Abstract

A significant number of people, either seasonally or permanently, migrate from the Thar Desert in Pakistan each year due to droughts caused by climate change. This study aims to investigate the determinants and consequences of these migration decisions, examine the effectiveness of migration as a climate adaptation strategy, and identify challenges in adapting to these changes. Data were gathered from 400 migrated households in the Mithi sub-district. A mixed-method approach was used, combining qualitative and quantitative methods. The findings revealed that threats to the standard of living, including lack of food and clean drinking water, unemployment, and limited educational and medical opportunities, were the primary reasons for permanent and temporary migration from ancestral locations. Migration significantly impacted the origin and destination regions, with positive or negative effects. Specifically, migrants identified various consequences for both the origin and destination communities, including population decline (63%), changes in age structure, increased demand for housing, economic fluctuations (73%), alterations in healthcare services, and increased psychological stress (77%). The study also revealed that individuals who migrated from the Thar Desert experienced improved conditions compared to their previous location, such as diversification of income sources, increased job stability, access to clean water and food, reduced health risks, and overall improvements in their living conditions. However, the destination communities faced significant challenges due to widespread resource depletion and environmental deterioration. Migrants encountered barriers to developing resilient livelihoods in destination areas, including lack of proper knowledge and information, institutional and government issues, environmental and technological challenges, and social and cultural issues. The study highlights the urgent need for comprehensive policies and sustainable solutions to address the root causes of migration and support the resilience of vulnerable populations.

1. Introduction

The world is currently facing an unprecedented increase in natural disasters, predominantly attributed to the escalating effects of climate change [1]. Increases in global temperatures, changes to regional and local precipitation patterns, increases in sea levels rising along coastlines, and the number of extreme weather events are some examples that illustrate climate change [2,3]. This trend has huge effects on people and their way of life [4]. The prospect of potential natural disasters, from droughts to floods, continues to represent a global environmental problem and social consequences [5]. Water is indispensable in sustaining life, ecosystems, and socio-economic development [6]. Increased global warming is mainly caused by anthropogenic activities and climate change which are causing fluctuations in climate systems and deterioration of water availability, especially in some vulnerable regions [7,8]. Global change in greenhouse gases has altered human water complex variation of the hydrological and climatic system [9]. More erratic precipitation affects agricultural livelihoods, particularly in rural areas, and underscores the inter-relationship between food security, human migration, and rainfall variability [10]. Rising global temperatures affect evapotranspiration, runoff, groundwater, precipitation, and soil moisture [11,12]. Human activities also impact atmospheric moisture content, with warmer air increasing evaporation and potentially leading to more severe droughts [10].

Droughts pose a significant threat worldwide, particularly in regions reliant on essential water-related ecosystem services, impacting developed and developing nations [11]. Arid and semi-arid areas frequently experience recurrent droughts [12]. The 21st century has witnessed a substantial shift in the rate and strength of floods and droughts compared to the 20th century. Consequently, prolonged droughts have led to severe degradation of water resources, regional agriculture, and ecological systems [13]. This has resulted in a substantial increase in displacements. By 2050, projections for the number of climate migrants vary widely, ranging from 25 million to 300 million [14]. In Asia, Africa, and Latin America, climate-induced internal rural-to-urban migration is already occurring, contributing to the emergence of mega-slums [15]. Cross-border migration triggered by climate factors can destabilize both the countries of origin and destination [16]. For instance, prolonged severe droughts in Central American countries such as Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador compel hundreds of thousands to seek economic refuge in the United States. Mass migration from economically disadvantaged countries to wealthier neighbouring nations often results in political confusion and policy challenges in the host countries [17]. By 2030, it is projected that water scarcity and drought in the Middle East and North Africa could force up to 700 million people to migrate within the region or leave it altogether [18].

Pakistan encompasses vast arid and semi-arid regions, particularly in the southeast and southwest, which are highly susceptible to climate change impacts, including rising temperatures, droughts, and desertification [19]. Tharparkar, situated in the south-eastern corner of Sindh province, is notably affected by recurrent droughts and environmental degradation due to its minimal rainfall and hot climate [20]. The frequency and severity of these droughts have intensified in recent years, driven by a reduced monsoon season, pollution, and climate change. For instance, the 2014 monsoon season delivered a meagre 124 mm of rain to Tharparkar, compared to 190 mm in 2013 and 220 mm in 2012 [21]. This inadequate rainfall during the critical monsoon season significantly exacerbated the drought conditions that had been developing over the preceding years, with the diminished monsoon rains leading to the death of vegetation and the destruction of grazing lands, depriving livestock of food, and failing to recharge aquifers and artificial lakes, resulting in insufficient water for drinking, sanitation, and agriculture [22]. Consequently, the persistent droughts have rapidly depleted the natural environment and human communities. During prolonged dry periods, water supplies dwindle, leading to the complete drying of streams and ponds, the withering of grasslands, and the malnourishment of livestock [13]. The continuous environmental stress has forced long-established native communities to abandon their ancestral villages, with acute water scarcity compelling women and children to travel long distances carrying heavy matkas (large earthen pot) to fetch water for domestic use, while impoverished men migrate seasonally or permanently to neighbouring villages and cities in search of work [23]. This departure has led to the feminization of villages, as many men establish households in urban slums, leaving behind their parents, wives, and children [24]. The women left behind face immense hardships in caring for the elderly, children, and livestock, with malnutrition remaining prevalent due to food insecurity and the lack of governmental health facilities [25]. Climate experts have warned that Tharparkar may experience even more recurrent and acute droughts due to climate change, and without substantial investments in sustainable water supplies and livelihood sources, up to a million more people could be displaced from the region by 2050 [26].

The existing body of literature on climate change-induced drought and its repercussions in Pakistan offers a substantial source of information on health, livelihoods, displacement, and adaptation strategy outcomes [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Despite the growing recognition of migration as a resilience-enhancing adaptation strategy, significant research gaps persist. Migration is not extensively acknowledged within Pakistan’s climate policies and debates, necessitating an exploration of how climate trends influence migration among marginalized rural households. There is a need for empirical evidence on the relationship between migration and adaptation, particularly in climate-sensitive areas like the Thar Desert. Further research should focus on the socio-ecological factors contributing to the resilience of households and communities under changing climatic conditions. Addressing this research gap, this study aims to answer the following research questions: (a) What are the determinants of migration decisions in Tharparkar, and what are the consequences of these decisions? (b) How effective is migration as a strategy for adapting to adverse conditions induced by climate change, and what challenges and barriers do households face in achieving a resilient lifestyle?

Concentrating on the Mithi sub-district (Tehsils/Talukas) of Tharparkar district in Sindh, Pakistan, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the penalties of climate change-induced drought for household migration decisions in the Thar Desert region. The research employs a mixed-method approach, integrating quantitative surveys with qualitative interviews. It measures the drivers and outcomes of these decisions, reviews the impact of environmental changes on households, evaluates migration pathways for adaptation to climate change, and detect challenges in adapting to these changes. This approach not only enriches on the existing body of knowledge but can also inform policy and pragmatic intervention that help build resilience among these communities prone to drought. It also provides value by combating the vulnerabilities and necessities of these desert inhabitants along with opportunities to bring more specific interventions towards this high-risk group.

