Abstract

With the continuous rise in global plastic production and emissions, microplastics (MPs) have become ubiquitous across environmental compartments, including the atmosphere. Aging in natural settings substantially alters MP physicochemical properties and, in turn, their interactions with coexisting contaminants. Here, polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polystyrene (PS) were subjected to ultraviolet (UV)-accelerated aging and natural exposure in marine intertidal zones, freshwater lakes, and the atmosphere, and changes in their properties and tetracycline (TC) adsorption were systematically compared. Aging intensity followed the order seawater > freshwater > air. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy showed the formation and enrichment of oxygen-containing functional groups, and naturally aged samples exhibited stronger oxidation signatures than those aged solely under UV irradiation. Adsorption kinetics indicated higher equilibrium capacities and rate constants for aged MPs; after 324 h of UV exposure in seawater, TC adsorption on PE, PS, and PET increased by 64.6%, 56.6%, and 64.0%, respectively. Mechanistic analysis suggests that surface roughening, oxygenated functional groups, and enhanced negative surface charge collectively promote TC adsorption, dominated by electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding. These findings not only elucidate how different aging pathways modulate the interactions between MPs and pollutants but also offer new insights into assessing the carrier potential of microplastics in environments such as the atmosphere and their adsorption of other contaminants.

1. Introduction

Plastics, widely used as essential materials for more than 120 years, have experienced a dramatic surge in production and disposal in recent decades. Approximately 52.1 Mt of macroplastic waste is discharged into the environment each year [1,2], making plastic contamination one of the most pressing environmental challenges of the present era [3]. Plastic debris accumulates across virtually all known natural habitats [4,5,6] and a substantial portion of global plastic production ultimately reaches the oceans through riverine transport, atmospheric deposition, and improper waste dumping [7], atmospheric deposition [8] and improper waste dumping [9]. Once exposed to sunlight, mechanical abrasion, and microbial activity, plastics undergo continuous environmental aging, progressively fragmenting into microplastics (MPs, <5 mm) [8,10,11,12]. MPs can be transported over long distances through atmospheric and oceanic circulation and redistributed among marine, terrestrial, and atmospheric compartments, even reaching remote regions with minimal local plastic sources [13,14,15,16]. During transport, MPs inevitably experience combined effects of irradiation, oxidation, mechanical disturbance, and biotic interactions, causing significant alterations in their physicochemical properties. Aging commonly modifies the surface morphology, functional group composition, crystallinity, and surface charge of MPs. Chromophoric and unsaturated groups within polymer matrices absorb ultraviolet (UV) radiation and trigger reactions such as dehydrogenation, oxidation, and chain scission, leading to the formation of carbonyls, hydroxyls, and other oxygen-containing functional groups [17]. Long polymer chains may further break down under reactive oxygen species (ROS) [18], profoundly influencing the interactions between MPs and coexisting contaminants, such as tetracycline (TC)—a widely used antibiotic frequently detected in aquatic environments.

The TC is the second most extensively used antibiotic worldwide [19], with 50–80% of the applied amount released into the environment in its original form [20]. As a representative emerging contaminant, TC is characterized by widespread occurrence and notable ecological risks [21]. MPs may act as carriers for antibiotics, and their interactions can result in the formation of combined pollutant complexes [22]. Potential adsorption mechanisms include electrostatic attraction, van der Waals forces, π–π interactions, and pore filling, all of which are strongly dependent on the aging state of the MPs [23]. Therefore, understanding MP aging processes and their influence on adsorption behavior is critical for evaluating pollutant fate in the environment.

Although research on MP aging has expanded rapidly, laboratory-based aging experiments—particularly UV irradiation—still dominate current approaches. While such methods offer controllability and shorter aging durations, they often lack environmental relevance. Laboratory simulations cannot fully replicate fluctuations in natural irradiance, spectral characteristics, diurnal temperature changes, wet–dry cycles, salinity variations, hydrodynamic forces, sediment abrasion, or microbial colonization. Moreover, laboratory aging typically emphasizes a single process (e.g., photo-oxidation or chemical oxidation), whereas natural aging involves long-term, gradual, and multi-factor coupled mechanisms. Consequently, laboratory studies may underestimate or misrepresent the rate and extent of natural aging, limiting their usefulness for accurately predicting the environmental behavior of aged MPs.

A key gap in MP aging studies is the lack of quantitative benchmarking of laboratory UV-accelerated aging against environmentally realistic aging across different media. Moreover, many studies rely on standardized polymers or environmental fragments alone, limiting the comparability of mechanistic interpretations to real-world relevance. To address this, we provide a coordinated cross-media assessment by pairing laboratory UVA-340 aging in seawater, freshwater, and air with parallel natural exposure in marine intertidal, freshwater lake, and atmospheric settings. This study uses representative consumer-plastic fragments and compares their physicochemical aging signatures with those of commercial PE/PS/PET materials.

Based on this framework, we hypothesize that (i) aging induces systematic changes in surface chemistry and interfacial properties (e.g., oxidation degree, roughness, and surface charge), and (ii) these changes enhance tetracycline adsorption by strengthening electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding, thereby increasing the carrier potential of aged MPs. We test these hypotheses by quantifying aging-induced physicochemical shifts across both laboratory and field scenarios, and by evaluating tetracycline adsorption kinetics and mechanisms using the laboratory-aged MPs under controlled aqueous conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

The MPs used in this study consisted of both commercial polymer pellets and fragments derived from real-world plastic products. Standard PS and PET pellets were purchased from Dongguan Ruixiang Plastic Co., Ltd. (Dongguan, China) and PE pellets were obtained from Dongguan Yineng Plastic Materials Co., Ltd. (Dongguan, China) all with an average particle size of approximately 100 μm. In addition, commonly used plastic consumer items were selected to represent environmentally relevant MPs, including commercial PET drinking-water bottles, PS foam boxes, and PE plastic bags. To ensure experimental consistency, PET bottles and PE bags were cut into square pieces (1 cm × 1 cm), while PS foam boxes were trimmed into cubic blocks (1 cm3).

