Abstract

The variation in the maximum usable frequency (MUF) during geomagnetic disturbances is a key parameter for high-frequency (HF) radio communications. This study investigates MUF variability and related ionospheric parameters during the first geomagnetic superstorm of solar cycle 24, on 17 March 2015 (the Saint Patrick’s Day storm). Using Digisondes at Sao Luis (equatorial) and Campo Grande (low-latitude, near the southern crest of the Equatorial Ionization Anomaly), we analyzed storm-time changes in the F region. During the main phase, two episodes of eastward Prompt Penetration Electric Fields produced rapid uplifts of the F2-layer peak height at São Luis, reaching altitudes up to 520 km, accompanied by MUF decreases of approximately 25% relative to quiet-day values. In contrast, Campo Grande exhibited a more subdued response, with MUF deviations generally remaining within 15–20% of quiet-time conditions. During the recovery phase, the likely occurrence of a westward disturbance dynamo electric field was inferred from suppression of the Pre-Reversal Enhancement and decreased F-layer heights at São Luis. Comparative analysis highlights distinct regional responses: São Luis showed strong storm-time deviations, while Campo Grande remained comparatively stable under the impacts of Equatorial Ionization Anomaly effects. These results provide quantitative evidence of localized geomagnetic storm impacts on MUF in the Brazilian sector, offering insights that may improve space weather monitoring and HF propagation forecasting.

1. Introduction

The Earth’s ionosphere is part of the terrestrial atmosphere, ranging from about 90 km to more than 500 km altitude, where there is a sufficient amount of charges [1,2,3]. This part of the terrestrial atmosphere is important because it reflects and modifies radio waves used for communication and navigation. The Earth’s ionosphere has often been studied within three latitude zones: high latitudes, middle latitudes, equatorial, and low latitudes. The equatorial and low latitude ionosphere is a region of great interest and extensive studies, because of complex eletrodynamical processes and instabilities that occur there [1,4,5,6].

The ionospheric parameter called Maximum Usable Frequency (MUF) is of great importance for high-frequency (HF) radio communication, and strongly depends on the ionospheric plasma density, NmF2, which is related to plasma critical frequency, foF2, analyzed in this paper. In practical terms, MUF increases as NmF2 increases, because higher electron density allows higher frequencies to be refracted back to Earth rather than escaping into space. Since NmF2 is directly proportional to the square of foF2 (see Equation (1) in Section 2), even moderate changes in foF2 can produce significant changes in MUF. Under this point of view, the spatial and temporal variations in the ionospheric plasma density strongly influence the frequencies available for propagation in point-to-point communications.

The primary goal of most ionospheric research is to develop an understanding of how the ionosphere responds to geomagnetically disturbed conditions and how these changes will influence radiowave propagation via the ionosphere. The ionosphere plays a significant role as a medium of HF radio propagation that affects communication and remote sensing applications across the world. In this way, the highly variable nature of the ionosphere can be a limitation, and as such, there is a great need to study it [7,8]. The energy and momentum deposited into the ionospheric system during geomagnetic activities strongly influence and disturb the dynamics of the system [9,10]. Tulasi Ram et al. [11] and Ram et al. [12] described geomagnetic storms as disturbances that are due to the complex interactions between the interplanetary magnetic field and the geomagnetic field. It has been an important space weather phenomenon that has had the most impact on the ionosphere-thermosphere system and varies with the latitude, altitude, local time, station, and phase of geomagnetic activity, due to the various electrodynamic and neutral interactions that occur.

During geomagnetic storms, the equatorial zonal electric field undergoes significant perturbations that alter plasma density distributions and create sharp gradients in the equatorial and low-latitude ionosphere [13,14,15]. These electric field disturbances are primarily driven by two mechanisms: the prompt penetration electric field (PPEF) and the disturbance dynamo electric field (DDEF). PPEFs originate from solar wind-magnetosphere interactions and propagate rapidly from high latitudes to the equator. These fields manifest as undershielding (dawn-to-dusk) or overshielding (dusk-to-dawn) electric fields, resulting in enhanced eastward (upward) or westward (downward) ExB drifts, respectively, depending on the local time sector [12,16]. In contrast, DDEFs arise from thermospheric wind circulation changes initiated by storm-time energy deposition at high latitudes [17,18]. These fields develop more gradually and persist into the storm’s recovery phase. In general, DDEFs are westward during the day and eastward at night, with their characteristics modulated by local time, storm phase, and latitude. DDEFs typically lead to downward ExB drifts in the post-storm period, but the drift direction can vary based on the evolving thermospheric wind patterns and the intensity of storm-induced forcing.

Geomagnetic disturbances, such as substorms and storms, are primarily triggered by the southward turning of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) Bz component, which facilitates magnetic reconnection with the Earth’s dayside magnetosphere [19,20,21]. This reconnection process enables the transfer of solar wind energy into the magnetosphere, leading to an intensification of the ring current. The enhanced ring current generates a magnetic field that opposes the Earth’s horizontal geomagnetic field, resulting in a noticeable depression of the Sym-H index. Simultaneously, the AE index increases markedly due to enhanced auroral electrojet activity, reflecting energy injection into the auroral region.

Numerous studies have investigated the ionospheric response to geomagnetic storms, with particular attention to the 17 March 2015 Saint Patrick’s Day storm. Ram et al. [12] analyzed the storm-time zonal electric field behavior over the Asian sector using ionosonde and satellite observations. Astafyeva et al. [22] examined changes in ionospheric total electron content (TEC) over both the American and Asian regions using Global Positioning System (GPS)-based TEC and satellite data. Nava et al. [23] used Global and Regional TEC maps to study the ionospheric disturbances across the Asian, African, and American sectors. In the Brazilian context, Venkatesh et al. [13] employed GPS-TEC, ionosonde, and magnetometer data to analyze the low-latitude ionospheric response and reported the occurrence of a Super Fountain effect.

Recent multi-instrument studies also document extreme storm responses relevant to this work, including global ionospheric disturbances during the May 2024 superstorm [24,25] and dramatic expansion/merging of the equatorial ionization anomaly (EIA) crests under strong electrodynamic forcing [26]. Region-specific analyses likewise show pronounced low-latitude impacts on Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signals and ionospheric structure [27,28]. These findings motivate our Brazilian-sector, MUF-focused analysis for the 17 March 2015 event.

The Brazilian ionosphere also lies within the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly (SAMA), where the geomagnetic field is anomalously weak. As a result, the vertical drift, proportional to , is enhanced, making the EIA more responsive to storm-time electrodynamic forcing in this sector compared to others [29,30,31,32]. This regional peculiarity amplifies the impacts of prompt penetration and disturbance dynamo fields on plasma redistribution, height variations, and MUF behavior, underscoring the importance of studying storm-time responses over Brazil.

However, despite the extensive research on the effects of geomagnetic storms on ionospheric HF radio wave propagation, several critical questions remain unanswered, particularly regarding the impact of such storms on the MUF used in radio-wave signal transmission. Most previous studies have focused on the ionospheric electron density, TEC, and electric field variations, but there is limited research on how geomagnetic storms affect the MUF, especially in the Brazilian equatorial and low-latitude ionosphere. This study fills this gap by providing a detailed analysis of the MUF variations during the 2015 Saint Patrick’s Day storm, with a focus on the Brazilian region, which is characterized by unique electrodynamic processes due to its proximity to the magnetic equator within the SAMA. The novelty of this study lies in the following aspects:

- Focus on MUF: While previous studies have extensively analyzed ionospheric parameters such as TEC and foF2, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of the MUF, which is crucial for HF radio communication. We investigate how the MUF is influenced by the storm-induced changes in the F-region heights and plasma densities. The Brazilian ionosphere is particularly sensitive to geomagnetic disturbances due to its location near the magnetic equator within the SAMA, and this study presents new observational evidence of how MUF variations correlate with PPEF-driven electrodynamic processes in this region, in respect to this storm.

- Long Recovery Phase: The 2015 Saint Patrick’s Day storm had an unusually long recovery phase, which is not well understood. This study investigates and reveals how this prolonged recovery phase affected ionospheric parameters, particularly showing how disturbance dynamo effects modified the typical MUF patterns at equatorial and low latitude regions.

- F3 Layer Formation: Our observations document the complete life cycle of storm-induced F3 layer formation, from its genesis during PPEF events to its dissipation. We demonstrate how the F3 layer’s formation through vertical redistribution of the F2 layer directly impacts radio propagation characteristics, with quantitative evidence of its effects on MUF variations. This provides new insights into the connection between electric field enhancements and multi-layer ionospheric structures in the Brazilian sector under the impact of the anomalously weak magnetic field. Thus, in contrast to Venkatesh et al. [13] and Astafyeva et al. [22], our work uniquely provides quantitative MUF deviations and documents the complete F3-layer life cycle in the Brazilian sector.

In this paper, we discuss the impact of PPEF on the F-region heights and frequencies and on the MUF during the distinct phases of the storm driven by an Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection (ICME). We also discuss the long recovery phase, which is likely caused by the combined effects associated with a Corotating Interaction Region (CIR) and High-Speed Solar Wind Stream (HSSWS). By focusing on these aspects, this study contributes to a better understanding of the ionospheric response to geomagnetic storms and provides valuable insights for improving space weather prediction models and HF radio communication systems.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data

In this work, we processed and analyzed ground- and satellite-based data, including solar, interplanetary, geomagnetic, and ionospheric parameters and indices. Ionospheric data were provided by the Estudo e Monitoramento Brasileiro do Clima Espacial (EMBRACE), Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), through the Space Weather Data Share (http://www2.inpe.br/climaespacial/SpaceWeatherDataShare/search/ accessed on 20 January 2020). The ionospheric parameters were manually scaled using SAO Explorer software, version 3.5 [33,34], which ensures higher accuracy in extracting critical ionospheric parameters such as the critical frequency (foF2), peak height (hmF2), and virtual height (h’F) of the F2 layer.

To quantify the reliability of the manual scaling procedure, we included uncertainty estimates for the primary parameters. Typical uncertainties are MHz for foF2, km for hmF2, and km for h’F, while the observed MUF values have an uncertainty of approximately MHz. These values are based on SAO Explorer documentation and validation studies comparing manual scaling against independent ionosonde datasets. Although inter-operator variability is minimized by using standardized scaling procedures, these uncertainties represent the expected range of variation under standard conditions.

The ionosonde systems used in this study, DGS-256 at Sao Luis (SL) and DPS-4 at Campo Grande (CG), transmit short-duration radio pulses over a frequency range of 1–30 MHz and measure the time delay of echoes returned from ionospheric layers. From these echoes, ionograms are produced, which provide frequency virtual height characteristics of the ionosphere. Each instrument records ionograms at 15-min intervals, allowing for high temporal resolution in capturing ionospheric variability.

We analyzed ionospheric data from 16 March (the day before the initial phase of the ICME-driven storm) to 18 March (the first day of the recovery phase of the CIR-driven storm). The 2015 Saint Patrick’s Day storm was characterized by an unusually long recovery phase, likely influenced by the combined effects of an ICME and a CIR, followed by a HSSWS. This extended recovery phase provides a unique opportunity to study the prolonged effects of geomagnetic disturbances on the ionosphere.

The storm interval days were identified using the high-resolution Sym-H index from the NASA OMNIWeb Plus portal at http://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov (accessed on 25 January 2020). To compare the effects of the geomagnetic storm on the ionosphere, we selected the five geomagnetically quietest days in March 2015, using the geomagnetic index Kp as a reference according to the International Association of Geomagnetism and Aeronomy (IAGA) classification (http://wdc.kugi.kyoto-u.ac.jp/qddays/index.html accessed on 2 December 2019).

The foF2 represents the highest frequency that can be reflected vertically from the F2 layer, directly related to the maximum electron density () via the relationship:

where foF2 is in MHz. The hmF2 is the true height at which this maximum electron density occurs, while h’F is the apparent virtual height inferred from signal travel time. These parameters are fundamental in determining MUF, which depends both on the peak plasma frequency (foF2) and on the propagation path geometry.

The ionospheric parameters surveyed and analyzed in this study include:

- The critical frequency of the ordinary wave of the F2 layer, foF2 (in MHz),

- The actual peak height of the ordinary wave of the F2 layer, hmF2 (in km),

- The F-layer virtual height, h’F (in km),

- The observed Maximum Usable Frequency for a propagation distance of 3000 km, MUF(D) (in MHz),

- The calculated MUF (in MHz), and

- The transmission or propagation factor, M(D) (a dimensionless quantity).

The analysis of these parameters during the distinct phases of the geomagnetic storm provides valuable insights into the ionospheric response, particularly in the Brazilian equatorial and low-latitude regions impacted by the SAMA. Unlike automated scaling techniques, which often rely on pre-set thresholds and algorithms that may misinterpret complex ionospheric signatures, especially during geomagnetically disturbed periods, manual scaling provides more reliable and accurate parameter extraction. In this study, manual scaling was performed using SAO Explorer software (version 3.5), a widely accepted tool. The process involved identifying and tracing the F2 layer ordinary mode echoes on the ionogram plot, which is a visual representation of signal reflections at various frequencies and virtual heights. The foF2 was determined by locating the highest frequency at which a clearly defined ordinary F2 trace was still present. The hmF2 was extracted from the peak of the ordinary trace in terms of virtual height and corrected using inversion techniques embedded within SAO Explorer to obtain the true height. Similarly, h’F was identified as the virtual height at the lowest usable frequency for the F-layer trace.

The MUF for a given path is the highest radio frequency that can be refracted back to Earth by the ionosphere under specific conditions. For oblique paths, MUF can be expressed as:

where is the propagation factor for the path length D, determined by the ionospheric height and Earth’s curvature. This propagation factor accounts for the fact that signals travel along a longer, oblique path rather than directly vertical.

For the observed MUF(D), SAO Explorer directly computes this parameter based on the ionogram trace geometry and the selected radio path distance (set to 3000 km for this study). The software uses a built-in algorithm that calculates MUF using the foF2 and inferred virtual height, incorporating corrections for ray path curvature due to Earth’s spherical shape. However, to ensure accuracy, especially under Spread-F conditions or when ionospheric irregularities caused trace distortion, we manually adjusted the MUF values by cross-referencing them with known propagation curves and critical reflection heights. This manual interpretation approach allowed for the identification of subtle features such as Spread-F, multi-peak structures, and transient uplifts or reductions in F2 height, which are often missed or mischaracterized by automated systems. Consequently, the manually scaled observed MUF values used in this study offer a high-confidence dataset for analyzing ionospheric dynamics during the Saint Patrick’s Day geomagnetic storm.

