Abstract

Drip irrigation burial depth is a critical management factor for saline-alkali agriculture, yet its mechanisms of influencing crop productivity through soil–microbe–plant interactions remain poorly understood. To explore the regulatory effects of drip irrigation burial depth on the growth and rhizosphere microenvironment of dryland wheat in saline-alkali soil, three treatments (no irrigation control, CK; 5 cm shallow-buried drip irrigation, T5; 25 cm deep-buried drip irrigation, T25) were set up, with soil physicochemical properties, microbial community characteristics, and crop yield analyzed. The results showed that drip irrigation significantly improved soil environment and yield, and T25 exhibited superior comprehensive benefits: soil electrical conductivity was reduced by 63%, organic matter content increased by 44%, and water-salt status was significantly optimized; meanwhile, microbial community structure was altered and root nutrient uptake capacity was enhanced, ultimately achieving a yield of 5347.1 kg ha−1, 55.0% higher than CK. In conclusion, 25 cm deep-buried drip irrigation may provide advantages for wheat cultivation primarily through improved water distribution, desalination, and soil structure enhancement.

1. Introduction

Saline-alkaline soil degradation threatens global food security as arable land shrinks and population grows. Globally, 1.5 × 106 hectares of land become unfit for cultivation annually due to salinization [1], and in China, saline-alkaline land with agricultural development potential accounts for over 10% of total cultivated area, distributed across Northwest, Northeast, North, and Central China [2]. The Bohai Bay coastal region exemplifies this challenge, where 60% of arable land faces moderate to severe salinization, yet holds significant potential for food production if appropriate salt-tolerant crops and precision irrigation strategies can be deployed. Harnessing these marginal soils through integrated agronomic management has become imperative for regional food security.

Subsurface drip irrigation (SDI) has emerged as a promising technology for reclaiming saline-alkaline lands, offering dual benefits of water conservation and soil amelioration. This precision irrigation method achieves 30–50% water savings while improving fertilizer-use efficiency by 25–60% in various crops [3]. Beyond resource efficiency, SDI creates a localized wetted bulb that drives salts downward, achieving optimal leaching at a soil matric potential of −5 kPa [4]. In moderately to severely saline coastal soils, this results in 15–30% salinity reduction in the 0–20 cm layer, with maximum effect within 15 cm of the emitter [5,6]. Beyond salt removal, SDI also significantly improves soil physicochemical properties [7]. In addition to salt leaching, experimental data show that it increases soil organic matter and available nitrogen content by 6–8% in the 10–20 cm soil layer [8].

The effectiveness of SDI in saline soil reclamation depends critically on emitter burial depth, which creates distinct soil microenvironments that shape microbial community assembly and function. Shallow-buried drip irrigation (5 cm) significantly enhances bacterial and fungal α diversity (Shannon and Simpson indices) and yields the highest number of bacterial OTUs [9]. In contrast, deep-buried drip (25 cm) creates a distinct separation in community structure from shallow-buried treatments, as revealed by beta diversity analysis in maize trials [9]. Functional gene prediction further indicates that burial depth drives divergent microbial functional traits: deep-buried drip significantly enriches genes linked to nitrogen cycling (nitrate respiration, nitrogen respiration), whereas shallow-buried drip favors genes for aerobic heterotrophic metabolism [10]. However, these mechanistic insights derive primarily from studies on maize and cotton in non-saline soils, leaving uncertainty about whether similar patterns govern wheat responses in coastal saline-alkaline systems where water–salt dynamics differ fundamentally.

Despite these advances, critical knowledge gaps remain regarding the integrated effects of drip irrigation burial depth on the soil–microbe–crop continuum in saline-alkaline systems. Most existing studies focus on single factors (soil salinity or crop yield) without examining their interactions [11]. Additionally, the majority are short-term experiments (≤2 years) that cannot capture long-term ameliorative effects [12]. Most importantly, contradictory findings regarding optimal burial depth persist: some studies report superior yields with shallow burial due to improved surface soil conditions, while others favor deep burial for sustained salt leaching and reduced waterlogging risk. These inconsistencies likely stem from crop-specific responses and site-specific soil conditions that remain poorly characterized. Most critically, the mechanisms by which burial depth reshapes microbial functional guilds to alter soil biogeochemical cycles and ultimately affect wheat productivity in saline soils remain unknown. Resolving these gaps is essential for evidence-based SDI design in coastal saline-alkaline wheat systems, where irrigation efficiency determines both economic viability and ecological sustainability.

As a newly-bred cultivar of common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) independently developed in Hebei Province, Jiemai 19 was designated as a leading wheat variety in the province in 2022, providing an ideal model system for this study. This cultivar uniquely combines high salinity tolerance (yielding >250 kg/ha−1 in saline-alkali soils) with dryland adaptation [13]. This combination allows us to examine SDI burial depth effects without the confounding influence of excessive irrigation on soil microbial communities—a problem in conventional wheat varieties that require frequent watering in saline soils, making a mechanistic understanding of its response to SDI management practically urgent for regional agricultural development.

We hypothesize that SDI burial depth drives wheat productivity through distinct mechanisms: shallow burial (5 cm) enhances productivity by maximizing topsoil microbial diversity and nutrient cycling, but suffers from higher evaporative losses; deep burial (25 cm) achieves superior yields through synergistic effects of enhanced desalination, directional enrichment of nitrogen-cycling microbes, and precision water–nutrient delivery to the root zone. We predict deep burial will optimize the chain mechanism of “soil microenvironment improvement—microbial community optimization—crop growth promotion”, balancing ecological and production benefits. To test this, we established a field experiment with three treatments (T25, T5, CK) coupled with high-throughput sequencing, functional gene prediction, and comprehensive soil analyses to elucidate depth-dependent mechanisms in the saline-alkaline soil–microbe–wheat system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Experimental Area

The field experiment was conducted from October 2024 to June 2025 in Lizicha Village, Changguo Town, Huanghua City, Cangzhou City, Hebei Province, China (117°15′08.94″ E, 38°16′17.29″ N, elevation ~8 m). The experimental site is located in the core area of Bohai Bay coastal saline-alkaline farmland. The site experiences a warm temperate semi-humid monsoon climate [14]. Meteorological data were recorded at a Huanghua National Basic Meteorological Station, installed 50 m from the experimental plots. During the wheat growing season (October–June), the average temperature was 9.1 °C, the total evapotranspiration (calculated via the Penman–Monteith method) was 510 mm, the effective precipitation was 175 mm, the monthly average relative humidity ranged from 55% to 68%, and the total precipitation during the growing season was 186 mm. The location of the experimental area is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of the experimental site.

