Abstract

Lidar measurements of green laser light traveling inside snow can be modeled using Monte Carlo simulations. These simulations generate databases that link snow properties (such as snow depth and scattering mean free path) with lidar backscatter vertical profile measurements. In this study, these simulated datasets are used to train neural networks to explore the potential for estimating snow properties from ICESat-2 lidar measurements. The networks use simulated snow backscatter profiles as inputs and corresponding snow properties as outputs. Our results indicate that the near-surface portion of the snow backscatter signal contains information relevant to snow depth and scattering mean free path, demonstrating the feasibility of using machine learning frameworks for efficient analysis of spaceborne lidar observations. These findings are presented as a proof-of-concept, with comprehensive external validation and uncertainty quantification identified as future work.

1. Introduction

Snowpack, the accumulation of snow on the ground, is crucial for water resources, ecosystem health, and recreational activities [1,2,3,4,5,6]. It acts as a natural reservoir, gradually releasing meltwater, which is vital for human consumption, agriculture, and hydropower generation [7,8,9]. In addition, snowpack plays a critical role in regulating climate, moderating soil temperature, and influencing wildfire risk [10,11,12]. Accurate monitoring of snowpack conditions is therefore essential for hydrologic forecasting, climate modeling, and natural hazard assessment.

Traditional ground-based measurements, such as snow stakes and rulers [13], ultrasonic sensors [14], and manual snow courses [15], provide high accuracy measurements but are limited in spatial and temporal coverage, particularly in mountainous, forested, and polar regions where access is challenging and conditions vary rapidly [16,17]. To address these limitations, remote sensing techniques have become indispensable for large-scale monitoring of snowpack dynamics [18,19,20], which offer a unique capability to monitor snow extent, depth, and physical properties across broad spatial and temporal scales [21,22].

A range of remote sensing techniques have been applied to monitor snow, including passive microwave radiometers such as the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer (AMSR-E/AMSR2) [19], optical sensors such as the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), and the Landsat series from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) [23,24], as well as active sensors including radar and lidar [25,26,27].

Passive microwave observations are particularly effective at estimating snow water equivalent (SWE) in dry-snow conditions, but their coarse spatial resolution (e.g., ~25 km) and reduced sensitivity in complex terrain or wet snow limit their utility [28]. Optical and infrared sensors provide moderate spatial resolution (e.g., 500 m) of snow-covered area and albedo, but they cannot directly measure snow depth [29,30]. Measurements of snow depth and snow density are essential for accurately estimating the amount of snowpack [31]. Active microwave systems, including synthetic aperture radar (SAR), can provide information on snow depth under certain conditions, although retrieval performance is strongly affected by snow wetness, the presence of complex layering, and surface roughness [27]. Airborne lidar has demonstrated exceptional capability for high-resolution (e.g., ≤1 m) mapping of snow depth by differencing snow-on and snow-off elevation surfaces, but airborne campaigns remain costly, infrequent, and geographically constrained [32]. Recent advances in spaceborne lidar now provide, for the first time, the potential to measure snow depth from orbit, offering a transformative new capability for global snowpack monitoring [30].

NASA’s Ice, Clouds, and Land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2) mission provides global photon-counting lidar measurements through the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System (ATLAS), which emits green (532 nm) laser pulses and records the time-of-flight of individual backscattered photons [33]. Although ICESat-2 was originally designed to measure ice-sheet elevations and land topography, recent studies have demonstrated its potential for snow-depth retrieval across diverse landscapes, including mountains [34,35], tundra [36], and ice sheets [37].

A common approach, the snow on–off method, estimates seasonal snow depth by differencing surface elevations acquired during snow-covered (snow-on measurements) and snow-free periods (snow-off measurements) [38,39,40]. While the snow on–off approach provides a conceptually straightforward method for estimating snow depth, this method is limited by temporal and spatial mismatches, as the time gap between snow-on and -off measurements, along with differences in ground tracks, can reduce snow depth accuracy, particularly in complex terrain.

NASA Langley team has recently developed an innovative snow pathlength method to estimate snow depth using only ICESat-2 snow-on measurements [41,42,43]. This method is based on analyzing the photon multiple-scattering pathlength distribution within the snowpack, which is related to how far photons travel within the snow before being scattered back to the lidar. A key finding from radiative transfer and Monte Carlo simulations is that, at a conservative scattering wavelength (e.g., 532 nm), the average photon pathlength inside the snow is approximately twice the physical snow depth [42]. This relationship provides a theoretical basis for inferring snow depth from ICESat-2 observed photon time delays. Monte Carlo simulations of light scattering by snow particles under a wide range of physical and optical conditions, including snow depth, snow density, effective grain size (volume-to-surface ratio), and single scattering asymmetry factor, confirm the robustness of this relationship [41,42].

For space-based lidar (e.g., ICESat-2) measurements where the receiver footprint is at least a few meters larger than the laser spot, the Monte Carlo simulation larger than the laser spot, the Monte Carlo simulation results suggest that:

- The photon multiple-scattering pathlength distribution is primarily determined by snow depth and the effective scattering mean free path, <p>, which is a function of snow density, effective single scattering asymmetry factor, and snow particle volume-to-surface-area ratio (commonly referred to as “grain size”).

- The averaged pathlength of the photon multiple-scattering pathlength distribution, <L>, equals twice the physical snow depth, i.e., <L> = 2× (snow depth).

Using the theory, snow depths can be derived from the satellite lidar measurements of the pathlength distributions of green laser photons scattering inside the snow (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [41,42,43].

Figure 1.

Blue-green sunlight penetrates snow and undergoes multiple scattering, while light at other wavelengths is more strongly absorbed or reflected.

