Abstract

Our research aims to provide a comparative analysis of water governance components by presenting the complexity of water-covered land use by the extractive industry in terms of legal, economic, and environmental protection aspects in Poland and Malaysia, along with the corresponding regulations and their implications. This paper discusses the legal forms of land ownership and use, as well as the currently applied principles for calculating fees for using state-owned water covered land that contains mineral deposits. We also present a comparison of selected technologies for the extraction of sand and gravel aggregates under water with their environmental impact. This research highlights the need for specialized valuation frameworks tailored to the geological and regulatory landscape of Poland and Malaysia. We suggest that the market value of land located above a mineral deposit, calculated individually for each deposit-property, should serve as the basis for calculating the lease fee. This discussion should encompass not only the principles and methodology involved in estimating the magnitudes of lease rents on mining industry and its profitability, but also the identification and criteria for assessing the risks associated with ongoing or planned mining ventures and concerns about the protection of river ecosystems. Our research contributes in providing data to stakeholders on extractive industry that operates within flowing and standing inland waters. The key finding of our research is that, in our opinion, the water governance frameworks in Poland and Malaysia are inadequate for protecting public finances and for internalizing the environmental externalities inherent in the economics of mining.

1. Introduction

Effective water governance is widely recognized as essential for managing resources amid competing uses and climate change, leading to diverse governance regimes globally. The study by [] addresses the identified gap in the comprehensive synthesis of comparative studies by providing a systematic review of research that critically analyzes how governance is defined, conceptualized, and assessed across various contexts. It concludes by identifying four key areas for future research, including the need for longitudinal studies, an expanded focus on the global South, and greater attention to justice, equity, and power. As for data gathering and screening, the authors analyzed various publications written in English that contain a comparison of at least two empirical cases across geographical space. These publications focus on the governance of water resources and services, as well as other relevant topics, such as aspects of environmental protection. Our research aims to provide a further analysis of water governance by presenting the complexity of water-covered land use by the extractive industry in terms of legal, economic, and environmental protection aspects in Poland and Malaysia, along with the corresponding regulations. In this paper, we discuss the legal forms of land ownership and use, as well as the currently applied principles for calculating fees for the use of state-owned, water-covered land that contains mineral deposits. The study also analyzes the legal and regulatory mechanisms for determining lease rates within the context of the economic conditions under which mining enterprises operate.

Research performed by [] provides a nuanced picture of water governance in Asia; however, among the 17 countries, Malaysia was not mentioned. The study indicates that high-income countries tend to have stronger legal systems, whereas decentralized water governance is found in lower-income countries, which is also consistent with the literature.

The extractive industry has impacts on the environment at many levels, depending on the type of commodity (like raw materials or oil and gas) and type of extraction: underground, open-pit, underwater, borehole extraction. For this research, in contrast to deep-sea mining research [], we focus on underwater extraction in connection with flowing and standing inland waters. For this type of extraction, sand and gravel mineral deposits are considered. The total annual production of sand, gravel and crushed stones in Poland is closely correlated with the economy and current demand, particularly for construction work []. Different occurrences of mineral deposits require appropriate exploitation techniques. It is estimated that approximately 75% of gravel and sand is extracted from under water in Poland, with a growing tendency. This includes more than 50% extracted using suction dredgers, which also allow the recovery of fine fractions. Suction dredgers are utilized in mines with a higher extraction volume, typically exceeding 100,000 Mg (tonnes) per year. Small plants with an output of up to 20,000 are predominant in terms of quantity, accounting for over 75% of the number of exploited gravel and sand mines in Poland. From these, over 17% of domestic extraction is obtained. They employ technologies for dry or underwater extraction, using land-based exploitation methods and relying mainly on single-bucket excavators (buckets, grabs, scrapers) or rope scrapers, among others. The onshore (inland) dry extraction, which accounts for approximately 25% of extraction in larger mines, is equipped with processing and flushing installations that enable the recovery of fine sand []. In study [] authors present the division of exploitation technologies for sand and gravel aggregates, with particular attention to underwater mining, which has increased its share by more than 20% over the past 40 years. The research paper also presents a comparison of selected technologies for the extraction of aggregates underwater. For the analysis, data from Polish and German mines were used. Using a sample deposit as the basis, an analysis of the costs of sand and gravel aggregate extraction was presented, where a dragline scraper and suction dredger were used, and then a comparison of production and unit operating costs for four types of deposits and eight extraction methods (two for each type of deposit) was performed. The results obtained should be useful for the evaluation and selection of appropriate production technologies for sand and gravel aggregates exploited underwater.

1.1. Environmental Concerns and Water Protection in Poland

The Water Law Act [] in Article 50 states that water, as an integral part of the environment and a habitat for organisms, shall be subject to protection regardless of its ownership. As presented, the use of equipment and invasive methods can not only cause physical harm, but can also generate other impacts, such as noise, which was the subject of research []. In research [], a multi-decadal study of the Przemsza River in southern Poland shows that industrial activities, primarily coal mining, have led to a significant increase in surface water salinity. Paradoxically, despite a reduction in the amount of mine water discharged since 1991, the river’s salinity has drastically worsened due to more concentrated brine from deeper mines and historically low river flows caused by drought. The importance of sand as a resource was stressed in the World Economic Forum []; to make sand resource management “just, sustainable, and responsible”, the United Nations Environment Program says sand must be formalized as a “strategic resource at all levels of government and society”, while ecosystems degraded by sand mining activities must be restored.

1.2. Land Ownership in Poland

In Poland, property law is governed by the Civil Code []. The management of property owned by the state or communes is also regulated by the Property Management Act []. According to the Civil Code, ‘Real Estate’ is a part of the earth’s surface constituting a separate object of ownership (land), as well as buildings permanently attached to the land or parts of such buildings if, under specific regulations, they constitute an object of ownership separate from the land. When referring to Real Estate, we also usually mean its component parts. A component part of a thing cannot be a separate object of ownership or other real rights; moreover, a component part of a thing is anything which cannot be separated therefrom without damaging or substantially altering the entire thing or without damaging or substantially altering the separated object. Objects attached only for temporary use do not constitute a component part of that thing. Except as specified by law, buildings, facilities fixed to the land, and vegetation like trees and plants are regarded as components of the land once planted or sown. Real estate ownership rights are also considered part of the real estate.

Premises can be subject to different ownership than the owners of the land only if specific regulations authorize separate ownership rights (e.g., condominium rights and the ownership of a building erected on land where the right of perpetual usufruct has been established). As a consequence, if the law does not provide otherwise, all structures erected on the land (e.g., a building) are always owned by the owner of the land and cannot be a separate object of ownership (Latin: superficies solo credit) []. Generally, a real property interest is held by one of the following means: Ownership, Perpetual usufruct, Condominium rights.

As it is referred to in Poland, ownership is a title to real property equivalent to the ‘freehold title’ in the English system. Ownership grants the freedom of use and encompasses the collection of benefits, as well as the right to transfer for an unlimited period. The right of perpetual usufruct is a title to real property owned by the state or a commune. This right can be established for a specified term of 99 years. In exceptional cases, such a period may be shorter, but not less than 40 years. The term of perpetual usufruct may be renewed. Perpetual usufruct is a transferable, alienable, and mortgageable right of use. Natural persons and legal entities can be granted the right of perpetual usufruct to land owned by the state or a commune. Under Polish law, perpetual usufruct ranks second in the hierarchy of interests in real property.

