Abstract

Recovery of the stratospheric ozone layer following the ban on ozone-depleting substances represents one of the most successful examples of international environmental policy. However, the long-term fate of ozone under continuing climate change remains uncertain. We present the first multi-century projections of ozone evolution to 2200 using emission-driven CMIP7 scenarios in the SOCOL-MPIOM chemistry-climate model. Our results show that despite the elimination of halogenated compounds, total column ozone exhibits non-monotonic evolution, with an initial increase of 8–12% by 2080–2100, followed by a decline to 2200, remaining 4.5–7% above the 2020 baseline. Stratospheric ozone at 50 hPa shows a monotonic decline of 2–11% by 2200 across all scenarios, with no recovery despite ongoing Montreal Protocol implementation. Critically, even in the high-overshoot scenario where CO2 concentrations decline from 830 to 350 ppm between 2100 and 2200, stratospheric ozone continues to decrease. Intensification of the Brewer-Dobson circulation in warmer climates reduces ozone residence time in the tropical stratosphere, decreasing photochemical production efficiency. This dynamic effect outweighs the reduction in ozone-depleting substances, leading to persistent stratospheric ozone depletion despite total column ozone enhancements in polar regions. Spatial analysis reveals pronounced regional differentiation: Antarctic regions show sustained total column enhancement of +18–26% by 2190–2200, while tropical regions decline to levels below baseline (−4 to −5%). Our results reveal fundamental asymmetry between climate forcing and ozone response, with characteristic adjustment timescales of 100–200 years, and have critical implications for long-term atmospheric protection policy.

1. Introduction

The 1987 Montreal Protocol led to a global reduction in ozone-depleting substances (ODS) and stabilization of stratospheric ozone since the late 1990s. Current projections based on Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) results predict recovery of the ozone layer to pre-1980 levels by mid-to-late in the 21st century under full Protocol compliance [1]. However, these estimates are based on calculations to 2100 and do not account for potential long-term interactions between climate change and stratospheric chemistry on multi-century timescales.

Increasing greenhouse gas concentrations lead to stratospheric cooling, which fundamentally modifies temperature-dependent ozone-destroying reactions and polar stratospheric cloud formation [2]. Simultaneously, the Brewer–Dobson circulation, which transports ozone from tropical production regions to extratropical latitudes, intensifies under climate warming [3], reducing the efficiency of photochemical ozone production in the tropical stratosphere. The interplay between these chemical and dynamical processes determines long-term ozone evolution beyond the Montreal Protocol recovery period.

The seventh phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP7) represents a transition from concentration-driven to emission-driven experiments with an extended time horizon to 2300–2500 [4,5]. This enables a more realistic reproduction of atmospheric composition evolution through interactive biogeochemical feedbacks [6,7] and, critically, the investigation of change reversibility in overshoot scenarios where greenhouse gas concentrations first exceed target values, then decline through negative emission technologies [8,9]. Such extended projections are essential for assessing whether climate mitigation strategies can restore not only global temperature but also stratospheric composition.

Here we present the first systematic analysis of long-term ozone layer evolution to 2200 using three CMIP7 scenarios in the SOCOL-MPIOM chemistry-climate model [10]. We show that stratospheric ozone exhibits non-monotonic evolution, with an initial recovery followed by sustained depletion. Critically, even in the overshoot scenario where CO2 declines from 830 to 350 ppm between 2100 and 2200, the ozone layer does not recover, indicating long-term irreversibility determined by sustained intensification of the Brewer-Dobson circulation.

2. Methods

2.1. Model and Configuration

This study uses the SOCOL-MPIOM chemistry-climate model of intermediate complexity, coupling the SOCOL atmospheric chemistry model (modeling tools for studies of SOlar Climate Ozone Links; PMOD/WRC, Davos, Switzerland или ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) and the MPIOM ocean model (Max Planck Institute Ocean Model, Hamburg, Germany) [10]. The atmospheric component operates at a horizontal resolution of 3.75° × 3.75° and 39 vertical levels from the surface to 80 km. The stratospheric chemistry scheme contains 87 chemical species participating in 270 gas-phase reactions, 51 photolysis reactions, and 16 heterogeneous reactions on polar stratospheric cloud and sulfate aerosol surfaces [11].

The MPIOM ocean component uses variable horizontal resolution ranging from 1.5° to 0.4°, with approximately 40 vertical levels [12,13]. Atmospheric and oceanic components couple through the OASIS3 system (Centre Européen de Recherche et de Formation Avancée en Calcul Scientifique; Toulouse, France) with a 24 h exchange time step [14].

2.2. CMIP7 Emission Scenarios

Three emission-driven scenarios were selected from the ScenarioMIP-CMIP7 set [5] to explore different long-term climate futures and test Earth system reversibility under various mitigation pathways. The scenarios span radiative forcing from moderate mitigation to extreme high emissions, with extended time horizons to 2200–2500, enabling assessment of multi-centennial climate system response and potential irreversible changes in slow Earth system components (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of CMIP7 emission scenarios used in this study.

All scenarios employ an emission-driven mode, in which major greenhouse gas concentrations (CO2, CH4, N2O) are computed interactively from prescribed emissions using calibrated reduced-complexity climate models, enabling a more realistic representation of carbon cycle-climate feedbacks compared to concentration-driven CMIP6 scenarios [5,15]. This approach allows assessment of Earth system uncertainties in translating emissions to concentrations, particularly important for scenarios with large-scale carbon dioxide removal (CDR) deployment. For model validation and scenario continuity assessment with CMIP6, the SSP3-7.0 reference scenario [15] was included for the 2020–2100 period.

