1. Introduction

In recent years, water inrush incidents in tunnels have continued to severely affect the safety of tunnel construction and operation, resulting in substantial losses to the industry. Therefore, accurately and promptly predicting concealed water-conducting or water-bearing structures ahead of the tunnel face is of paramount importance for effective water management and ensuring the operational safety of tunnels. The electrical resistivity of concealed water-conducting or water-bearing structures is much lower than that of the surrounding rock, and are therefore referred to as anomalous bodies. To achieve precise detection, the Transient Electromagnetic Method (TEM), due to its non-invasive nature, high sensitivity, and capability for deep penetration, has been widely applied for identifying geological anomalies in tunnel areas [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In addition to the TEM, several geophysical approaches have been applied to subsurface or confined underground environments. For example, Rucker [

5] utilized electrical resistivity combined with cokriging to estimate moisture distribution, while Ezersky and Eppelbaum [

6] discussed geophysical monitoring frameworks for underground constructions. These studies demonstrate that resistivity and integrated geophysical monitoring can effectively complement the TEM in characterizing hydrological and structural anomalies in underground spaces.

The ground-based TEM, owing to its advantages such as sensitivity to low-resistivity bodies, relatively high lateral resolution, and minimal volume effect, has been adapted for tunnel applications, and a series of methodological and technical experimental studies have been conducted [

3,

4]. Traditional TEMs are predominantly based on the half-space assumption, but these models fail to fully account for the full-space characteristics inherent in specific environments like tunnel roadways [

7]. When employing TEMs for detection in tunnel roadways, the detection coil is surrounded by rock formations over a significant portion of its forward and rearward regions. Consequently, the surrounding environment closely approximates full-space conditions. Relying solely on half-space theory for inversion and interpretation inevitably introduces errors, resulting in inaccuracies in the outcomes of TEM-based advanced detection [

8]. Therefore, in-depth investigation into the full-space effect of the TEM holds substantial theoretical significance and engineering relevance [

9].

Numerous advances have been achieved in TEM theory and modeling over the past decades. For instance, Ward and Hohmann [

3] comprehensively summarized full-space and half-space electromagnetic induction theories. Modern studies have moved beyond half-space assumptions with the advent of 1D/2D/3D modeling and inversion techniques since the 1990s. Swidinsky and Nabighian [

10] modeled transient fields of buried sources, and Swidinsky and Liu [

4] provided analytic solutions for specific targets, reflecting the capability to handle complex geometries without assuming a half-space. Despite these advancements, applying full 3D inversions in underground settings can be resource-intensive, and analytical insights are valuable for understanding fundamental behavior. In fact, prior studies on full-space vs. half-space TEM responses have reported ratio coefficients ranging from 0.6 to 2.5 under various conditions, such as anomaly size, distance, conductivity contrast, and measurement time [

11,

12,

13]. For instance, Yang et al. [

11] concluded that the apparent resistivity inverted from full-space TEM responses ranges from 0.67 to 2.5 times that derived from half-space responses through comparative analysis of analytical formulas and measured data. When a large conductive anomaly dominates the response, the ratio coefficient approaches 0.67. However, the ratio coefficient is close to 2.5 for a nearly homogeneous medium. Liang et al. [

12] proposed that in the absence of anomalous bodies within the surrounding rock, the ratio coefficient between full-space and half-space TEM responses is 2.0 during the early stage and 2.5 during the late stage based on analytical calculations; correspondingly, the ratio of apparent resistivities should be 1.842. Ouyang et al. [

13] indicated that the ratio coefficient between full-space and half-space TEM responses ranges from approximately 1.9 to 1.96 when anomalous bodies are present. Nevertheless, these results vary considerably and lack a unified interpretation, particularly in the presence of anomalous bodies.

Most studies generally agree that, under homogeneous field conditions without anomalous bodies, the ratio coefficient between full-space and half-space TEM responses ranges from approximately 2.0 to 2.5. In contrast, under conditions with anomalous bodies, this coefficient typically ranges from approximately 1.5 to 2.5. In summary, the ratio coefficients reported in these studies are not entirely consistent, indicating that variable factors influence the ratio coefficient between full-space and half-space TEM responses. Thus, a systematic analytic investigation is necessary that can clarify how anomalies alter the full-space/half-space response ratio.

This study addresses this gap by deriving an analytical forward solution for TEM responses with an anomalous body under both full-space and half-space conditions. Building on classical thin-layer theory, we develop expressions for each case and then define a ratio coefficient to quantify the full-space effect. Subsequently, a comprehensive sensitivity analysis is conducted, varying the anomalous body’s distance, thickness, conductivity, and measurement time. The novelty of this work lies in establishing a clear functional dependence of the full-space effect on those parameters and identifying conditions under which the full-space and half-space responses converge or diverge. These insights can inform practitioners when a full-space model is necessary and when simpler models are sufficient.

2. Analysis of TEM Response of Anomalous Bodies in Tunnels Under Different Spatial Conditions

2.1. Thin-Layer Theory for TEM Response of Anomalous Bodies

Based on horizontal thin-layer theory [

1,

14], the expression for the current density at any spatial point at a distance (

) from the center of the magnetic dipole source is expressed by Equation (1). The definition of a thin layer refers to a situation where the thickness of the low-resistivity conducting layer is much smaller than the diffusion depth of the transient electromagnetic field in the time domain (or the skin depth of TEM in the frequency domain). The thickness of the low-resistivity layer is much smaller than the diffusion depth of the TEM field, and the time

t after turn-off is sufficiently long (e.g., ≥10 μs for typical tunnel conditions). The magnetic dipole source is positioned at the center of the model, while the surrounding space is discretized into thin layers. The boundary conditions include a homogeneous surrounding rock medium and a low-resistivity anomalous body located at a specified depth.

where

is the current density at a spatial point at a distance from the magnetic dipole source at time after the excitation current is turned off.

is the magnetic dipole moment (A·m

2) of the excitation source.

is the depth of the low-resistivity layer (m).

is the longitudinal conductivity of the low-resistivity body (S/m).

represents the permeability of free space, defined as 4π × 10

−7 H/m.

From Equation (1), the expressions for the electric field and magnetic field at any spatial point in the TEM field can be further derived, as shown in Equations (2) and (3). This derivation process can be found in

Appendix A.

where

represents the electric field component in the z-direction.

means the magnetic field component in the z-direction.

is the voltage induced in the receiver coil along the z-direction.

2.2. Expression for TEM Response Under Full-Space Anomalous Body Conditions

Because the source is a magnetic dipole producing primarily vertical magnetic flux in a central-loop configuration, eddy currents are induced in horizontal loops within each layer. These currents are largely confined to their layer, particularly when the layers are thin and electrically separated by slight contrasts. There could be some interaction between induced currents in adjacent layers, particularly when they are at different conductivities. However, the interaction between layers is second-order, and this phenomenon does not strongly couple except through the common primary field [

1,

14]. Thus, each horizontal thin layer responds independently to the primary field.

