removing oils, fats and suspended solids from municipal effluents [26]. Its operating principle is based on the generation of microbubbles that adhere to contaminating particles, reducing their density and facilitating their separation from the liquid without generating additional waste [27,28].

Pérez-Guzmán et al. [29], using a pilot-scale DAF system, reported efficiencies of up to 99.8% in soluble COD removal, 92.3% in turbidity, and 77.2% in colour, confirming the high potential of this technology for advanced wastewater treatment. Over the last two decades, municipal effluent treatment has been extensively investigated with the aim of optimizing pollutant removal efficiency [30].

Gutiérrez et al. [31] evaluated the application of polyaluminium chloride (PAC) in a dissolved air flotation (DAF) system for the treatment of poultry industry effluents. The results showed fat and oil removals between 87% and 97%, while the addition of PAC improved COD and total suspended solids (TSS) removal by up to 90% and 79%, respectively. The tests, conducted under pressures of 30–50 psi and recirculation rates of 20–40%, demonstrated the efficiency and stability of the system in the face of operational variations, consolidating DAF as a viable alternative for advanced industrial effluent treatment.

Currently, dissolved air flotation has positioned itself as a technology superior to membranes for the removal of oils and fats in effluents, achieving efficiencies greater than 90% and significant reductions in COD and TSS [3,32,33]. In addition, recent advances in integrated systems and optimised saturators have increased operational stability, energy efficiency and process selectivity, reinforcing the potential of DAF in advanced wastewater treatment [28,34].

In this context, the present study aims to implement and evaluate a dissolved air flotation (DAF) system for the treatment of municipal wastewater, through the physicochemical characterisation of the effluent, the determination of the saturation factor in the absorption column and the optimisation of the saturated water dosage, in order to maximise the efficiency of the process. Considering that DAF has demonstrated removal efficiencies of over 90% in effluents with high oil, grease, and solids loads [32], this study seeks to generate technical and operational evidence to support its application in municipal wastewater treatment systems.

To strengthen the contextual background of the study, a comparative table summarizing the typical performance, advantages, and limitations of DAF relative to other wastewater treatment technologies was included (Table 1). This comparison supports the selection of DAF for municipal effluents and highlights the technological gap addressed in this research.

Table 1.

Comparison of DAF with conventional and advanced wastewater treatment methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Municipal Wastewater

Municipal wastewater samples were collected from the main collection pipe that groups the discharges of the APV Agua Buena, Patrón San Sebastián and Agua Dulce sectors, in the district of San Sebastián, Cusco (Peru), whose effluent flows into the Huatanay River. Grab samples were manually collected between 08:0 and 11:0 h, using 20 L polyethylene containers previously washed with distilled water and rinsed with the sample. The samples were stored at 4 ± 1 °C and analysed in the laboratory within 24 h of collection. The procedure followed the guidelines of the Protocol for Monitoring the Quality of Surface Water Bodies of the National Water Authority, ensuring representativeness and traceability [35].

2.2. Physicochemical Characterisation of the Effluent

The physicochemical characterization of the municipal effluent was conducted in the accredited laboratory “Química Lab” following the procedures established in the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater [36]. Total solids (TS) were quantified by drying homogenized samples at 103–105 °C to constant weight (Method 2540 B), while total suspended solids (TSS) were determined by filtration through pre-weighed glass fibre filters (Whatman GF/C), followed by drying of the retained material under the same conditions (Method 2540 D). Oil and grease (O&G) concentrations were obtained by liquid–liquid extraction using benzene, evaporation of the solvent, and gravimetric measurement of the residual lipid fraction in accordance with Method 5520 B. Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) was measured by incubating the diluted samples at 20 °C for five days under dark conditions and determining dissolved oxygen by the Winkler iodometric method (Method 5210 B), whereas chemical oxygen demand (COD) was assessed via dichromate digestion under closed reflux and spectrophotometric reading at 600 nm (Method 5220 D). Additionally, pH was determined with a previously calibrated potentiometer following Method 4500-H+ B. All analyses were performed in triplicate, and results are reported as mean values to ensure analytical reliability.