Identifying the impediments to their adaptability can pave the way for strategies that heighten resilience. These research findings can be used in policy formulation and disaster management, which is essential for a country like Pakistan where climate change might escalate humanitarian crises. The present study is significant because it presents a holistic view of socio-ecological aspects while capturing migration decision-making in relation to climate change impacts among Thar communities. It explores upstream connections of environmental, livelihood, and vulnerability contexts and migration patterns across multiple tiers. These results are useful for policy interventions aimed towards successful development of resilience, such as adaptation planning, capacity building, and enhancing rural livelihood portfolios in important climate change hotspots like the Thar Desert.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for this study is founded in the intersection of migration studies, climate adaptation theory, and resilience thinking. This framework draws upon multiple theoretical perspectives to explore these aspects with respect to migration decisions and the viability of this strategy as a climate change adaptation method and also attempts challenges in enhancing resilience against climatic droughts for selected households living under the Thar Desert of Sindh Province, Pakistan. Migration theory allows for investigation of the various factors considered when making migration decisions. With this background, the present study uses the push–pull model to understand migration in Tharparkar [39]. The NELM (New Economics of Labour Migration) is further applied to examine migrations as a household strategy in order to mitigate the risks of impacts of climate change and enhance diversify income sources [40]. This theory views migration as a household decision rather than an individual choice. In this context, migration is used as a strategy to reduce household risks and diversify income. Migrants from the Thar Desert use migration as a collective strategy to enhance the household’s economic stability, particularly through remittances and shared family networks. Migration enables households to manage the risks associated with drought by securing better income opportunities and living conditions in destination areas. The study highlights how households pool resources and make collective decisions to mitigate the economic vulnerabilities posed by climate-induced drought.

Climate adaptation theory scrutinizes how households and communities adapt their lifestyles in response to unpredictable and changing weather patterns. Through the lenses of planned and autonomous adaptation [41], this study looks at migration as a form of autonomous adaption with household moving in response to unfavourable climatic conditions. By migrating, households in the Thar Desert diversify their income sources and reduce vulnerability to environmental stressors. This autonomous adaptation helps improve access to basic resources like water, food, and housing in the destination areas, thereby improving their resilience. In addition, the theory of planned behaviour further clarifies how attitudes (evaluations) and subjective norms can influence migration decisions in response to climate-induced drought [42]. This study utilizes concepts derived from resilience theory, originating in the field of ecology, as a way to better understand how households and communities will need to absorb, adjust, or transform their systems given various climate shocks and stresses. Holling (1973) states that resilience is a system’s capacity to withstand shocks while maintaining its essential functions [43]. Resilience theory is utilized in this study to assess how migration contributes to household resilience through decreasing vulnerability and increasing adaptability. The adaptive cycle model examines the dynamic processes of reorganization and adaptation during and after migration [44]. The sustainable livelihoods approach is applied to analyse migration impacts on household livelihood patterns [45,46]. According to this approach, the resources (natural, financial, and human and social capital) available to households determine their adaptive capacity against climate change. It deals with the enrichment or variation of these assets through migration to increase household resilience. Moreover, the concept of social capital [47,48] delivers valuable insights into the roles of social migrants in adapting to new communities and building resilience.

This study seeks to understand migration as an adaptation strategy to climate-induced drought by combining these theoretical perspectives. Migration theory and the sustainable livelihood approach are used to study reasons for migration; climate adaptation theory and resilience thinking is employed to analyse effectiveness of the strategy; social capital theory is explored at the individual level in terms of challenges and barriers faced while living a resilient lifestyle. This extensive theoretical framework allows a profound and multifaceted analysis of the multidirectional relationships between migration, adaptation, and resilience in the Thar Desert.

2.2. Conceptual Framework

This conceptual framework aims to elucidate the connections between the major concepts and variables underpinning this study. By integrating theoretical ideas with empirical research, the framework provides a structured approach to understanding migration dynamics as an adaptation strategy in the context of drought induced by climate change (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for this study.

The initial component of the conceptual framework looked at migration decision in Tharparkar. The Push–pull model of migration organizes these determinants into push and pull factors. Types of push factors include environmental degradation, water scarcity, agricultural failure, and socio-economic challenges, which induce households to view migration as a possible survival strategy. In contrast, pull factors are those that represent perceived economic opportunities in destination areas, such as increased standards of living, employment probabilities, and resource availability. NELM also insists on the importance of diversifying incomes and reducing vulnerability as essential household-level factors conditioning migration. The second part is designed to study the effects of migration decisions on origin and destination locations. Migration from the point of origin can cause a decrease in the workforce, a smaller population, and a potential social and economic decline. However, it can also produce remittances, which raise household incomes and contribute to community development. Migration may lead to social integration problems, cultural diversity, and stimulated economic activity in the host areas. The sustainable livelihood approach has been used to study how migration impacts various household assets (natural, financial, and human social and physical capital) and contributes to or detriments livelihood sustainability. The third component examines the effectiveness of migration as an adaptation strategy in the face of climate-induced droughts. This includes assessing the role of migration in enabling households to adapt and adjust to harmful climatic conditions. As an independent adaptive strategy, migration is then employed as a means by which households reduce the risk from climate change. The final section discusses the problems and constraints faced in realizing a resilient way of life.

The integrated conceptual model posits that migration decisions result from income-diversification strategies and vulnerability-reducing tactics at the household level, combined with push–pull factors. Migration has long-term effects on the original and destination areas. Migration is an imperative livelihood adaptation approach that can lessen household exposure, increase resource availability, and help households become more resilient. However, the effectiveness of this approach hinges on households’ capability to overcome institutional, cultural, and socioeconomic barriers. This conceptual framework offers an overarching scaffold for understanding factors shaping migration decisions and their outcomes, the effectiveness of migration as an adaptation strategy, and the challenges in achieving resilience. It informs empirical analysis and interpretation of results, providing insights into the complex dynamics among migration, adaptation, and resilience in the Thar Desert.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Descriptions of the Study Area

Pakistan, particularly the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan, is located in an arid to semi-arid climatic zone, making it highly susceptible to drought [28]. The increased temperature and low average annual rainfall exacerbate this vulnerability, particularly in the major deserts of Thar, Thal, Cholistan, and Chagi-Kharan. These areas are persistently prone to drought conditions, which have become more frequent due to pollution and climatic changes [49,50]. The province of Sindh receives only 20% of its annual rainfall during the monsoon period from June to September, with an annual average of less than 300 mm. Winter rainfall is almost negligible [36]. In 2014, Tharparkar, a district in Sindh, was severely affected by drought, resulting in significant devastation. Reports indicated 182 deaths among children under five and 149 adult deaths (91 males and 58 females), along with widespread epidemics, dehydration, malnutrition, and fever/malaria [30,49]. Additionally, 4446 children and 3910 adults suffered from abdominal issues, diarrhoea, and fever/malaria for unknown reasons [28]. According to the Sindh Relief Department, Tharparkar has been declared a calamity-hit district in 1968, 1978, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1995, 1996, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2012. Tharparkar covers over 22,000 km2, making it the largest desert in Pakistan and the 18th largest globally [30,49]. The district’s population of 1.5 million people lives in 2300 villages and urban settlements across seven talukas: Mithi, Islamkot, Chachro, Kaloi, Dahli, Diplo, and Nagarparkar. Despite its arid conditions, the land is highly fertile but relies heavily on the rainfall from July to September. Unfortunately, Pakistan’s rainfall pattern is highly variable and increasingly affected by global warming [51].