Soil at the experimental site is classified as saline FAO classification with a sandy loam texture (sand 62%, silt 26%, clay 12%). Soil salt content (%) was determined using the electrical conductivity method [15]. Pre-experimental soil physicochemical properties are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pre-experimental soil pH, electrical conductivity, and salt content.

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

The experimental subject was the dryland saline-alkaline wheat cultivar “Jiemale 19”, whose growth period ran from mid to late October to early June of 2025, with a total growing period of approximately 230 days. Before wheat sowing (early October 2024, completed prior to the installation of the subsurface drip irrigation system), the experimental field was subjected to deep tillage with a rotary tiller at a depth of 25 cm. This practice was designed to break the plow pan, improve soil permeability, and homogenize the soil structure of the saline-alkali field. After deep tillage, the field was leveled, followed by the installation of subsurface drip irrigation pipes (buried at the experimentally designed depth of 25 cm) and subsequent wheat sowing. Wheat was mechanically drilled at a row spacing of 20 cm with a seeding rate of 600 kg ha−1. The experiment was established as a randomized complete block design with three treatments and three replicate blocks, a total of nine experimental plots. Each experimental plot measured 6 m × 10 m (60 m2) with 1.5 m buffer zones between adjacent plots to prevent lateral water and salt movement. Three treatments (no irrigation control, CK; 5 cm shallow-buried drip irrigation, T5; 25 cm deep-buried drip irrigation, T25) were set up. The lateral spacing was 60 cm (one lateral served three wheat rows), the emitter spacing was 20 cm, and the emitter discharge ranged from 2.5 to 3.0 L h−1. Irrigation was scheduled at five critical growth stages (regreening, jointing, heading, flowering, and filling), giving a total of five irrigations, each applying 40 mm of water [16]. Each irrigation event typically required 4 h. Topdressing was scheduled at the jointing stage (15 March 2025), with fertigation conducted synchronously with irrigation at this stage. Urea (nitrogen content 46%, highly water-soluble, suitable for drip irrigation) was used as the nitrogen fertilizer, with a pure nitrogen application rate of 165 kg ha−1, equivalent to a precise application of 2.2 kg urea per experimental plot. Combined with an irrigation quota of 40 mm, this ensured uniform infiltration of nitrogen into the root zone with water. Fertilization was performed once during the entire growing season, with the same regime applied to all treatments. The experimental design is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the experimental design.

2.3. Determination Indicators and Methods

2.3.1. Soil Physicochemical Property Determinations

Soil samples were collected post-harvest on 5 June 2025 (early June). Based on the grid sampling method (a systematic random sampling criterion adapted to the plot-scale experiment), three sampling points were randomly selected within each plot. At each point, soil samples from the 0–40 cm layer were taken using a soil auger (5 cm diameter). The soil samples from the three sampling points in the same plot were mixed thoroughly to form one composite bulk sample to ensure representativeness, resulting in a total of 9 bulk samples corresponding to the 9 experimental plots. Plant residues and gravel (>2 mm) were manually removed from each bulk sample. The determined indicators are as follows:

Soil electrical conductivity (EC): Determined in accordance with the national standard Method for Determination of Soil Electrical Conductivity (Electrode Method) [17]. Briefly, 20.00 g of air-dried soil sample passed through a 2 mm sieve was weighed, and experimental water (electrical conductivity ≤ 0.2 mS m−1) at 20 ± 1 °C was added at a soil-to-water ratio of 5:1. After oscillating for 30 min and standing for filtration, the electrical conductivity of the filtrate was measured using a calibrated conductivity meter at 25 ± 1 °C.

Soil pH: Determined in accordance with the national standard Method for Determination of Soil pH (HJ 962-2018) [18]. Using the same soil–water suspension prepared for EC determination (soil-to-water ratio 5:1), the pH value was measured with a calibrated pH meter after standing for an additional 10 min to ensure the suspension was stable.

Soil organic matter (OC): Determined using external heating with concentrated sulfuric acid and potassium dichromate [19].

Total nitrogen (TN): Determined by the Kjeldahl method [20].

Total potassium (TK): Determined by the sodium hydroxide melting-flame photometry method [21].

2.3.2. Collection of Rhizosphere Soil Samples

Samples were collected after the harvest of dryland saline-alkaline wheat. Representative sampling points were selected in each experimental plot using the five-point sampling method. At each sampling point, healthy plants with consistent growth status were chosen. After carefully excavating the plants with their roots intact, debris such as litter and gravel mixed on the plant surface was removed. The loosely attached non-rhizosphere soil around the roots was gently shaken off, and the soil tightly adhering to the root surface was scraped off using a sterile brush sterilized by autoclaving, which was designated as the rhizosphere soil sample. The soil samples from the five points were mixed to a total weight of approximately 200 g, placed into sterile centrifuge tubes, quickly frozen with dry ice, and transported to the laboratory within 48 h for DNA extraction. Samples were stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. A total of three treatments were set up in this study: CK, T5, and T25. Each treatment included three biological replicates, resulting in 9 rhizosphere soil samples in total.

2.3.3. Soil Microbial DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

Total soil microbial DNA was extracted using the Solar bio D2600 Soil Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), with strict adherence to the kit’s instructions. Briefly, 0.25 g of frozen soil sample was weighed, and microbial cells were mechanically disrupted using grinding beads (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Humic acid and other impurities in the soil were removed using the humus adsorption material provided with the kit, and finally, DNA was eluted with 30 μL of elution buffer.

The integrity of DNA fragments was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the purity of DNA was determined using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The OD260/OD280 ratio was controlled within the range of 1.8–2.0 to ensure that the DNA quality met the requirements for subsequent PCR amplification. For the V3-V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene in bacterial communities, PCR amplification was performed using specific primers (forward primer F: ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA; reverse primer R: GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT). After verifying the amplified products by agarose gel electrophoresis, purification was carried out using the magnetic bead method. Purified amplicons were normalized for library construction, and paired-end high-throughput sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform by Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd., (Beijing, China) to obtain raw reads.

2.3.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

Raw paired-end reads were merged, quality-filtered, and chimera-checked using QIIME2 v2022.8. High-quality sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity threshold using VSEARCH (v2.22.1). Taxonomic assignment was performed using the Silva database (Release 138.1) with a confidence threshold of 0.8. OTUs with <10 total reads across all samples were removed. The OTU table was rarefied to the minimum library size for downstream diversity analyses.

