Abstract

Given the crucial role of the personalized management and treatment of hearing loss (HL), etiological investigations are performed early on, and genetic analysis significantly contributes to the determination of most syndromic and nonsyndromic HL cases. Knowing hundreds of syndromic associations with HL, little comprehensive data about HL in genomic disorders due to microdeletion or microduplications of contiguous genes is available. Together with the description of a new patient with a novel 3.7 Mb deletion of the Xq21 critical locus, we propose an unreported literature review about clinical findings in patients and their family members with Xq21 deletion syndrome. We finally propose a comprehensive review of HL in contiguous gene syndromes in order to confirm the role of cytogenomic microarray analysis to investigate the etiology of unexplained HL.

1. Introduction

Hearing loss (HL), the most prevalent sensorial defect at birth and during childhood, may be due to an alteration of the mechanic conduction of hearing waves through the external and middle ear, to a cochlear or neural defect in the signal transduction, or both, as it happens in conductive HL, in sensorineural HL (SHL) or in mixed HL, respectively [1,2]. In syndromic HL, the deficit may be associated with other medical findings, including malformations, anomalies, or pathologic alteration in any organ or system. Of note, approximately 20% of children presenting with HL as the only initial clinical feature will subsequently be diagnosed with syndromic HL [3,4]. The implementation of universal newborn hearing screening and audiologic surveillance make an early diagnosis of HL possible, optimizing patients’ management and allowing for prompt treatments [5]. Subsequent to the identification of HL, a detailed clinical and genetic work-up follows in order to reach the etiological diagnosis and to offer personalized care and follow-up to the patients and their families. These points are crucial especially in cases in which concurrent disability is present, as that may affect the outcomes.

Genetic causes are identified in almost 80% of prelingual HL cases [3], and more than 600 different syndromic conditions are known [6].

SHL is mostly the consequence of pathogenic variants (SNVs, Single Nucleotide Variants or indels) in single genes, while Copy Number Variations (CNVs) are an underestimated cause of non-syndromic HL. Indeed, pathogenic deletions are expected to occur sporadically across at least 100 HL-causing genes [7]. Current data show that sequence analyses of 100 HL genes together with the assessment of CNVs can identify a genetic cause in roughly one out of two patients with suspected hereditary HL, whereas ~20% of the patients with an etiopathogenetic diagnosis carry at least a causative CNV. However, only a few studies, mainly single-case or small cohort reports, have focused on contiguous gene syndromes exhibiting HL in association with congenital anomalies, neurodevelopmental disorders, and various syndromic conditions [8,9,10].

We report on a young boy with congenital, severe SHL associated with an inner ear malformation, who developed a neurodevelopmental disorder with autistic features, and choroideremia consistently with the detected novel hemizygous deletion of 3.7 Mb in Xq21.1q21.2. We therefore propose an extensive review of patients and families with Xq21 deletion syndrome and we suggest HL as a possible early-onset feature of contiguous gene syndromes. In addition, we propose to hold gross DNA rearrangements in consideration as a possible cause of HL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Report

The clinical report summarizes information from a complete collection and revision of clinical and molecular documentation. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) multi-gene panels were performed at R&I, and CGH arrays took place at the Genetic Laboratory of Perugia Hospital. Molecular analysis was performed in trio (proband and biological parents) from DNA extracted by peripheral blood. Multidisciplinary evaluations, including audiological, logopedic, neurological/NPI, cardiological assessments, inner ear imaging, abdominal US, brain MRI, and clinical follow-up, were performed at IRCCS Burlo Garofolo in Trieste.

2.2. Literature Review

- (1)

- Xq21 deletion syndrome

A collection of reported cases was selected from OMIM [11] and Pubmed [12], and data were extrapolated and compared. A summary of the main findings is presented.

- (2)

- Contiguous gene syndromes with HL

We researched and selected recent papers providing a comprehensive list of contiguous gene syndromes, microdeletion and microduplication syndrome in humans, and data merging. Searches of phenotype description of the selected syndromes took place on OMIM [11]; Orphanet [13]; Genereview [14]; and Pubmed [12] with a focus on the presence and characteristics of HL. A summary of the main findings is presented.

3. Clinical Report

The child was referred to our center at 3 years of age for a second opinion regarding a delay in obtaining positive results from speech therapy and psychomotricity.

3.1. Family History

The proband is an only child, born at term from a pregnancy obtained by heterologous intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), with oocytodonation, which had an unremarkable course. The father suffers from ischemic stroke consequences in essential thrombocythemia. There is no known family history of hearing deficits.

3.2. Clinical Presentation

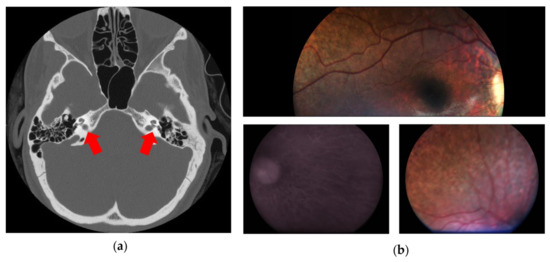

The proband’s newborn hearing screening testing with otoacoustic emission failed bilaterally (“REFER”), and the second level audiologic evaluation (including tympanometry, diagnostic distortion product otoacoustic emissions, and click-evoked auditory brainstem response (ABR) testing) revealed a bilateral SHL, with an estimated hearing threshold of 60–70 dB HL in the right and 70–80 dB HL in the left ear. At 4 months of age, the child was fitted with two hearing aids. As part of the clinical investigations indicated for permanent congenital HL, a temporal bone CT revealed a bilateral inner ear malformation characterized by anomalous fusion of the internal auditory canal and the basal cochlear turn, a cochlea with an absent modiolus, the presence of the interscalar septa, and bulbous dilatation of the fundus of the internal auditory canal as shown in Figure 1a. Incomplete partition type III (IP3) was classified according to the Sennaroglu’s revised classification [15]. Absence of the modiolus of the cochlea and bulbous dilatation of the fundus of the internal auditory canal was confirmed by MRI. Brain MRI was normal.

Figure 1.

This figure shows the main clinical features of the patient. (a) Computed tomography of temporal bones (axial plane) showing bulbous dilatation at the distal ends of internal auditory canals; the interscalar septa of the cochlea are present, but the modiolus is absent (red arrows). (b) Fundus oculi showing choroidal degeneration and diffuse retinal pigmented epithelium dystrophy.

