Abstract

The projected climate change in Slovakia is expected to have a significant impact on temperature and moisture conditions in agricultural production, as well as on phenological patterns and soil properties. These alterations have the potential to diminish crop yields in regions experiencing summer heat, augment soil evaporation, and elevate the probability of drought. The objective of this study was to evaluate and revise the spatial extent of vegetation zones and agricultural land. A detailed analysis of the past 30 years revealed that the growing season has become both earlier in the year and later in the year in terms of its onset and cessation. Projections indicate that, by 2091–2100, the great growing season (GGS) will be 25–30 days longer and the main growing season (MGS) 20 days longer than at present. The results indicate that the extended growing seasons will encompass larger areas and gradually shift to higher altitudes. At present, the 220–240-day category of the GGS spatial domain is dominant (1.7–2.3 million hectares), while durations of the GGS exceeding 260 days, which were absent in the 1971–1980 period, are expected to increase the area of the growing season by approximately 55,000 hectares by 2100. For the MGS, the 160–190-day category remains prevalent (approximately 2.5 million hectares), with only moderate future increases of up to 220 days being expected. It is anticipated that extended durations will remain constrained, encompassing less than 50,000 hectares.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a subject that is being discussed with increasing frequency in today’s society, with efforts to mitigate its adverse effects being a matter of increasing concern for all sectors of society worldwide [1]. In recent years, the primary focus of efforts to address the impacts of climate change has transitioned from the scientific domain to the social and political sphere, as well as to practical applications. This situation underscores the pressing necessity to adopt a coordinated approach to the utilisation of our limited resources, encompassing the assimilation and implementation of comprehensive, national-level, climate-friendly mitigation and adaptation strategies [2].

Agriculture is a discipline that is strongly influenced by external environmental factors, particularly soil and climate conditions. It is evident that agriculture is contingent not only on local natural conditions but is also influenced by several other factors. The amount of agricultural land in use has been decreasing in the long term [3]. Furthermore, it is highly sensitive to climate variability and extreme weather events, including droughts, severe storms and floods [4]. Human activity has already had an impact on atmospheric properties such as temperature, precipitation, carbon dioxide (CO2) and ground-level ozone concentrations, and it is anticipated that this trend will continue [5]. Temperature is one of the fundamental environmental factors influencing plant life, affecting crucial biological processes such as nutrient uptake, transpiration, photosynthesis, and respiration [6,7]. While the prospect of elevated temperatures may hold potential benefits for the agricultural sector, the projected increase in extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods and heatwaves, is likely to present significant challenges for those engaged in agricultural pursuits [4,8]. It is becoming increasingly evident that global climate change has the potential to render certain regions unsuitable for the purpose of crop production [9].

The survival of cultivated plants is contingent upon the maintenance of a specific temperature range [10]. The upper and lower limits of this range are determined by the anatomical structure of the plant and the physiological processes taking place in its organs. These limits are designated as “critical temperatures”. The temperature range at which plants can develop and grow well varies. The response of plants to these conditions is dependent on the species in question, as well as the geographical location and environment in which they are situated. In temperate regions, plants demonstrate a capacity to withstand a broad spectrum of temperatures; however, in tropical regions, this range is more constrained, with the lowest tolerable temperatures being observed in the Arctic or mountain zones [11]. A narrower range of temperatures, falling between these extremes, is best suited to the organism’s requirements at a given stage of development. The following limits represent the optimal temperatures and the optimal temperature range. For the majority of cultivated plants, the minimum temperature is generally 0.0–5.0 °C, the optimum is 15.0–30.0 °C, and the maximum is 35.0–42.0 °C [11].

The onset and termination of the growing season for agricultural species were determined based on phenological observations and air temperatures of T ≥ 5.0 °C and T ≥ 10.0 °C. Due to the clear influence of temperature on plant growth and the onset of individual phenophases, the terms “Great growing season” (GGS) and “Main growing season” (MGS) have become established [12,13]. For this purpose, the following generally recognised growing seasons were chosen and analysed:

- -

- The Great growing season, bounded by the onset and termination of days with an average daily temperature of T ≥ 5.0 °C [12,13];

- -

- The Main growing season is bounded by the onset and cessation of days with an average daily temperature of T ≥ 10.0 °C [12,13].

The temporal sequence of plant phenophases is predominantly dictated by the energy and water availability in their environment [14]. Changes in temperature, rainfall and other environmental factors have been demonstrated to alter the dates on which the phenophases begin and end [11,14]. This, in turn, has been shown to affect the length of the intervals between phenophases and the length of the entire growing season of the crops. Rising temperatures driven by climate change cause the thermal thresholds that initiate the growing season to be reached earlier, while conversely, temperatures fall below these thresholds later in the year.

These changes are altering the timing of plant life, i.e., the onset of phenophases, and consequently the length of the intervals and the entire growing season of individual crops [15]. This scenario is predicated on the predicted basic indicators of agro-climatic conditions over the course of a growing season, such as an increase in the sum of daily temperatures. In the context of growing seasons characterised by physiologically significant temperatures, it will be possible to observe an acceleration of the onset and a delay in the termination of phenophases [16].

