Abstract

This study employed a comprehensive methodology to investigate the role of water utilities in the implementation of Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs) for water management such as Sustainable Drainage Systems. The methodological approach involved analyzing the Urban Nature Atlas database to evaluate European funding sources and stakeholders associated with NBSs for water management in Europe. Focusing on the Italian context, the study then conducted semi-structured interviews with Italian experts and mapped exemplary cases where Italian water utilities actively participated in NBS implementation efforts. The results provide insights into the factors hindering and driving NBS development by water utilities in Italy. Using an SWOT analysis, the study proposes five distinct roles that water utilities could potentially adopt to advance NBS. The article offers valuable insights for policymakers, urban planners, and water utility stakeholders, emphasizing the importance of multi-stakeholder collaboration to secure financing for NBSs.

1. Introduction

The early 2000s saw a substantial acceleration in urbanization phenomena [1], which was often not supported by sustainable planning policies. This has led to intense land consumption for human purposes and the progressive waterproofing of the territory. This trend exacerbates the impacts of climate change, increasing vulnerability to environmental, social, and economic pressures, notably flood risks due to reduced rainwater interception and infiltration capacities. Italy experiences alternating periods of water scarcity and extreme rainfall, resulting in sewer overflow and flooding episodes. Inadequate management of rainwater runoff exacerbates sewer flooding and pollution, making coordinated rainwater management initiatives necessary. In addition to hydraulic challenges, there are also concerns about the impact of combined sewage on the quality of surface and underground water bodies. The absence of separation between sewage and grey water hinders proper purification, causing excess rainfall to transport pollutants into the sea, rivers, and land. A coordinated rainwater management project is therefore crucial for the effective handling of these issues [2].

In this context, Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs) have emerged as a holistic approach to address water-related challenges while enhancing ecosystem services and community resilience. Particularly, Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) represent a key component of NBSs and are designed to manage urban rainwater by replicating natural drainage processes to mitigate flooding, pollution, and enhance urban amenity and biodiversity. SuDS encompass various interventions, including managed aquifer recharge schemes, rain gardens, green roofs [3], permeable pavements [4], filter drains [5], filter strips, vegetated swales [6], constructed wetlands [7,8], and bioretention systems [9,10].

Several articles have examined infrastructures managing stormwater runoff and offering water-related services [11,12,13,14,15], focusing on climate change mitigation by favouring infiltration and reducing runoff volumes, providing reliable and efficient adaptation measures [16,17], while also providing direct and indirect benefits to the whole community. These multi-objective infrastructures enable the creation of “sponge cities” blending blue, green, and grey elements within urban areas to absorb water and mitigate flood risks [18,19]. International recommendations and water-related policies endorse and support the application of Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) and general NBSs, acknowledging their role in urban water management. This is the case, for example, of the Australia’s water-sensitive cities [20,21], and China’s Sponge City development [22,23,24]. In the European Union, the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) promotes an integrated, basin-based approach to achieve good ecological and chemical status for all water bodies, including the recovery of environmental and resource costs. Within this framework, NBSs can act as multifunctional measures supporting water quality improvement, flood mitigation, and ecosystem restoration. The revised Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive further reinforces the sustainability of wastewater services, emphasizing energy efficiency, resource recovery, and the use of green infrastructure for stormwater management. Together, these directives establish a regulatory foundation that positions stakeholders involved in correct urban water management, such as water utilities, as key actors linking policy objectives with operational implementation through the integration of NBSs into service planning and infrastructure management.

Indeed, traditional strategies, such as sewerage improvements and detention basin construction, while effective as hydraulic solutions, have limitations due to the availability of accessible areas and their financial sustainability. This growing awareness underscores the need to redirect hydraulic defence toward alternative and sustainable approaches.

Specifically, the adoption of SuDS solutions offers several advantages for water utilities, including the reduction in water volumes discharged into the sewer system, thereby enhancing the efficiency of minor purification plants serving mixed sewers. An efficient stormwater management system significantly diminishes the operational costs of traditional networks and, notably, the costs associated with extreme events. Furthermore, it furnishes tools to address a comprehensive spectrum of water conditions, spanning from scarcity to excess water, from drought to floods, including both initial and subsequent rains.

Cases providing evidence regarding the involvement of water utilities in NBS planning and implementation are registered in the US [25,26,27], Canada [28], and in Europe, as in the cases of New Castle [29] and Copenhagen [30,31].

However, few studies have recently examined the preferences and behaviours of officials in water utilities and agencies regarding green and smart infrastructure for stormwater management. Meng et al. (2019) [32] surveyed officials in Pennsylvania, revealing a preference for smart infrastructure and Meng and Hsu (2019) [18], through a US national survey, found that officials are willing to invest in smart technologies for long-term cost reductions. Furlong et al. (2017) [33] explored the water sector’s contribution to greening in Melbourne, emphasizing collaborative efforts with local governments. Piacentini and Rossetto (2020) [10] surveyed Mediterranean regions, indicating limited adoption of water-sensitive practices in Italy, mostly limited to individual local initiatives, and not included in the system’s logic [34].

Building upon this background, this exploratory study seeks to shed light on the understudied role of water utilities in the implementation of NBSs in Italy. In this study, the term “water utilities” is used to indicate “water and wastewater utilities” broadly including organizations responsible for water supply, wastewater treatment, and, in some cases, stormwater management. In Italy, however, these functions are often integrated within multi-utility companies also managing energy and waste services. Accordingly, the analysis focuses on the water and wastewater utilities and water divisions of multi-utilities. The decision to focus the analysis on a single country stems from the distinctive contextual characteristics of water sector governance, which is marked by heterogeneous institutional arrangements across Europe, making cross-country comparisons challenging.

The Italian Context

The Italian water sector operates under a multi-level governance framework that distinguishes responsibilities among several institutions.

Municipalities have traditionally been responsible for urban drainage and rainwater management, but following Law 36/1994 (Legge Galli), responsibilities have been progressively integrated into the integrated water service (IWS). The Legge Galli aimed at consolidating previously fragmented segments into a single, vertically integrated service following the purpose of industrialization of the water sector, driven by the objectives of efficiency, financial self-sufficiency, and full cost recovery through tariffs. The local administration may decide to manage the service using its own means and resources, or it may decide to set up an in-house providing company to whom the service is assigned directly (which is a more frequent choice). In this latter case, however, the company must meet the conditions set by EU legislation. The IWS is organized across sub-regional territorial units—defined as Optimal Territorial Areas (in Italian: Ambito Territoriale Ottimale—ATOs)—established to ensure the efficient and coordinated management of water supply, wastewater, and, in many cases, stormwater. Indeed, while stormwater management—particularly concerning flood control and urban runoff—formally remains under municipal competence, as established by Legislative Decree No. 152/2006 and related local government laws, it is often primarily delegated to publicly owned water utilities or private or mixed companies through public service concessions or public–private partnerships (PPPs) within the boundaries of the ATOs, which coordinate planning and investment at the regional or sub-regional scale. This multi-actor configuration reflects a hybrid model of water governance in which responsibilities for stormwater management remain partially decentralized but increasingly coordinated through the integrated water service. Such institutional complexity is a key determinant for the effective implementation of NBSs in the Italian context [35].

