Abstract

The southwest coast, specifically the Khulna region of Bangladesh, has seen a substantial increase in the production of dried fish, involving marginalized coastal people. This study uses a mixed methods approach and the sustainable livelihood approach (SLA) to assess these fish-drying communities’ socioeconomic characteristics, ways of living, and adaptability. Due to their lower literacy, irregular wages, and labor-intensive employment, the research outcomes indicated that the communities engaged in the drying process were economically disadvantaged. Male workers exhibited a relatively higher participation rate compared to females. However, it was observed that females had less power over their wages and earned less than USD 2.74–3.65 per day compared to males at USD 3.65–5.48 per day. Even though there were a lot of opportunities for employment, the survey showed that very few vendors, manufacturers, and laborers regarded themselves as financially independent. To cope with various impacts and obstacles, off-season earnings, a variety of fish species, drying facilities, dealer associations, and social relationships were crucial for dried-fish processors, workers, and traders. The research suggests implementing suitable measures to diversify alternative sources of income and emphasizes the importance of fostering strong collaboration among the communities, local management authorities, and the government. With regard to dry-fish approaches, these steps are essential for ensuring long-term sustainability and improving community resilience among coastal communities.

1. Introduction

Fisheries represent a vital component of Bangladesh’s agriculture, serving as a critical driver for sustainable progress and the economic well-being of individuals engaged in fish and dried-fish production or processing. Because of its delicious flavor, texture, and taste, dried fish is the most popular type of fish consumed in Bangladesh [1], which constitutes the fourth largest part of all forms of fish [2]. Being affordable and economical, dried fish is a readily available food option, offering substantial protein and essential micronutrients to impoverished individuals’ diets [3]. The widespread practice of fish drying along Bangladesh’s coastline is vital for subsistence and livelihoods, especially for poor coastal and inland people [4]. In Bangladesh, these endeavors hold significant value, supporting over 17 million individuals who rely on fish-related activities like farming, processing, and handling [5]. After harvest, more than one-third of the catches are used for year-round drying [6,7], an essential financial security source for many coastal residents.

The manufacturing and commerce of dry fish are emerging as a lucrative and encouraging business. Dealers, manufacturers, retailers, and other customers have the potential to make significant earnings from fisheries through this particular sector. Even though there is a global financial crisis, the country made USD 472,802,463.25 in 2021–22 by selling almost 7404 thousand MT of fish and dried-fish goods. This is because the present government has taken practical steps [8]. It is regrettable that the importance of dried fish and individuals involved in its production, both directly and indirectly, are still undervalued in light of global food security and the welfare of small-scale fisherman in emerging nations [1]. Hence, investigating socioeconomic status and community resilience becomes vital, shedding light on local conditions and individuals’ roles within society in economic and social terms. This understanding leads to appropriate interventions for community management.

The fish-drying community along the southwest coast heavily depends on weather conditions for their process. However, the adverse effects of climate change pose significant challenges at local, national, and global scales. This impacts the sustainability of various aspects, including aquatic environments, ecosystems, and the communities reliant on them [9,10,11,12]. Climate fluctuations impact the economies and livelihoods of communities involved in processing and trading dried fish. These communities, in turn, face susceptibility to severe weather conditions such as heavy rainfall and overcast conditions. [13].

There are several research papers on the socioeconomic situation of Bangladeshi fishermen [14,15,16,17,18]. However, there has been little research conducted on fish-drying communities other than their economic status, which includes things like welfare of workers in dried-fish value chains [1], the efficiency of dry-fish marketing [6], and evaluation of the quality of dried fish [19]. Thus, this study aims to evaluate the socioeconomic status and pivotal resilience factors for communities engaged in fish drying along Bangladesh’s southwest coast. The outcomes of this study will assist the chosen communities, various organizations, and governmental agencies create measures that will improve the socioeconomic circumstances of fish-drying communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

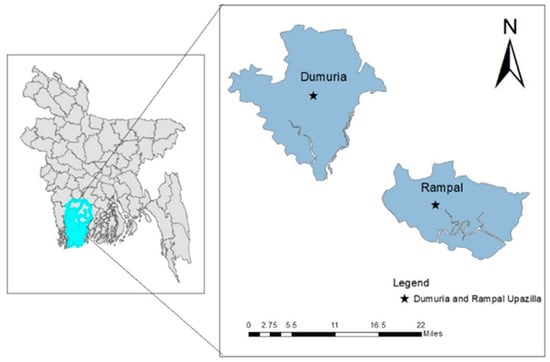

This study was conducted in areas of the southwest coast where fish are dried: Dumuria (within the Khulna district) and Rampal (within the Bagherhat district) (Figure 1). The primary basis for choosing these regions was the communities’ dependence on fish drying. Dumuria is the upazila of Khulna district. For the next eight to nine months, dried fish will continue to be produced utilizing solar energy. Conventional solar energy techniques are employed to dry larger fish species like Churi, Loitta, Faisha, Poa, Shapla, and Surma on a larger scale. The drying procedure is mainly carried out inside Khola (a local word for the processing of fish area), where fresh fish are stretched out on bamboo sheets on the ground or placed on wood scaffolds or racks to dry. On the other hand, Rampal is the upazila of the Bagerhat district. In this area, simple methods are used to dry fish on rooftops. Bamboo shelves and solar power are used for this purpose. Additionally, they create dried fish, salted-dried fish, and valuable by-products like fins and swim bladders. These products are highly sought after not just by nearby nations but also among indigenous groups.