The cardiological assessment, ECG, echocardiography, abdominal ultrasound, and ophthalmological examination performed at 2 years of age were all reported as unremarkable. The parents reported a motor delay with late achievement of milestones: he reached the sitting position without support at 11 months, crawled at 18 months, and achieved independent walking at 28 months, initially with a wide base and very unstable gait. Because of the impairment of global and gross motor skills and the presence of bilateral pes planum, he was treated with alternating orthotics and underwent physiotherapy and neuro-psychomotricity programs. Sphincter continence was also significantly delayed. Speech and language development was severely compromised with delays in comprehension, very limited verbal expression, and several phonemic errors, despite early speech therapy and neuropsychotherapy.

Overall, the audiological evaluation carried out at 3 years and 2 months of age confirmed a severe bilateral SHL associated with inner ear malformation. Although hearing abilities were not easily assessed due to the presence of attention difficulties, the hearing aid fitting provided a satisfactory amplified hearing threshold (30 dB HL). In contrast, motor, communication, and language delays were significantly worse than expected, considering the early amplification and rehabilitation. The following neurological consultation documented the presence of stereotypies (e.g., rocking of the head and flickering with the hands), poor gaze engagement, impulsive-oppositional behavior, and limited attention. The diagnosis was of Mixed Specific Developmental Disorder and attention deficit disorder. At the neurological follow-up, a neurodevelopmental disorder with global psychomotor delay and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was diagnosed. At 3 years and 2 months of age, weight and height were approximately in the 30th percentile with OFC about 53.5 cm (unreliable measurement due to poor cooperation) (98th pc). He showed dolichocephaly, a prominent forehead, bilateral epicanthus, periorbital fullness, long eyelashes, and a broad nasal tip with anterverted nostrils. Mild dorsal hypertrichosis and keratosis pilaris on the arms and thighs were also evident, together with flat feet.

3.3. Genetic Analysis

Following clinical genetic evaluation, the NGS panel analysis of genes associated with congenital HL suggested a deletion in the POU3F4 gene. Molecular karyotyping was then performed for confirmation: the CGH array revealed a hemizygous deletion of approximately 3.7 Mb in the chromosomal region Xq21.1q21.2, between the nucleotides 81464567 and 85234239 (release GRCh37), encompassing POU3F4, CYLC1, RPS6KA6, HDX, APOOL, SATL1, ZNF711, and POF1B and partially (exons 4–15) involving CHM. The deletion was inherited from the oocyte donor.

3.4. Ophthalmological Follow-Up

Following a reverse phenotyping approach, ophthalmological follow-up performed at 4 years of age showed a bilateral widespread pigment clumping in the middle retinal periphery. Snellen visual acuity was performed binocularly only, in accordance with age, and the kinetic binocular visual field resulted normal for age (visual acuity was 20/32) with a slightly hyperopic refraction, and with normal bilateral temporal extension (of 70 degrees). At the age of 5 years, visual acuity and the visual field were still normal. The electroretinogram (full-field ERG) showed a significant reduction in the scotopic component (30 micronvolts) and a modest reduction in the photopic one (60 micronvolts; a and b waves’ latencies were 21 ms and 43 ms, respectively). Finally, at the age of 6, areas of chorioretinal atrophy were found at the fundus, bilaterally in the middle retinal periphery, as well documented by retinography, shown in Figure 1b.

4. Xq21 Deletion Syndrome: Literature Review

At least 29 probands (28 males and 1 female) belonging to 14 unrelated families of different ancestries have been reported with syndromic association due to Xq21 deletion before our patient. Except for a de novo deletion and a patient whose mother was not genotyped, all the Xq21 deletions were maternally inherited.

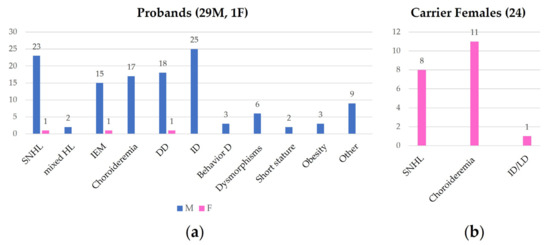

We revised the molecular and clinical findings of all the affected patients (30) and their carrier mothers, when available. Carrier females (24) were evaluated following the molecular diagnosis in their son(s). A well-described cohort of heterozygous females has been also considered [16]. Clinical findings of the patients and the carrier females are summarized in Figure 2, which was drawn from the data reported in Supplementary Table S1. In the table, the breakpoints of the deletions are also shown.

Figure 2.

This figure shows the frequence of clinical findings in affected probands (a) and in carrier female family members (b). SNHL: sensorineural hearing loss; HL: hearing loss; IEM: inner ear malformation; DD: developmental delay; ID: intellectual disability; Behavior D: behavior disorder; LD: learning disability.

All the reported probands had a major hearing issue: they all present bilateral sensorineural or mixed HL, of variable degree varying from moderate to profound, rarely asymmetric, and without documentation of progression according to the available follow-up. HL diagnosis was made during childhood and assumed to be “likely congenital” in some cases. Our proband is the only one in which HL is surely congenital, since the diagnosis was made after failing newborn hearing screening. All patients who underwent temporal bone imaging presented inner ear malformation, generally consistent with an IP3, as the here-reported patient. In addition, one patient underwent left-middle-ear exploration and stapedectomy, showing fixation of the stapes to the foot plate with a patent cochlear aqueduct and experienced marked perilymphatic gusher on stapedectomy, supporting DFNX2. Despite early hearing aid fitting and treatment, verbal comprehension and expression are significantly compromised, as we observed in our patient. Except for some patients, global developmental delay is a frequent concomitant feature with generally worse speech than motor development and a variable degree of intellectual disability, from moderate to profound. Hypotonia has also been reported in some patients (4). Behavior anomalies have been more rarely mentioned, with one patient presenting with psychotic behavioral and relational disorder and another showing severe social disability. In our patient, the comorbidity with attention deficit disorder and ASD probably contributed to poor verbal outcomes. Ophthalmologic signs and symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of choroideremia are present in a minority of children, and in most of the patients, it has been described as appearing after childhood. Facial phenotype, when reported (6), is not specific and clinically recognizable. Flat feet are present in our patient and in two other siblings (3) [17]. Among other clinical reported features, asymptomatic renal pelvic dilatation, a single microematuria episode, vescicoureteral reflux grade V, brain anomaly with mega cisterna magna, cerebral cysticercosis, and vestibular problems have been reported once, whereas obesity, short stature, and strabismus are rare findings.

In the cohort, a female proband exhibited bilateral HL, IP3, and developmental delay; no information about fundus oculi was provided [18,19]. Heterozygous females are generally asymptomatic, with normal hearing and vision. However mild ophthalmological signs including choroidal atrophy and retinal pigmentary stippling have been documented, as well as bilateral sensorineural mild HL [16,18] (Figure 2).