Alpha diversity indices (Chao1, ACE, Shannon, Simpson, phylogenetic diversity) were calculated using QIIME2. Shannon rarefaction curves and OTU Venn diagrams were generated to verify sequencing depth sufficiency and show OTU distribution characteristics among treatments. Coverage values were calculated to assess sequencing completeness.

Beta diversity was assessed using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) were performed for visualization of community structure differences among treatments.

For taxonomic composition analysis, the top 10 dominant taxa at the phylum level and the top 15 dominant taxa at the genus level (by relative abundance) were selected for stacked bar chart visualization. Biomarker taxa among treatments were identified using Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe).

Bacterial community functions were predicted using the FAPROTAX database v1.2.4, which links cultivable microbial genera to empirically validated biogeochemical functions. The genus-level OTU table (Silva 138.1 annotation) was used as input, and functional groups related to nitrogen cycling (e.g., nitrification, denitrification, nitrogen fixation, nitrate reduction) and carbon cycling were extracted.

2.3.5. Grain Yield and Aboveground Biomass Determination

We harvest the middle 3 rows of each plot, measure the row length to calculate the harvested area, thresh and remove impurities immediately, determine grain moisture content with a calibrated tester, and convert to 13% standard moisture content for yield calculation.

For yield components and aboveground biomass determination, randomly select 30 uniform plants from each plot, separate them into glume, stem, and grain fractions. Deactivate all fractions at 105 °C for 30 min and dry to constant weight at 65 °C. Weigh the total dry weight of the three fractions to determine the aboveground biomass of individual plants. Measure the dry weight of each fraction separately for yield component analysis; determine 1000-grain weight with 3 replicates of pure dried grains, re-test if replicate weight difference exceeds 3%, and take the average.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

Data collation was performed using Excel 2019. Statistical analyses were conducted using multiple software packages: QIIME2 v2022.8 for alpha diversity calculations, R v4.2.2 (vegan, pheatmap, ggplot2 packages) for multivariate analyses and visualization, SPSS 26.0 for ANOVA, and STAMP v2.1.3 for differential abundance testing.

Soil physicochemical properties and crop performance: One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS 26.0 to test for significant differences among treatments. When ANOVA indicated significant treatment effects (p < 0.05), means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range test at the 5% significance level.

Microbial alpha diversity indices: One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test was used to compare species richness (OTU, ACE, Chao1) and diversity indices (Shannon, Simpson, phylogenetic diversity) among treatments. For non-normally distributed data (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.05), the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post-hoc test was applied.

Microbial beta diversity: Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 999 permutations was performed using the vegan package in R to test for significant differences in community composition among treatments based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices. Pairwise PERMANOVA tests with Benjamini–Hochberg correction were conducted to identify specific treatment differences.

Differential abundance and biomarker identification: Pairwise comparisons of bacterial taxa between treatments were conducted using STAMP v2.1.3 software with the two-group analysis module. For taxa with >20 total counts, the G-test (with Yates’ correction) was applied; for low-abundance taxa (<20 counts), Fisher’s exact test was used. p-values were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR method, with corrected p < 0.05 considered significant. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was performed to identify biomarker taxa among treatments, with an LDA score threshold > 2.0 and alpha value of 0.05 (Kruskal–Wallis test).

Redundancy analysis (RDA): RDA was performed using the vegan package in R to examine relationships between microbial community composition (at phylum and genus levels) and soil environmental variables (EC, TN, TK, OC, pH). The significance of RDA axes was tested using permutation tests with 999 permutations. Environmental variables were standardized, and forward selection was used to identify significant explanatory variables (p < 0.05).

Correlation analyses: Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to assess linear relationships between continuous variables (e.g., grain yield vs. soil/microbial parameters). For non-normally distributed data (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.05), Spearman’s rank correlation was used instead. Correlation significance was tested at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 levels. Spearman’s rank correlation heatmaps were generated for bacterial taxa (phylum and genus levels) versus soil environmental factors using the pheatmap package in R with hierarchical clustering.

Functional prediction: Differences in functional group abundances among treatments were tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR (false discovery rate) correction to control for multiple comparisons. Functional categories with corrected p < 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals not crossing zero were considered significantly different.

Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) for n = 3 biological replicates. All figures were generated using Origin 2021 software and R (ggplot2 and vegan packages).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths on Soil Physicochemical Properties

Soil physicochemical properties differed significantly among treatments (Figure 3). Drip irrigation burial depth significantly affected soil electrical conductivity (EC), total nitrogen (TN), total potassium (TK), and organic carbon (OC) content (p < 0.05), but not soil pH (p > 0.05). After harvest, EC values in the 0–40 cm soil layer were 13,500 μs cm−1 (CK), 11,000 μs cm−1 (T5), and 5000 μs cm−1 (T25), representing 18.5% and 63.0% reductions compared to CK, respectively. T25 demonstrated superior desalination efficiency. Soil pH ranged from 8.8 to 9.2 with no significant differences among treatments. Soil organic carbon (OC) content increased with burial depth: 6.8 g kg−1 (CK), 8.5 g kg−1 (T5, 25.0% higher than CK), and 9.8 g kg−1 (T25, 44.1% higher than CK). In contrast, total nitrogen (TN) content was highest in T5 (150 mg kg1, 11.1% higher than CK), followed by CK (135 mg kg−1) and T25 (105 mg kg−1, 22.2% lower than CK). Total potassium (TK) showed similar levels in CK (230 mg kg−1) and T5 (240 mg kg−1), but was significantly lower in T25 (120 mg kg−1, 47.8% reduction).

Figure 3.

Soil electrical conductivity (EC) and nutrient contents in different treatments after wheat harvest. (a) Soil electrical conductivity (EC); (b) pH; (c) Total nitrogen (TN) content; (d) Total potassium (TK) content; (e) Organic carbon (OC) content. Note: CK, control (no irrigation); T5, shallow drip irrigation (5 cm burial depth); T25, deep drip irrigation (25 cm burial depth). Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05, Duncan’s multiple range test). Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3).

3.2. Effects of Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths on Soil Microbial Communities

3.2.1. Alpha Diversity Characteristics of Microbial Communities

Alpha diversity indices varied significantly among treatments, with distinct patterns across metric types (Table 2). Species richness indices (OTU, ACE, Chao1) consistently ranked as T5 > T25 > CK, with all differences being significant (p < 0.05). T5 exhibited 74–75% higher species richness than CK (OTU: 4072 compared with 2324; ACE: 4112 compared with 2362; Chao1: 4075 compared with 2332), while T25 showed 34–36% increases (OTU: 3152; ACE: 3175; Chao1: 3155).