The implementation of NBSs in the Italian water sector involves a broad set of institutions beyond water and wastewater utilities. River Basin District Authorities play a strategic role in planning measures consistent with the Water Framework Directive (WFD) objectives and in integrating NBSs into river basin management plans. Regional and municipal administrations are responsible for land-use and spatial planning, often determining where NBSs can be deployed through urban and territorial plans. Environmental Protection Agencies provide technical support, environmental monitoring, and the evaluation of ecological outcomes. At the national level, the Ministry for the Environment and Energy Security (MASE) defines strategic priorities and allocates funding, often through EU co-financed programmes. In addition, civil protection agencies and park or basin authorities may be involved in flood risk management and ecosystem restoration projects. Within this multi-actor framework, water and wastewater utilities act as operational implementers, translating policy objectives into concrete infrastructure and service innovations.

The Regulatory Authority for Energy, Networks and Environment (ARERA) acts as the national economic regulator, defining tariff structures, performance standards, and quality monitoring mechanisms. Broader environmental and planning functions are shared among River Basin District Authorities, regional administrations, and municipalities, which oversee land-use planning and flood risk management. Environmental Protection Agencies support these processes through environmental monitoring and technical guidelines, while Local Health Authorities provide sanitary oversight.

In Italy, the financing of water services relies primarily on a tariff-based model supplemented by transfer-based mechanisms [36,37]. The Italian tariff-setting methodology for water services, established by ARERA Resolution No.639/2023/R/IDR (MTI-4), defines a cost-recovery framework that includes operational expenditures, capital expenditures, the fund for new investments, and environmental and resource costs. Tariffs are designed to ensure full cost recovery and financial equilibrium for utilities in line with Article 9 of the Water Framework Directive, primarily by remunerating conventional infrastructure assets through depreciation and a regulated rate of return. At the same time, transfer-based funding (e.g., public grants and EU funds) supports major infrastructure investments and innovative measures such as NBSs. In PPP arrangements, private partners may provide upfront financing, but cost recovery is structured contractually and is ultimately reflected in user tariffs. This structure tends to favour the repair and maintenance of existing assets over the adoption of NBSs. Because NBSs often involve distributed, non-conventional, or non-capitalizable investments, their costs are less easily incorporated into tariff calculations and asset registers. See [37] for a schematic representation of the governance and financial flow structure characterizing the Italian water management system.

However, water utilities—often described as “hybrid organizations” due to their public, private, or mixed ownership structures—are designed to deliver public-interest services through a business-oriented approach [38]. A deeper understanding of their potential role in the implementation of NBSs is crucial to assess how they could help mitigate the financing gap resulting from the limitations of public funding in relation to the IWS, thereby supporting a more sustainable transition in urban water management [37].

The paper is organized as follows. Firstly, using the Urban Nature Atlas database (https://una.city), funding sources and stakeholders across Europe are examined. Secondly, semi-structured interviews with officials and experts from water utilities shed light on the Italian context by identifying the challenges and solutions involved in NBS implementation, as well as the role of water utilities. Then, we map cases of water utilities’ involvement in NBSs at the Italian level, highlighting promising practices that could be replicated and adopted more widely.

2. Materials and Methods

Data collection and analysis comprise three main steps, explained in the following. First, to understand the primary funding sources and mechanisms employed for NBS implementation in Europe and Italy, as well as identifying the actors involved, the Urban Nature Atlas database (https://una.city) was analyzed. This database is a comprehensive collection of around 1000 urban NBS cases across Europe. First, we searched for solutions aiming to address water challenges (n = 406) across Europe, analyzing the whole sample. Then, for a more in-depth examination targeted at the country level, we refined our focus exclusively on Italian cases (n = 90)—referring to the following cities and surroundings: Bari, Bologna, Catania, Genoa, Milan, Naples, Palermo, Rome, and Venice - screening the individual cases to identify the involvement of water utilities in the implementation of NBS projects. Descriptive statistical methods were employed to present the results of the database analysis (Section 3.1).

Secondly, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders in the Italian water utility sector and experts in related fields. To ensure the adequate representativeness of the sample, the selection of water utility employees was initially based on company size and economic–financial performance [39], while experts were chosen based on their subject of expertise. This preliminary list was then expanded through snowball sampling and web-based searches. As a result, 18 interviews were conducted—14 with representatives from water utilities and 9 with sectoral experts—totalling 23 respondents (Table S1, Supplementary Materials).

The questions used for guiding the interviews are reported in Appendix A. Although geographic location was not set as a selection criterion, responses were gathered from water utilities operating in Northern and Central Italy, which constituted the context of the study. Interviews were “verbatim” transcribed using Word Online [40]. NVivo 12 software facilitated inductive qualitative coding, allowing for themes to emerge directly from the data, discovering variation, examining complexity, and minimizing the impact of a priori assumptions [41].

In the Results (Section 3.2) respondents were identified as “U#” for utility operators and “E#” for experts. Finally, interview findings were synthesized into an SWOT matrix, a commonly used tool for organizational analysis and strategic planning [42,43,44].

Third, the study addressed the interviewees’ need to map and disseminate best practice examples of NBS development involving Italian water utilities, without claiming to be exhaustive. A methodological approach for mapping was employed, including a brief analysis of the scientific literature via the SCOPUS database, interviews responses, a snowball sampling approach, web searches, and the scrutiny of about 46 databases (Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials provides the list). A comprehensive overview of the projects identified is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S3 and in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials). Moreover, whenever relevant, reference to these projects is made within Results—mainly when dealing with the “drivers” (Section 3.2)—to underline their potentialities.

3. Results

In Section 3.1 we present the results from the analysis of the Urban Nature Atlas database, while in Section 3.2 we present the results of the semi-structured interviews obtained through qualitative coding.

3.1. Results from the Database Analysis

At the European level, the analysis of 406 NBS (selected as “water management” challenge) cases reveals that public budgets are the primary funding sources, dominated by local authorities (35%), followed by national budgets (13%), EU funds (13%), and regional budgets (11%). Corporate investments (10%) and contributions from Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) (5%) also play a substantial role. Results for Italy are consistent with those observed at European level, with local (29%), regional (12%), national (9%), and EU funds (20%) being major contributors. On the contrary, in Italy, major private contributions come primarily from foundations (10%) and NGOs (8%), whereas corporate investments only account for 4%. Financing instruments predominantly consist of earmarked public budgets (about 41–44%) and direct funding or subsidies (about 44%) at both the European and Italian scales, with about 4% coming from donations and the remaining share from other sources (see Figures S2 and S3 in the Supplementary Materials for details). The initiating organizations at both levels are primarily public bodies, particularly local governments/municipalities (Europe: 37% and Italy: 44%). This is followed by private sector/corporates (10%) and researchers/universities (13%), regional governments (7%), and NGOs/civil society (7%) in Europe, while in Italy, regional governments (9%), and NGOs/civil society (12%).

The results concerning stakeholders involved in the implementation of NBSs (Figures S2 and S3 in the Supplementary Materials) are also very similar between Italy and Europe, mainly local government (22–24%) both in Europe and Italy, citizens and community groups (16%), private sector (14%), research and universities (7–10%), and NGOs (7–9%).

