Abstract

Fusarium wilt (FW), caused by Fusarium oxysporum, poses a significant threat to mungbean (Vigna radiata L.), impacting its yield and quality. In this study, a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population was developed by crossing the highly resistant cultivar Weilv 9002-341 with the highly susceptible line V1128. Assessment of resistance revealed a continuous variation in the average disease index within the resulting population, consistent with the inheritance pattern of quantitative traits. Leveraging an F2:3 segregating population, we conducted linkage mapping analysis and bulked segregant analysis by sequencing, leading to the construction of a genetic linkage map and the identification of a region correlated with resistance. Within this region, 14 novel simple sequence repeat markers were designed to enable refined mapping. A putative resistance locus, spanning 0.17 Mb and encompassing 19 annotated genes, was precisely located. Ultimately, two genes were identified as high-priority candidates conferring resistance. The results of this study lay the foundation for the functional investigation of genes associated with resistance to Fusarium wilt disease in mungbean.

1. Introduction

Mungbean (Vigna radiata L.; Fabaceae, Papilionoideae, Phaseoleae) and is an important legume crop in East, South, and Southeast Asia [1]. China is the second largest producer of mungbean globally, second only to India. Mungbean is a fair source of protein, vitamin C, and minerals, and is a valuable addition to crop rotation systems [2]. Fusarium wilt (FW) is caused by a widely distributed soil-borne pathogen, Fusarium oxysporum. Members of the genus Fusarium are pathogenic fungi that are distributed worldwide. F. oxysporum can infect a variety of crops including legumes [3,4,5], vegetables [6,7,8,9] and economic crops such as cotton [10] and banana [11]. Depending on its host specificity, this pathogen can be classified into more than 150 formae speciales [12]. The pathogen causing FW in mungbean is named F. oxysporum f. sp. mungcola (Fom) [13].

Infection of the root is the first step of Fom invasion in mungbean. Chlamydospores within the soil germinate and infiltrate the host plant’s roots, and then the mycelia grow and expand along the vascular system. This progression culminates in the withering of both roots and leaves, vascular discoloration, and stunted plant growth, ultimately leading to death. Recent reports indicate that the prevalence and intensity of Fom have escalated recently in India, China, and Australia [1,14,15]. The agricultural consequences of this disease can be dire, with yield losses surpassing 80% in severe cases [16]. The prevention and control of Fom has become an important issue in mungbean production.

Various management methods are used to control FW, including crop residue management [17,18,19], chemical control [20,21], solarization [22,23], crop rotation [24], the cultivation of resistant or less susceptible varieties, and biological controls [25,26]. Because Fom can survive in the soil for a long time, the most effective control method is to cultivate resistant varieties. Research on FW in mungbean started relatively late. Initially, some resistant varieties were identified in field studies, but systematic research on resistance did not begin until later. After identification of the pathogen [4,16], a method to evaluate resistance was established [15], and many FW-resistant mungbean germplasm materials were identified using this method [27]. The results of those studies suggest that it is possible to discover FW resistance genes.

In legume crops, considerable progress has been made in the study of wilt resistance genes. In pea (Pisum sativum), four common wilt races (races 1, 2, 5, and 6) have been identified. Early studies suggested that resistance to each race is controlled by distinct single dominant genes [28]. The resistance gene Fw against race 1 was mapped to linkage group 3 (LG3) [29,30], while Fwf conferring resistance to races 5 and 6 was located on LG2 [31,32]. The resistance gene Fnw for race 2 was mapped to LG4, although two minor-effect QTLs were also identified on LG3 [33]. Deng et al. [34] mapped a Fusarium wilt resistance gene FwS1 and proposed that it might be tightly linked or identical to Fw. In contrast, the inheritance of Fusarium wilt resistance in chickpea (Cicer arietinum) is more complex, with multiple genetic patterns reported for resistance to Fusarium oxysporum. Resistance to race 0 [35,36] can be governed by either a single gene or two genes, and the resistance gene Foc-01 was mapped to LG3 [37]. Resistance to race 1A is controlled by two recessive genes [38]. For races 3, 4, and 5, resistance follows a single-gene inheritance pattern (Foc-3, Foc-4, and Foc-5, respectively) [35,39,40]. While Gumber et al. [41] suggested that resistance to race 2 is conferred by two genes, later studies supported a single recessive gene model [42]. Sharma and Muehlbauer [43] further reported that five resistance genes (Foc-1, Foc-2, Foc-3, Foc-4, and Foc-5), corresponding to resistance against races 1A, 2, 3, 4, and 5, form a tight gene cluster spanning 8.2 cM on linkage group 2 (LG2). In common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), resistance to race 4 is controlled by a single gene [44]. In lentil (Lens culinaris), the Fusarium wilt resistance gene Fw has been mapped to linkage group 6 [45]. However, to date, no definitive wilt resistance genes have been cloned in any of these legume species.