The calculated MUF were obtained based on the approach reported by Souza et al. [35], which employs the propagation factor, or M-factor, and accounts for Earth’s spherical geometry as well as ionospheric refraction. In this method, the initial MUF estimation follows the Equation (1) of Souza et al. [35], where M(D) is a dimensionless propagation factor that depends on the virtual height and the geometry of the propagation path. The M-factor itself is calculated using the Equation (4) of Souza et al. [35]. In our implementation, we used the measured peak height hmF2 to better reflect ionospheric refraction and geomagnetic disturbances. The analysis was carried out in two stages. First, a quiet-day baseline was established using the mean hmF2 derived from the five geomagnetically quietest days in March 2015. Then, for disturbed-day analysis, the same foF2 values were retained while the disturbed hmF2 values were substituted into the M-factor calculation. This approach allowed us to isolate the impact of storm-induced changes in ionospheric height on MUF.

Souza et al. [35] method stands in contrast to the more theoretical ray-tracing approach described by Hysell [36] in Equation (9.10), which models the ionosphere as a spherically stratified medium and applies Snell’s Law to account for refractive effects. While Hysell [36]’s formulation is grounded in first-principles physics and is ideal for scenarios with detailed knowledge of true ionospheric heights and refractive index profiles, Souza et al. [35]’s approach is more practical and suited for operational analyses where only ionogram data are available. By comparing both observed and calculated MUF values, we were able to investigate how changes in hmF2—often influenced by geomagnetic drivers such as prompt penetration electric fields (PPEFs)—impact the MUF during storm-time conditions.

2.2. Identification of Events from Observations

In this study, the identification of PPEF and DDEF effects relied entirely on observational data, without the use of numerical modelling or ray-tracing simulations. PPEF signatures were inferred through the combined analysis of solar wind parameters, geomagnetic indices, and ionospheric measurements from ionosondes. The primary data sources used for this identification were: the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) and interplanetary electric field from the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) spacecraft (via NASA’s OMNIWeb database), the Sym-H index as a proxy for global ring current development, and ionosonde-derived parameters (hmF2, h’F, foF2, and MUF) from the SL and CG stations.

Following the methodology outlined in Abdu et al. [37], Kuai et al. [38], Polekh et al. [39], Singh et al. [40], a PPEF event was considered to occur when: a rapid southward turning of IMF was observed, often accompanied by an increase in (positive dawn-to-dusk orientation), and this change coincided (within minutes to tens of minutes) with a sharp uplift in hmF2 and/or h’F at the equatorial station (SL), and corresponding changes in MUF relative to its quiet-day baseline.

In the present study, we defined quantitative thresholds for identifying PPEF events: an uplift in hmF2 exceeding 50 km within a 15-min interval, or a MUF deviation greater than 15% relative to quiet-day averages. These thresholds were selected to distinguish genuine storm-time electrodynamic responses from normal day-to-day ionospheric variability.

This timing relationship is consistent with the known rapid transmission of interplanetary electric field variations into the low-latitude ionosphere through magnetospheric coupling processes [41]. The absence of significant neutral wind delays in such cases distinguishes PPEF effects from disturbance dynamo electric fields (DDEF), which typically evolve on longer timescales. By correlating these observational indicators across multiple datasets, we were able to attribute specific storm-time ionospheric responses to PPEF forcing with high confidence, despite not employing a numerical simulation framework.

Table 1 shows the location, geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude), and geomagnetic latitude of the two representative stations used in this study, along with their system and instrument codes. Solar, interplanetary, and geomagnetic indices and parameters were extracted from measurements taken by the ACE spacecraft, located at the Lagrangian point L1, and made available through the OMNIWeb Plus database provided by the Space Physics Data Facility (SPDF) of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (http://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov accessed on 25 January 2020).

Table 1.

Location, geographic coordinates, and dip latitude of the representative stations, along with their system and instrument codes.

Providing these measurements and computation details is essential because MUF is the main parameter under investigation in this work, and its variation reflects storm-induced changes in electron density distribution. The inclusion of both observed and calculated MUF values allows for a more complete characterization of the ionospheric response and a clearer attribution of changes to specific electrodynamic drivers. In the following section, we present and discuss the results, focusing on the variations in foF2, hmF2, and MUF, and their implications for HF radio communication during geomagnetic disturbances.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Saint Patrick’s Day Geomagnetic Storm: 17–25 March 2015

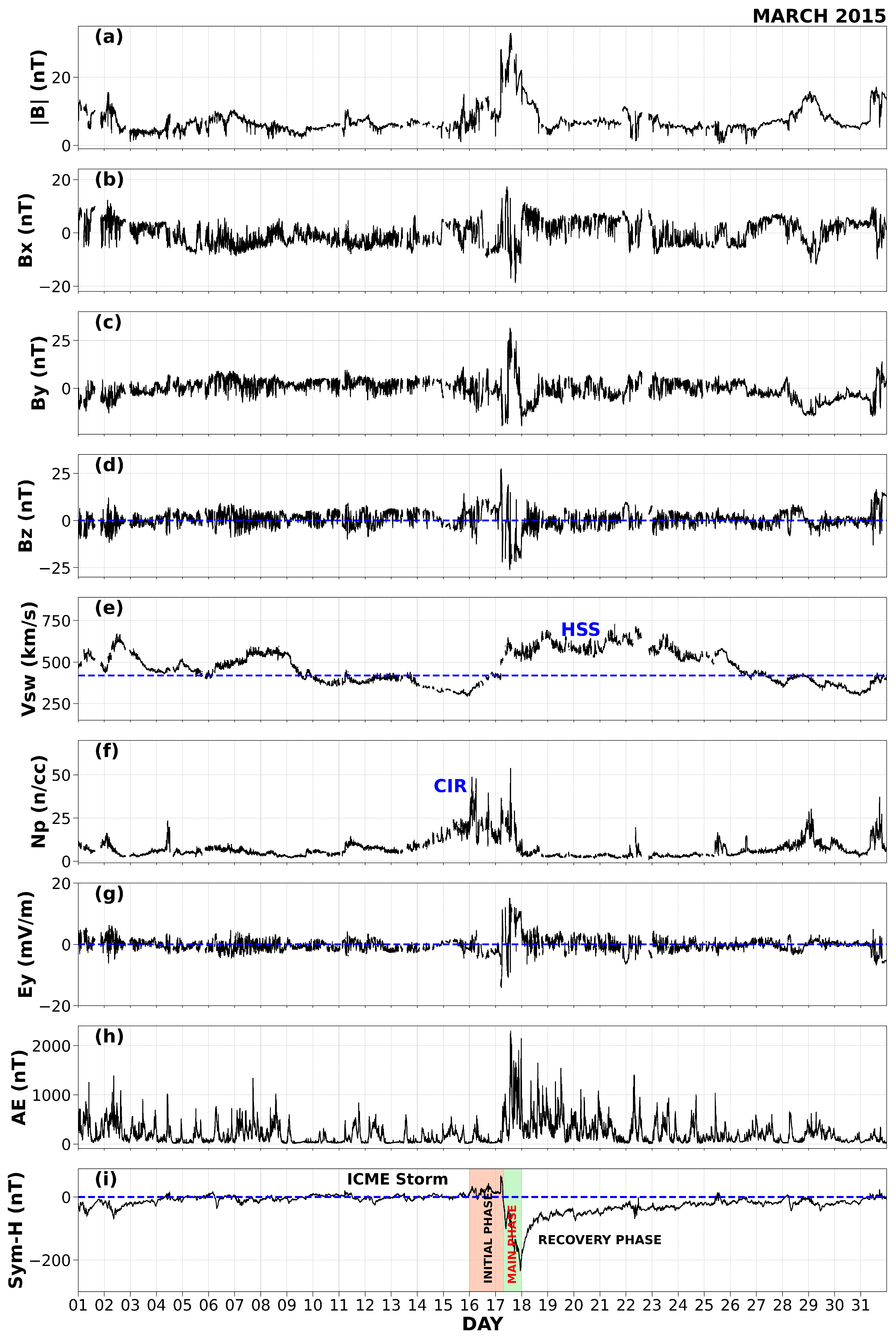

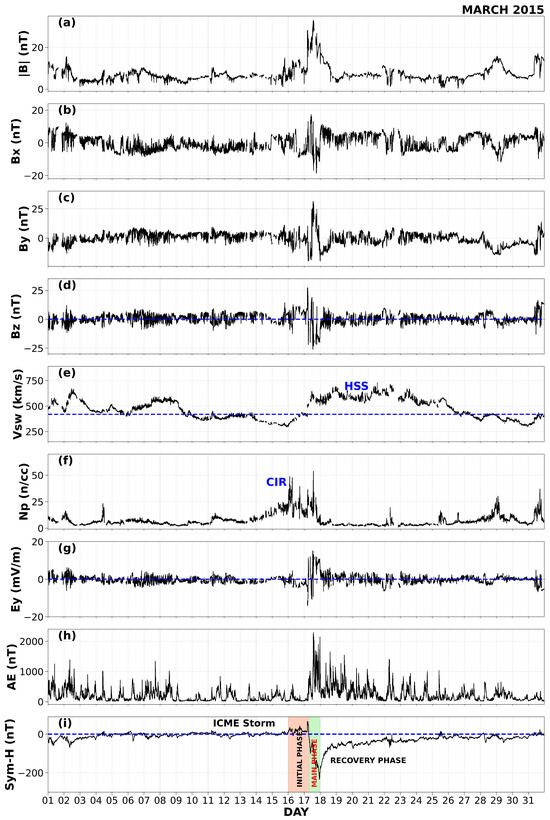

Figure 1 presents the variation of the interplanetary and geomagnetic indices in March 2015. Panel (a) shows the IMF magnitude (nT), representing the magnitude of the average field vector provided in the OMNIweb database. Panels (b)–(d) show the IMF components , , and in GSM coordinates (nT). Panel (e) gives the solar wind speed (km/s), while Panel (f) shows the proton density (cm−3). Panel (g) presents the interplanetary electric field (mV/m), computed as . Panel (h) shows the auroral electrojet index AE (nT), and Panel (i) displays the one-minute Sym-H index (nT) as a measure of the ring current intensity.

Figure 1.

Variations of the interplanetary and geomagnetic indices during March 2015. From top to bottom panels: (a) Interplanetary magnetic field magnitude (the magnitude of the average IMF vector from the OMNIweb database) and the B field components (b) , (c) , (d) in GSM coordinates (nT); (e) Solar wind speed, (km/s); (f) Proton density, (cm−3); (g) Interplanetary electric field, (mV/m), where ; (h) Auroral electrojet index, AE (nT); and (i) One-minute resolution ring current index, Sym-H (nT).

According to Wu et al. [42] and Astafyeva et al. [22], the solar event (a C9.1/1F flare at S22W25) and a series of type II/IV radio bursts occurred on 15 March 2015. As a result, an ICME reached the Earth’s magnetosphere on 17 March, appearing as a shock wave identified by a step increase in the solar wind speed (Panel e). The disturbance is evident across interplanetary parameters, with corresponding variations in the geomagnetic indices, including a sharp depression in Sym-H to nT (Panel i), characteristic of a major storm [43]. A sudden storm commencement (SSC) was seen as a positive incursion of Sym-H (Panel i) at 04:45 UT, after which turned strongly southward. This southward perturbation of IMF was the key driver of magnetic reconnection and the onset of the geomagnetic storm. The sequence of strong southward , enhanced solar wind driving, and a prolonged recovery is consistent with patterns reported for recent extreme events, including the May 2024 storm, which exhibited sustained global ionospheric disturbances [24,25].

The main phase of the storm lasted until Sym-H reached its minimum value ( nT) on 17 March at 23:30 UT (Panel i). During this phase, the IMF magnitude exceeded 30 nT (Panel a), and both and exhibited large oscillations (Panels b–c). The disturbed interval also included abrupt changes in solar wind speed (Panel e), proton density (Panel f), and IMF components (Panels b–d). Based on the Sym-H index (Panel i), the main phase is identified as lasting about 19 h, after which the recovery phase extended from 18–25 March. Notably, the ICME-driven storm was followed by a CIR and a High-Speed Stream (HSS), marked by a proton density enhancement (Panel f) and a subsequent rapid increase in solar wind speed (Panel e) [44,45]. As the HSS arrives, the solar wind speed increases while proton density decreases, as seen in Panels (e) and (f) of Figure 1. These structures likely contributed to the unusually prolonged recovery phase.

The results presented in Figure 1 confirm several findings from previous research while also providing new insights into the behavior of the ionosphere during the 2015 Saint Patrick’s Day geomagnetic storm. For instance, the observed southward turn of the IMF component and its role in driving geomagnetic storms align with the findings of Russell et al. [21] and Gonzalez et al. [43], who identified the southward IMF as a major factor in magnetic reconnection and storm initiation. Additionally, the prolonged recovery phase observed in this study is consistent with the findings of Wu et al. [42], who also noted the extended recovery period of the Saint Patrick’s Day storm.

The interplanetary and geomagnetic conditions depicted in Figure 1 provide a foundation for understanding the ionospheric response to the storm. The sharp increase in solar wind speed and the abrupt changes in proton density during the CIR and HSS phases highlight the dynamic nature of solar wind-magnetosphere interactions. These variations in solar wind parameters are essential for understanding the energy transfer processes that drive geomagnetic storms and their effects on the ionosphere. The prolonged recovery phase, influenced by the combined effects of the ICME, CIR, and HSS, underscores the complexity of geomagnetic storm dynamics and their long-lasting impacts on the Earth’s magnetosphere and ionosphere.