The 406 selected NBSs are mainly classified as blue areas (229) and parks and (semi)natural urban green areas (213), followed by grey infrastructure with green features (186) and green areas for water management (170). NBSs have mainly been developed to mitigate the following challenges in addition to water management (406), green space habitat, and biodiversity (374): health and well-being (245) and regeneration, land-use, and urban development (210). In Italy, the 90 case studies are classified as parks and urban forests (semi-natural green areas) (54), grey infrastructure featuring green areas (urban green space connected to grey infrastructure) (26), blue areas (26), and nature on buildings/external building greens of external buildings (13). NBSs are particularly aimed at mitigating the following: water management (24), climate action for adaptation, resilience and mitigation (19), coastal resilience (12), green space, habits, and biodiversity (80), environmental quality (28), regeneration, land-use and urban development (38), social justice, cohesion, and equity (40), health and well-being (46), cultural heritage and cultural diversity (34), economic development and employment (23), and sustainable consumption and production (18).

Upon scrutinizing the 90 Italian cases, it was found that only three cases - in Venice, Genoa and Rome - indicated the participation of multi-utilities; their role is not specified, but none of these were water utilities. Consequently, the analysis of the database revealed no substantive evidence regarding a significant involvement of water utilities in the development or financing of NBSs at the Italian level. This collective examination underscores the critical reliance on public funding, the prevalent role of local governments, and the minimal engagement of utilities, particularly water utilities, in the advancement of NBSs within Italian urban environments.

3.2. Results of Interviews

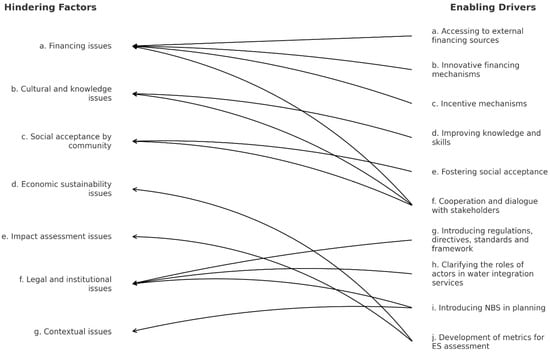

Semi-structured interviews have enabled the identification of factors that hinder the involvement of Italian water utilities in the development of NBSs. At the same time, enabling drivers have been identified to encourage greater involvement from water utilities in this area. The results are presented in the following sections and summarized in Figure 1, where the rows represent the link between enabling drivers and hindering factors. This correspondence is based on an interpretative synthesis of the interview data, through which identified enabling drivers were conceptually associated with the hindering factors they are most likely to mitigate. In the following respondents are identified with code “U#” if they are water utilities operators and “E#” if they are experts.

Figure 1.

Hindering factors and enabling drivers for water utilities in promoting NBSs.

3.2.1. Hindering Factors

Seven hindering factors have been identified as motivating water utilities’ policies on the implementation of urban NBSs.

- Financing issues

Issues related to water tariffs. As explained in the Introduction section, water utilities primarily rely on the water tariff paid by users to fund investments, determined by their strategic plans aligned with intervention priorities. Under the regulated regime, tariff proposals are submitted to the Agency for Local Water Management (in Italian: Ente di Governo d’Ambito—EGA) representing all municipalities insisting in an Optimal Territorial Area for approval, limiting autonomy in financing choices. Tariff-funded projects are legally defined by the ARERA with limited water utility flexibility to include others, as well as yearly possible increases in the water tariff (maximum 8% per year).

Respondents highlight the difficulties in covering priority intervention costs, as they typically focused on existing infrastructures (e.g., by promoting investments to repair/improve pipelines to reduce water losses) rather than NBSs. Small operators face greater difficulty due to limited resources and stagnant tariffs (U12). There are lower water tariffs in Italy, which, compared to other European countries [45,46], limit resources for additional initiatives after covering priority interventions. The Italian average integrated water service tariff amounts to approximately EUR 2.2 per cubic metre, compared to an EU average of around EUR 3.0/m3 (ARERA, 2024; OECD, 2023). This relatively lower level reflects both structural and regulatory factors, notably the partial implementation of the full cost recovery principle under Article 9 of the Water Framework Directive and the heterogeneity of local governance models, which together limit the full internalization of environmental and resource costs. Also, a strong reluctance to request even a modest tariff increase from citizens is registered. Moreover, justifying NBS expenses within tariffs is complex, as existing approaches prioritize conventional “end of pipeline” approaches that do not explicitly encompass NBSs. Although the existing tariff framework is designed to ensure both financial stability and alignment with the Water Framework Directive, it may unintentionally discourage the adoption of NBSs, which require flexible, long-term financing models beyond traditional capital expenditures recognition. Generally, dialogue with regulatory authorities is necessary for NBS inclusion (E19). However, even if these practices are successfully integrated, they often receive minimal economic recognition due to their perceived lower value. Consequently, water utilities are discouraged, as they lack sufficient institutional support and exhibit reluctance to engage in dialogue with authorities out of concern for non-recognition, preferring conventional interventions instead (U6).

Difficulty to access other financial sources. Water utility stakeholders explore public funding sources from regional, national, and European entities for projects, facing challenges in accessing them. For instance, even when public funding is available, it is directed to regions or municipalities that generally do not have the competence to realize this kind of intervention. In such a context, water utilities need to intervene on behalf of a third party (i.e., regional or municipal public authorities) and this, according to respondents, is not effective for a massive-scale promotion of NBS projects.

Capitalization is crucial for transforming assets into tariff-included investments, especially for maintenance and co-financing (U3). Respondents suggest direct funding to ATOs for easier intervention by water utilities and greater flexibility in terms of projects to be funded. On the contrary, when accessing funding calls, the intervention is generally predetermined (U3). This involves primarily political choices, potentially achieved through lobbying (U3).

Contrary to attributing the financial constraint to a scarcity of resources, three interviewees emphasize its “political nature” (E23; U4; U2). Allocation decisions by entities like the Agency for Local Water Management reflect political will, impacting water utilities as managers and not resource owners. Despite EU initiatives like LIFE and HORIZON, challenges exist, including accessing and meeting short-term requirements and tight deadlines for European funding calls. Moreover, these projects often cover only design costs, excluding implementation expenses. Similar concerns were referred to PNRR (National Recovery and Resilience Plan) funds (U3). Limited participation of private actors and banks further complicates funding, exacerbated by a time mismatch between tariff payback periods and debt repayment timelines. Also, assistance is needed for small-scale actors due to limited capacity, despite institutions like the EIB (European Investment Bank) allocating resources for sustainability objectives (U4; E21).

Maintenance costs. The interviewees stressed the increased maintenance requirements of NBSs compared to grey infrastructures, posing challenges in management despite similar implementation costs. Insufficient recognition and addressing of this aspect exacerbate the issue. However, this aspect is not consistently recognized or sufficiently addressed (U3). A lack of resources and skills to sustain long-term maintenance costs, particularly in public bodies, threatens NBSs’ efficacy.

Municipalities struggle with competing priorities, a lack of specialized knowledge, inadequate cooperation, and insufficient funds, leading to project abandonment. As expressed by one respondent, “this aspect is crucial. Today, municipal projects are frequently abandoned due to neglect, stemming from insufficient funds to support ongoing costs, resulting in operational inefficacy” (U2). Some regions consider transferring maintenance responsibilities from municipalities to tariff-operating entities, necessitating tariff increases (U2). A respondent suggested that implementers should also be responsible for managing the NBS during the initial period, thus encouraging greater care in the planning phase, such as avoiding plant selections driven solely by esthetic considerations (U2). Furthermore, it is crucial to consider contextual factors during NBS planning, like urban tree root damage or access challenges in remote or protected areas with specific vehicles (U2). Post-implementation ecosystem services, such as increasing biodiversity and possible new species, need to be valorised and protected (U3). Incorporating investments into the balance sheet is essential for utilities to ensure tariff coverage of operational expenses (U3). Typically, only interventions carried out on assets they own or those under concession within the ATO framework are eligible for inclusion in the tariff. However, implementing NBSs on municipal land poses challenges: purchasing land entails high costs and is rarely pursued, while obtaining concessions from municipalities may transfer maintenance responsibilities to utilities, thereby preventing the recognition of related operational costs in the tariff (E16).

