Abstract

Using station observations, the JRA-55 reanalysis dataset, and the CESM2 model, this study investigates the impacts of the stratospheric polar vortex (SPV) on winter near-surface wind speed (NSWS) over China across interannual and interdecadal timescales. On the interannual timescale, a strong SPV leads to a downward-extension signal that generates negative geopotential height anomalies over the Arctic, skewed toward the Atlantic sector. The associated surface response resembles the positive phase of the Arctic Oscillation (AO), resulting in reduced NSWS over northern China. In contrast, a weak SPV produces opposite effects. On the decadal timescale, a weakened SPV induces positive height anomalies over the Arctic that shift toward Northeast Eurasia. The surface response over the polar region stimulates a wave train, which drives a positive height anomaly over the North Pacific. The pressure gradient between East Asia and the North Pacific suppresses NSWS over eastern China. The response of China’s NSWS to interannual SPV variability is more pronounced than its response to interdecadal changes. CESM2 model simulations confirm these contrasting responses and the associated mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Near-surface (10 m) wind speed (NSWS) has attracted considerable attention due to its influence on weather and climate, as well as its critical role in the renewable energy sector. As a key meteorological variable, NSWS could influence energy and moisture exchanges between the surface and the atmospheric boundary layer [1,2,3,4], extreme weather events [5], and plays an important role in visibility and air quality [6,7,8,9]. In recent decades, the rapid increase in greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions, coupled with global warming, has raised public awareness of the need for energy conservation and emissions reduction [10,11,12,13]. Wind energy, which offers both energy generation and environmental benefits, has become one of the fastest-growing renewable energy sources worldwide [14,15]. NSWS is a fundamental factor in wind energy development and is widely used in applications such as wind farm site selection and wind power forecasting [16].

Numerous studies have examined the multiscale variability of NSWS over China [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. These variations are typically attributed to both internal climate system variability and anthropogenic influences [26,27]. The former primarily involves large-scale air–sea circulation changes and teleconnection patterns, including the Asian monsoon [28,29,30], the Arctic Oscillation (AO)/Northern Annular Mode [22,29,31], the Siberian High [23], as well as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) [25,32,33]. The latter emphasizes the effects of human activities, such as greenhouse gas emissions and global warming [34], along with changes in land use and cover change (LUCC) that affect surface roughness [18,19,20,21,26,35]. To date, most of these studies have focused on surface forcing and tropospheric internal dynamics as key drivers of NSWS changes over China. However, relatively little attention has been paid to the influence of the middle and upper atmosphere.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, increasing attention has been paid to the role of stratospheric dynamics in weather and climate variability, particularly the influence of the stratospheric polar vortex (SPV) [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Variability in the SPV often precedes changes in surface weather, making it a potential predictor of surface weather regimes [47,49,50,51]. Downward-extension of SPV signals can modulate the Arctic Oscillation (AO) pattern [49], influence atmospheric blocking activity [52,53], alter the frequency of cold air outbreaks [47,48,54,55,56], and affect precipitation over East Asia [57]. These findings suggest the possibility that the SPV may also influence NSWS over China.

The SPV exhibits distinct variability on both interannual and interdecadal timescales [47,58]. However, the extent to which these variations influence NSWS over China remains unclear. This study aims to investigate the role of the SPV in modulating winter NSWS over China, explore the underlying mechanisms, and compare the impacts of interannual and interdecadal SPV variability on NSWS. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 describes the data and methodology. Section 3 examines the interannual and interdecadal variability of NSWS. Section 4 and Section 5 analyze the interannual and interdecadal variability of the SPV and their respective influences on NSWS. Section 6 provides the conclusions and discussion.

2. Data and Method

In this study, the 10 m wind speed data are obtained from the National Meteorological Information Center (NMIC) of the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) for the period 1958–2021. These data are measured using cup anemometers in accordance with the Observing System and Technical Regulations on Weather Observations issued by the CMA. A total of 331 national standard meteorological stations that have passed homogeneity testing are used. These stations, along with the quality-controlled data, are provided by the NMIC. The homogeneity testing method and station selection are consistent with those used in R. Zhang et al. (2019) [23]. Reanalysis data are obtained from the Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA-55; 1.25° latitude × 1.25° longitude resolution) produced by the Japan Meteorological Agency [59]. The variables used include 10 m zonal and meridional wind, geopotential height, zonal wind (u), meridional wind (v), and temperature (T).

Anomalies during boreal winter (December, January, and February; DJF) are calculated as deviations from the corresponding seasonal climatological means. Statistical significance is assessed using a two-sided Student’s t-test. The effective degrees of freedom in correlation analyses are estimated based on lag-one autocorrelation following the method of Bretherton et al. (1999) [60]. In total, 10 m wind speed (V) of JRA-55 (4 times per day) is calculated using zonal wind (u) and meridional wind (v), . The difference between observations and reanalysis datasets (OMR) is often used to separate the impacts of LUCC and large-scale pressure change, because reanalysis datasets generally do not consider local LUCC [18,23]. Although the 10 m u and v winds in JRA-55 include some land-based wind observations and LUCC-related signals, the isobaric analysis assimilation primarily incorporates surface pressure. Therefore, to isolate the wind component driven by large-scale pressure changes, we interpolate isobaric winds to the 10 m level.