3.2. Brazilian Low Latitude Ionospheric Response: foF2 and MUF

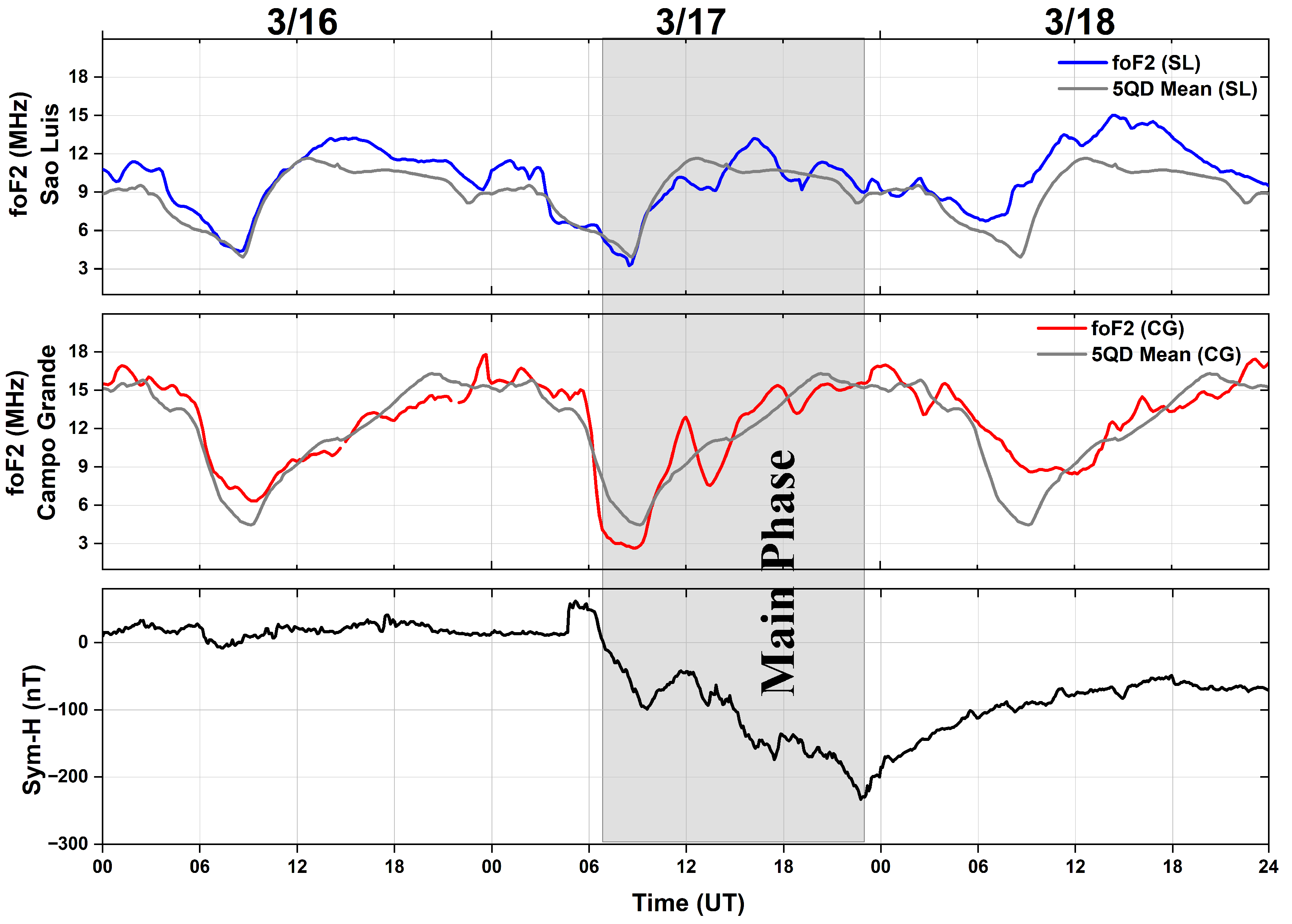

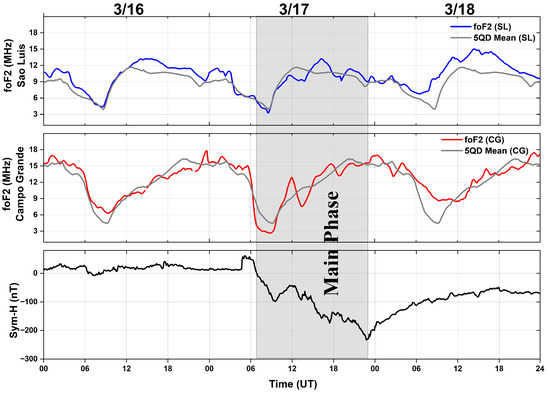

To examine the low-latitude ionosphere’s response to the Saint Patrick’s Day storm in March 2015, we present the variations in the plasma frequency, foF2 (as defined in Equation (1), Section 2), using Digisonde measurements from two representative locations: the equatorial region: SL (2.5° S, 44.3° W dip in 2015: 5° S) and the south crest of Equatorial Ionization Anomaly (EIA), CG (20.44° S, 54.65° W dip in 2015: 22.3° S). Figure 2 shows the variations in foF2 at these two stations during the storm interval, along with the average of the five quietest days (5QD), calculated based on the International Quiet Days (IQD) list, for comparison. The top panel presents the foF2 variation at SL, the middle panel shows the foF2 variation at CG, and the bottom panel displays the Sym-H index in nT.

Figure 2.

foF2 variation at Sao Luis (SL) and Campo Grande (CG), the two stations during the storm interval. At the top panel, the foF2 variation is presented with the 5QD at Sao Luis; the middle panel shows the foF2 and its 5QD curves at Campo Grande, and the bottom panel presents the Sym-H variation for the interval.

The parameter foF2 is the plasma critical frequency of the F2 layer and is directly determined by the peak electron density (). By contrast, the maximum usable frequency for an oblique HF link depends on both the ionospheric state and the propagation geometry (see Equation (2)). In that relation, the path-dependent propagation factor captures the effects of Earth’s curvature and the effective reflection height (e.g., h’F/hmF2). Because varies with height and geometry, MUF deviations need not track foF2 changes one-to-one; for example, storm-time uplifts of the F layer can modify and increase or decrease MUF even when foF2 changes are modest. This distinction is essential when interpreting differences between foF2 (Figure 2) and MUF (Figure 3) during storm intervals.

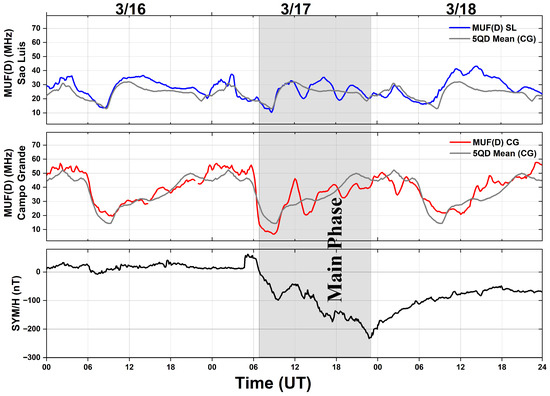

Figure 3.

MUF variation over Sao Luis (SL) and Campo Grande (CG) stations during the storm interval. At the top panel, the MUF variation is presented with the 5QD at Sao Luis, the middle panel shows the MUF and its 5QD curves at Campo Grande, and the bottom panel presents the Sym-H variation for the period.

During the main phase of the storm, a peak in foF2 is observed at approximately 15:00 UT. It is notable that, in general, the 5QD foF2 values (gray line) are higher at CG (4–17 MHz) than at SL (3–12 MHz) throughout the entire interval. However, at CG, the disturbed foF2 does not show significant deviations from the 5QD, indicating a more stable ionospheric response at this location compared to SL. The measurements at the two stations, which are longitudinally separated by several degrees, are out of phase due to the time zone difference of approximately 40 min. This phase difference is a result of the longitudinal variation in ionospheric dynamics, which is influenced by the local time and the geomagnetic field configuration.

Similarly, the MUF values for both stations were examined to highlight the ionospheric response during the main and early recovery phases of the storm, noting that MUF reflects both foF2 and the path geometry through and, therefore, may diverge from foF2 variability. Figure 3 presents MUF variations at SL and CG from 16 to 18 March. On 17 March, the main phase of the storm, MUF values at SL show a marked enhancement relative to the 5QD baseline, particularly during the afternoon and evening hours. At CG, by contrast, MUF values remain closer to the quiet-time average, indicating a more subdued response. On 18 March, both stations exhibit variability in MUF, with CG showing elevated values during the pre-dawn to early afternoon hours (05:00–17:00 LT), a feature that is less pronounced at SL. The average 5QD MUF values range from 15 to 52 MHz at CG and 12 to 33 MHz at SL. At SL, MUF tends to be lower in the morning hours and higher in the afternoon and evening, while CG shows more consistent MUF behavior across the day. Overall, the higher MUF values at CG are attributed to the electrodynamics of the equatorial and low-latitude ionosphere, particularly the development of the EIA.

It is important to clarify, however, that the enhanced MUF at CG is not solely due to the F2 layer peak but also reflects contributions from the EIA, a distinct ionospheric feature formed by the equatorial fountain effect. While the hmF2 is the altitude of maximum electron density in the ionosphere and is influenced by local photochemical production and vertical plasma drifts, the EIA results from large-scale plasma redistribution driven by eastward electric fields and geomagnetic field geometry ( drift), which lifts equatorial plasma and redistributes it poleward along magnetic field lines. In the South American sector, this drift is further intensified by the SAMA, where the weak geomagnetic field enhances vertical drift magnitudes compared to sectors without SAMA effects. The crests of the EIA, typically located around ±15° magnetic latitude, are regions of enhanced electron density but are not collocated with the F2 peak. Hence, storm-induced variations in electric fields (e.g., PPEF and DDEF) can affect the F2 peak and EIA differently, leading to distinct impacts on MUF at equatorial versus low-latitude stations. Neutral winds and geomagnetic latitude further modulate these differences, with off-equatorial CG less directly exposed to PPEF-driven vertical drifts.

To investigate the effects of the geomagnetic storm on the ionospheric parameters, the foF2 and MUF values during the storm interval were compared to their 5QDs. At SL, the foF2 and MUF values were higher than the 5QD on 16 March from 12:00 to 23:00 UT, on 17 March from 14:00 to 17:00 UT, and on 18 March from 10:00 to 22:00 UT. In addition to the graphical time-series (Figure 2 and Figure 3), we also provide a quantitative summary of storm-time deviations in Table 2. This table presents the normalized percentage-point deviations of foF2 and MUF from their quiet-day baselines at both São Luis and Campo Grande, allowing for direct comparison of the statistical magnitude of variations across the different storm phases.

Table 2.

Maximum percentage-point deviations of foF2 and MUF relative to time-matched 5QD means, after normalizing each day’s series by its daily maximum (HPV for the current day; HMV for the 5QD mean). Phase intervals follow the definitions in Section 3.1.

The percentage-point deviation was computed as:

where is the current-day parameter value at time t, is the current-day daily maximum (peak) of that parameter, is the time-matched 5QD mean, and is the daily maximum (peak) of the 5QD mean. This metric reports percentage-point differences after normalizing each time series by its daily maximum, which reduces biases from diurnal amplitude. The maximum values for foF2 and MUF within each storm phase are summarized in Table 2.

On 17 March, the MUF at the SL station exhibited two prominent reductions relative to the 5QD baseline, occurring near 13:00 UT and 18:00 UT. These dips are likely associated with the influence of PPEFs, which rapidly uplift the F-region plasma. Although this uplift increases the F-layer height, the associated rarefaction lowers peak electron density (NmF2), thereby reducing MUF. This mechanism explains why MUF exhibited significant dips at SL despite simultaneous upward hmF2 variations.

At the CG station, MUF variations were also observed during the same interval, but they were less pronounced and more consistent with the 5QD trend as shown in Figure 3. This contrast suggests that the equatorial station (SL) is more directly and strongly affected by the PPEF-driven vertical plasma transport than the off-equatorial CG station, reflecting latitudinal differences in storm-time electrodynamic coupling.

The observed increase in foF2 and MUF at SL during the storm aligns with the findings of Venkatesh et al. [13], who reported enhanced ionization in the equatorial ionosphere during geomagnetic storms due to the PPEF. However, the lack of significant deviations in foF2 and MUF at CG contradicts some previous studies, such as Astafyeva et al. [22], which reported significant increases in ionospheric parameters at low-latitude regions during geomagnetic storms. This discrepancy may be attributed to the unique electrodynamic conditions of the Brazilian sector, further intensified by SAMA effects that amplify upward ExB drifts and enhance the responsiveness of the EIA.

The MUF values at SL showed significant increases during the storm, particularly in the afternoon and evening hours. However, two notable decreases in MUF were observed on 17 March, coinciding with PPEF events. These decreases are attributed to the rapid uplift of the F-region height, which reduces the MUF available for communication. At CG, the MUF values were consistently higher than at SL, reflecting the influence of the EIA, which enhances ionization at the anomaly crests. The comparatively higher and steadier MUF at CG, linked to EIA crest development, aligns with observations of EIA expansion and even crest merging during extreme forcing [26], underscoring that MUF may diverge from foF2 when storm-time electrodynamics modifies path geometry and effective reflection heights.

The observed decreases in MUF at SL during PPEF events are consistent with the findings of Bhaskar and Vichare [16], who noted that PPEF-induced uplifts in the F-region height can lead to a reduction in MUF. In the Brazilian sector, these localized PPEF effects are further amplified by the SAMA, where the weak geomagnetic field increases vertical drift magnitudes. The magnitude and timing of the MUF decrease at SL, therefore, providing new insights into how SAMA-augmented PPEF dynamics influence storm-time HF propagation in the equatorial ionosphere. The higher MUF values at CG compared to SL are consistent with the well-documented behavior of the EIA, which enhances ionization at the crests of the anomaly while reducing it at the equator. This reinforces the distinction between F2 peak behavior and EIA-related enhancements, as the two regions are controlled by different electrodynamic mechanisms and exhibit distinct spatial and temporal responses during geomagnetic disturbances. The greater responsiveness of the Brazilian EIA compared to other longitude sectors reflects both SAMA-induced amplification of drifts and the region’s steep magnetic inclination and composition gradients.

To distinguish the different physical processes and altitudinal structures associated with the F2 peak and the EIA, particularly in the context of their response to geomagnetic storm forcing, we consider the hmF2 variable. We know that hmF2 corresponds to the altitude of maximum electron density and is primarily governed by the production of O+ ions through photoionization, balanced by loss through recombination and vertical transport [1]. In contrast, the EIA arises from the equatorial fountain effect, which is stronger in the American sector because of the SAMA. Here, plasma is lifted at the magnetic equator by a stronger upward drift and then diffuses poleward along magnetic field lines, creating two off-equatorial crests in electron density. As detailed in Krall et al. [46], the altitude and intensity of the EIA are determined by a dynamic balance of vertical drift, field-aligned diffusion, and neutral wind interactions, distinct from the processes controlling the F2 peak. These contrasts differ from Asian sector results [22] showing stronger low-latitude enhancements, and African studies [23] where crest merging dominated MUF variability. The Brazilian sector’s steeper magnetic inclination, neutral composition gradients, and SAMA effects contribute to its distinct MUF response.

During geomagnetic storms, these two regions can exhibit markedly different responses due to the influence of storm-time electric fields. PPEFs may induce rapid uplifts in the F2 peak and intensify or/and shift the EIA crests, whereas DDEFs can produce delayed, often opposing, effects. The asynchronous and spatially varying responses of these regions to the same storm-time drivers present the complexity of ionospheric electrodynamics in equatorial and low-latitude sectors like Brazil.

