Abstract

The FY-4A satellite represents a new generation of geostationary platforms, providing high-temporal-resolution observations over China. However, challenges remain in effectively leveraging the FY-4A satellite data for high-temporal-resolution PM2.5 concentration estimation, particularly regarding the unclear key parameters required for accurate estimation and the limited interpretability of models. This study utilizes an interpretable deep learning framework that integrates FY-4A Top-of-Atmosphere (TOA) reflectance data, meteorological variables, and auxiliary data to estimate surface high-temporal-resolution PM2.5 concentrations from 2019 to 2023. A multicollinearity test was applied to optimize feature selection, while the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method was used to enhance model interpretability. The results indicate that parameters such as TOA02, TOA03, TOA04, and boundary layer height (BLH) significantly influence model performance across years. The model demonstrates strong predictive ability in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region, achieving an average R2 of 0.83. Root mean square error (RMSE) values remained below 15 µg/m3, aligning well with ground-based monitoring data. These findings demonstrate that combining high temporal satellite data with interpretable deep learning provides a reliable approach for long-term, high-temporal-resolution PM2.5 monitoring in regions.

1. Introduction

Particulate matter (PM2.5) with a particle size of smaller than 2.5 μm is associated with various health problems [1,2]. Prolonged exposure to these particles raises the rates of respiratory and cardiovascular disease morbidity and death [2,3,4,5]. PM2.5 not only degrades air quality, visibility, and public health but also affects the Earth’s climate by modifying radiative processes, cloud microphysics, precipitation regimes, and the hydrological cycle [6,7]. Consequently, PM2.5 has emerged as a critical environmental issue of global concern [8,9]. In recent decades, China’s rapid industrialization and urbanization have intensified PM2.5 pollution, particularly in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region [10,11]. Therefore, accurate monitoring of PM2.5 levels is essential for improving environmental quality and reducing associated health risks.

Ground stations can provide continuous and accurate hourly monitoring of PM2.5. However, ground stations face challenges such as high construction costs and sparse, uneven spatial distributions [12,13,14]. Ground monitoring alone is insufficient to capture the large-scale distribution of air pollution, limiting the ability to understand its dynamics, support health and environmental research, and develop effective policies [15]. Remote sensing satellite monitoring provides broad spatial coverage, long time series, and convenient data acquisition, effectively overcoming the limitations of ground station monitoring and enabling continuous large-scale atmospheric pollutant observations [16,17,18]. Polar-orbiting remote sensing satellites have been widely used in previous studies. However, their limited swath width and low revisit frequency result in coarse temporal resolution (daily), making it challenging to monitor PM2.5 in real time or accurately capture its intraday concentration variations [19,20]. As a result, geostationary satellites with superior radiative, spectral, and spatiotemporal resolution have become essential tools for meteorological and terrestrial observations. The FY-4A satellite, an advanced geostationary meteorological satellite developed independently by China, features the Advanced Geostationary Radiation Imager (AGRI). This instrument provides full-disk scans every 15 min, offering a valuable platform for real-time PM2.5 monitoring and accurate retrieval of PM2.5 concentration data [21,22,23,24].

As remote sensing satellites cannot directly measure atmospheric constituents, a nonlinear relationship must be established between the influencing variables. The widespread use of aerosol optical depth (AOD) in estimating PM2.5 concentrations has been supported by extensive research that has demonstrated the relationship between AOD and particulate matter concentration. [25,26,27,28]. However, due to constraints imposed by clouds, bright surfaces, and inversion algorithms, AOD products often contain large regions with missing values and inversion errors [29,30]. PM2.5 concentration obtained from AOD inversion is insufficient to meet daily exposure assessment needs at the urban scale. To reduce uncertainty in PM2.5 concentration estimation, Shen et al. [31] proposed estimating PM2.5 directly from satellite Top-of-Atmosphere (TOA) reflectance, avoiding error propagation in AOD-based methods. Their model achieved an R2 of 0.87, slightly outperforming the AOD-PM2.5 approach. Consequently, the TOA-PM2.5 model has been widely adopted for PM2.5 estimation and analysis.

In recent years, research on PM2.5 estimation using TOA reflectance data has progressed from feasibility studies to comparative analyses with the AOD-PM2.5 method and, more recently, to application of this approach for monitoring PM2.5 concentrations in highly polluted areas, providing more detailed insights into the spatial and temporal distribution. Estimation methods have progressed from linear regression techniques to machine learning approaches capable of handling more complex relationships. Deep learning methods have also been widely applied. Li et al. [32] incorporated geographic information and spatiotemporal correlation into a Deep Belief Network (DBN) to construct a Geographic Intelligent Deep Learning Model (Geoi-DBN), achieving a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.88. Wang et al. [33] added geographic spatial autocorrelation information to a Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM) model, building a Geographic Intelligent LSTM (Geoi-LSTM) model with an R2 reaching 0.82. Fan et al. [34] employed a Deep Neural Network (DNN) to capture the nonlinear associations between satellite-derived TOA reflectance and ground-station-monitored PM2.5, enabling the estimation of near-surface PM2.5 levels across the Yangtze River Delta in 2016. Chen et al. [35] constructed a deep Bayesian framework for PM2.5 estimation that considered multiple scales. Yan et al. [36] introduced entity embedding methods and batch normalization techniques into a deep learning model, creating a new model called EntityDenseNet. Although these models exhibit high accuracy, their underlying mechanisms remain opaque, often referred to as “black box” models, which limits their interpretability [37,38]. Moreover, our previous research has revealed that, in studies directly estimating PM2.5 using TOA reflectance data, the selection of satellite band parameters is often limited to the blue, red, and shortwave infrared bands commonly used for AOD retrieval [39]. Unfortunately, few researchers choose other available bands within satellites [40,41,42]. As a result, more study is necessary required to identify the optimal combination of variables for predicting PM2.5.

The goal of this research is to use data from the FY-4A satellite TOA reflectance to forecast PM2.5 concentrations in the BTH area between 2019 and 2023. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was applied to assess feature parameters and reduce multicollinearity. This process eliminated parameters with high collinearity and identified the optimal set for PM2.5 estimation. Furthermore, to improve the interpretability of the estimation model, we integrated the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method with the DNN model, thereby constructing an interpretable model. Finally, the model was utilized to analyze the PM2.5 in the BTH area from 2019 to 2023.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. Ground PM2.5 Monitoring Data

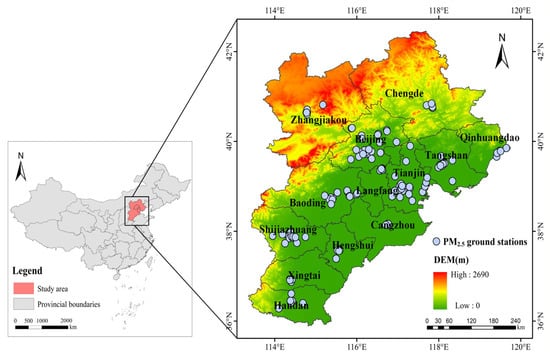

The BTH area is located in the northern sector of the North China Plain (Figure 1), gradually transitions from the northwestern Yanshan–Taihang Mountains to the southeastern plain. The eastern and central areas are characterized by frequent industrial activity and a high level of economic development, making them the economic hub of northern China. However, the BTH region also faces significant air pollution.