The intensity of the stratospheric polar vortex (SPVI) is defined as the zonal-mean zonal wind at 60° N and 10 hPa. In this study, we investigate the impacts of both interannual and interdecadal variability of the SPV on NSWS over China. An 11-year high-pass and low-pass Fourier filter is applied to extract interannual and interdecadal components, respectively. Strong (weak) SPV events are defined when the SPVI exceeds +0.5σ (falls below −0.5σ) [61,62]. The variability in SPV strength is analyzed separately on interannual and interdecadal timescales.

We use the Community Atmosphere Model version 6 (CAM6) of the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2) to conduct stratospheric nudging experiments. A control experiment (R0), without nudging, is first run for 25 years to provide the atmospheric initial conditions. All external forcings in R0 are prescribed as climatological values averaged over the period 1995–2005 and follow a fixed, repeating annual cycle. The first five years of R0 are treated as spin-up, and the remaining 20 years are used to generate initial conditions for the nudging experiments (R1). In the R1 experiments, the atmospheric variables (zonal wind u, meridional wind v, and temperature T) above the 143 hPa model level are nudged toward the JRA-55 reanalysis data. R1 consists of 20 ensemble members, initialized from different years of the R0 simulation. Each ensemble member starts on 1 October and runs for 64 years, covering the period from 1958 to 2021. The evolution of the SPV in the R1 simulations closely resembles that in the JRA-55 dataset, allowing the R1 experiments to be used to isolate and assess the influence of the SPV on NSWS. Detailed parameter settings can be referred to in Zhang and Zhou’s study [57].

3. Winter NSWS over China

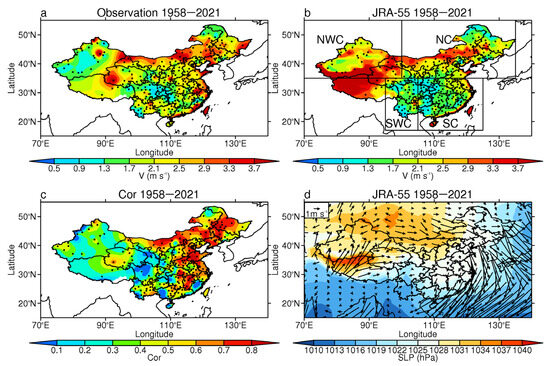

Figure 1 shows the horizonal distribution of the winter-mean NSWS in China. Consistent with previous studies [17,23,35], large NSWS values are primarily observed in the coastal and northern regions of China (Figure 1a), while southern China generally experiences lower wind speeds, typically below 2.5 m/s—significantly weaker than those in the northern region. The Tibet Plateau is not within the scope of our discussion, due to the lack of observations. The JRA-55 reanalysis dataset can capture the spatial characteristics of observational NSWS (Figure 1b); however, there are significant differences in the simulations of time series (Figure 1c). High correlation between JRA-55 and station observational time series is observed in the eastern and northeastern region of China, while low correlation occurs in Fujian province and the western region of China. These discrepancies are mainly associated with the assimilation of station observations and the simulation of surface roughness in JRA-55 [23,59,63,64]. Wind directions exhibit substantial regional differences due to the influence of surface air pressure and frictional effects (Figure 1d). Northwesterly winds dominate in northern China (NC), while northeasterly winds prevail in southern China (SC). In southwestern China (SWC), weak southerly winds are observed, whereas northeasterly winds are present in northwestern China (NWC). For further analysis, we categorize NSWS into four regional groups based on wind direction, as indicated by the boxes in Figure 1c.

Figure 1.

NSWS over China. (a) Spatial distribution of the multi-year averaged monthly NSWS from observations. (b) As in (a), but derived from the JRA-55 reanalysis dataset. (c) Correlation coefficients between winter-mean observed NSWS and that from JRA-55. (d) As in (a), but for sea level pressure (SLP, color) and 10 m wind (vectors). Black dots in (a,b) represent stations, and those in c are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t test.

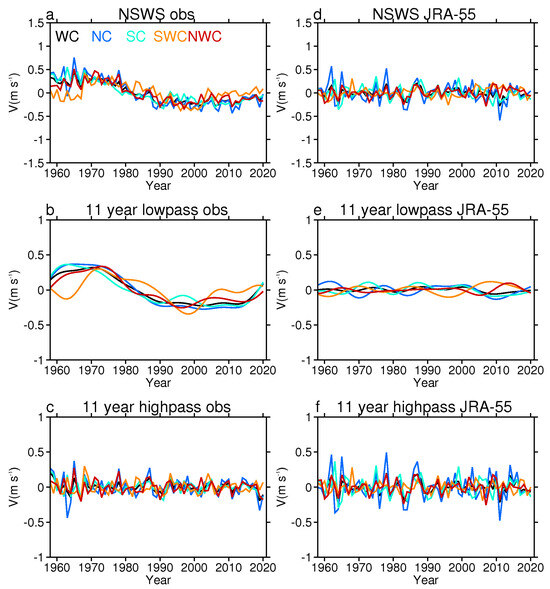

Figure 2 illustrates the temporal evolution of NSWS across China, revealing significant interannual and interdecadal variations (Figure 2a). On the interdecadal timescale, NSWS showed a decline from the 1970s to the 2000s, followed by a slight increase thereafter (Figure 2b). This trend is consistent across all four regions, which may be influenced by common factors such as the AMO [25] and LUCC [18,19,21,35]. The interannual variations exhibit more regional discrepancies, though their amplitude is generally weaker than that of the interdecadal changes (Figure 2c). The JRA-55 reanalysis dataset effectively captures the interannual and interdecadal changes in NSWS in most regions, except for F region (Figure 2d–f). The correlation coefficients between JRA-55 and observation are below 0.5 over SWC, but can reach 0.6 or even 0.9 in other regions (Table 1). Therefore, the use of JRA-55 for analyzing NSWS in most areas of China is justified.

