Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Patients with neuropsychiatric and metabolic disorders exhibit cognitive impairment or social deficits, which are associated with gut dysbiosis and aberrant gut microbiota (GM) profiles via epigenetic mechanisms.

- Gut-balancing therapies may be considered promising approaches to manage or treat cognitive impairment or social deficits by normalizing epigenetic aberrations.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The bidirectional communication network linking the gut and the brain, referred to as the gut–brain–microbiota axis, plays a pivotal role in the progression of cognitive impairments and social dysfunction.

- Gut microbiota–targeted interventions—such as prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation—may ameliorate cognitive impairments and impaired social interactions by normalizing GM profiles and enhancing key epigenetically active metabolites.

Abstract

Oxidative stress (OS) reflects a pathologic imbalance between excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and insufficient antioxidant defenses. Growing evidence indicates that a healthy gut microbiota (GM) is essential for regulating redox homeostasis, whereas gut dysbiosis contributes to elevated ROS levels and oxidative damage in DNA, lipids, and proteins. This redox disequilibrium initiates a cascade of cellular disturbances—including synaptic dysfunction, altered receptor activity, excitotoxicity, mitochondrial disruption, and chronic neuroinflammation—that can, in turn, impair cognitive and social functioning in metabolic and neuropsychiatric disorders via epigenetic mechanisms. In this review, we synthesize current knowledge on (1) how OS contributes to cognitive and social deficits through epigenetic dysregulation; (2) the role of disrupted one-carbon metabolism in epigenetically mediated neurological dysfunction; and (3) mechanistic links between leaky gut, OS, altered GM composition, and GM-derived epigenetic metabolites. We also highlight emerging microbiota-based therapeutic strategies capable of mitigating epigenetic abnormalities and improving cognitive and social outcomes. Understanding the OS–microbiota–epigenetic interplay may uncover new targetable pathways for therapies aimed at restoring brain and behavioral health.

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress (OS) is defined as an imbalance between the reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and antioxidant levels in cells, owing to disruptions in the function of cellular organelles such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum [1,2]. ROS are produced as secondary by-products of the leaky electron transport chain (ETC) at complexes I and III in mitochondria [3]. OS can contribute to the development of different disorders by inducing damage to lipids, proteins and DNA in cells [4]. Owing to its high energy requirements, the brain consumes high concentrations of oxygen and is highly sensitive to OS [5]. OS causes disruptions in the redox signaling pathway and leads to microglial dysfunction, contributing to cognitive and social deficits during neuropsychiatric disorders (NPDs) [6]. For example, in autistic mice, impaired social interaction is linked to elevated malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and reduced activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and the content of GSH in hippocampus and amygdala tissues [7]. The detrimental effects of OS on the function of neuronal cells can be associated with epigenetic aberrations. For example, OS causes an imbalance between DNA methylation and demethylation and between histone acetylation and deacetylation, which is relevant to the activation of transcription factors, and, in turn, gives rise to the Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-related gene transcription in Aβ overproduction [8]. Yang et al. reported that elevated H4K12la is directly capable of activating the FOXO1 signaling pathway, increasing OS, and contributing to diabetes-induced cognitive dysfunction phenotypes [9]. The human gut microbiota (GM) is an incredibly dynamic and intricate ecological system made up of trillions of microorganisms specialized to the host [10]. This community contains bacteria, viruses, fungi, and a broad spectrum of other microbial and eukaryotic organisms. Among these, bacteria dominate, accounting for approximately 99% of all microbes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Major research efforts, such as MetaHit and the Human Microbiome Project, have cataloged over 2000 microbial species present in the human GI tract [11]. The composition of the healthy GM is mainly composed of four predominant bacterial phyla, including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria, which together constitute almost 98% of all microorganisms [12]. This diverse microbial community plays a key role in numerous events, including the development and fine-tuning of the immune system, maintaining immune balance, orchestration of effective immune responses, defense against pathogens, promoting intestinal barrier integrity, and regulation of metabolic processes [13,14,15,16]. Ensuring a stable and resilient GM is crucial, as it improves the community’s capacity to restore balance following derangements caused by factors like unhealthy diets, excessive consumption of antibiotics or other medications, infections, and environmental stressors [17,18,19,20].

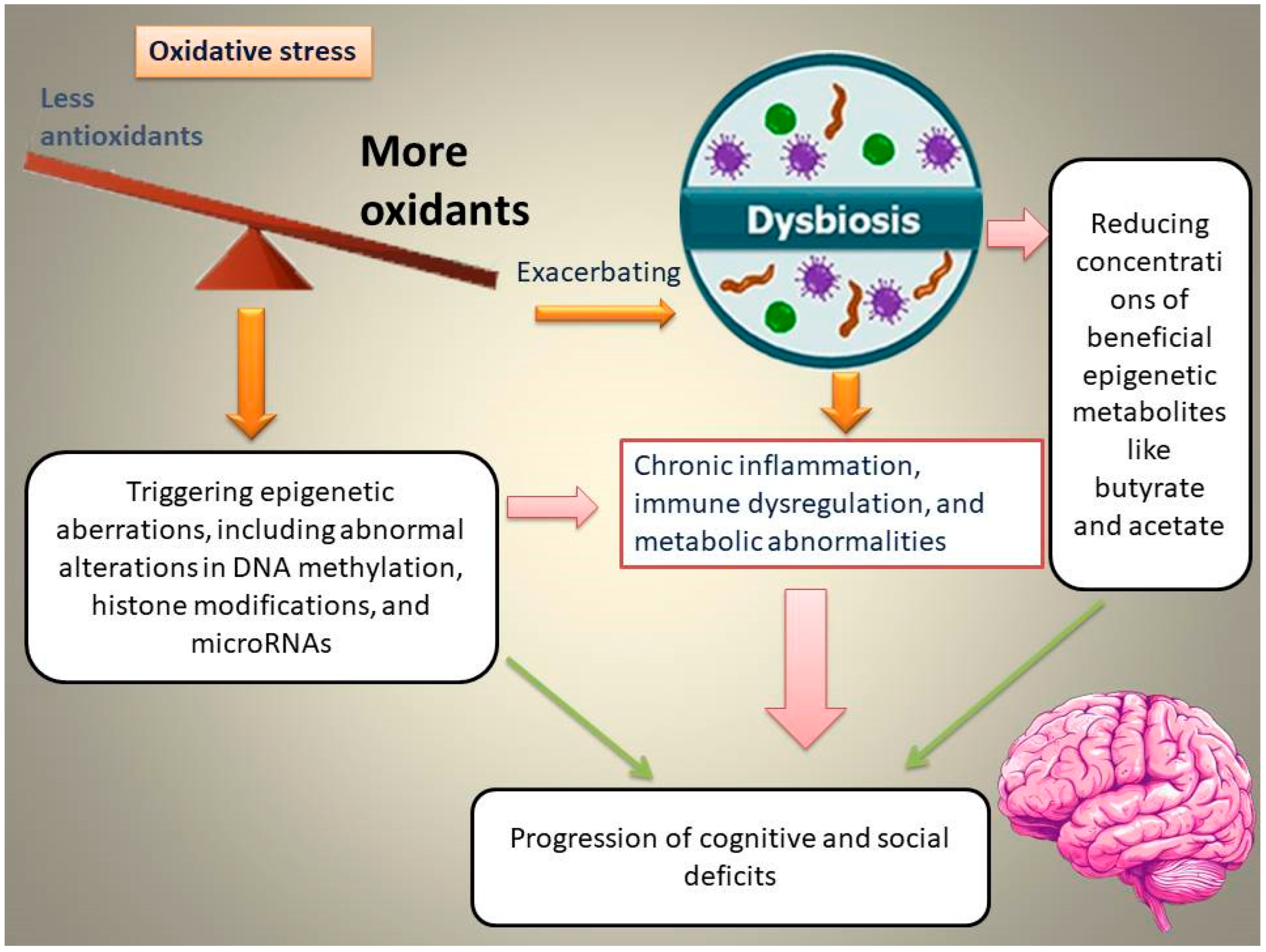

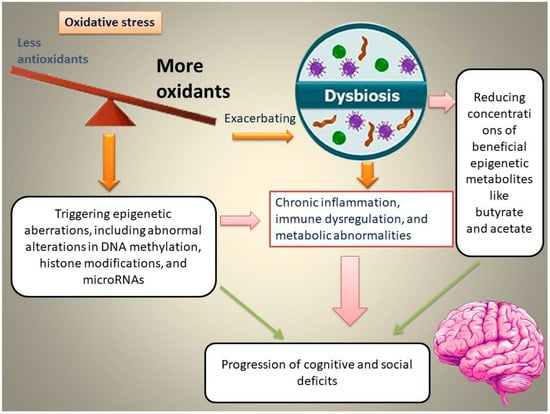

The intestine has attracted increasing attention from the scientific community owing to its crucial role in triggering emotional dysfunction, cognitive deficits, and neuropsychiatric conditions. Interactions between the intestine and the brain in the initiation of cognitive and social deficits are associated with OS [21]. Elevated OS in the gut is associated with gut dysbiosis and epigenetic abnormalities, which, in turn, aggravate chronic inflammation, immune and metabolic dysregulation, and subsequently, the progression of cognitive and social deficits (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the proposed pathway through which oxidative stress (OS) induces gut dysbiosis, alters epigenetic programming, and promotes the emergence and progression of cognitive and social deficits.