All samples underwent systematic pretreatment to remove surface contaminants and potential additive interference. Specifically, samples were washed in 0.1 mol/L HNO3 under continuous stirring for 24 h to eliminate adsorbed organic residues and inorganic salts. They were then repeatedly rinsed with ultrapure water until neutral pH was achieved, followed by drying in a forced-air oven at 45 °C. After drying, samples were sealed and stored in the dark prior to aging and adsorption experiments. The target contaminant, TC, was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) with a purity of ≥98%, meeting analytical-grade requirements. Artificial seawater was prepared according to ASTM D1141 [24], while freshwater conditions were simulated using freshly prepared ultrapure water. All aqueous solutions were prepared immediately before use to ensure chemical stability.

2.2. Aging Experiments

Accelerated UV aging was employed to simulate photo degradation processes occurring in natural environments. Samples were placed in a custom-built UV aging chamber equipped with a UVA-340 lamp (peak wavelength: 340 nm; Q-Lab Corporation, Westlake, OH, USA), with the vertical distance between the lamp and the sample surface strictly maintained at 10 cm. Three aging environments were established: artificial seawater (prepared following ASTM D1141), ultrapure water (representing freshwater conditions), and a water-free system (representing atmospheric exposure). All experiments were conducted under controlled temperature conditions of (25 ± 2) °C, with aging durations of 108 h, 216 h, and 324 h. To ensure homogeneous exposure, samples were gently stirred every 4 h throughout the aging process. For samples immersed in aqueous media, the corresponding solution was periodically replenished to maintain a constant liquid level and ensure complete submersion. All procedures were performed under dark conditions to avoid interference from unintended light sources. For laboratory UV aging experiments, six independent replicates of each standard pellet type were prepared for each aging condition for separate aging treatment and subsequent analysis.

To investigate environmentally realistic aging processes, field exposure experiments were conducted in representative natural settings. The Beiyuedi intertidal zone (Zhanjiang, China) was selected as the marine environment, Butterfly Lake (Zhanjiang, China) as the freshwater environment, and the rooftop of the Third Experimental Building (Zhanjiang, China) as the atmospheric environment. Three types of real-world PE samples were enclosed in custom-made wire cages (mesh size < 1 cm) and deployed in the respective environments for natural aging. Sampling was conducted at three time points: 1 month, 2 months, and 3 months. To promote uniform weathering, samples were manually turned once per week, and environmental parameters—including temperature, humidity, and solar irradiance—were regularly recorded. After each exposure period, samples were retrieved and ultrasonically cleaned with ultrapure water for 5 min to remove loosely adhered particles, dried to constant weight at 45 °C, and stored in sealed, light-protected containers for subsequent analyses. For natural environment exposure, three independent replicates of each real-world plastic sample were deployed at each field site to account for environmental heterogeneity. To characterize the distinct aging conditions, the key environmental parameters monitored during the exposure period are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key environmental parameters at the natural exposure sites.

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization

A suite of analytical techniques was employed to comprehensively characterize the physicochemical properties of MPs subjected to different aging conditions, including surface morphology, functional group evolution, structural changes, and surface electrostatic properties. All instruments were operated following standard procedures to ensure data accuracy and reproducibility. Surface morphology was first examined using an SDPTOP SZ-series optical microscope (Sunny Optical Technology Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China). A high-resolution CCD imaging system was used to document color changes, crack development, and surface roughening of MPs. All micrographs were acquired at a consistent magnification of 100× to ensure comparability among treatments. Chemical structure analysis was conducted using a Nicolet IN10 microscopic Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Spectra were collected over a range of 4000–500 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 64 scans per measurement. Multiple locations were randomly selected on each sample to obtain representative spectra, with particular attention paid to variations in oxygen-containing functional groups such as carbonyls and hydroxyls. To quantify oxidation in a comparable manner, FTIR indices were calculated using band-area (integrated absorbance) ratios after converting transmittance to absorbance (A = log10(100/T)). For PS and PE, the carbonyl index (CI) was defined as the integrated area of 1680–1760 cm−1 normalized to a reference band (PS: 1450–1520 cm−1; PE: 1420–1480 cm−1), and the hydroxyl index (HI) was defined as 3200–3600 cm−1 normalized to the same reference band. For PET, HI was used as the primary oxidation-related index because the ester carbonyl band is intrinsic to the polymer.

To complement FTIR analysis, a portable SR-510 Pro Raman spectrometer (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA) was used to examine structural changes in PE, PS, and PET before and after aging. The instrument was operated at an excitation wavelength of 785 nm, laser power of 40 mW, and an integration time of 10 s. Raman spectra were collected at three positions on each particle (center and two edges), and the resulting spectra were compared with reference spectra of pristine materials. Surface electrostatic properties were determined using a Mastersizer 2000 laser particle analyzer (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK) equipped with a Zeta potential measurement module. Measurements were performed in buffer solutions spanning pH 3–10. Prior to analysis, samples were dispersed at 25 °C and 180 rpm for 3 h to ensure homogenization. Triplicate measurements and corresponding blanks were included for each sample group. Tetracycline (TC) concentrations were quantified using a U-3900H UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at a detection wavelength of 358 nm. Calibration was performed using a standard curve with an R2 greater than 0.999 to ensure quantification accuracy. Aging experiments were conducted using a SCIENTZ-06 UV accelerated aging chamber (Ningbo Xinzhi Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China) and an HZQ-QX constant-temperature shaker (Harbin Donglian Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Harbin, China). Additional supporting equipment included a Milli-Q ultrapure water system, an ME204E analytical balance (METTLER TOLEDO, Greifensee, Switzerland), and an S210-K pH meter (METTLER TOLEDO, Greifensee, Switzerland), together forming an integrated physicochemical characterization platform. All spectroscopic and surface potential analyses were performed with at least triplicate measurements on independently aged samples to ensure data reliability.

