Abstract

Indoor air quality (IAQ) in high-rise residential buildings is an increasing concern, especially in hot and humid climates where prolonged indoor exposure elevates health risks. This study evaluates the performance of Fresh Air Handling Units (FAHUs) using two complementary approaches: (1) real-time sensor data to quantify IAQ conditions and (2) occupant survey responses to capture perceived comfort and pollution indicators. The results show that floor level did not predict satisfaction, even though AQI data revealed clear differences between flats, suggesting perceptions are driven more by sensory cues than by actual pollutant levels. Longer weekday exposure emerged as a stronger predictor of dissatisfaction. These gaps between perceived and measured IAQ highlight the need for improved ventilation scheduling and greater occupant awareness. FAHUs were found to be inefficient, consuming 21–26% of total building energy while lacking pollutant-specific monitoring capabilities. To address these issues, the study recommends the integration of IoT-enabled sensors for real-time pollutant detection, enhanced facade sealing to minimize external infiltration, and the upgrade of filtration systems with HEPA filters and UV purification. Additionally, AI-driven predictive maintenance and automated ventilation optimization through Building Management Systems (BMS) are suggested. These findings offer valuable insights for improving IAQ management in high-rise buildings, with future research focusing on AI-based predictive modeling for dynamic air quality control.

1. Introduction

Indoor air quality (IAQ) in high-rise residential buildings has emerged as a critical concern amid accelerating urbanization and population growth. As cities expand vertically, especially in rapidly developing regions, the design and performance of ventilation systems in tall structures demand close scrutiny. With individuals spending approximately 90% of their time indoors, IAQ plays a pivotal role in determining health, comfort, and overall well-being [1]. Numerous studies have shown that indoor pollutant concentrations frequently exceed those found outdoors, even in heavily industrialized environments [2]. This concern is particularly acute in Gulf countries, where extreme climatic conditions lead residents to remain indoors for extended periods, thereby increasing exposure to indoor pollutants.

Research conducted in hot–humid climates has consistently shown that ventilation mode, humidity control, and building design significantly affect IAQ performance. Sekhar and Goh (2011) [3] found that naturally or mechanically ventilated bedrooms provided better sleeping environments than fully air-conditioned (AC) ones, largely because AC spaces tended to accumulate elevated CO22 levels during sleep. In non-residential environments, studies in tropical settings have also shown pronounced IAQ variability driven by spatial heterogeneity and occupancy. A multi-zone investigation in a Malaysian hypermarket revealed critical discomfort and pollutant accumulation in high-activity zones such as cafeterias, while other areas achieved near-optimal IEQ metrics [4]. Similarly, seasonal assessments in Nigerian government office buildings demonstrated that dry-season pollutant concentrations (CO, CO22, PM2.5, TVOC) were substantially higher than rainy-season levels, with architectural features such as casement windows significantly improving IAQ outcomes [5].

Residential towers present unique IAQ management challenges due to structural constraints, high occupancy densities, and the complexity of mechanical ventilation. Hernandez et al. [6] found that increased occupancy in mechanically ventilated buildings correlates with elevated indoor concentrations of particulate matter, Particulate Matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm (PM2.5) and Particulate Matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 10 μm (PM10), underscoring the need for adaptive ventilation strategies. Similarly, Jung and Awad Jung and Awad [7] identified significant levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and radon in Dubai’s residential buildings, primarily linked to construction materials and internal sources. Studies also show that advanced ventilation technologies may enhance IAQ in challenging climates. In Singapore, integrating under-floor air distribution (UFAD) with personalized ventilation (PV) improved perceived air quality and resolved local thermal discomfort by delivering fresh outdoor air directly to the breathing zone [8]. Further analysis demonstrated substantial energy savings (up to 42% at part-load) and enhanced thermal comfort in tropical environments [9]. These findings highlight the potential for targeted, occupant-centered systems in high-density urban residences where IAQ and energy efficiency must be jointly optimized.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further emphasized the importance of IAQ. Lockdowns and the widespread adoption of remote work and online learning transformed residential spaces into multifunctional environments, increasing exposure to indoor pollutants and heightening concerns about their effects on health, productivity, and cognitive performance. The World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the concept of Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) in 1983 to describe symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, respiratory issues, and skin irritation associated with poor IAQ [10]. Moreover, exposure to airborne pollutants such as PM2.5 and CO2 has been shown to impair cognitive function; a study by Künn et al. [11] involving chess players demonstrated that decision-making performance declined in environments with compromised air quality, a finding likely relevant to residents working or studying from home under similar conditions.