For example, Enterococcus dysbiosis is linked to elevated OS in the gut, aggravating inflammatory responses, damaging the intestinal epithelium, and subsequently causing vitamin D deficiency-associated memory impairments [22]. The overgrowth of Enterococcus species is accompanied by a reduction in the levels of butyrate-producing bacteria, such as Roseburia spp. and Clostridium species, which synthesize butyrate as an epigenetic metabolite and a precursor of vitamin D3 [22]. The intestine of valproic acid (VPA)-exposed mice is underdeveloped, with excessive OS, which affects the colonization of gut microbiota (GM). It has been found that SOD supplementation during early life contributes to improved social interactions and reduced autistic behaviors by restoring autism-related GM [21]. This review examines the OS–GM–epigenetic axis as a convergent mechanism underlying cognitive and social dysfunction. We focus on (1) epigenetic consequences of OS; (2) one-carbon metabolism and homocysteine-related redox/epigenetic dysfunction; (3) interactions between leaky gut; dysbiosis; and epigenetic metabolites; and (4) microbiota-targeted therapies designed to reverse epigenetic damage and improve neurobehavioral outcomes.

2. Methods

Our primary objective in this review is to examine the crosstalk among OS, the GM, and epigenetic mechanisms, and to evaluate how these interactions influence cognition and social behavior in NPDs. To gather relevant evidence, we conducted independent searches in four databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Embase, using the keywords “oxidative stress” or “gut microbiota” combined with “DNA methylation,” “histone modification,” or “microRNA,” along with the names of specific disorders, including cognitive impairment and social deficits. After excluding review articles and case reports, we identified more than 135 studies published from 2001 to November 2025 for further evaluation. Following a screening of the abstracts, eligible studies were examined in detail, and the extracted information is summarized in the narrative sections of this review.

3. Role of Oxidative Stress in Epigenetic Dysregulation and Cognitive/Social Deficits

Current research suggests that complex interactions among genetic and epigenetic factors, modulated by environmental influences, affect human vulnerability to stressors and drive the progression of cognitive and social impairments [23,24,25,26,27]. Pathological processes such as OS and inflammation can influence cognitive function and sociability through epigenetic mechanisms. In adolescents, cognitive function is shaped by the coordinated actions of epigenetic modifications, microRNA (miRNA) expression, and intracellular signaling pathways. For instance, DNA hypomethylation and elevated NF-κB activity play a critical role in determining the direction of synaptic plasticity. Moreover, the synergistic interaction of specific miRNA families, particularly miR-30 and miR-204, with the SIRT1 protein contributes to the fine-tuning of these neuroplastic processes [28]. This section discusses how OS affects cognitive/social-related genes (such as BDNF, SIRT1, NRF2, etc.) through specific epigenetic modifications.

3.1. DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is a type of epigenetic modification that affects gene expression by altering chromatin structure [29,30]. It is characterized by the addition of a methyl group (–CH3) to the 5-carbon position of cytosine residues, typically within CpG dinucleotides, without changing the underlying DNA sequence [30]. Pro-oxidant environmental stressors may accelerate genetic predisposition to autism and social deficits. Transmethylation defects and OS play a powerful role in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) pathogenesis [31]. For example, fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can induce pronounced redox imbalance, reduce intracellular levels of methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine, and lead to global DNA hypomethylation as well as gene-specific promoter DNA hypo- or hypermethylation, resulting in abnormal mRNA expression of autism-related candidate genes [32]. Derangements in antioxidant defenses and methylation capacity (e.g., DNA hypomethylation) have also been found in autism, which in turn increases cellular damage by influencing gene expression [33]. In ASD subjects, hypermethylation of PGC-1α at eight CpG sites in the promoter region of the gene, together with elevated mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number, has been associated with levels of urinary organic acids linked to mitochondrial impairment, OS, and altered neuroendocrine activity [34]. Similarly, Kulkarni et al. reported that repeated mild traumatic brain injury–induced persistent cognitive deficits may be associated with decreased mitofusin-2 (Mfn2) expression through DNA hypermethylation at the Mfn2 promoter, subsequently elevating cellular and mitochondrial ROS levels [35]. Boruch et al. identified 74 nuclear genes linked to mitochondrial glucose metabolism, fatty acid metabolism and OS pathways that exhibited altered methylation in subjects with mild cognitive impairment versus cognitively unimpaired participants. Their results showed that pronounced hypermethylation of nuclear genes involved in mitochondrial pathways may be considered a hallmark of the transition from cognitively unimpaired participants to mild cognitive impairment, whereas substantial hypomethylation at these loci may be an indicator of progression from mild cognitive impairment to AD [36]. Table 1 summarizes additional studies. In sum, OS alters DNA methylation patterns that contribute to neurobiological dysfunction and thereby develop cognitive and social impairments across neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions.

3.2. Histone Modifications

Histone modifications are essential epigenetic regulatory mechanisms that affect a wide range of pathophysiological processes in the human body [37]. These modifications, including methylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination, are capable of altering histones and thereby regulating gene expression [38]. In addition to DNA methylation, OS plays a powerful role in the progression of neurotoxicity and in cognitive and social deficits through changes in histone modifications [39,40]. For example, short-term OS increases the activity of Class I/II HDACs, which gives rise to a reduction in global histone acetylation [41]. Hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cognitive impairment can be caused by reduced histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation, downregulation of target genes (Gria1, Gria3, Grin2a, Grin2b, Slc1a1, Slc24a2, Ptk2b, and Src), and consequent derangements in synaptic plasticity [42].

Maternal diabetes–induced autism-like behaviors and social deficits in offspring are attributed to SOD2 suppression owing to OS-mediated histone methylation and the subsequent dissociation of early growth response 1 (Egr1) from the SOD2 promoter [43]. Liu et al. found that manganese (Mn)-induced oxidative damage and cognitive impairment in the rat striatum and in SH-SY5Y cells are linked to reduced expression of the histone acetyltransferase KAT2A and decreased H3K36ac levels in the promoter regions of antioxidant genes, including SOD2, PRDX3, and TXN2 [44]. Chen et al. also found that Mn-induced neurotoxicity in rats is associated with oxidative damage in the hippocampus by reducing the expression of antioxidant genes SOD2 and GSTO1 via modulation of H3K18 acetylation (H3K18ac) [45]. Their findings demonstrated that increases in H3K18ac levels in the hippocampus and peripheral blood, and hence, reductions in H3K18ac enrichment at SOD2 and GSTO1 promoters, indicate histone acetylation changes in Mn-induced neurotoxicity. Table 1 summarizes additional studies. Overall, OS is capable of causing abnormalities in histone modifications, which in turn alter gene expression and synaptic function, and hence lead to cognitive and social impairments in neurodevelopmental and neurotoxic conditions.

3.3. miRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous non-coding RNAs, approximately 21 nucleotides in length, that function as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression [46,47]. miRNAs can either restrain or promote OS during health and disease, thereby influencing cognitive performance and social behavior [48,49]. Previous studies have shown that early exposure to OS, before and during prenatal neuronal differentiation, may contribute to the development of NPDs in adulthood through disrupting the expression of miRNAs that regulate genes critical for neurodevelopment [50]. Certain miRNAs have demonstrated the ability to target redox enzymes and hence may be excellent candidates for identifying causative factors underlying redox alterations in BD and other NPDs [51]. Owing to their capacity to interact with multiple target mRNAs within regulatory networks, small non-coding miRNAs play a pivotal role in modulating physiological processes such as behavior, OS, and neuroinflammation through gene expression regulation [49,52]. For example, Han et al. reported that cognitive impairment in diabetic rats was linked to overexpression of miRNA-23b-3p, which initiated OS, suppressed SIRT1 and Nrf2 expression in neurons, and reduced neuronal survival [53]. Similarly, Zhan-qiang et al. reported that miR-146a exacerbates cognitive impairment and AD-like pathology by triggering ROS production and OS via MAPK signaling [54]. In another study, Zhang et al. observed that PM2.5-exposed offspring mice exhibited elevated 8-OHG levels in microglial and Purkinje cell miRNAs at 6 weeks of age, accompanied by increased inflammatory markers, enhanced OS, and impaired cognitive performance [55]. Qu et al. demonstrated that miR-153 contributes to chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH)-related cognitive impairment in male rats by negatively regulating KPNA5 expression in the basal forebrain, thereby suppressing NRF2 nuclear translocation and exacerbating OS-induced neuronal damage [56]. Moreover, participants with mild cognitive impairment exhibited elevated levels of miR-124a and miR-483-5p and decreased levels of miR-142-3p and miR-125b, which correlated with OS markers, including MDA, CAT, and SOD [57]. Table 1 summarizes additional studies. In general, miRNAs have demonstrated the ability to modulate OS and gene expression, which in turn affect cognitive function and social behavior, indicating their potential as key regulators and potential biomarkers in NPDs.

Table 1.

Different epigenetic alterations affecting cognitive/social-related genes and pathological mechanisms.

Table 1.