A decline has been observed in three of a crop’s main water sources that include surface water, groundwater and soil water [17]. A comprehensive evaluation of the hydrological conditions in Slovakia over the past five years reveals an escalation in runoff extremes. This is characterised by decreased precipitation during summer and autumn, and increased runoff during winter in comparison to standard patterns [18].

2. Materials and Methods

The territory of Slovakia belongs, in terms of global climate classification, to the northern temperate climatic zone, characterized by the regular alternation of four seasons and variable weather with a relatively even distribution of precipitation throughout the year. The climate of Slovakia is influenced by the prevailing westerly air circulation in the mid-latitudes, occurring between quasi-stationary pressure systems (the Azores High and the Icelandic Low). The westerly flow brings moist oceanic air of temperate latitudes from the Atlantic Ocean, which moderates the diurnal and annual temperature amplitudes and contributes to atmospheric precipitation.

Under suitable synoptic conditions, the weather in Central Europe may also be affected by continental air masses of predominantly temperate latitudes. These are characterized by greater diurnal and annual air temperature amplitudes and lower total precipitation. Continental air of temperate latitudes typically brings warm, sunny, and less humid summers, as well as cold winters with low precipitation totals.

The alternation of air masses throughout the year, combined with the significant vertical variability of Slovakia’s terrain, has resulted in a diverse mosaic of climatically distinct regional zones across the country. Mountain ranges, particularly the high ones, form major climatic boundaries and, together with the rugged topography, significantly influence individual climatic elements—especially air temperature, precipitation, humidity, cloudiness, sunshine duration, and wind conditions. Therefore, lowlands, basins, valleys, slopes, and mountain ridges all exhibit distinct climatic characteristics.

The shape of Slovakia’s territory, elongated in the west–east direction, also conditions differences in temperature and precipitation patterns between western and eastern Slovakia. The influence of the Atlantic Ocean on Slovakia’s climate gradually decreases from west to east, which is reflected, for instance, in the fact that winters in eastern Slovakia are, on average, up to 3 °C colder at the same altitude than in the western part of the country [19,20]. The influence of the Mediterranean Sea is more complex, as it depends on the season, airflow direction, and orographic exposure. In general, the Mediterranean influence is most pronounced in areas south of the Slovenské Rudohorie Mountains.

The climate of a specific locality is also affected by microclimatic factors, in particular the shape of the terrain (convex or concave), the orientation of the relief with respect to cardinal directions and prevailing airflow, relative elevation differences, vegetation cover, and anthropogenic influences.

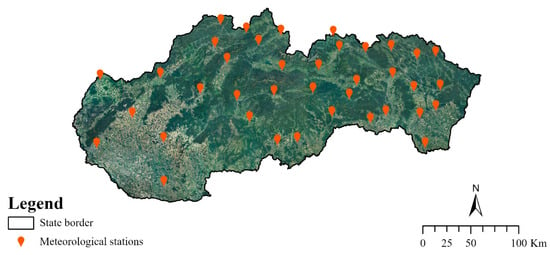

Meteorological data (values of average temperatures) for the reference time series (1961–2010) were provided by the Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute in Bratislava. The Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute (SHMI) operates approximately 100 stations throughout Slovakia. Stations with an altitude of more than 800 m were excluded from the study, as these localities are not suitable for agriculture in Slovakia. In order to analyse the phenological conditions of agricultural species in Slovakia, 38 stations were selected throughout the country (see Figure 1). Using mathematical and statistical methods, trend equations were derived individually for each meteorological station based on daily data from the period 1960–2010. These functions formed the basis for projecting temperature change trends for the decades 2041–2050, 2071–2080, and 2091–2100.

Figure 1.

Locations of SHIM’s meteorological stations in Slovakia.

The alteration in the growing season of the analysed agricultural species was ascertained by calculating the onset and termination of the growing season according to the formula (1), and analysed using the average daily temperature from 1961 to 2015. Subsequently, forecasts were conducted for the decades 2011–2020, 2041–2050, 2071–2080, and 2091–2100, and the results were presented in the form of map outputs.

The onset or termination of the vegetation period was determined by linear interpolation between consecutive days on which the mean daily air temperature crossed the critical threshold. The exact day of the year corresponding to the threshold temperature exceedance was computed using the following relationship:

The exact day of the year corresponding to the threshold temperature exceedance was computed using the following formula:

where rv denotes the real day of the year (expressed as a decimal fraction) representing the moment when the threshold temperature is reached, R is the ordinal number of the first day in the temperature pair considered, t1 and t2 are the mean daily air temperatures (°C) observed on the first and second day, respectively, and Tk is the critical (threshold) temperature.

The ArcGIS Pro 3.4.0 software from ESRI was selected for the processing of map outputs. This software, which is of a modular nature, is ideal for the processing, analysis and visualisation of geographic information [21].

