Abstract

The influence of light on nutrient removal in microalgae–bacteria biofilm systems containing polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs) remains unclear under low-carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio wastewater. This study investigated the effects of different light energy density (Es, 16.23–1101.61 J/gVSS) on the system performance and microbial community of a phototrophic simultaneous nitrification–denitrification phosphorus removal biofilm (P-SNDPRB) system treating wastewater with C/N ratios of 3.19–3.92. At Es below 367.22 J/gVSS, denitrification was the main nitrogen removal pathway, exceeding 82% total nitrogen removal. With increasing Es, nitrogen assimilation increased, while total nitrogen removal declined, remaining above 65%. Phosphorus removal was dependent on phosphorus-accumulating metabolism, achieving exceeding 90% phosphorus removal at Es below 367.22 J/gVSS. However, effluent phosphorus concentrations exceeded 0.5 mg/L at higher Es due to elevated glycogen-accumulating organism (GAO) activity and photoinhibition. Excessive light induced reactive oxygen species accumulation, inhibiting cellular activity and causing bacterial death in flocs. In contrast, the biofilm mitigated light stress, preserving the activity of PAOs, GAOs, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria across different Es levels. These findings demonstrate that P-SNDPRB systems exhibit resilience to fluctuating light conditions, enabling effective nutrient removal in low-C/N wastewater and offering insights into optimizing light management for microalgae-assisted treatment processes.

1. Introduction

Conventional biological nutrient removal (CBNR) processes have been utilized in municipal wastewater treatment for over a century [1]. However, their high energy consumption and significant greenhouse gas emissions have come under increasing public scrutiny. In CBNR processes, mechanical aeration accounts for the largest share of energy expenditure, typically representing 40–70% of operational costs. The carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted by these processes contributes approximately 1.6% of global greenhouse gas emissions [2,3]. The introduction of microalgal processes has effectively addressed both aeration energy demands and CO2 emissions [4,5]. However, these processes require larger surface areas and may exhibit lower nutrient removal efficiency compared to CBNR [6]. Previous studies have shown that microalgal–bacterial consortia (MBC) systems outperform standalone microalgal systems in nutrient removal from wastewater [7]. Unlike CBNR, MBC systems rely on the synergistic interactions between microalgae and bacteria to facilitate nutrient removal [8]. In this process, microalgae supply oxygen (O2) to bacteria while fixing the CO2 produced by bacterial metabolism, simultaneously absorbing inorganic nutrients such as ammonia (-N) for their growth [9]. However, the application of this system is limited by suboptimal nutrient removal performance in domestic wastewater with low carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratios.

In recent years, photo-enhanced biological phosphorus removal (PEBPR) systems have efficiently removed organic matter and phosphorus by integrating polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs) with microalgae [10,11]. These systems offer advantages such as low energy consumption and superior sedimentation performance. The system operates under alternating light–dark cycles and low hydraulic retention time (HRT) conditions, but exhibits limited nitrogen removal efficiency [11]. Carvalho et al. [12] improved nitrogen removal by incorporating nitrification and denitrification processes into the PEBPR system. However, this approach struggles with treating wastewater with a low C/N ratio due to insufficient denitrification efficiency. Meng et al. [13] developed a photosynthetic synchronous nitrification–denitrification phosphorus removal system (P-SNDPR) by integrating denitrification and phosphorus removal within the PEBPR system, effectively treating low-C/N-ratio wastewater. In the P-SNDPR system, photosynthetic autotrophic algae utilize energy derived from intracellular polyphosphate (Poly-P) and glycogen hydrolysis. During the dark phase, they release phosphorus and assimilate volatile fatty acids (VFAs), converting these into polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). During the light phase, microalgae consume CO2 produced by PAOs to release O2, assimilating some

-N for intracellular protein synthesis [13]. The remaining

-N is oxidized to

-N by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and further removed through denitrification and phosphorus uptake by PAOs. Although the P-SNDPR system effectively treated low-C/N ratio wastewater, it proved ineffective for municipal wastewater treatment [13]. As a result, the photosynthetic synchronous nitrification–denitrification phosphorus removal biofilm (P-SNDPRB) system was developed, demonstrating excellent pollutant removal efficiency [14]. However, the P-SNDPRB system has only been tested at the laboratory scale, with no reports on its applicability in practical environmental settings.

In practical operational environments, light conditions are the most variable parameter compared to controlled laboratory settings [15]. Light exposure, a key factor influencing dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations and bacterial metabolic processes in the MBC system, includes aspects such as light intensity, wavelength, photoperiod, and wastewater turbidity [15,16]. While increased light intensity typically promotes enhanced algal activity, the impact of light on bacterial metabolic activity remains uncertain [17]. Arcila et al. [18] observed that the municipal wastewater treatment efficiency of the MBC system was significantly lower under high light intensity (600 W/m2) compared to low light intensity (300 W/m2). Furthermore, elevated light intensity may negatively affect the metabolic activity of nitrifying bacteria. Subsequent studies corroborated this finding, suggesting that light exposure may inhibit nitrification by suppressing the expression of specific genes [19,20]. During denitrification in the MBC system, light exposure may partially oxidize cytochrome c—the intermediate electron carrier for denitrifying enzymes—thereby inhibiting the denitrification process [21,22]. Additionally, light exposure suppresses the translational response of PAOs and glycogen-accumulating organisms (GAOs) [14]. These studies collectively indicate that light exerts an inhibitory effect on functional bacteria in activated sludge systems.

However, previous studies have primarily focused on the effects of light intensity on MBC system performance, with limited attention to the potential inhibitory effects of light on bacterial metabolism [11,23,24]. Furthermore, to ensure the economic feasibility of wastewater treatment systems, natural sunlight (exceeding 1000–2000 W/m2) is typically preferred over artificial light sources [25,26,27]. Nonetheless, most investigations have concentrated on low light intensities (below 600 W/m2) in the MBC system. In the P-SNDPRB system, functional bacteria commonly found in activated sludge systems are employed for denitrification and phosphorus removal [14]. Consequently, further expansion of their application requires a thorough evaluation of how varying light conditions influence both system performance and microbial metabolism within P-SNDPRB systems.