Different epigenetic alterations affecting cognitive/social-related genes and pathological mechanisms.

| Epigenetic Alteration | Target Genes/Key Pathological Mechanisms | Type of Study/Sample | Effects on Cognition or Sociability | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA methylation | BDNF/oxidative stress (OS) | Rats undergoing chronic unpredicted mild stress (CUMS)/brain | Homocysteine (Hcy)-induced DNA hypermethylation in the BDNF promoter reduced BDNF and caused cognitive deficits | [58] |

| DNA methylation | iNOS, COX2, NFkB and SOD2/neuroinflammation and OS | STZ-induced diabetic mice/the hippocampus region | Global DNA Hypermethylation was associated with diabetes-induced cognitive impairment | [59] |

| DNA methylation | Syp and Shank2 genes | A rat model of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury/the hippocampus region | DNA hypomethylation enhances learning and memory recovery | [60] |

| Histone acetylation | Gria1, Gria3, Grin2a, Grin2b, Slc1a1, Slc24a2, Ptk2b, and Src/neuroinflammation and OS | Hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cognitive impairment model by feeding mice a high-methionine diet/the hippocampus and cortex | A considerable reduction in histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation/aberrant expression of long-term potentiation-related genes regulated by histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation is a key driver of hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cognitive impairment | [42] |

| Histone acetylation | HDAC2 and GCN5/OS and inflammation | Social isolation stress mice/hippocampus region | Association between increased HDAC2 and GCN5 expression and social behavior dysfunction | [61] |

| Histone lactylation | FOXO1 and PGC-1α/OS | T2DM mice and high glucose-treated microglia/brain | Increased H4K12la directly activates the FOXO1 signaling pathway, elevating OS and contributing to diabetes-related cognitive impairment | [9] |

| MiRNAs (miR-124a, miR-483-5p, miR-142-3p, and miR-125b) | NO, MDA, DPP4, BDNF, SIRT-1, CAT, SOD, Bcl-2, Bax, and caspase-3/OS, inflammation, and apoptosis | Healthy normal (n = 80) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients (n = 70)/serum | The levels of miR-124a and miR-483-5p considerably elevated and miR-142-3p and miR-125b markedly decreased in the serum of MCI patients/The expressed miRNAs correlated positively with NO, MDA, DPP4 activity, BDNF, and SIRT-1, and negatively with the levels of CAT, SOD, Bcl-2, Bax, and caspase-3 genes | [57] |

| MiRNA-21 | GSK/OS | Diabetic rats/the hippocampus region | Reduced expression of miRNA-21 was associated with derangements in brain insulin signaling and cognitive dysfunction | [62] |

| MiR-5699 | GRIN2B/OS | 209 unrelated patients with SCZ/blood samples | Association between disrupted MiR-5699 and cognition in patients with SCZ via OS | [63] |

| MiR203-5p | Glutamatergic and GABAergic genes/possibly OS | Stress-exposed C-Glud1+/− mice as a model of SCZ/medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) | Chronic glutamate abnormalities interact with acute stress to induce cognitive deficits by increasing miR203-5p expression | [64] |

4. One-Carbon Metabolism, Oxidative Stress, and Cognitive/Social Dysfunction

B vitamins in the one-carbon metabolism pathway (folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12) play an important role in the control of gene expression by modulating DNA methylation [65,66]. Their deficiency may accelerate cognitive impairment via elevated homocysteine (Hcy) levels and consequently oxidative damage [67,68]. A growing body of evidence has shown that Hcy is a potent neurotoxin and one of the main drivers of OS in the brain, causing cognitive and memory impairment by altering methylation patterns [69,70,71,72]. In the body, methionine is converted into Hcy. Increased Hcy can raise S-adenosylmethionine levels, which in turn suppress the remethylation of Hcy, leading to its further buildup [73]. This metabolic disruption initiates a cascade of OS reactions that interfere with the normal production and turnover of neurotransmitters. Vitamins B6, B12, and folate serve as key cofactors in methionine metabolism, and folate-dependent cycles play a crucial role in regulating Hcy concentrations [74]. It seems that B-vitamin deficiency and elevation of Hcy may interplay with DNA methylation of oxidative-related genes and contribute to aggravating cognitive dysfunction. For example, An et al. found that reduced serum levels of B vitamins may contribute to cognitive dysfunction by influencing methylation levels of specific redox-related genes [75]. Their findings demonstrated that there are remarkable correlations between hypermethylated sites in redox-related genes, including NUDT15 and TXNRD1, and serum levels of folate, Hcy, and oxidative biomarkers [75]. Zhang et al. reported that elevation of hippocampal and serum levels of Hcy could increase mitochondrial impairment, redox imbalance, and hence cognitive damage in rats exposed to early-life stress by escalating METTL4 expression and augmenting N6-methyldeoxyadenosine (6mA) modification in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [76]. In addition to DNA methylation, the detrimental effects of Hcy on cognitive function can also be mediated through alterations in histone modifications. In a study conducted by Chai et al., increased levels of the permissive histone mark trimethyl histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and its methyltransferase KMT2B in HHcy rats were linked to disruptions of synaptic plasticity and cognitive function [77]. The authors found that H3K4 trimethylation may mediate HHcy-induced degeneration of neuronal cells by inhibiting histone acetylation through ANP32A [77]. Interestingly, increased serum Hcy levels are negatively associated with cognitive function, and this relationship may be linked to alterations in the composition of the intestinal microbial community. For example, Xu et al. reported that elevated serum levels of Hcy in patients with MDD are negatively correlated with cognitive performance and with the abundance of certain genera, including Alistipes, Ruminococcae, Tenericides, and Porphyromonas [78]. Taken together, B-vitamin deficiency and increased levels of Hcy elevate OS and epigenetic aberrations, including abnormal changes in DNA and histone modifications, which lead to cognitive impairment and neuronal dysfunction.

5. Interactions Between Oxidative Stress, Leaky Gut, and Gut Microbiota via Epigenetic Mechanisms

Leaky gut is a condition characterized by elevated intestinal permeability, which allows injurious microbes, endotoxins, and hazardous substances to enter the bloodstream and induce OS and inflammation in various body organs, particularly the brain [79,80]. Leaky gut and microbial changes are linked to the severity of psychological symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive and social deficits [81,82]. There is a bidirectional and cyclical association between OS and a leaky gut [83]. Excessive production of ROS disrupts the gut barrier, increasing permeability and the growth and activity of harmful bacteria. Such derangements then aggravate OS by decreasing concentrations of beneficial microbial metabolites like butyrate and elevating inflammation, which in turn accelerates the development of different diseases, especially NPDs [84]. A leaky gut disrupts gene networks in the brain relevant to immune activation, OS, and lipid oxidation—such as Alox5, Lcn2, Mmp8, Nfe2l2, Nrros, and Cdkn1a—as well as myelination in mice with colitis [85]. Qaisar et al. reported a mechanistic link between elevated intestinal permeability, higher levels of OS and inflammatory markers, and postural dysfunction, an indicator of cognitive decline, in AD subjects [86]. Their results also indicated an inverse relationship between plasma zonulin and cognitive decline in AD subjects [86]. Low sociability in alcohol-dependent patients is associated with reduced levels of butyrate-producing bacteria such as F. prausnitzii and elevated intestinal permeability [87]. This can be attributed to a noticeable reduction in butyrate production as an epigenetic modifier. Reduced concentrations of butyrate not only increase OS but also disrupt intestinal barrier integrity due to the critical role of this epigenetic metabolite in promoting the expression and redistribution of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin, as well as tight junction assembly [88].

In a study by Fan et al., individuals with mild cognitive impairment exhibited reduced abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, including Ruminococcus, Butyricimonas, and Oxalobacter, and increased abundance of pathogenic bacteria, including Negativicutes, Flavobacteriales, Gemellaceae, and Saccharimonadaceae, which were associated with inflammation and OS [89]. Differential genera of GM involved in the progression of cognitive and social deficits are linked to pathological processes, particularly inflammation and OS. For example, Zhong et al. showed that ASD patients exhibited reduced mRNA levels of superoxide dismutase 2 and RAR-related orphan receptor α, elevated H3K9me2 modifications at the superoxide dismutase 2 promoter, increased amounts of 8-oxo-dG in oral epithelial cells, and a decreased reduced glutathione/oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) ratio in saliva, which were associated with increased OS and altered oral microbiota [90]. More studies on the association of differential genera of GM with cognitive and social deficits and related pathological processes, especially OS, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Linking between differential genera of GM with cognitive and social deficits and related pathological processes.