- b.

- Cultural and Knowledge Issues

Lack of internal skills. The respondents emphasized a significant challenge concerning capacity building within water utilities for the development of NBS projects. Generally, smaller operators face a more pronounced “cultural divide” in multidisciplinary skills than larger operators (E23). The lack of NBS projects by water utilities is compounded by the difficulties in finding professionals with the required multidisciplinary and transversal background and skills (encompassing engineering, urban planning, ecology, and natural sciences) (E23; U3). This shortage is also attributed to the current absence of comprehensive courses in Italy, a situation that is expected to improve in the coming years (E18). Furthermore, the challenges of recruiting new colleagues are also exacerbated by the necessity to immerse them in complexities related to innovative technical aspects, administrative responsibilities, and tight deadlines (U12). Water utilities appear to be key drivers in terms of excellent skills in water management and mentioned the growing interest in NBSs. However, this growing interest requires a corresponding growth in knowledge to avoid entry into the business just to earn opportunities or greenwashing (E18). The shortage of qualified personnel remains a structural constraint to innovation and NBS adoption in the Italian water sector. Ongoing initiatives—such as Utilitalia’s Water Academy, ISPRA and SNPA, capacity-building programmes, and PNRR-funded training partnerships—aim to strengthen technical and sustainability competences. Nonetheless, skill gaps persist, particularly among small- and medium-sized utilities with limited financial and training resources.

Path dependency and lack of innovation. The development of innovative NBSs in water utilities face hurdles despite regulatory encouragement, as familiar projects are often favoured over innovative ones (E16). For many respondents, the “engineering” background of project managers in water utilities is identified as a priority issue when compared to financial constraints, with resistance to change being a significant barrier, “money is not the issue. There is enough money there. The issue is the human brain, the human capacity” (E20) (U10).

Overcoming the lack of innovation requires a shift in skills, which is challenging due to entrenched mindsets and resistance by utilities (E20), but also for municipalities that, having a primary role in promoting NBSs, need to think of a new concept of urban planning (U13). Furthermore, some hesitations that are dictated by the results are not always clearly valuable in the planning stage (U3).

Younger employees show more interest in sustainability but face resistance and technical staff often face challenges in managing existing infrastructures, exhibiting limited availability and enthusiasm for overseeing new complex projects (E23). This engineering-centric perspective narrows the focus, overlooking broader considerations related to sustainability, ecosystem services, and potential trade-offs (U4) perpetuating a “path dependency” trend, which hinders the integration of innovative approaches in water utilities (U4). In relation to this a respondent said the following: “I was trained to build a great infrastructure in old style wastewater treatment, and that’s my training. When somebody comes to me and says that what I have been learning 20 years ago is not relevant anymore, it’s very difficult to change your mind and competence. Also, engineers are talking to politicians and politicians want to be able to show that they have built something for the community instead of showing that they have recreated a natural wetland” (E20). The lack of innovation also stems from the nature of utilities as former public companies, lacking competitive market pressure to find innovative solutions (E19) (U3).

- c.

- Social acceptance by community

Cultural barriers have emerged as significant impediments hindering the ecological transition. Communities face knowledge gaps and lack awareness regarding the impacts of NBSs, leading to resistance and often unfounded prejudices (E22; U6; U7; U8). Citizens often express scepticism about the effectiveness of NBSs, considering them a waste of money compared to more conventional approaches (E17). There is a prevailing belief that NBS projects are initiated and subsequently abandoned due to inadequate management, resulting in their ineffectiveness over a short period and fostering reluctance to support potential tariff increases (U11). In addition, citizens express concerns about perceived adverse impacts. Examples include worries about increased mosquito populations in wetlands or bioswales (U3). The “Sponge City” project, incorporating small-scale interventions (i.e., infiltrating vegetation, SuDS, flowerbeds, and a parallel cycle path), faced complaints over perceived reductions in parking spaces, road width, and speed limits, reflecting a NIMBY (not in my backyard) tendency raised by many interviewees. Concerns about permeable pavements in parking lots include fears of vehicle substances percolating into the subsoil, despite advances in vehicle technology and the stormwater treatment provided by permeable surfaces. Finally, several respondents reported instances of “NO” signals displayed on project announcement panels as expressions of disappointment.

- d.

- Economic sustainability issues

The interviewees present varied perspectives on the cost-effectiveness of NBSs compared to traditional grey interventions. Engineers generally perceive NBSs as more expensive, prioritizing financial aspects. A respondent said that “if we had to look only at the economic side, we wouldn’t even make an NBS. I am very transparent, I am an engineer, because the costs of these interventions are much more expensive than a traditional intervention”. However, NBS integration is preferred in environmental enhancement contexts or where landscape constraints exist, such as the mentioned cases of phytopurification near a castle in Brescia and interventions for rural enhancement in Val Canonica (U1; U2).

Trade-offs often arise between environmental and financial priorities. Financially sustainable utilities may prioritize environmental aspects, while the majority prioritize business profitability over environmental considerations, creating a perception of conflicting priorities (U13). Some experts argue against generalizing NBSs as more expensive, citing cases where NBSs have lower maintenance costs compared to traditional solutions and that the cost-effectiveness profile of NBSs vary on a case-by-case basis, considering territorial needs and challenges (E15; E16). For instance, while given the same investment cost, maintenance costs for certain NBSs (e.g., constructed wetlands or urban drainage systems) could be higher than those for grey solutions, in some cases this is not true.

For example, the “Castelluccio da Norcia” project reported lower operational costs for the French Reed Bed compared to conventional methods [7]. NBSs also offer benefits like land redevelopment and simpler maintenance procedures, potentially offsetting initial costs or reducing them in the long run. Maintenance is easier for exposed NBSs compared to buried ones, reducing cleaning frequency. Despite potential savings, cost-effectiveness varies depending on factors like land preparation and ecosystem service provision (E16).

- e.

- Impact assessment issues

Closely related to the previous barrier, a major challenge to NBS adoption concerns the difficulty of measuring and monetising their impacts, which limits the ability to demonstrate their effectiveness and efficiency compared to traditional grey solutions. The inability to integrate these benefits into financial statements limits their attractiveness to investors and discourages utilities from pursuing them. This issue also affects the assessment of ecosystem services, as the absence of standardized accounting methodologies constrains the comprehensive valuation and communication of the benefits of NBSs. Interviews reveal that more in-depth environmental impact assessments are generally conducted only for medium- to large-scale projects, often outsourced to external experts to ensure appropriate environmental and social integration (U14). Specific evaluation methodologies for ecosystem services are rarely employed, with limitations to the assessments required by regulations, such as the calculation of the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) required by the ARERA related to water quality, efficiency, and wastewater treatment. Although stormwater interventions and NBSs can indirectly affect network efficiency, their costs are not systematically tied to KPIs, meaning that performance benchmarking does not directly affect tariff recognition for stormwater infrastructure. This highlights a regulatory gap where revised indicators could better incentivize NBS interventions. Some examples in this sense are some European projects, like LIFE Metro ADAPT, that deploy specialized analysis such as the BEST methodology (U6; U7; U8).

