Abstract

For many years, Warsaw has been one of the European cities with the worst air quality, mainly due to harmful pollutants emitted by the residential sector and street traffic. This has led to high concentrations of particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and also benzo alpha pyrene (BaP), often exceeding WHO standards. However, since 2010, there have been significant changes in the Polish energy mix, with a trend towards a decrease in the share of coal, with a simultaneous increase in the share of renewable energy sources and natural gas. The article presents the related effects of the relevant central government’s policy during the last decade, further supported by the pro-environment decisions of the Warsaw authorities. We also present trends in the concentration of harmful pollutants over the 2012–2023 decade as recorded by the air quality monitoring system. Complete pollution records for 2023 come from two air quality monitoring systems recently operating in the city (GIOŚ official stationary and AIRLY IoT sensor systems). Since the sensors of these systems are located at different sites, the average annual records of both systems were compared indirectly, using the computer simulation results of key pollutant propagation in 2023. Based on the tests conducted, the hypothesis of equality of the annual means for the results from both the monitoring systems and the modeling is not rejected, despite a seemingly clear underestimation of the IoT sensors’ recordings versus the official ones. The reasons for these differences are investigated through a direct comparison and analysis of the average monthly recordings from the monitoring systems.

1. Introduction

At the beginning of the 20th century, Warsaw, the capital of Poland, like many other European conurbations, suffered from a high concentration of air pollutants, characteristic of urban atmospheric environments. Such a situation was a direct consequence of the almost total (90%) reliance of the Polish energy sector on coal combustion. At the beginning of the last decade, high concentrations of two types of particulate matter, PM10 (particulates with diameters up to 10 μm) and PM2.5 (particulates with diameters up to 2.5 μm), were the dominant pollutants responsible for very low air quality in Warsaw [1,2,3]. The main contributor to this pollution was the low-source emission from residential heating installations, comprising exhausts from household solid fuel furnaces, boilers, and cookers. Furthermore, the transport sector’s emissions [4] and the transboundary influx of pollutants contributed to high concentrations of particulate matter in the city [1,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The urban residential sector emitters, as well as the road transport, are also major sources of the carcinogen benzo-a-pyrene (BaP), concentrations of which significantly exceeded WHO limits during the period in question [10,11,12,13,14].

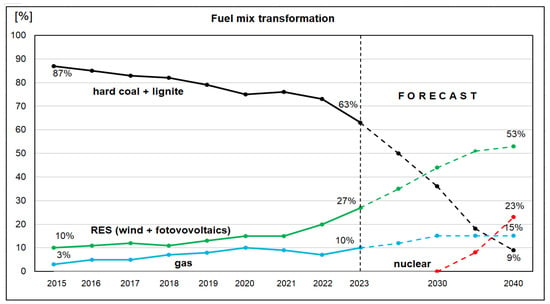

Over the past 20 years, Poland’s energy mix has undergone significant changes, with a decline in the share of coal and an increase in the share of renewable energy sources. At the same time, the share of natural gas in energy production has increased. For example, in 2010, 86.6% of energy came from coal, whereas by 2021, this percentage had fallen to 70.8%. Moreover, in 2023, coal’s share in gross electricity generation was reduced to about 60.5%. The national fuel mix influences the amount and composition of the external influx of pollutants into the city. However, there have been more fundamental changes in the Polish energy mix since 2010. In addition to the aforementioned reduction in the share of coal and increase in the use of renewable energy sources, the domestic energy sector’s emissions have been decreasing. Since 2010, CO2 and PM emissions per MWh produced have decreased by approximately 16.6% [15,16]. The modernization of the energy sector resulted in a radical diversification of energy sources.

At the same time, as the share of coal in Poland’s electricity generation fell, the contribution of renewables (including wind and photovoltaic energy) rose to over 27%, and the share of gas rose to about 10%. According to [17,18], anticipating the planned entry of nuclear power, an almost complete shift away from coal in power generation is expected by the end of the next decade (cf. Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The historical and forecasted (dotted lines) transformation in the fuel mix by 2040, adapted from [16]. Time scale modified for 2023–2040.

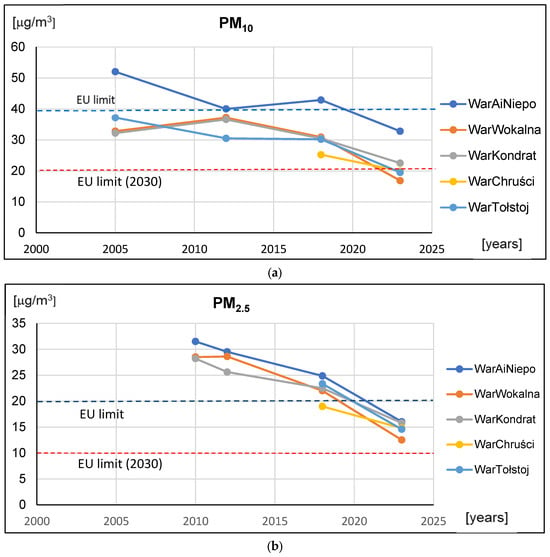

Over the last decade, a notable improvement in air quality has also been observed in Warsaw, primarily due to a significant reduction in the number of outdated cookers and furnaces. This was further supported by other diverse emission mitigation measures. A partial elimination of fossil fuel combustion in the residential sector, accompanied by a large expansion and modernization of the public transportation fleet, is just one of the measures that have helped improve air quality. As a result, the city-averaged PM10 concentration, which was close to 40 μg/m3 in 2010, decreased to approximately 20 μg/m3 by 2023. Similarly, the PM2.5 concentration, which exceeded 28 μg/m3 in 2010, decreased below 15 μg/m3 in 2023.

