Abstract

Investigating ecological irrigation risks associated with mine water utilization is of great significance for alleviating water resource shortages in arid mining regions of western China, thereby supporting efficient coal extraction and coordinated ecological development. In this study, a representative mining area in Xinjiang was investigated to reveal the evolution patterns of mine water quality under arid geo-environmental conditions in western China and to systematically assess environmental risks induced by ecological irrigation. Surface water, groundwater, and mine water samples were collected to study ion ratio coefficients, hydrochemical characteristics, and evolution processes. Based on this, a multi-index analysis was employed to evaluate ecological irrigation risks and establish corresponding risk control measures. The results show that the total dissolved solids (TDS) of mine water in the study area are all greater than 1000 mg/L. The evolution of mine water quality is mainly controlled by water–rock interaction and is affected by evaporation and concentration. The main ions Na+, Cl−, Ca2+, and SO42− originate from the dissolution of halite, gypsum, and anorthite. If the mine water is directly used for irrigation without treatment, the soluble sodium content, sodium adsorption ratio, salinity hazard, and magnesium adsorption ratio will exceed the limits, leading to the accumulation of Na+ in the soil, affecting plant photosynthesis, and posing potential threats to the groundwater environment. Given the evolution process of mine water quality and the potential risks of direct use for irrigation, measures can be taken across three aspects: nanofiltration combined with reverse osmosis desalination, adoption of drip irrigation and intermittent irrigation technologies, and selection of drought-tolerant vegetation. These measures can reduce the salt content of mine water, decrease the salt accumulation in the soil layer, and lower the risk of groundwater pollution, thus reducing the environmental risks of ecological irrigation with mine water. The research will provide an important theoretical basis for the scientific utilization and management of mine water resources in arid areas by revealing the evolution law of mine water quality in arid areas and clarifying its ecological irrigation environmental risks.

1. Introduction

With coal resources steadily becoming depleted in the central and eastern parts of China, the coal mining center has rapidly shifted to the ecologically fragile arid areas in the west, where coal reserves account for 70% of the country’s total and play a vital role in energy supply [1,2]. However, due to climatic factors, precipitation is scarce and evaporation is intense, and water resource and ecological environment problems are becoming increasingly serious [3]. Due to the superposition of sedimentation, structure, and man-made mining activities, the mine water produced in the coal mining process often contains a large amount of dust, coal dust suspended solids, and a certain amount of sulfate and heavy metals [4], and direct discharge not only wastes water resources, but also poses a threat to the soil and the surrounding ecological environment. According to statistics, for every 1 ton of raw coal mined, about 2.1 tons of mine water is produced [5]. Therefore, rationally treating and using mine water for ecological irrigation is of great significance in order to alleviate the shortage of water resources and to improve the ecological environment in the arid areas of western China.

The hydrochemical characteristics of mine water are the direct basis for determining whether the use of mine water for ecological irrigation poses risks to soil safety, vegetation growth, and the groundwater environment [6,7]. The main formation role and ion source of mine water quality can be determined by studying the water quality evolution process of mine water [8,9], which can provide a basis and guidance for the prevention and control of mine water ecological irrigation risks. Scholars have carried out a great number of studies on the chemical characteristics and water quality evolution of mine water irrigation [10,11]. The formation and evolution of mine water quality can be divided into three stages: natural equilibrium in the pre-mining period, intensive disturbance during mining, and rebalancing after pit closure [12,13,14]. Affected by coal mining activities, the sulfur-containing minerals in the coal and surrounding rock undergo a series of oxidation reactions to produce acidic substances, such as sulfate, and dissolve a variety of heavy metals, forming acidic mine water containing heavy metals [15]. However, the pH of the mine waters in the western mining area is mostly alkaline, and unlike the mining area in the central and eastern mining areas, the characteristics and evolution process of mine water quality need to be studied.

In terms of the environmental impact of mine water irrigation, the feasibility of coal mine drainage on farmland irrigation and its potential impact on soil performance were examined by analyzing key water quality parameters such as sodium adsorption ratio, electrical conductivity (EC), sodium percentage (Na%) and Kelly’s index (KI) [16,17,18]. This provided theoretical support for mine water ecological irrigation [19]. The formation and evolution of neutral mine water are less affected by coal mining disturbances [20]. However, the pH of the mine waters in the western mining area is mostly alkaline, and unlike the mining area in the central and eastern mining areas, the characteristics and evolution process of mine water quality need to be studied. These studies mainly focused on the analysis of mine water hydrochemistry and ecological irrigation suitability. However, systematic analysis and research on the effects of ecological irrigation of mine water on soil, vegetation, and groundwater are lacking. Therefore, it is essential to systematically study the environmental risks of mine water ecological irrigation based on an understanding of the characteristics and evolution process of mine water in arid areas.

Yushuquan mine is located on the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains, and the northern edge of the Tarim Basin. It is a typical arid climate zone, with scarce rainfall and scarce surface water and groundwater resources. The mine water is a potential water resource for ecological water such as vegetation irrigation. Therefore, we study the hydrochemical characteristics and formation of mine water, and conduct an evaluation of the applicability of mine water for irrigation. This research aims to (1) investigate the hydrochemical characteristics and formation of mine water using mathematical statistics and ionic scale factors, and (2) analyze the impact of mine water irrigation on soil safety, vegetation growth, and the groundwater environment by combining factors such as soluble sodium content (SSP), sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), permeability index (PI), heavy metal pollution index (HPI), and the Nemero index (F).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

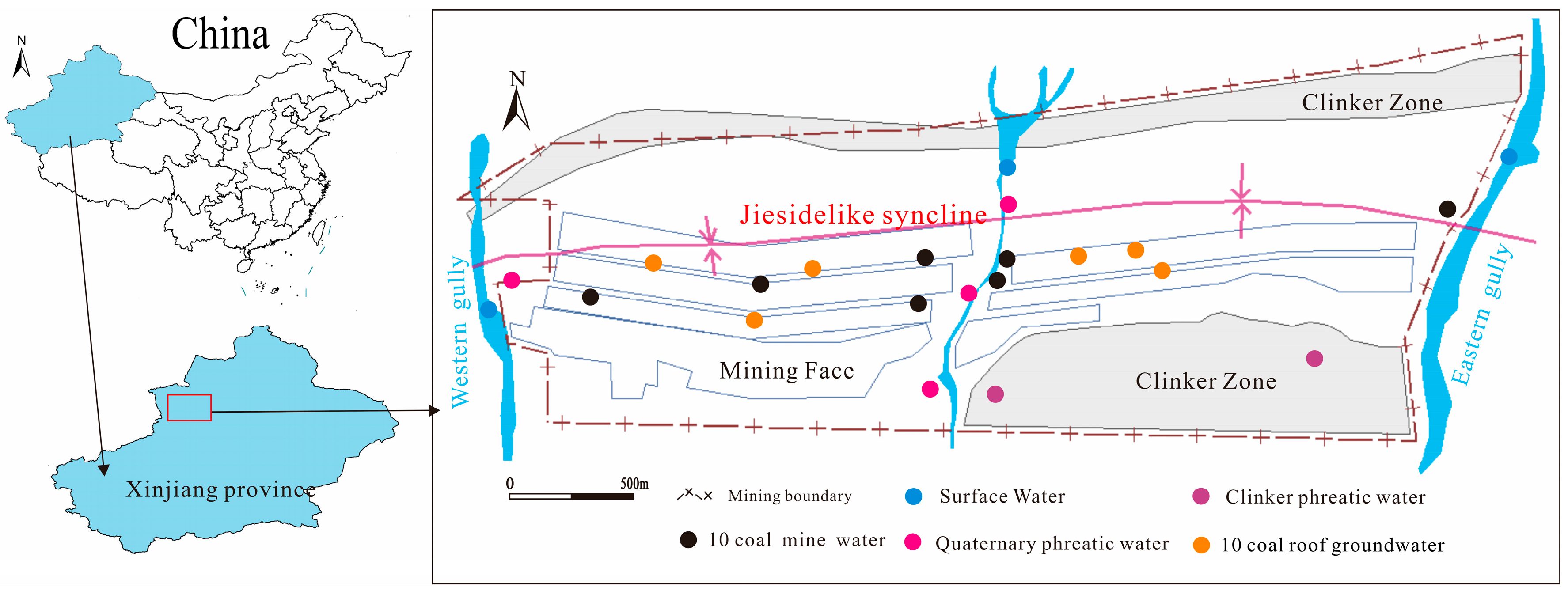

Yushuquan mine is situated at the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains, along the northern boundary of the Tarim Basin. This region experiences a typical temperate continental arid climate, characterized by long periods of drought, limited rainfall, and a fragile ecosystem. The surface bedrock is exposed in the mining area, with relatively flat terrain in the center, and in the south and north the surface is largely covered by red clinker formed by the natural oxidation of the coal seams, where a number of alluvial gullies have developed. The main coal resources are deposited in the tectonic basins in this region, and its hydrogeological structures are mainly affected by folding and faulting tectonics. In addition, the wind-eroded landforms in the region provide favorable conditions for the conversion of surface rainfall into groundwater flow, and the main aquifers include Quaternary pore water and Jurassic fissure water.