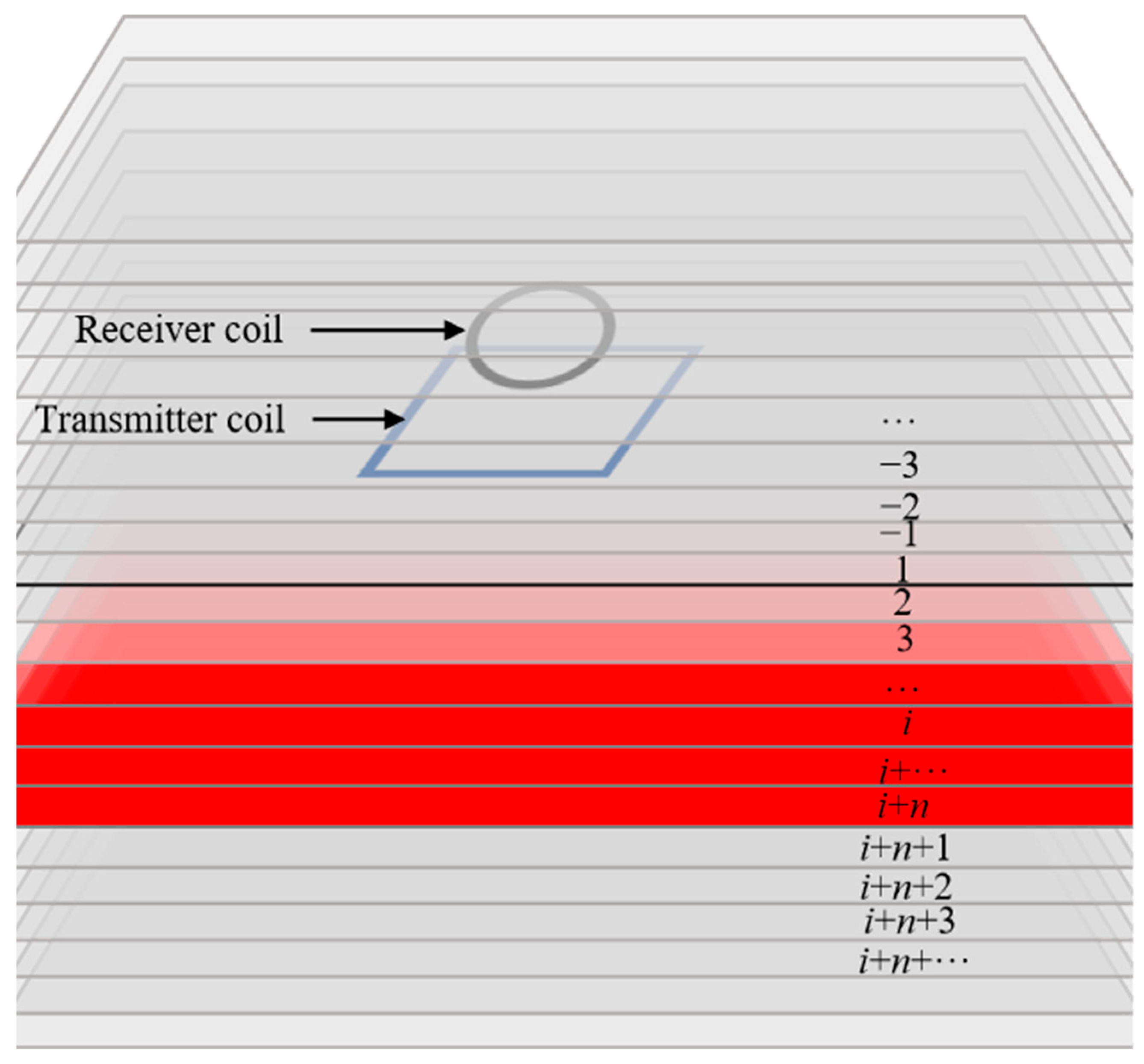

Given that Equation (1) involves two variables,

and

, and the conductivity parameter

changes discontinuously between the host medium and the anomalous body, direct integration of Equation (3) is infeasible. To derive the expression for the TEM response under full-space conditions with an anomalous body, a summation approach was adopted [

15]. In the full-space scenario, the environment is modeled as an infinite homogeneous medium extending in all directions, as shown in

Figure 1. Accordingly, the medium surrounding the magnetic dipole source is discretized into an infinite number of parallel thin layers within the full-space model. The normal direction of these parallel thin-layer interfaces is aligned with the line connecting the centers of the anomalous body and the magnetic dipole source. Critically, it is assumed that at most one low-resistivity anomalous body exists within the full-space medium. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the layers ahead of the magnetic dipole source are defined as Layer 1, Layer 2, …, Layer

i, …, Layer

i +

n, …; similarly, the layers behind the source are defined as Layer −1, Layer −2, … Here, Layers

i through

i +

n constitute the low-resistivity anomalous body. Under this discretization scheme, the TEM response received by the coil is approximated as the superposition of signals generated by the infinite horizontal eddy currents induced within each of these thin layers throughout the medium.

Equation (5) describes the composition of the signals received by the receiver coil:

where

represents the total TEM response (T) received by the receiver coil;

denotes the TEM response (T) generated by the medium in front of the receiver coil;

signifies the TEM response (T) produced by the medium behind the receiver coil;

is the additional term (T) resulting from the difference in the multiplicative relationship between full-space and half-space effects under homogeneous medium conditions. This term is derived from a thin-layer theory approximation for the virtual component generated in full-space, lacking specific physical significance;

refers to the additional error TEM response (T) introduced by the mutual inductance of the coil and the influence of surrounding conductive structures.

is introduced as a calibration term. Under homogeneous full-space conditions, it is chosen so that the full-space response is 2.5 times the half-space response. Thus, has no real physical source. Rather, it acts as a virtual correction term that compensates for the approximation inherent in the thin-layer summation, ensuring consistency with the mirror-image result.

Under the condition of a homogeneous medium, the TEM response intensity in a full-space is 2.5 times that in a half-space [

16]. Therefore, it can be approximately considered that the relationship between the TEM response in a full-space and that in a half-space under the condition of homogeneous surrounding rock medium is as follows:

where

is the total full-space TEM response under full-space conditions, and

is the total half-space TEM response under half-space conditions.

Because the full-space model is the mirror image of the half-space model, it can be considered that

in the homogeneous medium case, so it is easy to deduce:

Thus, we can derive the expression of TEM response under the condition of a full-space anomalous body as follows:

where

is the total full-space TEM response (V/A) received by the coil under full-space conditions.

