Abstract

China’s rapid urbanization has precipitated severe atmospheric pollution, drawing sustained scientific and policy attention. Although nationwide implementations of emission control measures have achieved measurable reductions in ambient NO2 concentrations, fundamental uncertainties persist in quantifying anthropogenic NOx emission and their interannual variability. In this study, NOx emissions over China are inferred using the Regional Air Pollutant Assimilation System (RAPAS) combined with ground-based hourly NO2 observations, and a detailed analysis of the spatiotemporal variation patterns of NOx emissions is also provided. Nationally, most sites display declining NO2 concentrations during 2014–2021, with steeper reduction trends in winter, particularly in pollution hotspots. The RAPAS-optimized NOx emission estimates demonstrate superior performance relative to prior inventories, with site-averaged biases, root mean square errors, and correlation coefficients improved substantially across all geographic regions in China. The trajectories of changes in NOx emissions exhibit marked regional disparities: South and Northeast China experienced more than 8.0% emission growth during 2014–2017, while NOx emissions in northwest and southwest China increased by 35% and 26%, significantly higher than those in East China. The reductions accelerated significantly post 2018, particularly in central and eastern regions (more than −20%). The interannual variation in NOx emissions in the five national urban agglomerations shows a similar trend of first rising and then decreasing. The NOx emissions of Anhui, Yunnan, Shanxi, Gansu and Xinjiang provinces increased significantly from 2014 to 2017, while the emissions of Shandong and Zhejiang decreased at a relatively high rate (more than 80 Gg per year). These findings are helpful to provide a more comprehensive understanding of current NOx pollution and provide scientific basis for policymakers to propose effective strategies.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen oxides (NOx), comprising nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), critically synthesize atmospheric chemistry in both stratospheric and tropospheric processes. NOx emissions derive principally from anthropogenic sources, primarily biomass and fossil fuel combustion and transportation, alongside natural processes (soil emissions and lightning). Photochemical reactions involving NOx govern tropospheric ozone (O3) formation, while specific environmental conditions enable direct or indirect radiative forcing [1]. NO2, as the primary atmospheric form of NOx, directly influences atmospheric temperature and chemical composition [2]. The interaction between NO2 and NO plays a critical role in modulating O3 concentrations, with NO2 photodissociation serving as a key driver of O3 photochemical formation [3]. Both NO2 and O3 inflict documented damage on human, animal, and plant health [4], with the health hazards of NO2 paralleling the impacts of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) yet exhibiting slower decline rates [5]. Controlling NO2 concentrations effectively reduces photochemical smog, improves atmospheric visibility, and mitigates adverse health effects.

Since 2013, the implementation of stringent clean air policies has led to significant improvements in air quality across China. The national average NO2 concentration has decreased by over 24% in 2021 compared to 2013 levels [6]. While this meets the Grade I annual limit specified in China’s current Ambient Air Quality Standards (GB 3095-2012), it remains above the annual guideline value (10 μg/m3) recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) Air Quality Guideline 2021 [7]. In contrast, the annual mean PM2.5 concentration over China in 2022 was roughly six times higher than the current guideline of the WHO [8]. Notably, O3 represents the sole criteria pollutant exhibiting increasing trends during the period [6]. Consequently, monitoring the concentrations and trends of NO2 as a precursor of PM2.5 and O3 is of profound significance, while reducing NO2 levels represents an urgent environmental imperative. Accurate quantification of atmospheric pollutant concentrations is fundamental for conducting temporal and spatial analyses of air pollution. Satellite-based atmospheric pollution observations offer extensive spatial coverage, enabling quantitative global-scale environmental assessments that partially overcome the spatial coverage limitations of ground monitoring. Meanwhile, numerous studies have investigated NO2 spatiotemporal variations using ground-based observations globally [9,10,11]. For example, a period of five years model results based on in–situ measurements were used for an overview of the background NO2 evolution in urban area in Braila, a medium-polluted city in Europe [12]. Clear improvements in primary pollutants NO2 and SO2 were observed in a fast-growing Middle Eastern city, Dubai, despite its growing population [13]. In China, research on NO2 characteristics predominantly focuses on economically developed megacities and pollution hotspots [14,15,16]. Temporally, previous studies integrating satellite products with ground observations typically employed short-term analyses or specific pollution episodes to reveal interannual, monthly, and seasonal NO2 variations [17,18].

Accurate capture of emission source characteristics forms the foundation of high-level air quality forecasting and serves as a prerequisite for effective emissions reduction. There are mainly two approaches for establishing emission inventories. One is the “bottom-up” method, which derives pollution sources from energy consumption statistics of anthropogenic activities and various emission factors [19,20,21,22], though it exhibits substantial uncertainties and encounters severe data release lags [23]. Another method is the “top-down” method, which inversely estimates regional or global emissions using extensively monitored pollutant data from satellites or ground observations [24,25,26]. Over the past decades, researchers worldwide have employed diverse techniques to inverse emissions of multiple conventional pollutants [27,28,29,30], collectively reflecting the evolution of global and domestic economic development [31,32,33]. For instance, multi-year global NOx emissions have been inverted using the conservation-of-mass method integrated with multi-satellite datasets [29,34]. Multiple emission inventories are used for comparison to investigate the uncertainties in NOx emission estimates over East Asia, including four satellite-derived inventories and five bottom-up inventories [35]. The ensemble Kalman filter coupled with satellite column concentrations has further updated prior inventory underestimations in Eastern China, Western United States, and Central-Western Europe [36], thereby enhancing the accuracy of bottom-up emission inventories [2].

Inverting emission inventories using remote sensing data capitalizes on satellites’ capability for spatially continuous monitoring of pollution source variations. For example, methane emissions over Texas and NOx emissions from selected cities in North America, Europe, and East Asia were quantified based on observations of the TROPOMI instrument [37,38]. Emissions of aerosols and greenhouse gases from forest fires across South Asia were estimated using thermal anomalies and fire satellite products [39]. However, biases in satellite retrievals substantially impact estimated emission magnitudes [36,40]. Challenges persist in achieving consistent inversion results across different satellites [41] or distinct products from identical satellites [42] due to disparities in sensitivity, retrieval algorithms, and spatiotemporal sampling [43,44]. Relative to satellite products, intensive hourly ground observations offer superior temporal resolution and accuracy, provide enhanced spatiotemporal emission characterization, remain unaffected by meteorological or pollution conditions, and—through strategic site placement near source regions—rapidly detect emission fluctuations. Ground-based data thus enable spatiotemporal emission trend assessment and new source identification. Inverse studies targeting emissions during major international events, sports competitions, emergencies, control measures, or specific pollution policies allow tailored evaluation of pollution control efficacy, ensuring air quality management during critical periods. For example, during China’s implementation of the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan, studies assimilating ground observations generated monthly CO emissions, revealing variation patterns, and investigating the spatiotemporal impacts of abatement measures [45,46]. Additional research assimilated ground data to invert NOx and black carbon (BC) emissions in early 2020, uncovering post-pandemic spatiotemporal patterns of NOx across China and BC emissions in Eastern and Northern China [47,48]. Collectively, these demonstrate that ground-based data assimilation reduces inventory uncertainties while improving model predictive performance. Long-term air quality trends reflect cumulative effects of multi-year control measures, necessitating high-resolution continuous emission inventories for comprehensive regional pollution and policy assessment. Given that most existing NOx inversions rely on satellite data, multi-year ground observation-based inversion studies are imperative to elucidate long-term NOx emission characteristics.