Due to remoteness and insufficient connectivity, public service contributors and other authorities often fail to extend their services to these desert regions. The residents of Thar, predominantly marginalized and impoverished, live in precarious conditions without basic amenities such as clean water, sanitation, healthcare, and education [52,53]. Employment opportunities are also limited. Their homes, typically constructed from bamboo, thatch, and mud, are vulnerable to heat and erosion, leaving them defenceless against natural disasters [54]. Deserts on all continents occupy approximately one-fifth of the Earth’s landmass. Around one-sixth of the Earth’s approximately one billion individuals reside in these regions. In Pakistan, five major deserts make up over 13.82% of the country’s area [28]. These deserts include the Thar Desert in Sindh, the Cholistan in Bahawalpur (Punjab), the Thal Desert in Bhakkar (Punjab), the Kharan Desert in Balochistan, and the Katpana Desert in Skardu (Gilgit-Baltistan). The Thar Desert, the largest desert in Pakistan, also known as the Great Indian Desert, spans 175,000 square kilometres and extends into India. The Thal Desert, located in Punjab, measures approximately 190 miles (306 km) in length and 70 miles (113 km) at its widest point. The Cholistan Desert in southern Punjab covers an area of 25,800 square kilometres (10,200 square miles). The Katpana cold desert is situated at an elevation of 7303 feet (2226 m) above sea level [28,49,50].

3.2. Setting of the Study

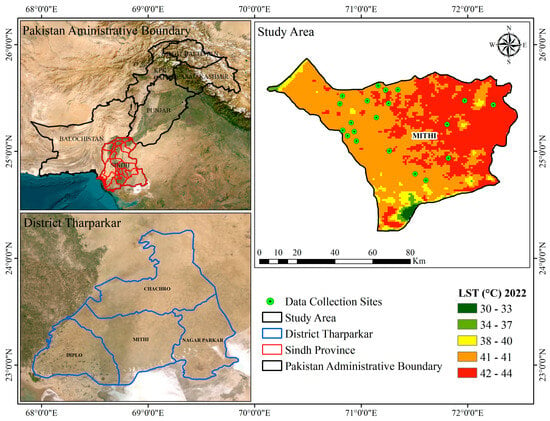

This study purposively selected the Tharparkar district in the Sindh province. The district comprises seven sub-districts (Tehsils/Talukas), one of which is Mithi (Figure 2). The selection was informed by several factors, including the number of affected individuals, casualties, and the extent of damage, as indicated by literature reviews, government reports, newspaper articles, expert opinions, and NGO documents. These locations are highly vulnerable to drought. Mithi has four Union Councils, and five villages from each Union Council were selected purposively. The selection of these villages was based on the migration patterns of the respondents. In these villages, only Hindu people live. The respondents belong to the poorest class of society, specifically the Scheduled Castes of the Hindu community. In Mithi Taluka, only these people practice seasonal migration due to climate change. Their primary sources of livelihood are agriculture and livestock. They are forced to migrate to nearby areas for agricultural labour, livestock rearing, etc.

Figure 2.

Location map of the study area.

3.3. Sampling and Data Collection

This study employed a mixed-method approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques. Quantitative data were gathered through face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaires, while qualitative data were collected via focus group discussions (FGDs), key informant interviews (KIIs), and observations. Additionally, secondary data from journals, books, and institutional websites were utilized. To enhance the reliability of the research tools, a pilot survey was conducted with 40 households, allowing for the refinement of the questionnaire by removing any extraneous or irrelevant content. The research design included two sets of structured interview schedules featuring closed and open-ended questions designed to align with the research objectives. Through purposive sampling, initial respondents were selected from four unions (each union comprising 5 villages, totalling 20 villages and 400 households). Due to the cultural norms prevalent in Pakistan, households are predominantly headed by male members. Therefore, the selected respondents were the heads of households, as they generally possess comprehensive knowledge of their family affairs.

3.4. Measuring Approach of Impacts and Consequences of Migration, and Climate Adaptation Strategy

This study measured the impacts and consequences of migration through two components: origin communities and destination communities. Various sub-factors were identified, including nine for origin communities and eleven for destination communities, and these factors were analysed on three scales: highly changing, moderately changing, and no change In contrast, two dimensions, the effectiveness and sustainability of migration, were established to evaluate migration as a climate adaptation strategy for a resilient life. Various aspects were employed under these two dimensions to assess migration as a climate adaptation strategy, considering both pre- and post-migration implications on the migrants. Furthermore, the complications and challenges of migration as an adaptation strategy were analysed through three scales: very severe, moderately severe, and less severe.

3.5. Statistical Analysis Techniques

Following the collection of diverse data types, we undertook a comprehensive analysis aligned with the objectives of our study. Quantitative data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-23) and Microsoft Excel to execute statistical computations. Descriptive analysis focused on responses from desert dwellers, addressing topics such as drought-induced migration, livelihood challenges, adaptive strategies, and the difficulties of adjusting to life in Mithi, Pakistan. We employed manual analytical techniques for qualitative data, relying on textual and document analysis to accurately interpret the information. To enhance the clarity and relevance of the data for our readers, we organized the findings into various categories, presented in tables, charts, and graphs.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profiles of Respondents

The objective of this section is to ascertain the socio-economic characteristics of the participants in the study area. This section has been developed to focus on the socio-economic conditions of individuals affected by climate change, considering factors such as age, gender, education, employment, family size, and household income. Table 1 highlights the key attributes of the migrated individuals in the study areas.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1 indicates that 51.50% of the respondents in the study villages were male while 48.50% were female. Among these respondents, 57.70% were under the age of 40, 33.50% were middle-aged, and 8.80% were elderly. Additionally, 83.50% of the participants were illiterate, whereas 9.25%, 6.25%, and 1.00% had completed primary, secondary, and higher secondary levels, respectively. Approximately 35.25% of the study population were day labourers, while around 26.5% were engaged in agriculture. Homemakers, service workers, and those in other professions accounted for 30% and 0.25% of the respondents’ occupations, respectively. The data indicated that about 22.75% of the participants belonged to large families, while 49.25% and 28% belonged to medium and small family systems, respectively. About 76.9% of families had a low monthly income, while 22.6% had a medium income. Only 0.5% of the families had a high monthly income.

4.2. Drivers and Patterns of Migration Decisions in the Thar Desert

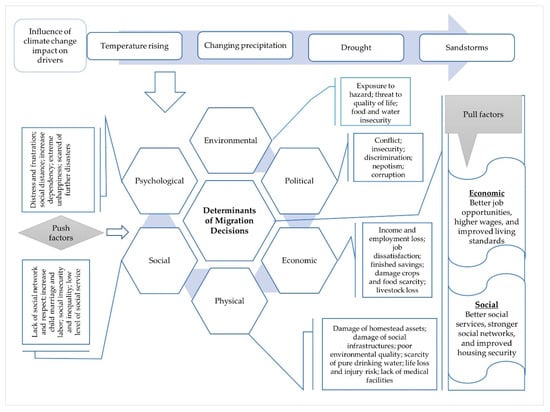

This segment illustrates the determinants and factors driving the migration of Thar Desert inhabitants from their ancestral locations. Figure 3 demonstrates the determinants of migration decisions, particularly in response to the impacts of climate change. It highlights how factors such as rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, drought, and sandstorms influence migration. These environmental changes act as drivers that directly impact people’s livelihoods and living conditions, compelling them to make migration decisions. The framework categorizes these drivers into push and pull factors, both of which are influenced by a range of interconnected dimensions, including environmental, economic, social, psychological, physical, and political factors.

Figure 3.

Determinants and factors of migration decisions in the Thar Desert. Source: Field survey.

