Abstract

In order to solve the problems of high volatility and insufficient absorption effect when using chemical by-product washing oil to treat benzene-containing waste gas, this study innovatively proposed a composite solvent screening method based on the solvation free energy (ΔGsol), and reasonably predicted the absorption performance of 26 solvents for benzene. Through theoretical calculation and experimental verification, tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (TGDE) was finally determined to be the optimal composite component of washing oil. The absorption efficiency of the composite solvent reached 96.2%, and the regeneration efficiency was stable after 12 cycles with a mass loss of only 2.4%. Quantum computing simulation revealed that the dispersion force is dominant between benzene and the solvent, and TGDE enhances the electrostatic interaction through weak hydrogen bonds. The synergistic effect of the two improves the absorption performance. This study provides theoretical and technical support for the development of efficient and renewable benzene waste gas recovery solvent systems.

1. Introduction

Benzene is a typical volatile organic compound (VOC) [1], and has been classified as a Group 1 carcinogen, drawing global attention due to its environmental and health impacts [2]. As a fundamental chemical in the petrochemical industry, benzene serves as a key precursor for derivatives such as styrene, cumene, cyclohexane, and aniline [3], and is widely used in plastics, rubber, and agrochemicals [4]. However, its high volatility leads to easy release into the environment during production, transportation, and fuel combustion [5], resulting in severe contamination of air, groundwater, and soil ecosystems [6]. Consequently, various countries have established regulations to limit excessive industrial emissions of VOCs [7].

Current commonly used technologies for benzene waste gas treatment include membrane separation [8], condensation, adsorption [9], and absorption [10,11]. Among these, solvent absorption is widely employed industrially due to its mature technology, high processing capacity, and efficient removal of aromatic hydrocarbons [12]. Solvent selection is a critical factor determining the economic feasibility and efficiency of absorption. Traditional solvents such as washing oil (a high-boiling-point hydrocarbon mixture) are mainstream choices in the coke chemical industry because they have a strong affinity for benzene and are usually recovered from rich wash oil by slightly overpressure distillation. In rare cases, vacuum distillation is used for regeneration [13,14]. Studies by K. BAY et al. [15] reported an infinite activity coefficient of 0.628 for biodiesels in absorbing the benzene series, indicating good absorption performance. A. Erto et al. [16] investigated four different copolymers for benzene removal and found that Pluronic P123 exhibited favorable Henry’s constants (59.6 atm at 293 K and 1178.1 atm at 363 K) during absorption/desorption. However, washing oil has significant limitations in practical applications. First, its high volatility leads to considerable loss: Vecer et al. [17] reported a volatility loss of 3.9 wt.% during benzene absorption, increasing solvent replenishment costs and posing secondary pollution risks. Second, the absorption efficiency of washing oil is constrained by its reliance solely on non-polar interactions, making it difficult to meet increasingly stringent environmental regulations [18]. Moreover, its regeneration performance declines with repeated cycles, undermining long-term economic viability. These drawbacks have motivated the exploration of more efficient, low-volatility solvent systems.

In recent years, novel blended absorbents have been extensively studied for treating benzene series compounds [19,20]. For instance, Zhang et al. [21] demonstrated that an ionic liquid (IL)-based solvent ([HMIM][Cl]–PEG200) achieved a benzene absorption efficiency of 87.15% from mixed gases, with quantum chemical calculations further revealing hydrogen bonding interactions with benzene molecules. Liu et al. [22] combined experiments and molecular dynamics simulations to show that supramolecular deep eutectic solvents (DES) enhance benzene absorption capacity through π–π stacking interactions. These studies indicate that compounding different components can enhance absorption via synergistic effects. However, the high synthesis costs of ILs hinder large-scale application [23,24]. Moreover, DESs and ILs often have poorer gas–liquid mass transfer efficiency and greater viscosities than traditional organic solvents. Inspired by compounding strategies, incorporating efficient, low-volatility components into washing oil systems could balance absorption performance and economic efficiency. Nevertheless, rapidly identifying suitable compound components from numerous candidates remains challenging. Traditional screening methods rely heavily on extensive experiments, which are time-consuming and costly. While some progress has been made in rapidly predicting solvent properties via computational simulations [25,26], no study has yet applied this approach to optimize washing oil compound systems.

To address this, this study proposes an innovative washing oil compounding strategy, employing computational solvation free energy (ΔGsol) calculations for the first time to screen highly efficient, low-volatility components from a broad range of candidate solvents. Dynamic absorption and cyclic regeneration experiments were conducted to validate the absorption performance of the compound system with washing oil. Furthermore, quantum chemical calculations were employed to elucidate the interaction mechanisms among the compound component, washing oil, and benzene molecules. The aim is to establish a combined theoretical and experimental strategy for solvent screening and optimization, providing theoretical guidance for the design of high-efficiency absorption systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The reagents used in the experiment are as follows: the washing oil solvent consists of biphenyl (purity ≥ 99%), naphthalene (purity ≥ 98%), 1-methylnaphthalene (purity ≥ 98%), 2-methylnaphthalene (purity ≥ 97%), dimethylnaphthalene (purity ≥ 98%), fluorene (purity ≥ 99%), dibenzofuran (purity ≥ 98%), and acenaphthylene (purity ≥ 97%). The specific content of each component is shown in Table S1. The 26 other solvents selected for the experiment are shown in Table S2. These solvents were screened based on their diverse functional groups, high boiling points to minimize volatility loss, and commercial availability for potential industrial application. All the above reagents were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

It is important to note that a model washing oil composed of eight representative components was employed in this study, rather than real industrial washing oil. This simplification was necessary to facilitate the quantum chemical calculations based on defined molecular structures and to ensure experimental reproducibility. However, this model excludes heavy polymer components typically present in industrial oil, which implies that the actual thermal stability in industrial applications may be higher than that observed in this study.