This study used national ground monitoring station data and the established Regional multi-Air Pollutant Assimilation System (RAPAS) to reveal multi-year seasonal NO2 patterns and generate a ground-observation-constrained, high-resolution anthropogenic NOx emission inventory for China (2014–2021). Then, the reliability of the inventory was quantitatively evaluated, followed by the analysis of multi-year spatiotemporal variations and emission trends across distinct geographic regions. The national-scale estimations of NOx emission pinpoint the interannual variation trend of anthropogenic NOx emissions, critically reflect socioeconomic dynamics from an emission perspective, and provide essential insights into the effectiveness of a series of air pollution prevention and control action plans implemented in China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Ground-Based Observations

The ground-based real-time NO2 concentration data utilized in this study were acquired from the China National Environmental Monitoring Centre’s National Urban Air Quality Real-time Release Platform (https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/, accessed on 9 December 2025), with measurements predominantly conducted via chemiluminescence at monitoring sites positioned 3–20 m above ground level, which can be affected by high levels of ambient reactive nitrogen species [49]. The selected data comprehensively covered 31 provincial-level administrative regions across mainland China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), with station distribution demonstrating denser coverage in economically developed eastern coastal areas and sparser coverage in central and western regions. All stations recorded measurements at 1 h intervals, with NO2 concentrations expressed in μg/m3. Following the specifications for NO2 in the Ambient Air Quality Standards (GB 3095−2012), rigorous quality control preprocessing was implemented: eliminating records with missing or negative values; rejecting daily data with fewer than 20 h of valid observations to ensure reliable daily average calculations. Pursuant to the unified national standards implemented on 1 September 2018, ground-level pollutant concentration measurements transitioned from the standard temperature and pressure (STP) state (273 K, 1013.25 hPa) to reference conditions (298.15 K, 1013.25 hPa). All concentrations were uniformly converted to STP-equivalent values to maintain data consistency.

2.1.2. Meteorological Data

The initial and lateral boundary conditions for meteorological data simulations were derived from the NCEP FNL datasets generated by the Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS), assimilated from ground station observations, satellite data, and aircraft measurements, featuring 1° × 1° spatial resolution with global coverage at a 6 h interval. The datasets are published by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) as the FNL (Final) Operational Global Analysis data (http://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds083.2/, accessed on 9 December 2025), with primary variables including air temperature, sea surface temperature, wind speed, wind direction, surface pressure, sea-level pressure, relative humidity, and soil temperature, etc.

China’s ground station meteorological observation data are employed for validating simulated meteorological conditions, obtained from the publicly accessible FTP server of the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC, ftp://ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/noaa/isd-lite/, accessed on 9 December 2025), with variables including air temperature, wind speed, wind direction, atmospheric pressure, precipitation, dew point, and cloud cover. This study employs over 400 station records primarily featuring 3 h temporal resolutions in recent years, while a minority of stations provide 1 h interval data.

2.1.3. Anthropogenic Emissions

Anthropogenic emissions over mainland China were obtained from the Multi-resolution Emission Inventory (MEIC [15], http://meicmodel.org/, accessed on 9 December 2025) developed by Tsinghua University for 2014–2021, while other East Asian regions utilized the MIX inventory [50]. The emission inventories encompass five sectors: industry, power, transportation, residential, and agriculture. Both MEIC and MIX inventories possess equivalent spatial resolutions of 0.25° × 0.25°, and were interpolated to match the model grid resolution (36 km × 36 km). Biogenic emissions originated from the Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN) model [51], sharing identical simulation domains and spatial resolution with the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model and driven by Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) outputs. Biomass burning emissions were excluded as mainland China demonstrates lower fire counts than other Asian regions with primary occurrence in spring. Natural source impacts remain minimal during summer and winter, and fire counts exhibit significant interannual decrease [52].

2.2. Models

2.2.1. WRF-CMAQ

This study utilizes the WRF-CMAQ regional chemical transport modeling system, which functions as an integrated 3-D Eulerian atmospheric chemistry and transport framework featuring a “one-atmosphere” architecture developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This configuration possesses the capability to comprehensively address complex multi-pollutant interactions and concurrent air quality challenges. The execution of CMAQ relies on meteorological inputs derived from WRF model—an advanced mesoscale numerical weather prediction platform employed for atmospheric investigations and operational meteorological forecasting applications. The simulation domain encompassed the predominant geographical extent of East Asia (Figure S1), maintaining a horizontal grid resolution of precisely 36 km by 36 km. Vertically, the CMAQ system incorporates 15 sigma-coordinate layers, utilizing a vertically compressed adaptation extracted from the WRF model’s complete 51-layer vertical structure, while preserving an identical upper boundary condition of 50 hectopascals (hPa). Gas-phase chemical processing was governed by the Carbon Bond 05 mechanism incorporating revised toluene chemistry (CB05tucl), alongside implementation of the sixth-generation aerosol module (AERO6) for particulate matter transformations [53,54].

2.2.2. Regional Multi-Air Pollutant Assimilation System (RAPAS)

The RAPAS was devised to achieve quantitative optimization of regional-scale air pollutant emissions, founded upon the integrated WRF-CMAQ modeling framework in conjunction with the three-dimensional variational (3DVAR) computational algorithm and the ensemble square root filter (EnSRF) methodology [44]. Within this architecture, dual subsystems—initial field assimilation (IA) and emission inversion (EI)—operate, respectively, to generate an idealized chemical initial condition (IC) and execute inversions of anthropogenic emissions. Employing cyclic execution, RAPAS implements a “two-step” computational approach within each EI data assimilation window. This scheme preserves mass conservation integrity between emission modifications and resultant atmospheric concentration shifts. Initially, preliminary emissions undergo optimization utilizing ground-based observational data. Subsequently, the refined emission inventory is reintroduced into the CMAQ model both to initialize the subsequent temporal window and to serve as the next window’s prior emission estimate. A “super-observation” technique is implemented to mitigate observational representativeness error impacts. Comprehensive methodological specifics are detailed by Feng et al. (2023) [55].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interannual Variations in NO2 Concentrations

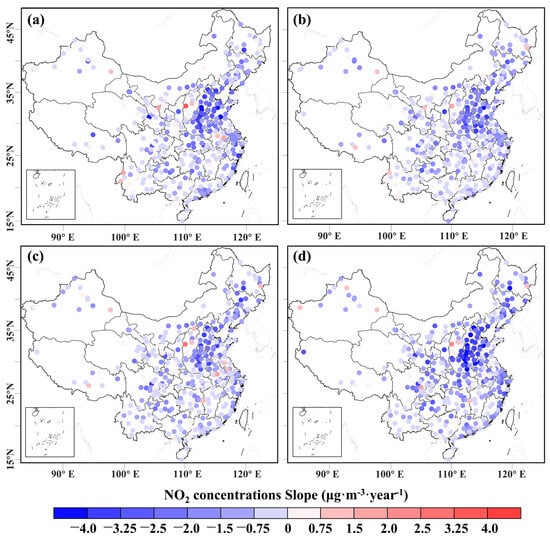

Prior to the assimilation of ground-based observational data for the inversion of anthropogenic NOx emissions, we first examine the interannual variability of NO2 concentrations. Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of annual NO2 concentration variations across spring (March to May), summer (June to August), autumn (September to November), and winter (December to the following February). The overwhelming majority of monitoring sites nationwide exhibited declining NO2 trends during 2014–2021, with particularly pronounced reductions observed in the southern of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, the western of Shandong Peninsula, and the eastern of Yangtze River Delta. Crucially, regions with higher baseline NO2 pollution experienced greater concentration declines (Figure S2), correlating with more evident decreasing trends. Analysis of multi-year spatial NO2 distributions further indicates persistently severe pollution prior to 2017, with limited overall improvement during these four years despite marginal alleviation (Figure S2); after 2017, significant mitigation emerged through declining concentrations in highly polluted areas, and by 2021, annual mean NO2 levels dropped below 35 μg/m3 in most cities.