2.4. Adsorption Kinetics

Tetracycline (TC) stock solutions with two initial concentrations (10 mg/L and 15 mg/L) were prepared as the target adsorbates. A total of 0.05 g of MPs—either pristine or aged under various conditions—was accurately weighed and transferred into 30 mL amber glass vials, followed by the addition of 10 mL of TC solution. The vials were placed on a thermostatic shaker and subjected to kinetic adsorption experiments at 25 °C and 180 rpm. At thirteen predetermined time intervals (0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480, 720 min), 3 mL aliquots were withdrawn and immediately passed through 0.45 μm microporous membrane filters. The filtrates were collected in amber sampling vials, and the residual TC concentrations were quantified using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer at the characteristic wavelength of 358 nm. All experiments were performed in triplicate, with a corresponding blank control (without MPs) included to eliminate background interference. The adsorption kinetics were modeled using the pseudo–first-order kinetic equation, as widely applied in previous studies [25,26]:

where qt and qe (mg·g−1) denote the adsorption capacities at time t and at equilibrium, respectively, and k1 (h−1) represents the pseudo–first-order rate constant. Adsorption kinetic experiments were conducted in triplicate, with background correction using blanks containing no MPs. The reported data represent the mean values from three independent runs.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Changes in Mps

Morphological alteration is a key indicator of MPs aging and provides fundamental evidence for assessing their degradation extent. UV irradiation can induce free-radical reactions along polymer chains, and photo-oxidation is widely recognized as the dominant driver of MP degradation. The susceptibility of MPs to chemical weathering is closely associated with their molecular structure and composition. In general, MPs contain aromatic groups that substitute the aliphatic hydrocarbon backbone; these aromatic moieties strongly absorb UV radiation, rendering the polymers particularly vulnerable to photodegradation and leading to rapid deterioration of their physicochemical properties.

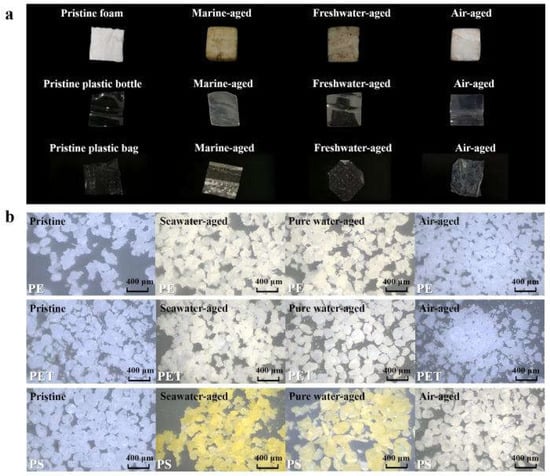

Figure 1 presents the macroscopic and microscopic morphologies of pristine MPs and those subjected to different aging treatments. The surfaces of pristine MPs were smooth with well-defined edges, whereas both laboratory-aged and environmentally aged MPs exhibited varying degrees of yellowing, surface roughening, micro-cracks, pores, and edge rounding—typical hallmarks of polymer weathering. Under natural environmental exposure, the pristine foam particles and PET bottle fragments initially displayed smooth surfaces and regular edges (Figure 1a). However, after exposure to different field environments, characteristic aging-related morphological changes emerged rapidly. Samples from the marine tidal zone exhibited the most pronounced weathering features, although the changes in PET bottle fragments were less distinct than those in PS foam, likely due to differences in polymer type, additives, or manufacturing processes. Repeated wet–dry cycles, salt crystallization, particle abrasion, and hydrodynamic scouring in the intertidal environment led to the development of flake-like exfoliation, groove-shaped depressions, and irregular cracks, resulting in significantly increased surface roughness. These observations align well with recent studies on the weathering of marine MPs. For instance, elevated salinity combined with hydrodynamic disturbance was reported to weaken the integrity of polymer surfaces and accelerate embrittlement and fragmentation. In freshwater environments, surface alterations were comparatively moderate, although fine cracks, localized whitening, and the adhesion of suspended particles or biofilms were still evident [27,28]. The abundance of suspended solids, natural organic matter, and microbial communities in freshwater likely promoted localized erosion and fouling. In contrast, MPs exposed to air primarily experienced physical abrasion. Long-term exposure to wind, sunlight, and diurnal temperature fluctuations caused noticeable shrinkage of foam materials, edge rounding, and homogeneous abrasion marks, reflecting dominant mechanical weathering and light-induced surface embrittlement in this dry environment.

Figure 1.

Characterization of pristine and aged MPs under natural and laboratory conditions. (a) Macroscopic appearance of real-world PS foam, PET bottle fragments and PE plastic bag samples in pristine form and after 3 months of natural aging in marine, freshwater and atmospheric environments. (b) Optical microscopy images of standard PE, PET and PS particles before aging and after 324 h of UV aging in simulated seawater, pure water and air environments.

Morphological responses under laboratory UV aging are shown in Figure 1b. Among the three polymers, PS exhibited the most significant discoloration, shifting from white to yellow or pale yellow, especially under seawater and air conditions. This yellowing is attributable to the formation of oxygen-containing chromophoric groups due to chain scission and oxidation, a conclusion further validated by subsequent FTIR analysis. In contrast, color changes in PE and PET were minimal, with only slight yellowing observed in aqueous environments. Yellowing of MPs often results from the formation of polyene structures during aging; when the conjugated chain length exceeds eight C=C–C units, absorption shifts into the visible spectrum, imparting a yellow appearance. This color change not only serves as a visual indicator of chemical aging but may also influence the environmental behavior and even climatic impacts of MPs. Revell et al. [29] was the first to simulate the direct radiative forcing of atmospheric MPs, showing that photo-aged MPs with enhanced visible-light absorption may exert a positive radiative effect. Given the accelerating rates of global warming and plastic production, understanding the optical evolution of aged MPs is critical for evaluating their potential climatic implications. Comparing morphologies before and after aging, pristine pellets originally exhibited smooth and dispersed granular forms, but aged MPs became rough, aggregated, brittle, and prone to fragmentation. Notably, small salt crystals were observed on aged MPs from seawater conditions, suggesting that salt crystallization occurs during marine degradation and may further influence MP fragmentation and contaminant adsorption. Similar observations have been reported in marine MP weathering studies [30].