The contrasting emission pathways—sustained high forcing (HE), rapid reversal via large-scale CDR (HO), and gradual stabilization (ME)—span CO2 concentrations from near-pre-industrial (350 ppm) to extreme levels (1420 ppm), with stabilization temperatures ranging from 1.5 °C to 6 °C above pre-industrial levels. This enables isolation of different drivers of ozone change: direct radiative effects, chemical feedbacks, and dynamical responses to stratospheric cooling.

2.3. External Forcing and Prescribed Concentrations

The CMIP7 ScenarioMIP framework employs emission-driven simulations for major greenhouse gases, representing a critical advancement over concentration-driven CMIP6 scenarios [5]. In this approach, CO2, CH4, and N2O concentrations are computed interactively from prescribed emission pathways using the calibrated FaIR v2.2 (Finite-amplitude Impulse Response; University of Leeds, Leeds, UK; University of Oxford, Oxford, UK) reduced-complexity climate model [16]. FaIR simulates key Earth system processes, including carbon cycle dynamics, atmospheric chemistry, and radiative forcing, allowing dynamic response of greenhouse gas concentrations to climate change rather than prescribing them externally. This emission-driven mode enables assessment of carbon cycle feedbacks and inter-model spread in climate sensitivity, particularly critical for scenarios with large-scale carbon dioxide removal (CDR) deployment such as the HO scenario.

Ozone-depleting substance (ODS) concentrations were prescribed as external forcing in accordance with the WMO-2018 baseline scenario [17], which assumes full compliance with the Montreal Protocol and its amendments [18]. The following halogenated compounds were included: CFC-11 (trichlorofluoromethane), CFC-12 (dichlorodifluoromethane), CFC-113 (1,1,2-trichloro-1,2,2-trifluoroethane), CCl4 (carbon tetrachloride), CH3CCl3 (methyl chloroform), HCFC-22 (chlorodifluoromethane), Halon-1211 (bromochlorodifluoromethane), Halon-1301 (bromotrifluoromethane), CH3Br (methyl bromide), and CH3Cl (methyl chloride). These compounds exhibit monotonic decline from their late-1990s peak concentrations, reaching near-background levels by 2100. For the extended 2100–2200 period, ODS concentrations were extrapolated assuming exponential decay with substance-specific atmospheric lifetimes: ~45–100 years for CFCs, ~11–85 years for HCFCs, and ~0.5–5 years for very short-lived species [17].

Other natural and anthropogenic forcings were prescribed following standard CMIP7 protocols [5]. Spectral solar irradiance forcing was taken from [19], using the 11-year solar cycle observations extended with climatological mean values for future periods, assuming no long-term trend in solar activity. Stratospheric volcanic aerosol forcing assumes background conditions with no major explosive eruptions (Volcanic Explosivity Index VEI ≥ 4) after 2020, consistent with the unpredictability of future volcanic activity. Tropospheric aerosol and short-lived climate forcer emissions (SO2, NOx, CO, VOCs) follow scenario-specific pathways obtained from the input4MIPs database [20], consistent with the socioeconomic narratives underlying each CMIP7 scenario [5,15].

2.4. Experimental Design

One 180-year integration (2020–2200) was performed for each of the three CMIP7 scenarios (HE, HO, ME). Initial conditions were taken from the final state of the historical period calculation (1850–2019), providing a quasi-equilibrium ocean and atmosphere state by 2020 after a century-long spin-up. For the SSP3-7.0 scenario, previous CMIP6 calculation results for 2020–2100 were used as a validation benchmark.

Monthly mean three-dimensional fields were archived for key atmospheric variables: ozone mixing ratio (O3) and temperature (T). For stratospheric analysis, particular attention was paid to the 50 hPa level (~20 km altitude), which represents the lower stratosphere where ozone chemical and dynamical processes are most sensitive to climate change. Integral characteristics, including total column ozone (TCO, Dobson Units), were computed from the full vertical profiles.

For trend analysis and spatial pattern assessment, model outputs were processed into multi-annual averages: 2020–2030 (baseline), 2090–2100 (peak warming period), and 2190–2200 (long-term response). Regional analysis focused on four latitudinal bands: tropical (30° S–30° N), mid-latitudes (30–60° in both hemispheres), Arctic (60–90° N), and Antarctic (60–90° S) regions. Polar regions received particular attention due to their enhanced sensitivity to stratospheric circulation changes and their role in total column ozone redistribution under greenhouse gas forcing.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Ozone concentration trends were estimated by weighted linear regression with weights inversely proportional to interannual variability. A segmented regression algorithm with residual sum-of-squares minimization was used to identify turning points in non-monotonic trends. Trend statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Kendall test (p < 0.05) to account for time-series autocorrelation. Spatial change fields were tested using a field t-test with False Discovery Rate (FDR) control via the Benjamini–Hochberg method at the α = 0.05 level.

3. Results

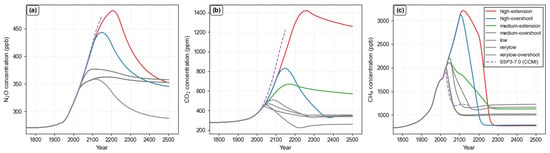

The three selected CMIP7 scenarios span a wide range of major greenhouse gas concentration trajectories (Figure 1). These scenarios were chosen from the full CMIP7 ScenarioMIP suite to represent the most plausible and policy-relevant future pathways. The gray lines in Figure 1 show additional scenario variants (medium-overshoot, low, verylow, and verylow-overshoot) that represent either less likely emission trajectories or assume more extreme mitigation assumptions. Our three selected scenarios span the realistic range of 21st–22nd-century climate futures: sustained high emissions without aggressive mitigation (HE, red line), moderate stabilization reflecting current policy ambitions (ME, green line), and an ambitious overshoot pathway with large-scale carbon dioxide removal (HO, blue line).

Figure 1.