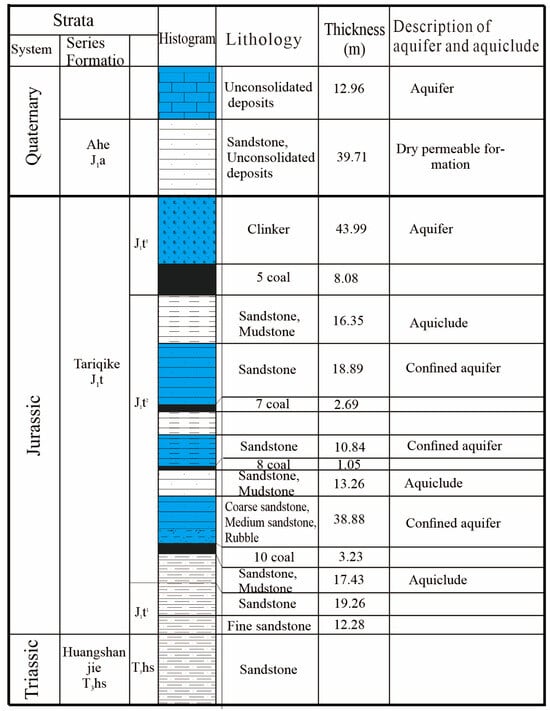

The strata in the mining area include Triassic Huangshanjie Formation (T3hs), Jurassic Tariqike Formation (J1t), Jurassic Ahe Formation (J1a), and Quaternary (Q), from oldest to newest (Figure 1). Based on the water content and water-resisting property of these strata, the sequence can be divided into five aquifers, one permeable stratum and four aquicludes. There are 13 coal seams in the well field, which are mainly distributed in the Tarichik Formation, of which there are four recoverable coal seams with stable conditions, including no.5 coal, no.7 coal, no.8 coal and no.10 coal. Currently, the mine water of the no.10 major minable seams mainly comes from direct water-filled water sources (no.10 coal roof confined aquifer) and indirect water-filled water sources (clinker phreatic aquifer and the Quaternary phreatic aquifer).

Figure 1.

Comprehensive hydrogeological column map of the study area.

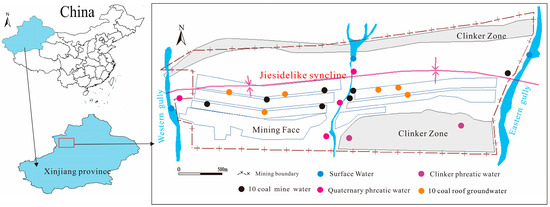

2.2. Sample Collection and Analysis

To investigate the water quality evolution process of mine water and to quantitatively evaluate the environmental risks of using mine water for ecological irrigation, a total of 23 water samples were collected from different water-filled water sources in the mine, different locations within the underground coal mine, and surface gullies. The sampling included three surface water samples collected from the western and eastern alluvial gullies. Six quaternary groundwater samples, two clinker phreatic water samples, and six samples of no.10 coal roof groundwater were collected during the hydrogeological exploration phase (Figure 2). Six mine water samples were collected from different locations in the no.10 coal seam underground mine at a depth of 208 m. Mine water sampling points include the coal mining face, the return airway of the mine, and the central water tank. Prior to water sampling, in situ measurements of pH and total dissolved solids (TDS) were conducted using a portable multi-parameter monitoring device (YSI, Yellow Springs, OH, USA; HACH, Loveland, CO, USA) with a precision of ±0.2 (pH) and ±1% (TDS), respectively. Then, the sampling bottles were flushed 2~3 times with the water to be sampled, and the water samples were sealed, labeled and transported to the laboratory for testing. The concentrations of cations, including K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, were tested using ICP-AES (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA); Concentrations of major anions F−, Cl−, NO3−, and SO42− were determined with ion chromatography (ICS2000, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The concentration of HCO3− was determined through chemical titration. Each water sample was tested three times and averaged, and the standard deviation was controlled within 10%. The ionic charge imbalance between the main cations and anions was less than 5%. The concentrations of heavy metals, including FeMn, Cu, Zn, Hg, As, Cd, and Pb were tested using ICP-AES (Thermo), with detection accuracies of 5%. Cr6+ was measured as chromate according to a modified version of U.S. EPA Method 218.6.38.46. This method is based on anion exchange chromatography using a Thermo Scientific Dionex IonPac AS7 (Thermo, Massachusetts, USA) column at Duke University with a method detection limit (MDL) for chromate of 0.004 μg/L and a reporting limit of 0.012 μg/L.

Figure 2.

Distribution of sampling points.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hydrochemistry of Mine Water