Plant disease resistance genes (R genes) encode immune receptors that recognize pathogen-specific effectors encoded by avirulence genes (Avrs), thereby activating effector-triggered immunity (ETI) and eliciting robust defense responses [46,47]. These responses encompass hypersensitive cell death, a reactive oxygen species burst, calcium influx, MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascade activation, phytohormone signaling, and transcriptional reprogramming [48,49,50]. On the basis of their conserved domains, R gene products can be classified as nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins, toxin reductases, protein kinases, leucine-rich repeat plus transmembrane receptors (LRR-TM), and LRR-TM-protein kinases (LRR-TM-PK). The majority of these R gene products harbor either NBS-LRR motifs or membrane-anchored LRR receptor architecture.

The NBS-LRR structure comprises two core domains: the NB-ARC domain and the LRR domain. The NB-ARC domain facilitates immune signal activation and transduction through ATP/ADP binding-mediated conformational changes, whereas the LRR domain specifically recognizes pathogen-derived Avr effectors to modulate downstream signaling. Notably, most identified FW resistance genes (e.g., tomato I2, I7, and melon Fom2) encode LRR-containing proteins [51,52,53]. Intriguingly, the tomato I3 gene [54], a member of the SRLK family, may recognize Avr effectors via subdomains between its G-lectin and PAN_AP domains. The cotton Fov7 gene, encoding a glutamate-like receptor atypical of classical R gene products, triggers specific immune responses by inducing a calcium influx [55].

Transcriptomic analyses of mungbean and common bean have revealed significant enrichment of FW resistance-related pathways post-F. oxysporum infection, including plant hormone signal transduction, MAPK signaling, peroxisome metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and flavonoid biosynthesis [5,56]. A peroxidase gene in common bean was demonstrated to enhance FW resistance [57]. Although MAPK signaling cascades generally promote disease resistance, GhMPK20 negatively regulates FW resistance in cotton by disrupting salicylic acid signaling via the MKK4-MPK20-WRKY40 cascade [58]. Additionally, in cucumber (Cucumis sativus), a gene encoding a chitinase confers enhanced resistance to F. oxysporum [59]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, multiple hormone-responsive transcription factors coordinate FW resistance [60,61,62,63].

To locate genes related to FW resistance in the mungbean genome, we constructed an F2:3 population and a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population for genetic mapping. A resistance locus 0.17 Mb in length was located, and candidate genes related to resistance were detected by bulked segregant analysis by sequencing (BSA-Seq). The results of this study lay the foundation for the functional investigation of genes associated with FW resistance in mungbean.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant and Pathogen Materials

Weilv 9002-341, a highly resistant landrace of mungbean originating from China, and V1128, a highly susceptible landrace of mungbean originating from India, were utilized as parental lines to establish a population of recombinant inbred lines (RILs). The F2:3 population, comprising 259 lines, was employed for both linkage mapping and BSA-seq. To achieve a more refined linkage map within the resistance-related region, an RIL-F8 population consisting of 239 plants was employed. All seeds of mungbean were sourced from the Chinese Mungbean Germplasm Bank.

The F08 strain (race 0) of F. oxysporum f. sp. mungcola (Fom) was generously provided by the Institute of Crop Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China.

2.2. Pathogen Inoculation and Resistance Evaluation of Mungbean Plants

The F08 strain of Fom was cryopreserved and maintained at −80 °C. Prior to inoculation, the strain was cultivated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) culture medium at 25 °C. Mungbean seedlings were grown in a greenhouse under controlled conditions (25 °C, 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod). For inoculation, the root cutting technique was employed upon full expansion of the primary leaves in the seedlings. Each inoculation consisted of three replicates, with each replicate comprising 10 seedlings.

The assessment commenced 14 days post-inoculation. The disease index (DI) was computed using the resistance evaluation methodology outlined by Sun et al. [15]. The classification of disease resistance levels was based on DI values: high resistance (HR), where 0 < DI ≤ 15; resistance (R), where 15 < DI ≤ 35; moderate resistance (MR), where 35 < DI ≤ 55; susceptibility (S), where 55 < DI ≤ 75; and high susceptibility (HS), where DI > 75. The average DI was calculated for each line and used for linkage map construction and QTL analysis, together with the genotype data.

2.3. Linkage Mapping and QTL Analysis

Young leaves of mungbean seedlings were collected for DNA extraction. Each sample consisted of about 100 mg of leaf tissue. Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaf samples using the cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method [64]. Then, PCR amplification was performed using 100 ng genomic DNA, 0.5 μL each of forward and reverse primers, 5 μL 2 × Utaq PCR Mix (Beijing Zoman Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and 2 μL nuclease-free water. The PCR thermal program was as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and then final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR amplification products were resolved by 8% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

We designed 3767 SSR markers using SSR locator 1.0 software [65], based on the mungbean genome sequence [66] and mungbean transcriptomic data “https://asia.ensembl.org (accessed on 2015–2016)”. These SSR markers were used to determine the degree of polymorphism between parents. In total, 208 polymorphic markers were selected and used for linkage mapping analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Linkage mapping analysis was conducted using the ICIM-ADD (inclusive composite interval mapping—additive mapping) method with QTL IciMapping 4.0 software (Institute of Crop Science and CIMMYT China, Chinese Academy of Agriculture Sciences, Beijing, China). The threshold LOD score was 8.2 and the maximum mapping distance was 50 cM.