Figure 2.

Interannual and interdecadal variation in NSWS over China. (a) Winter-mean NSWS over China. (b) As in a, but for 11-year low-pass filtering results. (c) As in (a), but for 11-year high-pass filtering results. (d–f) As in a, but from JRA-55 reanalysis dataset.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between JRA-55 and station observation. (* indicates the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t test).

4. Linkage Between SPV and NSWS on Interannual Timescale

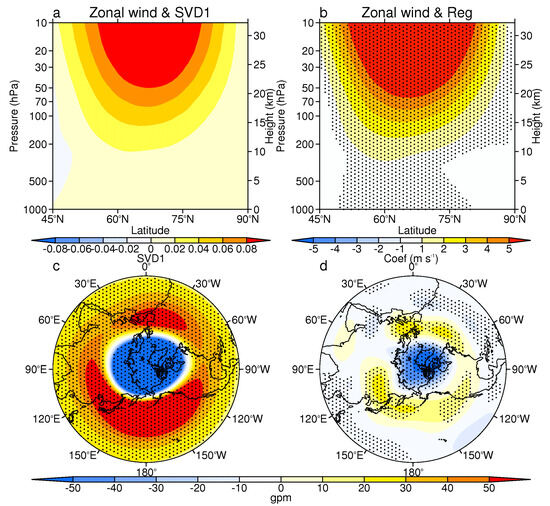

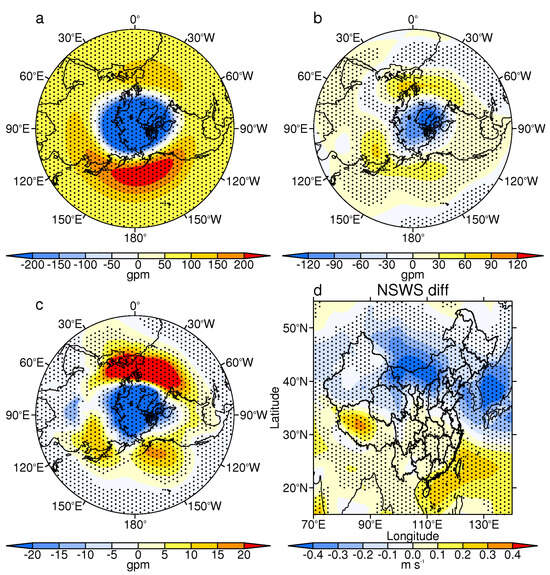

The aim of this study is to investigate the influence of the SPV on NSWS over China. To isolate interannual variability, an 11-year high-pass filter is applied to the anomalies. The relationship between zonal-mean zonal wind anomalies (45–90° N, 1000–1 hPa) and NSWS is then examined using singular value decomposition (SVD) analysis. The leading SVD mode (SVD1) explains over 83% of the total covariance between zonal wind and NSWS, while the second mode (SVD2) accounts for only 6%, indicating that SVD1 captures the dominant feature of the SPV–NSWS connection. The SVD1 pattern for zonal wind reveals a pronounced westerly anomaly centered in the stratosphere (Figure 3a), accompanied by a north–south dipole structure centered around 45° N (Figure 3b). This corresponds to a typical strong SPV pattern, characterized by negative geopotential height anomalies over the polar stratosphere and positive anomalies over the mid-latitude stratosphere (Figure 3c,d).

Figure 3.

Linkage between SPV and NSWS on interannual timescale. (a) SVD1 for the zonal wind anomalies in boreal winter. (b) Zonal wind anomalies regressed onto the standardized principal component time series of SVD1 (PC1). (c) 10 hPa geopotential height anomalies regressed onto the standardized PC1. (d) As in c, but for 200 hPa geopotential height anomalies. An 11-year high-pass filter was applied to all anomalies prior to the SVD analysis. The SVD was performed based on the covariance of observational NSWS over China and the zonal wind anomalies (1000–1 hPa, 45° N-90° N). Black dots in (b–d) are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

As reported in previous studies [36,47,48], SPV signals can precede changes in the troposphere and extend downward to the surface (Figure 4a). This downward propagation of a strong SPV leads to a positive phase of the Arctic Oscillation (AO) at the surface, characterized by negative geopotential height anomalies over the Arctic and positive anomalies over the Euro-Atlantic region and East Asia (Figure 4b). The SPV-induced pressure gradient over East Asia weakens the westerly winds over NC and strengthens the northerly winds over SC (Figure 4c). As a result, NSWS decreases in NC and increases in SC due to large-scale pressure changes (Figure 4d). The response of observed NSWS to the SPV is generally consistent with that related to large-scale pressure changes, though the magnitudes are smaller in the observations (Figure 4e). This discrepancy may be attributed to the effects of LUCC. Compared to station-based observations, isobaric wind field from the JRA-55 dataset does not account for LUCC’s impacts. Overall, LUCC acts to weaken the direct response of NSWS to SPV variations.