- f.

- Legal and institutional issues

Some interviewees noted that utilities are also subject to a legislative and regulatory risk that can introduce uncertainties and hinder autonomy and operational efficiency, complicating short- and long-term planning strategies, also in relation to NBSs. Bureaucratic slowness and authorisation hurdles create obstacles. An example of such hurdles mentioned by respondents was the problem in the past with hiring specialized profiles for innovative projects due to the need to use the slow public tender procedure for new assumptions. Generally, this reflects a misalignment between public bodies and private needs, impeding speed and flexibility for innovation strategies (U4). Additionally, respondents highlight the lack of regulatory space and political will for NBSs. Finally, changes in municipal administration could also introduce challenges in terms of decision discontinuities.

The fragmentation of stakeholders within integrated water systems poses a significant obstacle, resulting often in unclear responsibilities and overlapping competences, hindering effective collaboration (U11; U12). While national legislation asserts that the management of rainwater falls under the responsibility of local administrations, the practical implementation of this mandate lacks a consistent definition. In certain cases, the managerial responsibility is transferred to water utilities through formal agreements, while in others, municipalities assume that water service utilities naturally handle this activity. This allocation of responsibility significantly influences the interest of water utilities in developing urban NBSs (U3; E16).

- g.

- Contextual Issues

Projects scale. Interviewees highlight challenges in developing urban NBSs due to limited space, high land prices, authorization complexities, and increased maintenance costs. Italian cities’ historical structures further complicate integration, requiring careful urban planning (U13; U14); “The Italian urban structure, as a derivative of the Roman Empire, does not always allow an easy introduction of NBS or at least with simple methods of design, compatible with the times and needs of the city” (i.e., construction sites that do not interrupt the urban flow, etc.) (U13).

Indeed, well-planned NBSs should be aligned with territorial development priorities considering population growth and the evolving needs of the area (E22). While some recognize the potential of peripheral and rural regions due to the availability of space and lower costs (E20), most acknowledge the potential of both urban and peripheral areas (U3; E16; U11; U12). They stress the importance of assessing each NBS type and its objectives without generalizing, to avoid deeming projects unfeasible from the beginning (E16). However, the potential role of water utilities in urban areas will increase if these entities gain more competence in the management of urban rainwater, aligning their responsibilities with integrated services (E15). Finally, the financial dimension is also impacted by the limited size or excessive fragmentation of projects, restricting the development of robust financial instruments and hindering access to funding from institutions, which often require substantial financial commitments (U4).

Timing of the impacts. Another issue mentioned by the respondents is the timing of the impacts, since, generally, NBSs require long-term implementation to produce benefits (E20). This means that the need to intervene in an emergency or quickly, favouring post-intervention actions over preventive measures, results in a preference for interventions capable of delivering immediate impacts. Moreover, the long-term benefits also create a mismatch in the case of debt repayment, as previously mentioned, with respect to access to external sources of funding.

Size and geographical location of the water utilities. The size of water utility operators emerges as a determinant factor in the implementation and efficient management of NBSs. Larger entities exhibit greater investment capacity, the ability to attract skilled professionals, and greater research capabilities, all contributing to more effective NBS implementation (U9). Interviewees also emphasize regional disparities, particularly between the North and South of Italy, in terms of resource distribution, skill levels, spending capacity, and priorities. Southern regions, particularly, face historically recognized [23] challenges related to greater sector fragmentation and insufficient planning, focussing on emergency-level interventions over advanced long-term strategies, including NBSs (E21; U9). These difficulties are further reflected in the limited access to financial resources (E21). In this context, according to certain respondents, the privatization of water services was deemed an ineffective strategy (E21).

3.2.2. Enabling Drivers

Nine different categories of drivers have been found to motivate the policies of water utilities in implementing urban NBSs.

- Access to external financing sources

Regarding the possibility of involving other financial sources, a couple of smaller operators express difficulties in perceiving current interest from entities other than municipalities: “I find it hard to think, at least for our interventions, that a municipality or, in any case, a public body that is not directly involved could finance it, certainly not a private individual, if not for aspects related to sustainability or which could constitute an appeal” (U1). Conversely, most interviewees see potential for the creation of collaboration and synergies by leveraging financial resources and involving stakeholders who stand to benefit from NBS projects. There is a particular focus on potential partnerships with investment funds and real estate, emphasizing the increase in property value near NBS sites (U2).

Corporations are seen as having a significant future role in NBS projects (U13), driven by interests in biomonitoring, minimizing impacts, and addressing climate-related risks that can affect their operational zones and business, such as flooding, while staying in compliance with regulations (U11). Successful dialogues between managers, production companies, and business associations have been observed, for example, in the “working tables” organized in the APUA project (U11), leading to collaborative solutions for local territories, where NBS projects developed in partnership with water utilities can find a place.

For instance, tools like the Business Improvement District can generate synergies for the redevelopment of business areas, in collaboration with or relying on water utilities as a technical partner (E23). Additionally, some utilities have contractual agreements with corporations to develop projects aiming to offset emissions through NBSs as part of neutrality plans. Moreover, regional funds for urban regeneration are accessible. An illustrative instance is the tender initiated by the Regional Agency for Agricultural and Forestry Services (ERSAF) in the Lombardy Region, facilitating collaboration between municipalities and utilities in urban regeneration endeavours, thereby enabling the recovery of costs linked with retrofitting interventions on car parks (U11; U12).

In addition to providing financial assistance, the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) funds present opportunities, also addressing various constraints, including bureaucratic, technical, administrative, and primarily, political hurdles. These resources have facilitated the development of projects such as the “Sponge City” initiative in the Metropolitan City of Milan, with significant involvement from CAP Holding and MM Spa (see Table S3 in Supplementary Materials for more details).

However, the dynamics, time constraints, eligibility criteria, and terms mentioned above must be considered when applying for grants (U11; U12). Furthermore, regarding the engagement of financial institutions, respondents stress the necessity for tailored credit lines dedicated to water management, considering sector-specific characteristics and temporal mismatches between investment payback periods and the timeframes requested by banks (U11; U12; E17).

Interest from national and European banking institutions in the water sector has grown significantly between 2018 and 2021, leading to the development of tailored financing models. An example is the EIB Italian Small Water Utilities Programme Loan, which provides financing to unlisted industrial operators, granting loans to medium-sized water service providers (E19; E21) [36]. Moreover, European funding programmes play a crucial role (i.e., LIFE, Horizon Europe, PRISMA, and INTERREG calls) (E23; U3). In addition, structural and cohesion funds—often co-financed through national programmes—represent a major source of investment for stormwater and climate adaptation infrastructure, particularly within the framework of regional operational programmes (PORs) and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR). The development of NBSs can further expand the range of funding opportunities available to utilities. Since NBSs deliver multiple benefits extending beyond water management—such as biodiversity enhancement—utilities may access a wider set of dedicated funding schemes (U3; U11).

Also, PPPs are highlighted as effective models for matching public and private resources, facilitating complex projects (E17). Private resources can also be mobilized through crowdfunding, sponsorship, and payment for ecosystem services, (see, for example, the case of LIFE Brenta 2030 in Table S3) as well as through the establishment of facilities or funds (U7). The project “Bioclima” serves as an example of a successful PPP (Table S3). Water utilities can allocate their own resources, often through corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, to mitigate negative impacts of operations and demonstrate commitment to environmental and social protection. Hybrid interventions, such as planting to absorb pollution near incinerators, are documented in Sustainability Reports (U6).