2.4. Bulk Segregant Analysis and Fine Mapping

The F2:3 segregating population derived from the cross between Weilv 9002-341 and V1128 was used for BSA-seq. We selected 30 HR lines and 30 HS lines to construct the resistant bulk (RF) and susceptible bulk (SF), respectively. The parents Weilv 9002-341 and V1128 were used to generate the resistant parent (RP) and susceptible parent (SP). Each parent consisted of 10 plants. The two parents were highly inbred and homozygous.

Library construction and sequencing were carried out by Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Genomic DNA was randomly sheared into fragments with a length of 350 bp, then modified, purified, and amplified by PCR to generate DNA libraries. The libraries that passed quality control were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The sequencing reads (raw data) were filtered to ensure the reliability of downstream analyses. In this filtering step, the low-quality reads (those with more than 50% of bases with Q score of ≤10) and reads containing more than 10% unknown bases (N) were removed. Clean reads were mapped to the reference genome (Vrad_JL7) [66] using BWA 0.7.17 software [67]. Based on the position of clean reads on the reference genome, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions/deletions (InDels) were identified by GATK [68]. The SNPs and InDels were filtered to remove: (a) SNP clusters (two SNPs within 5 bp); (b) SNPs within 5 bp of an InDel; (c) 2 InDels located fewer than 10 bp apart; (d) variants with a Q score lower than 30; (e) variants with a QD (quality/depth) score lower than 2.0; (f) variants with an MQ score of <40; and (g) variants with an FS score of >60.

Prior to linkage analysis, quality SNPs were extracted by removing those with multiple alleles, those with a depth of less than 4, those with the same genotype among all mixed pools, and those on recessive alleles that were not inherited from recessive parents. Quality InDels were obtained using the same process. SNP-index and InDel-index algorithms were used to identify SNPs and InDels. The linked regions of SNPs and InDels were defined and the intersection was taken as the final candidate linked region.

Next, we conducted fine mapping of the resistant candidate region identified in the initial genetic mapping process. In this region, 188 SSR markers were designed and 14 that were polymorphic between the two parents were selected. The RIL-F8 population was used as the plant material. Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method, and genotypes were identified by PCR and 8% w/v polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The resistance of plants in the mapping population was evaluated three times between June 2022 and May 2023. Mapping was conducted using QTL IciMapping 4.0. The threshold LOD scores at the three resistance evaluation times were 10.90, 2.96, and 5.64.

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis

Weilv 9002-341 and V1128 were used for transcriptome sequencing. Root tissues of mungbean seedlings were collected at 0, 8, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post-inoculation with Fom. Three replicates, each consisting of seven seedlings, were analysed. Samples were processed by Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The total RNA was extracted using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The mRNA was isolated and randomly fragmented, then cDNA was synthesised with fragmented mRNA as the template. The cDNA library was sequenced on the Illumina high-throughput platform to generate raw data. Reads with low-quality scores were removed. The filtered clean reads were mapped to the Vrad_JL7 genome using HISAT2 2.2.1 software [69]. The mapped reads were assembled using StringTie v2.2.1 [70]. The Non-Redundant (NR), Swiss-Prot, Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG), Eukaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG), and Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases were used for gene annotation. Gene transcript levels were estimated based on the FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped) values using StringTie with the maximum flow algorithm. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by DESeq2, and were those that met the criteria of fold change (FC) ≥ 2 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Resistance Phenotypes

We investigated the resistance phenotypes of the 259 F2:3 lines. After inoculation with Fom, these plants exhibited varying degrees of yellowing, wilting, and stunted growth, and some of them died. On the basis of DI, the plants in this population were divided into five disease resistance classes as shown in Figure 1a–e: HR (21 plants), R (67 plants), MR (47 plants), S (58 plants), and HS (66 plants). The frequency distribution of the disease index (DI) in the F2:3 population is shown in Figure 1f. The trait exhibits a continuous and unimodal distribution that is remarkably symmetrical (skewness = 0.028) but notably flat, i.e., platykurtic (kurtosis = −1.19). This ‘flat-topped’ shape deviates from the classic bell-shaped normal distribution expected under an infinitesimal model of polygenic inheritance. The distribution fully spans the phenotypic range between the two parents (0–100), with a mean (52.5) close to the median (51.85), and exhibits pronounced transgressive segregation. This pattern is consistent with a quantitative trait controlled by a limited number of loci with larger effects, rather than innumerable infinitesimal factors. Analyses of 55 F1 plants indicated that resistance was controlled by a dominant gene.

Figure 1.

Phenotypes (a–e) and disease index frequency distribution (f) of 259 F2:3 plants. Resistant control, the resistant cultivar Weilv 9002-341 used as a control; Susceptible control, the susceptible cultivar V1128 used as a control; HR, highly resistant; R, resistant; MR, moderately resistant; S, susceptible; HS, highly susceptible. Disease indexes of the parents Weilv 9002-341 (♂) and V1128 (♀) were 4.5 and 95.0, respectively. The distribution is continuous, symmetric, and unimodal but notably flat, indicative of a quantitative trait.

