Abstract

Precipitation in high mountain areas is of critical importance as these regions are major sources of freshwater, supporting river basins, ecosystems, and downstream communities. Changes in precipitation regimes in these regions can have cascading impacts on water availability, agriculture, hydropower, and biodiversity. The present study aims to give new information about precipitation variability in high mountain regions of Bulgaria (Musala, Botev Peak, and Cherni Vrah) and to assess the role of large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns for the occurrence of extreme precipitation months. The study period is 1937–2024, and the classification of extreme precipitation months is based on the 10th and 90th percentiles of precipitation distribution. The temporal distribution of extreme precipitation months was analyzed by comparison of two periods (1937–1980 and 1981–2024). The impact of atmospheric circulation was evaluated by correlation between the number of extreme precipitation months and indices for the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO). Results show a statistically significant decrease in winter and spring precipitation at Musala and Cherni Vrah, and a persistent drying tendency at Cherni Vrah across all seasons. The frequency of extremely wet months in winter and autumn has sharply declined since 1981, whereas extremely dry months have become more common, particularly during the cold season. Precipitation erosivity also exhibits station-specific responses, with Musala and Cherni Vrah showing reduced monthly concentration, while Botev Peak retains pronounced warm-season erosive rainfall. Circulation analysis indicates that positive NAOI phases favor dry extremes, while positive WeMOI phases enhance wet extremes. These findings reveal a shift toward drier and more seasonally uneven conditions in Bulgaria’s alpine zone, increasing hydrological risks related to drought, water scarcity, and soil erosion. The identified shifts in precipitation seasonality and intensity offer essential guidance for forecasting hydrological risks and mitigating soil erosion in vulnerable mountain ecosystems. The study underscores the need for adaptive water-resource strategies and enhanced monitoring in high-mountain areas.

1. Introduction

Mountain regions are particularly sensitive to climate change and play a critical role as “water towers,” supporting river basins, ecosystems, and downstream communities [1,2,3,4]. Global warming intensifies the hydrological cycle and is linked with changes in the seasonality, frequency, and intensity of extreme precipitation [5]. These impacts are often amplified in mountain regions, where rates of warming can be elevation dependent [6]. The dependency of climatic variables like precipitation on elevation gradients is a defining feature of mountain environments, although this relationship is often difficult to quantify precisely due to reduced data quality and availability at high elevations [7,8]. Observations from recent decades have documented a global increase in precipitation extremes, and many projections for the 21st century indicate a further intensification of these trends, although with clear spatial and seasonal inhomogeneities [9,10]. The intensification of extreme precipitation is accompanied by quantitatively measurable changes in its intensity, duration, and frequency, which have direct implications for the design of hydraulic structures and water resources management [11]. At a regional scale, this manifests as more frequent wet and dry extremes, leading to considerable socio-economic impacts and posing risks to water management, agriculture, and biodiversity [2,12,13,14,15]. Southeastern Europe, and Bulgaria in particular, has shown a high sensitivity to such extremes in the hydrological cycle [2,16]. Extreme and intense precipitation are well documented as a factor in increased surface runoff, erosion, flooding and landslides in Bulgaria, especially in mountainous regions with steep terrain and sensitive watersheds [17,18,19].

The Balkan Peninsula, situated in a transition zone between the temperate and subtropical belts, is influenced by a complex interaction between Mediterranean and continental processes [20]. The Mediterranean region is considered a climate-change “hot-spot” due to the combined effects of warming, altered circulation, and water deficit [21]. Extensive reviews indicate that there is no universal, statistically robust monotonic trend in precipitation over the Mediterranean; the signal varies depending on the season, study period, and sub-region, to the point that even the IPCC AR6 report contains partial inconsistencies on the topic [22]. This complexity is evident in Bulgaria also, where studies have documented a general, though often not statistically significant, drying trend since the 1980s [1,17,23], a significant decrease in high-mountain areas [24], and yet also a recent increase in precipitation totals during the last decade [25]. This highlights the need for updated, high-resolution regional analyses.

Two dominant factors shape the precipitation regime over the Balkans, including Bulgaria: the influence of the Mediterranean Sea, characterized by active cyclogenesis and winter precipitation maxima, and the continental influence from Eurasia, which leads to higher precipitation during the warm half of the year [20]. The dynamic boundary between these regimes is a sensitive indicator of climate change. The influence of large-scale atmospheric circulation on this regime is paramount. However, the specific role of teleconnections like the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) remains a subject of considerable debate for the Balkan region [26]. While the NAO is a primary driver of European climate variability [27], many studies find only a weak or statistically insignificant correlation between the NAO index and precipitation in Bulgaria [1,2,20]. In contrast, closer examination suggests that the NAO’s impact is non-linear; strongly negative NAO phases (below −2σ) are often connected with the activation of Mediterranean cyclones, which are primary drivers of heavy precipitation and floods in Bulgaria [2,26].

For Bulgaria, the highest mountain peaks (Musala (2925 m a.s.l.), Cherni Vrah (2290 m a.s.l.), Botev Peak (2376 m a.s.l.)) reflect the combined effect of orographic forcing and large-scale synoptic circulation. The alpine zone is more often under the influence of Atlantic cyclones, while Mediterranean systems bring intense precipitation to the southern slopes. As a result of orographic lifting, local thermal dynamics, and the positioning of cyclones, a complex “mosaic” is formed where extreme precipitation is both frequent and highly variable in space. Case studies, such as the extremely wet year of 2014 in Bulgaria, confirm that the interaction between regional circulation and local factors can lead to strong anomalies in precipitation and terrestrial water storage, causing widespread flooding [2].

Given the complex and sometimes contradictory findings for the region, the present study aims to provide an updated assessment of recent precipitation tendencies in the high-mountain areas of Bulgaria and to examine the occurrence of extremely dry and wet months. To achieve this, three specific objectives are formulated: (1) to evaluate trends in seasonal and annual precipitation for three high-mountain stations; (2) to identify and characterize extreme monthly precipitation using percentile thresholds; (3) to investigate the links between these extremes and large-scale circulation indices—North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAOI) and Western Mediterranean Oscillation Index (WeMOI), taking into account seasonality and possible non-linearities.

By focusing on how circulation patterns shape extreme monthly precipitation in Bulgaria’s high mountains, this study aims to clarify the drivers of hydrological extremes in complex terrain and reduce uncertainties associated with strong spatial variability. The results can support more consistent climate diagnostics and early-warning practices, and can inform planning in water-resources management, hydropower operation, agriculture, and nature protection. In addition, the findings are relevant for the optimization of the mountain observation network and for coordination between civil protection and river-basin authorities, including in cross-border settings where Mediterranean cyclones often produce transboundary impacts.