Prior to the processing of map outputs, the input data underwent a preparatory stage. The position of each meteorological station was defined in XYZ coordinates. Upon loading into the ArcGIS environment, the coordinates underwent transformation so that the resulting point vector model (*.shp) was placed in the S-JTSK coordinate system. This facilitated the precise determination of the locations of meteorological stations in Slovakia.

Following the acquisition of the locations of the stations in question, the subsequent step entailed the allocation of the calculated lengths of the vegetation periods in the individual decades under investigation to these locations. The data on the lengths of the growing seasons was prepared in the Excel environment, and then assigned to the individual meteorological stations according to their serial numbers.

Given the irregular geographical distributions of the meteorological stations, it was necessary to obtain data for the entire territory of Slovakia. Consequently, we initiated the interpolation process. The ‘Topo to Raster’ interpolation method was utilised in order to interpolate the unknown values. This method was applied in ANUDEM version 4.6.3 by combining the IDW (inverse distance weighted), Kriging and Spline interpolation [22]. The process was utilised to obtain data for the entirety of the Slovakian territory and each examined decade.

Subsequently, the individual categories of length of growing season were reclassified according to the histogram for each period.

The objective of the study was to ascertain variations in the length of the growing season across the selected decades on agricultural land. To this end, it was imperative to remove data points that might compromise the integrity of the resulting values. Consequently, a digital elevation model with a resolution of 10 m was employed to delineate areas with an altitude exceeding 800 m above sea level. These areas were then excluded from the calculations and appear as empty spaces on the resulting maps.

Subsequent to the processing of all data into graphic form, the print view was utilised for the purpose of assigning a scale, a northing, and a legend to the maps. This process enabled the delineation of the individual categories shown. The resulting map assembly was subsequently exported in JPEG format at a resolution sufficient to ensure optimal readability.

3. Results

This chapter analyses the impact of climate change on the length of the growing season compared to the 1961–2015 reference period, and possible changes within the time horizons of 2011–2020, 2041–2050, 2071–2080 and 2091–2100.

The temporal progression of plant life history, otherwise known as phenophases, is predominantly influenced by temperature and water [3,4,8,10,11]. Our results show that changes in the energy balance in Slovakia have been shown to alter the timing of phenophases, thereby affecting the duration of phenophase intervals and the entire crop growing season.

In the context of the growing season characterised by physiologically significant temperatures, a delay in the onset and termination of the season is observed, resulting in an augmentation of its duration.

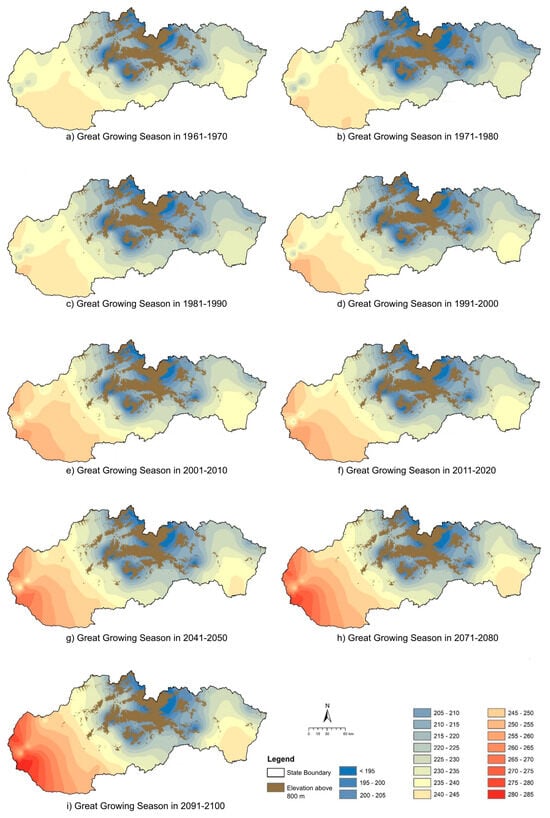

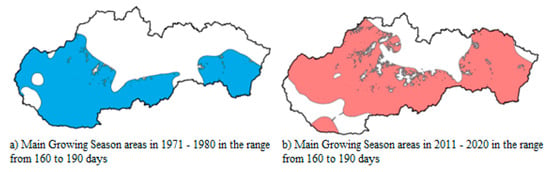

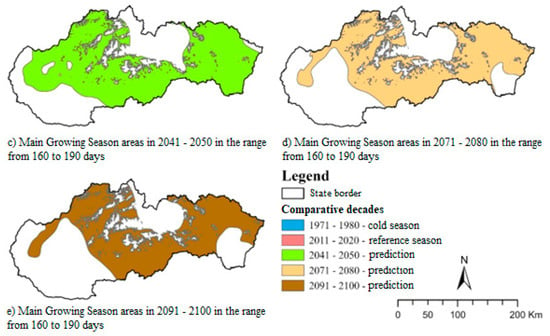

The map outputs (Figure 2a–i) demonstrate that there has been a substantial alteration in the length of the growing season (GGS) over the 1961–2000 period. For the 1961–70 decade, the length of the MGS was found to be 240–245 days in the Danube Plain. Over the subsequent two decades, this figure increased by five days, reaching 250–255 days in the 1991–2000 period. Furthermore, a notable shift is evident in the projections for the 2011–2100 period (see Figure 2f,i), which indicate that by the year 2100, the length of the growing season in south-west Slovakia will extend to 280–285 days. When compared to the 2001–2010 period, this projected increase is an average of 25–30 days, and when contrasted with the 1961–1970 decade, it is a 35–40 day increase in the most fertile region of Slovakia.