This study investigated the effects of varying light conditions on the performance and bacterial metabolism of the P-SNDPRB system treating low C/N ratio municipal wastewater. This study involved 24 batch experiments with light exposure settings ranging from 32.41 to 1101.61 J/mgVSS to assess pollutant removal efficiency under different light conditions and evaluate the system’s feasibility for practical applications. By analyzing a typical operational cycle within the P-SNDPRB system, the impact of light conditions on pollutant transformation processes was explored. Additionally, flow cytometry (FCM) technology was used to examine how different light conditions affected bacterial physiological activity. The BONCAT-FISH technique was employed to investigate changes in the metabolic activity of key functional bacteria under varying light conditions, providing insights into the mechanisms that enable the P-SNDPRB system to achieve efficient pollutant removal in dynamic light environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Batch Experiments

To evaluate the impact of varying light conditions on the performance of the P-SNDPRB system and to assess its potential applicability to municipal wastewater treatment, a series of 24 controlled batch experiments were conducted (Table 1). The seed sludge was obtained from the P-SNDPRB system [14]. The biofilm adhering to polyurethane foam was carefully removed, homogenized, and evenly divided into 24 portions before being placed into 100 mL serum bottles. In parallel, the dosage of flocs was adjusted according to the specific requirements of each experiment. Each batch experiment lasted for one full operational cycle and consisted of three distinct phases: (i) a dark phase of 1.5 h, (ii) a light phase of variable duration ranging from 6 to 18 h depending on the experimental design, and (iii) a settling and discharge phase of 1 h.

Table 1.

Operating conditions for batch experiments.

During the light phase, light was supplied by light-emitting diode (LED) lamps, with the number of lamps adjusted to achieve four distinct irradiance levels of 120, 295, 595, and 1200 W/m2. The influent substrate was untreated municipal wastewater, representative of low-C/N-ratio municipal wastewater. Its detailed composition is summarized in Table 2. All experimental runs were conducted under strictly controlled ambient conditions at 22 ± 2 °C. This experimental setup ensured reproducibility and allowed for systematic evaluation of the interactions between light intensity, microbial activity, and pollutant removal in the P-SNDPRB system.

Table 2.

The composition of domestic wastewater.

Each batch experiment within a series would run continuously for seven days, with liquid and sludge samples taken from batch experiments on the third and seventh days. Reactor performance was monitored by measuring orthophosphate (–P),

–N, nitrate (–N), nitrite (–N), acetate (HAc), propionate (HPr), mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS), and mixed liquor volatile suspended solids (MLVSS). PHA, including poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB), poly-β-hydroxyvalerate (PHV), and poly-β-hydroxy-2-methylvalerate (PH2MV), as well as glycogen, were analyzed from sludge samples.

Light energy densities (Es, kJ/g VSS, Equation (1)) were calculated according to Wang et al. [19]

where V is the effective volume of the reactor (2 L); U is the effective irradiated area ratio (U = SCF/SLP, where SCF and SLP are the irradiated area of the reactor and the light plate, respectively); t is the irradiation time; and C is the MLVSS concentration (g/L).

P = (U × W × t)/(V × C)

2.2. Analysis of Nitrogen Removal Pathways

To determine the contributions of denitrification and assimilation to nitrogen removal under different light conditions, the sludge was washed with ultrapure water after completion of the batch experiments and transferred to serum bottles. The mixtures were incubated under helium aeration to maintain strictly anaerobic conditions, using the same wastewater and operating parameters as in the batch tests. Gas and liquid samples were collected throughout the reaction. The relative contributions of denitrification and assimilation to total nitrogen removal were quantified by analyzing the N2/N2O ratio in the gas phase at the end of the reaction and applying Equation (1) to Equation (2).

In the P-SNDPRB system, assimilation was an important pathway for N and P removal. To determine the contribution of microalgae and bacteria to N and P removal, the assimilation reactions of bacteria and microalgae are shown in Equations (1) and (2), where CH1.4O0.4N0.2P0.017 is for bacteria (Equation (2)) and CH1.78O0.36N0.12P0.01 is for algae (Equation (3)).

Assimilation by bacteria using acetate as an organic carbon source:

Assimilation by microalgae using CO2 as an inorganic carbon source:

2.3. Analytical Methods

The concentrations of COD, -P, -N, -N, -N, MLSS, and MLVSS were detected according to Standard Methods [28]. The contents of HAc, HPr, PHA, and glycogen were analyzed according to the previous studies [29]. N2O and N2 concentration were measured according to a previous study [30]. Total inorganic carbon (TIC) was measured using a TOC analyzer equipped with an ASI-L autosampler (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Light intensity was measured with a Li-250 light meter (Li-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA).

2.4. Flow Cytometry (FCM) Analysis

FCM combined with multiple fluorescent dyes was used to evaluate the physiological status and key metabolic activities of microorganisms in the P-SNDPRB system under different light conditions. Viable cells were distinguished using SYBR Green I/propidium iodide (SGI/PI; Invitrogen), while esterase activity was determined with 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate/PI (cFDA/PI; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Stock solutions were prepared and staining procedures were performed as previously described [31,32]. Programmed cell death (PCD) is a tightly regulated process essential for cellular homeostasis, but aberrant apoptosis is often associated with environmental stress and pathological states [32]. To examine apoptosis and necrosis in activated sludge bacteria following different light conditions, multiparameter FCM was conducted using an Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit (AV/PI; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DCFH-DA was employed to assess intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the light phase. Detailed protocols for single-cell preparation, staining conditions of activated sludge, and FCM analysis are provided in Test S1. Bioorthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT) was applied to identify metabolically active (BONCAT+) microorganisms. Following the method of Du and Behrens [33], samples were pretreated, stained, and quantified. In addition, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to detect key functional strains exhibiting translational activity in the P-SNDPRB system. For each sample, 100,000 particles were collected and analyzed using FlowJo V10.