2. Study Area and Data Collection

The present study focuses on three high-altitude meteorological stations situated on major mountain summits in Bulgaria: Cherni Vrah (2290 m a.s.l.) in the Vitosha Mountains, positioned south of the Sofia Basin; Botev Peak (2376 m a.s.l.), the highest elevation of the Balkan (Stara Planina Mountains) in its central sector; and Musala (2925 m a.s.l.) in the Rila Mountains, which is the highest point in both Bulgaria and the entire Balkan Peninsula (Figure 1, Table 1). Each station represents a unique microclimate shaped by local orography and atmospheric circulation.

Figure 1.

Location of meteorological stations used in the research.

Table 1.

List of meteorological stations used in the research.

The Musala station is strongly exposed to atmospheric circulation from all directions. The climate is similar to an alpine type, characterized by well-defined vertical gradients. The area records the lowest temperatures among the stations considered and is characterized by the most persistent and longest-lasting snow cover. The Botev Peak station is located on the Main Ridge of Stara Planina—an east–west oriented mountain chain that acts as a barrier between northern and southern air masses. Temperatures are very low, but higher than those at Musala due to the lower elevation. Strong and persistent winds are typical, limiting snow accumulation on the ridge. The area favors enhanced cloudiness and orographic precipitation, particularly during air mass intrusions from the north and northwest. Cherni Vrah is a massive, domed summit and the highest point of an isolated mountain south of the Sofia Basin. The local climate is frequently influenced by valley circulation and temperature inversions. Wind speeds are generally lower than at Musala and Botev, although frequent intensifications occur during westerly and northwesterly advection [28,29].

In the Balkan Peninsula, including Bulgaria, precipitation is driven by North Atlantic and Mediterranean cyclones, summer thermal convection, and orographic effects due to the region’s mountainous topography [20]. In the studied areas, precipitation and extreme weather patterns are shaped by three main factors: (1) the exposure to moisture-bearing airflows from the Mediterranean compared to northern slopes (Cherni Vrah station), (2) variations in ridge continuity and the resulting lee-side effects (Botev Peak station), and (3) elevation-driven thermodynamics, which regulate the balance between snow and rain and influence the potential for convection [20,24].

The paper is based on monthly precipitation totals from three high-mountain meteorological stations: Musala, Cherni Vrah, and Botev Peak. The primary data were provided by the National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology (NIMH) of Bulgaria, which manages the national reference observation network. These stations were selected based on the availability of long-term meteorological measurements in the high-mountain regions of Bulgaria and time series with no gaps. The main observation period is 1937–2024, and to identify the changes in the precipitation regime and the occurrence of extremely cold and extremely warm months, it was divided into two sub-periods: 1937–1980 and 1981–2024. For station Botev Peak, the data are limited to 1946–2024 due to the later initiation of continuous monitoring.

The influence of atmospheric circulation on precipitation variability and the occurrence of extreme precipitation months is assessed using the station-based NAO index for December–March (NAOIdjfm) and the Western Mediterranean Oscillation index (WeMOI). The NAO index is calculated as the normalized sea-level pressure difference between Lisbon, Portugal, and Stykkishólmur/Reykjavík, Iceland, and is regularly updated by the Climate Analysis Section at NCAR, Boulder, USA [30]. The WeMOI is defined as the difference between standardized surface atmospheric pressure at San Fernando (Cádiz, Spain) and Padua (Italy), and effectively captures variability associated with cyclogenesis in the western Mediterranean basin [31]. WeMOI data were obtained from the Climate Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/moi/, accessed 23 December 2025).

3. Methods

The Precipitation Concentration Index (PCI) was employed to quantify the temporal concentration and seasonality of precipitation [32,33,34,35,36]. The PCI is a dimensionless indicator widely applied in climatological studies to assess the degree of intra-annual precipitation variability [30,31]. In this study, annual PCI values, calculated for each year of the study period, were determined following the formula proposed by De Luis et al. [32] and Lukić et al. [35]:

where PCIann is the annual value of PCI and Pi is the monthly precipitation.

PCI values below 10 indicate a uniform distribution of precipitation throughout the year, reflecting low temporal concentration. For PCI values above 10, precipitation becomes increasingly unevenly distributed, and three categories are typically distinguished, ranging from moderate to high concentration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of intra-annual precipitation distribution based on the Precipitation Concentration Index (PCI).

Seasonal precipitation totals were calculated from the monthly dataset, with the seasons defined as follows: winter (December, January, and February); spring (March, April, and May); summer (June, July, and August); and autumn (September, October, and November). Trends in both seasonal and annual precipitation totals were analyzed using linear regression implemented in the AnClim software, v4.6.31 [37]. The software provides the regression equation for the time series, from which the slope, representing the rate of change over time (expressed in mm per 10 years for precipitation), was derived. The statistical significance of the observed trends was assessed using the t-test for the slope b1 in the model y = b0 + b1x, which in simple regression is equivalent to the t-test for the Pearson correlation coefficient r (t = r√(n − 2)/√(1 − r2)). For robustness, we also applied Spearman’s rank correlation and the Mann–Kendall trend test.

Extreme precipitation months were identified by comparing monthly totals to the 10th and 90th percentile thresholds of the probability distribution estimated from observed records [38]. Months with precipitation below or equal to the 10th percentile were classified as extreme dry months, whereas those at or above the 90th percentile were classified as extreme wet months. The 10th and 90th percentiles were selected because they are commonly used in climatological studies to identify extreme events, providing a balance between capturing sufficiently rare events and maintaining an adequate sample size for robust statistical inference [39,40].

To evaluate the annual variability of precipitation, as well as to identify dry and wet periods and assess rainfall erosivity, the Angot Precipitation Index (API) was employed [41,42,43]. This index provides a clear quantitative measure of precipitation regime characteristics and is defined as the ratio between mean daily precipitation for a given month and mean daily precipitation for the corresponding year:

Here, p is calculated as p = q/n, where q is the total monthly precipitation and n is the number of days in the corresponding month. The parameter P represents the average daily precipitation and is defined as P = Q/365, where Q is the annual precipitation total. The API was calculated for every single month of the study period.

According to the API, precipitation is classified into five categories based on precipitation attributes and its potential to cause soil erosion (Table 3).

Table 3.

