Abstract

This study aims to optimize the estimation of reference evapotranspiration (ETo) in data-scarce regions by integrating ERA5-Land reanalysis data with machine learning (ML) models. Daily meteorological data from 33 stations across Turkey’s diverse climate zones (1981–2010) were utilized to train and validate three ML models: Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Extreme Learning Machine (ELM). The methodology involved rigorous quality control of ground-based observations, spatial correlation of ERA5-Land grids to station locations, and performance evaluation under various data-limited scenarios. Results indicate that while ERA5-Land provides highly accurate solar radiation (Rs) and temperature (T) data, variables like wind speed (U2) and relative humidity (RH) exhibit systematic biases. Among the used models, XGBoost demonstrated superior performance (R2 = 0.95, RMSE = 0.43 mm day−1, and MAE = 0.30 mm day−1) and computational efficiency. This study provides a robust, regionally calibrated framework that corrects reanalysis biases using ML, offering a reliable alternative for ETo estimation in areas where local measurements are insufficient for sustainable water management.

1. Introduction

Evapotranspiration (ET) refers to the combined process of evaporation from soil and water surfaces and transpiration from the vegetation canopy [1]. Accurate estimation of ET is a critical parameter for effective water resource planning, irrigation management, energy production, and flood control [2,3,4]. Meteorological factors play a crucial role in agricultural productivity and the efficiency of water management systems. In particular, consistent and reliable meteorological data are essential for optimal irrigation scheduling, which directly affects crop yield and overall production performance [4].

Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) is a fundamental component of the hydrological cycle, representing the transfer of water from soil to the atmosphere [5]. Typically, ETc is estimated by multiplying reference evapotranspiration (ETo) by the crop coefficient (Kc). Consequently, ETo serves as a key parameter in estimating irrigation water requirements [6], designing irrigation systems [7], and assessing drought risks [8,9]. Accurate estimation of ETo is particularly crucial for analyzing the water stress effects on crop yield in arid and semi-arid regions, where water resources are scarce and climatic variability is high [10]. Several empirical and physically based methods have been developed to estimate ETo accurately, including Hargreaves–Samani [11], Thornthwaite [12], Blaney–Criddle [13], Priestley–Taylor [14], and Penman–Monteith (PM) [15] approaches. Among these, the PM method has been designed as the gold standard by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and is recommended in the FAO-56 guidelines for regions where complete meteorological data are available [16]. Due to its high accuracy, the FAO-56 PM method has been validated in various countries, including China [17], Brazil [18], Egypt [19], Iran [20], the Czech Republic [21], and Turkey [22]. Although the method has demonstrated high accuracy, its major limitation is the dependence on in situ meteorological measurements, such as air temperature (T), solar radiation (Rs), wind speed (U2), and relative humidity (RH) [16]. This dependency poses significant challenges in regions where meteorological data are sparse or unavailable [23]. Additionally, retrieved data can be affected by sensor characteristics, instrument drift, or a low temporal sampling frequency [24]. Furthermore, the sparse distribution of meteorological stations often leads to data gaps and limited accessibility to the data, as stations are managed by different administrative entities [24,25].

Two alternative approaches are commonly employed when meteorological data are missing or of insufficient quality. The first approach involves empirical methods that require fewer input parameters. Among these, the Hargreaves–Samani model is the most widely used, requiring only maximum (Tmax) and minimum air temperature (Tmin), as well as extra-terrestrial radiation [26,27]. However, empirical methods exhibit lower accuracy when applied to the different climatic regions due to their limited generalization capability [28,29,30]. The second approach utilized global climate reanalysis datasets to compensate for missing or low-quality ground meteorological observations. Reanalysis datasets are produced by assimilating various satellite and ground-based observational data into weather prediction models [24,31]. Although such datasets provide a promising alternative in regions with sparse meteorological networks, they contain uncertainties due to differences in the model physics used and the data assimilation method [32]. Therefore, reanalysis products are often evaluated against ground-based meteorological observations to ensure their reliability and accuracy. For these purposes, several gridded datasets have been employed to assess model performance, including CLDAS in China [33], CERES in South America [34], NASA POWER in Mexico [35], AgERA5 in West Africa [36], and CMIP6 in East Asia [37]. To overcome performance limitations associated with empirical or reanalysis-based methods, machine learning (ML) models have been used in recent years due to their superiority in modeling ETo. Commonly applied algorithms include Extreme Gradient Boosting Algorithm (XGBoost) [38], Random Forest (RF) [39], Artificial Neural Networks [40], Convolutional Neural Networks [41], and Ensemble Methods [4]. Nevertheless, most of the studies have relied on ground-based meteorological data for ETo estimation. Furthermore, the success of ML models is highly dependent on the quality and quantity of the input data. Despite the increasing availability of global reanalysis products, a systematic evaluation is still required to bridge the gap between coarse-resolution satellite data and local-scale ETo requirements in complex terrains like Turkey. While several studies have utilized ERA5-Land data for climatic analysis [42,43], its direct integration with advanced ML models for regional ETo estimation remains relatively unexplored. This study addresses this necessity by defining the physical limitations of reanalysis datasets in capturing local microclimates and proposing an ML based correction framework.

The primary objective of this study is to assess the robustness, performance, and consistency of ML models in estimating ETo using either a full reanalysis dataset (ERA5-Land) or a simplified approach based solely on limited variables (Tmax and Tmin). To achieve this goal, the study focuses on three specific aims: (i) implementing a solar radiation (Rs) QA/QC calibration step prior to comparison; (ii) systematically evaluating full versus temperature-only ERA5-Land inputs across multiple climate types; and (iii) quantifying the trade-off between accuracy and computational cost among the selected ML models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

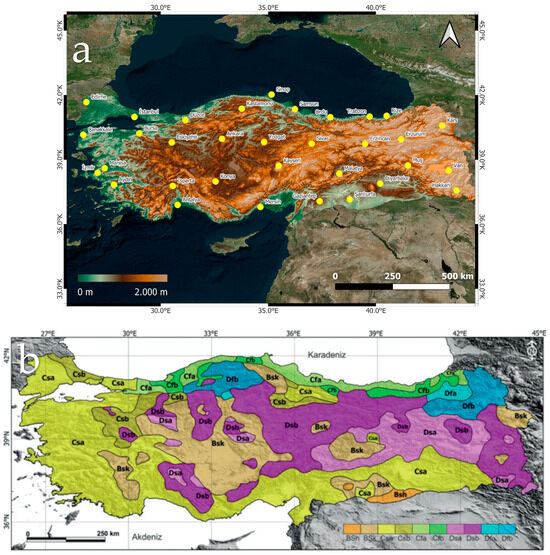

The study area is located in Turkey (Figure 1), which lies between 36 and 42° N latitude and 26–45° E longitude, with a total surface area of 783,562 km2 and a mean elevation of 1141 m above sea level [44]. Turkey is surrounded on three sides by seas, and the extension of the mountains and the diversity of terrestrial features have led to the emergence of different types of climates. Within the study area, four principal climate types are distinguished: continental climate, Mediterranean climate, Marmara (or transitional) climate, and Black Sea climate [45]. Turkey’s geographical location and varied topography result in characteristic regional climate types that significantly influence ETo patterns. In the Mediterranean and Aegean coastal regions, ETo is primarily driven by high Rs and high T, particularly during the prolonged dry summer season. In the plateau of Central Anatolia, which is characterized by a semi-arid continental climate, lower relative humidity and higher vapor pressure deficits become more dominant factors in increasing ETo rates. Conversely, the Black Sea region, with its humid and temperate climate, generally exhibits lower ETo values due to frequent cloud cover and high precipitation levels, which limit the available solar energy. These regional specificities underscore the challenge of accurate ETo estimation in data-scarce regions of Turkey and justify the integration of high-resolution reanalysis data, such as ERA5-Land.