The global proliferation of high-rise structures adds further urgency to indoor air quality management. According to the [12], 2270 buildings worldwide exceed 200 m in height, with 232 classified as super-tall at over 300 m. In dense urban settings such as Dubai, where vertical residential living is increasingly common, designing effective ventilation systems is essential for maintaining healthy indoor environments. Tham [13] notes that indoor air quality in high-rise buildings is affected by external pollution, internal emission sources, and the configuration and control of ventilation systems. For example, a 2023 study of Dubai’s Sobha Creek Vistas Tower A found that the use of total heat exchangers significantly enhanced indoor air quality by reducing concentrations of formaldehyde and toluene under varying air exchange rates [14].

Indoor pollutants originate from both external sources, introduced via ventilation systems, and internal activities such as cooking, smoking, and consumer product use. A systematic review of 141 IAQ studies across 29 countries revealed wide variations in indoor pollutant levels driven by source intensity, environmental conditions, and occupant behavior [15]. Outdoor air quality also plays a critical role, particularly in hot, arid environments where natural ventilation is limited and desert dust events are frequent.

Dubai’s regulatory framework reflects a growing recognition of indoor air quality challenges. The Dubai Building Code and Al Sa’fat Dubai Green Building Regulations require high-rise buildings to maintain a positive pressure differential, supply treated outdoor air for at least 95% of the year, and comply with specified thermal comfort parameters [16]. Internationally, standards such as ASHRAE 62.1 CO22 buildupCO22 buildup [17] provide several ventilation design methodologies, including the Ventilation Rate Procedure, the Indoor Air Quality Procedure, and the Natural Ventilation Procedure. Although the Ventilation Rate Procedure is widely used, it often emphasizes the quantity of supplied air rather than targeted pollutant reduction.

In practice, Fresh Air Handling Units (FAHUs) serve as the primary mechanical systems introducing and conditioning outdoor air in high-rise buildings. These systems filter, cool, and dehumidify incoming air to ensure acceptable IAQ levels. However, FAHUs consume substantial energy due to high airflow requirements and large enthalpy differences; cooling alone accounts for 25–30% of total building energy use in Dubai. Mechanical challenges such as leakage in heat recovery units may also compromise IAQ, potentially permitting cross-contamination. Research in hot–humid climates further shows that inadequate dehumidification, often caused by oversized cooling coils operating at reduced flow rates, can degrade both thermal comfort and IAQ [18]. Additionally, studies in schools within humid tropical regions reveal strong interactions between occupancy, ventilation availability, and CO22 buildup [19], highlighting the universal complexity of IAQ control in dense indoor environments.

This study examines the performance of Fresh Air Handling Unit (FAHU) systems in high-rise residential buildings in hot and humid Gulf climates. It aims to identify key indoor air quality (IAQ) challenges in mechanically ventilated high-rise residences, assess how effectively FAHU systems maintain acceptable air quality, and evaluate design and operational strategies that can improve IAQ while managing energy use. The research also seeks to highlight limitations in current ventilation practices and propose evidence-based enhancements, including the adoption of IoT- and AI-enabled solutions for more responsive and efficient IAQ management. Ultimately, the study advances understanding of how to achieve healthier, more sustainable indoor environments in rapidly growing vertical urban developments.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a quantitative research methodology to evaluate the performance of FAHUs in maintaining IAQ and occupant satisfaction in high-rise residential buildings. A dual approach is employed, combining occupant surveys with real-time environmental monitoring through calibrated sensors. The focus is on assessing FAHU effectiveness under real-world conditions across different vertical zones of four residential towers. This methodological design enables a comprehensive analysis of IAQ variations and perceptions across floors and building configurations in a hot and humid climate.

2.1. Research Design

A randomized sampling strategy was applied to recruit participants from four residential high-rises (Towers A, B, C, and D). In collaboration with the facility management team, a Microsoft Forms survey, accessed via QR codes, was posted at the building entrances over a one-month period to encourage voluntary and anonymous participation. The survey was designed to collect occupant perceptions of IAQ and related factors, with a target sample size of 116 responses, statistically representative of the 679 total units across the buildings. The final sample included 40 respondents from Tower A, 32 from Tower B, 19 from Tower C, and 25 from Tower D. The sample size was calculated using the formula for a finite population of 679 units across all four buildings, with a 90% confidence level, a 7% margin of error, and a 50% population proportion, resulting in a sample of 116 surveys based on the formula:

where:

The survey instrument was structured to align with the research objectives and test specific hypotheses related to IAQ perception, occupant behavior, and building characteristics. Inferential statistical techniques, including Spearman’s rank correlation, Chi-square tests, and ANOVA, were used to analyze associations and draw meaningful conclusions.