However, despite these improvements, Warsaw remains relatively high on the list of the most polluted cities in Europe, particularly during the colder months of the year [3,13]. Many homes still use coal and wood as heating fuels, which significantly worsens air quality. There are still, luckily brief, episodes of high particulate matter concentration. For example, a hazardous smog episode occurred on 2 March 2025, when Warsaw ranked among the most polluted large cities in the world.

The full effect of the steps taken by the central and local government will only become apparent once the transformation processes on the energy consumer side are taken into consideration. In particular, in previous years, the main source of air pollution at the local scale was the burning of coal in domestic heating installations. The problem was particularly acute in cities [1,5,19], where it was a source of serious health risks, including increased mortality. This issue also applies to Warsaw’s residential sector.

Our previous studies [10,11,20,21] present an analysis and assessment of the impact on air quality in Warsaw of the national Clean Air Program [17,22,23], which has been implemented since 2017. The primary objective of the program is precisely to eliminate old, poor-quality heat sources and replace them with low- or zero-emission installations (e.g., heat pumps or photovoltaics). In addition, the project scope includes the buildings’ insulation and the use of renewable sources of heat and electricity. In newly constructed residential buildings, low-emission installations will be subsidized. As a result of the Clean Air Program implementation between 2017 and 2023, more than 9000 outdated coal-fired boilers have been removed in Warsaw and replaced with low-emission installations [18,24,25]. It is estimated [20] that, to date (October 2025), around 90% of the several thousand obsolete heat sources operating in Warsaw at the beginning of the last decade have been successfully removed or replaced.

At the same time, the city authorities have been expanding public transport with an emphasis on minimizing its environmental impact. Warsaw’s public transport is based on a dense network of tram and bus lines, whose fleet is being modernized on an ongoing basis. This particularly involves purchases of low-emission buses (LNG, hybrid, and electric). By 2030, the number of conventionally powered buses will have been halved. Two metro lines were launched (in 1995 and 2015, respectively) and are being extended on an ongoing basis, while the construction of another line will soon begin (in 2028). According to the plans, there will be five metro lines by 2050.

The passenger car and light truck segment has a dominant impact on the total transportation sector emissions. A larger share of BEVs (Battery Electric Vehicle) and PHEVs (Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle) could bring improvements in this area, yet in Poland, the number of new registered cars of both types does not exceed 3% [26,27,28]. In contrast, in 2024, the share of classic standard HEV (Hybrid Electric Vehicle) and MHEV (Mild Hybrid Electric Vehicle) cars together accounted for 45% of all newly registered vehicles, which was one of the highest in the EU [29]. An important decision by the Warsaw authorities in this area was the launch of the Low Emission Zone in 2024 [20,21,28]. Due to some restrictions on the first stage, the effects of the zone’s implementation should be visible after the zone is fully operational in 2030.

This study aims to examine the results of all these activities on the air quality in the Warsaw conurbation. This includes scrutiny of the measurements from the sensors installed by the Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (GIOŚ), as well as the results of the simulations of pollutants dispersion performed earlier by the authors. The latter question required a new simulation for a recent year for a more complete comparison. The results are presented in the paper. To validate the model, measurements from the GIOŚ sensors were supplemented with data from a network of stationary IoT sensors. Differences between the measurements from these two sources are justified.

The methods used in the study and the significant improvement in air quality in Warsaw over the last decade, achieved due to pro-environmental decisions by the central government and relevant initiatives by local authorities, are discussed in Section 2. The related outcomes are illustrated by historical air quality monitoring data (GIOŚ monitoring system) and computer simulation results. The air quality in Warsaw at the end of the decade in question (in 2023) is assessed in Section 3, taking into account computer modeling results and two complementary air quality monitoring systems, GIOŚ and AIRLY IoT [30]. Complete monitoring data from 2023 is used in Section 4 to discuss, analyze, and compare the functioning of both systems. The reasons for certain differences in their records are indicated. Section 5 concludes.

2. Materials and Methods

The results of all pro-environment activities, both nationally and within the city limits, are reflected in the records of the air quality monitoring system. The Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (GIOŚ) tracking system operating in Warsaw includes continuous measurements of key pollutants, particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5), nitrogen oxides (NOx, NO2), aromatic hydrocarbons (BaP), among others [31]. The available measurement database, with different averaging intervals, covers the years 2000–2023 [32]. The number, location, and type (urban background, industrial, traffic) of the active air monitoring stations have varied over the above period. Currently, measurements of main pollutants of interest in Warsaw, such as particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, are carried out by the eight monitoring stations listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of the main (GIOŚ) monitoring stations in Warsaw, currently in operation.

In recent years, however, a network of Airly company [30] IoT sensors measures in Warsaw concentrations of PM10, PM2.5, and PM1. Around 160 Airly sensors have already been deployed in Warsaw and its neighboring municipalities. Table 2 lists selected Airly sensors located in the main districts of Warsaw and utilized in this analysis. Section 3 presents an extended, comparative analysis of the functionality and accuracy of both systems.

Table 2.

List of the selected Airly monitoring stations in Warsaw.

Figure 2a,b shows the temporal changes in average annual concentrations of key dust pollutants (PM10 and PM2.5) recorded by individual measuring stations in the selected years over the period 2005–2023, respectively [32]. Analogous diagrams for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) are presented in Figure 3a,b. The lack of records for some stations is due to the belated start of their activity.

Figure 2.

The annual mean PM10 (a) and PM2.5 (b) concentrations based on GIOŚ monitoring data.

Figure 3.

The annual mean NO2 (a) and BaP (b) concentrations based on GIOŚ monitoring data.