3.2. Linkage Mapping and Gene Location of FW Resistance Loci

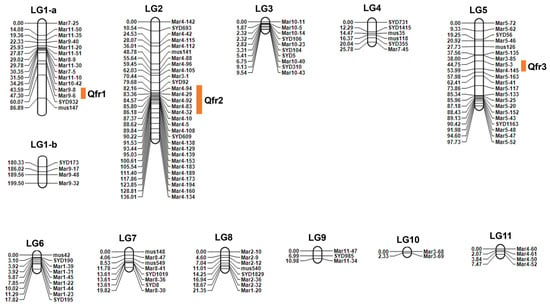

In total, 208 polymorphic SSR markers distributed on 11 chromosomes of mungbean were used for QTL mapping. We constructed a linkage map containing 119 SSR markers, which covered 11 linkage groups. Within LG1, markers were clustered separately at the top and bottom regions. Due to the large distance between them and the absence of intervening markers, we divided this group into two independent linkage groups, LG1-a and LG1-b. The map had a total length of 548.33 cM. The distance between adjacent markers ranged from 0.38 to 93.44 cM, with an average of 1.68 cM (Figure 2). The number of SSR markers in the 11 linkage groups ranged from two (linkage group 10) to 30 (linkage group 2). Three loci related to resistance were detected and were named Qfr1, Qfr2, and Qfr3; these markers were located in linkage groups 1, 2, and 5, corresponding to chromosomes 9, 4, and 5, respectively (Table 1). These loci explained 82.36% of the phenotypic variation in FW resistance. The additive effects of the three loci were negative, suggesting that the alleles from the female parent conferred susceptibility, leading to an increase in the DI value.

Figure 2.

Genetic linkage map based on simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers and identified QTLs for fusarium wilt resistance in the F2:3 population. The map comprises 11 linkage groups (LGs). Bars ■ indicate positions of QTLs related to fusarium wilt resistance. Due to its extensive genetic length, linkage group 1 (LG1) is presented in two separate sections (LG1-a and LG1-b) for clarity.

Table 1.

QTLs related to FW resistance in F2:3 segregating population of mungbean. Among them, Qfr2 on chromosome 4 exhibited both the highest LOD score (7.45) and PVE (61.01%), identifying it as the major-effect locus in the initial mapping.

3.3. Bulked Segregant Analysis by Sequencing

According to the resistance phenotype, two bulk populations (RF, SF,) and two parents (RP, SP) were constructed using the plants with extreme phenotypes. Sequencing yielded 83.36 Gbp clean data (Table 2), consisting of 30.77 Gbp for the RF, 31.30 Gbp for the SF, 10.58 Gbp for the RP line, and 10.71 Gbp for the SP line. The GC percentage ranged from 33.83% to 34.07%, and the average Q30 was 92.96%. Clean reads were mapped onto the reference genome. The percentage of mapped reads ranged from 99.14% to 99.47%. The average sequencing depth of the four bulks was 43.25×, and the genome coverage ranged from 94.58% to 99.06%. Based on the mapped clean reads, SNPs and InDels were identified. We obtained 2,161,980 SNPs and 429,730 InDels in total.

Table 2.

Quality statistics of sequencing data for the resistant/susceptible bulked pools and parents (BSA).

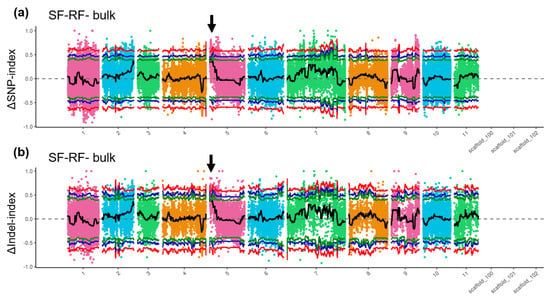

The detected SNPs and InDels were used to conduct linkage analysis. In the SNPs-index analysis, when the linkage threshold was set at a confidence interval of 0.90, a linkage region at position 0.17–2.4 Mb on chromosome 5 was identified. The InDel-index analysis was similar to the SNP-index analysis (Figure 3). In the InDel-index analysis, four linkage regions were identified at a confidence interval of 0.90, at positions 0.36–0.37 Mb, 0.39–2.23 Mb, 2.26–2.28 Mb, and 2.30–2.32 Mb on chromosome 5. Because the four loci were adjacent, we merged them into one locus at position 0.36–2.32 Mb on chromosome 5 (Figure 3b). The intersection of linked regions identified using SNPs and InDels was considered as the final linkage region related to resistance, which was located at position 0.36–2.32 Mb on chromosome 5.

Figure 3.

Identification of associated genomic regions using BSA-seq. Distribution of single-nucleotide repeats (SNPs) (a) and insertions/deletions (InDels) (b) on 11 chromosomes of mungbean. Coloured dots represent ΔSNP index and ΔInDel index values for each site. Black line indicates fitted value. Red line indicates linkage threshold at 99% confidence interval, blue line for 95%, and green line for 90%. Black arrow indicates linked region above threshold of 90%. Both SNP and InDel analyses converged on a major associated region (Chr5: 0.36–2.32 Mb). This region physically overlaps with the QTL Qfr3 (Chr5: 0.82–9.30 Mb) identified in the initial linkage analysis.