Table 2.

Alpha diversity indices of rhizosphere microbial communities under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments.

Community diversity indices followed similar trends with smaller magnitude changes. The Shannon index increased from 9.26 (CK) to 10.65 (T5, 15.0% higher) and 10.45 (T25, 12.9% higher), with all treatments significantly different (p < 0.05). The Simpson index was significantly higher in irrigation treatments (0.998) than in CK (0.995), though T5 and T25 did not differ. In contrast, phylogenetic diversity (PD_whole_tree) ranged narrowly from 29.23 to 29.68 with no significant differences (p > 0.05), indicating that irrigation increased species number and evenness without altering phylogenetic breadth.

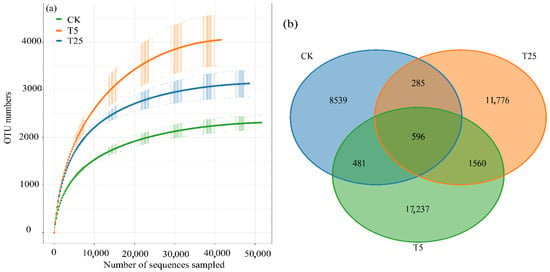

3.2.2. Rarefaction Curves and OTU Distribution Characteristics

Rarefaction curves for all treatments approached asymptotes beyond 30,000 sequences (Figure 4a), confirming sufficient sequencing depth to capture bacterial diversity. Observed OTU richness at saturation was 2324 (CK), 4072 (T5), and 3152 (T25), representing 75.2% and 35.6% increases in T5 and T25 relative to CK. Venn diagram analysis revealed distinct OTU distribution patterns among treatments (Figure 4b). Of 40,474 total OTUs, only 596 (1.5%) constituted a core microbiome shared by all treatments. Treatment-specific OTUs were most abundant in T5 (17,237, 42.6% of total), followed by T25 (11,776, 29.1%) and CK (8539, 21.1%). Between-treatment comparisons showed asymmetric sharing patterns. T5 and T25 shared 2156 OTUs (5.3% of total, including 1560 exclusives to this pair plus 596 core OTUs). In contrast, CK shared only 1077 OTUs (2.7%) with T5 (481 exclusive plus 596 core) and 881 OTUs (2.2%) with T25 (285 exclusive plus 596 core).

Figure 4.

Rarefaction curves and OTU distribution patterns of rhizosphere microbial communities under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments. (a) Rarefaction curves showing OTU richness saturation; (b) Venn diagram showing shared and unique OTUs among treatments. Notes: OTU, operational taxonomic unit; CK, control (no irrigation); T5, shallow drip irrigation (5 cm burial depth); T25, deep drip irrigation (25 cm burial depth). Rarefaction curves indicate sufficient sequencing depth when plateauing. Numbers in the Venn diagram represent OTU counts.

3.2.3. Beta Diversity and Structural Differentiation of Microbial Communities

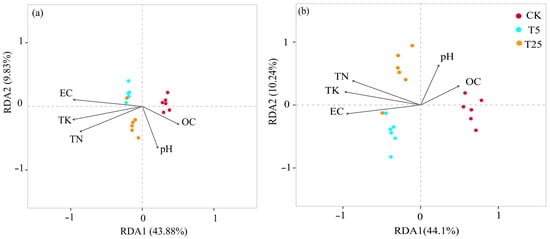

Redundancy analysis (RDA) at the phylum level (Figure 5a) showed that RDA1 and RDA2 explained 43.88% and 9.83% of community variation, respectively (total: 53.71%). The vectors of EC and Total potassium (TK) were oriented toward the T5, while organic matter (OC) and pH vectors were oriented toward the CK.

Figure 5.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) of rhizosphere microbial communities and soil environmental factors under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments at phylum (a) and genus (b) levels. Notes: EC, electrical conductivity; TN, total nitrogen; TK, total potassium; OC, organic carbon; CK, rainfed control (no irrigation); T5, shallow drip irrigation (5 cm burial depth); T25, deep drip irrigation (25 cm burial depth). Arrows represent environmental factor vectors; arrow length indicates the strength of association with community variation. RDA1 and RDA2 represent the first and second axes of redundancy analysis, with percentages indicating explained variance.

At the genus level (Figure 5b), RDA1 and RDA2 explained 44.1% and 10.24% of variation, respectively (total: 54.34%). The pH and OC vectors were oriented toward the CK, while EC, Total Nitrogen (TN), and TK vectors were oriented toward the T5 and T25.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) revealed strong associations between microbial community composition and soil physicochemical variables (Figure 5). At the phylum level (Figure 5a), RDA1 and RDA2 explained 43.88% and 9.83% of community variation, respectively (53.71% total). Treatments showed clear spatial separation: CK samples clustered on the right, T5 in the upper-left, and T25 in the lower-central region. The EC vector was oriented toward T5 in the upper-left, while the TK and TN vectors were oriented leftward toward both T5 and T25. In contrast, the OC and pH vectors were oriented rightward toward CK.

At the genus level (Figure 5b), RDA1 and RDA2 explained 44.1% and 10.24% of variation (54.34% total), with more pronounced treatment separation. CK samples clustered on the right, T5 in the lower-left, and T25 in the upper-left. The pH and OC vectors were oriented toward CK on the right, while the EC vector was oriented toward T5 in the lower-left. The TN and TK vectors were oriented toward the left and upper-left, respectively, showing associations with both T5 and T25, though TN aligned more closely with T25 and TK with the intermediate space between treatments.

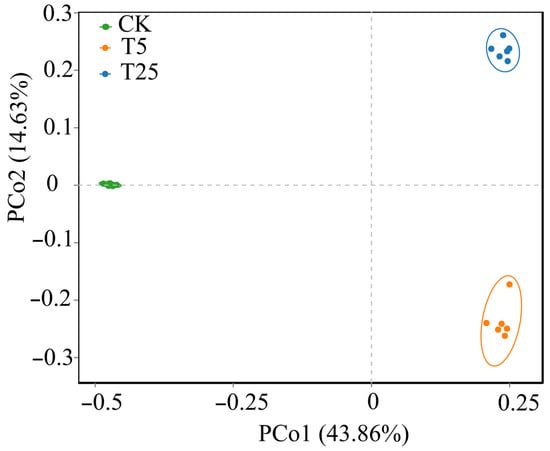

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity revealed significant compositional differences among treatments (Figure 6). The first two principal coordinates (PCo1 and PCo2) cumulatively explained 58.49% of community variation (43.86% and 14.63%, respectively), indicating that the majority of compositional variance was captured by the ordination. Three distinct, non-overlapping clusters emerged, corresponding to the three treatments. The primary axis of variation (PCo1) clearly separated CK samples from both irrigation treatments, with no overlap between CK and T5/T25. This pattern indicates that irrigation fundamentally altered bacterial community composition. Along the secondary axis (PCo2), T5 and T25 samples occupied distinct regions of ordination space, demonstrating that burial depth further shaped community assembly beyond the primary irrigation effect. The complete separation of all three treatment clusters is confirmed by non-overlapping 95% confidence ellipses.