Figure 1.

Elevation map of the BTH and PM2.5 ground monitoring stations.

The ground observations of PM2.5 concentration for 2019–2023 were acquired from the China Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC). Its hourly measurement accuracy is ±1.5 μg/m3, while the daily average accuracy is ±0.5 μg/m3 [43,44]. The number of ground monitoring stations in 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023 was 86, 81, 121, 121 and 120, respectively. These stations are relatively evenly distributed, with higher density in urban centers (Figure 1). Data that were invalid (PM2.5 concentration < 0 μg/m3) or missing (None) were excluded.

2.1.2. FY-4A Satellite Data

In this study, the TOA reflectance, complete set of spectral bands (bands 1–14), and four observation angles (SOA, SAZ, SAA, SOZ) were extracted from the FY-4A Level 1 data. A cloud mask product (CLM) was used to exclude clouds pixel. In this study, only data classified as “clear” were used [45].

2.1.3. Meteorological Data

The ERA5 reanalysis dataset [http://apps.ecmwf.int/datasets/ (accessed on 2 May 2023)] was selected for meteorological features. Based on previous studies [46], the meteorological data includes surface pressure (SP), 2 m air temperature (T2M), boundary layer height (BLH), eastward and northward wind at 10 m above ground (U10M, V10M), and relative humidity (RH). These meteorological factors significantly affect PM2.5 concentrations [47,48,49].

2.1.4. Auxiliary Data and Data Preprocessing

The study employed the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to characterize surface features.

For model development, meteorological and auxiliary datasets were resampled to a 4 km resolution via bilinear approach to match the spatial scale of the satellite data. For FY-4A satellite TOA data, the highest-confidence CLM from FY-4A was applied to remove clouds. Temporally, ground station data recorded in Beijing Time were adjusted to be consistent with other datasets by converting to UTC (Beijing Time minus 8 h). Spatially, all feature data were calibrated to the WGS84 coordinate system, and corresponding meteorological, satellite, and auxiliary data were extracted for each pixel based on the stations’ longitude and latitude. Following the spatiotemporal matching process, the annual sample sizes from 2019 to 2023 were 81,525, 89,403, 116,974, 162,675, and 167,903, respectively. Moreover, because all feature data are expressed in different units and have disparate orders of magnitude, it was necessary to normalize these variables before inputting them into the neural network. In this study, we employed the z-score standardization method to ensure that the mean and variance of all feature data were consistent. The detailed information and statistics of the datasets is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detailed information and statistics of the datasets.

2.2. Model and Methods

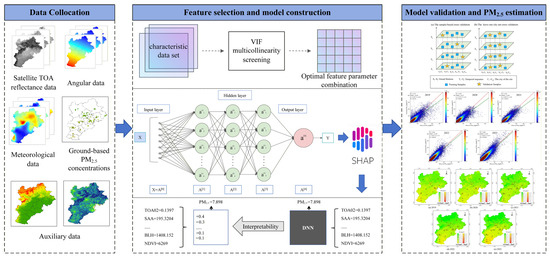

This study involves three steps (Figure 2). First, the required feature data were collected, preprocessed, and temporally and spatially aligned. Second, the VIF values of the feature parameters were calculated to identify and remove features with multicollinearity, and an annual optimal dataset of feature parameters was formed. Multicollinearity refers to the presence of linear relationships among independent variables [50]. The VIF can be used to assess the degree of multicollinearity among the predictors. Typically, when the VIF of a variable is greater than or equal to 10, strong multicollinearity is considered to exist [51], and the variable should be removed. Then, the PM2.5 estimation model was developed based on the annual optimal dataset. This study proposed a unique and interpretable PM2.5 estimation model by coupling the SHAP explainability method with a DNN. Finally, two evaluation methods were used to assess overall performance of the model. In addition, the BTH area’s PM2.5 concentrations from 2019 to 2023 were predicted.

Figure 2.

Overall technical flowchart.

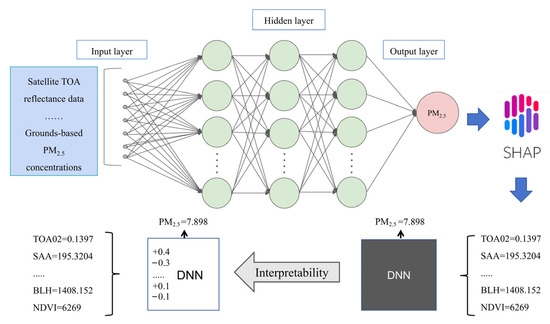

Interpretable PM2.5 Estimation Model

SHAP is an algorithm based on the Shapley value concept from game theory, designed to enhance the interpretability of machine learning models [52]. By quantifying the contribution of each feature to model predictions, SHAP provides a comprehensive explanation of the predictive process. This method is especially valuable in high-dimensional feature spaces, as it can effectively capture nonlinear relationships between variables. Specifically, the SHAP value indicates how much individual input features contribute to a model’s output, highlighting the significance of key factors and the interaction between explanatory and dependent variables. The primary goal of SHAP is to ensure a fair and transparent allocation of the influence exerted by each feature on the prediction outcome. Compared with other interpretability methods, SHAP is based on solid theoretical foundations and provides a fair allocation of feature contributions. It has been widely applied in individual prediction [53]. Equation (1) [54] shows the precise formula of SHAP.

Here, f is the prediction function, x denotes the feature vector, n signifies the number of features, and xS/T is the observed value for all features, excluding T. By computing SHAP values across all features, a contribution matrix can be constructed, offering a clear breakdown of their roles in the prediction and enabling deeper insight into the model’s decision process. The SHAP value is calculated using Equation (2) for a particular feature.

SHAP provides both global and local interpretability methods for clarifying machine learning models. Its interpretability focuses on the model’s performance across the entire dataset, emphasizing the influence of features on predictions and visualizing feature importance and trends through summary plots. In contrast, local interpretability examines individual samples, explaining how the model predicts outcomes for specific instances, with force plots intuitively showing each feature’s contribution to a single prediction. By fairly allocating variable contributions, SHAP values offer robust interpretability at both global and local levels, while their visualization capabilities address the interpretability limitations of traditional linear regression models. Deep learning models excel at handling complex data and tasks, efficiently training on large datasets and capturing intricate patterns for nonlinear mapping. However, due to their high complexity, deep learning models are often considered “black boxes” with limited interpretability, posing challenges for specific applications. This study integrates DNN and SHAP methods to address this limitation and construct a new interpretable PM2.5 estimation model. The model structure is presented in Figure 3. The model was trained using both feature data and monitoring station data. The DNN model incorporates a three-layer hidden structure, using the Rectified Linear Unit activation function for computational simplicity and efficient training [55]. The Adam optimizer was employed during training to ensure stability and maintain an optimal learning range for parameter updates throughout iterations. The weights and biases of each layer were optimized by minimizing the loss function. The specific parameters of the DNN are provided in Table A1. After training, a SHAP analysis was performed on the DNN model to reveal the internal mechanisms of the “black box” model. Calculating SHAP values for each feature clarified the global impact and contribution of features to the model’s predictions, significantly enhancing the model’s transparency and interpretability.