Figure 1.

Spatial distributions of annual mean NO2 concentrations trends across prefectural cities in China during (a) spring, (b) summer, (c) autumn, and (d) winter from 2014 to 2021.

NO2 concentrations decreased more substantially during spring and winter than in summer and autumn. Seasonal differences in NO2 reduction trends were more pronounced in high-concentration areas, potentially attributable to more severe winter pollution and stricter control measures. Southern and western China showed smaller declines, with annual reductions below 0.5 μg/m3. Furthermore, a small number of cities nationwide exhibited increasing annual NO2 trends, particularly noticeable in central Shanxi and Anhui provinces, southwestern Ningxia, and southwestern Yunnan regions. Winter constitutes the season with the most severe NO2 pollution in China. TROPOMI data from January 2019 indicate NO2 column concentrations exceeding 2.0 × 1015 molec./cm2 in the eastern and southern regions of China (Figure S3). January and February typically encompass China’s Spring Festival period, and NO2 concentrations usually decrease during this holiday due to factory shutdowns; significant NO2 reductions occurred during the 2019 Spring Festival month (5 February) relative to the preceding month. In early 2020, widespread stagnation of social activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in steep NO2 concentration declines (Figure S3), with reductions reaching 60% in many large cities across mainland China [47].

3.2. Anthropogenic NOx Emission Estimates

3.2.1. Meteorology Validation

The performance of the WRF model determines the accuracy in simulating synoptic-scale NO2 variations driven by meteorological forcing. Key meteorological elements critically influence pollutant simulation outcomes through modulation of transport, boundary-layer mixing, and photochemical reaction rates. Previous studies indicate that temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed constitute established determinants of near-surface NO2 variability [56]. In this study, simulated 2 m temperature (T2), 2 m relative humidity (RH2), and 10 m wind speed (WS10) were evaluated against surface observations during the study period (Table S1). Overall, the WRF model accurately reproduced T2 and RH2 over the study domain with low biases and strong correlation coefficients (CORR). Biases for T2 and RH2 were approximately −0.9 °C and 4.2%, with CORR exceeding 0.93 and 0.84, respectively. The model slightly overestimated WS10 due to underestimated urban terrain effects and insufficient representation of spatial characteristics, consistent with prior WRF studies [57,58]. Enhanced WS10 promotes pollutant dispersion and transport, potentially reducing NO2 concentrations and partially countering biases from T2 and RH2. The WRF model demonstrates acceptable performance in reproducing core meteorological parameters. Furthermore, annual statistical results demonstrate minimal variability, confirming the model’s capability to capture interannual weather variations.

3.2.2. Evaluation of the Posterior NOx Emissions

To evaluate the overall performance of the posterior emissions (the optimized NOx emissions inferred by RAPAS), forward simulations of atmospheric pollutant concentrations using the optimized emissions were compared with ground-based observations, indirectly verifying the accuracy of the posterior emissions. This approach has been widely adopted in previous studies [59,60]. For comparison, this section also evaluates NO2 concentrations simulated using prior emissions (the NOx emissions obtained from MEIC).

- (1)

- Evaluation of Simulation Results at Assimilation Sites

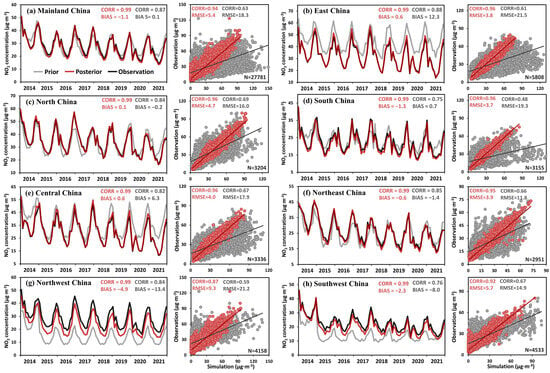

As shown in Figure 2, the simulation results captured the interannual and monthly variations in NO2 concentrations across mainland China and its subregions (depicted in Figure S1). Relative to prior emissions simulations, posterior emissions yielded reduced the mean biases (BIAS, simulated minus observed) and root mean square errors (RMSE), with consistently higher correlation coefficients (CORR) against ground observations across all regions. The concentrations simulated using posterior emissions exhibited a high degree of agreement with ground-based observations, achieving a nationwide daily average correlation of 0.94. In eastern, northern, southern, and central China, the correlations reached 0.96, while even in relatively remote western regions, the correlations were around 0.90. The posterior RMSE values for all regions were significantly lower than those from the prior results. Monthly mean NO2 concentrations simulated using posterior emissions achieved a correlation of 0.99 with ground-based observations, markedly higher than the correlation obtained using prior emissions. Additionally, the average site biases for each region were substantially reduced when using posterior emissions. These statistical analyses demonstrate that the posterior simulations effectively captured the trend characteristics of NO2 concentrations during the study period. In recent years, there has been a growing body of research using machine learning methods—an estimation approach that incorporates various parameters such as meteorological factors, satellite retrieval products, anthropogenic emissions, and socioeconomic parameters—to predict ground-level NO2 concentrations [61,62]. However, in terms of both CORR and RMSE, their performance was inferior to that of our model.

Figure 2.

Comparison of monthly (line) and daily (scatter) average NO2 concentrations between simulations and observations for Mainland China and seven geographical subdivisions from 2014 to 2021 (a–h). Simulated results were extracted based on the locations of observation sites. In the scatter plots, red and gray dots represent comparisons between ground-based observations and simulations using posterior and prior emissions, respectively. BIAS, the mean biases (simulated minus observed); RMSE, the root mean square errors; CORR, the correlation coefficients.

From the perspective of annual average concentrations (Figure S4), the observed annual mean NO2 concentration across mainland China and its seven subregions decreased by 36%, 31%, 37%, 37%, 27%, 41%, 32%, and 43%, respectively, from 2014 to 2021. Correspondingly, the simulated posterior NO2 concentrations showed reductions of 39%, 32%, 40%, 38%, 28%, 43%, 38%, and 48%. These consistent reduction ratios between observed and simulated NO2 concentrations confirm the reliability of the posterior emissions. Moreover, the increase in simulated and observed concentrations from 2014 to 2017 also showed consistent trends.

Prior and posterior simulated annual mean NO2 concentrations across China were also compared with ground-based observations during 2014–2021, yielding mean BIASs ranging from −3.6 to −0.1 μg/m3 (Figure S5). Posterior simulations accurately reproduced the spatial distribution of national NO2 concentrations across years. Prior emission simulations exhibited substantial negative biases at most sites in western China and significant positive biases in eastern regions, with the number of sites showing large positive biases increasing since 2019. Simulations using assimilated emissions reduced deviations at most stations to below 3 μg/m3; nationwide station averages exhibited biases under 3 μg/m3 in all years except 2016 and 2019, with four years recording sub −1.5 μg/m3 deviations. Regionally, posterior simulation biases post-2014 were lower than national averages in East, North, Central, South, and Northeast China (Figure 3), indicating improved consistency with surface observations. Persistent larger negative biases occurred in western China (e.g., central Xinjiang, western Qinghai, northern Tibet), likely associated with substantial prior emission discrepancies and relatively sparse observational constraints. Additionally, some stations showed larger post-assimilation deviations versus prior results (e.g., South and Northeast China during 2019–2021), suggesting possible emission over-adjustments potentially arising from conflicting regional observational biases; such contradictory adjustments compromised assimilation efficacy and amplified errors [55].

