Effects of SDS Surfactant on Oxygen Transfer in a Fine-Bubble Diffuser Aeration Column

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

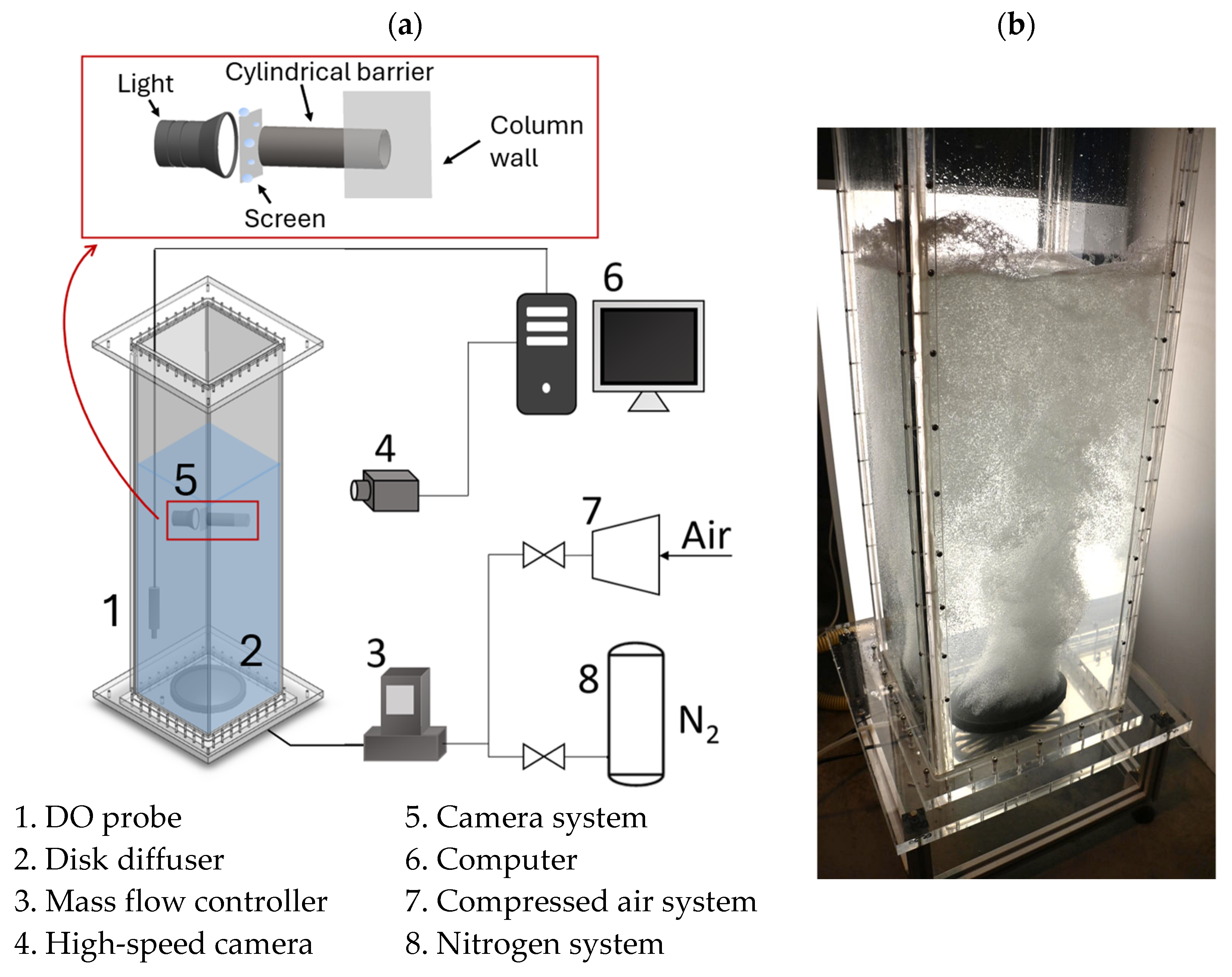

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient

2.3.2. Bubble Equivalent Diameter

2.3.3. Gas Holdup

2.3.4. Interfacial Area

2.3.5. Mass Transfer Coefficient

2.3.6. Experimental Uncertainty

3. Results

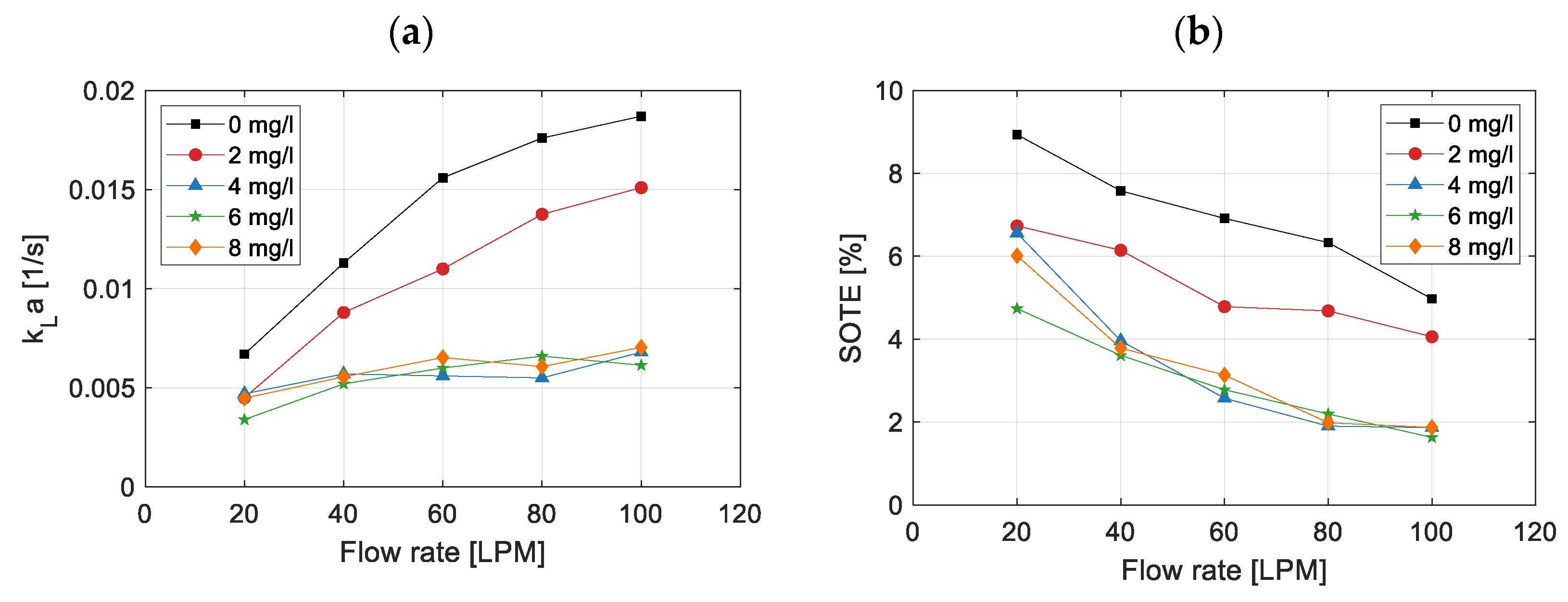