Figure 3.

Structure diagram of the new interpretable PM2.5 estimation model.

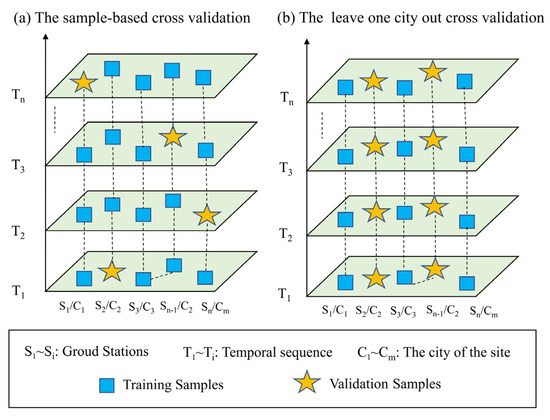

Finally, tenfold cross-validation based on samples (Figure 4a) and leave-one-city-out cross validation (Figure 4b) was used to evaluate the model [56]. The sample is randomly partitioned into ten subsets in the tenfold cross-validation process. In each iteration, nine subsets are used for training the model, while the remaining subset is set aside for validation. This procedure is repeated ten times. Similarly, the leave-one-city-out cross-validation method validates using data from all ground monitoring stations in a single city, while the data from monitoring stations in other cities is used for model training. This ensures that all monitoring stations across the study area are validated before concluding the validation process. Overall, the sample-based cross-validation evaluates the general performance of the model, while the leave-one-city-out cross-validation provides a more precise assessment of its spatial performance.

Figure 4.

Two model evaluation methods. (a) The method of tenfold cross-validation based on samples; (b) The method of leave-one-city-out cross-validation.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Feature Selection and Importance Analysis

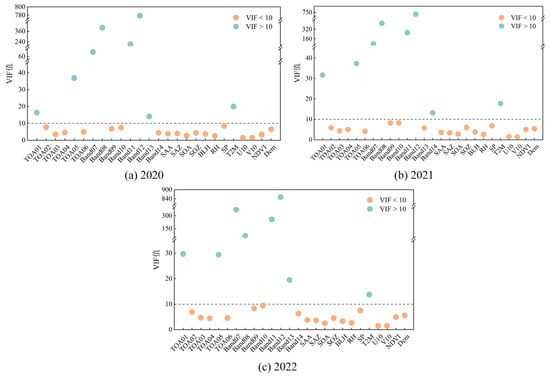

3.1.1. Result of Multicollinearity Test

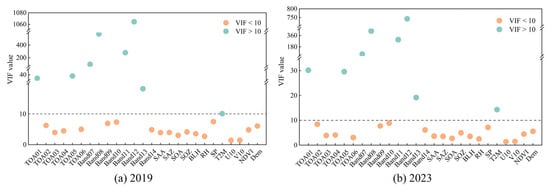

In machine learning algorithms, a strong linear relationship between input parameters may affect the model’s estimation performance [50]. Building on previous methods, we applied the VIF to assess the multicollinearity of the parameters used in the study [39,57]. The VIF results for all parameters from 2019 to 2023 are shown in Figure 5 and Figure A1. Parameters with strong multicollinearity (VIF ≥ 10) were sequentially eliminated, and those with VIF < 10 (including TOA02, TOA03, TOA04, TOA06, Band09, Band10, Band14, SAA, SAZ, SOA, SOZ, BLH, RH, SP, U10, V10, NDVI, DEM) were retained. These selected features passed the multicollinearity test and served as the optimal inputs for constructing the PM2.5 estimation model.

Figure 5.

VIF values of Parameters for 2019 and 2023.

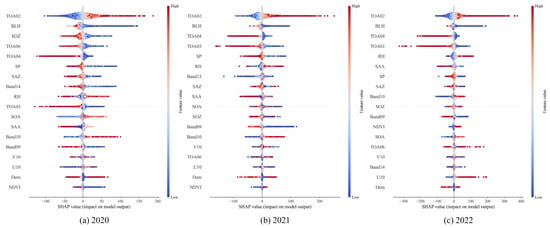

3.1.2. Analysis of Feature Interpretability

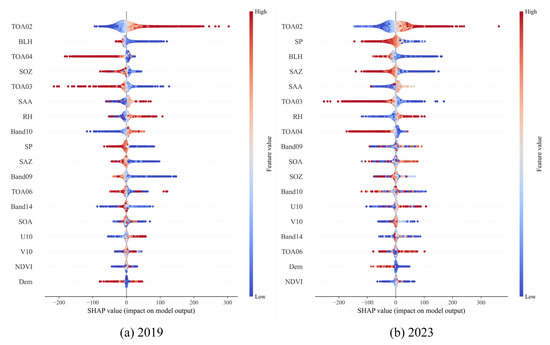

To understand the best model from a global perspective, the Gradient Explainer from the SHAP framework was used. The SHAP waterfall plot (Figure 6 and Figure A1) illustrates feature importance and their contributions to predictions. Features are ranked by influence along the vertical axis, while the horizontal axis shows SHAP values, reflecting positive or negative effects on the output. Each point corresponds to a sample, with its spread indicating aggregation and its color denoting feature magnitude—red for higher values and blue for lower values.

Figure 6.

Waterfall plot of SHAP values for parameters for 2019 and 2023. (a) The SHAP values for 2019. (b) The SHAP values for 2023.

Figure 6 and Figure A2 illustrates SHAP values and their respective importance rankings for all features from 2019 to 2023. The figure reveals that the TOA02 band has the greatest impact on the model, with higher values contributing positively and lower values exerting a negative effect. This indicates a strong association between the TOA02 band and the model’s predictive outcomes, likely linked to atmospheric or surface radiation characteristics. Similarly, the TOA04, TOA03, and TOA06 bands exhibit clear positive and negative effects under varying conditions. Higher values of these bands tend to negatively influence the model, while lower values contribute positively. TOA02 and TOA03 are the visible and near-infrared bands of FY-4A. Higher fine-particulate concentrations in the visible and near-infrared wavelengths correspond to lower atmospheric transmittance, with this negative correlation being particularly evident in the near-infrared band. TOA04 and TOA06 are shortwave infrared bands, and their combination may play a role in separating clouds from fine-particulate and identifying particle size. In contrast, Band09, Band10, and Band14 fall within the mid-infrared and long-wave infrared regions and have relatively weak impacts on model predictions. However, these bands are important for capturing atmospheric water vapor, which may influence the aggregation of fine particles. Therefore, under certain climatic or geographical conditions, they may still exert a non-negligible influence on the model’s PM2.5 estimation.

The BLH parameter, which governs pollutants’ vertical diffusion capacity, strongly correlates with air quality predictions and significantly influences the model. A lower BLH hinders the vertical diffusion of PM2.5, leading to higher concentrations, whereas a higher BLH promotes vertical diffusion, resulting in lower PM2.5 concentrations. This physical phenomenon is also consistent with the SHAP results, which show a negative correlation of BLH in the model’s PM2.5 estimation process. Other meteorological parameters, such as RH, SP, U10, and V10, contribute less prominently but still affect pollutant diffusion and reactions, thereby influencing prediction outcomes. Angular data, including SAA, SAZ, SOA, and SOZ, show considerable variability in their contributions across years. These parameters determine the radiation transmission path and influence aerosol inversion. Finally, NDVI and DEM represent surface vegetation and terrain conditions, respectively. Although their contributions are minimal, changes in vegetation and terrain can indirectly affect model predictions by altering surface reflectance, air quality, and the accumulation or dispersion of local pollutants.

