Abstract

As Akasofu noted, no two geomagnetic storms are identical, yet the storm that occurred between 12 and 14 November 2025 stands out as an exceptional phenomenon. Its impact was evident across multiple layers of the ionosphere and numerous parameters, making it essential to conduct a comprehensive multi-parameter analysis of this event. Such an analysis relied upon data from the four LAERT topside sounders mounted aboard the recently launched Ionosfera-M satellites. Global ionospheric dynamics were thoroughlyexamined during the storm period, particularly focusing on the polar and auroral zones, along with the equatorial anomaly region. Notable features included sharp electron density gradients, widespread F-layer disturbances, and the formation of giant plasma bubbles. These elements collectively contributed to the dynamic picture of the ionospheric storm captured through multi-parameter measurements by the LAERT sounders.

1. Introduction

Despite extensive research into the ionospheric effects of geomagnetic storms over many years [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], these phenomena continue to be a focal point in ionospheric studies.

An ionospheric storm encompasses all layers of the ionosphere from the D region to the upper boundaries of the F2 layer. Moreover, the physical causes of changes in the electron concentration (Ne) in the lower and upper regions are different. The main cause of these phenomena in the D and E regions is a change in the ionization rate due to particle precipitation. All disturbances represent an increase in Ne compared to a certain quiet level. The behavior of the upper ionosphere—the F region, both above and below its maximum, is not associated with a noticeable change in ionization sources; therefore, the concentration variations are caused by indirect factors—the neutral composition and dynamic processes. This leads to the fact that during ionospheric storms in the upper ionosphere two phases can be observed: a positive phase and a negative phase. The positive phase is an increase in Ne relative to the background level at the onset of the storm (3–12 h), associated with the strengthening of electric fields and an electron concentration rise in F2 due to the vertical drift of the plasma. The negative phase is a decrease in Ne associated with the heating of the thermosphere and the resulting changes in thermospheric circulation and molecular composition [5].

The negative phase develops from high to mid latitudes, with the effect moving meridianally at a rate of tens to hundreds of meters per second. At equatorial latitudes the entire ionospheric storm period may be positive, or there may even be no noticeable changes observed [4].

A detailed analysis of geomagnetic storms’ influence on the F region is given in [7].

With the first successful launch of the Alouette-1 satellite in 1962, the era of ionospheric topside sounding began [11,12]. The new technology provided a global view on the ionosphere and many important structures were discovered: the system of ionospheric troughs [13], equatorial anomaly [14], and specific features of topside ionograms in thevicinity of the peak height of the ionosphere [15]. The advantage of this global view is in direct measurements of the electron concentration based on the resonance interaction of the sounding wave with the space plasma contrary to the GIM maps of the ionosphere or the occultation profiles based in great extent on the model approximations.

Following the super geomagnetic storm of 10–11 May 2024 [16], the strong geomagnetic storm of 11–14 November 2025 is likely to become one of the most intensively studied events in the coming months. Unlike the study in [16], which utilized data from the SWARM satellite constellation, our work employs data from the Ionozond satellite constellation [17], comprising four Ionosfera-M satellites equipped with onboard topside sounders known as LAERT [18]. The capability of the LAERT topside sounder to deliver multi-parameter global monitoring of the ionosphere across four distinct local time sectors, while simultaneously measuring electron concentrations throughout the entire altitude range from 820 km down to the peak altitude of the F2 layer (hmF2), illustrates that the intensity of the so-called “fountain effect” does not necessarily correlate with geomagnetic storms. For example, the similar effect is observed during strong earthquake preparation phase as it was registered before the Nepal M7.8 and M7.3 earthquakes in 2015 (figure 9 in [19]).

The strength of the storm effect follows from observations showing the formation of dual crests not just near hmF2 but also at the satellite’s orbital altitude of 820 km under quiet geomagnetic conditions.

A comprehensive analysis of topside ionograms and dynamic HF spectra revealed detailed insights into the storm-induced dynamics of the high-, mid-, and low-latitude ionosphere, including the development of large-scale spread F regions and unusual plasma bubbles within the equatorial anomaly. The latitudinal migration of these crests has been visualized using vertical cross-section of the ionosphere, effectively illustrating their behavior across the full altitude range of the ionosphere.

An unexpected and impressive result is the registration of series of solar type III radio bursts simultaneously with the X5.1 solar flare at 10:04 UT on 11 November.

Finally, it should be underscored that the main purpose of the paper is to demonstrate the advantage of the topside sounding and HF radiospectrometry technologies. The detailed discussion of physical mechanisms of observed phenomena will be the subject of a separate paper which will probably be more extended. Here we mainly demonstrate the phenomenology which can be used to improve the empirical models such as IRI and NeQuick.

2. Main Characteristics of Geomagnetic Storm 11–14 November 2025

Between 11 and 14 November 2025, an active solar region (NOAA AR 4274) produced four solar flares and released four coronal mass ejections (CMEs), three of which were Earth-directed [20]. Two of the flares were of class X, and one that peaked at 10:04 UTC 11 November was of extreme energy class X5.16. Following this solar flare, a severe radio blackout was recorded across Europe, Africa, and Asia, lasting approximately from 30 min to one hour [21]. The extreme velocity of the last coronal mass plasma flow, reaching 1500 km/s, allowed it to overtake and absorb the plasma of the previous ejections moving at a slower speed. Such storms are classified as cannibal coronal mass ejections.

Half an hour after the X5.1 solar flare, a rare phenomenon in a high-energy proton flux was registered by the ground-based Aragats Solar Neutron Telescope (ASNT), it was a 77th case of Ground Level Enhancement (GLE) for the whole history of observing such events since 1944 [22].

This fascinating storm was chosen to investigate the impact on the ionosphere and to highlight the multi-parameter measurement capabilities of the LAERT topside sounder.

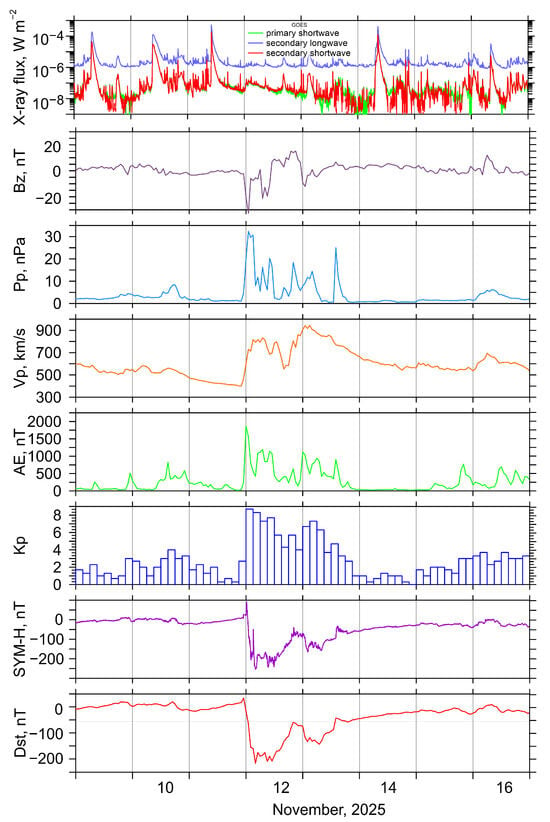

To correlate ionospheric variations with the storm development we will use the set of geophysical parameters presented in Figure 1 [23].

Figure 1.

Geophysical parameters for the period 9–16 November 2025.

3. Experimental Setup and Methods

In this study, our primary data source consists of measurements acquired using the four topside sounders—LAERT instruments aboard the Ionosfera-M satellites. On 25 July 2025, the Ionozond satellite constellation was fully deployed with the successful launches of Ionosfera-M No. 3 and No. 4 spacecraft. These satellites operate in two mutually perpendicular, sun-synchronous, near-circular orbits at an altitude of approximately 820 km. The equatorial crossing times for these orbits are 09:00–21:00 Local Time (LT) for the first pair and 03:00–15:00 LT for the second pair. The satellites of each pair are positioned in the opposite points of the orbit, 180° apart in latitude.

The LAERT topside sounder supports nine distinct operational modes; however, for the purposes of this investigation, only two modes will be utilized: active vertical sounding and active spectrometry in relaxation sounding mode.

During vertical sounding, the sounder sweeps through a frequency range from 0.1 to 20 MHz across the 400 fixed frequencies. It uses step sizes of 25 kHz in the low-frequency band, 50 kHz in the mid-frequency band, and 100 kHz in the high-frequency band. The sounding cycle repeats every 10 s, resulting in 360 ionograms per hour with the spatial resolution of approximately 70 km along the orbit. The vertical resolution is 4.5 km.

To gather additional insights into the electromagnetic environment, the topside sounder records the levels of high-frequency emissions both prior to each sounding pulse and 2.5 ms afterward. This method allows distinguishing between natural emissions such as Auroral Kilometric Radiation (AKR), low-frequency emissions associated with precipitating electrons inside the auroral oval, and solar Type III radio bursts, as well as local plasma resonances induced by the sounding pulses at specific ionospheric plasma frequencies.

Through data processing, we track variations in key parameters including the critical frequency (foF2), local plasma frequency at the satellite altitude (fos) and peak height (hmF2) along the orbital path. These topside ionograms are subsequently converted into vertical profiles of electron density [24], which form the basis for reconstructing the global three-dimensional distributions of electron concentration [25,26].

The satellites in sun-synchronous orbits are unable to monitor the diurnal variations in ionospheric parameters, which is important for studying the dynamics of ionospheric storms at various stages. To address this issue, we utilized data from the Roshydromet’s network of ground-based ionosondes located across the European longitude sector—Rostov-on-Don, Moscow, and Kaliningrad—as well as in the Far Eastern region—Khabarovsk, Magadan, and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.

Combination of these technologies of monitoring the ionospheric parameters helped us to correctly interpret the ionospheric variations registered by satellites in different sectors of local time.