3.1. Effect on Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient

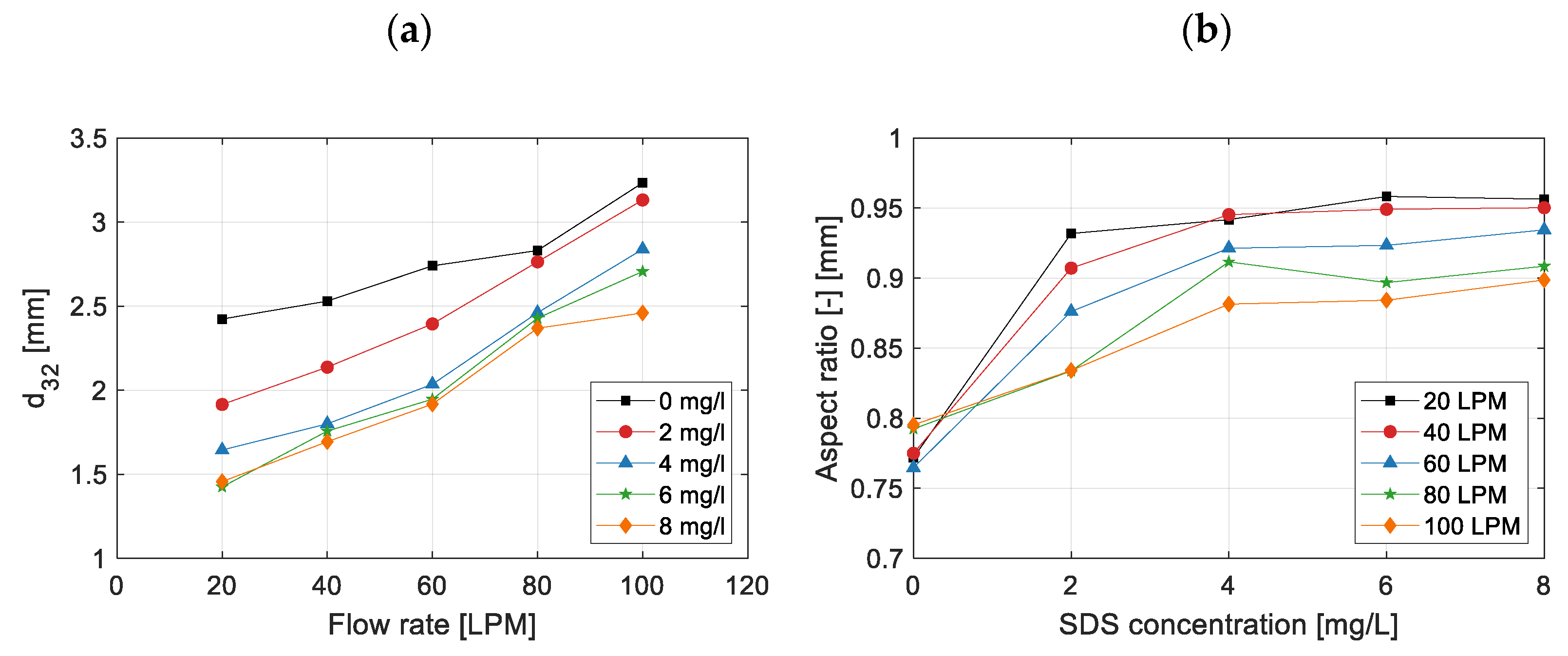

3.2. Effect on Bubble Size and Shape

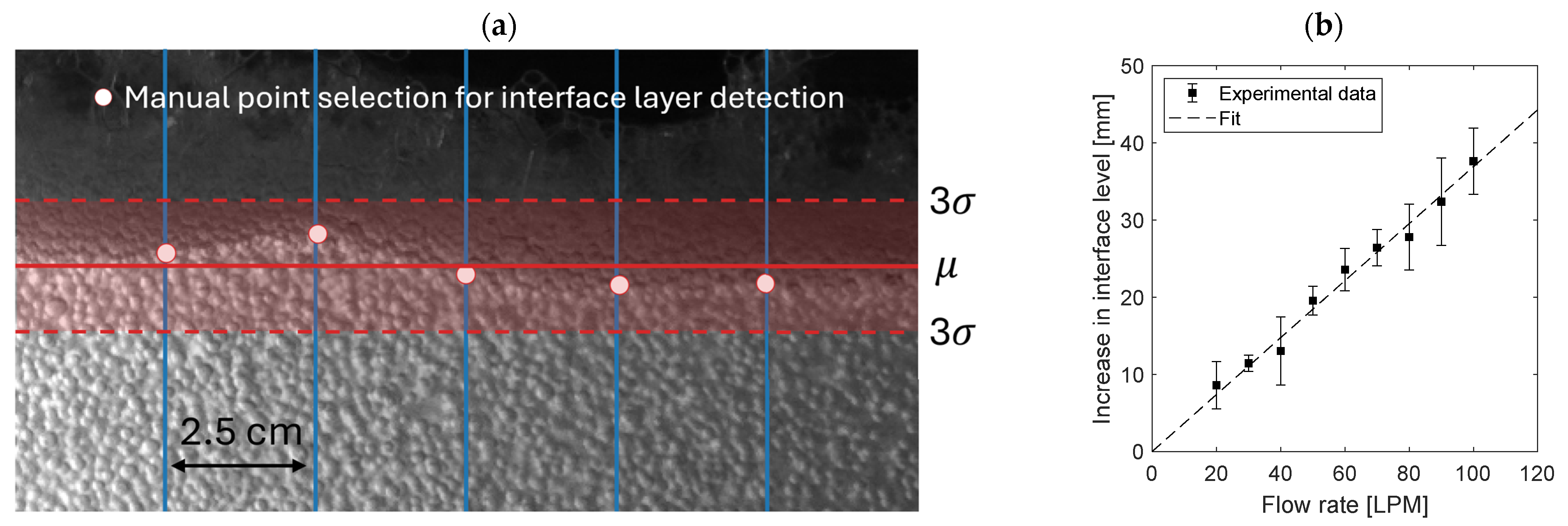

3.3. Effect on Gas Holdup