3.2. Changes in FTIR Spectra

The FTIR is a classical technique for characterizing the molecular structure and chemical composition of polymers, and it is widely used to reveal the chemical evolution of MPs under environmental stress. The spectra of all samples used in this study, including standard PS, PET and PE pellets as well as real PS foam, PET bottle fragments and PE plastic bags, were mainly distributed in the range of 4000 to 800 cm−1. By comparing spectra at different aging stages, the micro-scale structural changes induced by light exposure, salinity, hydrodynamic conditions and natural weathering can be systematically captured.

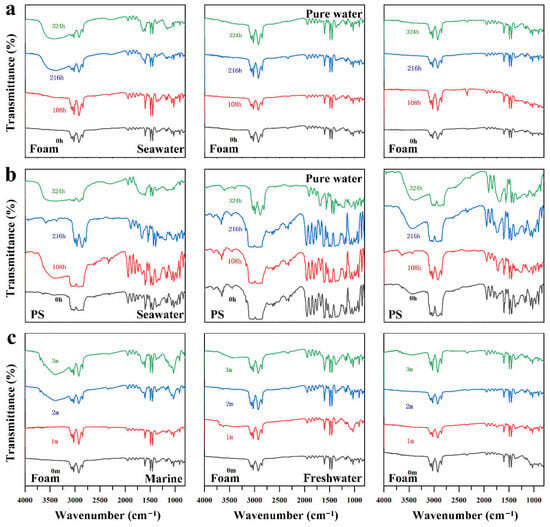

Focusing first on the foam samples, Figure 2 presents the FTIR features of PS foam naturally aged for four months and standard PS pellets subjected to 324 h of laboratory UV aging in seawater, pure water and air environments. The FTIR spectra of PET and PE provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1 and S2) further illustrate the chemical changes of these polymers under different aging conditions. Both sample types exhibited a general enhancement of oxygen-containing functional groups, although the magnitude and evolution pathways differed significantly. For PS foam, clear oxidation signals appeared under both laboratory-simulated and natural aging conditions. The naturally aged samples showed the most notable increases in the carbonyl region near 1700 cm−1 and the hydroxyl region near 3500 cm−1, together with a raised spectral baseline. These features indicate that their surface chemistry was jointly affected by multiple environmental factors including sunlight, salinity, hydrodynamic disturbance, sediment deposition, organic matter and biofilm attachment. In comparison, standard PS pellets also showed gradual enhancement of carbonyl and hydroxyl bands during 108 to 324 h of UV irradiation, although the increase in peak intensity was more moderate. This indicates that artificial UV aging mainly reflects a single photo-oxidation process without the combined effects of physical weathering and biological activity that occur in natural environments.

Figure 2.

Fourier transform infrared spectra of PS MPs and foam samples under different aging conditions. (a) FTIR spectra of standard PS after UV aging in simulated seawater, pure water and air in the laboratory. (b) FTIR spectra of foam samples after UV aging in simulated seawater, pure water and air in the laboratory. (c) FTIR spectra of foam samples after natural aging in marine intertidal, freshwater lake and atmospheric environments.

Compared with PS, PE displayed milder infrared changes yet still showed typical characteristics of photo-oxidation. With increasing aging time, the C-H stretching bands at 2915 and 2848 cm−1 gradually weakened, and a weak carbonyl band appeared near 1700 cm−1, suggesting chain scission and formation of oxygen-containing structures. Among these, the baseline shift was more pronounced in naturally aged PE samples, suggesting that light exposure, wet dry cycling and external contaminants jointly contributed to its chemical aging. In contrast to PS and PE, PET and its corresponding bottle fragments showed the weakest spectral changes. Under both simulated and natural environments, neither carbonyl nor hydroxyl signals showed a clear increase, and the ester characteristic peaks remained stable. This reflects the strong photostability of PET’s aromatic backbone and ester bonds, combined with the presence of UV absorbers and antioxidants in commercial products, resulting in only slight oxidation under natural exposure.

Overall, the three polymers showed a clear gradient in their FTIR responses to aging. PS was most sensitive to light and environmental factors, PE followed, while PET remained structurally stable and exhibited the lowest degree of oxidation. The accumulation of oxygen-containing groups is a key indicator of polymer aging because it represents chain scission, rearrangement and oxidative modification. These changes directly influence surface polarity, charge distribution and the adsorption performance of MPs.

Artificial UV aging reveals the structural changes dominated by photo-oxidation, while natural environments involve multiple interacting factors including light exposure, salinity, organic deposition, biofilm formation and wet dry cycling. As a result, natural aging often produces faster, more complex and more irregular chemical evolution. By comparing FTIR spectra of the same real plastic samples aged indoors and under natural marine, freshwater and atmospheric conditions, it was found that the degree of aging was consistently higher in natural environments. This is likely because tidal environments introduce not only high salinity but also additional physical abrasion from waves and microbial degradation, which together accelerate aging. Compared with pure water, freshwater contains more impurities and complex chemical components and hosts microbial degradation, leading to increased aging. For samples exposed to an outdoor air environment, weather-related factors such as wind, sunlight and rainfall enhanced physical aging relative to controlled indoor air exposure.

Overall, the degree of plastic aging depends strongly on the surrounding environment, and physical weathering together with biological degradation significantly accelerate the process. These findings show that the chemical aging of MPs is not only related to the intrinsic polymer structure but is also strongly affected by the environmental medium, the exposure pathway and the timescale. The continuous accumulation of carbonyl and hydroxyl groups is the core chemical signature of aging and represents ongoing chain scission, rearrangement and oxidative modification. These structural changes directly affect surface polarity, hydrophilicity, charge distribution and the subsequent adsorption behavior of the materials. The chemical fingerprint characteristics formed through different aging pathways also reveal the actual evolution of MPs in the environment and provide an important basis for subsequent studies on adsorption behavior, environmental transport and ecological risk. Consistent with the qualitative FTIR changes, the calculated indices increased after 324 h UV aging in seawater. For PS, the CI rose from 0.35 to 1.33, and the hydroxyl index (HI) increased from 1.01 to 13.14. For PE, CI increased from 0.13 to 1.08, and HI increased from 0.45 to 9.02. For PET, HI increased from 3.13 to 4.97.