5. Contiguous Gene Syndromes with HL: Literature Review

The phenotypes of 192 recurrent and non-recurrent microdeletion and microduplication syndromes listed by Wetzel and Darbro [20], and 99 microdeletion and microduplication syndromes reported and described by Nevado et colleagues [9], have been revised with special focus on the presence, prevalence, and characteristics of HL. The clinical description of diseases mainly relies on information available in the free databases OMIM [11], Orphanet [13], and Genereview [14] and in papers in Pubmed [12], which could not be comprehensive of the totality of contiguous gene syndromes with HL. In particular, very rare and sporadic microdeletion or microduplications presenting with HL have not been included in our review.

Starting from over 200 microdeletion/microduplication syndromes [9,20], we extrapolated 56 imbalance-sensitive genomic loci associated with more than 60 syndromes, which may include HL as a clinical finding. Conductive, sensorineural, and mixed HL may occur commonly, occasionally, or rarely in the contiguous gene syndrome. In Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, we focus on HL characteristics and HL candidate or responsible genes, whereas we provide only a summary of the main clinical features (column “Phenotype”) of the identified microdeletions/microduplication syndromes.

Table 1.

Microdeletion syndromes with hearing loss (HL).

Table 2.

Microduplication syndromes with HL.

Table 3.

Reciprocal microdeletion and microduplication syndromes with HL.

Few cases of genomic regions sensitive to microduplications have been associated with HL (4), as displayed in Table 2.

Finally, HL may present in both the reciprocal microdeletion/microduplication syndromes (11) for some recurrent genomic loci (7), displayed in Table 3.

6. Discussion

6.1. Xq21 Deletion Syndrome: Literature Review

We revised 22 clinical histories spanning over forty years and described a novel proband [17,18,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. By reporting the phenotype exhibited by males in a three-generation family, i.e., choroideremia, obesity, and congenital deafness, Ayazi and colleagues suggested the existence of a new X-linked syndrome [55]. The pathomechanism underlying the condition present in this family and in a similar one, i.e., submicroscopic deletions in Xq21, was subsequently identified by Nussbaum RL [51]. Despite the limits of available technologies, it was possible to map the critical region for choroideremia and HL between DXYS1 and DXS72 markers [51,52,53]. The technological optimization for the deletion breakpoint determination in the first family was later published together with the family’s clinical follow-up and the description of other similar patients [52,56]. However, only with the advent of MLPA and microarray technologies (CGH or SNP) was it possible to define the breakpoints of the Xq21 deletions and reveal that its size varies from 5.2 [17] to 16 Mb [57]. Our patient is the first example of Xq21 deletion identified through a multi-gene NGS panel after neonatal diagnosis of an apparently isolated HL. Excluding the patient described by Song et al. [57] affected by HL only as carrier of a 1–1.5 Mb microdeletion at about 90 kb upstream of POU3F4 (Table S1), with a size of 3.7 Mb, it is the smallest Xq21 deletion and the only among those characterized deleting part of CHM (exons 4–15), whereas POU3F4, CYLC1, RPS6KA6, HDX, APOOL, SATL1, ZNF711, and POF1B were fully encompassed. Indeed, the breakpoints of only 3 out of the 12 different Xq21 deletions (Table S1) were characterized through array technologies (CGH or SNP): genes involved in our patient were fully encompassed.

POU3F4 and ZNF711 haploinsufficiency is causative of the expression of audiological and neurodevelopmental phenotypes, respectively.

Indeed, POU3F4 (OMIM #300039) is implicated in nonsyndromic X-linked deafness-2 (DFNX2, DFN3OMIM #304400), characterized by sensorineural or mixed HL in association with IP3, cochlear hypoplasia, and/or stapes fixation. In males, HL begins prelingually and progresses over time. Females with pathogenic variants in POU3F4 tend to be less severely affected, with rare postlingual, mild HL and very rarely with inner ear anomalies [16]. DFNX2 is also caused by deletions and insertions located upstream of the gene, in a putative regulatory element region. POU3F4 in DFNX2 may be partially or completely deleted [61,62,63].

POU3F4 encodes a transcription factor that restricts the proliferation and lineage potential of neural stem cells [63]. It plays a role in neurogenesis of the inner ear, mediating the inner radial bundle formation [64]. In mice models for DFNX2, a dysfunction of spiral ligament fibrocytes in the lateral wall of the cochlea, leading to reduced endocochlear potential, underlies the sensorineural loss. Considering the pathogenic mechanism, some authors have recently proposed to develop a therapeutic approach in male Pou3f4 -/y mice based on gene transfer in cochlear spiral ligament fibrocytes mediated by an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector with a strong tropism for the spiral ligament (AAV7). Complementary gene replacement before HL progression to profound deafness could represent an attractive strategy to prevent fibrocyte degeneration and to restore normal cochlear functions and properties, including a positive endocochlear potential [65].

ZNF711 (OMIM #314990) codes for the zinc-finger protein 711, ZNF711, the specific function of which is unknown. Some evidence suggests that it is crucial for brain development, probably acting as a transcription factor for genes required for neuronal development [66]. Nonsense, frameshift, and missense variants have been reported in ZNF711-related nonsyndromic intellectual developmental disorder, X-linked 97 (OMIM #300803), characterized by generally mild motor and severe speech developmental delay, mild-to-moderate intellectual disability in males, and autistic features in some of them. Despite some mild phenotypic features having been described, there are no distinctive facial dysmorphologies that would allow clinical recognition [67]. Female carriers do not show manifestations.

Most of the pathogenetic variants in CHM (OMIM #303100), associated with choroideremia, are nonsense, splicing, frameshift, and small intragenic deletion/duplications, resulting in the truncation or complete absence of Rab escort protein 1 (REP1) [68,69,70,71].

POF1B (OMIM #300603) has been proposed as a candidate gene for Premature ovarian failure 2B (300604) in female carriers, but controversial findings have been reported [72,73,74].

Although HDX and RPS6KA6 are not OMIM disease genes, they are candidates for intellectual disability. For instance, two alterations (one duplication and one translocation) involving the gene and associated with X-linked intellectual disability and premature ovarian failure, respectively, have been reported in HGMD® [75]. RPS6KA6 encodes for a constitutively active kinase that belongs to the same family of a protein whose loss of function causes Coffin–Lowry syndrome, a syndromic intellectual disability with hypotonia. Moreover, at least two missense variants in RPS6KA6 have been reported in association with psychomotor retardation, ASD and HL [75].