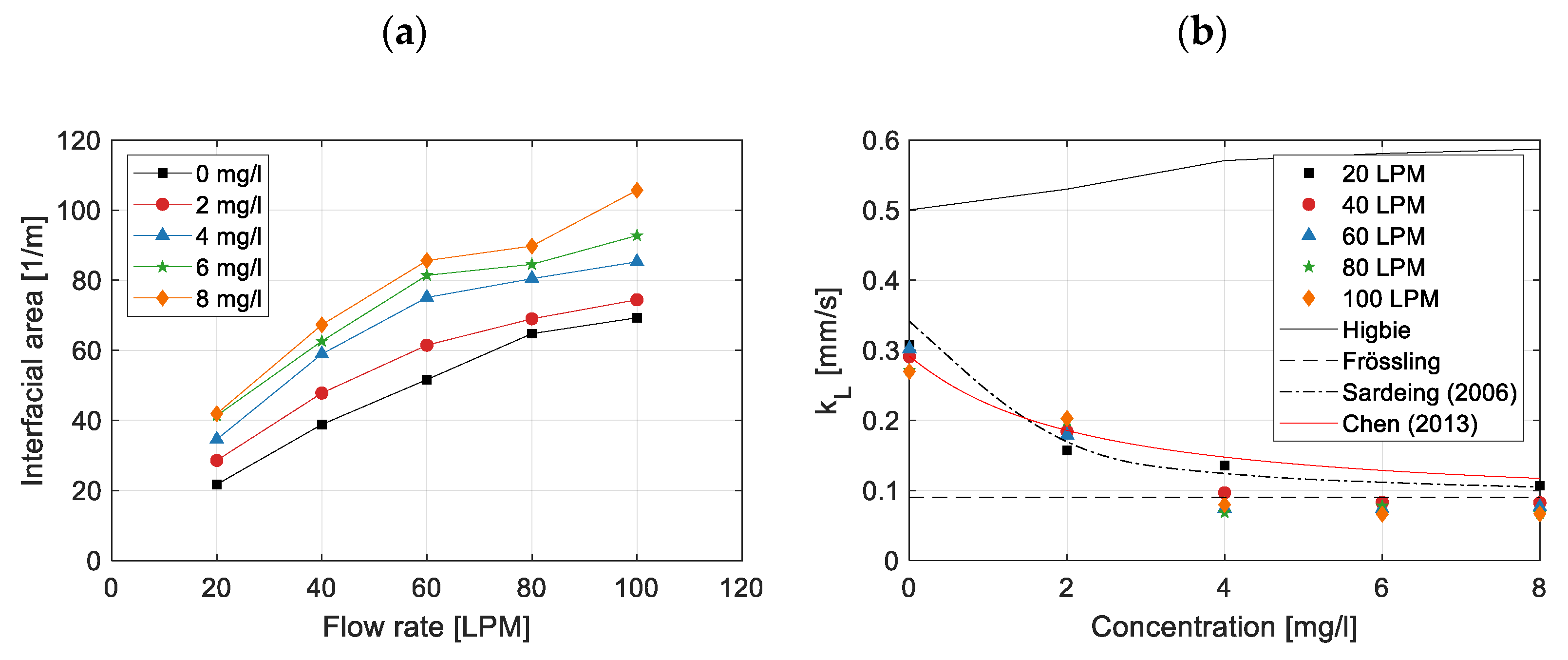

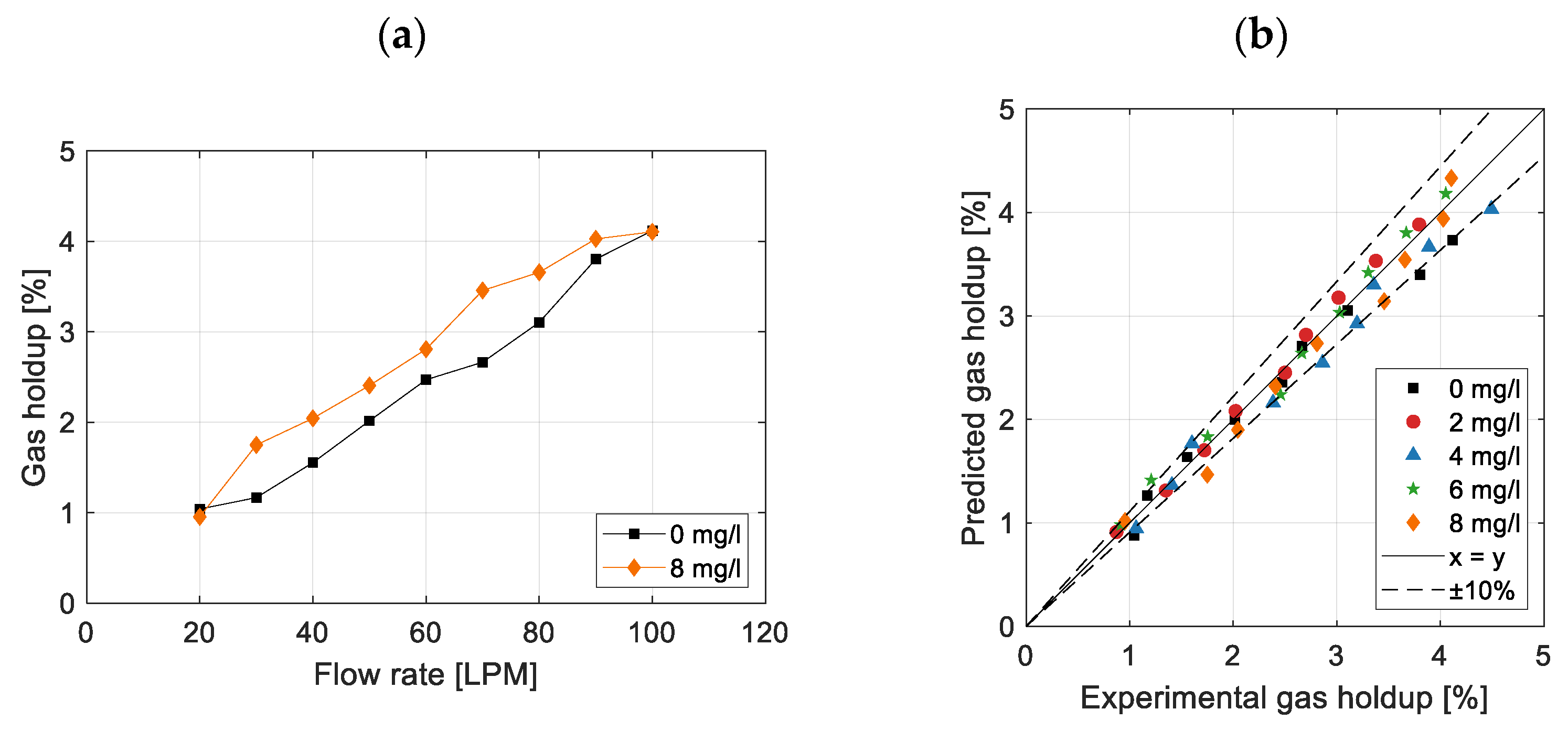

3.4. Effect on Interfacial Area

3.5. Effect on Mass Transfer Coefficient

- For bubble diameters smaller than 1.5 mm. In this range, is independent of surfactant concentration and corresponds to the mass transfer coefficient for rigid bubbles. In this regime, can be described using the Calderbank and Moo-Young’s correlation [52] or the Frössling correlation (Equation (10)).