Figure 4.

Composite differences between strong and weak SPV events. (a) Composite difference in JRA-55 zonal wind anomalies averaged along 65° N. (b) Composite difference in 1000 hPa geopotential height anomalies from JRA-55. (c) As in (b), but showing 1000 hPa geopotential height and wind anomalies over China. (d) As in (c), but for NSWS anomalies attributed to SPV-induced circulation changes (JRA-55 isobaric wind interpolated to station locations). (e) As in (d), but for observational NSWS anomalies. (f) The NSWS change related to LUCC (e) minus (d). An 11-year high-pass filtering is applied to anomalies. Black dots in (a–e) are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

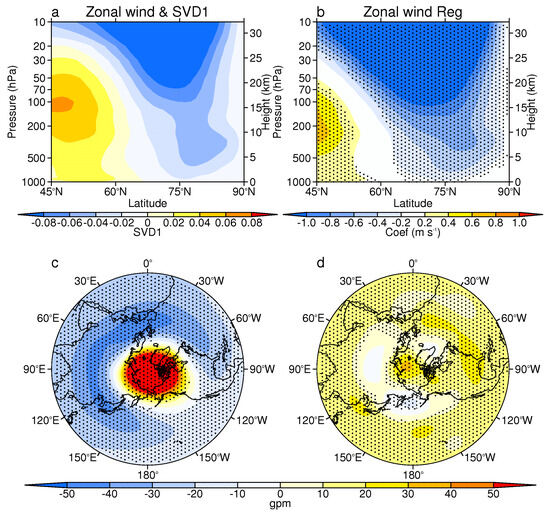

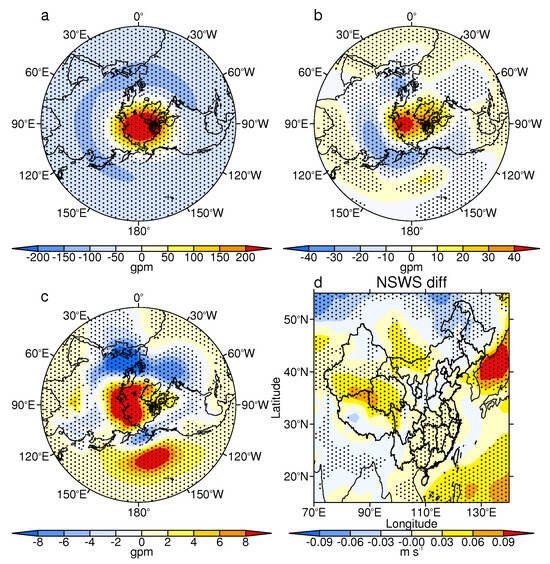

While statistical analysis cannot completely rule out the possibility of randomness, we conduct stratospheric nudging experiments to validate the statistical results. In the nudging experiment, the climatology of external forcing is used to eliminate the interference from factors such as sea surface temperature and land surface process. Assembling results helps us avoid the influence from initial disturbance. Figure 5 presents the anomalies in geopotential height and NSWS from the CESM2 model. The nudging experiments successfully capture the observational SPV pattern at both 10 hPa and 200 hPa (Figure 5a,b). The pattern can extend downward to the surface, and lead to a positive AO pattern at the surface (Figure 5c). Influenced by the circulation change, the model’s NSWS closely matches the results from JRA-55 and station observations (Figure 5d), reinforcing the mechanism that the influence of the SPV on wind speed is a genuine physical process.

Figure 5.

Composite differences between strong and weak SPV events in CESM2. (a) 10 hPa geopotential height anomalies; (b) 200 hPa geopotential height anomalies; (c) 1000 hPa geopotential height anomalies; (d) NSWS anomalies. The composite results are averaged by 20 sets of nudging experiments. An 11-year high-pass filtering is used in anomalies and the SPV events are the same as those in Figure 4. Black dots in (a–d) are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