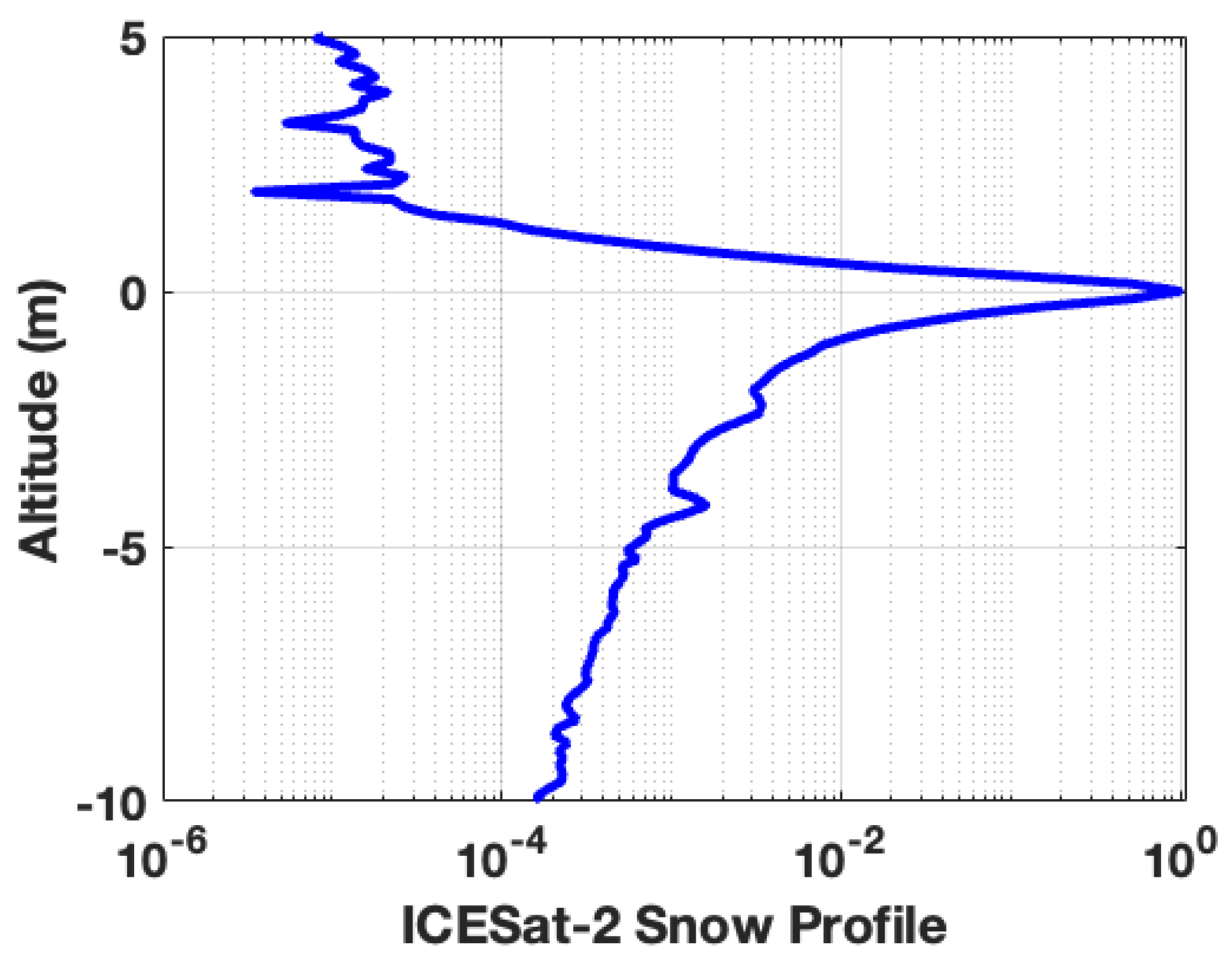

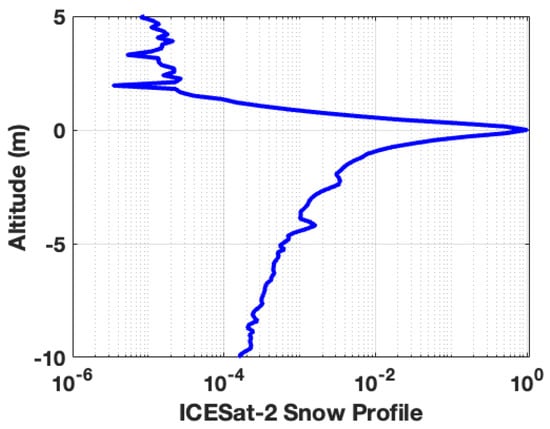

Figure 2.

An example of the lidar signals from ICESat-2 measurements. The snow profile is normalized by the surface peak and binned at a vertical resolution of 15 cm.

The proposed snow pathlength retrieval method leverages the vertical distribution of multiple-scattered photons measured by ICESat-2 and provides several advantages over traditional elevation-difference-based approaches. Unlike the snow on–off method, it does not require reference Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) or snow-off measurements, thereby avoiding errors associated with temporal gaps, ground-track mismatches, and DEM inaccuracies [36]. This snow pathlength approach enables direct, single-pass estimation of snow depth, making it especially valuable in regions with rapidly changing snow conditions. In addition, compared with passive microwave radiometer products such as AMSR2, the pathlength method provides meter-scale spatial resolution and is applicable across a wide range of surfaces, including first-year and multiyear sea ice as well as terrestrial snowpacks [43]. ICESat-2 delivers global photon-counting lidar measurements with ~11 m laser spots, a receiver footprint of approximately 42.5 m, and ~0.7 m along-track resolution [44,45]. Combined with the pathlength method, these capabilities support high-precision, fine-scale mapping of snow depth in environments where conventional remote sensing techniques are limited. Spaceborne lidar thus complements traditional field observations and other satellite sensors by providing high-resolution vertical information on snow properties.

Although the ICESat-2 snow depths derived using the pathlength method generally compare well against other independent measurements [43], there remains room for improvement because ICESat-2 was not specifically designed for optimized scattering pathlength measurements. Therefore, improvements are needed in both retrieval algorithms and measurement approaches.

The objectives of this study are therefore twofold:

- (1)

- to develop a machine learning-based data analysis framework that can efficiently explore the potential for estimating snow depths from imperfect spaceborne lidar measurements, and

- (2)

- to investigate new strategies for obtaining feasible and informative snow-depth measurements using current spaceborne and potentially future optimized lidar systems.

By providing reliable, high-resolution estimates of snow depth from single-pass spaceborne lidar observations, the proposed machine learning-based pathlength method enables detailed investigations of snow accumulation and ablation processes, enhances characterization of spatial heterogeneity in mountain snowpacks, and improves assessments of snow distribution in forested and polar regions where traditional techniques face significant limitations. The ability to retrieve snow depth at fine spatial scales also supports more accurate modeling of snow hydrology, surface energy balance, and avalanche hazards, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of seasonal snow dynamics under a changing climate. In addition, the use of machine learning strengthens the retrieval by efficiently handling noisy photon data, capturing complex nonlinear relationships in the scattering signatures, and providing fast, scalable predictions suitable for large-volume satellite datasets.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the neural network-based snow-depth retrieval algorithm designed for application to ICESat-2 snow-on measurements. Section 3 presents the evaluation of the network models using both Monte Carlo simulations and ICESat-2 lidar observations. Section 4 summarizes the key findings and conclusions.

2. Methodology

2.1. ICESat-2 Measurement Limitations and Data Challenges

First, this study introduces a machine learning algorithm developed to effectively manage noisy photon measurements and overcome two major measurement limitations of ICESat-2 data.

- Transient response of ATLAS: ICESat-2’s ATLAS exhibits a transient response that affects its recorded signals [46]. After receiving the primary signal (e.g., snow surface signal), the lidar system can produce secondary signals (so-called “after-pulses”) that appear as additional photons, potentially misrepresenting and distorting the true surface return. Traditionally, a deconvolution procedure [47,48,49] is required to remove this effect and recover the true scattering pathlength distribution. However, this deconvolution process can introduce errors, especially when applied to noisy lidar profiles.

- Limited photon return data: ICESat-2 was primarily designed to measure the elevation of Earth’s surface [33]. Due to limited downlink bandwidth, the satellite only sends back the time-tags of photons that are close to the surface and ignores the long tails of the multiple-scattering pathlength distribution. Although those ignored tails can be approximated from the near-surface portion of the signals, such extrapolation may introduce errors into the estimated averaged photon pathlength.

Addressing these challenges is critical for accurately retrieving snow depth from spaceborne lidar measurements. This study addresses both issues using neural networks trained on a dataset generated by Monte Carlo simulations of laser light propagation inside snow with varying snow properties (e.g., snow depth, snow grain size, snow density, scattering phase functions, etc.). To replicate ICESat-2 observations, the ATLAS detector’s transient response, characterized using ICESat-2 on-orbit hard surface measurements and pre-launch Integration and Test (I&T) time-of-flight data [46,47], is applied to the simulated backscatter profiles. The algorithm retrieves snow depth and the effective scattering mean free path, p, directly from the near-surface lidar measurements. Here, the effective scattering mean free path p is defined as [50,51]:

where D is the snow grain size (effective diameter, which is proportional to the ratio of the total volume and the total surface area of all snow particles). is the normalized snow density, which is the snow density divided by the density of ice, with a value of 0.917 g/cm3. g is the effective asymmetry factor of snow particle single-scattering phase function (typically 0.75–0.9). In the microwave snow-measurement community, the effective scattering mean free path is also referred to as the “correlation length”.