2.3. System Configuration and Operation

The DAF pilot system was installed in the Pilot Plant of the Professional School of Chemical Engineering and consisted of an absorption column packed with Raschig rings (Ø 6–12 mm), coupled to a recirculation pump and a compressor of up to 6 bar for air dissolution and microbubble generation. The effluent was treated in a 20 L conical tank, with injection of 10–20% of previously saturated water. The tests were carried out under controlled conditions of saturation pressure of 1–5 bar and recirculation times of 1–20 min. Oxygen transfer efficiency was determined using the saturation factor (f):

where is the concentration of dissolved oxygen, S is the solubility of oxygen at the operating temperature, and P is the absolute pressure applied.

2.4. System Start-Up Period

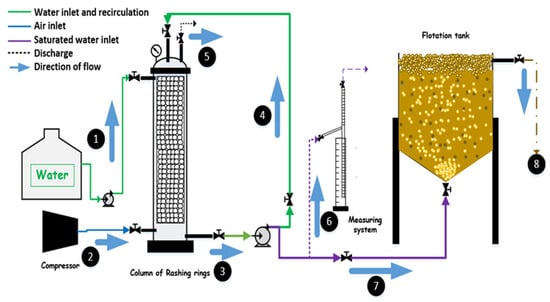

The operation of the DAF system begins with the entry of water from the feed and recirculation line (1), which is pumped into the absorption column to establish the working flow rate. In parallel, the compressor injects pressurized air through the supply line (2), allowing the air to enter the column packed with Raschig rings, where the oxygen dissolution process takes place. Inside this column, it is verified that the upward flow is uniform and free of leaks, while excess undissolved air is released through the vent valve (5). The saturated water produced in the column is directed (3) to the measurement system (6), where the saturation factor is determined before re-entering the circuit. Part of this stream returns to the column through the recirculation line (4), enhancing oxygen–water transfer efficiency, while the remaining portion is conveyed to the flotation tank through the saturated-water inlet (7). Once inside the flotation tank, the saturated stream releases fine microbubbles that rise and attach to suspended solids, oils, and greases in the wastewater. This promotes the formation of a surface layer of floated material, which is removed through the discharge outlet for solids, oils, and greases (8).

Before starting the experimental tests, the entire system underwent a 30 min start-up period using potable water to verify the tightness of the absorption column, the proper operation of the recirculation pump and compressor, and the homogeneous generation of microbubbles in the flotation tank. Subsequently, preliminary cycles were carried out with municipal wastewater until the operating pressure and dissolved oxygen concentrations stabilized, ensuring stable and reproducible hydrodynamic conditions for the experimental runs. The schematic representation of the DAF system is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the pilot DAF system and its operational components.

2.5. Removal Efficiency Assessment

Flotation tests were performed by varying saturated water injection times (1, 3, 5, and 7 min) and treatment volumes (3, 5, 7, and 10 L). The physicochemical parameters of the effluent were determined: total solids (TS), total suspended solids (TSS), oils and fats (OF), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5), and chemical oxygen demand (COD), before and after treatment, and the removal efficiency was calculated using:

where and represent the initial and final concentrations of each parameter, respectively. This approach allowed quantifying the effectiveness of the DAF process under different operating conditions, providing a comprehensive indicator of the reduction in the pollutant load in the municipal effluent.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and significant differences among treatments were identified using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test at a confidence level of α = 0.05. Statistical processing was performed using R (Version 4.3.2).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Municipal Effluent

The initial characterization of the municipal effluent revealed high concentrations of contaminants, with values of total solids (TS: 800 mg/L), total suspended solids (TSS: 590 mg/L), oil and grease (O&G) 450 mg/L, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) 360 mg/L and chemical oxygen demand (COD) 710 mg/L, which exceed the maximum admissible values (MAV) for discharge to the sewer established by the National Water Authority [34]. Table 2. These results are consistent with those reported in other regions of Latin America, where municipal effluents present high loads of solids and organic matter that reduce the efficiency of conventional treatment systems [3,6]. Although the pH (7.6) remained within the normative range (6.5–8.5), the high concentration of oils and fats constitutes a critical factor, since it interferes with oxygen transfer and limits biodegradation, which highlights the need to apply advanced technologies such as dissolved air flotation (DAF) to improve treatment efficiency [32].