The above monitoring plots provide a basis for evaluating the results of computer modeling of air quality in Warsaw, both in previous years [10,11,20] as well as based on emission data for 2023. Simulations are performed by the regional-scale CALPUFF modeling system [33], and are based on the current emission dataset [34]. The results are presented and discussed in Section 3.

The monitoring records shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3 reflect implementation of the Clean Air Program in the last years, and, on the other hand, the positive impact of the improved technical efficiency of the new car fleet, being partially offset by the increasing total number of vehicles [26,29]. These data also reveal the specific nature of the MzWarAlNiepo station (traffic type), which is primarily dedicated to measuring traffic pollution on one of Warsaw’s main transportation routes. The difference with respect to the other (urban background) sensors’ records is particularly evident in the case of NO2 pollution (Figure 3) and also for PM10, as these pollutants strongly depend on traffic density. For other typical residential pollutants (PM2.5 and BaP), the indications of the station do not differ from those of the background-type station.

3. Results

3.1. Improved Air Quality Resulting from the Energy Transition

Historical concentration values of basic pollutants, recorded in the GIOŚ database, can be compared with computer modelling results for real emission data, presented in [11,20,21]. Relevant computer simulations were conducted for selected years, i.e., 2012, 2018, and 2023. The calculations, based on the real emission and meteorological dataset for the Warsaw conurbation, utilized the CALPUFF regional pollution dispersion model.

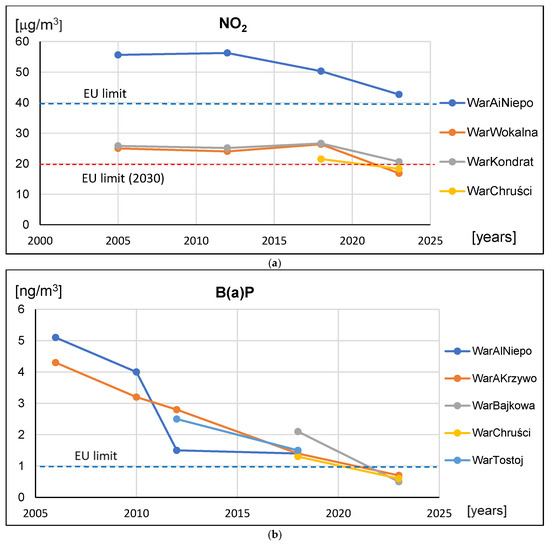

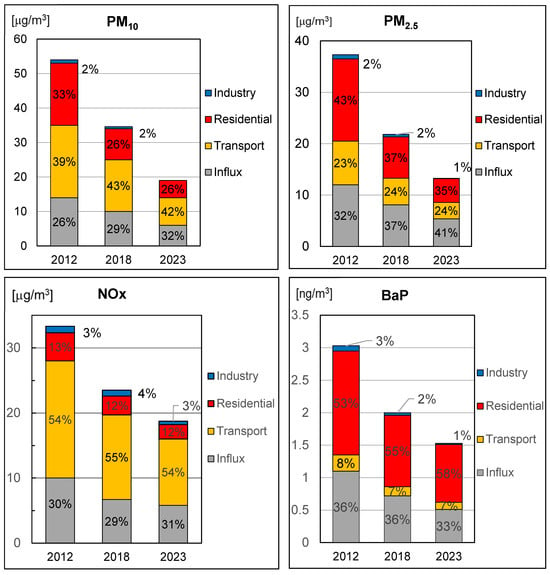

Figure 4 (upper panel) depicts changes in the annual average concentrations of particulate matter in Warsaw (PM10 and PM2.5). The data for the years 2012 and 2018 are drawn from previous simulation exercises [11,20,21]. These for 2023 come from simulation results for that year, which are presented in Section 3.2. They can be compared with the respective monitoring records shown in Figure 2. Analogous diagrams for nitrogen oxides (NOx) and benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) are presented in Figure 4, in the bottom panel, which can be compared with the monitoring records depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Reduction in the annual mean concentrations in the last decade, resulting from real-data simulation, for PM10 and PM2.5 (top), and NOx, BaP (bottom).

It can be noted that such a comparison primarily reflects the general trend of the changes. The data from the monitoring sensors (cf. Figure 2 and Figure 3) relate to a specific pollutant at a fixed location, while the results of computer modeling, presented in Figure 4, represent the concentration value averaged over the entire area. The simulations show that a particular type of air pollution, depending on the receptor location, can vary significantly not only in the concentration level, but also in the share of individual emission categories. This, in turn, can substantially affect the annual average concentration recorded by a particular sensor. However, the ranges of monitored and simulated values are generally comparable, particularly for PM10, PM2.5, and BaP pollutants. Notably, NOx concentrations (Figure 3) exhibit higher recording values at the MzWarAlNiep station, where they correspond to emissions from heavy traffic.

The publication [11] presents population exposure, mortality, and DALY (disability-adjusted life years) ratings attributed to the main emission categories in 2012. The average concentrations of PMs, NOx, and BaP were reduced in 2023 by approximately 45–55%. The same reduction was observed in the concentrations of the same pollutants, and the same applies to the impact of the external inflow. As a consequence, the population exposure to particulate matter pollution in the years considered will be 36/24/16 [μg/m3] for PM2.5 or 52/33/23 [μg/m3] for PM10, respectively.