As the first study to investigate the percentage deviations in foF2 and MUF during a geomagnetic storm in the Brazilian sector, this work highlights the varying responses of the equatorial and low-latitude ionosphere. The percentage deviations in foF2 and MUF during the storm (Table 2) reveal that at SL, the deviations were more pronounced during the main and recovery phases of the storm, while at CG, the deviations were smaller, indicating a more subdued response to the storm. This novel approach provides a quantitative measure of the storm’s impact on ionospheric parameters, offering new insights into the localized effects of geomagnetic disturbances. To further understand the underlying mechanisms driving these variations, we now turn to the calculation of the MUF, which incorporates the effects of Earth’s spherical geometry and ionospheric refraction, as well as the influence of geomagnetic disturbances on the F2 layer.

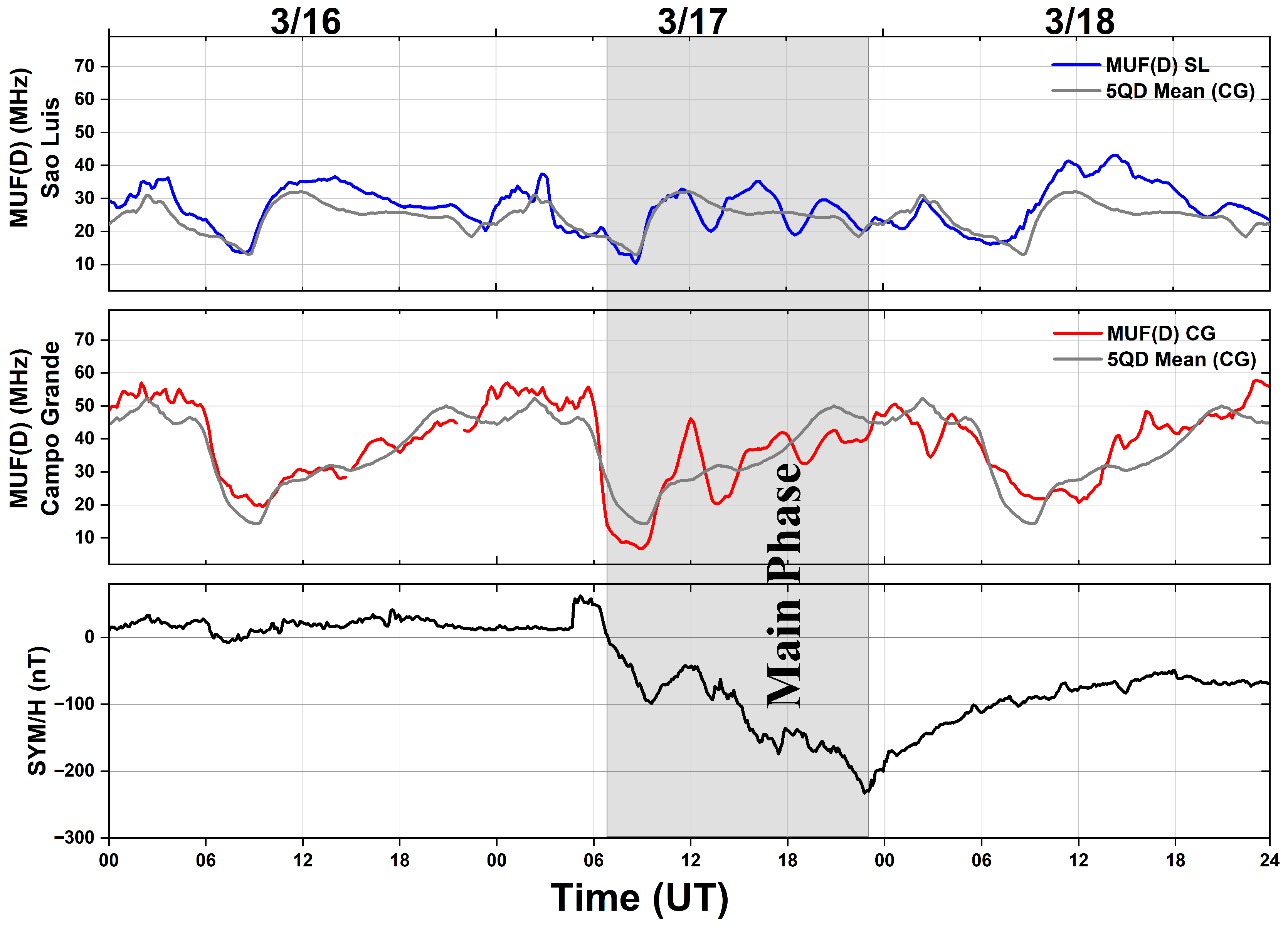

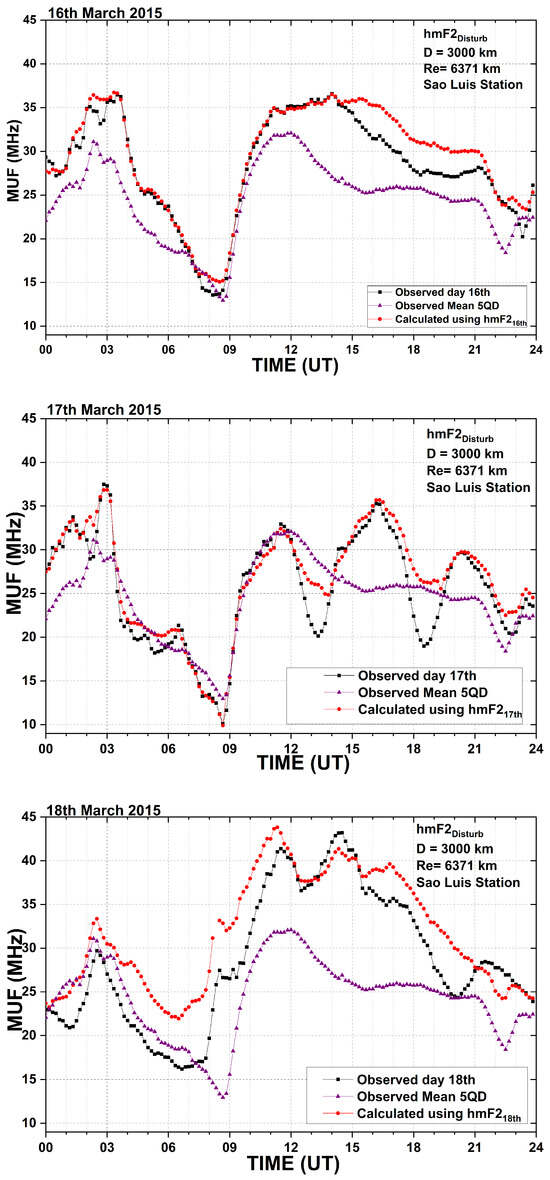

3.3. Maximum Usable Frequency—Observed and Calculated

The methodology used to compute the “Calculated MUF” in this study is detailed in Section 2. Briefly, MUF was estimated using the propagation factor (M-factor) approach described by Souza et al. [35], which accounts for the Earth’s spherical geometry and ionospheric refraction. This method was applied both for quiet and disturbed geomagnetic conditions to evaluate the impact of storm-induced F2 layer uplift. For quiet days, the M-factor was calculated using the mean hmF2 from the five quietest days (5QD) in March 2015. To assess storm-time effects, the same M-factor calculation was repeated using the disturbed hmF2, while keeping the observed foF2 constant. This relative comparison isolates the influence of F2 layer height variability on MUF during the geomagnetic storm.

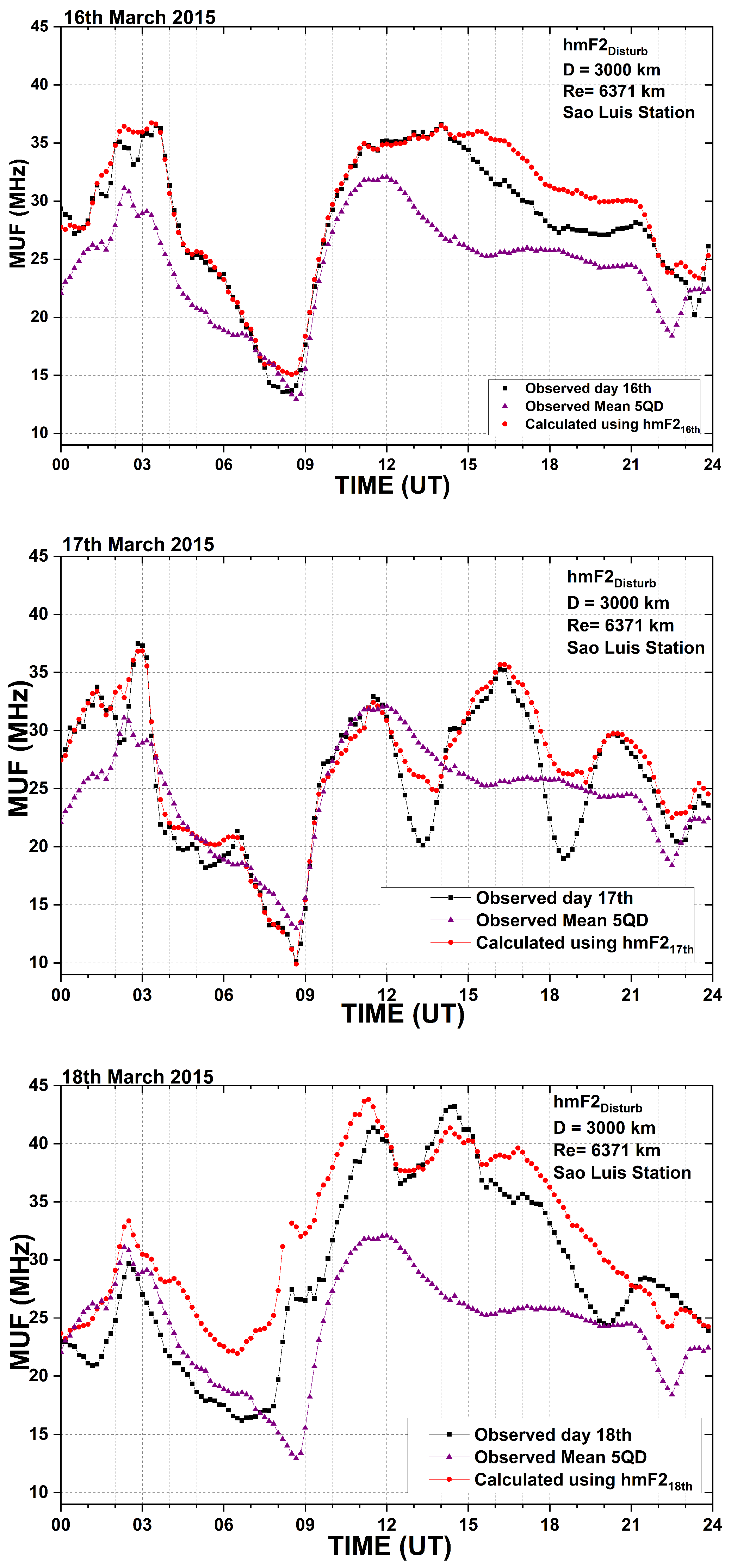

Figure 4 shows the MUF variation for the equatorial region, SL, for the day before the storm, 16 March (top panel), the main phase of the storm, 17 March (middle panel), and the first day of the recovery phase, 18 March (bottom panel). It was observed that the calculated MUF for the quiet day of 16 March presents good agreement with the observed values for most of the day, except for the interval 11:00 to 15:00 UT (08:00–12:00 LT). In general, the calculated MUF values are higher than the 5QD MUF values. For the main phase of the storm, 17 March, a deep depletion in the calculated and observed MUF was observed at around 13:00 UT and 18:00 UT (10:00 LT and 15:00 LT), compared to the 5QD MUF values. After MUF calculations considering the effects of spherical geometry (blue line) and geomagnetic storm effects on the F-layer peak height, it was observed that the geomagnetic storm decreased MUF in some intervals, but not as significantly as shown in the observed MUF, particularly around 13:00, 18:00, and 23:00 UT. One interesting feature in the middle panel of Figure 4 is that the MUF values calculated using only the spherical geometry approach show three significant differences compared to the directly obtained ionogram data on 17 March, around 13:00, 19:00, and 22:30 UT. The observed decreases in the directly obtained MUF values during the first two intervals (13:00 UT and 19:00 UT) are believed to be caused by PPEF events, as reported by Venkatesh et al. [13]. However, the observed decrease during the last interval (22:30 UT) is associated with the Pre-Reversal Enhancement (PRE). Finally, the minimum value of all the different forms of MUF was observed on 17 March, during the main phase of the geomagnetic storm, as presented in Figure 4. The observed decreases in MUF during PPEF events at SL are consistent with the findings of Bhaskar and Vichare [16]. In these cases, although PPEF uplift increases the F2-layer height, the associated plasma rarefaction lowers NmF2, leading to a reduction in MUF. This mechanism accounts for the significant observed dips despite upward hmF2 variations. The magnitude of these decreases and their precise timing provide new insights into the localized effects of PPEF in the Brazilian equatorial region. The higher MUF values at CG compared to SL are consistent with the well-documented behavior of the EIA, which enhances ionization at the crests of the anomaly while reducing it at the equator.

Figure 4.

Observed and calculated MUFs at SL station for 16, 17, and 18 March 2015. The top panel presents the MUF for day 16, the 5QD MUF, and the two calculated MUFs (using 5QD hmF2 and hmF2 for day 16). The middle panel shows the MUF for day 17, the 5QD MUF, and the two calculated MUFs (using 5QD hmF2 and hmF2 for day 17). Finally, the bottom panel displays the MUF for the day 18, the 5QD MUF, and the two calculated MUFs (using 5QD hmF2 and hmF2 for the day 18).