5. Linkage Between SPV and NSWS on Interdecadal Timescale

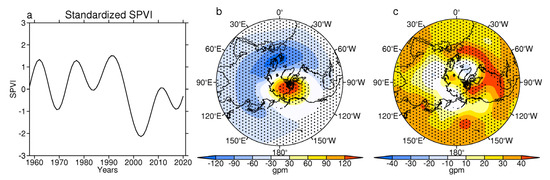

Interdecadal variations are another key characteristic of the SPV. The SPV strengthened during the 1970s–1990s and then weakened thereafter [47,65]. These changes may result in a series of effects on NSWS over China. We use an 11-year low-pass filter to capture the interdecadal timescale [66]. Figure 6 presents the SVD analysis of zonal wind and NSWS. Similarly to the interannual timescale, the contribution of the first SVD mode (SVD1) is dominant, explaining 73% of the covariance, far surpassing that of the other modes. Therefore, we focus our analysis on SVD1. A westerly anomaly is observed in the mid-latitude troposphere, while an easterly anomaly occurs in the stratosphere and polar troposphere (Figure 6a,b). This indicates a weak SPV pattern, characterized by positive height anomalies in the polar stratosphere and negative anomalies in the mid-latitudes (Figure 6c). The positive height anomalies extend downward into the lower stratosphere (Figure 6d). Notably, the center of polar height anomalies shifts toward the northern part of Eurasia on the interdecadal timescale, in contrast to the shift toward the Atlantic observed on the interannual timescale. Figure 7 presents the time series of the SPVI on the interdecadal timescale. It can be seen that the changes in SPV strength are primarily associated with the weakening of the SPV after the 1990s (Figure 7a). Furthermore, the composite differences in geopotential height anomalies (1990–2021 minus 1958–1989) exhibit a spatial pattern similar to that obtained from the SVD analysis (compare Figure 7b,c with Figure 6c,d).

Figure 6.

Linkage between SPV and NSWS on interdecadal timescale. (a) SVD1 for the zonal wind anomalies in boreal winter. (b) Zonal wind anomalies regressed onto the standardized principal component time series of SVD1 (PC1). (c) 10 hPa geopotential height anomalies regressed onto the standardized PC1. (d) As in c, but for 200 hPa geopotential height anomalies. An 11-year low-pass filter was applied to all anomalies prior to the SVD analysis. The SVD was performed based on the covariance of observational NSWS over China and the zonal wind anomalies (1000–1 hPa, 45° N–90° N). Black dots in (b–d) are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

Figure 7.

Interdecadal changes in SPVI. (a) Time series of standardized SPVI. (b) Composite differences of 10 hPa geopotential height anomalies (1990–2021 minus 1958–1989). (c) As in (b), but for 200 hPa geopotential height anomalies. An 11-year low-pass filtering is used in anomalies. Black dots in (b,c) are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

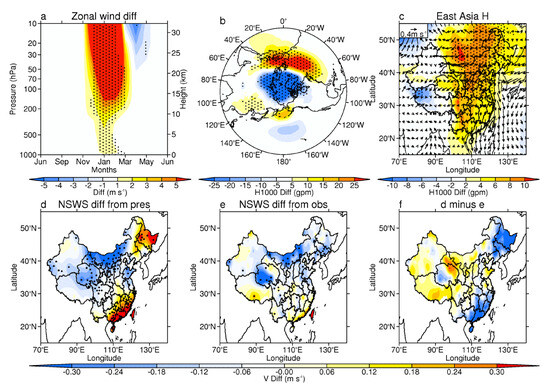

The SPV changes can also propagate downward to the surface, though with a weaker signal (Figure 8a). Positive height anomalies over the Arctic are primarily observed near the northern part of Eurasia, rather than in the North Atlantic sector (Figure 8b). This alteration drives shifts in the tropospheric circulation. Positive height anomalies in the polar region trigger an anomalous wave train from the Arctic to the North Pacific, leading to negative height anomalies near the Bering Strait and positive anomalies over the North Pacific. These positive anomalies over the North Pacific modify the pressure gradient over East Asia, suppressing the northerly winds (Figure 8c). As a result, NSWS decreases over eastern China due to large-scale pressure changes (Figure 8d). The response of observed NSWS closely resembles that in the JRA-55 dataset (Figure 8e), with some discrepancies attributed to the effects of LUCC (Figure 8f).

Figure 8.

Composite differences between weak and strong SPV events on interdecadal scales. (a) Composite difference in JRA-55 zonal wind anomalies averaged along 65° N. (b) Composite difference in 1000 hPa geopotential height anomalies from JRA-55. (c) As in (b), but showing 1000 hPa geopotential height and wind anomalies over China. (d) As in c, but for NSWS anomalies attributed to SPV-induced circulation changes (JRA-55 isobaric wind interpolated to station locations). (e) As in (d), but for observational NSWS anomalies. (f) The NSWS change related to LUCC ((e) minus (d)). An 11-year low-pass filtering is applied to anomalies. Black dots in (a–e) are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

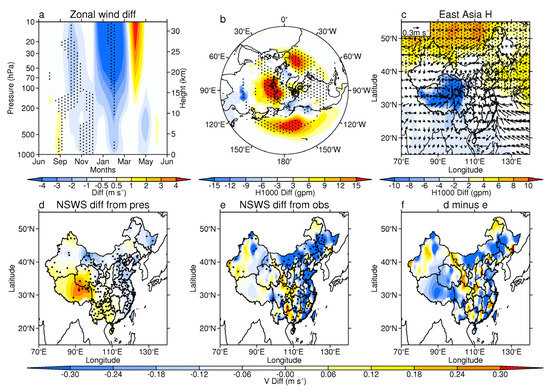

On the interdecadal timescale, the effects of multiple factors may overlap. To isolate the influence of the stratosphere, we analyze the nudging experiments. The CESM2 model successfully captures the weak SPV pattern at 10 hPa (Figure 9a) and the shift in positive height anomalies toward the northern part of Eurasia at 200 hPa (Figure 9b). These shifting positive height anomalies in the polar stratosphere extend downward to the surface, triggering a wave train from the Arctic to the North Pacific (Figure 9c), which is closely similar to the patterns observed in the JRA-55 reanalysis dataset. The surface pressure changes reduce NSWS over eastern China while enhancing it over western China (Figure 9d). Overall, the response of NSWS to the SPV on the interdecadal timescale is weaker than on the interannual timescale. Notably, some differences exist between the geopotential height/NSWS patterns in the model and those in JRA-55. For example, the North Atlantic region shows positive height anomalies in JRA-55 but negative anomalies in the model. This difference likely arises because the observational data are influenced by sea surface temperature signals, while the nudging experiments focus purely on the stratospheric influence.