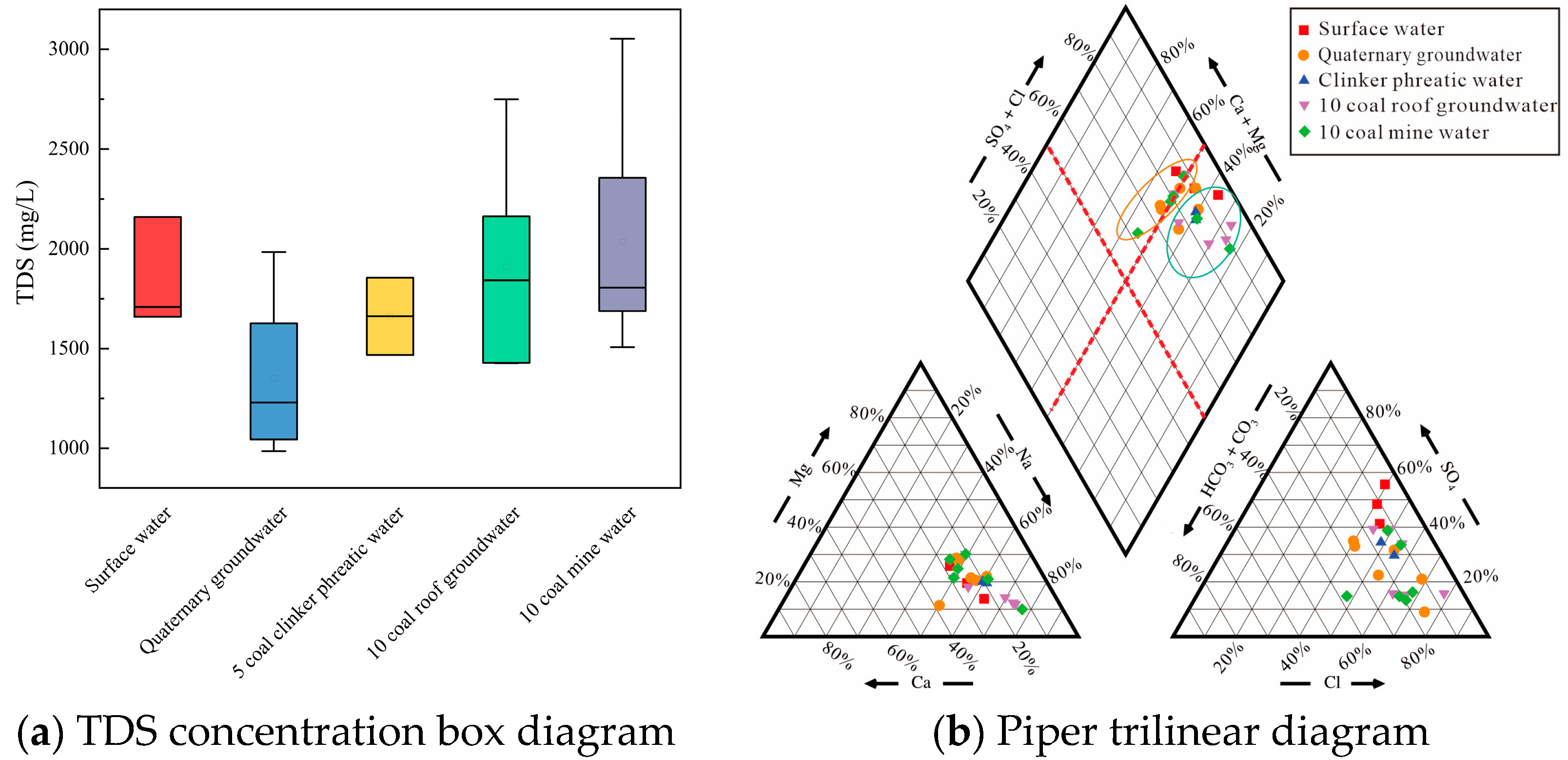

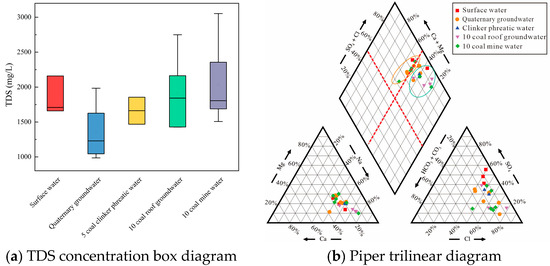

Analyzing the chemical characteristics of mine water and its water-filled water sources is the premise for studying the evolution of mine water quality, and it is also the basis for understanding the environmental risks caused by ecological irrigation of mine water. Detection of the concentrations of routine ions and physicochemical indicators in different types of water samples from the Yushuquan mine and the statistical analysis results are shown in Table 1. Waters of different types in the Yushuquan mine are characterized by an average pH value of 7.78, classified as weakly alkaline. Their TDS ranged from 985.42 to 3051.66 mg/L, with most values exceeding 1000 mg/L, classifying the water as high mineralization. In addition, the TDS variation ranges for surface water, Quaternary groundwater, clinker phreatic water, and the no.10 coal roof groundwater were 1658.43–2158.77, 985.42–1984.22, 1468.09–1854.34, and 1428.27–2748.88 mg/L, respectively. The TDS variation range for mine water was 1507.27–3051.66 mg/L, which is significantly higher than that of surface water and groundwater (Figure 3a). The overall increase in the TDS of mine water is due to the influence of mining activities, water-conducting fissure zones communicating different aquifers, and enhancing groundwater mixing, and superimposes the secondary water–rock effect in the goaf [21]. The major anions in the water samples were Cl− and SO42− and the cations were predominantly Na+ and Ca2+. The coefficient of variation for surface water, Quaternary groundwater, clinker phreatic water, confined water from the no.10 coal seam roof, and mine water from the no.10 coal seam is all less than 1, indicating that the spatial variability of each indicator within the same water sample type is relatively small.

Table 1.

Results of conventional ion detection of study area.

Figure 3.

TDS concentration box diagram and Piper trilinear diagram, (a) TDS concentration box diagram, (b) Piper trilinear diagram.

Based on the results of the ion concentration detection, a Piper trilinear diagram (Figure 3b) was plotted to analyze the water chemistry types and major ion compositions of surface water, groundwater, and mine water in the Yushuquan mine [22]. According to the piper plots, in the anion triangle, each type of water samples is close to SO42− and Cl− terminal elements, and the anion is mainly dominated by SO42− or Cl−. In the cation triangle, the distribution of different types of water samples is close to the Na+ terminal element, with a small portion close to the Ca2+ terminal element. The main hydrochemical types of water samples in the Yushuquan mine are Cl-Na and SO4-Ca. The basic water chemistry characteristics of the no.10 coal mine water are most similar to the no.10 coal roof groundwater, suggesting that the direct source of the no.10 coal mine water is the no.10 coal roof groundwater.

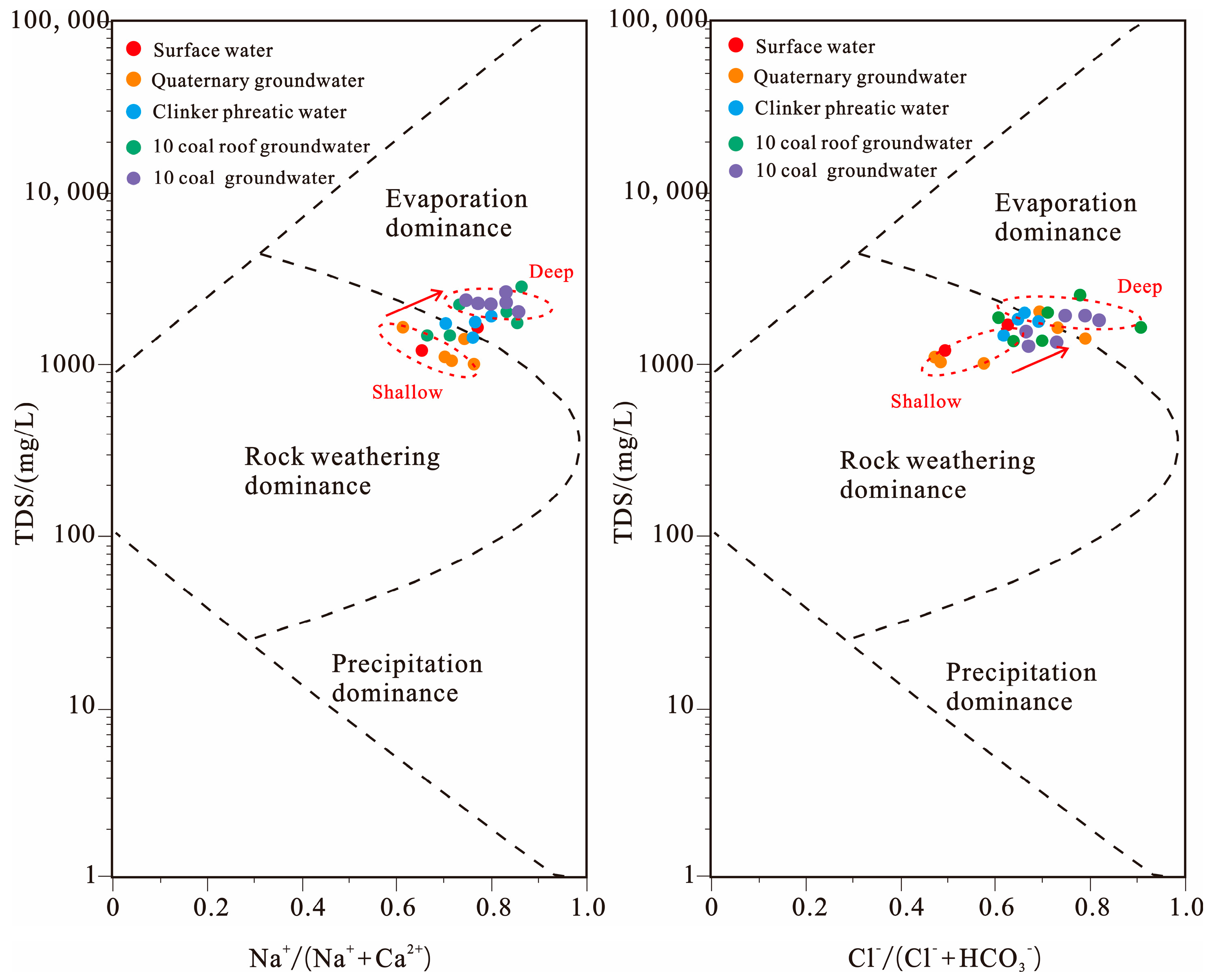

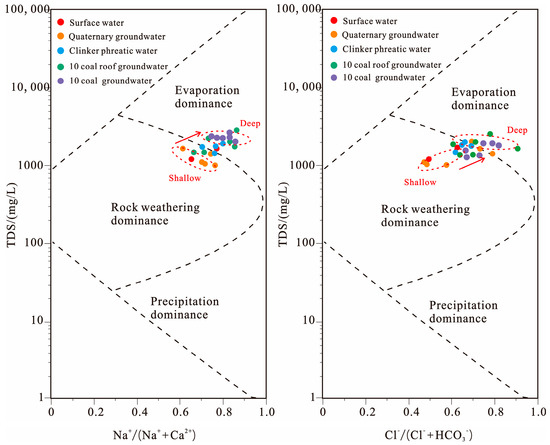

3.2. Hydrogeochemical Evolution of Mine Water

The Gibbs diagram can reveal the controlling factors of major ion evolution in surface water and phreatic water by using the relationship between the ion concentration ratio Na+/(Na+ + Ca2+) and TDS [23]. The hydrochemistry mechanisms can be classified into three types: evaporation, encompassing water–rock interaction, and atmospheric precipitation. In recent years, more and more scholars have used the Gibbs diagram to study the evolution process of major ions in surface water and groundwater. The Gibbs map of surface water, groundwater, and mine water in the Yushuquan mine is shown in Figure 4. The TDS of water samples from the Yushuquan mine are greater than 1000 mg/L, with Na+/(Na+ + Ca2+) values from 0.55 to 0.95, and Cl−/(Cl− + HCO3−) from 0.45 to 0.95. Different types of water samples all fall within the scope of rock weathering and evaporation concentration, indicating that rock weathering and evaporation concentration is the controlling mechanism of the evolution of groundwater and mine water. In addition, the confined groundwater of the no.10 coal seam roof is close to the no.10 coal mine water in the Gibbs diagram, which further proves that the main source of mine water in the evolution of mine water is the no.10 coal roof groundwater.

Figure 4.

Gibbs chart of water samples from study area.