The push factors are the negative forces that drive people to leave their current locations. Environmental factors, such as exposure to hazards and food and water insecurity, play a significant role. Economic factors like income loss, job dissatisfaction, depletion of savings, and damage to crops and livestock also push individuals towards migration. Political issues, including conflict, insecurity, and corruption, add to the pressure to migrate, while physical factors, such as the destruction of homestead assets, poor environmental quality, lack of medical facilities, and damage to social infrastructure, exacerbate the situation. Additionally, social factors, such as weak social networks and inadequate social services, make it difficult for people to stay in their current location. Psychological factors, including distress and frustration, further influence individuals’ decisions, especially when they feel hopeless or unprepared for future climate-related disasters. On the other hand, pull factors are the positive incentives that attract people to migrate to a new location. These include economic opportunities such as better job prospects, higher wages, and an overall improvement in living standards. Social factors, like improved social services, stronger social networks, and enhanced housing security, also attract individuals to migrate. Climate change-induced drought plays a crucial role in influencing these drivers and migration factors. The focus group discussions (FGDs) revealed that threats to quality of life, including lack of food and clean drinking water, unemployment and income loss, damage to homestead property, and limited educational and medical opportunities, were the primary reasons for both permanent and temporary migration from ancestral locations. In this case, a key informant interviewer stated his/her view as follows:

“The Thar Desert lacks adequate basic services. The most pressing issue is the availability of clean running water. Even when local residents manage to find freshwater sources, these areas often suffer from repeated water contamination. Consequently, people must walk miles to find freshwater, which is often unsafe to drink. This is the daily reality for many families in the region. Another critical issue is the lack of medical services. These services are provided in only a few buildings, with the nearest hospital potentially located hundreds of miles away. Additionally, education is a significant concern. While schools exist, they lack essential facilities such as decent desks, relevant books, and skilled teachers. As a result, children grow up without receiving an adequate education, limiting their future opportunities. Housing is also a major problem. Residents live in tents or small wooden houses that provide no insulation, exposing them to extreme temperatures and sandstorms. This situation perpetuates a vicious cycle, severely limiting the prospects for those living in the Thar Desert”(KII# 1).

Furthermore, qualitative findings indicated that many respondents migrated from the Thar Desert due to inadequate public services, including transportation, healthcare, education, and sanitation, along with weakened social relationships and support systems, triggering migration. The lack of access to basic facilities and sanitation services was a significant issue. Most migrants in the Thar Desert engage in circular or seasonal migration, moving to nearby areas of Tharparkar to escape water scarcity, hunger, and unemployment caused by severe and frequent droughts. However, migration poses challenges, particularly for the poor Hindu populations, due to their ancestral ties, religious commitments, livelihoods, and social networks.

For instance, significant property damage and adverse impacts on livelihoods were observed due to the drought events in 2018. A respondent expressed their perspective on this issue as follows:

“I and my family had always lived in the Thar Desert, surviving through generations on our ancestral land. We relied on the seasonal rains for our livelihood, confident that we could endure the harsh conditions. However, the drought that began in 2014 was unlike any we had ever experienced. The rains failed us for years, and our crops withered away, leaving us with nothing to harvest. Our livestock, which were our main source of income and sustenance, began to die from lack of water and food. Seeing our once-vibrant community struggle to find even a single drop of water was heart-breaking. We tried to hold on, hoping the situation would improve, but it only worsened. The relentless drought forced us to make the painful decision to leave our beloved home. We were not alone in this struggle; many of our neighbours faced the same dire circumstances. As a poor family, the displacement was devastating. We moved to a nearby town/villages, but life there was filled with uncertainties and hardships. The loss of our land and the forced migration made us more vulnerable than ever. We grappled with new challenges daily, trying to adapt to an unfamiliar environment. The sorrow of leaving our ancestral home and the struggle to survive in a new place left us in a state of constant distress”(Interviewee# 19).

Key informant interviewers revealed that the Thar Desert, located in south-eastern Pakistan, is characterized by its arid climate and harsh environmental conditions. Migration in this region is influenced by multiple factors, particularly the hypothesis that agricultural productivity shocks caused by climate change led to migration. This is due to the dependency of agrarian income on climatic anomalies. The decline in farm productivity and water-related issues are identified as major push factors. Farming activities, the primary source of livelihood in this region, are severely affected by water scarcity, making it difficult for residents to sustain their livelihoods. Consequently, limited access to water sources compels people to migrate in search of better opportunities. Additionally, variations in off-farm income, changes in perception due to weather conditions, and increased crime associated with augmented physiological aggression all have an impact on migration decisions.

On the other hand, the focus group discussions and key informant interviews (KIIs) revealed that migrants from the Thar Desert were not entirely unprepared for relocation. They often relied on informal networks and guidance from previous migrants who shared valuable knowledge about destinations, available resources, and employment opportunities. Many had prior experience with seasonal migration, which gave them an advantage. Furthermore, families consulted with relatives and community leaders before migrating, thereby enhancing their preparedness. Migration occurred both individually and in groups. While some families relocated independently, others migrated with extended families or neighbours, benefiting from shared resources and mutual support. Livestock played a crucial role in migrant livelihoods, with many families bringing their animals during migration. However, this sometimes posed challenges in securing grazing lands and water, leading to competition with host communities. In response, host communities varied in their reception of migrants. In some areas, newcomers were welcomed, whereas in others, resource scarcity led to conflicts, particularly over water and grazing lands. Nevertheless, migrants gradually integrated by relying on social networks to overcome initial hostilities.

4.3. Impacts and Consequences of Migration

Migration, typically understood as the movement of people from one area to another, has been a fundamental aspect of human life driven by economic, social, political, and environmental factors. Migration significantly impacts both the source and destination regions. These impacts can be positive or negative for those who migrate, the family members they leave behind, and the communities they join. Globally, migration can have profound economic, social, and cultural implications. It can affect demographics, social organization, labour markets, remittances, and cultural and historical aspects. Consequently, migration outcomes are multifaceted and complex, varying significantly based on previous exposure and the scale and type of migration. Some of the key economic, social, and cultural impacts include the following:

Table 2 reveals the impacts and consequences of migration on both origin and destination communities as perceived by the migrants. The migrants identified various implications for the origin communities, including population decline, changes in age structure, economic fluctuations, cultural shifts, alterations in healthcare services, and increased psychological stress. The migration patterns in the Thar Desert have led to significant changes in the origin communities. Population decline is a prominent impact, with 63% of respondents indicating a high level of change, while 26% observe moderate change, and only 11% report no change. Similarly, shifts in the age structure are evident, with 49% reporting high changes, 27% moderate changes, and 24% no changes. The economic impact is particularly striking, with 73% of respondents perceiving significant changes, while 13% report moderate impacts and 14% none. Cultural changes are less pronounced, as 19% indicate high changes, while 43% and 38% report moderate and no changes, respectively. Changes in dependency ratios are substantial, with 53% of respondents noting high changes and 37% moderate changes. Only 10% report no change. The provision of social services is also affected, with 69% observing significant changes and only 8% reporting no change. The observation and FGDs showed that the welfare structure in Tharparkar, Pakistan, is underdeveloped, with limited access to essential services like education and healthcare. Schools exist in the region, but they are severely under-resourced, lacking skilled teachers and proper facilities. As a result, educational opportunities for children are highly constrained. Similarly, healthcare services are minimal, with the nearest hospitals located far from most villages, making access challenging for the majority of migrants. This lack of adequate services exacerbates the struggles faced by migrants, particularly women and children left behind in the villages, who often bear the brunt of these deficiencies. On the other hand, healthcare remains relatively stable, with 62% of respondents noting no change. However, psychological stress levels are notably high, with 77% indicating significant impacts. Thus, migrants often experience high levels of psychological stress due to the difficulties of displacement. While the need for psychological support is recognized, there is little formal infrastructure to provide such care. Additionally, migrants do not have strong legal frameworks in place to claim support for their adaptation problems. The governance structure in Pakistan provides limited welfare or adaptation services, and there is a noticeable gap in the provision of formal psychological or legal support for migrants. Addressing these gaps would significantly improve the resilience and well-being of these populations. Finally, the political implications appear to be less affected, with 66% reporting no change. In this regard, a key informant interviewer expressed the following perception:

Table 2.