Figure 9.

Composite differences between weak and strong SPV events in CESM2. (a) 10 hPa geopotential height anomalies; (b) 200 hPa geopotential height anomalies; (c) 1000 hPa geopotential height anomalies; (d) NSWS anomalies. The composite results are averaged by 20 sets of nudging experiments. An 11-year low-pass filtering is used in anomalies and the SPV events are the same as those in Figure 8. Black dots in (a–d) are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

6. Summary and Discussion

The multiscale variability of NSWS and its underlying mechanisms have garnered significant attention over China. However, previous studies have primarily focused on the role of surface forcing and tropospheric dynamics, with limited consideration of stratospheric influences. In this study, we investigate the role of the SPV in winter NSWS variability over China, comparing the distinct impacts of interannual and interdecadal SPV fluctuations.

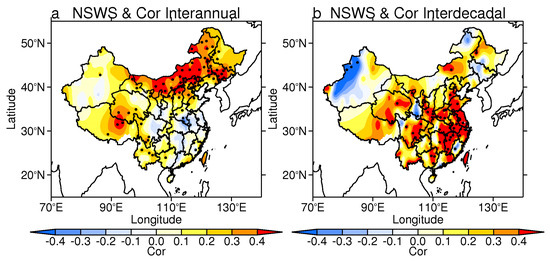

On the interannual timescale, variations in SPV intensity are the most significant factor influencing NSWS over China. The downward propagation of strong SPV signals leads to a positive AO-like pattern in the Northern Hemisphere, while a weak SPV induces the opposite effect. In this case, the polar negative center of the AO shifts toward the North Atlantic, with a corresponding positive center over East Asia. The resulting pressure changes over East Asia influence NSWS in the northern part of China (Figure 10a). On the interdecadal timescale, the SPV causes positive height anomalies over the Arctic, which shift toward Northeast Eurasia—distinct from the interannual pattern. These positive height anomalies trigger a wave train from the Arctic to the North Pacific, impacting the zonal pressure gradient over East Asia and modulating NSWS over eastern China (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Correlation coefficients between simulating NSWS and observational NSWS in interannual and interdecadal scales. (a) Correlation coefficient after applying an 11-year high-pass filter (interannual scale). (b) As in (a), but with an 11-year low-pass filter (interdecadal scale). The simulating NSWS is averaged by 20 sets of nudging experiments. Black dots are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

To avoid interference from other factor, such as AMO and tropospheric AO, we use theoretical experiments to verify the possibility that the stratosphere influences the NSWS in China. Stratospheric nudging experiments are used to verify the dynamic connection between the SPV and NSWS. The nudging experiments can capture the observational AO pattern on interannual timescale, the wave train on interdecadal time scale, and the corresponding NSWS changes. In general, the response of China’s NSWS to interannual variability of SPV is stronger than those to interdecadal variability. In addition, we mainly focus on the independent influence of the SPV. Previous studies have already noted that some factors influencing the NSWS can also affect the SPV, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and Quasi-Biennial Oscillation [47,67,68]. Consequently, the influence of the SPV is subject to considerable interference, which necessitates more detailed explorations.

Author Contributions

Y.L., X.X. and R.Z. developed the idea and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Sailing Program (23YF1401400) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42120104001, 42192563).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The JRA-55 reanalysis datasets are available online at http://jra.kishou.go.jp/. Station observation is from the China Meteorological Administration (http://data.cma.cn/). The model outputs of all experiments are available on application to the corresponding author. The CESM2 model is available from https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/cesm2/, accessed on 16 October 2025.