Figure 6.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of rhizosphere microbial communities under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity. Notes: CK, control (no irrigation); T5, shallow drip irrigation (5 cm burial depth); T25, deep drip irrigation (25 cm burial depth). Colored dots represent individual samples; ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals. PCo1 and PCo2 explain 43.86% and 14.63% of community variation, respectively (58.49% cumulative).

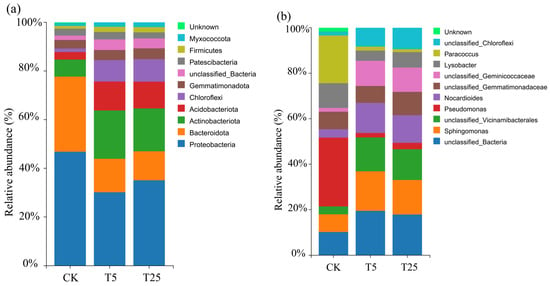

3.2.4. Species Composition Characteristics of Microbial Communities

Microbial community composition differed substantially among treatments at both taxonomic levels (Figure 7). At the phylum level (Figure 7a), Proteobacteria was the dominant phylum across all treatments but decreased from approximately 50% in CK to 30% in T5 and 35% in T25. Bacteroidota exhibited an opposite pattern, increasing from approximately 15% (CK) to 30% (T5) and 25% (T25), representing a 2-fold enrichment in T5. Actinobacteriota remained relatively stable at approximately 20% in CK and T5 but decreased to 10% in T25. Acidobacteriota showed progressive enrichment, increasing from approximately 8% (CK) to 12% (T5) and 15% (T25). At the genus level (Figure 7b), Pseudomonas dominated CK (~30%) but decreased approximately 50% in both drip treatments (~15%). Sphingomonas exhibited marked enrichment from ~5% (CK) to ~15% (T5) and ~30% (T25), representing 3-fold and 6-fold increases, respectively. The proportion of unclassified_Bacteria increased from approximately 10% (CK) to 20% in both T5 and T25.

Figure 7.

Relative abundance of rhizosphere microbial communities under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments at phylum (a) and genus (b) levels. Notes: CK, control (no irrigation); T5, shallow drip irrigation (5 cm burial depth); T25, deep drip irrigation (25 cm burial depth). Stacked bars show the relative abundance (%) of major bacterial taxa in each treatment. Only taxa with >1% relative abundance in at least one treatment are shown.

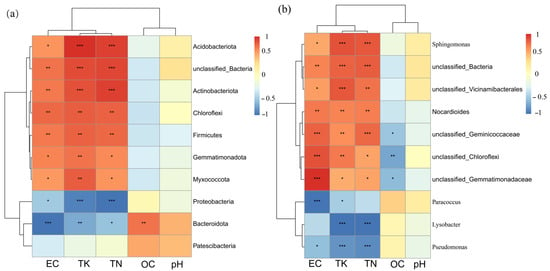

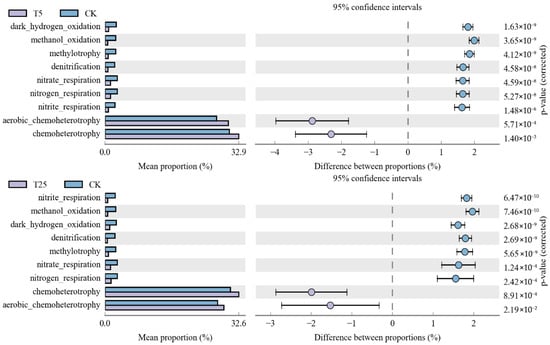

3.2.5. Correlations Between Microbial Communities and Soil Physicochemical Factors

Correlation analysis revealed distinct associations between bacterial taxa and soil factors (Figure 8). At the phylum level (Figure 8a), Acidobacteriota, unclassified_Bacteria, and Actinobacteriota exhibited strong positive correlations with TK and TN (p < 0.001), and positive correlations with EC (p < 0.05–0.01). Proteobacteria showed strong negative correlations with EC (p < 0.001), while Bacteroidota displayed strong negative correlations with EC (p < 0.001) and positive correlations with OC (p < 0.01). At the genus level (Figure 8b), Sphingomonas and unclassified_Bacteria showed strong positive correlations with TK and TN (p < 0.001) and positive correlations with EC. Pseudomonas exhibited strong negative correlations with EC and TN (p < 0.001), while Paracoccus displayed strong negative correlations with EC (p < 0.001) and moderate negative correlations with TN (p < 0.01). pH showed weak or non-significant correlations with most taxa at both levels.

Figure 8.

Correlation heatmap between major bacterial taxa and soil physicochemical factors at phylum (a) and genus (b) levels. Notes: EC, electrical conductivity; TN, total nitrogen; TK, total potassium; OC, organic carbon. Color intensity indicates correlation strength (Spearman’s correlation coefficient): red represents positive correlation; blue represents negative correlation. Asterisks denote significance levels: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

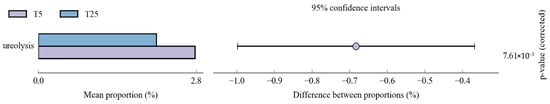

3.2.6. Functional Prediction Analysis of Microbial Communities

Functional prediction analysis revealed treatment-specific metabolic shifts (Figure 9). Functional prediction analysis using FAPROTAX revealed treatment-specific differences in predicted metabolic functions (Figure 9). Between T5 and CK, carbon metabolism functions (aerobic_chemoheterotrophy and chemoheterotrophy) were significantly higher in T5 (~33%) than CK (~30%) (p = 5.71 × 10−4 and 1.40 × 10−3). Anaerobic nitrogen transformation functions were significantly enriched in CK, including nitrite_respiration (p = 1.48 × 10−6), nitrogen_respiration (p = 5.27 × 10−8), nitrate_respiration (p = 4.58 × 10−8), and denitrification (p = 4.12 × 10−9). Between T25 and CK, anaerobic nitrogen transformation functions showed marked enrichment in T25, with nitrite_respiration, methanol_oxidation, and dark_hydrogen_oxidation exhibiting the strongest increases (p < 1 × 10−9). Other functions, including denitrification (p = 2.69 × 10−9) and nitrate/nitrogen respiration (p < 2.5 × 10−4), were also significantly higher in T25. Carbon metabolism functions showed relatively similar abundances between T25 and CK. Direct comparison between T5 and T25 revealed significant differentiation in ureolysis (T25 < T5, p = 7.61 × 10−3).