Parallel to the survey, an experimental sensor-based design was implemented. IAQ monitors were installed in selected apartments to capture real-time pollutant concentrations and validate occupant feedback. This hybrid method strengthens the reliability and depth of the findings.

2.1.1. Sensor-Based Experiments

Sensor deployment was conducted in apartments located across different levels of Towers A–D, covering low-rise (Ground Floor–Level 10), medium-rise (Levels 11–20), and high-rise (above Level 20) units. Selection criteria included variation in floor height, the absence of air purification systems, prior survey responses indicating differing levels of IAQ satisfaction, and controlled building age. The building age was controlled by selecting structures that were neither too old nor newly constructed; the buildings were approximately five years old. Temtop LKC-1000S+ (2nd edition) sensors, from China were used to continuously record data over a seven-day period to capture both weekday and weekend conditions, ensuring that the full weekly cycle of indoor activities and occupant behavior was represented. The sensors measured temperature, relative humidity, particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), formaldehyde (HCHO), total VOCs, and the calculated Air Quality Index (AQI). All sensors were placed in living rooms for consistency, as these areas typically experience the highest occupancy and activity levels. The data were collected during June and July, corresponding to the summer period. During data collection, no natural ventilation from outside was allowed in order to maintain controlled indoor conditions and ensure that measured variations were primarily influenced by occupant activities rather than external airflow.

Data were statistically analyzed to detect pollutant trends, evaluate FAHU performance, and explore correlations between measured values and building characteristics or occupant activities.

2.1.2. Data Collection: Integrated IAQ Sensor Data and Resident Surveys

The study integrates both sensor data and structured survey responses. Environmental sensors recorded IAQ readings at one-minute intervals, yielding 1440 data points per apartment per day. These time-series datasets were complemented by resident surveys assessing perceived air quality, thermal comfort, and potential health effects.

The Temtop LKC-1000S+2nd sensors were selected for their capacity to capture multi-parameter IAQ data. All devices were pre-calibrated and validated in a controlled laboratory setting before deployment to ensure measurement accuracy and consistency across locations.

2.1.3. Survey Instrument and Statistical Testing

The survey instrument was structured to directly associate each question with its corresponding hypothesis, statistical test, and analytical objective. Table 1 focuses on questions regarding unit location within the building and time spent in the unit during weekends, highlighting potential effects on occupants’ air quality perceptions. Table 2 presents items addressing air freshness, overall satisfaction, and floor-level differences, along with the statistical analyses used to evaluate these relationships. Table 3 examines humidity variation across floors and the influence of FAHU maintenance frequency on perceived indoor air quality. Collectively, these tables provide a comprehensive framework linking survey questions to hypotheses, analytical methods, and evaluation objectives, facilitating a systematic assessment of IAQ factors in residential buildings. In this study, “air freshness” refers to occupants’ subjective perception of indoor air quality, encompassing sensations of adequate ventilation, absence of stale or unpleasant odors, and overall comfort of the indoor air, rather than a direct measurement of specific pollutant concentrations.

Table 1.

Survey Questions, Corresponding Hypotheses on Unit Location and Time Spent During Weekend.

Table 2.

Survey Questions and Hypotheses Related to Air Freshness, Satisfaction, and Floor-Level Differences.

Table 3.

Survey Questions with Hypotheses on Humidity Variation Across Floors and the Effect of Maintenance Frequency on IAQ Satisfaction.

2.2. Data Analysis

A multi-layered data analysis strategy was adopted. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize both sensor and survey data, highlighting key trends in IAQ indicators and occupant feedback. Inferential statistical analyses, including correlation coefficients, regression models, Chi-square tests, ANOVA, and Welch’s t-tests, were conducted to examine relationships between pollutant concentrations, floor levels, occupancy patterns, and satisfaction ratings. Comparative analysis across buildings and floors enabled the identification of recurring IAQ concerns and system inefficiencies.

2.3. Assumptions and Methodological Limitations

Several assumptions underpin this methodology:

- Climatic conditions are assumed to be relatively uniform across the studied buildings.

- All towers operate with similar FAHU-based ventilation systems.

- Selected apartments are assumed to have comparable layouts, reducing variability in internal pollutant sources.

- Survey responses are assumed to reflect honest and accurate perceptions.

Despite rigorous design, limitations include potential self-selection bias in survey participation, access constraints that may restrict sample diversity, and limited generalizability due to the specificity of the studied location. Sensor readings may also be affected by transient resident activities such as cooking or cleaning, though these were partially controlled through briefings and standardized sensor placements.