Table 2.

Initial characterization of the municipal effluent compared to the maximum admissible values (MAV) for discharge to the sewer.

3.2. Water–Air Saturation and Oxygen Transfer Efficiency

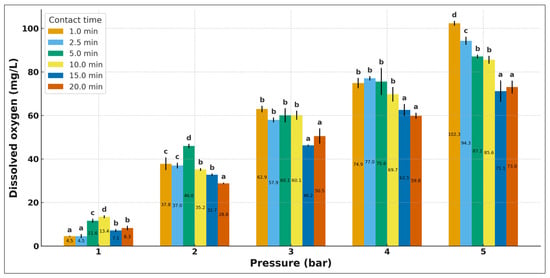

The oxygen transfer efficiency in the DAF system was evaluated using water–air saturation at pressures of 1–5 bar and contact times of 1–20 min. Figure 2 shows a directly proportional relationship between pressure and dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration, consistent with Henry’s law. At low pressures (1–2 bar), the process is controlled by dissolution kinetics, while at higher pressures (3–5 bar) the curves tend to converge, indicating the approach to gas–liquid equilibrium. This behaviour is attributed to the increase in oxygen solubility with increasing gas partial pressure, which favours the formation and stability of microbubbles during flotation. The maximum value recorded (~100 mg/L at 5 bar) and the stabilization of the system between 5 and 7 min confirm rapid saturation, with efficiencies above 80%. These results, in agreement with those reported by Nikfar et al. [28], Pérez-Guzmán et al. [29] and Huang et al. [34], show that operating between 3 and 5 bar optimizes oxygen dissolution and reduces energy consumption, consolidating the efficiency of the DAF in effluent treatment.

Figure 2.

Variation in dissolved oxygen concentration as a function of pressure and contact time. Mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). Different superscript letters above the bars indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

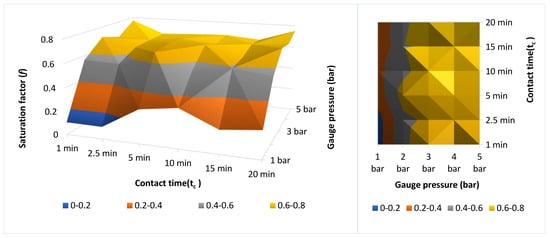

3.3. Determination of the Saturation Factor (f) and Operating Conditions

The determination of f allowed the evaluation of the oxygen dissolution efficiency in the DAF system under different operating conditions, including pressure (1–5 bar), contact time (1–20 min), and temperature. The results showed a directly proportional relationship between gauge pressure and the dissolved oxygen concentration, reaching maximum values of 102.3 mg/L and f = 0.8–0.9 at 5 bar and 19.3 °C, consistent with Henry’s law. At low pressures (1–2 bar), the process was limited by diffusive resistance, whereas at higher pressures the gas–liquid equilibrium was reached. Contact time exerted a positive influence up to approximately 5–7 min, after which stabilization of f was observed, indicating the establishment of an oxygen–water dynamic equilibrium.

Similarly, increasing the temperature from 19.3 °C to 36 °C reduced f from 0.8 to 0.7, confirming the lower solubility of oxygen at elevated temperatures, as reported in [3,34]. Overall, operating at 3–5 bar and 5–7 min at moderate temperatures (~20 °C) optimizes oxygen–water transfer, enabling saturation efficiencies above 75% and ensuring the generation of fine microbubbles that enhance the contaminant separation process. Table 3 summarizes the combined effect of operational variables on DAF performance, and Figure 3 presents the response surface illustrating the non-linear increase in the saturation factor (f) as pressure and contact time rise, until stabilization occurs around 0.78.