Impacts and consequences of migration in origins and destination communities.

“I’ve observed that migration brought on by drought substantially impacts the original communities in several significant ways. First and foremost, the population is clearly declining as many individuals and families relocate in search of better opportunities elsewhere. This population decline disproportionately affects the younger, more productive age groups, thereby altering the community’s age structure. The remaining population, predominantly the elderly and those in need, further strains the community’s already meager resources and social support networks. Discernible economic changes have resulted from this migration. Local economic activity has decreased due to the departure of economically active individuals. This economic downturn exacerbates poverty in these areas and restricts funding for resilience-building and community development. The social impacts are equally significant. While some families relocate together, migration often splits communities and families, with younger individuals leaving behind the elderly and children. This loss weakens the social fabric and communal ties, as cultural and traditional practices diminish. Those left behind suffer greatly psychologically, coping with the loss of family members and an uncertain future. Nevertheless, migration, whether temporary or permanent, remains the most significant strategy for coping with adverse conditions in this region. As a result, they can somewhat combat the crisis situation and try to rebuild their lives”(KII# 3).

Conversely, nearly all respondents perceived significant changes in the destination communities across multiple dimensions. These changes included increased demand for housing, healthcare services, education systems, skill development, social and cultural diversity, energy, and utilities. Increased demand for housing is a moderately changing factor, with 31% reporting high changes, while 46% observe no changes. Transportation and mobility are moderately impacted, with 36% observing high change, 41% moderate change, and 23% no change. The strain on healthcare services is substantial, with 71% of respondents indicating significant changes, while education systems are also considerably impacted, with 62% reporting high changes. In contrast, public safety and law enforcement have seen minimal changes, as 49% report no change. Changes in energy and utilities are moderate, with 43% noting high change. Regarding the economic burden, 34% perceive high changes, but 25% report no change. Skill development remains largely unaffected, as 54% report no change. Similarly, challenges in integration and social cohesion are less significant, with 51% observing no change. Labor market impacts, however, are prominent, with 67% of respondents noting high changes. Lastly, social and cultural diversity has increased notably, with 84% observing high changes.

“I have lived in the Thar Desert for a long time and am well-acquainted with the harsh realities of droughts exacerbated by climate change. Maintaining our traditional way of life has become increasingly difficult due to severe droughts’ rising frequency and intensity. The water shortage and its subsequent impacts on agriculture and livestock—our primary sources of income—have forced my family and me to adapt in various ways. One significant adaptation strategy we have employed is seasonal migration. During the worst drought periods, we relocate to neighbouring areas where water and grazing land are more readily available. This decision is not made lightly, as it entails leaving behind our community and home and sometimes even disrupting our children’s education. However, it is necessary to ensure our survival and the well-being of our livestock”(Interviewee# 27).

The findings from the FGDs demonstrated that migration has both advantages and disadvantages. Finding suitable places to move to is often challenging, as many other families from our region also seek the same resources. Competition for water and grazing land can occasionally lead to confrontations with local communities in the areas we migrate to. Additionally, the transient nature of our stay means we must constantly adjust to new situations and rebuild our lives each time we move. Despite these limitations, migration has provided us with a crucial lifeline during a catastrophic drought. It allows us to preserve our animals, which are essential for our livelihood, and provides some stability until conditions improve back home. Over time, we have established a network of contacts in numerous citizenries, which helps us identify ideal places to migrate to and secure support during our stay. We have faced recurring droughts for decades, which has led to an established practice of seasonal migration. Many families have developed coping mechanisms over time, including shared knowledge of migration routes and strategies for survival as migrant workers.

4.4. Evaluating Migration as a Climate Adaptation Strategy

The findings from the field survey reveal that inhabitants of the Thar Desert employ various adaptation strategies to cope with the severe conditions caused by climate-induced drought. Among these strategies, migration stands out as one of the most prevalent in the study area. All respondents reported having migrated multiple times to nearby places throughout their lives. A key informant highlighted that migration is increasingly recognized as a crucial strategy for adapting to the negative impacts of climate change. People typically migrate from vulnerable areas such as deserts and coastal regions, which are at high risk for sandstorms, surges, and erosion. While some findings, such as the push–pull factors driving migration, may seem intuitive, they are grounded in the theoretical framework of adaptation and migration theories. These theories provide a structured analysis of the challenges and barriers faced by migrants, going beyond common-sense explanations. For instance, the study’s analysis of the impact of climate adaptation through migration incorporates resilience theory to assess how households manage social, economic, and institutional challenges at both the origin and destination. Despite several disadvantages, migrants often find various forms of facilitation in their new locations. The following table assesses migration as a climate adaptation strategy for achieving a resilient life, aiming to uncover the implications of migration on Thar Desert dwellers from both pre- and post-migration perspectives.

The analysis of migration as a climate adaptation strategy reveals several significant findings across different dimensions, encompassing pre-migration and post-migration scenarios and their implications. The data presented in Table 3 indicate that, in most cases, people who migrated from the Thar Desert experienced better conditions in the post-migration period. In terms of the effectiveness of migration, employment opportunities and income levels are comparatively higher and more stable than before migration. Furthermore, migration has led to the diversification of income sources and increased job stability. Similarly, access to clean water, food, and housing has improved compared to the previous location. Migrated individuals no longer struggle to meet their primary needs after relocation, resulting in reduced health risks and improved living conditions. Additionally, there is a noticeable reduction in exposure to environmental hazards. However, it is noted that social community ties in the new location are somewhat weaker compared to those in the original location. Despite this, the new place provides opportunities to build new support networks that offer both emotional and practical support, which aids in successful adaptation. One respondent shared his/her experience, highlighting the impact of these new support systems:

Table 3.

Key findings on assessing migration as a climate adaptation strategy.

“Back in our village, our community was close-knit, and everyone knew each other well. Moving to this new place, I initially felt isolated and disconnected. But gradually, I started meeting new people who were incredibly supportive. They helped me navigate the new surroundings, offered emotional comfort during difficult times, and provided practical assistance, such as finding work and accessing local resources. These new connections have been crucial in helping me adapt and feel more at home in this new place”(Interviewee# 43).

These communities faced significant challenges due to widespread resource depletion and environmental deterioration. Environmental and economic uncertainties resulted in suboptimal health outcomes and elevated stress levels. Improved skill acquisition and better access to resources enhanced adaptive capacity, which, in turn, increased resilience. The demand for sustainable resource management practices is underscored by the fact that migration also increased the strain on resources in destination locations. Economic sustainability improved with reduced reliance on agriculture and diversified income sources. Enhanced living conditions and stability led to decreased stress levels and improved health among migrants. Mental health care services have become crucial for the well-being of migrants. Improved conditions and reintegration support bolstered the viability of return migration, highlighting the necessity of policies that include financial incentives, housing assistance, and community reintegration initiatives. Overall, migration improved living standards, job security, and income diversification, demonstrating its efficacy in coping with climate change while emphasizing the need for comprehensive policies to facilitate social integration and address environmental repercussions.