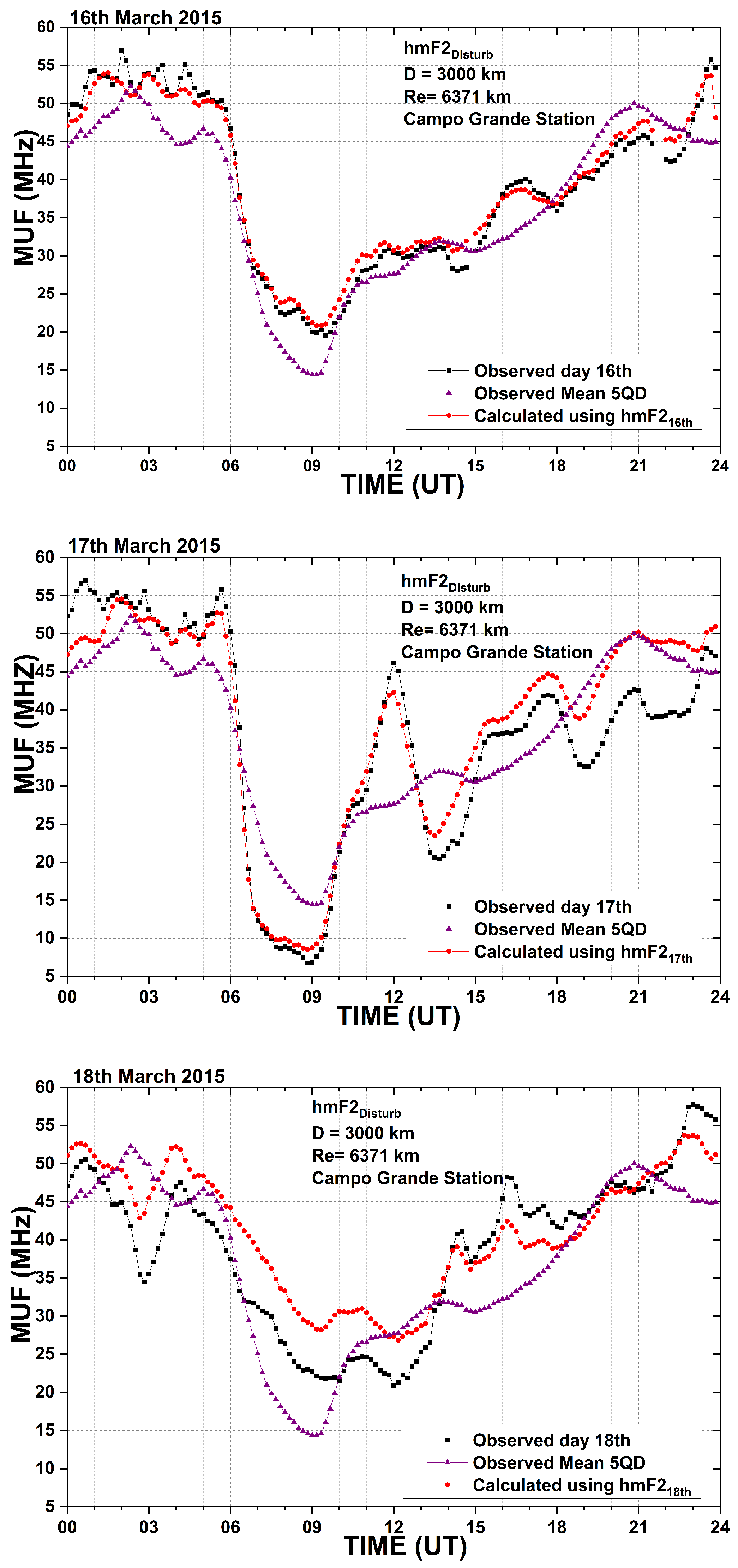

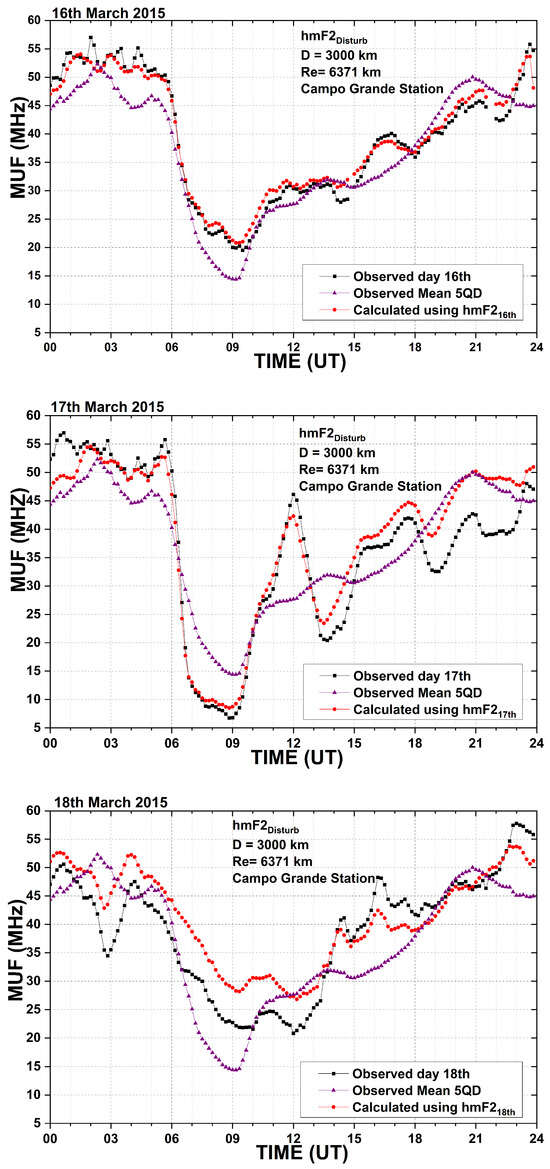

Similarly, Figure 5 shows the MUF variation at the CG station: the current day, the 5QD MUF, and the two calculated MUF values (using 5QD hmF2 for spherical geometry calculation and the current day hmF2). The top panel presents the MUF for 16 March, the middle panel for 17 March, and the bottom panel for 18 March. From Figure 5, it can be seen that the MUF values calculated using the ionospheric effect and spherical geometry corrections (blue and red curves) show good agreement with the directly observed MUF of the three disturbed days (black curves). However, there are significant variations between the calculated MUF values (blue and red curves) and the directly observed 5QD MUF values (purple curves). These differences are most pronounced around 11:00–23:00 UT on 16 March, 14:00–17:00 UT and 20:00–22:00 UT on 17 March, and 08:00–24:00 UT on 18 March. This significant disagreement is believed to be associated with the effect of geomagnetic disturbances. Additionally, the MUF values calculated using the ionospheric effect and spherical geometry corrections (blue and red curves) show good agreement with the directly observed MUF of the three disturbed days (black curves). However, there are significant variations between the calculated MUF values and the observed disturbed day MUF values (blue, red, and black curves) and the directly observed 5QD MUF values (purple curves). Similar to the SL results, the minimum value of all the different forms of the MUF was observed on 17 March, during the main phase of the geomagnetic storm, as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The same as Figure 4, but for the CG station.

While the observed agreement between the calculated and directly observed MUF values demonstrates the importance of considering Earth’s spherical geometry and ionospheric refraction in MUF calculations, the disagreement between the calculated and 5QD MUF values highlights the complex effects of geomagnetic disturbances on ionospheric parameters. This discrepancy may be attributed to the unique electrodynamic conditions of the Brazilian sector, where the EIA and other localized processes play a significant role in modulating ionospheric behavior. In particular, the anomalously weak geomagnetic field of the SAMA enhances the vertical drift, making the Brazilian EIA more active and responsive than in other longitude sectors. The analysis of the observed and calculated MUF values provides a foundation for understanding the Brazilian equatorial ionospheric response to the geomagnetic storm. In the following subsection, we examine the ionospheric behavior on the day before the storm commencement, focusing on the variations in foF2, hmF2, and MUF to establish a baseline for comparison with the storm period.

3.4. Ionospheric Response on the Day Before the Storm Commencement

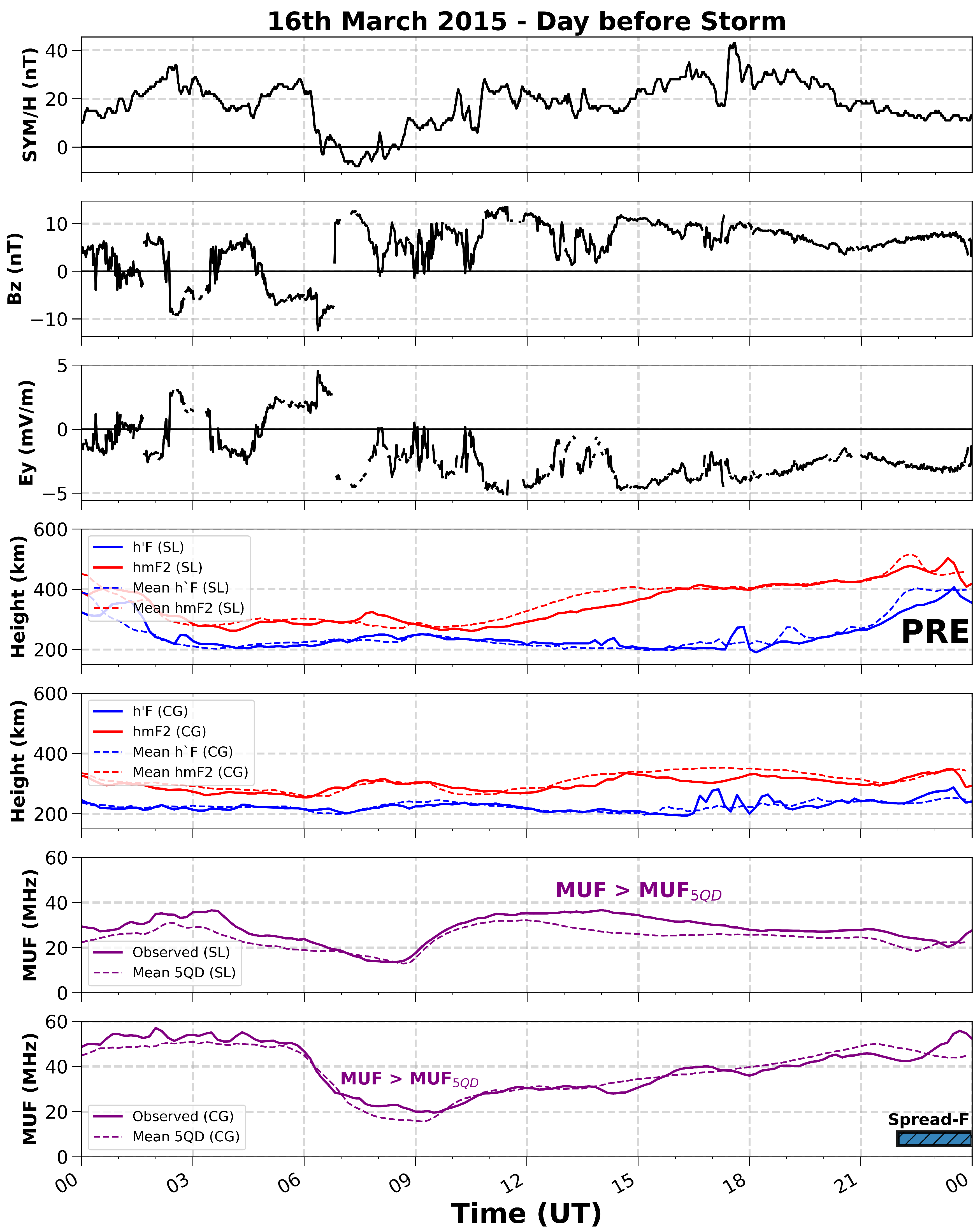

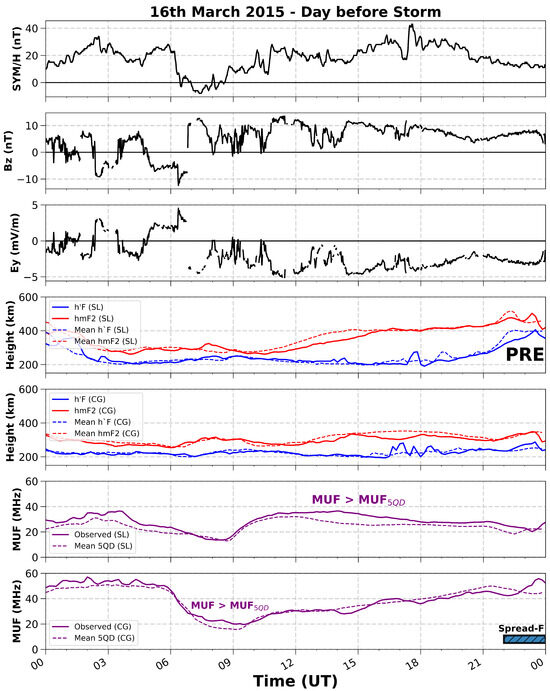

The 16 of March 2015, the day before the storm, was examined to characterize the pre-storm ionospheric conditions. Figure 6 displays, from top to bottom: the Sym-H index (nT), the vertical component of the interplanetary magnetic field Bz (nT), the interplanetary electric field Ey (mV/m), the virtual bottom height of the F-layer (h’F), the F-layer peak height (hmF2), and the MUF (observed and calculated from mean hmF2) at SL and CG, alongside their corresponding 5QD baselines. While the Sym-H index showed no significant negative perturbation and the IMF Bz remained predominantly southward but with limited large-scale variations, fluctuations in Bz and Ey were still present. These minor variations in interplanetary conditions may influence the equatorial electric field and, thus, cannot be ignored even during relatively quiet periods.

Figure 6.

Ionospheric response on the day before the storm. From top to bottom: Sym-H index, Bz, Ey, h’F, , observed and calculated MUF at SL and CG with their respective 5QD baselines. The evening uplift in h’F and at SL around 22:00 UT corresponds to the typical pre-reversal enhancement (PRE).

The F-layer parameters (h’F and hmF2) at both stations mostly followed their 5QD reference values throughout the day. However, slight departures from the 5QD baselines were observed in MUF values, particularly during the nighttime and early morning hours (00:00–06:00 UT) at both stations. A more pronounced deviation occurred at the SL station between 13:00–16:00 UT (10:00–13:00 LT), where both the observed and calculated MUF diverged from quiet-time expectations. In addition, the evening uplift of h’F and hmF2 observed at SL around 22:00 UT (19:00 LT) is consistent with the typical PRE in the equatorial ionosphere, often associated with the onset of plasma irregularities, as indicated by the shaded bar in the bottom panel. While such variations can also occur during non-disturbed periods, the significance of this pre-storm day analysis lies in providing a quiet-time reference context for the storm-day interpretation. The uniqueness of this result lies in the careful quantification of ionospheric variability in relation to modest interplanetary changes, serving as a control baseline to contrast against storm-induced responses on 17 March.