In summary, TOA02, BLH, TOA04, and TOA03 consistently contributed significantly to the model across different years. These features play a major role in the prediction results, as they collectively influence the observation of atmospheric conditions and the model’s overall accuracy. Other features also affect the model’s results to a certain extent, indicating that atmospheric diffusion conditions and meteorological factors are essential for air quality prediction.

3.2. Model Performance

3.2.1. Model Accuracy

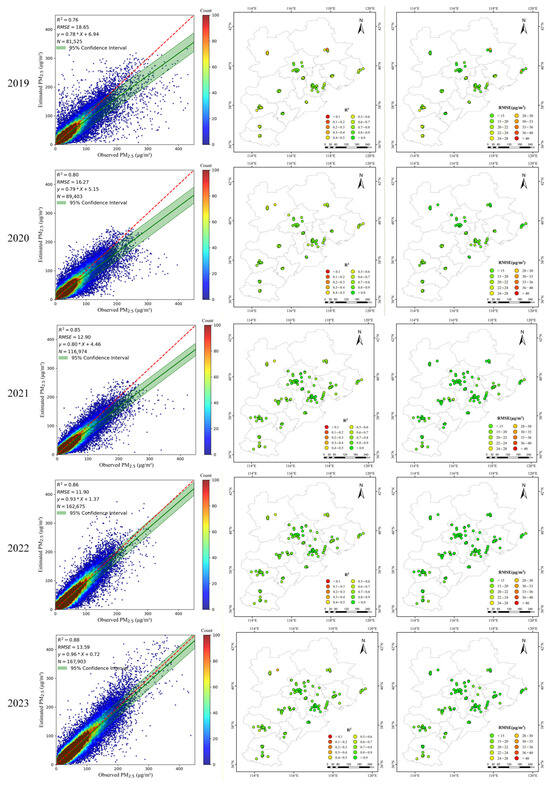

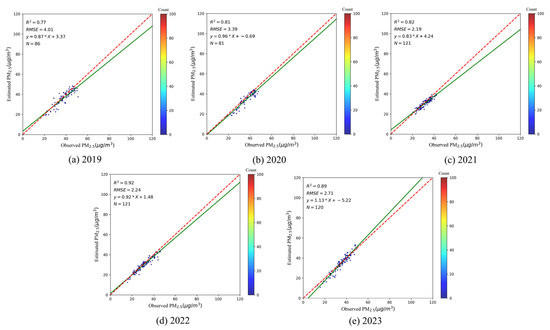

This study used feature parameters that passed multicollinearity tests as the optimal input for the model, constructing a new interpretable PM2.5 estimation model. Figure 7 shows the tenfold cross-validation results of the model estimates from 2019 to 2023 and the accuracy and uncertainty at each site. Across different years, the overall R2 of the model ranged from 0.76 and 0.88, with an average R2 of 0.83 and root mean square error (RMSE) maintained below 15 μg/m3. The accuracy of the model differed among sites in different regions. The model accuracy for 2019–2020 in Zhangjiakou and Chengde ranged from 0.5 to 0.6, which is relatively lower compared to the southeastern region of BTH, where R2 values ranged from 0.7 to 0.8. This discrepancy may be attributed to the higher number of ground stations in the southeast part of BTH, which allowed for more comprehensive model training.

Figure 7.

The results of tenfold cross-validation based on samples in the BTH region from 2019 to 2023.

In contrast, Zhangjiakou and Chengde, characterized by higher altitudes and complex topography, exhibit relatively lower model performance, indicating that the model may have certain limitations in handling complex terrain. From 2021 to 2023, the number of ground monitoring stations increased to 121, gradually improving model accuracy. During this period, the R2 values for most sites in the BTH region ranged from 0.8 to 0.9. Overall, the interpretable PM2.5 estimation model we constructed demonstrates strong performance in the BTH region, particularly from 2021 to 2023, with the overall R2 value exceeding 0.85.

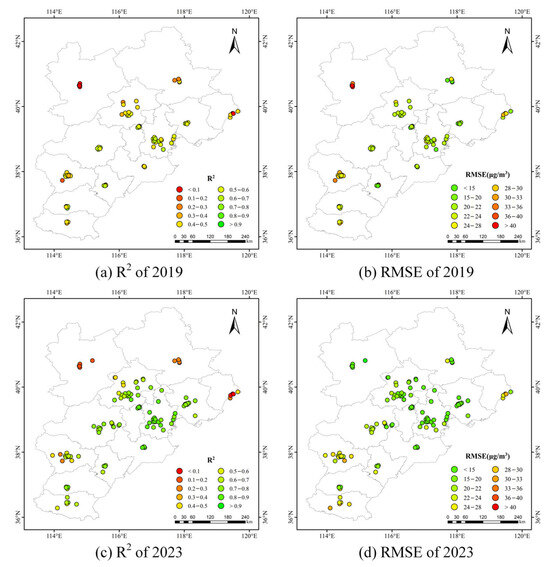

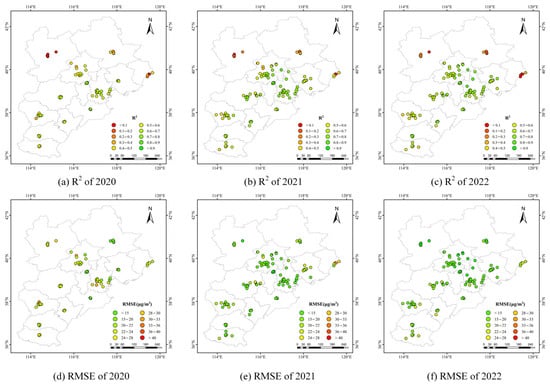

3.2.2. Spatial Expansion Performance

The leave-one-city-out cross-validation was employed to assess the model’s spatial generalization. Figure 8 shows the corresponding R2 and RMSE values for the BTH region in 2019 and 2023. The results for 2020–2022 are shown in Figure A3. Over this period, the percentage of models achieving an R2 value greater than 0.6 was 24%, 44%, 70%, 75%, and 76%, respectively. This progression indicates a consistent upward trend in the proportion of models with an R2 greater than 0.6 over the years.

Figure 8.

The R2 and RMSE values of the model based on leave-one-city-out cross-validation in the BTH region for 2019 and 2023.

In 2019 and 2020, over 60% of urban stations in the BTH region exhibited an RMSE greater than 24 μg/m3. In contrast, in 2021, 2022, and 2023, 91%, 95%, and 80% of urban stations, respectively, had an RMSE below 24 μg/m3. The annual increase in the model’s R2 and the corresponding decrease in RMSE indicate progressive enhancement in the model’s performance over time. Generally, our model exhibited strong performance in areas with a high density of monitoring sites, such as Beijing and Tianjin, where the annual model R2 remains above 0.6. However, the model underperformed in Zhangjiakou, Chengde, and Qinhuangdao, with site R2 values below 0.5. This variability in model performance across cities was primarily attributed to economic development and population density disparities, which led to differing urban pollution levels. This phenomenon indicates that the model may perform poorly in regions with large disparities in economic development.