Figure 2.

Duration of the Great growing season in each decade.

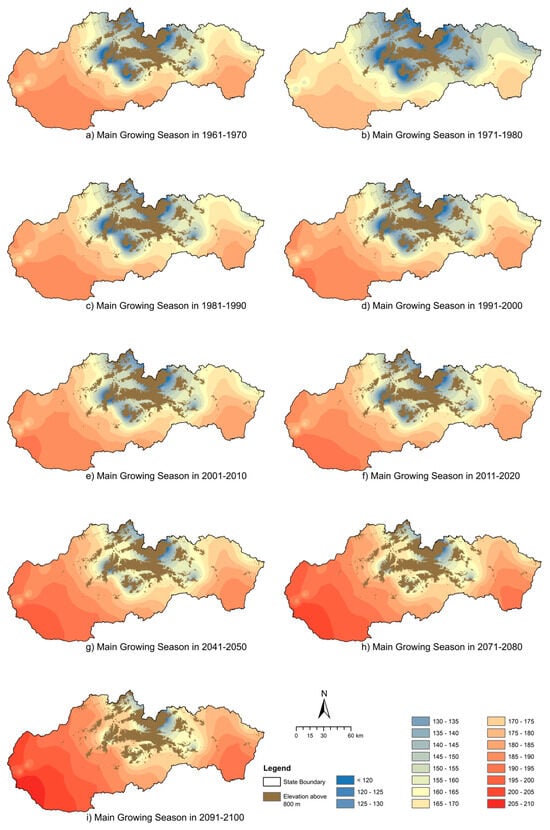

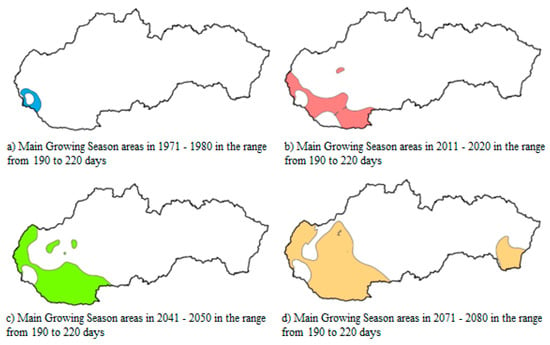

Figure 3 shows the durations of the main growing season in each decade. An analysis of the map outputs (see Figure 3a–d) reveals that, between 1961 and 2000, the length of the MGS (185–190 days in southern Slovakia) remained relatively unchanged, with the exception of the cold decade of 1971–80, during which a reduction of 10 days was recorded. However, more significant changes appear in the 2001–2020 period (see Figure 3e,f), with an increase in the length of the growing season of 5 days. A warming trend is evident in the following decades, as reflected in the projections of the map outputs. As demonstrated in Figure 3g, when contrasted with the 1961–1990 period, the MGS increases by 10 days towards the 2041–2050 horizon. By the 2071–2080 decade (see Figure 3h), the MGS is predicted to increase to 200–205 days, and by the 2100 horizon, to 205–210 days. In comparison with the 1961–1990 period, this is a projected increase of 20 days on average to the 2091–2100 decade (Figure 3i), and an increase of 30–35 days compared with the coldest decade.

Figure 3.

Duration of main growing season in each decade.