Figure 1.

(a) Elevation variations across Turkey and spatial distribution of meteorological stations, as well as (b) the distribution of climate zones across the study area (Öztürk et al. [46]).

2.2. Data Collection

This study utilized two different datasets: ground meteorological data and meteorological data estimated using the ERA5-Land model. The ground-based data were recorded by the Turkish Meteorological Service (MGM). When evaluating these two datasets, the climate station and its corresponding ERA5-Land grid cell values were selected for the period between 1 January 1981 and 31 December 2010. The meteorological data for the specified 30-year period provide sufficient data for the ground station and ERA5-Land modeling comparison.

2.2.1. Ground-Based Observations

The daily meteorological data from the 33 different meteorological stations used in the study were provided by the MGM (Table 1). The meteorological measurements used include daily Tmax (°C) and Tmin (°C), humidity (Rh, %), wind speed (U2, m s−1), Rs (MJ m−2 day−1), and air pressure (P, kPa). All meteorological parameters were measured at a height of 2 m. Although meteorological stations provided records for the 1981–2010 period, some stations contained short gaps. These records were screened for potential errors and outliers with the use of the agweather-qaqc package (v1.0.4). Details of the established procedures can be found in Dunkerly et al. [47]. Regarding data completeness, approximately 5.6% of the total potential daily records from the 33 stations (1981–2010) were identified as missing or erroneous and were subsequently removed. A high-quality finalized dataset of 341,517 valid daily observations was created for further analysis as a result.

Table 1.

Long-term average annual climatic characteristics of the 33 meteorological stations (1981–2010).

The reliability of ground-based weather data is often constrained by limitations in accuracy, temporal continuity, and consistency due to instrumentation anomalies such as sensor failure, deviation, and poor calibration. Therefore, ground-based weather data require quality assurance and quality control (QAQC) to ensure the accurate estimation of ETo. In this study, the agweather-qaqc v1.0.4 Python package [47] was utilized for QAQC analysis. Within this framework, theoretically clear-sky solar radiation (Rso) was simulated using site-specific location and RH data following ASCE standards, thereby optimizing the expected solar radiation (Rs) curve. Comprehensive details regarding these procedures can be found in [47].

In this study, the FAO 56-PM [16] method was used to calculate from ground-based measurements (Equation (1)).

In the equation, Rn is net radiation (MJm−2 day−1); G is soil heat flux (MJm−2 day−1); Tair, daily average air temperature (°C); U2, wind speed measured at 2 m height; es and ea, saturated and actual vapor pressure values, respectively (Equations (2) and (3)); γ, psychrometric constant (Equation (4)) (kPa °C−1); and ∆, the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve (kPa °C−1).

where Cp is specific heat at constant pressure (1.013 10−3 MJ kg−1 °C−1); shows the ratio of the molecular weight of water vapor/dry air (0.622); and depicts the latent heat of vaporization (2.45 MJ kg−1).

2.2.2. ERA5-Land Gridded Weather Dataset

ERA5-Land is the fifth-generation global atmospheric reanalysis dataset for climate and weather applications, developed and maintained by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). This system provides 50 variables that describe the energy balance of land surfaces, with hourly temporal resolution and 0.1° (~9–11 km) spatial resolution, spanning from 1950 to the present in near real-time [23]. The data is provided with a 5-day delay and is freely available [48]. Among the meteorological data provided by ERA5-Land are air (), , and dewpoint temperature ), as well as solar radiation (), wind speed () and pressure (). is not measured directly but rather derived from actual vapor pressure () and saturated vapor pressure (), calculated as a function of and , respectively (Equations (2) and (3)). ERA5-Land provides at 10 m height, whereas the FAO-56 PM equation is defined for wind at 2 m. To make the datasets comparable, the first 10 m wind speed was derived from the u10/v10 components, and then it was downscaled to 2 m using a neutral logarithmic wind profile (Equation (5))

where is the wind speed at 10 m; is the wind speed at 2 m; and is the height of the wind measurement.

The ERA5-Land parameters were extracted as point data that correspond to the exact geographical coordinates of each meteorological station. This extraction was carried out using the nearest-neighbor approach in Google Earth Engine. It was ensured that the value of the grid cell directly covering the station location was retrieved without spatial smoothing. The specified parameters were used as inputs for the ML models to estimate ETo, which was calculated from weather station measurements.

2.3. Machine Learning Models

This study employs ML models widely recognized in the literature for their efficacy in estimating ETo. To evaluate the applicability of these models across different data availability scenarios, two distinct input configurations were adopted. The first approach utilizes the full ERA5-Land dataset, while the second incorporates a limited set of meteorological variables (Tmax and Tmin). This dual-approach framework aims to assess the performance of ML-based estimation as a viable alternative to the standard FAO56-PM method, particularly in regions with sparse data. Consequently, three robust algorithms, namely RF, XGBoost, and the Extreme Learning Machine (ELM), were selected to leverage recent methodological advancements [6,49,50]. To evaluate the estimation accuracy of the models, the dataset was divided using a temporal split strategy applied globally across all 33 meteorological stations. The period from 1981 to 2000 was employed to form the training set (used for model development and hyperparameter tuning), while the subsequent period from 2001 to 2010 was used for testing. This splitting approach was chosen to assess the temporal generalization of the models rather than their spatial transferability to unseen locations. To prevent data leakage, hyperparameter optimization was performed solely on the 1981–2000 training set using 5-fold cross-validation, ensuring the testing period remained entirely unseen during the learning process. Min–Max scaling was used to standardize input features to 0–1, especially for the ELM model to prevent neuron saturation [51]. All data processing and ML model development were implemented within the Python programming environment (version 3.13.5). The handling of meteorological datasets and time-series manipulations was performed using the pandas library. The ML models were implemented using the following open-source libraries: ‘scikit-learn’ for RF, and ‘xgboost’ for XGBoost.

RF is a supervised ensemble learning technique that constructs a multitude of decision trees during training. As an extension of Breiman’s bagging method, RF improves upon standard boosting methods by reducing variance and preventing overfitting [52,53]. The final model estimation is calculated by averaging the outputs of individual trees. RF was selected for its computational efficiency, rapid training speed, and ability to handle high-dimensional data for both regression and classification tasks [54]. To optimize performance, grid search and cross-validation techniques were employed to tune key hyperparameters, including the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum tree depth (max_depth), and the minimum samples required for node splitting (min_samples_split) and leaf nodes (min_samples_leaf) [4].

XGBoost is a highly efficient and scalable implementation of the gradient boosting framework. Since its introduction in 2016 [55], XGBoost has been widely adopted due to its parallel processing capabilities, which offer significant speed advantages over traditional algorithms. The core principle of XGBoost involves iteratively adding new models to correct the errors of prior ones. The algorithm optimizes a specific objective function (Equation (6)) that combines a convex loss function with a regularization term to control model complexity:

where represents the training loss (the difference between the actual and estimated output), and denotes the regularization term. This complexity term, which accounts for the structure of the tree and leaf weights, is crucial for smoothing the final learned weights and preventing overfitting [50].