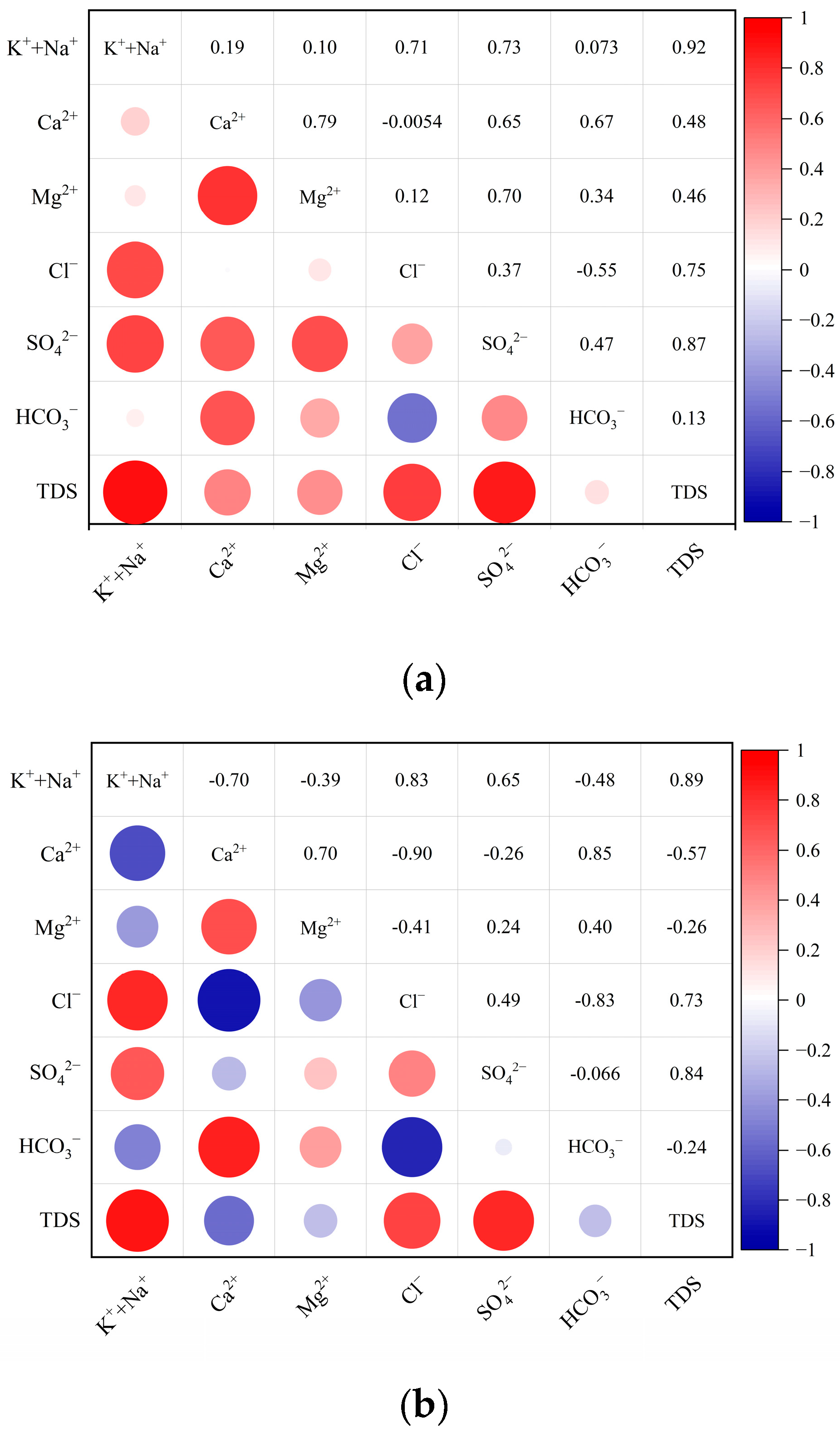

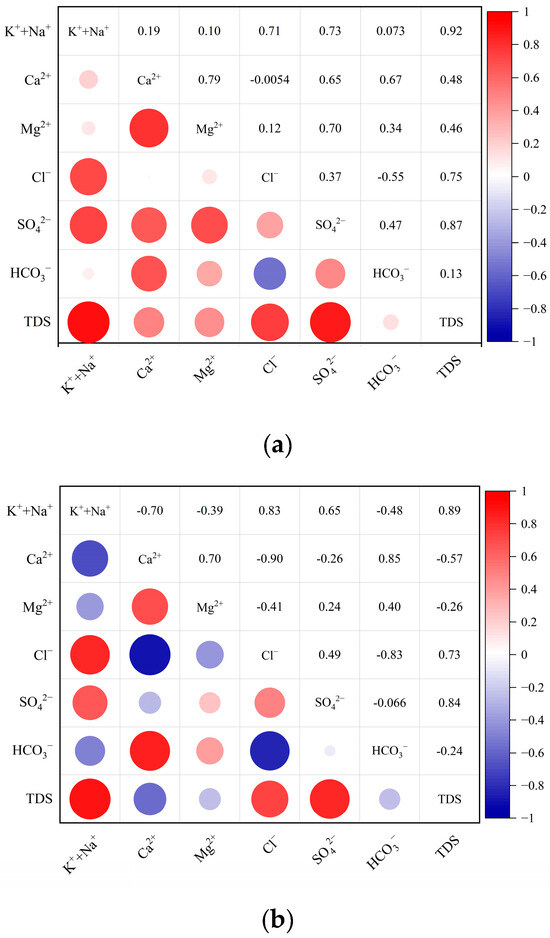

From the water general chemistry, it can be observed that the TDS of no.10 coal roof groundwater and no.10 coal mine water is greater than 1000 mg/L. The hydrochemical parameter correlation diagram between no.10 coal roof groundwater and major ions in no.10 coal mine water further reveals the evolution of mine water and the sources of major ions (Figure 5). The hydrochemical parameter correlation diagram illustrates that the TDS concentrations exhibited strong correlations with Na+ (R = 0.92), SO42− (R = 0.87), Cl− (R = 0.75), and Ca2+ (R = 0.48), indicating that the contribution to the mine water TDS is, in descending order, from Na+, SO42−, Cl−, and Ca2+. The ionic correlation of the mine water was similar to that of the no.10 coal roof groundwater, as the no.10 coal roof groundwater is the direct filling source of the mine water, and the correlation coefficients of TDS with Na+, SO42−, and Cl− were 0.89, 0.84, and 0.73, respectively. Furthermore, it can be seen from the correlation analysis diagram of each ion in mine water that the correlation between Na+ and Cl−, and Ca2+ and SO42− are high, and the correlation coefficient is greater than 0.5, indicating that Na and Cl−, Ca2+ and SO42− have a similar or the same source.

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis diagram of no.10 coal roof groundwater and no.10 coal mine water. (a) Correlation analysis diagram of no.10 coal roof groundwater; (b) Correlation analysis diagram of no.10 coal mine water.