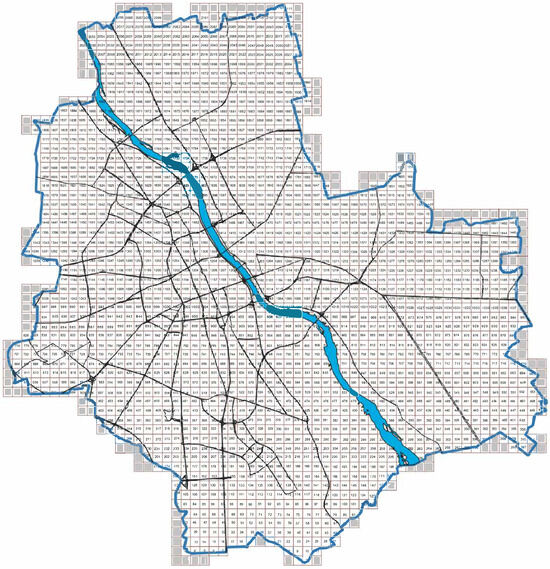

3.2. Computer Simulation Results for the Year 2023

Air pollution calculations for the actual emission data in the years 2012 and 2018 [10,11,20,21] were performed using the regional-scale CALPUFF model with the CALMET meteorological preprocessor [33]. The current version of the same model was consistently applied to analyze the dispersion of atmospheric pollution in Warsaw for 2023, which is published here for the first time. The Warsaw metropolitan area, which is approximately 520 km2, is discretized for numerical simulation using a homogeneous grid 0.5 km × 0.5 km that includes 2111 receptor elements (Figure 5) in which the annual mean concentrations for the main pollutants are computed. The total emission field comprises 91,600 area sources from the residential sector, 100,576 line transportation sources, and approximately 18,700 industrial point sources and other dispersed sources. The emission data, similarly to meteorology, are finally entered as a sequence of 1 h episodes (8785 time steps) that cover the considered year. The transboundary inflow of pollutants from the municipalities surrounding the city was also taken into account.

Figure 5.

Spatial discretization of the computational domain (receptor numbers indicated). The blue broad line going across the town represents the Vistula river.

In the model calculations, we used data (emission and meteorological) prepared by our partner companies, EKOMERIA S.A. (Gdańsk, Poland), for earlier years and KOBIZE (The National Centre for Emissions Management [34]) for the year 2023. Minor data gaps or their replacement with interpolated values happened in the data, but they do not significantly affect the average annual concentration.

The results of these calculations were used in Section 3 to compare pollutant values for 2023 with those of previous years, particularly concerning the level of the pollutant in question and the relative share of major emission categories (Figure 4).

The annual mean concentrations of basic pollutants for the entire year 2023 were then calculated with a one-hour time step. The concentrations for each receptor element (Figure 5) form a map of the given pollutant spatial distribution. Examples are presented below.

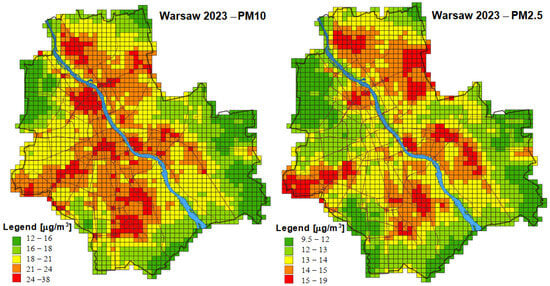

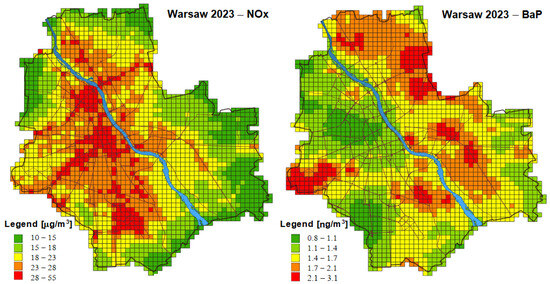

Figure 6 shows maps of the annual mean concentrations of the particulate matter pollution, PM10 (with a large contribution from transport and a slightly smaller contribution from the residential sector) and PM2.5 (dominant contribution from the residential sources). For both of these pollutants, external influx also significantly influences the results. Figure 7 shows analogous maps of the annual average NOx and BaP concentrations. In the former case, the influence of the transport sector dominates, while in the latter, the residential sector emissions dominate.

Figure 6.

The annual mean PM10 concentration (left) and PM2.5 (right) in Warsaw in 2023.

Figure 7.

The annual mean NOx concentration (left) and BaP (right) in Warsaw in 2023.

To assess the accuracy of the computer simulation results, the current records of GIOŚ air quality monitoring stations [32] can be utilized. In particular, this applies to the six stations listed earlier in Table 1, which were active in 2023, that provide access to, inter alia, records of PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations.

The GIOŚ air quality monitoring system, which has been operating in Poland since 2005, plays a crucial role not only in assessing the results of air quality modeling but also in evaluating the effectiveness of planned or implemented corrective policies in this area. However, the network of Airy sensors could complement the official GIOŚ monitoring network in future applications, in particular due to the increasing number of these sensors.

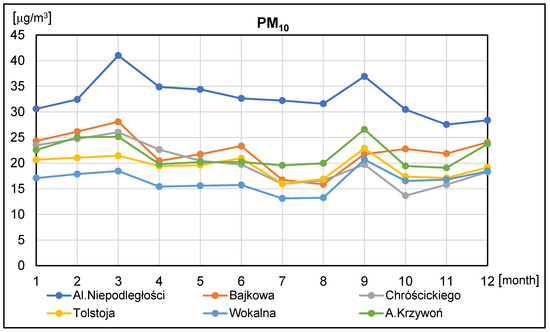

The analysis presented below uses records from selected monitoring stations of both systems. One Airly station had a data gap of about a week. This gap does not cause the waveform to look different from those for other sensors. So it was considered insignificant, particularly since the monthly averages from all sensors are used in the analysis. The resulting monthly averaged values of both monitoring systems are seen in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11.