Figure 9.

Differential abundance of predicted microbial functional groups between treatments based on FAPROTAX analysis. Notes: CK, control (no irrigation); T5, shallow drip irrigation (5 cm burial depth); T25, deep drip irrigation (25 cm burial depth); (Left panels) show mean proportions (%) of functional groups; (Right panels) show differences between proportions with 95% confidence intervals. Functional predictions are based on 16S rRNA gene taxonomy using the FAPROTAX database. p-values (corrected) are shown on the right; only functions with significant differences (p < 0.05) are displayed.

3.3. Effects of Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths on Yield and Biomass of Dryland Saline-Alkaline Wheat

All yield and biomass indicators increased significantly with drip irrigation treatments, following a consistent ranking of T25 > T5 > CK (Table 3, all p < 0.05). The magnitude of improvement varied systematically by indicator type, with biomass indicators showing substantially larger relative increases than yield-related indicators.

Table 3.

Soil Physicochemical Properties of Rhizosphere of Dryland Saline-Alkaline Wheat Under Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depth Treatments.

Yield-related indicators exhibited moderate increases relative to CK. Grain yield increased by 40.0% in T5 and 55.0% in T25, while 1000-grain weight showed 19.9% and 39.7% increases, respectively. In contrast, biomass indicators demonstrated markedly greater responses, with glume biomass increasing by 121.7% (T5) and 195.4% (T25), and above-ground biomass rising by 131.9% (T5) and 163.4% (T25).

T25 consistently outperformed T5 across all metrics, with enhancement margins ranging from 10.7% for grain yield to 33.2% for glume biomass, indicating that deeper burial depth resulted in greater improvements in both yield and biomass accumulation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Physicochemical Regulation Mechanisms Under Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths

The core bottleneck restricting agricultural utilization of saline-alkali soils lies in high salt stress and nutrient deficiency. Drip irrigation burial depth achieves directional regulation of soil water-salt status and nutrient conditions by altering the migration paths and distribution characteristics of soil moisture [22]. This study demonstrated that deep drip irrigation (T25) substantially reduced soil salinity in the 0–40 cm layer compared to both conventional (CK) and shallow drip irrigation (T5) treatments. This effect is closely related to the characteristics of deep drip irrigation, which reduces surface evaporation and promotes deep leaching of soil salts [23]. The wetting front formed by deep burial exhibited higher stability, effectively avoiding salt surface accumulation that may occur under shallow systems [24].

Previous studies have similarly reported that drip tape placement depth critically influences salt distribution patterns, with deeper placement generally resulting in more effective desalinization in the root zone [25]. In terms of soil nutrient regulation, T25 treatment showed greater increases in soil organic matter content compared to both CK and T5 treatments. While total nitrogen and total potassium contents in T25 were lower than in T5 (a result of greater crop nutrient uptake associated with higher yield), the observed enrichment of anaerobic nitrogen transformation functions (e.g., nitrite respiration, denitrification) in T25 may indicate the development of more reducing (anoxic) microsites in deeper soil layers, potentially associated with localized oxygen depletion under stable moisture conditions [26,27]. These findings align with recent studies demonstrating that irrigation management influences not only nutrient pools but also microbial-mediated nutrient transformation processes [28].

Soil pH remained relatively stable across all treatments, which can be attributed to the strong buffering capacity of coastal saline-alkali clay soils. Previous studies have indicated that short-term irrigation management may not substantially alter pH in highly buffered soils, and longer observation periods may be necessary to detect such changes [20]. The clay soil layers in such systems can inhibit surface salt accumulation while effectively blocking vertical migration of soil moisture and solutes, thereby maintaining relative stability of soil physicochemical properties [29].

4.2. Microbial Community Responses and Functional Adaptability to Drip Irrigation Burial Depth

The structural and functional diversity of soil microbial communities is highly adapted to soil microenvironments shaped by drip irrigation management [30]. This study revealed that deep burial (T25) significantly altered microbial community composition. At the phylum level, T25 showed decreased relative abundance of Proteobacteria (from 50% in CK to 35%) and increased Acidobacteriota (from 8% to 15%), suggesting shifts toward taxa adapted to higher organic matter conditions. At the genus level, Sphingomonas exhibited marked enrichment in T25 (6-fold increase from CK), likely associated with enhanced organic carbon availability and root exudate utilization [31]. These compositional shifts are consistent with the increased soil organic matter content (44% increase) observed under deep burial treatment.

Alpha diversity analysis revealed contrasting patterns between shallow and deep burial treatments. The T5 treatment exhibited higher species richness indices (OTU, ACE, Chao1), while T25 showed higher community evenness (Shannon index) with no significant difference in Simpson index between treatments. These patterns reflect a fundamental trade-off between species richness and functional stability [32]. The shallow microenvironment under T5 is characterized by spatial heterogeneity, which may support greater species coexistence but potentially at the cost of temporal stability. In contrast, the deep microenvironment under T25 may favor more stable conditions that support fewer species but more balanced functional groups with greater resilience to environmental fluctuations. This interpretation aligns with ecological theory suggesting that environmental filtering and niche partitioning drive distinct assembly patterns in different soil microenvironments [33].

PCoA analysis demonstrated distinct clustering patterns among treatments, with clear separation along primary axes of variation and no overlap among treatments. This indicates that drip irrigation burial depth exerts significant directional control on community structure, with T25 showing the most divergent composition from CK. Correlation analyses identified EC, total potassium (TK), and total nitrogen (TN) as key environmental drivers of community differentiation, which is consistent with previous studies in saline irrigation districts showing that soil salinity and nutrient pools are primary factors structuring prokaryotic communities [34].