3.3. Temporal and Spatial Distribution of PM2.5

3.3.1. Analysis of Annual and Seasonal Variations of PM2.5

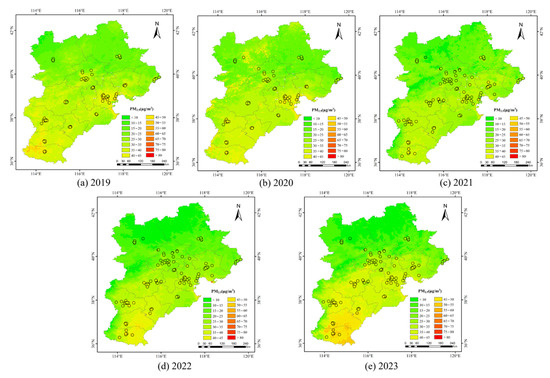

The yearly average PM2.5 predictions and ground observations for the BTH area between 2019 and 2023 are shown in Figure 9a–e. The spatial pattern remained stable, with higher concentrations in southern areas and lower concentrations in northern areas. Notably, the southeast exhibited much higher PM2.5 than the northwest, mainly due to dense populations and rapid economic growth in cities like Beijing and Tianjin, where industrial and residential activities drive significant emissions. Additionally, topographical factors played a role, as the Taihang Mountains blocked pollutant dispersion, further exacerbating concentrations in the southeast. By contrast, the northwest experienced reduced human activity and thus lower PM2.5 levels. From 2019 to 2022, annual averages declined steadily but rose slightly in 2023, largely due to the effects of COVID-19 restrictions between 2020 and 2022, when travel and non-essential production were curtailed. Strict lockdown measures significantly reduced anthropogenic emissions, leading to a substantial decrease in air pollution. However, at the beginning of 2023, as the COVID-19 pandemic subsided, human production and daily activities increased significantly, resulting in a resurgence of air pollution [58]. Figure 10 illustrates the fitting accuracy between the estimated annual average PM2.5 concentrations and ground monitoring values. From 2019 to 2023, the R2 value primarily ranged from 0.8 to 0.9, and the RMSE remained between 2 and 4 μg/m3, indicating that our estimation results are consistent with ground monitoring values.

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of estimated and ground-monitored annual average PM2.5 concentration in the BTH region from 2019 to 2023.

Figure 10.

Fitting scatter plot of estimated and ground-monitored PM2.5 values from 2019 to 2023.

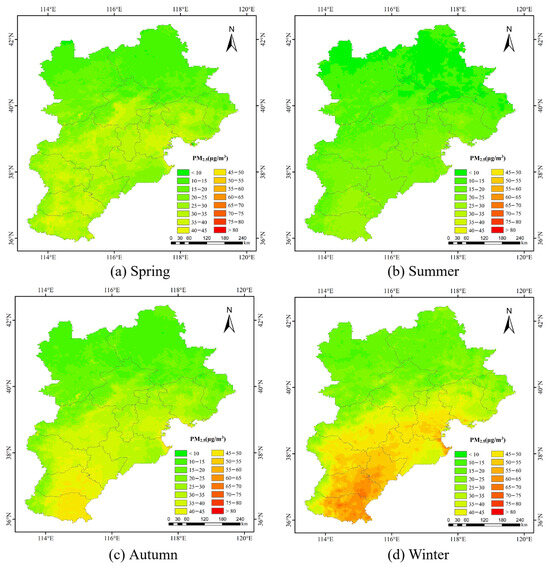

Figure 11 shows the seasonal average distribution of PM2.5 concentrations in the BTH region from 2019 to 2023. It exhibited significant seasonal differences, with the overall trend being winter > spring > autumn > summer (Figure 11a–d). This phenomenon was attributed to several factors. During winter, heating in northern regions relied heavily on coal combustion, significantly increasing pollutant emissions. Additionally, low temperatures and reduced atmospheric boundary layer heights during winter hinder the pollutant dispersion, further exacerbating PM2.5 pollution. In contrast, lower PM2.5 concentrations in summer were likely due to higher temperatures, active vertical atmospheric movements that facilitate pollutant dispersion, and abundant precipitation that promoted the sedimentation of PM2.5.

Figure 11.

Seasonal average PM2.5 concentration results in the BTH region from 2019 to 2023.

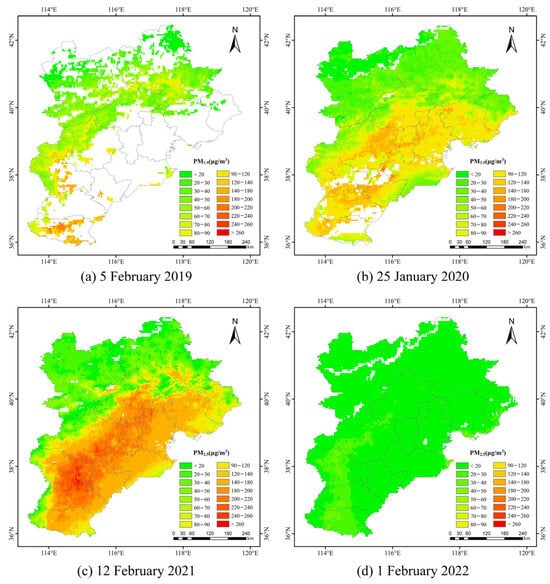

3.3.2. Variations in Pollution During Different Spring Festivals

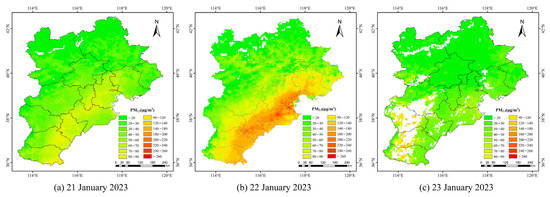

The geographical distribution of PM2.5 levels during the Spring Festival from 2019 to 2022 is shown in Figure A4. Compared with 2019 and 2020, the Spring Festival in 2021 was affected by adverse meteorological conditions and fireworks, leading to severe air pollution in the BTH region. In contrast, during the Spring Festival of 2022, the nationwide ban on fireworks and firecrackers, combined with the influence of cold air, significantly improved air quality compared with the Spring Festivals of 2019, 2020, and 2021. Figure 12 further illustrates the spatial pattern of PM2.5 concentrations before and after the 2023 Spring Festival. The results show that on the day before the Spring Festival, PM2.5 concentrations in the central and southern parts of the BTH region were relatively low. This was partly due to strict daytime restrictions on firework activities and partly because the peak period of New Year’s Eve firework displays had not yet occurred. On January 22, following the peak firework activities during the night of New Year’s Eve, PM2.5 concentrations across the central and southern parts rose sharply. Despite government efforts to restrict fireworks and firecrackers, traditional folk customs make it challenging to completely prohibit their use during the Spring Festival [59]. By January 23, after the peak firework period had passed, PM2.5 levels began to decline again.

Figure 12.

Spatial pattern of PM2.5 concentrations before and after the 2023 Spring Festival.