The ELM algorithm, as a single-hidden-layer feedforward neural network, offers a fast, efficient, and robust approach for both classification and regression problems. The basic principle is based on the random initialization of input weights and the analytical calculation of output weights, rather than the iterative tuning used in traditional neural networks. The algorithm depends on two main parameters: the activation function and the number of neurons in the hidden layer. In the learning process, the input weights and biases are assigned randomly and remain fixed, eliminating the need for gradient-based backpropagation. The output weights are then determined mathematically using the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse to minimize the error. The main advantages of ELM include its extremely rapid training speed, good generalization performance, and the avoidance of local minima [51].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Model performance was evaluated using three widely accepted statistical indices: the coefficient of determination (), the root mean square error (RMSE), and the mean absolute error (MAE). Detailed descriptions of these metrics can be found in [56]. The data analysis and statistical evaluations were conducted using the R (Version 2024.04. 2) environment. Data visualizations and graphical comparisons were generated using the Matplotlib (3.6.2) library in Python and the ggplot2 (3.5.1) package in R.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Rs Calibration on ETo Estimation

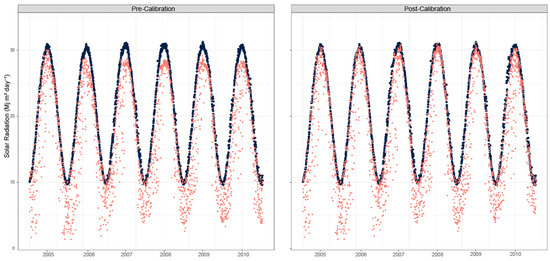

In this study, a QAQC analysis was employed to calibrate the Rs. The calibration process involved dividing the observation records into 60-day intervals. Within each period, the measured Rs was compared against the theoretical Rso. Adjustment was triggered if the ratio of Rso to Rs (derived from the average of the top 10% of daily Rs values in a 60-day period) was less than 0.97 or greater than 1.037 [47]. The Rso values were calculated using the day of the year, atmospheric water vapor, and station elevation, following the methodology of Allen et al. [16]. Figure 2 illustrates a representative comparison of measured Rs versus the expected Rso for the Düzce weather station for the period 2005 to 2010. The Düzce weather station was chosen because it represents a transitional climate zone and possesses highly consistent, continuous data records.

Figure 2.

Comparison of measured solar radiation (Rs) against the clear-sky solar radiation (Rso): pre-calibration (left) and post-calibration (right). The solid black line indicates the calculated Rso, representing the theoretical upper limit of Rs under cloud-free conditions.

The calibration of Rs resulted in significant improvements in ETo estimates across 33 meteorological stations. Table 2 presents the comparison of ETo estimations using calibrated and uncalibrated Rs over the 30-year study period (1981–2010). The calibration procedure yielded a high correlation, with the R2 ranging from 0.96 to 0.99. The RMSE for all stations was 0.22 mm day−1. Results showed that performance metrics varied with climatic conditions. Coastal stations (e.g., Antalya, Mersin, Izmir, Trabzon, and Samsun) demonstrated the lowest errors (RMSE: 0.12–0.17 mm day−1; MAE: 0.06–0.09 mm day−1), whereas stations situated in transitional climates or continental interiors with complex topography (e.g., Gaziantep, Edirne, Isparta, and Diyarbakir) exhibited higher discrepancies (RMSE: 0.36–0.43 mm day−1 and MAE: 0.19–0.33 mm day−1). Despite these spatial variations, all stations maintained R2 values above 0.96, confirming the robustness of the calibration methodology across diverse environmental conditions.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and performance metrics for uncalibrated and calibrated ETo estimates.

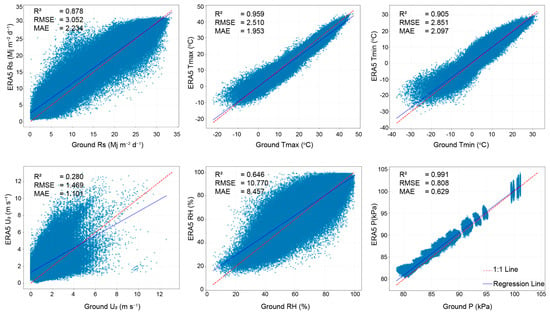

3.2. Evaluation of ERA5-Land Gridded Data

In this study, ERA5-Land gridded weather data were evaluated with ground measurements from 1981 to 2010 across Turkey (33 stations). For this purpose, time series of Rs, Tmax, Tmin, U2, RH, and P at daily scales were used, as these are the required input parameters for daily ETo calculation using the FAO 56-PM method. Figure 3 depicts the performance of ERA5-Land data against the in situ ground weather measurements. Generally, Rs, Tmax, Tmin, and P variables exhibit high correlations with ground measurements and lower bias values (1.09, −1.13, 0.21, and 0.43 for Rs, Tmax, Tmin, and P, respectively). In contrast, U2 and RH have lower R2 values and higher RMSE and MAE values. The average bias for U2 is 0.867, indicating that ERA5-Land tends to overestimate U2. Likewise, the positive bias (2.59) calculation for RH indicates an overestimate for RH.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of ground-based meteorological measurements (MGM) and ERA5-Land reanalysis estimates for Rs, Tmax, Tmin, U2, RH, and P over the 1981–2010 period.

There was a significant positive correlation between estimated and measured Rs. For all stations, the R2 value was calculated as 0.878, and the RMSE and MAE were calculated as 3.052 and 2.234 MJ m−2 day−1, respectively. Since the magnitude of the bias is relatively small compared to the average of Rs, the ERA5-Land Rs data can be considered as reliable.

The Tmax comparison plot in Figure 3 shows that the estimated and measured data closely follow each other, with an R2 of 0.959, while the RMSE and MAE are 2.510 °C and 1.953 °C, respectively. The mean bias of −1.139 °C indicates a slight negative tendency of ERA5-Land to underestimate Tmax, which becomes more evident during cold winter days but remains relatively small in magnitude, suggesting that ERA5-Land Tmax can be considered accurate for climatic studies.

For Tmin, the results are broadly similar in terms of overall performance, with R2 of 0.905 and RMSE and MAE of 2.851 °C and 2.097 °C, respectively. However, the mean bias differs, with a mean bias of 0.219 °C indicating that ERA5-Land tends to overestimate nighttime temperatures slightly. This bias in Tmin is more pronounced during colder winter times, highlighting some limitations of ERA5-Land under certain conditions.

For U2, the agreement between ERA5-Land and MGM observations is weaker than for Tmax, Tmin, and Rs, with an R2 value of 0.280 and RMSE and MAE of 1.469 m s−1 and 1.101 m s−1, respectively. The mean bias of about 0.867 m s−1 indicates that ERA5-Land overestimates near-surface wind speeds, suggesting that the estimated U2 by ERA5-Land should be used with bias-correction procedures rather than directly.

For RH, ERA5-Land and ground stations exhibit a moderate level of agreement, with a mean R2 of 0.646 and RMSE and MAE of roughly 10.770% and 8.457%, respectively. The mean bias of approximately 2.585% indicates a positive trend in ERA5-Land RH.

For P, ERA5-Land exhibits a high level of consistency with ground stations, with a mean R2 of 0.991 and RMSE and MAE on the order of 0.808 kPa and 0.629 kPa, respectively. The mean bias of 0.431 kPa indicates that ERA5-Land tends to slightly overestimate surface pressure, although the magnitude of the bias is relatively small, showing that ERA5-Land P can be used reliably for most climatic studies.