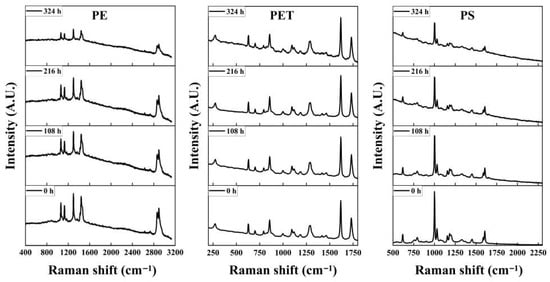

3.3. Changes in Raman Spectra

Raman spectra of PS, PET and PE particles aged under UV irradiation in three different environments were systematically analyzed. As shown in Figure 3 and further supported by the Raman spectra provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S3 and S4), none of the three materials exhibited new characteristic peaks after aging, although their characteristic peak intensities showed a slight decrease following UV exposure. This observation is consistent with the findings of Lenz, who reported that the characteristic peaks of PE and PP decreased slightly after 1634 h of simulated sunlight exposure in air [31]. In addition, Raman spectroscopy has been widely used for the qualitative identification of MPs. Compared with infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy has advantages in detecting small-sized plastic particles larger than one micrometer [32]. However, Raman spectroscopy is less sensitive to the oxygen-containing functional groups formed during the aging process. In practical applications, some inorganic additives incorporated during plastic manufacturing may interfere with the Raman detection of plastics, which introduces limitations to Raman-based identification, especially in the analysis of aged plastics. Compared with Raman spectroscopy, FTIR can directly reveal the functional groups of polymers. In this study, the formation of polar oxidative functional groups such as hydroxyl and carbonyl groups can be clearly observed in FTIR spectra, while these changes cannot be detected using Raman spectra. Therefore, FTIR can readily identify whether plastic particles have undergone chemical weathering in the environment, whereas Raman spectroscopy cannot. However, for plastics that have experienced high levels of chemical weathering, the presence of multiple newly formed oxidative functional groups may complicate identification. This indicates that identification methods for environmental MPs need improvement, since both FTIR and Raman techniques have inherent limitations.

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of PE, PET and PS microplastic particles aged in seawater before and after UV irradiation at 0 h, 108 h, 216 h and 324 h.

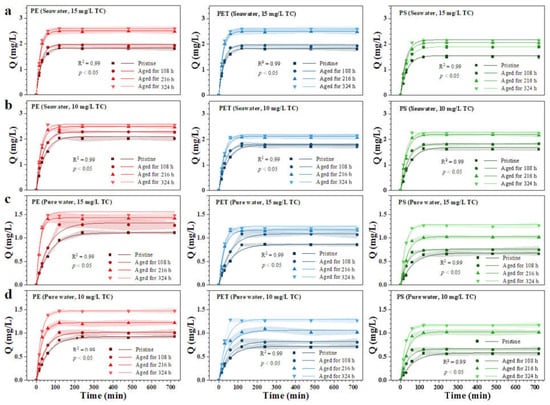

3.4. Adsorption Kinetics of Aged MPs Toward Tetracycline

The aging process markedly alters the surface morphology, chemical composition and abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups on MPs, and these structural changes indicate that their interfacial interactions with pollutants will be significantly modified. To further verify the functional consequences of aging under environmentally relevant conditions, the TC was selected as the target contaminant to investigate the adsorption kinetics of different types of MPs before and after aging. All MPs from different materials and environmental conditions showed a typical two-stage adsorption pattern, characterized by rapid initial uptake followed by a gradual stabilization phase, consistent with previous studies (Figure 4) [33]. The pseudo first order kinetic model fitted the experimental data well and quantitatively reflected the changes in adsorption behavior induced by aging. Compared with pristine MPs, aged MPs exhibited significant increases in both the equilibrium adsorption capacity and the adsorption rate constant. Taking PE as an example, PE showed a rapid increase in adsorption within 240 min in both seawater and freshwater, followed by a plateau. However, aged PE reached equilibrium more quickly and achieved a higher adsorption capacity. In seawater, PE aged for 324 h reached an adsorption capacity of 2.556 mg/L in a 10 mg/L TC solution, while the freshwater-aged sample showed an adsorption capacity of 1.462 mg/L. After 324 h of UV aging in seawater, the maximum enhancement in TC adsorption for PE, PS and PET reached 64.6%, 56.6% and 64.0%, respectively. In freshwater environments, the corresponding maximum increases were 52.4%, 61.4% and 83.3%.

Figure 4.

Adsorption kinetics of tetracycline on pristine and aged MPs in different aqueous media. (a) 10 mg/L TC adsorption in seawater; (b) 15 mg/L TC adsorption in seawater; (c) 10 mg/L TC adsorption in pure water; (d) 15 mg/L TC adsorption in pure water.

These results indicate that the aging environment plays a key role in regulating adsorption behavior. The observed changes may be attributed to the roughened surface of aged MPs and the increased number of oxygen-containing functional groups. In addition, the aging process alters surface chemical properties. UV irradiation and chemical aging induce chain scission and oxidation, causing MPs to transition from highly ordered long polymer chains to more disordered short chains, which enhances the adsorption of tetracycline [34]. The stronger adsorption capacity observed in seawater aged samples may result from several factors reported in the literature [35,36]. First, the high ionic strength of seawater compresses the electric double layer and reduces electrostatic repulsion between charged species, allowing tetracycline to approach the surface more easily. Second, the salting out effect reduces the activity of tetracycline molecules in seawater, promoting their enrichment onto the solid phase. Third, the more abundant organic matter and biological residues in seawater may attach to the surface of MPs, forming composite surface films that alter surface charge properties and increase potential binding sites. Natural organic matter components such as humic substances can also interact with polymer matrices/surfaces (e.g., via hydrogen bonding and complexation), thereby modifying physicochemical properties and potentially contributing to the formation of organic coatings in environmental aging scenarios [37]. These combined effects indicate that seawater not only accelerates the oxidation of MPs but also enhances their adsorption behavior. Among the three materials, PET showed the highest overall adsorption capacity, which may be related to its higher crystallinity and the presence of polar ester groups in its molecular structure that interact more readily with tetracycline.