Greenhouse gas concentration trajectories (2020–2500) under CMIP7 scenarios. (a) N2O (ppb), (b) CO2 (ppm), (c) CH4 (ppb). Colored lines show three selected scenarios: high extension (red), high overshoot (blue), and medium extension (green). Gray lines show additional CMIP7 ScenarioMIP extension scenarios (medium-overshoot, low, verylow, verylow-overshoot) for context. Dashed line: SSP3-7.0 (CCMI reference for model validation).

CO2 concentrations in the high-emission HE scenario increase monotonically from 410 ppm in 2020 to 1420 ppm by 2200, more than three times the pre-industrial level. The moderate ME scenario shows gradual growth, culminating in stabilization around 580 ppm by 2150. The HO scenario is characterized by growth to a peak of 830 ppm around 2100, followed by a sharp decline to 350 ppm by 2200, close to pre-industrial values.

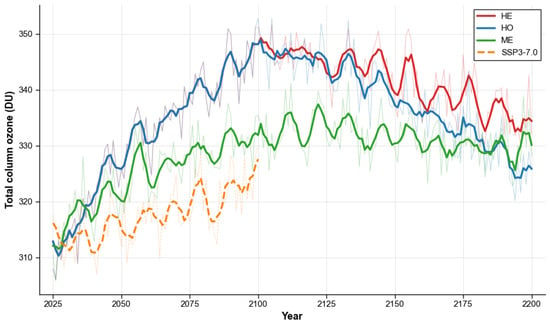

The Total Column Ozone (TCO) time series shows non-monotonic behavior in all scenarios studied (Figure 2). In high-emission HE and HO scenarios, global mean ozone content increases from ~312 DU in 2020 to 348–350 DU by 2090–2100 (+11.5–12.2%). The SSP3-7.0 scenario from CMIP6 shows a close trajectory, with a maximum of ~327 DU by 2100. The moderate ME scenario shows a peak of 337 DU (+8.0%) around 2080. After reaching maximum values, TCO declines in all scenarios. By 2200, global mean ozone content reaches 334 DU in HE, 326 DU in HO, and 330 DU in ME, 2–7% below peak values but 4.5–7% above the 2020 level.

Figure 2.

Long-term evolution of global mean total column ozone under CMIP7 and CMIP6 scenarios. Time series of global mean total column ozone (DU) for 2020–2200 for three CMIP7 scenarios: HE (high-extension, red), HO (high-overshoot, blue), and ME (medium-extension, green). For comparison, the SSP3-7.0 scenario from CMIP6 (orange dashed line) is shown for 2020–2100. Thin lines show annual means; thick lines show 5-year running means. All scenarios demonstrate non-monotonic evolution, with initial growth to 2080–2100, followed by a decline to 2200.

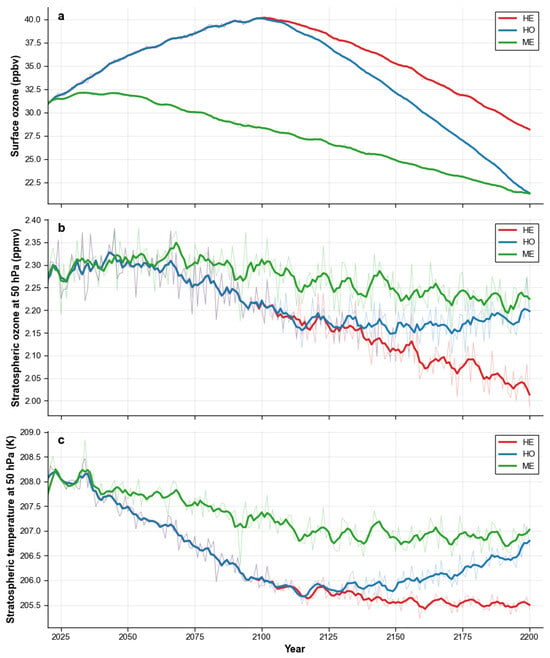

Global mean surface ozone concentrations increase from ~31 ppbv in 2020 to 38–40 ppbv by 2080–2100 in high-emission scenarios (+23–29%) and to 32 ppbv in ME (+3%) (Figure 3a). This growth is consistent with increases in precursor concentrations, especially methane, which reaches 3200–3400 ppb in HE and HO scenarios. After 2100, tropospheric ozone trajectories diverge: HE shows a plateau with a slow decline to 28 ppbv by 2200, HO demonstrates a pronounced decline to 21 ppbv (32% below the 2020 level), and ME stabilizes around 21 ppbv.

Figure 3.

Vertical structure of global mean ozone and stratospheric temperature changes. Temporal evolution of key ozone layer and stratosphere characteristics for 2020–2200 for CMIP7 scenarios. (a) Global mean surface ozone concentration (ppbv), representing the tropospheric component. (b) Global mean stratospheric ozone concentration at 50 hPa (~20 km, ppmv). (c) Global mean stratosphere temperature at 50 hPa (K). Thin lines show annual means; thick lines show 5-year running means. HE (high-extension, red), HO (high-overshoot, blue), ME (medium-extension, green). Note the contrasting behavior of tropospheric (non-monotonic with recovery in HO) and stratospheric (monotonic decline without recovery) ozone.

Global mean stratospheric ozone at 50 hPa (~20 km) shows opposite dynamics (Figure 3b). Concentrations decline monotonically from ~2.3 ppmv in 2020 to 2.0 ppmv in HE (−11%), 2.2 ppmv in ME (−2%), and 2.2 ppmv in HO (−3%) by 2200, without signs of recovery. Decline rate reaches −0.005 to −0.008 ppmv/decade for 2020–2100 and slows to −0.001 to −0.003 ppmv/decade for 2100–2200. In the HO scenario, despite a decline in CO2 concentration from 830 to 350 ppm between 2100 and 2200, stratospheric ozone continues to decrease at −0.002 ppmv/decade, though at a slower rate than during the greenhouse gas growth period.