2.2. Monte Carlo Simulations

To construct a comprehensive training dataset for the neural network, we have chosen a wide range of snow depths and effective scattering mean free paths for the Monte Carlo simulations. Snow depths range from 5 cm to 3 m with a 1 cm increment. Effective scattering mean free paths range from 30 µm to 3 mm with a 10 µm increment. The free paths are chosen to represent snow optical properties spanning a wide variety of snow grain sizes and densities, as well as assumptions about the forward peaks of the scattering phase functions, consistent with existing snow modeling studies, (e.g., Bohren and Barkstrom, 1974 [52]; Warren, 1982 [53]; Hu et al., 2023 [41]; Henley et al., 2025 [50]).

For each semi-analytical Monte Carlo simulation [42,54], we simulated 100 million laser shots. Receiver noise was randomly generated following nighttime noise statistics modeled using ICESat-2 strong-beam parameters, including laser pulse energy, orbit altitude, telescope aperture, instrument optical transmittance, detector transient response, and detector quantum efficiency. The semi-analytical Monte Carlo approach samples the probability of photons entering the satellite lidar detector at each individual scattering event, enabling rapid convergence. As a result, fewer than 1 million photons are sufficient to produce highly smooth vertical snow backscatter profiles of the first 15 m prior to the addition of receiver noises.

2.3. Neural Network Algorithm Development

The neural network retrieval algorithm was developed through the following steps:

- Monte Carlo simulations: Simulate ICESat-2 laser light propagation inside snow for various snow depths and scattering mean free paths. The Monte Carlo simulation model is based on the fast-converging semi-analytical polarized Monte Carlo algorithms originally developed for another spaceborne lidar [54] and is modified for ICESat-2. Instead of tracing each photon interacting with scattering media until they disappear outside of the field-of-view, the semi-analytical algorithm computes the probability of the photon being detected by the space lidar at each individual scattering event.

- Signal generation: Model ICESat-2 lidar observed snow multiple-scatter profiles by incorporating the lidar system’s aperture size, receiver optical transmittance, detector quantum efficiency, instrument transient response [46,55], and detector thermal and shot noise characteristics.

- Neural network training: Three feedforward neural network models were trained using MATLAB’s (Release 2025b) FITNET deep learning toolbox [56]. The inputs consisted of near-surface photon pathlength distributions corresponding to one-way photon travel distances of 6 m, 10 m, and 15 m, e.g., the snow profiles shown in Figure 2. The outputs were the corresponding snow depths and effective scattering mean free paths. Each network included two hidden layers, with 20 neurons in the first layer and 5 neurons in the second layer. Training was performed using randomly selected subsets of the Monte Carlo simulations, while the remaining data were reserved for validation and cross-validation. This procedure ensured that the networks learned robust mappings from photon pathlength distributions to snow properties and were not dependent on a single photon travel distance or subset of the data.

- Validation: The trained networks were applied to the remaining Monte Carlo-simulated lidar profiles, and the retrieved snow depths and mean free paths are compared with the true values used in the simulations to evaluate the retrieval accuracy of the neural networks. Additionally, forward-modeled snow backscatter profiles, generated using the retrieved snow properties by the neural network, were compared to the original simulated profiles to confirm physical and optical consistency.

2.4. Neural Network Architecture

The retrieval framework employs three independent FITNET feedforward neural networks, each trained to learn the nonlinear relationship between photon pathlength distributions and the corresponding snow depth and effective scattering mean free path. Each network uses a two-hidden-layer architecture consisting of 20 neurons in the first layer and 5 neurons in the second layer, which was found to provide sufficient model capacity while minimizing the risk of overfitting. The hidden layers use sigmoid activation functions to capture the smooth, nonlinear variations in the simulated backscatter profiles, while the output layer uses linear activation to allow unrestricted prediction of continuous snow parameters.

The three networks differ only in their input domain: each is trained using photon one-way travel distances truncated at 6 m, 10 m, and 15 m, respectively. This design allows us to assess how much near-surface information is needed for reliable snow depth retrievals. For each network, input vectors are constructed from the snow photon pathlength distributions within the selected depth range, preserving both the shape and the decay characteristics of the backscatter profile as shown in Figure 2. The outputs are the snow depth and the effective scattering mean free path used in the corresponding Monte Carlo simulations.

Training is performed using the Levenberg–Marquardt optimization algorithm implemented within MATLAB’s FITNET toolbox, with early stopping applied through a validation set to prevent overfitting. Approximately 70% of the Monte Carlo-simulated profiles are used for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. To ensure robustness, the three networks are cross validated against one another: retrievals obtained from the 6 m, 10 m, and 15 m networks are compared for consistency when applied to the same test profiles (Figure 3). This architecture is intentionally compact to support efficient inference and potential real-time application to the large volume of spaceborne lidar snow observations.