Figure 1.

Map showing the study areas on the southwest coast of Bangladesh.

2.2. Study Approach and Empirical Data Collection Methods

Between July and December 2022, 250 individuals involved in drying fish, including processors, workers, and traders, were randomly selected from Dumuria (N = 190) and Rampal (N = 60) to participate in the research. The study utilized a mixed methodology involving semi-structured questionnaire-based individual interviews (N = 250), interviews with 15 key informants, and ten focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted with predefined checklists (Table 1). We used a sustainable livelihood framework (SLA).

Table 1.

An overview of the procedures used to acquire empirical data.

An in-person survey involving 250 participants was conducted after creating a semi-structured questionnaire. The research examined a range of socioeconomic variables that are thought to reflect the means of subsistence, financial status, and food security of those engaged in drying fish. During the interviews, various qualitative data were collected by inquiring with communities about their range of livelihoods, challenges, vulnerabilities, and strategies to manage financial difficulties and seasonal changes within communities. Furthermore, gathering information on dried-fish processing and trade, preservative usage, hygiene, sanitation, and public health concerns was facilitated through direct observations and interviews with essential sources: processors, traders, and drying workers. Hence, a content analysis technique was utilized to analyze this qualitative data. This method involves interpreting and categorizing various forms of information, such as documents, articles, interviews, and images, through classification, tabulation, and assessment [20]. Subsequently, qualitative and quantitative data were input into Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet 2016 and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 25. This analysis included descriptive statistics and the chi-square test.

2.3. Secondary Data Collection

Secondary data were gathered from relevant literature, scholarly publications, and books that have been published. This information was acquired through online searches, including platforms like Google Scholar.

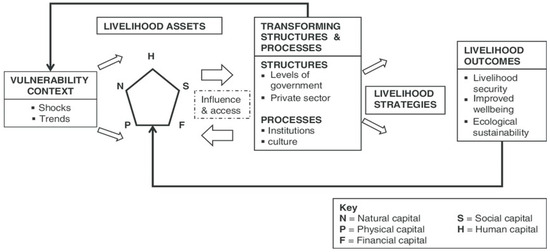

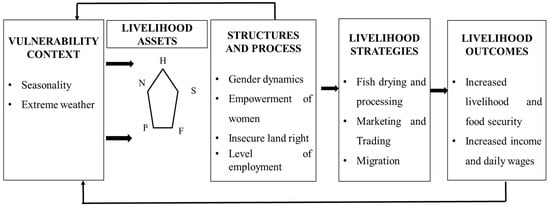

2.4. Sustainable Livelihood Framework

To comprehend the resilience of fish-drying communities and their reliance on existing resources, we employed the ‘Sustainable Livelihood Approach’ (SLA) (Figure 2). The SLA provides a means of comprehending the requirements of the impoverished and pinpointing notable challenges and advantageous factors that contribute to their resilience [21]. According to the sustainable livelihood framework, a livelihood centered around fishing involves various elements: (a) livelihood assets (resources owned or accessed by individuals, such as human, financial, physical, natural, and social capital); (b) the context of vulnerability (risk factors influencing livelihoods); (c) altering structures and procedures (formal organizational structures like government, NGOs, laws, rights, social interactions, and engagement); (d) livelihood strategies (varied activities undertaken to fulfill livelihood goals, including productive endeavors and investment strategies); and (e) livelihood outcomes (attainment or yield resulting from individuals’ livelihood strategies) [22]. By conducting open-ended interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs), extensive insights were acquired concerning the access to diverse forms of capital, approaches to livelihood, decision-making procedures, local establishments, and their capacity to adapt to shifting vulnerability circumstances. Key themes were identified and organized into manageable categories of distinct variables: physical and financial capital, social capital, strengths, threats, and outcomes.

Figure 2.

Sustainable livelihood framework [21].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Multinomial logistic regression analysis. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and community resilience assessment were conducted using IBM SPSS Version 25 and Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet 2016. The multinomial logistic regression model is commonly applied when dealing with a categorical dependent variable with more than two groups. Within this model, one category is chosen as a reference, and the other categories are compared to this reference by calculating logarithmic odds. In this research, the participants’ socioeconomic status (SES) served as the dependent variable, while the sociodemographic factors were the independent variables. The respondents were categorized into poor, middle, and rich groups to pinpoint the primary factors influencing their livelihood strategies based on factors like income, land ownership, and access to utilities. In terms of empirical application, the MLR within this research can be represented as

j represents the identified clusters, including the poor and middle classes, while j′ refers to the reference cluster, the wealthy class.