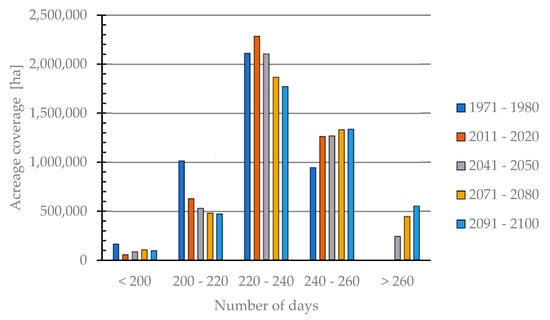

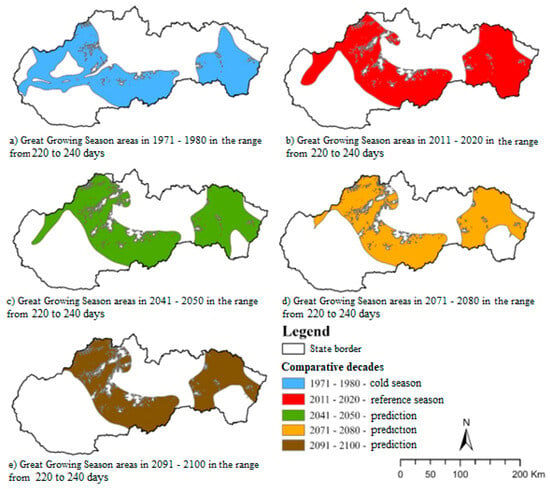

The GGS duration was reclassified into five categories, each with a spacing of 20 days, based on the number of days in each decade. The observed intervals ranged from 200 days to 260 days or more, with specific periods including 200–220 days, 220–240 days, and 240–260 days. During the cool decade of 1970–1980, the area covered by GGS of up to 200 days was approximately 170,000 hectares. However, it is predicted that this area will decrease in the decades after 2100 (Figure 4). Conversely, as the length of the growing season increases in future decades, it is expected that the area covered will increase concomitantly. During the cool decade, a decrease in area was observed, with no periods exceeding 260 days. By the year 2100, it is projected that approximately 555,000 hectares will experience a growing season of over 260 days. The median length at which approximately equivalent areas have been recorded is between 220 and 240 days. The areas in question range from 1,700,000 to 2,200,000 ha for all decades under comparison.

Figure 4.

Acreage coverage in hectares (ha) by day intervals during the Great growing season.

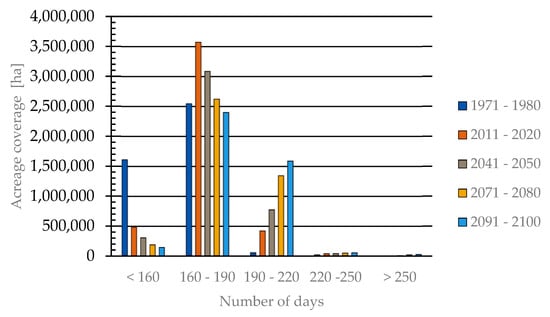

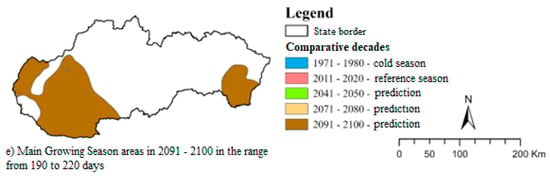

For the MGS, the individual decades have also been reclassified into five classes with 30-day intervals when the average temperature is above 10.0 °C. The design of these intervals was informed by a histogram, with the initial interval extending up to 160 days. The subsequent intervals are 160–190 days, 190–220 days, 220–250 days, and over 250 days. As demonstrated in Figure 5, in the past, the period of up to 160 days occurred over a more extensive area than at present. The area in question encompasses 1,600,000 hectares, constituting 38.0% of the total area. It is evident that periods exceeding 250 days are no longer evident during the cold season; however, for other periods, they are capable of covering an area of approximately 30,000 hectares. The 160–190-day interval is characterised by the most extensive areal extent of all the decades. It is anticipated that the MGS will encompass an area of approximately 2,500,000–3,500,000 ha over this span. This interval is responsible for covering 60–70% of the area.

Figure 5.

Acreage coverage in hectares (ha) by day intervals during the Main growing season.