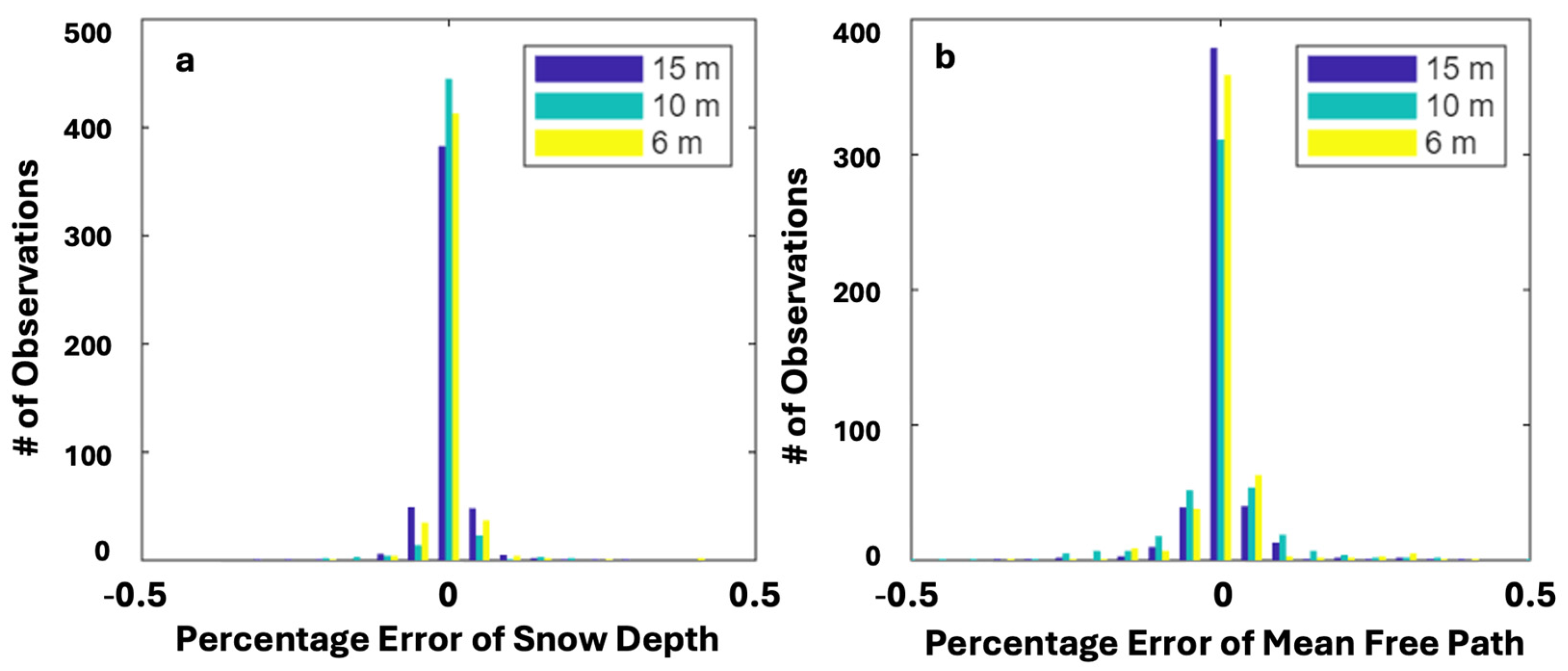

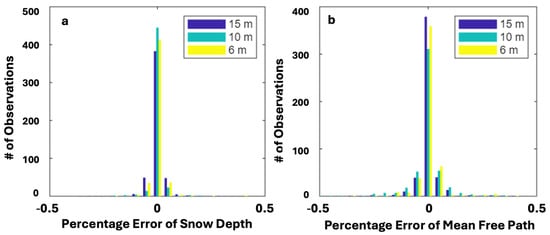

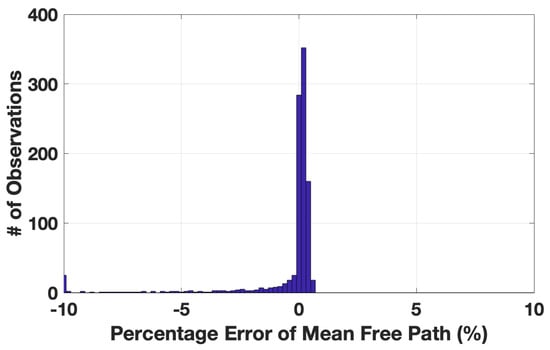

Figure 3.

Histograms of percentage errors in retrieved snow depths (a) and mean free path (b) using neural network algorithms trained with lidar measurements from the first 15 m (blue), 10 m (green) and 6 m (yellow) of one-way photon travel distance below the snow surface.

3. Results

This section evaluates the performance of the neural network-based retrieval algorithm using both Monte Carlo-simulated lidar profiles and ICESat-2 snow observations. We first assess the accuracy and internal consistency of the three networks trained using photon one-way travel distances of 6 m, 10 m, and 15 m (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Then, we apply these networks to ICESat-2 snow-on measurements to assess their capability to retrieve snow depth and scattering mean free path from real spaceborne lidar data. Finally, we examine the physical realism of the retrieved snow properties by comparing forward-modeled snow backscatter profiles with ICESat-2 measured snow profiles (Figure 6).

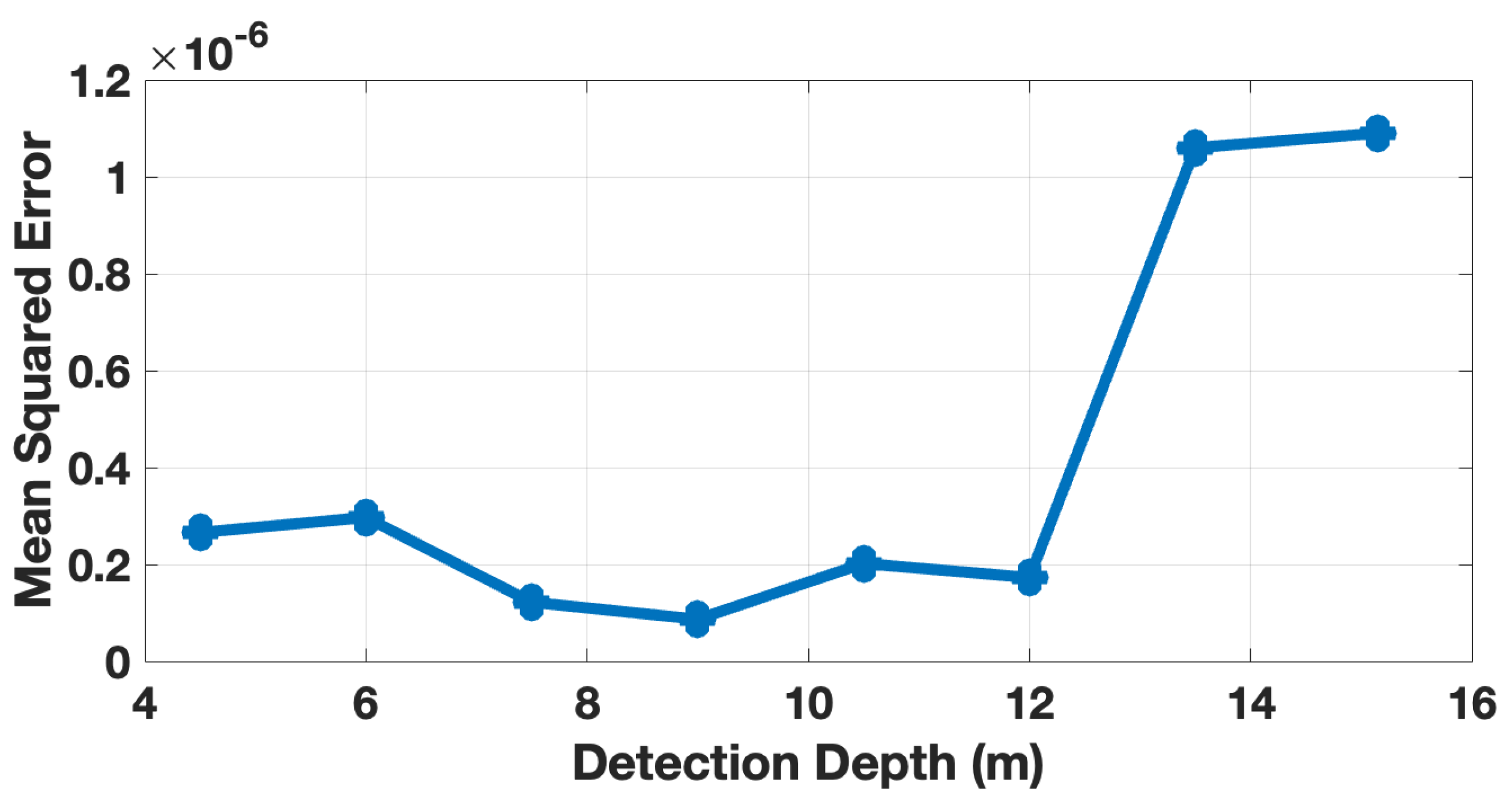

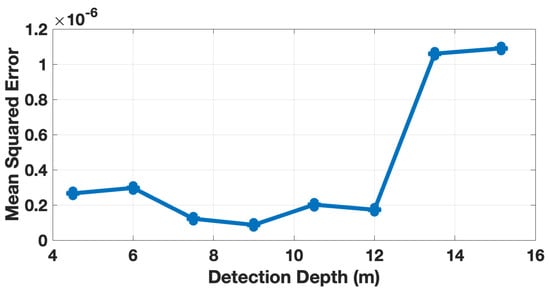

Figure 4.