1.3. Ownership of Land Covered by Water in Poland

Land covered by water in Poland presents a somewhat different kind of asset compared to others. In Poland, issues of water and land ownership are regulated by the Water Law Act. The waters can be owned by the State Treasury, other legal entities, or natural persons. The law also regulates the principles of managing these assets as part of State property. The provisions of the Act apply to inland and sea waters within Polish jurisdiction. Inland surface waters, according to legal provisions, are divided into flowing inland waters (rivers) and standing inland waters (lakes). According to Article 211 of the Water Act, territorial sea waters, inland sea waters, flowing inland waters, and groundwater are the property of the State. Inland flowing waters that are classified as public waters are not subject to free-market transactions, except in very limited cases specified in the Act. As a result, while appraising such a property, a valuer encounters the difficulty that if a particular property is not involved in market turnover, it is impossible to determine its market value in accordance with the Real Estate Management Act. Otherwise, the calculation will relate to a value other than the market value.

1.4. Mineral Property, Mineral Resources Ownership, Mining Rights in Poland

The mineral assets management and ownership is subject to the Polish Act of 9 June 2011, the Geological and Mining Law []. It states that deposits of hydrocarbons, hard coal, methane occurring as an accompanying mineral, lignite, metal ores, with the exception of brown iron ores, native metals, ores of radioactive elements, native sulfur, rock salt, potassium salt, magnesium salt, gypsum and anhydrite, and gemstones, regardless of their place of occurrence, as well as deposits of curative (medicinal) waters, thermal waters, and brines, are covered by mining ownership. The deposits of minerals not listed above are governed by the law of real estate ownership of land. Mining ownership also includes parts of the rock mass located outside the spatial borders of the land property, particularly those located within the maritime areas of the Republic of Poland. The right of mining ownership is owned by the State Treasury.

In the extractive industry, some projects may never be developed due to physical or environmental socioeconomic constraints, or they may be considered developable in the future as technological or environmental socioeconomic conditions change. It is important to note that even if the resources are economically viable for extraction, it is up to the governing body to decide whether the environment should be impacted or remain untouched (for instance, in local spatial development plans). In research [] authors compared the Polish classification of the mineral resources with the JORC Code (CRIRSCO), PRMS, and UNFC (2008). The Polish classification is based on similar rules to those of the UNFC Update 2019, and by making some assumptions, the respective classes of the UNFC can be identified between the two. Some of them are not formally used in Poland—for example the exploitable resources of solid raw materials [].

1.5. Environmental Concerns and Water Protection in Malaysia

Environmental concerns in Malaysia related to mining activities, particularly those affecting water-covered land, have grown significantly in recent years. One of the most prominent examples is the bauxite mining in Kuantan, where unchecked extraction led to widespread water pollution. The red sediment runoff contaminated rivers and coastal waters, harming aquatic ecosystems and affecting the livelihoods of nearby communities. This environmental degradation led to a temporary moratorium on bauxite mining by the Malaysian government []. Malaysia’s environmental governance structure places land and water matters under the jurisdiction of individual states, as stipulated by the Federal Constitution. Each state enacts its own land and water laws, which include specific rules on environmental management. However, enforcement remains inconsistent, particularly when economic incentives conflict with sustainability goals. Often, regulatory gaps or lack of inter-agency coordination hinder effective protection of water resources []. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a critical regulatory tool in Malaysia to ensure that mining projects, especially those involving water bodies, consider potential environmental damage. The Department of Environment (DOE) and the Department of Irrigation and Drainage (DID) play pivotal roles in approving and monitoring such projects. However, concerns remain regarding the transparency and comprehensiveness of some EIA processes, with critics arguing that in some cases, assessments are either bypassed or under-reported []. Moving forward, sustainable mining practices in Malaysia require a multi-dimensional approach by integrating technology, policy reform, and community engagement. There is growing advocacy for stricter water protection laws and incentives for companies that adopt eco-friendly extraction methods. Long term environmental protection will depend on effective monitoring systems, stakeholder cooperation, and aligning economic development with ecological preservation [].

1.6. Land Ownership in Malaysia

Land ownership in Malaysia is governed primarily by the Federal Constitution, which allocates authority over land matters to individual states. This means that each state in Malaysia has jurisdiction over its own land policies and administration, leading to variations in land laws and procedures across the country. The National Land Code 1965 (Act 56) serves as the principal legislation for land matters in Peninsular Malaysia, while Sabah and Sarawak operate under their own respective land ordinances []. The structure of land ownership in Malaysia is based on a system of registered titles. The Torrens system is adopted, where the register maintained by the land office serves as conclusive evidence of ownership. Titles issued can include freehold (perpetual ownership), leasehold (ownership for a specific period, typically 99 years), and temporary occupation licenses. The distinction between freehold and leasehold is significant in terms of rights, renewal options, and the ability to transfer or develop the land []. In Malaysia, the State Authority is the ultimate owner of all land, and private individuals or entities only have rights to occupy or use land through registered titles or leases. This concept, known as the doctrine of “state land”, means that any unalienated land automatically belongs to the state. As a result, the state plays a crucial role in approving land conversions, alienation, and developments, which can affect planning, housing, and industrial activities []. The complexity of land ownership is further heightened in cases involving indigenous land, agricultural reserves, and lands covered by water. For instance, the ownership and use of water-covered land such as rivers, lakes, and coastal zones may fall under separate categories and involve additional layers of approval. In such cases, overlapping jurisdiction between federal and state authorities can lead to bureaucratic delays or disputes. Hence, there is ongoing debate about harmonizing land laws to improve governance and equity in land ownership across Malaysia [].

1.7. Ownership of Land Covered by Water in Malaysia

Ownership of land covered by water in Malaysia is primarily governed by state land laws and the National Land Code 1965 (NLC), with jurisdiction resting under the State Authority. According to the Federal Constitution, land (including rivers, lakes, and coastal areas) is a state matter, which means that each state may determine how water-covered lands are classified, alienated, and regulated. In general, land beneath natural water bodies such as rivers and lakes that is not typically alienated to private individuals unless explicitly approved by the state, as it is considered part of the public domain []. The National Land Code does not provide specific clauses for the ownership of water-covered land, but under Sections 62–66, state authorities have the discretion to reserve or alienate land under water for public purposes or for use by approved entities. This includes cases where a portion of a water body is converted for economic purposes, such as aquaculture, tourism, or mineral extraction. However, access and use are usually regulated through licenses or temporary occupation permits (TOPs), not outright ownership, thereby maintaining state control over such lands []. In practice, land covered by water is often associated with overlapping claims and jurisdictional challenges, particularly in cases involving federal infrastructure projects (such as dams or ports), native customary rights (especially in Sabah and Sarawak), or private developments near water bodies. For example, disputes may arise when private developers seek to reclaim coastal land or utilize riverfront areas, triggering issues of environmental protection, indigenous rights, and public access. These challenges are compounded by the lack of comprehensive legal provisions specifically addressing submerged land tenure []. With the increasing demand for water-based land uses such as hydropower, tourism, and mineral extraction, there is a pressing need for more detailed, transparent, and harmonized regulatory frameworks. Scholars and practitioners have called for clearer statutory definitions and stronger institutional coordination to prevent encroachment, ensure environmental sustainability, and uphold equitable access. As land and water management become increasingly intertwined due to climate and development pressures, the legal treatment of water covered lands in Malaysia will remain a critical policy area [].