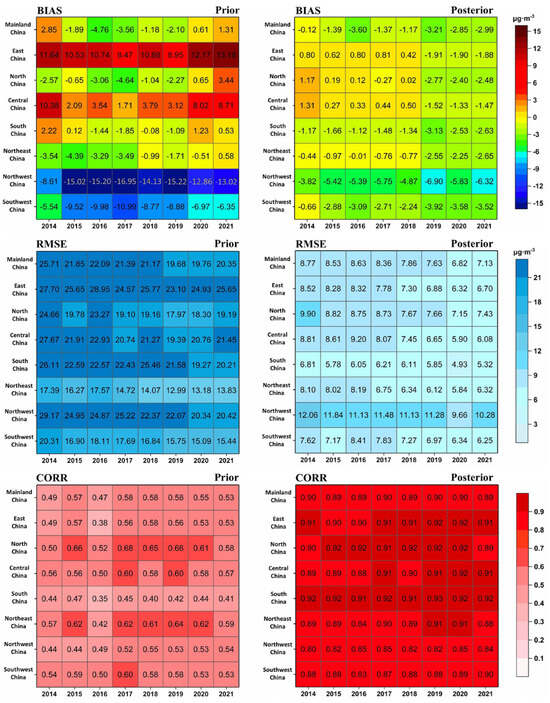

Figure 3.

Thermal maps of the biases (BIAS, simulated minus observed), root mean square errors (RMSE) and correlation coefficients (CORR) of NO2 concentration between prior and posterior simulations against ground observations during 2014–2021.

Spatial distributions of RMSE between simulated and observed NO2 concentrations during 2014–2021 using prior and assimilation-optimized emissions are displayed (Figure S6). Posterior simulations substantially reduced RMSE values, particularly across central-eastern China where most RMSE values fell below 9 μg/m3, whereas prior simulations typically exceeded 15 μg/m3 with some sites surpassing 20 μg/m3. Mainland China’s posterior simulation RMSE values ranged from 6.8 to 8.8 μg/m3 (Figure 3), representing 61–66% reductions compared to prior simulations. East, North, Central, and South China all demonstrated significantly decreased RMSE values with marked reductions versus prior simulations; Northeast China exhibited slightly higher RMSE than central-eastern regions but achieved approximately 50% RMSE reduction relative to prior results; Western China, despite larger simulation biases, also showed substantially improved RMSE versus prior outcomes.

Analysis of CORR between the annual mean NO2 concentrations of prior/posterior simulations and ground-based observations revealed that in the evaluated cities during 2014–2021, 63–74% of the NO2 simulations had a CORR exceeding 0.85 (Figure S7). Regional statistics demonstrated all-year CORR values reaching 0.9 in East, North, and South China, significantly exceeding prior simulation results; Northeast and Northwest China also exhibited substantial CORR improvements versus prior outputs, confirming posterior simulations effectively capture urban-scale NO2 variability and enhance consistency with surface observations (Figure 3).

- (2)

- Evaluation of Simulation Results at Independent Sites

Evaluation of the simulations of stations participating in assimilation inversions confirmed that optimization significantly enhances agreement between simulated NO2 concentrations and observations; however, posterior emission accuracy beyond assimilation stations requires further verification. Independent stations reserved pre-assimilation were utilized to assess simulation reliability. Statistical comparison between prior/posterior simulated NO2 concentrations and independent observations followed regional averaging (Table S2). Prior emissions showed substantial overestimations across East, North, Central, and South China but underestimations in Northeast and West China; posterior simulations demonstrated improved accuracy, with effective bias reduction in all regions except North China. Independent stations showed RMSE improvements versus prior results (Figure S8), exceeding 60% reductions in East, South, and Northeast China; posterior simulations also exhibited enhanced CORR across all regions compared to prior results, indicating consistent trends with observations.

3.3. NOx Emission Trends

3.3.1. Annual NOx Emissions During 2014–2021

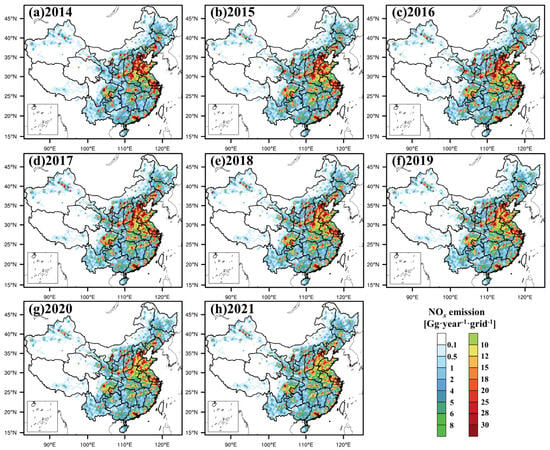

The spatial distribution NOx emissions reveals that high-emitting regions in China were predominantly located in central and eastern provinces (Figure 4). The particularly elevated levels were observed across North China, East China, South China, Central China, and CY, whereas relatively lower emissions were recorded in Northeast China and Northwest China. Nationwide NOx emissions maintained elevated levels during 2014–2017, followed by significant reductions post-2018, with particularly pronounced decreases in eastern China during 2020–2021. However, the spatial distribution pattern lacks an intuitive quantitative comparison of interannual emission variability. Interannual variations and trends of NOx emissions were thus quantified for 2014–2021 across several geographical regions.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of NOx emissions in China from 2014 to 2021 (a–h).

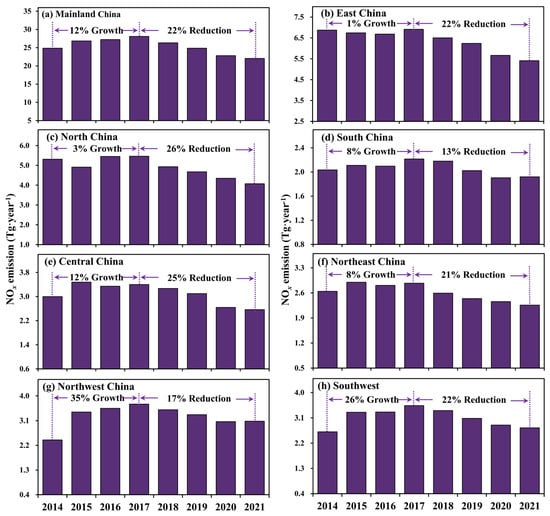

Nationally, NOx emissions exhibited an upward trend prior to 2017, succeeded by a rapid decline (Figure 5a). Consistent with this trend, NO2 concentrations rebounded in 2017, as evidenced by observed and simulated increases of 3–8% at national and regional scales from 2015 to 2017 (Figure S9). This pattern is corroborated by Kong et al. (2024) [63], who report a 5.9% increase in NOx emissions from 2015 to 2017, followed by a significant decline starting in 2018. Their study further suggests that the earlier increase may be linked to continuous growth in the number of vehicles and the limited effectiveness of NOx control measures in industrial sectors such as iron, steel, and cement. Conversely, SO2 and PM2.5 emissions underwent respective reductions of 62% and 47% between 2014 and 2021, diverging from the increase-then-decrease pattern characteristic of NOx and CO emissions (Figure S9). Aligning with these trends, research by Bo et al. (2021) [64] documented over 40% decreases in SO2 and PM2.5 emissions across China’s iron and steel production sector during 2014–2018 while reporting a 3% rise in NOx emissions.