2.2. Determination of Partition Coefficient

The partition coefficient (K) of benzene in different solvents was determined using the standard static method [27]. The headspace vials used in this study were equipped with polypropylene caps and polytetrafluoroethylene gaskets to ensure airtightness. Before testing, 8–10 g of solvent was added to the vial, followed by the injection of 10 μL of liquid benzene using a microsyringe. The vial was placed in a constant-temperature oven and maintained at 303 K for 24 h to allow equilibrium. The benzene concentration in the gas phase was subsequently measured using gas chromatography (GC2010 Plus, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). The partition coefficient K was calculated according to the following formula [28]:

where K is the distribution coefficient, dimensionless; and CL and CG are the concentrations of benzene in the liquid and gas phases, respectively, in mg/m3.

2.3. Absorption and Desorption Experiments

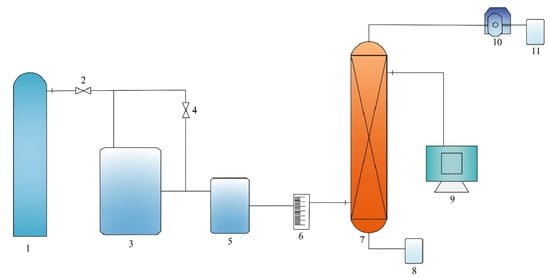

A packed column was employed to simulate real absorption conditions. A packed column was employed to simulate real absorption conditions using θ ring packing (4 × 4 mm) as the stationary phase. The column had a total height of 1 m, an internal diameter of 25 mm, and an effective packing height of 75 cm. The absorption temperature was maintained at 303 K. During operation, The waste gas flow rate was set at 4 L/min, with a benzene concentration of 10,000 mg/m3. The liquid-to-gas ratio throughout the absorption process was maintained at 3.0 L/m3. The detailed absorption process is illustrated in Figure 1. The absorption efficiency of the solvent system was calculated by measuring the benzene concentrations at the inlet and outlet of the packed column, using the following formula:

where c1 and c2 represent the concentrations of benzene in the gas phase (in mg/m3) at the outlet and inlet, respectively. The rich solution after absorption was regenerated using a rotary evaporator under conditions of 0.1 atm and 368 K for 1 h.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the absorption process: 1—Nitrogen cylinder; 2—Nitrogen inlet valve; 3—Gas generator tank; 4—Gas mixture outlet valve; 5—Buffer tank; 6—Rotameter; 7—Packed column; 8—Rich solution collection tank; 9—Online detector; 10—Peristaltic pump; 11—Feed solution tank.

2.4. Quantum Chemical Calculations

Based on Density Functional Theory (DFT), analyzing the interaction forces between solvent molecules and benzene at the microscopic molecular level can contribute to understanding the absorption mechanism and provide a novel strategy for the theoretical screening of suitable solvents. The quantum chemistry software Gaussian 16 (version A.03) [29] was employed to perform geometry optimization and energy calculations for benzene and solvent molecules at the M062X/6-311G** level, with the ΔGsol computed using the solvent model based on density (SMD) solvation model. On the basis of the optimized structures from Gaussian, the σ-profile diagrams were generated using the Dmol3 module in Materials Studio 2017 to analyze trends in molecular surface electrostatic distribution [30]. Finally, electrostatic potential (ESP) analysis and independent gradient model (IGM) analysis [31,32] were conducted using the wavefunction analysis software Multiwfn 3.7 [33,34]. Energy decomposition [35] was carried out with the Psi4 software [36]. All results were visualized using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD, version 1.9.3) [37].

3. Results

3.1. Screening Method for Washing Oil Composite Solvent

ΔGsol is a thermodynamic parameter that characterizes the change in Gibbs free energy when a solute dissolves from the gas phase into a solvent. It serves as a key indicator for evaluating the absorption performance of solvents [38]. A negative value of ΔGsol indicates a spontaneous absorption process, and the larger the absolute value of the negative value, the stronger the absorption capacity.