3.4. Refined Mapping at Overlapping Region

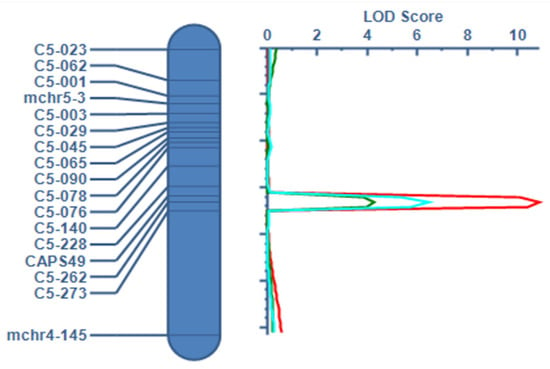

To ensure the accuracy of the results, F8 plants from the RIL population were used for fine mapping at the three loci: Qfr1, Qfr2, and Qfr3. The SSR markers of the three loci were analysed and only the resistance-related region at Qfr3 (chromosome 5:0.82–9.30 Mb) was detected. Therefore, the intersection of the BSA-locus and Qfr3 was selected as the candidate region for resistance. This region was located at position 0.82–2.32 Mb on chromosome 5.

We designed 188 SSR markers for the candidate region, and then selected 14 polymorphic markers (Supplementary Table S2) for finer linkage mapping. The resistance phenotype of F8 plants was investigated three times between June 2022 and May 2023. The resistance phenotypes of the 239 F8 plants were as follows: 11 HR, 41 R, 92 MR, 56 S, and 39 HS. Finally, we detected a resistance-related locus between the SSR markers C5-228 and C5-273 (Figure 4). This locus was detected at all three sampling times, and explained 7.31–25.26% of the phenotypic variation in FW resistance. On the basis of these findings, we searched for genes related to disease resistance at position 2.15–2.32 Mb on chromosome 5, a region containing 19 annotated genes.

Figure 4.

Fine mapping of the candidate region (identified by BSA and encompassing Qfr3) using the advanced F8 population. Red, blue, and green lines represent three resistance evaluations. All replicates consistently delimited the major resistance locus to the same interval between two flanking markers, confirming the stability and reproducibility of the locus.

3.5. Identification of DEGs from Transcriptome Data

The transcriptomes of the parents Weilv 9002-341 (resistant, R) and V1128 (susceptible, S) were sequenced, and 222.25 Gb clean data were obtained. At least 5.76 Gb clean reads were generated for each sample with a minimum of 91.85% of clean reads (quality score of Q30). Clean reads from each sample were mapped onto the specified reference genome, with 80.72% to 95.45% of reads mapped to the genome. The DEGs with FC ≥ 2 and FDR < 0.01 in pairwise comparisons between samples were identified.