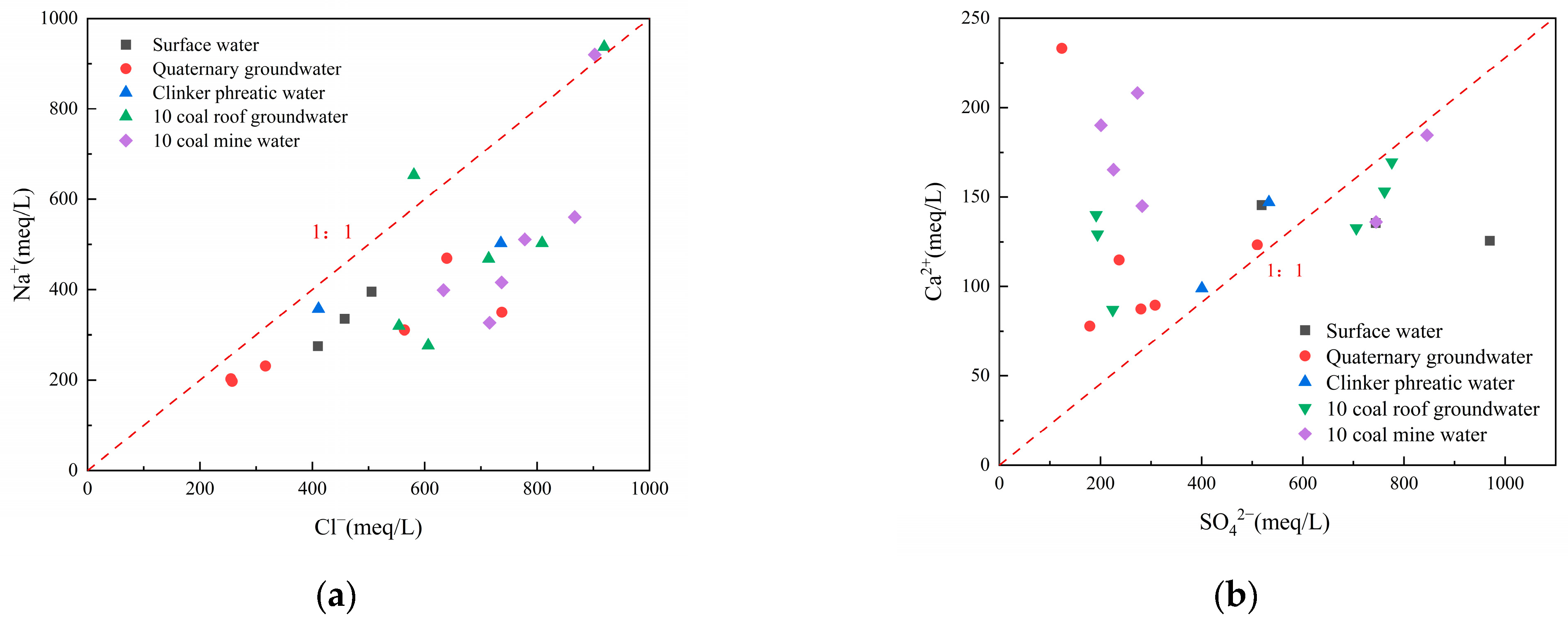

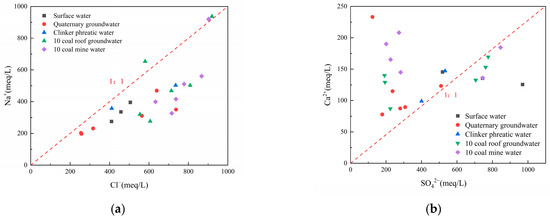

The relationship between Na+ and Cl− (Figure 6a) and the relationship between Ca2+ and SO42− (Figure 6b) can be further analyzed for sources of major ions. The concentrations of Na+, K+, and Cl− in groundwater are generally relatively stable, so the ratio of γ(Na+)/γ(Cl−) (γ means concentration of ions) can be used to identify the sources of Na+ and Cl− in groundwater. When the ratio of γ(Na+)/γ(Cl−) is near 1, it indicates that the dissolution of rock salt minerals is occurring; when the ratio of γ(Na+)/γ(Cl−) is greater than 1, it suggests that the dissolution of silicate minerals is taking place. The no.10 coal roof groundwater and mine water are mainly distributed below the ratio line of γ(Na+)/γ(Cl−), indicating that for Na+ and Cl−, in addition to the dissolution of rock salt, there was also a reverse cation adsorption process taking place.

Figure 6.

Main ion relationship diagram of mine water, (a) Na+ vs. Cl− ion relationship diagram, (b) Ca2+ vs. SO42− ion relationship diagram.

If the ratio of γ(Ca2+)/γ(SO42−) is 1, this indicates that Ca2+ and SO42− only originate from the dissolution of gypsum, without involvement of any other reactions (Figure 6b). The mine water samples are mainly distributed in the upper-left region of the 1:1 line, indicating that there are other sources of Ca2+, such as the dissolution of carbonate rocks or silicate rocks. Meanwhile, the correlation coefficient between Ca2+ and HCO3− is 0.85, suggesting that Ca2+ not only originates from the dissolution of sulfate rocks (gypsum) but also from the dissolution of calcium feldspar:

3.3. Ecological Irrigation Risk Evaluation

From the analysis of the water quality evolution of mine water, it can be observed that its initial sources are mainly atmospheric precipitation and surface water, while being influenced by multiple factors, including original geological deposition characteristics, water–rock interactions, and disturbances caused by coal mining activities. From multiple perspectives, the environmental risks of mine water ecological irrigation are quantitatively characterized and discussed, including the impact of untreated mine water for ecological irrigation on soil safety, plant growth safety, and groundwater safety.

3.3.1. Risks to Soil Safety Induced by Mine Water Ecological Irrigation

As an unconventional water resource for irrigation, the soil safety risks caused by mine water are quantified using four indicators: soluble sodium percentage, sodium adsorption ratio, residual sodium carbonate, and alkalinity hazard and permeability index. These indicators help characterize the soil salinization and permeability issues caused by mine water. Alkalinity hazard and permeability index.

- (1)

- Soluble Sodium Percentage (SSP)

Na+ in water can exchange with Ca2+ and Mg2+ on clay particles, thereby hindering the movement of soil moisture [24]. When the Na+ concentration in mine water is high and the > 60%, as demonstrated by the red line in the figure, this water source is not suitable for irrigation [25]. The formula of SSP is as follows:

where the concentrations of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ are all measured in meq/L.

- (2)

- Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR)

The sodium adsorption ratio () indicates the relative activity of Na+ in soil exchange reactions and is used to assess the degree of soil alkalization caused by irrigation water [26]. According to the standard requirements of “Urban Sewage Reuse for Green Space Irrigation Water Quality”, the degree of soil alkalization, ≤ 9, will not cause soil alkalization [27]. The formula of SAR is as follows:

where the concentrations of Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ are all measured in meq/L.

- (3)

- Residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC)

Residual sodium carbonate () is one of the key indicators to identify the degree of alkalinity damage of irrigation water on soil. When RSC exceeds 2.5 mmol/L, the water source is not suitable for irrigation. Conversely, when is less than 1.25 mmol/L, the water source is suitable for irrigation [28,29].

- (4)

- Permeability Index (PI)

The permeability index () is used to assess the impact of water on soil permeability. It will not affect the soil’s permeability if the PI > 70%. However, it will impact the soil’s permeability if the < 25% [30]. The formula is as follows:

where the concentrations of Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and are all measured in meq/L.

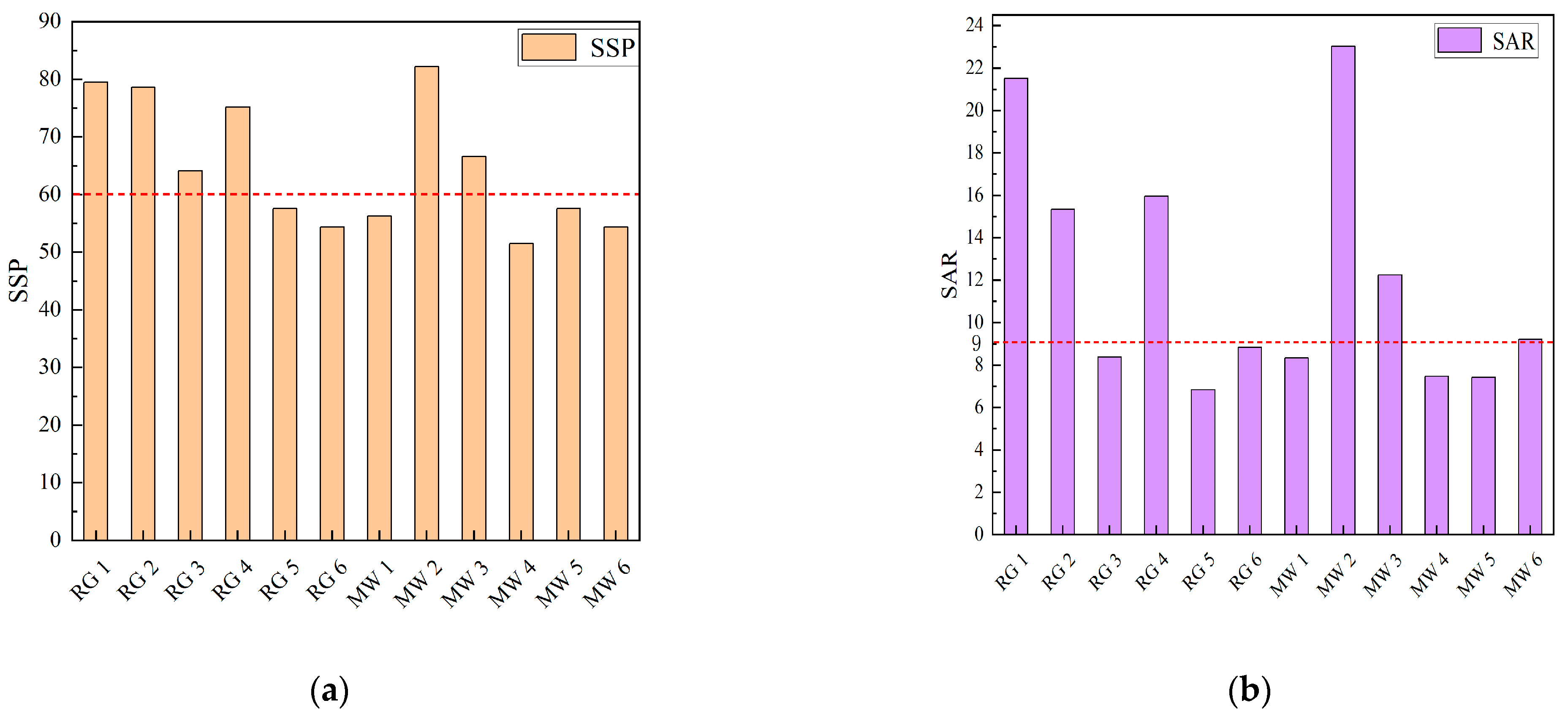

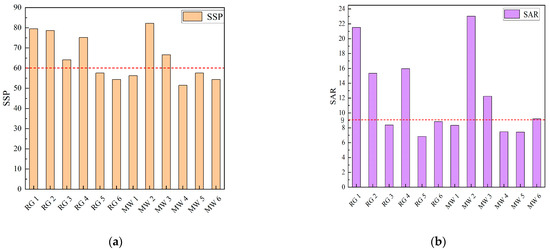

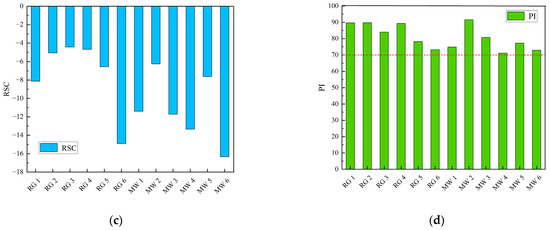

The soluble sodium percentage (SSP), sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), residual sodium carbonate (RSC), and permeability index (PI) for the no.10 coal roof groundwater and the no.10 coal mine water were calculated, respectively (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Soil safety risk assessment map. (a) Soluble sodium percentage (SSP) bar chart; (b) Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) bar chart; (c) Residual sodium carbonate (RSC) bar chart; (d) permeability index (PI) bar chart.