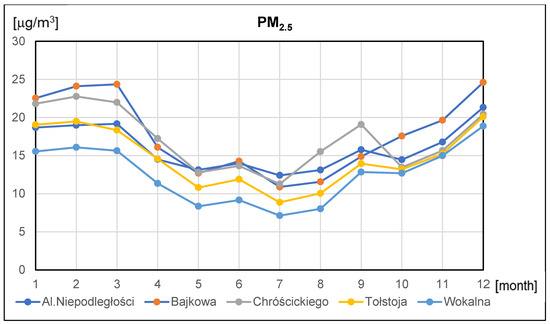

Figure 8.

Monthly average PM10 concentrations in 2023 as recorded by GIOŚ sensors.

Figure 9.

Monthly average PM2.5 concentrations in 2023 as recorded by GIOŚ sensors.

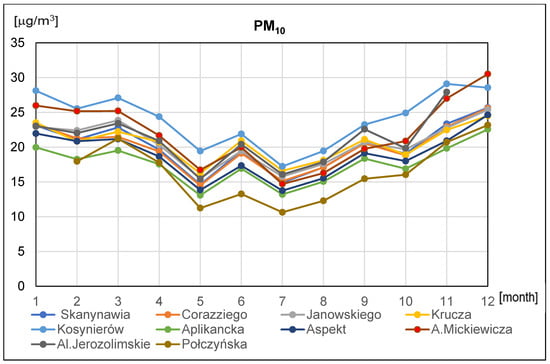

Figure 10.

Monthly average PM10 concentrations in 2023 as recorded by Airly sensors.

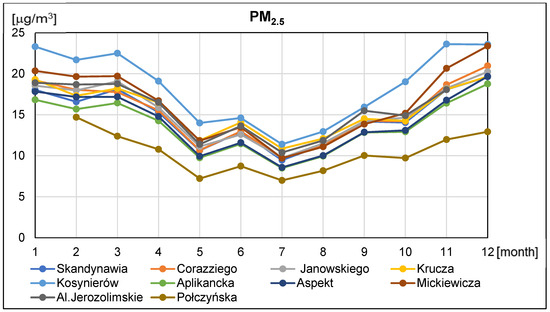

Figure 11.

Monthly average PM2.5 concentrations in 2023 as recorded by Airly sensors.

The analysis has two objectives: first, to assess the accuracy of the computer simulation for 2023 based on the current records of the two monitoring systems. Second, using records of the official GIOŚ system, which has been in operation for two decades, to assess the accuracy of the Airly monitoring system, developed recently. Since the sensors in the above systems have different locations, they cannot be compared directly. However, an indirect comparison can be made using modeling results at selected receptors (Figure 5) in the computational area.

In particular, 10 Airly sensors active in 2023 have been selected. They are located in the main districts of Warsaw and listed in Table 2. The hourly values of PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations at the indicated stations for the whole year 2023 were made available from the GIOŚ and Airly database. The names and coordinates of the active GIOŚ monitoring stations are presented in Table 1.

Table 3 presents a comparison of the annual mean PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in 2023, as recorded by the selected seven GIOŚ monitoring stations (six in the case of PM2.5), with the results of the CALPUFF model simulation values, averaged over the grid element that encloses the station and the receptor. The location of each receptor element (first column of the table) can be identified by the map of the computational area (Figure 5). The values in the table show that the average of the results from modeling is less than the average from the GIOŚ monitoring values about 1.4 μg/m3 (for both pollutants), that is, about 6% for PM10 and 9.5% for PM2.5.

Table 3.

GIOŚ monitoring PMs annual mean vs. CALPUFF modelling concentrations [μg/m3].

Table 4 compares in a similar way the modeling results with the corresponding concentration records from ten selected Airly monitoring stations (cf. Table 2). In this case, unlike before, Airly monitoring records show lower values than the corresponding CALPUFF modeling results, by about −2.7 μg/m3 for PM10 and about −1.3 μg/m3 for PM2.5. Looking at these results, it could be supposed that Airly monitoring records underestimate PM10 concentrations by above 20% compared to the GIOŚ system, while for PM2.5 concentrations, this underestimation is about 16%.

Table 4.

Airly monitoring PMs annual mean vs. CALPUFF modelling concentrations [μg/m3].

The significance of these differences was tested statistically. For this, the paired (dependent) samples t-test was applied for testing the equality of the average values of GIOŚ versus modeling results and Airly versus modeling results. The significance levels for the former were equal to for PM10 and for PM2.5. In the latter case, we obtained for PM10 and for PM2.5. Also, the equality of the GIOŚ and Airly average values was tested using the Welch’s t-test. In this case, the values were for PM10 and for PM2.5. Hence, the null hypothesis (equality of average values) is not rejected at the usually accepted critical level of significance, that is, .

The above results, as well as the tests performed for the annual mean concentrations, show that the modeling results are satisfactorily close to monitoring results from both GIOŚ and Airy sets of sensors, lying, in a way, between them. However, it should be noted that the available samples are short and therefore the results cannot be treated as conclusive. The concluding judgment has to be suspended until more evidence is gathered.

To throw more light on the comparison of the discussed results and explain the reasons for the apparent underestimation of Airly system records compared to official GIOŚ reports, a more detailed analysis is conducted in Section 3.3 by comparing the monthly means of the records in 2023.

3.3. Benchmark Analysis of Air Quality Monitoring Systems in Use

An advanced comparison can be obtained by examining the temporal distributions of the concentration records. Since the monitoring data from both the GIOŚ and Airly systems are available with an hourly step for the entire year 2023, it is possible to prepare graphs of the monthly average concentrations. Figure 8 presents graphs of monthly average PM10 concentrations recorded by 6 active GIOŚ monitoring stations. Similarly, Figure 9 shows analogous graphs for PM2.5 pollution (in this case, only records from 5 stations are available).