1.8. Mineral Property, Mineral Resources Ownership, Mining Rights in Malaysia

In Malaysia, ownership of mineral resources and the rights to explore or extract them are regulated primarily by the Mineral Development Act 1994 (Act 525) at the federal level, and the State Mineral Enactments at the state level. Although the federal government plays a central role in policy and licensing for certain minerals, the actual ownership of land and mineral resources lies with the respective State Authorities, as land matters are under state jurisdiction according to the Federal Constitution. This dual structure necessitates coordination between federal and state bodies, particularly when it comes to issuing exploration and mining leases []. The Mineral Development Act 1994 empowers the Department of Minerals and Geoscience (JMG) to supervise mineral exploration and development activities. However, actual mining rights, including the issuance of prospecting, exploration, and mining licenses, are granted by the states under their own mineral enactments. These rights do not constitute ownership of the land or minerals but are considered a form of statutory license to extract and benefit from the resources for a specified duration and under defined conditions []. Ownership of mineral property in Malaysia is therefore separated from surface land ownership. A landowner does not automatically own the minerals beneath their land, unless explicitly granted by the state. The state retains the prerogative to approve or deny mineral extraction even on privately owned land, and may also impose environmental or social impact assessments (EIA or SIA) before granting mining approvals. This distinction often leads to legal and commercial complexities, particularly in areas involving customary land rights or environmentally sensitive zones []. In recent years, controversies such as the bauxite mining crisis in Kuantan have highlighted the need for more sustainable and transparent governance in Malaysia’s mining sector. Issues surrounding illegal mining, environmental degradation, and lack of enforcement have pushed for reforms in how mining rights are awarded and monitored. There is growing advocacy for better coordination between federal and state agencies, more stringent regulatory enforcement, and clearer frameworks for the valuation and leasing of mineral-bearing land []. These reforms are crucial to balancing economic development with environmental protection and social responsibility.

Our research aims to provide analysis of water governance components by presenting the complexity of water-covered land use by the extractive industry in terms of legal, economic, and environmental protection aspects in Poland and Malaysia, along with the corresponding regulations for determination of fee for extraction. Furthermore we wish to discuss the level of this fee and its implications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area—Poland and Malaysia as Selected EU and ASEAN Member States

The study presented in this research paper is based on the authors’ international collaboration as researchers from selected countries. Both Poland and Malaysia function as influential and strategically vital members within their respective regional blocs—the European Union (EU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as presented in Figure 1. While their founding roles differed, with Malaysia being an original 1967 founder of ASEAN and Poland joining the EU in its 2004 expansion, both countries have become central players in regional integration. The comparison of countries water regulations is even more interesting due to similarities in country area and population (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Research area Poland (left) and Malaysia (right) as selected EU and ASEAN Member States (circled), based on source: https://european-union.europa.eu/, https://commons.wikimedia.org/.

Table 1.

Comparative basic data: Poland and Malaysia, source: World Economic Outlook Database April 2025, wikipedia.org, Department of Statistics Malaysia, Polish Central Statistical Office.

Both nations serve as crucial connector states and economic hubs. Poland participates fully in the EU Single Market, leveraging its strong industrial base and skilled workforce to become a major manufacturing and logistics hub, bridging Western Europe (especially Germany) with the Eastern Flank. It benefits from the EU’s four freedoms (free movement of goods, capital, services, and people). Similarly, Malaysia is a key participant in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which aims for a single market and production base. Its developed infrastructure, open trade policies, and strategic location serve as a bridge between ASEAN and other global economies. Like Poland, Malaysia hosts numerous regional events and facilities, reflecting its role as a diplomatic and logistical hub. Their geographic positions are central to their influence. Poland is situated at the crossroads of the European plain, straddling major East-West transport corridors. Its position provides crucial land access between Western Europe and the East, while its Baltic Sea coast offers maritime access. Malaysia’s position is equally strategic, located in the heart of Southeast Asia and straddling the Strait of Malacca, one of the world’s most critical maritime trade routes. This dual-coast position provides direct access to both the Pacific and Indian Oceans, making it a natural hub for global shipping and trade, and a gateway between emerging and developed markets. In sustainable development, both countries engage with their bloc’s frameworks. Poland supports the EU’s European Green Deal, though its heavy reliance on coal often creates internal friction with EU-wide carbon targets, leading it to advocate for a just transition. Malaysia supports ASEAN’s framework on issues like climate change adaptation and transboundary haze pollution, advocating for regional cooperation in managing shared natural resources.

2.2. Sand and Gravel Mineral Aggregates in Poland with Reference to Water Land Coverage

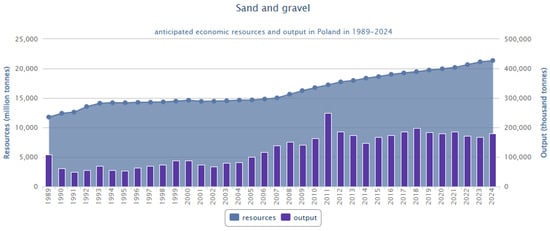

According to the Mineral Resources of Poland 2025 [], sand and gravel mineral aggregates constitute an important share of the total amount of mineral resources. Figure 2 shows the changes in domestic resources of sand and gravel production in Poland in the years 1989–2024. As compared to Malaysian production in 2022–2023, Poland has produced approximately 4–5 times more 170,776 and 167,078 thousand tonnes, respectively.

Figure 2.

Changes in anticipated economic resources and production of sand and gravel in Poland in the years 1989–2024 source: A series of annual reports on the balance of mineral resources in Poland, http://pgi.gov.pl/.

Mineral resource reporting can vary depending on national codes and regulations. Based on [], we provide mineral resource information in Table 2 in accordance with Polish regulations and the United Nations Framework Classification for Reserves and Resources for Solid Fuels and Mineral Commodities. As mentioned by [], The UNFC Update 2019 distinguishes four grades of deposit exploration: G1, G2, G3, G4 These grades correspond to the Polish categories: A + B, C1, C2, D, and D1–D3. The most substantial differences between the Polish system and the UNFC Update 2019 are the presentation of resource data in Poland, which is hierarchical, whereas the UNFC Update 2019—like other international systems—is complementary. Another difference is the lack of formal designation in Poland for exploitable resources (especially in the case of solid mineral deposits), which in Anglo-Saxon terminology are referred to as “reserves”. To attain full compatibility between the Polish system and the UNFC, ref. [] suggests that data on Polish resources should be released separately:

Table 2.

Sand and Gravel mineral resources in Poland in national and UNFC Update 2019 classification, 2020 year (presented based on source: The balance of mineral resources deposits in Poland as of 31 XII 2020 (in Polish) [].

- in the case of exploited deposits (deposits licensed for mining)—economic resources in place (21× according to the UNFC Update 2019), sub-economic resources (31×), anticipated economic resources not qualified as economic and sub-economic resources 22×), anticipated sub-economic resources (32×);

- in the case of non-exploited deposits (beyond concession areas)—anticipated economic resources (23×), anticipated sub-economic resources (33×). There should also be a distinction made for prognostic resources—class 234 and 334.

Therefore, economic resources in place can be presented as: 21× (economic resources) = 11× (extractable resources) + 31× (losses). Available resources of sand and gravel presented in The balance of mineral resources deposits in Poland are also differentiated by the development status of the deposit. Abbreviations for the development status of resources in deposit are as follows: E—producing (exploited) deposit; T—developed deposit, operated periodically; B—mine under construction; P—deposit with preliminarily explored resources (cat. C2 + D); R—deposit with thoroughly explored resources (cat. A + B + C1).

The comparison of the Polish Mineral Resources Classification of sand and gravel to the UNFC Classification (Update 2019) is expressed in Table 2.

It should be noted that there is a certain disparity in the presentation of mining and geological data between Poland and Malaysia. In Poland, detailed data concerning the quantity of resources, exploitation boundaries, and deposit documentation (spatial data—shape files) is publicly available, whereas in Malaysia, this data is not as openly published.