4. Results

Disturbances during geomagnetic storms affect all ionospheric layers from the D region to the upper ionosphere. The most prolonged changes are observed in the F2 layer of the ionosphere. That is why we use for our analysis the variations in critical frequency foF2 at the height of the F-layer maximum hmF2.

4.1. Ground-Based Measurements

To understand the dynamics of the ionosphere at high, middle and low latitudes during a storm, the distributions and variations in the critical frequency of the ionospheric F2 layer were examined in two longitudinal sectors, −20–40° E and 135–160° E, using the data of ground-based vertical sounding ionosondes mentioned above.

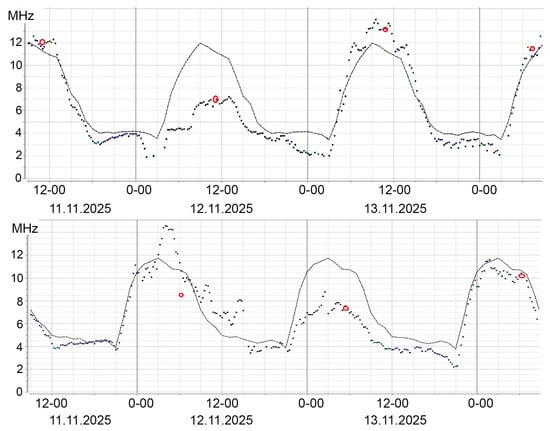

In the upper panel of Figure 2, the solid line represents the 27-day median of the foF2 parameter, while the dots indicate the critical frequency measurements taken at the Rostov-on-Don station. The observed ionospheric activity reveals an extended negative phase of the storm lasting from 03:00 UT on 12 November 2025 until 03:00 UT on 13 November 2025. During this period, the foF2 value dropped by 40% compared to its 27-day median. On 13 November 2025, there was a minor increase in the critical frequency noted later in the day. This pattern of ionospheric behavior was also typical for other stations within the same longitudinal sector, specifically Kaliningrad and Moscow.

Figure 2.

Diurnal variations of foF2 on 12–14 November 2025. Upper panel—Rostov-on-Don station, lower panel—Khabarovsk station. The solid line is the 27-day median, the dots are the observed values. Satellite ionosonde data marked as red circle.

In the bottom panel of Figure 2, analogous findings are presented for the Khabarovsk station. Here, however, the character of ionospheric variations differs significantly. At 05:00 UT on 12 November concurrent with a pronounced decline in Dst index (as shown in Figure 1), a 20% rise in the ionospheric critical frequency was documented, marking the positive phase of the storm. Twenty hours later, the negative phase emerged, characterized by a 30% reduction in the critical frequency, persisting on another nearly full day.

This distinctive ionospheric response mirrored one observed at other locations along the same longitudinal sector, namely Magadan and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. By 14 November, recovery from the geomagnetic perturbation was evident throughout these regions.

These results demonstrate a non-uniform longitudinal response of the ionosphere to the geomagnetic storm. In the longitudinal sector of 20–40° E, where the onset of the geomagnetic storm occurred at the end of the night (03:00 UT corresponds to 06:00 LT), the ionospheric negative disturbance began synchronously with the geomagnetic disturbance. But in the case of the storm onset that occurred during the day (135–160° E), when the D and E layers of the ionosphere were still present, a positive phase with an increase in concentration in the F layer was recorded. Only 20 h later, by the end of the following night local time (22:00 UT in the lower panel of Figure 2 corresponds to 07:00 LT), ionosphere reacted with a decrease in the critical frequency. This result confirms the conclusions of [10], where dependence of the ionospheric reaction on the local time was studied with the GPS TEC measurements.

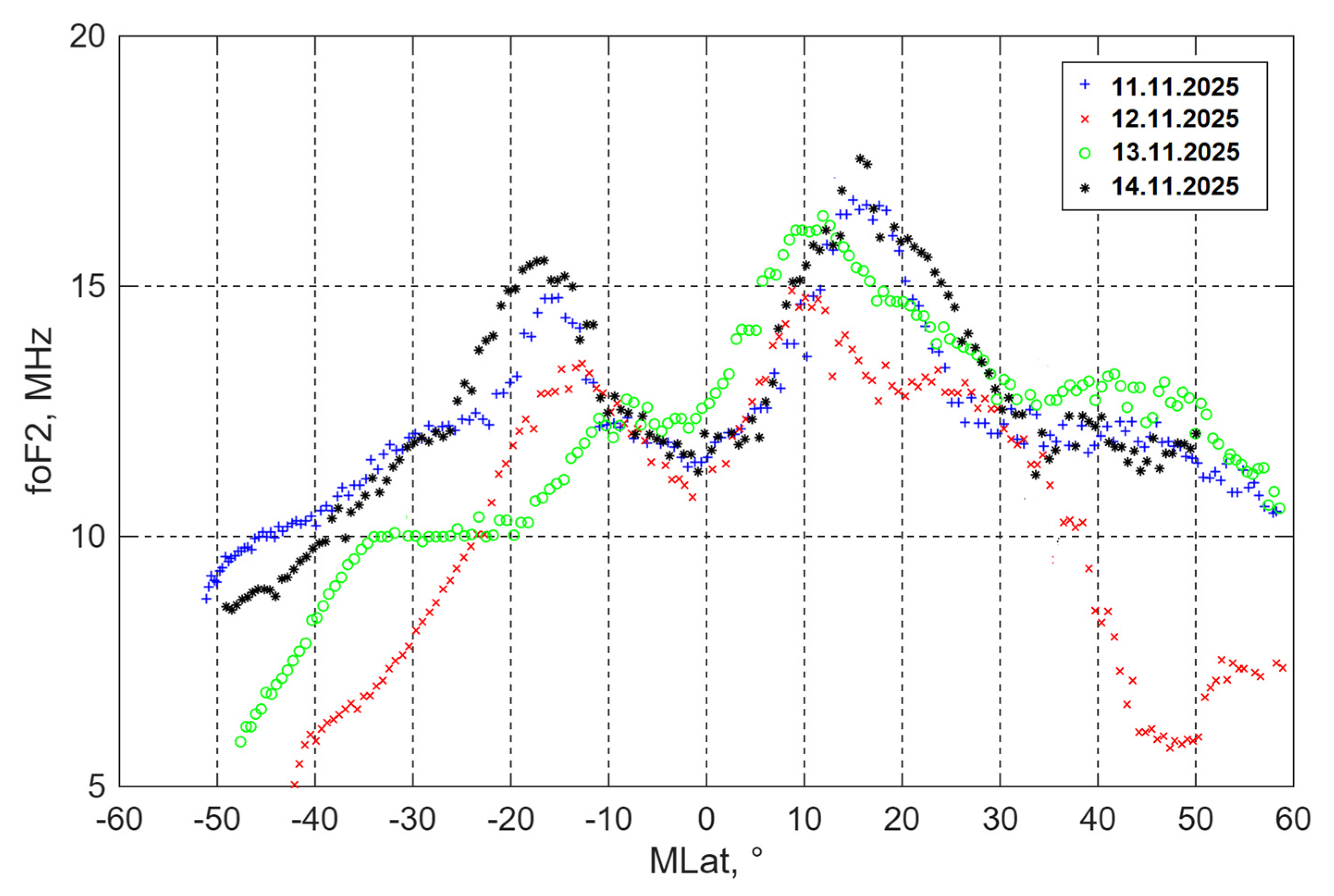

4.2. Topside Sounding Results

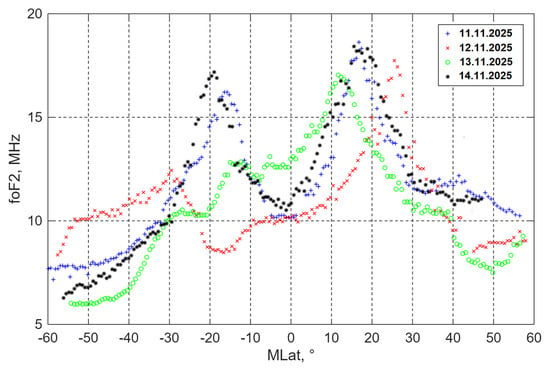

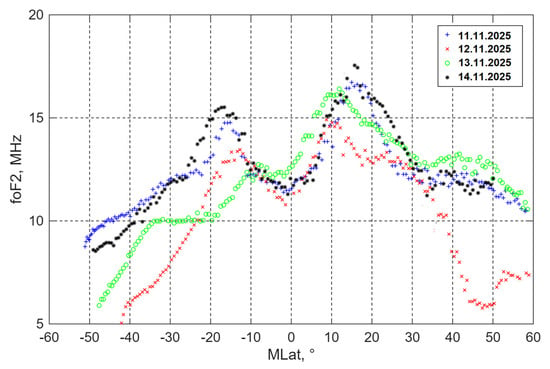

The topside ionospheric sounder installed on the Ionosfera-M spacecraft, operating on the same principles as ground-based ionosondes, makes it possible to track changes in the electron concentration over the entire latitude range. Because of the fact that the satellites have sun-synchronous orbits, the variations in the parameter values can be considered as a quasi-fixed longitude distribution (except the polar caps). Figure 3 demonstrates the latitudinal distributions of the critical frequency along the daylight part of the satellite Ionosfera-M No. 3 orbit, which crossed the equator at ~15 LT. Figure 2 shows the critical frequency variations versus the geomagnetic latitude on 11–14 November in the time interval (05–06 UT) and in the longitudinal sector of 135–160° E. The blue line demonstrates the reference distribution obtained on 11 November on the eve of the storm. The northern crest maximum of the equatorial anomaly (EA) is located at 16° N and is equal to 17.5 MHz, while the southern crest maximum is located at 18° S and is equal to 16.5 MHz. The valley minimum between the crests is at 0° and is equal to 10 MHz.