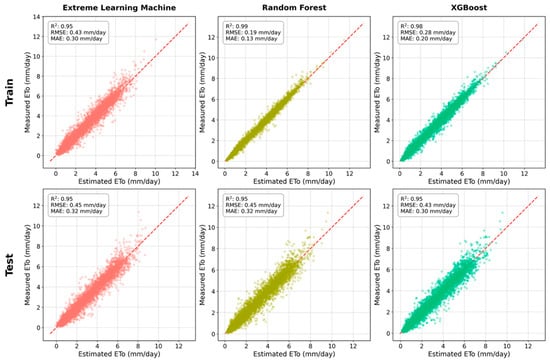

3.3. Performance of Machine Learning Models

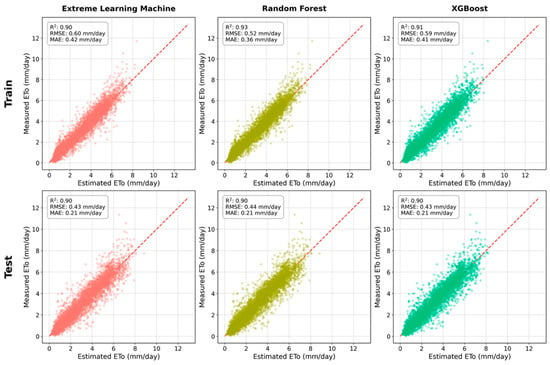

Due to ETo being physically non-negative, any negative ML predictions were processed by setting them to zero (). These negative values occurred only near-zero ETo conditions and represented a negligible fraction of the dataset. For transparency, the frequency of negative raw predictions is reported in Section 4.3. The estimated ETo values ranged from 0.12 to 12.17 mm d−1 for RF, from 0.0 to 12.64 mm d−1 for XGBoost, and from 0.0 to 10.19 mm d−1 for ELM. As shown in Figure 4, the XGBoost model provided the highest accuracy in the testing phase, whereas RF performed best during training. These models yielded the highest R2 values of 0.95 (testing) and 0.99 (training), along with the lowest RMSE and MAE values of 0.43 and 0.30 mm d−1 (testing), and 0.19 and 0.13 mm d−1 (training), respectively. Although ELM exhibited slightly lower performance, it still produced reasonably accurate ETo estimates with RMSE (0.43 mm d−1 for training and 0.45 mm d−1 for testing) and MAE (0.30 mm d−1 for training and 0.32 mm d−1 for testing) values, and a lower R2 value of 0.95 and 0.95 for training and testing, respectively.

Figure 4.

Performance assessment of ML models in estimating ETo using full dataset during training and testing phases.

For the ML models trained with limited data (only Tmax and Tmin), the estimated minimum and maximum ETo values were 0.13 and 10.01 mm day−1 for RF, 0.20 and 9.02 mm day−1 for XGBoost, and 0.0 and 8.45 mm day−1 for ELM, respectively (Figure 5). RF performed best for training (R2 = 0.93, RMSE = 0.52 mm day−1, and MAE = 0.36 mm day−1), while ELM was the most accurate for testing (R2 = 0.90, RMSE = 0.43 mm day−1, and MAE = 0.21 mm day−1). Although ELM was the best model for testing, other models also achieved similar performance, with R2 = 0.90, RMSE = 0.44 mm day−1, and MAE = 0.21 mm day−1 for XGBoost, and R2 = 0.90, RMSE = 0.44 mm day−1, and MAE = 0.21 mm day−1 for RF.

Figure 5.

Performance assessment of ML models in estimating ETo using limited dataset during training and testing phases.

The estimation accuracy of the ML models was further analyzed across the four primary climate types in Turkey. As summarized in Table 3, the models demonstrated varying levels of performance based on regional climatic characteristics. The Mediterranean climate zone exhibited the highest accuracy (R2 up to 0.96 for XGBoost), likely due to the consistent dominance of Rs as the primary driver of ETo. Similarly, the transitional climate showed very low error margins (RMSE: 0.41–0.42 mm/day). In contrast, the Black Sea climate yielded slightly higher errors and lower correlations (R2 approx. 0.91), which can be attributed to more frequent cloud cover and higher humidity levels that introduce more complexity into the ETo process. Despite these regional variations, all models remained robust, with R2 values exceeding 0.90 across all climate types.

Table 3.

ETo estimation performance metrics of the ML models used in this study under various climatic zones.

In addition to the estimation performance of the ML models used in this study, the computational cost was also evaluated. All experiments were conducted under identical hardware (MacBook M3 Pro laptop) and software conditions to ensure a fair comparison, and the results are presented in Table 4. The RF model became computationally expensive due to the large number of trees combined with significant depth (up to 25 levels) and complex splitting rules. Consequently, RF exhibited the longest training time among the evaluated models, with a total of 121.22 min. Even with a large number of trees and a broad hyperparameter search, XGBoost outperformed the other models in speed, completing its training in just 3.1 min, which was significantly faster than both RF and ELM. This speed demonstrates the efficiency of the gradient boosting implementation, which likely benefited from parallel processing and optimized tree construction. The ELM model took 27.42 min to train. While ELM is known for speed, the model was slowed down by large hidden layers (2000 neurons) and multiple activation functions. Consequently, ELM was significantly slower than XGBoost, though still considerably faster than RF. This underscores the critical trade-off between model complexity and training efficiency, which must be balanced against predictive performance in practical applications.

Table 4.

Hyperparameter optimization results, grid search ranges, and processing times for the developed ML models.

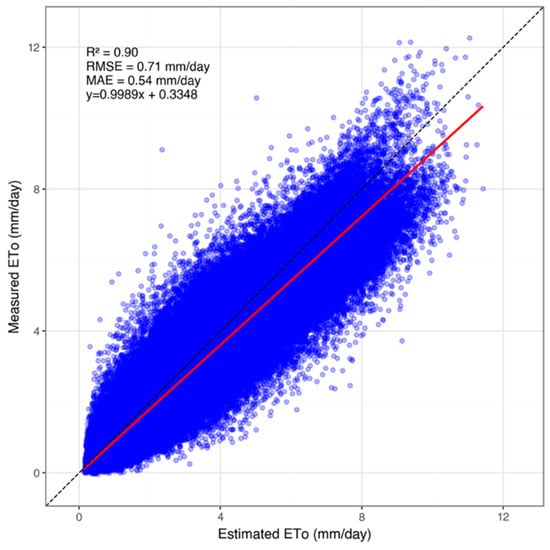

3.4. Evaluation of ETo Estimation with Reanalysis Data

To assess the reliability of ERA5-Land reanalysis data as a standalone estimator for ETo, performance metrics were calculated for three distinct temporal subsets: the full 30-year study period (1981–2010), the training period (1981–2000), and the testing period (2001–2010). These results are summarized in Table 5. For the full 30-year period, a strong linear relationship (R2 = 0.90) was observed between the ERA5-Land estimates and ground station observations. As shown in Figure 6, the slope of the regression line was 0.9989, indicating a robust estimation close to unity, while a slight positive intercept (0.3348) suggests a minor systematic overestimation by the model. In terms of error magnitude for the full dataset, the RMSE and MAE were calculated as 0.72 mm day−1 and 0.55 mm day−1, respectively. The positive bias of 0.31 mm day−1 confirms that ERA5-Land tends to yield slightly higher ETo values than observed. Descriptive statistics further reveal that ERA5-Land closely monitored the extremes; the maximum estimated ETo was 11.43 mm day−1, comparable to the observed maximum of 13.33 mm day−1, and minimum values were similarly consistent (0.14 vs. 0.04 mm day−1). To statistically evaluate the relationship between ground-based observations and ERA5-Land estimations, a paired Student’s t-test was performed. The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference between the two datasets (t = 275.41, df = 341,516, p < 0.001), with a mean difference of 0.31 mm/day.

Table 5.

Performance of direct ERA5-Land ETo estimates against ground observations across different temporal subsets.

Figure 6.

Comparison of estimated vs. measured ETo values. The dashed black line denotes the 1:1 agreement line. The solid red line represents the fitted linear regression line.