- For bubble diameters between 1.5 mm and 3.5 mm. In this range, increases with bubble diameter, but in the presence of surfactants, this increase is significantly reduced. Consequently, varies approximately linearly between the limits corresponding to bubbles smaller than 1.5 mm and larger than 3.5 mm. This study falls within this range, which is the most critical due to the variability of with the bubble diameter. For this reason, it is essential to accurately measure the bubble diameter.

- For bubble diameters larger than 3.5 mm. For this range, does not depend on bubble diameter. The constant is determined by the interfacial coverage (), the mass transfer coefficient for a clean (surfactant-free) interface (, given by Higbie’s correlation, Equation (9)), and the mass transfer coefficient for a fully surfactant-saturated interface (, given by Equation (13)).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Obaideen, K.; Shehata, N.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Olabi, A.G. The Role of Wastewater Treatment in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Sustainability Guideline. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, Y.; Cockx, A.; Gillot, S.; Roustan, M.; Héduit, A. Oxygen Transfer Prediction in Aeration Tanks Using CFD. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007, 62, 7163–7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Pöpel, J. Surface Active Agents and Their Influence on Oxygen Transfer. Wat. Sci. Tech. 1996, 34, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, D.; Stenstrom, M.K. Surfactant Effects on α-Factors in Aeration Systems. Water Res. 2006, 40, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, S.S.; Orvalho, S.P.; Vasconcelos, J.M.T. Effect of Bubble Contamination on Rise Velocity and Mass Transfer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamnongwong, M.; Loubiere, K.; Dietrich, N.; Hébrard, G. Experimental Study of Oxygen Diffusion Coefficients in Clean Water Containing Salt, Glucose or Surfactant: Consequences on the Liquid-Side Mass Transfer Coefficients. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 165, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekoeian, S.; Aghajani, M.; Alavi, S.M.; Sotoudeh, F. Effect of Surfactants on Mass Transfer Coefficients in Bubble Column Contactors: An Interpretative Critical Review Study. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2021, 37, 585–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, D.; Huo, D.L.; Stenstrom, M.K. Effects of Interfacial Surfactant Contamination on Bubble Gas Transfer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2006, 61, 5500–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagawa, Y.; Takagi, S.; Matsumoto, Y. Surfactant Effect on Path Instability of a Rising Bubble. J. Fluid. Mech. 2014, 738, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubière, K.; Hébrard, G. Influence of Liquid Surface Tension (Surfactants) on Bubble Formation at Rigid and Flexible Orifices. Chem. Eng. Process. 2004, 43, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, T.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of Surfactant on Bubble Hydrodynamic Behavior under Flotation-Related Conditions in Wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 65, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painmanakul, P.; Loubière, K.; Hébrard, G.; Mietton-Peuchot, M.; Roustan, M. Effect of Surfactants on Liquid-Side Mass Transfer Coefficients. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 6480–6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeing, R.; Painmanakul, P.; Hébrard, G. Effect of Surfactants on Liquid-Side Mass Transfer Coefficients in Gas-Liquid Systems: A First Step to Modeling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2006, 61, 6249–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Guo, K.; Zheng, L.; Liu, C. A Mathematical Model for Single CO2 Bubble Motion with Mass Transfer and Surfactant Adsorption/Desorption in Stagnant Surfactant Solutions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 308, 122888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, G.; Clergerie, N.; Hébrard, G.; Dietrich, N. Modeling Oxygen Mass Transfer in Surfactant Solutions Considering Hydrodynamics and Physico-Chemical Phenomena. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 304, 121076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Guo, K.; Zheng, L.; Xiang, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, C. Experimental Study of the Effect of the Surfactant on the Single Bubble Rising in Stagnant Surfactant Solutions and a Mathematical Model for the Bubble Motion. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 9514–9527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Li, C.; Yan, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L. Prediction of Bubble Terminal Velocity in Surfactant Aqueous Solutions. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.; Das, M.K. Effects of Surface-Active Agents on Bubble Growth and Detachment from Submerged Orifice. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 179, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Abuín, A.; Gómez-Díaz, D.; Navaza, J.M.; Sanjurjo, B. Effect of Surfactant Nature upon Absorption in a Bubble Column. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 4484–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, J.M.T.; Rodrigues, J.M.L.; Orvalho, S.C.P.; Alves, S.S.; Mendes, R.L.; Reis, A. Effect of Contaminants on Mass Transfer Coefficients in Bubble Column and Airlift Contactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2003, 58, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmia, A.C.; Idouhar, M.; Wongwailikit, K.; Dietrich, N.; Hébrard, G. Impact of Cellulose and Surfactants on Mass Transfer of Bubble Columns. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2019, 42, 2465–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzbour, S.; Maniscalco, F.; Buffo, A.; Vanni, M.; Grau, F.X.; Gourich, B.; Stiriba, Y. Effects of SDS Surface-Active Agents on Hydrodynamics and Oxygen Mass Transfer in a Square Bubble Column Reactor: Experimental and CFD Modeling Study. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2023, 165, 104486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanogo, B.; Essid, A.; Tauleigne, B.; Carvajal, G.D.M.; Ursu, A.V.; Marcati, A.; Vial, C. Exploring the Impact of Proteins and Surfactant on Oxygen Mass Transfer in Gas-Liquid Bioreactors: An Experimental Investigation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 305, 121146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcclure, D.D.; Lee, A.C.; Kavanagh, J.M.; Fletcher, D.F.; Barton, G.W. Impact of Surfactant Addition on Oxygen Mass Transfer in a Bubble Column. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2015, 38, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Hu, W.; Yuan, X.; Yu, K. Effect of Surfactant Type on Interfacial Area and Liquid Mass Transfer for CO2 Absorption in a Bubble Column. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 23, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Corvalan, C.M.; Chew, Y.M.J.; Huang, J.Y. Coalescence of Small Bubbles with Surfactants. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 196, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharpour, M.; Mehrnia, M.R.; Mostoufi, N. Effect of Surface Contaminants on Oxygen Transfer in Bubble Column Reactors. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 49, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, T.; al Ma Awali, S.M.; Brennan, B.; Briciu-Burghina, C.; Tajparast, M.; Passos, T.M.; Durkan, J.; Holland, L.; Lawler, J.; Nolan, K.; et al. Oxygen Transfer of Microbubble Clouds in Aqueous Solutions—Application to Wastewater. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 257, 117693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, G.H.; Fan, H.; Li, M.; Luo, T.; Qi, L.; Wang, H. Effects of Surfactant Contamination on Oxygen Mass Transfer in Fine Bubble Aeration Process. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Díaz, D.; Navaza, J.M.; Sanjurjo, B. Interfacial Area Evaluation in a Bubble Column in the Presence of a Surface-Active Substance. Comparison of Methods. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 144, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Heber, R.; Oleshova, M.; Reinecke, S.F.; Meier, M.; Taş, S.; Hampel, U.; Lerch, A. Population Balance Modeling-Assisted Prediction of Oxygen Mass Transfer Coefficients with Optical Measurements. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 64, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frössling, N. The Evaporation of Falling Drops. Gerlands Beitr. Geophys. 1938, 52, 170–216. [Google Scholar]