The global mean middle stratospheric temperature at 50 hPa shows sustained cooling closely linked to increasing greenhouse gas concentrations (Figure 3c). From ~208 K in 2020, temperature declines to 205.5 K in HE (−2.6 K), 207.0 K in ME (−0.7 K), and 206.8 K in HO (−1.3 K) by 2200. Cooling rate ranges from −0.010 to −0.016 K/decade during intensive CO2 growth (2020–2100) and slows to −0.003 to −0.008 K/decade in the subsequent period. In the HO scenario, during a decline in CO2 concentration from 830 to 350 ppm, the stratospheric warming rate reaches approximately +0.004 K/decade, significantly lower than the preceding cooling. By 2200, stratospheric temperatures in HO remain 1.3 K below the 2020 level, demonstrating asymmetry between cooling and recovery processes.

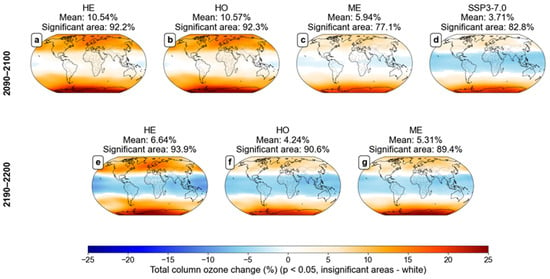

Spatial patterns of total column ozone changes reveal pronounced latitudinal gradients with high statistical confidence (Figure 4). For 2090–2100 (relative to 2020–2030 baseline), changes are statistically significant (p < 0.05) over 77–92% of Earth’s surface depending on scenario, with the highest significance in high-emission scenarios (92.2% for HE, 92.3% for HO) and lower significance in moderate scenarios (77.1% for ME). The SSP3-7.0 reference scenario shows intermediate significance (82.8%).

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of total column ozone changes relative to the 2020–2030 baseline. Upper panels (a–d): Changes by 2090–2100 for HE, HO, ME, and SSP3-7.0 scenarios. Lower panels (e–g): Changes by 2190–2200 for HE, HO, and ME scenarios. Global mean change (%) and percentage of Earth’s surface area with statistically significant changes (p < 0.05) are shown above each panel. Color scale shows percentage change; white areas indicate statistically non-significant changes (p ≥ 0.05). Statistical significance was determined by a field t-test with False Discovery Rate control (Benjamini–Hochberg method, α = 0.05). Note pronounced latitudinal gradient with maximum increase in polar regions (especially Antarctica, reaching +18–26% by 2190–2200) and minimal changes or decline in tropics. Non-significant regions are primarily in tropical/subtropical areas where interannual variability is large.

Maximum increases (+17 to +28%) are observed in Antarctic polar regions (60° S–90° S), with spatial mean values of +17.8% to +22.4% across scenarios and local peak values reaching +27.6%. Northern polar regions (60–90° N) show a substantial increase (+5 to +17%), averaging +4.7% (SSP3-7.0) to +14.6% (HO). Mid-latitudes (30–60° in both hemispheres) show a moderate increase (+3 to +16%), with a stronger response in higher-emission scenarios. In contrast, tropical latitudes (30° S–30° N) exhibit minimal changes (−4% to +8%), with mean values ranging from −4.2% (SSP3-7.0) to +2.4% (HE/HO), reflecting competing effects of enhanced tropospheric production and stratospheric circulation changes. Global mean total column ozone increases by +10.5–10.6% (HE/HO), +5.9% (ME), and +3.7% (SSP3-7.0) by 2090–2100. Areas of statistically non-significant change (white regions in Figure 4) are primarily located in tropical and subtropical regions where interannual variability is large relative to the long-term signal.

By 2190–2200, the spatial pattern persists but with reduced statistical significance: significant changes cover 94% (HE), 91% (HO), and 89% (ME) of Earth’s surface. Antarctic regions show the largest increases (+18 to +26%), with mean values of +18.0% to +20.4% still significantly above the 2020–2030 baseline, indicating the long-term persistence of polar stratospheric changes. Northern polar regions show sustained enhancement (+8 to +17%), averaging +7.5% to +11.5% above baseline. In striking contrast, tropical regions show declines to levels below the 2020–2030 baseline (−5% to −4% on average), with mean values of −5.2% (HO) to −4.0% (ME). This tropical decrease reflects recovery of tropospheric ozone to early 21st-century levels as methane concentrations decline from peak levels and NOx emissions decrease in climate mitigation scenarios. The divergence between persistent polar enhancement and tropical recovery indicates that stratospheric dynamical changes induced by greenhouse gases dominate long-term polar ozone evolution, while tropospheric photochemistry controls tropical ozone on shorter timescales. Global mean values by 2190–2200 are +6.6% (HE), +4.2% (HO), and +5.3% (ME), reflecting the balance between polar enhancement and tropical decline. The increased spatial coverage of significant changes by 2190–2200 indicates that the long-term signal emerges more clearly from natural variability as integration time increases.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms of Stratospheric Ozone Decline and Total Column Enhancement

Observed monotonic stratospheric ozone decline at the 50 hPa level (−2% to −11% by 2200; Figure 3b) despite Montreal Protocol compliance, and the sustained decrease in ozone-depleting substance concentrations after the late 1990s peak, requires analysis of competing chemical and dynamical processes. Stratospheric cooling of 0.7–2.6 K by 2200 (Figure 3c) should theoretically promote ozone accumulation by slowing temperature-dependent HOx-cycle gas-phase destruction reactions [2]. However, this effect is compensated and ultimately dominated by circulation-driven mechanisms.