Figure 3.

Critical frequency variations in the ionosphere along the orbit of the Ionosfera-M No. 3 spacecraft on 11–14 November 2025, at 5–6 UT in the longitudinal sector 135–160° E.

The red curve was recorded at 05:06 UT on 12 November, four hours after the storm’s onset, when the Dst index reached its minimum value. It shows a distinct poleward shift in the EA crests by approximately 10° in latitude. Notably, the southern EA crest has disappeared while the amplitude of the northern crest remains largely unchanged. This apparent northward displacement of a substantial layer characterized by elevated electron density likely resulted in an observable increase in the critical frequency compared to the median values throughout all day of 12 November across middle latitudes.

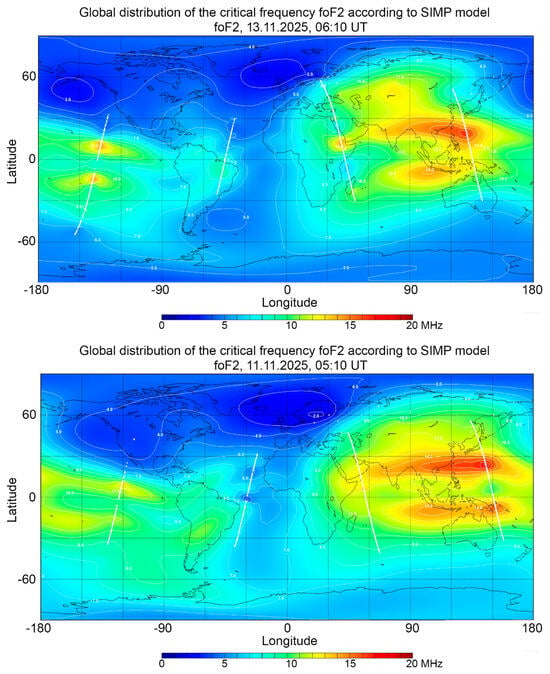

In contrast, the green curve corresponds to measurements taken at 05:06 UT on 13 November 2025. Herein, the critical frequency associated with the F2 layer peak at the northern EA crest had diminished by 1 MHz, and no discernible southern crest activity could be detected. Additionally, as evidenced by the critical frequency map derived from the SIMP ionospheric model [27] incorporating both terrestrial and space observation datasets (see Figure 4), the EA structure appears significantly compressed along longitudinal coordinates (upper panel of Figure 4). Specifically, whereas prior to the storm event (as depicted in the upper panel of Figure 2) at local time 15:00 there is a sign of the active phase in the EA shape, on the second day of the storm this moment is observable at the eastern boundary of the EA with one active crest (bottom panel of Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Maps of the critical frequencies according to the SIMP model with assimilation of observation data from the Ionosfera-M spacecraft No. 1, 2, 3, 4. Upper panel—13 November 2025 06:10 UT, lower panel—11 November 2025 05:10 UT. Satellite traces are indicated by white lines.

Note that the crests took their standard position on 14 November (black line, Figure 3).

To compare data from the ground-based ionosonde in Khabarovsk and the LAERT 3 topside sounder, upper panel of Figure 2 shows red circles corresponding to the topside sounding data as the satellite passed through a geomagnetic latitude of 50° in the longitudinal sector of 135–160°. The patterns of the data are generally similar, but some longitudinal differences prevent a complete match.

The phenomenon of the “super-fountain effect” was first confirmed experimentally for the magnetic storm of 5–6 November 2001 in [28]. Simultaneously with the increase in ionization during magnetic storms, a significant (up to 10°) poleward shift in the EA crests was also observed [28,29,30,31].

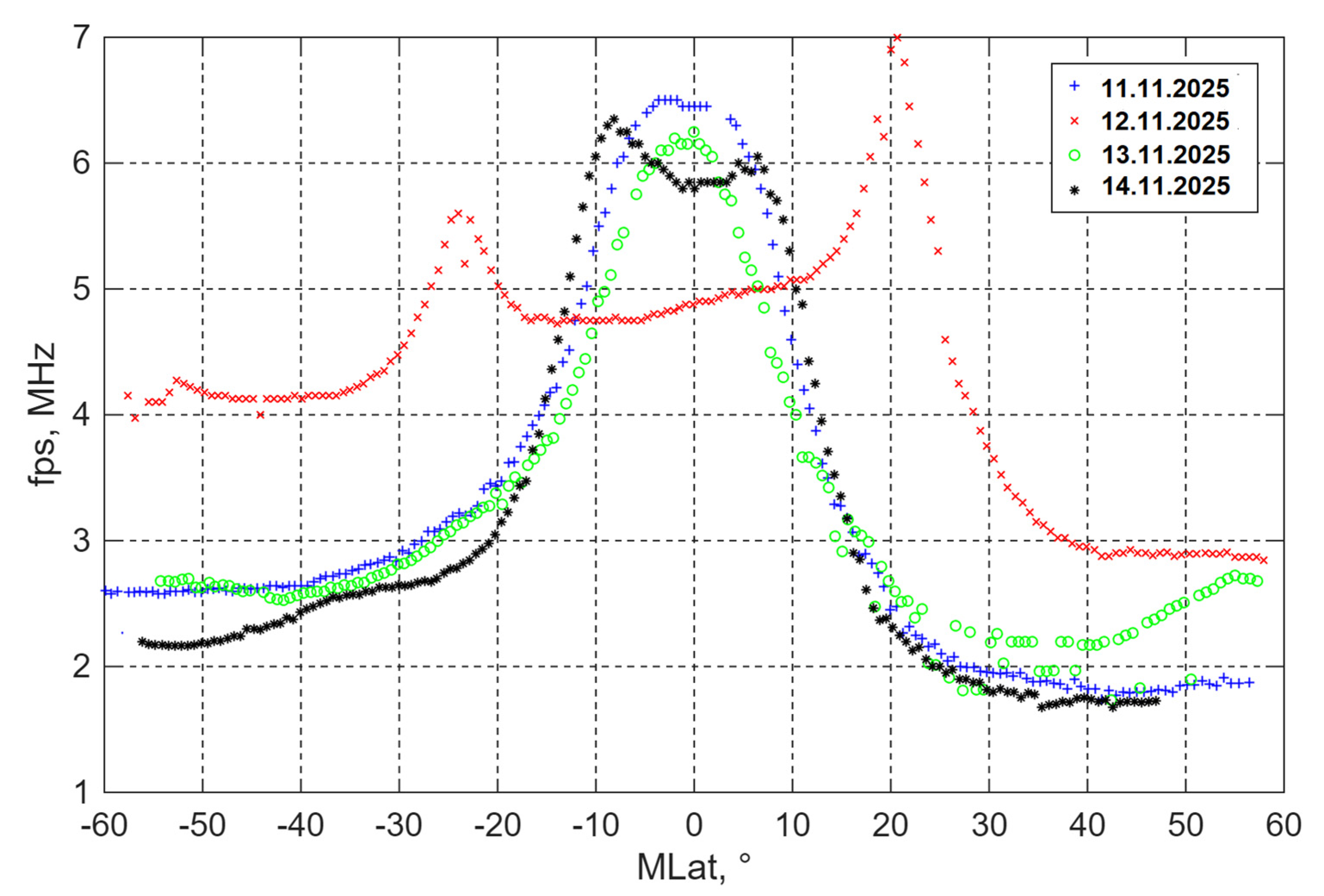

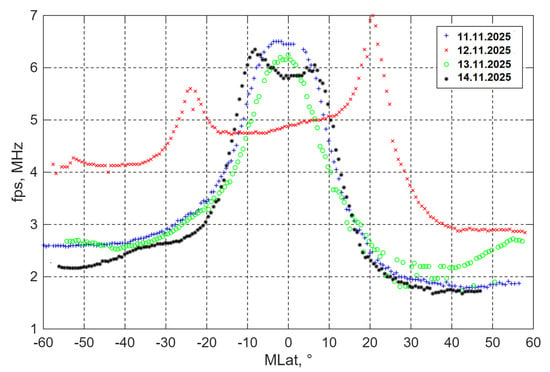

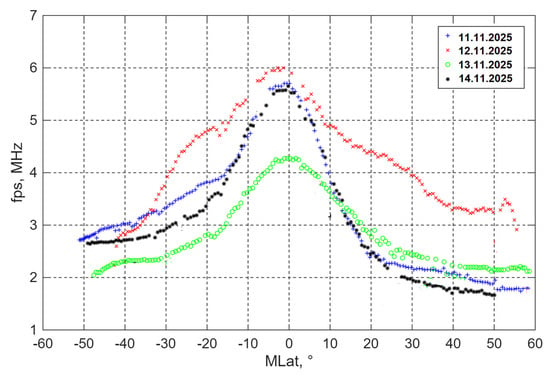

It is interesting to follow up the variations in the local plasma frequency at the satellite altitude 830 km (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Distributions of plasma frequencies along the orbit of the Ionosfera-M No. 3 spacecraft at the altitude of the spacecraft on 11–14 November 2025, at 5–6 UT in the longitudinal sector 135–160° E.

In quiet conditions, the distribution has a single maximum (Figure 5, blue line) above the geomagnetic equator caused by the fountain effect. Four hours after the storm’s onset, the plasma distribution pattern at an altitude of 830 km changes sharply. The magnetic field change and corresponding east-directed electric field were so strong that they dramatically enhanced the fountain effect, with EA crests also appearing at an altitude of 830 km, with the latitudes of their maxima corresponding to the red curve in Figure 3. Plasma frequencies increased twofold across the entire latitude range outside the EA. This effect was no longer observed on 13 November and later.

Even stronger expansion of the equatorial anomaly was registered during the 10–11 May 2024 superstorm [32]. The interplanetary and equatorial electric fields demonstrated the strong outreach which is considered the reason for the super-fountain effect leading to the equatorial anomaly expansion.