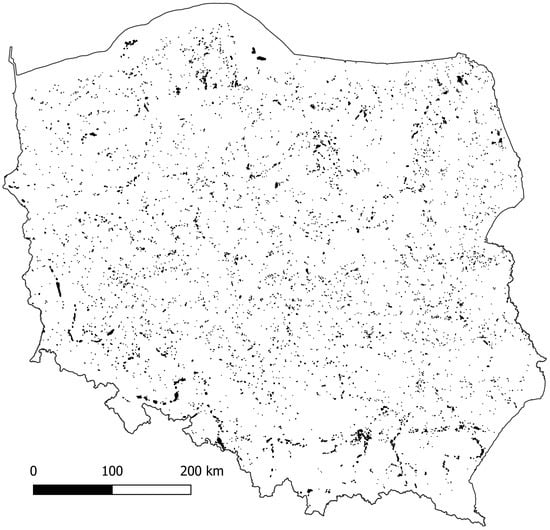

Due to the implementation of the Inspire Directive [] and Poland’s strong traditions in Surveying and Mapping, extensive collections of spatial data are available in Poland. For the purpose of this research, we have used The Topographic Objects Database, hereinafter referred to as BDOT10k. It represents a new quality compared to decades-old classical topographic and general geographic maps. They have emerged as a result of the evolution of methods for acquiring and managing spatial data. This database constitutes one of the essential elements of the Polish spatial information infrastructure. The primary goal of constructing a modern resource of topographic databases is defined similarly in most highly developed countries around the world. BDOT10k is a reference database. Its purpose is to collect and provide data for use in various information systems, including spatial information systems. The fundamental idea behind creating such databases is to reduce the multiple acquisition of the same data by different institutions and companies []. The widespread use of topographic databases significantly influences the possibilities of exchanging specialized data among various spatial information systems (utilizing the same reference data in such situations) and allows the execution of analyses that were previously inaccessible. The Polish BDOT10k database, in terms of representation of watercourse networks, includes three fundamental objects published in GML format. These consist of linear features such as rivers and strims, drainage ditches and channels. Surface water is also a subject of the Land Cover group of objects which are represented by polygons. These include standing waters (inland and sea) as well as running waters, but only if the watercourse width exceeds 5 m. Object in database may have different categories of geometric accuracy and various sources of the geometry data. Another source of data is MIDAS database []. The source of data, included in the MIDAS database, in the section—Mineral deposits, are geological documentations of mineral deposits, prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Geological and Mining Law. Spatial data for documented deposits (boundaries of deposits, mining areas and mining lands) are presented in the mapping part of the MIDAS system in the form of WMS and WFS services and SHP (shapefile) also presented in Figure 3. For spatial data analysis QGIS 3.40.7 software was used.

Figure 3.

Occurrence of documented Sand and Gravel natural aggregates in Poland, own study based on the MIDAS database [].

As observed in Table 3, the specific type of extraction from flowing inland waters accounts for 269 cases (different valid concessions for extraction) in Poland, whereas extraction from inland flowing waters with a width exceeding 5 m accounts for only 21 cases. In total, there are 616 sand and gravel mineral deposits that intersect with flowing inland waters, which can be considered a reserve for this type of exploitation. In fluvial environments, natural aggregate deposits are predominantly composed of alluvial sediments. Consequently, there remains significant potential for the identification and documentation of additional deposits located beneath flowing inland waters, so that a clear and just mechanism for setting fees for using State water-covered properties for mining purposes should be established in connection with the economic environment. The occurrence of groundwater at various depths—including shallow aquifers—commonly results in inflow into excavation sites during open-pit mining operations. There are 3036 cases of extraction from standing inland waters. However, according to the spatial database, it is difficult to precisely differentiate whether we are dealing with exploitation from a water reservoir formed prior to mining activities or if the extraction itself has led to the formation of a shallow reservoir. A more accurate identification of this phenomenon will be analyzed in a subsequent research paper.

Table 3.

Statistics of sand and gravel mineral deposits in Poland in relation to flowing and standing waters (own study).

2.3. Current Principles for Setting Fees for Using Water-Covered Properties for Mining Purposes in Poland

To address the issue of setting fees for using water-covered properties for mining purposes, we need to consider both the economic and legal aspects. In Poland, the bundle of property rights is derived from the Civil Code. This is significant because ownership rights are crucial in a market economy. A mining entrepreneur who applies for a concession to extract minerals not covered by mining rights (i.e., sand and gravel) must have a specific right to use the property []. Dividing the water-covered properties (property rights) into two categories private and state-owned, it is important to acknowledge that setting fees for private sector is subject to the freedom of contract, where as state-owned properties have their own regulations for setting fees.

2.4. Fees for Using State Owned Water-Covered Lands in Poland

State owned lands covered by water for the purpose of mining activities related to the extraction of stone, gravel, sand, as well as other materials, are subject to usufruct for an annual fee. Here, attention should be paid to the term ‘usufruct’ which is one of the forms of property ownership, as presented in the earlier provisions of the Civil Code.

According to the article 262 of the Water Law Act, the maximum annual fee for the use of 1 of land cannot exceed ten times the upper limit of the property tax rate specified in the Act on Local Taxes and Fees. The property tax rate for lands used for business purposes, regardless of how they are classified in the land and building register as for 2025 is at the time of writing this article, is 1.38 PLN/ of surface area (as compared to 0.62 PLN/ in 2023, USD/PLN exchange rate as of 10 October 2025 is 3.6726). Therefore, the upper limit determined in the above manner cannot exceed 13.80 PLN/ (6.20 PLN/ in 2023), which is notably high, especially when considering the exploitation fee rate. In more illustrative terms, it is almost the same as the unit transaction price of agricultural land with sand and gravel mineral deposits.

The above information provides maximum rate. Quoting further the Water Law Act, ‘The Council of Ministers shall determine the amount of the individual annual fees for the use of 1 of land in a regulation, guided by the types of projects for which lands covered by waters are provided for use.’

According to the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 28 December 2017, on the amount of annual unit fees for the use of lands covered by water [], owned by the State and necessary for activities related to the mining extraction is 0.50 PLN/. Reading the above provisions, it is evident that currently the fee for using lands covered by waters for underwater exploitation is basically 0.50 PLN/. However, there is a certain gap in the procedure that allows for the application of other regulations, such as fee for the land lease instead of the fee specified for the usufruct.

Polish Waters represent the State Treasury and exercise the proprietary rights of the State Treasury in relation to waters referred to in Article 212(1)(1) and to lands covered by inland flowing waters. According to Article 264 of the Water Law Act Polish Waters, within the scope of their property, may dispose of Real Properties that are not mentioned in Article 261(1), built-up lands with water installations located beyond the shoreline, or water installations or their parts that are the property of the State Treasury, by establishing limited property rights, leasing, renting, lending, or exchanging, and the revenues from this constitute their income.

In such a case, the fee rates (for leasing) are specified in the Regulation of the President of the Polish Waters on 7 June 2022 [], in which the annual lease rent for mining purposes is calculated as five times the exploitation fee rate increased by 1 PLN/ as for reclamation fee.

According to the 2025 fee rates based on the Geological and Mining Law [], the extraction of sand and gravel is currently subject to a fee of 0.87 PLN/t (0.72 PLN/t as for 2023). If we apply five times this rate and increase it by 1 PLN/, we obtain an annual lease rate of 5.35 PLN/. This is more than ten times the rate of usufruct specified in the above mentioned regulations.

The component of the reclamation reserve in the leasing fee is somewhat unclear because, according to the law, any reclamation will be carried out by the entity exploiting the deposit. A very interesting aspect of underwater mining is that it contributes to the deepening of rivers and reservoirs, thereby increasing retention. The mere fact of reclaiming areas (reservoirs) after mining activities is a relatively underexplored topic.

Due to amendment of Regulation of the President of the Polish Waters on 7 June 2022 [], the following regulation was added: In cases of intention to lease a property or part of it, in accordance with Articles 38–41 of the Act of 16 December 2016 on the Principles of Management of State Property (Journal of Laws of 2023, item 973, as amended), the rent value is determined by a valuation prepared by a property appraiser in compliance with the aforementioned provisions of the Act.