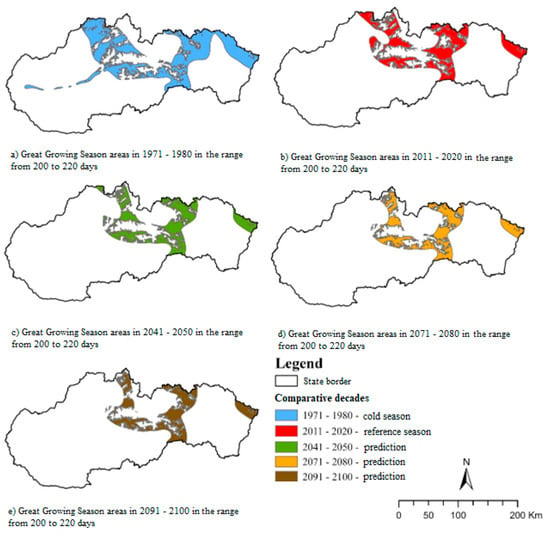

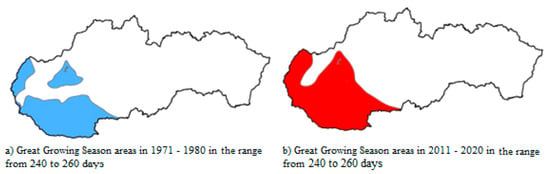

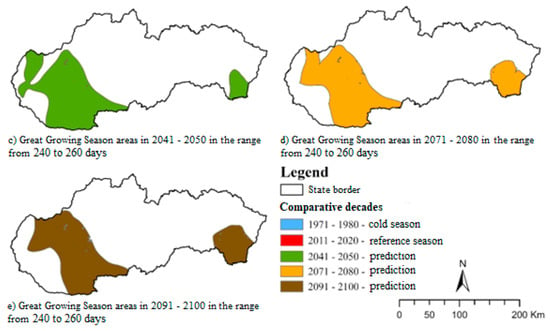

Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate the change in area for each specified day interval of the GGS. While shorter GGS durations (200–220 days) were previously represented over larger areas, it is anticipated that these areas will decrease in the future. Evidence of this shorter duration is manifest in the northern part of the Orava region, the central part of the Low Tatras, and extends as far south as the Rožňava basin and as far east as the Bukovské vrchy in the north-east. The mean length of the GGS (220–240 days) has been shown to remain consistent across all decades. These areas form a belt extending from the northwest, from the Trenčianska and Ilava basins (in the western part), towards the Rožňava basin (in the southern part). In the eastern part of the region, this length is expected to follow an arc shape, with the Slanské vrchy, Ondavská vrchovina and Laborecká vrchovina forming the axis of this arc. The maximum duration of GGS (240–260 days) is predicted to occur exclusively within the Danubian Lowlands (southwest) and the East Slovak Lowlands. As demonstrated in Figure 8, the occurrence of such a long GGS was not observed in the East Slovak Lowlands in the past; indeed, it was only identified in the south-western part of the Danube Lowlands during that period.

Figure 6.

Great growing season areas covered in each decade for periods in the range of 200–220 days (mean length).

Figure 7.

Great growing season areas covered in each decade for periods in the range of 220–240 days (mean length).

Figure 8.

Great growing season areas covered in each decade for periods in the range of 240–260 days (mean length).

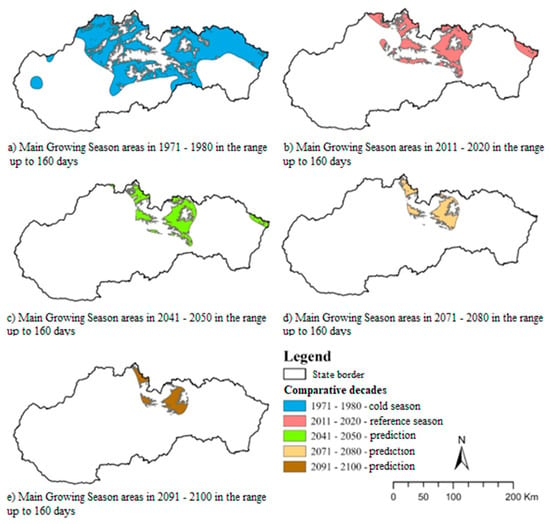

As demonstrated in Figure 9, the historical record indicates that this period persisted for a duration of up to 160 days within the northern half of the study area. As demonstrated in Figure 9b–e, it is anticipated that the regions in which such lengths are observed will undergo a decline in the future. In the final decade (2091–2100), the presence of this length of the MGS will be confined to the area surrounding the High Tatras and Spišská Nová Ves in the north and north-east of Slovakia. The median length of this period (160–190 days) occurs in a similar area in all decades studied. However, the maps presented in Figure 10a–e demonstrate that, while this phenomenon was previously more prevalent in the southern and south-western regions of the area, it is anticipated to undergo a northward migration as far as the border with Poland in the future. In subsequent decades, the mean duration (160–190 days) of this phenomenon will no longer be observed in the Danube Lowlands. The maximum duration (190–220 days) is predicted to occur in the south-western part of the Danube Lowlands. Historically, such a protracted period was only observed in the vicinity of Bratislava (Figure 11a–e). It is anticipated that, in future, this duration will extend northwards and north-eastwards from Bratislava, thereby spreading over the East-Slovak Lowlands.

Figure 9.

Main growing season areas covered in each decade for periods in the range of ≤160 days (mean length).

Figure 10.

Main growing season areas covered in each decade for periods in the range of 160–190 days (mean length).

Figure 11.

Main growing season areas covered in each decade for periods in the range of 190–220 days (mean length).

4. Discussion

The findings presented in this study align with a growing body of evidence demonstrating that the length of the growing season across temperate regions has been increasing as a consequence of climate change. This trend has been consistently observed in various climatic and geographical contexts, although the magnitude and timing of changes differ depending on regional conditions, elevation, and crop type. Our findings presented in this paper demonstrate that climate change will significantly affect the duration of suitable conditions for plant growth and agricultural crop cultivation. The projected scenarios toward the end of the century indicate substantial changes, including an extension of both the Great and Main growing seasons.

Valšíková-Frey et al. [23] project substantial shifts in the timing of sowing and harvesting in southwestern Slovakia, particularly at the Hurbanovo site, where delays of up to 41 days for root and bulb vegetables are expected by 2075. These temporal displacements suggest a significant modification of the agricultural calendar, reflecting the broader influence of climatic warming on phenological stages. In a complementary study, Špánik et al. [24] modelled the impact of climate change on selected vegetable species under the Canadian Climate Centre Model (CCCM 2000) scenario. Their simulations indicate a 21–26% increase in the growing season length by 2075 for crops cultivated in both southern (Hurbanovo) and northern (Liptovský Hrádok) regions of Slovakia. The convergence of these two studies underscores a consistent national-scale pattern—while climatic conditions will differ regionally, the overall direction of change points towards an elongation of the growing season.