Through a sequence of transformations, the summation formula in Equation (8) is processed by disassembling and recombining the polynomial terms. This process results in the conductivity

within each individual term becoming a fixed constant. Consequently, the conductivity

within each term is rendered continuously differentiable. Therefore, Equation (8) can be rewritten in integral form, as shown in Equation (9).

where

and

represent the conductivity terms of the medium surrounding and the anomalous body, respectively;

x denotes the integration variable of the depth.

Equation (9) is derived by applying the summation method to account for the contributions of each thin layer. The first two integrals cover contributions from the homogeneous host (conductivity

), and the last one covers the anomalous layer (conductivity

). Based on thin-layer theory and solving Equation (9), Equation (10) can be obtained, which represents the expression for the full-space TEM response under anomalous body conditions.

where the first term represents the response of the homogeneous surrounding medium, while the remaining terms arise from the anomalous layer.

Equation (10) represents the expression for the full-space TEM response under the condition of an anomalous body, derived through the analysis. The first term in the equation corresponds to the full-space TEM response under the condition of a homogeneous surrounding medium. In this case, it is assumed that each thin layer in the space is a surrounding rock medium, which means that its response is inherently independent of factors such as the distance, thickness, and conductivity of the anomalous body. Consequently, the first term in the equation is solely related to the conductivity of the surrounding rock. The last two terms, on the other hand, represent the TEM response induced by the anomalous body. Since the exponent of the variable in the denominator is greater than that in the numerator, the overall full-space TEM response value decreases as the distance to the anomalous body increases. When the thickness of the anomalous body increases, the difference between the last two terms of Equation (10) also increases; therefore, a greater thickness of the anomalous body results in a more pronounced TEM response.

2.3. Expression for TEM Response Under Half-Space Anomalous Body Conditions

Building on the analytical expression for the full-space TEM response of an anomalous body, the thin-layer theory was similarly employed to analyze the TEM field of the anomalous body under half-space conditions. Because the air above the coil has essentially zero conductivity, those layers do not induce currents. Therefore, the medium surrounding the magnetic dipole source was subdivided into an infinite number of parallel thin layers for the half-space scenario.

The normal direction of these parallel thin-layer interfaces coincides with the line connecting the centers of the anomalous body and the magnetic dipole source. It is stipulated that at most one low-resistivity anomalous body exists within the half-space medium. The layers ahead of the magnetic dipole source are defined as Layer 1, Layer 2, …, Layer

i, …, Layer

i +

n, …. Here, Layers

i through

i +

n constitute the low-resistivity anomalous body. Thus, the TEM response received by the receiver coil is approximated as the superposition of signals generated by the infinite number of horizontal electromagnetic eddy currents existing within each horizontal thin layer throughout the space. Given that the resistivity of the air medium approaches infinity under non-breakdown states, it can be approximated that no TEM induction occurs behind the receiver coil, representing the half-space problem, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Thus, the term

behind the receiver coil is omitted. Equation (11) expresses the composition of the signal received by the receiver coil under half-space conditions:

where

is the total half-space TEM response (V/A) received by the coil;

is the TEM response (V/A) generated by the medium ahead of the receiver coil;

is the additional error TEM response (V/A) arising from the coil mutual inductance effect and the influence of surrounding conductive structures.

Under ideal conditions, neglecting the additional error TEM response, Equation (11) can be expressed as:

Under ideal half-space conditions without instrumentation error, the total received signal equals

from the space ahead of the receiver. This primary field is decomposed into three components corresponding to (1) surrounding rock in front of the anomaly from Layer 1 up to the layer before the anomalous body, (2) the anomalous body itself, and (3) surrounding rock immediately after the anomaly. This linear superposition is possible because the induced currents in each region contribute additively to the observed field [

1]. A similar approach of segmenting the response was employed by Chen et al. [

15] in their layered TEM model. Thus, the magnetic field in the coil can be regarded as the linear superposition of the magnetic fields generated by the three front regions of the medium based on the thin-layer theory. Assuming the anomalous body is located ahead of the coil,

consists of the following three components.

where

is the TEM response (V/A) generated by the surrounding rock formation from Layer 1 to Layer

(refer to

Figure 2 for the layer numbering convention);

is the TEM response (V/A) generated by the low-resistivity anomalous body spanning from Layer

to Layer

;

is the TEM response (V/A) generated by the surrounding rock formation behind the anomalous body.

Since an integral expression is impractical, a summation formula is employed for computation, with the lower integration limit effectively starting from the first thin layer. Thus, Equation (13) can be rewritten as:

where

is the total half-space TEM response (V/A) received by the coil under half-space conditions;

is the conductivity of the surrounding rock medium (S/m); and

is the conductivity of the low-resistivity anomalous body (S/m).

Through a series of transformations involving polynomial expansion and recombination within the summation of Equation (14), the conductivity S within each term becomes a fixed constant, rendering S continuously differentiable within each term. Consequently, Equation (14) can be expressed in integral form:

Based on thin-layer theory and solving Equation (15), Equation (16) can be obtained, which represents the half-space TEM response.

where the first term represents the response of the homogeneous surrounding medium, while the remaining terms arise from the anomalous layer.

Equation (16) represents the analytical expression for the TEM response in the presence of an anomalous body under half-space conditions, derived approximately in this section based on the thin-layer theory.

2.4. Expression for the Full-Space Effect of a Tunnel Anomalous Body

By comparing the approximate expression for the TEM response of the anomalous body under full-space conditions given by Equation (10) with that under half-space conditions given by Equation (16), the relationship between the full-space and half-space TEM responses in the presence of an anomalous body can be derived as follows:

where

is the ratio coefficient between the full-space and half-space TEM responses, and it is dimensionless.

For scenarios involving an anomalous body, the ratio coefficient relating the full-space TEM response to the half-space TEM response can be derived according to Equations (10) and (16), as shown in Equation (18). This ratio is taken after ensuring both expressions are formulated per unit transmitter current and under the same anomalous conditions.

where the first term represents the response of the homogeneous surrounding medium, while the remaining terms arise from the anomalous layer.

Henceforth, the ratio coefficient between the full-space and half-space TEM response will be referred to simply as the ratio coefficient .

3. Sensitivity Analysis of the Full-Space Effect on TEM Response Signals for Tunnel Anomalous Bodies

3.1. Influence of Anomalous Body Distance and Thickness on the Full-Space Effect Coefficient

Due to its complex form, Equation (18) is difficult to simplify directly. To investigate the influence of the anomalous body’s thickness and its distance from the transmitter coils on the ratio coefficient, let

s serve as a representative early-time point for TEM systems, which typically operate in the 10~100 μs range. This early time highlights the initial response; we later vary

t in

Section 3.3. Then, the following equation can be obtained.