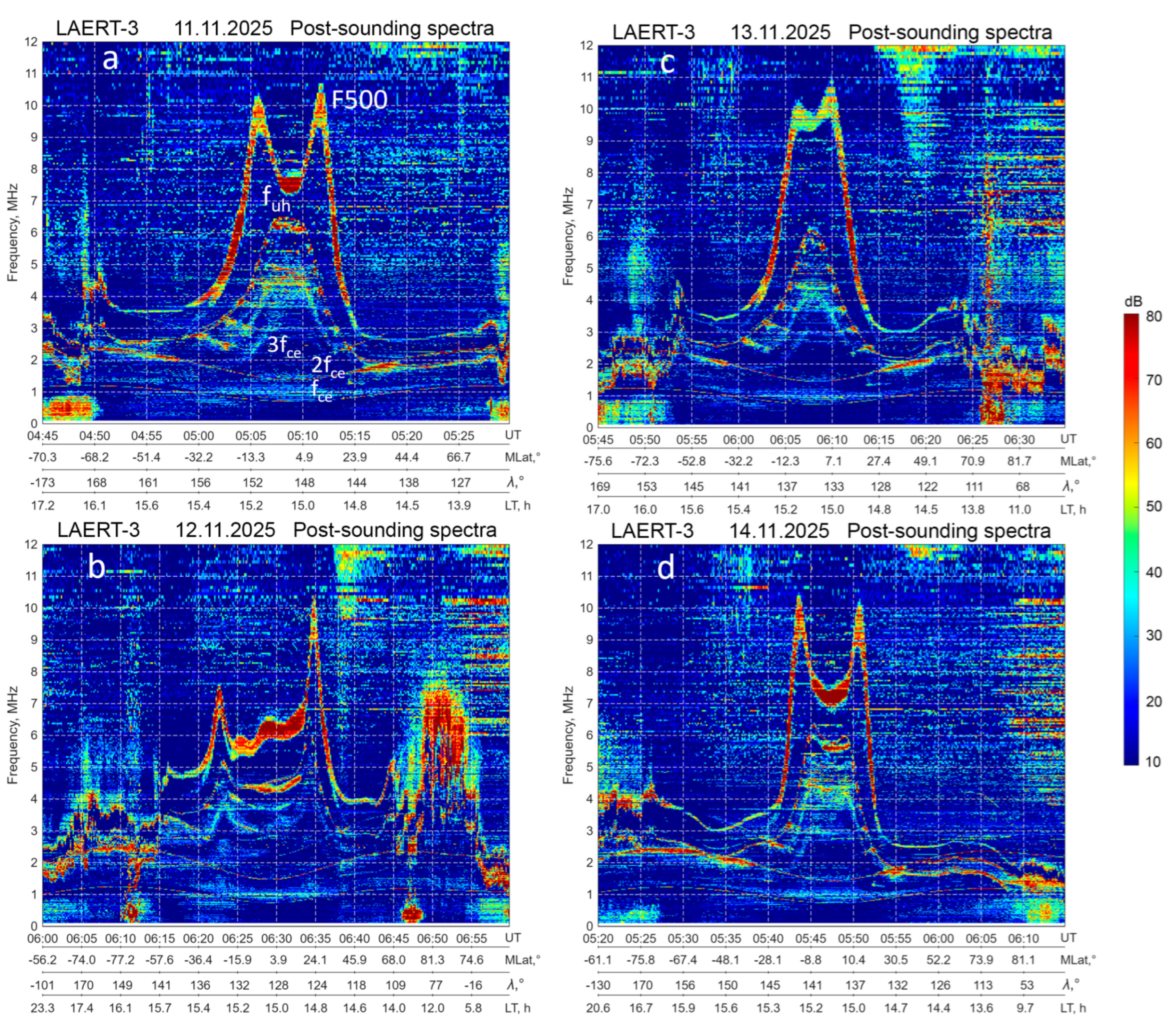

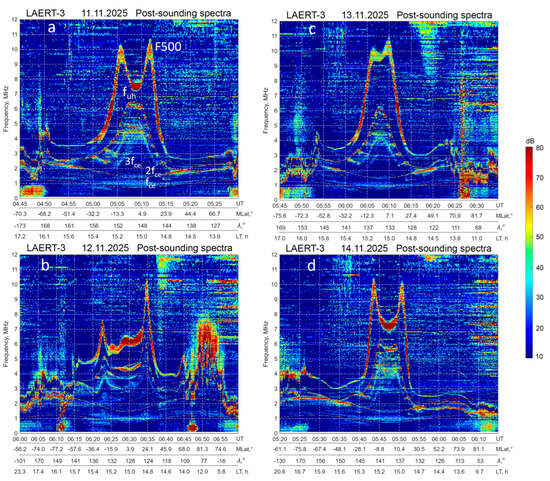

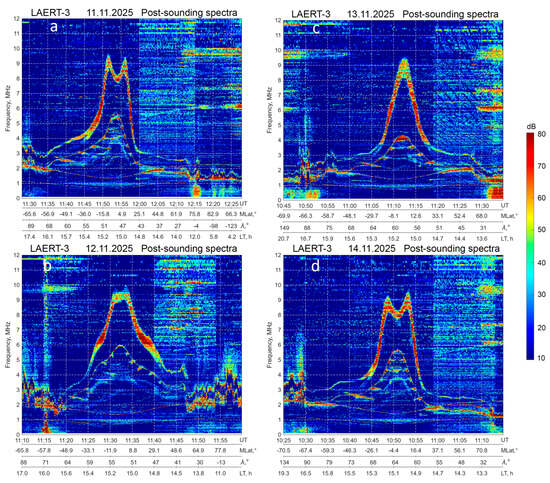

In the relaxation sounder mode [18] when we observe the plasma excitation by the sounder pulses on the characteristic plasma frequencies (electron cyclotron frequency and its harmonics, local plasma and upper hybrid frequencies), we have an opportunity to follow their variations along the satellite orbit. We measure the signal at every point 2.5 ms after the sounder pulse emission and as a consequence we obtain the additional trace of the signal reflected from the apparent height corresponding to the 2.5 ms delay (nearly 500 km altitude, and marked in Figure 6 as F500). All these diagrams, including the local plasma frequency, are demonstrated at the dynamic spectra presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

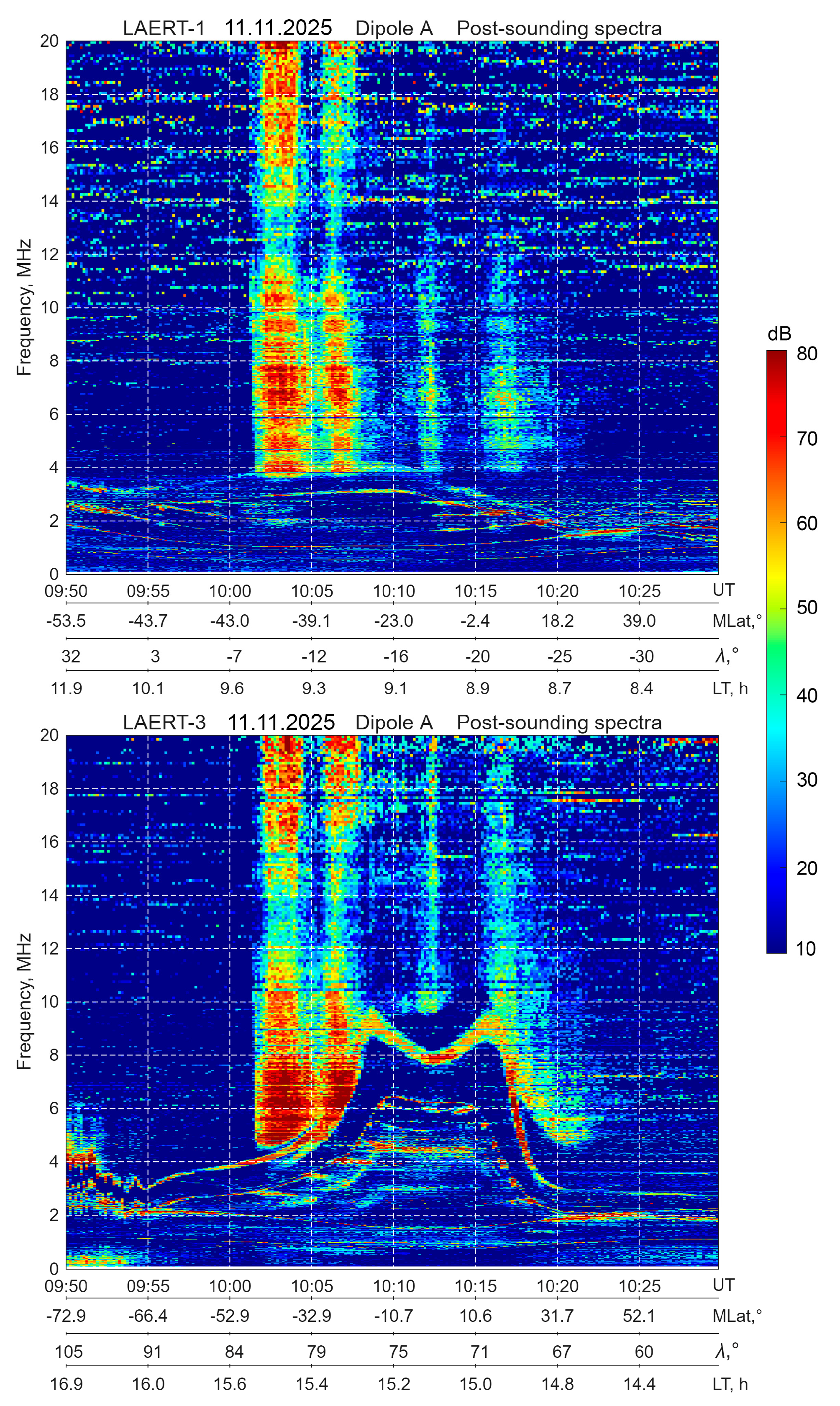

Dynamic spectra obtained by the satellite Ionosfera-M No. 3 passes: (a) 11.11.2025; (b) 12.11.2025; (c) 13.11.2025 and (d) 14.11.2025. Time periods are the same as those demonstrated in Figure 5 depicting the variations in the local plasma frequency.