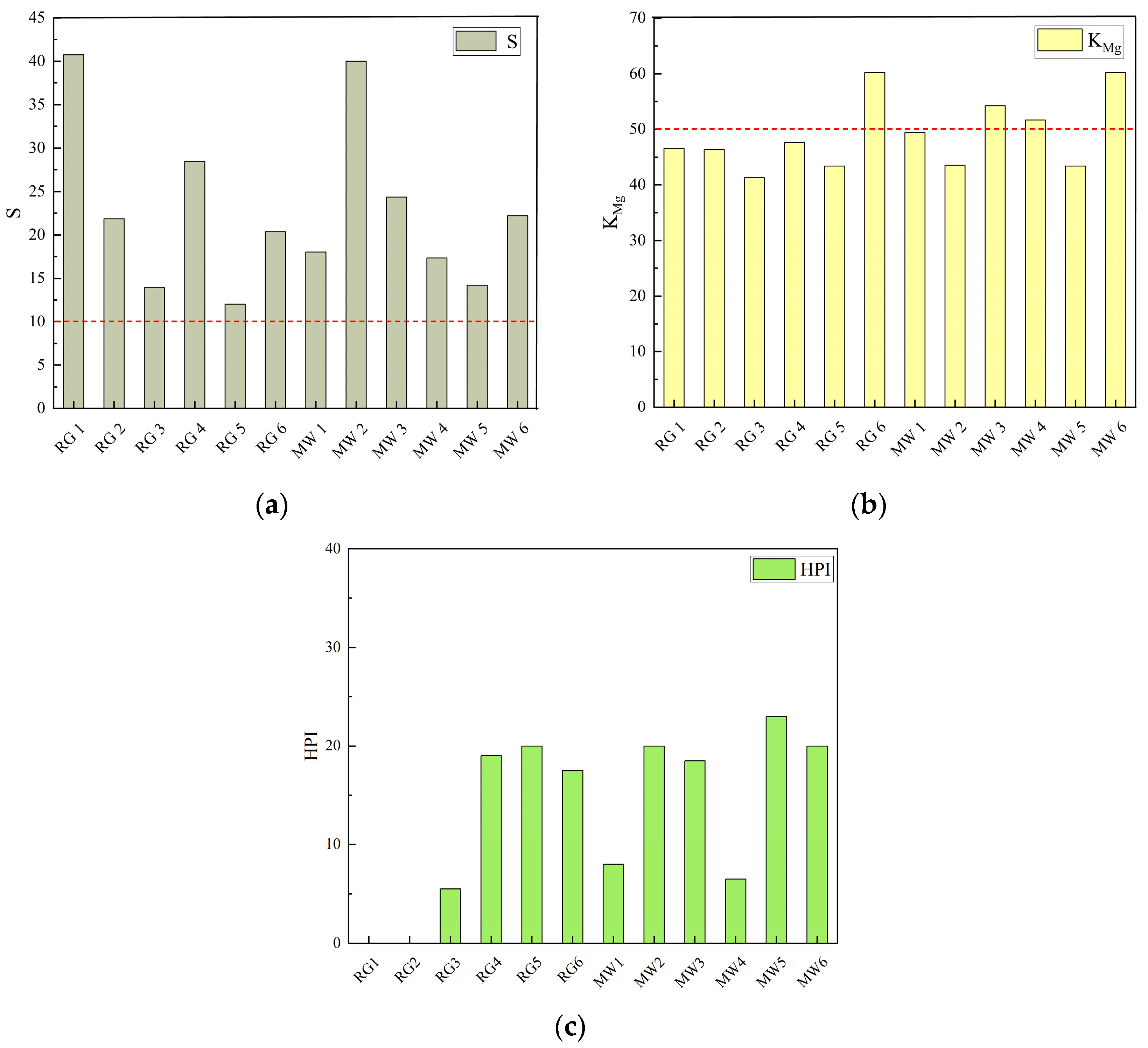

Among the 12 mine water samples, six samples had an SSP greater than 60%, with an exceedance rate of 50%; five samples had an SAR greater than 9, with an exceedance rate of 41.67%; all 12 samples had RSC values less than 0, with no exceedance; and all 12 mine water samples had a PI greater than 70%, which will not affect the permeability of the soil.

In the comprehensive analysis, the residual sodium carbonate and soil permeability index in the soil meet the standards, and the SSP and SAR appeared to be exceeded. This caused the accumulation of Na+ in the soil, and long-term accumulation would induce soil salinization when directly irrigating with untreated mine water.

3.3.2. Risks to Plant Growth Induced by Mine Water Ecological Irrigation

As an unconventional water resource for irrigation, three indicators (salinity hazard, magnesium adsorption ratio, and heavy metal pollution index) are used to quantitatively characterize the safety risks to plant growth caused by mine water.

- (1)

- Salinity Hazard (S)

Salinity hazard () indicates the maximum amount of Cl− and SO42− salts that may occur in the water. Most plant seedlings will be inhibited when > 10 mmol/L [31]. The formula is as follows:

where the concentrations of Na+, Cl−, and SO42− are all measured in meq/L.

- (2)

- Magnesium Adsorption Ratio (KMg)

The magnesium adsorption ratio (MAR) represents the amount of magnesium adsorbed by the soil, which is toxic to plants when > 50% [32]. The formula is as follows:

where the concentrations of Mg2+, and Ca2+ are all measured in meq/L.

- (3)

- Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI)

The total amount of heavy metals in water reflects the toxicity to plants, indicating that the level of heavy metal contamination in the water body has exceeded the maximum level tolerated by plants [33], when the > 100 [34]. The formula is as follows:

where : is the weight of the heavy metal indicator, is the constant of proportionality, taken as 1; is the quality grade index of the heavy metal indicator; is the actual concentration of heavy metals in the water (mg/L); is the maximum limit value of the heavy metal indicator; and is the ideal value of the heavy metal indicator. and are selected from the Class III groundwater limits in the “Groundwater Quality Standards” [35], which are applicable to agricultural water and centralized drinking water (mg/L). The Class III groundwater standard specifies the following limit values for Cu, Hg, As, Cd, and Pb: 1 mg/L, 0.001 mg/L, 0.01 mg/L, 0.005 mg/L, and 0.01 mg/L, respectively.