When measurements are conducted using the central-loop configuration (where the centers of the receiver and transmitter coils coincide),

r is equal to 0 for simplicity. If

r is not equal to 0, the full-space/half-space ratio would be slightly altered. However, initial checks suggest this effect is small for typical coil separations. Then, Equation (18) can be simplified to:

Assigning typical values to

and

: the conductivity of the general surrounding rock is approximately

, while the conductivity of groundwater is approximately

. Equation (20) can be further simplified to:

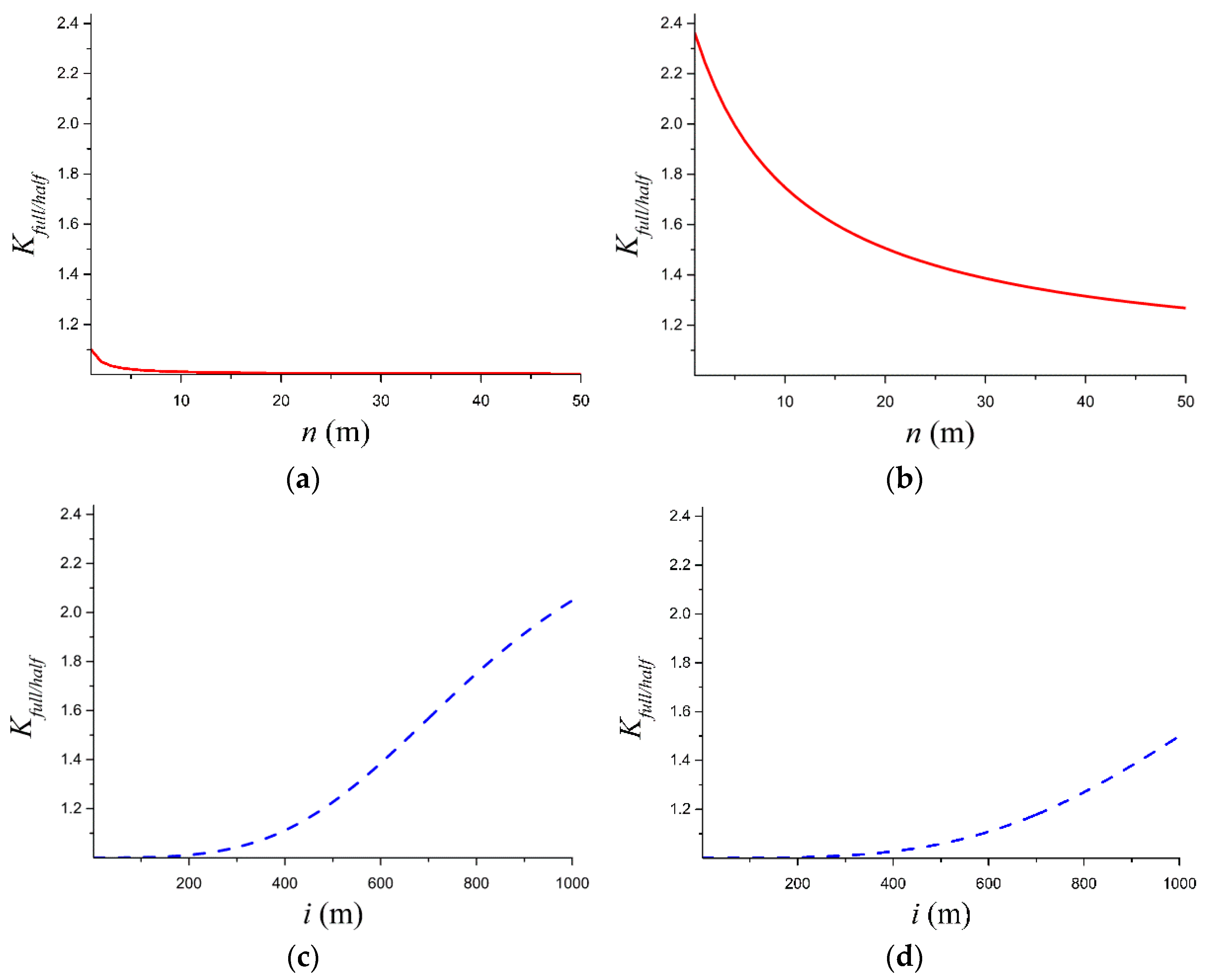

Equation (21) represents the analytical expression for the ratio coefficient between the full-space and half-space responses under the conditions s and medium conductivities and . Since multiple variables potentially influence the ratio coefficient, Equation (21) provides a clearer basis for studying the specific effects of the anomalous body distance () and thickness () on this coefficient.

Through the derivation above, this study obtains the ratio coefficient

relating the TEM response intensities under full-space and half-space conditions for varying anomalous body thicknesses and distances, as expressed by Equation (21). Given the complexity of the expanded form of this equation, the influence of the variables on the function value can be more intuitively understood through 3D surface plots and contour plots.

Figure 3 illustrates the 3D surface graph corresponding to Equation (21). The anomalous body position is represented by both distance and thickness. Here

i is the distance from the transmitter/receiver to the center of the anomalous body, and

n is the thickness of the anomalous body. Both are varied to observe their effect on the ratio.

As observed in

Figure 3, when the anomalous body is located far from the receiver coil, the ratio coefficient between the full-space and half-space TEM responses approaches that of a homogeneous medium, approximately 2.5. When the anomalous body is located close to the receiver coil, the ratio coefficient decreases gradually to approximately 1.0. The thickness of the anomalous body also exerts a significant influence on the ratio coefficient. Specifically, smaller anomalous body thicknesses correspond to larger ratio coefficients. As the anomalous body thickness increases, the ratio coefficient decreases gradually.

To precisely observe the individual influences of anomalous body distance and thickness on the ratio coefficient, cross-sections were taken through the 3D surface plot of the function in

Figure 3, generating 2D curves where one variable is held constant. These curves are shown in

Figure 4.

When the distance from the anomalous body to the working face is less than 200 m, the ratio coefficient derived based on the thin-layer theory (assuming infinite lateral extent) is relatively small, ranging from approximately 1.0 to 1.1. Note: In practical scenarios, anomalous bodies cannot be infinitely large in the direction perpendicular to the magnetic dipole [

17]. Consequently, the measured ratio coefficient in real surveys would likely be larger than this analytical result. Within this distance range, the influence of anomalous body thickness on the ratio coefficient is minor. When the anomalous body is located far from the working face (greater than 800 m),

Figure 4b shows that the ratio coefficient is consistently greater than 1.3. For thin anomalous bodies, the coefficient approaches approximately 2.3, nearing the value of 2.5 observed for a homogeneous medium. This indicates that when the anomalous body is sufficiently distant from the receiver coil and sufficiently small, the ratio coefficient between the TEM responses under conditions with the anomalous body and under homogeneous conditions (without the anomalous body) converges.