4. Discussion

To evaluate the PM2.5 estimation model developed in this study, we compared it with Geoi-DBN, Geoi-LSTM, and the Deep Bayesian model. The performance of these models is shown in Table 2. Compared with Geoi-DBN, our model not only achieves higher spatiotemporal resolution but also outperforms Geoi-DBN in terms of R2 and RMSE in most years. Compared with Geoi-LSTM, our model shows better accuracy for 2021–2023, though its performance in 2019 and 2020 is slightly lower than Geoi-LSTM. Both models achieve hourly temporal resolution, but our model slightly outperforms Geoi-LSTM in spatial resolution. Although the Deep Bayesian model can reach a spatial resolution of up to 1 km, its accuracy is lower than that of our DNN model. Overall, while the DNN model developed in this study did not achieve the best training performance in certain years due to limited ground station data, it is able to provide high-accuracy PM2.5 estimates at high spatiotemporal resolution in most years. In future work, for years with limited monitoring sites or small sample sizes, a transfer learning approach similar to that proposed by Li et al. [60] could be employed, whereby abundant samples from other years are leveraged through pre-training and fine-tuning to enhance the overall PM2.5 estimation performance of the model for years with insufficient training data.

Table 2.

The cross-validation performance of the models.

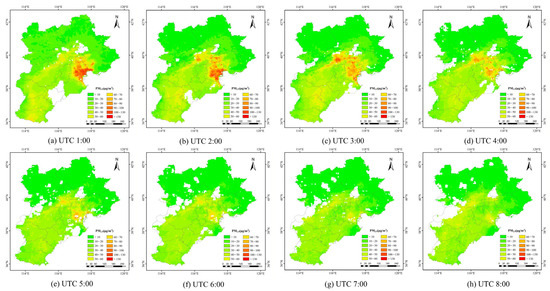

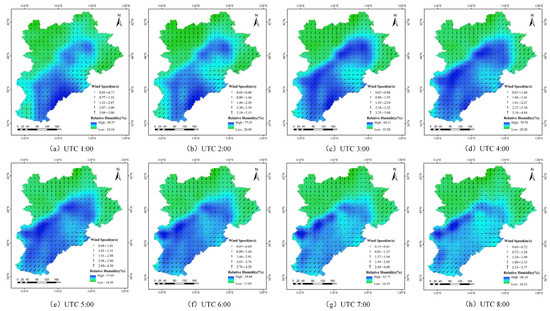

To highlight the practical value of this study, we analyzed a severe air pollution event in the BTH region on 22 September 2019 [61]. Figure 13 and Figure 14 show the PM2.5 variation process and hourly relative humidity, wind speed, and wind direction from 1:00 to 8:00 UTC on 22 September 2019. During this pollution episode, the model correctly predicted the spatial distribution of PM2.5 and showed the temporal dynamics of its sources and sinks. This pollution event was primarily influenced by emissions from Tangshan and Tianjin, with pollutants continuously transported southwest over time. From 1:00 to 3:00 UTC, the majority of the pollution from PM2.5 was found in Beijing, Tianjin, and Tangshan. This was attributed to high relative humidity in the region, exceeding 60%, which facilitated the formation and accumulation of PM2.5. Simultaneously, low wind speeds (0.5–2 m/s) and relatively stable wind direction hindered pollutant dispersion, leading to increased pollution levels. From 4:00 UTC, the PM2.5 concentration area expanded southwest, and concentrations gradually decreased. This may have been due to the gradual increase in wind speed and the shift to a southerly wind direction, which promoted pollutant transport from north to south. From 5:00 to 6:00, wind speed increased to 2–4 m/s, enhancing the horizontal transport of pollutants. From 7:00 to 8:00 UTC, the wind speed remained high, and the consistent wind direction further enhanced pollutant dilution and removal. Additionally, decreased relative humidity in some areas reduced atmospheric water vapor, inhibiting the formation of secondary particles and contributing to the dissipation of PM2.5. This analysis of the major pollution event in the BTH region verified the model’s capability to capture dynamic pollution episodes, demonstrating its applicability for monitoring atmospheric pollution events.

Figure 13.

PM2.5 concentration process in the BTH region from 1:00 to 8:00 UTC on 22 September 2019.

Figure 14.

Relative humidity, wind speed, and the wind direction in the BTH region from 1:00 to 8:00 UTC on 22 September 2019.

Using FY-4A satellite TOA data, this study generated a reliable long-term PM2.5 dataset for 2019–2023. While it proved valuable for monitoring severe pollution events, certain limitations remain and require further improvement. First, due to differences in economic development and population density across cities, pollution levels varied with the degree of urban development in each region. Therefore, model performance varied across cities, highlighting the need for future studies to adopt strategies such as ensemble learning or transfer learning to enhance the model’s spatial generalization capability. Second, due to atmospheric and surface influences, TOA data from a single spaceborne optical sensor cannot simultaneously achieve high temporal and spatial resolution. This limitation restricts the acquisition of high spatiotemporal resolution PM2.5 data, thereby hindering studies on urban pollution dynamics and source identification. Therefore, future efforts should focus on multi-source PM2.5 data fusion to produce high-quality PM2.5 datasets, providing stronger data support for air quality monitoring in urban areas.

5. Conclusions

This study estimated surface high-temporal-resolution PM2.5 concentrations from 2019 to 2023 based on FY-4A TOA reflectance data, meteorological variables, and auxiliary information. By performing multicollinearity testing on all feature parameters, the ideal combination of feature parameters for estimating PM2.5 was determined. Additionally, to enhance interpretability, the PM2.5 estimation model applies the SHAP method to a DNN to quantify feature contributions. The following conclusions were drawn:

(1) Redundancy and multicollinearity among feature parameters can reduce the performance of machine learning models. A multicollinearity test was conducted on all feature parameters from 2019 to 2023 using the VIF method. Features with strong multicollinearity (VIF ≥ 10) were eliminated, while those with VIF < 10 were retained. The optimal feature combination for the estimation model included TOA02, TOA03, TOA04, TOA06, Band09, Band10, Band14, SAA, SAZ, SOA, SOZ, BLH, RH, SP, U10, V10, NDVI, and DEM.

(2) The SHAP method was introduced to quantify the contribution of each feature parameter to model predictions, significantly enhancing interpretability. Among the features, TOA02, TOA03, TOA04, and BLH made the largest contributions to the model across different years.

(3) The new interpretable model demonstrated strong performance in the BTH region. The R2 values of the model from 2019 to 2023 were 0.76, 0.8, 0.85, 0.86, and 0.88, respectively. Based on leave-one-city-out cross-validation, the model showed good spatial expansion performance in the southeastern part of BTH, with annual R2 values consistently above 0.7. However, the model performs poorly in the northwestern areas of BTH, such as Zhangjiakou, Chengde, and Qinhuangdao, with model R2 below 0.5. This indicates that the model may perform poorly in regions with large economic disparities.