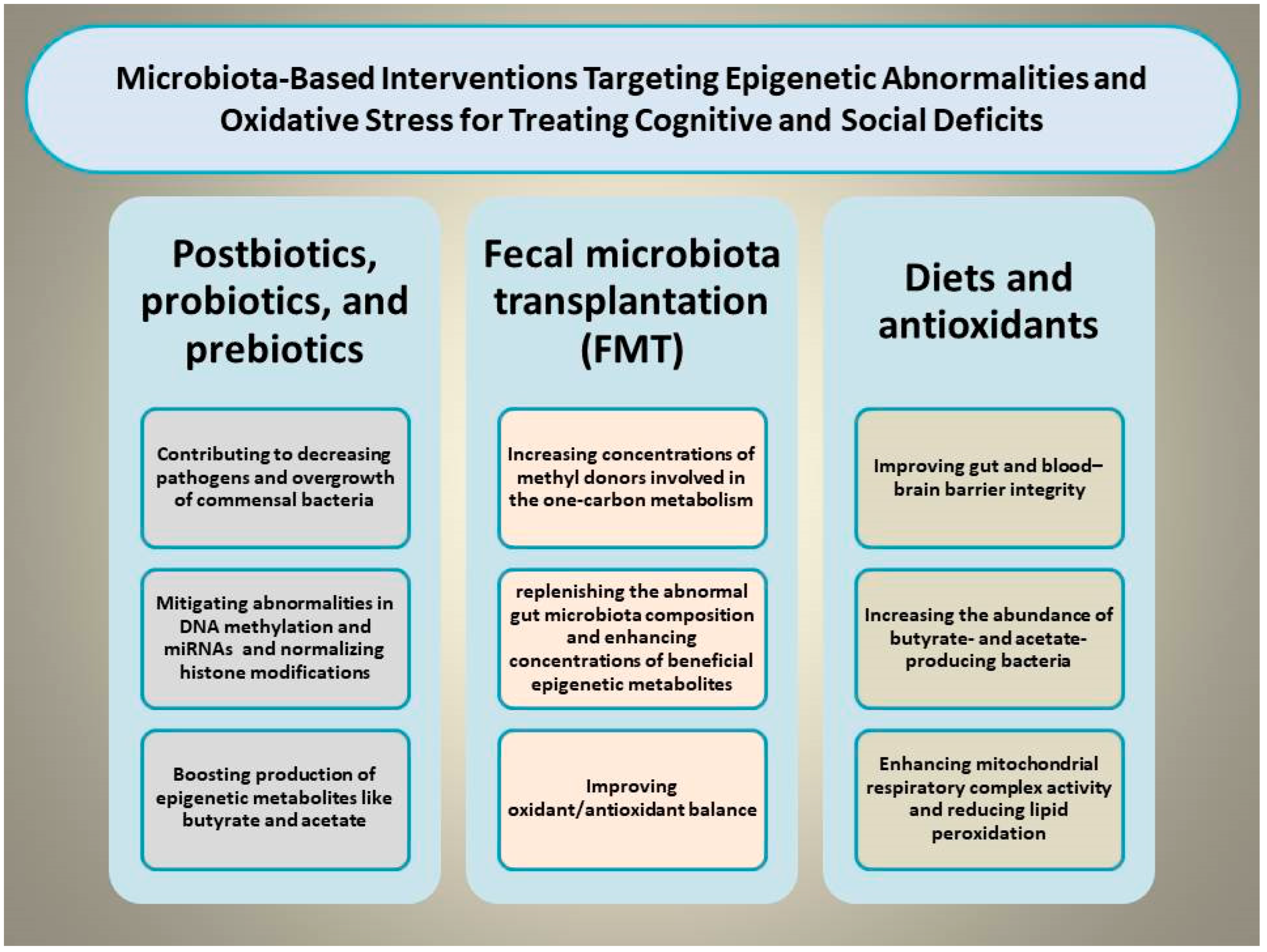

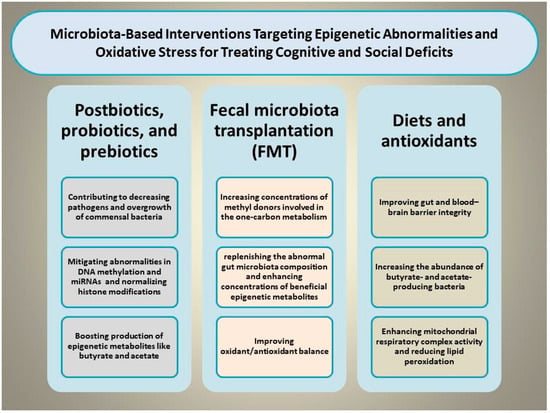

6. Microbiota-Based Interventions Targeting Epigenetic Abnormalities

Certain dietary and microbiota-based interventions have been found to palliate cognitive and social deficits by modulating the gut–brain axis and OS through mitigating epigenetic abnormalities [99]. For example, supplementing diverse nutraceutical compounds such as docosahexaenoic acid, vitamin D3, and probiotics exerts benefits in coping with aluminum-induced cognitive impairment by reshaping GM composition, diminishing MDA concentrations, enhancing SOD activity, and reducing glial activation [100]. This section focuses on various types of dietary and microbiota-based interventions capable of simultaneously targeting OS and epigenetic shifts to rescue cognitive and social deficits (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the proposed mechanisms through which microbiota-based interventions, including prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation, may alleviate cognitive and social deficits by simultaneously normalizing epigenetic aberrations and mitigating oxidative stress.

6.1. Postbiotics (SCFAs and Related Metabolites)

Postbiotics are metabiotics, biogenics, or epigenetic metabolites that are released by live bacteria or following bacterial lysis and provide health benefits [13,101,102]. For example, higher intake of gut microbiota-derived butyrate in people aged ≥60 years has been linked to better cognitive performance [103]. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites such as butyrate and acetate have antioxidant properties and can act as inhibitors of histone deacetylase activity [104,105,106]. In addition to altering histone modifications, they can also exert their beneficial effects by mitigating abnormalities in DNA methylation and miRNAs [107,108]. Gut microbiota-derived butyrate has been found to be a promising agent in affective disorders characterized by aberrant serotonergic activity or neuroinflammation owing to its ability to suppress OS-induced disruptions of tryptophan transport [109]. Butyrate has also been shown to improve mitochondrial function (oxidative phosphorylation and β-oxidation) during OS in cell lines from boys with autism and, therefore, may be considered a promising therapeutic agent to rescue impaired social interactions by mitigating epigenetic aberrations [110]. Moreover, the neuroprotective effects of sodium butyrate may be associated with reducing excessive ROS production via NOX2 suppression and SOD1 up-regulation through the p21/NRF2 pathway [111]. Wang et al. found that sodium butyrate could prevent Aβ25–35-induced cognitive impairments in mice by improving astroglial mitochondrial function, promoting astrocyte differentiation toward the A2 neuroprotective subtype, and enhancing the lactate shuttle between astrocytes and neurons [112]. In a study by Lu et al., the benefits of sodium butyrate in the treatment of diabetic cognitive impairments in mice were associated with improving mitochondrial damage, biogenesis, and dynamics, and up-regulating phosphorylated AMPK and PGC-1α [113]. Acetate is another epigenetic metabolite produced by gut bacteria that can exert protective effects against sleep-induced metabolic and cognitive impairments, possibly through suppressing OS [114]. Mechanistically, acetate is capable of binding and activating pyruvate carboxylase, which in turn contributes to the restoration of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle [114]. Both acetate and butyrate promote β-cell metabolism and mitochondrial respiration under OS conditions [115].

Wen et al. found that acetate could rescue perioperative neurocognitive deficits in aged mice by suppressing the expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6), OS markers (NADPH oxidase 2, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and ROS), and signaling molecules (nuclear factor kappa B and mitogen-activated protein kinase) in the hippocampus [116]. Moreover, acetate is capable of reversing social deficits by altering transcriptional regulation and improving OS in different regions of the brain [117]. Mechanistically, acetate may ameliorate impairments in social interactions by reducing histone deacetylase (HDAC2) gene expression, suppressing neuroinflammation by decreasing the density of Iba1+ cells and IL-1β gene expression in the hippocampus, and increasing levels of serum β-hydroxybutyrate as an antioxidant agent [118]. In conclusion, postbiotics, particularly gut microbiota-derived metabolites such as butyrate and acetate, demonstrate considerable neuroprotective and metabolic benefits, including improving antioxidant defense, epigenetic modulation, and promoting mitochondrial function.

Although postbiotics exhibit promising neuroprotective and metabolic effects, their therapeutic application may encounter several limitations. First, the high variability in the bioavailability and stability of postbiotics in vivo and poor delivery to target tissues after oral administration may diminish their effectiveness at physiologically relevant concentrations. Second, a large portion of existing findings are based on animal or in vitro studies, and human clinical evidence is still limited, making it difficult to translate their efficacy to diverse groups or identify optimal dosing. Third, the environment-dependent effects of postbiotics, shaped by individual differences in GM composition, age, metabolic health, and genetics, constrain their generalizability across populations. Moreover, high systemic levels of SCFAs could have off-target or adverse effects, like abnormal changes in immune or metabolic pathways in ways that are not yet fully understood. Ultimately, the field needs standardized approaches for postbiotic characterization, delivery, and safety evaluation to accelerate translation into clinically robust therapies.

6.2. Probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms capable of restoring beneficial bacteria and improving various diseases when consumed at appropriate concentrations [119,120]. Probiotics, including butyrate- and acetate-producing bacteria, can improve cognitive and social deficits by suppressing OS, inflammation, and apoptotic cell death via mitigating epigenetic aberrations, since butyrate and acetate act as epigenetic modifiers [119,121,122]. Wang et al. found that Lactobacillus johnsonii BS15 (L. johnsonii BS15), a lactic acid-producing probiotic, not only improved memory-related functional proteins associated with synaptic plasticity but also elevated neurotransmitter levels and mitigated restraint stress-induced OS and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in the hippocampus by increasing mRNA levels of tight junction proteins and reducing levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines in the intestine [123]. The psychoactive effects of L. johnsonii BS15 may be attributed to regulation of epigenetics, as lactic acid can serve as a substrate for the biochemical synthesis of butyric acid, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase activity [124]. Cheng et al. demonstrated that Lactobacillus paracasei PS23 ameliorated cognitive deficits in D-galactose-induced aging mice by increasing serotonin concentrations (5-HT) and up-regulating genes involved in neuroplasticity, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant responses, which was associated with elevated concentrations of SCFAs such as acetic acid and butyric acid in cecal contents [125]. Wu et al. reported that treatment with human Lactobacillaceae could attenuate cognitive decline in APP/PS1 mice by elevating GSH-PX activity, reducing IL-6 and MDA expression in the brain, and simultaneously increasing levels of beneficial bacteria involved in producing epigenetic metabolites while restraining harmful bacteria in the intestine [126]. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 improved high-fat diet-induced anxiety-like behavior and social withdrawal in male mice by inhibiting hippocampal OS, systemic inflammation, and dysbiosis, and enhancing intestinal barrier function via up-regulation of intestinal tight junctions (ZO-1 and Claudin1) [127].