3. Results

3.1. Communities’ Socioeconomic Profile

The primary activities of all participants in the chosen community were drying fish and trading fish. They dedicated most of their time, approximately nine months, to the drying process. The survey included participants aged 20 and over, with the majority (39% in Dumuria and 40% in Rampal) falling within the 30 to 40 age range. In terms of religion, Muslims predominantly engaged in the fish-driving trade (77% in Dumuria and 79% in Rampal). At the same time, the Hindu communities, constituting a minority, were observed engaging in fishing and other commercial activities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socioeconomic profile of the fish-drying communities in the study areas.

Survey results revealed that most of Dumuria’s population (37%) lacked formal education, whereas the figure was 25% in Rampal. In Dumuria, 34% of respondents could only sign, while 22% and 7% had received primary and secondary education, respectively. In Rampal, the corresponding percentages were 58%, 14%, and 3%. Housing conditions are indicative of community well-being or economic status. In Dumuria, 30% resided in wood-and-tin structures, while 43% lived in straw-roof houses. Conversely, 6% lived in buildings in Rampal, while 55% resided in tin-and-wood homes (Table 2).

Migration is relocating individuals within a state’s borders for work or settlement purposes. The survey indicated that 71% of Dumuria respondents were migrants, whereas in Rampal, the proportion of migrants (58%) was lower compared to Dumuria (Table 2). In Dumuria, 33% did not require financial assistance or loans, 42% borrowed from cooperatives, 15% from NGOs or banks, and 10% from neighbors. For Rampal, these percentages were 29%, 45%, 12%, and 14%.

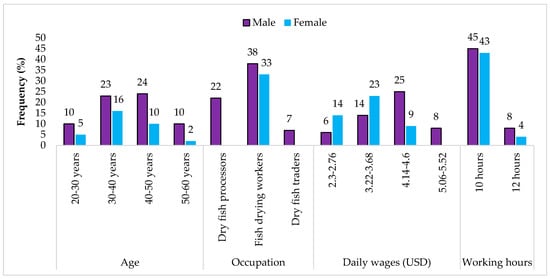

3.2. Gender Perspectives on Livelihoods in Fish-Drying Communities

In Dumuria, the majority of fish-drying employers (67% male, 33% female) were employed by dry-fish producers (22%) and traders (7%). Among these, women, particularly widows and divorcees, constituted the most significant portion of dried-fish workers. For male workers, most (25%) earned between USD 4.14–4.6 a day−1, while a smaller fraction (8%) earned between USD 5.06–5.52 a day−1, typically working 10–12 h. In contrast, women (23%) earned between USD 3.22–3.68 a day−1, with only 9% earning between USD 4.14–4.6 a day−1 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Gender involvement profile of the Dumuria fish_drying community.

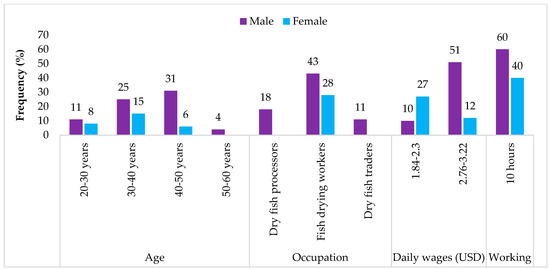

In Rampal, the majority of fish-drying workers (71% male, 29% female) were employed by dry-fish producers (18%) and traders (11%), and among these, women, particularly widows and divorcees, constituted the most significant portion of dried-fish workers. For male workers, most (51%) earned between USD 2.76–3.22 a day−1, while a smaller fraction (10%) earned between USD 1.84–2.3 a day−1, typically working 10 h. In contrast, women (27%) earned between USD 1.84–3.68 a day−1, with only 12% earning between USD 2.76–3.22 a day−1 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Gender involvement profile of the Rampal fish_drying community.

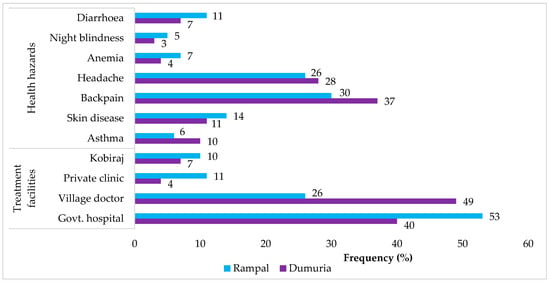

3.3. Health Issues and Treatment Facilities

Around 37% of Dumuria respondents mentioned experiencing back pain, whereas 26% reported headaches in Rampal. Apart from headaches, respondents also reported various health issues such as skin diseases, asthma, diarrhea or fever, anemia, and night blindness (Figure 5). The health services available to the communities were inadequate. Approximately 49% of Dumuria respondents sought treatment from village doctors, while 53% of Rampal respondents received medical care from government hospitals (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The respondents’ occupational hazards and treatment facilities involved in fish-drying practices.