In this study, 26 commonly used organic reagents with diverse structures were selected. The ΔGsol of benzene in these solvents was computed using Gaussian 16 W, and the K was experimentally determined using the headspace method. Both the experimental and computational results are summarized in Table 1. The relationship between ΔGsol and lnK is given by the following equation [39,40]:

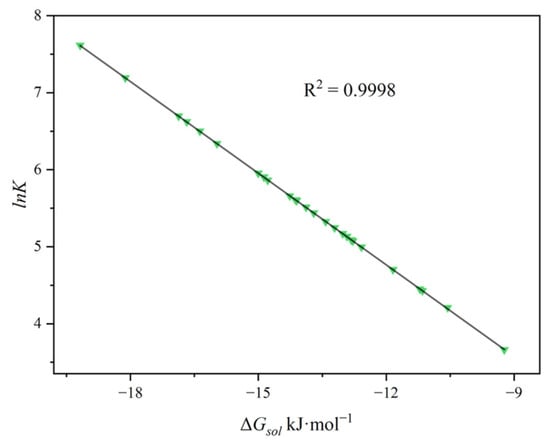

where R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J·mol−1·K−1) and T is the temperature in K. A linear fitting was performed between ΔGsol and lnK, and the result is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

ΔGsol and lnK for different solvents.

Figure 2.

Screening results of candidate solvents for benzene absorption: correlation between the calculated solvation free energy (ΔGsol) and the gas–liquid partition coefficient.

Under the solvent systems and experimental conditions investigated in this study, a strong correlation was observed between ΔGsol and lnK, with a correlation coefficient R2 = 0.9998. These results demonstrate that calculating the ΔGsol of benzene in various solvents can effectively predict and compare the absorption capacities of different solvents, thereby providing a theoretical basis for screening highly efficient absorbents, consistent with screening strategies reported in recent computational thermodynamic studies [41,42,43].

As shown in Table 1, six solvents—sulfolane (SUL), N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP), tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (TGDE), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), triethylene glycol butyl ether (TGBE), and dibutyl adipate (DBA)—exhibited significantly higher K values for benzene compared to other solvents. Specifically, their K values (SUL: 2026.46, NMP: 1329.84, TGDE: 808.99, DBP: 751.91, TGBE: 665.09, DBA: 565.76) were considerably higher than that of diethylene glycol butyl ether (K = 384.91). More importantly, compared to water (K = 38.94), which is commonly used in industrial applications, the K values of these six solvents were higher by factors of 50.74, 33.30, 20.26, 18.83, 16.65, and 14.17, respectively. The corresponding ΔGsol values (ranging from −19.18 to −15.97 kJ·mol−1) indicate strong affinity between these solvents and benzene molecules. In contrast, water has a ΔGsol of only −9.23 kJ·mol−1, indicating very low absorption capacity, a limitation frequently noted in conventional aqueous absorption systems due to the hydrophobic nature of benzene [44,45]. Similarly, other highly polar protic solvents, such as ethylene glycol (K = 205.56), pentanol (K = 110.07), and octanol (K = 85.59), showed relatively low K values, due to their insufficient lipophilicity and significant polarity mismatch with benzene, suggesting poor absorption performance that fails to meet the requirements for high efficiency.

To further evaluate solvent volatility, the saturated vapor pressure data of the six candidate solvents were obtained. The results showed that at 298 K, the saturated vapor pressure of NMP was 0.345 mmHg [46], which is significantly higher than those of the other solvents—for example, 0.0019 mmHg for TGDE at 298 K [47], 0.0062 mmHg for SUL at 300.6 K [48], and 2.01 × 10−5 mmHg for DBP at 298 K [49]. Since the saturated vapor pressure of a solvent is positively correlated with its volatility, a high vapor pressure can lead to significant solvent loss due to evaporation. Therefore, to minimize solvent loss in both experimental and industrial applications, NMP was excluded from the candidate list.

Consequently, DBP, SUL, TGDE, DBA, and TGBE were selected as compound components for washing oil for further theoretical analysis and experimental investigation.

3.2. Absorption–Desorption Experiment of Washing Oil Composite Solvent

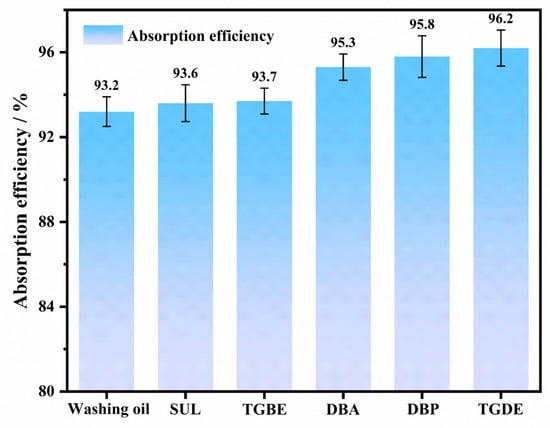

Based on the screening results, dynamic absorption experiments of benzene were conducted in a counter-current packed column absorption setup to validate the absorption performance and optimize the washing oil composite system. To ensure data reliability, all dynamic absorption and regeneration experiments were performed in triplicate. The results reported in this section are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation, as indicated by the error bars in the figures. The experimental results are shown in Figure 3. Compared to the washing oil solvent, the pure composite component absorbents exhibited stronger benzene absorption capacities. Specifically, the absorption efficiencies of DBA, DBP, and TGDE were 2.1%, 2.6%, and 3.0% higher than that of washing oil, respectively, demonstrating significant advantages. In contrast, TGBE, with a relatively lower partition coefficient (K = 665.09), showed only marginal improvement in absorption performance, resulting in a negligible difference compared to washing oil. Meanwhile, the enhancement in absorption performance for SUL was also limited, which may be attributed to its high viscosity (10.07 mPa·s at 298 K) hindering mass transfer during absorption. TGDE stood out due to the highest improvement in absorption efficiency (3.0%). Moreover, TGDE possesses relatively low viscosity [50], which helps reduce flow resistance during solvent absorption and enhances mass transfer efficiency. It also exhibits excellent thermal and chemical stability. Therefore, considering both absorption performance and physical properties, TGDE was selected as the composite solvent.