2.4. Validity and Reliability

Construct validity is supported by the alignment of survey instruments with research objectives and by the use of established IAQ parameters. Randomized sampling and multi-building data collection enhance external validity. Calibration and laboratory validation of sensors ensure measurement reliability. Finally, triangulation, integrating survey perceptions with empirical sensor measurements, provides a robust foundation for evaluating FAHU performance under real-world conditions.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the survey-based statistical analysis examining factors that may influence residents satisfaction with IAQ.

3.1. Survey Results

A total of 116 valid survey responses were collected for analysis. The required sample size was calculated using the finite population formula, across four buildings with 90% confidence level. Accordingly, the analyses presented in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 reflect the full set of 116 responses. For Table 7, one respondent did not answer the maintenance-frequency question; therefore, the analysis for that table is based on the remaining 115 valid responses.

Table 4.

Observed Frequencies: Unit Location vs. Satisfaction with Air Quality.

Table 5.

Observed Frequencies: Weekday Time Spent vs. Satisfaction.

Table 6.

Observed Frequencies: Weekend Time Spent vs. Satisfaction.

Table 7.

Observed Frequencies: Maintenance Frequency vs. Satisfaction.

3.1.1. Survey Q1: Unit Location vs. Satisfaction with Air Quality

Chi-square test: , . Table 4 shows the results of Q1 of the survey. The null hypothesis is not rejected; unit location is not significantly associated with satisfaction.

3.1.2. Survey Q2: Weekday Time Spent in Unit vs. Satisfaction

Chi-square test: , . The null hypothesis is rejected; weekday time spent is significantly associated with satisfaction. Table 5 shows the results of Q2 of the survey.

3.1.3. Survey Q3: Weekend Time Spent vs. Satisfaction

Chi-square test: , . The null hypothesis is not rejected; weekend time spent is not significantly associated with satisfaction. Table 6 shows the results of Q3 of the survey.

3.1.4. Survey Q4: Correlation Between Air Freshness and Satisfaction

A Pearson correlation revealed a strong positive relationship between air freshness and overall satisfaction:

Welch’s t-tests:

- GF–10 vs. Level 11–20: (not significant)

- GF–10 vs. Above Level 20: (not significant)

There is no evidence that lower floors (GF–10) have higher air freshness ratings.

3.1.5. Survey Q5: Humidity Ratings Across Floor Levels

Welch’s t-tests:

- GF–10 vs. Level 11–20: (not significant)

- GF–10 vs. Above Level 20: (not significant)

Humidity satisfaction does not differ significantly across floors, suggesting limitations in FAHU performance.

3.1.6. Survey Q6: Maintenance Frequency vs. Satisfaction

Chi-square test: , . There is a statistically significant association between duct maintenance frequency and satisfaction. Table 7 shows the results of Q6 of the survey.

3.2. Density Plot Analysis (Low-Rise, Mid-Rise, High-Rise Units)

This section presents how different AQI categories vary across the 24-h day. These smoothed probability distributions allow us to visualize the likelihood of each air-quality category occurring at different times, highlighting temporal patterns that may not be visible in raw data.

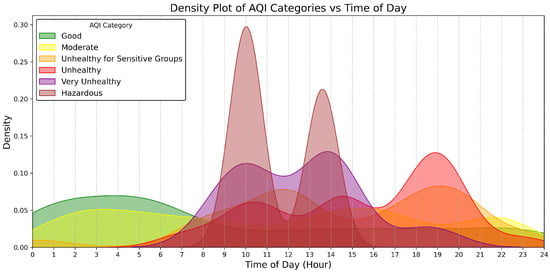

Low-Rise Unit

The “Unhealthy” category peaks around 8 a.m., likely reflecting outdoor traffic or industrial activity. “Good” and “Moderate” levels dominate early and late hours, while “Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups (USG)" values persist through the afternoon and evening, as is clear from Figure 1. “Very Unhealthy” and “Hazardous” rarely appear.

Figure 1.

Density Plot of AQI Categoris vs. Time of Day for Low-rise unit.

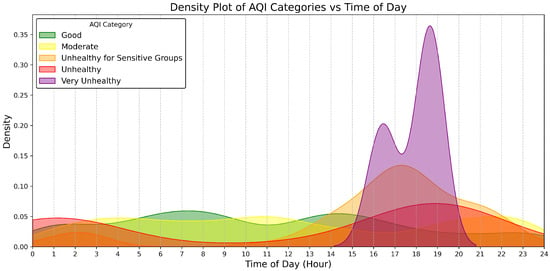

Mid-Rise Unit

“Good” dominates midnight–6 a.m. “Unhealthy” and “Very Unhealthy” levels surge between 9–11 a.m. and 6–8 p.m, as is shown in Figure 2. Occasional “Hazardous” peaks highlight periods of critical pollution.