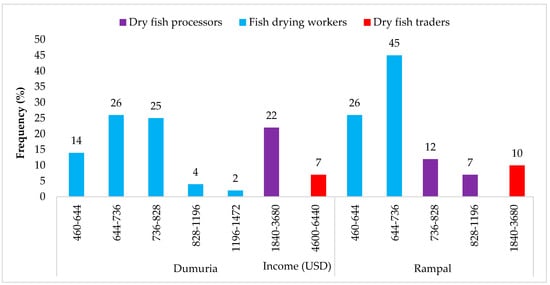

3.4. Income during the Drying Season (Peak Season)

During the fish-drying season in Dumuria, 22% of dried-fish producers earned between USD 1840–3680 a year−1, with dried-fish traders (7%) recording the highest earnings, ranging from USD 4600–6440 a year−1. Among fish-drying workers, 26% earned USD 644–736 a year−1 (Figure 6). In Rampal, due to the small-scale nature of their business, fish-drying communities generated lower incomes than Dumuria’s dry-fish traders and producers.

Figure 6.

The annual income of the dried_fish communities.

3.5. Nutrition and Food Consumption Status

In Dumuria, the consumption of a low-quality diet was notably more frequent (66%) than in Rampal (33%). Around 95% and 93% of respondents from Dumuria and Rampal consumed three daily meals. Still, during the off-season, the impoverished individuals in both villages had to skip one meal daily (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nutrition and food consumption ratio of the respondents of the studied areas.

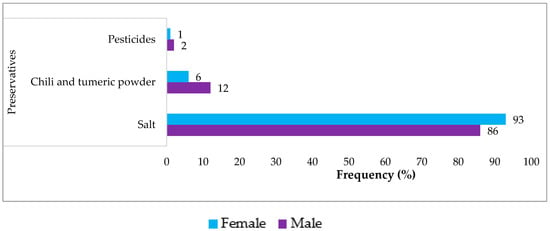

3.6. Public Health Concern

Throughout the study duration, the utilization of pesticides for fish drying was relatively limited (2% in Dumuria and 1% in Rampal), utilization of chili and turmeric powder was 12% in Dumuria and 6% in Rampal, and salt utilization for fish drying was 86% in Dumuria while 93% in Rampal. However, handling raw fish before drying was unhygienic (Figure 7). In drying, less valuable fish are transported from the fish landing center to the drying area (Khola). These fish are rinsed as necessary and placed on bamboo mats. Subsequently, the fish are combined with salt before sorting, a stage leading to a notable decline in fish quality. Following sorting, the fish are cleansed using water in bamboo baskets, plastic buckets, or drums and then laid out on bamboo mats or shelves to undergo the drying process. Regrettably, the bamboo mats and baskets utilized are frequently unclean and remain unwashed between consecutive drying cycles for different batches.

Figure 7.

Percentage of preservative utilization in fish drying and processing.

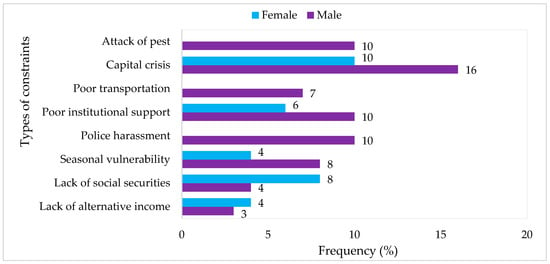

3.7. Livelihood Constraints and Vulnerability Context

Due to their exposure to seasonal variations and harsh weather, the fish-drying communities along the southwestern coast encounter numerous socioeconomic challenges in maintaining their livelihoods. These obstacles encompass capital crises, the absence of social safety nets, and inadequate institutional backing for borrowing funds (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Respondents from the community faced significant constraints.

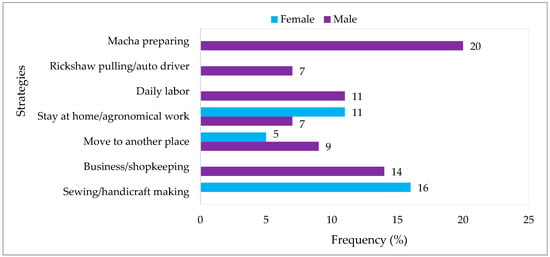

3.8. Coping Strategies during Off-Season

Fish-drying activities were predominantly conducted between August and April, known as the peak season. During these nine months, traders, producers, and employers dried fish. In the rainy season, also referred to as the off-season, processing and drying were halted due to heavy rainfall. During this off-season, individuals adopted various strategies to sustain their livelihoods. Figure 9 illustrates that approximately 7% of men and 11% of women engaged in agricultural work at home. In contrast, around 20% of male respondents were involved in preparing fish-drying facilities (Macha), and 16% of female respondents dedicated their time to activities like poultry raising, sewing, and handicrafts.

Figure 9.

Coping strategies evolved by the respondents during the lean season.