Figure 5.

Annual total NOx emissions of mainland China and seven geographical subdivisions from 2014 to 2021 (a–h). Labels over bars depict changes ratios of NOx emissions for each region from 2014 to 2017, and from 2017 to 2021, respectively.

Regionally, NOx emissions in major geographic divisions generally increased during 2014–2017 but stabilized after 2015 with growth below 10% (Figure 5). The national total emissions increased by 12% during 2017 relative to 2014, while South China, Central China, and Northeast China showed significant increments of 8%, 12%, and 8%, respectively, during the same period. Emissions in Northwest and Southwest China increased substantially by 35% and 26% by 2017, considerably surpassing those of eastern regions. Notably, more pronounced emission growth was observed in the Northwest and Central regions, indicating that the earlier action plan had limited success in reducing NOx emissions [63,65]. From 2018 onward, emissions progressively declined across China, with all central and eastern regions except South China (13% reduction) exhibiting over 20% decreases by 2021 relative to 2017, most notably in North China (26% reduction). Correspondingly, regional annual average NO2 concentrations in 2021 decreased by approximately 4.0–10.8 μg/m3 (41–91%) compared to 2017. Regional NOx emissions reduction trends moderated between 2020 and 2021.

The interannual variation trends of NOx emissions in the five national urban agglomerations during 2014–2021 generally mirrored those of major regions, featuring an initial increase followed by reduction (Figure S10). Distinctively, the NOx emissions in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region peaked in 2016 with substantial subsequent annual declines thereafter. NOx emissions in the Yangtze River Delta and the Pearl River Delta displayed U-shaped patterns with minor initial declines preceding growth during 2014–2017, transitioning to continuous decreases post 2017, though exhibiting negligible changes in 2021 relative to 2020. NOx emissions in the Yangtze River Middle Reach and Cheng–Yu region displayed fluctuating increases from 2014 through 2017 before declining, reaching their lowest recent levels in 2020 followed by emissions rebound in 2021.

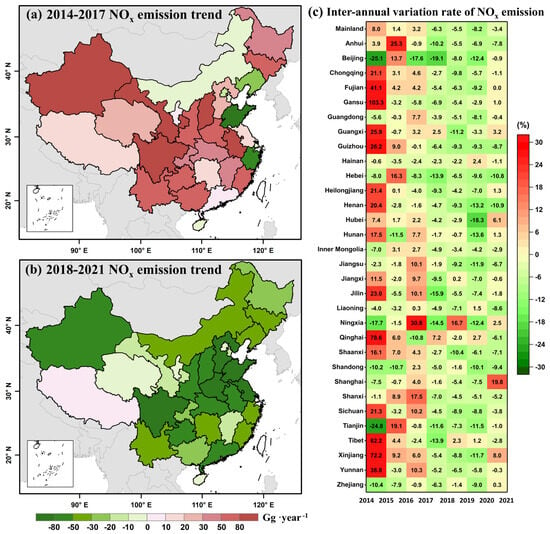

3.3.2. Provincial and Cities’ NOx Emissions Trends

A general decline in NOx emissions since 2014 was observed in over half of the provinces, including significant contributors like Hebei and Shandong (Figure S11). This contrasts with the rising trend concentrated in the northwestern and southwestern provinces, as also reflected in the marked increases in Anhui, Yunnan, Shanxi, Gansu and Xinjiang prior to 2017 (Figure 6a). Relative interannual variations between adjacent years indicate 2015 and 2017 predominantly drove the upward tendency before 2017 (Figure 6c). Conversely, Shandong and Zhejiang provinces reduced emissions exceeding 80 Gg annually, while Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Hainan, Beijing and Tianjin also declined during this phase. After 2017, emissions decreased in all provinces except Tibet and Shanghai, especially across East China, Central China and South China (Figure 6b). Minor emission increases in Tibet during 2019–2020 yielded slight overall growth for 2018–2021, partly resulting from its substantial 14% decline relative to 2017 in 2018. NOx emissions in Shanghai demonstrated consistent downward trends during 2018–2020 with adjacent-year drop rates of –1.6%, –5.4% and –7.5%, respectively, yet exhibited a 19.8% emission increase relative to 2020 in 2021.

Figure 6.

Linear trend of provincial NOx emissions in mainland China (a) from 2014 to 2017 and (b) from 2018 to 2021, and (c) relative changes in NOx emissions of each province between adjacent years during 2014–2021.

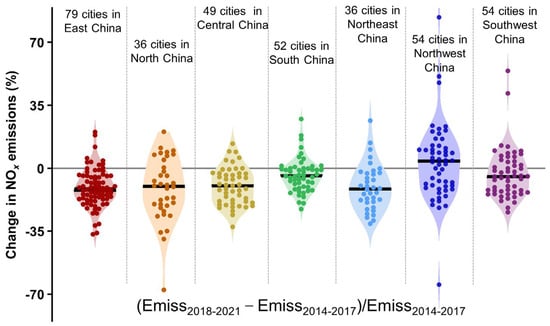

Figure 7 displays the data distribution (annual percentage) of NOx emission changes during the four-year implementation period of the Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the Blue-Sky War. The figure illustrates the rate of change for total NOx emissions in 2018–2021 relative to 2014–2017 across cities in seven regions, with black horizontal bars indicating the median emission levels for urban areas in each region. Developed regions in central and eastern China, East China, North China, South China, and Central China collectively contributed 65% of national emissions, with over 25% and 19% originating specifically from East China and North China, respectively. East China, Central China, and Northeast China contained the largest numbers of cities demonstrating reduced total emissions during 2018–2021 compared to the preceding four years, with 87%, 88% and 86% of their cities, respectively, showing declining trends. Both North China and South China also exceeded 70% of cities exhibiting emission reductions, indicating effective pollution control measures in numerous cities. Despite contributing only 25% to national emissions, western regions require strengthened mitigation efforts, particularly in Northwest China where over half of cities experienced increasing NOx emissions during the four years following 2018.

Figure 7.

Change in NO2 emissions (percent per year) in the 4 years since the implementation of the Three-Year Action Plan to Win the Battle of Blue Sky. Changes are annual total emissions during 2018–2021 compared to the period 2014–2017, and are shown for individual cities (dots) separated in seven geographical subdivisions. The median of the city’s values is shown for each region, with the plotted violins showing the distribution of the data using a kernel density estimation. Different colored dots represent cities in each region, and light colored paddings indicate the density of data distribution.