2.5. Kinetic and Stoichiometric Parameters

The PHA/COD (Cmmol/mg) ratio was calculated as the amount of PHA synthesis during the dark phase, defined as the difference between the influent PHA concentration and the PHA concentration at the end of the dark phase, divided by the COD consumption, defined as the difference between the influent COD concentration and the COD concentration at the end of the dark phase. The ratios of P/COD (mg/mg) and Gly/COD (cmol/mg) were calculated by dividing the amounts of P released and glycogen reduction by the corresponding amounts of COD consumed during the dark phase, respectively. The P/PHA (mg/Cmmol) and Gly/PHA (Cmmol/Cmmol) ratios were calculated as the ratio of the change in P concentration and glycogen production to the amount of PHA decomposed at the end of the light phase.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Light Energy Density on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal Performance of the P-SNDPRB System

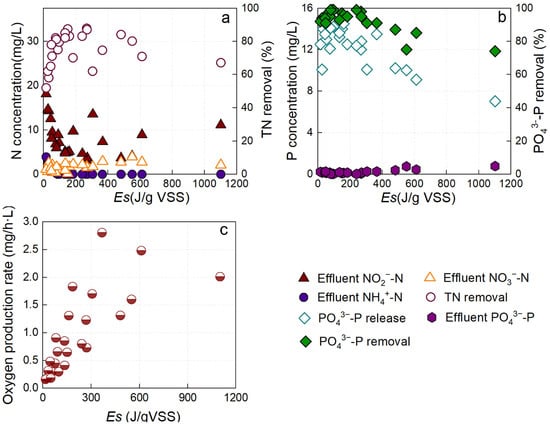

Batch experiments were conducted to evaluate the effect of light conditions on pollutant removal performance in the P-SNDPRB system (Figure 1). As Es increased, effluent

-N concentration consistently decreased, indicating enhanced

-N oxidation. At 48.6 J/gVSS of Es,

-N was completely oxidized, primarily to

-N, while only a small fraction was converted to

-N. When Es was below 160 J/gVSS, effluent

-N concentrations were decreased with increasing Es, with total nitrogen (TN) removal efficiency reaching a maximum of 87.2% (Figure 1a). In the Es range of 160–550 J/gVSS, effluent

-N concentrations and TN removal efficiency remained relatively stable, with the latter maintained above 82%. At a 1200 W/m2 of Es, photosynthetic O2 production was increased substantially, reducing the anoxic volume of the P-SNDPRB system and impairing denitrification (Figure 1c). Consequently, TN removal efficiency was decreased, though it still remained above 65%. These results demonstrate the robustness of the P-SNDPRB system in maintaining nitrogen removal under varying Es levels.

Figure 1.

Variations in

-N,

-N,

-N, and

-P concentrations; TN removal efficiency; and O2 production rate in the P-SNDPRB system under different Es values. (a) Nitrogen removal efficiency; (b) phosphorus removal efficiency; and (c) O2 production rate.

Phosphorus metabolism was strongly influenced by light intensity. When Es was below 367.22 J/gVSS, phosphorus release during the dark phase stabilized at 12–15 mg/L, ensuring efficient

–P removal exceeding 90% (Figure 1b). However, once Es exceeded 367.22 J/gVSS, phosphorus release was decreased to below 10 mg/L, leading to effluent phosphorus concentrations greater than 0.5 mg/L. This decrease may be attributed to the reduced metabolic activity of PAOs compared with GAOs under high Es levels, thereby compromising

-P removal. From a practical perspective, it is important to note that under natural sunlight, Es values in full-scale systems typically remain below 300 J/gVSS. This suggests that the P-SNDPRB system would maintain effective nitrogen and phosphorus removal under real-world operating conditions. Overall, these findings demonstrate that nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance is strongly dependent on light conditions. Under appropriate illumination (Es < 367.22 J/gVSS), the P-SNDPRB system achieves efficient and stable removal of nitrogen and phosphorus.

3.2. Effect of Light Energy Density on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal Pathways in the P-SNDPRB System

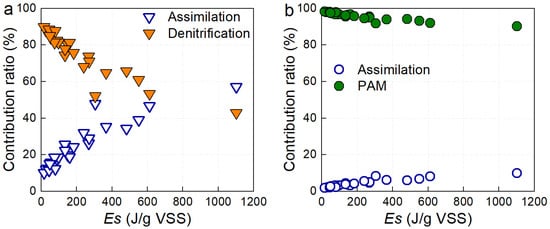

In the P-SNDPRB system, nitrogen removal was mediated primarily through denitrification and assimilation, while phosphorus removal relied on the polyphosphate-accumulating metabolism (PAM) pathway, with a minor contribution from assimilation [13]. As shown in Figure 2a, the relative contribution of denitrification to nitrogen removal was decreased as Es increased. When Es was below 612 J/gVSS, denitrification accounted for the dominant pathway, surpassing assimilation. However, once Es exceeded 612 J/gVSS, assimilation became the major contributor, overtaking denitrification. This shift can be attributed to two main factors. First, higher light intensity stimulated microalgal activity, enhancing

-N assimilation and simultaneously increasing O2 production [34]. The additional O2 reduced the size and persistence of anoxic zones, which are essential for denitrification. Second, higher Es has been reported to directly inhibit denitrification by causing photooxidation of cytochrome c, a key intermediate electron carrier in denitrifying enzymes [21,35]. Together, these effects explain the suppression of denitrification and the growing importance of assimilation at elevated Es levels.

Figure 2.

Nitrogen and phosphorus removal pathways in the P-SNDPRB system at different Es: (a) nitrogen removal pathway; (b) phosphorus removal pathway.