One can note the particularly high PM10 values recorded by the Al. Niepodległości sensors (the main “traffic” station in Warsaw, with a high share of the re-suspended fraction), while in the case of PM2.5, the records from this station coincide with the average of the other four (urban background) stations. Also, different yearly temporal profiles of the PM10 and PM2.5 charts can be observed. Specifically, the PM2.5 pollution profile reflects the variation in heating intensity between the seasons.

Figure 10 and Figure 11 present the respective monthly average PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations recorded by the Airly monitoring system. In this case, the records of 10 monitoring sensors (cf. Table 2) are taken into account. The visible discrepancies between the readings of both systems concern, in particular, the PM10 concentration records (Figure 8 and Figure 10).

4. Discussion

Some important components of the discussed pollutants need to be considered in analyzing the graphs presented. Particularly, in urban areas, a key component of PM10, in addition to the direct, primary emission of the transport sector, is the so-called re-suspended pollution (secondary emission). This includes, as a rule, coarser particles that come from abrasion of the tires, brake wear, etc., but also particles lying on the roadway that come from other sources. Re-suspended pollution represents a significant fraction of the traffic-originating PM10 particles, often accounting for 3 to 4 times the primary emissions [11,20,21]. The secondary emission also occurs for PM2.5, but on a much smaller scale, being comparable to the primary fraction. Moreover, the secondary emission process varies significantly throughout the year. It is usually low during the November-March period, accounting for approximately 30% of the total PM10 concentration (mainly due to wet roads), increasing to over 60% in the summer months. This effect is also accounted for in air pollution transport models, including CALPUFF modeling [21].

Another key process to be considered in analysis is the emission of fine particulates (PM2.5), for which the residential sector is predominantly responsible (combustion of solid fuels, still mainly coal). During the year, this process also varies; however, the highest emissions (approximately 65% of the total PM10 pollution) occur during the autumn-winter heating season, while they are at a minimum (31% share) in the summer (cf. Figure 9).

The PM10 concentration values presented in Figure 8, recorded by the six GIOŚ sensors, show slight fluctuations around the mean value during the year. The traffic sensors are located along important traffic routes (including the main traffic station, Al. Niepodległości), while the urban background ones are at a certain distance from such a road. In each case, the sensors are installed at ground level, allowing them to fully record the secondary emission process. At the same time, any PM10 concentration record includes the PM2.5 fraction (45–75% in this case). Hence, the influence of both previously mentioned processes compensates for each other (such that no significant variation in concentration during the year is visible). The local maxima in September, and less visible in March (also recorded by some stations), are due to extremely dry months in 2023, particularly in September, and somewhat higher traffic in these months. On the other hand, during the summer months, the same monitoring stations record a clear global minimum of PM2.5 concentration, reproducing the emission profile of fine particulates coming from residential sources.

The situation is quite different for the Airly monitoring system, where, as seen in Figure 10 and Figure 11, both the PM10 and PM2.5 concentration recorded graphs depict a clear global minimum in the summer months. The shape of the annual PM10 run (cf. Figure 10) is a direct reflection of the key feature associated with this network. First, in the case of the Airly sensors, there is a higher percentage of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in the total mass of particulate matter PM10, cf. Table 3 and Table 4 or Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. It seems that the differences observed in the measurements of the two systems are due to the different places where the sensors are installed. In the GIOŚ system, sensors are basically placed just above the roadway level and even close to the roadway, as in the case of the traffic station. At the same time, the Airly sensors are subject to quite specific rules. Being commercial, the company sells air quality sensors to individual customers, who become its owners and decide where to install them. In practice, this means a rather random placement of the sensors, often at an elevated level.

It is well known [35,36] that the concentration of pollutants emitted by such a source decreases with altitude, by 15–20% at a height of 10 m (approximately the 3rd floor) and about 35–40% at a height of 30 m (around the 10th floor). At the same time, it is clear that this decrease in concentration mainly affects the coarser dust fractions, due to their mass. This is especially true for re-suspended traffic-related dust particles. As a result, a higher proportion of the PM2.5 fraction appears in the PM10 concentration measured. This explains the main difference observed in the temporal records of PM10 concentrations between the systems. Elevated Airly sensors do not detect (or detect only in a small percentage of) the coarse fractions of re-suspended traffic particles. Consequently, the annual PM10 temporal graph for this system shows a significant minimum in the summer months (see Figure 9), which results from lower PM2.5 levels during this season, unlike the steady PM10 levels recorded by GIOŚ (see Figure 8), which include more coarse fractions. Therefore, the temporal pattern of this pollutant in the Airly monitoring data resembles that of PM2.5 (see Figure 10 and Figure 11), since there is no mutual compensation between the effects of the secondary traffic pollution and residential pollution during summer months, as seen in GIOŚ records (compare Figure 8 and Figure 10). Thus, the Airly sensor system poorly captures traffic-originated air pollution but emphasizes the impact of elevated emission sources. This is also evidenced in the records from all Airly sensors, which clearly show local maxima of PM10 (Figure 10) and PM2.5 (Figure 11) concentrations in June, when traffic was lower.