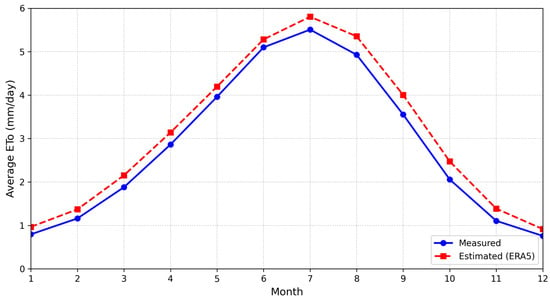

To better understand the ERA5-Land performance under different atmospheric conditions, the data were analyzed on both a monthly and a seasonal basis. Figure 7 presents the long-term mean daily ETo for both datasets across the year. The ERA5-Land product (red dashed line) closely follows the seasonal pattern of ET, reaching its maximum and minimum value in July (5.80 mm day−1) and December (0.91 mm day−1), respectively. Despite the high correlation, there is a systematic difference in certain months. As illustrated in Figure 7, this bias is not uniform over the year. It is minimal in winter months, with differences under 0.20 mm day−1, but increases substantially during the late-summer to autumn transition.

Figure 7.

Comparison of monthly average measured and estimated ETo values across the year.

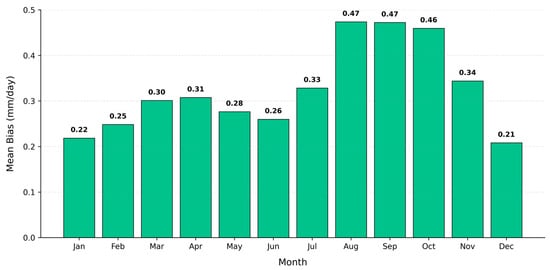

The analysis of monthly bias (Figure 8) shows that the high overestimation occurred in September (0.48 mm day−1), followed by August (0.45 mm day−1) and October (0.45 mm day−1). This pattern suggests that although ERA5-Land reproduces the peak summer radiation and temperature well, it tends to cool more slowly than the in situ station observations during the transition into autumn. Therefore, a higher ETo was estimated than that measured on the ground.

Figure 8.

Monthly average estimated ERA5-Land bias values compared to ground observations.

The seasonal performance metrics were presented in Table 6. The highest RMSE was observed in summer (0.93 mm day−1), which is consistent with the higher ETo during summer. In contrast, the greatest systematic bias was observed in autumn (0.41 mm day−1). Winter exhibited the lowest absolute error (RMSE: 0.46 mm day−1). The disparity between the low winter R2 of 0.25 and the high annual R2 of 0.90–0.96 does not indicate poor model performance but rather reflects the low amplitude of ETo values during winter. Given that daily ETo is negligible in this season, minor absolute errors (RMSE 0.46 mm day−1) significantly reduce the value of R2. Nevertheless, these errors are practically insignificant for agricultural planning.

Table 6.

Summary of seasonal accuracy assessment for ERA5-Land reanalysis data.

4. Discussion

4.1. Rs Calibration Using Rso Calculations

The calibration of Rs against theoretical Rso had a clear and measurable impact on the quality of ETo estimates across the 33 meteorological stations. By constraining measured Rs with physically based Rso values computed from the day of year, atmospheric water vapor, and station elevation following the study by Allen et al. [16], the QA/QC procedure substantially reduced biases in the radiation input and, in turn, in the derived ETo series. Several physical and observational factors likely contribute to these spatial differences. Inland and topographically complex stations are more prone to localized shading, orographic cloud formation, and frequent changes in aerosol loading and dust transport, all of which can alter the effective relationship between Rs and Rso even under clear-sky conditions [57,58]. Methodologically, the use of 60-day windows to perform the Rs calibration is a pragmatic choice, but it also introduces some important limitations. While a 60-day interval is long enough to smooth out short-lived weather anomalies and highlight sensor drift or persistent bias, it may not be optimal in all climates or seasons.

4.2. Performance of ERA5-Land Reanalysis Data

One of the main objectives of this study was to evaluate the capability of ERA5-Land reanalysis data to replace ground-based observations in Turkey. Results demonstrated a strong agreement for Rs, Tmax, and P (R2 > 0.90). These results align with several recent studies that have shown that ERA5-Land provides robust estimates for radiative and thermal parameters in Mediterranean climates [31,59,60]. In contrast, U2 showed poor agreement (R2 = 0.28) and a marked positive bias, and RH showed moderate agreement (R2 = 0.64); despite these aerodynamic inaccuracies, the agreement in the ETo was estimated from the ERA5-Land inputs, with the in situ calculations remaining high (R2 = 0.90). Multiple empirical studies demonstrate that the FAO-PM method can be used to estimate ETo accurately when U2 or RH is missing or inaccurate in humid [61], semi-arid [62] and Mediterranean [63] environments, and these results are also agreement with those of Sentelhas et al. [64], who found that the aerodynamic term in the PM equation has a lower sensitivity in certain inland or transitional climate zones compared to the radiative term. Finally, the results of Rosa et al. [35] indicated that ETo can be estimated accurately under Brazilian climate conditions even when specific reanalysis inputs exhibit lower accuracy. Consequently, ERA5-Land products remain a viable alternative for ETo estimation in similar climates. The significant difference (p < 0.001) obtained from the t-test requires careful interpretation. Faber and Fonseca [65] stated that studies with huge sample sizes, such as the one presented here (N > 340,000), are often identified as statistically significant due to minimal and practically insignificant deviations. This phenomenon, known as the ‘large sample size effect,’ suggests that the statistical significance may not necessarily imply a lack of model reliability. Furthermore, the mean difference of 0.31 mm/day is relatively small for regional ETo estimations. This minor deviation can be attributed to the 0.1° spatial resolution of ERA5-Land, which may not fully capture the complex topographic features and local micro-climates of Turkey. Additionally, the performance of the reanalysis data shows seasonal fluctuations, being more robust during high-radiation summer months compared to the more variable conditions of winter and transitional periods. Overall, despite the statistical difference, the high R2 values and low mean difference confirm that ERA5-Land is a viable alternative for ETo estimation in the region.

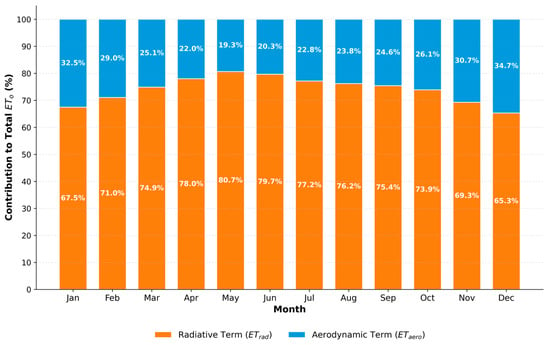

A deeper physical interpretation of the high correlation () achieved despite biases in U2 and RH was provided by analyzing the monthly physical decomposition of into its radiative (ETrad) and aerodynamic (ETaero) components (Figure 9). Analysis revealed that the radiative term contributed an average of 74.1% to total ETo. Seasonal fluctuations are shown by this contribution, with a peak of 80.7% reached in May and a minimum of 65.3% in December. Due to the high accuracy in solar radiation and temperature, which are the primary drivers for ETrad, as shown by ERA5-Land, the impact of aerodynamic input errors is significantly attenuated. This dominance effectively buffers the cumulative ETo estimation against the larger uncertainties found in U2 and RH modeling. These results suggest that for ETo monitoring in Mediterranean and Continental climates, ensuring the accuracy of radiative parameters is more critical than high-precision U2 data.

Figure 9.

Monthly variation in the percentage contribution of radiative (ETrad) and aerodynamic (ETaero) components to the total reference evapotranspiration (ETo) across the study area.