Phosphorus metabolism displayed a comparable trend. As shown in Figure 2b, assimilation and PAM contributed to phosphorus removal, but assimilation remained consistently minor relative to PAM across the full range of Es conditions tested. Even under extremely high light exposure, with Es approaching 1102.22 J/gVSS, phosphorus removal was still predominantly mediated by the PAM pathway (Figure 2b). This persistence underscored the metabolic versatility and ecological resilience of PAOs. At relatively low Es values, PAOs could exploit multiple electron acceptors for phosphorus uptake, including

–N and

–N generated during nitrification, as well as O2. At higher Es, O2 generated through microalgal photosynthesis became the preferred electron acceptor, ensuring that phosphorus removal remained effective despite reduced availability of anoxic niches.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that light influences the balance between denitrification and assimilation in nitrogen removal, while phosphorus removal remains robustly dependent on the PAM pathway. The capacity of PAOs to flexibly utilize different electron acceptors explains the system’s sustained phosphorus removal efficiency even under elevated Es levels, suggesting the adaptive potential of the P-SNDPRB system for variable light conditions.

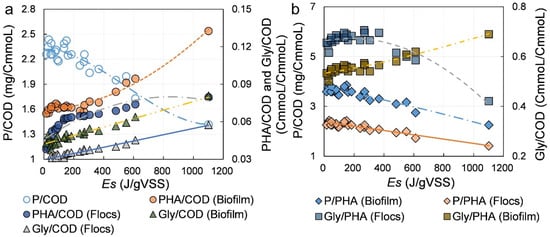

3.3. Effect of Light Energy Density on Pollutant Removal Mechanisms in the P-SNDPRB System

To further investigate the impact of light conditions on pollutant removal in the P-SNDPRB system, key metabolic parameters were examined in the flocs and the biofilm. As shown in Figure 3, during the dark phase, substantial

-P release was observed when Es was below 200 J/gVSS, which corresponded to a relatively high P/COD ratio. However, as Es increased beyond this threshold, the P/COD ratio was decreased. Under these conditions, the biofilm and flocs exhibited elevated PHA/COD and Gly/COD ratios with rising Es, despite notable differences in PHA and glycogen metabolism between the flocs and the biofilm. These results suggest that high Es suppresses phosphorus metabolic activity while promoting glycogen metabolism.

Figure 3.

Variation in stoichiometry number of the P-SNDPRB system at different Es levels: (a) the dark phase; (b) the light phase.

The enhancement of glycogen metabolism under elevated Es levels can be attributed to two main factors. First, increased GAOs activity likely occurred, as GAOs gain a competitive advantage over PAOs in environments with high DO concentrations and strong light inhibition [14,36]. Second, a possible metabolic shift in PAOs from the PAM pathway to glycogen-accumulating metabolism (GAM) pathway may take place under conditions of resource limitation or stress [37,38]. Nevertheless, given that actual municipal wastewater was used as influent in this study, such a shift within PAOs is unlikely to be the dominant mechanism. Therefore, the observed increase in glycogen metabolism in both sludge types is more plausibly driven by heightened GAO activity.

In the flocs, the P/PHA and Gly/PHA ratios decreased with increasing Es, indicating that light stress inhibited not only phosphorus metabolism but also the ability of glycogen metabolism to offset these effects. Previous studies have suggested that light exposure can oxidize intracellular compounds, with the energy released from PHA oxidation partially mitigating phototoxic stress [14,39]. In contrast, the biofilm matrix provided structural protection, buffering microorganisms from direct light exposure. Consequently, with increasing Es, the P/PHA ratio in the biofilm was declined, while the Gly/PHA ratio was increased.

The P-EBPR system centered on PAOs achieves efficient phosphorus removal only when Es is below 100 J/gVSS [14]. When Es exceeds this threshold, GAOs proliferate more readily than PAOs, resulting in reduced phosphorus removal efficiency [14]. The P-SNDPR system maintains effective nitrogen and phosphorus removal only when Es remains below 60 J/gVSS [13]. In contrast, the P-SNDPRB system demonstrates substantially greater light tolerance, sustaining efficient N and P removal even at Es values below 200 J/gVSS. This marked difference in phototolerance highlights the protective function of biofilms, which enable functional microorganisms to better withstand phototoxic stress and thereby enhance the resilience of the P-SNDPRB system under fluctuating light conditions.

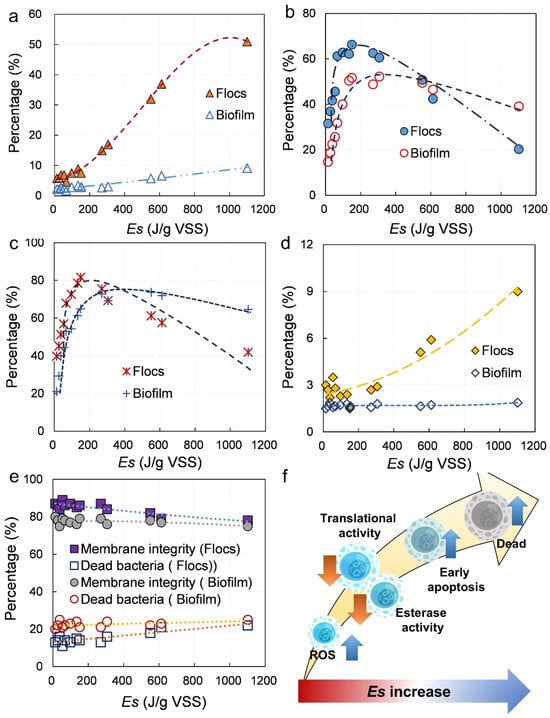

3.4. Effect of Light Energy Density on Microbial Physiological Activity in the P-SNDPRB System

To explore the mechanisms underlying light inhibition in the P-SNDPRB system, multiple fluorescent dyes were employed to characterize the physiological status of microorganisms under different light intensities (Figure 4). ROS, esterase activity, and translational activity were measured to provide insight into the balance between oxidative stress and microbial metabolic performance. When Es was below 160.65 J/gVSS, ROS levels in flocs remained relatively stable, suggesting that microorganisms were not subjected to excessive oxidative stress (Figure 4a). At this range, photosynthetic oxygen production was increased, which not only provided additional electron acceptors but also stimulated microbial activity (Figure 4b,c). As a result, esterase and translational activities in the flocs displayed an upward trend, reflecting an overall improvement in metabolic function.