Acknowledgments

We thank the scientific teams for the JRA-55, CMA and the CESM2 model.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yang Li was employed by the company Gansu Water Resources and Hydropower Survey, Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Liu, C.M.; Tang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.H. Trends in pan evaporationand reference and actual evapotranspiration across the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2007, 112, D12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, A.J.; Woodruff, R.E.; Hales, S. Climate change and human health: Present and future risks. Lancet 2006, 367, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Peng, J.; Zhao, C.A. Wind Speed and Vegetation Coverage in Turn Dominated Wind Erosion Change with Increasing Aridity in Africa. Earths Future 2024, 12, e2024EF004468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Yang, Y.T. Recent Decline in Global Ocean Evaporation Due to Wind Stilling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL114256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, R.; Ziegler, A.; Zeng, Z. Stronger winds increase the sand-dust storm risk in northern China. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2022, 2, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Tie, X.; Li, C.; Ying, Z.; Kai-Hon Lau, A.; Huang, J.; Deng, X.; Bi, X. An extremely low visibility event over the Guangzhou region: A case study. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 6568–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.P.; Chen, Z.J. Wind speed changes and its influencing factors in Southwestern China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 471–481. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, T.Z.; Che, H.Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. The variation in visibility and its relationship with surface wind speed in China from 1960 to 2009. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 131, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhou, M.; Hao, Y.T.; Huang, X.; Tong, D.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, J.; Gu, W.; Wang, L.; et al. Amplified positive effects on air quality, health, and renewable energy under China’s carbon neutral target. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, M.O.; Merlet, P. Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2001, 15, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVicar, T.R.; Roderick, M.L.; Donohue, R.J.; Li, L.; Niel, T.; Thomas, A.; Grieser, J.; Jhajharia, D.; Himri, Y.; Mahowald, N.; et al. Global review and synthesis of trends in observed terrestrial near-surface wind speeds: Implications for evaporation. J. Hydrol. 2012, 416, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, A.; Han, J.; Clark, C.E.; Wang, M.; Dunn, J.; Palou-Rivera, I. Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Shale Gas, Natural Gas, Coal, and Petroleum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, O.; Coban, M.N.; Destek, M.A. Navigating the winds of change: Assessing the impact of wind energy innovations and fossil energy efficiency on carbon emissions in China. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Beyond NIMBYism: Towards an integrated framework for understanding public perceptions of wind energy. Wind Energy 2005, 8, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obama, B. The irreversible momentum of clean energy. Science 2017, 355, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, R.M.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q. A review of wind speed and wind power forecasting with deep neural networks. Appl. Energy 2021, 304, 117766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xu, M.; Hu, Q. Changes in near-surface wind speed in China: 1969–2005. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zha, J.L.; Zhao, D.M. Estimating the impact of the changes in land use and cover on the surface wind speed over the East China Plain during the period 1980–2011. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 46, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zha, J.L.; Zhao, D.M. Evaluating the effects of land use and cover change on the decrease of surface wind speed over China in recent 30 years using a statistical downscaling method. Clim. Dyn. 2017, 48, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zha, J.L.; Zhao, D.M.; Yang, Q.D. Changes of wind speed at different heights over Eastern China during 1980–2011. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 4476–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.L.; Wu, J.; Zhao, D.M. Changes of probabilities in different wind grades induced by land use and cover change in Eastern China Plain during 1980–2011. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2016, 17, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.L.; Shen, C.; Wu, J.; Zhao, D.; Fan, W.; Jiang, H.; Azorin-molina, C.; Chen, D. Effects of Northern Hemisphere Annular Mode on terrestrial near-surface wind speed over eastern China from 1979 to 2017. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2022, 13, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhang, S.Y.; Luo, J.L.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J. Analysis of near-surface wind speed change in China during 1958–2015. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 137, 2785–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Yuan, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Minola, L.; Chang, Y.; Chen, D. March Near-Surface Wind Speed Hiatus over China Since 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL104230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, H.S.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Minola, L.; Chang, Y.; Chen, D. AMO footprint of the recent near-surface wind speed change over China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 114031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xiao, L.; Li, Q. Advances of surface wind speed changes over China under global warming. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci. 2020, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, J.L.; Chuan, T.; Wu, J.; Zhao, D.M.; Luo, M.; Feng, J.M.; Fan, W.X.; Shen, C.; Jiang, H.P. Attribution of terrestrial near-surface wind speed changes across China at a centennial scale. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL108241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chang, C.; Fu, C.; Qi, Y.; Rbock, A.; Robinson, D.; Zhang, H. Steady decline of east Asian monsoon winds, 1969–2000: Evidence from direct ground measurements of wind speed. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2006, 111, D24111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.P.; Ding, Y.H.; Wang, M. Near-surface wind speed changes in eastern China during 1970–2019 winter and its possible causes. Adv. Clim. Chang Res. 2022, 13, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Chen, D.L.; Mcvicar, T.; Guijarro, J.; Deng, K.; Minola, L.; Lee, J.; Son, W.W.; Ma, H.; et al. Variability and trends of near-surface wind speed over the Tibetan Plateau: The role played by the westerly and Asian monsoon. Adv. Clim. Chang Res. 2024, 15, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.L.; Fraedrich, K.; Min, J.Z.; Kang, S.; Zhu, X.; Pekin, N.; Zhang, L. Observed surface wind speed in the Tibetan Plateau since 1980 and its physical causes. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.Z.; Ziegler, A.D.; Searchinger, T.; Yang, L.; Chen, A.; Ju, K.; Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Chen, D.; Liu, J. A reversal in global terrestrial stilling and its implications for wind energy production. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Ding, R.Q. The impact of the AMO on wintertime surface wind speed reversal in Northeast Asia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 014068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Shin, S.W.; Cha, D.H.; Min, S.K.; Byun, Y.