Similar observations have been reported across Central Europe. Olszewski and Żmudzka [25], analysing data from nine Polish meteorological stations between 1938 and 1998, found an increase in the general vegetation period by 1 to 3 days per decade. This trend was attributed to both an earlier onset (by approximately 0.5–1.5 days per decade) and a delayed termination (by a similar rate). Their findings thus confirm that the lengthening of the growing season is not solely the result of a postponed end but a combination of both earlier initiation and later cessation of vegetation activity—an interpretation that corresponds with the results obtained in Slovakia.

A broader, global perspective is provided by Christiansen E. Daniel et al. [26], whose multi-site study across the United States projected an average increase in the growing season length of 27 to 47 days between 2001 and 2099. Their models similarly predict an earlier onset of emergence and flowering, coupled with a delayed conclusion in autumn. This pattern mirrors the European trends, suggesting that the extension of the growing season represents a global phenomenon linked to rising mean temperatures.

Comparable tendencies were reported by Sarraf et al. [27] for Iran, where a projected extension of approximately 27 days by the year 2100 was identified based on data from 43 synoptic stations. The study also noted concurrent increases in both minimum and maximum daily and monthly temperatures, which further corroborates the relationship between temperature elevation and phenological shifts. Such thermal influences are further reflected in the findings of Arslantaş and Yeşilırmak [28] in Western Anatolia, Turkey. Their work demonstrated that the altitude of meteorological stations plays a decisive role in determining the onset, culmination, and termination of the growing season. Lower elevations exhibited both an earlier start and a later end, while higher-altitude sites experienced delayed and shorter growing periods. Nonetheless, even under these topographic constraints, a general increase in the length of the growing season—ranging from 12 to 15.9 days depending on the temperature threshold—was observed.

Taken together, these studies converge on the conclusion that the lengthening of the growing season is a robust and spatially coherent signal of ongoing climatic warming. The regional differences noted by Valšíková-Frey et al. [23], Špánik et al. [24], and Arslantaş and Yeşilırmak [28] emphasize the importance of local climatic and topographic factors in modulating the magnitude of change. However, when placed in a broader international context—such as the works of Olszewski and Żmudzka [25], Christiansen E. Daniel et al. [26], and Sarraf et al. [27]—the Slovak findings fit within the global trajectory of earlier spring onset and delayed autumn termination. These results collectively suggest that the prolonged growing season, while potentially beneficial for crop productivity, will also require careful management to mitigate associated challenges such as increased evapotranspiration, pest pressure, and altered water demands.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the temporal and spatial variation in the Great Growing Season (GGS) and the Main Growing Season (MGS) in Slovakia, defined by mean daily temperature thresholds of 5.0 °C and 10.0 °C, respectively. The results indicate a clear and consistent extension of both growing seasons during the past decades, driven by regional climate warming. The onset of the growing season has advanced, while its termination has been delayed, leading to longer and more variable growing periods across most regions.

Projections for the late 21st century (2091–2100) suggest that the GGS will extend by approximately 25–30 days, and the MGS by around 20 days, relative to present-day conditions. Spatial analyses further demonstrate that longer growing season categories are expected to shift to higher altitudes, expanding the area of thermally suitable zones for crop production. The GGS category of 220–240 days remains dominant in all analyzed decades, while regions with growing periods exceeding 260 days—absent during 1971–1980—are projected to emerge, covering up to 55,000 ha by 2100. Similarly, the MGS is projected to remain most prevalent in the 160–190 days range, with a moderate increase in areas experiencing 200–220 days durations.

These findings are consistent with broader European trends of increasing air temperatures, greater interannual variability, and a rising frequency of extreme climatic events. Such changes present significant challenges for agricultural systems, where the rate of climatic change exceeds the current adaptive capacity. The uncertainty and spatial heterogeneity of climate impacts, particularly those related to droughts, heatwaves, frosts, and pest outbreaks, further complicate adaptation planning.

The results of this research provide a scientific basis for climate adaptation and mitigation in Slovak agriculture. The projected extension of the growing season highlights opportunities for adjusting crop calendars, developing new cultivars adapted to longer and warmer conditions, and improving water and nutrient management. The spatial datasets and maps generated in this study can also serve as decision-support tools for farmers, policymakers, and regional planners, facilitating the integration of climate information into sustainable agricultural management. The necessity to address this issue is also reflected in research trends at the European level [15].