Figure 4.

Changes in physiological activity of bacteria in the P-SNDPRB system: (a) ROS levels; (b) translational activity; (c) esterase activity; (d) early apoptosis; (e) membrane integrity; (f) mechanism of changes in physiological activity.

However, when Es exceeded 160.65 J/gVSS, a marked increase in ROS levels was increased in the flocs, suggesting the onset of oxidative stress. The excessive intracellular accumulation of ROS led to progressive oxidation of biomolecules, which in turn inhibited cellular metabolic pathways. As a result, esterase activity and translational activity were decreased, demonstrating that microbial functions were suppressed under elevated Es levels (Figure 4b,c). In contrast, samples in the biofilm exhibited greater resilience. ROS levels in the biofilm showed only minor fluctuations across the range of Es values tested, and even after esterase and translational activities reached peak levels, no significant decline was observed. These findings suggest that the spatial structure of biofilms provide a protective microenvironment, shielding cells from direct phototoxicity and ensuring more stable physiological performance.

Excessive ROS accumulation is known to damage proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, ultimately leading to bacterial mortality [40]. Microbial death can proceed through apoptosis or necrosis, with apoptosis being characterized by cell shrinkage, exposure of phosphatidylserine on the cell membrane, and progressive loss of membrane integrity [41]. In this study, when Es was below 160.65 J/gVSS, the proportion of early apoptotic cells in the flocs remained showed little change. By contrast, at Es values above 160.65 J/gVSS, the proportion of early apoptotic cells was increased from 3% to 7%, while necrotic cells were increased from 15% to 22% (Figure 4d,e). This sharp increase in apoptosis and necrosis strongly indicates that high light intensities impose lethal oxidative stress on flocs-associated microorganisms.

The community in the biofilm demonstrated a markedly different response. Due to the lower ROS levels observed in the biofilm, neither apoptosis nor necrosis increased significantly under elevated Es levels. Taken together, these results revealed a two-stage process of light inhibition in the flocs (Figure 4f): moderate Es stimulated microbial activity by enhancing photosynthetic oxygen production, whereas excessive Es elevates ROS beyond a critical threshold, suppressing metabolism and ultimately inducing apoptosis and necrosis. By contrast, the biofilm configuration provides structural and physiological buffering, enabling the P-SNDPRB system to maintain stable microbial activity and pollutant removal performance even under fluctuating light conditions.

3.5. Effect of Light Energy Density on Microbial Vitality and Population Distribution of P-SNDPRB Systems

3.5.1. Flocs

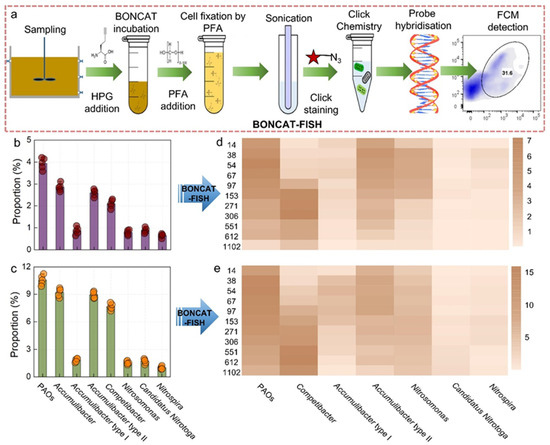

This study employed BONCAT-FISH to analyze the abundance of functional microorganisms and to characterize BONCAT+ microbial community dynamics in the flocs and biofilm of the P-SNDPRB system (Figure 5). BONCAT-FISH provides a culture-independent means of detecting metabolically active cells by incorporating synthetic amino acids into newly synthesized proteins, thereby enabling fine-scale discrimination between active and inactive populations. As shown in Figure 5a, BONCAT-FISH identified metabolically active bacteria in situ. Among these, Accumulibacter was the predominant group of PAOs, with abundances of 2.90% in the flocs and 9.51% in the biofilm. Further classification based on ppk1 gene typing distinguished two subgroups, Accumulibacter type I and type II, of which type II emerged as the dominant contributor to phosphorus removal in this study. In contrast, GAOs, represented primarily by Competibacter, were detected at lower abundances compared to PAOs, with 2.11% in the flocs and 8.61% in the biofilm. This distribution pattern may explain the strong phosphorus removal performance of the P-SNDPRB system under low Es conditions, particularly the higher resilience of the biofilm compared to the flocs.

Figure 5.

BONCAT-FISH detection process for functional bacteria in the P-SNDPRB system (a); changes in the abundance of functional bacteria (b,c) and BONCAT+ functional bacteria (d,e) in the flocs and the biofilm under different Es levels.

At Es values below 153 J/gVSS, the population abundance of BONCAT+ PAOs in the flocs remained relatively stable between 5 and 7%, consistently exceeding that of BONCAT+ Competibacter. This finding indicates robust phosphorus metabolic activity within this Es range (Figure 5c). BONCAT+ Accumulibacter type I and type II were detected under low Es levels; however, their abundances were decreased with rising Es. Specifically, BONCAT+ Accumulibacter type I showed a steady decline and eventually fell below the detection limit, suggesting its vulnerability to photoinhibition. In contrast, BONCAT+ Accumulibacter type II, although reduced in abundance, remained detectable even under elevated Es levels, reflecting its greater adaptability and ecological importance in maintaining phosphorus removal.