Figure 2.

Density Plot of AQI Categoris vs. Time of Day for Mid-rise unit.

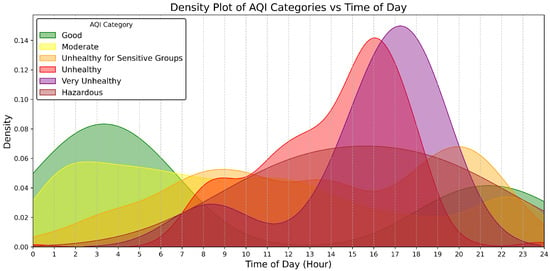

High-Rise Unit 1

A pronounced “Very Unhealthy” spike occurs between 5–8 p.m., seen in Figure 3. “Good” and “Moderate” dominate early mornings. No “Hazardous” readings are observed.

Figure 3.

Density Plot of AQI Categoris vs. Time of Day for High-rise Unit 1.

High-Rise Unit 2

As shown in Figure 4, air quality is poorest overall, with frequent “Unhealthy,” “Very Unhealthy,” and “Hazardous” episodes in the afternoon and evening. “Good” and “Moderate” categories occur mainly at night and early morning.

Figure 4.

Density Plot of AQI Categoris vs. Time of Day for High-rise Unit 2.

3.3. Comparative Analysis Across Flats

The Mid-rise Unit exhibits the best air quality, with substantial time spent in “Good” and “Moderate” categories. The High-rise Unit 2 shows the worst conditions, with persistent “Unhealthy” and “Very Unhealthy” levels and minimal “Good” periods. The Low-rise Unit trends toward “Moderate” but frequently reaches “USG.” The High-rise Unit 1 shows periodic spikes into “Unhealthy” and “Very Unhealthy.”

From the comparative analysis in Table 8, evenings and early nights are the most polluted across all units, while early mornings show cleaner conditions. These temporal patterns suggest interactions between outdoor traffic, industrial emissions, and indoor sources.

Table 8.

Summary of peak AQI timings, dominant categories, and observations for each flat.

Figure 5.

Bar chart comparing time spent in each category for each flat, by Category.

Figure 6.

Bar chart comparing time spent in each category for each flat, by flat.

- Mid-rise Unit maintains consistently favorable conditions.

- High-rise Unit 2 experiences severe and persistent pollution.

- Low-rise Unit shows moderate but unstable air quality.

- High-rise Unit 1 shows mixed conditions with severe evening peaks.

(Note: High-rise Unit 2 includes 6 days of data; others include 7.)

3.4. Influence of PM, TVOC, and Humidity on AQI Across Different Units

Correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of particulate matter (PM), total volatile organic compounds (TVOC), and relative humidity on the Air Quality Index (AQI) across three building types. Particulate matter consistently dominates AQI variability across all unit types. In mid-rise flats, PM2.5 and PM10 exhibit very strong correlations with AQI ( and , respectively), while TVOC shows a moderate positive correlation (). Relative humidity demonstrates a weak-to-moderate negative correlation with AQI ().

In low-rise flats, AQI remains strongly associated with PM2.5 and PM10 ( for both variables), whereas TVOC and relative humidity exhibit weak correlations ( and , respectively). Similarly, in high-rise buildings, PM2.5 and PM10 maintain strong correlations with AQI ( for both), while TVOC () and relative humidity () show negligible influence.

Overall, AQI variability across all building types is primarily driven by particulate matter, with gaseous pollutants and humidity contributing only secondary or minimal effects.

4. Discussion

This study investigated how residential characteristics, occupant behavior, and maintenance practices shape both perceived and measured IAQ within a multi-residential building. The integration of survey responses with time-resolved AQI data provides a multidimensional understanding of IAQ conditions, revealing nuanced relationships between environmental exposure, building operations, and subjective perceptions. The assumptions outlined in Section 4.2 were maintained to ensure a consistent comparative analysis; however, slight deviations may occur and could influence absolute values, though they are not expected to affect the relative trends observed in this study.

4.1. Residential Characteristics and Perceived Air Quality

Survey results showed no statistically significant association between unit location (floor level) and satisfaction with air quality. Neither the chi-square tests for satisfaction nor Welch’s t-tests for air freshness and humidity identified meaningful differences between floor categories. These findings suggest that vertical positioning in the building does not substantially influence resident-perceived IAQ, potentially indicating uniform performance of the mechanical ventilation systems across floors or, alternatively, highlighting the influence of other factors such as occupant habits or indoor sources.

