Seasonal Dependence of Evaporation Characteristics over the North Atlantic and Reliability Assessment of Multiple Datasets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Evaporation Decomposition Method

3. Results

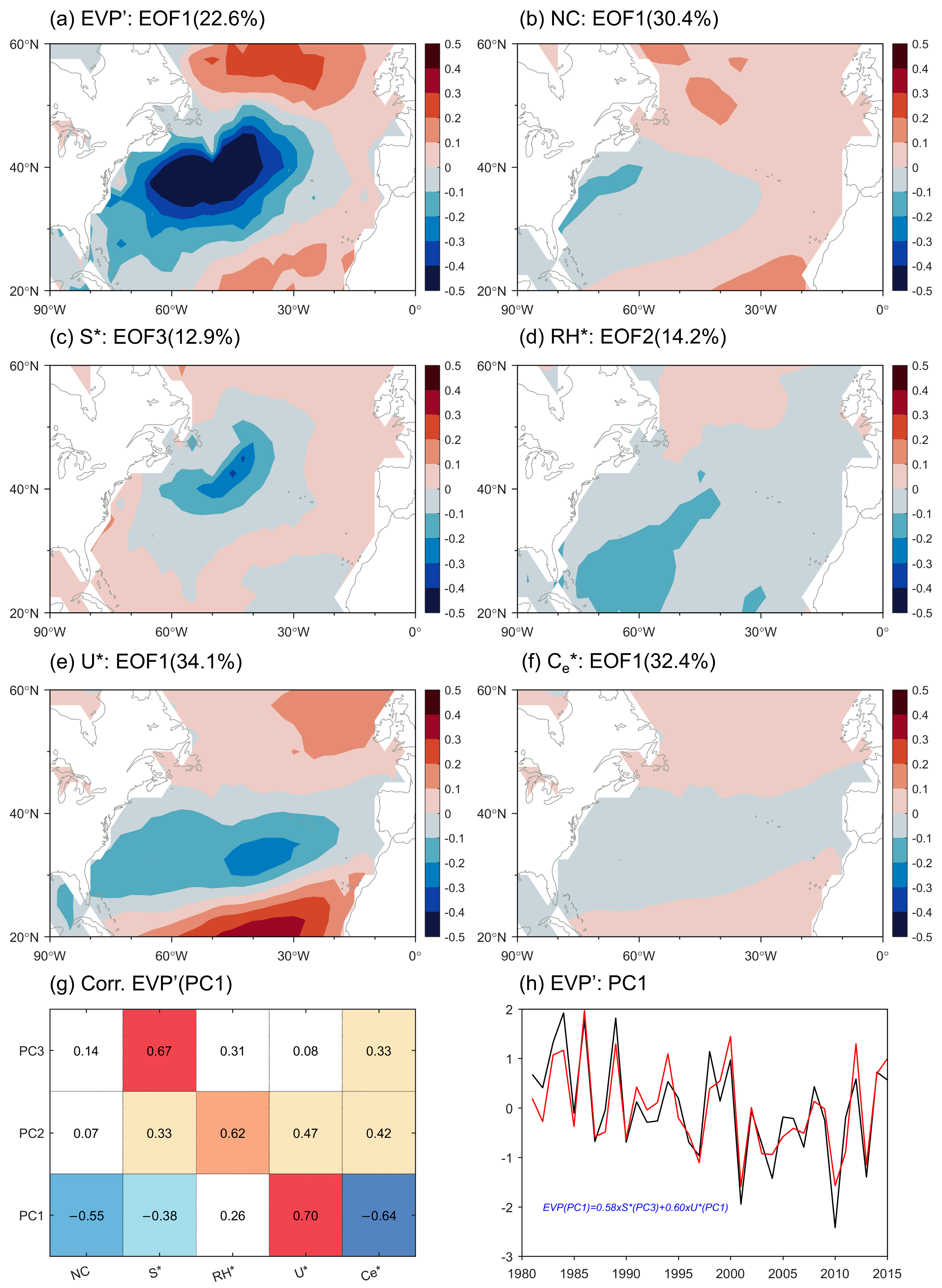

3.1. Warm Season Patterns

3.2. Cold Season Patterns

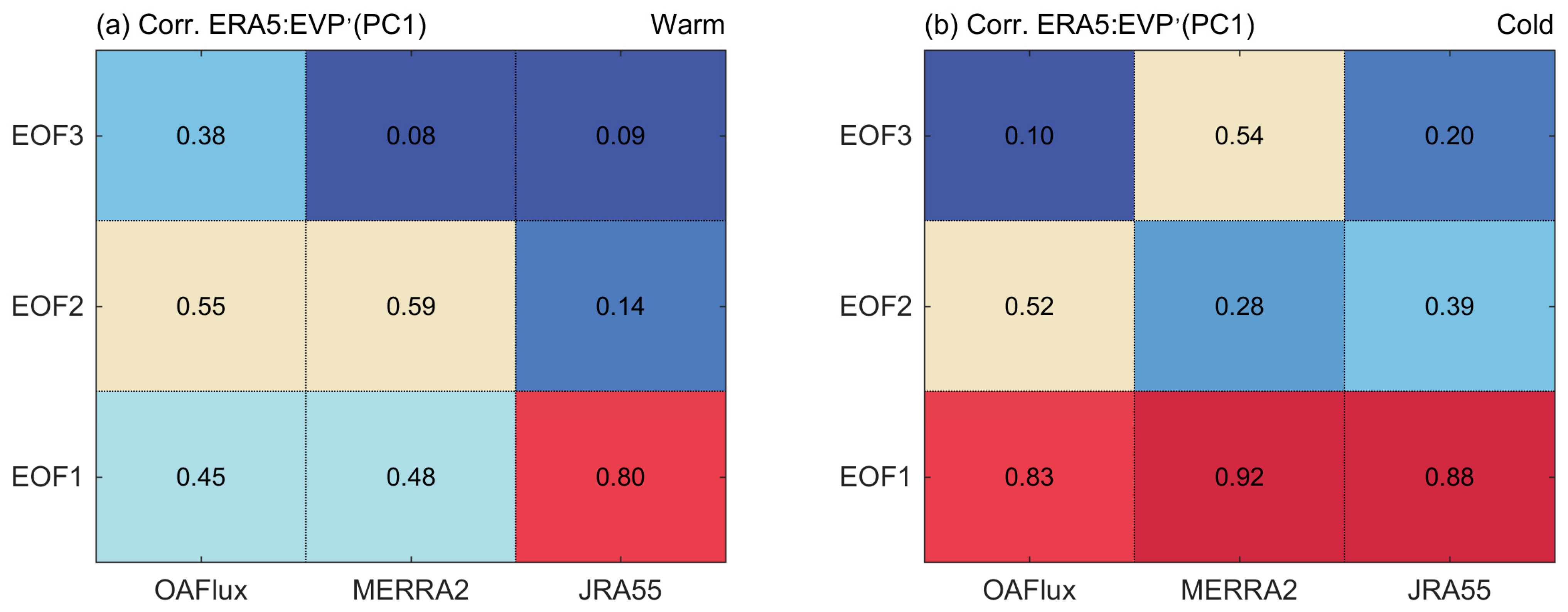

3.3. Reliability and Uncertainties of Evaporation Patterns

4. Conclusions

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buckley, M.W.; Marshall, J. Observations, Inferences, and Mechanisms of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation: A Review. Rev. Geophys. 2016, 54, 5–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srokosz, M.; Baringer, M.; Bryden, H.; Cunningham, S.; Delworth, T.; Lozier, S.; Marotzke, J.; Sutton, R. Past, Present, and Future Changes in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 93, 1663–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayan, D.R. Latent and Sensible Heat Flux Anomalies over the Northern Oceans: Driving the Sea Surface Temperature. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1992, 22, 859–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, R.; Li, T. Atmosphere—Warm Ocean Interaction and Its Impacts on Asian—Australian Monsoon Variation*. J. Clim. 2003, 16, 1195–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E.; Fasullo, J.T.; Mackaro, J. Atmospheric Moisture Transports from Ocean to Land and Global Energy Flows in Reanalyses. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 4907–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.M.; Ramos, A.M.; Raible, C.C.; Messmer, M.; Tomé, R.; Pinto, J.G.; Trigo, R.M. North Atlantic Integrated Water Vapor Transport—From 850 to 2100 CE: Impacts on Western European Rainfall. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, J.; Seidov, D.; Boyer, T. Water Vapor Transfer and Near-Surface Salinity Contrasts in the North Atlantic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Chiu, L.S.; Shie, C.-L. Trends and variations of ocean surface latent heat flux: Results from GSSTF2c data set. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.; Sutton, R.; Lohmann, K.; Smith, D.; Palmer, M.D. Causes of the Rapid Warming of the North Atlantic Ocean in the Mid-1990s. J. Clim. 2012, 25, 4116–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Global Variations in Oceanic Evaporation (1958–2005): The Role of the Changing Wind Speed. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 5376–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, I.V.; Alexeev, V.A.; Bhatt, U.S.; Polyakova, E.I.; Zhang, X. North Atlantic Warming: Patterns of Long-Term Trend and Multidecadal Variability. Clim. Dyn. 2010, 34, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, M.J.; Rowell, D.P.; Folland, C.K. Oceanic Forcing of the Wintertime North Atlantic Oscillation and European Climate. Nature 1999, 398, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Saravanan, R.; Chang, P. Free and Forced Variability of the Tropical Atlantic Ocean: Role of the Wind–Evaporation–Sea Surface Temperature Feedback. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 5958–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.E.; Portis, D.H. Variations of Precipitation and Evaporation over the North Atlantic Ocean, 1958–1997. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999, 104, 16613–16631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Kirtman, B.P.; Pegion, K. Local Air–Sea Relationship in Observations and Model Simulations. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 4914–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, Y.; Tozuka, T.; Masson, S.; Terray, P.; Luo, J.-J.; Yamagata, T. Subtropical Dipole Modes Simulated in a Coupled General Circulation Model. J. Clim. 2012, 25, 4029–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, F.R.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Roberts, J.B.; Reichle, R.H.; Adler, R.; Ricciardulli, L.; Berg, W.; Huffman, G.J. Consistency of Estimated Global Water Cycle Variations over the Satellite Era. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 6135–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosilovich, M.G.; Robertson, F.R.; Takacs, L.; Molod, A.; Mocko, D. Atmospheric Water Balance and Variability in the MERRA-2 Reanalysis. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Jin, X.; Josey, S.A.; Lee, T.; Kumar, A.; Wen, C.; Xue, Y. The Global Ocean Water Cycle in Atmospheric Reanalysis, Satellite, and Ocean Salinity. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 3829–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentamy, A.; Piollé, J.F.; Grouazel, A.; Danielson, R.; Gulev, S.; Paul, F.; Azelmat, H.; Mathieu, P.P.; von Schuckmann, K.; Sathyendranath, S.; et al. Review and Assessment of Latent and Sensible Heat Flux Accuracy over the Global Oceans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 201, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Curry, J.A. Variability of the tropical and subtropical ocean surface latent heat flux during 1989–2000. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L05706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolman, A.J.; de Jeu, R.A.M. Evaporation in Focus. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Feng, G. Spatial-Temporal Variation Characteristics of Global Evaporation Revealed by Eight Reanalyses. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2015, 58, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Global Air–Sea Fluxes of Heat, Fresh Water, and Momentum: Energy Budget Closure and Unanswered Questions. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2019, 11, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Dutta, U.; Rahaman, H.; Chaudhari, H.; Hazra, A.; Saha, S.K.; Veeranjaneyulu, C. Evaluation of Different Heat Flux Products Over the Tropical Indian Ocean. Earth Sp. Sci. 2020, 7, e2019EA000988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Su, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Feng, G. Decomposition of Trend and Interdecadal Variation of Evaporation over the Tropical Indian Ocean in ERA5. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Ota, Y.; Harada, Y.; Ebita, A.; Moriya, M.; Onoda, H.; Onogi, K.; Kamahori, H.; Kobayashi, C.; Endo, H.; et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: General Specifications and Basic Characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2015, 93, 5–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaro, R.; McCarty, W.; Suárez, M.J.; Todling, R.; Molod, A.; Takacs, L.; Randles, C.A.; Darmenov, A.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Reichle, R.; et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 2017, 30, 5419–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Thorne, P.W.; Banzon, V.F.; Boyer, T.; Chepurin, G.; Lawrimore, J.H.; Menne, M.J.; Smith, T.M.; Vose, R.S.; Zhang, H.-M. Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, Validations, and Intercomparisons. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 8179–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, I.; Xie, S.-P. Muted precipitation increase in global warming simulations: A surface evaporation perspective. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, D24118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L. Observed Positive Feedback between the NAO and the North Atlantic SSTA Tripole. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L06707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Resolution | Variable | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERA5 | 0.25° × 0.25° | EVP, U, RH, SAT | ECMWF |

| JRA55 | 1.25° × 1.25° | EVP, U, Q, SAT | JMA |

| MERRA2 | 0.625° × 0.5° | EVP, U, RH, SAT | NASA |

| OAFlux | 1° × 1° | EVP, U, Q, SAT | WHOI |

| ERSSTv5 | 2° × 2° | SST | NOAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Liu, S.; Huang, B. Seasonal Dependence of Evaporation Characteristics over the North Atlantic and Reliability Assessment of Multiple Datasets. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010026

Zhang Z, Zheng L, Liu S, Huang B. Seasonal Dependence of Evaporation Characteristics over the North Atlantic and Reliability Assessment of Multiple Datasets. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zengping, Lingfeng Zheng, Shuying Liu, and Bicheng Huang. 2026. "Seasonal Dependence of Evaporation Characteristics over the North Atlantic and Reliability Assessment of Multiple Datasets" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010026

APA StyleZhang, Z., Zheng, L., Liu, S., & Huang, B. (2026). Seasonal Dependence of Evaporation Characteristics over the North Atlantic and Reliability Assessment of Multiple Datasets. Atmosphere, 17(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010026