Although some authors suggested an age-dependent penetrance for choroideremia [17], in our patient, an early onset of the phenotype has been documented. As reported for females carriers of POU3F4 pathogenic variants [16], Xq21 deletion carrier females can also exhibit mild ophthalmological signs including choroidal atrophy and retinal pigmentary stippling, as well as bilateral mild SHL and rarely inner ear anomalies. Moreover, even a female may exhibit the full spectrum of the Xq21 deletion syndrome, that includes neurodevelopmental delay (Figure 2) [16,18]. Furthermore, we underline that the identification of heterozygous females is crucial for reproductive counseling as well as for clinical evaluation and follow-up.

The phenotype of patients with contiguous gene syndrome may be more complex than the sum of specific signs and symptoms related to single genes. In particular, the co-occurrence of double sensorial deficit and neurodevelopmental disorder significantly impacts on prognosis, outcomes, and management choices in children with Xq21 deletion. Interestingly, neurodevelopmental issues have been frequently observed in children with POU3F4-related IP3, even in patients who are carriers of pathogenic variants [18].

6.2. Considerations on Etiologic Diagnosis of HL

Early identification of HL and consequent etiology determination impact the personalization of the patient’s follow-up, prognosis and outcome prediction, and in certain cases also the choice of treatments and therapeutic options. In syndromic HL, a multidisciplinary follow-up is required, according to the phenotype.

Following the diagnosis of POU3F4-related HL, imaging is mandatory in search of inner ear anomalies [61]. Cochlear implant surgery in IP3-III may be difficult due to the leakage of cerebrospinal fluid into the middle ear cavity when opening the round window, or performing the cochleostomy, with a prolonged “gusher” [76,77]. This increases the risk of further post-surgical cerebrospinal fluid leaks which can also lead to rhinorrhea, meningitis, and intracranial infections. A second surgical risk concerns the possibility of incorrect positioning of the electrodes in the internal acoustic canal due to the absence of the modiolus and the widening of the bottom of the internal acoustic canal [77]. Therefore, the choice of cochlear implant surgery requires careful counseling with the family and the sharing of therapeutic rehabilitation choices [78].

The identification of the causative genomic Xq21 deletion allowed for the indication of our patient specific follow-up and the early diagnosis of choroideremia. Choroideremia results from the progressive, centripetal loss of photoreceptors and choriocapillaris, secondary to the degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) [79]. Affected individuals present in late childhood or early teenage years with nyctalopia and progressive peripheral visual loss. Typically, by the fourth decade, the macula and fovea also degenerate, resulting in advanced sight loss [80,81]. In the first phases of this dystrophy, peripheral pigmentary changes may characterize the retina of affected patients [82]. At a later time, distinct regions of chorioretinal atrophy are usually visible. Of note, these degenerative alterations usually start at the equator and progressively, in a centripetal direction, involve the posterior pole and the peripapillary region [83]. These retinal changes can lead to the appearance of multiple scotomas in the peripheral visual field [84]. The full-field ERG may have reduced amplitude, initially in the scotopic component only, or be extinct [83,85]. Children under 7 years have rarely been diagnosed [82,84,85]. In our case, considering the initial alterations of the fundus as early as 4 years, the presence of areas of chorioretinal atrophy at 6 years, and an altered ERG at 5 years, which presented an initial involvement of the retinal cones, the ophthalmologic involvement is to be considered very serious with probable poor outcome and early visual loss. Close audiologic evaluations are obviously scheduled for the patient, also considering the possibility of hearing impairment progression. Therapeutic options have to consider the increased risk of complete loss of hearing in the case of middle ear surgery due to the identification of a specific inner ear anomaly.

In addition, the etiological diagnosis allows for the definition of the recurrent risk and the discussion of reproductive options in family counseling. In each pregnancy, the apparently healthy mother of a male proband has a 50% chance of transmitting the CNV loss; consequently, males who inherit the deletion will be affected, whereas females may be healthy or symptomatic. Furthermore, carrier mothers should undergo hearing and vision evaluations and follow-up. In the here-reported patient, challenges in genetic counseling emerged in both the donor and recipients of the oocyte, facing new ethic, legislative, and clinical needs.

6.3. HL in Contiguous Gene Syndromes

Unraveling the etiology of syndromic HL means we must consider the involvement of a single gene with a pleiotropic effect, or of two genes in double diagnoses as well as contiguous gene syndromes. Contiguous gene syndromes include genomic disorders with reciprocally deleted or duplicated chromosomal regions and microdeletion/microduplication syndromes. In these last ones, CNVs may randomly involve any genomic region, causing variable clinical presentations [86,87]. Of note, few contiguous gene syndromes may exhibit isolated HL, such as in female carriers of Xq21 deletion, in the frequent autosomal recessive 15q15.3 deletion syndrome in females, or in the very rare 9q21.11 duplication syndrome. We then focused on the pathomechanism or susceptibility factors for HL. Anatomical features, such as craniofacial abnormalities and ear malformations, immune deficit, and susceptibility to frequent ear infections, may contribute to conductive or mixed HL (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). Inner ear malformation has been reported not only in Xq21 microdeletion syndrome, in which HL and IP3 are common and specific findings are related to POU3F4 haploinsufficiency, but also in 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome, characterized by incomplete penetrance and an extremely variable phenotype (Table 3).

As shown in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, in nearly half of the contiguous gene syndromes, there are HL candidate genes. Some of them (13) are known to be causative of monogenic hereditary HL according to the deafness database [38]. We can therefore hypothesize that they may be involved in causing HL in the contiguous gene syndromes, where they are deleted or duplicated. For the remaining half of contiguous gene syndromes, the etiological mechanism of HL is unknown. We can only infer that dosage-sensitive genes mapped into the rearrangements might be candidates for HL. COCH is associated both with autosomal dominant nonsyndromic HL with variable penetrance of vestibular malfunction (DFNA9), Meniere’s disease, and possibly glaucoma and with autosomal recessive nonsyndromic HL. SERPINB6, MYO15A, and OTOA have been associated with autosomal recessive non-syndromic HL; thus, a possible second-hit event could be hypothesized in patients with the relative deletion syndromes exhibiting HL. USH1C may be associated both with autosomal recessive nonsyndromic HL and with Usher syndrome. Bilallelic deletions in 15q15.3 involving STRC/CATSPER are responsible for autosomal recessive nonsyndromic HL in females and autosomal recessive HL with asthenoteratozoospermia in males. HL may also be due to the presence of a pathogenic SNV in STRC in trans with the deletion. Finally, similarly to the disease mechanism related to POU3F4, COL4A5 causes Alport syndrome both in case of a pathogenetic SNV or complete gene deletion.