Since GAOs compete less effectively for O2 than PAOs, they tend to thrive in environments with higher DO concentrations, conditions that are favored under strong illumination [42]. Consistent with this, when Es was increased from 16.23 to 306.22 J/gVSS, the population abundance of BONCAT+ Competibacter was increased from 0.52% to 7.21%. Beyond 153 J/gVSS, BONCAT+ Competibacter surpassed BONCAT+ PAOs in abundance, suggesting that GAOs possess greater tolerance to light stress. However, when Es exceeded 306.22 J/gVSS, the population abundances of BONCAT+ PAOs and GAOs decreased. At the highest tested intensity Es (1102.22 J/gVSS), their abundances were reduced to below 2%, corresponding to diminished denitrification activity and a notable decline in the P-SNDPRB system.

In the flocs and the biofilm, the dominant NOB, Nitrospira and Nitrotoga, and the main AOB, Nitrosomonas, were present at low population abundances (<2%). However, their metabolic activities varied substantially across light conditions (Figure 5c). At a 38 J/gVSS of Es, the population abundance of BONCAT+ Nitrosomonas reached 3.9%, while the population abundance of BONCAT+ Nitrospira and Nitrotoga remained comparatively low at 0.31% and 0.99%, respectively. With increasing Es, the population abundances of BONCAT+ AOB and NOB were decreased steadily, but AOB were consistently more resilient. Previous studies have shown that light exposure suppresses Nxrt gene expression in NOB [19,20], which may account for the higher sensitivity to photoinhibition relative to AOB. Accordingly, the population abundance of BONCAT+ Nitrosomonas consistently exceeded that of NOB, suggesting the potential of the flocs to achieve partial nitrification. Notably, when Es exceeded 550 J/gVSS, the population abundances of BONCAT+ AOB and NOB were below 1%, indicating that nitrification was strongly inhibited in the flocs at high Es levels. This inhibition of nitrifiers also indirectly constrained the endogenous denitrification activities of PAOs and GAOs, given their reliance on

-N and

-N as electron acceptors.

3.5.2. Biofilm

The inhibitory effects of light on microbes of the biofilm differed from those observed in the flocs. As shown in Figure 5e, with the exception of the lowest Es tested (16.23 J/gVSS), increasing Es consistently reduced the population abundance of BONCAT+ PAOs in the biofilm. Nevertheless, even at a 1102.22 J/gVSS of Es, the abundance of BONCAT+ PAOs remained at 7.12%. This result demonstrates that PAOs in the biofilm preserved comparatively higher metabolic activity under varying Es levels, in contrast to the sharp declines observed in the flocs. At higher Es levels, the extremely low abundance of PAOs in the flocs suggested that PAOs in the biofilm became the dominant contributors to phosphorus removal, thereby sustaining favorable phosphorus removal performance in the P-SNDPRB system. Interestingly, the population abundance of BONCAT+ Competibacter in the biofilm was increased with rising Es, a trend likely driven by enhanced O2 production during photosynthesis, which in turn stimulated GAM. When Es exceeded 273 J/gVSS, the population abundance of BONCAT+ Competibacter surpassed that of BONCAT+ PAOs, thereby diminishing phosphorus removal efficiency. BONCAT+ Accumulibacter type I and type II in the biofilm followed trends similar to those observed in the flocs, with type I showing reduction in metabolic capacity under high Es, whereas type II maintained higher activity. These findings suggest that deliberate inoculation of sludge enriched in Accumulibacter type II may represent a practical strategy to preserve stable phosphorus metabolism during the P-SNDPRB system cultivation and operation.

The response of nitrifying bacteria in biofilms further highlights their resilience under varying light conditions. As Es and DO concentrations increased, the population abundance of BONCAT+ Nitrosomonas was increased, reaching 6.42% at a 153 J/gVSS of Es. Beyond this threshold, the population abundance of BONCAT+ Nitrosomonas was decreased but remained above 4%, suggesting that nitrification activity in the biofilm was well adapted to varying light conditions. In contrast, the population abundances of BONCAT+ Nitrospira and Nitrotoga were only 20–50% of that of BONCAT+ Nitrosomonas. Nonetheless, their variation patterns mirrored those of AOB. Given its higher O2 sensitivity, Nitrotoga may have gradually replaced Nitrospira. Collectively, these results indicate that complete nitrification was preserved within biofilms even at high light intensities, a capacity that was not sustained in the flocs.

In summary, BONCAT-FISH analyses revealed clear differences in microbial activity between the flocs and the biofilm. In the flocs, the metabolic activity of functional bacteria was progressively inhibited with increasing Es, and at high levels their activity was almost completely lost. By contrast, microorganisms in the biofilm retained sufficient metabolic activity to sustain nitrogen and phosphorus transformations, highlighting the ecological advantages of biofilm-based communities. This discrepancy indicates that the biofilm possesses greater resilience to light inhibition. In the P-SNDPRB system, the biofilm surface attached to the polyurethane sponge was exposed to light, with microbial metabolic activity influenced by light conditions (Figure S1). In contrast, the biofilm interior was shielded from light by both the polyurethane sponge material and the overlying biofilm [43]. As a result, the structural characteristics and microenvironmental conditions of the biofilm contribute to its enhanced tolerance to light exposure. In addition, synergistic metabolic interactions occur between microorganisms in the biofilm and flocs in the P-SNDPRB system. Under low Es levels, microalgae and cyanobacteria in the flocs and the biofilm produced O2 via photosynthesis, thereby supporting efficient nitrogen and phosphorus removal through denitrification and PAM processes mediated by PAOs and GAOs. Under high Es levels, the denitrification process was inhibited in the flocs but maintained in the biofilm, partially facilitated by O2 produced in the flocs and diffused into the biofilm matrix. These findings demonstrate that the P-SNDPRB system adapts its metabolic pathways in response to changing Es levels, thereby maintaining efficient pollutant removal under variable environmental conditions.