The functional relationship depicted by the 3D surface in

Figure 4 primarily arises from the relative contribution of the TEM response signal generated by the anomalous body compared to that generated by the surrounding rock formation. When the anomalous body is distant or has a small thickness, its TEM response signal is weaker. In these cases, the TEM response signal from the surrounding rock medium dominates. Consequently, the ratio coefficient approaches the value characteristic of a homogeneous medium (i.e., the TEM response relationship when the entire surrounding space is filled with the surrounding rock medium). Conversely, when the anomalous body is close or has a large thickness, the TEM response signal from the anomalous body itself dominates absolutely within the measured response, often exceeding that of the ambient surrounding rock by several orders of magnitude [

18]. Therefore, the ratio coefficient approaches 1.0 under these conditions. The smooth 3D surface observed is formed by the continuous and smooth distribution of the ratio coefficient values across the intermediate ranges of anomalous body distance and thickness.

3.2. Influence of Surrounding Rock Conductivity on the Full-Space Effect Coefficient

The conductivity of the medium frequently exerts a significant influence on TEM response results. To systematically investigate the effects of the surrounding rock conductivity

and the anomalous body conductivity

on the ratio coefficient

between the full-space and half-space TEM responses, other variables in Equation (18) are assigned fixed values for simplification. Let

. For measurements using the central-loop configuration or where the distance between the receiver and transmitter coils is small, set

m. Use the variable values corresponding to a ratio coefficient

from the previous section:

m (anomalous body thickness),

m (anomalous body distance). Following the derivation methodology of Equation (21), substituting these assigned values into Equation (18) yields Equation (22). This equation expresses the influence of the variables

and

on the ratio coefficient

. To analyze this equation, a 3D surface plot of the ratio coefficient

versus the variables

and

was generated, as shown in

Figure 5.

As observed in

Figure 5, although the ratio coefficient K increases as the conductivity of the anomalous body

decreases, this influence is extremely weak and practically negligible. Conversely, the conductivity of the surrounding rock

exerts a predominant influence on the ratio coefficient. When the surrounding rock conductivity is

(indicating water-saturated surrounding rock), the ratio coefficient is generally larger. When the surrounding rock conductivity is relatively low, the ratio coefficient approaches 1.0. The cross-sectional view of the 3D surface plot in

Figure 6 provides a clearer depiction of this relationship.

When the electrical conductivities of the anomalous body are

and

, respectively, despite a difference spanning three orders of magnitude, the curve morphology and magnitude of the ratio coefficient remain essentially consistent. This indicates that the ratio coefficient exhibits low sensitivity to the conductivity of the anomalous body. Once the anomalous body conductivity

far exceeds the surrounding rock conductivity

, the ratio coefficient levels off and becomes insensitive to further increases in

, as shown in

Figure 6.

Conversely, the ratio coefficient demonstrates significant sensitivity to the conductivity of the surrounding rock. As illustrated in

Figure 6a,b, when

, the ratio coefficient values are consistently below 1.1, whereas at

, the ratio coefficient values are all greater than 2.1. This demonstrates that the surrounding rock conductivity exerts a pronounced influence on the ratio coefficient. Specifically, lower surrounding rock conductivity (closer to that of the anomalous body) results in a larger ratio coefficient, whereas higher surrounding rock conductivity (yielding a greater contrast with the anomalous body) drives the ratio coefficient closer to 1.0.

The analysis indicates low sensitivity to anomaly conductivity, which is consistent with other studies of localized conductors [

3]. Therefore, the asymptotic behavior of the ratio coefficient (approaching 2.5 or 1.0) mirrors what a layered-earth model would predict for homogeneous cases [

3].

The underlying mechanism of this phenomenon can be deduced from Equation (22). When the surrounding rock exhibits high electrical conductivity, its TEM response predominates. Under these conditions, the first terms in both the numerator and denominator of Equation (22) overwhelmingly dominate in magnitude. Consequently, the ratio coefficient converges toward the ratio of these first terms in the numerator and denominator. Conversely, when the surrounding rock possesses low electrical conductivity, its TEM response becomes significantly weaker than the anomalous response of the target body. In this scenario, the ratio coefficient approaches the ratio of the subsequent four terms in the numerator and denominator of Equation (22), namely 1.0. This analysis demonstrates that the TEM can accurately characterize anomalous bodies only when the surrounding rock conductivity is notably lower than that of the anomalous body. Conversely, in environments with extremely high surrounding rock conductivity (e.g., the water-bearing faults and fracture zones), the detection accuracy of the TEM for hydrous anomalous bodies significantly decreases.

3.3. Impact of the Off-Time and Anomalous Body Distance on the Full-Space Effect Coefficient

Existing studies have demonstrated that the distance to the anomalous body significantly affects the time-dependent characteristics of the TEM response [

19,

20]. Generally, as the distance to the anomalous body increases, the pronounced variations in the TEM response shift toward later time channels. When the anomalous body is distant, the early-stage TEM response curves often fail to reveal discernible anomalous features. Therefore, this section investigates the influence of two variables, i.e., the distance to the anomalous body and the off-time, on the ratio coefficient. For computational convenience and consistent with Equation (19), we define

= 1, 2, 3, … 500, corresponding to off-times

= 1.256 ms, 2.512 ms, 3.768 ms, … 628 ms. Other parameters remain fixed. When the central-loop configuration is used for measurement, the center of the receiver coil coincides with the center of the transmitter coil. The thickness of the anomalous body is 10 m, and medium conductivities are

and

.

Under these conditions, Equation (18) simplifies to:

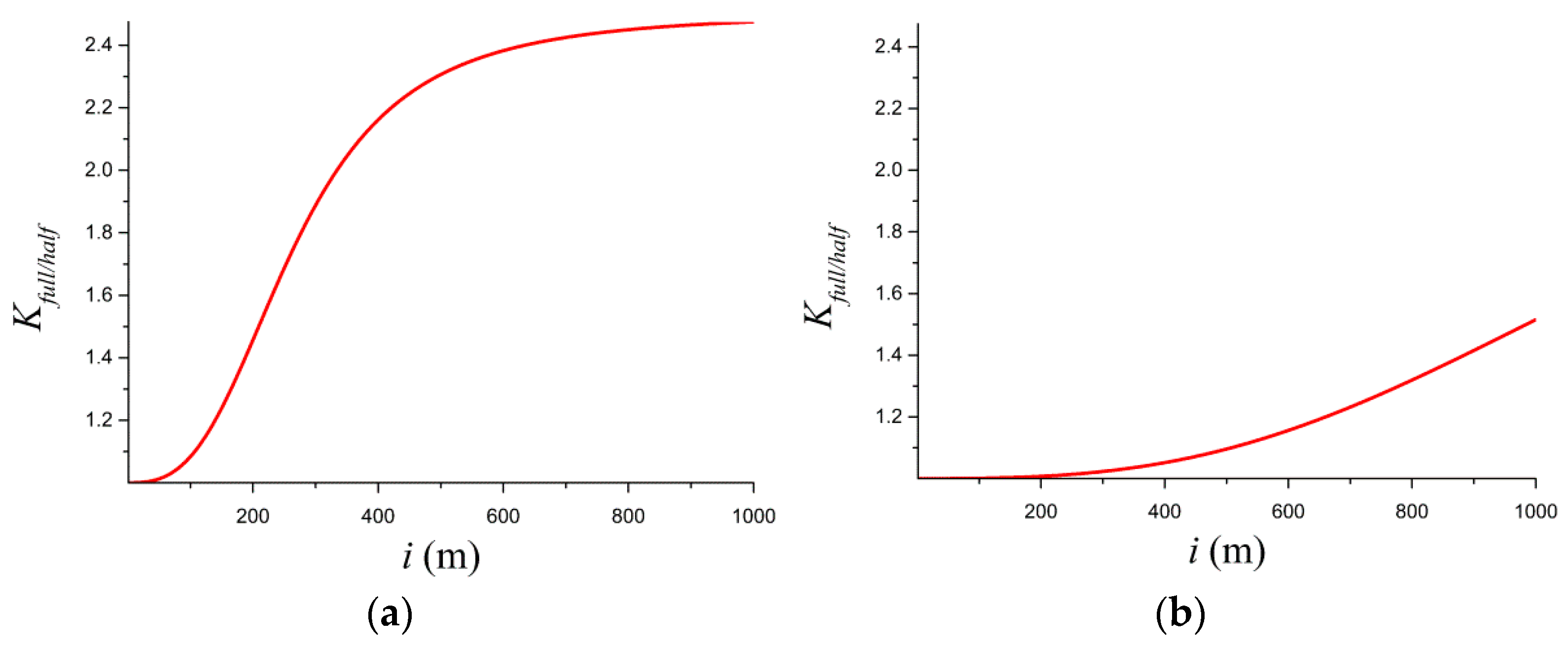

Equation (23) establishes the ratio coefficient as a function of off-time and distance to the anomalous body. To intuitively examine variable influences,

Figure 7 plots a 3D functional surface of the ratio coefficient versus off-time and distance to the anomalous body, with the time axis displayed on a logarithmic scale.

Figure 7 reveals that off-time exerts pronounced influence on the ratio coefficient. Early off-times correspond to larger ratio coefficients, and as time progresses, the ratio coefficient asymptotically approaches 1.0. Distance similarly demonstrates significant impact. At small distances, the ratio coefficient remains near 1.0, while at larger distances, the ratio coefficient exhibits substantial enhancement, approaching 2.5 (characteristic of homogeneous media) during early times.

For enhanced variable analysis, orthogonal sections of the 3D surface (

Figure 7) yield 2D profiles (

Figure 8).

Figure 8a,b explicitly demonstrate the monotonic increase in the ratio coefficient with distance, reaching ≈2.5 at large distance and early off-time.

Figure 8c,d further confirm the distinct decreasing trend of the ratio coefficient with increasing time.

During early off-times, the TEM field is dominated by the decaying primary field, while eddy currents within the anomalous body remain at negligible amplitudes. Consequently, the TEM response primarily originates from secondary fields induced in proximal surrounding rocks, yielding a ratio coefficient characteristic of homogeneous media conditions. Conversely, at late off-times, secondary fields in surrounding rocks attenuate to marginal levels, decaying eddy currents in the anomalous body generate enhanced secondary fields, and the measured signal becomes dominated by the anomalous body’s secondary field, driving the ratio coefficient asymptotically toward 1.0. Critically, the distance to the transmitter coil governs the induction onset timing and secondary field emission of the anomalous body, thereby exerting significant control over the ratio coefficient.

3.4. Verification by Numerical Simulation

In the simulation solution, the three-dimensional half-space and full-space models are adopted in the COMSOL software (Version 5.4). The excitation coil is located at the center of the three-dimensional model, and the normal direction of transmitter coil is perpendicular to the Cartesian X-Y plane [

21]. The model is shown in

Figure 9. Under the same conditions of rock medium and electrical parameters of the anomalous body, the ratio coefficients of the transient electromagnetic response in the full-space and half-space were calculated. The results are shown in

Figure 10.

Based on the changes in the coefficient values, the transient electromagnetic response relationship between the full-space and the half-space can be divided into three stages.

Stage I: At this stage, the received transient electromagnetic response is mainly the secondary field response generated by the surrounding rock around the loop. Therefore, the value of the transient electromagnetic response and the coefficient are close to the transient electromagnetic response under the condition of homogeneous medium without anomalous bodies. Here, the ratio coefficient is 2.5.

Stage II: At this stage, the received transient electromagnetic response is the superposition of the secondary field response of the surrounding rock and the secondary field response of the anomalous body. The secondary field response value of the anomalous body gradually exceeds that of the surrounding rock. Thus, the value of the ratio coefficient lies between 1.0 and 2.5.

Stage III: At this stage, the received transient electromagnetic response is the superposition of the secondary field response of the surrounding rock and the secondary field response of the anomalous body. However, the response of the anomalous body is significantly greater than that of the secondary field response of the surrounding rock. Therefore, the coefficient in this stage is close to the transient electromagnetic response under the condition of the anomalous body being close to the receiving coil. Currently, the ratio coefficient is 1.0.

Based on the above numerical simulation results, the ratio coefficient ranges from 1.0 to 2.5, which is consistent with the theoretical analytical results. Based on the above numerical calculation results, the results of theoretical analysis are reliable.

4. Analysis of Full-Space Effect Patterns for Tunnel Anomalies

The ratio coefficient effectively characterizes the relationship between TEM response intensities under full-space and half-space conditions in the presence of an anomalous body. Generally, a ratio coefficient approaching 2.5 indicates that the media within the detection zone approximate homogeneous conditions, with subdued anomalous body characteristics. Conversely, a ratio coefficient approaching 1.0 signifies that the TEM response of the anomalous body predominates within the detection region.

Due to this inherent property, factors enhancing the TEM response of the anomalous body typically reduce the ratio coefficient. For instance, increased anomalous body thickness intensifies its TEM response and lowers the ratio coefficient, while decreased distance between the anomalous body and the transmitter coil intensifies its TEM response and lowers the ratio coefficient. Although the anomalous body’s electrical conductivity significantly affects the anomalous response strength, further increases generally produce diminishing returns in the ratio coefficient, as its conductivity is usually several orders of magnitude higher than that of the surrounding rock. This is because the conductivity of the anomalous body is typically orders of magnitude higher than that of the surrounding rock. In contrast, altering the conductivity of the surrounding rock exerts a pronounced influence on the ratio coefficient. Specifically, reduced surrounding rock conductivity effectively amplifies the conductivity contrast between the anomalous body and the surrounding rock. This enhances the anomalous response and lowers the ratio coefficient. Moreover, increased surrounding rock conductivity raises the ratio coefficient. When the conductivity of the surrounding rock increases to approximately match that of the anomalous body, the ratio coefficient approaches 2.5. At this point, the surrounding rock and the anomalous body can be collectively regarded as a homogeneous medium with high conductivity. Consequently, a ratio coefficient of 2.5—equivalent to that of a homogeneous medium—is justifiable.