This fact can be substantiated by an interesting Saharan dust episode over Polish territory in June 2023. According to an official communication from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) [37], the highest concentrations during this episode occurred in Poland on 22 June 2023. It should be noted that the Saharan dust cloud consists mainly of mineral particles lifted to a considerable height (around 3000 m or even more) by very frequent sandstorms in this region, accompanied by strong thermal updrafts. The cloud primarily comprises PM10 particles, with minor and variable contributions of PM2.5 particles, as illustrated by episodes in recent years in Poland [38]. The wind can transport such a cloud over considerable distances [39,40], subject to gradual cooling and particle descent. However, the vertical concentration profile in the cloud depends on many factors, usually typifying the episode. Usually, the concentration of the dust at higher altitudes exceeds its ground level values [37,41]. In particular, in the case considered, the elevated Airly sensors recorded a significantly greater impact of the descending cloud of pollution (Figure 10 and Figure 11), particularly evident in the case of PM10 particles, than the GIOŚ sensors located at ground level (Figure 8 and Figure 9). This episode is also slightly marked in the GIOŚ system by PM2.5 sensors (Figure 9). Similar results regarding PM10 concentrations can be seen in [42], which highlights the impact of an episode of Saharan dust on 17 March 2022. The Saharan episode well illustrates the differences in the results of the two monitoring systems discussed. They measure (at least on average) differently, and this may be caused by different levels of their installation above the ground. The importance of this impact should be remembered to properly interpret air quality monitoring records. Omitting this factor may sometimes lead to a completely false interpretation of the air quality monitoring records, as in [42].

The differences can be additionally seen in a significant increase in PM10 concentrations in September, which is visibly marked by the GIOŚ system (Figure 8), but is only marginally recorded by some Airly sensors (Figure 10). In this case, unlike the Sahara episode, the main PM10 sources are at ground level, which is less noticeable at higher altitudes.

The above examples illustrate the characteristics of Airly as an urban air quality monitoring system. It is sensitive to even marginal and unique episodes connected with fine fractions and, at the same time, weakly reacts to the changing contribution of the urban transportation system, which has an important impact on the city’s ultimate ambient air quality. These differences are visible in comparison of the year means, but the differences in the means are too small to be detected by the statistical test.

The discrepancies in PM10 measurements by GIOŚ stations and Airy sensors in Warsaw were also noticed in [42], mainly coincident with our observations. In particular, they point to increased discrepancies in cases of high PM10 concentrations. Our observations give a possible explanation of the facts noticed there.

5. Conclusions

At the beginning of the last decade, Warsaw was one of the most polluted cities in Europe. The primary local sources of this pollution were the residential sector and urban transport, though a significant part of the pollution also came from external sources. A noticeable improvement has occurred due to the efforts undertaken during the last decade by both the central and city authorities, aimed at significantly improving the air quality, that is, moving away from coal to renewable sources, modernizing the transport sector, creating a Clean Transportation Zone (CTZ), and implementing pro-environment programs in the residential sector. The monitoring records show a clear reduction in concentrations of key pollutants in recent years, and compliance with EU limits in most cases.

The yearly averages obtained from these monitoring records and the CALPUFF model simulations for years 2012, 2018, and 2023 agree well with each other, which is additionally confirmed in the latest case by using the statistical paired test. Also, for the records obtained from a network of IoT sensors established recently in Warsaw, the statistical tests suggest a similarity between the yearly averages of the Airly measurements and simulated results. Hence, based on the t-test carried out, it can be concluded that the mean yearly results obtained by both monitoring systems and the computer model are statistically comparable.

Since the sensors of the GIOŚ and Airly systems have different locations, they could not be compared directly. However, we compare them indirectly using computer simulation results obtained for the grid cells corresponding to the sensor location. The results showed that the CAPUFF modelling results are satisfactorily close to monitoring results from both GIOŚ and Airy sensors, but also that they lie, in a way, between them. This suggests that Airly’s record may be an underestimate of the official, GIOŚ true measure.

Finally, a more detailed comparison of the two monitoring systems is presented, including an explanation for the apparent underestimation when using the Airly system records. It is based on an analysis of the monthly averages of the GIOŚ and Airly records. To this end, the full annual time series of PM10 and PM2.5 concentration records in 2023 have been compared. It was found that the main reason for the underestimation of the concentrations recorded by the Airly system may be the sensors’ elevated location above ground level. On the one hand, this results in a serious underestimation of the impact of road transport (especially secondary, re-suspended pollution), and on the other hand, in a misinterpretation of the episodes related to the inflow of Saharan dust.