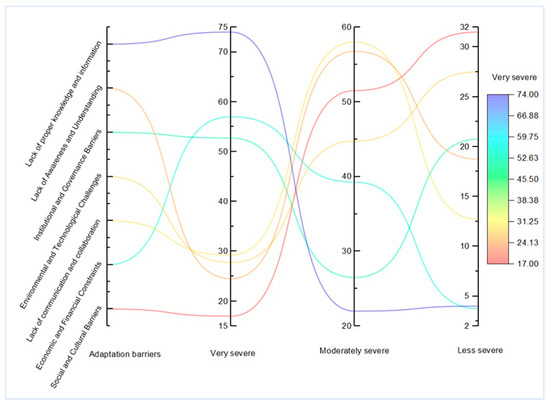

On the other hand, the inhabitants of the Thar Desert who migrated due to climate-induced drought adopted migration as a climate adaptation strategy to mitigate their dire circumstances. They identified several constraints hindering this adaptation strategy. Although this approach has been proven to be highly significant for addressing their challenges, providing seasonal and permanent support during critical times when hope and assistance were essential, several obstacles remain. Figure 4 illustrates the components of these adaptation obstacles that impede the resilience of the migrated population.

Figure 4.

Barriers factors in migration as an adaptation strategy for resilient life. Source: Field survey.

Figure 4 identified the most common barriers to migration as an adaptation strategy, including lack of proper knowledge and information, lack of awareness and understanding, institutional and government barriers, environmental and technological challenges, lack of communication and collaboration, economic and financial constraints, and social and cultural barriers. Among these, 57%, 52.7%, and 74% of migrants found that economic and financial constraints, institutional and government barriers, and lack of proper knowledge and information were the most severe obstacles to developing resilient livelihoods. In this case, a respondent opined his/her perception as follows:

“I am a poor man from the Thar Desert. I used to live in a small village and worked as a farmer. I did not own any cultivable land except for my small homestead. For a while, we were content as a family, but our happiness ended abruptly due to the relentless drought. The lack of rain and water made cultivating the land around us impossible, which was the primary source of livelihood for many in our community. Without the ability to grow crops, our food supply dwindled, and we faced severe hardships. The drought destroyed not only our homestead but also the little agricultural activity we could manage on our small plot. With no cultivable land left and our household assets gone, we were forced to leave in search of a new place to live. We searched desperately but couldn’t find any suitable land near our home. Eventually, we settled here, but our struggles have continued. The scarcity of cultivable land has massively disrupted our lives, making it difficult to rebuild and sustain ourselves. The drought took away our homes and our means of making a living. The lack of cultivable land has stripped us of our ability to grow food and earn an income. Adapting to this new reality has been incredibly difficult, and the impacts of the drought still weigh heavily on us every day”(Interviewee# 13).

However, a key informant observed that migration is not a long-term solution. It is a temporary measure that addresses immediate needs but does not solve the underlying problem of climate change and water scarcity. We need more sustainable solutions, such as improved water management, drought-resistant crops, and better infrastructure, to ensure the long-term resilience of our community. Furthermore, FGDs revealed that while seasonal migration has been a vital adaptation strategy for families, it is fraught with challenges and uncertainties. We continue to hope for more permanent and sustainable solutions.

5. Discussion

Climate change-induced drought has widespread impacts on inhabitants of arid and semi-arid regions globally. The people of the Thar Desert in Pakistan face numerous challenges due to climatic variability, which increases the severity and occurrence of catastrophes like drought [54]. Field observations in the Tharparkar district revealed that nearly all residents are affected by climate change and its associated hazards. Consequently, they encounter significant challenges to their lives and livelihoods and struggle to manage during crises, similar to findings in other regions [55,56,57]. The study area’s residents are generally not well-educated and have lower educational attainment than the national average, combined with unstable employment [58]. This lack of stability often leads residents to migrate to nearby areas less affected by drought as an adaptation strategy. Warner et al. (2010) support the notion that migration can effectively adapt to climate variability and extreme weather events [59]. This tendency is common in hazard-prone areas worldwide. In contrast, Tharparkar inhabitants have limited adaptation options beyond migration, leading to seasonal migrations almost every time a catastrophe occurs.

The study identified six push factors and two pull factors as primary drivers of migration in the Tharparkar region, with climate change-triggered drought significantly influencing these drivers. Frequent droughts, water shortages, and crop losses were the core reasons for escalating migration in the Mithi sub-district. Similar findings were reported by Zaman (1989) and Alam et al. (2020), who noted rising internal migration in disaster-prone regions due to such catastrophes [60,61]. Research shows that environmental degradation, such as rising temperatures and drought, directly impacts livelihoods, particularly in agriculture-dependent communities, driving migration due to food and water insecurity [62,63]. Economic factors like job loss, depleted savings, and damaged crops are major push factors, as highlighted by studies focusing on rural migration to urban centres in search of better opportunities [64,65]. Financial difficulties, as examined by Barua et al. (2017), are also soundly related to internal migration in developing nations [66]. Environmental factors are pivotal in influencing migration decisions globally, as noted by Black et al. (2013), mirroring the drought-induced migrations in the Thar Desert [67]. Seasonal migration was obtained to be increasing due to livelihood loss and agricultural damage. Social services and livelihood opportunities were observed to improve between former and current locations post-migration. Islam and Hasan (2016) and Kabir et al. (2018) highlighted that vulnerable people sought to relocate to developed areas with better communication systems, drinking water accessibility, and flood living quarters [68,69].

This study concludes that migration as an adaptation measure has both positive and negative impacts on origin and destination places. These findings are not entirely dissimilar from other research conducted worldwide but reveal some unique aspects, such as age structure changes, labour market dynamics, economic fluctuations, psychological stress, and healthcare facilitation, particularly for desert dwellers [70,71]. Migrants often face housing crises and pressure on energy and health services in destination areas, aligning with research by other scholars [72]. Black et al. (2013) highlighted that migration often responds to environmental stressors, including droughts and water scarcity, consistent with the drivers identified in the Thar Desert [67]. Seasonal migration is the primary strategy to cope with adverse conditions in these areas. Despite some disadvantages, migration benefits Tharparkar residents, as this study concluded through pre- and post-migration analysis. Migration was found to be more effective and stable than before. Hossain et al. (2022) argued that migration could initially help vulnerable people find their way of life [63]. Although social community ties may weaken in new locations, migrants can build new networks that aid adaptation, a finding similar to Reference [63]. Migration also helps drought-affected people become more sustainable through diverse income sources, enhanced adaptive capacity, and improved health facilities. Identifying hindrances to adaptation in the face of climate change is indispensable for fabricating adequate livelihood coping mechanisms [73]. Financial instability is a significant barrier, reducing adjustment capabilities [67]. Similarly, monetary crises are pivotal barriers for migrants in the Thar Desert. Most respondents work as day labourers and farmers and report impediments such as lack of knowledge, information, and disrupted livelihood coping, consistent with findings by Reference [68].