However, it remains uncertain whether the P-SNDPRB system can maintain high microbial metabolic activity and efficient nutrient removal over extended periods of operation. Therefore, future research should explore the long-term impact of varying light conditions on the functional stability and ecological interactions within the P-SNDPRB system. A deeper understanding of how light regulates microbial structure, metabolic activity, and synergistic interactions will provide a scientific basis for optimizing the design and operational management of the P-SNDPRB system. Such insights will form the basis for optimizing system design and operational management strategies, including biofilm engineering, illumination control, and targeted microbial enrichment. Ultimately, advancing this knowledge will facilitate the broader application of P-SNDPRB technology in wastewater treatment, contributing to the development of highly efficient, stable, and environmentally sustainable treatment processes.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the P-SNDPRB system maintains stable pollutant removal performance under varying light conditions due to the resilience of its biofilm-associated microbial communities. Nitrogen removal was dominated by denitrification at low Es levels, while assimilation became more prominent under higher Es levels, maintaining TN removal above 65%. Phosphorus removal was primarily mediated by the PAM pathway, achieving efficiencies exceeding 90% when Es was below 367.22 J/gVSS; however, increased GAOs activity and photoinhibition reduced performance at higher Es levels. Bacterial metabolism remained stable below 160.65 J/gVSS, while excessive ROS accumulation at higher Es levels inhibited metabolic processes and induced cell death. Compared with flocs, the biofilm exhibited stronger resistance to light stress, preserving the activity of PAOs, GAOs, AOB, and NOB. These findings underscore the adaptability of the P-SNDPRB system to fluctuating light conditions and its potential for efficient, stable, and sustainable treatment of municipal wastewater with low C/N ratios.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17233426/s1: Figure S1: Changes in filler profile during biofilm formation (A) and biofilm performance on nutrient removal (B) in the P-SNDPRB system. Figure S2: Circle gate process for sample detection by FCM-FISH; a. exclude tiny cell debris; b. exclude non-DNA large particles; c. circle positive regions; Figure S3: The response of amino acid type and concentration (A) and incubation time (B) to fluorescent staining in BONCAT; Figure S4: BONCAT-FISH circle gate process. P1 represents the percentage of BONCAT+ bacteria in total bacteria (A); P2 represents the percentage of specific functional bacteria in total BONCAT+ bacteria (B); Figure S5: Population abundance (a. flocs and b. biofilms) and composition (c) of microalgae in the P-SNDPRB system; Table S1: FCM-FISH and BONCAT-FISH probe sequences. References [33,44] are citied in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.M.; methodology, Z.H.; software, L.H.; validation, L.H.; formal analysis, Q.L.; investigation, Q.L., T.Z.; resources, W.W.; data curation, W.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H.; writing—review and editing, Q.M.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, W.Z.; project administration, T.Z.; funding acquisition, Q.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jiangsu provincial higher education basic science (Natural Science) research programme No. 25KJB560026.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Lei Hu and Qi Liu were employed by the company Jiangsu Urban Transport Planning and Design Institute Co., Ltd., while the author Weijia Zhao was employed by the company Yangzhou Urban Planning and Design Institute Company Limited by Shares. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Brdjanovic, D. Anticipating the next century of wastewater treatment. Science 2014, 344, 1452–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenstrom, M.K.; Larson, L.E.; Rosso, D. Aeration of large-scale municipal wastewater treatment plants: State of the art. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 57, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebuch, L.M.; Timmer, J.; Graaf, J.V.D.; Janssen, M.; Fernandes, T.V. Making waves: How to clean surface water with photogranules. Water Res. 2024, 260, 121875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.-C.; Hu, Y.-R.; He, Z.-W.; Li, Z.-H.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.C. Promoting symbiotic relationship between microalgae and bacteria in wastewater treatment processes: Technic comparison, microbial analysis, and future perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sanchez, C.; Baquerizo, G.; Moreno-Rodríguez, E. Analysing the influence of operating conditions on the performance of algal–bacterial granular sludge processes for wastewater treatment: A review. Water. Environ. J. 2023, 37, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, O.; Escalante, F.M.E.; De-Bashan, L.E.; Bashan, Y. Heterotrophic cultures of microalgae: Metabolism and potential products. Water Res. 2011, 45, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Ahuja, V.; Chandel, N.; Mehariya, S.; Kumar, P.; Vinayak, V.; Saratale, G.D.; Raj, T.; Kim, S.-H.; Yang, Y.-H. An overview on microalgal-bacterial granular consortia for resource recovery and wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Lei, Z. Wastewater treatment using microalgal-bacterial aggregate process at zero-aeration scenario: Most recent research focuses and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, A.; Kumar, P.S.; Varjani, S.; Jeevanantham, S.; Yaashikaa, P.R.; Thamarai, P.; Abirami, B.; George, C.S. A review on algal-bacterial symbiotic system for effective treatment of wastewater. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, V.C.F.; Freitas, E.B.; Silva, P.J.; Fradinho, J.C.; Reis, M.A.M.; Oehmen, A. The impact of operational strategies on the performance of a photo-EBPR system. Water Res. 2018, 129, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.Y.A.; Welles, L.; Siggins, A.; Healy, M.G.; Brdjanovic, D.; Rada-Ariza, A.M.; Lopez-Vazquez, C.M. Effects of substrate stress and light intensity on enhanced biological phosphorus removal in a photo-activated sludge system. Water Res. 2021, 189, 116606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.C.F.; Kessler, M.; Fradinho, J.C.; Oehmen, A.; Reis, M.A.M. Achieving nitrogen and phosphorus removal at low C/N ratios without aeration through a novel phototrophic process. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Peng, Y. Combined Phototrophic Simultaneous Nitrification-Endogenous Denitrification with Phosphorus Removal (P-SNDPR) System Treating Low Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio Wastewater for Potential Carbon Neutrality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 2902–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zeng, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Ma, B.; Peng, Y. Optimizing sludge retention time for sustainable photo-enhanced biological phosphorus removal systems: Insights into nutrient fate, microbial community, and bacterial phototolerance. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 351, 119839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbew, A.-W.; Qiu, S.; Amadu, A.A.; Qasim, M.Z.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Ge, S. Insights into the multi-targeted effects of free nitrous acid on the microalgae Chlorella sorokiniana in wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, J.