3.9. Resilience Assessment of the Communities to Livelihood Vulnerabilities

This study utilized the ‘Sustainable Livelihood Framework’ to comprehend the communities’ resilience linked to their reliance on current assets. In the case of resilience assessment, the dry-fish producers, traders, and employers who ran the fish-drying communities with their skills and knowledge were named human assets. The physical asset indicators encompass residences, fish drying Macha, fish landing centers, markets, and road infrastructure. The absence of these physical assets results in the complete cessation of fish-drying operations. Communities primarily relied on having diverse dried-fish species and sufficient drying land as their main livelihood choices. Water, forest, and grassland served as crucial natural resources enhancing community resilience, with grassland specifically offering protection against land erosion. Engagement in dried-fish production and trading, daily earnings, and food expenses were recognized as vital financial assets crucial to community resilience. Credit, illegal taxes, and livestock also play essential roles. Cooperatives, dried-fish trader associations, social relationships, and social class are social assets that significantly sustain economic development and human welfare.

3.10. Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis According to Socioeconomic Status

This analysis assessed whether economic factors impact the livelihood strategies of communities classified as poor, middle, and rich. The parameter estimate for the final model is shown in (Table 4). The ‘rich class’ category was used as a reference group in the research. The logistic analysis computed odds ratio coefficients for demographic variables in the model, and these coefficients were compared to the reference category of the wealthy class. The analysis results revealed that among ‘poor class’ respondents, three sociodemographic variables (annual income of respondents, credit access, and social securities) significantly impacted their livelihood strategies. For ‘middle class’ communities, five variables (age of respondents, annual income, credit access, social securities, and treatment facilities) significantly influenced their livelihood strategies at the 1% and 10% significance levels. The analysis was based on 15 hypothesized variables. Compared to other demographic aspects, respondents’ annual income demonstrated an odds ratio (OR) of 0.001 (95% CI 4.48 to 0.218), p = 0.016; credit access had an OR = 9035.053 (95% CI 295 to 276,711,941.327), p = 0.084; social securities exhibited an odds ratio (OR) of 4444.885 (95% CI 4.310 to 4,583,694.631), p = 0.018. Among the ‘middle class’ categories, results indicated that respondents’ age had an odds ratio (OR) of 8.106 (95% CI 3.965 to 0.828), p = 0.085; credit access had an odds ratio (OR) of 1.681 (95% CI 1.168 to 2.419), p = 0.005; annual income of respondents had an odds ratio (OR) of 488 (95% CI 0.213 to 1.123), p = 0.092; treatment facilities of respondents had an odds ratio (OR) of 123 (95% CI 0.043 to 0.349), p = 0.000; social securities of respondents had an odds ratio (OR) of 296 (95% CI 112 to 783), p = 0.014.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis according to the economic status of the studied areas.

4. Discussion

The presence of marine fish and their subsequent drying, production, and trade have improved the financial status of numerous impoverished coastal communities, enhancing their socioeconomic conditions. Yet, this situation has also made them vulnerable to various challenges, highlighting the necessity of strengthening community resilience. Communities involved in fish drying along the southwestern coast face socioeconomic challenges due to the labor-intensive nature of the work, lower literacy rates, unstable earnings, reliance on seasonal drying, limited access to resources, and the need for alternative income sources. Owing to the very low levels of education in the fish-drying community, people have encountered difficulties with improving socioeconomic well-being, contemporary technologies, varied sources of income, and sustainable livelihoods. In Dumuria, the percentage of illiteracy was significantly higher (37%) than in Rampal (25%).

In Rampal, however, over half of the interviewees were able to write their names (Table 2). This finding aligns with a study by [23] which indicated that 25% of dried-fish producers in Barisal and 40% in the Kuakata region lacked formal education. Previously, there was a belief that having more family members could increase earnings, but this notion has become less significant [24]. Due to financial constraints and daily expenses, the study’s individuals prefer smaller nuclear families over joint ones. Analysis of household compositions among fish-drying settlements on the southwestern coast showed that many managed larger families comprising 5–7 members, primarily adults, exceeding the national average (4.5 people per household). This aligns with [25], whose research showed that families with 5–6 individuals make up about half of the fish-drying villages in the Cox’s Bazar area.

Among workers, male participation was higher than female participation (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Numerous widowed and divorced women achieved self-sufficiency through engagement in fish-drying operations. While some fish-drying workers were seasonal employees of producers and traders, others held permanent or casual roles. Men predominantly oversaw dried-fish processing activities, yet a substantial portion of the work, such as pairing, grading, sorting, and turning dried fish, was undertaken by female workers. More or less similar results were highlighted by Almaden [16], indicating women’s focus on fish processing and men’s involvement in fishing and drying. During the study, females were asked whether they encountered more discrimination than men. The responses varied, with some acknowledging discrimination, while others mentioned that men were assigned more labor-intensive tasks and received higher compensation. In the Indian Sundarban region, gender discrimination against women is pervasive, according to a research by Roy et al. [18]. The arrangement of accommodation, possession of land, and houses holds significance in evaluating a community’s socioeconomic welfare. Observations revealed that a majority of Dumuria respondents (61%) lived in rented houses, while in Rampal, 37% of traders and processors owned their homes (Table 2). In Dumuria, casual workers mentioned living in subpar rented dwellings near drying sites during the peak season, often established or leased by owners/traders. They found it challenging to accommodate their families of 5–6 members within a single room, a situation less prevalent in Rampal. Conversely, 78% of fry and fingerling vendors possessed their own residence, with 22% living in rented accommodations [26].