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y. Impact of global warming on wind power potential over East Asia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 203, 114747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.L.; Wu, J.; Zhao, D.M. Effects of land use and cover change on the near-surface wind speed over China in the last 30 years. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2017, 41, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.P.; Dunkerton, T.J. Stratospheric harbingers of anomalous weather regimes. Science 2001, 294, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polvani, L.M.; Waugh, D.W. Upward wave activity flux as a precursor to extreme stratospheric events and subsequent anomalous surface weather regimes. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 3548–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, C.I.; Hartmann, D.L.; Sassi, F. Tropospheric Precursors of Anomalous Northern Hemisphere Stratospheric Polar Vortices. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 3282–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmond, M.; Scinocca, J.F.; Kharin, V.V.; Shepherd, T.G. Enhanced seasonal forecast skill following stratospheric sudden warmings. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidston, J.; Scaife, A.A.; Hardiman, S.C.; Mitchell, D.M.; Butchart, N.; Baldwin, M.P.; Gray, L.J. Stratospheric influence on tropospheric jet streams, storm tracks and surface weather. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.J.; Brown, M.J.; Knight, J.; Andrews, M.; O’Reilly, C.; Anstey, J. Forecasting extreme stratospheric polar vortex events. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.P.; Ayarzagüena, B.; Birner, T.; Butchart, N.; Butler, A.; Charlton-Perez, A.; Domeisen, D.; Garfinkel, C.; Garney, H.; Gerber, E. Sudden Stratospheric Warmings. Rev. Geophys. 2021, 59, e2020RG000708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Tian, W.; Sun, C.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Gui, K. Southern Hemispheric jet swing linked to Arctic stratospheric polar vortex. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 044053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.H.; Zhang, J.K.; Cheng, X.Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Tian, W.S. Predicting Sudden Stratospheric Warmings Using Video Prediction Methods. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL113993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, J.K.; Maycock, A.C.; Tian, W.S. Distinct tropospheric anomalies during sudden stratospheric warming events accompanied by strong and weak Ural Ridge. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhou, W.; Tian, W.S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J. A stratospheric precursor of East Asian summer droughts and floods. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhou, W.; Tian, W.S. Holton-Tan effect enhances the influence of the QBO on the surface air temperature around the North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 2025, 63, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.X. Modulation of the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation on the East Asian Surface Air Temperature in Boreal Winter. J. Clim. 2025, 38, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.W.J.; Baldwin, M.P.; Wallace, J.M. Stratospheric connection to Northern Hemisphere wintertime weather: Implications for prediction. J. Clim. 2002, 15, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Garfinkel, C.I.; Wu, T.W.; Lu, Y.; Lu, Q.; Liang, Z. The January 2021 Sudden Stratospheric Warming and Its Prediction in Subseasonal to Seasonal Models. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2021, 126, e2021JD035057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Y.; Ren, R.C.; Li, Y.F.; Yu, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, B.; Sun, M. Continental cold-air-outbreaks under the varying stratosphere-troposphere coupling regimes during stratospheric Northern Annular Mode events. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 7207–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davini, P.; Cagnazzo, C.; Anstey, J.A. A blocking view of the stratosphere-troposphere coupling. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2014, 119, 11100–11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Tian, W.S.; Gray, L.J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, J.; Tian, H. Preconditioning of Arctic Stratospheric Polar Vortex Shift Events. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 5417–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Hitchcock, P.; Maycock, A.C.; Mckenna, C.M.; Tian, W.S. Northern hemisphere cold air outbreaks are more likely to be severe during weak polar vortex conditions. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Hitchcock, P.; Tian, W.S.; Sillin, J. Stratospheric Influence on the Development of the 2018 Late Winter European Cold Air Outbreak. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2022, 127, e2021JD035877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Agel, L.; Barlow, M.; Furtado, J.C.; Kretchmer, M.; Wendt, V. The “polar vortex” winter of 2013/2014. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhou, W. Decadal change in the linkage between QBO and the leading mode of Southeast China winter precipitation. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 7379–7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.Z.; Guan, Z.Y.; Tian, W.S.; Ren, R.C. Recent strengthening of the stratospheric Arctic vortex response to warming in the central North Pacific. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Ota, Y.; Harada, Y.; Ebita, A.; Moriya, M.; Onoda, H.; Onogi, K.; Kamahori, H.; 59. Kobayashi, C.; Endo, H.; et al. The JRA-55 reanalysis: General specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 2015, 93, 5–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, C.S.; Widmann, M.; Dymnikov, V.P.; Wallace, J.; Blade, I. The effective number of spatial degrees of freedom of a time-varying field. J. Clim. 1999, 12, 1990–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.H.; Kim, B.; Kug, J. Temperature variation over East Asia during the lifecycle of weak stratospheric polar vortex. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 5857–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xia, X.; Song, J.; Li, D.; Tian, W.S. Impacts of stratospheric polar vortex changes on tropospheric blockings over the Atlantic region. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 4829–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Yan, Y. Changes of Surface Wind Speed over Qinghai-Xizang Plateau from 1961 to 2020 and Evaluation of the Dynamical Downscaling Simulations. Plateau Meteorol. 2022, 41, 963–976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Yan, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Gao, L. An analysis of the urbanization contribution to observed terrestrial stilling in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region of China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 034062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Bracegirdle, T.J.; Phillips, T.; Bushell, A.; Gray, L. Mechanisms for the Holton-Tan relationship and its decadal variation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2014, 119, 2811–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, S.; West, B.J. Is climate sensitive to solar variability? Phys. Today 2008, 61, 50–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, M.; Shen, C.; Chen, D. ENSO-driven seasonal variability in near-surface wind speed and wind power potential across China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2025GL115537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhu, G.; Xu, X.X.; Zhang, Y. Vertical structure of the quasi-biennial oscillation influences the strength of the Holton–Tan effect. Clim. Dyn. 2025, 63, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).