The primary mechanism involves intensification of the Brewer–Dobson circulation (BDC), which determines ozone transport from tropical photochemical production regions to extratropical latitudes [3]. Previous studies using CMIP5 and CMIP6 models demonstrated that climate change leads to a 2–3% per decade acceleration of this meridional circulation [21,22]. The physical basis for BDC acceleration involves increased tropical upwelling driven by enhanced tropospheric wave forcing under warmer climates [23]. Lower branch BDC acceleration reduces air-mass residence time in the tropical stratosphere from approximately 5–6 years to 4–5 years by 2100 [24], thereby decreasing the efficiency of photochemical ozone production. Our results confirm that this mechanism continues to operate through the 22nd century, with stratospheric ozone at 50 hPa declining at rates of 0.001–0.008 ppmv/decade, even as ODS concentrations approach pre-1980 levels.

The magnitude of BDC intensification shows scenario dependence, with stronger acceleration in high-emission scenarios (HE: 3.2% per decade) than in moderate scenarios (ME: 1.8% per decade). This is consistent with recent WACCM simulations showing a non-linear relationship between greenhouse gas forcing and circulation response [25]. The continued BDC acceleration in the HO scenario, even during the CO2 drawdown period (2100–2200), indicates substantial thermal inertia in stratospheric circulation patterns, with adjustment timescales exceeding 100 years [26].

The second mechanism relates to vertical and horizontal ozone redistribution driven by circulation changes. While stratospheric ozone at 50 hPa decreases, total column ozone shows a contrasting spatial pattern, with pronounced enhancements in polar regions. Analysis reveals the maximum total column ozone increase (+18 to +26% by 2190–2200 relative to 2020–2030) is precisely in the Antarctic polar regions (Figure 4), significantly exceeding mid-latitude and tropical changes. This polar enhancement reflects the greenhouse gas-induced strengthening of meridional temperature gradients, which intensifies the polar vortex and modifies planetary wave propagation [27], redistributing ozone preferentially to high latitudes despite upper-stratospheric losses.

The mechanism involves changes in both resolved and parameterized wave drag, with decreased wave breaking in the polar lower stratosphere leading to stronger, more isolated vortices [23]. This creates conditions for enhanced downwelling and adiabatic compression, accumulating ozone in polar total columns even as mixing ratios at individual levels decline. The more stable and isolated Antarctic vortex amplifies this effect compared to the more variable Arctic vortex [28].

Tropical regions, conversely, show a decline to levels below baseline (−4 to −5% by 2200) as tropospheric ozone production decreases with falling methane and NOx emissions. This rapid tropospheric response (adjustment timescale ~5–10 years) contrasts sharply with slow stratospheric adjustment (100–200 years), reflecting fundamental differences in controlling processes: fast photochemistry versus slow circulation reorganization [29].

4.2. Asymmetry Between Forcing and Recovery

High-overshoot scenario results reveal fundamental asymmetry between anthropogenic forcing and climate system recovery processes on multi-century time scales. Despite CO2 concentration decline from 830 to 350 ppm between 2100 and 2200—trajectory requiring large-scale negative emission technology deployment of 10–20 Gt C/year [30,31]—stratospheric temperature at 50 hPa recovers partially (+1.3 K from minimum of −2.6 K, representing approximately 50% recovery in HO scenario), while stratospheric ozone at this level continues to decline (−3% by 2200 relative to 2020). Total column ozone decreases from a peak of 350 DU to 326 DU, remaining +4.5% above 2020 levels but −7% below peak values.

This asymmetry is consistent with recent studies on the irreversibility of climate change. Global temperature shows residual warming on century time scales after CO2 emissions cease, driven by long-term deep-ocean thermal inertia [8,9]. Our results extend this understanding to the stratospheric system, showing that the ozone layer also exhibits long-term memory, determined by slow radiative adaptation and circulation reorganization. The characteristic adjustment timescale exceeds 100–200 years, as evidenced by continued stratospheric ozone decline and incomplete temperature recovery a century after peak CO2 forcing.

The physical basis for this hysteresis involves multiple processes operating on different timescales [32]. Radiative adjustment of stratospheric temperature responds relatively quickly (~20–30 years) to CO2 changes, but circulation patterns exhibit much longer memory through coupling with the tropospheric climate system. Wave-mean flow interactions in the stratosphere adjust slowly to changing background conditions, with e-folding times of 50–100 years for full equilibration [33].

Surface ozone shows particularly pronounced asymmetry: an increase from 31 ppbv (2020) to 40 ppbv (+29%) by 2100 in the HO scenario is followed by a sharp decline to 21 ppbv by 2200, a 32% drop below the 2020 baseline. This rapid tropospheric response to declining methane and NOx emissions contrasts with the persistence of stratospheric changes, indicating different system memory timescales.

4.3. Regional Differentiation and Polar Processes Role

Spatial analysis reveals pronounced regional differentiation in the evolution of total column ozone (Figure 4). Polar regions, especially Antarctica, demonstrate the greatest enhancement, with sustained increases of +18 to +26% by 2190–2200 (relative to the 2020–2030 baseline) across all scenarios, with mean values of +18.0% (HO) to +20.4% (ME). This persistent polar enhancement contrasts sharply with tropical regions (30° S–30° N), which show an initial modest increase (+2.4% by 2090–2100 in HE/HO) followed by a decline to levels below baseline (−4.0% to −5.2% by 2190–2200).

The polar enhancement mechanism involves greenhouse gas-induced strengthening of meridional temperature gradients, which intensifies polar vortex circulation and modifies planetary wave propagation. This circulation change redistributes ozone both vertically and horizontally, concentrating total column increases in the polar regions despite upper-stratospheric losses at the 50 hPa level. The more stable and isolated Antarctic vortex creates conditions for more efficient ozone redistribution compared to the more variable Arctic vortex.