Overall, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of climate-induced shifts in agroclimatic conditions in Central Europe and underscores the urgency of strengthening adaptive capacity through coordinated institutional frameworks and knowledge dissemination. The presented results can support the formulation of targeted strategies that enhance the resilience and long-term sustainability of agricultural production under a changing climate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D. and J.Č.; methodology, I.D. and J.Č.; software, M.M.; validation, I.D., A.T. and M.B.; formal analysis, A.T.; investigation, I.D.; resources, J.Č., A.T. and M.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.; writing—review and editing, J.Č. and M.B.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, J.Č.; project administration, J.Č. and I.D.; funding acquisition, J.Č. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Cultural And Educational Grant Agency, grant number KEGA 026SPU-4/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Muchová, Z.; Tárniková, M. Land cover change and its influence on the assessment of the ecological stability. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2018, 16, 2169–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, B.; Łabędzki, L. Thermal conditions in Bydgoszcz Region in growing seasons of 2011–2050 in view of expected climate change. J. Water Land Dev. 2014, 23, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabella, E.; Aprile, A.; Negro, C.; Nicoli, F.; Nutricati, E.; Vergine, M.; Luvisi, A.; De Bellis, L. Impact of climate change on durum wheat yield. Agronomy 2020, 10, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, B.; Borzí, I.; Bonaccorso, B.; Martina, M. Quantifying crop vulnerability to weather-related extreme events and climate change through vulnerability curves. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 2761–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magugu, J.W.; Feng, S.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; West, G.H. Analysis of future climate scenarios and their impact on agri-culture in eastern Arkansas, United States. J. Water Land Dev. 2018, 37, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, M.; Xiangjin, S.; Jiaqi, Z.; Chunlin, X.; Yiwen, L.; Liyuan, W.; Yanji, W.; Ming, J.; Xianguo, L. Variation of vegetation autumn phenology and its climatic drivers in temperate grasslands of China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 114, 103064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Jiang, M.; Lu, X. Diverse impacts of day and night temperature on spring phenology in freshwater marshes of the Tibetan Plateau. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2023, 8, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra-Bonilla, E.B.; Da Cunha, D.A.; Braga, M.J.; Oliveira, L.R. Extreme weather events and crop diversification: Climate change adaptation in Brazil. Mitig. Adapt Strat. Glob. Change 2025, 30, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkenes, M.; Alkemade, R.M.; Ihle, F.; Leeman, R.; Latour, J.B. Assessing effects of forecasted climate change on the diversity and distribution of European higher plants for 2050. Glob. Change Biology 2002, 8, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.M.; Lin, H.X.; Chong, K. Crop Improvement Through Temperature Resilience. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 753–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nievola, C.C.; Carvalho, C.P.; Carvalho, V.; Rodrigues, E. Rapid responses of plants to temperature changes. Tempreture 2017, 4, 371–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurpelová, M. Phenological-geographical regionalization of the territory of Slovakia. Proc. HMI 1976, 9, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kurpelová, M.; Coufal, L.; Čulík, J. Agroklimatické Podmienky ČSSR [Agroclimatic Conditions of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic]; Bratislava: Príroda, Slovakia, 1975; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, W.; Schmidt, G.; Schönrock, S. Modelling and mapping of plant phenological stages as bio-meteorological indicators for climate change. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2014, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čimo, J.; Aydın, E.; Šinka, K.; Tárník, A.; Kišš, V.; Halaj, P.; Toková, L.; Kotuš, T. Change in the Length of the Vegetation Period of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), White Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata) and Carrot (Daucus carota L.) Due to Climate Change in Slovakia. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnárová, J.; Čimo, J.; Špánik, F. The agroclimatical analysis of production process of spring barley. Analele Univ. Oradea 2010, 9, 639–661. [Google Scholar]

- Pretel, J.; Metelka, L.; Novický, O.; Daňhelka, J.; Rožnovský, J.; Janouš, D. Refinement of existing estimates of climate change impacts in the water management, agriculture and forestry sectors and proposals for adaptation measures. In Final Report on the Solution of the R&D Project SP/1a6/108/07 in the Years 2007–2011; ČHMÚ: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SHMI: Climatic Conditions of the Slovak Republic. Available online: https://www.shmu.sk/sk/?page=1064 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Labudová, L.; Faško, P.; Ivaňáková, G. Changes in climate and changing climate regions in Slovakia. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2015, 23, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilček, J.; Škvarenina, J.; Vido, J.; Nalevanková, P.; Kandrík, R.; Škvareninová, J. Minimal change of thermal continentality in Slovakia within the period 1961–2013. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2016, 7, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šinka, K.; Muchová, Z.; Konc, Ľ. Geographic Information Systems in Spatial Planning; SAU: Nitra, Slovakia, 2015; ISBN 978-80-552-1444-3. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI: How Topo to Raster Works. Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/latest/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/how-topo-to-raster-works.htm (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Valšíková, M.; Čimo, J.; Špánik, F. Horticulture in conditions of climate change. Meteorol. J. 2011, 14, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Špánik, F.; Valšíková-Frey, M.; Čimo, J. Change in the temperature security of basic types of vegetables in conditions of climate change. Acta Hortic. Regiotect. 2007, 10, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, K.; Żmudzka, E. Variability of the vegetative period in Poland. Misc. Geogr. 2000, 9, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, D.E.; Markstrom, S.L.; Hay, L.E. Impacts of Climate Change on the Growing Season in the United States. Earth Interact. 2011, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, B.S.; Khorshiddost, A.M.; MahmoudI, P.; Daraei, M. Impacts of climate change on the growing season in the Iran. Ital. J. Agrometeorol. 2018, 23, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslantaş, E.E.; Yesilırmak, E. Changes in the climatic growing season in western Anatolia, Turkey. Meteorol. Appl. 2020, 27, e1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).