In a study by Wang et al., treatment of a rat model of ASD induced by prenatal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection using L. reuteri or LGG for three weeks post-birth rescued social deficits and anxiety-like behaviors by elevating butyric acid levels, reducing propionic acid levels, improving colonic barrier integrity via up-regulation of tight junction proteins (ZO-1, Occludin, and Claudin4), mitigating HPA axis overactivation, and suppressing OS in the colon [128]. Benefits of probiotics may be associated with the regulation of miRNAs that mediate the impact of gut microbial dysbiosis on brain structure and function. As an interesting example, Chen et al. reported that daily restraint stress for 4 weeks in mice caused gut microbial dysbiosis and cognitive dysfunction, which were linked to a decrease in hippocampal miR-124 levels. Their findings demonstrated that different probiotic mixtures considerably alleviated chronic stress–induced alterations in hippocampal miR-124 levels and cognitive dysfunction [129]. In a study conducted by Mao et al., administration of probiotics increased miR-146a expression, leading to inhibition of the BTG2/Bax signaling axis, reduced neuronal apoptosis, and attenuation of OS in postoperative cognitive dysfunction mice, indicating that miR-146a-mediated suppression of BTG2/Bax contributes to the protective role of probiotic treatment against postoperative cognitive dysfunction in mice [130].

A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial by Akbari et al. demonstrated that treatment of AD patients with probiotic milk containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Lactobacillus fermentum for 12 weeks promoted cognitive function by reducing MDA content [131].

Similarly, Tamtaji et al. showed that probiotics, including L. acidophilus, B. bifidum, and B. longum combined with selenium for 12 weeks, improved cognitive performance and some metabolic profiles by elevating total antioxidant capacity [132]. In a double-blind, randomized, active-controlled trial, Hsu et al. found that multi-strain probiotics, including Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis BLI-02, B. breve Bv-889, B. animalis subsp. lactis CP-9, B. bifidum VDD088, and Lactobacillus plantarum PL-02, administered for 12 weeks, improved cognitive function by elevating serum BDNF, decreasing IL-1β, and increasing SOD activity [133]. Collectively, probiotics, particularly SCFA-producing strains like Lactobacillus and Bacillus, may enhance cognitive performance and social behaviors by attenuating OS, inflammation, and apoptosis, often through epigenetic modulation. Animal and human studies have shown benefits like increased neurotransmitter and epigenetic metabolite levels, enhanced intestinal barrier function, and better cognitive function. Despite these promising effects, further large-scale clinical studies are needed to optimize strain selection, dosing, and treatment protocols for therapeutic use.

6.3. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a medical procedure in which a small stool sample from a donor is transferred to a recipient to directly alter GM composition and induce therapeutic benefits [134,135,136,137]. Human-derived FMT alleviated social deficits in BTBR mice by normalizing OS biomarkers and modulating specific Bacteroides species and vitamin B6 metabolism, highlighting that vitamin B6, a methyl donor involved in DNA methylation, can promote social behaviors [138]. Nirmalkar et al. reported that FMT in children with autism for 10 weeks improved social interactions by increasing beneficial bacteria (Prevotella, Bifidobacterium, and sulfur-reducing Desulfovibrio) and normalizing microbial metabolic gene expression for folate biosynthesis, OS protection, and sulfur metabolism [139]. Abuaish et al. found that combined FMT and probiotic (Bifidobacteria) administration for 22 days improved social impairments and autistic features in juvenile male rats by enhancing glutathione-S-transferase levels [140]. Prevotella histicola, a regulator of butyrate production, transplantation mitigated cognitive impairment in vascular dementia rats by reducing MDA content, enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD and GPX), and attenuating glial cell-related inflammation via modulation of CaMKII phosphorylation in hippocampal neurons [141]. In sum, FMT exhibits promise in improving cognitive and social behaviors by restoring GM balance, attenuating OS, and enhancing antioxidant and metabolic pathways. Evidence from animal and human studies suggests it can act in synergy with probiotics and postbiotics in supporting gut–brain health. Further research is needed to optimize protocols as it presents several limitations, including variability in donor microbiota, potential risk of transmitting pathogens and infections, fluctuating long-term results, and a lack of standardized protocols for dosing, delivery, and patient selection.

6.4. Prebiotics

Prebiotics are known as a class of nondigestible food components, commonly specific fibers or carbohydrates, which selectively promote the growth or activity of commensal bacteria in the gut [142,143,144].

Prebiotics have been found to maintain gut and brain homeostasis by enhancing antioxidant capacity, reinforcing immune function, promoting the expression of tight junction proteins involved in intestinal barrier integrity, reshaping the GM, modulating the production of microbiota-derived epigenetic metabolites, and upregulating brain neurotrophic factors [145,146,147,148]. Mannan oligosaccharide has been shown to improve cognitive and behavioral deficits in the 5xFAD AD mouse model by increasing the abundance of Lactobacillus and decreasing Helicobacter, promoting butyrate production, and restoring brain oxidative and redox balance [149]. Gao et al. reported that treatment with Cistanche deserticola polysaccharides for two months mitigated cognitive impairment in D-galactose-treated mice by reshaping gut microbial homeostasis, suppressing OS, and reducing peripheral inflammation [150]. Chen et al. found that camellia oil intake ameliorated AlCl3-induced mild cognitive impairment in rats by increasing the abundance of Ruminococcaceae_UCG014, a prominent butyrate producer, which was positively correlated with antioxidant activity and reduction in OS [151]. Yang et al. demonstrated that resveratrol-loaded selenium/chitosan nano-flowers rescued glucolipid metabolism disorder-related cognitive impairment in AD mice by restoring GM balance—modulating the abundance of Enterococcus, Colidextribacter, Rikenella, Ruminococcus, Candidatus_Saccharimonas, Alloprevotella, and Lachnospiraceae_UCG-006—thereby suppressing OS, neuroinflammation, and metabolic abnormalities such as lipid deposition and insulin resistance [152]. Li et al. reported that D-galactose-induced cognitive impairment could be alleviated by acteoside, a phenylethanol glycoside from Osmanthus fragrans flowers, via rebuilding GM structure, increasing concentrations of epigenetic metabolites such as SCFAs, suppressing OS and intestinal inflammation, and restoring intestinal mucosal barrier integrity [153]. Oral administration of red cabbage anthocyanins for 12 weeks has also been shown to ameliorate age-related cognitive dysfunction in aging mice by enriching butyrate-producing bacteria, modifying the functional profile of the microbial community, decreasing MDA levels, enhancing SOD activity, and inhibiting IL-1β and IL-6 levels in serum and brain through activation of the MAPK signaling pathway [154]. In conclusion, prebiotics, such as specific fibers and plant-derived compounds, support gut–brain health by promoting beneficial bacteria, enhancing antioxidant defenses, and regulating epigenetic metabolites. Animal studies show they can improve cognitive performance and social behavior by suppressing OS and neuroinflammation and restoring gut microbial balance. Further clinical research is needed to determine their effectiveness and optimal use in humans, as prebiotics are restricted by individual variability in GM reactions, potential gastrointestinal adverse effects, and a lack of standardized dosing and long-term clinical evidence.

6.5. Antioxidants

Antioxidants such as glutathione, ascorbic acid, and uric acid may exert protective effects by maintaining the production of epigenetic metabolites like butyrate by the human gut and modulating OS [155]. For example, Gao et al. found that selenomethionine could improve D-galactose-induced cognitive impairment in mice by reducing OS, correcting dysbiosis through enhanced α-diversity, modulating taxonomic structure, and increasing the relative abundances of butyrate- and acetate-producing bacteria, including Akkermansia, Dorea, Acetatifactor, Atopostipes, Enteractinococcus, and Paenalcaligenes [156]. Cognitive impairment in aircraft-noise-exposed mice is associated with increased gut and blood–brain barrier permeability, elevated LPS translocation, higher levels of systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increased OS indicators in the intestine, heart, and hippocampus [157]. In a study by the same group, these cognitive deficits were mitigated by astaxanthin, a carotenoid antioxidant, through suppression of inflammation and oxidative damage in intestinal, cardiac, and hippocampal tissues, as well as improvement of gut and blood–brain barrier integrity [157]. Dong et al. reported that 2-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-L-ascorbic acid, an ascorbic acid derivative isolated from Lycium barbarum fruits, improved cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation induced by a high-fructose diet by increasing the abundance of butyrate- and acetate-producing bacteria, including Lactobacillus and Akkermansia, and reducing leaky gut [158]. Similarly, Li et al. demonstrated that vitamin C supplementation alleviated cognitive dysfunction in D-galactose-treated mice by mitigating hippocampal neuronal damage and enhancing anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacity through elevation of SCFA-producing genera [159]. In another study, Chatterjee et al. showed that vitamin K2/menaquinones, a vitamin produced by gut microbiota, administered for 21 days alleviated gut dysbiosis-associated cognitive decline by increasing the abundance of bacteria involved in epigenetic metabolite production—including Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Firmicutes, and Clostridium—reducing myeloperoxidase levels in the colon and brain, and abolishing OS [160]. Taken together, antioxidants such as glutathione, vitamins C and K2, and carotenoids may protect cognitive function by reducing OS and enhancing beneficial gut bacteria that produce epigenetic metabolites such as butyrate and acetate. Animal studies indicate that antioxidants enhance gut and blood–brain barrier integrity, suppress inflammation, and promote antioxidant capacity. Further clinical research is needed to confirm their effectiveness in humans.