Precipitation Sensitivity Classes for Soil Erosion Based on the Angot Precipitation Index (API) (according to Dumitraşcu et al. 2017) [44].

The impact of atmospheric circulation on precipitation variability was examined using correlation analysis between the North Atlantic Oscillation index for December–March (NAOIdjfm) and the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMOI), on the one hand, and the number of extreme precipitation months and the monthly Angot precipitation index, on the other. The selection of the NAOI for the December–March period is justified by the heightened activity of the NAO during these months and by the pivotal role of winter atmospheric circulation in the mid-latitudes of Europe in determining the spatial and temporal distribution of precipitation in the region [27,30,45].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Annual Cycle of Precipitation

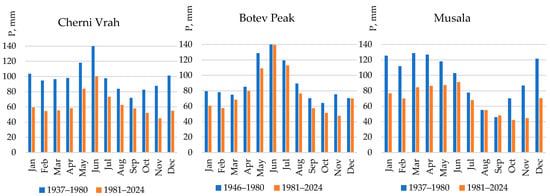

The precipitation regime in the studied areas is generally characterized by a maximum in May–June, although at Musala it occurs earlier (April–May). A secondary peak is observed in December–January. Monthly precipitation amounts are lower in the 1981–2024 period compared to the 1937 (1946)–1980 period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Monthly mean precipitation for 1961–1990 and 1991–2020.

At Cherni Vrah, the maximum monthly precipitation remained in June but declined from 143 mm (1937–1980) to 100 mm (1981–2024), while the minimum shifted from September (72 mm) to November (45 mm), indicating drier late-autumn conditions. Botev Peak shows a similar pattern: June stays the wettest month, but the minimum moves from October to November and drops from 64 to 48 mm. Musala displays the strongest seasonal shift, with the maximum moving from March (129 mm) to June (91 mm), and the minimum shifting from September (46 mm) to October (42 mm). Long-term changes in seasonal maxima and extremes of precipitation have been identified by [16], in an analysis of Mediterranean and continental influences on precipitation regimes in the Balkans.

These findings may be interpreted as evidence of an intensification of dry conditions during autumn, a reduction in atmospheric moisture availability in early spring, and alterations in the large-scale circulation patterns that regulate precipitation regimes in Bulgaria’s high-mountain environments. The observed shifts are consistent with regional climate research [46] and imply potential consequences for water availability, snowpack dynamics, and related hydrological processes.

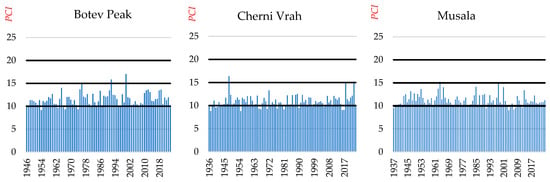

The calculated annual values of the Precipitation Concentration Index (PCI) reveal the pattern of intra-annual precipitation distribution. Figure 3 illustrates pronounced interannual variability, with some years exceeding the thresholds between the different classes defined in Table 2. In years when PCI values are below 10, precipitation is relatively evenly distributed throughout the months, indicating a lower risk of pronounced dry or wet seasons. However, the majority of the analyzed years exhibit PCI values between 10 and 15, i.e., within the class of “Weakly uneven” distribution. This indicates a moderate concentration of precipitation, typical of the climatic conditions in the study area, where a distinct precipitation maximum is observed in late spring and early summer. Higher PCI values (15 < PCI ≤ 20), recorded in certain years, reflect strongly expressed seasonality, in which most of the annual precipitation amount is concentrated in a limited number of months. Such values correspond to the “Uneven” distribution class, highlighting the vulnerability of the region to extreme events—intense precipitation over short periods and prolonged dry intervals. The graphical representation of the results (Figure 3) shows no evident trend during the analyzed period. Instead, alternating years with relatively even precipitation distribution and years with pronounced concentration are observed, which is likely driven by the influence of atmospheric circulation and regional climatic factors on the formation of the annual precipitation regime. The absence of PCI values above 15 at Musala reflects a more uniform precipitation regime, likely driven by its extreme elevation (2925 m) and synoptic-scale precipitation [47].

Figure 3.

Annual distribution of PCI. The horizontal solid lines indicate value limits between different classes of PCI.

4.2. Changes in Monthly and Annual Precipitation

Analysis of precipitation records for the three high-mountain stations (Botev Peak, Cherni Vrah, and Musala) reveals pronounced spatiotemporal variability since the 1980s, compared with the first half of the investigated period (1937–1980). At Botev, monthly precipitation during 1981–2024 generally ranges between 76.1 and 99.2% of the value for the reference period, with the most significant reduction observed in November (monthly precipitation amount is 63.1% of the precipitation for 1937–1980), Table 4. Cherni Vrah displays the strongest declines, with the largest deficits observed particularly in winter and late autumn—November (51.1%) and December (54.1%). In contrast, Musala shows a mixed signal: winter and spring precipitation is substantially reduced (≈60–70%), while late summer (August–September) slightly exceeds the baseline, reaching up to 104.8%.

Table 4.

Average monthly precipitation (1981–2024) relative to the 1937–1980 monthly averages (%).

Long-term trends (1937–2024) indicate decreases in annual precipitation at all stations, particularly at Cherni Vrah (−85.0 mm/decade) and Musala (−73.8 mm/decade), where the trend of annual precipitation is statistically significant (Table 5). Seasonal analysis shows that statistically significant negative trends occur at the stations Cherny Vrah and Musala in winter and spring (from −22 to −28 mm/decade). Studies of precipitation-change trends in other Balkan countries reveal comparable patterns. Feidas et al. [48] identify a clear and statistically significant decreasing trend in Greece’s annual precipitation totals over 1955–2001, driven primarily by a marked reduction in winter precipitation. A slight but statistically insignificant summer increase is observed at Botev (+2.1 mm/decade). For autumn, all three analyzed high-altitude stations show a statistically significant negative trend in precipitation, with the strongest precipitation at the Cherni Vrah station. Seasonal and annual precipitation trends at Botev Peak show a smaller decrease compared to Cherni Vrah and Musala, likely due to its geographic location and orographic setting. Being farther from the dominant western airflows and situated in an open area of Stara Planina, Botev Peak is less affected by large-scale atmospheric circulation changes, and local effects further moderate precipitation variability. The results are consistent with those of [49], which pointed out a decrease in precipitation, in particular winter precipitation, of greater magnitude in Southwestern Bulgaria and less in the Balkan Mountains, probably related to a reduced frequency of cyclonic circulation patterns favorable for precipitation.