Snow depth retrieval error as a function of the one-way photon travel distance (detection depth) used in training.

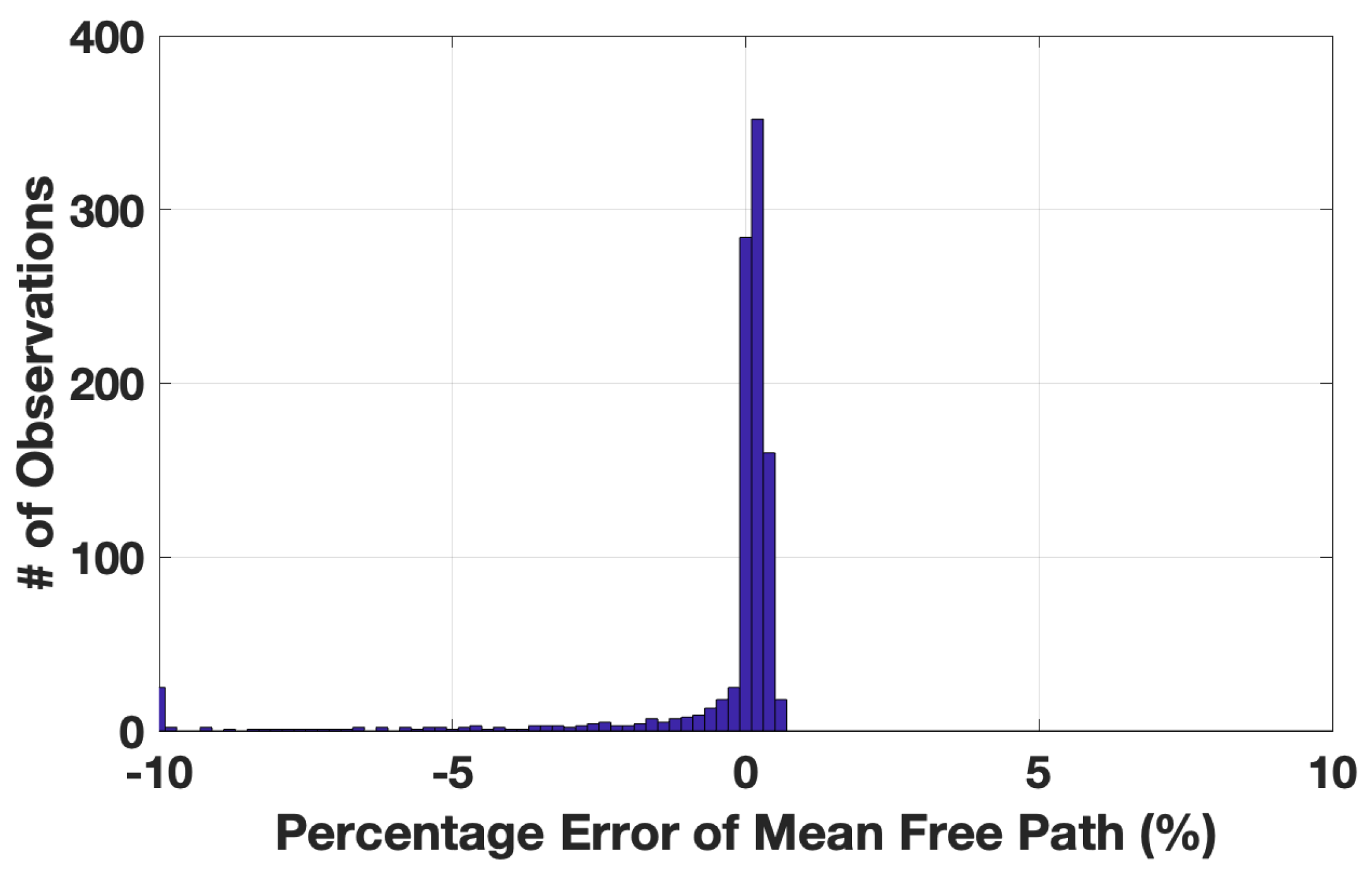

Figure 5.

Histogram of mean free path retrieval accuracy for deeper photon pathlength data using neural networks that were trained on shallower photon pathlength data.