This study distinctively focuses on the Thar Desert, detailing the socio-economic features of migrants and specific push and pull factors influencing their decisions, while existing literature has mainly discussed climate-induced migration. Unlike general studies, this research integrates qualitative insights from focus group discussions and interviews, offering a nuanced understanding of migrants’ lived experiences. Furthermore, the study evaluates migration as a strategic adaptation to climate variability, comprehensively analysing its effectiveness and sustainability. Therefore, this study’s findings have noteworthy policy implications for countries facing similar issues. The outcomes have burning implications for national policy priorities such as poverty reduction, improving conditions for the ultra-poor, and providing definite support for socially omitted individuals. Addressing severe poverty in disaster-prone areas like the Thar Desert is crucial for poverty alleviation strategies. Governments recognize that relocated people in disaster-prone regions are severely disadvantaged due to a lack of land rights, access to formal finances, and other essential services [69]. The purpose of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to lessen extreme poverty in rural areas. For instance, in the Thar Desert, relevant authorities can employ successful interventions from other arid regions to obtain a good insight into what needs to be done in the future about sustainability. Water conservation practices used in the Sahel region of Africa provide a model for improving water resource management in the Thar Desert [73,74]. Furthermore, community-led development projects which seek to develop renewable energy and sustainable agriculture could help build resilience against droughts and climate variability in the long-term. Thus, mapping the socio-economic vulnerabilities and other risk factors faced by desert dwellers and migrants is essential for enhancing their resilience and adaptation capabilities. Potential disaster resilience models should be put together to outline institutional systems, measures, and operational conditions in the aftermath of catastrophes. The study’s outcomes indicate that due to limited human and economic assets, respondents had no choice but to relocate to nearby areas.

6. Conclusions

This study conducted in the Thar Desert of Pakistan provides a thorough analysis of migration as a climate adaptation strategy in response to the deteriorating impacts of climate-induced droughts. The research findings reveal that the harsh environmental conditions, coupled with the lack of essential services such as clean drinking water, food security, healthcare, and employment opportunities, have made life increasingly unsustainable for local residents. Migration has emerged as a primary coping mechanism, allowing households to escape the immediate impacts of drought while seeking better livelihoods and access to resources in destination areas. The study highlights several critical factors driving migration decisions, including environmental degradation, economic instability, and the breakdown of social and healthcare services in the origin communities. Migrants reported significant changes in their origin communities, such as population decline, altered age structures, and increased psychological stress due to family separation. At the same time, destination communities experienced heightened pressure on housing, healthcare, education, and utilities as they absorbed the incoming populations. Despite these challenges, migration provided notable benefits, including more stable employment, diversified income sources, and improved access to water, food, and housing. These improvements reduced health risks and enhanced the overall living conditions of migrants.

However, migration as an adaptation strategy also faces significant barriers, such as limited access to information, institutional support, financial resources, and technological advancements. These constraints hinder the ability of migrants to build sustainable and resilient livelihoods in their new environments. Moreover, the environmental degradation in destination areas exacerbates the strain on already limited resources, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability of migration as a solution. The findings underscore the importance of developing comprehensive policy interventions that address both the root causes of migration and the challenges faced by migrants in their new communities. Policies aimed at improving water management, promoting drought-resistant agricultural practices, and enhancing public services are critical for both origin and destination areas. Additionally, greater institutional support and investment in social services will be essential to enhancing the adaptive capacity of vulnerable populations in regions like the Thar Desert.

This research contributes to the broader understanding of migration as a complex and multifaceted adaptation strategy that encompasses economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Examining both pre- and post-migration conditions provides valuable insights into the factors that shape migration decisions and the outcomes of migration as a response to climate change. While migration offers temporary relief, the study highlights the need for more sustainable, long-term solutions to build resilience in both origin and destination communities. Future research should explore longitudinal trends in migration to better understand its long-term effectiveness as a climate adaptation strategy.