The ratio coefficient is influenced not only by the surrounding rock properties but also by temporal variations [

22]. According to the principle of transient electromagnetic responses under anomalous conditions, the process begins with the generation of a primary field when the excitation current is switched off. This primary field then diffuses into the surrounding rock. Following this, eddy currents are induced within the medium, and the decay of these eddy currents leads to the observed secondary field strength. Given the relatively low conductivity of the surrounding rock, the induced eddy currents are minimal. Conversely, the higher conductivity of the anomalous body typically results in stronger eddy currents. From an energy perspective, the temporal variation in the secondary field strength can be elucidated: both the secondary field strengths generated in the surrounding rock and in the anomalous body arise from the diffusion of the primary field produced by the excitation coil. Stronger eddy currents necessitate greater energy, thus requiring more time to attain their maximum intensity. As a result, the surrounding rock tends to exhibit a more pronounced secondary field earlier on, although its peak strength is significantly lower than that of the anomalous body. In contrast, the anomalous body typically takes a longer time to accumulate sufficient energy for the generation of stronger eddy currents, leading to a stronger secondary field upon the decay of these currents. Therefore, the peak time for the secondary field strength of the anomalous body is later than that of the surrounding rock at the same distance; however, its secondary field strength is often considerably greater than that of the surrounding rock. This phenomenon elucidates the time-dependent relationship of the ratio coefficient. Specifically, during the early phase after the current is switched off, the response from the surrounding rock dominates, with the ratio coefficient nearing that of a uniform field at 2.5. In the later phase, the response from the anomalous body becomes predominant, and the ratio coefficient approaches 1.0.

Due to the variation in the ratio coefficient with the characteristics of the surrounding rock parameters and time, it is quite challenging to apply a fixed ratio coefficient to convert the full-space TEM response to a half-space one. A fixed ratio coefficient may be suitable for only a few specific operational conditions and cannot adequately represent the proportional relationship between the full-space and the half-space under any conditions. Additionally, as the ratio coefficient is also a function of time, using a fixed coefficient directly in the half-space TEM inversion theory or applying it to the full-space TEM inversion after corrections will inevitably introduce some errors [

23].

Equations (18) and (21)–(23), derived from the thin-layer theory, are formulas formulated based on this theory. From these formulas, we can gain an analytical perspective on which factors significantly influence the ratio coefficient. However, these formulas exhibit considerable limitations in practical applications. The primary reason for this limitation is that the low-resistivity anomalies detected in real engineering projects are often restricted in horizontal dimensions, whereas the thin-layer theory is solved based on infinite horizontal thin-layer integrals. Consequently, the ratio coefficient obtained from practical engineering or model experiments will generally be greater than that derived from Equations (21)–(23). It should also be noted that aside from the thickness of the anomaly, the equivalent radius of the anomaly significantly affects the anomaly response as well. It can be easily inferred that the larger the equivalent radius of the anomaly, the smaller the ratio coefficient; conversely, the smaller the equivalent radius of the anomaly, the larger the ratio coefficient, approaching the ratio coefficient of 2.5 for a homogeneous medium.

Accordingly, the ratio coefficient

can be expressed as a function of the main influencing factors:

where

represents the off-time (s);

denotes the distance from the anomaly to the transmitter coil (m);

is the thickness of the anomaly (m);

is the equivalent radius of the anomaly (m); and

refers to the electrical conductivity of the surrounding rock (S/m).

Equation (24) includes only the variables that significantly influence the ratio coefficient as analyzed in this chapter. Other variable factors that may influence the ratio coefficient in practical engineering are not discussed.

In summary, the results from mathematical analysis reveal that the ratio coefficient for both full-space and half-space TEM responses ranges between 1.0 and 2.5 and is influenced by multiple factors. The variation pattern of the ratio coefficient obtained through mathematical analysis indicates that when changes in the surrounding rock or anomaly conditions enhance the TEM response of the anomaly—such as when the anomaly is closer to the receiver coil, has a greater thickness, or when the difference in electrical conductivity between the surrounding rock and the anomaly increases—the ratio coefficient decreases, potentially approaching 1.0. Conversely, when changes in the surrounding rock or anomaly conditions weaken the TEM response of the anomaly—such as when the anomaly is farther from the receiver coil, has a smaller thickness, or when the electrical conductivity of the surrounding rock is lower (closer to that of the anomaly)—the ratio coefficient increases, becoming more similar to the ratio coefficient of a homogeneous medium, which is 2.5. Additionally, the off-time has a pronounced impact on the ratio coefficient. Specifically, the earlier the time, the larger the ratio coefficient; as time increases, the ratio coefficient gradually approaches 1.0.

5. Discussion

Given the limited literature on underground TEM source interpretations, the analytic insights from this work provide a valuable complement to existing borehole or surface-source studies. They provide a baseline expectation for full-space effects that can inform more complex modeling efforts. It is important to recognize the scope of our analytical model. It assumes a laterally extensive anomalous layer (or multiple layers) and leverages 1D thin-layer superposition, making it most applicable to scenarios approximating this geometry (e.g., a large water-bearing zone ahead in a relatively layered host). In cases of more localized or 3D anomalies, or multiple anomalies, full 3D numerical inversion methods are more appropriate. However, tunnel anomalies are often finite or multiple (e.g., discrete cavities or fault zones). Therefore, the analytical model serves as a conceptual baseline, and practical interpretation of real tunnel data would require full 3D modeling and inversion.

Modern 1D, 2D, or 3D inversion techniques should be employed for detailed modeling when they are available and feasible. However, our analytical results provide quick diagnostic indicators. The analytical approach can serve as a verification tool or a way to gain physical intuition. For instance, it can help identify whether full-space effects are significant enough to warrant a full 3D inversion in a given scenario. If our ratio coefficient predicts a value close to 1.0, one might conclude that a simpler half-space-based interpretation could suffice; if it predicts something near 2.5, a more advanced modeling/inversion would likely be necessary to accurately interpret the data. Practitioners can use these findings to decide when the full-space effect is significant enough to warrant the added complexity of 3D interpretations.