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Xing, B. Photodegradation elevated the toxicity of polystyrene microplastics to grouper (Epinephelus moara) through disrupting hepatic lipid homeostasis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6202–6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, G.; Gao, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Tian, T.; Chen, W.; Gao, M. Effect of light intensity on nitrogen removal, enzymatic activity and metabolic pathway of algal-bacterial symbiosis in rotating biological contactor treating mariculture wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 417, 131872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila, J.S.; Buitrón, G. Influence of solar irradiance levels on the formation of microalgae-bacteria aggregates for municipal wastewater treatment. Algal Res. 2017, 27, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiu, S.; Guo, J.; Ge, S. Light Irradiation Enables Rapid Start-Up of Nitritation through Suppressing nxrB Gene Expression and Stimulating Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 13297–13305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Qiu, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Guo, J.; Ge, S. Effect of short-term light irradiation with varying energy densities on the activities of nitrifiers in wastewater. Water Res. 2022, 216, 118291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Bian, J.; Miao, S.; Xu, S.; Li, R.; Liu, R.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. Regulation of denitrification performance and microbial topology by lights: Insight into wavelength effects towards microbiota. Water Res. 2023, 232, 119434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilhac, C.; Sialve, B.; Pourcher, A.-M.; Ziebal, C.; Bernet, N.; Béline, F. Digestate color and light intensity affect nutrient removal and competition phenomena in a microalgal-bacterial ecosystem. Water Res. 2014, 64, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Ma, S.; Huang, Y.; Xia, A.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Bifunctional lighting/supporting substrate for microalgal photosynthetic biofilm to bio-remove ammonia nitrogen from high turbidity wastewater. Water Res. 2022, 223, 119041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Tang, Z.; Yang, D.; Dai, X.; Chen, H. Enhanced growth and auto-flocculation of Scenedesmus quadricauda in anaerobic digestate using high light intensity and nanosilica: A biomineralization-inspired strategy. Water Res. 2023, 235, 119893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizuki, S.; Kishi, M.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, G.; Toda, T. Effects of different light conditions on ammonium removal in a consortium of microalgae and partial nitrifying granules. Water Res. 2020, 171, 115445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Zheng, R.; Feng, Y.; Du, W.; Xie, C.; Gu, Y.; Liu, S. Anammox bacteria adapt to long-term light irradiation in photogranules. Water Res. 2023, 241, 120144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, S.; Ramasamy, S.; Pakshirajan, K. Mechanistic insights into nitrification by microalgae-bacterial consortia in a photo-sequencing batch reactor under different light intensities. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 321, 128752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 19th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, W. Enhancing nutrient removal in continuous-flow anaerobic/aerobic/anoxic processes treating low C/N ratios wastewater via side-stream light irradiation: NOB suppression and PHA metabolism stimulation. Water Res. 2026, 288, 124575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Dai, X.; Peng, Y. Combining simultaneous nitrification-endogenous denitrification and phosphorus removal with post-denitrification for low carbon/nitrogen wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 220, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wilkins, M. Flow cytometry for quantitation of polyhydroxybutyrate production by Cupriavidus necator using alkaline pretreated liquor from corn stover. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 295, 122254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Qian, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Fan, X.; Lu, B.; Tian, X.; Jin, W.; He, X.; Guo, W. Toxicity of Three Crystalline TiO2 Nanoparticles in Activated Sludge: Bacterial Cell Death Modes Differentially Weaken Sludge Dewaterability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4542–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Behrens, S.F. Tracking de novo protein synthesis in the activated sludge microbiome using BONCAT-FACS. Water Res. 2021, 205, 117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, I.M.; Sevillano-Rivera, M.C.; Pinto, A.J.; Guest, J.S. Impact of solids residence time on community structure and nutrient dynamics of mixed phototrophic wastewater treatment systems. Water Res. 2019, 150, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Lv, H.; Cui, B.; Zhou, D. Anammox activity improved significantly by the cross-fed NO from ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and denitrifying bacteria to anammox bacteria. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, M.; Hu, Z.; Duan, H.; De Clippeleir, H.; Al-Omari, A.; Hu, S.; Yuan, Z. Unravelling adaptation of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in mainstream PN/A process: Mechanisms and counter-strategies. Water Res. 2021, 200, 117239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Zeng, W.; Wang, B.; Fan, Z.; Peng, Y. New insights in the competition of polyphosphate-accumulating organisms and glycogen-accumulating organisms under glycogen accumulating metabolism with trace Poly-P using flow cytometry. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 385, 123915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, B.; Murgui, M.; Borrás, L.; Barat, R. New insights in the metabolic behaviour of PAO under negligible poly-P reserves. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 311, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, S.; Koppel, D.J.; Binet, M.T.; Jolley, D.F.; Simpson, S.L. Application of a Multispecies Pulse-Exposure Microalgal Bioassay to Assess Duration and Time-of-Day Influences on the Toxicity of Chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21155–21165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Steinman, A.D.; Xue, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xie, L. Effects of erythromycin and sulfamethoxazole on Microcystis aeruginosa: Cytotoxic endpoints, production and release of microcystin-LR. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 399, 123021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Oulego, P.; Alonso, S.; Díaz, M. Flow cytometric characterization of bacterial abundance and physiological status in a nitrifying-denitrifying activated sludge system treating landfill leachate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R 2017, 24, 21262–21271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira, M.; Oehmen, A.; Carvalho, G.; Eusébio, M.; Reis, M.A.M. The impact of aeration on the competition between polyphosphate accumulating organisms and glycogen accumulating organisms. Water Res. 2014, 66, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, D.; Wei, J.; Peng, Y.; Miao, L. Characterizing algal-bacterial symbiotic biofilms: Insights into coexistence of algae and anaerobic microorganisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 130966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zeng, W.; Li, N.; Guo, Y.; Peng, Y. Population Structure and Morphotype Analysis of “Candidatus Accumulibacter” Using Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization-Staining-Flow Cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2019, 85, e02943-189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).