In all four panels the dynamic spectra in relaxation sounding mode within the frequency band 0.1–12 MHz are demonstrated. They were registered by Ionosfera-M No. 3 satellite during its daytime (near 03 PM) passes from the southern to northern hemisphere. The orbits are the same as in Figure 3 and Figure 5 with the results scaled from the topside ionograms demonstrated. In Figure 6a the characteristic frequencies are marked from top to bottom: reflection trace from 500 km altitude F500, upper hybrid frequency at the satellite altitude 820 km, and harmonics of electron cyclotron gyrofrequency (fce, 2fce, 3fce). At the altitude 500 km one can see the double-crest structure of the equatorial anomaly but at the satellite altitude (except Figure 6b) we see only one maximum. The values of the upper hybrid frequency, in cases when the plasma frequency is much higher than the electron cyclotron frequency, are very close to the local plasma frequency and are practically identical to those in Figure 5 for corresponding times: Figure 6a—blue curve at Figure 5, Figure 6b—red curve at Figure 5, Figure 6c—green curve at Figure 5, and Figure 6d—black curve at Figure 5.

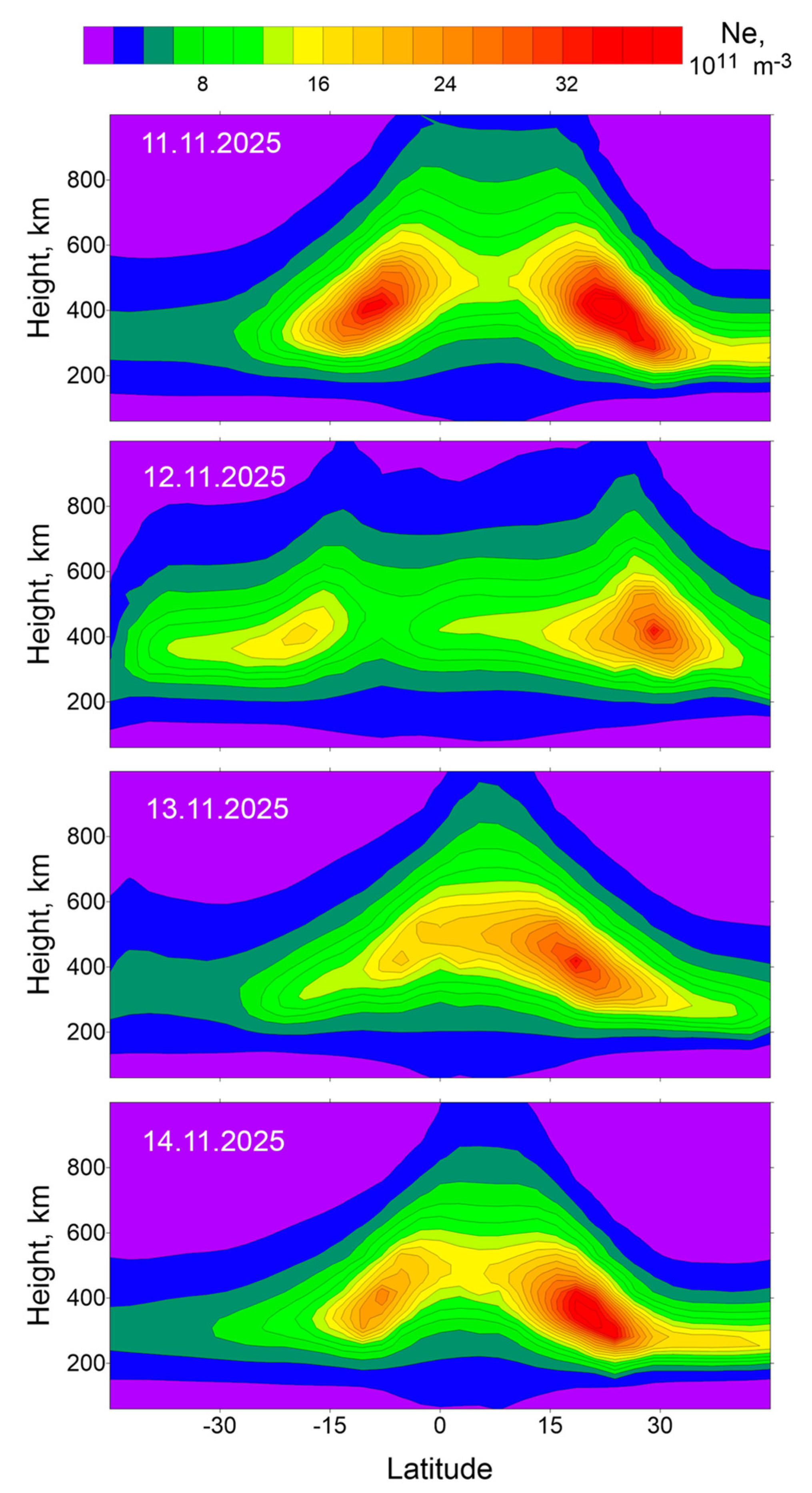

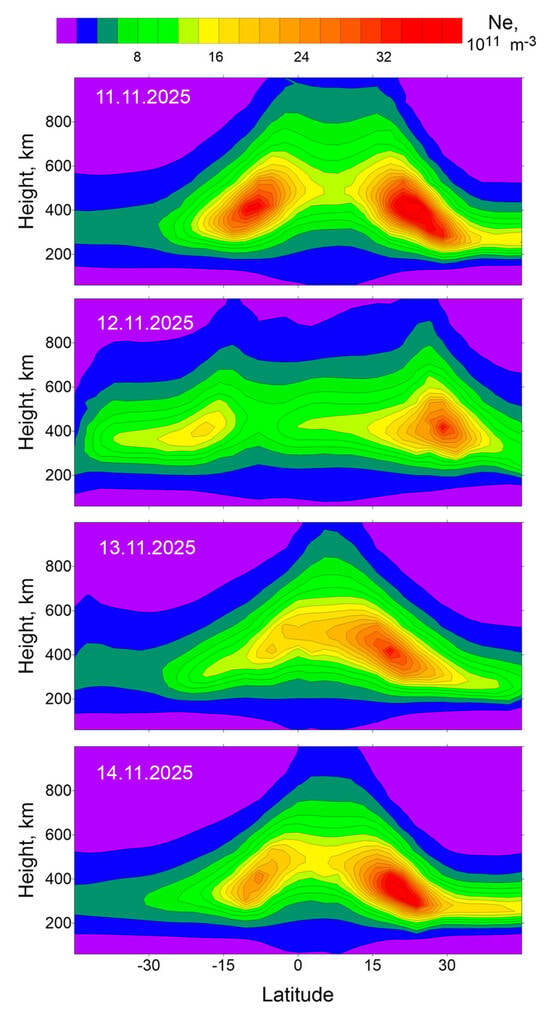

Reduction in the topside ionograms allows deriving the altitude profiles of the electron concentration from the satellite’s altitude to the peak of electron density. The electron density at lower altitudes is obtained using modeled altitude cross-sections. It is a method for reconstructing the total electron density profile based on the NeQuick model, proposed by Prof. S.M. Radicella (ICTP) and described in [33]. The architecture of the NeQuick model allows calculating the Ne(h) profile using the peak parameters and the thicknesses of the F2, F1, and E layers as reference values. In the general case [34], the foF2 and M3000F2 (or hmF2) values are specified by the coefficients of the CCIR (or URSI) model. The parameters of the maxima of the lower ionosphere are determined by simple empirical relationships based on the solar zenith angle and the level of solar activity. In our case, we use the values of foF2, hmF2, and the thickness of the upper part of the F2 layer (B2u), obtained from satellite ionograms, as initial parameters. The resulting latitudinal cross-sections, combining the results of Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Tomographic reconstruction of the EA dynamics during the geomagnetic storm 11–14 November 2025 within the longitudinal sector 135–160° E.

4.3. Revealing the Longitudinal Differences in the Ionosphere Reaction on the Geomagnetic Storm

Let us examine the observation results in the 20–40° E longitudinal sector, where the onset of the geomagnetic storm occurred late in the night (3 UT corresponds to 6 LT). As noted above, the ground stations in this range responded with a decrease in the electron concentration from the first hours of the disturbance. We will also examine the results from the LAERT 3 topside sounder.

In Figure 8, the reference distribution obtained the day before the magnetic disturbance is shown by the blue line. A day later, the EA crests became less pronounced (Figure 6, red curve), and plasma frequencies across the entire range decreased almost twofold. The effect of the EA crest shift toward the poles is not observed. On 13 November, an asymmetry in the ionospheric behavior is observed in the southern and northern hemispheres. In the northern hemisphere, plasma frequencies are higher than the reference values, which is also reflected in the ground-based ionosonde data (Figure 2, upper panel). In the southern hemisphere, at mid latitudes, the plasma frequency increased relative to the first day of the storm but did not reach the reference values. The southern EA crest completely disappears, similarly to what was observed in the Far East. On 14 November, the ionosphere is practically the same as the reference value of 11 November.

Figure 8.

Critical frequency distributions versus the geomagnetic latitude along the spacecraft orbits on 11–14 November 2025, at 11–12 UT in the longitudinal sector 20–40° E.