Similarly, humidity ratings did not differ significantly between floor groups, pointing to potential limitations in the FAHU’s ability to maintain consistent humidity levels. Since humidity plays a critical role in comfort and pollutant behavior, the uniform (but suboptimal) ratings may reflect systemic HVAC performance constraints rather than actual homogeneity in environmental conditions.

However, when contrasted with the objective AQI results, notable discrepancies emerge. While residents perceive little difference across floors, the AQI measurements show substantial variation between units, including those at different heights. This divergence suggests that residents may rely more on sensory cues or expectations than on actual pollutant concentrations, indicating a disconnect between perceived and measured IAQ conditions.

4.2. Occupant Behavior and Exposure Duration

In contrast to unit location, time spent in the unit during weekdays exhibited a statistically significant association with air quality satisfaction. Respondents who spent longer durations indoors (8–12 h) reported lower levels of satisfaction, aligning with exposure theory whereby prolonged indoor stays amplify sensitivity to pollutant accumulation, inadequate ventilation, or recurring indoor pollutant sources.

Weekend exposure duration, however, did not show a significant association with IAQ satisfaction. This discrepancy may reflect differences in resident routines, more variable ventilation practices during weekends, or generally lower outdoor pollutant inflow. These results underscore exposure duration as a critical determinant of perceived IAQ.

This pattern aligns strongly with the AQI findings: the most polluted periods occur in late afternoon and evening, times when high-occupancy households are most likely indoors. Thus, objective exposure timing and subjective experience converge, reinforcing the significance of temporal occupancy patterns as a key driver of IAQ perception.

4.3. Air Freshness and Perceived Satisfaction

Air freshness ratings displayed a strong positive correlation with overall IAQ satisfaction (, ), indicating that sensory cues, such as odor, staleness, or perceived ventilation, strongly influence resident perceptions. This highlights the importance of intangible aspects of indoor environmental quality, which may not always align with measured pollutant levels but significantly shape user experience.

This perception-based linkage mirrors the AQI data in units such as the Mid-rise flat, where morning periods dominated by Good/Moderate AQI align with higher freshness-related satisfaction. Conversely, High-rise Unit 2’s chronic evening Unhealthy/Very Unhealthy spikes correspond to user-reported dissatisfaction, strengthening the connection between sensory ratings and actual pollutant conditions when pollution patterns are persistent and noticeable.

4.4. Maintenance Practices and IAQ Perception

Maintenance frequency emerged as a significant predictor of satisfaction. Units receiving more frequent duct cleaning were associated with higher satisfaction categories, whereas those with infrequent or no maintenance tended to report dissatisfaction. This suggests that operational practices, such as preventive maintenance, may have a greater influence on resident experience than architectural attributes such as floor height. These results point to building management strategies as pivotal for enhancing IAQ.

Although direct FAHU performance metrics were unavailable, the AQI differences between units, with High-rise Unit 2 exhibiting the poorest air quality, are consistent with the survey finding that inadequate maintenance correlates with lower satisfaction. This convergence implies that maintenance quality likely affects both subjective comfort and measured pollutant levels. FAHU systems accounted for a substantial share of building energy consumption (21–26%); however, higher energy use did not consistently result in improved IAQ. Instances of elevated humidity and pollutant levels despite significant energy input indicate operational inefficiencies, highlighting a trade-off between energy consumption and IAQ performance, particularly in hot and humid climates.

4.5. Objective AQI Measurements and Temporal Patterns

The density plot analysis revealed substantial temporal and spatial variability in AQI across the monitored flats. Mid-rise Unit demonstrated the best IAQ conditions, with prolonged periods in Good and Moderate AQI categories, while High-rise Unit 2 showed the poorest conditions, with frequent Unhealthy and Very Unhealthy readings. Low-rise Unit and High-rise Unit 1 exhibited intermediate but distinct pollution profiles, with High-rise Unit 1 experiencing the most severe evening peaks in the Very Unhealthy category.

Across all flats, the most polluted periods generally occurred during late afternoon and evening hours, potentially reflecting peak outdoor traffic emissions, cooking activities, or reduced ventilation flow. Early morning hours consistently showed improved air quality, suggesting natural overnight pollutant settling or reduced external pollutant ingress.

4.6. Integration of Perception and Measurement

Although floor level did not predict satisfaction, the objective AQI measurements revealed notable differences between flats, including those on different floors. This mismatch suggests that resident satisfaction may be shaped more by sensory indicators or expectations rather than by actual pollutant concentrations. The strong correlation with perceived freshness reinforces this interpretation.