In the Act on the principles of state property management [], article 38 states that any legal act performed by a state legal entity concerning the disposal of fixed assets as defined by the Accounting Act of 29 September 1994 (classified as intangible assets, tangible fixed assets, or long-term investments) requires consent if the market value of these assets exceeds 200,000 PLN. This includes contributing them as capital to a company or cooperative. According to the provisions of the above mentioned Act, for the purpose of granting the consent, the market value of the subject of the legal act is, in the case of lease, tenancy, and other agreements for making the asset available to other entities for paid use—the value of payments for

- One year—if the asset is made available under an agreement concluded for an indefinite period;

- The entire duration of the agreement—in the case of agreements concluded for a definite period.

2.5. Sand and Gravel Mineral Aggregates in Malaysia with Reference to Water Land Coverage

Sand and gravel are often referred to as mineral aggregates that are among the most extracted raw materials in Malaysia. These resources are critical to the construction industry, providing essential inputs for concrete, road base, and land reclamation projects. In Malaysia, a significant portion of these aggregates is extracted from rivers, lakes, and seabed areas, particularly in states like Perak, Selangor, Johor, and Sabah, where demand is high due to rapid urban development and infrastructure expansion. The extraction of sand and gravel from water covered land falls under a combination of mineral resource regulations and land and water laws, due to their location beneath public waterways or state controlled marine zones. The Mineral Development Act 1994 governs licensing and monitoring of mining operations, while the National Land Code 1965 and Water Enactments at the state level define jurisdiction over riverbeds and seabeds. As these locations are considered state land or reserved land, any removal of sand and gravel requires specific licenses or permits issued by State Authorities, often involving multiple agencies such as the Department of Minerals and Geoscience (JMG), Department of Environment (DOE), and the Drainage and Irrigation Department (DID).

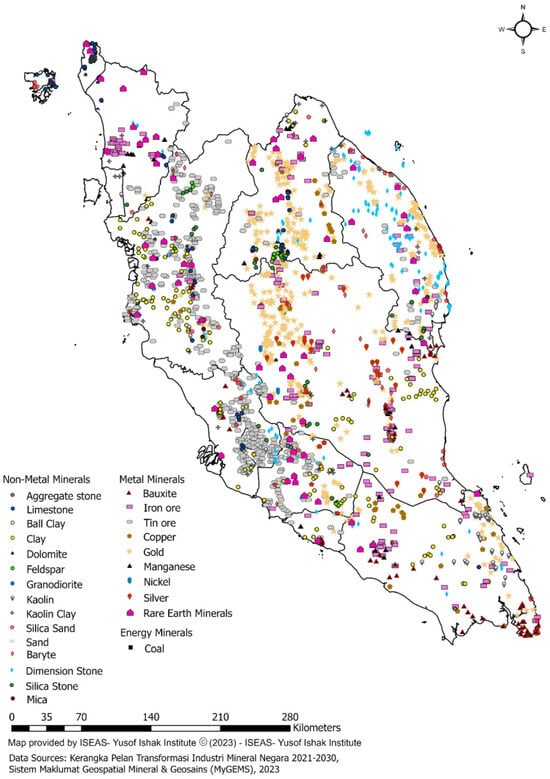

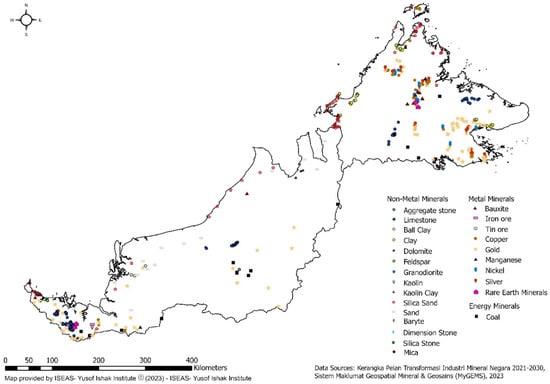

A key challenge is balancing resource extraction with environmental protection. Excessive river sand mining, especially in Perak and Pahang, has led to concerns over riverbank erosion, habitat destruction, sedimentation, and even flood risk. Extraction from submerged land or subaqueous zones also raises legal and technical complexities, particularly in determining boundaries of mining rights and monitoring compliance. In addition, enforcement has been uneven, resulting in cases of illegal sand mining and unregulated exportation to foreign markets. Malaysia is now moving toward more sustainable aggregate governance. New guidelines issued under the Mineral Industry Strategic Plan 2021–2030 emphasize integrated planning, stricter environmental impact assessments (EIA), and geospatial monitoring for underwater and coastal aggregate extraction. These frameworks are vital in addressing both the economic importance of sand and gravel and the ecological sensitivity of water covered lands. Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the occurrences of sand and other mineral resources in Malaysia.

Figure 4.

Sand and other mineral resources in peninsular Malaysia, source: ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute.

Figure 5.

Sand and other mineral resources in Eastern Malaysia—part of Borneo island, source: ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute.

In 2020, Malaysia’s mineral industry extracted primarily metallic ores as well as crude petroleum and natural gas. The country also produced a considerable amount of refined tin, from both domestically produced and imported tin concentrates, and rare-earth oxide (REO) compounds, mostly from imported rare-earth mineral concentrates. Malaysia estimated Sand and gravel production for 2020 was 35,681 Mt []. The Malaysia has abundant sand and gravel resources, located mainly in river beds, alluvial plains, offshore areas and mine tailing dumps in the States of Perak, Kedah, Johor, Selangor and Sarawak. They are important raw materials for the construction of buildings and infrastructures. Table 4 shows the production and trade statistics for sand and gravel in 2023 compared to the previous year. Malaysian sand and gravel production as for 2023 has a 20.16% share in Mass in Non-Metallic Mineral production, which also is accounted for 18.55% share in Value (18.55% from 4406.81 RM million. USD/MYR exchange rate as of 10 October 2025 is 4.2230).

Table 4.

Sand and gravel production in Malaysia (2022–2023).

In Malaysia, while comprehensive national statistics on sand and gravel mineral deposits intersecting with water bodies are not publicly consolidated to the same granularity as Poland’s dataset which can be observed in Table 5. However, the Department of Irrigation and Drainage Malaysia (DID) and Selangor Water Management Authority (LUAS) indicate that fluvial and floodplain environments host a significant number of sand and gravel extraction sites, many of which overlap with standing and flowing inland waters [,]. The country has abundant sand and gravel resources located mainly in riverbeds, alluvial plains, offshore areas, and mine tailing dumps, and these materials serve as vital inputs for the construction of buildings and infrastructure []. These deposits, primarily composed of alluvial sediments, are exploited under mining leases or temporary occupation licenses, with concessions subject to environmental impact assessments under the Environmental Quality Act 1974 []. The relationship between the location of sand and gravel resources and nearby water bodies makes the scope of this article particularly relevant.

Table 5.

Statistics of sand and gravel mineral deposits in Malaysia in relation to flowing and standing waters (own study).

2.6. Current Principles for Setting Fees for Using Water-Covered Properties for Mining Purposes in Malaysia

To address the issue of setting fees for using water-covered properties for mining purposes in Malaysia, it is essential to consider the decentralized nature of land and mineral governance. Under the Federal Constitution, states hold jurisdiction over land and water resources, resulting in regulatory and fee-setting variations across the country []. For instance, in Sarawak, mining activities on submerged lands within national parks or forest reserves are tightly regulated under the Sarawak Natural Resources and Environment Ordinance 1958 [] and the Minerals Ordinance 2004 [], with fees often incorporating environmental restoration costs and biodiversity protection measures. In contrast, Pahang applies its own State Mineral Enactment 2001 [], where concession fees are influenced by the commercial value of the mineral, the scale of extraction, and the location’s proximity to water bodies. Kedah and Kelantan, responding to recent discoveries of non-radioactive rare earth elements (NR-REEs), are revising licensing frameworks to include stricter environmental impact assessments and differentiated fee structures for water-adjacent sites [,], These differences reflect broader policy goals outlined in the National Mineral Industry Transformation Plan 2021–2030 [], which promotes sustainability, ecological compensation, and incentives for green mining technologies. As such, a mining operator must not only secure the right to use water-covered properties through state-issued tenements but also navigate a complex landscape of environmental compliance and variable financial obligations depending on the state in which the activity occurs.