6. Conclusions

Based on the thin-layer assumption of TEM diffusion propagation, the TEM response signals from the surrounding rock in each layer were integrated to obtain approximate expressions for TEM responses under both full-space and half-space conditions. This led to the derivation of analytical formulas for the ratio coefficients of TEM field responses in full-space and half-space scenarios, demonstrating that the ratio coefficient is a variable influenced by multiple factors.

Utilizing the derived analytical expressions for the ratio coefficient of TEM responses in both full-space and half-space, the influences of various factors on this coefficient were analyzed. The ratio coefficient increased with the distance from the anomaly, while it decreased with the increasing anomaly thickness, the increasing surrounding rock conductivity, and time passage.

Through theoretical analysis and sensitivity studies, it was found that the ratio coefficient of TEM responses in full-space and half-space ranged between 1.0 and 2.5 and was affected by multiple factors. Overall, as the response of the anomaly increased, the ratio coefficient approached 1.0, and conversely approached 2.5. This dynamic characteristic of the ratio coefficient provides a theoretical foundation for the precise inversion in TEM.

While this study focuses on the theoretical derivation and sensitivity analysis, future work will validate the model against field data and compare it with existing models to assess its performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Q. and Y.L.; methodology, W.Q.; formal analysis, X.M. and Y.Z.; investigation, Z.D.; resources, W.Q. and B.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.M. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.Q. and Z.D.; supervision, B.W.; funding acquisition, W.Q., B.W. and Z.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 52208395, No. 42404148, and No. 42174165) and the Science and Technology Project of Henan Transportation Department (Grant No. 2022-4-3).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciatively acknowledge the financial support of the abovementioned agencies.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhanjun Du was employed by the company Henan Provincial Communications Planning and Design Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Based on the horizontal thin-layer theory, the expression for the current density at any spatial point at a distance from the center of the magnetic dipole source is given by Equation (A1).

where

is the current density at a spatial point at a distance from the magnetic dipole source at time after the excitation current is turned off.

is the magnetic dipole moment (A·m

2) of the excitation source.

is the depth of the low-resistivity layer (m).

is the longitudinal conductivity of the low-resistivity body (S/m).

represents the permeability of free space, defined as 4π × 10

−7 H/m.

For the convenience of the derivation, the following formula is adopted to simplify some terms.

From Equation (A1), the expressions for the electric field and magnetic field at any point in the transient electromagnetic field can be derived [

24,

25,

26].

Equations (A4)–(A6) represent the spatial components of the half-space transient electromagnetic field under the condition of a thin-layered low-resistivity anomalous body.

Under the initial conditions,

, Equation (A4) can be simplified as follows.

When

is satisfied, Equation (A4) can be further simplified as follows.

Under the late-stage conditions,

, Equation (A4) can be simplified as follows.

Equation (A5) can be simplified as follows.

Equation (A6) can be simplified as follows.

When

is satisfied, Equation (A4) can be further simplified as follows [

24,

25,

26].

References

- Maxwell, J. A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism; Cambridge Library Collection; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1873; pp. 478–480. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Transient electromagnetic response characteristics and processing techniques for metal objects in roadways. J. China Coal Soc. 2008, 33, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, S.; Hohmann, G. Electromagnetic theory for geophysical applications. In Electromagnetic Methods in Applied Geophysics; Society of Exploration Geophysics: Houston, TX, USA, 1987; pp. 130–311. [Google Scholar]

- Swidinsky, A.; Liu, L. An analytic solution for numerical modeling validation in electromagnetics: The resistive sphere. Geophys. J. Int. 2017, 211, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D. Moisture estimation with in a mine heap: An application of cokriging with assay data and electrical resistivity. Geophysics 2010, 75, B11–B23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezersky, M.; Eppelbaum, L. Geophysical monitoring of underground constructions and its theoretical basis. Int. J. Georesources Environ. 2017, 3, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, X.; Liu, D.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, S. Study on the response laws of multi-ground-source semi-airborne transient electromagnetic method. Prog. Geophys. 2023, 38, 1341–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Cai, H.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Y.; Hu, X. Three-dimensional joint inversion of ground and semi-airborne transient electromagnetic data. Chin. J. Geophys. 2022, 65, 3997–4011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Qi, Z.; Cao, H. Research on advanced prediction method for unfavorable geological bodies in tunnels using borehole-roadway transient electromagnetic method. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2024, 48, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Swidinsky, A.; Nabighian, M. Transient electromagnetic fields of a buried horizontal magnetic dipole. Geophysics 2016, 81, E481–E491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yue, J. Response characteristics of 3D full-space transient electromagnetic method under the influence of roadways. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2008, 38, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Wu, Y. Multiple phenomena of mine transient electromagnetic field. J. Chongqing Univ. 2014, 37, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, J. Research on One-Dimensional Inversion of Tunnel Full-Space Transient Electromagnetic Effect. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Xue, G.; Li, H. Resolution capability of horizontal component of loop-source transient electromagnetic field to thin layers. Prog. Geophys. 2014, 29, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Cheng, J.; Wang, A. Numerical simulation of borehole transient electromagnetic response in mine full-space using integral equation method. Chin. J. Geophys. 2018, 61, 4182–4193. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xue, G.; Guo, H.; Zhou, N. Numerical analysis of direct time-domain response for transient electromagnetic field in homogeneous half-space. Chin. J. Geophys. 2018, 61, 750–755. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, C.; Tao, C.; Hu, Z. Full-space forward modeling method for magnetic anomaly field of finite-length cylinder. Chin. J. Geophys. 2017, 60, 1557–1570. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Yin, C.; Qiu, C.; Li, M.; Gao, Z. Finite element forward modeling of mine transient electromagnetic method under metal interference environment. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 4578–4589. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, C.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Kong, M. Physical simulation study on directional shielding of receiving coil for borehole transient electromagnetic method. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 3178–3187. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Qi, T.; Qin, S.; Qian, W. Instrument selection and coil arrangement for vehicle-borne transient electromagnetic detection of close-range water-bearing anomalies. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2022, 59, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, W.; Li, H.; Yu, J.; Gu, Z. Theoretical and experimental investigation of vehicle-mounted transient electromagnetic method detection for internal defects of operational tunnels. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Han, S.; Xue, G. Analysis of full-component response characteristics and detection capability of grounded-wire source surface-to-borehole transient electromagnetic method. Chin. J. Geophys. 2019, 62, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Wen, L.; Zheng, G. 3D FDTD forward modeling of half-space TEM based on full-space initial field source. Prog. Geophys. 2022, 37, 2147–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Shi, X. Principle and Application of Electromagnetic Sounding Method; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, A.; Alekseev, D.; Oristaglio, M. Chapter Twelve—Electromagnetic Soundings. Methods Geochem. Geophys. 2014, 45, 417–439. [Google Scholar]

- Brian, R.; Frank, C. Electromagnetic Sounding. Investig. Geophys. 1991, 2, 285–425. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).