- b.

- Innovative financing mechanisms

Water utilities have the potential to influence the development of the sustainable financial market due to their inherent commitment to essential services for sustainable development, benefiting from instruments like green bonds and sustainability bonds [47]. These attract a growing number of diverse investors, including pension funds, infrastructure funds, standard asset management funds, and debt funds and offer advantages like subsidized rates and the achievement of predefined sustainability indicators, thereby ensuring transparency. However, small operators face challenges due to financial constraints and high transaction costs (E21).

To address these challenges, potential alternatives for small- and medium-sized industrial companies include financial pooling, the aggregation of network contracts, or the establishment of ad hoc corporate vehicles that can be secured and placed in financial market capital (U4; E21). Models like “trait enhancement” and “Collaboration Agreement” enable responsibility and risk sharing. A winning example in this sense is the Viveracqua consortium succeeding in issuing hydrobonds and pooling resources from 14 operators in the Veneto region for innovative projects. Other major operators have also had experience with issuing green bonds, including Hera and Iren. However, the challenge lies in adapting these instruments to include NBS interventions. Furthermore, integrating NBSs into water tariffs is seen as a viable strategy by respondents for the potential development of NBSs by water utilities (U3), exemplified by initiatives like the LIFE Brenta 2030 project, aiming to finance NBSs through the water tariff, aligning with regulations and leveraging customer resources for NBS development.

- c.

- Incentive mechanisms

At the regulatory level, providing incentives for managers to prioritize the development of NBS projects over traditional ones could significantly accelerate the advancement of these solutions. Offering incentives to municipalities is also considered beneficial, allowing water utilities to assist them with technical interventions. The legislative framework for new constructions presents an opportunity for incentives or tax breaks, encouraging citizen involvement (E18). Incorporating NBSs into urban planning is highlighted as essential for their effective valorisation. Another noteworthy aspect, acknowledged by some interviewees, involves incentivizing Responsible Project Managers (RUPs) within consulting firms and managing bodies to prioritize NBS projects. The existing bonus structure, often tied to yearly project completion numbers, may discourage the pursuit of complex or innovative projects. Introducing additional rewards or incentives for managers engaged in multi-objective projects offers a pathway to promote NBS adoption, actively involving water utilities in the process (E16; E18).

- d.

- Improving knowledge and skills

Addressing the “cultural divide” and skill gaps that impede the testing and implementation of NBSs involves disseminating knowledge through university and professional courses. Creating multidisciplinary teams is suggested to develop successful multi-objective projects since multi-skilled profiles are often challenging to find. However, effective management is crucial to facilitate discussions and reach agreements between experts (E16). In this sense, collaborations are highly effective, to develop knowledge and “standard” case studies to replicate (E16). Collaborations and the sharing of good practices play an essential role in disseminating expertise from academia to practitioners, as, for example, the already mentioned initiatives promoted by Utilitalia, ISPRA and SNPA. The exchange of skills and successful pilot projects among utilities, fostering a network and collaborative approach, promote positive competition and a “nudge” for improvements and the testing of more innovative projects, including participation in European projects (E19; E23; U3). Successful interventions demonstrating the potential of NBSs can influence political will, build confidence among the public sector and financiers, and overcome barriers to innovation.

- e.

- Fostering social acceptance

Respondents often note citizens’ limited awareness of NBSs despite growing sustainability concerns. Most water utilities already promote education programmes to highlight NBS benefits targeting citizens and students (E15). However, additional efforts are necessary, calling for systematic national campaigns (E17). Presenting NBSs as tangible technological systems, emphasizing their protection against vandalism and pollution, proves crucial for efficacy (U11; U12). Achieving citizen acceptance involves transparently presenting the project’s objectives, using explanatory panels, and providing data-supported impact assessments (U10). Effective communication, facilitated by Communication Offices, demands accessible language comprehensible to all (U11, U12).

Participatory mechanisms like stakeholder participation facilitate discussions. For example, initiatives like “water living laboratories”—territorial structures based on the concept of partnership, involving research, innovation, business, public administration, and environmental aspects—encourage inclusive decision-making and bottom-up approaches aligning solutions with territorial needs for social acceptance (U10; E22).

However, fostering public acceptance requires cultural and behavioural shifts, which may affect everyday practices such as parking habits, speed limits, and travel comfort (U11; U12). Consumer choices—by shaping political and business decisions—assign individuals a central role in driving societal leadership and transformational change (E22).

- f.

- Cooperation and dialogue with stakeholders

Sustaining dialogue with stakeholders in the integrated water cycle, including regulatory bodies, area authorities, institutions, and municipalities, is essential for the upscaling of NBS projects (U9). Collaborative efforts, especially with municipal support, can initiate pilot initiatives or develop more complex projects, although smaller entities face authority limitations. Partnerships and structured agreements minimize conflicts, combining experiences and resources. Encouraging research, internally and with the scientific community, ensures science-based targets and scalability evaluations.

For example, a respondent indicated that, through collaboration with reclamation consortia, a project initially focused solely on planting interventions was expanded to integrate wetlands (U10). Furthermore, partnerships and structured collaboration agreements can minimize possible conflicts in technical, legal, and economic aspects, combining experiences and resources for successful results (U9; U12).

Given the innovative nature of these solutions, encouraging research is fundamental, both internally and by developing partnerships with the scientific community, universities, and research centres to test experimental projects, facilitate a science-based target, and evaluate their potential for scalability and replication (U1). Collaborating with nearby universities seems preferred by respondents, ensuring contextual knowledge crucial for project success. This synergic approach results in economic resources, experience, and growth through participation in multidisciplinary projects (U1).

Also, networking among companies, sharing good practices and experiences are frequently emphasized (E15). Furthermore, once the monetary and community value of an NBS is recognized, exploring partnerships across unconventional sectors becomes feasible. For example, before COVID-19, some discussions emerged regarding possible public–private partnerships for energy and water efficiency interventions in buildings. This possibility was emerging, with a first decree of subsidized financing, but changing spending priorities post-COVID-19 have negatively impacted the trajectory of these discussions (E15).

- g.

- Introducing regulations, directives, standards, and frameworks

Water utilities, as service managers, are significantly influenced by political directives in advancing NBS. While current resource allocations prioritize traditional issues, political measures such as “command and control” are identified as crucial drivers for NBS adoption (E20). Water protection plans and regional regulatory bodies play crucial roles, but interviewees advocate for a more forward-thinking approach at both the Agency for Local Water Management and ARERA levels.

While the ARERA currently operates as an economic regulator (Law No. 481/1995), it also holds the authority to integrate environmental objectives into tariff methodologies, as well as promoting efficiency indicators related to specific environmental dimensions, consistently with national and EU legislation. Interviewees suggest that the ARERA could further strengthen its role in promoting sustainability by explicitly incorporating references to NBSs within its resolutions, for instance by clarifying how standard NBS-related investments can be recognized within tariff calculations. This would remove ambiguity for local authorities and utilities, encouraging them to consider non-traditional interventions. On the other side, according to some respondents, the lack of clarity also provides more flexibility for local bodies to explore NBSs without preclusion (E15) (E19).