The availability of hygienic and secure drinking water is considered a fundamental necessity. The community’s access to these amenities was below desirable levels, despite efforts by the local government to ensure fundamental services. While most study areas had electricity, the drinking and sanitation facilities in Dumuria were inferior to those in Rampal. As Asif et al. [26] highlighted, traders in the Jessore region had satisfactory sanitation facilities. However, some fisherman on Nijhum Dip Island rely on renewable energy because not all of them have access to electricity [27], contradicting the present findings.

Migration significantly influences livelihood strategies. In the peak season, seasonal fish-drying laborers relocate to Dumuria with their families, residing in accommodations provided by processors and traders near the drying site. This implies that seasonal variations are not the sole motive for community migration. In addition, various migration drivers, such as scarcity of jobs and social instability within the local community, compel them to seek opportunities elsewhere. Similarly, it has been observed that socioeconomic uncertainties, vulnerabilities, and a lack of employment force fishermen and their families along the south central coast to relocate closer [24].

Most communities worked extended hours under the sun’s heat, leading to health problems like headaches, eye swelling, back pain, rheumatism, and skin darkening due to changing seasons and sun exposure (Figure 5). Despite one Upazila Health Complex in the region, the medical services accessible to the community were inadequate, given their limited ability to afford healthcare. The study revealed that over one-third of respondents, comprising dried-fish processors, dealers, and workers, had access to resources like fishery offices, institutional organizations, sea access, markets, and firewood (Table 2). However, most dried-fish workers lacked access to institutional organizations or microcredit, primarily due to their social standing within the communities. Similarly, Singh et al. [28] found that around 82.50% of women in Coastal Odisha had market access, while less than one-third of both genders had access to institutional credit. These findings do not align with the current study.

Within the dried-fish community, dry-fish processors and traders experienced more secure livelihoods than employers, owing to factors like income, occupation, asset ownership, and seasonal investments in drying. In contrast, most employers were impoverished, landless, lacked skills, confined to a limited work environment, and vulnerable to exploitation by producers and dealers. This scenario resulted in livelihood insecurity. Similar findings were noted by [1], indicating the diverse social origins of workers engaged in fish drying under varied production relations. The authors concluded that this situation significantly impacted workers’ lives, often leading to subgroup exploitation and adverse effects on social welfare.

Communities participating in fish-drying activities were observed exerting continuous effort throughout the day to sustain their sustenance and livelihoods. Nonetheless, a majority struggled to fulfill their basic needs [28]. Due to their higher income (Figure 6), dry-fish producers and traders found it comparatively easier to meet their livelihood and essential requirements. Conversely, many poorer fishermen and workers allocated much of their earnings to food, healthcare, and education. This group faced food scarcity, leading them to reduce meals to twice a day and opt for more economical food options (Table 3). This adjustment signifies their low earnings and lack of alternative off-season livelihood opportunities. Similar outcomes were observed by Rana et al. and Mondal et al. [17,29].

Fish-drying operations in the study regions were greatly influenced by seasons, and a large proportion of respondents, mainly fish-drying employers, were engaged in seasonal employment. These employment categories negatively impacted community livelihoods, contributing to capital shortages and workplace vulnerabilities (Figure 9). Marimuthu [30] observed similar issues among inland fishermen, encompassing employment patterns, absence of transportation, safety concerns, and high risks, aligning with the current study’s findings. Moreover, a significant portion of the communities heavily relied on fish-drying endeavors. Nevertheless, the lean season presented such hardships that men and women needed to engage in diverse endeavors to sustain their livelihoods (Figure 9). In response to financial challenges, they borrowed funds from various sources, including institutions and family members, to manage their livelihoods and cover necessities such as weddings, festivals, medical expenses, and other essential requirements [31,32].

Community resilience involves how environmental and socioeconomic systems react to changes, adverse shocks, and seasonal variations [33]. Since solar energy is pivotal to fish drying, adverse weather conditions like windstorms, heavy rainfall, and cloudy days can severely hinder the communities’ resilience. The resilience assessment demonstrated that dried-fish communities were comparatively less equipped to address livelihood vulnerabilities than other communities, mainly due to their dependence on natural resources, solar energy, and migration (Figure 10). Dried-fish producers are vital in upholding resilience, with employers engaged in food-for-work and cash-for-work initiatives. Within community resilience, proficient and knowledgeable dried-fish processors and workers, the processing and trade of dry fish, ample drying land, access to various dried-fish species, traders’ collective efforts, and strong community connections have been identified as pivotal factors in bolstering community resilience. A comparable finding was made by Hossain et al. [34] in their study on resilience evaluation among fishing communities on Nijhum Dwip Island.

Figure 10.