Functional prediction analysis revealed treatment-specific enrichment patterns, with T5 favoring aerobic carbon metabolism functions while T25 showed enrichment of anaerobic nitrogen transformation functions (e.g., nitrite respiration, denitrification, nitrogen respiration). These differential functional profiles may suggest that burial depth influences soil redox conditions, with deeper placement potentially creating more stable but locally oxygen-limited microsites. It should be noted that these predictions represent functional potentials inferred from taxonomic composition rather than direct measurements of microbial process rates.

4.3. Yield Improvement Mechanisms Mediated by Soil–Microbe Interactions

The observed yield improvements under drip irrigation treatments, particularly T25, appear to result primarily from physical and agronomic factors rather than microbial functional shifts. Deep burial enhanced desalinization (63% reduction in EC), increased soil organic matter accumulation (44% increase in OC), and improved water distribution to root zones, creating more favorable soil conditions for crop growth [35]. Concurrently, the directional enrichment of nitrogen-cycling functional groups (e.g., nitrite respiration, nitrogen respiration) suggests enhanced nutrient transformation capacity. Meanwhile, combined with greater root nutrient uptake efficiency—evidenced by the lower residual TN and TK concentrations in T25 relative to T5, which reflects more robust crop nutrient assimilation linked to its superior yield performance (Table 3) [36,37]—these factors were likely the primary drivers of the high yield observed in T25.

While shallow burial (T5) also improved yields relative to control, its effectiveness appears limited by several factors. First, the more modest desalinization effect may have maintained residual salt stress that constrained crop growth [35]; second, shallow water delivery may not have adequately supplied deeper root zones, limiting resource utilization efficiency [38]; third, shallow-buried drip tapes are more vulnerable to mechanical and environmental disturbances, requiring more frequent maintenance [39].

In contrast, deeply buried drip tapes (25 cm depth) can deliver water and fertilizer more precisely to dense root zones while avoiding mechanical damage and natural erosion, potentially extending system lifespan and reducing long-term maintenance costs. The lower residual TN and TK in T25, combined with superior yield, suggest more efficient nutrient uptake, though direct root measurements would further elucidate these mechanisms. These findings suggest that deep drip irrigation may be more suitable for sustainable, large-scale cultivation in saline-alkali soils, though economic analyses across multiple seasons would be needed to fully validate this conclusion. It is important to note that the relationships between microbial community characteristics and crop yield observed in this study are correlative rather than causative, and that the functional predictions are based on taxonomic inference rather than direct process measurements.

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. As a single-season field experiment conducted at one site, this study cannot evaluate long-term effects. Additionally, the CK treatment was rainfed while T5 and T25 received irrigation, meaning observed improvements reflect both water supply and burial depth effects. The focus on bacterial communities excludes potentially important fungal contributions to soil functioning. For wheat cultivation in saline-alkali soils with similar conditions, we recommend installing drip tapes at 25 cm depth. However, site-specific adjustments based on soil texture, initial salinity levels, and local precipitation patterns should be made, and multi-season validation is necessary before large-scale adoption.

Future research should prioritize multi-year, multi-site trials, expand microbiome characterization beyond bacteria, and perform comprehensive techno-economic analyses to guide practical implementation in saline-alkali agriculture. Although FAPROTAX analysis predicted that deep burial treatment enriched nitrogen cycling functions (e.g., nitrite respiration, denitrification, nitrogen respiration), we did not verify these predictions by directly measuring soil enzyme activities (such as urease, nitrate reductase, and nitrite reductase). Future studies should include the direct determination of key soil enzymes: urease, nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, and dehydrogenase. Validation of T25 in other years, cultivars, and soil contexts is also needed.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of drip irrigation burial depth on wheat productivity in saline-alkali soils through integrated analysis of soil properties, microbial communities, and crop performance.

Shallow-buried drip irrigation (5 cm, T5) significantly enhanced wheat productivity compared to CK, achieving 40% higher grain yield. T5 exhibited the highest microbial species richness (OTU, ACE, Chao1 indices), reflecting greater bacterial diversity in near-surface environments. Deep-buried drip irrigation (25 cm, T25) achieved superior agronomic performance, with grain yield 55% higher than rainfed control, primarily through enhanced desalination (63% reduction in electrical conductivity), increased soil organic matter (44%), and improved water distribution to root zones. T25 also showed altered microbial community structure, including enrichment of anaerobic nitrogen transformation functions (nitrite respiration, denitrification). However, these functional shifts may involve potential nitrogen losses through gaseous emissions (N2, N2O), which should be assessed in future studies to ensure sustainable nitrogen management (SDG 13). Correlation analyses revealed significant associations among soil properties (electrical conductivity, total nitrogen, total potassium), microbial community composition, and crop performance.