Table 5.

Trend of seasonal and annual precipitation (in mm/10 years).

To characterize recent changes in seasonal and annual precipitation totals, we analyzed trends for the most recent 30-year interval (1995–2024) within the study period. Recent trends (1995–2024) highlight divergent patterns among the stations. At Botev, annual precipitation has increased (+38.9 mm/decade), primarily due to wetter winters (the trend is statistically significant with a value of +29.7 mm/decade) and summers (+12.8 mm/decade), despite a spring decline (−16.5 mm/decade), Table 5.

Musala also records a slight positive annual trend (+5.3 mm/decade), reflecting increases in winter (+21.1 mm/decade) and summer (+25.3 mm/decade). However, only the spring decrease (−28.4 mm/decade) is statistically significant. In contrast, Cherni Vrah continues to exhibit substantial drying, with an annual decrease of −55.1 mm/decade, mainly due to a statistically significant reduction in spring precipitation (−39.3 mm/decade). The decreases observed in winter (−8.2 mm/decade) and autumn (−19.6 mm/decade) are not statistically significant. The recent positive trends in winter, summer, and annual precipitation observed at Botev Peak and Musala may be associated with an increase in extreme precipitation events attributable to anthropogenic forcing [50,51]. In addition, enhanced variability in atmospheric circulation can contribute to such regional changes, particularly in transitional zones shifting from wetter to drier hydro-climatic regimes [51,52]. Significant increases in annual precipitation were indicated at many stations located in mountainous areas of western Serbia and eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina by [53], which links extreme precipitation variability to large-scale climate drivers, such as the NAO and WeMO, affecting mountain precipitation patterns.

4.3. Extreme Wet and Extreme Dry Months

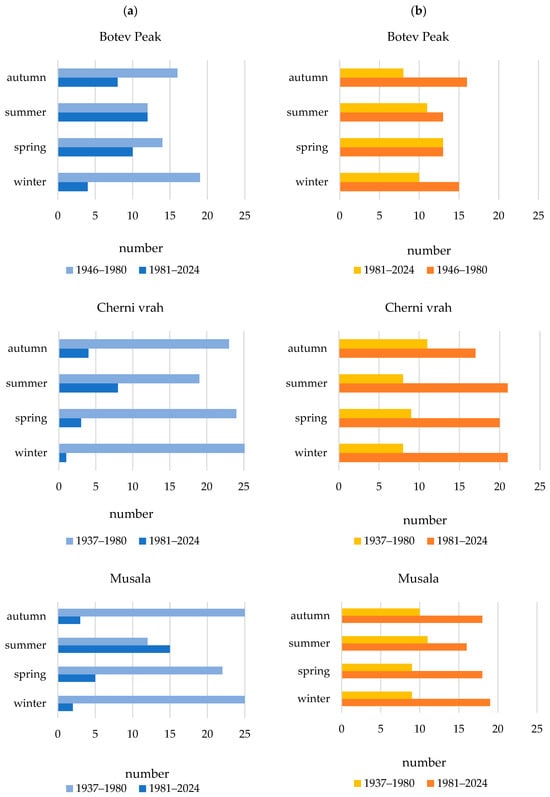

Analysis of extreme wet months across the three high-elevation stations (Botev Peak, Cherni Vrah, and Musala) reveals a marked decline in cold-season precipitation extremes over the past decades, accompanied by a partial shift toward summer months (Figure 4a). At Botev Peak, the total number of extreme wet months decreased sharply between the periods 1946–1980 and 1981–2024, with winter extremes falling from 19 to 4 months and autumn from 16 to 8, while spring showed a moderate reduction (14 to 10) and summer remained stable (12 months in both periods). Musala exhibited a similar pattern: cold-season wet extremes virtually disappeared in winter (from 25 to 2) and autumn (from 25 to 3), whereas in summer, wet extreme precipitation months increased from 12 to 15 months.

Figure 4.

Number of extreme precipitation months: (a) extreme wet months; (b) extreme dry months.

At Cherni Vrah, the reduction was even more pronounced. Whereas extreme wet months in 1937–1980 were relatively evenly distributed across seasons (19–26 months each), in 1981–2024 they nearly vanished, with only 1 event in winter, 3 in spring, 8 in summer, and 4 in autumn. These results indicate a strong decline in winter and autumn wet extremes across all stations, a moderate decrease or collapse in spring extremes, and a tendency for summer extremes to either persist or increase. This redistribution reflects a broader shift in extreme precipitation events from the cold season toward the transitional and warm seasons.

Analysis of extreme dry months across the high-elevation stations indicates a pronounced increase in dry conditions since the 1980s, with the strongest intensification during the cold season (Figure 4b). At Botev Peak, the number of winter dry months increased from 10 in 1946–1980 to 15 in 1981–2024, while autumn dry months rose from 8 to 16. Spring remained stable at 13, and summer increased slightly from 11 to 13. These changes indicate that dry conditions intensified primarily during the cold season, with relatively minor changes in the warmer months. At Cherni Vrah, the increase in dry months is even more pronounced. Winter dry months more than doubled, rising from 8 to 21, spring increased from 9 to 20, summer from 8 to 21, and autumn from 11 to 17.

This pattern reflects a pronounced and widespread drying trend across all seasons, consistent with the previously documented reduction in extreme wet months at this site. A comparable pattern is observed at Musala, where winter dry months increased from 9 to 19, spring from 9 to 18, summer from 11 to 16, and autumn from 10 to 18. The largest increases occurred during winter and spring, indicating a substantial rise in dry conditions across all seasons, though summer and autumn also experienced notable growth.

The analyses demonstrate a marked intensification of dry conditions across the Bulgarian mountains, particularly during the cold season, and highlight a seasonal redistribution of dryness that parallels the observed decline in extreme wet months. These changes indicate a clear shift from cold-season (winter and autumn) to warm-season (summer) dominance. While Cherni Vrah exhibits an almost complete collapse of extreme wet months, Botev Peak and Musala show strong seasonal redistribution, with winter and autumn events declining and summer extremes persisting or even increasing.

The results obtained in the present study coincide with the findings of other publications about precipitation variability in Bulgaria [54,55,56,57]. The authors indicated a decrease in precipitation in the mountainous part of Bulgaria at the annual or seasonal scale. According to [49], precipitation in the upper mountain regions drops considerably (by as much as 30%) during 1991–2020 compared to the 1961–1990 period. In Southwest Bulgaria, recent data show a reduction in both the frequency of extreme precipitation events and the number of days they occur—about 25% lower than during 1961–1990 [56]. The decrease in precipitation at Bulgaria’s high-mountain stations results in reduced snow cover and a lower maximum snow depth [57].