Figure 3.

Absorption efficiency of benzene by washing oil solvent and six composite components.

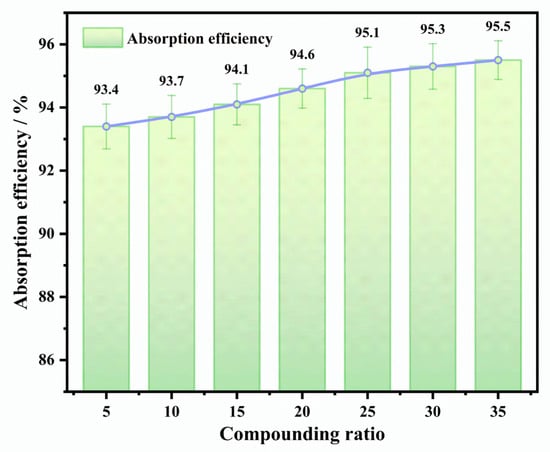

To investigate the effect of TGDE compounding ratio on absorption performance, TGDE was compounded with washing oil at mass ratios of 5 wt.%, 10 wt.%, 15 wt.%, 20 wt.%, 25 wt.%, 30 wt.%, and 35 wt.%. The absorption efficiency results are shown in Figure 4. As the proportion of TGDE increased, the absorption efficiency continued to improve, indicating that TGDE significantly enhanced the benzene absorption capacity of the system by strengthening intermolecular interactions. However, when the TGDE ratio exceeded 25 wt.%, the incremental gain in absorption efficiency per 5 wt.% increase was only 0.2%, demonstrating a marginal effect. Considering the cost-effectiveness for industrial applications, a TGDE compounding ratio of 25 wt.% was identified as the optimal choice to balance high absorption efficiency and economic feasibility.

Figure 4.

Effect of TGDE mass fraction in the composite washing oil solvent on benzene absorption efficiency.

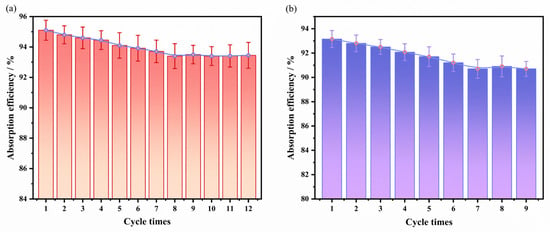

From both environmental and economic perspectives, the regenerability of solvents is a critical indicator for assessing their industrial applicability. Therefore, in this study, the benzene-rich solution obtained after absorption was regenerated via vacuum distillation (368 K, 0.1 atm, 1 h). It should be noted that these laboratory conditions are milder than typical industrial practices (413–443 K under slight excess pressure); thus, while the current results demonstrate feasibility, the long-term stability under harsher industrial regeneration conditions requires further validation. Multiple absorption–desorption cycles were conducted to evaluate cycling stability. Multiple absorption–desorption cycles were conducted to evaluate cycling stability. The cycling performance of washing oil and the TGDE composite solvent (25 wt.%) is shown in Figure 5. The results indicate that the absorption efficiency of pure washing oil decreased to 90.7% after 9 cycles, while the TGDE composite solvent maintained an absorption efficiency of 93.5% after 9 cycles and remained stable at 93.4% even after 12 cycles, demonstrating excellent cycling stability. Furthermore, mass loss analysis revealed that the mass loss of the TGDE composite solvent after 12 cycles was only 2.4%, significantly lower than the 3.4% loss observed for pure washing oil after 9 cycles. These results suggest that the molecular interactions between TGDE and washing oil not only enhance absorption efficiency but also effectively reduce solvent loss by improving thermal stability and reducing volatility.

Figure 5.

(a) The cyclic regeneration performance of the optimal mixed solvent (25 wt.% TGDE- washing oil) and (b) pure washing oil over multiple absorption–desorption cycles.