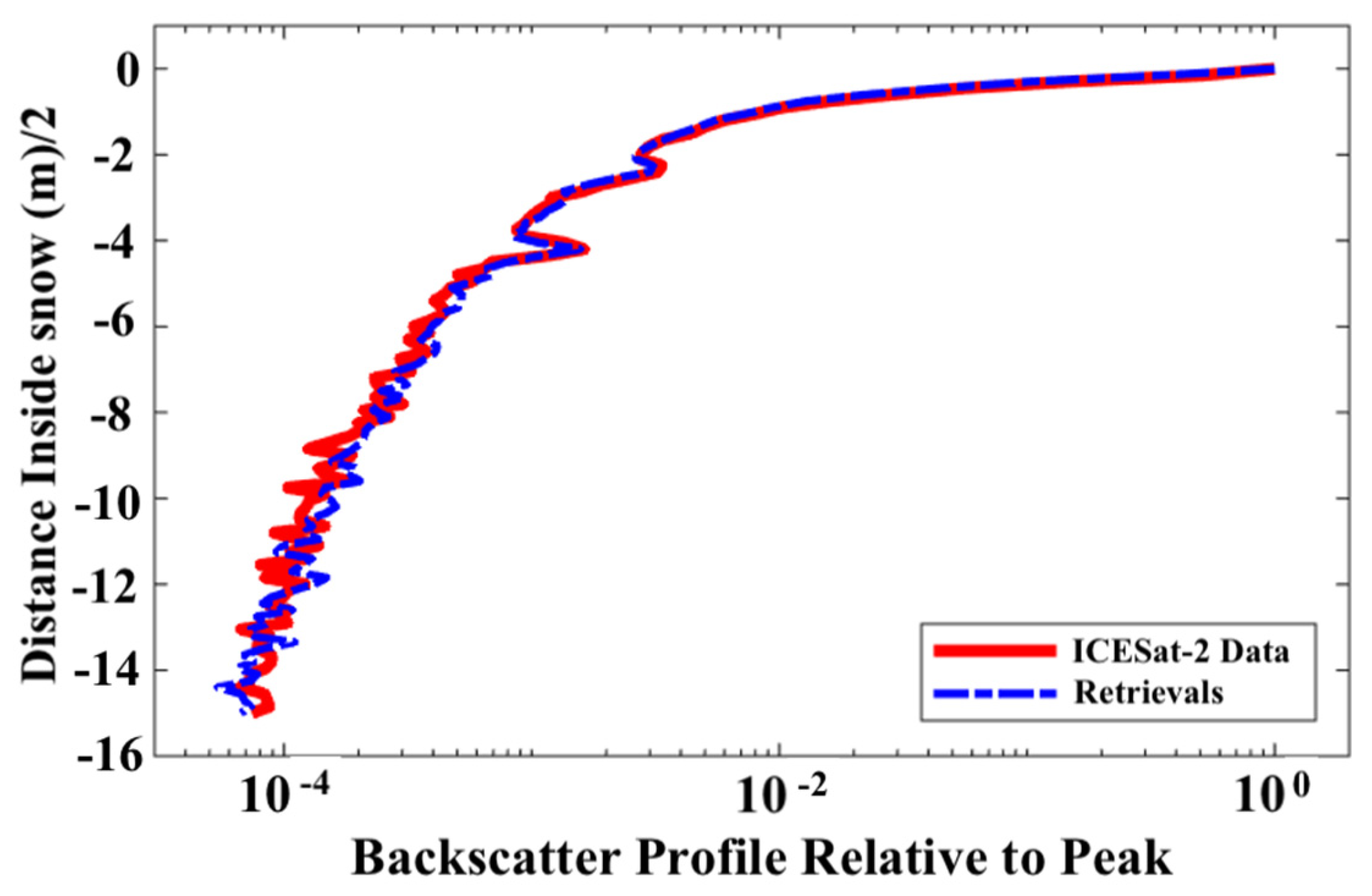

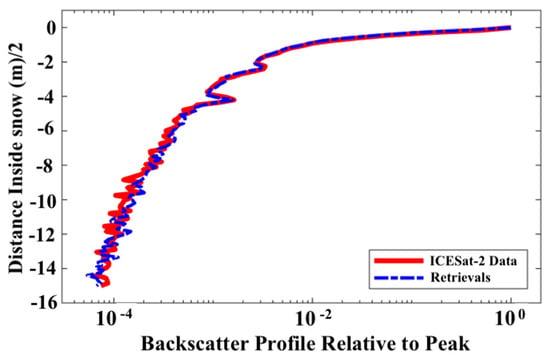

Figure 6.

Snow backscatter profiles from ICESat-2 measurements (red) and Monte Carlo simulations (blue) using the snow depth (33 cm) and mean free path (0.28 cm) derived by the neural network from the ICESat-2 profile (red curve).

Light scattered within snow attenuates exponentially with distance, resulting in higher signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) near the snow surface (Figure 2). If snow properties can be reliably derived primarily from the intensity of the light (or photons) that have traveled only short distances below the surface (shallow photon pathlengths), where SNRs remain high, the required laser power, receiver aperture size, and overall mission cost for a space-based snow lidar can be significantly reduced. Figure 3 and Figure 4 demonstrate that snow depth and mean free path can be accurately estimated from lidar pathlength distributions even when only shallow photon pathlengths are used.

In Figure 3, the percentage errors for retrieved snow depth (panel a) and mean free path (panel b) remain tightly clustered around zero for detection depths corresponding to one-way photon travel distances of 6 m, 10 m, and 15 m (i.e., round-trip distances of 12 m, 20 m, and 30 m). All three depth thresholds exhibit similarly narrow error distributions with no noticeable bias, indicating that the neural networks maintain robust performance even when deeper-scattered photons (e.g., round-trip distances > 30 m) are excluded.

Figure 4 further confirms this finding by illustrating how the mean squared error (MSE) of the retrievals varies with the one-way distance used for the training. Retrieval performance is stable and consistently low for one-way distance between 6 m and 12 m, with MSE values on the order of 10−7 to 10−6, corresponding to snow depth root mean squared error (RMSE) values of approximately 0.05–0.1 cm. A noticeable increase in error occurs only when the one-way distance exceeds ~14–15 m, where photon counts become too sparse to provide sufficient information for reliable network training.

Together, Figure 3 and Figure 4 indicate that accurate estimation of snow depth and mean free path does not require deep photon penetration. Reliable snow depth retrievals can be achieved using pathlength distributions corresponding to photon round-trip distances of ~12–30 m, which supports the feasibility of designing lower-power, lower-cost snow lidar systems optimized for shallow photon scattering.

Additional experiments further show that networks trained on shallow photon pathlengths generalize effectively to deeper pathlength data, demonstrating that information contained in the shallower photon pathlengths can be reliably extrapolated to deeper pathlengths with consistently high accuracy. As shown in Figure 5, networks trained on shallow photon pathlength data achieve high accuracy, with more than 90% of the mean free path retrieval errors below 2% when applied to deeper photon pathlength data. This finding is valuable because it indicates that a lidar system does not need to capture all the photons traveling deep into the snowpack, as the upper portion of the scattered photons already contains the critical information for accurate snow depth retrievals. However, the reverse is not true: networks trained solely on deeper pathlength data fail to reliably retrieve snow properties from shallower pathlength data, because the short-path scattering information is not adequately represented in the deep-path training set.

We trained three neural network models using one-way photon travel distances of 6 m, 10 m, and 15 m from Monte Carlo-simulated lidar backscatter profiles as inputs, with corresponding snow depths and mean free paths as outputs. The trained models were then applied to ICESat-2 snow-on measurements. In most cases, the retrieved snow depths and mean free paths from the three networks were nearly identical (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), demonstrating that shallow photon pathlength data are sufficient for snow depth retrievals from spaceborne photon-counting lidar. This consistency indicates that the critical information governing the retrieval is concentrated in the early portion of the backscatter profile, allowing for reduced hardware requirements and potentially lower lidar power budgets for future spaceborne snow lidar missions.

Figure 6 shows a representative example. The ICESat-2 snow backscatter profile (red line) yielded a retrieved snow depth of 0.33 m and a mean free path of 0.28 cm using the trained neural network. These retrieved values were then used as input for Monte Carlo simulations, which generated a corresponding snow backscatter profile (blue line) that closely matches the ICESat-2 measurement, including the exponential decay of the multiple-scattering tail. This close agreement indicates that the retrieved snow parameters produce forward-modeled photon pathlength distributions broadly consistent with ICESat-2 observations, supporting the validity of the neural network retrieval framework and suggesting that the derived snow properties are physically and optically consistent with the underlying photon transport physics.

Please note that the Monte Carlo simulations in this study assume laterally homogeneous and vertically uniform snowpacks, without explicit representation of layering, liquid water, black carbon impurities, surface roughness, or topographic variability. Consequently, the results presented here reflect idealized conditions, and the information content of near-surface photon pathlengths may differ in more complex real-world snowpacks or under varying atmospheric conditions and forest canopy cover.

In our previous study [43], we showed that forward scattering by near-surface clouds and aerosols increases the effective photon pathlength, stretching the measured backscatter profiles [57]. Snow profiles under non-clear-sky conditions exhibit extended pathlength distributions compared to clear-sky observations, potentially resulting in overestimated snow depths. The magnitude of this effect depends on cloud or aerosol optical thickness and varies spatially and temporally. Similarly, surface roughness and slope within the ICESat-2 footprint (~11 m) influence the reflected pulse shape and thus the inferred snow depth. Model simulations indicate that snow depth errors remain below 5 cm when pulse stretching is less than 50 cm, but can exceed 10 cm when the pulse spreading width (σ) exceeds 62 cm [43]. Future work will extend the framework to incorporate realistic snowpack heterogeneity and environmental factors to more rigorously assess retrieval performance under operational conditions.

The neural network-based method offers several advantages over traditional pathlength-based snow retrieval techniques. First, it effectively handles noisy photon measurements and mitigates the effects of ICESat-2’s ATLAS transient response, which can produce after-pulses that distort the true backscatter signal. The conventional deconvolution process can introduce additional errors, particularly for noisy lidar profiles. Second, it overcomes limitations associated with the satellite’s partial photon return data, where long multiple-scattering tails are not downlinked. The neural network learns the underlying relationship between near-surface photons and snow properties directly from the data, reducing potential errors from explicit extrapolation. A systematic comparison between snow depths retrieved using the traditional pathlength method and the neural network approach, as well as a quantitative validation of the neural network retrievals using larger ICESat-2 snow-on datasets and independent snow depth references, including comparisons with existing pathlength-based and snow on–off methods, will be the focus of our next study.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we developed a neural network-based framework to explore the potential for retrieving snow properties from ICESat-2 lidar measurements. The neural networks were trained on Monte Carlo-simulated snow backscatter profiles for a range of snow depths and effective scattering mean free paths, using snow vertical profiles with photon one-way travel distances of 6 m, 10 m, and 15 m as model inputs and the corresponding snow depths and mean free paths as model outputs. When applied to both ICESat-2 and Monte Carlo-simulated snow-on measurements, the retrieved snow depths and mean free paths derived from all three neural networks were internally consistent, suggesting that near-surface photon pathlength data (e.g., with photon one-way travel distances of 6 m, 10 m, or 15 m) contains sufficient information relevant to snow property retrievals.