Sustainable livelihood framework of the dried-fish communities on the southwest coast of Bangladesh.

Regarding quality control and public health, it has been noticed that most producers, dealers, and employers utilize salt, chili, and turmeric powder to preserve fish during the study duration instead of resorting to pesticides for fish drying and processing. Although pesticide application has dwindled considerably, a minority within the community reported employing pesticides (such as Sobicron and Nogos) on dry fish to mitigate pest threats during heavy rain and cloudy conditions. The lingering effects of these pesticides could pose significant health risks to humans. Consequently, dried fish might appeal to a narrow range of affluent consumers, particularly those mindful of their health.

During the study, significant limitations arose from language barriers and adverse weather conditions, posing difficulties in effectively communicating with respondents. Consequently, a crucial obstacle confronting the dried-fish sector revolves around fostering sustainable fisheries management. Additional challenges within this sector encompass the uncertain ownership status encountered by numerous drying processors and traders, mainly stemming from their susceptibility to climate change impacts. Conversely, utilizing dried fish for aquaculture feed preparation holds substantial promise for the fish feed industry.

A more immediate strategy should prioritize social protection, livelihood diversification, and access to essential services like healthcare, education, clean water, hygiene enhancement, and nutritional supplements. These measures aim to enhance the communities’ socioeconomic status and sustainable livelihoods. Furthermore, community leaders should arrange alternate job prospects or training avenues for employers, particularly during the lean season, to broaden their livelihood opportunities. Establishing a secure area, such as a designated private zone, would facilitate the expansion of fish-drying endeavors for producers and traders. In collaboration with local authorities, government bodies must take essential measures to enhance domestic and global dried-fish exports. Moreover, traditional fish-drying techniques, including processors and workers, should receive training to improve their skills in efficient sun drying, hygiene maintenance, and public health standards.

5. Conclusions

Fish drying is a national endeavor carried out by economically disadvantaged and marginalized coastal communities who use their expertise and determination to meet the growing demand for dried fish. Nevertheless, their livelihood strategies need to be more diversified and are often overlooked. Widows, divorcees, and unmarried women, in particular, exhibit self-sufficiency on the southwestern coast by participating in fish-drying activities. Additionally, the majority of dried-fish workers meet with financial insecurity in their livelihoods due to their lack of land, low social status, limited work options, and vulnerability to exploitation by producers and traders. To enhance the dried-fish worker community’s resilience, expanding employment opportunities and providing social protection is imperative. Empowering the community to make decisions about resource utilization, and securing institutional, organizational, and governmental support is also pivotal. Therefore, the study’s conclusions provide government and local management organizations with a practical resource for creating realistic and suitable management techniques for these populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R. and M.M.S.; methodology, F.R. and A.T.; software, M.A. (Masud Alam) and M.M.H.M.; formal analysis M.A. (Masud Alam) and A.T.; investigation, A.T., P.S. and M.M.S.; resources, M.M.S.; data curation, A.T. and M.A. (Md. Asadujjaman); writing—review and editing, M.M.S. and P.S.; visualization, A.T. and M.A. (Md. Asadujjaman); supervision, M.M.S.; project administration, M.M.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The first author will disclose the data used for the present study upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belton, B.; Hossain, M.A.; Thilsted, S.H. Labour, identity and wellbeing in Bangladesh’s dried fish value chains. In Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, P.C.; Reza, M.S.; Islam, M.N.; Kamal, M. A review on dried fish processing and marketing in the coastal region of Bangladesh. Res. Agric. Livest. Fish. 2018, 5, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Chandrachud, P.; Muralidharan, M.; Namboothri, N.; Johnson, D. The Dried Fish Industry of Malvan. Dried Fish Rep. Final. 2020, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.; Haque, M.E.; Alam, M.S. Livelihood and food security status of fisher’s community in the northern districts of Bangladesh. Int. J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2015, 2, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- DoF (Department of Fisheries). National Fish Week Compendium (in Bengaliu); Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020; p. 160.

- Haque, M.M.; Rabbani, M.G.; Hasan, M.K. Efficiency of marine dry fish marketing in Bangladesh: A supply chain analysis. Agriculturists 2015, 13, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, Q.S. Small-scale fisheries of Bangladesh. Small-Scale Fish. South Asia 2018, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- FRSS (Fisheries Resources Survey System). Fisheries Statistical Report of Bangladesh; Department of Fisheries: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2022; Volume 39, p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, E.H.; Perry, A.L.; Badjeck, M.C.; Neil Adger, W.; Brown, K.; Conway, D.; Dulvy, N.K. Vulnerability of national economies to the impacts of climate change on fisheries. Fish Fish. 2009, 10, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badjeck, M.C.; Allison, E.H.; Halls, A.S.; Dulvy, N.K. Impacts of climate variability and change on fishery-based livelihoods. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, G.; Barange, M.; Blanchard, J.L.; Harle, J.; Holmes, R.; Allison, E.H.; Mullon, C. Can marine fisheries and aquaculture meet fish demand from a growing human population in a changing climate? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Barman, A.; Kundu, G.K.; Kabir, M.A.; Paul, B. Vulnerability of inland and coastal aquaculture to climate change: Evidence from a developing country. Aquac. Fish. 2019, 4, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Sallu, S.; Hubacek, K.; Paavola, J. Vulnerability of fishery-based livelihoods to the impacts of climate variability and change: Insights from coastal Bangladesh. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2014, 14, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, M.M.H.; Shamsuzzaman, M.; Rashed-Un-Nabi, M.; Harun-Al-Rashid, A. Socio-economic characteristics and fishing operation activities of the artisanal fishers in the Sundarbans Mangrove Forest, Bangladesh. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 18, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.M.; Kader, M.A.; Siddiqui, A.A.M.; Shoeb, S. Studies on fisheries status and socio-economic condition of fishing community in Bhatiary coastal area Chittagong, Bangladesh. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2018, 6, 673–679. [Google Scholar]