3.3. Quantum Chemical Calculation Analysis

3.3.1. ESP and σ-Profile Analysis

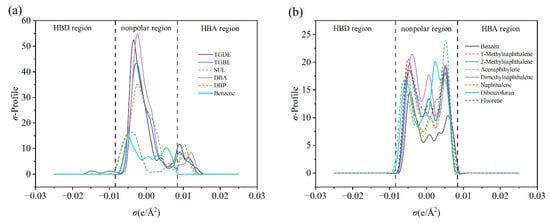

Molecular surface electrostatic potential (ESP) analysis and σ-profile function analysis were employed to reveal the characteristics of molecular surface charge distribution and polarity features, respectively. As shown in Figure S1, benzene and the components of washing oil solvent exhibit similar ESP distribution patterns; the negative potential regions (blue) are primarily concentrated at the center of the benzene ring, while the positive potential regions (red) are distributed around the hydrogen atoms, demonstrating a typical charge distribution mode of non-polar aromatic molecules. The σ-profile analysis (Figure 6b) further supports this conclusion. The peaks of both benzene and washing oil components are located within the non-polar region (−0.0082 e/Å2 < σ < 0.0082 e/Å2), with no observable peaks in the hydrogen bond donor (HBD, σ < −0.0082 e/Å2) or hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA, σ > 0.0082 e/Å2) regions [51]. In contrast, the ESP distribution of the composite solvents (Figure S2) shows that the negative potential regions are mainly concentrated around oxygen atoms. This suggests the presence of electrostatic attraction between the hydrogen atoms of benzene molecules and the oxygen atoms in the composite solvent molecules. Meanwhile, ESP analysis indicates that the positive and negative charge distributions on the molecular surfaces of DBA and TGDE are more uniform compared to those of SUL and DBP, indicating relatively weaker overall polarity.

Figure 6.

(a) σ-Profiles of composite components and benzene molecules; (b) σ-Profiles of washing oil components and benzene molecules.

The σ-profile analysis of the composite solvents (Figure 6a) reveals their significant polar characteristics. All composite components exhibit high-intensity peaks in the HBA region, indicating strong hydrogen bond acceptor capacity, while only a weak peak is observed in the HBD region of TGBE. In addition, a distinct high-intensity sharp peak is also present in the non-polar region for all composite components, with DBA and TGDE showing the highest peak values. This indicates that the composite solvents possess both polar and non-polar interaction sites. According to the similarity–intermiscibility theory, the interactions between washing oil components and benzene molecules are primarily non-polar. In contrast, the composite solvents, with their dual polar and non-polar characteristics, form multiple types of interactions with benzene molecules. This suggests that, compared to the single non-polar interaction mode dominant in washing oil, the composite solvents can more effectively promote the absorption of benzene molecules—consistent with the previously observed enhanced benzene absorption capacity of the composite solvents in absorption experiments.

3.3.2. IGM Analysis

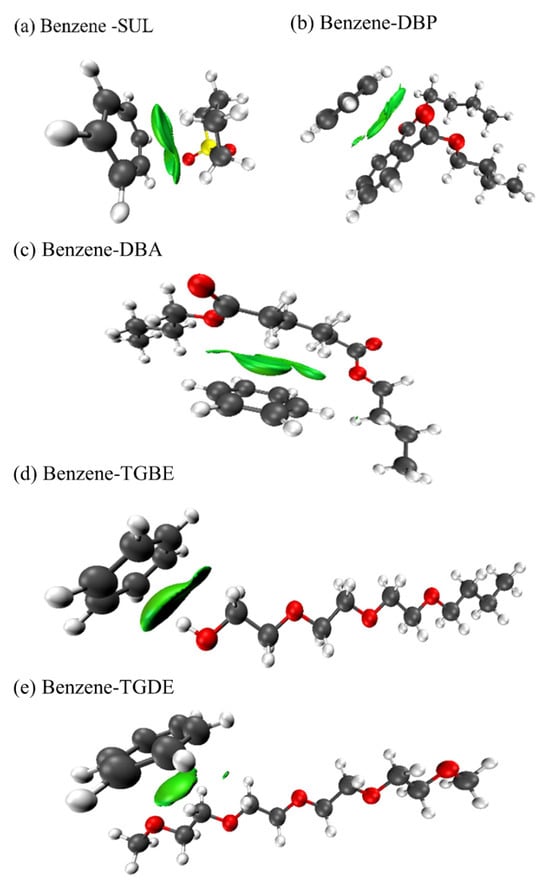

Electrostatic potential (ESP) and σ-profile analysis provided insights into the potential binding sites between benzene and solvent molecules, along with a qualitative assessment of the solvents’ polarity. To further quantitatively characterize the types and relative strengths of weak interactions between benzene and the components of both washing oil and composite solvents, the IGM analysis was employed (further details are provided in Figure S3).

The IGM results indicate that the weak interactions between benzene and washing oil components primarily arise from π–π stacking between benzene rings, which is visualized as light green regions representing van der Waals interactions in Figure 7. In contrast to the washing oil components, π–π interactions between benzene and the composite solvent components are largely absent, except in the case of DBP. Instead, distinct weak interaction regions are identified between hydrogen atoms of benzene and oxygen atoms in the composite solvents. For instance, specific C–H···O hydrogen bonds are observed between benzene and SUL, DBA, and DBP. In the case of TGBE, which contains a hydroxyl group (see Figure S4 for more details), an O–H···π hydrogen bond is formed. Similarly, TGDE, which contains only ether groups, exhibits a C–H···π hydrogen bond interaction with benzene [52,53].

Figure 7.

IGM isosurface plots revealing weak intermolecular interactions between benzene and selected solvent molecules (blue: strong attraction; green: van der Waals).