4.4. Precipitation Erosivity and the Distribution of Dry and Rainy Periods

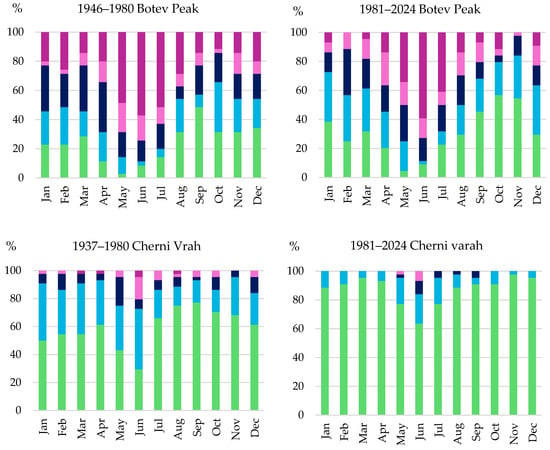

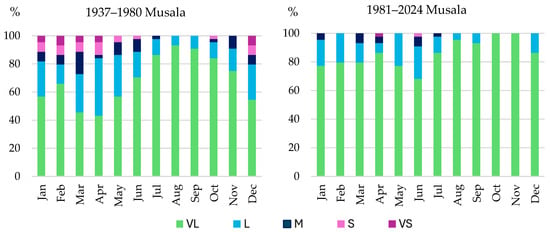

The analysis of the Angot Precipitation Index (API) at three high-mountain stations (Musala, Cherni Vrah, and Botev Peak) reveals distinct local patterns in precipitation concentration between the early (1937/1946–1980) and later (1981–2024) periods, especially in the stations Musala and Cherni Vrah. At these stations, the earlier decades were characterized by a broad distribution of API values, with substantial shares of low (1.00–1.49) and moderate (≥1.50) rainfall erosivity classes and occasional occurrences of API values above 2.50, particularly in spring and summer (Figure 5). This indicated frequent episodes of concentrated precipitation and higher erosivity. Higher API values are a consequence of increased precipitation totals. Similar findings have been reported by several publications [41,43,58]. After 1980, however, both stations became dominated by the months with very low precipitation erosivity class (API < 0.99), often exceeding 90% of monthly values (Figure 5). High erosivity classes became rare, and no months with very severe cases were recorded, reflecting a clear homogenization of monthly precipitation distribution. Seasonal differences highlight this transition: winter and autumn months, once more variable, are now almost exclusively in the very low class, while spring and summer have lost nearly all moderate and severe events.

Figure 5.

Percentage distribution of months across precipitation erosivity classes based on the Angot Precipitation Index (API) for two sub-periods. (VL—very low; L—low; M—moderate; S—severe; VS—very severe).

By contrast, Botev Peak shows a different trajectory. In 1946–1980, API values spanned all classes. The very rainy months with very severe precipitation erosivity (API > 2.50) are highly frequent in late spring and summer, reaching 49–57% of the respective month in the study period. In the later period (1981–2024), although very low and low values still accounted for a significant share, the persistence of high erosivity classes is also well pronounced.

Very severe cases continued to dominate from May to July, rising to 34% in May, 59% in June, and 41% in July. Thus, unlike Musala and Cherni Vrah, where precipitation concentration decreased, Botev Peak exhibits an intensification of extreme monthly precipitation in the warm season. These results align with findings from Serbia—another Balkan country, which show that June and July have the highest frequency of very severe precipitation erodibility classes [41].

In summary, the three stations illustrate contrasting high-mountain precipitation regimes in Bulgaria. Musala and Cherni Vrah show that after 1980, precipitation became more uniformly distributed across months, and extreme concentration events disappeared. In contrast, Botev Peak maintains and even amplifies its high summer erosivity, highlighting the role of local topography and atmospheric circulation in shaping precipitation variability. These differences have important implications for hydrological response and erosion dynamics, with Botev Peak remaining particularly vulnerable to intense rainfall events in late spring and summer. API values exceeding 2–2.5 indicate highly favorable conditions for the initiation of erosion processes. Considering the adverse consequences associated with surpassing this threshold, the implementation of soil erosion control measures is recommended in areas susceptible to erosion [58].

4.5. Impact of Atmospheric Circulation on Precipitation Variability

The relationship between large-scale atmospheric circulation and the number of occurrences of extreme wet and dry months was investigated using the North Atlantic Oscillation for the period from December to March (NAOdjfm) and the Western Mediterranean Oscillation Index (WeMOI) for the period 1937–2020 (Botev Peak: 1946–2020). Correlation coefficients between the indices and the number of extreme wet (w) and extreme dry (d) months are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Correlation between the number of extreme wet (w) and extreme dry (d) months and large-scale atmospheric circulation indices for the period 1937–2020 (for Botev Peak station 1946–2020).

Across all three high-mountain stations, the NAOdjfm exhibits a consistent pattern: negative correlations with the number of extreme wet months (−0.21 to −0.33) and positive correlations with the frequency of extreme dry months (0.11 to 0.27). This suggests that winters dominated by a positive NAO phase are associated with suppressed occurrence of extreme wet months and an increased likelihood of extreme dry months. The strongest negative NAO–wet months relationship is found at Botev Peak (−0.33), while Cherni Vrah and Musala show slightly weaker but still significant negative values. For dry extremes, the NAOdjfm influence is more pronounced at Cherni Vrah and Musala than at Botev Peak.

The WeMOI displays an opposite tendency. Positive correlations are observed between WeMOI and the number of extreme wet months at all stations (0.33 to 0.39), with Musala showing the strongest signal. This indicates that phases of the WeMOI conducive to cyclonic activity over the Balkans favor the occurrence of extreme wet months in the high mountains. For dry extremes, WeMOI is negatively correlated at Cherni Vrah and Musala, implying a mitigating effect on drought extremes. At Botev Peak station, however, the relationship is weakly positive, suggesting a reduced or locally modified influence. This is likely driven by local factors such as the station’s lee-side exposure, specific orography, and the dominance of local thermal convection over regional circulation patterns.

The correlation between the Angot precipitation index (API) and two large-scale atmospheric circulation indices, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAOIdjfm) and the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMOI), was assessed for the three high-mountain stations of Cherni Vrah, Musala, and Botev Peak (Table 7).