Overall, aging significantly enhances the adsorption capacity of MPs toward tetracycline by altering their surface morphology, chemical composition and structural order, while environmental conditions further regulate the degree of this change. High salinity, high ionic strength and complex organic matter in seawater collectively result in higher adsorption efficiency for aged MPs. Meanwhile, the intrinsic properties of each polymer determine their distinct sensitivities during the aging and adsorption processes. The adsorption kinetics results reflect the multifaceted characteristics of MP aging and provide important insights into their environmental transport and potential to act as carriers of pollutants.

3.5. Adsorption Mechanism

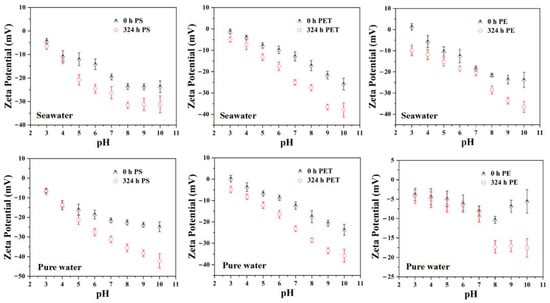

To further understand how aging affects the adsorption behavior of MPs, Zeta potential measurements were used to examine the changes in surface electrochemical properties during aging and their regulatory role in the adsorption of tetracycline. As shown in Figure 5, the three types of MPs exhibited higher negative charge levels across the entire pH range below the isoelectric point after UV aging, and their Zeta potentials shifted toward more negative values with increasing pH. The enhanced surface negativity caused by aging provides an important basis for charge regulated adsorption between MPs and pollutants. Both pristine and aged MPs were negatively charged under the same pH conditions, yet aged PE exhibited a clearly stronger negative charge. This indicates that the oxidation process induced by UV irradiation generated more deprotonatable oxygen-containing functional groups on its surface, and the surface negative charge accumulated further with prolonged aging. This result is consistent with the findings of Liu and co-workers, who reported that PS and PVC exposed to UV irradiation exhibited more negative surface charge compared with their pristine forms [38].

Figure 5.

Zeta potentials of pristine and aged MPs as a function of pH in seawater and freshwater.

The ionization behavior of tetracycline further amplifies the contribution of surface charge changes to adsorption. Tetracycline is an amphoteric molecule that exists in positively charged, neutral or negatively charged forms at different pH levels. Under near neutral aqueous conditions, aged MPs usually carry a relatively high negative charge, while tetracycline primarily occurs in neutral or partially protonated positive forms, which greatly promotes its electrostatic adsorption. Therefore, electrostatic attraction becomes an important mechanism driving the enrichment of tetracycline on the surface of aged MPs. This charge complementarity explains the accelerated adsorption rate and the significant increase in equilibrium adsorption capacity observed for aged samples. Notably, the aging-driven shift toward more negative zeta potentials is consistent with the kinetic enhancement quantified in Section 3.4. Across polymers and aging durations, samples exhibiting more negative ζ potentials under near-neutral conditions also showed higher pseudo-first-order rate constants and larger equilibrium uptake, indicating that charge regulation contributes not only to adsorption capacity but also to adsorption kinetics. In parallel, the FTIR-derived oxidation metrics increased with aging and co-varied with adsorption enhancement, supporting that oxygenation and charge evolution jointly control TC uptake across aging scenarios. It also suggests that MPs may become more effective pollutant carriers in natural environments as a result of aging. It is worth noting that compared with systems dominated by electrostatic repulsion, adsorption of tetracycline is more favorable under conditions where opposite charges coexist. The accumulation of surface negative charge during aging effectively broadens the pH range in which tetracycline can be adsorbed by MPs, thereby increasing the likelihood of MP mediated transport in aquatic systems. Overall, the changes in Zeta potential reflect the restructuring of surface chemistry during MP aging and play a central role in regulating adsorption mechanisms. These changes represent one of the important driving forces behind the enhanced adsorption performance of aged MPs.

The comprehensive analysis of multiple characterization results and adsorption experiments indicates that the enhanced adsorption capacity of aged MPs toward tetracycline arises from the combined action of several physicochemical mechanisms. First, photo-oxidative degradation induced by UV irradiation causes physical erosion on the MP surface, producing microcracks and pits. These changes effectively increase the specific surface area and provide additional physical sites for pollutant adsorption. Second, and most importantly, aging introduces abundant oxygen-containing functional groups such as carbonyl and hydroxyl groups onto the MP surface. These functional groups can act as hydrogen bond donors or acceptors and form strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds with amino, amide and phenolic hydroxyl groups present in tetracycline, thereby greatly enhancing specific interfacial interactions. Third, changes in surface charge play an important role. The generally stronger negative surface charge observed on aged MPs enables effective electrostatic attraction with the positively charged species of tetracycline under near neutral aqueous conditions. In addition, the aging process may induce chain scission, crosslinking and microstructural changes in crystallinity, which may influence the non-specific partitioning of hydrophobic organic contaminants into the MP matrix. Taken together, the increased surface roughness, the introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups, the shift in surface charge and the potential changes in polymer structure collectively form a multi mechanism cooperative framework that explains the enhanced adsorption of tetracycline by aged MPs.

4. Perspectives and Limitations

4.1. Environmental Implications and Applied Perspectives

The aging processes of MPs and their enhanced adsorption of antibiotics, as detailed in this study, have significant implications for environmental engineering and risk management. The observed increases in surface oxidation, roughness, and negative charge of aged MPs suggest that they may evolve into more effective sorbents for tetracycline under environmental conditions. In aquatic environments where MPs and antibiotics commonly coexist, aged MPs may facilitate the transfer of antibiotics from the dissolved phase to the particulate phase, impacting removal efficiencies, sludge partitioning, and downstream transport, particularly when focusing only on aqueous concentrations. Aging-induced changes in MPs’ surface properties are expected to affect the performance of separation processes like coagulation-filtration and membrane treatments by modifying aggregation behavior and particle-surface interactions, which can influence capture efficiency and fouling propensity. These findings underscore the importance of considering not just MP abundance and polymer type, but also “aging state” proxies, such as oxidation signatures and surface electrokinetic trends, when evaluating co-pollution risks in impacted environments.