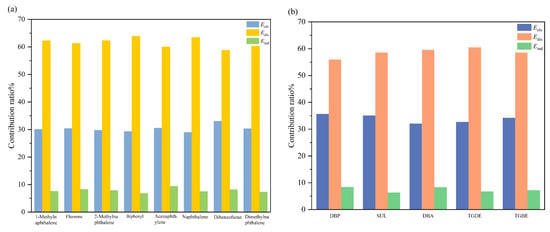

3.3.3. SAPT Energy Analysis

To further evaluate the contribution of different interactions to absorption, the binding energy (ΔΕbind) between benzene and each solvent molecule was computed and decomposed into the following four components: electrostatic energy (Εele), induction energy (Εind), dispersion energy (Εdis) and exchange energy (Εexc). Among these, Εele, Εind and Εdis are attractive and favor absorption. The decomposed binding energies for each solvent are summarized in Table S3. Figure 8 illustrates the percentage contribution of each energy component to the total attractive energy (E = Eele + Eind + Edis).

Figure 8.

Percentage contributions of different interaction energy components (electrostatic energy Eele, induction energy Eind, and dispersion energy Edis) to the total attractive binding energy: (a) benzene molecule with washing oil solvent, (b) benzene molecule with mixed solvent.

The SAPT results reveal that for both washing oil and composite solvent components, dispersion energy constitutes the dominant contribution to the binding energy, followed by electrostatic energy, while induction energy accounts for only about 10%. Furthermore, it is observed that the electrostatic contribution is slightly higher in composite solvents than in washing oil components, indicating stronger electrostatic interactions between the composite solvents and benzene. This finding is consistent with the ESP analysis. However, the enhancement in electrostatic interactions is modest. Although hydrogen bonding exists between the composite solvents and benzene, the strength of these interactions is relatively low, and dispersion forces still play a significant role even in these weak hydrogen-bonded systems [54]. Thus, the overall increase in electrostatic contribution remains limited.

4. Discussion

The robust linear correlation between ΔGsol and lnK validates solvation free energy as an effective descriptor for screening benzene absorbents. The superior performance of the selected solvents (e.g., TGDE, SUL, DBP) over highly polar protic solvents (e.g., water, alcohols) aligns with the “like dissolves like” principle, attributed to their favorable lipophilicity and electron density distributions. Mechanistically, SAPT and IGM analyses demonstrate that while dispersion forces dominate the washing oil system, TGDE enhances absorption via synergistic dispersion and weak electrostatic interactions, specifically C–H···O hydrogen bonds.

Two primary limitations of this study should be noted. First, a simplified model washing oil was employed to ensure theoretical precision and experimental reproducibility; however, the exclusion of heavy polymeric components typical of industrial fluids may underestimate thermal stability. Second, solvent regeneration was conducted under mild laboratory vacuum conditions, which differ from the harsher high-temperature, slight excess pressure environment of industrial coking. Consequently, while the TGDE composite system exhibits significant potential, its long-term stability and separation efficiency under industrial conditions warrant further pilot-scale validation. Future research will address these engineering challenges through comparative studies using real industrial washing oil and petroleum-based analogs.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a combined theoretical and experimental strategy was successfully established to screen and optimize high-efficiency absorbents for benzene recovery. The results demonstrate that solvation free energy is a reliable descriptor for solvent screening. The optimized TGDE composite solvent exhibited a benzene absorption efficiency of 96.2%, significantly outperforming conventional washing oil. Mechanistic studies indicate that the interactions between washing oil and benzene are dominated by dispersion forces, while the composite components introduce additional weak electrostatic interactions, such as C–H···O hydrogen bonding, which act synergistically to improve absorption performance. The dual polar and non-polar character of the composite solvents enables superior absorption compared to washing oil alone. Finally, future research will focus on a comparative investigation of 1-methylnaphthalene, isoquinoline, quinoline and model components of petroleum-based wash oil to further elucidate how these individual constituents and different oil sources affect the overall properties and stability of the absorbent system. By integrating theoretical calculations with experimental validation, this study proposes a strategy for designing efficient and recyclable VOC absorption systems, providing a solid theoretical and technical foundation for the industrial treatment of benzene-containing waste gas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos17010052/s1, Figure S1: ESP diagram of benzene and washing oil components Figure S2: ESP diagram of composite components; Figure S3: IGM analysis of benzene and wash oil components; Figure S4: Geometric configurations and atomic partial charge analysis of weak hydrogen bonding interactions between benzene and solvent molecules; Table S1: Washing oil solvent composition table; Table S2: Table of preselected solvents; Table S3: Binding energy results of washing oil components and composite components with benzene.

Author Contributions

C.Q.: Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—Review and editing. Z.J.: Data curation, Formal analysis. M.C. (Meisi Chen): Supervision, Funding acquisition. L.W.: Visualization, Writing—Review and editing. S.L.: Data curation, Writing—Review and editing. G.Z.: Software. M.C. (Muhua Chen): Conceptualization. X.Z.: Investigation. B.F.: Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22508187) and Jiangsu Province Higher Education Institutions Basic Science (Natural Science) Research General Project (25KJB530003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