(4) An hourly high-temporal-resolution PM2.5 analysis of pollution events in the BTH region was conducted to verify the model’s capability to dynamically capture pollution episodes, demonstrating its practical significance for monitoring atmospheric pollution events.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L. and W.Z.; Data curation, X.C.; Formal analysis, X.C.; Funding acquisition, W.Z.; Methodology, B.L. and X.C.; Project administration, J.Y.; Resources, W.Z.; Software, T.L.; Supervision, Z.H.; Validation, X.C.; Visualization, B.L.; Writing—original draft, B.L. and X.C.; Writing—review and editing, B.L., W.Z. and M.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hebei Natural Science Foundation, Grant No. D2024409002; the Department of Science and Technology of Hebei Province Central Guidance of Local Science and Technology Development Funds Project, Grant No. 246Z7602G; and Hebei Province Graduate Student Innovation Ability Training Funding Project, Grant No. CXZZSS2025130.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this article can be found online at https://mega.nz/folder/6JkAkbyR#wbuJcVmqDSZk8L-6IBGe4w (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support of the China National Environmental Monitoring Center in providing ground PM2.5 monitoring data, the National Satellite Meteorological Center in providing FY-4A satellite data, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in providing meteorological data, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in providing NDVI and DEM data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FY-4A | Feng-Yun-4A |

| PM2.5 | Particulate matter with a particle size of smaller than 2.5 μm |

| TOA | Top-of-Atmosphere |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| BTH | Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei |

| AGRI | Advanced Geostationary Radiation Imager |

| AOD | aerosol optical depth |

| DBN | Deep Belief Network |

| Geoi-DBN | Geographic Intelligent DBN |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Network |

| Geoi-LSTM | Geographic Intelligent LSTM |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| CNEMC | China Environmental Monitoring Center |

| SOA, SAZ, SAA, SOZ | four observation angles |

| CLM | cloud mask product |

| SP | surface pressure |

| T2M | 2 m air temperature |

| BLH | boundary layer height |

| U10M V10M | eastward and northward wind at 10 m above ground |

| RH | relative humidity |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| UTC | Coordinated Universal Time |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Parameters of the DNN model.

Table A1.

Parameters of the DNN model.

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Hidden Layer | [1024, 512, 256] |

| Learn Rate | 0.0000236 |

| batch size | 100 |

| epochs | 100 |

| Dropout Value | [0.2068419, 0.2535549, 0.2107006] |

| L2 Regularization Factor | 0.0965833 |

| training set: validation set | 9:1 |

Figure A1.

VIF values of Parameters from 2020 to 2022.

Figure A2.

Waterfall plot of SHAP values for parameters from 2020 to 2022.

Figure A3.

The R2 and RMSE values of the model based on leave-one-city-out cross-validation in the BTH region from 2020 to2022.

Figure A4.

Spatial pattern of PM2.5 concentrations during the Spring Festival from 2019 to 2022.