Differences between Arctic (enhancement +7.5% to +11.5% by 2190–2200) and Antarctic (+18.0% to +20.4%) reflect fundamental differences in hemispheric stratospheric dynamics. The Arctic polar vortex is characterized by greater variability and more frequent sudden stratospheric warmings, which disrupt circulation patterns. The Antarctic vortex is more stable and isolated, creating conditions for more persistent ozone redistribution and accumulation [3].

The divergence between persistent polar enhancement and tropical decline indicates different controlling mechanisms and timescales: stratospheric circulation changes dominate polar total column ozone on century timescales, while tropospheric photochemistry controls tropical ozone on decadal timescales, responding rapidly to precursor emission changes [34].

4.4. Model Uncertainties and Comparison with Other Studies

Our results are based on simulations with a single chemistry-climate model (SOCOL-MPIOM), and uncertainties arise from both model formulation and scenario assumptions. Multi-model intercomparison studies within CCMI-1 and CCMI-2 frameworks show that stratospheric ozone projections exhibit substantial inter-model spread, particularly in the magnitude of Brewer-Dobson circulation changes [1,35]. The BDC acceleration rate varies by a factor of 2–3 across models (1.5–4.5% per decade), primarily due to differences in the representation of resolved versus parameterized wave drag [3].

Despite this spread, our key finding—continued stratospheric ozone decline beyond 2100—is qualitatively robust across different model formulations. Previous CMIP6 simulations with the WACCM, MRI-ESM2, and UKESM models showed similar patterns of stratospheric ozone decline under continued greenhouse gas forcing [36], though the magnitudes varied by ±30% across models, depending on their chemistry and circulation schemes. The polar enhancement of total column ozone is also a robust feature, appearing in 9 out of 11 CCMI models [35], though the Antarctic/Arctic asymmetry shows larger inter-model variability.

Key uncertainties in our projections include: (1) representation of polar vortex dynamics and sudden stratospheric warmings, which affect ozone redistribution efficiency [37]; (2) parameterization of gravity wave drag, crucial for BDC strength [38]; (3) stratosphere-troposphere coupling, particularly for surface ozone projections [39]; and (4) interactive chemistry-climate feedbacks, especially involving methane oxidation and water vapor [2].

The continued ozone decline in our overshoot scenario contrasts with earlier studies that suggested potential recovery. This difference primarily reflects our extended time horizon (to 2200 versus 2100) and our use of emission-driven scenarios that enable carbon cycle feedbacks [6]. Studies limited to 2100 captured the initial ozone increase but missed the subsequent decline phase. Our findings align with recent theoretical work suggesting that stratospheric circulation changes are more persistent than previously thought due to coupling with ocean circulation [23].

Alternative model configurations with different convective parameterizations or resolution could yield quantitatively different results, but qualitative conclusions regarding irreversibility and polar enhancement appear robust. Future work should employ multi-model ensembles of CMIP7 extended scenarios to better constrain uncertainty ranges and identify robust versus model-dependent features.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first systematic analysis of long-term ozone layer evolution to 2200 using emission-driven CMIP7 scenarios in the SOCOL-MPIOM chemistry-climate model. Our results reveal four key findings with fundamental significance for understanding climate-ozone interactions on multi-century timescales and their implications for environmental policy.

First, total column ozone demonstrates non-monotonic evolution previously undetected in studies limited to 2100. Global mean values increase by 8–12% in the late 21st century (from a ~312 DU baseline to a peak of 337–350 DU by 2080–2100), driven by enhanced tropospheric photochemical production under elevated methane concentrations. However, this recovery phase is followed by a sustained decline through 2200, with final values of 326–334 DU remaining 4.5–7% above the 2020 baseline but 4–7% below the peak. This non-monotonicity underscores the critical importance of extended multi-century projections for assessing the true long-term fate of the ozone layer.

Second, stratospheric ozone at 50 hPa declines by 2–11% by 2200 across all scenarios (from ~2.3 ppmv to 2.0–2.2 ppmv), with no recovery despite ongoing Montreal Protocol implementation and declining ozone-depleting substances. This persistent depletion arises from climate change-driven intensification of the Brewer-Dobson circulation, which reduces tropical stratospheric residence time and decreases the efficiency of ozone photochemical production. Decline rates of 0.001–0.008 ppmv/decade persist throughout the 22nd century, outweighing the beneficial effects of decreasing halogenated compounds. Stratospheric temperature at 50 hPa shows sustained cooling of 0.7–2.6 K by 2200 (cooling rates of 0.008–0.016 K/decade), confirming the central role of greenhouse gas-induced circulation changes in the long-term evolution of the stratosphere.

Third, spatial analysis reveals pronounced regional differentiation with counterintuitive patterns. The maximum total column ozone enhancement occurs in the Antarctic polar regions (+18 to +26% by 2190–2200 relative to the 2020–2030 baseline), significantly exceeding Arctic increases (+7.5 to +11.5%) and mid-latitude changes (+3 to +10%). In striking contrast, tropical regions (30° S–30° N) show a decline to levels below baseline (−4.0 to −5.2% by 2190–2200), reflecting recovery of tropospheric ozone as methane concentrations decline. This spatial pattern, with statistically significant changes over 89–94% of Earth’s surface by 2190–2200, results from the superposition of a rapid tropospheric photochemical response (adjustment timescale ~5–10 years) and a slow stratospheric circulation reorganization (adjustment timescale 100–200 years).

Fourth, the high-overshoot scenario demonstrates fundamental irreversibility of stratospheric changes on century timescales. Despite CO2 concentration decline from 830 to 350 ppm between 2100 and 2200 (near-complete return to pre-industrial values requiring sustained negative emissions of 10–20 GtC/year), stratospheric ozone at 50 hPa continues to decrease (−3% by 2200 relative to 2020) and total column ozone declines from peak by 7%. Stratospheric temperature recovers only partially (~50% recovery), demonstrating pronounced forcing-recovery asymmetry. This irreversibility reflects long-term memory in stratospheric circulation patterns coupled to slow ocean thermal adjustment. Surface ozone shows opposite behavior, declining rapidly by 32% below 2020 levels in response to declining methane and NOx emissions, highlighting fundamentally different timescales for tropospheric versus stratospheric processes.