Chengyi Qiu is an employee of Synorm Chemical Co., Ltd. The paper reflects the views of the scientists and not the company.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ΔGsol | solvation free energy |

| TGDE | tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether |

| VOC | volatile organic compound |

| DESs | deep eutectic solvents |

| K | The partition coefficient |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| IGM | independent gradient model |

| ESP | electrostatic potential |

| SUL | sulfolane |

| NMP | N-methylpyrrolidone |

| DBP | dibutyl phthalate |

| TGBE | triethylene glycol butyl ether |

| DBA | dibutyl adipate |

References

- Fruscella, W. Benzene. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; Kirk-Othmer, Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-471-48494-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Bian, J.; Ruan, D. Volatilization of Benzene on Soil Surface under Different Factors: Evaluation and Modeling. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2024, 34, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granda, M.; Blanco, C.; Alvarez, P.; Patrick, J.W.; Menéndez, R. Chemicals from Coal Coking. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1608–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetisov, V.; Gonopolsky, A.M.; Davardoost, H.; Ghanbari, A.R.; Mohammadi, A.H. Regulation and Impact of VOC and CO2 Emissions on Low-Carbon Energy Systems Resilient to Climate Change: A Case Study on an Environmental Issue in the Oil and Gas Industry. Energy Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1516–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water, D. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. Technical Fact, 2019. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Kumari, P.; Soni, D.; Aggarwal, S.G. Benzene: A Critical Review on Measurement Methodology, Certified Reference Material, Exposure Limits with Its Impact on Human Health and Mitigation Strategies. Environ. Anal. Health Toxicol. 2024, 39, e2024012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-T. A Survey on Toxic Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): Toxicological Profiles, Health Exposure Risks, and Regulatory Strategies for Mitigating Emissions from Stationary Sources in Taiwan. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaheem, Y.; Alomair, A.; Vinoba, M.; Pérez, A. Polymeric Gas-Separation Membranes for Petroleum Refining. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 2017, 4250927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isinkaralar, K. Experimental Evaluation of Benzene Adsorption in the Gas Phase Using Activated Carbon from Waste Biomass. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 19901–19910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.; Yilmaz, D. Absorptive Removal of Volatile Organic Compounds from Flue Gas Streams. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2006, 84, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biard, P.-F. Volatile Organic Compounds Absorption in Non-Aqueous Solvents: A Critical Review Based on Hydrodynamics and Mass Transfer Considerations. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, H.; Zhang, T.; Cui, J.; Li, X.; Crittenden, J.; Li, X.; He, L. Novel Off-Gas Treatment Technology to Remove Volatile Organic Compounds with High Concentration. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 2594–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hao, M.; Wu, T.; Li, Y. Efficient Treatment of Crude Oil-Contaminated Hydrodesulphurization Catalyst by Using Surfactant/Solvent Mixture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannikov, L.P. BTX Capture from Coke-Oven Gas. Coke Chem. 2014, 57, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, K.; Wanko, H.; Ulrich, J. Absorption of Volatile Organic Compounds in Biodiesel. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2006, 84, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erto, A.; Lancia, A. Solubility of Benzene in Copolymer Aqueous Solutions for the Design of Gas Absorption Unit Operations. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 187, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecer, M.; Simkova, L.; Koutnik, I. The Effect of Washing Oil Quality and Durability on the Benzol Absorption Efficiency from Coke Oven Gas. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 70, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, D.; Bannikov, A.; Bannikov, L.; Borisenko, O.; Shishkin, A.; Gavrilovs, P.; Tertychnyi, V. Impact of Wash Oil Composition on Degradation: A Comparative Analysis of “Light” and “Heavy” Oils. Resources 2024, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoś-Chełstowska, P.; Słupek, E.; Kramarz, A.; Dobrzyniewski, D.; Szulczyński, B.; Gębicki, J. Green Monoterpenes Based Deep Eutectic Solvents for Effective BTEX Absorption from Biogas. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 188, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bi, R.; Ge, J.; Xu, P. VOCs Absorption Using Ionic Liquids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 363, 132265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, J.; Sun, T.; Yu, F.; Li, C. The Absorption Performance of Ionic Liquids–PEG200 Complex Absorbent for VOCs. Energies 2021, 14, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, G.; Gui, C.; Song, M.; Zhao, F.; Yang, S.; Lei, Z.; Xu, P. Enhancing Aromatic VOCs Capture Using Randomly Methylated β-Cyclodextrin-Modified Deep Eutectic Solvents. AIChE J. 2025, 2025, e18918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmad, S.; Xie, Y.; Mikkola, J.-P.; Ji, X. Screening of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) as Green CO2 Sorbents: From Solubility to Viscosity. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, A.; Finger, E.J. Co-Solvent Selection and Recovery. Adv. Environ. Res. 2004, 8, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C.; Song, M.; Liu, Q.; Xiang, D.; Lu, P.; Fourmentin, S.; Hua, C.; Lei, Z. Rational Screening of Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Removal of Halogenated Volatile Organic Compounds. AIChE J. 2025, 71, e18858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chao, K.; Jin, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, G.; Fu, B. Screening of Toluene Absorbents Based on Molecular Simulation and Experimental Investigation on Novel Compound Solvents. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, M.