The significant association between weekday exposure duration and dissatisfaction is more closely aligned with the AQI results, emphasizing that exposure time may be a more influential predictor of IAQ perception than structural factors such as height. These findings highlight the importance of considering both objective and subjective indicators when evaluating indoor environmental quality.

Overall, the comparative analysis demonstrates three key insights: (1) Subjective IAQ evaluations tend to reflect long-duration exposure patterns rather than short-term pollution spikes; (2) Residents may under-detect or normalize severe but transient pollution events captured by sensors (evening Very Unhealthy episodes in High-rise Unit 1 and Unit 2); and (3) Discrepancies between perceived and measured IAQ indicate the need for better occupant awareness, improved ventilation scheduling, and more transparent communication of IAQ conditions.

4.7. Practical Recommendations

Based on the findings, several actionable recommendations emerge for building managers, IAQ specialists, and facility operators:

- Enhance ventilation during peak pollution hours. Since AQI levels peak in late afternoon and evening, targeted increases in mechanical ventilation or filtration during these periods could mitigate pollutant buildup.

- Implement regular and preventive duct maintenance. The strong association between maintenance frequency and satisfaction underscores the importance of scheduled duct cleaning and system inspections.

- Improve air freshness perception. Strategies such as optimizing fresh air intake, maintaining clean filters, and addressing odor sources may improve sensory perceptions, which strongly influence satisfaction.

- Incorporate occupant exposure patterns in IAQ strategies. Residents spending long hours indoors are more sensitive to poor IAQ, suggesting that units with high daytime occupancy should receive enhanced ventilation or localized purification.

- Communicate IAQ conditions transparently. Sharing AQI trends or providing IAQ dashboards may help residents better understand environmental patterns and adjust behaviors accordingly.

- Investigate flat-specific pollution drivers. High rise units exhibit disproportionate pollution loads, indicating the need for localized inspections for structural leakage, malfunctioning ventilation, or external pollution pathways.

- Regulatory Alignment with Dubai Building Standards. FAHU operation and ventilation strategies should be explicitly aligned with the Dubai Building Code and Al Sa’fat Dubai Green Building Regulations. Regular verification of ventilation performance and system operation is recommended to ensure compliance throughout the year, particularly during peak summer conditions.

- Climate-Responsive FAHU Operation in Hot and Humid Conditions. Given Dubai’s hot and humid climate, FAHU systems should prioritize humidity control through optimized dehumidification strategies, high-efficiency filtration, and airtight façade sealing to minimize moisture ingress. Adaptive control strategies, supported by real-time IAQ monitoring, can help balance indoor air quality requirements with energy consumption during periods of extreme outdoor conditions.

4.8. Limitations and Future Work

While the study offers valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged:

- Limited sample size and temporal coverage. AQI data were collected from only four flats, with high rise Unit 2 having fewer monitoring days. Broader sampling is needed to generalize results.

- Potential self-reporting biases. Survey responses rely on subjective perceptions, which may not directly align with objective pollutant levels or may be influenced by individual sensitivity.

- Lack of pollutant-specific measurements. AQI, as an aggregated metric, does not distinguish between particulate matter, VOCs, humidity effects, or CO2 buildup. More granular sensor data would enhance diagnostic capability.

- Uncontrolled indoor activities. Cooking, cleaning, window opening, and other occupant behaviors were not controlled for, yet they likely contribute significantly to observed temporal variations.

- Limited assessment of HVAC system performance. While perceptions suggest possible FAHU limitations, the study did not include direct measurements of airflow rates, filter performance, or system efficiency.