Table 7.

Correlation between Angot precipitation index (API) and large-scale circulation pattern for the period 1937–2024 (Botev Peak—1946–2024).

At all three stations, the NAO is predominantly negatively correlated with API, particularly during the cold season (November–March). At Cherni Vrah, significant negative correlations are observed in January–March and September–November. Musala shows weaker values, with significant negative correlations in February, September, and November (Table 7). At Botev Peak, significant negative correlations are also observed in winter and early spring, particularly in January, February, and March. These results indicate that a positive NAO phase is associated with reduced precipitation and rainfall erosivity in the Bulgarian high mountains, especially in late autumn and winter. This agrees with the well-established mechanism whereby positive NAO winters strengthen westerly circulation and displace storm tracks northward, resulting in drier conditions over southeastern Europe [27,30]. The persistence of negative correlations into September and November at Cherni Vrah and Musala suggests that NAO-related circulation anomalies can influence precipitation beyond the core winter season.

In contrast, the WeMO generally exhibits positive correlations with API, particularly in late winter, spring, and autumn. At Cherni Vrah, significant positive relationships occur from January to May, and in November and December, the latter being the strongest observed correlation in the dataset. Musala shows a similar pattern, with significant positive correlations from January to May and in December. At Botev Peak, significant positive values are concentrated in winter, notably in January (0.25) and December (0.40). These findings suggest that positive phases of the WeMO favor wetter conditions in the Bulgarian high mountains, particularly in winter and spring. This likely reflects enhanced cyclonic activity over the western and central Mediterranean, which can channel moist air toward the Balkans.

Station-specific differences are also apparent. Cherni Vrah demonstrates the clearest and most seasonally extended response to both indices, consistent with its exposure to Atlantic and Mediterranean circulation. Musala shows generally weaker but still significant correlations, while Botev Peak reflects a mixed signal, with strong NAO influence in winter and early spring but weaker WeMO correlations outside December and January. These regional differences highlight the combined role of regional circulation dynamics and local topography in shaping high-mountain precipitation variability [26,57]. Cherni Vrah’s precipitation regime is strongly affected by advections from Atlantic cyclones in winter, in addition to Mediterranean influences. Weaker, though still significant, correlations for Musala likely reflect the moderating effects of high-altitude orographic enhancement.

The findings of this study corroborate earlier research highlighting the influence of large-scale atmospheric circulation on precipitation patterns across the Balkan region. For instance, Peneva et al. [16] identified weak to moderate correlations between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and precipitation in the Balkans, while highlighting a stronger and more consistent relationship with the Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO), particularly for annual precipitation totals. The complex and often weak effect of NAO on the Balkan region was established by [26], based on the ERA5 dataset for the period 1940 to 2023. On the other hand, it is noted that NAO values below the 2σ level have a significant impact on the Balkan Peninsula due to the activation of Mediterranean cyclones. Milošević et al. [53] report that winter precipitation in the Western Balkan countries is strongly negatively correlated with the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and shows a significant positive correlation with the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO). In a broader European context, Ref. [59] demonstrated that the NAO exerts a substantial influence on winter precipitation across the Iberian Peninsula, with cascading effects on the surrounding Mediterranean areas. Similarly, Brandimarte et al. [60] found statistically significant links between NAO variability and winter rainfall across several Mediterranean regions, emphasizing the NAO’s role as a major driver of seasonal precipitation fluctuations. Despite the weak correlations between precipitation and the NAO and MOI, climate variability over the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea appears to have affected precipitation patterns in Bulgaria. This influence can be attributed to the characteristic cyclogenesis in these regions [2].

5. Conclusions

This paper provides an updated assessment of long-term precipitation variability and extreme monthly precipitation in the high-mountain regions of Bulgaria, using data from Musala, Botev Peak, and Cherni Vrah for the period 1937–2024 (1946–2024 for the Botev Peak station). The study is constrained by restricted data availability and the very limited network of meteorological stations in Bulgaria’s high-mountain regions. The findings reveal a substantial shift in precipitation regimes over recent decades, characterized by: (1) a statistically significant decrease in annual, winter, and spring precipitation at the highest sites of Bulgaria, particularly the regions of Cherni Vrah and Musala; (2) a notable redistribution of extreme precipitation months, with cold-season wet extremes sharply declining and a relative persistence or increase in summer extremes; and (3) an intensification of dry conditions across all elevations, especially during winter and spring after 1981.

The PCI analysis shows that precipitation in the study region is characterized by a predominantly weakly uneven to uneven distribution, with individual years exhibiting high precipitation concentrations. This highlights the vulnerability to periods of drought and intense precipitation episodes driven by the dominant atmospheric circulation processes.

The contrasting precipitation regimes of the three stations highlight the complex interplay of elevation, slope exposure, and cyclonic influences in shaping high-mountain precipitation. Cherni Vrah, located directly under the influence of the Atlantic and continental air masses, exhibits the strongest drying signal. Musala, the highest peak, reveals a mix of persistent drying in the cold season but resilience of summer precipitation. In contrast, Botev Peak retains high erosive rainfall intensities in May–July, where a large share of months still fall into the “very severe” erosivity class—indicating increased potential for localized flash-flooding, slope instability, and accelerated soil loss even under an overall drying climate

Teleconnection analysis demonstrates that large-scale atmospheric circulation plays a crucial role in shaping these extremes. Positive phases of the North Atlantic Oscillation are associated with reduced wet extremes and enhanced drought risk, mainly during the cold season, while positive WeMOI phases favor the occurrence of extreme wet months, particularly in winter and spring.

In conclusion, the detected tendencies—reduced cold-season precipitation, intensified seasonality of extremes, and increased frequency of dry anomalies—highlight growing risks for water availability, hydropower generation, ecosystem functioning, and slope stability in high-altitude areas. To strengthen climate resilience, adaptive water-management strategies, improved monitoring at high elevation, and further research on circulation–extreme interactions are recommended. Future work should also integrate snow indicators and regional climate projections to better assess the implications of ongoing climate change for Bulgaria’s critical mountain “water-tower” systems.