References

- Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; Abegaz, K.H.; Abolhassani, H.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Global Burden of 87 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hoek, G. Long-Term Exposure to PM and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; He, J.; Wu, L.; Jin, T.; Chen, X.; Li, R.; Ren, P.; Zhang, L.; Mao, H. Health Burden Attributable to Ambient PM2.5 in China. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, D.; Zheng, B.; Li, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, Q. Spatiotemporal Continuous Estimates of PM2.5 Concentrations in China, 2000–2016: A Machine Learning Method with Inputs from Satellites, Chemical Transport Model, and Ground Observations. Environ. Int. 2019, 123, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohra, K.; Vodonos, A.; Schwartz, J.; Marais, E.A.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Mickley, L.J. Global Mortality from Outdoor Fine Particle Pollution Generated by Fossil Fuel Combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pui, D.Y.H.; Chen, S.C.; Zuo, Z. PM2.5 in China: Measurements, Sources, Visibility and Health Effects, and Mitigation. Particuology 2014, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choobari, O.A.; Zawar-Reza, P.; Sturman, A. The Global Distribution of Mineral Dust and Its Impacts on the Climate System: A Review. Atmos. Res. 2014, 138, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, J.S.; Marshall, J.D.; Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M. Addressing Global Mortality from Ambient PM2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 8057–8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhodaidi, A.; Attiah, A.; Mhawish, A.; Hakeem, A. The Role of Machine Learning in Enhancing Particulate Matter Estimation: A Systematic Literature Review. Technologies 2024, 12, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, M.; Ding, Y. Exploring the Effect of Economic and Environment Factors on PM2.5 Concentration: A Case Study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yao, R.; Sun, P.; Ge, C.; Ma, Z.; Bian, Y.; Liu, R. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Forces of PM2.5 in Urban Agglomerations in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, L. Investigating the Performance of Satellite-Based Models in Estimating the Surface PM2.5 over China. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Dong, X.; Kong, Z.; Dong, K. Does National Air Quality Monitoring Reduce Local Air Pollution? The Case of PM2.5 for China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, Q.; Shen, H. Hourly PM2.5 Concentration Monitoring With Spatiotemporal Continuity by the Fusion of Satellite and Station Observations. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 8019–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratoulias, D.; Nuthammachot, N.; Dejchanchaiwong, R.; Tekasakul, P.; Carmichael, G.R. Recent Developments in Satellite Remote Sensing for Air Pollution Surveillance in Support of Sustainable Development Goals. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Deng, R.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Cao, B.; Liu, Y.; Hua, Z.; Yu, J. Estimating High-Spatial-Resolution Daily PM2.5 Mass Concentration from Satellite Top-of-Atmosphere Reflectance Based on an Improved Random Forest Model. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 302, 119724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Dey, S.; Christopher, S.; Liu, R.; Bi, J.; Balyan, P.; Liu, Y. A Review of Statistical Methods Used for Developing Large-Scale and Long-Term PM2.5 Models from Satellite Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, S.; Fan, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Y. Satellite Remote Sensing for Estimating PM2.5 and Its Components. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2021, 7, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Waller, L.A.; Lyapustin, A.; Wang, Y.; Al-Hamdan, M.Z.; Crosson, W.L.; Estes, M.G.; Estes, S.M.; Quattrochi, D.A.; Puttaswamy, S.J.; et al. Estimating Ground-Level PM2.5 Concentrations in the Southeastern United States Using MAIAC AOD Retrievals and a Two-Stage Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Weng, F.; Li, Z.; Cribb, M.C. Hourly PM2.5 Estimates from a Geostationary Satellite Based on an Ensemble Learning Algorithm and Their Spatiotemporal Patterns over Central East China. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Levy, R.C.; Mattoo, S.; Remer, L.A.; Holz, R.E.; Heidinger, A.K. Applying the Dark Target Aerosol Algorithm with Advanced Himawari Imager Observations during the KORUS-AQ Field Campaign. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 6557–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ren, H.; Liu, R.; Fan, W.; Qin, Q.; Qin, L.; Tao, Y.; Yang, S. Simultaneous Retrieval of Land Surface Temperature and Emissivity from Chinese Geostationary Satellite Fengyun-4B Image. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023—2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 7101–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Gao, L.; Chen, L.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Yan, H.; Zhang, X.; Lu, F.; Zhang, X. An Adaptive Dark-Target Algorithm for Retrieving Land AOD Applied to FY-4B/AGRI Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 14035–14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Min, J.; Shen, F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Yang, C.; Zhang, P. Aerosol Data Assimilation Using Data from Fengyun-4A, a next-Generation Geostationary Meteorological Satellite. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 237, 117695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, D.; Pei, L.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Bian, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yao, W.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, L. Estimating PM2.5 Concentrations via Random Forest Method Using Satellite, Auxiliary, and Ground-Level Station Dataset at Multiple Temporal Scales across China in 2017. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Gong, J.; Zhou, J. Estimating Hourly PM2.5 Concentrations in Beijing with Satellite Aerosol Optical Depth and a Random Forest Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 144502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Pan, L.; Sun, Y. Estimating PM2.5 Concentrations in a Central Region of China Using a Three-Stage Model. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.J.; Seong, M.; Shahid, B.; Bai, H. Estimating PM2.5 Exposures and Cardiovascular Disease Risks in the Yangtze River Delta Region Using a Spatiotemporal Convolutional Approach to Fill Gaps in Satellite Data. Toxics 2025, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Bergin, M.H.; Hu, S.; Miller, J.; Carlson, D.E. Estimating Ground-Level PM2.5 Using Micro-Satellite Images by a Convolutional Neural Network and Random Forest Approach. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 230, 117451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Jiang, P.; Ma, F.; Gao, Y.; Gu, X.; Luan, Q. Research on Time Series Interpolation and Reconstruction of Multi-Source Remote Sensing AOD Product Data Using Machine Learning Methods. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Li, T.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, L. Estimating Regional Ground-Level PM2.5 Directly From Satellite Top-of-Atmosphere Reflectance Using Deep Belief Networks. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 13875–13886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shen, H.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Estimating Ground-Level PM2.5 by Fusing Satellite and Station Observations: A Geo-Intelligent Deep Learning Approach. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 11985–11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yuan, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, L. Estimate Hourly PM2.5 Concentrations from Himawari-8 TOA Reflectance Directly Using Geo-Intelligent Long Short-Term Memory Network. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Qin, K.; Cui, Y.; Li, D.; Bilal, M. Estimation of Hourly Ground-Level PM. Concentration Based on Himawari-8 Apparent Reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kong, P.; Jiang, P.; Wu, Y. Estimation of PM2.5 Concentration Using Deep Bayesian Model Considering Spatial Multiscale. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zang, Z.; Luo, N.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z. New Interpretable Deep Learning Model to Monitor Real-Time PM2.5 Concentrations from Satellite Data. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, C.; Husi, L. A Spatial-Temporal Interpretable Deep Learning Model for Improving Interpretability and Predictive Accuracy of Satellite-Based PM2.5. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Yu, H.; Shi, Z.; Liu, J.-X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huangfu, Y.; Han, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Knowledge-Guided Machine Learning Reveals Pivotal Drivers for Gas-to-Particle Conversion of Atmospheric Nitrate. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2024, 19, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; He, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Li, J.; Gu, X. Mapping PM2.5 Concentration from the Top-of-Atmosphere Reflectance of Himawari-8 via an Ensemble Stacking Model. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 330, 120560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wong, M.S.; Liu, C.H.; Zhu, R. Synergistic Data Fusion of Satellite Observations and In-Situ Measurements for Hourly PM2.5 Estimation Based on Hierarchical Geospatial Long Short-Term Memory. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 286, 119257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Mao, F.; Zang, L.; Chen, J.; Lu, X.; Hong, J. Retrieving PM2.5 with High Spatio-Temporal Coverage by TOA Reflectance of Himawari-8. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, T.; Yin, F.; Ma, Y. Exploring the Detailed Spatiotemporal Characteristics of PM2.5: Generating a Full-Coverage and Hourly PM2.5 Dataset in the Sichuan Basin, China. Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yao, F.; Li, W.; Si, M. VIIRS-Based Remote Sensing Estimation of Ground-Level PM2.5 Concentrations in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei: A Spatiotemporal Statistical Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 184, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Park, R.J.; Lee, H.M.; Lee, S.; Jo, D.S.; Jeong, J.I.; Henze, D.K.; Woo, J.H.; Ban, S.J.; Lee, M.D.; et al. Impacts of Local vs. Trans-Boundary Emissions from Different Sectors on PM2.5 Exposure in South Korea during the KORUS-AQ Campaign. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 203, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zeng, C.; Li, T.; Shen, H. Performance Comparison of Fengyun-4A and Himawari-8 in PM2.5 Estimation in China. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 271, 118898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, P.; Guan, X.; Wang, X.; Ge, J.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. High Temporal and Spatial Resolution PM2.5 Dataset Acquisition and Pollution Assessment Based on FY-4A TOAR Data and Deep Forest Model in China. Atmos. Res. 2022, 274, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Lin, W.; Taqi, S.A. The Impact of Wind and Non-Wind Factors on PM2.5 Levels. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 154, 119960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, J.; Hao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Cai, Z.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, M.; et al. Boundary Layer Structure and Scavenging Effect during a Typical Winter Haze-Fog Episode in a Core City of BTH Region, China. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 179, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Tan, Q.; Jiang, X.; Yang, F.; Jiang, W. Effects of Relative Humidity and PM2.5 Chemical Compositions on Visibility Impairment in Chengdu, China. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 86, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, L.; Saito, K.; Hotta, D. Analysis and Design of Covariance Inflation Methods Using Inflation Functions. Part 1: Theoretical Framework. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 3638–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mottaleb, S.A.A.; Métwalli, A.; Chehri, A.; Ahmed, H.Y.; Zeghid, M.; Khan, A.N. A QoS Classifier Based on Machine Learning for Next-Generation Optical Communication. Electronics 2022, 11, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wiens, J.; Lundberg, S. Shapley Flow: A Graph-Based Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Virtual, 13–15 April 2021; PMLR: San Diego, CA, USA, 2021; Volume 130, p. 721. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, J.-X.; Li, A.-D.; Zhou, L.-F. Review Study of Interpretation Methods for Future Interpretable Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 191969–191985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30, pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- She, L.; Zhang, H.K.; Li, Z.; de Leeuw, G.; Huang, B. Himawari-8 Aerosol Optical Depth (Aod) Retrieval Using a Deep Neural Network Trained Using Aeronet Observations. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Gu, X.; Yu, T. Estimation of Ground-Level PM2.5 Concentration at Night in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region with NPP/VIIRS Day/Night Band. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.B.; García, J.; López Martín, M.M.; Salmerón, R. Collinearity: Revisiting the Variance Inflation Factor in Ridge Regression. J. Appl. Stat. 2015, 42, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Mao, F.; Hong, J.; Zang, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gan, Y.; Gong, W.; Xu, H. Improving PM2.5 Predictions during COVID-19 Lockdown by Assimilating Multi-Source Observations and Adjusting Emissions. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 297, 118783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkin, N.; Simayi, M.; Ablat, X.; Yahefu, P.; Maimaiti, B. Predicting Spatiotemporal Variations of PM2.5 Concentrations during Spring Festival for County-Level Cities in China Using VIIRS-DNB Data. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 294, 119484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, T.; Han, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L. Research Method on the Retrieval of Land Surface Temperature Based on Transfer Learning with a Deep Belief Network. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 6451–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Cheng, T.; Gu, X.; Guo, H.; Wu, Y.; Shi, S. Studying the Regional Transmission and Inferring the Local/External Contribution of Fine Particulate Matter Based on Multi-Source Observation: A Case Study in the East of North China Plain. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).