- Higbie, R. The Rate of Absorption of a Pure Gas into a Still Liquid during Short Periods of Exposure. Trans. AIChE 1935, 31, 365–389. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, D.; Jin, W.; Xu, F.; Gao, Y.; Shi, W.; Ren, H. Investigation of Surfactant Effect on Ozone Bubble Motion and Mass Transfer Characteristics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Wang, J. New Insights into the Effect of Surfactants on Oxygen Mass Transfer in Activated Sludge Process. J Env. Chem Eng 2020, 8, 104409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.D.; Neeson, M.J.; Dagastine, R.R.; Chan, D.Y.C.; Tabor, R.F. Measurement of Surface and Interfacial Tension Using Pendant Drop Tensiometry. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2015, 454, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Skoufis, A.; Denning, T.; Qi, J.; Dagastine, R.; Tabor, R.; Berry, J. OpenDrop: Open-Source Software for Pendant Drop Tensiometry Contact Angle Measurements. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, V.C.; Lafuente, J.; Baeza, J.A. Activated Sludge Model 2d Calibration with Full-Scale WWTP Data: Comparing Model Parameter Identifiability with Influent and Operational Uncertainty. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 1271–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Civil Engineers. Measurement of Oxygen Transfer in Clean Water; The Society; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 1993; ISBN 087262885X. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Y.T.; Kelkar, B.G.; Godbole, S.P.; Deckwer, W.-D. Design Parameters Column Reactors Estimations for Bubble Column Reactors. AIChE J. 1982, 28, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van’t Riet, K.; Tramper, J. Basic Bioreactor Design, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Szyszka, D. Critical Coalescence Concentration (Ccc) for Surfactants in Aqueous Solutions. Minerals 2018, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watcharasing, S.; Kongkowit, W.; Chavadej, S. Motor Oil Removal from Water by Continuous Froth Flotation Using Extended Surfactant: Effects of Air Bubble Parameters and Surfactant Concentration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 70, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Jiang, H.; Xie, J.; Xiang, G. Comparison and Mechanism Analysis of Three-Phase Contact Formation onto Hydrophilic/Hydrophobic Mineral Surfaces in the Presence of Cationic/Anionic Surfactants during Flotation Process. Minerals 2022, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraveji, M.K.; Pasand, M.M.; Davarnejad, R.; Chisti, Y. Effects of Surfactants on Hydrodynamics and Mass Transfer in a Split-Cylinder Airlift Reactor. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 90, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcclure, D.D.; Deligny, J.; Kavanagh, J.M.; Fletcher, D.F.; Barton, G.W. Impact of Surfactant Chemistry on Bubble Column Systems. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2014, 37, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, G.; Xu, F.; Le Men, C.; Hébrard, G.; Dietrich, N. Gas-Liquid Mass Transfer around a Rising Bubble: Combined Effect of Rheology and Surfactant. Fluids 2021, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, S.; Fan, J. Effect of Surfactants on Gas Holdup in Shear-Thinning Fluids. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 2017, 9062649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Baserba, M.; Rosso, D.; Odize, V.; Rahman, A.; Van Winckel, T.; Novak, J.T.; Al-Omari, A.; Murthy, S.; Stenstrom, M.K.; De Clippeleir, H. Increasing Oxygen Transfer Efficiency through Sorption Enhancing Strategies. Water Res. 2020, 183, 116086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomiyama, A.; Kataoka, I.; Zun, I.; Sakaguchi, T. Drag Coefficients of Single Bubbles under Normal and Micro Gravity Conditions. JSME Int. J. Ser. B Fluids Therm. Eng. 1998, 41, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, G.; Benaissa, S.; Le Men, C.; Pimienta, V.; Hébrard, G.; Dietrich, N. Effect of Surfactant Lengths on Gas-Liquid Oxygen Mass Transfer from a Single Rising Bubble. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 247, 117102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderbank, P.H.; Moo-Young, M.B. The continuous phase heat and mass transfer properties of dispersions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1961, 16, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.; Behnisch, J.; Trippel, J.; Engelhart, M.; Wagner, M. Oxygen Transfer in Two-Stage Activated Sludge Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water 2021, 13, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prades-Mateu, O.; Monrós-Andreu, G.; Torró, S.; Martínez-Cuenca, R.; Chiva, S. Effects of SDS Surfactant on Oxygen Transfer in a Fine-Bubble Diffuser Aeration Column. Water 2025, 17, 3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243473

Prades-Mateu O, Monrós-Andreu G, Torró S, Martínez-Cuenca R, Chiva S. Effects of SDS Surfactant on Oxygen Transfer in a Fine-Bubble Diffuser Aeration Column. Water. 2025; 17(24):3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243473

Chicago/Turabian StylePrades-Mateu, Oscar, Guillem Monrós-Andreu, Salvador Torró, Raúl Martínez-Cuenca, and Sergio Chiva. 2025. "Effects of SDS Surfactant on Oxygen Transfer in a Fine-Bubble Diffuser Aeration Column" Water 17, no. 24: 3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243473

APA StylePrades-Mateu, O., Monrós-Andreu, G., Torró, S., Martínez-Cuenca, R., & Chiva, S. (2025). Effects of SDS Surfactant on Oxygen Transfer in a Fine-Bubble Diffuser Aeration Column. Water, 17(24), 3473. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243473