6.6. B Vitamins

Adequate intake and serum levels of B vitamins (folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12) are linked to better cognitive and social performance by preventing neuroinflammation and OS in brain tissue, possibly via epigenetic mechanisms, particularly DNA methylation [68,161,162,163]. OS may impair vitamin B12 uptake by promoting the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which generate additional free radicals. This creates a feedback cycle in which OS and subclinical vitamin B12 deficiency reinforce each other [164]. Lower B-vitamin status plays a key role in developing cognitive impairment by increasing Hcy levels, altering DNA methylation of specific redox-related genes involved in OS, and causing subsequent oxidative damage. Moreover, folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies have been shown to exert additive effects in impairing memory function and disrupting GM in amyloid-β–infused rats [165]. Therefore, B vitamins may be considered promising candidates for improving stress, cognitive and social impairments by reshaping GM, suppressing OS, and mitigating epigenetic abnormalities [166,167,168]. Exogenous supplementation with B vitamins and folate can prevent cognitive impairment by influencing the growth of specific bacteria, enhancing the body’s antioxidant capacity, accelerating Hcy metabolism and reducing its plasma levels [169,170,171]. Mechanistically, folic acid and its reduced or methylated derivatives may provide antioxidant benefits beyond Hcy regulation by enhancing nitric oxide production, improving vascular tone, and limiting nitric oxide synthase uncoupling. The reduced forms of folate may also directly inhibit LDL oxidation [172]. Folic acid may neutralize hydroxyl and thiol radicals, providing antioxidant action and shielding lipids from peroxidative damage caused by thiyl radical attacks [173]. Generally, adequate intake and serum levels of B vitamins, including folate, B6, and B12, are linked to better cognitive and social performance by suppressing neuroinflammation, OS, and improving epigenetic abnormalities such as altered DNA methylation. Deficiencies may cause derangements in GM, elevate homocysteine levels, and exacerbate oxidative damage, creating a feedback loop that further impairs brain function. Supplementation with B vitamins is a promising strategy to improve antioxidant capacity, regulate homocysteine metabolism, and increase beneficial gut bacteria to mitigate cognitive, social, and stress-related impairments.

6.7. Ketogenic Diet (KD)

The ketogenic diet (KD) is a low-carbohydrate, adequate-protein, high-fat dietary regimen that promotes the production of ketone bodies, such as acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate, which can act as epigenetic modifiers [174,175]. KD has been shown to inhibit OS, endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, and neuronal ferroptosis, while enhancing mitochondrial respiratory complex activity, thereby exerting protective effects against cognitive deficits in neuropsychiatric diseases [176,177,178,179,180]. In a study published by Abdel-Aziz et al., eight weeks of KD feeding mitigated AD-related cognitive dysfunctions by decreasing MDA content, enhancing SOD activity, and improving neuronal survival in the hippocampus of AD model rats [181]. Similarly, Olivito et al. demonstrated that KD could rescue social and cognitive deficits, as well as repetitive behaviors, by remodeling the gut–brain axis—elevating the relative abundance of beneficial microbiota such as Akkermansia and Blautia, suppressing plasma and brain expression of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6, reducing lipid peroxidation, and improving SOD activity in BTBR mouse brain regions [182]. The KD may also improve ASD-related sociability by reducing systemic inflammation, correcting gut microbial dysbiosis, enhancing microbial butyrate metabolism, and modulating BDNF-associated miRNA signaling involved in brain function (reduced levels of miR-134 and miR-132 and elevated levels of miR-375) [183]. In sum, the KD contributes to the production of ketone bodies that act as epigenetic modifiers and support brain health. It improves cognitive and social outcomes by suppressing OS, inflammation, and neuronal damage and enhancing mitochondrial function and antioxidant activity. Existing challenges of the KD include its constrained food options, which make long-term adherence complicated, and its variable effectiveness across individuals. It may also contribute to causing gastrointestinal and metabolic disturbances in some individuals. Moreover, current findings about the beneficial effects of the KD are often based on short-term or preclinical studies; thereby, its long-term safety and efficacy remain unexplored.

6.8. Dietary Methionine Restriction

Dietary methionine restriction is a nutritional approach centered on lowering intake of the essential amino acid methionine by limiting consumption of high-methionine animal proteins and emphasizing lower-methionine plant foods [184]. Consumption of methionine-restricted diets is associated with alterations in methylation patterns, enhancing gut health, and changing the plasma metabolomic profile in rats by modulating the GM composition [185,186]. Beneficial effects of methionine-restricted diets are linked to improving intestinal barrier function, suppressing inflammatory response, OS, and enhancing concentrations of epigenetic metabolites [187,188]. As an example, Xu et al. found that dietary methionine restriction for two months ameliorated age-dependent cognitive dysfunction in mice by increasing the abundance of putative SCFA-producing bacteria, including Lachnospiraceae, Turicibacter, Roseburia, Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014, Intestinimonas, Rikenellaceae, and Tyzzerella, as well as H2S-producing bacteria such as Desulfovibrio in feces, which was associated with elevated concentrations of epigenetic metabolites, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate [189]. Collectively, dietary methionine restriction ameliorates age-related cognitive dysfunction and overall metabolic health by enhancing gut health, modulating the GM, improving intestinal barrier function, suppressing OS and inflammation, and increasing epigenetic metabolites.

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Cognitive and social deficits are defined as difficulties in thinking, learning, and interacting with others that occur in various conditions, including neurodevelopmental disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, mental illnesses, metabolic disorders, brain injury, and dementia. Advances in GM research have revealed the critical role of the gut–brain axis and GM-mediated OS in the progression of cognitive and social deficits via epigenetic mechanisms. Here, we provide a detailed overview of current evidence on the key role of GM-mediated OS in the pathogenesis of cognitive and social deficits through epigenetic alterations. These findings indicate that the pathophysiology of cognitive and social deficits is closely associated with epigenetic aberrations induced by OS, and that these aberrations can, in turn, exacerbate oxidative damage. Previous studies have shown that GM-mediated OS is linked to alterations in gut permeability, microbial diversity, relative abundances of specific taxa, epigenetic markers, and GM-derived epigenetic metabolites in both patients and animal models with cognitive and social deficits. This interplay forms a bidirectional gut–brain axis, whereby OS-induced dysbiosis affects brain epigenetics and behavior, while behavioral and stress responses feedback to further alter GM and oxidative status, creating a self-reinforcing loop that links OS, epigenetic regulation, and cognitive and social outcomes.

Despite the growing interest in microbiota-targeted interventions, several limitations hinder progress. Probiotic trials have produced inconsistent and often modest effects, possibly owing to variations in strain selection, dosing, treatment duration, and lack of control of host-specific factors. FMT, while promising in preclinical investigations, faces additional barriers such as donor–recipient incompatibility, variable engraftment, poorly defined microbial-derived factors responsible for clinical effects, and concerns regarding patient safety, like the risk of pathogen transmission. Evidence supporting prebiotics, postbiotics, and dietary interventions is still largely confined to animal studies. To advance the field, future research must include well-designed mechanistic studies and rigorously conducted double-blind, randomized controlled trials. Such studies should delineate causal pathways linking GM-mediated OS, epigenetic alterations, and neurobehavioral outcomes. Progress will also require the use of larger animal models, such as dogs and monkeys, that more closely mimic human disorders, improved preservation of human biological samples, and inclusion of robust healthy control groups. Generally, although the gut–brain connection is well established, definitive evidence on the specific OS and epigenetic mechanisms underlying GM-related cognitive and social impairments remains confined, suggesting more efforts for accurate and clinically grounded research.

A practical clinical-translation roadmap for GM-based interventions begins with robust preclinical modeling to explore specific microbial strains, consortia, or diet-responsive pathways that substantially affect cognitive function and social behavior. This stage needs germ-free and humanized models, multi-omics (metabolomics, immune profiling, transcriptomics), and mechanistic authentication to clarify targetable pathways and predictive biomarkers. From there, product development must focus on good manufacturing practice, high-stringency donor assessment and processing for FMT, and standardized formulation and dosing for probiotics or live bacteria–based therapies. In parallel, developing markers/microbial signatures, epigenetic metabolites, and neuroimmune factors is crucial for patient segmentation and indicating target engagement.