We believe that the comparison of particulate matter concentrations coming from the three different assessment systems is a novel one. We also hope that the results of this analysis, although preliminary, may be important for future applications of both systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H. and Z.N.; methodology, P.H.; software, A.K.; validation, P.H. and Z.N.; formal analysis, Z.N.; investigation, P.H.; data curation, P.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.N. and J.H.-P.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, Z.N.; project administration, Z.N.; funding acquisition, Z.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study were generated and analyzed. The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/pjp/archives (accessed on 10 March 2025) or https://airly.org/map/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the insightful comments of the Reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Juda-Rezler, K.; Zajusz-Zubek, E.; Reizer, M.; Maciejewska, K.; Kurek, E.; Bulska, E.; Klejnowski, K. Bioavailability of elements in atmospheric PM2.5 during winter episodes at Central Eastern European urban background site. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 245, 117993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunis, P.; Degraeuwe, B.; Pisoni, E.; Trombetti, M.; Peduzzi, E.; Belis, C.A.; Wilson, J.; Clappier, A.; Viganti, E. PM2.5 source allocation in European cities: A SHERPA modelling study. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 187, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IQAir World. Air Quality in the World. The Most Polluted Major City Ranking 2023. Available online: https://www.iqair.com/world-air-quality-ranking (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Sattari, A.; Hooyberghs, H.; Strużewska, J.; Gawuc, L.; Blyth, L.; Vranckx, S. Evaluating traffic-related air pollution in urban areas: A case study of Warsaw using the ATMO-Street model chain. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 360, 121376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NILU 2022. Premature Deaths due to Air Pollution Continue to Fall in the EU 2022. Available online: https://www.nilu.com/2022/11/premature-deaths-due-to-air-pollution-continue-to-fall-in-the-eu/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- EEA 2023. Urban Air Quality. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/air/urban-air-quality (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- EEA 2025. Exceedance of Air Quality Standard in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/exceedance-of-air-quality-standards (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- WHO 2024. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Degraeuwe, B.; Pisoni Christidis, P.; Christodoulou, A.; Thunis, P. SHERPA-city: A web application to assess the impact of traffic measures on NO2 pollution in cities. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 135, 104904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holnicki, P.; Kałuszko, A.; Trapp, W. An urban scale application and validation of the CALPUFF model. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2016, 7, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holnicki, P.; Tainio, M.; Kałuszko, A.; Nahorski, Z. Burden of mortality and disease attributable to multiple air pollutants in Warsaw, Poland. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Pyzalska, A. Perspectives of development of low emission zones in Poland: A short review. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 898391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzomska, A.; Strużewska, J. A six-year measurement-based analysis of traffic-related particulate matter pollution in urban areas: The case of Warsaw, Poland (2016–2021). Arch. Environ. Prot. 2024, 50, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska-Witowska, I.; Długosz, P.; Gayer, A. Annual Air Quality Assessment in the Mazovian Voivodeship; Province Report for 2023; The Chief Inspectorate for Environmental Protection: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Sompolska-Rzechuła, A.; Bąk, I.; Becker, A.; Marjak, H.; Perzyńska, J. The use of renewable energy sources and environmental degradation in EU Countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coal Use 2024. Available online: https://wysokienapiecie.pl/96011-udzial-wegla-i-oze-w-polsce-2023/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Zyśk, J.; Wyrwa, A.; Suwała, W.; Pluta, M.; Okulski, T.; Raczyński, M. The impact of decarbonization scenarios on air quality and human health in Poland—Analysis of scenarios up to 2050. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RES 2024. Available online: https://www.gramwzielone.pl/trendy/20296886/oze-w-gore-tak-wygladal-miks-energetyczny-polski-w-2024 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Pisoni, E.; Thunis, P.; de Meji, A.; Bessagnet, B. Assessing the impact of local policies on PM2.5 concentration levels: Application to 10 European Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holnicki, P.; Kałuszko, A.; Nahorski, Z. Analysis of emission abatement scenario to improve urban air quality. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2021, 2, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Holnicki, P.; Nahorski, Z.; Kałuszko, A. Impact of vehicle fleet modernization on the traffic-originated air pollution in an urban area—Case study. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Air Program. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/climate/clean-air-20-programme-launched (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Kiciński, J. Green energy transformation in Poland. Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Tech. Sci. 2021, 69, e136213. [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Smog 2023. New Anti-Smog Regulations in Warsaw. Available online: https://ceo.com.pl/en/new-anti-smog-regulations-in-warsaw-coming-this-sunday-96113/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Rybak, A.; Rybak, A.; Joostberens, J. The impact of removing coal from Poland’s energy mix on selected aspects of the country’s energy security. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squalli, J. Greening the roads: Assessing the role of electric and hybrid vehicles in curbing CO2 emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Cities 2022. The Development Trends of Low- and Zero-Emission Zones in Europe. Available online: https://cleancitiescampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/The-development-trends-of-low-emission-and-zero-emission-zones-in-Europe-1.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- CTZ 2024. Design of Clean Transportation Zone in Warsaw. Available online: https://urban-mobility-observatory.transport.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/warsaw-install-clean-transport-zone-2024-2023-02-13_en (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Autokatalog 2023. Available online: https://autokatalog.pl/blog/2023/auta-hybrydowe-w-polsce-ranking-wrzesien-2023 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Airly Map 2020. Available online: https://airly.org/map/en/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- GIOŚ AQ Forecasts. Available online: https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/pjp/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- GIOŚ Archives. Available online: https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/pjp/archives (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Exponent. CALPUFF Version 7-Users Guide Addendum; Doc. no. Z170308064614-0072; Exponent Inc.: Maynard, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- KOBIZE 2023. The National Centre for Emissions Management. Available online: https://www.kobize.pl/pl/fileCategory/id/37/2023 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Blog-Spalinowy 2018. Available online: http://blogspalinowy.pl/jak-wysoko-unosza-sie-spaliny-samochodowe/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Jaworski, A.; Kuszewski, H.; Balawender, K.; Babiarz, B. Atmospheric concentration of particulate air pollutants in the context of projected future emissions from motor vehicles. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahara Dust 2023. Available online: https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/pjp/content/show/1004524 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Sahara Dust 2024. Available online: https://mappingair.meteo.uni.wroc.pl/2024/04/pyl-saharyjski-nad-polska-wielkanoc-2024/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Loskot, J.; Jezbera, D.; Nalezinkova, M.; Holubova-Smejkalova, A.; Fernandes, D.; Komarek, J. Impact of Saharan dust on particulate matter characteristics in an urban and a natural locality in Central Europe. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Ghobadi, T.; Shao, Y.; Fallah, B.; Rostami, M.; Mao, R. Investigation of the role of southwestern Asia dust events on urban air pollution: A case study of Ahvaz, a highly polluted city. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A.; Ferenczi, Z. Saharan dust contributions to PM10 levels in Hungary. Air 2024, 2, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattari, A.; Hooyberghs, H.; Janssen, S.; Norowski, A.; Blyth, L.; Augustowski, I. Enhancing ATMO-Street model through emission source analysis using dense sensor network: Accuracy traffic-related air pollution in urban areas: A Warsaw case study. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).