To compare data from the ground-based ionosonde in Rostov-on-Don and the LAERT 3 topside sounder, red circles are shown on the upper panel in Figure 2. These circles correspond to the topside sounder data as it passed over the geomagnetic latitude of 45° in the longitudinal sector of 20–40°. The values of the critical frequency are generally consistent.

The results of the ionospheric plasma frequency (fps) measurements at the spacecraft altitude of 830 km are surprising (Figure 9). The observation results for 11 November wereused as the reference fps distribution (blue line in Figure 9). On 12 November, four hours after the onset of the geomagnetic storm, despite a drop in the foF2 critical frequency, the electron density in the upper ionosphere increased, with fps in the northern hemisphere nearly doubling (red curve in Figure 9). However, 24 h later, fps dropped sharply. In the southern hemisphere and near the geomagnetic equator, it was 25% below the reference value, while in the northern hemisphere, it was close to the reference value. By 14 November, the effects of the storm were no longer visible.

Figure 9.

Distributions of plasma frequencies along the orbit of the Ionosfera-M No. 3 spacecraft at the altitude of the spacecraft on 11–14 November 2025, at 11–12 UT in the longitudinal sector of 20–40° E.

Similarly to Figure 6 we controlled the variations in the local plasma frequency scaled from the topside ionograms and presented in Figure 9 by images of relaxation sounder mode for the same passes of the Ionosfera-M No. 3 satellite presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Dynamic spectra corresponding to the satellite Ionosfera-M No. 3 passes are demonstrated in Figure 8 and depict variations in the local plasma frequency. Panel (a) for 11.11.2025; (b) 12.11.2025; (c) 13.11.2025 and (d) 14.11.2025.

4.4. Small-Scale and Regional Storm-Induced Irregularities

The storm-time variations in the ionosphere demonstrated in Figure 3 and Figure 9 and followed by detailed discussion are global in nature. The time scale is from several hours up to several days, and we see the global inflation and emptying of the ionosphere at different phases of the geomagnetic storm development.

Another very important factor typical to the effects of geomagnetic storm in the ionosphere is generation of local instabilities in the form of the irregular structures of different sizes as one can see in the right edge of Figure 6b. Because of limited size of the paper, we provide only two examples of such formations: one in the polar region, and one in the equatorial ionosphere.

The chaotic variations in electron concentration mentioned above are presented in more detail in Figure 11.

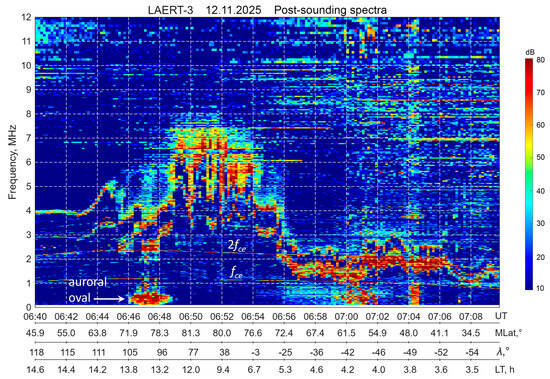

Figure 11.

Dynamic relaxation spectrum over the north polar ionosphere at 06:40–07:10 UT 12 November 2025.

In comparison with spectra presented in Figure 6a,c,d for northern hemisphere where the plasma frequency at altitude 500 km does not exceed 2–3 MHz, in Figure 11 we see the rise in the plasma frequency till 7.5 MHz, which corresponds to the electron concentration 6 × 105 cm−3. This increase in the electron concentration does not look like the smooth line. From 06:49 till 06:54 we observe continuous jumps of the plasma frequency down to 3 MHz and back up to more than 7 MHz (nearly six times changes in the electron concentration). We can interpret these variations as plasma patches in the polar ionosphere [35]. One can find a lot of similarity between our result and what is described in [35]. This irregular structure may be connected also with another factor: when looking at the local time and geomagnetic latitude we should accept the fact that the structure is within the cusp sector which during the active phase of geomagnetic storm may contribute to the plasma irregularity formation.

From both sides of this irregular increase in electron concentration in polar ionosphere, we see the splashes of low frequency emission at f < 1 MHz which is generated by low energy electrons precipitating within the auroral oval.

Another strong anomaly was observed in equatorial ionosphere nearly 21 LT when the post sunset reversal of the equatorial electric field causes the formation of equatorial anomaly [36]. Satellites Ionosfera-M No. 1 and No. 2 which orbit located just in this sector of local time register multiple plasma bubbles regularly [18], including the giant plasma bubbles. Formation of plasma bubbles is usually accompanied by the strong F-spread.

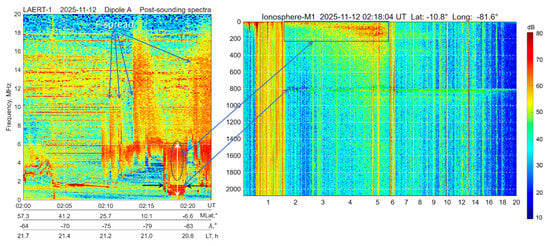

Figure 12 (left panel) shows the extremely deep and giant in spatial extension (~1250 km) plasma bubble registered on 12 November 2025 between 02:15 and 02:20. Its depth is marked in the figure by white double-arrow line, and its time–spatial extension by two black arrows. We see a drop of the plasma frequency from nearly 6.5 MHz up to 0.5 MHz what corresponds to the electron concentration drop from 5 × 105 cm−3 to 3 × 103 cm−3, i.e., more than two orders of magnitude. Such strong irregularities in the low latitudes create serious problems for the radio communication and navigation [37].

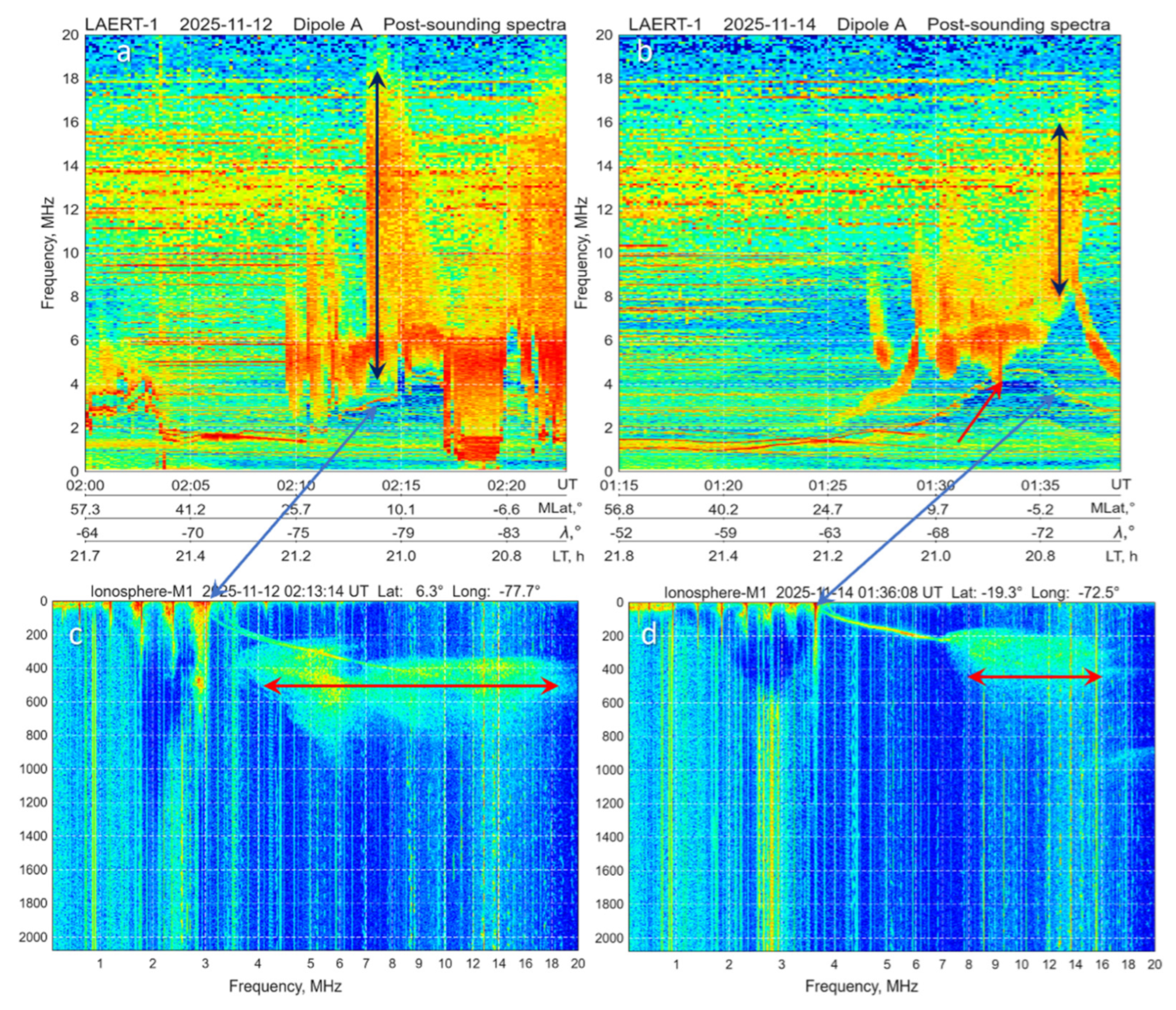

Figure 12.

Left panel—dynamic relaxation spectrum collected at 02:00–02:25 UT on 12 November 2025. Right panel—dynamic relaxation spectrum collected at 01:15–01:40 UT on 14 November 2025.

Every vertical line on the dynamic spectrum corresponds to one ionogram. In the right panel of Figure 12 the topside ionogram registered at 02:18:04 UT is shown, approximately in the time where the white double-arrow is located in the left panel. The noises from 6.5 to 1.5 MHz encircled by the blue oval in the left panel correspond to noises marked by the blue rectangle in the right panel ionogram. The figures are connected by the double blue arrow.