-D.; Couvert, A.; Couriol, C.; Amrane, A.; Le Cloirec, P.; Renner, C. Determination of the Henry’s Constant and the Mass Transfer Rate of VOCs in Solvents. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 150, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjoudj, R.; Monnier, H.; Roizard, C.; Lapicque, F. Absorption of Chlorinated VOCs in High-Boiling Solvents: Determination of Henry’s Law Constants and Infinite Dilution Activity Coefficients. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 2238–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H. Gaussian 16, Revision A. 03; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, E.; Oldland, R.; Liu, Y.A.; Wang, S.; Sandler, S.I.; Chen, C.-C.; Zwolak, M.; Seavey, K.C. Sigma-Profile Database for Using COSMO-Based Thermodynamic Methods. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 4389–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Rubez, G.; Khartabil, H.; Boisson, J.-C.; Contreras-García, J.; Hénon, E. Accurately Extracting the Signature of Intermolecular Interactions Present in the NCI Plot of the Reduced Density Gradient versus Electron Density. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 17928–17936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Independent Gradient Model Based on Hirshfeld Partition: A New Method for Visual Study of Interactions in Chemical Systems. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A Comprehensive Electron Wavefunction Analysis Toolbox for Chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C.; Villarim, P.; Lei, Z.; Fourmentin, S. VOC Absorption in Supramolecular Deep Eutectic Solvents: Experiment and Molecular Dynamic Studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turney, J.M.; Simmonett, A.C.; Parrish, R.M.; Hohenstein, E.G.; Evangelista, F.A.; Fermann, J.T.; Mintz, B.J.; Burns, L.A.; Wilke, J.J.; Abrams, M.L.; et al. Psi4: An Open-source Ab Initio Electronic Structure Program. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarim, P.; Genty, E.; Zemmouri, J.; Fourmentin, S. Deep Eutectic Solvents and Conventional Solvents as VOC Absorbents for Biogas Upgrading: A Comparative Study. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 136875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Gajardo-Parra, N.F.; Chen, M.; Chen, B.; Sadowski, G.; Held, C. Aromatic Volatile Organic Compounds Absorption with Phenyl-based Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Molecular Thermodynamics and Dynamics Study. AIChE J. 2023, 69, e18053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C. Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents as Attractive Media for Low-Concentration Hydrophobic VOC Capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 424, 130420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyono, S.; Hizaddin, H.F.; Alnashef, I.M.; Hashim, M.A.; Fakeeha, A.H.; Hadj-Kali, M.K. Separation of BTEX Aromatics from N-Octane Using a (Tetrabutylammonium Bromide + Sulfolane) Deep Eutectic Solvent—Experiments and COSMO-RS Prediction. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 17597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhang, X.; Ruan, J.; Sundmacher, K. Screen Ammonium-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents for CO2 Capture: Extended UNIFAC-DES, Calibrated COSMO-RS, and Experiment. AIChE J. 2025, 2025, e70121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, D.; Alhadid, A.; Minceva, M. Assessment of COSMO-RS for Predicting Liquid–Liquid Equilibrium in Systems Containing Deep Eutectic Solvents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 11110–11120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q. Advances in Adsorption, Absorption, and Catalytic Materials for VOCs Generated in Typical Industries. Energies 2024, 17, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xia, L.; Xiang, S.; Dong, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Prediction, Application, and Mechanism Exploration of Liquid–Liquid Equilibrium Data in the Extraction of Aromatics Using Sulfolane. Processes 2023, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubert, T.E.; Danner, R.P. Physical and Thermodynamic Properties of Pure Chemicals: Data Compilation; Hemisphere Pub. Corp: New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 0-89116-948-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tetraethylene Glycol Dimethyl Ether CAS 143-24-8|820959. Available online: https://www.merckmillipore.com/HK/en/product/Tetraethylene-glycol-dimethyl-ether,MDA_CHEM-820959 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Shipkowski, K.A.; Cora, M.C.; Cesta, M.F.; Robinson, V.G.; Waidyanatha, S.; Witt, K.L.; Vallant, M.K.; Fallacara, D.M.; Hejtmancik, M.R.; Masten, S.A.; et al. Comparison of Sulfolane Effects in Sprague Dawley Rats, B6C3F1/N Mice, and Hartley Guinea Pigs After 28 Days of Exposure via Oral Gavage. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Draft Fate and Physical Chemistry Assessment for Dibutyl Phthalate (DBP); US EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Henni, A.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P.; Chakma, A. Densities, Viscosities, and Derived Functions of Binary Mixtures: (Tetraethylene Glycol Dimethyl Ether + Water) from 298.15 K to 343.15 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2004, 49, 1778–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zeng, S.; Huang, Y.; Afzal, R.M.; Zhang, X. Estimation of Heat Capacity of Ionic Liquids Using Sσ-profile Molecular Descriptors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 12987–12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mino, C.; Seel, A.G.; Clancy, A.J.; Headen, T.F.; Földes, T.; Rosta, E.; Sella, A.; Skipper, N.T. Strong Structuring Arising from Weak Cooperative O-H···π and C-H···O Hydrogen Bonding in Benzene-Methanol Solution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novoa, J.J.; Mota, F. The C–H ··· π Bonds: Strength, Identification, and Hydrogen-Bonded Nature: A Theoretical Study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 318, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamian, S.; Lu, T.; Kruse, H.; Emamian, H. Exploring Nature and Predicting Strength of Hydrogen Bonds: A Correlation Analysis Between Atoms-in-Molecules Descriptors, Binding Energies, and Energy Components of Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2019, 40, 2868–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.