Table 3.

Effect of pressure and contact time on dissolved oxygen concentration and saturation factor in the DAF system.

Figure 3.

Surface and Contour Map: Saturation factor (f) vs. pressure (P) and contact time (tc).

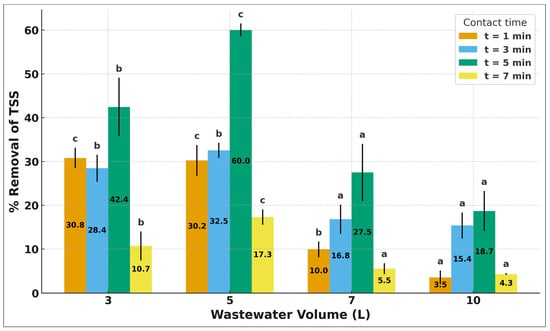

3.4. Removal of Total and Suspended Solids

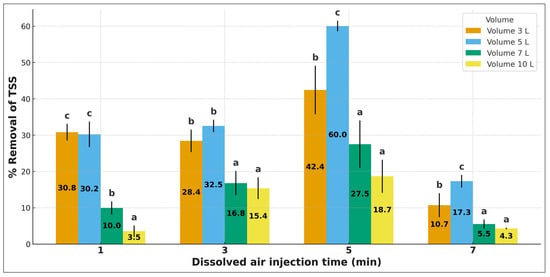

The DAF system exhibited high efficiency in removing solids from the municipal effluent. Total suspended solids (TSS) decreased from 590 mg/L to less than 120 mg/L (75–85% removal), while total solids (TS) were reduced to 200–250 mg/L, with removals close to 70%. Figure 4 shows that TSS removal increases with treated volume and dissolved-air injection time (tDAI), until reaching a dynamic equilibrium. The 5 min condition exhibits the best performance, indicating optimal microbubble generation and attachment. The 1- and 3 min times show lower efficiencies due to limited microbubble availability. At 7 min, removal decreases at higher treated volumes, likely due to bubble coalescence and reduced bubble density. In Figure 5, likewise, it is observed that the 5 L volume achieves higher removal values compared to the 3 L volume. A possible explanation is that, at 5 L, the ratio between available dissolved air and treated volume results in a more efficient microbubble distribution, enhancing particle–bubble attachment. In contrast, at 3 L, faster saturation and higher relative turbulence may limit microbubble stability and reduce their capacity to capture suspended solids, which leads to lower removal efficiencies.

Figure 4.

Shows that TSS removal increases with treated volume and dissolved-air injection time (tDAI), until reaching a dynamic equilibrium. The 5 min condition exhibits the best performance, indicating optimal microbubble generation and attachment. The 1- and 3 min times show lower efficiencies due to limited microbubble availability. At 7 min, removal decreases at higher treated volumes, likely due to bubble coalescence and reduced bubble density. Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different superscript letters above the bars indicate significant differences among contact times within each volume (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Removal of total suspended solids with respect to dissolved air injection time (tIAD) at different sample volumes. Mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). Superscript letters above the bars indicate significant differences among volumes at each injection time (p < 0.05).

The fact that the highest TSS removals occur under intermediate pressure and contact-time conditions confirms that the oxygen saturation optimum in Section 3.3 does not necessarily match the optimum for solid removal. Excess oxygen may lead to bubble coalescence or increased turbulence, reducing bubble–particle attachment efficiency. Similar behaviour has been reported by Nikfar et al. [28], Sinaga et al. [33], and Dos Santos et al. [26], who also observed removal efficiencies above 75%, demonstrating that DAF significantly outperforms conventional sedimentation (≤60%) in effluents with high turbidity and solids load.