The limitations of the present study include the relatively small number of meteorological stations located in the high mountain regions of Bulgaria, which restricts the spatial representativeness of the results. Future research should be expanded by incorporating analyses based on daily precipitation totals, which would allow for a more detailed assessment of extreme precipitation events. Nevertheless, the obtained results provide valuable insights into the genesis of the contemporary climate in the high mountain regions of Bulgaria, contribute to a better understanding of the observed climatic changes, and may serve as a foundation for future, more comprehensive studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N. and K.R.; methodology, N.N.; data processing, N.N. and S.M.; validation, N.N., M.G. and S.M.; analysis, N.N., K.R. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N. and K.R.; writing—review and editing, N.N., K.R., S.M. and M.G.; visualization, N.N. and S.M.; supervision, N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No BG-RRP-2.004-0008-C01. Part of the scientific work was carried out within the project “Transition from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought under Different Climate Types in Bulgaria,” No. 80-10-94 of 28 May 2025, funded by the University Scientific Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their time and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nikolova, N. Regional climate change: Precipitation variability in mountainous part of Bulgaria. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic. SASA 2007, 57, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mircheva, B.; Tsekov, M.; Meyer, U.; Guerova, G. Analysis of the 2014 wet extreme in Bulgaria: Anomalies of temperature, precipitation and terrestrial water storage. Hydrology 2020, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgedanova, M. Climate Change and Melting Glaciers. In The Impacts of Climate Change; Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shahgedanova, M.; Adler, C.; Gebrekirstos, A.; Grau, H.R.; Huggel, C.; Marchant, R.; Pepin, N.; Vanacker, V.; Viviroli, D.; Vuille, M. Mountain observatories: Status and prospects for enhancing and connecting a global community. Mt. Res. Dev. 2021, 41, A1–A15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründemann, G.J.; Zorzetto, E.; van de Giesen, N.; van der Ent, R.J. Historical shifts in seasonality and timing of extreme precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, N.; Bradley, R.S.; Diaz, H.F.; Baraer, M.; Caceres, E.B.; Forsythe, N.; Fowler, H.; Greenwood, G.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Liu, X.D.; et al. Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 424–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrimore, J.H.; Menne, M.J.; Gleason, B.E.; Williams, C.N.; Wuertz, D.B.; Vose, R.S.; Rennie, J. An overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network monthly mean temperature dataset, version 3. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, D19121. [Google Scholar]

- Viviroli, D.; Archer, D.R.; Buytaert, W.; Fowler, H.J.; Greenwood, G.B.; Hamlet, A.F.; Huang, Y.; Koboltschnig, G.; Litaor, M.I.; López-Moreno, J.I.; et al. Climate change and mountain water resources: Overview and recommendations for research, management and policy. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 471–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, H.J.; Lenderink, G.; Prein, A.F.; Westra, S.; Allan, R.P.; Ban, N.; Barbero, R.; Berg, P.; Blenkinsop, S.; Do, H.X.; et al. Anthropogenic intensification of short-duration rainfall extremes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalexiou, S.M.; Montanari, A. Global and regional increase of precipitation extremes under global warming. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 4901–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-C.; Ganguly, A.R. Intensity, duration, and frequency of precipitation extremes under 21st-century warming scenarios. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, D16119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocheva, L.; Malcheva, K.; Chervenkov, H. Recent Climate Assessment and Future Climate Change in Bulgaria—Brief Analysis. In Proceedings of the 23rd SGEM International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference, Albena, Bulgaria, 3–8 July 2023; Volume 23. Issue 4.1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Pan, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Q.; Ciais, P.; Penuelas, J. Global Socioeconomic Risk of Precipitation Extremes under Climate Change. Earth’s Future 2020, 8, e2019EF001331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Di Luca, A.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1513–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizbarashvili, M.; Amiranashvili, A.; Elizbarashvili, E.; Mikuchadze, G.; Khuntselia, T.; Chikhradze, N. Comparison of RegCM4.7.1 Simulation with the Station Observation Data of Georgia, 1985–2008. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, D.; Bhattarai, N.; Silwal, A.; Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, B.; Poudel, B.; Kalra, A. A Review on Climate Change Impacts on Freshwater Systems and Ecosystem Resilience. Water 2025, 17, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocheva, L.; Marinova, T.; Simeonov, P.; Gospodinov, I. Variability and trends of extreme precipitation events over Bulgaria (1961–2005). Atmos. Res. 2009, 93, 490–497. [Google Scholar]

- Dotseva, Z.; Gerdjikov, I.; Vangelov, D. Torrential Catchments from Belasitsa Mountain (SW Bulgaria)—Geological and Geomorphological Characteristics and Related Hazards. In Environmental Protection and Disaster Risks; Dobrinkova, N., Nikolov, O., Eds.; EnviroRISKs 2022; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenchev, D.; Kenderova, R.; Matev, S.; Nikolova, N.; Rachev, G.; Gera, M. Debris Flows in Kresna Gorge (Bulgaria)—Geomorphological Characteristics and Weather Conditions. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic. SASA 2021, 71, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peneva, E.; Matov, M.; Tsekov, M. Mediterranean Influence on the Climatic Regime over the Balkan Peninsula from 1901–2021. Climate 2023, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F. Climate change hot-spots. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L08707. [Google Scholar]

- González-Hidalgo, J.C.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M. Is there a precipitation decline in the Mediterranean region? An assessment based on the scientific literature. Int. J. Climatol. 2025, 45, e8918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, V.; Schneider, M.; Koleva, E.; Moisselin, J.M. Climate variability and change in Bulgaria during the 20th century. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2004, 79, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nojarov, P. Variations in precipitation amounts, atmosphere circulation, and relative humidity in high mountainous parts of Bulgaria for the period 1947–2008. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 107, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Marinova, T.; Malcheva, K.; Bocheva, L.; Trifonova, L. Climate profile of Bulgaria in the period 1988–2016 and brief climatic assessment of 2017. Bulg. J. Meteorol. Hydrol. 2017, 22, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Velichkova, T.; Kilifarska, N.; Mokreva, A. Study of the North Atlantic Oscillation influence on the climate of Europe and Balkan Peninsula. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2025, 78, 862–872. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell, J.W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 1995, 269, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topliiski, D. Climate of Bulgaria; Amstels Foundation: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2006; p. 360. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Filipov, D.; Rachev, G. Chronological variability of precipitation at the meteorological stations Mussala, Botev and Cherni Vrah. In Annual of Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Faculty of Geology and Geography, Book 2—Geography; Sofia University: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017; Volume 109, pp. 35–44. Available online: https://www.uni-sofia.bg/index.php/bul/content/download/177851/1240390/version/1/file/03_Ann_Tom_109_geography_35-44.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Hurrell, J.W.; Kushnir, Y.; Ottersen, G.; Visbeck, M. An Overview of the North Atlantic Oscillation. In The North Atlantic Oscillation: Climate Significance and Environmental Impact; Geophysical Monograph 134; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Vide, J.; Lopez-Bustins, J.-A. The Western Mediterranean Oscillation and rainfall in the Iberian Peninsula. Int. J. Climatol. 2006, 26, 1455–1475. [Google Scholar]