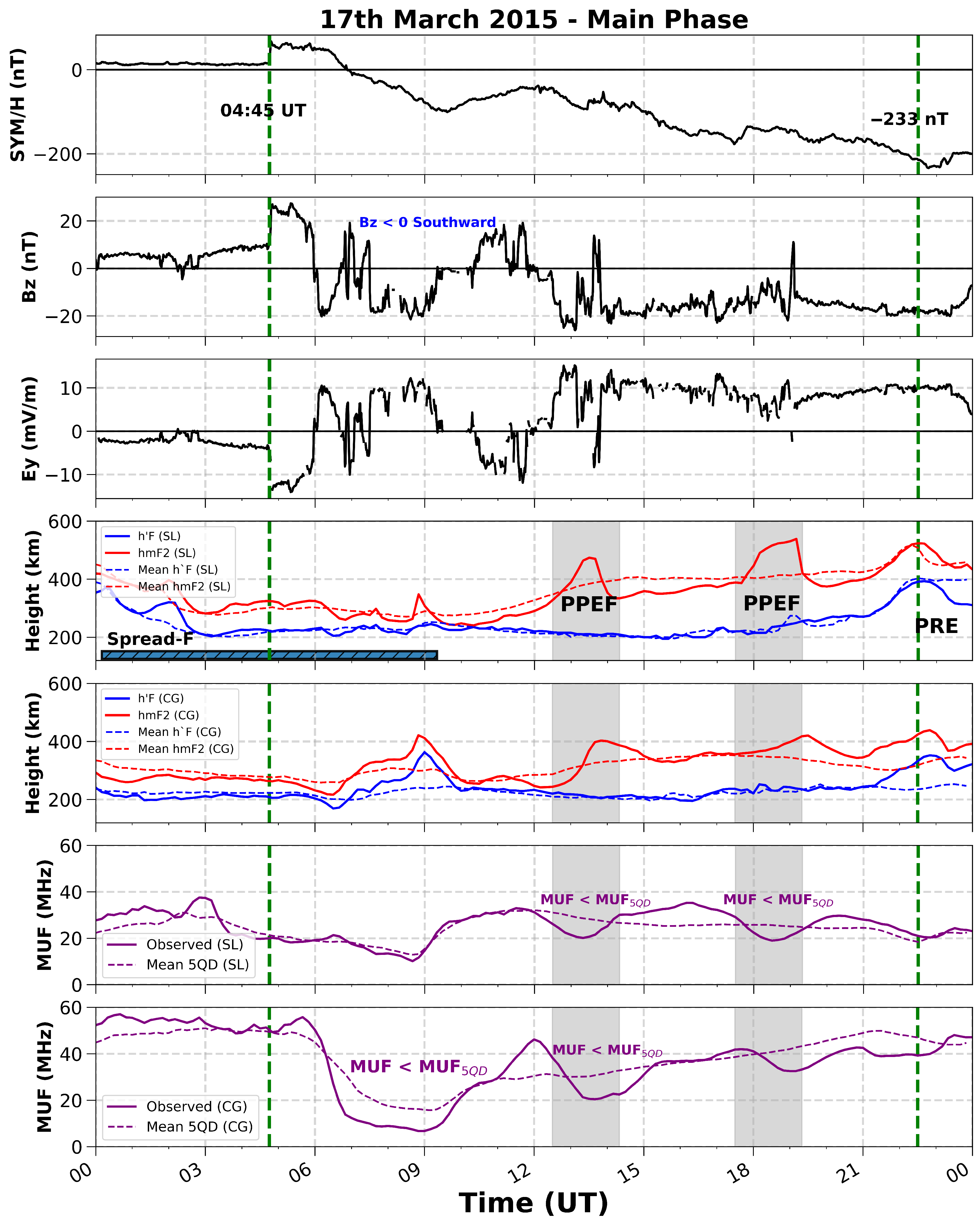

3.5. Ionospheric Response During the Main Phase of the Saint Patrick’s Day Storm

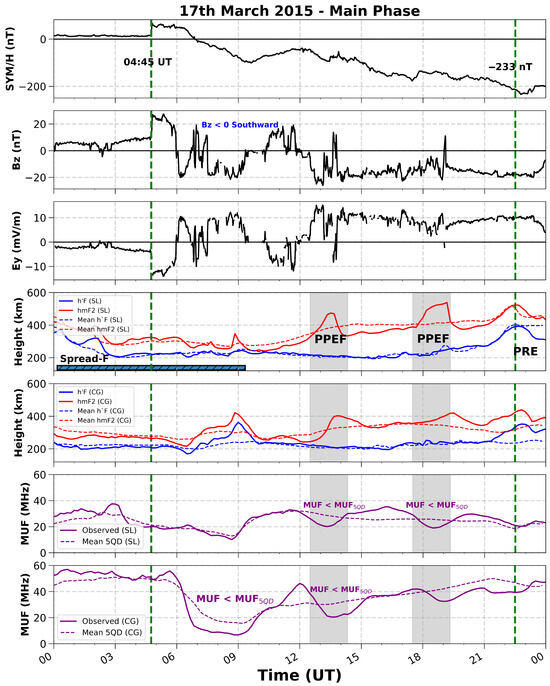

The main phase of the March 2015 geomagnetic storm occurred on the 17 known as St. Patrick’s Day. The sudden storm commencement was at exactly 04:45 UT (01:45 LT). For a better evaluation of the response of the ionosphere during this main phase of the geomagnetic Storm, Figure 7 shows the variation of the ring current index, Sym-H (nT), the vertical component of the interplanetary magnetic field, Bz (nT), the interplanetary electric field, Ey (mV/m), the F-layer virtual bottom height, h’F (km), the F-layer peak height, hmF2 (km), the MUF at SL and CG (observed and calculated with mean hmF2), as well as their 5QD for comparison. It was observed from the second and third panels that the main phase of Figure 7, the geomagnetic storm began at around 04:45 UT (01:45 LT) when the vertical component of the interplanetary magnetic field, Bz, turned northward and the Ey had a negative perturbation of about 12 mV/m. Afterward, at around past 06:00 UT (∼03:00 LT), the Bz turned southward, and the Sym-H index started decreasing to negative values until 23:00 UT, when it reached its minimum value (end of a long main phase), with no evident ionospheric response during the first hours of the main phase. The extended duration of this main phase, spanning nearly 18 h, provided sufficient time for both PPEFs and DDEFs to evolve and interact. This long-lasting energy input into the high-latitude thermosphere would likely initiate wind-driven dynamo effects, particularly during the second half of the main phase. However, at around 13:00 UT (10:00 LT), it is possible to see a negative turning of Bz (reconnection processes in progress), while Ey turns to positive values (westward dawn-to-dusk electric field). The ionospheric effects of the southward turning of Bz during this main phase can be seen in the fourth and fifth panels of Figure 7. At SL, the F-layer virtual height, h’F does not present any abrupt oscillations or deviation from its 5QD, while the F-layer peak height, hmF2 presents some uplifts in comparison to its 5QD. The first one was observed at around 09:00 UT (06:00 LT), both in SL and CG. However, as this is the interval when the ionization starts to increase by solar radiation, it may be an apparent uplift. Notice that there was no clear effect on MUF in SL (MUF ∼ 5QD MUF), while MUF is lower than the 5QD MUF in CG. This discrepancy between SL and CG indicates that the electrodynamic forcing was not uniform across latitudes. The weaker response at CG suggests that PPEF alone may not fully explain the ionospheric behavior at off-equatorial locations, and additional mechanisms, such as neutral wind-driven DDEF, may have played a role in modulating the plasma environment at CG during this period.

Figure 7.

Ionospheric response during the main phase of the Saint Patrick’s Day geomagnetic storm on 17 March 2015. Panels show, from top to bottom, Sym-H index, Bz, Ey, h’F, , and observed and calculated MUF at SL and CG with their respective 5QD baselines.

It is significant to point out that there were two marked elevations in hmF2 (swift ascents) from its 5QD at approximately 13:00 and 14:00 UT. In local time, these occurred at 09:00 and 11:00 LT, attaining altitude peaks of 465 km and roughly 520 km, respectively. The first rapid F-layer peak height uplift suggests the occurrence of enhanced vertical upward drift at the equatorial region, probably caused by eastward PPEF episodes during periods when (southward) and . The second significant hmF2 uplift during the main phase of the St. Patrick’s Day storm happened around local noon 18:00 UT (15:00 LT) when the Bz turned southward with a strong negative value of about −25 nT with Ey positive, indicating the second occurrence of eastward PPEF. However, given that the geomagnetic storm had been ongoing for over five hours by this time, it is also possible that the DDEF began to contribute to the observed uplifts later on. While the rapid enhancement around 13:00 UT aligns with a typical PPEF response, the later uplift near 18:00–19:00 UT may reflect a combination of PPEF and developing DDEF influences, consistent with storm-time thermospheric wind circulation effects described in previous studies [40]. It can be seen that at these time periods, the MUF experienced a significant decrease in its value compared to its reference 5QD MUF (gray line). This deviation was around , which means a potential loss or spurious effects in the radio communication at these times. This implies that during the event of PPEF, the radio communication sector within the station’s geographical region will experience loss or failure of radio signal links, because of the lower value of MUF (during the storm compared to its quiet day value), considering that MUF is the highest frequency that allows reliable long-range radio communication between two points.