Beyond aquatic settings, atmospheric transport plays a key role in the long-range dispersal of MPs. Real-world atmospheric conditions typically feature short residence times (from days to about a week) and exposure under low-humidity, intermittently wet environments. This limits oxidation during airborne transport relative to aquatic weathering. However, photo-oxidation and dry-wet cycling still promote surface embrittlement and yellowing, linked to chromophoric oxidation products. Airborne MPs also undergo coagulation with mineral dust, soot, black carbon, and organic coatings, altering their effective surface area and deposition pathways. Although the radiative impacts of these changes are beyond the scope of this study, the aging and aggregation processes may modify the optical properties of MPs, influencing their interactions with solar radiation. These aged particles can subsequently enter receiving waters and soils, where their surface transformations may enhance their potential to transport coexisting contaminants.

In conclusion, the aging processes of MPs in both aquatic and atmospheric environments can significantly influence their interactions with pollutants, and understanding these processes is crucial for improving environmental risk assessments and remediation strategies. Future research should focus on developing aging simulation systems that better replicate natural conditions and on investigating the long-term environmental and biological impacts of aged MP-contaminant complexes.

4.2. Limitations and Uncertainties

Natural aging is inherently influenced by multiple co-varying and partially uncontrollable factors. While key site parameters were monitored and summarized, several factors that could modulate the apparent intensity of aging were not directly quantified in this study, such as microbial abundance, community dynamics, biofilm development, and site-specific hydrodynamic or wave exposure. These factors may contribute to variability in surface conditioning and oxidation rates, which could partially explain the observed between-site variability. Additionally, a significant limitation of our field experiments is that smaller, micron-sized MPs were often not recoverable due to their size, making it challenging to fully assess the aging effects on the entire particle size range. To minimize such uncertainties, we standardized deployment and handling protocols across sites (e.g., identical cage configuration, exposure duration, and retrieval/cleaning procedures) and used independent replicates to account for environmental heterogeneity. Importantly, the main conclusions of the study are supported by consistent trends across multiple independent lines of evidence (e.g., morphology, spectroscopic oxidation signatures, zeta potential shifts, and adsorption kinetics), indicating that the overall cross-environment comparison and the observed aging-enhanced tetracycline uptake are robust. However, our field exposure was limited to a three-month summer period, so extrapolating these findings to other seasons, longer aging times, or more dynamic coastal conditions should be performed with caution. Future research that integrates continuous irradiance monitoring, microbial/biofilm characterization, and hydrodynamic metrics would further refine the attribution of the dominant drivers behind natural aging.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the aging processes of three typical MPs under both indoor simulated conditions and multiple natural environments, including seawater, freshwater and air, and examined how these aging pathways influence the adsorption behavior of tetracycline. The results showed that MPs underwent significant photo-oxidative aging in all three environments, and the degree of aging was strongly regulated by environmental characteristics. Aging was most pronounced in seawater, followed by freshwater and air. The aging process essentially reflected the evolution of chemical structure, accompanied by the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups such as carbonyl and hydroxyl groups, the roughening of surface physical structures and the enhancement of surface negative charge. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy proved to be an effective tool for monitoring these chemical changes. In contrast, Raman spectra showed no obvious changes in the chemical structure of weathered plastic particles compared with pristine materials across different environments, although the intensities of characteristic peaks varied after UV exposure. In addition, aging significantly enhanced the adsorption capacity and adsorption rate of all three MPs toward tetracycline, and the magnitude of this enhancement was positively correlated with the extent of aging. The adsorption behavior conformed to the pseudo first order kinetic model, and the strengthened adsorption mechanisms mainly resulted from the combined effects of increased surface area, hydrogen bonding interactions, electrostatic attraction and polymer structural changes that occurred during aging. Therefore, environmental risk assessment of MPs must fully consider their aging behavior under real environmental conditions and the differences among plastic types and environmental media. Future research should aim to develop aging simulation systems that better represent natural conditions and further elucidate the ultimate environmental fate and biological effects of aged MP–pollutant complexes. Given the growing recognition of airborne MPs as an emerging component of atmospheric particulate matter, the findings of this study also provide important implications for understanding the chemical evolution of MPs in the air and their potential impacts on air quality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos17010032/s1, Figure S1. Fourier transform infrared spectra of PET microplastics and foam samples under different aging conditions. Figure S2. Fourier transform infrared spectra of PE microplastics and plastic bag samples under different aging conditions. Figure S3. Raman spectra of PE, PET and PS microplastic particles aged in pure water before and after UV irradiation at 0 h, 108 h, 216 h and 324 h. Figure S4. Raman spectra of PE, PET and PS microplastic particles aged in air before and after UV irradiation at 0 h, 108 h, 216 h and 324 h.