Overall, deep-buried drip irrigation at 25 cm provides advantages for wheat cultivation in saline-alkali soils through integrated improvements in soil physical-chemical conditions. Long-term, multi-site trials with direct functional measurements and comprehensive environmental assessments (including greenhouse gas emissions) are needed to validate these findings and guide practical implementation in saline-alkali farming systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, H.W.; software, W.C.; validation, T.W. and H.W.; formal analysis, H.W.; investigation, T.W. and H.W.; resources, K.G., X.L., and W.L.; data curation, T.W. and W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, H.W.; visualization, Z.Y.; supervision, K.G. and X.L.; project administration, T.W.; funding acquisition, T.W., H.W., K.G., and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Centrally Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project [246Z7001G], the National Key Research and Development Program Young Scientists Project [2023YFD1901900], and the Hebei Provincial Water Resources Science and Technology Plan Project [2020-07; 2022-20; 2024-63; HBST2024-03; 2025-63; 2025-72].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Feng, B.; Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, F.; Shen, C.; Ma, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Saline-Alkali Land Reclamation Boosts Topsoil Carbon Storage by Preferentially Accumulating Plant-Derived Carbon. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 2948–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Xu, W.H.; Gu, W.R.; Li, J.; Li, C.F.; Wang, M.Q.; Zhang, L.G.; Piao, L.; Zhu, Q.R.; Wei, S. Effects of Geniposide on the Regulation Mechanisms of Photosynthetic Physiology, Root Osmosis and Hormone Levels in Maize under Saline-Alkali Stress. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2021, 19, 1571–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, V. Micro-Irrigation Technologies for Water Conservation and Sustainable Crop Production; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xue, Z.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Wu, Z. Salt Leaching of Heavy Coastal Saline Silty Soil by Controlling the Soil Matric Potential. Soil Water Res. 2019, 14, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kang, Y. Water-Salt Control and Response of Chinese Rose Root on Coastal Saline Soil Using Drip Irrigation with Brackish Water. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiaoxia, A.; Sanmin, S.; Rong, X. The Effect of Dripper Discharge on the Water and Salt Movement in Wetted Solum under Indirect Subsurface Drip Irrigation. INMATEH-Agric. Eng. 2017, 51, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Sheng, G.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Effects of Subsurface Drip Fertigation on Potato Growth, Yield, and Soil Moisture Dynamics. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1485377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Duan, T.; Liang, F. The Difference in Cultivated Land Soil Quality: A Comparison between the North and South Sides of the Tianshan Mountains. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarula; Yang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Meng, F.; Ma, J. Impact of Drip Irrigation and Nitrogen Fertilization on Soil Microbial Diversity of Spring Maize. Plants 2022, 11, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, G.; García-Gutiérrez, S.; Vallejo, A.; Ibáñez, M.A.; Sanchez-Martin, L.; Montoya, M. Nitrous Oxide Emissions and N-Cycling Gene Abundances in a Drip-Fertigated (Surface versus Subsurface) Maize Crop with Different N Sources. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Ji, L.; Han, K.; Gong, J.; Dong, S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Du, B.; et al. Growth-Promoting Effects of Self-Selected Microbial Community on Wheat Seedlings in Saline-Alkali Soil Environments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1464195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Bao, Z.; Shi, X.; Bu, S.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D. Study on the Cumulative Effect of Drip Irrigation on the Stability of Loess Slopes. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 16, 2434612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yue, F.; Wang, L.; Song, J.; Lu, L. Breeding and Cultivation Techniques of Drought-Resistant and Salt-Tolerant Wheat Variety Jiemai 19. Agric. Sci. Technol. Newsl. 2017, 3, 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, F.; Wang, F.; Liu, B.; Fu, T.; Gao, H.; Liu, J. Supply and Demand Characteristics and Scenario Analysis of Ecosystem Services in Hebei Coastal Wetland. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2023, 31, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrahmen, A.; Abdelkader, D.; Younes, K.; Sawda, C.; Alsyouri, H.; El-Zahab, S.; Grasset, L. Investigating the Impact of Salinity on Soil Organic Matter Dynamics Using Molecular Biomarkers and Principal Component Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Gao, F.; Sun, J.; Cai, H.; Peng, S.; Li, H.; Xu, J. Irrigation Experiment Specification; Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Wang, K.; Bao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Guo, H.; Liu, X.; Li, N. Soil Conductivity Measuring Device Based on Wenner and Schlumberger Dual-Configuration Fusion. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 962-2018; Soil Testing—Part 2: Determination of Soil pH. National Standard of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- HJ 615-2011; Soil—Determination of Organic Carbon—Potassium Dichromate Oxidation Spectrophotometric Method. National Standard of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- De Falco, G.; Magni, P.; Teräsvuori, L.; Matteucci, G. Sediment Grain Size and Organic Carbon Distribution in the Cabras Lagoon (Sardinia, Western Mediterranean). Chem. Ecol. 2004, 20, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 9836-1988; Determination of Total Potassium in Soil. National Standard of China: Beijing, China, 1988.

- Heng, T.; Liao, R.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Effects of Combined Drip Irrigation and Sub-Surface Pipe Drainage on Water and Salt Transport of Saline-Alkali Soil in Xinjiang, China. J. Arid Land. 2018, 10, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, B.; Hopmans, J.; Simunek, J. Leaching with Subsurface Drip Irrigation under Saline, Shallow Groundwater Conditions. Vadose Zone J. 2008, 7, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Qi, Y.; Li, H.; Shen, Y. Research Progress on Water-Saving Potential and Mechanism of Subsurface Drip Irrigation Technology. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Tian, F.; Hu, H.; Yao, X.; Zhong, R. Soil Salt Distribution under Mulched Drip Irrigation in an Arid Area of Northwestern China. J. Arid Environ. 2014, 104, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaHue, D.; Wang, D.; Gaudin, A.; Durbin-Johnson, B.; Settles, M.; Scow, K. Extended Soil Surface Drying Triggered by Subsurface Drip Irrigation Decouples Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles and Alters Microbiome Composition. Front. Soil Sci. 2023, 3, 1267685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauer, J.; Werner, C.; Zaehle, S. Evaluating Stomatal Models and Their Atmospheric Drought Response in a Land Surface Scheme: A Multibiome Analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2015, 120, 1894–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, R.; Wang, M.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Liang, W.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. Response of Soil Nitrogen Components and nirK- and nirS-Type Denitrifying Bacterial Community Structures to Drip Irrigation Systems in the Semi-Arid Area of Northeast China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Feng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H. Dynamic Changes in Water and Salinity in Saline-Alkali Soils after Simulated Irrigation and Leaching. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hou, T.; Wang, J.; Che, Q.; Chen, B.; Wang, Q.; Feng, G. Soil Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure of Cotton Rhizosphere under Mulched Drip-Irrigation in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of Northwest China. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, B. The Ectomycorrhizal Fungi and Soil Bacterial Communities of the Five Typical Tree Species in the Junzifeng National Nature Reserve, Southeast China. Plants 2023, 12, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, E. Drip Irrigation Affects Soil Bacteria Primarily through Available Nitrogen and Soil Fungi Mainly via Available Nutrients. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1453054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Xiang, G.; Guo, X.; Min, W.; Guo, H. Regulation Effect of Biochar on Bacterial Community in Cotton Field Soil under Saline Water Drip Irrigation. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2024, 40, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gao, J.; Yu, X.; Borjigin, Q.; Qu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Guo, J.; Li, D. Evaluation of the Microbial Community in Various Saline Alkaline-Soils Driven by Soil Factors of the Hetao Plain, Inner Mongolia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, D.; Chi, Z.; Fan, X.; Cao, L.; Li, W. Effect of Subsurface Drip Irrigation on Soil Desalination and Soil Fungal Communities in Saline–Alkaline Sunflower Fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lv, K.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, G. Drip Irrigation Combined with Organic Fertilizers Improves Crop N Uptake and Yield by Reducing Soil Salinity and N Loss in Saline–Alkali Sunflower Farmlands. Soil Tillage Res. 2026, 255, 106789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaad, M.; Deshesh, T. Wheat Growth and Nitrogen Use Efficiency under Drip Irrigation on Semi-Arid Region. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2019, 8, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Modeling Root Water Uptake of Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Under Deficit Subsurface Drip Irrigation in West Texas. Master’s Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Cai, H.; Sun, S.; Gu, X.; Mu, Q.; Duan, W.; Zhao, Z. Effects of Drip Irrigation Methods on Yield and Water Productivity of Maize in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.