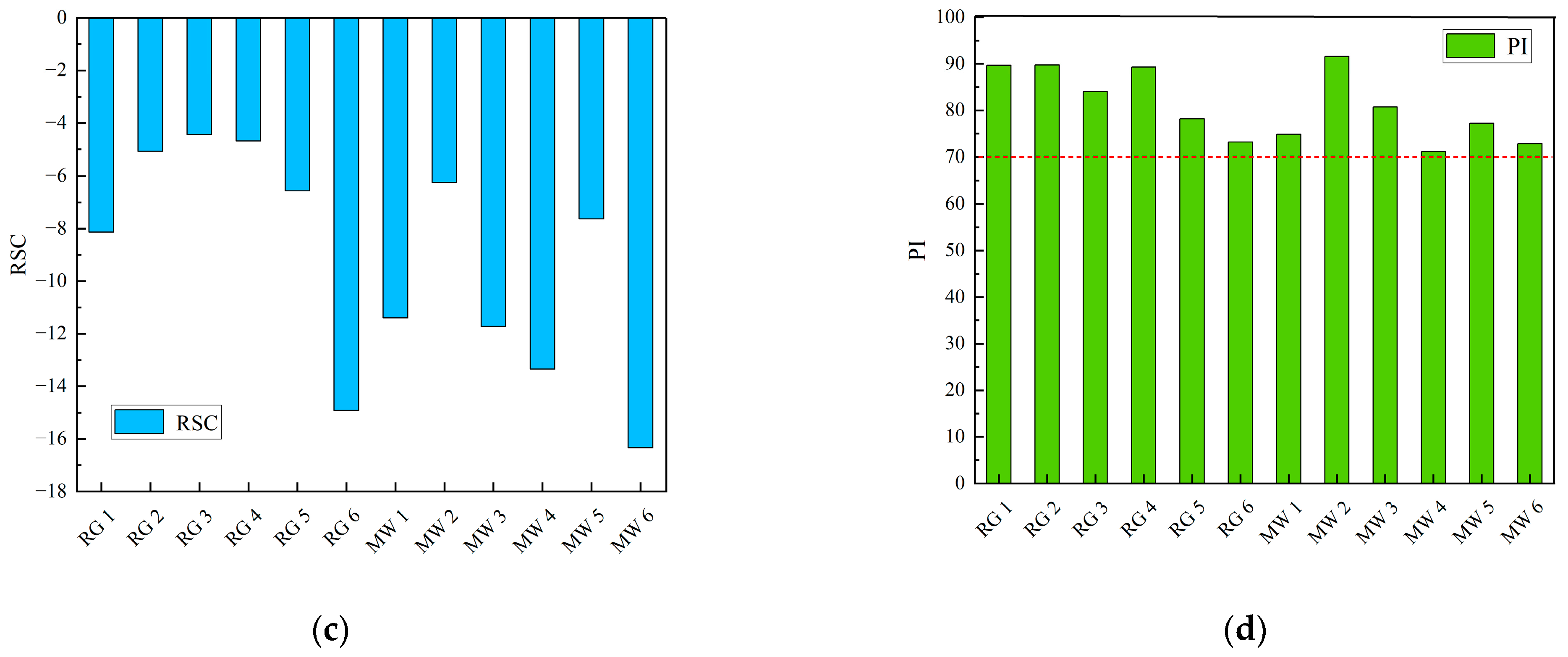

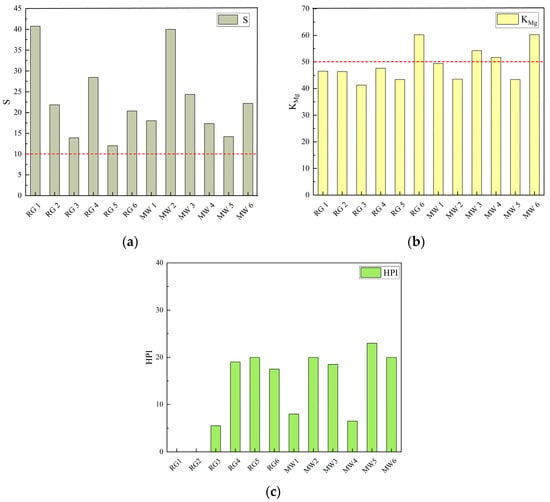

The salinity hazard (), magnesium adsorption ratio (), and heavy metal pollution index () for the no.10 coal roof groundwater and the no.10 coal mine water were calculated, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Plant growth risk assessment map. (a) Salinity hazard bar chart; (b) Magnesium adsorption ratio bar chart; (c) HPI bar chart.

The salinity hazard (S) of the water sample is greater than 10, which can easily cause disturbances in plant growth, and the high content of sulphate and chloride ions inhibited a number of physiological processes in the plant, resulting in yellowing and wilting of the leaves, slow growth, or cessation of growth [36]. Furthermore, four samples of the 12 mine water samples exceeded the magnesium adsorption ratio, which would result in increased magnesium levels in the soil leading to symptoms of burns or necrosis in plant leaves. The heavy metal indexes of Cu, Zn, Hg, As, Cd, Cr6+, and Pb in the 12 mine water samples were all below the detection limit, and only Fe and Mn were detected. Meanwhile, their HPI value ranged from 5.5 to 23, which is far lower than the critical value of 100, and the accumulation of heavy metals does not pose a threat to plants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI) Evaluation Index Test Results (mg/L).

3.3.3. Potential Risks to the Groundwater Induced by Mine Water Ecological Irrigation

As an unconventional water resource for irrigation, groundwater quality standards are used to quantitatively characterize the potential risks to the groundwater environment caused by mine water. The Nemerow Index is calculated based on the individual pollution indices of water samples to obtain a comprehensive score. It takes into account both the average and maximum values of the pollution indices for each detected parameter, with a focus on the impact and influence of the largest pollution items on the quality of the water environment. The formula is as follows:

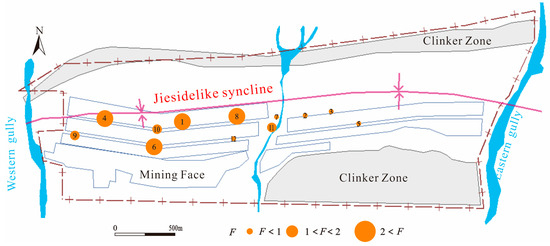

where is the Nemerow index; is the arithmetic mean of all individual pollution indices; is the maximum value among all individual pollution indices.

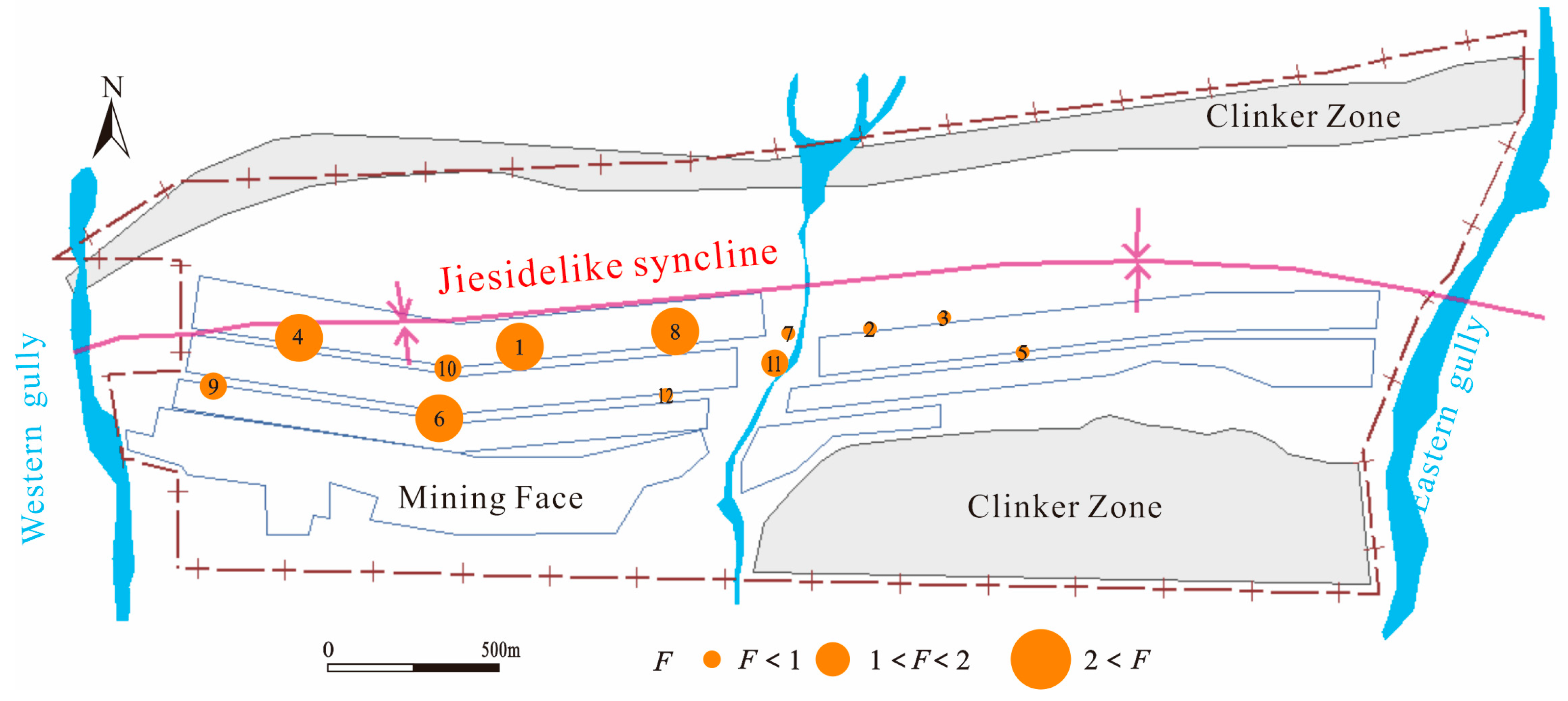

The Nemerow index determines the degree of mine water pollution and thus the potential impact on groundwater. When F < 1, the water quality is clean; 1 ≤ F ≤ 2, mildly polluted; 2 < F ≤ 3, polluted; 3 < F ≤ 5, heavily polluted; F > 5, severely polluted. Among the 12 mine water samples, four samples have F values greater than 2, indicating mild pollution, while eight samples have F values less than 1, indicating clean water quality (Figure 9). In summary, the direct irrigation of untreated mine water poses a slight potential threat to the groundwater environment.

Figure 9.

Distribution map of mine water Nemerow index.

3.4. Management and Preventive Measures for Using Mine Water

Risk prevention and control measures for ecological irrigation with mine water should be taken from three aspects: mine water treatment, irrigation technology, and vegetation selection. These measures are aimed at addressing the high salinity characteristics, evolutionary process, and environmental risks caused by direct irrigation of mine water in the arid regions of the western area.

In terms of mine water treatment, the high levels of TDS and major ions (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, SO42−) in mine water can cause soil salinization when directly irrigated. This not only threatens soil safety and affects the growth of plants but is also a potential threat to the groundwater environment. Therefore, desalination treatment of mine water is necessary. It is recommended to choose a combination of nanofiltration and reverse osmosis processes. The nanofiltration process can be used as the primary treatment stage to effectively remove sulfate ions from the mine water, reducing the load on the reverse osmosis membrane. The reverse osmosis process can further desalinate the water, removing sodium ions, and ultimately ensuring that the water quality meets the requirements for ecological irrigation.