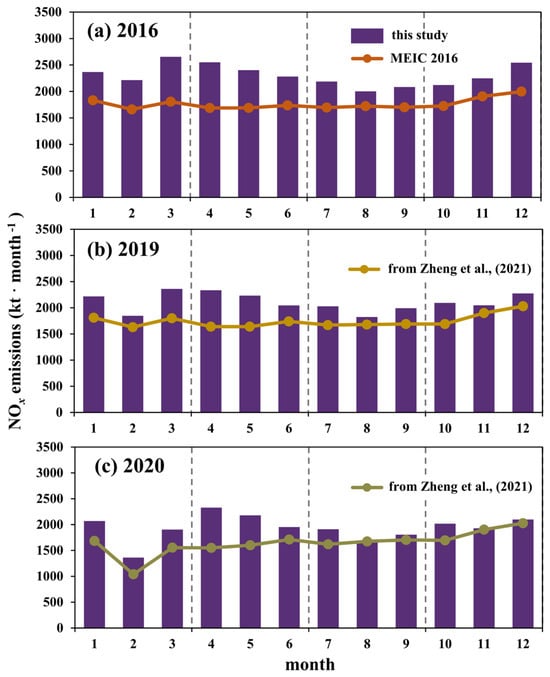

3.3.3. Comparison with the Two Existing Monthly NOx Emissions

Figure 8 displays seasonal variations in posterior NOx emissions versus the two existing emissions over mainland China in 2016, 2019, and 2020. The prior emissions for 2016 originated from the MEIC inventory, with both inversions and prior inventory showing higher emissions in March–April and lower emissions in August–September, but prior emissions exhibited underestimations that were more pronounced during high-emission months; this underestimation pattern recurred in other years (e.g., 2019–2020). Comparative emission data for 2019–2020 were derived from Zheng et al. (2021) [66], who established a near-real-time dynamic “bottom-up” methodology quantifying monthly variations in China’s air pollutant emissions. Both Zheng et al. (2021) [66] and this study indicate significantly lower NOx emissions in the first quarter of 2020 than those in the same period of 2019 due to COVID-19 containment measures, with particularly notable reductions in February 2020 when NOx emissions decreased a lot versus February 2019, respectively. Following effective pandemic control, pollutant emissions rebounded substantially after April 2020—April NOx emissions increased over 20% relative to March, reaching near-2019 levels by late 2020.

Figure 8.

Monthly NOx emissions estimated in this study, MEIC, and the study of Zheng et al., 2021 [66] in 2016, 2019, and 2020.

4. Uncertainty and Limitation

However, owing to the inherent complexity of emission estimation, our inversion results are subject to certain unavoidable limitations. The limited number of observation sites in 2014 may introduce artificial emission trends, particularly over western China. Nevertheless, this potential bias does not obscure the clear increasing trend in NOx emissions observed between 2014 and 2017. The effect of station density is less pronounced in the North China Plain and Eastern China, where the higher density of monitoring sites reduces spatial sampling uncertainty. Although the number of observation sites has remained relatively stable since 2015, their predominantly urban distribution limits the ability to fully constrain air pollutant emissions across China, especially those from natural sources. As a result, emission estimates in remote regions are associated with higher uncertainty compared to urban areas. It should be noted, however, that uncertainty in NOx emissions remains lower than that for species with substantial natural emission sources. Expanding the observational network in western China and other undersampled regions is recommended to improve the accuracy of future inversion estimates.

The inversion of NOx emissions was also sensitive to the configuration of data assimilation parameters. Specifically, background and observation errors influence the relative weighting of a priori emissions and observational data in the posterior estimates, while the localization scale governs the spatial propagation of observational information in the inversion. The errors in ground-based observational data encompass both measurement errors and representativeness errors. Measurement errors are defined with different values depending on the species; the parameters used in this study were obtained from literature review [24,67]. Representativeness errors arise from the interpolation by the observation operator and depend on model resolution and observation location. These parameter choices introduce considerable uncertainty in both the spatial distribution and magnitude of inferred NOx emissions. As described in Section 2.2.2, the “super-observation” approach adopted in this study helps reduce the impact of representativeness errors while enhancing model stability.

In addition, uncertainties in the atmospheric transport model can lead to model–data mismatches by affecting nitrogen NO2 photolysis and transport processes, thereby influencing the NOx emission estimates. In this work, larger biases were found over the whole mainland China under posterior emission simulations against prior emission simulations (Figure 2a). The model biases could originate from uncertainties in meteorological simulations such as WS10, emission characteristics including vertical profiles and biogenic emissions, boundary conditions provided by the global model, and constraints inherent in certain model treatments like cumulus parameterization and secondary organic aerosol formation [68]. However, sensitivity analyses conducted in our previous work demonstrate that emission estimates are only marginally affected by variations in assimilation parameters [69], supporting the overall robustness of the inversion methodology.

5. Conclusions

China’s sequential implementation of air pollutant abatement measures has facilitated declines in NO2 concentrations and NOx emissions. The actual abatement levels of anthropogenic NOx emissions and their interannual characteristics demand further quantification. Conventional bottom-up emission estimations exhibit substantial uncertainties, making precise NOx emission quantification essential for attributing NO2 variations and evaluating mitigation effectiveness. This study examines interannual seasonal trends in spatiotemporally distributed NO2 concentrations, while optimizing nationwide multi-year daily NOx emissions (2014–2021) through assimilation of ground-based observations by using the Regional Air Pollutant Assimilation System (RAPAS). The findings can be summarized as follows:

Regarding interannual changes in seasonal NO2 spatial distributions, most of nationwide sites demonstrated declining concentrations during 2014–2021, with steeper reductions occurring in heavily polluted areas. NO2 concentrations in winter exhibited greater annual decreasing trends than those in summer, showing amplified seasonal trend discrepancies in higher-concentration regions. In terms of NOx emission inversion, the RAPAS significantly improved modeling performance, with site-averaged biases substantially reduced versus prior estimates across all regions. RMSE values markedly decreased in East, North, Central, and South China—even in western China where modeling uncertainties were highest, RMSE remained notably superior to prior results. The posterior simulated NO2 concentrations consistently achieved CORR greater than 0.90 with ground observations in East, North and South China, significantly outperforming prior simulations. Nationwide NOx emissions across seven regions demonstrated upward trends during 2014–2017, transitioning to sustained declines post 2018. Central and East China exhibited more than 20% emission reductions relative to 2017 levels, while South China only decreased by 13%. From 2020 to 2021, regional decline rates moderated annually. Five national urban agglomerations demonstrate analogous emission trajectories: initial increases followed by reductions. At the provincial level, Anhui, Yunnan, Shanxi, Gansu and Xinjiang showed substantial NOx increases during 2014–2017, whereas Shandong and Zhejiang provinces exhibited accelerated reduction rates during this period. After 2017, nearly all provinces showed declining emissions (excluding Tibet and Shanghai), with particularly significant decreases in East, Central, and South China.