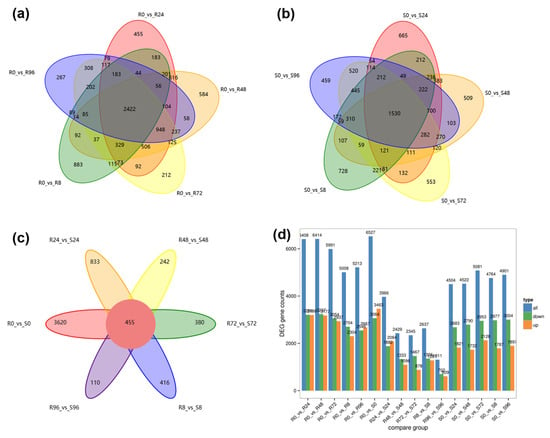

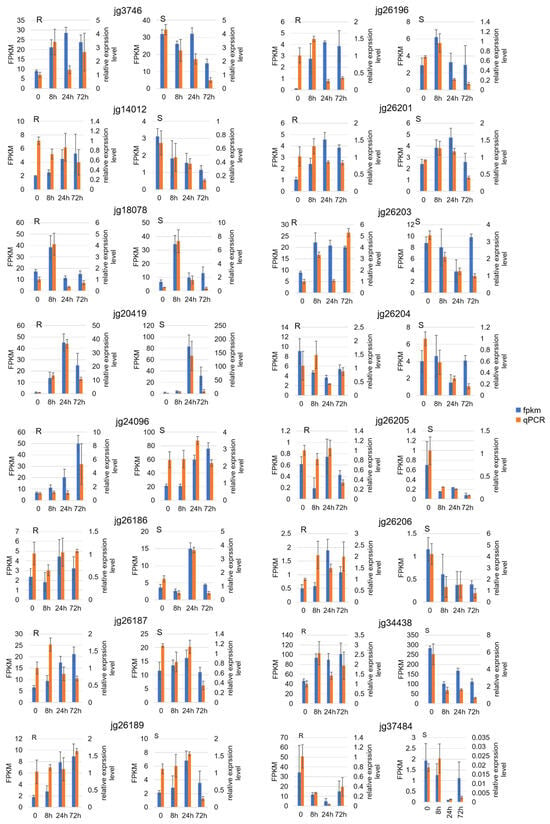

A total of 14,610 DEGs were detected in comparisons between 0 h post-inoculation (hpi) and the five time points after inoculation (8, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hpi); there were 9716 DEGs in Weilv 9002-341 and 9139 DEGs in V1128 (Figure 5a,b). There were 9932 DEGs between the two parents (Figure 5c), 8335 of which were differentially expressed after inoculation with Fom. We speculated that these DEGs might be related to the plant–pathogen interaction. The DEGs among all compared groups are shown in Figure 5d and Supplementary Table S4. The proportion of down-regulated DEGs was higher in V1128 than in Weilv 9002-341 after inoculation with Fom. We selected 16 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for qRT-PCR validation (Figure 6). The majority exhibited consistent expression patterns between transcriptomic data and qRT-PCR results, confirming the reliability of the RNA-Seq analysis. Observed discrepancies in a subset of genes may be attributed to methodological variations between techniques or stochastic experimental errors.

Figure 5.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified from RNA-seq data. Venn diagrams illustrate the numbers and overlaps of DEGs in the resistant parent Weilv 9002-341 (a) and the susceptible parent V1128 (b), respectively, at various time points (0, 8, 24, 48, 72, 96 h post-inoculation) compared to the 0 h control within each parent. (c) Venn diagram showing DEGs from comparisons between the two parents (R vs. S) at each time point. (d) Bar plot summarizing the number of DEGs in all compared groups (within-parent time-series and between-parent comparisons).

Figure 6.

Validation of transcript profiles for differentially expressed genes within the candidate resistance locus. The expression levels of candidate genes in resistant and susceptible parents (R, Weilv 9002-341; S, V1128) at post-inoculation time points (0, 8, 24, 72 h post-inoculation, hpi) were validated using qPCR. Blue bars represent FPKM values from RNA-seq data, and orange bars represent relative expression levels from qPCR.

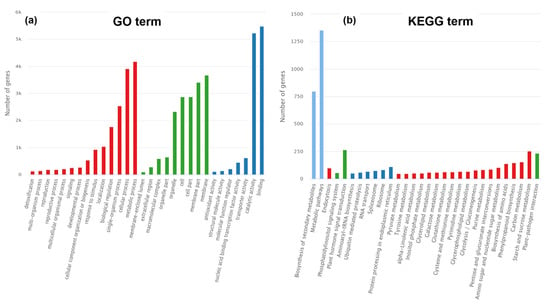

The DEGs between the two parents were subjected to GO and KEGG annotation analyses. In the Biological Process category, the terms “metabolic process”, “cellular process”, “single-organism process”, “biological regulation”, “localisation”, and “response to stimulus” were significantly enriched. In the Cellular Component category, the terms “membrane”, “membrane part”, “cell part”, “cell”, and “organelle part” were significantly enriched. In the Molecular Function category, the terms “binding”, “catalytic activity”, “transporter activity”, “nucleic acid binding transcription regulator activity”, “molecular function regulator”, “structural molecule activity”, and “antioxidant activity” were significantly enriched (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Gene Ontology (GO) (a) and Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (b) classifications of DEGs. (a) Results of GO functional enrichment analysis, showing the significantly enriched terms within three major categories: Biological Process, Cellular Component, and Molecular Function. The bar length represents the enrichment magnitude. (b) Results of KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, displaying the significantly enriched metabolic or signal transduction pathways. This analysis reveals the potential biological processes in which these DEGs are collectively involved.

The KEGG analysis classified the DEGs into groups on the basis of their involvement in particular pathways. In the Metabolism group, the pathways showing significant enrichment were “starch and sucrose metabolism”, “carbon metabolism”, and “phenylpropanoid metabolism”. In the Cellular Process group, the pathway “endocytosis” was significantly enriched. In the Environmental Information Processing group, the pathways “plant hormone signal transduction” and “phosphatidylinositol signalling system” were significantly enriched. In the Organismal Systems group, the significantly enriched pathway was “plant–pathogen interaction”. In the Genetic Information Processing group, the enriched pathways were “protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum”, “ribosome”, “spliceosome”, “RNA transport”, “ubiquitin mediated proteolysis”, and “aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis” (Figure 7b).

3.6. Selection of Candidate Resistant Genes

Nineteen annotated genes were located in the candidate resistant region (Supplementary Table S3). We screened these genes based on the following criteria: (1) encoding canonical disease-resistant protein domains or exhibiting sequence homology to known resistance genes; (2) harboring parent-specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms in coding or regulatory regions; (3) showing significant differential expression in transcriptome data following pathogen inoculation. Five genes exhibiting structural homology characterised disease resistance genes (jg26202, jg26203, jg26204, jg26205, jg26206). Protein structural analysis of the five candidate genes was performed using the SMART database “http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ (accessed on July 2025)”. This analysis revealed that jg26202, jg26203, jg26204, and jg26206 encoded TIR-NB-LRR resistance proteins. Sequence alignment analysis demonstrated significant homology between these four genes and the tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene N [71]. In contrast, jg26205 encoded a protein that lacked the LRR domain but harboured a 145 amino acid sequence homologous to the resistance protein RPS6 [72]. In addition, jg26207 encoding a putative defensin-like protein were also considered to be related to FW resistance.