2.7. Fees for Using State Owned Water-Covered Lands in Malaysia

In Malaysia, the use of state-owned water-covered lands for mining purposes, such as the extraction of sand, gravel, or other minerals, is governed by a combination of federal legislation and state-specific regulations, with fees determined primarily at the state level. Unlike Poland, where usufruct is a formal legal category tied to the Civil Code, Malaysia does not apply a uniform concept of usufruct to submerged lands. Instead, rights to use such lands are typically granted through leases, licenses, or temporary occupation permits under respective State Land Codes and State Mineral Enactments. For example, in Selangor, sand mining lease fees ranging from RM250 per hectare annually, plus RM2.00 per tonne of extracted material, as outlined in the Selangor Minerals Enactment 2000 []. In Pahang, lease fees are higher and include additional charges for environmental monitoring and post-mining rehabilitation, as required under the Pahang Minerals Enactment 2001 []. In practice, the total cost to a mining operator includes not only the lease or license fee but also royalties, environmental impact assessment charges, and—where applicable—community compensation or benefit-sharing arrangements.

3. Results

In Table 6, we present a comparison of fees applied to different property rights with respect to the use of Polish state-owned land covered by water.

Table 6.

Comparison of fees applied to different property rights regarding Polish Water land use (own study).

Table 7 reveals a fundamental divergence in how Malaysian states operationalize property rights and fee structures for mining activities on water-covered lands. The Mining Lease mechanism offers stronger legal protection and long-term security for operators, but it is contingent on the existence of clearly demarcated cadastral boundaries. This requirement often excludes ecologically sensitive or hydrologically dynamic areas, where cadastral mapping is incomplete or contested. In such cases, the Temporary Occupation License (TOL) becomes the default instrument, despite its weaker legal standing and shorter tenure.

Table 7.

Comparison of fees applied to different property rights regarding Malaysian water-covered land use for mining (own study).

From a financial governance perspective, the fee structure under Mining Leases is more predictable, as it is codified in state mineral enactments and land rules. Operators can anticipate annual land rent and royalty rates, which facilitates financial planning and investment decisions. However, this predictability may come at the cost of environmental flexibility, as leases are often granted for longer durations (up to 30 years), potentially locking in extractive activities in areas that may later be designated for conservation or community use.

In contrast, TOLs offer administrative flexibility and are often used in transitional or exploratory contexts. Their fees are determined on a case-by-case basis by the State Land Office, incorporating premiums, reclamation bonds, and biodiversity offset charges. While this allows for more responsive environmental governance, it also introduces uncertainty for operators and may deter long-term investment. Moreover, the lack of registrable property rights under TOLs raises concerns about tenure security, especially in states where land-water boundaries are politically or ecologically sensitive.

The environmental implications of these tenure mechanisms are also significant. Mining leases require full Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and rehabilitation plans, aligning with federal mandates under the Environmental Quality Act 1974. TOLs may only require preliminary assessments, which can result in weaker oversight, particularly in high-risk aquatic ecosystems.

In sum, the table illustrates not just a technical comparison of tenure instruments, but a broader tension between legal certainty and environmental adaptability, financial predictability and administrative discretion, and extractive access and ecological stewardship. These dynamics are central to Malaysia’s evolving approach to sustainable mineral governance, especially in water-linked landscapes where competing land uses and conservation priorities intersect.

4. Discussion

In reference to the research conducted by [], we have provided additional research aligned with the literature screening process presented by the authors. Our research, written in English, focuses on at least two countries: Poland and Malaysia. We have provided an in depth analysis of the regulatory landscape for enabling water-covered land use for the extractive industry, pinpointing a possible lack of careful economic assessment from the government perspective.

As presented in [], the authors’ initial findings suggest the possibility of a water Kuznet’s curve, indicating that certain water governance indicators vary with a country’s level of economic development. Although such an indicator was not calculated for Poland and Malaysia, our research presented in this paper shows clear differences in water governance in both countries. Compared to Malaysia, Poland is considered a high-income, developed market economy aspiring to join the G20 group, whereas Malaysia is classified as an upper-middle-income economy that is on its way to achieving high-income (developed) status in the near future. As observed, Polish regulations are more centralized than those in Malaysia, however, this is due not only to economics but also to history and geography.

While investigating the provisions and regulations regarding environmental impact mitigation and assessment, we found that both countries acknowledge the risks associated with underwater mining, as indicated in research on structural economic assessment of underwater project [].

The State Water Holding Polish Waters, as the primary entity responsible for national water management in Poland, operates with a mandate focused on protecting against floods and drought and ensuring sustainable water resources. However, the institution does not possess the specialized expertise in mineral resource valuation required to accurately determine income streams from the sale of minerals or to establish appropriate capitalization rates for the mining industry. This area of expertise is highly specialized. A potential knowledge gap is highlighted by an existing regulatory provision that requires the consent of Polish Waters for the disposal of assets when their market value exceeds 200,000 PLN. The methodology for calculating this market value is not uniform; it differs depending on whether the legal action involves a lease or the sale of real property. In the case of a lease, the market value of the lease itself must be determined, whereas for a property sale, the value of the real estate is the reference point. Given that the valuation of mineral assets is a complex process requiring specific knowledge in geology, mining, and economics, it is plausible that Polish Waters may not be equipped to determine the market value of its sand and gravel assets. This suggests a potential discrepancy between the institution’s regulatory responsibilities concerning asset disposal and its inherent expertise, which is centered on water management rather than mineral economics.

Based on this research, the setting of fixed lease rates is considered inadequate for varying market conditions and geological uncertainty in the deposit. Therefore, according to the authors of this paper, there is a need to establish a calculation formula that takes into account both the legitimate interests of the State Treasury as the owner of lands located above mineral deposits and the entrepreneurs engaged in or planning to undertake the exploitation of such deposits. In the authors view, the basis for determining lease rates should be market characteristics of both the property and its component in the form of the mineral deposit, which are clear to all parties involved and verifiable. Such property characteristics should include

- Location;

- The amount of mineral reserves;

- Type of mineral and its attractiveness;

- Environmental, technical, transportation, and other conditions;

- Constraints on the flexible scale of exploitation.

Therefore, it is suggested that the market value of land located above a mineral deposit, calculated individually for each deposit-property, should serve as the basis for calculating the lease fee.

In the Malaysian context, similar challenges arise due to the decentralized governance of land and mineral resources. States such as Pahang, and Selangor apply different fee-setting mechanisms depending on cadastral clarity, mineral type, and ecological sensitivity. However, none of the states currently employ a dynamic valuation model that adjusts lease rates based on market fluctuations or deposit-specific characteristics. This gap mirrors the Polish experience and underscores the need for a valuation framework that integrates both geological and economic variables. Detailed solutions require discussion in a broader context. This discussion should encompass not only the principles and methodology involved in estimating the magnitudes of lease rents in the mining industry and its profitability but also the identification and criteria for assessing the risks associated with ongoing or planned mining ventures. These risks may include hazards, floods, seasonal interruptions of river navigation during winter, and concerns about the protection of river ecosystems. In Malaysia, additional risk factors include monsoonal flooding, impacts of sedimentation on river morphology, and resistance of communities in ecologically sensitive zones. The Environmental Quality Act 1974 [] mandates EIAs for water-linked mining, but enforcement varies across states, and valuation rarely reflects the full cost of environmental degradation.