Our results indicate that the most critical information for snow depth retrieval is concentrated in the upper portion of the lidar backscatter profiles. Forward-modeled Monte Carlo profiles generated from the neural network-retrieved snow depths and mean free paths were generally consistent with the ICESat-2 observed snow vertical profiles, including the multiple-scattering tail, demonstrating internal consistency of the retrieval framework. We emphasize that this forward-model agreement serves as a proof-of-concept consistency check rather than comprehensive validation. Full uncertainty quantification and independent external validation remain the focus of future work.

Overall, this work demonstrates the feasibility of applying machine learning to spaceborne photon-counting lidar for estimating snow depth and scattering mean free path in a physically consistent manner. The findings suggest that near-surface photon returns contain informative signals that could support efficient analysis of spaceborne lidar observations and point toward the potential for future lidar missions to operate with reduced hardware complexity and lower power requirements.

Future work will focus on conducting systematic, quantitative validation of the neural network retrievals using larger sets of ICESat-2 snow-on observations and independent snow depth references, including comparisons with existing pathlength-based and snow on–off retrieval methods. Additional efforts will explore the integration of machine learning with ICESat-2 ATL03 products and extend the framework to account for complex terrain, vegetation effects, and variability in snow microphysical properties. These developments will enable more rigorous assessment of the uncertainty, generalizability, and operational potential of the proposed approach for current and future spaceborne snow lidar missions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; methodology, Y.Z. and K.H.; software, Y.Z. and K.H.; validation, Y.Z. and K.H.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and K.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and K.H.; writing—review and editing, X.L.; supervision, X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the NASA ICESat-2 Award and the NASA Terrestrial Hydrology Program, grant number 80NSSC21K0910.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at https://nsidc.org/data/atl03/versions/7 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NASA ICESat-2 team and the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) for providing the lidar data used in this study. Special thanks are extended to Craig Ferguson from NASA Headquarters for his support of the snow research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ford, C.M.; Kendall, A.D.; Hyndman, D.W. Snowpacks Decrease and Streamflows Shift across the Eastern US as Winters Warm. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpkins, G. Snow-Related Water Woes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, K.J.; Brown, R.D.; Derksen, C.; Painter, T.H. Estimating Snow-Cover Trends from Space. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, G.; Haghighi, A.T.; Klöve, B.; Oussalah, M. Advances in Image-Based Estimation of Snow Variable: A Systematic Literature Review on Recent Studies. J. Hydrol. 2025, 654, 132855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascoin, S.; Luojus, K.; Nagler, T.; Lievens, H.; Masiokas, M.; Jonas, T.; Zheng, Z.; Rosnay, P.D. Remote Sensing of Mountain Snow from Space: Status and Recommendations. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1381323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Cohen, J.; Chen, H.W.; Zhang, S.; Luo, D.; Hamouda, M.E. Attributing Climate and Weather Extremes to Northern Hemisphere Sea Ice and Terrestrial Snow: Progress, Challenges and Ways Forward. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Siebert, S.; Huning, L.S.; AghaKouchak, A.; Mankin, J.S.; Hong, C.; Tong, D.; Davis, S.J.; Mueller, N.D. Agricultural Risks from Changing Snowmelt. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vano, J.A. Implications of Losing Snowpack. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groisman, P.Y.; Karl, T.R.; Knight, R.W. Observed Impact of Snow Cover on the Heat Balance and the Rise of Continental Spring Temperatures. Science 1994, 263, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clow, D.W. Changes in the Timing of Snowmelt and Streamflow in Colorado: A Response to Recent Warming. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 2293–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders-DeMott, R.; Campbell, J.L.; Groffman, P.M.; Rustad, L.E.; Templer, P.H. Chapter 10—Soil Warming and Winter Snowpacks: Implications for Northern Forest Ecosystem Functioning. In Ecosystem Consequences of Soil Warming; Mohan, J.E., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 245–278. ISBN 978-0-12-813493-1. [Google Scholar]