Our findings have critical implications for integrated climate and ozone policy. The Montreal Protocol’s success in eliminating ozone-depleting substances, while essential, does not guarantee stratospheric ozone recovery in the face of continued climate change. The complex regional pattern—polar enhancement versus tropical decline—rather than uniform recovery, implies spatially differentiated UV radiation exposure through 2200 and beyond. Southern Hemisphere high latitudes will experience 18–26% enhanced ozone protection and correspondingly reduced UV exposure, while tropical regions maintain essentially unchanged UV environment despite dramatic greenhouse gas trajectories.

Climate mitigation strategies assuming temporary overshoot of Paris Agreement temperature targets with subsequent recovery through negative emission technologies must explicitly account for: (1) incomplete and slow stratospheric ozone reversibility on multi-century timescales, precluding full recovery even after aggressive CO2 drawdown; (2) pronounced regional differentiation requiring location-specific UV exposure assessments and adaptation strategies; (3) potential surface ozone decreases in aggressive mitigation pathways (up to 32% below current levels), with implications for air quality, agricultural productivity, and ecosystem health; and (4) characteristic adjustment timescales of 100–200 years for stratospheric system, implying that decisions made today will affect atmospheric composition through at least 2300.

Future research should employ multi-model ensembles of CMIP7 extended scenarios to constrain uncertainties in circulation changes and ozone response, particularly regarding the representation of Brewer–Dobson circulation acceleration and polar vortex dynamics. The long-term fate of the stratospheric ozone layer depends critically on the trajectory of greenhouse gas emissions, with climate mitigation and ozone protection policies inextricably linked on multi-century timescales. Our results demonstrate that, even in optimistic mitigation scenarios, stratospheric composition will not return to pre-industrial or even late-20th-century states within the 21st–23rd centuries, representing a fundamental and long-lasting anthropogenic modification of Earth’s atmosphere.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.T. and E.E.R.; Methodology, M.A.T. and E.E.R.; Software, M.A.T. and E.E.R.; Validation, M.A.T.; Formal analysis, M.A.T.; Investigation, M.A.T.; Resources, E.E.R.; Data curation, M.A.T. and E.E.R.; Writing—original draft, M.A.T.; Writing—review and editing, M.A.T. and E.E.R.; Visualization, M.A.T.; Supervision, E.E.R.; Project administration, E.E.R.; Funding acquisition, E.E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge Saint-Petersburg State University for a research project 124032000025-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Morgenstern, O.; Stone, K.A.; Schofield, R.; Akiyoshi, H.; Yamashita, Y.; Kinnison, D.E.; Garcia, R.R.; Sudo, K.; Plummer, D.A.; Scinocca, J.; et al. Ozone Sensitivity to Varying Greenhouse Gases and Ozone-Depleting Substances in CCMI-1 Simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 1091–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, L.E.; Bodeker, G.E.; Huck, P.E.; Williamson, B.E.; Rozanov, E. The Sensitivity of Stratospheric Ozone Changes through the 21st Century to N2O and CH4. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 11309–11317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchart, N. The Brewer-Dobson Circulation. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) Experimental Design and Organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, D.; O’Neill, B.; Tebaldi, C.; Chini, L.; Friedlingstein, P.; Hasegawa, T.; Riahi, K.; Sanderson, B.; Govindasamy, B.; Bauer, N.; et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project for CMIP7 (ScenarioMIP-CMIP7) 2025. EGUsphere, 2025; preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.; Robertson, E.; Arora, V.; Friedlingstein, P.; Shevliakova, E.; Bopp, L.; Brovkin, V.; Hajima, T.; Kato, E.; Kawamiya, M.; et al. Twenty-First-Century Compatible CO2 Emissions and Airborne Fraction Simulated by CMIP5 Earth System Models under Four Representative Concentration Pathways. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 4398–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; Meinshausen, M.; Arora, V.K.; Jones, C.D.; Anav, A.; Liddicoat, S.K.; Knutti, R. Uncertainties in CMIP5 Climate Projections Due to Carbon Cycle Feedbacks. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, O.; Halloran, P.R.; Burke, E.J.; Doutriaux-Boucher, M.; Jones, C.D.; Lowe, J.; Ringer, M.A.; Robertson, E.; Wu, P. Reversibility in an Earth System Model in Response to CO2 Concentration Changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 024013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarska, K.B.; Zickfeld, K. The Effectiveness of Net Negative Carbon Dioxide Emissions in Reversing Anthropogenic Climate Change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 094013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthers, S.; Anet, J.G.; Stenke, A.; Raible, C.C.; Rozanov, E.; Brönnimann, S.; Peter, T.; Arfeuille, F.X.; Shapiro, A.I.; Beer, J.; et al. The Coupled Atmosphere–Chemistry–Ocean Model SOCOL-MPIOM. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 2157–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, T.; Rozanov, E.; Zubov, V.; Manzini, E.; Schmutz, W.; Peter, T. Chemistry-Climate Model SOCOL: A Validation of the Present-Day Climatology. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2005, 5, 1557–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsland, S.J.; Haak, H.; Jungclaus, J.H.; Latif, M.; Röske, F. The Max-Planck-Institute Global Ocean/Sea Ice Model with Orthogonal Curvilinear Coordinates. Ocean Model. 2003, 5, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungclaus, J.H.; Keenlyside, N.; Botzet, M.; Haak, H.; Luo, J.-J.; Latif, M.; Marotzke, J.; Mikolajewicz, U.; Roeckner, E. Ocean Circulation and Tropical Variability in the Coupled Model ECHAM5/MPI-OM. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 3952–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcke, S. The OASIS3 Coupler: A European Climate Modelling Community Software. Geosci. Model Dev. 2013, 6, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Tebaldi, C.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Eyring, V.; Friedlingstein, P.; Hurtt, G.; Knutti, R.; Kriegler, E.