The next phase should emphasize well-designed clinical trials. Early Phase I/II studies should be randomized, placebo-controlled, and powered to assess safety, tolerability, compositional changes, and preliminary cognitive or social endpoints while precisely controlling diet, drugs, and other interfering factors. If early signals are robust and reproducible, larger multicenter trials can follow up clinically substantive outcomes, pre-specified subgroups, and prolonged effectiveness. Engagement with regulators from the outset guarantees alignment on endpoints, safety screening, and quality control for live microbial therapeutics. Generally, successful translation will need to show not only short-term improvements in behavioral abnormalities but also mechanistic clarity, reproducibility, and long-term safety, setting the stage for GM-based interventions to become robust supportive therapies or disease-altering agents in neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V.J.; methodology, D.V.J. and F.A.; software, D.V.J. and F.A.; validation, S.A., A.A.P.-T. and D.V.J.; formal analysis F.A.; investigation, F.A., S.A., A.A.P.-T. and D.V.J.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A., S.A., A.A.P.-T. and D.V.J.; writing—review and editing, S.A., A.A.P.-T. and D.V.J.; visualization, S.A., A.A.P.-T. and D.V.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Faria Ashrafi for her assistance with the illustrations in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Das, T.K.; Ganesh, B.P. Interlink between the gut microbiota and inflammation in the context of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2206504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houldsworth, A. Role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders: A review of reactive oxygen species and prevention by antioxidants. Brain Commun. 2024, 6, fcad356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunyadi, A. The mechanism(s) of action of antioxidants: From scavenging reactive oxygen/nitrogen species to redox signaling and the generation of bioactive secondary metabolites. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 2505–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofin, D.-M.; Sardaru, D.-P.; Trofin, D.; Onu, I.; Tutu, A.; Onu, A.; Onită, C.; Galaction, A.I.; Matei, D.V. Oxidative stress in brain function. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, M.; Jurajda, M.; Duris, K. Oxidative stress in the brain: Basic concepts and treatment strategies in stroke. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.S.; Oliver, P.L. ROS generation in microglia: Understanding oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Meng, S. Oxytocin improves animal behaviors and ameliorates oxidative stress and inflammation in autistic mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Wu, X.; Li, L. Oxidative stress induces DNA demethylation and histone acetylation in SH-SY5Y cells: Potential epigenetic mechanisms in gene transcription in Aβ production. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Song, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B. H4K12 lactylation potentiates mitochondrial oxidative stress via the Foxo1 pathway in diabetes-induced cognitive impairment. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 78, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugon, P.; Dufour, J.-C.; Colson, P.; Fournier, P.-E.; Sallah, K.; Raoult, D. A comprehensive repertoire of prokaryotic species identified in human beings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Okpara, E.S.; Hu, W.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Chiang, J.Y.; Han, S. Interactive relationships between intestinal flora and bile acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohesara, S.; Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Pirani, A.; Thiagalingam, S. Therapeutic Horizons: Gut Microbiome, Neuroinflammation, and Epigenetics in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cells 2025, 14, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciolla, C.; Manganelli, M.; Di Chiano, M.; Montenegro, F.; Gallone, A.; Sallustio, F.; Guida, G. Valeric Acid: A Gut-Derived Metabolite as a Potential Epigenetic Modulator of Neuroinflammation in the Gut–Brain Axis. Cells 2025, 14, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieryńska, M.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Struzik, J.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P. Integrity of the intestinal barrier: The involvement of epithelial cells and microbiota—A mutual relationship. Animals 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Z.-Y. Crosstalk Between Intestinal Microbiota and Host Defense Peptides in Fish. Biology 2025, 14, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, P.; Henriques, A.C.; Azevedo, R.; Sá, S.I.; Cardoso, A.; Fonseca, B.; Barbosa, J.; Leal, S. Gut microbiome composition and metabolic status are differently affected by early exposure to unhealthy diets in a rat model. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, P.; Pal, N.; Kumawat, M.; Shubham, S.; Sarma, D.K.; Tiwari, R.R.; Kumar, M.; Nagpal, R. Impact of environmental pollutants on gut microbiome and mental health via the gut–brain axis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubas, N.C.; Torres, A.; Maunakea, A.K. The gut microbiome and epigenomic reprogramming: Mechanisms, interactions, and implications for human health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleky, H.M.; Pirani, A.; Pettinato, G. Psychosomatic Disorders, Epigenome, and Gut Microbiota. Cells 2025, 14, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Qing, W.; Liu, F.; Zeng, N.; Wu, F.; Shi, Y.; Gao, X.; Cheng, M.; Li, H. Congenitally underdeveloped intestine drives autism-related gut microbiota and behavior. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 105, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, E.; Jarmukhanov, Z.; Nurgaziyev, M.; Kossumov, A.; Nurgozhina, A.; Mukhanbetzhanov, N.; Sergazy, S.; Chulenbayeva, L.; Issilbayeva, A.; Askarova, S. Enterococcus dysbiosis as a mediator of vitamin D deficiency-associated memory impairments. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohesara, S.; Abdolmaleky, H.M.; Dickerson, F.; Pinto-Tomas, A.A.; Jeste, D.V.; Thiagalingam, S. Associations of microbiome pathophysiology with social activity and behavior are mediated by epigenetic modulations: Avenues for designing innovative therapeutic strategies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 174, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohesara, S.; Abdolmaleky, H.M.; Dickerson, F.; Pinto-Tomás, A.A.; Jeste, D.V.; Thiagalingam, S. Maternal Gut Microbiome-Mediated Epigenetic Modifications in Cognitive Development and Impairments: A New Frontier for Therapeutic Innovation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellver-Sanchis, A.; Pallàs, M.; Griñán-Ferré, C. The contribution of epigenetic inheritance processes on age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Epigenomes 2021, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, E.; Koros, C.; Hatzimanolis, A.; Stefanis, L.; Scarmeas, N.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Exploring the genetic landscape of mild behavioral impairment as an early marker of cognitive decline: An updated review focusing on Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogrinc, D.; Kramberger, M.G.; Emeršič, A.; Čučnik, S.; Goričar, K.; Dolžan, V. Genetic polymorphisms in oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways as potential biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.-C.; Su, M.-T.; Bao, L.; Lee, P.-L.; Tutwiler, S.; Yeh, T.-K.; Chang, C.-Y. MicroRNAs modulate CaMKIIα/SIRT1 signaling pathway as a biomarker of cognitive ability in adolescents. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2025, 44, 100970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelstaedt, N.N.; Becker, A.L.; de Freitas, D.N.; Zanin, R.F.; Stein, R.T.; de Souza, A.P.D. DNA methylation and immune memory response. Cells 2021, 10, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younesian, S.; Yousefi, A.-M.; Momeny, M.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Bashash, D. The DNA methylation in neurological diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Narayan, C.L.; Mahesan, A.; Kamila, G.; Kapoor, S.; Chaturvedi, P.K.; Scaria, V.; Velpandian, T.; Jauhari, P.; Chakrabarty, B. Transmethylation and Oxidative Biomarkers in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Liang, F.; Meng, G.; Nie, Z.; Zhou, R.; Cheng, W.; Wu, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y. Redox/methylation mediated abnormal DNA methylation as regulators of ambient fine particulate matter-induced neurodevelopment related impairment in human neuronal cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, S.; Fuchs, G.J.; Schulz, E.; Lopez, M.; Kahler, S.G.; Fussell, J.J.; Bellando, J.; Pavliv, O.; Rose, S.; Seidel, L. Metabolic imbalance associated with methylation dysregulation and oxidative damage in children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, S.; Buchanan, E.; Mahony, C.; O’Ryan, C. DNA methylation of PGC-1α is associated with elevated mtDNA copy number and altered urinary metabolites in autism spectrum disorder. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 696428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.G.; Balasubramanian, N.; Manjrekar, R.; Banerjee, T.; Sakharkar, A. DNA methylation-mediated Mfn2 gene regulation in the brain: A role in brain trauma-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and memory deficits. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 3479–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boruch, A.E.; Madrid, A.; Papale, L.A.; Bergmann, P.E.; Renteria, I.; Faasen, S.; Cook, D.B.; Alisch, R.S.; Hogan, K.J. Differential DNA methylation in blood in nuclear genes that encode mitochondrial proteins in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Plano, L.M.; Saitta, A.; Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A. Epigenetic changes in Alzheimer’s disease: DNA methylation and histone modification. Cells 2024, 13, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, H.A.; Thomas, C.M.; Nge, G.G.; Elefant, F. Modulating Cognition-Linked Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) as a Therapeutic Strategy for Neurodegenerative Diseases: Recent Advances and Future Trends. Cells 2025, 14, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.-L.; Tang, S.-F.; Ming, Q.; Ao, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.-Z.; Yu, C.; Zhao, H. Curcumin protects against manganese-induced neurotoxicity in rat by regulating oxidative stress-related gene expression via H3K27 acetylation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 236, 113469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, C.; Tang, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ban, J.; Li, J. Identification of histone acetylation modification sites in the striatum of subchronically manganese-exposed rats. Epigenomics 2024, 16, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; DesMarais, T.L.; Tong, Z.; Yao, Y.; Costa, M. Oxidative stress alters global histone modification and DNA methylation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 82, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, Y.; Gu, X.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Li, L.; Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, H. Aberrant histone acetylation and dysregulated synaptic plasticity in cognitive impairment induced by a high-methionine diet. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Xie, W.; Lu, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Tang, M.; Pfaff, D.W. Maternal diabetes induces autism-like behavior by hyperglycemia-mediated persistent oxidative stress and suppression of superoxide dismutase 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23743–23752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, J.-M.; Zhao, H.; Ao, C.-Y.; Ao, L.-H.; Ban, J.-Q.; Li, J. Mechanism of KAT2A regulation of H3K36ac in manganese-induced oxidative damage to mitochondria in the nervous system and intervention by curcumin. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 273, 116155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ao, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ming, Q.; Li, C.; Zhao, H.; Ban, J.; Li, J. Manganese induces oxidative damage in the hippocampus by regulating the expression of oxidative stress-related genes via modulation of H3K18 acetylation. Environ. Toxicol. 2024, 39, 2240–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLucas, M.; Sánchez, J.; Palou, A.; Serra, F. The impact of diet on miRNA regulation and its implications for health: A systematic review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.; Afzal, M.; Castresana, J.S.; Shahi, M.H. A comprehensive review of miRNAs and their epigenetic effects in glioblastoma. Cells 2023, 12, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, S.K.; Kalirad, A.; Rafie, S.; Behzad, E.; Dezfouli, M.A. The role of microRNAs in neurobiology and pathophysiology of the hippocampus. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1226413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Spiers, J.G.; Vassileff, N.; Khadka, A.; Jaehne, E.J.; van den Buuse, M.; Hill, A.F. microRNA-146a modulates behavioural activity, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress in adult mice. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 124, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavari, B.; Barnett, M.M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Geaghan, M.P.; Graham, A.; Cairns, M.J. microRNA and the Post-Transcriptional Response to Oxidative Stress during Neuronal Differentiation: Implications for Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric Disorders. Life 2024, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Tyryshkin, K.; Elmi, N.; Feilotter, H.; Andreazza, A.C. Examining redox modulation pathways in the post-mortem frontal cortex in patients with bipolar disorder through data mining of microRNA expression datasets. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 99, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.N. Oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines may act as one of the signals for regulating microRNAs expression in Alzheimer’s disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2017, 162, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H. Sirt1/Nrf2 signalling pathway prevents cognitive impairment in diabetic rats through anti-oxidative stress induced by miRNA-23b-3p expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 8414–8422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan-Qiang, H.; Hai-Hua, Q.; Chi, Z.; Miao, W.; Cui, Z.; Zi-Yin, L.; Jing, H.; Yi-Wei, W. miR-146a aggravates cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease-like pathology by triggering oxidative stress through MAPK signaling. Neurologia 2023, 38, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Al-Ahmady, Z.S.; Du, W.; Duan, J.; Liao, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wei, Z.; Hua, J. Maternal exposure to PM2. 5 induces cognitive impairment in offspring via cerebellar neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, L.; Ma, J.; Xu, W.; Chen, M.; Cong, G.; Liu, J. miR-153 prevents NRF2 nuclear translocation to drive hypoperfusion-related cognitive deficits by targeting KPNA5. J. Neurosci. 2025, 45, e2148242025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawaf, H.A.; Alghadir, A.H.; Gabr, S.A. Molecular changes in circulating microRNAs’ expression and oxidative stress in adults with mild cognitive impairment: A biochemical and molecular study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-D.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, B.-H.; Wang, X.-T.; Chen, Y.-X.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Tian, Y.-R.; Xie, F.; Qian, L.-J. Homocysteine-induced disturbances in DNA methylation contribute to development of stress-associated cognitive decline in rats. Neurosci. Bull. 2022, 38, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.; Preeti, K.; Sood, A.; Nair, K.P.; Khan, S.; Rao, B.S.; Khatri, D.K.; Singh, S.B. Neuroepigenetic changes in DNA methylation affecting diabetes-induced cognitive impairment. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 2005–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Feng, J.; Jian, L.-Y.; Fan, X.-Y. DNA hypomethylation promotes learning and memory recovery in a rat model of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 863–868. [Google Scholar]