This study assimilates multi-year ground-based observations across China, with optimized emission inversions significantly enhancing model performance. However, sparse ground monitoring in western China limits precise spatiotemporal constraints. Satellite observations provide complementary atmospheric inversions due to superior spatial coverage and representativeness. Subsequent work will focus on the assimilation of multiple satellite and ground datasets to refine pollution source inventories; conduct comparative quantification of NOx emissions derived from satellite versus ground-based inversions; analyze resulting discrepancies; and evaluate enhancement potential through joint data assimilation approaches.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos17010051/s1, Figure S1: The location of seven geographical subdivisions and provinces in mainland China; Figure S2: Spatial distributions of annual average surface NO2 concentrations in China from 2014−2021; Figure S3: Spatial distribution of tropospheric NO2 VCDs from POMINO-TROPOMI satellite observations over China in January–February, 2019–2020; Figure S4: Annual average NO2 concentrations from 2014 to 2021 for Mainland China and seven geographical subdivisions, including observed values and simulated results; Figure S5: Distributions of the mean biases (BIAS, simulated minus observed) of the NO2 concentrations simulated using the posterior and prior emissions against the assimilated observations, respectively; Figure S6: Distributions of the root mean square errors (RMSE) of the NO2 concentrations simulated using the posterior and prior emissions against the assimilated observations, respectively; Figure S7: Distributions of the correlation coefficients (CORR) of the NO2 concentrations simulated using the posterior and prior emissions against the assimilated observations, respectively; Figure S8: Spatial distribution of the root mean square errors (RMSE) between NO2 concentrations simulated using a posteriori emission and independently observed concentrations from 2014 to 2021; Figure S9: Trends of anthropogenic emissions (NOx, CO, PM2.5, and SO2), annual NO2 concentration in mainland China between 2014 and 2021; Figure S10: Annual total NOx emissions of five national urban agglomerations from 2014 to 2021; Figure S11: Linear trend of provincial NOx emissions in mainland China from 2014 to 2021 and relative changes in NOx emissions of each province between adjacent years during 2014–2021; Table S1: Evaluation for meteorological parameters simulated by the WRF model from 2014 to 2021; Table S2: Comparison of NO2 concentration between simulations simulated by prior and posterior emissions against independent observations during 2014–2021.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., S.F. and Y.Y.; methodology, Y.S. and S.F.; software, S.F. and Y.Y.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, Y.S., G.W. and S.F.; investigation, Y.S. and Z.Y.; resources, Y.Y., Z.Y. and C.P.; data curation, Y.S. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S. and S.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.S., S.F. and G.W.; visualization, Y.S. and Z.Y.; supervision, Y.S. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42305116 and 42304033; and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, grant number BK20241092 and BK20230801.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The ground-based real-time NO2 concentration data are from https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/ (accessed on 9 December 2025). NCEP FNL datasets can be downloaded from http://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds083.2/ (accessed on 9 December 2025). The ground station meteorological observation data can be downloaded from ftp://ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/noaa/isd-lite/ (accessed on 9 December 2025). Anthropogenic emissions were obtained from http://meicmodel.org/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the High Performance Computing Center (HPCC) of Nanjing University for the numerical calculations in this paper by its blade cluster system.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Velders, G.J.M.; Granier, C.; Portmann, R.W.; Pfeilsticker, K.; Wenig, M.; Wagner, T.; Platt, U.; Richter, A.; Burrows, J.P. Global tropospheric NO2 column distributions: Comparing three-dimensional model calculations with GOME measurements. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2001, 106, 12643–12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Klimont, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Martin, R.V.; Zheng, B.; Heyes, C.; Cofala, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, K. Comparison and evaluation of anthropogenic emissions of SO2 and NOx over China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 3433–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, T.; Meng, X.; Xie, S.; Yu, H. Driving factors of the significant increase in surface ozone in the Yangtze River Delta, China, during 2013–2017. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Dentener, F.J.; Peters, W.; Krol, M.C. On the role of hydroxyl radicals in the self-cleansing capacity of the troposphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2004, 591, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustini, A.; Rapp, R.; Forastiere, F. Nitrogen dioxide and mortality: Review and meta-analysis of long-term studies. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Gao, Y.; Xu, J.; Cui, L.; Wang, G. Impact of clean air policy on criteria air pollutants and health risks across China during 2013–2021. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD038939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wan, W.; Liu, J.; Xue, T.; Gong, J.; Zhang, S. Insights into the new WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines. Chinese Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. A conversation on air pollution in China. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 939–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, A.C.; Wright, R.O.; Schwartz, J.; Coull, B.A.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Tellez-Rojo, M.M.; Moody, E.; Wang, Y.; Lyapustin, A.; Kloog, I. Using high-resolution satellite aerosol optical depth to estimate daily PM2.5 geographical distribution in Mexico City. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 8576–8584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tang, H.; Zhao, H. Diurnal, weekly and monthly spatial variations of air pollutants and air quality of Beijing. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 119, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunova, I.; Baumelt, V.; Modlik, M. Long-term trends in nitrogen oxides at different types of monitoring stations in the Czech Republic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, C.M.; Constantin, D.E.; Voiculescu, M.; Georgescu, L.P.; Merlaud, A.; Roozendael, M.V. Modeling results of atmospheric dispersion of NO2 in an urban area using METI–LIS and comparison with coincident mobile DOAS measurements. Atmospheric Pollut. Res. 2015, 6, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasha, H.; Ghaffarpasand, O.; Pope, F.D. Air pollution and economic growth in Dubai a fast-growing Middle Eastern city. Atmos. Environ. X 2024, 21, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Jiang, F.; Feng, S.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, Z.; Lyu, X. Impact of weather and emission changes on NO2 concentrations in China during 2014−2019. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Jiang, F.; Feng, S.; Xia, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lyu, X.; Zhang, L.; Lou, C. Increased diurnal difference of NO2 concentrations and its impact on recent ozone pollution in eastern China in summer. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Meng, H.; Tan, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, F. Impacts of the Chengdu 2021 world university games on NO2 pollution: Implications for urban vehicle electrification promotion. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Cui, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, A.; Fu, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Kong, L.; Chen, J. Spatial and temporal variation of particulate matter and gaseous pollutants in China during 2014-2016. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 161, 235e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Eskes, H.; Sudo, K.; Takigawa, M.; Kanaya, Y. A comparison of the impact of TROPOMI and OMI tropospheric NO2 on global chemical data assimilation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 1703–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streets, D.G.; Bond, T.C.; Carmichael, G.R.; Fernandes, S.D.; Fu, Q.; He, D.K.Z.; Nelson, S.M.; Tsai, N.Y.; Wang, M.Q.; Woo, J.H.; et al. An inventory of gaseous and primary aerosol emissions in Asia in the year 2000. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, 8809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Streets, D.G.; Carmichael, G.R.; He, K.B.; Huo, H.; Kannari, A.; Klimont, Z.; Park, I.S.; Reddy, S.; Fu, J.S. Asian emissions in 2006 for the NASA INTEX-B mission. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 5131–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, P.; Ma, J.Z.; Zhu, S.; Pozzer, A.; Li, W. A high-resolution emission inventory of primary pollutants for the Huabei region, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDuffie, E.E.; Smith, S.J.; O’Rourke, P.; Tibrewal, K.; Venkataraman, C.; Marais, E.A.; Zheng, B.; Crippa, M.; Brauer, M.; Martin, R.V. A global anthropogenic emission inventory of atmospheric pollutants from sector- and fuel-specific sources (1970–2017): An application of the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2020, 12, 3413–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Aardenne, J.V. Impact of different emission inventories on simulated tropospheric ozone over China: A regional chemical transport model evaluation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2004, 4, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, Z.; Ban, J.; Chen, M. The 2015 and 2016 wintertime air pollution in China: SO2 emission changes derived from a WRF-Chem/EnKF coupled data assimilation system. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 8619–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Cheng, Y.; Goto, D.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Shi, G.; Nakajima, T. Revealing the sulfur dioxide emission reductions in China by assimilating surface observations in WRF-Chem. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 4357–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Niu, T.; Wang, T.; Ma, C.; Li, M.; Li, R.; Wu, H.; Qu, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, X. 3DVar sectoral emission inversion based on source apportionment and machine learning. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopacz, M.; Jacob, D.J.; Henze, D.K.; Heald, C.L.; Streets, D.G.; Zhang, Q. Comparison of adjoint and analytical Bayesian inversion methods for constraining Asian sources of carbon monoxide using satellite (MOPITT) measurements of CO columns. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2009, 114, D4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jones, D.B.A.; Kopacz, M.; Liu, J.; Henze, D.K.; Heald, C. Quantifying the impact of model errors on top-down estimates of carbon monoxide emissions using satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2011, 116, D15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, J.A.; Martin, R.V. Global deposition of total reactive nitrogen oxides from 1996 to 2014 constrained with satellite observations of NO2 columns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 10071–10091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhao, J.; Li, R.; Tian, Y. Retrieval and evaluation of NOx emissions based on a machine learning model in Shandong. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.T.; McElroy, M.B.; Boersma, K.F. Constraint of anthropogenic NOx emissions in China from different sectors: A new methodology using multiple satellite retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.T.; McElroy, M.B. Detection from space of a reduction in anthropogenic emissions of nitrogen oxides during the Chinese economic downturn. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 8171–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Yan, J.; Zhang, H.; Guan, Q.; Rao, S.; Jiang, C.; Duan, Z. Analysis of synergistic drivers of CO2 and NOx emissions from thermal power generating units in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region, 2010–2020. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.V. Global inventory of nitrogen oxide emissions constrained by space-based observations of NO2 columns. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2003, 108, D17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Miyazaki, K.; van der A, R.J.; Mijling, B.; Kurokawa, J.I.; Cho, S.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, F.; Levelt, P.F. Intercomparison of NOx emission inventories over East Asia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 10125–10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, K.; Eskes, H.J.; Sudo, K. Global NOx emission estimates derived from an assimilation of OMI tropospheric NO2 columns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 2263–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; van der A, R.; van Weele, M.; Eskes, H.; Lu, X.; Veefkind, P.; de Laat, J.; Kong, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; et al. A new divergence method to quantify methane emissions using observations of Sentinel-5P TROPOMI. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL094151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.R.; Sun, K. Nitrogen oxides emissions from selected cities in North America, Europe, and East Asia observed by the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 8727–8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditi, K.; Pandey, A.; Banerjee, T. Forest fire emission estimates over South Asia using Suomi-NPP VIIRS-based thermal anomalies and emission inventory. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, K.; Eskes, H.J.; Sudo, K. A tropospheric chemistry reanalysis for the years 2005–2012 based on an assimilation of OMI, MLS, TES, and MOPITT satellite data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 8315–8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.D.; Christensen, J.H.; Kahnert, M.; Robertson, L.; Rayner, P.J.; Brandt, J. Multi-species chemical data assimilation with the Danish Eulerian hemispheric model: System description and verification. J. Atmos. Chem. 2016, 73, 261–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Worden, J.R.; Worden, H.; Deeter, M.; Jones, D.B.A.; Arellano, A.F.; Henze, D.K. A 15-year record of CO emissions constrained by MOPITT CO observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 4565–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.X.; Wei, Z.; Strow, L.L.; Barnet, C.D.; Sparling, L.C.; Diskin, G.; Sachse, G. Improved agreement of AIRS tropospheric carbon monoxide products with other EOS sensors using optimal estimation retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 9521–9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeter, M.N.; Edwards, D.P.; Gille, J.C.; Worden, H.M. Information content of MOPITT CO profile retrievals: Temporal and geographical variability. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2015, 120, 12723–12738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Ju, W.; Wang, H. CO emissions inferred from surface CO observations over China in December 2013 and 2017. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD031808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Jiang, F.; Evangeliou, N.; Eckhardt, S.; Huang, X.; Ding, A.; Stohl, A. Rapid decline of carbon monoxide emissions in the Fenwei Plain in China during the three-year Action Plan on defending the blue sky. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 337, 117735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Jiang, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Ju, W.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Ding, A. NOx emission changes over China during the COVID-19 epidemic inferred from surface NO2 observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL090080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Evangeliou, N.; Eckhardt, S.; Huang, X.; Gao, J.; Ding, A.; Stohl, A. Black Carbon Emission Reduction Due to COVID-19 Lockdown in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL093243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlea, E.J.; Herndon, S.C.; Nelson, D.D.; Volkamer, R.M.; San Martini, F.; Sheehy, P.M.; Zahniser, M.S.; Shorter, J.H.; Wormhoudt, J.C.; Lamb, B.K.; et al. Evaluation of nitrogen dioxide chemiluminescence monitors in a polluted urban environment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 2691–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Kurokawa, J.; Woo, J.; He, K.; Lu, Z.; Ohara, T.; Song, Y.; Streets, D.G.; Carmichael, G.R.; et al. MIX: A mosaic Asian anthropogenic emission inventory under the international collaboration framework of the MICS-Asia and HTAP. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 935–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, A.B.; Jiang, X.; Heald, C.L.; Sakulyanontvittaya, T.; Duhl, T. The model of emissions of gases and aerosols from nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): An extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012, 5, 1471–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Meng, L.; Li, Y.C.; Liu, Y. Satellite-Observed variations and trends in carbon monoxide over Asia and their sensitivities to biomass burning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, G.; Simon, H.; Bhave, P.; Yarwood, G. Examining the impact of heterogeneous nitryl chloride production on air quality across the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 6455–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, K.W.; Pouliot, G.A.; Simon, H.; Sarwar, G.; Pye, H.O.T.; Napelenok, S.L.; Akhtar, F.; Roselle, S.J. Evaluation of dust and trace metal estimates from the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model version 5.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2013, 6, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; He, W.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Lou, C.; Jiang, Z.; et al. A Regional multi-Air Pollutant Assimilation System (RAPAS v1.0) for emission estimates: System development and application. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 5949–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkey, M.; Holloway, T.; Oberman, J.; Scotty, E. An evaluation of CMAQ NO2 using observed chemistry-meteorology correlations. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 2015, 120, 11775–711797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Liu, Q.; Huang, X.; Wang, T.; Zhuang, B.; Xie, M. Regional modeling of secondary organic aerosol over China using WRF/Chem. J. Aerosol Sci. 2012, 43, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Ying, Q.; Zhang, H. One-year simulation of ozone and particulate matter in China using WRF/CMAQ modeling system. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 10333–10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, H.M.; Chen, J.M.; Machida, T.; Zhou, L.X.; Ju, W.M.; Matsueda, H.; Sawa, Y. Carbon balance of China constrained by CONTRAIL aircraft CO2 measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 10133–10144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Lin, H.X.; Heemink, A.; Segers, A. Spatially varying parameter estimation for dust emissions using reduced-tangent-linearization 4DVar. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 187, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Luo, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, M.; Grieneisen, M.L.; Di, B. Satellite-based estimates of daily NO2 exposure in China using Hybrid Random Forest and Spatiotemporal Kriging Model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 4180–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Liao, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Tu, Y.; Huang, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, B.; Tan, J.; Deng, Z.; et al. Estimates of daily ground-level NO2 concentrations in China based on Random Forest model integrated K-means. Advances in Applied Energy 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Tang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Wang, W.; et al. Changes in air pollutant emissions in China during two clean-air action periods derived from the newly developed Inversed Emission Inventory for Chinese Air Quality (CAQIEI). Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2024, 16, 4351–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X.; Jia, M.; Xue, X.; Tang, L.; Mi, Z.; Wang, S.; Cui, W.; Chang, X.; Ruan, J.; Dong, G.; et al. Effect of strengthened standards on Chinese ironmaking and steelmaking emissions. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tian, W.; Chen, D. Impacts of thermal power industry emissions on air quality in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, G.; Chen, C.; Shi, Q.; Cui, M.; Lei, Y.; He, K. Changes in China’s anthropogenic emissions and air quality during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 2895–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Jiang, F.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, L. Impact of 3DVAR assimilation of surface PM2.5 observations on PM2.5 forecasts over China during wintertime. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 187, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Tong, D.; He, K. Multi-year downscaling application of two-way coupled WRF v3.4 and CMAQ v5.0.2 over east Asia for regional climate and air quality modeling: Model evaluation and aerosol direct effects. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 2447–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Jiang, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; He, W.; Wang, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, M.; Ju, W.; et al. China’s fossil fuel CO2 emissions estimated using surface observations of coemitted NO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 8299–8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.