- De Luis, M.; Gonzalez-Hidalgo, J.C.; Brunetti, M.; Longares, L.A. Precipitation concentration changes in Spain 1946–2005. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, G.; Grifoni, D.; Magno, R.; Torrigiani, T.; Gozzini, B. Changes in temporal distribution of precipitation in a Mediterranean area (Tuscany, Italy) 1955–2013. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukic, T.; Basarin, B.; Micic, T.; Bjelajac, D.; Maris, T.; Markovic, S.B.; Pavic, D.; Gavrilov, M.B.; Mesaroš, M. Rainfall erosivity and extreme precipitation in the Netherlands. Q. J. Hung. Meteorol. Serv. 2018, 122, 409–432. [Google Scholar]

- Lukić, T.; Lukić, A.; Basarin, B.; Ponjiger, T.M.; Blagojević, D.; Mesaroš, M.; Milanović, M.; Gavrilov, M.; Pavić, D.; Zorn, M.; et al. Rainfall erosivity and extreme precipitation in the Pannonian basin. Open Geosci. 2019, 11, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, H.; Erpul, G.; Bayramin, I.; Gabriels, D. Evaluation of indices for characterizing the distribution and concentration of precipitation: A case for the region of Southeastern Anatolia Project, Turkey. J. Hydrol. 2006, 328, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěpánek, P. AnClim—Software for Time Series Analysis; Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M.; Sutherland, M.; Bouwer, L.; Cheong, S.-M.; Frölicher, T.; Jacot Des Combes, H.; Koll Roxy, M.; Losada, I.; McInnes, K.; Ratter, B.; et al. Extremes, Abrupt Changes and Managing Risk. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 589–655. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert, B.; Berg, P.; Haerter, J.O.; Jacob, D.; Moseley, C. Temporal and spatial scaling impacts on extreme precipitation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 5957–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Guidelines on the Definition and Characterization of Extreme Weather and Climate Events; WMO-No. 1310; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lukić, T.; Ponjiger, T.M.; Basarin, B.; Sakulski, D.; Gavrilov, M.; Marković, S.; Zorn, M.; Komac, B.; Milanović, M.; Petrović, A.S.; et al. Application of Angot precipitation index in the assessment of rainfall erosivity: Vojvodina Region case study (North Serbia). Acta Geogr. Slov. 2021, 61, 123–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apopei, L.; Mihaila, D. Application of the Angot (k) pluviometric index to Cotnari Weather Station in the period 1961–2020. Georeview 2022, 32, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova, V.; Nikolova, N.; Stefanova, M.; Matev, S. Annual and Seasonal Characteristics of Rainfall Erosivity in the Eastern Rhodopes (Bulgaria). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitraşcu, M.; Dragotă, C.S.; Grigorescu, I.; Dumitraşcu, C.; Vlădut, A. Key pluvial parameters in assessing rainfall erosivity in the south-west development region, Romania. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 126, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Kang, J.; Silvennoinen, A.; Teräsvirta, T. The Effect of the North Atlantic Oscillation on Monthly Precipitation in Selected European Locations: A Non-Linear Time Series Approach. Environmetrics 2025, 36, e2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, T.; Bocheva, L. (Eds.) The Changing Climate of Bulgaria—Data and Analyses; NIMH: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2023; 105p. [Google Scholar]

- Styllas, M.N.; Kaskaoutis, D.G. Relationship between Winter Orographic Precipitation with Synoptic and Large-Scale Atmospheric Circulation: The Case of Mount Olympus, Greece. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2018, 52, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feidas, H.; Noulopoulou, C.; Makrogiannis, T.; Bora-Senta, E. Trend Analysis of Precipitation Time Series in Greece and Their Relationship with Circulation Using Surface and Satellite Data: 1955–2001. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2007, 87, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, T.; Bocheva, L. (Eds.) Climate Variation and Climate Change Projection for Bulgaria; National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024; p. 50. ISBN 978-954-394-408-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmeier-Young, M.C.; Zhang, X. Human influence has intensified extreme precipitation in North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13308–13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leščešen, I.; Basarin, B.; Podraščanin, Z.; Mesaroš, M. Changes in Annual and Seasonal Extreme Precipitation over Southeastern Europe. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeer, K.; Kirchengast, G. Sensitivity of extreme precipitation to temperature: The variability of scaling factors from a regional to local perspective. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 50, 3981–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, D.; Stojsavljević, R.; Szabó, S.; Stankov, U.; Savić, S.; Mitrović, L. Spatio-temporal variability of precipitation over the Western Balkan countries and its links with the atmospheric circulation patterns. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2021, 71, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald, K.; Scheithauer, J.; Monget, J.M.; Brown, D. Characterisation of contemporary local climate change in the mountains of southwest Bulgaria. Clim. Change 2009, 95, 535–549. [Google Scholar]

- Bocheva, L.; Malcheva, K. Climatological Assessment of Extreme 24-Hour Precipitation in Bulgaria during the Period 1931–2019. In Proceedings of the 20th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2020, Albena, Bulgaria, 18–24 August 2020; Book 4.1, pp. 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Chervenkov, H.; Slavov, K. Historical climate assessment of precipitation-based ETCCDI climate indices derived from CMIP5 simulations. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2020, 73, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, D.; Dimitrov, C. Contemporary Tendencies in Snow Cover, Winter Precipitation, and Winter Air Temperatures in the Mountain Regions of Bulgaria. Climate 2025, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, M.; Damian, A.-D. Climate seasonality and its relevance for soil erosion during summer in Extra-Carpathian Moldova. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 14, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Trigo, R.M.; Pozo-Vázquez, D.; Osborn, T.J.; Castro-Díez, Y.; Gámiz-Fortis, S.; Esteban-Parra, M.J. North Atlantic oscillation influence on precipitation, river flow and water resources in the Iberian Peninsula. Int. J. Climatol. 2004, 24, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandimarte, L.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Bruni, G.; D’Odorico, P.; Montanari, A. Relation Between the North-Atlantic Oscillation and Hydroclimatic Conditions in Mediterranean Areas. Water Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.