6.4. The Role of Chromosomal Microarray in HL

Recently, the European Network for Genetic Hearing Impairment published recommendations for the evaluation of prelingual HL, underling the indication of chromosome assessment by a CGH array, investigating different genes located contiguously on a chromosome segment, in case of a polymalformative syndrome, or a set of clinical signs associated with deafness that does not evoke a known diagnosis [88]. With mostly genetic HL explained by monogenic conditions, isolated chromosomal microarray testing in an individual with apparent nonsyndromic HL has a low diagnostic yield, as stated in the dedicated GeneReviews page on the genetics of HL [89]. Congenital HL may actually be isolated in several cases, due to environmental causes such as CMV infection or due to a genetic cause, including the most frequently mutated GJB2 gene or large numbers of other genes [3]. Since there are hundreds of syndromes presenting with congenital HL and characterized by additional signs and symptoms manifesting after birth, during childhood or later, caution should be posed in the definition of “nonsyndromic HL” at birth, in early infancy, and during childhood, especially before a definite etiologic diagnosis. With this in mind, the choice of comprehensive genetic analysis is nowadays preferred to HL multi-gene panels. In the starting era of neonatal genomic screening, exome sequencing has been proposed as an efficient first-tier analysis to screen for monogenic causes of congenital HL [90]. The promising benefits of early etiologic diagnosis by NGS strategies are arising, together with challenges in the interpretation of molecular data, related to the possibility of a partial phenotype at birth, variant of uncertain significance, and limited genotype–phenotype correlations. Whenever comprehensive NGS tests turn out to be nonconclusive, genomic disease mechanisms should be considered.

In contiguous gene syndromes, HL may be caused by the presence of dosage-sensitive gene(s) mapped in the CNV or gene disruption at the CNV breakpoint. Although chromosomal microarray testing in an individual with HL has a low diagnostic yield, we identified about 50 loci associated with almost 60 contiguous gene syndromes that could exhibit HL. As discussed in the previous paragraph, in some of them, we already know or can hypothesize the gene(s) involved in or that can cause HL.

Congenital HL identified by newborn hearing screening may be the first clinical feature in those microdeletion or microduplication syndromes exhibiting minor congenital anomalies, usually undetectable by prenatal imaging, such as inner ear malformation, neurodevelopmental disorder, and other sensorial defects. Indeed, only in a minority of the reviewed microdeletion or microduplication syndromes, such as Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (4p16.3 DS, Table 1), Cri-du Chat syndrome (5p15 DS, Table 1), and microdeletion or microduplications associated with split hand/foot malformation, do patients exhibit at birth a recognizable pattern of signs/multiple congenital anomalies. This is the subgroup that could be diagnosed in a prenatal setting [91].

According to the existing recommendations, the evidence, and this review, we point out that we should consider contiguous gene syndromes and perform CMA or locus-specific MLPA analysis in patients exhibiting HL whenever a deletion is suspected at NGS or only a monoallelic variant has been identified in patients in which a recessive syndrome is supposed, in evocative syndromic associations, and in undiagnosed patients with likely syndromic HL. Finally, we believe that this review may help geneticists, audiologists, and clinicians to counsel about HL in contiguous gene syndromes, especially in newborns.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes15060677/s1, Table S1: Comprehensive genomic and clinical features of probands and carrier family members with Xq21 deletion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O.; methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, and tables preparation, A.F. and M.T.B.; writing—review and editing, E.O.; patient evaluation P.M., V.G., G.R. and E.O.; molecular analysis, P.P.; genetic evaluation and follow-up, P.P. and M.T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research presented in the manuscript received funding from Institute for Maternal and Child Health-IRCCS “Burlo Garofolo”—Trieste (RC 17/23), nominated by the Italian Ministry of Health.

Informed Consent Statement

The studies involving humans were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo. Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all subjects involved in the study/was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patient’s family. They acknowledge all their colleagues who are involved daily in patients’ and their families’ care. We are very grateful to Ginevra Morgante for English revision.