4.3. Evaluation of ML Models

To assess the performance of the three ML models used in this study (RF, XGBoost, and ELM), two scenarios were considered. In the first scenario, full data predictors were used. In the second, only Tmax and Tmin were used to reflect the ground stations that record only temperature.

Under the full dataset scenario, the XGBoost model achieved the best generalization performance on testing and resulted in the lowest errors overall. The RF model showed the best fit during the training phase but degraded more in testing, suggesting a tendency toward overfitting. In contrast, XGBoost presented a more favorable balance between bias and variance. The ELM model performed slightly worse than XGBoost and RF but remained robust, indicating that it can still learn most ETo variations when a full set of predictors is available, which is consistent with the ability of ELM to approximate complex nonlinear relationships using a single hidden layer.

The superior performance of XGBoost can be explained by the strong capability of gradient boosting ensembles to model nonlinear interactions among predictors and handle noisy data, while its built-in regularization helps to reduce overfitting [66]. Similar results were reported by Ge et al. [67], who found that XGBoost outperformed other ML models for ET estimation. Kaissi et al. [68] in Morocco and Lin et al. [69] in Taiwan also reported that XGBoost produced the most accurate ET estimations. Moreover, XGBoost has shown strong performance in other agricultural applications, including yield estimation in wheat [70], cotton [71], maize [72], disease detection [73], and soil moisture mapping [74].

The ML models also differed slightly in the upper range of the estimated ETo values (e.g., XGBoost up to ~12.6 mm d−1; RF up to ~12.2 mm d−1; and ELM up to ~10.2 mm d−1). These differences suggest distinct extrapolation behaviors at the tails of the ETo distribution, indicating that each model has its own strengths and weaknesses in capturing the full range of ETo values [75].

In the second scenario (reduced input), model accuracy slightly decreased but remained high. In this case, the models had to infer the effects of radiation and humidity indirectly from diurnal temperature range and seasonal patterns. The RF model, again, showed the best fit during training, while the ELM model presented the best performance in testing and was closely followed by the XGBoost and RF. This result suggests that ELM can still capture the main signal in ETo despite the reduced input setting.

While the FAO-56 PM equation is physically constrained to produce non-negative values, ML models function as unconstrained statistical regressors [76]. Consequently, when the actual ETo is near zero, the regression function may fluctuate slightly below zero due to residual noise. In the raw (unconstrained) outputs, XGBoost and ELM produced minor negative values (minimums of −0.05 and −0.60 mm day−1, respectively); these rare cases were clipped to 0 in the final reported ETo series. An analysis of the frequency of these occurrences reveals that they are rare and physically negligible. Negative predictions constituted only 0.0008% of the total test dataset for XGBoost and 0.052% for ELM.

The regional performance analysis shows that geographical location and climate type have a strong effect on the accuracy of ETo estimation. Higher accuracy in Mediterranean regions is consistent with previous studies and indicates that reanalysis-based ML models work well in clear sky and radiation-dominated conditions [77,78]. In contrast, the lower performance observed in the Black Sea region suggests that complex land–atmosphere interactions and local humidity conditions are still difficult to capture with ~9–11 km resolution datasets such as ERA5-Land [59,79].

In terms of computational efficiency, RF was the most expensive, reflecting its use of many deep trees with complex splits. ELM had intermediate computational cost due to its large hidden layers and multiple activation functions. XGBoost was the fastest of the three. These findings are consistent with the use of highly optimized and parallelized gradient boosting implementations, which make XGBoost suitable for large datasets and environments [80,81].

4.4. Seasonal Bias and Land-Atmosphere Coupling

An analysis of seasonal performance revealed a systematic positive bias in the ERA5-Land-based ETo estimates during the transition from summer to autumn (September–October). During this period, ERA5-Land tended to overestimate ETo compared to ground observations. This discrepancy highlights the impact of inaccuracies in the ERA5-Land meteorological data. While the ETo definition assumes a standardized reference surface with a constant surface resistance (70 s m−1), the uncertainties in surface variable estimations (e.g., U2 and RH) lead to deviations in the calculated evaporative demand, rather than a contradiction of the reference surface parameters themselves. The overestimation is primarily driven by the biases identified in the aerodynamic and radiative variables within the ERA5-Land dataset. ERA5-Land exhibits a systematic overestimation of U2 and a bias in RH errors during these months. In transitional seasons, reanalysis models often struggle to resolve local atmospheric stability and cloud dynamics, such as the increasing frequency of stratiform clouds or fog typical of the autumn season in Turkey [31,59]. Consequently, the model likely computes higher Rs and U2 than observed on the ground, leading to higher ETo values. This suggests that while ERA5-Land captures the general annual cycle, the local calibration of aerodynamic variables (U2 and RH) is crucial for accurate autumn irrigation planning. However, the integration of XGBoost as an ML layer effectively addresses these localized challenges. The superior performance of the XGBoost model is attributed to its ability to learn the complex, non-linear relationships between aerodynamic inputs and the high-quality radiative data of ERA5-Land. By assigning more weight to the dominant radiative components, the XGBoost model effectively filters out the noise from biased U2 and RH inputs. This ensures that the framework remains robust and physically grounded even during the transitional seasons where standalone reanalysis products exhibit their highest discrepancies, thereby providing a high-quality regional estimation tool.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Several alternative ETo estimation approaches have been tested in the literature. Empirical models like Hargreaves–Samani or Priestley–Taylor are widely used because they require fewer input variables. However, they often need local calibration to provide accurate results in different climates. Another common approach is using remotely sensed data (e.g., MODIS or Landsat). While satellite-based methods provide excellent spatial coverage, they are frequently limited by cloud cover and lower temporal frequency compared to reanalysis products. Our approach, combining ERA5-Land with ML models, bridges these gaps by providing continuous, high-temporal-resolution data that can be adapted to data-scarce regions. Despite the promising results, this study has certain limitations. First, the 0.1° (~9–11 km) spatial resolution of ERA5-Land might still be too coarse to capture microclimatic effects in regions with extremely complex topography or sharp elevation changes. Second, the performance of the ML models is directly linked to the quality of the ERA5-Land inputs. As observed in this study’s results, variables like U2 and RH showed lower correlation with ground data, which can introduce uncertainties in ETo estimation. Future studies could explore the use of downscaling techniques or the integration of deep learning architectures like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to better handle the temporal dynamics of meteorological variables.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluates the ML models for estimating ETo accurately across diverse climatic regions in Turkey, employing a comparative analysis between ground-based observations and ERA5-Land reanalysis data. A critical finding of this study is the necessity of rigorous data quality control, specifically the calibration of measured Rs against Rso curves, which significantly improved the reliability of ground observations, yielding high consistency across all stations with R2 ranging from 0.96 to 0.99. This step was essential for establishing a reliable starting point for the evaluation of the reanalysis data and the subsequent assessment of the ML models. The evaluation of the ERA5-Land dataset demonstrated a strong agreement with ground observations, which achieved R2 values exceeding 0.90. However, seasonal bias was identified during the transition from summer to autumn (September–October), where the reanalysis model tended to overestimate evaporative demand. In the comparative analysis of ML algorithms, XGBoost emerged as the superior model, providing the optimal balance between estimation accuracy, generalization capability, and computational efficiency. Despite the superior training performance of the RF model, it showed indications of overfitting and was computationally intensive, requiring longer training durations as a result of its complex ensemble of trees. Conversely, the ELM offered a robust alternative, particularly in scenarios limited to minimal meteorological inputs (Tmax and Tmin), where it slightly outperformed other models in testing accuracy. Ultimately, this research confirms that the integration of ERA5-Land reanalysis data with the XGBoost ML model provides a robust and high-precision framework for regional ETo estimation across diverse climates. Unlike standalone reanalysis products, this integrated approach successfully bridges the gap between coarse-resolution global data and local meteorological observations. Specifically, the XGBoost model acts as a non-linear error-correction tool that mitigates the systematic biases identified in ERA5-Land’s U2 and RH variables. By effectively prioritizing the highly accurate radiative signals from the reanalysis product, the XGBoost framework achieved superior performance (R2 = 0.95) and physical consistency across all evaluated climate zones. This integration proves that even in topographically complex regions, reanalysis–ML hybrid models provide a reliable alternative to ground-based observations for long-term hydrological and agricultural water management. Future research should focus on developing specific bias correction techniques for the aerodynamic variables in reanalysis data to mitigate seasonal overestimations and further refine water resource management strategies in topographically complex terrains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.T. and V.N.; methodology, E.T. and E.S.K.; software, E.T.; validation, E.T. and E.S.K.; formal analysis, E.T., V.N. and P.Š.; data curation, E.T. and V.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.T. and V.N.; writing—review and editing, E.T., V.N., P.Š. and E.S.K.; visualization, E.T. and V.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Turkish State Meteorological Service for the data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| ERA5 | Fifth-Generation ECMWF Reanalysis |