Likewise, it is observed that the 5 L volume achieves higher removal values compared to the 3 L volume. A possible explanation is that, at 5 L, the ratio between available dissolved air and treated volume results in a more efficient microbubble distribution, enhancing particle–bubble attachment. In contrast, at 3 L, faster saturation and higher relative turbulence may limit microbubble stability and reduce their capacity to capture suspended solids, which leads to lower removal efficiencies (Figure 5).

Additionally, the presence of an extreme point in the TSS–injection time/volume curves is associated with the transition between optimal microbubble availability and subsequent bubble coalescence. At intermediate injection times, bubble density and dispersion promote maximum solid–bubble attachment; however, at higher times or volumes, coalescence reduces bubble surface area and flotation efficiency, producing the observed decline. This phenomenon aligns with previously documented DAF behaviour under variable saturation and hydrodynamic conditions.

3.5. Efficiency of the DAF System in Removing Organic Matter and Lipid Compounds from Municipal Effluent

The analysis of the experimental results confirmed the effectiveness of the DAF system in removing biodegradable and oxidizable organic matter, as well as lipid compounds present in municipal effluent. The most representative physicochemical parameters (BOD5, COD, O&G, TS, DS and pH) are summarized in Table 4, demonstrating the overall performance of the system under optimized conditions. BOD5 decreased from 360 mg/L to 40 mg/L, achieving a removal efficiency of 88.9%, while COD was reduced from 710 mg/L to 80 mg/L, corresponding to 88,7% removal. Oil and grease (O&G) concentrations decreased from 450 mg/L to 70 mg/L (84.4% removal), and total suspended solids (TSS) decreased from 590 mg/L to 60 mg/L (89.8% removal). These results confirm the strong capacity of DAF to remove colloidal and lipid-associated fractions of the organic load, consistent with observations by Pérez-Guzmán et al. [29] and Serrano-Meza et al. [30], who reported comparable efficiencies in optimized or hybrid systems.

Table 4.

Removal efficiency of the DAF system under optimal conditions.

The high removal of O&G reflects the strong hydrophobic affinity of microbubbles and their effectiveness in promoting flotation-based separation of lipid compounds, in agreement with findings reported by Huang et al. [34] and Gutiérrez-González et al. [31]. The pH of the effluent remained stable (7.2–7.6), and dissolved solids (DS) exhibited minimal variation (≈210 mg/L), a behaviour expected due to the physicochemical nature of the flotation process. These trends are consistent with Obotey Ezugbe and Rathilal [3], Baker et al. [24], and Ortega-Blas et al. [3], who emphasize the limited capacity of DAF to remove dissolved solutes, highlighting the need for complementary technologies for advanced wastewater treatment.

4. Conclusions

The dissolved air flotation (DAF) system demonstrated high efficiency in removing organic pollutants and solids from municipal effluent, achieving reductions of 78% in BOD5, 65% in COD, and over 80% in oils and greases. The significant decrease in total suspended solids (≈85%) confirms the effectiveness of microbubbles as capture and transport agents for hydrophobic particles. The saturation factor (f ≈ 0.8) evidenced efficient gas–liquid transfer, optimized through the use of Raschig rings, which increased the interfacial surface area and reduced diffusive resistance. Optimal operating conditions were set between 3 and 5 bar and contact times of 5–7 min, maximizing kinetic efficiency without increasing energy consumption.