- Westerling, A.L.; Hidalgo, H.G.; Cayan, D.R.; Swetnam, T.W. Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity. Science 2006, 313, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, J.L.; Mote, T.L. Spatial Variability and Trends in Observed Snow Depth over North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L16503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, W.A.; Doesken, N.J.; Fassnacht, S.R. Evaluation of Ultrasonic Snow Depth Sensors for U.S. Snow Measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2008, 25, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, A.R.; Schneebeli, M.; Dadic, R.; Wagner, D.N.; Arndt, S.; Clemens-Sewall, D.; Hämmerle, S.; Hannula, H.-R.; Jaggi, M.; Kolabutin, N.; et al. Snowpit Raw Data Collected During the MOSAiC Expedition; PANGAEA, 2021; Available online: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.935934 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Deems, J.S.; Painter, T.H.; Finnegan, D.C. Lidar Measurement of Snow Depth: A Review. J. Glaciol. 2013, 59, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazzini, R.; Leppänen, L.; Picard, G.; Lopez-Moreno, J.I.; Marty, C.; Macelloni, G.; Kontu, A.; von Lerber, A.; Tanis, C.M.; Schneebeli, M.; et al. European In-Situ Snow Measurements: Practices and Purposes. Sensors 2018, 18, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun-Mack, S.; Hu, Y.; Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Omar, A. Neural Network-Based Snow Depth Retrieval from AMSR-2 Brightness Temperatures Using ICESat-2 Measurement as Ground Truth. Front. Remote Sens. 2025, 6, 1591276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, D.J.; Markus, T.; Comiso, J.C. AMSR-E/Aqua Daily L3 12.5 km Brightness Temperature, Sea Ice Concentration, & Snow Depth Polar Grids, version 3. Archived by National Aeronautics and Space Administration. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC): Boulder, CO, USA, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A. Accuracy Assessment of the MODIS Snow Products. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 1534–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, T.P.; Adam, J.C.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Potential Impacts of a Warming Climate on Water Availability in Snow-Dominated Regions. Nature 2005, 438, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucker, L.; Markus, T. Arctic-Scale Assessment of Satellite Passive Microwave-Derived Snow Depth on Sea Ice Using Operation IceBridge Airborne Data. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2013, 118, 2892–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A.; Salomonson, V.V.; DiGirolamo, N.E.; Bayr, K.J. MODIS Snow-Cover Products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillinger, T.; Rittger, K.; Raleigh, M.S.; Michell, A.; Davis, R.E.; Bair, E.H. Landsat, MODIS, and VIIRS Snow Cover Mapping Algorithm Performance as Validated by Airborne Lidar Datasets. Cryosphere 2023, 17, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Gatebe, C.; Hall, D.; Newlin, J.; Misakonis, A.; Elder, K.; Marshall, H.P.; Hiemstra, C.; Brucker, L.; De Marco, E.; et al. NASA’s Snowex Campaign: Observing Seasonal Snow in a Forested Environment. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 23–28 July 2017; pp. 1388–1390. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, T.; Farrell, S.L.; Richter-Menge, J.; Connor, L.N.; Kurtz, N.T.; Elder, B.C.; McAdoo, D. Assessment of Radar-Derived Snow Depth over Arctic Sea Ice. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2014, 119, 8578–8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.J.; Yang, J.W.; Jiang, L.M.; Pan, J.M.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, C.; Shi, J.C. Evaluation of the Sentinel-1 SAR-Based Snow Depth Product over the Northern Hemisphere. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, M.; Narvekar, P.S. Assessment of the NASA AMSR-E SWE Product. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2010, 3, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, T.; Cavalieri, D.J. Snow Depth Distribution Over Sea Ice in the Southern Ocean from Satellite Passive Microwave Data. In Antarctic Sea Ice: Physical Processes, Interactions and Variability; American Geophysical Union (AGU): Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 19–39. ISBN 978-1-118-66824-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fair, Z.; Vuyovich, C.; Neumann, T.; Pflug, J.; Shean, D.; Enderlin, E.M.; Zikan, K.; Besso, H.; Lundquist, J.; Deschamps-Berger, C.; et al. Review Article: Using Spaceborne Lidar for Snow Depth Retrievals: Recent Findings and Utility for Hydrologic Applications. Cryosphere 2025, 19, 5671–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, M.; Taras, B.; Liston, G.E.; Derksen, C.; Jonas, T.; Lea, J. Estimating Snow Water Equivalent Using Snow Depth Data and Climate Classes. J. Hydrometeorol. 2010, 11, 1380–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuefer, S.L.; Hale, K.; May, L.D.; Mason, M.; Vuyovich, C.; Marshall, H.-P.; Vas, D.; Elder, K. Snow Depth Measurements from Arctic Tundra and Boreal Forest Collected during NASA SnowEx Alaska Campaign. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, T.; Neumann, T.; Martino, A.; Abdalati, W.; Brunt, K.; Csatho, B.; Farrell, S.; Fricker, H.; Gardner, A.; Harding, D.; et al. The Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2): Science Requirements, Concept, and Implementation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 190, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Che, T.; Wang, G.; Dai, L.; Gao, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Shi, Y. Seasonal Snow Depth Dataset over Flat Terrains in the Northern Hemisphere Based on ICESat-2 Data from 2018 to 2020. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2528632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jiang, L.; Yang, J.; Kong, D.; Pang, Y. An Improvement in ICESat-2 ATL03 Snow Depth Estimation: A Case Study in the Tuolumne Basin, USA. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2505628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, Z.; Vuyovich, C.; Neumann, T.A.; Larsen, C.; Stuefer, S.L.; Mason, M.; May, L.D. Characterizing ICESat-2 Snow Depths Over the Boreal Forests and Tundra of Alaska in Support of the SnowEx 2023 Campaign. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR039076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacimi, S.; Kwok, R. The Antarctic Sea Ice Cover from ICESat-2 and CryoSat-2: Freeboard, Snow Depth, and Ice Thickness. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 4453–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hao, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, G.; Li, H.; Yang, Q. Can the Depth of Seasonal Snow Be Estimated from ICESat-2 Products: A Case Investigation in Altay, Northwest China. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 2000405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shean, D.E.; Bhushan, S.; Smith, B.E.; Besso, H.; Sutterley, T.C.; Swinski, J.-P.; Henderson, S.T.; Neumann, T.A.; Williams, J.B. Evaluating and Improving Seasonal Snow Depth Retrievals with Satellite Laser Altimetry. In Proceedings of the AGU Fall Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 13–17 December 2021; p. C33B-04. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps-Berger, C.; Gascoin, S.; Shean, D.; Besso, H.; Guiot, A.; López-Moreno, J.I. Evaluation of Snow Depth Retrievals from ICESat-2 Using Airborne Laser-Scanning Data. Cryosphere 2023, 17, 2779–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lu, X.; Zeng, X.; Gatebe, C.; Fu, Q.; Yang, P.; Weimer, C.; Stamnes, S.; Baize, R.; Omar, A.; et al. Linking Lidar Multiple Scattering Profiles to Snow Depth and Snow Density: An Analytical Radiative Transfer Analysis and the Implications for Remote Sensing of Snow. Front. Remote Sens. 2023, 4, 1202234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lu, X.; Zeng, X.; Stamnes, S.A.; Neuman, T.A.; Kurtz, N.T.; Zhai, P.; Gao, M.; Sun, W.; Xu, K.; et al. Deriving Snow Depth from ICESat-2 Lidar Multiple Scattering Measurements. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 855159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Stamnes, S.A.; Neuman, T.A.; Kurtz, N.T.; Yang, Y.; Zhai, P.-W.; Gao, M.; Sun, W.; et al. Deriving Snow Depth from ICESat-2 Lidar Multiple Scattering Measurements: Uncertainty Analyses. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 891481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magruder, L.; Neumann, T.; Kurtz, N. ICESat-2 Early Mission Synopsis and Observatory Performance. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magruder, L.; Brunt, K.; Alonzo, M. Early ICESat-2 on-Orbit Geolocation Validation Using Ground-Based Corner Cube Retro-Reflectors. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.; Martino, A.; Ramos-Izquierdo, L. ICESat-2/ATLAS Instrument Linear System Impulse Response. ESS Open Arch. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Vaughan, M.; Palm, S.; Trepte, C.; Omar, A.; Lucker, P.; Baize, R. Enabling Value Added Scientific Applications of ICESat-2 Data with Effective Removal of Afterpulses. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2021EA001729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Vaughan, M.; Rodier, S.; Trepte, C.; Lucker, P.; Omar, A. New Attenuated Backscatter Profile by Removing the CALIOP Receiver’s Transient Response. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2020, 255, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Huang, J.; Stamnes, K.; Yi, Y.; Stamnes, S. A New Method for Retrieval of the Extinction Coefficient of Water Clouds by Using the Tail of the CALIOP Signal. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 2903–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, C.A.; Meyer, C.R.; Chalif, J.I.; Hollmann, J.L.; Raskar, R. Measurement of Snowpack Density, Grain Size, and Black Carbon Concentration Using Time-Domain Diffuse Optics. J. Glaciol. 2025, 71, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokhanovsky, A.A.; Zege, E.P. Scattering Optics of Snow. Appl. Opt. 2004, 43, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.F.; Barkstrom, B.R. Theory of the Optical Properties of Snow. J. Geophys. Res. 1974, 79, 4527–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, S.G. Optical Properties of Snow. Rev. Geophys. 1982, 20, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-X.; Winker, D.; Yang, P.; Baum, B.; Poole, L.; Vann, L. Identification of Cloud Phase from PICASSO-CENA Lidar Depolarization: A Multiple Scattering Sensitivity Study. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2001, 70, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y. Ocean Subsurface Study from ICESat-2 Mission. In Proceedings of the 2019 Photonics & Electromagnetics Research Symposium-Fall (PIERS-Fall), Xiamen, China, 17–20 December 2019; pp. 910–918. [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks Fitnet (Deep Learning Toolbox) [Computer Software]. 2025. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/deeplearning/ref/fitnet.html (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Yang, Y.; Marshak, A.; Palm, S.P.; Várnai, T.; Wiscombe, W.J. Wiscombe Cloud Impact on Surface Altimetry from a Spaceborne 532-Nm Micropulse Photon-Counting Lidar: System Modeling for Cloudy and Clear Atmospheres. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 4910–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.