| ETo | Reference Evapotranspiration |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MGM | Turkish State Meteorological Service |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| P | Atmospheric Pressure |

| PM | Penman–Monteith |

| QA/QC | Quality Assurance/Quality Control |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| Rs | Solar Radiation |

| Rso | Theoretical Clear-Sky Solar Radiation |

| Tmax | Maximum Air Temperature |

| Tmin | Minimum Air Temperature |

| U2 | Wind Speed at 2 m height |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Meza, K.; Torres-Rua, A.F.; Hipps, L.; Kopp, K.; Straw, C.M.; Kustas, W.P.; Christiansen, L.; Coopmans, C.; Gowing, I. Relating spatial turfgrass quality to actual evapotranspiration for precision golf course irrigation. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e21446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanniarachchi, S.; Sarukkalige, R. A review on evapotranspiration estimation in agricultural water management: Past, present, and future. Hydrology 2022, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fernández, L.; Peña-Amaro, R.; Huanuqueño-Murillo, J.; Quispe-Tito, D.; Maldonado-Huarhuachi, M.; Heros-Aguilar, E.; Flores del Pino, L.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Quille-Mamani, J.; Torres-Rua, A. Water Use Efficiency in Rice Under Alternative Wetting and Drying Technique Using Energy Balance Model with UAV Information and AquaCrop in Lambayeque, Peru. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemek, B.; Küçüktopçu, E.; Fleitas Ortellado, M.G.; Simsek, H. Data-Driven Estimation of Reference Evapotranspiration in Paraguay from Geographical and Temporal Predictors. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunca, E. Evaluating the performance of the TSEB model for sorghum evapotranspiration estimation using time series UAV imagery. Irrig. Sci. 2024, 42, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.F.; Walker, W.R.; McKee, M. Forecasting daily potential evapotranspiration using machine learning and limited climatic data. Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 98, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connellan, G. Designing Irrigation Systems. In Water Use Efficiency for Irrigated Turf and Landscape; BioOne: Collingwood, Australia, 2013; pp. 205–239. [Google Scholar]

- Beguería, S.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Reig, F.; Latorre, B. Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) revisited: Parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 3001–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, D.J.; Huntington, J.L.; Mejia, J.F.; Hobbins, M.T. Improved seasonal drought forecasts using reference evapotranspiration anomalies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunca, E.; Köksal, E.S.; Çetin, S.; Ekiz, N.M.; Balde, H. Yield and leaf area index estimations for sunflower plants using unmanned aerial vehicle images. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Reference crop evapotranspiration from temperature. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1985, 1, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An approach toward a rational classification of climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaney, H.F.; Criddle, W.D. Determining Water Requirements in Irrigated Areas from Climatological and Irrigation Data; US Soil Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1950; Volume 96. [Google Scholar]