However, the most striking feature is the horizontal line in the right panel ionogram marked by the lower blue double arrow at the altitude 820 km. It is the sounding signal reflection from the ground surface. Because the ionosphere is so rarefied, there is no plasma to reflect the sounding pulse and it travels to the ground and reflects back.

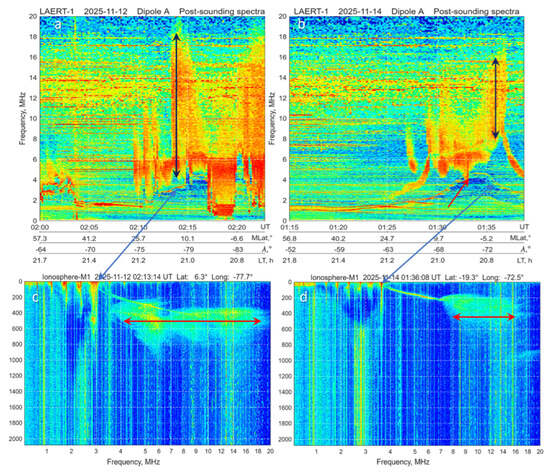

In the left panel of Figure 12 one can see the smeared wide strips of noise marked by the blue arrows. They are marked as F-spread but for those who are not familiar with this presentation of ionospheric information we prepared special demonstration depicted in Figure 13. We demonstrate how the F-spread effect looks at the dynamic spectra and at traditional ionograms. Two different moments were selected: one in disturbed conditions on 12 November 2025 (Figure 13a), and another one during the storm relaxation on 14 November 2025 (Figure 13b). The satellite passes are practically identical due to the orbit configuration. At both figures the smeared strips which we interpret as F-spread are present simultaneously with plasma bubbles. The difference is in the scale of phenomena: in the first case we observe multiple and extended in frequency F-spread periods while in the second one the less intensive F-spread and a very small plasma bubble of 10 s duration approximately on 01:33 (marked by the red arrow). On both figures the vertical double-arrow lines are located in the strip of F-spread which shows the frequency expansion of the F-spread and the time (indicated in bottom axis). For these moments the traditional topside ionograms are demonstrated at the panels of Figure 13c,d.

Figure 13.

(a)—dynamic relaxation spectrum collected at 02:00–02:25 UT on 12 November 2025; (b)—dynamic relaxation spectrum collected at 01:15–01:40 UT on 14 November 2025; (c)—topside ionogram collected at 02:13:14 UT on 12 November 2025; (d)—topside ionogram collected at 01:36:08 UT on 14 November 2025.

At both upper figures, the black double-arrow lines mark the frequency band of F-spread corresponding to moment when the appropriate topside ionogram was collected. The red double-arrow horizontal lines on the topside ionograms in the bottom panel indicate the same frequency band at the altitude 500 km: 3.5–19 MHz on 12 November and 7.5–16 MHz on 14 November. The inclined blue double-arrow lines show the position of the local plasma resonance at the relaxation spectrum.

As a conclusion it is necessary to underline the following. As it was demonstrated by Figure 12 and Figure 13, the dynamic spectra and topside ionograms can register the same phenomena in the ionosphere with different character of visualization. But the advantage of the dynamic spectra is that in one image we are able to analyze the situation along the orbit for the long time intervals while to make the same analysis using ionograms we need to observe a large number of images. In the presented examples where intervals of 25 min duration are shown it would be necessary to analyze 150 ionograms instead of one picture, having in mind that sounding is carried out every 10 s.

5. Topside Sounder as an Astrophysical Device

The topside sounder working as a radiospectrometer is able to register not only signals generated in the ionosphere or penetrating from the ground, industrial noises, but also the signals from outside of the near-earth space. We reported several cases of the solar type III bursts registered by the LAERT [18]. With the launch of the second pair of Ionosfera-M satellites there are cases when the same burst was registered by two satellites simultaneously when both of them were over the sunlit hemisphere. It is not simple to detect what event in the solar corona was the source of the registered burst and its identification has a special interest to reveal the physical mechanism of the burst’s generation.

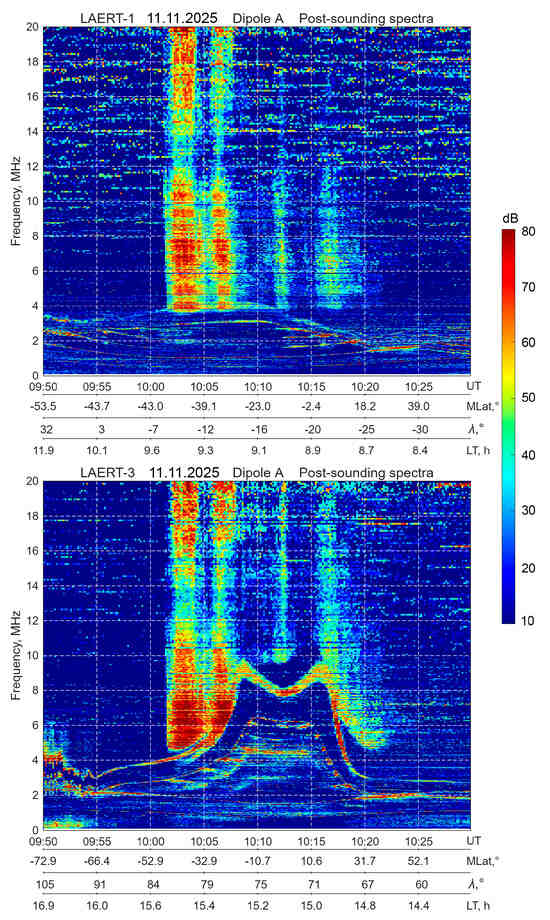

According to [38] powerful type III bursts at the frequencies of 10–30 MHz were observed on the days when the active region was either near the central meridian or 40–60° east or west of it. The active region AR 4274 near the solar central meridian produced the intensive flare of X 5.16 class on 10:04 UT.

The most intriguing is that the two satellites Ionosfera-M No. 1 and No. 3 registered simultaneously the series of extremely strong type III solar bursts (Figure 14) and contributed to identifying one of the key indicators/precursors behind the subsequent geomagnetic storm discussed in this article.

Figure 14.

Type III solar radio bursts registered by the Ionosfera-M No. 1 satellite (upper panel) and Ionosfera-M No. 3 (lower panel) simultaneously with the X5.1 solar flare at 10:05 UT 11 November 2025.

According to our year-long monitoring, the first two splashes registered by both satellites were the most intensive for the whole year of observation. The most detailed analysis of this event will be the subject of a separate publication.

6. Discussion

This article presents a part of results obtained by the satellite constellation Ionozond during development of geomagnetic storm on 11–14 November 2025. The complete collection of data for this storm requires more extended time including the data from other instruments from the satellite payload which registered the ionosphere parameters during this storm. Our intention was to demonstrate the wide opportunities of the satellite constellation, especially the topside sounding technology and HF radiospectrometry. This is the first scientific study after the completion of flight tests and the commissioning of the system.

Comparison of satellite data with ground-based measurements showed their complete agreement and confirmed the presence of a longitudinal effect of a geomagnetic storm associated with the local time of onset of the main phase of a geomagnetic storm. This is a solid addition to the previous works devoted to studies of longitudinal effect of the geomagnetic storm impact on the ionosphere [10,39,40,41]. In comparison with ground-based observations, we were able to study the storm development in the topside ionosphere. The most unexpected result was the detection of strong variations at the satellite orbit altitude of nearly 820 km, especially the formation of equatorial anomaly crests and their strong poleward shift during the main phase of the storm (Figure 5). The vertical cross-section of the equatorial region and its dynamics were also impressive (Figure 7). It confirms the results of [32] obtained during superstorm 10–11 May 2024. The strong increase in the electron concentration in the polar cap in the form of plasma patches (Figure 11) continues studies provided by the SWARM satellite constellation [35].

In the framework of the continuing discussion on the ionospheric tomography using the beacon technology [42], we can state that the advantage of our method is in the direct measurements of vertical profiles of electron concentration, while classical tomography ispartly based on the mathematical modeling. Another advantage is that we are able to reconstruct vertical cross-sections at any longitude sector of the globe while the satellite beacon tomography is tied to the tomographic ground receivers’ chain.

7. Conclusions

The revival of the topside sounding technology [18] marks a new stage in the development of experimental methods for ionospheric research. New topside sounders offer significantly broader capabilities than previous generations of similar instruments. The combination of vertical sounding and high-frequency radiospectrometry allows for a more detailed study of the ionosphere’s internal structure. We are only at the beginning of the application of these new instruments, which promises new, perhaps unexpected, results and discoveries. For example, we just opened the door to broad capabilities of the HF radiospectrometry (Figure 12 and Figure 13), permitting us to provide the expert opinion on the ionospheric conditions over the whole orbit in one image. We did not touch yet the capabilities to get additional information from plasma resonances.

To reveal the new features of the longitudinal effect of the ionospheric reaction on the geomagnetic storm, the four satellites are located over different longitudes and latitudes. So, this publication should be considered as the first step of more profound analysis of the geomagnetic storm impact on the ionosphere.

Nevertheless, let us sum up the outcome of present publication.

- For two longitudinal sectors in Western Pacific (135–160° E) and Europe (20–40° E) for different phases of strong geomagnetic storm 11–14 November 2025 the latitudinal profiles of the critical frequency foF2 and the local plasma frequency were obtained at the satellite orbit altitude 820 km fos for the local time ~15 LT in the maximum phase of the equatorial anomaly development. The satellite data were compared with the data of ground-based ionospheric vertical sounding.

- The results obtained for these latitudinal profiles were supported by the dynamic relaxation spectra for the same orbits. It gives the perfect picture of difference in the equatorial anomaly development at the altitude 500 km and at the satellite orbit altitude, especially formation of two-crest anomaly on 12 November 2025 at the satellite altitude.