- Almaden, C.R.C. A Case Study on the socio-economic conditions of the artisanal fisheries in the Cagayan De Oro River. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. (IJSESD) 2017, 8, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.A.H.; Islam, M.K.; Islam, M.E.; Barua, S.; Hossen, S.; Ali, M.M.; Hossain, M.B. Pearson’s correlation and likert scale based investigation on livelihood status of the fishermen living around the Sundarban estuaries, Bangladesh. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2018, 26, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.; Sharma, A.P.; Bhaumik, U.; Pandit, A.; Singh, S.R.K.; Saha, S.; Mitra, A. Socio-economic features of womenfolk of Indian Sunderbans involved in fish drying. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2017, 53, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, K.D.; Nabadeep, S.; Pulakabha, C. Comparative study on quality of dry Fish (Puntius spp.) produce under Solar Tent Dryer and Open Sun Drying. Agric. Ext. J. 2017, 1, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.; Belton, B.; Thilsted, S.H. Preliminary rapid appraisal of dried fish value chains in Bangladesh. In World Fish Bangladesh; World Fish: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C.; Carney, D. Sustainable Livelihoods: Lessons from Early Experience; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Aktar, R.; Nahiduzzaman, M.; Barman, B.K.; Wahab, M.A. Social considerations of large river sanctuaries: A case study from the Hilsa shad fishery in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubra, K.; Hoque, M.S.; Hossen, S.; Husna, A.U.; Azam, M.; Sharker, M.R.; Ali, M.M. Fish drying and socio-economic condition of dried fish producers in the coastal region of Bangladesh. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2020, 28, 182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Touhiduzzaman, M.; Shamsunnahar, S.I.K.; Khan, A. Livelihood pattern of fishing communities in south-central coastal regions of Bangladesh. Sch. J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mitu, S.J.; Schneider, P.; Islam, M.S.; Alam, M.; Mozumder, M.M.H.; Hossain, M.M.; Shamsuzzaman, M.M. Socio-Economic Context and Community Resilience among the People Involved in Fish Drying Practices in the South-East Coast of Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla-Al-Asif, M.; Samad, A.; Rahman, M.H.; Almamun, M.; Farid, S.M.Y.; Rahman, B.S. Socioeconomic condition of fish fry and fingerling traders in greater Jessore region, Bangladesh. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2015, 2, 290–293. [Google Scholar]

- Siam, H.S.; Hasan, M.R.; Sultana, T. Socio-economic status of fisher community at Nijhum Dwip. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res. 2020, 6, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sahoo, P.K.; Srinath, K.; Kumar, A.; Tanuja, S.; Jeeva, J.C.; Nanda, R. Gender roles and livelihood analysis of women in dry fish processing: A study in coastal Odisha. Fish. Technol. 2014, 51, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M.E.U.; Salam, A.; Shahriar Nazrul, K.M.; Hasan, M. Hilsa fishers of Ramgati, Lakshmipur, Bangladesh: An overview of socio-economic and livelihood context. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Marimuthu, R. Socio-Economic and Livelihood Profile of Inland Fishermen Households in Theni District, Tamil Nadu. Doctoral Dissertation, Fisheries College and Research Institute, Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu Fisheries University, Tamil Nadu, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.A.; Hossain, M.D.; Jewel, M.A.S. Assessment of fishing gears crafts and socio-economic condition of Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) fisherman of Padma River, Bangladesh. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2017, 5, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Saberin, I.S.; Reza, M.S.; Mansur, M.A.; Kamal, M. Socio-economic status of fishers of the old Brahmaputra River in Mymensingh Sadar upazila, Bangladesh. Res. Agric. Livest. Fish. 2017, 4, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharifuzzaman, S.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Sarker, S.; Chowdhury, M.S.N.; Chowdhury, M.Z.R. Elements of fishing community resilience to climate change in the coastal zone of Bangladesh. J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Rahman, M.F.; Thompson, S.; Nabi, M.R.; Kibria, M.M. Climate change resilience assessment using livelihood assets of coastal fishing community in Nijhum Dwip, Bangladesh. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 21, 397–422. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).