Based on BSA resequencing data from the four bulks, eight putative disease resistance-associated SNPs were identified within the resistance-related locus. Of these, four SNPs were located in genes encoding proteins of unknown function, while the remaining four SNPs were associated with jg26190, jg26201, jg26205 and jg26206. In RNA-Seq analysis, both jg26205 and jg26206 were upregulated and maintained relatively high expression levels in resistant materials, whereas they were downregulated in susceptible materials. These two genes provide clear targets for subsequent research.

4. Discussion

In the initial mapping using an F2:3 population, we detected three quantitative trait loci (QTLs), designated Qfr1, Qfr2, and Qfr3. However, results from BSA and subsequent QTL mapping in an F8 population confirmed the existence of only one major disease resistance locus (Qfr3), which was not the one with the largest effect size in the initial mapping (Qfr2). To address this discrepancy, we used the validated major locus Qfr3 as a covariate to adjust the phenotypic data from the initial population. The distribution of residuals after this adjustment displayed multiple peaks (Supplementary Figure S1), indicating the presence of additional factors influencing the phenotype beyond Qfr3. This observation is consistent with the detection of multiple loci in our initial scan.

We further analyzed Qfr2, the locus with the highest effect value in the initial mapping. Its genotype showed no clear association with the distribution of residuals adjusted for Qfr3 (Supplementary Figure S2). Moreover, for the Qfr2 locus, plants carrying the putative resistance allele exhibited a higher mean disease index than those carrying the susceptibility allele—a direction of effect opposite to the expectation for a resistance trait. Considering the relatively high rate of missing genotypic data for Qfr2 and the use of an older, less standardized disease assessment method at the time (employing symptom classification criteria different from current standards), we conclude that Qfr2 is likely to represent a false-positive signal.

Analysis of the third locus, Qfr1, revealed a severe allelic frequency bias within the population, with the vast majority of individuals (77.22%) fixed for the paternal genotype. This bias complicates an accurate assessment of its genetic effect (Supplementary Figure S3). Furthermore, when Qfr1 was used as a covariate to adjust the phenotype, the resulting residual distribution closely resembled the original phenotypic distribution (Supplementary Figure S4). This indicates that the independent contribution of Qfr1 to the overall phenotypic variation is minimal, and its weak signal detected in the initial analysis may be the result of statistical fluctuation.

The transcriptome analysis revealed significant enrichment of “plant hormone signal transduction”, “phenylpropanoid metabolism”, and “plant–pathogen interaction” pathways, all of which are related to resistance [56,73,74]. These pathways were enriched with DEGs between the two parents, indicating that they are involved in resistance to FW in mungbean. The “phenylpropanoid metabolism” pathway produces many metabolites such as flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic acid esters, hydroxycinnamic acid amides, and the precursors of lignin, lignans, and tannins [75], which function as antioxidants, antifungal compounds, and components of cells walls. The DEGs in the “plant hormone signal transduction” pathway may be involved in auxin, cytokinin, abscisic acid, jasmonate, and/or brassinosteroid signalling. However, because there is a relatively distant genetic relationship between Weilv 9002-341 and V1128, the DEGs between the two parents are also likely to be involved in other pathways unrelated to disease resistance.

So far, only one study [56] has investigated the transcriptome of mungbean after inoculation with Fom. In that study, 27 genes were identified as candidate resistance genes, including seven R genes. However, there were no R genes located on chromosome 5. The reasons for the differences between their results and ours might be the different mungbean varieties used; i.e., the variety in their study may have harboured different resistance genes. In addition, some pathways function only at an early stage of infection. The pathways enriched with DEGs detected at 8 hpi between the resistant and susceptible materials were “2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism”, “pyruvate metabolism”, “tyrosine metabolism”, “ABC transporter”, and “carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms”, suggesting that these pathways participate in the early stage of the pathogen response. The pathways enriched with DEGs that were up-regulated in Weilv 9002-341 at 24 hpi were “photosynthesis” and “photosynthesis-antenna proteins”, suggesting that its resistance involves a light protection process.

RPS6 (ribosomal protein S6), a member of the S6E family of ribosomal proteins, is primarily involved in translational regulation and has been demonstrated to participate in disease resistance pathways across diverse plant species. In barley, RPS6 confers resistance against wheat stripe rust [76]. In soybean, RPS6 and RPS4 collectively recognize the C-terminal and N-terminal domains, respectively, of the effector Avr4/6 from Phytophthora sojae [77]. Arabidopsis RPS6 recognizes the HopA1 effector secreted by Pseudomonas syringae [72] and engages in the MEKK1–MKK1/MKK2–MPK4 cascade-mediated immune signalling [78]. The candidate gene jg26205, which is homologous to Arabidopsis RPS6, may operate through a conserved mechanistic framework. However, structural profiling of the jg26205 protein revealed the absence of a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, suggesting its potential involvement in disease resistance through atypical mechanisms, possibly via protein–protein interactions with additional immune components.