In terms of irrigation technology, drip irrigation and micro-sprinkler irrigation systems can be used to deliver mine water directly to the plant roots, reducing water evaporation and salt accumulation on the soil surface. Furthermore, the use of mine water and groundwater intermittent irrigation techniques allows sufficient time for the soil to absorb and discharge excess salts through phased irrigation. The cyclical irrigation of mine water and groundwater provides sufficient buffer time for the soil to reduce the salt concentration in the surface soil, reducing damage to plants and potential harm to groundwater.

In terms of the selection of salt-tolerant vegetation, salt-tolerant and drought-tolerant vegetation can be selected for planting, such as Salicornia europaea and Carex scabrifolia, etc., according to the special climate of arid areas and the water quality characteristics of mine water. Their salt tolerance thresholds are 29,250 mg/L and 20,475 mg/L, respectively, which are 29.25 and 20.475 times higher than that of common plants (threshold 1000 mg/L). As a result, these plants can effectively absorb and stabilize the salts in the soil. In addition, soil structure can be improved through mixed cropping and crop rotation, reducing salt accumulation and increasing overall ecological stability and productivity.

4. Conclusions

In the Yushuquan mine, the mine water primarily originates from the coal roof groundwater, with an average pH value of 8.46, indicating weak alkalinity. The total dissolved solids (TDS) are greater than 1000 mg/L, with the main cations being Na+ and Ca2+, and the main anions being SO42− and Cl−. The evolution of the mine water quality is primarily influenced by water–rock interactions and evaporation concentration processes. The Na+ and Cl− in the mine water mainly come from the dissolution of salt rocks, while Ca2+ and SO42− primarily originate from the dissolution of minerals such as gypsum and anhydrite.

The comprehensive evaluation of the untreated mine water indicates some pollution, and its direct use for ecological irrigation threatens the groundwater environment. The soluble sodium content (SSP) and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) of the mine water exceed the recommended limits, leading to the accumulation of Na+ in the soil and inducing soil salinization and alkalization in the long term. At the same time, the salinity hazard (S) and magnesium adsorption ratio (KMg) exceed the recommended limits, which can negatively impact plant photosynthesis and threaten plant growth. In this regard, the three methods of desalination of mine water, improvement of irrigation technology, and selection of salt-tolerant plants should be adopted to reduce the TDS of mine water, reduce the accumulation of soil salts, and select drought- and salt-tolerant vegetation, thus reducing the environmental risks of mine water ecological irrigation in arid areas.

Author Contributions

H.W.: Writing—original draft, Data curation, Funding acquisition. H.S.: Water sampling and, Formal analysis. T.W.: Writing—review & editing. J.X.: Writing—review & editing, Methodology. X.W.: Writing—review & editing. Z.Z.: Data collection and, Formal analysis. Q.W.: Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financially supported by the Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi (2025JC-JCQN-012, 2024RS-CXTD-44, 2025ZC-KJXX-138) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3012105). The authors gratefully acknowledge the peer reviewers and editors for their valuable comments.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hao Wang, Hongbo Shang, Tiantian Wang, Jiankun Xue, Xiaodong Wang, Zhenfang Zhou and Qiangmin Wang were employed by Xi’an Research Institute of China Coal Technology & Engineering (Group). All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Conflicts of Interest Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Zhang, D.S.; Li, W.P.; Lai, X.P.; Fan, G.W.; Liu, W.Q. Development on the basic theory of water protection during coal mining in northwest of China. J. China Coal Soc. 2017, 42, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.M.; Shen, Y.J.; Sun, Q.; Hou, E.K. Scientific issues of coal detraction mining geological assurance and their technology expectations in ecologically fragile mining areas of Western China. J. Min. Strat. Control Eng. 2020, 2, 043531. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.M.; Ma, X.D.; Ji, R.J. Progress in engineering practice of water-preserved coal mining inwestern eco-environment frangible area. J. China Coal Soc. 2015, 40, 1711–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, T.T.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J. Removal law of typical pollution components during underground storage of mine water: Taking Mindong No.1 Mine Inner Mongolia as an example. J. China Coal Soc. 2020, 45, 2918–2925. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D.Z.; Li, J.F.; Cao, Z.G.; Wu, B.Y.; Jiang, B.Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y. Technology and engineering development strategy of water protection and utilization of coal mine in China. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 3079–3089. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.N. Spatial distribution characteristics of suita-bility of mine water for irrigation in the Shendong mining area. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 9, 561–572. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, P.; Power, C. Assessing the long-term evolution of mine water quality in abandoned underground mine workings using first-flush based models. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 846, 157390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.W.; Chen, Y.F.; Ge, R.T.; Ma, L.; Zhou, K.D.; Shi, X.P. Discrimination of water-inrush source and evolution analysis of hydrochemical environment under mining in Renlou coal mine, Anhui Province, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.W.; Xie, W.P.; Feng, X.Q.; Zhang, N.; Yin, X. Formation of hydrochemical composition and spatio-temporal evolution mechanism under mining-induced disturbance in the Linhuan coal-mining district. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H.R.; Song, X.M.; Lin, M.L. Water-inrush mechanism research mining above karst confined aquifer and applications in North China coalmines. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Xu, F.; Xue, J.; Li, G. Occurrence, Main Source and Health Risks of Fluorine in Mine Water. Expo Health 2025, 17, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.M.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, L. Mutifield action mechanism and research progress of coal mine water quality formation and evolution. J. China Coal Soc. 2022, 47, 423–437. [Google Scholar]

- Roisenberg, C.; Loubet, M.; Formoso, M.L.; Berger, G.; Munoz, M.; Dani, N. Tracing the Origin and Evolution of Geochemical Characteristics of Waters from the Candiota Coal Mine Area (Southern Brazil): Part I. Mine Water Environ. 2016, 35, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Cui, B.Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Zhang, S.; Feng, G.; Zhang, Z. Evolution Law of Shallow Water in Multi-Face Mining Based on Partition Characteristics of Catastrophe Theory. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Hallberg, K.B. Acid mine drainage remediation options: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 338, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarseh, M.; Imreizeeq, E.; Tilev, S.; Al Alaween, M.; Suleiman, W.; Al Remeithi, A.M.; Al Tamimi, M.K.; Al Alawneh, M. Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation in the arid regions using irrigation water quality index (IWQI) and GIS-Zoning maps: Case study from Abu Dhabi Emirate, UAE. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 14, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Karakuş, C.B. Estimation of irrigation water quality index with development of an optimum model: A case study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 4771–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.F.; Wu, P.; Zhang, R.X.; Li, X.X.; Cha, X.F. Water quality characteristics and irrigation suitability evaluation under the influence of coal mine drainage–a case study of the river watershed in Zhijin, Guizhou. Water Sav. Irrig. 2016, 11, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, S.H.; Wang, H.L. Risk assessment and control of farmland irrigation with coal mine water. Coal Econ. Res. 2021, 41, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Gui, H.R. Hydrogeochemical characteristics of groundwater in the limestone aquifers of the Taiyuan Group and its geological significance in the Suxian mining area. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2016, 43, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.T.; Yang, J.; Jin, D.W.; Li, G.; Zhou, Z.; Xue, J.; Shang, H. The hydrogeochemical characteristics and formation mechanism of high-fluoride mine water. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, A.M. A graphical procedure in the geochemical interpretation of wateranalysis. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1944, 25, 914–928. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, R.J. Mechanisms controlling world water chemistry. Science 1970, 170, 795–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbazhagan, S.; Jothibasu, A. Modeling water quality index to assess shallow groundwater quality for sustainable utilization in Southern India. Int. J. Adv. Geosci. 2014, 2, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Zhu, X.Q. Chemical characteristics of groundwater in Xuanhua basin and assessment of irrigation applicability. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 25499-2010; Water Quality Standard of Green Land Irrigation for Urban Sewage Reclamation. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Jandu, A.; Malik, A.; Dhull, S.B. Fluoride and nitrate in groundwater of rural habitations of semiarid region of northern Rajasthan, India: A hydrogeochemical, multivariate statistical, and human health risk assessment perspective. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 3997–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F. The Groundwater Quality Assessment and Response of Different Irrigation Water Sources to Groundwater in Jinghuiqu Irrigation District; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2016; pp. 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yidana, M.S. Groundwater classification using multivariate statistical methods: SouthernGhana. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2010, 57, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, N.J.; Shukla, U.K.; Ram, P. Hydrogeochemistry for the assessment of groundwater quality in Varanasi:a fast-urbanizing center in Uttar Pradesh, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 173, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.K.; Das, S. Assessment of groundwater quality from Bankura I and II Blocks, Bankura District, West Bengal, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 2787–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, S.; Hinaje, S.; El Fartati, M.; Gharmane, Y.; Yaagoub, D. Assessment of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation in the Timahdite-Almis Guigou Area (Middle Atlas, Morocco). Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Jin, D.W.; Yang, J. Heavy metal pollution characteristics and source analysis of water drainage from a mine in Inner Mongolia. Coal Geol. Explor. 2021, 49, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Singha, S.; Pasupuleti, S.; Singha, S.S.; Kumar, S. Effectiveness of groundwater heavy metal pollution indices studies by deep-learning. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2020, 235, 103718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 14848-2017; Standard for Groundwater Quality. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Gao, M.X. Effects of Sulfur Supply on Cadmium up Take and Accumulation in Rice Seedlings; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).