Author Contributions

A.H. and B.H. conceptualized and initiated the study. A.H., G.S. and B.H. designed the research plan, collected data, analysed data, and wrote the manuscript. A.H., B.H. and G.S. analysed data and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Key Research Project of National Foundation of Social Science of China, Community Governance and Post-relocation Support in Cross District Resettlement (Fund no. 21 and ZD 183).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all study participants for their cooperation and willingness to take part in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hossain, B.; Shi, G.; Ajiang, C.; Sohel, M.S.; Yijun, L. Social Vulnerability, Impacts and Adaptations Strategies in the Face of Natural Hazards: Insight from Riverine Islands of Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Mueller, V. Coastal Climate Change, Soil Salinity and Human Migration in Bangladesh. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, N.; Cameron, L.; Mauro, I.; Friesen-Hughes, K.; Rocque, R. Perceptions of the Health Impacts of Climate Change among Canadians. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suriya Tajrin, M.; Hossain, B. The Socio-Economic Impact Due to Cyclone Aila in the Coastal Zone of Bangladesh. Int. J. Law Hum. Soc. Sci. 2017, 1, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, B.; Shi, G.; Sarker, M.N.I. Living with Floods in Bangladesh’s Riverine Islands: Understanding Vulnerability and Resilience; B P International: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Malhi, Y.; Franklin, J.; Seddon, N.; Solan, M.; Turner, M.G.; Field, C.B.; Knowlton, N. Climate Change and Ecosystems: Threats, Opportunities and Solutions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, M. Estimation of Biomass and Soil Carbon Stock in the Hydroelectric Catchment of India and Its Implementation to Climate Change. J. Sustain. For. 2022, 41, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, R.; Jia, S.; Babel, M.S. Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Water Resources in the Kunhar River Basin, Pakistan. Water 2016, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mishra, S.; Bakshi, S.; Upadhyay, P.; Thakur, T.K. Response of Eutrophication and Water Quality Drivers on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Lakes of China: A Critical Analysis. Ecohydrology 2023, 16, e2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, G. Adaptation to Climate Change. In Environmental Medicine; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, M.A.; Kumar, M.; Todaria, N.P.; Bhat, J.A.; Kumar, A.; Pandey, R. Contribution of Cedrus Deodara Forests for Climate Mitigation along Altitudinal Gradient in Garhwal Himalaya, India. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2021, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, T.; Milan, A.; Etzold, B.; Schraven, B.; Rademacher-Schulzb, C.; Sakdapolrak, P.; Reif, A.; van der Geest, K.; Warner, K. Human Mobility in Response to Rainfall Variability: Opportunities for Migration as a Successful Adaptation Strategy in Eight Case Studies. Migr. Dev. 2016, 5, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A.; Zhao, T.; Chen, J. Climate Change and Drought: A Precipitation and Evaporation Perspective. Curr. Clim. Chang. Rep. 2018, 4, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahta, Y.T. Nexus between Coping Strategies and Households’ Agricultural Drought Resilience to Food Insecurity in South Africa. Land 2022, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, A.T.; Zaki, N.A.; Rossi, P.M.; Noori, R.; Hekmatzadeh, A.A.; Saremi, H.; Kløve, B. Unsustainability Syndrome-from Meteorological to Agricultural Drought in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Water 2020, 12, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Shah, S.F.; Uqaili, M.A.; Kumar, L.; Zafar, R.F. Forecasting of Drought: A Case Study of Water-Stressed Region of Pakistan. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, E.; Schipper, L.; Simonet, C.; Kubik, Z. Climate Change, Migration and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; ODI: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koubi, V.; Spilker, G.; Schaffer, L.; Bernauer, T. Environmental Stressors and Migration: Evidence from Vietnam. World Dev. 2016, 79, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzoska, M.; Fröhlich, C. Climate Change, Migration and Violent Conflict: Vulnerabilities, Pathways and Adaptation Strategies. Migr. Dev. 2016, 5, 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederkehr, C.; Beckmann, M.; Hermans, K. Environmental Change, Adaptation Strategies and the Relevance of Migration in Sub-Saharan Drylands. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomeo, E.; Jagerskog, A.; Talbi, A.; Wijnen, M.; Hejazi, M.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus in the Middle East and North Africa; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heshmati, G.A.; Squires, V.R. Combating Desertii Cation in Asia, Africa and the Middle East Proven Practices; Springer Science & Business: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.H. Investigation of Mechanisms to Detect Recurrence of Droughts in South Asia with Special Reference to Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology Islamabad-Pakistan, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, M.H.; Aamir, N.; Ahmed, N. Climate Change and Drought: Impact of Food Insecurity on Gender Based Vulnerability in District Tharparkar. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2018, 3, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Nichol, J.E. A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Rainfall and Drought Monitoring in the Tharparkar Region of Pakistan. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.A.; Ashraf, E.; Shurjeel, H.K.; ud Din Mirani, Z.; Rafique, U.; Shah, R.A. Assessing Perceptions of the Households-Heads Regarding Food Security Status in Drought-Hit Areas of District Tharparkar, Sindh, Pakistan: A Case Study for Agricultural Extension. Sarhad J. Agric. 2020, 36, 1162–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Wajid, M.; Safi, A. Assessing the Socio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of 2014 Drought in District Tharparkar, Sindh-Pakistan. Int. J. Econ. Environ. Geol. 2017, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, V.; Gray, C.; Kosec, K. Heat Stress Increases Long-Term Human Migration in Rural Pakistan. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.A.; Zhang, S.; Muneer, M.; Moawwez, M.A.; Kamran, M.; Ahmed, E. Assessing and Mapping Spatial Variation Characteristics of Natural Hazards in Pakistan. Land 2023, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickgraf, C.; Ionesco, D. The State of Environmental Migration 2015; IOM (International Organization for Migration): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salik, K.M.; Shabbir, M.; Naeem, K. Climate-Induced Displacement and Migration in Pakistan Insights from Muzaffargarh and Tharparkar Districts; Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI): Islamabad, Pakistan; Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA): Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, S. Understanding the Impacts of Climate Change on Water Access and the Lives of Women in Tharparkar District, Sindh Province, Pakistan: A Literature Review, 1990–2018. 2019. Available online: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/items/d0a075a4-f05d-496e-a7ea-4f8305e9ce05 (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Azhar, M.F.; Faiz, M.J.; Ali, E.; Aziz, A.; Akbar, M.; Raza, G.; Abdullah, M.; Habib, M.M.; Akram, M.F. Evaluation of Drought Hazards and Coping Strategies Adopted by Pastoral Communities in the Cholistan Rangeland of Pakistan. Environ. Dev. 2024, 50, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Khan, M.; Parveen, T.; Hussain, S. Impacts of Climate Change in Vulnerable Communities in Sindh, Pakistan: Voices from the Community; Population Council: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.P. Effect of Climate Change on Health in Pakistan. Pak. Acad. Sci. 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S. A Theory of Migration. Demography 1966, 1, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oded Stark, B.; Bloom, D.E. The New Economics of Labor Migration. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, Adaptive Capacity and Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S.; Gunderson, L.H. Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Conway Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Falmer, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, P.B. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Harraka, M. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, by Robert D. Putnam. J. Cathol. Educ. 2002, 6, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Atif, I.; Mahboob, M.A. Spatio-Temporal Mapping of Tharparkar Drought Using High Resolution Satellite Remote Sensing Data. Sci. Int. 2016, 28, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, M.; Liaqat, M.U.; Cheema, M.J.M.; Mahmood, T.; Khan, Q. Spatial Drought Monitoring in Thar Desert Using Satellite-Based Drought Indices and Geo-Informatics Techniques. Proceedings 2017, 60, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A. Climate Change and Migration. Exploring the Linkage and What Needs to Be Done in the Context of Pakistan; LEAD Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.A.-Q. Drought in Tharparkar: From Seasonal to Forced Migration. State Environ. Migr. 2015, 19, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Khuhro, T.; Ahmed Shaikh, F. The Socioeconomic Effects of Drought: A Case Study of Tharparkar. Sci. Int. 2022, 34, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Talpur, M.A.; Akhtar Mari, S. Seasonal Migration in Tharparkar District of Sindh Province, Pakistan: An in-Depth Empirical Analysis. Pak. J. Appl. Econ. 2021, 31, 209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, H.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A. Climate Change and Human Migration: Perspectives for Environmentally Sustainable Societies. J. Geochem. Explor. 2024, 256, 107352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.N.I.; Wu, M.; Alam, G.M.M.; Shouse, R.C. Livelihood Vulnerability of Riverine-Island Dwellers in the Face of Natural Disasters in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monirul Alam, G.M. An Assessment of the Livelihood Vulnerability of the Riverbank Erosion Hazard and Its Impact on Food Security for Rural Households in Bangladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. PAKISTAN. 2017. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/536431495225444544/pdf (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Warner, K. Global Environmental Change and Migration: Governance Challenges. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.Q. The Social and Political Context of Adjustment to Riverbank Erosion Hazard and Population Resettlement in Bangladesh. Hum. Organ. 1989, 48, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.M.; Alam, K.; Mushtaq, S.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Hossain, M. Hazards, Food Insecurity and Human Displacement in Rural Riverine Bangladesh: Implications for Policy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 43, 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Hess, J.J. Health Risks Due to Climate Change: Inequity in Causes and Consequences. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2056–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, B.; Shi, G.; Ajiang, C.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Sohel, M.S.; Sun, Z.; Yang, Q. Climate Change Induced Human Displacement in Bangladesh: Implications on the Livelihood of Displaced Riverine Island Dwellers and Their Adaptation Strategies. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 964648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boas, I.; Wiegel, H.; Farbotko, C.; Warner, J.; Sheller, M. Climate Mobilities: Migration, Im/Mobilities and Mobility Regimes in a Changing Climate. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 3365–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, B.; Ryakitimbo, C.M.; Sohel, M.S. Climate Change Induced Human Displacement in Bangladesh: A Case Study of Flood in 2017 in Char in Gaibandha District. Asian Res. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, P.; Rahman, S.H.; Molla, M.H. Sustainable Adaptation for Resolving Climate Displacement Issues of South Eastern Islands in Bangladesh. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 9, 790–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Arnell, N.W.; Adger, W.N.; Thomas, D.; Geddes, A. Migration, Immobility and Displacement Outcomes Following Extreme Events. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 27, S32–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Hasan, M. Climate-Induced Human Displacement: A Case Study of Cyclone Aila in the South-West Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2016, 81, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.E.; Serrao-Neumann, S.; Davey, P.; Hossain, M.; Alam, M.T. Drivers and Temporality of Internal Migration in the Context of Slow-Onset Natural Hazards: Insights from North-West Rural Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, C.K.; Gupta, V.; Chattopadhyay, U.; Amarayil Sreeraman, B. Migration as Adaptation Strategy to Cope with Climate Change: A Study of Farmers’ Migration in Rural India. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 10, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhin, S.; Khankeh, H.; Farrokhi, M.; Aminizadeh, M.; Poursadeqiyan, M. Migration Health Crisis Associated with Climate Change: A Systematic Review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemayehu, A.; Bewket, W. Smallholder Farmers’ Coping and Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change and Variability in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Ekstrom, J.A. A Framework to Diagnose Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22026–22031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikuze, A.; Sliuzas, R.; Flacke, J.; van Maarseveen, M. Livelihood Impacts of Displacement and Resettlement on Informal Households—A Case Study from Kigali, Rwanda. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Islam, M.R. Ultra-Poor Char People’s Rights to Development and Accessibility to Public Services: A Case of Bangladesh. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]