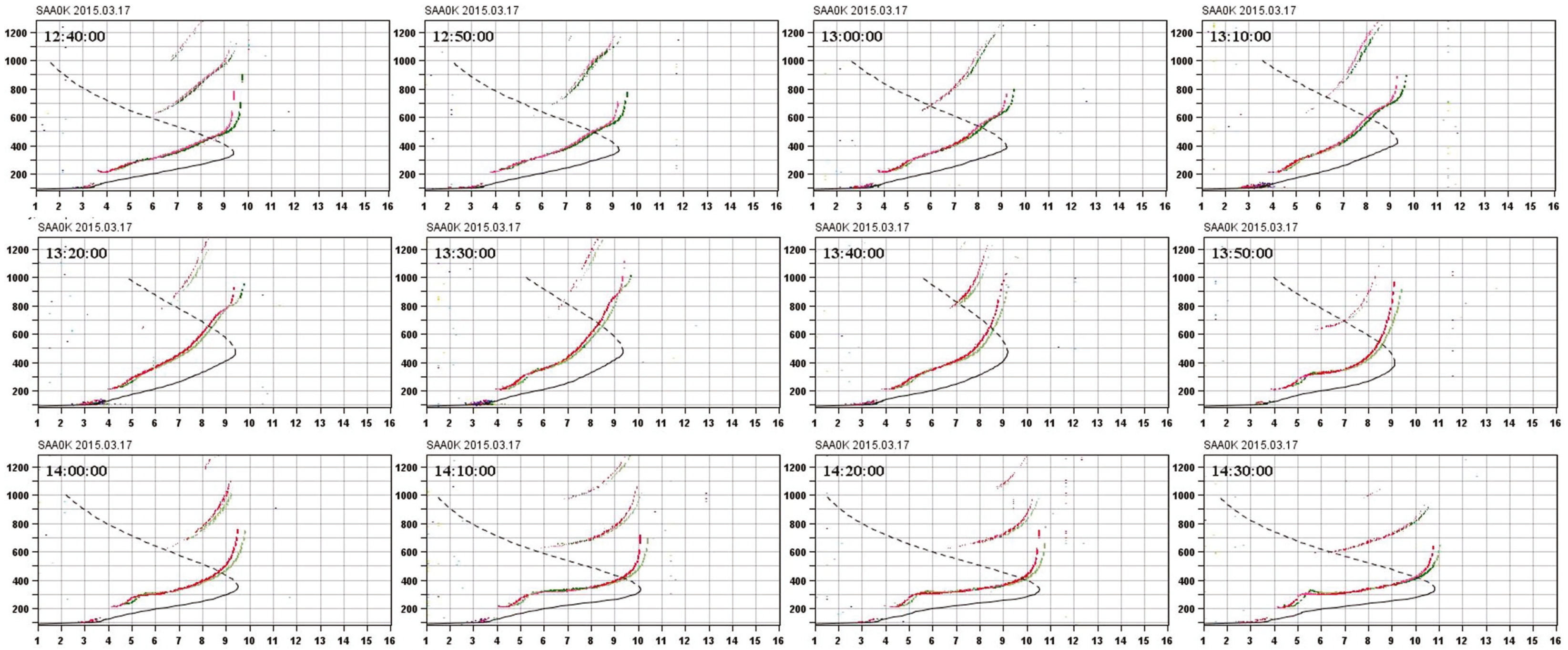

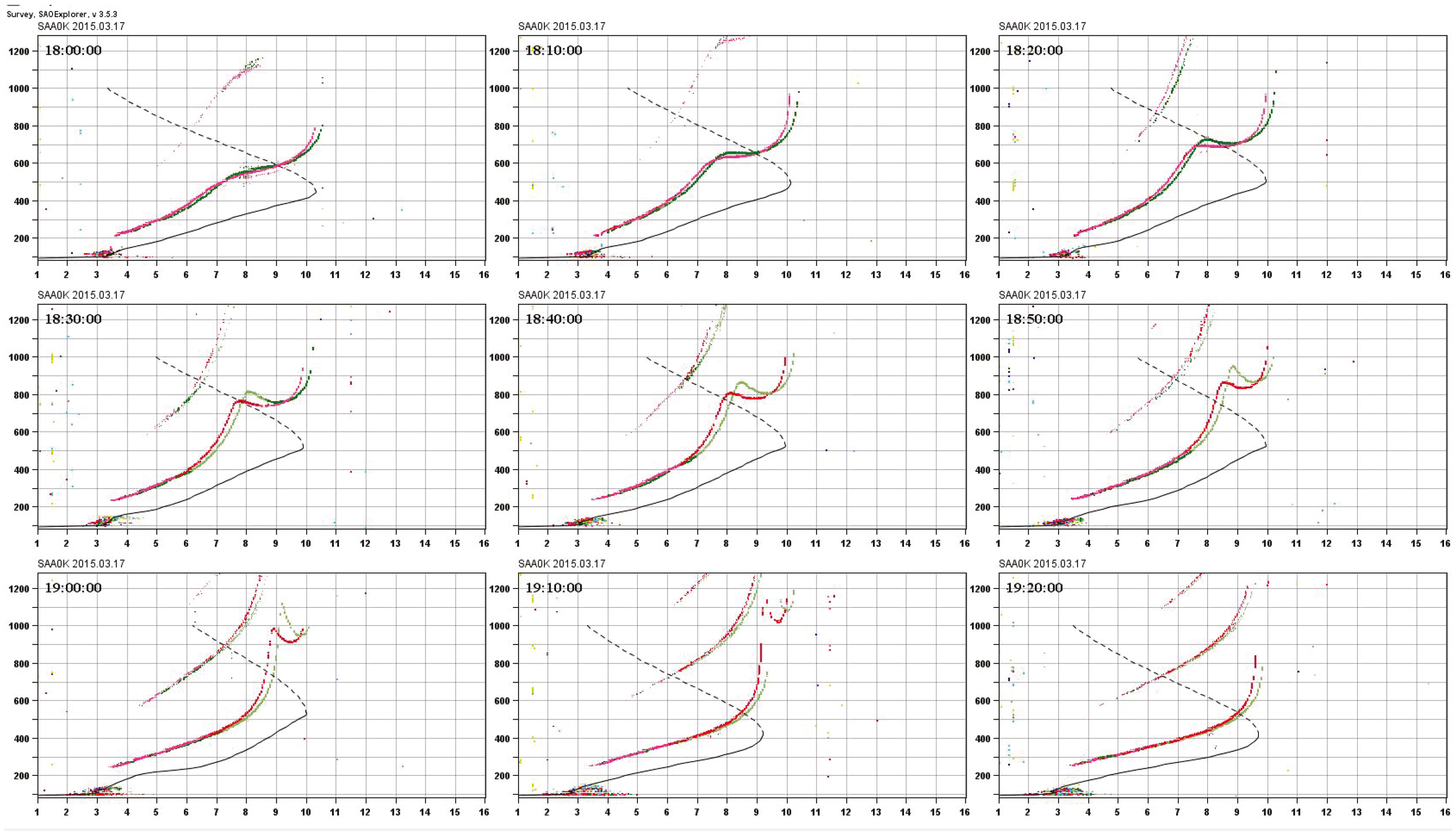

As the storm’s main phase concluded around 23:30 UT (20:30 LT), with the Sym-H index attaining its peak minimum value, the h’F at the SL station rose to an altitude of 400 km. This altitude is comparable to its 5QD reference, suggesting that the storm neither amplified nor suppressed the PRE. Notably, during the initial two PPEF events, evidence of an F3-layer was observed. In the course of the two PPEF episodes that occurred during the main phase of the St Patrick’s Day storm, the F2-layer peak height experienced a rapid upward lift. At around 12:40 UT, when the peak height of the F2-layer was rising, it was simultaneously redistributing and forming a new layer, known as the F3 layer. Figure A1 shows that the new F3 layer continued to drift upward until around 13:30 UT, after which it vanished towards the end of the PPEF events. In addition, Figure A2 shows that the equatorial ionosphere exhibited the same response during the second PPEF event. The new F3 layer reached its maximum altitude between 18:10 UT and 19:10 UT, before dissipating at 19:20 UT. As stated by Venkatesh et al. [13], Balan et al. [47,48], this redistribution of the usual F2 layer into F2 and F3-layers is a consequence of the enhanced eastward zonal electric field that accompanied the first and second PPEF episodes, thus, demonstrating that in the Brazilian equatorial ionosphere, there is a substantial augmentation of the zonal electric field during the event of PPEF. The unusually strong uplifts observed are also consistent with SAMA-augmented drifts: in the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly region, the geomagnetic field B is anomalously weak, so that the total vertical drift, proportional to , becomes much larger than in other longitude sectors. This explains why PPEF episodes in the Brazilian sector drive unusually strong uplifts and F3-layer formation. The formation of the F3 layer during the storm provides further evidence of the complex ionospheric dynamics driven by PPEF, which can significantly impact radio wave propagation and communication systems.

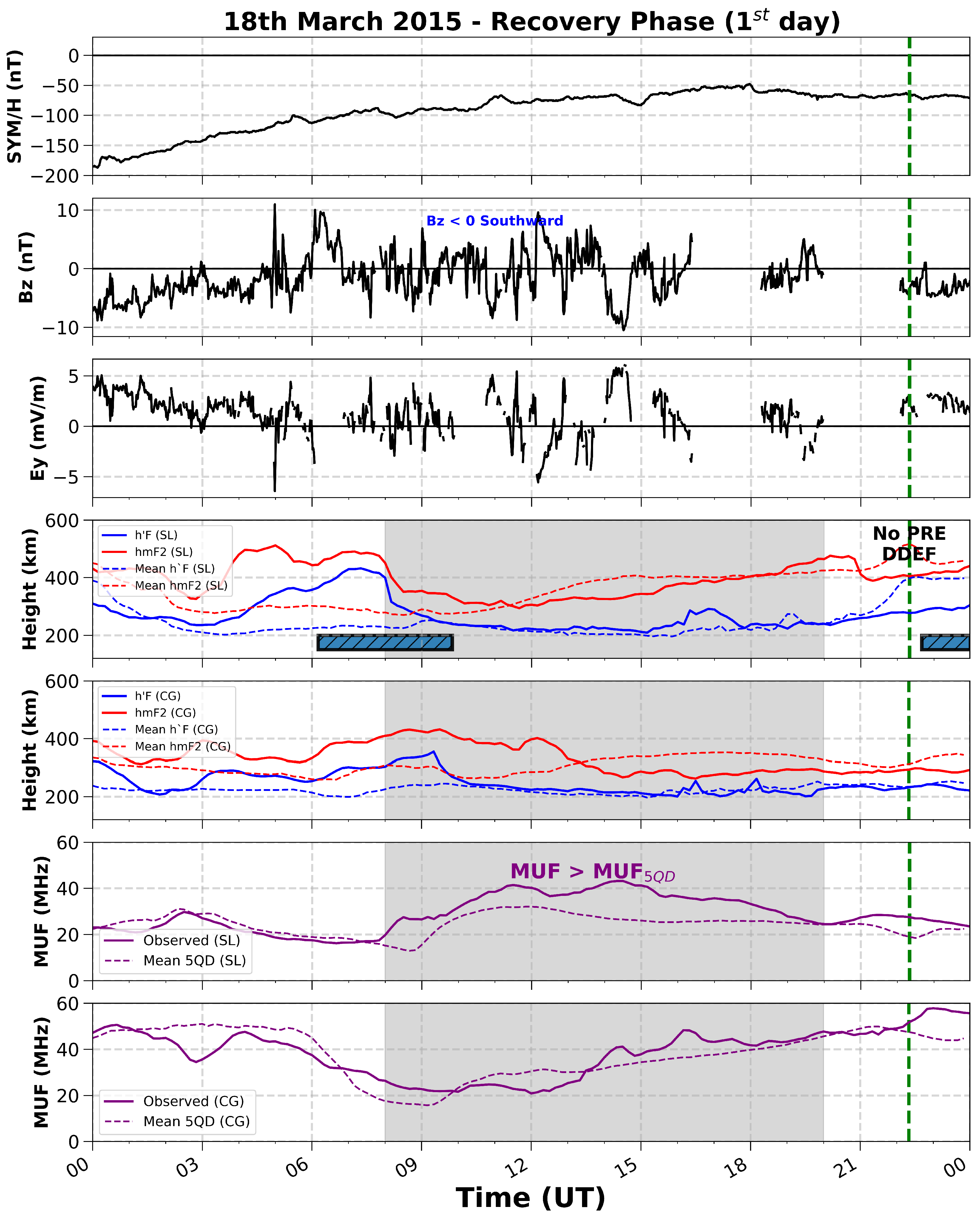

3.6. Ionospheric Response on the 1st Day of the Storm’s Recovery Phase

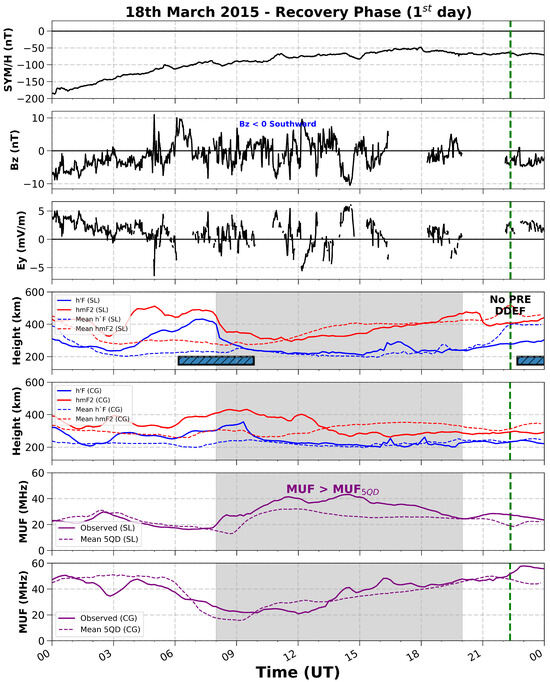

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the ionospheric response to the Saint Patrick’s Day storm, we extend our analysis to the recovery phase, which exhibited an unusually prolonged duration compared to other ICME-driven storms. The extended recovery phase can be attributed to the persistent negative Sym-H values, which did not return to their reference quiet-day levels until 25 March, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. During this interval, an increase in solar wind speed (Vsw ≤ 700 km/s) was observed, as depicted in panel e of Figure 1, alongside a CIR signature marked by a rise in Np on 17 March. These solar parameters, particularly the peaks in Vsw and Np, are indicative of HSSWS originating from solar coronal holes. In this case, the CIR was likely embedded within the ICME structure, followed by HSSWS, which collectively contributed to the extended recovery phase.

Figure 8 shows the variation of the ring current index, Sym-H (nT), the vertical component of the interplanetary magnetic field, Bz (nT), the interplanetary electric field, Ey (mV/m), the F-layer virtual bottom height, h’F (km), the F-layer peak height, hmF2 (km), as well as the MUF (observed and calculated with mean hmF2) at SL and CG stations, along with their 5QDs. Between 09:00 and 15:00 UT (06:00–12:00 LT), Bz and Ey exhibited notable oscillations, albeit with lower magnitudes compared to the main phase. However, no significant PPEF episodes were observed during this period. The MUF over SL exceeded its 5QD values from 09:00 to 18:00 UT (06:00–15:00 LT), while at CG, higher MUF values were recorded in the afternoon (15:00–16:00 UT, 12:00–13:00 LT). The elevated MUF values at SL may be attributed to weaker vertical downward vertical drifts, potentially influenced by a DDEF with westward polarization (Ey westward).

A notable feature of this day was the likely occurrence of DDEF at SL during the post-sunset period (22:30 UT, 19:30 LT), as suggested by the decrease in h’F and hmF2 relative to their 5QDs. At this time, a mild southward turning of Bz and a positive Ey were observed, but no clear PRE was detected at ∼23:00 UT (20:00 LT). This suppression of PRE may be linked to the effects of DDEF, although further investigation using equatorial electrojet data is required to confirm this hypothesis.

4. Conclusions

The comprehensive analysis of the ionospheric response to the 2015 Saint Patrick’s Day geomagnetic storm provides valuable insights into the complex dynamics of the equatorial and low-latitude ionosphere under extreme space weather conditions. The storm, driven by an ICME and followed by a CIR and HSSWS, exhibited a prolonged recovery phase, lasting approximately eight days. This extended recovery phase was characterized by persistent negative Sym-H values and enhanced solar wind speeds, highlighting the significant influence of solar wind-magnetosphere interactions on geomagnetic storm dynamics.

During the main phase of the storm, the ionosphere exhibited pronounced responses, particularly in the equatorial region. The southward turning of the interplanetary magnetic field () and the associated eastward PPEF led to rapid uplifts in the F2-layer peak height () and the formation of an F3 layer, as observed at the SL station. These phenomena, driven by enhanced eastward zonal electric fields, underscore the critical role of PPEF in modulating equatorial ionospheric behavior during geomagnetic storms. The observed decreases in the MUF during PPEF events further emphasize the impact of storm-induced electric fields on radio wave propagation and communication systems. The recovery phase of the storm revealed additional complexities, including the likely occurrence of a DDEF at SL during the post-sunset period. The suppression of the PRE and the associated decrease in h’F and suggest that the westward DDEF played a significant role in modulating ionospheric dynamics during this phase. However, further investigation using equatorial electrojet data is necessary to confirm these findings and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

The comparative analysis of ionospheric parameters at the equatorial (Sao Luis, SL) and low-latitude (Campo Grande, CG) stations revealed distinct responses to the storm. While SL exhibited significant deviations in and MUF during the storm, CG showed a more subdued response, reflecting the influence of the EIA and the unique electrodynamic conditions of the Brazilian sector. The higher MUF values at CG compared to SL further highlight the role of the EIA in enhancing ionization at the anomaly crests. The calculation of the MUF, incorporating Earth’s spherical geometry and ionospheric refraction, provided a robust framework for understanding the effects of geomagnetic disturbances on ionospheric parameters. The observed agreement between calculated and directly observed MUF values during the storm underscores the importance of considering these factors in ionospheric modeling. However, the discrepancies between calculated and 5QD MUF values highlight the need for further refinement of these models to account for localized ionospheric processes.

This study advances our understanding of the ionospheric response to geomagnetic storms in the Brazilian sector, which is situated within the SAMA, where the geomagnetic field is anomalously weak, providing new insights into the roles of PPEF, DDEF, and the EIA in modulating ionospheric behavior under the effects of the SAMA. The findings underscore the importance of considering both global and localized processes in ionospheric dynamics. The distinct Brazilian-sector response arises because the region lies within the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly, where the anomalously weak geomagnetic field enhances ExB drifts and produces unusually strong EIA variability during geomagnetic storms. Our results are consistent with recent reports of global storm impacts and EIA dynamics during extreme events [24,25,26], while providing MUF-specific, Brazil-sector constraints to guide future modeling and HF propagation studies. Cross-sector comparisons underline that while Asia and Africa show crest-enhanced MUF increases, Brazil exhibits equatorial dips linked to PPEF rarefaction, reflecting its unique electrodynamic context. Future studies will use the Global Ionosphere Thermosphere Model (GITM) configured with storm-time high-latitude electrodynamic forcing (e.g., AMIE/Weimer) and equatorial electrojet constraints to quantify the relative roles of PPEF and DDEF in setting hmF2, foF2, and MUF over the Brazilian sector. By coupling GITM outputs (electron density and drift fields) with an HF ray-tracing solver to compute MUF(D) along realistic 3000-km paths, we will directly test the mechanisms inferred from observations and reconcile path-geometry effects on MUF with storm-time changes in foF2 and layer heights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B.-G. and C.M.N.C.; methodology, O.G.N.; software, O.G.N.; validation, F.B.-G., C.M.N.C. and O.G.N.; formal analysis, O.G.N.; investigation, F.B.-G., C.M.N.C. and O.G.N.; resources, F.B.-G. and C.M.N.C.; data curation, O.G.N.; writing—original draft preparation, O.G.N.; writing—review and editing, F.B.-G., C.M.N.C. and O.G.N.; visualization, O.G.N.; supervision, F.B.-G. and C.M.N.C.; project administration, F.B.-G. and C.M.N.C.; funding acquisition, F.B.-G. and C.M.N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil, under grant number 301944/2021-0.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://www.inpe.br/climaespacial (accessed on 20 January 2020) and http://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov (accessed on 25 January 2020). No new data were created in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI) and the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB). Additionally, we thank the Space Weather Data Share of Estudo e Monitoramento Brasileiro do Clima Espacial (EMBRACE), Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE) for making the ionospheric parameters data available for this article. Other data used in this work were obtained from the NASA OMNIWeb Plus site (http://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov (accessed on 25 January 2020)). We thank the MDPI Atmosphere editor and reviewers of our manuscript for their constructive comments and suggestions, which have helped to improve this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Ionogram survey during the first PPEF episode of the St Patrick’s Day storm showing the formation of F3 layer.