Conflicts of Interest

AF is now an external consultant for Menarini Silicon Biosystems S.p.A. working on the cbNIPT project. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Morton, C.C.; Nance, W.E. Newborn Hearing Screening—A Silent Revolution. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2151–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Informal Working Group on Prevention of Deafness and Hearing Impairment Programme Planning (1991: Geneva, Switzerland) & World Health Organization. Programme for the Prevention of Deafness and Hearing Impairment. Report of the Informal Working Group on Prevention of Deafness and Hearing Impairment Programme Planning, Geneva, 18–21 June 1991. Art. fasc. WHO/PDH/91.1. Unpublished. 1991. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/58839 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Korver, A.M.H.; Smith, R.J.H.; Van Camp, G.; Schleiss, M.R.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.A.K.; Lustig, L.R.; Usami, S.; Boudewyns, A.N. Congenital hearing loss. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.J.H.; Bale, J.F.; White, K.R. Sensorineural hearing loss in children. Lancet 2005, 365, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Year 2019 JCIH Position Statement. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/jehdi/vol4/iss2/1/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Lieu, J.E.C.; Kenna, M.; Anne, S.; Davidson, L. Hearing Loss in Children: A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 2195–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, A.; Kolbe, D.L.; Azaiez, H.; Sloan, C.M.; Frees, K.L.; Weaver, A.E.; Clark, E.T.; Nishimura, C.J.; Black-Ziegelbein, E.; Smith, R.J.H. Copy number variants are a common cause of non-syndromic hearing loss. Genome Med. 2014, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deak, K.L.; Horn, S.R.; Rehder, C.W. The evolving picture of microdeletion/microduplication syndromes in the age of microarray analysis: Variable expressivity and genomic complexity. Clin. Lab. Med. 2011, 31, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevado, J.; Mergener, R.; Palomares-Bralo, M.; Souza, K.R.; Vallespín, E.; Mena, R.; Martínez-Glez, V.; Mori, M.Á.; Santos, F.; García-Miñaur, S.; et al. New microdeletion and microduplication syndromes: A comprehensive review. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2014, 37 (Suppl. 1), 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weise, A.; Mrasek, K.; Klein, E.; Mulatinho, M.; Llerena, J.C., Jr.; Pekova, S.; Bhatt, S.; Kosyakova, N.; Liehr, T. Microdeletion and Microduplication Syndromes. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2012, 60, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home–OMIM. Available online: https://www.omim.org/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Orphanet. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/it (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- GeneReviews®–NCBI Bookshelf. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1116/ (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Sennaroğlu, L.; Demir Bajin, M. Classification and Current Management of Inner Ear Malformations. Balk. Med. J. 2017, 34, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlin, S.; Moizard, M.P.; David, A.; Chaissang, N.; Raynaud, M.; Jonard, L.; Feldmann, D.; Loundon, N.; Denoyelle, F.; Toutain, A. Phenotype and genotype in females with POU3F4 mutations. Clin. Genet. 2009, 76, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iossa, S.; Costa, V.; Corvino, V.; Auletta, G.; Barruffo, L.; Cappellani, S.; Ceglia, C.; Cennamo, G.; D’Adamo, A.P.; D’Amico, A.; et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of a family carrying two Xq21.1-21.3 interstitial deletions associated with syndromic hearing loss. Mol. Cytogenet. 2015, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Smeds, H.; Wales, J.; Karltorp, E.; Anderlid, B.-M.; Henricson, C.; Asp, F.; Anmyr, L.; Lagerstedt-Robinson, K.; Löfkvist, U. X-linked Malformation Deafness: Neurodevelopmental Symptoms Are Common in Children With IP3 Malformation and Mutation in POU3F4. Ear Hear. 2022, 43, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeds, H.; Wales, J.; Asp, F.; Löfkvist, U.; Falahat, B.; Anderlid, B.-M.; Anmyr, L.; Karltorp, E. X-linked Malformation and Cochlear Implantation. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetzel, A.S.; Darbro, B.W. A comprehensive list of human microdeletion and microduplication syndromes. BMC Genom. Data 2022, 23, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.T.; Omer, M.; Hellens, S.W.; Zwolinski, S.A.; Yates, L.M.; Lynch, S.A. Microdeletion 1p35.2: A recognizable facial phenotype with developmental delay. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2015, 167A, 1916–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miceli, M.; Failla, P.; Saccuzzo, L.; Galesi, O.; Amata, S.; Romano, C.; Bonaglia, M.C.; Fichera, M. Trait–driven analysis of the 2p15p16.1 microdeletion syndrome suggests a complex pattern of interactions between candidate genes. Genes Genom. 2023, 45, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, B.I.; Ogilvie, C.; Wieczorek, D.; Wakeling, E.; Sikkema-Raddatz, B.; van Ravenswaaij-Arts, C.M.A.; Josifova, D. 3p14 deletion is a rare contiguous gene syndrome: Report of 2 new patients and an overview of 14 patients. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2015, 167, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto-Shimojima, K.; Okamoto, N.; Matsumura, W.; Okazaki, T.; Yamamoto, T. Three Japanese patients with 3p13 microdeletions involving FOXP1. Brain Dev. 2019, 41, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanepoel, D. Auditory pathology in cri-du-chat (5p-) syndrome: Phenotypic evidence for auditory neuropathy. Clin. Genet. 2007, 72, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Linhares, N.D.; Svartman, M.; Rodrigues, T.C.; Rosenberg, C.; Valadares, E.R. Subtelomeric 6p25 deletion/duplication: Report of a patient with new clinical findings and genotype-phenotype correlations. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 58, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Valle, A.; Wang, X.; Potocki, L.; Xia, Z.; Kang, S.-H.L.; Carlin, M.E.; Michel, D.; Williams, P.; Cabrera-Meza, G.; Brundage, E.K.; et al. HERV-mediated genomic rearrangement of EYA1 in an individual with branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2010, 152A, 2854–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, K.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.; Blaydon, D.; Lindley, K.J.; Thompson, D.A.; Kriss, T.; Rajput, K.; Ramadan, D.G.; Al-Mazidi, Z.; Cosgrove, K.E.; et al. Infantile hyperinsulinism associated with enteropathy, deafness and renal tubulopathy: Clinical manifestations of a syndrome caused by a contiguous gene deletion located on chromosome 11p. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 17, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitner-Glindzicz, M.; Lindley, K.J.; Rutland, P.; Blaydon, D.; Smith, V.V.; Milla, P.J.; Hussain, K.; Furth-Lavi, J.; Cosgrove, K.E.; Shepherd, R.M.; et al. A recessive contiguous gene deletion causing infantile hyperinsulinism, enteropathy and deafness identifies the Usher type 1C gene. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpinelli, M.R.; Kruse, E.A.; Arhatari, B.D.; Debrincat, M.A.; Ogier, J.M.; Bories, J.-C.; Kile, B.T.; Burt, R.A. Mice Haploinsufficient for Ets1 and Fli1 Display Middle Ear Abnormalities and Model Aspects of Jacobsen Syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grati, F.R.; Lesperance, M.M.; De Toffol, S.; Chinetti, S.; Selicorni, A.; Emery, S.; Grimi, B.; Dulcetti, F.; Malvestiti, B.; Taylor, J.; et al. Pure monosomy and pure trisomy of 13q21.2–31.1 consequent to a familial insertional translocation: Exclusion of PCDH9 as the responsible gene for autosomal dominant auditory neuropathy (AUNA1). Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2009, 149A, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanske, A.; Ferreira, J.C.; Leonard, J.C.; Fuller, P.; Marion, R.W. Hirschsprung disease in an infant with a contiguous gene syndrome of chromosome 13. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 102, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoor, M.; Coussa, R.G.; Strampe, M.R.; Larson, S.A.; Russell, J.F. Xp11.3 microdeletion causing Norrie disease and X-linked Kabuki syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2023, 29, 101798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendtorff, N.D.; Karstensen, H.G.; Lodahl, M.; Tolmie, J.; McWilliam, C.; Bak, M.; Tommerup, N.; Nazaryan-Petersen, L.; Kunst, H.; Wong, M.; et al. Identification and analysis of deletion breakpoints in four Mohr-Tranebjærg syndrome (MTS) patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szaflarska, A.; Rutkowska-Zapała, M.; Gruca, A.; Szewczyk, K.; Bik-Multanowski, M.; Lenart, M.; Surman, M.; Kopyta, I.; Głuszkiewicz, E.; Machnikowska-Sokołowska, M.; et al. Neurodegenerative changes detected by neuroimaging in a patient with contiguous X-chromosome deletion syndrome encompassing BTK and TIMM8A genes. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018, 43, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Zhao, M.; Kanegane, H.; van Zelm, M.C.; Futatani, T.; Yamada, M.; Ariga, T.; Ochs, H.D.; Miyawaki, T.; Oh-ishi, T. Genetic analysis of contiguous X-chromosome deletion syndrome encompassing the BTK and TIMM8A genes. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 56, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, S.; Shaw, M.; Mignot, C.; Héron, D.; Bastaraud, S.C.; Walti, C.C.; Liebelt, J.; Elmslie, F.; Yap, P.; Hurst, J.; et al. Further delineation of BCAP31-linked intellectual disability: Description of 17 new families with LoF and missense variants. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 29, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welcome to the Hereditary Hearing Loss Homepage|Hereditary Hearing Loss Homepage. Available online: https://hereditaryhearingloss.org/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Marler, J.A.; Sitcovsky, J.L.; Mervis, C.B.; Kistler, D.J.; Wightman, F.L. Auditory function and hearing loss in children and adults with Williams syndrome: Cochlear impairment in individuals with otherwise normal hearing. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2010, 154C, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tackels-Horne, D.; Toburen, A.; Sangiorgi, E.; Gurrieri, F.; de Mollerat, X.; Fischetto, R.; Causio, F.; Clarkson, K.; Stevenson, R.E.; Schwartz, C.E. Split hand/split foot malformation with hearing loss: First report of families linked to the SHFM1 locus in 7q21. Clin. Genet. 2001, 59, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitsu, H.; Kurosawa, K.; Kawara, H.; Eguchi, M.; Mizuguchi, T.; Harada, N.; Kaname, T.; Kano, H.; Miyake, N.; Toda, T.; et al. Characterization of the complex 7q21.3 rearrangement in a patient with bilateral split-foot malformation and hearing loss. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2009, 149A, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Wees, J.; van Looij, M.A.J.; de Ruiter, M.M.; Elias, H.; van der Burg, H.; Liem, S.-S.; Kurek, D.; Engel, J.D.; Karis, A.; van Zanten, B.G.A.; et al. Hearing loss following Gata3 haploinsufficiency is caused by cochlear disorder. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 16, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugbjerg, P.; Everberg, G. A case of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome with conductive hearing loss. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1984, 73, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigoni, S.; Mauro, A.; Ferlini, A.; Corazzi, V.; Ciorba, A.; Aimoni, C. Cochlear malformation and sensorineural hearing loss in the Silver-Russell Syndrome. Minerva Pediatr. 2018, 70, 638–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballif, B.C.; Hornor, S.A.; Jenkins, E.; Madan-Khetarpal, S.; Surti, U.; Jackson, K.E.; Asamoah, A.; Brock, P.L.; Gowans, G.C.; Conway, R.L.; et al. Discovery of a previously unrecognized microdeletion syndrome of 16p11.2-p12.2. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 1071–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempel, M.; Rivera Brugués, N.; Wagenstaller, J.; Lederer, G.; Weitensteiner, A.; Seidel, H.; Meitinger, T.; Strom, T.M. Microdeletion syndrome 16p11.2-p12.2: Clinical and molecular characterization. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2009, 149A, 2106–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cicco, M.; Padoan, R.; Felisati, G.; Dilani, D.; Moretti, E.; Guerneri, S.; Selicorni, A. Otorhinolaringologic manifestation of Smith-Magenis syndrome. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2001, 59, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, N.; Ghosh, M.; Riazuddin, S.; Naz, S.; Khan, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Riazuddin, S.; Liang, Y.; Menon, P.S.; Smith, T.; et al. Novel mutations of MYO15A associated with profound deafness in consanguineous families and moderately severe hearing loss in a patient with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Hum. Genet. 2001, 109, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potocki, L.; Bi, W.; Treadwell-Deering, D.; Carvalho, C.M.B.; Eifert, A.; Friedman, E.M.; Glaze, D.; Krull, K.; Lee, J.A.; Lewis, R.A.; et al. Characterization of Potocki-Lupski syndrome (dup(17)(p11.2p11.2)) and delineation of a dosage-sensitive critical interval that can convey an autism phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verheij, E.; Derks, L.S.M.; Stegeman, I.; Thomeer, H.G.X.M. Prevalence of hearing loss and clinical otologic manifestations in patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: A literature review. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2017, 42, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussbaum, R.L.; Lesko, J.G.; Lewis, R.A.; Ledbetter, S.A.; Ledbetter, D.H. Isolation of anonymous DNA sequences from within a submicroscopic X chromosomal deletion in a patient with choroideremia, deafness, and mental retardation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 6521–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merry, D.E.; Lesko, J.G.; Sosnoski, D.M.; Lewis, R.A.; Lubinsky, M.; Trask, B.; van den Engh, G.; Collins, F.S.; Nussbaum, R.L. Choroideremia and deafness with stapes fixation: A contiguous gene deletion syndrome in Xq21. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1989, 45, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.; Yang, H.-M.; Niebuhr, E.; Rosenberg, T.; Page, D.C. Regional localization of polymorphic DNA loci on the proximal long arm of the X chromosome using deletions associated with choroideremia. Hum. Genet. 1988, 78, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piussan, C.; Hanauer, A.; Dahl, N.; Mathieu, M.; Kolski, C.; Biancalana, V.; Heyberger, S.; Strunski, V. X-linked progressive mixed deafness: A new microdeletion that involves a more proximal region in Xq21. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995, 56, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayazi, S. Choroideremia, Obesity, and Congenital Deafness. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1981, 92, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, S.V.; Robertson, M.E.; Fear, C.N.; Goodship, J.; Malcolm, S.; Jay, B.; Bobrow, M.; Pembrey, M.E. Prenatal diagnosis of X-linked choroideremia with mental retardation, associated with a cytologically detectable X-chromosome deletion. Hum. Genet. 1987, 75, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Lee, H.; Choi, J.; Kim, S.; Bok, J.; Kim, U. Clinical evaluation of DFN3 patients with deletions in the POU3F4 locus and detection of carrier female using MLPA. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, A.; Andersen, O.; Lundsteen, C.; Niebuhr, E.; Sardemann, H. Interstitial deletion in the “critical region” of the long arm of the X chromosome in a mentally retarded boy and his normal mother. Hum. Genet. 1983, 64, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poloschek, C.M.; Kloeckener-Gruissem, B.; Hansen, L.L.; Bach, M.; Berger, W. Syndromic choroideremia: Sublocalization of phenotypes associated with Martin-Probst deafness mental retardation syndrome. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 4096–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Jiang, N.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Yu, D. A maternally inherited 8.05 Mb Xq21 deletion associated with Choroideremia, deafness, and mental retardation syndrome in a male patient. Mol. Cytogenet. 2017, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gong, W.X.; Gong, R.Z.; Zhao, B. HRCT and MRI findings in X-linked non-syndromic deafness patients with a POU3F4 mutation. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 1756–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anger, G.J.; Crocker, S.; McKenzie, K.; Brown, K.K.; Morton, C.C.; Harrison, K.; MacKenzie, J.J. X-linked deafness-2 (DFNX2) phenotype associated with a paracentric inversion upstream of POU3F4. Am. J. Audiol. 2014, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choi, B.Y.; An, Y.-H.; Park, J.H.; Jang, J.H.; Chung, H.C.; Kim, A.-R.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, C.-S.; Oh, S.H.; Chang, S.O. Audiological and surgical evidence for the presence of a third window effect for the conductive hearing loss in DFNX2 deafness irrespective of types of mutations. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 270, 3057–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocak, E.; Duman, D.; Tekin, M. Genetic Causes of Inner Ear Anomalies: A Review from the Turkish Study Group for Inner Ear Anomalies. Balk. Med. J. 2019, 36, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defourny, J. Considering gene therapy to protect from X-linked deafness DFNX2 and associated neurodevelopmental disorders. Ibrain 2022, 8, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZNF711 Zinc Finger Protein 711 [Homo Sapiens (Human)]–Gene–NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?Db=gene&Cmd=DetailsSearch&Term=7552 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Wang, J.; Foroutan, A.; Richardson, E.; Skinner, S.A.; Reilly, J.; Kerkhof, J.; Curry, C.J.; Tarpey, P.S.; Robertson, S.P.; Maystadt, I.; et al. Clinical findings and a DNA methylation signature in kindreds with alterations in ZNF711. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG 2022, 30, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHM Curation Results for Dosage Sensitivity. Available online: https://search.clinicalgenome.org/kb/gene-dosage/HGNC:1940 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- McTaggart, K.E.; Tran, M.; Mah, D.Y.; Lai, S.W.; Nesslinger, N.J.; MacDonald, I.M. Mutational analysis of patients with the diagnosis of choroideremia. Hum. Mutat. 2002, 20, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Alcudia, R.; Garcia-Hoyos, M.; Lopez-Martinez, M.A.; Sanchez-Bolivar, N.; Zurita, O.; Gimenez, A.; Villaverde, C.; Rodrigues-Jacy da Silva, L.; Corton, M.; Perez-Carro, R.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of Choroideremia: From Genetic Characterization to Clinical Practice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Hurk, J.A.; van de Pol, D.J.; Wissinger, B.; van Driel, M.A.; Hoefsloot, L.H.; de Wijs, I.J.; van den Born, L.I.; Heckenlively, J.R.; Brunner, H.G.; Zrenner, E.; et al. Novel types of mutation in the choroideremia (CHM) gene: A full-length L1 insertion and an intronic mutation activating a cryptic exon. Hum. Genet. 2003, 113, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bione, S.; Rizzolio, F.; Sala, C.; Ricotti, R.; Goegan, M.; Manzini, M.C.; Battaglia, R.; Marozzi, A.; Vegetti, W.; Dalprà, L.; et al. Mutation analysis of two candidate genes for premature ovarian failure, DACH2 and POF1B. Hum. Reprod. 2004, 19, 2759–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, A.; Lee, H.; Zahed, L.; Choucair, M.; Muller, J.-M.; Nelson, S.F.; Salameh, W.; Vilain, E. Disruption of POF1B binding to nonmuscle actin filaments is associated with premature ovarian failure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, P.; Magnani, I.; Fuhrmann Conti, A.M.; Gelli, D.; Sala, C.; Toniolo, D.; Larizza, L. FISH characterization of the Xq21 breakpoint in a translocation carrier with premature ovarian failure. Clin. Genet. 1996, 50, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HGMD® Home Page. Available online: https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- De Kok, Y.J.M.; Van Der Maarel, S.M.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.; Huber, I.; Monaco, A.P.; Malcolm, S.; Pembrey, M.E.; Ropers, H.-H.; Cremers, F.P.M. Association between X-linked mixed deafness and mutations in the POU domain gene POU3F4. Science 1995, 267, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sennaroglu, L. Cochlear implantation in inner ear malformations—A review article. Cochlear Implants Int. 2010, 11, 4–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papsin, B.C. Cochlear implantation in children with anomalous cochleovestibular anatomy. Laryngoscope 2005, 115 Pt 2 (Suppl. 106), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, I.S.; Radziwon, A.; St Laurent, C.D.; MacDonald, I.M. Choroideremia. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 28, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla Elsayed, M.E.; Taylor, L.J.; Josan, A.S.; Fischer, M.D.; MacLaren, R.E. Choroideremia: The Endpoint Endgame. IJMS 2023, 24, 14354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, H.; Moosajee, M. Choroideremia: Molecular mechanisms and therapies. Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.N.; Islam, F.; Moore, A.T.; Michaelides, M. Clinical and Genetic Features of Choroideremia in Childhood. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambati, M.; Borrelli, E.; Sacconi, R.; Bandello, F.; Querques, G. Choroideremia: Update on Clinical Features and Emerging Treatments. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 13, 2225–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLuca, A.P.; Whitmore, S.S.; Tatro, N.J.; Andorf, J.L.; Faga, B.P.; Faga, L.A.; Colins, M.M.; Luse, M.A.; Fenner, B.J.; Stone, E.M.; et al. Using Goldmann Visual Field Volume to Track Disease Progression in Choroideremia. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2023, 3, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, A.B.; Kellner, U.; Cropp, E.; Preising, M.N.; MacDonald, I.M.; van den Hurk, J.A.; Cremers, F.P.; Foerster, M.H. Choroideremia: Variability of clinical and electrophysiological characteristics and first report of a negative electroretinogram. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 2066–2073.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, C.T.; Tomas, M.-B.; Sharp, A.J.; Mefford, H.C. The Genetics of Microdeletion and Microduplication Syndromes: An Update. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2014, 15, 215–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.T.; Adam, M.P.; Aradhya, S.; Biesecker, L.G.; Brothman, A.R.; Carter, N.P.; Church, D.M.; Crolla, J.A.; Eichler, E.E.; Epstein, C.J.; et al. Consensus statement: Chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 86, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonard, L.; Brotto, D.; Moreno-Pelayo, M.A.; Del Castillo, I.; Kremer, H.; Pennings, R.; Caria, H.; Fialho, G.; Boudewyns, A.; Van Camp, G.; et al. Genetic Evaluation of Prelingual Hearing Impairment: Recommendations of an European Network for Genetic Hearing Impairment. Audiol. Res. 2023, 13, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genetic Hearing Loss Overview–GeneReviews®–NCBI Bookshelf. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1434/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Downie, L.; Halliday, J.; Lewis, S.; Lunke, S.; Lynch, E.; Martyn, M.; Gaff, C.; Jarmolowicz, A.; Amor, D.J. Exome sequencing in newborns with congenital deafness as a model for genomic newborn screening: The Baby Beyond Hearing project. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wapner, R.J.; Martin, C.L.; Levy, B.; Ballif, B.C.; Eng, C.M.; Zachary, J.M.; Savage, M.; Platt, L.D.; Saltzman, D.; Grobman, W.A.; et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2175–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).