- Priestley, C.H.B.; Taylor, R.J. On the assessment of surface heat flux and evaporation using large-scale parameters. Mon. Weather Rev. 1972, 100, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J. Evaporation and surface temperature. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1981, 107, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Yang, G.; Xue, X.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Feng, H. Validation of two Huanjing-1A/B satellite-based FAO-56 models for estimating winter wheat crop evapotranspiration during mid-season. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 189, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle Júnior, L.C.G.d.; Vourlitis, G.L.; Curado, L.F.A.; Palácios, R.d.S.; Nogueira, J.d.S.; Lobo, F.d.A.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Rodrigues, T.R. Evaluation of FAO-56 procedures for estimating reference evapotranspiration using missing climatic data for a Brazilian tropical savanna. Water 2021, 13, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Afandi, G.; Abdrabbo, M. Evaluation of reference evapotranspiration equations under current climate conditions of Egypt. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 3, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaghi, A.R.; Majnooni-Heris, A.; Haghi, D.Z.; Mahtabi, G. Evaluate several potential evapotranspiration methods for regional use in Tabriz, Iran. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2013, 3, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Duffková, R.; Holub, J.; Fučík, P.; Rožnovský, J.; Novotný, I. Long-term water balance of selected field crops in different agricultural regions of the czech republic using fao-56 and soil hydrological approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citakoglu, H.; Cobaner, M.; Haktanir, T.; Kisi, O. Estimation of monthly mean reference evapotranspiration in Turkey. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, A.A.; Raeesi, M.; Longo-Minnolo, G.; Consoli, S.; Dyck, M. Daily reference evapotranspiration prediction in Iran: A machine learning approach with ERA5-land data. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanella, D.; Longo-Minnolo, G.; Belfiore, O.R.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Pappalardo, S.; Consoli, S.; D’Urso, G.; Chirico, G.B.; Coppola, A.; Comegna, A. Comparing the use of ERA5 reanalysis dataset and ground-based agrometeorological data under different climates and topography in Italy. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 42, 101182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, A.; Consoli, S.; Scicolone, B. Long-term climatic variability in Calabria and effects on drought and agrometeorological parameters. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.C.; Braga, R.P. Estimation of daily reference evapotranspiration from NASA POWER reanalysis products in a hot summer mediterranean climate. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droogers, P.; Allen, R.G. Estimating reference evapotranspiration under inaccurate data conditions. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2002, 16, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiantzas, J.D. Simplified forms for the standardized FAO-56 Penman–Monteith reference evapotranspiration using limited weather data. J. Hydrol. 2013, 505, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almorox, J.; Senatore, A.; Quej, V.H.; Mendicino, G. Worldwide assessment of the Penman–Monteith temperature approach for the estimation of monthly reference evapotranspiration. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 131, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, M.; Karic, B.; Pereira, L.S. Reference evapotranspiration estimate with limited weather data across a range of Mediterranean climates. J. Hydrol. 2013, 481, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarek, M.; Brissette, F.P.; Arsenault, R. Evaluation of the ERA5 reanalysis as a potential reference dataset for hydrological modelling over North America. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 2527–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulis, K.; Dosiadis, E.; Nikitakis, E.; Charalambopoulos, I.; Kairis, O.; Katsogiannou, A.; Palli Gravani, S.; Kalivas, D. Assessing AgERA5 and MERRA-2 Global Climate Datasets for Small-Scale Agricultural Applications. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Wu, L.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Y. Comparison of CLDAS and machine learning models for reference evapotranspiration estimation under limited meteorological data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, F.; Faraminán, A.; Rivas, R.; Orte, F. Prediction of evapotranspiration in the Pampean plain from CERES satellite products and machine learning techniques. Meteorologica 2023, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, S.L.K.; Souza, J.L.M.d.; Santos, A.A.d. Data from NASA Power and surface weather stations under different climates on reference evapotranspiration estimation. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2023, 58, e03261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbanzo, G.; Céspedes, J.; Temudo, M.; Ramos, T.B.; Cameira, M.d.R.; Pereira, L.S.; Paredes, P. Addressing Weather Data Gaps in Reference Crop Evapotranspiration Estimation: A Case Study in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Hydrology 2025, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ha, K.J.; Yeo, J.H. New drought projections over East Asia using evapotranspiration deficits from the CMIP6 warming scenarios. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wu, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, F. Medium-range forecasting of daily reference evapotranspiration across China using numerical weather prediction outputs downscaled by extreme gradient boosting. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Jiménez, J.A.; Estevez, J.; García-Marín, A. Reference evapotranspiration projections in Southern Spain (until 2100) using temperature-based machine learning models. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.B.; da Cunha, F.F.; Fernandes Filho, E.I. Exploring machine learning and multi-task learning to estimate meteorological data and reference evapotranspiration across Brazil. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.B.; da Cunha, F.F. New approach to estimate daily reference evapotranspiration based on hourly temperature and relative humidity using machine learning and deep learning. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 234, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, Ç.H.; Akyürek, Z. Evaluation of near-surface air temperature reanalysis datasets and downscaling with machine learning based Random Forest method for complex terrain of Turkey. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 71, 5256–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, S.; Çıtakoğlu, H. Modeling monthly reference evapotranspiration process in Turkey: Application of machine learning methods. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M. Performance of various gridded precipitation and temperature products against gauged observations over Turkey. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, İ. Türkiye Coğrafyası; Ege Üniversitesi Basımevi: İzmir, Turkey, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, M.; Çetinkaya, G.; Aydın, S. Köppen-Geiger iklim sınıflandırmasına göre Türkiye’nin iklim tipleri. Coğrafya Derg. 2017, 35, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkerly, C.; Huntington, J.L.; McEvoy, D.; Morway, A.; Allen, R.G. agweather-qaqc: An interactive Python package for quality assurance and quality control of daily agricultural weather data and calculation of reference evapotranspiration. J. Open Source Softw. 2024, 9, 6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Dietrich, J. Developing ensemble mean models of satellite remote sensing, climate reanalysis, and land surface models. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 150, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirsoy, H.; Küçüktopçu, E.; Doğan, D.E. Novel machine learning approaches for accurate leaf area estimation in apples. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2025, 67, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunca, E.; Köksal, E.; Akay, H.; Öztürk, E.; Taner, S. Novel machine learning framework for high-resolution sorghum biomass estimation using multi-temporal UAV imagery. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 13673–13688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçüktopçu, E.; Cemek, B.; Simsek, H. Machine Learning and Wavelet Transform: A Hybrid Approach to Predicting Ammonia Levels in Poultry Farms. Animals 2024, 14, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawagreh, K.; Gaber, M.M.; Elyan, E. Random forests: From early developments to recent advancements. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2014, 2, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- İrik, H.A.; Ropelewska, E.; Çetin, N. Using spectral vegetation indices and machine learning models for predicting the yield of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) under different irrigation treatments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 109019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, M.; Stöckli, R.; Zardi, D.; Tetzlaff, A.; Wagner, J.; Belluardo, G.; Zebisch, M.; Petitta, M. The HelioMont method for assessing solar irradiance over complex terrain: Validation and improvements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 152, 603–613. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, L.F.; Folini, D.; Chtirkova, B.; Wild, M. Causes for decadal trends in surface solar radiation in the alpine region in the 1981–2020 period. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD039998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M. Accuracy assessment of temperature trends from ERA5 and ERA5-Land. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koudahe, K.; Djaman, K.; Adewumi, J.K. Evaluation of the Penman–Monteith reference evapotranspiration under limited data and its sensitivity to key climatic variables under humid and semiarid conditions. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2018, 4, 1239–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.d.; Silva, T.d.; Souza, L.d.; Moura, M.d.; Diniz, W.d.S.; Souza, C.d. Avaliação do método de Penman Monteith FAO 56 com dados faltosos e de métodos alternativos na estimativa da evapotranspiração de referência no Submédio Vale do São Francisco. Rev. Bras. De Geogr. Física 2015, 8, 1644–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, D.L.; Can, M.E. Reference evapotranspiration estimate with missing climatic data and multiple linear regression models. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentelhas, P.C.; Gillespie, T.J.; Santos, E.A. Evaluation of FAO Penman–Monteith and alternative methods for estimating reference evapotranspiration with missing data in Southern Ontario, Canada. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, J.; Fonseca, L.M. How sample size influences research outcomes. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2014, 19, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibindi, R.; Mwangi, R.W.; Waititu, A.G. A boosting ensemble learning based hybrid light gradient boosting machine and extreme gradient boosting model for predicting house prices. Eng. Rep. 2023, 5, e12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Gong, X.; Sun, H. Prediction of greenhouse tomato crop evapotranspiration using XGBoost machine learning model. Plants 2022, 11, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaissi, O.; Belaqziz, S.; Kharrou, M.H.; Erraki, S.; El Hachimi, C.; Amazirh, A.; Chehbouni, A. Advanced learning models for estimating the spatio-temporal variability of reference evapotranspiration using in-situ and ERA5-Land reanalysis data. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 1915–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Lai, S.-Y.; Lin, Y.-J. Reanalysis-assisted AI framework for regional pan evaporation estimation in Taiwan without ground-based meteorological observations. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 62, 102863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Pradhan, B.; Chakraborty, S.; Behera, M.D. Winter wheat yield prediction in the conterminous United States using solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence data and XGBoost and random forest algorithm. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.T.; Ge, W.; Li, J.; Rehman, S.U.; Imran, A.; Sharaf, M.A.F.; Haider, S.M. An Ensemble Machine Learning Framework for Cotton Crop Yield Prediction Using Weather Parameters: A Case Study of Pakistan. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 124045–124061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Mo, X. Crop yield time-series data prediction based on multiple hybrid machine learning models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, W.; Dong, Y.; Ma, H.; Wu, K.; Guo, A. Combining random forest and XGBoost methods in detecting early and mid-term winter wheat stripe rust using canopy level hyperspectral measurements. Agriculture 2022, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunca, E.; Köksal, E.S.; Çetin Taner, S. Integration of UAV images and ensemble learning for root zone soil moisture estimation in sorghum. Irrig. Sci. 2026, 44, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuveneers, D.; Tsingenopoulos, I.; Joosen, W. Resource usage and performance trade-offs for machine learning models in smart environments. Sensors 2020, 20, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.L.; Gentine, P.; Reichstein, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wen, Y.; Lin, C.; Li, X.; Qiu, G.Y. Physics-constrained machine learning of evapotranspiration. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 14496–14507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgouletis, N.; Gkavrou, M.; Baltas, E. Comparison of empirical ETo relationships with ERA5-land and in situ data in Greece. Geographies 2023, 3, 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, M.; De Caro, D.; Cannarozzo, M.; Provenzano, G.; Ciraolo, G. Evaluation of daily crop reference evapotranspiration and sensitivity analysis of FAO Penman-Monteith equation using ERA5-Land reanalysis database in Sicily, Italy. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 295, 108732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of ERA5, ERA5-Land, GLDAS-2.1, and GLEAM potential evapotranspiration data over mainland China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 51, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.; Caldeira, F.; Cruz, T.; Simões, P. Combining k-means and xgboost models for anomaly detection using log datasets. Electronics 2020, 9, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, S.; Sharma, Y.; Taheri, J. Towards Generic Failure-Prediction Models in Large-Scale Distributed Computing Systems. Electronics 2025, 14, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.