An essential point to consider in this discourse is that, when valuing properties, the chosen valuation method is contingent upon the purpose of the valuation. There exists a prevalent perspective in the field of expropriations that the sum of contractual obligations and property rights, in principle, should not surpass the market value of the property. This is because an informed buyer will not pay more for a property than they would for another with similar characteristics. It appears that a similar principle should be applied to properties leased by State Water. In Malaysia, this principle is reflected in land acquisition and compensation practices under the Land Acquisition Act 1960, where market value is the ceiling for compensation. However, mining leases and TOLs often include layered fees—royalties, premiums, environmental bonds—that may exceed the land’s market value, especially in cases where mineral deposits are marginal or speculative. This raises questions about the proportionality and transparency of fee structures in water-covered land use.

As mentioned earlier in this article, the high annual fees starkly contrast with the transaction prices for agricultural land with natural mineral deposits. This contrast is also evident in Malaysia, where land designated for mining—particularly sand and gravel extraction—is often priced below the cumulative cost of lease fees, royalties, and environmental charges. Without a valuation model that accounts for mineral quality, processing potential, and market demand, fee structures risk deterring responsible investment or incentivizing informal extraction. An essential point to consider in this discourse is that, when valuing properties, the chosen valuation method is contingent upon the purpose of the valuation. There exists a prevalent perspective in the field of expropriations that the sum of contractual obligations and property rights, in principle, should not surpass the market value of the property. This is because an informed buyer will not pay more for a property than they would for another with similar characteristics. It appears that a similar principle should be applied to properties leased by State Water. As mentioned earlier in this article, the high annual fees starkly contrast with the transaction prices for agricultural land with natural mineral deposits.

It is evident that the rent rate for mineral properties with low-quality deposits should be lower than for a mineral deposit allowing high revenues, for example, through the production of highly processed aggregates (such as gravel) that obtain higher prices in the market. It is important to emphasize that determining the rent rate based on the income value of the property with a mineral deposit requires specialized knowledge and experience from real estate valuers, or other practitioners, but due to the Polish Land Management Act, real estate appraisers are licensed for real property valuation that includes sand and gravel. There are entities recognizable locally and internationally that are specialized in mineral property appraisal such as the self-governing body, the Polish Association of Mineral Asset Valuators (PAMAV) or International Mineral Valuation Committee (IMVAL) composed of representatives of VALMIN (Australasia), CIMVAL (Canada), SAMVAL (South Africa), SME Valuation Committee (USA), International Institute of Minerals Appraisers (USA-based), with additional observer organizations from the UK, USA, and China. On the other hand, this also reinforces the need for capacity-building within Malaysian state land and mineral departments. As highlighted in the Malaysian National Mineral Industry Transformation Plan 2021–2030, there is a strategic push to integrate economic valuation and ESG metrics into mining governance. However, implementation remains uneven, and valuation expertise—particularly for submerged or ecologically sensitive lands—is still developing. In Malaysia, while there is no dedicated national committee for mineral asset valuation equivalent to the above-mentioned, valuation activities are regulated under the purview of the Board of Valuers, Appraisers, Estate Agents and Property Managers (BOVAEP) and supported by the Valuation and Property Services Department (JPPH). In addition, the Department of Mineral and Geoscience Malaysia (JMG) and the Institute of Geology Malaysia (IGM) have increasingly collaborated with valuation professionals and academic institutions to improve mineral property appraisal standards, particularly in the context of rare earth element and strategic mineral development. This highlights the need for specialized valuation frameworks tailored to the geological and regulatory landscape of Malaysia. A key finding of our research is that, in our opinion, the water governance frameworks in Poland and Malaysia are inadequate for protecting public finances and for internalizing the environmental externalities inherent in the economics of mining.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; methodology, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; validation, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; formal analysis, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; investigation, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; resources, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; data curation, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; writing—review and editing, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; visualization, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; supervision, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; project administration, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H.; funding acquisition, M.W.D., N.H.A.M. and E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Our deepest appreciation to the Government of Sarawak for the financial support provided through Geran Kursi Premier Sarawak (cost centre: R.J130000.7352.1R067). Also this research was funded by subsidy of Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education executed at Wrocław University of Science and Technology. APC was funded by subsidy of Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education executed at Wrocław University of Science and Technology.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. (For Polish datasets, they are included in national repositories and available to download upon acceptance of terms and conditions https://dm.pgi.gov.pl/ and www.geoportal.gov.pl, other data sources are presented as references in article).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Özerol, G.; de Kruijf, J.V.; Brisbois, M.C.; Flores, C.C.; Deekshit, P.; Girard, C.; Knieper, C.; Mirnezami, S.J.; Ortega-Reig, M.; Ranjan, P.; et al. Comparative studies of water governance: A systematic review. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araral, E.; Yu, D.J. Comparative water law, policies, and administration in Asia: Evidence from 17 countries. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 5307–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowski, T.; Urbanek, M.; Baláž, P. Structural Economic Assessment of Polymetallic Nodules Mining Project with Updates to Present Market Conditions. Minerals 2021, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachowski, J.; Buczyńska, A. Spatial and Multicriteria Analysis of Dimension Stones and Crushed Rocks Quarrying in the Context of Sustainable Regional Development: Case Study of Lower Silesia (Poland). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł, W.; Baic, I. Extraction, Production and Consumption of Gravel and Sand Aggregates in Poland An Attempt to Assess National and Regional Balances. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 641, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieske, C.; Kozioł, W.; Borcz, A. Eksploatacja kruszyw żwirowo-piaskowych spod wody—Porównanie technologii. Część 1. Przegląd Górniczy 2017, 73, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lipca 2017 r.—Prawo Wodne. Dziennik Ustaw (Journal of Laws), 2017. Dz. U. z 2017 r. poz. 1566. Tytuł Angielski: Water Law Act of 20 July 2017. (Aktualny Tekst Jednolity: Dz. U. z 2025 r. poz. 960). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20170001566 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Robinson, S.P.; Theobald, P.D.; Lepper, P.A.; Hayman, G.; Humphrey, V.F.; Wang, L.S.; Mumford, S. Measurement of Underwater Noise Arising From Marine Aggregate Operations. In The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life; Popper, A.N., Hawkins, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 465–468. [Google Scholar]