Finally, while the ARERA operates under the principle of technological neutrality and therefore cannot directly incentivize specific solutions—even when they are more sustainable—without a higher-level policy mandate, its recent efforts to broaden the scope of environmental and resource costs within tariff methodologies already act as an indirect yet significant driver for the adoption of NBSs. Also, with the last resolution related to tariff method, the ARERA introduced the M0 indicator on water resilience (Resolution 637/2023/R/idr). This new metric provides an opportunity to recognize NBSs as potential measures to enhance system resilience and climate adaptation within the Italian water sector. By progressively acknowledging expenditures and indicators related to ecosystem services and environmental protection, the ARERA’s regulatory framework contributes to creating more favourable conditions for integrating NBSs into water management strategies (E19).

Additionally, the European Taxonomy of investments directs financial resources toward sustainability projects, including NBSs [48], aligning with regional and European regulations’ facilitation of NBSs. “The role of the Taxonomy is central, because all these financial solutions would converge towards the schemes of the Taxonomy. If the entire financial world is equipped to evaluate projects according to taxonomic rules, when you are within those rules, you also see your financial support guaranteed” (U4). The Taxonomy’s standardized approach to project evaluation is expected to guarantee financial support within its rules (U4). Nonetheless, regulations must strike a balance, as strict interpretations often stemming from inaccurate translations of Anglo-Saxon terms of the European directive, may hinder the adoption of sustainable alternatives, exemplified by the rejection of valuable circular solutions due to stringent interpretations of European guidelines on the DNSH (Do Not Significant Harm) principle (U11; E19; U12).

- h.

- Clarifying the roles of different actors in water integration services

Legislation should address the lack of clarity in roles and skills within the water cycle. Some managers suggest assigning greater responsibilities, such as rainwater management, to utilities through formal agreements. Water utilities possess valuable knowledge and expertise within their operating territories and can often handle these solutions more efficiently and expediently compared to municipalities, which often face resource and personnel constraints. “Our experience with the region is that there are two regional reference departments, there is the municipality, there are us, there are the consortiums. Therefore, from this point of view, a request for simplification in operational terms would be optimal” remarked a manager (U5).

This shift in responsibilities from municipalities to water utilities is actively pursued in regions like Lombardy, where managers express interest in assuming these services (U1; U2).

- i.

- Introducing NBSs in planning

To overcome the context and scale challenges associated with the adoption of NBSs, they should be introduced broadly from the project’s origin, encompassing aspects related to building characteristics, as well as general structure and components, not limited to spot interventions. Adopting a holistic and globally integrated approach to urban planning is essential for reimagining cities in a more harmonious and sustainable manner.

Furthermore, many small-scale NBS interventions can be quite easily integrated into urban environments, such as, for example, along the edges of streets, where the focus is not on creating new space but on redesigning existing space more sustainably. For example, in Lombardy, significant market growth was observed following regulatory reforms related to rainwater management. A similar trend occurred with phytopurification systems, which gained momentum following their inclusion in the Water Law in 1999, expanding from around 10 units in the 1990s to approximately 8000 units currently (E16).

- j.

- Development of metrics for ES assessment

Interviewees underscore the relevance of developing accessible and standardized methodologies and metrics to evaluate and quantify the ecosystem services provided by NBSs. This necessity is deemed critical across all sectors involved in NBS development. Standardized metrics facilitate effective communication, enhancing the credibility of NBSs among stakeholders and expediting their integration into intervention planning with local authorities. Moreover, these metrics serve as essential tools in securing financial support for NBS initiatives, enabling the demonstration of how NBS are inherently more sustainable, resilient, and efficient when compared to traditional “grey” solutions (E15).

4. Discussion

The results of the analysis highlight the current and potential role of water utilities in developing NBSs in Italy. Examination of aggregated data from the Naturvation database indicates that water utilities have not been involved in developing NBSs in Italy, with public bodies acting as the main organization and source of funding. However, after a more comprehensive analysis encompassing different databases, we have identified relevant Italian case studies (Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials). Furthermore, the interviews have shed light on the underlying factors influencing this trend in Italy. Some of these are specific to the water utilities sector, while others can be considered “transversal”, impacting multiple stakeholder classes involved in NBS development.

In Table 1, an SWOT matrix was developed as a synthesis of qualitative evidence emerging from semi-structured interviews through an interpretative thematic approach. The recurrent themes identified were interpreted according to their internal (organizational aspects) or external nature (contextual factors) and positive or constraining influence on NBS implementation, being classified as Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, or Threats. This pragmatic approach translated qualitative insights into a structured analytical framework, consistent with the exploratory aim of the study, providing us a clearer picture of the internal and external pressures and opportunities for the water utilities sector in implementing NBSs. This summary overview helps to identify potential problem areas and encourage policy developments [43].

Table 1.

SWOT matrix.

Historically, Italy embraced stormwater collection until the 19th century, yet there is still a lack of integration of adaptive stormwater management systems and the adoption of Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) in policy and practice [15]. Despite this, respondents, particularly from larger utilities, express interest in exploring sustainability-aligned solutions, including NBSs. However, utilities encounter challenges such as limited decision-making autonomy, engineering-centric approaches favouring traditional systems, and inadequate internal skills for NBSs’ multifunctionality. Confusion persists regarding the definitions and categorization of NBSs. Additionally, some projects involving structural interventions at the source, such as those aimed at controlling water losses or depuration, which do not always involve the use of natural elements but are aimed at efficiency improvements also in terms of sustainability—are incorrectly reported as NBSs. Another contributing factor is the tendency of professionals to use specific and technical terminology for interventions, often failing to recognize them under the broader term of “NBS” since this concept emerged relatively recently in 2015 [49]. The literature extensively documents the prevalent confusion regarding the precise definition of NBSs [50], further compounded by the absence of widespread standards and metrics [51]. Fostering social participation through information sharing and a participatory approach can promote community acceptance and minimize critics [15].

Additionally, stakeholder fragmentation within water management and administrative ambiguities resulting in unclear competencies and responsibilities, hinder effective decision-making and regulatory integration of rainwater management [10,37]. The site-specific nature of NBSs and urban space constraints necessitate comprehensive urban planning revisions and cultural shifts toward NBS integration. A cultural shift is imperative, both formally through regulatory measures and informally through changes in culture and discourse, as confirmed by [25]. Supportive policies, financial incentives, and European funds are considered essential for fostering NBS implementation by water utilities, as highlighted by Piacentini and Rossetto (2020) [10], with the ARERA playing a pivotal regulatory role. Additionally, leveraging resources from citizens through water tariffs, along with innovative financing mechanisms from financial institutions offering dedicated credit lines, is paramount, especially given the growing interest in sustainable markets. Strategic integration of NBSs throughout the water cycle supports specific objectives and solutions, underscoring the importance of interventions at the regulatory, community, and national levels.

European Regulation 2020/852, which outlines a framework for sustainable investments, underscores that water service is not merely a component of the “Green Deal” but constitutes its fundamental cornerstone, advocating for integrated policies ensuring soil conservation, water quality protection, and quantitative management. Water utilities should adopt an integrated and multiscale policy aimed at guaranteeing soil conservation, qualitative protection, and quantitative management of water, aligned with multi-objective principles that yield benefits across multiple levels. Some utilities in Italy have already demonstrated a strong sensitivity to this issue and have initiated pilot NBS projects. However, such cases remain limited, largely due to the absence of systematic planning.