Future research should expand IAQ monitoring to a larger number of residential units and extend observation periods to capture broader temporal variability. Pollutant-specific sensors should be incorporated to provide a more detailed characterization of indoor environmental conditions. Direct assessment of HVAC system performance, including airflow rates, filtration efficiency, and leakage, is also recommended. In particular, targeted FAHU performance testing should be undertaken to complement the findings of the present study and to verify the operational factors contributing to observed IAQ trends. Future studies should also examine the trade-off between FAHU energy consumption and IAQ performance by jointly evaluating energy use, ventilation effectiveness, and humidity control, with emphasis on energy-aware control strategies and demand-responsive operation. Future studies should also control for additional confounding variables such as resident behavior, appliance usage, and building characteristics in order to better assess the causal relationship between maintenance frequency and occupant satisfaction, as the correlation observed in this study does not imply causation. Furthermore, future work could integrate machine learning models to predict IAQ patterns based on external pollution levels, building characteristics, and occupancy behaviors, enabling more proactive environmental management. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining how IAQ interventions influence both measured conditions and resident satisfaction over time would help validate and refine the recommendations proposed here.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that IAQ in multi-residential buildings is shaped more by occupant exposure patterns and maintenance practices than by unit location. While floor level showed no significant association with perceived air quality, weekday exposure duration and duct maintenance frequency emerged as strong predictors of resident satisfaction. The objective AQI measurements revealed substantial spatial and temporal variations across flats, with evening hours consistently showing the poorest conditions. The integration of subjective perceptions and measured AQI underscores the need for improved ventilation strategies, routine maintenance, and targeted interventions in units with recurring pollution peaks. These findings highlight the value of combined qualitative and quantitative assessments for enhancing indoor environmental quality and supporting evidence-driven building management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.; Methodology, H.G., A.E. and K.J.; Software and IoT sensor integration, M.C.; Validation, H.G. and K.J.; Formal analysis, A.E. and L.G.; Investigation, A.E. and M.C.; Resources, H.G. and K.J.; Data curation, A.E. and L.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.E.; Writing—review and editing, L.G., H.G., Z.A. and R.A.; Visualization, A.E. and Z.A.; Supervision, H.G. and K.J.; Project administration, H.G. and A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by the University of Wollongong in Dubai. Grant ID: URC25008.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the corresponding authors due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ra’ed Alhammouri is employed by the company DAMAC Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IAQ | Indoor Air Quality |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter ≤ 2.5 µm |

| PM10 | Particulate Matter ≤ 10 µm |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SBS | Sick Building Syndrome |

| FAHU | Fresh Air Handling Unit |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| VRP | Ventilation Rate Procedure |

| IAQP | Indoor Air Quality Procedure |

| NVP | Natural Ventilation Procedure |

| AQI | Air Quality Index |

| HCHO | Formaldehyde |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GF | Ground Floor |

| USG | Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

References

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L. The role of indoor air quality in human health and comfort: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 29012–29023. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. The Inside Story: A Guide to Indoor Air Quality; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/inside-story-guide-indoor-air-quality (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Sekhar, S.C.; Goh, S.E. Thermal comfort and IAQ characteristics of naturally/mechanically ventilated and air-conditioned bedrooms in a hot and humid climate. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, K.J.; Razali, H.; Lim, C.H. Field investigation of thermal comfort and indoor air quality analysis using a multi-zone approach in a tropical hypermarket. Buildings 2025, 15, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, A.-A.M.; Okwuosa, C.C.; Uzuegbuanam, F.O.; Ugwu, L.E. A seasonal investigation of indoor air quality in relation to architectural features in government office buildings in Enugu, Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, R.; Chan, M.; Lee, T. Indoor air quality in residential buildings with high occupancy: Challenges and adaptive ventilation strategies. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 45, 102345. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.; Awad, A. Volatile organic compounds and radon in residential buildings in Dubai: An emerging IAQ issue. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Sekhar, S.C.; Melikov, A.K. Thermal comfort and IAQ assessment of under-floor air distribution system integrated with personalized ventilation in hot and humid climate. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 1906–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, C.; Zheng, L. Study of an integrated personalized ventilation and local fan-induced active chilled beam air conditioning system in hot and humid climate. Build. Simul. 2018, 11, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z. Sick Building Syndrome and its relation to indoor air quality: A historical and modern perspective. J. Environ. Health 2022, 85, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Künn, S.; Palacios, J.; Pestel, N. Indoor Air Quality and Cognitive Performance. IZA Discussion Paper No. 12632. 2019. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/207457 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- SkyscraperCenter. Tall Buildings: Global Statistics. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. 2023. Available online: https://www.skyscrapercenter.com (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Tham, K.W. Indoor air quality in high-rise buildings: Challenges and solutions. Build. Environ. 2016, 100, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Abdelaziz Mahmoud, N.S.; Alqassimi, N. Enhancing indoor air quality and sustainable living in newly constructed apartments: Insights from Dubai. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1292531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardoulakis, S.; Dear, K.; de Dear, R. Indoor air quality and pollutant levels: A systematic review of studies across 29 countries. Environ. Int. 2021, 148, 106366. [Google Scholar]

- Dubai Building Code. Building Design and Construction Standards for Dubai Residential and Commercial Buildings; Government of Dubai: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2019: Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.ashrae.org (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Sekhar, S.C.; Tan, L.T. Optimization of cooling coil performance during operation stages for improved humidity control. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, N.S.; Zaki, S.A.; Tuck, N.W.; Singh, M.K.; Rijal, H.B. Field study on thermal comfort and CO2 concentration in school classrooms in hot-humid climate Malaysia. In Multiphysics and Multiscale Building Physics; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.