- Asgharzadeh, N.; Diziche, A.N.; Amini-Khoei, H.; Yazdanpanahi, N.; Korrani, M.S. N-acetyl cysteine through modulation of HDAC2 and GCN5 in the hippocampus mitigates behavioral disorders in the first and second generations of socially isolated mice. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 18, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, N.S.; Elatrebi, S.; Said, R.; Ibrahim, H.F.; Omar, E.M. Potential mechanisms underlying the association between type II diabetes mellitus and cognitive dysfunction in rats: A link between miRNA-21 and Resveratrol’s neuroprotective action. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 2375–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, A.; Kushima, I.; Miyashita, M.; Toriumi, K.; Suzuki, K.; Horiuchi, Y.; Kawaji, H.; Takizawa, S.; Ozaki, N.; Itokawa, M. Dysregulation of post-transcriptional modification by copy number variable microRNAs in schizophrenia with enhanced glycation stress. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asraf, K.; Zaidan, H.; Natoor, B.; Gaisler-Salomon, I. Synergistic, long-term effects of glutamate dehydrogenase 1 deficiency and mild stress on cognitive function and mPFC gene and miRNA expression. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionaki, E.; Ploumi, C.; Tavernarakis, N. One-carbon metabolism: Pulling the strings behind aging and neurodegeneration. Cells 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, P.; Strippoli, V.; Fang, B.; Cimmino, L. B vitamins and one-carbon metabolism: Implications in human health and disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Guo, Y.; Cui, L.; Huang, L.; Guo, Q.; Huang, G. Study of diet habits and cognitive function in the Chinese middle-aged and elderly population: The association between folic acid, B vitamins, vitamin D, coenzyme Q10 supplementation and cognitive ability. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, A.; Hamano, T.; Enomoto, S.; Shirafuji, N.; Nagata, M.; Kimura, H.; Ikawa, M.; Yamamura, O.; Yamanaka, D.; Ito, T. Influences of vitamin B12 supplementation on cognition and homocysteine in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency and cognitive impairment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankurtaran, M.; Yesil, Y.; Kuyumcu, M.E.; Oztürk, Z.A.; Yavuz, B.B.; Halil, M.; Ulger, Z.; Cankurtaran, E.S.; Arıoğul, S. Altered levels of homocysteine and serum natural antioxidants links oxidative damage to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 33, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchantchou, F.; Goodfellow, M.; Li, F.; Ramsue, L.; Miller, C.; Puche, A.; Fiskum, G. Hyperhomocysteinemia-induced oxidative stress exacerbates cortical traumatic brain injury outcomes in rats. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 41, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.D.; ElKomy, M.A.; Othman, A.I.; Amer, M.E.; El-Missiry, M.A. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances cognitive and memory performance and protects against brain injury in methionine-induced hyperhomocysteinemia through Interdependent molecular pathways. Neurotox. Res. 2022, 40, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, Y.-M.; Ruan, M.-H.; Zhou, A.-H.; Qian, Y.; Chen, C. Homocysteine inhibits neural stem cells survival by inducing DNA interstrand cross-links via oxidative stress. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 635, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Sitdikova, G. Homocysteine: Biochemistry, molecular biology and role in disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaric, B.L.; Obradovic, M.; Bajic, V.; Haidara, M.A.; Jovanovic, M.; Isenovic, E.R. Homocysteine and hyperhomocysteinaemia. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 2948–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tao, L.; Qin, Z.; Xiao, R. Dietary intakes and biomarker patterns of folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 can be associated with cognitive impairment by hypermethylation of redox-related genes NUDT15 and TXNRD1. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, F.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, L. Homocysteine induced N6-methyldeoxyadenosine modification perturbation elicits mitochondria dysfunction contributes to the impairment of learning and memory ability caused by early life stress in rats. Redox Biol. 2025, 84, 103668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, G.-S.; Gong, J.; Mao, Y.-M.; Wu, J.-J.; Bi, S.-G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Shen, M.-T.; Lei, Z.-Y.; Nie, Y.-J. H3K4 trimethylation mediate hyperhomocysteinemia induced neurodegeneration via suppressing histone acetylation by ANP32A. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 6788–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.-C.; Zhao, W.-X.; Sheng, Y.; Yun, Y.-J.; Ma, T.; Fan, N.; Song, J.-Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Serum homocysteine showed potential association with cognition and abnormal gut microbiome in major depressive disorder. World J. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 102567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ke, H.; Wang, S.; Mao, W.; Fu, C.; Chen, X.; Fu, Q.; Qin, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, B. Leaky gut plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of autism in mice by activating the lipopolysaccharide-mediated toll-like receptor 4–myeloid differentiation factor 88–nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway. Neurosci. Bull. 2023, 39, 911–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuda, H.; Okamoto, T.; Wada, K. Leaky gut: Effect of dietary fiber and fats on microbiome and intestinal barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morena, D.; Lippi, M.; Scopetti, M.; Turillazzi, E.; Fineschi, V. Leaky gut biomarkers as predictors of depression and suicidal risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzki, L.; Maes, M. From “Leaky Gut” to Impaired Glia-Neuron Communication in Depression. In Major Depressive Disorder: Rethinking and Understanding Recent Discoveries; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Semenova, N.; Garashchenko, N.; Kolesnikov, S.; Darenskaya, M.; Kolesnikova, L. Gut microbiome interactions with oxidative stress: Mechanisms and consequences for health. Pathophysiology 2024, 31, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Saigo, N.; Nagasaki, Y. Direct evidence for the involvement of intestinal reactive oxygen species in the progress of depression via the gut-brain axis. Biomaterials 2023, 295, 122053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]