Considering our focus on a sector rather than a specific organization, proposing development strategies based solely on the SWOT analysis would pose challenges and may be ineffective. Instead, by utilizing insights gleaned from the SWOT matrix regarding potentialities and internal and external pressures and acknowledging the role of water utilities as management entities, we have delineated five proactive roles that water utilities can adopt to promote the advancement of NBSs, as detailed below. In addressing our research question, we stress that the role of water utilities transcends merely providing funding; rather, it encompasses a broader spectrum of functions. These roles represent broad categories whose applicability largely depends on each utility’s financial capacity, organizational side, internal expertise, and external context. They are not mutually exclusive, as utilities may simultaneously perform multiple roles, creating potential synergies across functions.

For each identified role discussed subsequently, we highlight the strengths and opportunities to capitalize on (S and O) as well as the obstacles and threats to address (W and T). A visual representation is provided in Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

Role 1: Experts (Exploiting: S1, S2, S3, and S4; targeting: W1 and T2)

Water utilities possess technical expertise in water management and treatment (S1), coupled with agility in adapting to market demands (S3), a trait lacking in public entities (T2). Although there is a skills gap in NBS-specific areas, training can address this gap, enabling utilities to swiftly adapt to new technologies or trends (W1).

Their knowledge of local territories needs and priorities allows them to develop tailored intervention solutions, maximizing community benefits effectively. They serve as standard-bearers and pioneers in developing impactful strategies for community development (S2). As said by a respondent: “since we provide a service for citizens, it also means trying to develop new solutions that are effective and also bring advantages to local stakeholders. We are very rooted in the territory and for the territory, so it becomes truly essential to be standard-bearers, spokespersons, even pioneers in so-called design areas, perhaps not yet consolidated and fully developed” (U13). Additionally, water utilities excel in monitoring NBS project performance over time, minimizing maintenance issues. By collecting data on water quality, biodiversity, and community resilience, they can assess the solution’s effectiveness and enhance future projects (S4).

Role 2: Innovators (Exploiting: S3, O2, O3, O5, and O7; targeting: W4, T4, and T6)

Water utilities can take a relevant role in promoting innovative projects (S3), also developing partnerships with universities, research centres, and other experts who can integrate their expertise for the testing and development of pioneering and innovative projects (O2). Compared to public administrations, water utilities have a greater drive for innovation (U10). Starting from their base of skills and infrastructure, they can start to integrate natural elements into existing infrastructures and solutions, testing mixed green–grey solutions to facilitate the transition to more sustainable interventions. This may include, for instance, incorporating green roofs, permeable pavements, or constructed wetlands into stormwater management systems, enhancing the overall efficiency of water utilities’ operations. By establishing pilot projects and demonstration sites, water utilities can showcase the effectiveness of NBSs to the community and other stakeholders (T4 and T6), as well as potential funders and donors (W4, O3, and O5). These projects serve as practical examples and may inspire similar initiatives (O7).

Role 3: Knowledge sharing (Exploiting: O7; targeting: W1, W2, W3, T4, and T6)

Water utilities can provide training and capacity-building programmes for their staff, as well as for local contractors and community members (W1, W2, and W3). Building local expertise in designing, implementing, and maintaining NBSs ensures the sustainability of these solutions. Their role in knowledge sharing is not limited to industry professionals; water utilities can and should also serve as advocates for significant community education and awareness campaigns aimed at citizens and educational institutions (T4). Through educational programmes, workshops, and community engagement initiatives, they can inform residents about the benefits of green infrastructure, conservation practices, and sustainable water management. Many utilities are already involved in these efforts. Furthermore, they can advocate for the dissemination and sharing of best practices (through platforms and articles, etc.) and collaborate with other operators and organizations (not limited to public entities) to develop integrated projects within the community (O7). These initiatives aim to maximize benefits for the community and have the potential for scalability and replication, thus contributing significantly to closing the knowledge gap regarding NBSs (T6).

Role 4: Funder (Exploiting: O2, O3, O5, and O6; targeting: W4 and W5)

Water utilities play a crucial role in supporting NBSs by allocating funds to green infrastructure projects, enhancing water management systems’ resilience and sustainability. Collaborative networks enable them to develop alternative financial instruments, such as hydrobonds, to address challenges related to fragmented stakeholders and urban-scale interventions (O2, W4, and W5). Also, water utilities can promote or participate in innovative financing mechanisms, such as payment for ecosystem services, which can allow for mutual learning between stakeholder groups with different perspectives [52], payment for watershed services [53], and payment for success instruments such as environmental impact bonds [54] (O3, O5, and O6).

Incorporating NBS costs into water tariffs, regulated by the ARERA, represents a viable approach, as demonstrated by the LIFE Brenta 2030 project in Italy. Internationally, Peru has emerged as a leader in progressive NBS policy for water management [25]. Furthermore, water utilities can act as competent partners within partnerships to apply for European projects and national and regional tenders, and therefore access sources that they would traditionally not be able to easily access. Projects integrating various aspects such as biodiversity, climate adaptation, and mitigation, are increasingly attracting European funding. Some examples include LIFE REWAT, Trigea EAU, LIFE Brenta, and Interreg Alpine Space and are reported in Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials (O2 and O4). Investments in NBSs can enhance utilities’ reputation and social acceptance, especially when coupled with awareness campaigns. Moreover, given the significant influence of the public sector on utilities, preference for NBSs over alternative solutions could manifest through green procurement policies (W4). Finally, while NBSs could, in principle, be framed within the urban infrastructure domain that traditionally falls within public investments, rapid urbanization and a lack of public funding for urban NBSs may render the involvement of private investors attractive, and sometimes even necessary.

Role 5: Partner (Exploiting O1, O2, O3, and O7; targeting: T1 and T3)

Water utilities can collaborate with local communities, environmental organizations, government agencies, and businesses to jointly develop and implement NBS projects. Collaboration fosters knowledge exchange, leverages resources, and ensures the success of NBS initiatives. Additionally, collaboration with the agriculture sector is becoming increasingly important, for example, for the reuse of water for agricultural irrigation [55] like in the “Req pro” project (see Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials) (O2).

Water utilities can advocate for policies that support the implementation of NBSs. They can collaborate with policymakers (also through actively participating in organizations such as Utilitalia) to create regulations and incentives that encourage the adoption of green infrastructure and nature-based approaches in urban planning and development. Networking opportunities enhance their ability to effectively convey their needs and proposals, fostering dialogues and discussions with diverse stakeholders, thus mitigating the fragmentation associated with integrated water services (T1). By positioning themselves as promoters of these solutions and fostering active dialogue with regulatory bodies like the Agency for Local Water Management and ARERA, water utilities can exert influence over pertinent political decisions (O7, O1, O3, and T3).

5. Conclusions

The study examined the role of water utilities in the implementation of NBSs for water management in Italy. Regarding the financing sources and instruments used for NBS implementation, our analysis of the Urban Nature Atlas database revealed that, despite water utilities’ current limited engagement in developing urban and peri-urban NBSs in Italy, there is a positive trend towards recognizing the value of these solutions.

Semi-structured interviews with Italian industry professionals and experts in the field revealed the obstacles and motivations that influence water utilities’ engagement in NBS development. Although current interest appears sporadic and lacks a systematic approach, there is an interest and potential for water utilities to play an active role, particularly among managers responsible for rainwater investments in urban areas. NBSs offer advantages over traditional interventions for water utilities and communities, yet financial constraints, limited autonomy in investment decisions, and cultural barriers impede their widespread adoption.