- Janson, E. Multi-Decadal Impact of Mine Waters in Przemsza River Basin, Upper Silesian Coal Basin, Southern Poland. Water 2024, 16, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand Mining: How It Impacts the Environment and Solutions; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/09/global-sand-mining-demand-impacting-environment/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Ustawa z Dnia 23 Kwietnia 1964 r.—Kodeks Cywilny. Dziennik Ustaw (Journal of Laws), 1964. Dz. U. z 1964 r. Nr 16, poz. 93. Tytuł Angielski: Civil Code Act of 23 April 1964. (Aktualny Tekst Jednolity: Dz. U. z 2025 r. poz. 1071). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19640160093 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Ustawa z Dnia 21 Sierpnia 1997 r. o Gospodarce Nieruchomościami. Dziennik Ustaw (Journal of Laws), 1997. Dz. U. z 1997 r. Nr 115, poz. 741. Tytuł Angielski: Real Estate Management Act of 21 August 1997. (Aktualny Tekst Jednolity: Dz. U. z 2024 r. poz. 696). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19971150741 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Real Estate Law|Poland|Global Corporate Real Estate Guide|Baker McKenzie Resource Hub. Available online: https://resourcehub.bakermckenzie.com/en/resources/global-corporate-real-estate-guide/europe-middle-east-and-africa/poland/topics/real-estate-law (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Ustawa z Dnia 9 Czerwca 2011 r. Prawo Geologiczne i Górnicze. Dziennik Ustaw (Journal of Laws), 2011. Dz. U. z 2011 r. Nr 163, poz. 981. Tytuł Angielski: Geological and Mining Law Act of 9 June 2011. (Aktualny Tekst Jednolity: Dz. U. z 2024 r. poz. 1290). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20111630981 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Nieć, M. Polska i międzynarodowa ramowa klasyfikacja zasobów (UNFC) złóż kopalin stałych i węglowodorów—Podobieństwa i różnice. Górnictwo Odkryw. 2009, 50, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nieć, M. Międzynarodowe klasyfikacje zasobów złóż kopalin. Górnictwo I Geoinżynieria 2010, 34, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kuan, S.H.; Ghorbani, Y.; Chieng, S. Narrowing the gap between local standards and global best practices in bauxite mining: A case study in Malaysia. Resour. Policy 2020, 66, 101636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufian, A.; Muhamad, N. Issues and Challenges in the Malaysian Land Administration System. In Proceedings of the XXIV FIG International Congress 2010, Facing the Challenges—Building the Capacity, Sydney, Australia, 11–16 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.N.A.; Maimun, N.H.A.; Razali, M.N.M.; Ismail, S. The artificial neural network model (ANN) for Malaysian housing market analysis. Plan. Malays. 2019, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zihannudin, N.Z.; Maimun, N.H.A.; Ibrahim, N.L. Brownfield sites and property market sensitivity. Plan. Malays. 2021, 19, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Estate Law|Malaysia|Global Corporate Real Estate Guide|Baker McKenzie Resource Hub. Available online: https://resourcehub.bakermckenzie.com/en/resources/global-corporate-real-estate-guide/asia-pacific/malaysia/topics/real-estate-law (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Yusof, N.A.; Johar, F.; Sabri, S. Issues and challenges in land development processes in Malaysia. Plan. Malays. 2018, 16, 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.H. Ownership, land use and the development process: The case of Malaysia. J. Southeast Asian Stud. 2014, 45, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.; Ibrahim, M. Regulation of Water Land Use in Malaysia: Legal and Policy Challenges. J. Malays. Environ. Law 2020, 31, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, A.; Lee, S. Legal Gaps in Water Rights and Submerged Land in Malaysia. Environ. Law Rev. 2019, 21, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Rashid, M.; Hassan, F. Revisiting Land Tenure in Coastal and Riverine Areas in Malaysia. Plan. Malays. 2022, 20, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, F.; Zainol, R. Legal Framework of Mining Sector in Malaysia: Challenges and Perspectives. J. Malays. Law 2018, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, A.; Hassan, N.; Yusoff, M. Regulatory Challenges in the Mineral Industry: A Malaysian Perspective. Malays. J. Geosci. 2020, 4, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, S.; Ahmad, M. Legal Aspects of Mineral Ownership in Malaysia: A Review. Malay. Law J. 2017, 8, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mineral Resources of Poland; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2025; p. 202.

- Mazurek, S.; Tymiński, M.; Tymiński, M.; Malon, A.; Malon, A.; Szuflicki, M.; Bońda, R.; Brzeziński, D.; Chmielewski, A.; Czapigo-Czapla, M.; et al. Mineral Resources of Poland; Polish Geological Institute-National Research Institute: Warszawa, Poland, 2022.

- Bilans Zasobów Złóż Kopalin w Polsce wg Stanu na 31 XII [2011–2020 r.], 2012–2021; A Series of Annual Reports on the Balance of Mineral Resources in Poland. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/oferta-inst/wydawnictwa/serie-wydawnicze/bilans-zasobow-kopalin.html (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE). Off. J. Eur. Union 2007, L 108/1, 1–14. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32007L0002 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Gotlib, D. Możliwości Wykorzystania Analitycznych Metod Projektowania Systemów Informatycznych w Tworzeniu baz Danych Przestrzennych Na Przykładzie Topograficznego Systemu Informacyjnego. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Photogrammetry, Teledetection and Spatial Information Systems, Warsaw University of Technology, Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- CBDG Menedżer Pobierania. Available online: https://dm.pgi.gov.pl/ (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Pietkiewicz, P.; Dudek, M.W. Stawki czynszu dzierżawnego za grunty Lasów Państwowych i Wód Polskich w aktualnych warunkach rynkowych. In Kruszywa Mineralne. T. 6; Glapa, W., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2023; pp. 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Ministers. Regulation of the Council of Ministers of December 28, 2017, on the Amounts of Annual Fees for the Use of Land Covered by Water. Journal of Laws 2022, Item 2438, 2017. Polish Title: Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z Dnia 28 Grudnia 2017 r. w Sprawie Wysokości Stawek Opłat Rocznych za użYtkowanie Gruntów Pokrytych Wodami (Dz.U. 2022 poz. 2438). 2017. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20170002496 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Prezes Państwowego Gospodarstwa Wodnego Wody Polskie. Zarządzenie nr 34/2022 z dnia 7 czerwca 2022 r. Państwowe Gospodarstwo Wodne Wody Polskie, 2022. Regulation No. 34/2022 of the President of the State Water Holding Polish Waters of June 7, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/25fb563f-1364-40ee-8d18-5f3b66a56ced (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Minister of Climate and Environment. Announcement of the Minister of Climate and Environment of November 3, 2022, Concerning the Rates for 2023 Under the Provisions of the Geological and Mining Law. Polish Title: Obwieszczenie Ministra Klimatu i Środowiska z dnia 3 Listopada 2022 r. w Sprawie Stawek Opłat na Rok 2023 z Zakresu Przepisów Prawa Geologicznego i Górniczego. 2022. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP20220001080 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Prezes Państwowego Gospodarstwa Wodnego Wody Polskie. Zarządzenie nr 3/2024 z dnia 5 Stycznia 2024 r. Państwowe Gospodarstwo Wodne Wody Polskie, 2024. Regulation No. 3/2024 of the President of the State Water Holding Polish Waters of January 5, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/8bba1f56-c371-4d2a-a893-369698e592ca (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 16 Grudnia 2016 r. o Zasadach ZarząDzania Mieniem PańStwowym. Dz. U. 2024, poz. 125, 2016. Tekst Jednolity; z późn. zm. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20160002259 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- U.S. Geological Survey. Malaysia; Technical Report; U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2024.

- Department of Irrigation and Drainage Malaysia (DID). River Sand Mining Management Guideline; Also Available as a Technical Report from DID; Department of Irrigation and Drainage Malaysia (DID): Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Selangor Water Management Authority (LUAS). State of the River Report 2019; Selangor Water Management Authority: Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2021.

- Malaysian Chamber of Mines (MCOM). Annual Report 2023; Malaysian Chamber of Mines: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment Malaysia. Environmental Quality Act 1974. Laws of Malaysia. 1974. Available online: https://www.doe.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Environmental_Quality_Act_1974_-_ACT_127.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Government of Malaysia. Federal Constitution of Malaysia. Article 74: Legislative Powers; Government of Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1957.

- Sarawak Natural Resources and Environment Ordinance. 1958. Available online: https://lawnet.sarawak.gov.my/lawnet_file/Ordinance/ORD_NRE%20ORD.%20LawNet.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Sarawak Minerals Ordinance. 2004. Available online: https://lawnet.sarawak.gov.my/lawnet_file/Ordinance/ORD_CAP.%2056%20Lawnet.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Pahang Minerals Enactment. 2001. Available online: https://ptg.pahang.gov.my/sumber/pewartaan/70-pewartaan-pindaan-mineral/file (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Bernama. Lynas, Kelantan Ink MoU for Mixed Rare Earths Carbonate Supply. 2025. Available online: https://bernama.com/en/news.php?id=2429250 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Bernama. Kedah Optimistic on New REE Revenue. 2024. Available online: https://www.bernama.com/en/news.php?id=2367710 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Ministry of Natural Resources, Environment and Climate Change (NRECC). National Mineral Industry Transformation Plan 2021–2030; NRECC: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2021.

- Selangor Minerals Enactment. 2000. Available online: https://dewan.selangor.gov.my/enasel/enakmen-mineral-selangor-2000/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).