The process maintained a stable pH (7.0–7.6) and constant levels of dissolved solids, demonstrating its selectivity toward suspended and colloidal fractions. Overall, the results confirm DAF as a robust, efficient, and adaptable technology for advanced municipal wastewater treatment, with potential for integration into hybrid biophysical-chemical systems aimed at sustainable water reuse and mitigating urban environmental impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R.P.-Q., H.C.-D. and D.L.B.-L.; methodology, L.R.P.-Q., H.C.-D., D.L.B.-L., R.M.C.-F. and F.L.; software, F.L. and L.R.P.-Q.; validation, L.R.P.-Q., D.L.B.-L. and R.M.C.-F.; formal analysis, F.L., R.M.C.-F. and H.C.-D.; research, D.L.B.-L.; H.C.-D. and L.R.P.-Q.; resources, data curation, H.C.-D. and F.L.; writing: preparation of the original draft, L.R.P.-Q., H.C.-D. and D.L.B.-L.; Writing: Review and editing, L.R.P.-Q., H.C.-D., D.L.B.-L., R.M.C.-F. and F.L.; Visualization, R.M.C.-F. and F.L.; Supervision, L.R.P.-Q. and H.C.-D.; Funding acquisition, F.L. and L.R.P.-Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has not received external funding. The funding is provided through the Vice-Rectorate for Research of UNAMBA, using resources from the mining canon, over-canon, and mining royalties.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al-Tayawi, A.N.; Sisay, E.J.; Beszédes, S.; Kertész, S. Wastewater Treatment in the Dairy Industry from Classical Treatment to Promising Technologies: An Overview. Processes 2023, 11, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Blas, F.M.; Ramos-Saravia, J.C.; Cossío-Rodríguez, P.L. Eliminación de nitrógeno y fósforo de las aguas residuales municipales mediante el cultivo de microalgas Chlorella sp. en consorcio. Water 2025, 17, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obotey Ezugbe, E.; Rathilal, S. Membrane Technologies in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Membranes 2020, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Adeniyi, A.G.; Adeniran, J.A.; Ogunniyi, S. A Systematic Literature Analysis of Water Pollution Sources in Nigeria. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Yousaf, M.; Nasir, A.; Bhatti, I.A.; Mahmood, A.; Fang, X.; Jian, X.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Mahmood, N. Porous Eleocharis@MnPE Layered Hybrid for Synergistic Adsorption and Catalytic Biodegradation of Toxic Azo Dyes from Industrial Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariguamán, L.A.; Gómez, L.K.; Guerrero, L.E.; Moya, R.B. Treatment of Wastewater Generated in a Dairy Processing Plant in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Reincisol 2024, 3, 2311–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.S.; Mishra, J.; Ighalo, J.O. Rising Demand for Rain Water Harvesting System in the World: A Case Study of Joda Town, India. World Sci. News 2020, 146, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dharwal, M.; Parashar, D.; Shuaibu, M.S.; Abdullahi, S.G.; Abubakar, S.; Bala, B.B. Water Pollution: Effects on Health and Environment of Dala LGA, Nigeria. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 3036–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharnejad, H.; Khorshidi Nazloo, E.; Madani Larijani, M.; Hajinajaf, N.; Rashidi, H. Comprehensive Review of Water Management and Wastewater Treatment in Food Processing Industries. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 4779–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, S.; Wasko, C.; Sharma, A. Do Longer Dry Spells Associated with Warmer Years Compound the Stress on Global Water Resources? Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, B.; Amin, M.O.; Al-Hetlani, E. Polyoxometalate-Based Materials for Removal of Contaminants from Wastewater: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 10960–10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M.; Russo, F.; Macedonio, F.; Criscuoli, A.; Curcio, E.; Figoli, A. PVDF Membrane Preparation for Membrane Distillation and Crystallization: Use of Non-Toxic Solvents. Membranes 2025, 15, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Messaoudi, N.; El Mouden, A.; Fernine, Y.; El Khomri, M.; Bouich, A.; Faska, N.; Ciğeroğlu, Z.; Pinheiro, J.H.A.; Jada, A.; Lacherai, A. Green Synthesis of Ag2O Nanoparticles Using Punica granatum Leaf Extract for Sulfamethoxazole Adsorption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 81352–81369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen-Chiang, C.; Zhao, X.; Han, Y. Responsibility under International Law to Prevent Marine Pollution from Radioactive Waste. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 227, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimonda, A.; Kowalska, I. Water Recovery from Laundry Wastewater by Integrated Purification Systems. Membranes 2025, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afolalu, S.A.; Ikumapayi, O.M.; Ogedengbe, T.S.; Kazeem, R.A.; Ogundipe, A.T. Waste Pollution, Wastewater and Effluent Treatment Methods: An Overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 3282–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadeja, N.B.; Banerji, T.; Kapley, A.; Kumar, R. Water Pollution in India—Current Scenario. Water Secur. 2022, 16, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Yadav, P.; Pal, A.K.; Mishra, V. Water Pollutants: Origin and Status. In Sensors in Water Pollutants Monitoring; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Syakir Ishak, M.I.; Bhawani, S.A.; Umar, K. Natural and Anthropogenic Factors Responsible for Water Quality Degradation: A Review. Water 2021, 13, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, D.M.; Abbott, B.W.; Khamis, K.; Kelleher, C.; Lynch, I.; Krause, S.; Ward, A.S. Illuminating the ‘Invisible Water Crisis’. Hydrol. Process. 2022, 36, e14525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E. Advantages and Disadvantages of Techniques Used for Wastewater Treatment. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 17, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quist-Jensen, C.A.; Macedonio, F.; Drioli, E. Membrane Technology for Water Production in Agriculture: Desalination and Wastewater Reuse. Desalination 2015, 364, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Herazo, L.; Álvarez-Hernández, L.; Marín-Muñiz, J.; Zitácuaro-Contreras, I. Wastewater Treatment through Home Bioengineered Wetlands. J. Energy Eng. Optim. Sustain. 2024, 8, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.R.; Mohamed, R.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Aziz, H.A. Advanced Technologies for Poultry Slaughterhouse Wastewater Treatment: A Systematic Review. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2020, 42, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Cobo, L.E.; Alcázar-Espinoza, J.A.; Vera-Guerrero, D.I.; Verdugo-Arcos, J.A. Proposal for a Pilot-Scale Domestic Wastewater Treatment Plant. J. Econ. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 4, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, P.R.; Sacchi, G.D.; Daniel, L.A.; Reali, M.A.P. Treatment of Secondary Effluent Using Dissolved Air Flotation on a Pilot Scale. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 107033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmideder, S.; Thurin, L.; Kaur, G.; Briesen, H. Inline Imaging Reveals Evolution of Microbubble Size Distribution in DAF. Water Res. 2022, 224, 119027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikfar, M.H.; Parsaeian, H.; Amani Tehrani, A.; Kouhestani, A.; Masoumi Isfahani, H.; Bazargan, A. Two-Stage DAF Saturator for Improved Microbubble Production. Environ. Technol. 2021, 44, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Guzmán, S.M.; Hernández-Aguilar, E.; Rosas-Mendoza, E.S.; Alvarado-Lassman, A.; Méndez-Contreras, J.M. Effect of Saturation Pressure in Batch DAF Operation for Municipal Effluents. Trends Renew. Energy Sustain. 2024, 3, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Meza, A.; Vigueras-Cortes, J.M.; Allen, C.D. Municipal Wastewater Treatment in a Hybrid Biofiltration System. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 2024, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez González, E.C.; Sánchez Contreras, M.V.; Caldera Marín, Y. Dissolved Air Flotation with PAC for Poultry Wastewater. Boliv. J. Eng. 2020, 1, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Alegría, J.A.; Muñoz-España, E.; Flórez-Marulanda, J.F. Dissolved Air Flotation: A Review. TecnoLógicas 2021, 24, e2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, F.A.; Lubis, M.T.; Husin, A. Reduction of TSS, COD, Oil and Fat in Palm Oil Mill Waste Using DAF. J. Serambi Eng. 2022, 7, 4179–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wen, S.; Wan, Z.; Xin, H.; Li, K. Treatment of Oil-Containing Wastewater Using Air Flotation Coupled with Fine Filtration. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua (ANA). National Protocol for Monitoring Surface Water Quality; ANA: Lima, Peru, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- APHA; AWWA; WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; APHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).