- The formation of the increased concentration anomaly by a series of plasma patches over the northern polar cap on 12 November 2025 was demonstrated.

- Reconstruction of the vertical structure of the equatorial anomaly with vertical profiles of electron concentration scaled from topside ionograms and its dynamics during the geomagnetic storm development.

- Formation of giant plasma bubbles within the equatorial anomaly during the main phase of the geomagnetic storm.

- F-spread dynamics in disturbed and quiet conditions.

- Registration of the series of intensive type III solar bursts by two satellites simultaneously coinciding in time with the X5.16 solar flare from active region XR 4274.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation S.P.; conceptualization; investigation, data curation, N.K.; investigation, data curation, visualization V.D.; software, visualization, writing—review and editing, K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was carried out with the support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (theme Upravlenie-FFWG-2022-0005, state registration No. 122042500013-4).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

For providing the geophysical indices data we acknowledge: WDC for Geomagnetism, Kyoto, Japan, NASA/GSFC’s Space Physics Data Facility’s OMNIWeb, and Space Weather Data Portal at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have conflicts of interest.

References

- Schuster, A. The origin of magnetic storms. Proc. A 1911, 85, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Ferraro, V.C.A. A new theory of magnetic storms. Terr. Magn. Atmos. Electr. 1933, 38, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasofu, S.-I.; Chapman, S. The development of the main phase of magnetic storms. J. Geophys. Res. 1963, 68, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesen, C.G.; Crowley, G.; Roble, R.G. Ionospheric effects at low latitudes during the March 22, 1979, geomagnetic storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1989, 94, 5405–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D.; Laštovička, J. Effects of geomagnetic storms on the ionosphere and atmosphere. Int. J. Geomagn. Aeron. 2001, 2, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Blagoveshchenskii, D.V. Effect of geomagnetic storms (substorms) on the ionosphere: 1. A review. Geomagn. Aeron. 2013, 53, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D. Reaction of the F region to geomagnetic disturbances (review). Heliogeophysical Res. 2013, 5, 1–33. Available online: http://vestnik.geospace.ru/php/download.php?id=UPLF3c9aba28bb38a163c785a61c7198ae2c.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Akasofu, S.-I. A review of studies of geomagnetic storms and auroral/magnetospheric substorms based on the electric current approach. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2021, 7, 604750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berényi, K.A.; Heilig, B.; Urbář, J.; Kouba, D.; Kis, Á.; Barta, V. Comprehensive analysis of the ionospheric response to the largest geomagnetic storms from solar cycle 24 over Europe. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2023, 10, 1092850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, M.S.; Budnikov, P.A.; Pulinets, S.A. Global ionospheric response to intense variations of solar and geomagnetic activity according to the data of the GNSS global networks of navigation receivers. Geomagn. Aeron. 2023, 63, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S. Prospects of topside sounding. In WITS Handbook; Chapter 3; SCOSTEP Publishing: Urbana, IL, USA, 1989; Volume 2, pp. 99–127. Available online: https://izmiran.ru/projects/IK19/db/articles/wits.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Benson, R. Four decades of space-borne radio sounding. URSI Radio Sci. Bull. 2010, 2010, 24–44. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7909284 (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Karpachev, A. Sub-Auroral, Mid-Latitude, and Low-Latitude Troughs during Severe Geomagnetic Storms. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpachev, A.T. Equatorial anomaly according to the Interkosmos-19 data and IRI model: A comparison. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 67, 3202–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotonaeva, N.G. Registration of delayed lower traces on SS MIR ionograms during radio-sounding from heights below the F2 layer maximum. Heliogeophysical Res. 2013, 3, 25–39. Available online: http://vestnik.geospace.ru/php/download.php?id=UPLF9f5bafef173c499d03acfd8b45dfe5ba.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Nayak, C.; Buchert, S.; Yiğit, E.; Ankita, M.; Singh, S.; Tulasi Ram, S.; Dimri, A.P. Topside low-latitude ionospheric response to the 10–11 May 2024 super geomagnetic storm as observed by Swarm: The strongest storm-time super-fountain during the Swarm era? J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2025, 130, e2024JA033340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilevsky, M.; Chernyshov, A.; Pulinets, S.; Lukyanova, R.; Petrukovich, A. Secrets of the Earth’s ionosphere and the Ionosonde project for their disclosure. Zemlya Vselennaya 2025, 3, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.; Tsybulya, K.; Depuev, V.; Danilov, I.; Pulinets, M. Ionospheric topside sounding revival. Adv. Space Res. 2026, 77, 2574–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzounov, D.; Pulinets, S.; Davidenko, D.; Rozhnoi, A.; Solovieva, M.; Fedun, V.; Dwivedi, B.N.; Rybin, A.; Kafatos, M.; Taylor, P. Transient Effects in Atmosphere and Ionosphere Preceding the 2015 M7.8 and M7.3 Gorkha–Nepal Earthquakes. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 757358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerospace & Defence. Available online: https://www.aerospace-and-defence.com/esa-analyses-impacts-november-2025-solar-storm-3-cmes-earth-a-2234835b9110a63fc0c49764ea83ecbd/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- European Space Agency. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Space_Safety/Space_weather/Lessons_from_the_November_2025_solar_storm (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Chilingarian, A.; Sargsyan, B.; Kozliner, L.; Karapetyan, T. Solar neutron and muon detection on November 11, 2025: First simultaneous recovery of energy spectra. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2512.07859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Service. Available online: https://wdc.kugi.kyoto-u.ac.jp/aeasy/index.html (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Jackson, J.E. The reduction of topside ionograms to electron-density profiles. Proc. IEEE 1969, 57, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuev, V.H.; Pulinets, S.A. A global empirical model of the ionospheric topside electron density. Adv. Space Res. 2004, 34, 2016–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.A.; Depuev, V.H. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the global longitude irregularities in the ionosphere and their model representation. In IRI Task Force Activity 2003, Trieste, Italy, 16–20 June 2003; IC/IR/2004/1; ICTP Publishing: Trieste, Italy, 2004; pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lapshin, V.B.; Danilov, A.D.; Mikhailov, V.V.; Tsybulia, K.G.; Denisova, V.N.; Mikhailov, A.V.; Deminov, M.G.; Karpachev, A.T.; Shubin, V.N. The SIMP model as a new state standard for the ionospheric electron density distribution (GOST 25645.146). In Proceedings of the 25th All-Russian Conference on Radio Wave Propagation, Tomsk, Russia, 3–9 July 2016. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tsurutani, B.; Mannucci, A.; Iijima, B.; Abdu, M.A.; Sobral, J.H.A.; Gonzalez, W.; Guarnieri, F.; Tsuda, T.; Saito, A.; Yumoto, K.; et al. Global dayside ionospheric uplift and enhancement associated with interplanetary electric fields. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, A08302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astafyeva, E.I.; Afraimovich, E.L.; Kosogorov, E.A. Dynamics of total electron content distribution during strong geomagnetic storms. Adv. Space Res. 2007, 39, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, A.J.; Tsurutani, B.T.; Iijima, B.A.; Komjathy, A.; Saito, A.; Gonzalez, W.D.; Guarnieri, F.L.; Kozyra, J.U.; Skoug, R. Dayside global ionospheric response to the major interplanetary events of October 29–30, 2003 “Halloween Storms”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L12S02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wan, W.; Liu, L. Responses of equatorial anomaly to the October-November 2003 superstorms. Ann. Geophys. 2005, 23, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aa, E.; Chen, Y.; Luo, B. Dynamic Expansion and Merging of the Equatorial Ionization Anomaly During the 10–11 May 2024 Super Geomagnetic Storm. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, B.; Radicella, S.M.; Pulinets, S.; Depuev, V. Modelling bottom and topside electron density and TEC with profile data from topside ionograms. Adv. Space Res. 2001, 27, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitinger, R.; Zhang, M.-L.; Radicella, S.M. An improved bottomside for the ionospheric electron density model NeQuick. Ann. Geophys. 2005, 48, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Yin, F.; Luo, X.; Jin, Y.; Wan, X. Plasma patches inside the polar cap and auroral oval: The impact on the spaceborne GPS receiver. J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2019, 9, A25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Le, H.; Zhang, R.; Huang, H.; Li, W. Occurrence of ionospheric equatorial ionization anomaly at 840 km height observed by the DMSP satellites at solar maximum dusk. Space Weather 2021, 19, e2020SW002690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, L.M.M.; Tongkasem, N.; Supnithi, P.; Hozumi, K.; Nishioka, M. Equatorial Plasma Bubble (EPB) observations at low latitude regions of ASEAN. In Proceedings of the United Nations Workshop on the International Space Weather Initiative, Vienna, Austria, 26–30 June 2023; Available online: https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/psa/activities/2023/ISWI2023/presentations/ISWI2023_11_05.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Melnik, V.N.; Konovalenko, A.A.; Rucker, H.O.; Boiko, A.I.; Dorovsky, V.V.; Abranin, E.P.; Lecacheux, A. Properties of Powerful Solar Type III Bursts at Decameter Wavelengths. Radio Phys. Radio Astron. 2010, 1, 271–280. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, N.; Rao, P.B. Dependence of ionospheric response on the local time of sudden commencement and the intensity of geomagnetic storms. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1990, 52, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendillo, M.; Narvaez, C. Ionospheric storms at geophysically-equivalent sites—Part 2: Local time storm patterns for sub-auroral ionospheres. Ann. Geophys. 2010, 28, 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remya, S.N.; Unnikrishnan, K.; Thampi, S.V.; Sreekumar, H. Longitudinal variation in the ionospheric responses to two successive geomagnetic storms in early Solar Cycle 25. Adv. Space Res. 2026; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunitsyn, V.E.; Tereshchenko, E.D. Ionospheric Tomography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; 262p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.