Figure A1.

Ionogram survey during the first PPEF episode of the St Patrick’s Day storm showing the formation of F3 layer.

Figure A2.

Ionogram survey during the second PPEF episode of the St Patrick’s Day storm showing the formation of F3 layer.

Figure A2.

Ionogram survey during the second PPEF episode of the St Patrick’s Day storm showing the formation of F3 layer.

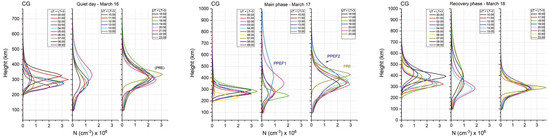

Figure A3.

Height profiles of ionospheric electron density ( cm−3) at SL on 16 March 2015 (left panel), 17 March 2015 (middle panel), and 18 March 2015 (right panel) during the geomagnetic storm. The profiles at selected Universal Times (UT = LT + 3) illustrate storm-time variations in the vertical structure of the ionosphere.

Figure A3.

Height profiles of ionospheric electron density ( cm−3) at SL on 16 March 2015 (left panel), 17 March 2015 (middle panel), and 18 March 2015 (right panel) during the geomagnetic storm. The profiles at selected Universal Times (UT = LT + 3) illustrate storm-time variations in the vertical structure of the ionosphere.

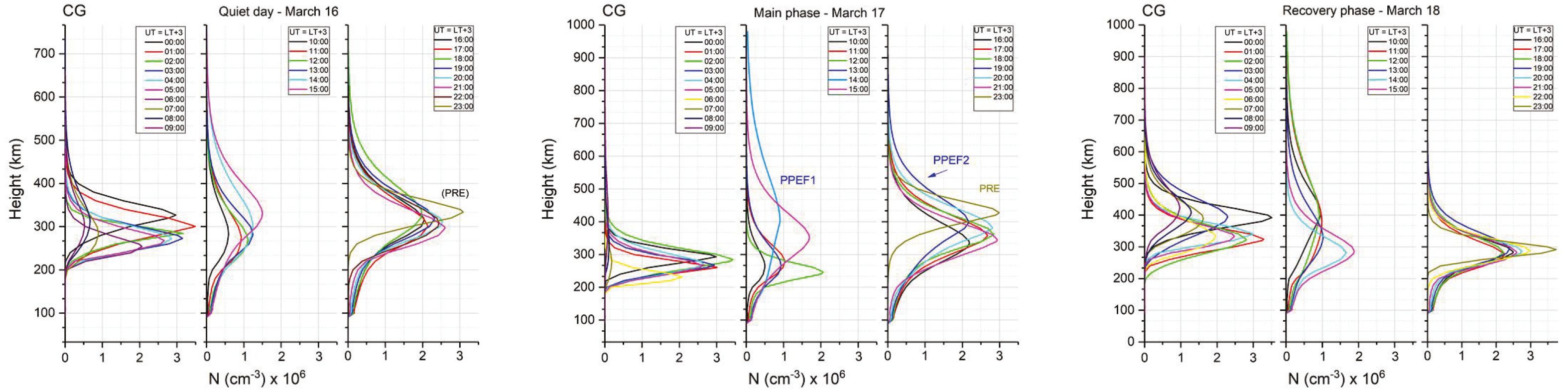

Figure A4.

Height profiles of ionospheric electron density ( cm−3) at CG on 16 March 2015 (left panel), 17 March 2015 (middle panel), and 18 March 2015 (right panel) during the geomagnetic storm. The profiles at selected Universal Times (UT = LT + 3) illustrate storm-time variations in the vertical structure of the ionosphere.

Figure A4.

Height profiles of ionospheric electron density ( cm−3) at CG on 16 March 2015 (left panel), 17 March 2015 (middle panel), and 18 March 2015 (right panel) during the geomagnetic storm. The profiles at selected Universal Times (UT = LT + 3) illustrate storm-time variations in the vertical structure of the ionosphere.

References

- Kelley, M.C. The Earth’s Ionosphere: Plasma Physics and Electrodynamics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mallios, S.A.; Pasko, V.P. Charge transfer to the ionosphere and to the ground during thunderstorms. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.G. Radio waves in the ionosphere. In Radio Waves in the Ionosphere; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hagfors, T.; Schlegel, K. Earth’s ionosphere. In The Century of Space Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 1559–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Astafyeva, E.; Zakharenkova, I.; Hozumi, K.; Alken, P.; Coïsson, P.; Hairston, M.R.; Coley, W.R. Study of the equatorial and low-latitude electrodynamic and ionospheric disturbances during the 22–23 June 2015 geomagnetic storm using ground-based and spaceborne techniques. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2018, 123, 2424–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, S.; Abdu, M.; Batista, I.; Sobral, J.; Luan, X.; Kallio, E.; Maguire, W.; Verigin, M.; Singh, V. D, E, and F layers in the daytime at high-latitude terminator ionosphere of Mars: Comparison with Earth’s ionosphere using COSMIC data. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cander, L.R.; Bamford, R.; Hickford, J. Nowcasting and forecasting the foF2, MUF (3000) F2 and TEC based on empirical models and real-time data. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Antennas and Propagation, 2003 (ICAP 2003). (Conf. Publ. No. 491), Exeter, UK, 31 March–3 April 2003; IET: London, UK, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Athieno, R.; Jayachandran, P. MUF variability in the Arctic region: A statistical comparison with the ITU-R variability factors. Radio Sci. 2016, 51, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yue, J.; Wang, W.; Qian, L.; Jian, L.; Zhang, J. A Comparison of the CIR-and CME-Induced Geomagnetic Activity Effects on Mesosphere and Lower Thermospheric Temperature. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2021, 126, e2020JA029029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Chakrabarti, S. Earth’s Ionosphere as a Gigantic Detector of Extra-terrestrial Energetic Phenomena: A Review. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1286, 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Tulasi Ram, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Otsuka, Y.; Shiokawa, K.; Sripathi, S.; Veenadhari, B.; Heelis, R.; Ajith, K.; Gowtam, V.S.; Gurubaran, S.; et al. Duskside enhancement of equatorial zonal electric field response to convection electric fields during the St. Patrick’s Day storm on 17 March 2015. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2016, 121, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.T.; Kumar, S.; Su, S.Y.; Veenadhari, B.; Ravindran, S. The influence of Corotating Interaction Region (CIR) driven geomagnetic storms on the development of equatorial plasma bubbles (EPBs) over wide range of longitudes. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 55, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.; Tulasi Ram, S.; Fagundes, P.; Seemala, G.K.; Batista, I. Electrodynamic disturbances in the Brazilian equatorial and low-latitude ionosphere on St. Patrick’s Day storm of 17 March 2015. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2017, 122, 4553–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, C.; Kelley, M.; Fejer, B.G.; Vickrey, J.; Woodman, R. Equatorial electric fields during magnetically disturbed conditions 2. Implications of simultaneous auroral and equatorial measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1979, 84, 5803–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.; Lühr, H.; Kitamura, T.; Saka, O.; Schlegel, K. Direct penetration of the polar electric field to the equator during a DP 2 event as detected by the auroral and equatorial magnetometer chains and the EISCAT radar. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1996, 101, 17161–17173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, A.; Vichare, G. Characteristics of penetration electric fields to the equatorial ionosphere during southward and northward IMF turnings. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2013, 118, 4696–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M.; Richmond, A. The ionospheric disturbance dynamo. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1980, 85, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastri, J.H. Equatorial electric fields of ionospheric disturbance dynamo origin. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Equatorial Aeronomy, Vienna, Austria, 22–27 August 1988; pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Astafyeva, E.; Zakharenkova, I.; Huba, J.; Doornbos, E.; Van den IJssel, J. Global ionospheric and thermospheric effects of the June 2015 geomagnetic disturbances: Multi-instrumental observations and modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2017, 122, 11–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, P.; Akasofu, S. A study of geomagnetic storms. Geophys. J. Int. 1978, 54, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.T.; McPherron, R.L.; Burton, R.K. On the cause of geomagnetic storms. J. Geophys. Res. 1974, 79, 1105–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astafyeva, E.; Zakharenkova, I.; Förster, M. Ionospheric response to the 2015 St. Patrick’s Day storm: A global multi-instrumental overview. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2015, 120, 9023–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, B.; Rodríguez-Zuluaga, J.; Alazo-Cuartas, K.; Kashcheyev, A.; Migoya-Orué, Y.; Radicella, S.; Amory-Mazaudier, C.; Fleury, R. Middle-and low-latitude ionosphere response to 2015 St. Patrick’s Day geomagnetic storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2016, 121, 3421–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojilova, R.; Mukhtarov, P.; Pancheva, D. Global Ionospheric Response During Extreme Geomagnetic Storm in May 2024. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, R.; Shah, M.; Tariq, M.A.; Calabia, A.; Melgarejo-Morales, A.; Jamjareegulgarn, P.; Liu, L. Ionospheric–Thermospheric Responses to Geomagnetic Storms from Multi-Instrument Space Weather Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aa, E.; Chen, Y.; Luo, B. Dynamic Expansion and Merging of the Equatorial Ionization Anomaly During the 10–11 May 2024 Super Geomagnetic Storm. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Guo, C.; Yue, Q.; Zhang, S.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, J. A Novel Ionospheric Disturbance Index to Evaluate the Global Effect on BeiDou Navigation Satellite System Signal Caused by the Moderate Geomagnetic Storm on May 12, 2021. Sensors 2023, 23, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabati, A.; Jazireeyan, I.; Alizadeh, M.; Pirooznia, M.; Flury, J.; Schuh, H.; Soja, B. Analyzing the Ionospheric Irregularities Caused by the September 2017 Geomagnetic Storm Using Ground-Based GNSS, Swarm, and FORMOSAT-3/COSMIC Data near the Equatorial Ionization Anomaly in East Africa. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, M.A.; Batista, I.; Carrasco, A.; Brum, C. South Atlantic magnetic anomaly ionization: A review and a new focus on electrodynamic effects in the equatorial ionosphere. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2005, 67, 1643–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, M.; De Paula, E.; Batista, I.; Reinisch, B.; Matsuoka, M.; Camargo, P.; Veliz, O.; Denardini, C.; Sobral, J.; Kherani, E.; et al. Abnormal evening vertical plasma drift and effects on ESF and EIA over Brazil-South Atlantic sector during the 30 October 2003 superstorm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, M.A. Equatorial ionosphere–thermosphere system: Electrodynamics and irregularities. Adv. Space Res. 2005, 35, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, E.R.; de Oliveira, C.B.; Caton, R.G.; Negreti, P.M.; Batista, I.S.; Martinon, A.R.; Neto, A.C.; Abdu, M.A.; Monico, J.F.; Sousasantos, J.; et al. Ionospheric irregularity behavior during the September 6–10, 2017 magnetic storm over Brazilian equatorial–low latitudes. Earth Planets Space 2019, 71, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmyrov, G.M.; Galkin, I.A.; Kozlov, A.V.; Reinisch, B.W.; McElroy, J.; Dozois, C. Exploring digisonde ionogram data with SAO-X and DIDBase. AIP Conf. Proc. 2008, 974, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkin, I.; Khmyrov, G.; Kozlov, A.; Reinisch, B.; Huang, X.; Kitrosser, D. Ionosonde networking, databasing, and Web serving. Radio Sci. 2006, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.J.; Batista, S.I.; Costa, F.R. A Simple Method to Calculate the Maximum Usable Frequency. In Proceedings of the 13th International Congress of the Brazilian Geophysical Society & EXPOGEF, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 26–29 August 2013; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hysell, D. Antennas and Radar for Environmental Scientists and Engineers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abdu, M.; Souza, J.; Batista, I.; Fejer, B.; Sobral, J. Sporadic E layer development and disruption at low latitudes by prompt penetration electric fields during magnetic storms. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2013, 118, 2639–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Sripathi, S.; Zhao, B.; Chen, Y.; Le, H.; Hu, L. Effects of disturbed electric fields in the low-latitude and equatorial ionosphere during the 2015 St. Patrick’s Day storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2016, 121, 9111–9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polekh, N.; Zolotukhina, N.; Kurkin, V.; Zherebtsov, G.; Shi, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z. Dynamics of ionospheric disturbances during the 17–19 March 2015 geomagnetic storm over East Asia. Adv. Space Res. 2017, 60, 2464–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Lee, Y.; Song, S.; Kim, Y.; Yun, J.; Sripathi, S.; Rajesh, B. Ionospheric density oscillations associated with recurrent prompt penetration electric fields during the space weather event of 4 November 2021 over the East-Asian sector. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2022, 127, e2022JA030456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejer, B.G.; Scherliess, L.; De Paula, E. Effects of the vertical plasma drift velocity on the generation and evolution of equatorial spread F. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1999, 104, 19859–19869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Liou, K.; Lepping, R.P.; Hutting, L.; Plunkett, S.; Howard, R.A.; Socker, D. The first super geomagnetic storm of solar cycle 24: “The St. Patrick’s day event (17 March 2015)”. Earth Planets Space 2016, 68, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, W.; Joselyn, J.A.; Kamide, Y.; Kroehl, H.W.; Rostoker, G.; Tsurutani, B.T.; Vasyliunas, V. What is a geomagnetic storm? J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1994, 99, 5771–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, J.; Pizzo, V. Formation and evolution of corotating interaction regions and their three dimensional structure. Corotating Interact. Reg. 1999, 89, 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Vršnak, B.; Temmer, M.; Veronig, A.M. Coronal holes and solar wind high-speed streams: I. Forecasting the solar wind parameters. Sol. Phys. 2007, 240, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, J.; Huba, J.; Joyce, G.; Yokoyama, T. Density enhancements associated with equatorial spread F. Ann. Geophys. 2010, 28, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]