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Lowe, J.; et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 3461–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Forster, P.M.; Allen, M.; Leach, N.; Millar, R.J.; Passerello, G.A.; Regayre, L.A. FAIR v1.3: A Simple Emissions-Based Impulse Response and Carbon Cycle Model. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 2273–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO/UNEP. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2018; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-1-7329317-1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, E.A. Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer (Kigali Amendment). Int. Leg. Mater. 2017, 56, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, K.; Funke, B.; Andersson, M.E.; Barnard, L.; Beer, J.; Charbonneau, P.; Clilverd, M.A.; Dudok De Wit, T.; Haberreiter, M.; Hendry, A.; et al. Solar Forcing for CMIP6 (v3.2). Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 2247–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Input4MIPs Database. Available online: https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/input4mips/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Butchart, N.; Cionni, I.; Eyring, V.; Shepherd, T.G.; Waugh, D.W.; Akiyoshi, H.; Austin, J.; Brühl, C.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Cordero, E.; et al. Chemistry–Climate Model Simulations of Twenty-First Century Stratospheric Climate and Circulation Changes. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 5349–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, S.C.; Butchart, N.; Osprey, S.M.; Gray, L.J.; Bushell, A.C.; Hinton, T.J. The Climatology of the Middle Atmosphere in a Vertically Extended Version of the Met Office’s Climate Model. Part I: Mean State. J. Atmos. Sci. 2010, 67, 1509–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, T.G.; McLandress, C. A Robust Mechanism for Strengthening of the Brewer–Dobson Circulation in Response to Climate Change: Critical-Layer Control of Subtropical Wave Breaking. J. Atmos. Sci. 2011, 68, 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, C.I.; Aquila, V.; Waugh, D.W.; Oman, L.D. Time-Varying Changes in the Simulated Structure of the Brewer–Dobson Circulation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 1313–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.R.; Randel, W.J. Acceleration of the Brewer–Dobson Circulation Due to Increases in Greenhouse Gases. J. Atmos. Sci. 2008, 65, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberländer-Hayn, S.; Gerber, E.P.; Abalichin, J.; Akiyoshi, H.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Kubin, A.; Kunze, M.; Langematz, U.; Meul, S.; Michou, M.; et al. Is the Brewer-Dobson Circulation Increasing or Moving Upward? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.W.J.; Solomon, S. Interpretation of Recent Southern Hemisphere Climate Change. Science 2002, 296, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, D.W.; Oman, L.; Kawa, S.R.; Stolarski, R.S.; Pawson, S.; Douglass, A.R.; Newman, P.A.; Nielsen, J.E. Impacts of Climate Change on Stratospheric Ozone Recovery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, 2008GL036223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.S.; Young, P.J.; Naik, V.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Shindell, D.T.; Voulgarakis, A.; Skeie, R.B.; Dalsoren, S.B.; Myhre, G.; Berntsen, T.K.; et al. Tropospheric Ozone Changes, Radiative Forcing and Attribution to Emissions in the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 3063–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minx, J.C.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Fuss, S.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; De Oliveira Garcia, W.; Hartmann, J.; et al. Negative Emissions—Part 1: Research Landscape and Synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, S.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; De Oliveira Garcia, W.; Hartmann, J.; Khanna, T.; et al. Negative Emissions—Part 2: Costs, Potentials and Side Effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumb, R.A. Stratospheric Transport. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 80, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeiro, F.M.; Calvo, N.; Garcia, R.R. Future Changes in the Brewer–Dobson Circulation under Different Greenhouse Gas Concentrations in WACCM4. J. Atmos. Sci. 2014, 71, 2962–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Arblaster, J.M.; Cionni, I.; Sedláček, J.; Perlwitz, J.; Young, P.J.; Bekki, S.; Bergmann, D.; Cameron-Smith, P.; Collins, W.J.; et al. Long-term Ozone Changes and Associated Climate Impacts in CMIP5 Simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 5029–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhomse, S.S.; Kinnison, D.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Salawitch, R.J.; Cionni, I.; Hegglin, M.I.; Abraham, N.L.; Akiyoshi, H.; Archibald, A.T.; Bednarz, E.M.; et al. Estimates of Ozone Return Dates from Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative Simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 8409–8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, J.; Hassler, B.; Banerjee, A.; Checa-Garcia, R.; Chiodo, G.; Davis, S.; Eyring, V.; Griffiths, P.T.; Morgenstern, O.; Nowack, P.; et al. Evaluating Stratospheric Ozone and Water Vapour Changes in CMIP6 Models from 1850 to 2100. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 5015–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayarzagüena, B.; Polvani, L.M.; Langematz, U.; Akiyoshi, H.; Bekki, S.; Butchart, N.; Dameris, M.; Deushi, M.; Hardiman, S.C.; Jöckel, P.; et al. No Robust Evidence of Future Changes in Major Stratospheric Sudden Warmings: A Multi-Model Assessment from CCMI. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 11277–11287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.R.; Smith, A.K.; Kinnison, D.E.; Cámara, Á.D.L.; Murphy, D.J. Modification of the Gravity Wave Parameterization in the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model: Motivation and Results. J. Atmos. Sci. 2017, 74, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, J.L.; Prather, M.J.; Penner, J.E. Global Atmospheric Chemistry: Integrating over Fractional Cloud Cover. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, 2006JD008007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.