Author Contributions

Y.W.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft. Q.M.: writing. Q.A.: methodology. H.F.: conceptualization, supervision, resources, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22576035).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, H.F., upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zaaba, N.F.; Jaafar, M. A review on degradation mechanisms of polylactic acid: Hydrolytic, photodegradative, microbial, and enzymatic degradation. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 2061–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottom, J.W.; Cook, E.; Velis, C.A. A local-to-global emissions inventory of macroplastic pollution. Nature 2024, 628, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M.; Arp, H.P.H.; Tekman, M.B.; Jahnke, A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science 2021, 373, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Collard, F.; Fabres, J.; Gabrielsen, G.W.; Provencher, J.F.; Rochman, C.M.; van Sebille, E. Plastic pollution in the Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.; Scoto, F.; Hallanger, I.G.; Larose, C.; Gallet, J.C.; Spolaor, A.; Bravo, B.; Barbante, C.; Gambaro, A.; Corami, F. Characteristics and quantification of small microplastics (<100 µm) in seasonal Svalbard snow on glaciers and lands. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeken, I.; Primpke, S.; Beyer, B.; Gütermann, J.; Katlein, C.; Krumpen, T.; Bergmann, M.; Hehemann, L.; Gerdts, G. Arctic sea ice is an important temporal sink and means of transport for microplastic. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, L.J.; van Emmerik, T.; van der Ent, R.; Schmidt, C.; Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eaaz5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeliou, N.; Grythe, H.; Klimont, Z.; Heyes, C.; Eckhardt, S.; Lopez-Aparicio, S.; Stohl, A. Atmospheric transport is a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Kriwoken, L.; Wilcox, C. Differentiating littering, urban runoff and marine transport as sources of marine debris in coastal and estuarine environments. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, X. Microplastics are everywhere, but are they harmful? Nature 2021, 593, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochman, C.M. Microplastics research—From sink to source. Science 2018, 360, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Halle, A.; Ladirat, L.; Martignac, M.; Mingotaud, A.F.; Boyron, O.; Perez, E. To what extent are microplastics from the open ocean weathered? Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahney, J.; Hallerud, M.; Heim, E.; Hahnenberger, M.; Sukumaran, S. Plastic rain in protected areas of the United States. Science 2020, 368, 1257–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Jiménez, P.D.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefánsson, H.; Peternell, M.; Konrad-Schmolke, M.; Hannesdóttir, H.; Ásbjörnsson, E.J.; Sturkell, E. Microplastics in glaciers: First results from the Vatnajokull ice cap. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Haider, A.; Ahmad, H.M.; Mohyuddin, A.; Aslam, H.M.U.; Nadeem, S.; Javed, M.; Othman, M.H.D.; Goh, H.H.; Chew, K.W. Source, occurrence, distribution, fate, and implications of microplastic pollutants in freshwater on environment: A critical review and way forward. Chemosphere 2023, 325, 138367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.S.; Farner Budarz, J.; Hernandez, L.M.; Tufenkji, N. Microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments: Aggregation, deposition, and enhanced contaminant transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1704–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, C.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Guo, X.; Jia, H. Inorganic anions influenced the photoaging kinetics and mechanism of polystyrene microplastic under simulated sunlight: Role of reactive radical species. Water Res. 2022, 216, 118294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Si, G.; Zhang, P.; Li, B.; Su, R.; Gao, X. Efficient removal of tetracycline-Cu complexes from water by electrocoagulation technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Sun, Y.; Gong, B. Removal of tetracycline from aqueous solution by MCM-41-zeolite A loaded nano zero valent iron: Synthesis, characteristic, adsorption performance and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 339, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, M.J.; Ansari, A.J.; Hai, F.I. Antibiotic sorption onto microplastics in water: A critical review of the factors, mechanisms and implications. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Guo, M.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, X. Adsorption of antibiotics on different microplastics (MPs): Behavior and mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 161022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zheng, S.; Chen, X.; Lu, D.; Zeng, Z. Alkaline aging significantly affects Mn(II) adsorption capacity of polypropylene microplastics in water environments: Critical roles of natural organic matter and colloidal particles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1141-98; Standard Practice for Preparation of Substitute Ocean Water. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Wang, C.; Fan, X.; Wang, P.; Hou, J.; Ao, Y.; Miao, L. Adsorption behavior of lead on aquatic sediments contaminated with cerium dioxide nanoparticles. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Gan, R.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y.; Xu, D.; Xiang, Y.; Su, J.; Teng, Z.; Hou, J. Adsorption and desorption behaviors of antibiotics by tire wear particles and polyethylene microplastics with or without aging processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.J.; Bolan, N.; Li, Y.; Ding, S.; Atugoda, T.; Vithanage, M.; Sarkar, B.; Tsang, D.C.; Kirkham, M. Weathering of microplastics and interaction with other coexisting constituents in terrestrial and aquatic environments. Water Res. 2021, 196, 117011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, C.; Sathish, C.I.; Lakshmi, D.; O’Connor, W.; Palanisami, T. An advanced analytical approach to assess the long-term degradation of microplastics in the marine environment. npj Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, L.E.; Kuma, P.; Le Ru, E.C.; Somerville, W.R.C.; Gaw, S. Direct radiative effects of airborne microplastics. Nature 2021, 598, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Wu, Z.; Tan, X. Observation of the degradation of three types of plastic pellets exposed to UV irradiation in three different environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, R.; Enders, K.; Stedmon, C.A.; Mackenzie, D.M.; Nielsen, T.G. A critical assessment of visual identification of marine microplastic using Raman spectroscopy for analysis improvement. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.F.; Ma, M.L.; Ge, Q.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Machine learning advancements and strategies in microplastic and nanoplastic detection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 8885–8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Qiu, C.; Song, Y.; Bian, S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Fang, C. Adsorption of tetracycline and Cd(II) on polystyrene and polyethylene terephthalate microplastics with ultraviolet and hydrogen peroxide aging treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, K.; Barrios, A.C.; Rajwade, K.; Kumar, A.; Oswald, J.; Apul, O.G.; Perreault, F. Aging of microplastics increases their adsorption affinity towards organic contaminants. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kharraf, A.; Rabiller-Baudry, M.; Del Real, A.P.; Sandt, C.; Bihannic, I.; Wiesner, M.; Bavay, D.; Tabuteau, H.; Khatib, I.; Pattier, M.; et al. UV aging induces colloidal-like behavior in microplastics, mediating contaminant fluxes across interfaces. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 500, 140501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wang, L.; Lang, D.; Qian, Q.; Wang, W.; Wu, R.; Wang, J. UV and chemical aging alter the adsorption behavior of microplastics for tetracycline. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, V.; Miroshnichenko, D.; Vytrykush, N.; Pyshyev, S.; Masikevych, A.; Filenko, O.; Tsereniuk, O.; Lysenko, L. Novel biodegradable polymers modified by humic acids. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 313, 128778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, P.; Qu, G.; Jing, J.; Zhang, T.; Shi, H.; Zhao, Y. Insight into the characteristics and sorption behaviors of aged polystyrene microplastics through three type of accelerated oxidation processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.