Resistance to F. oxysporum might be a combination of multiple factors. This is supported by the fact that the resistance trait of the segregating population exhibited a continuous distribution. Further research is needed to explore the mechanism of resistance. However, functional validation of these genes is currently impeded by the host specificity of the pathogen and the lack of a robust genetic transformation system.

5. Conclusions

To summarise, through linkage mapping, BSA-seq, and transcriptome analyses, we identified five candidate genes for FW resistance. All of these genes encode products with an NB-ARC domain, a characteristic of proteins involved in pathogen resistance. This is the first time that genes related to FW resistance have been identified in mungbean. Further characterisation of these genes will be useful to clarify the mechanism of FW resistance in mungbean.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020242/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. (Zhendong Zhu) and J.T.; Methodology, Y.S., C.L., Z.C., Z.Z. (Zhendong Zhu) and B.F.; Software, C.L. and Y.W.; Validation, Y.S., Z.Z. (Zhixiao Zhang) and S.W.; Formal analysis, Y.S., Z.Z. (Zhixiao Zhang), Y.W., Z.C. and J.T.; Investigation, Y.S., Z.Z. (Zhixiao Zhang), C.L., Y.W., H.S. and B.F.; Resources, S.W., B.F., and J.T.; Data curation, Y.S., Z.Z. (Zhixiao Zhang), Y.W. and H.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.S. and J.T.; Writing—review & editing, Y.S., S.W., H.S., Z.C., Z.Z. (Zhendong Zhu) and J.T.; Visualization, Y.S. and C.L.; Supervision, C.L. and J.T.; Project administration, Z.Z. (Zhixiao Zhang) and B.F.; Funding acquisition, B.F. and J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Hebei (21326305D), China Agricultural Research System (CARS-08-G3), National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFD1600601-10), Hebei Agriculture Research System (HBCT2023050205), and Hebei Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences Grain and Oil Crop Research Institute Youth Innovation Fund (2024LYS04).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pandey, A.K.; Burlakoti, R.R.; Kenyon, L.; Nair, R.M. Perspectives and Challenges for Sustainable Management of Fungal Diseases of Mungbean [Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek var. radiata]: A Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keatinge, J.D.H.; Easdown, W.J.; Yang, R.Y.; Chadha, M.L.; Shanmugasundaram, S. Overcoming chronic malnutrition in a future warming world: The key importance of mungbean and vegetable soybean. Euphytica 2011, 180, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, A.; Chaturvedi, S.K.; Tomar, R.; Rajan, N.; Malviya, N.; Thudi, M.; Saabale, P.R.; Prajapati, U.; Varshney, R.K.; Singh, N.P. Marker-assisted introgression of resistance to fusarium wilt race 2 in Pusa 256, an elite cultivar of desi chickpea. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2017, 292, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Sun, S.; Zhu, L.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Z. Confirmation of Fusarium oxysporum as a causal agent of mung bean wilt in China. Crop Prot. 2019, 117, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; He, W.; He, T.; Wu, Q.; Miao, Y. Combined De Novo Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis of Common Bean Response to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, D.; Ferriello, F.; Puopolo, G.; Zoina, A.; D’Esposito, D.; Tardella, L.; Ferrarini, A.; Ercolano, M.R. Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. radicis-lycopersici induces distinct transcriptome reprogramming in resistant and susceptible isogenic tomato lines. Inherit. Quant. Trait. Locus Mapp. Fusarium 2016, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, C.S.; Fonseca, M.E.d.N.; Oliveira, V.R.; Boiteux, L.S.; Reis, A. A single dominant gene/locus model for control of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lactucae race 1 resistance in lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Euphytica 2019, 215, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Xu, J.; Xu, X.; Xu, Q.; Chen, X. Inheritance and Quantitative Trait Locus Mapping of Fusarium Wilt Resistance in Cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deol, J.K.; Sharma, S.P.; Rani, R.; Kalia, A.; Chhuneja, P.; Sarao, N.K. Inheritance analysis and identification of SSR markers associated with fusarium wilt resistance in melon. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ulloa, M.; Duong, T.; Roberts, P.A. Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping of Multiple Independent Loci for Resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum Races 1 and 4 in an Interspecific Cotton Population. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cenci, A.; Rouard, M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W.; Zheng, S.-J. Transcriptomic analysis of resistant and susceptible banana corms in response to infection by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, G. Current status of the taxonomic position of Fusarium oxysporum formae specialis cubense within the Fusarium oxysporum complex. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011, 11, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Zhi, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, J.; Duan, C.; Wu, X.; Wang, X. An Emerging Disease Caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola Threatens Mung Bean Production in China. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vani, M.S.; Kumar, S.; Gulya, R. In vitro evaluation of fungicides and plant extracts against Fusarium oxysporum causing wilt of mungbean. Pharma Innov. J. 2019, 8, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Zhu, L.; Sun, F.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Z. Pathotype diversity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. mungcola causing wilt on mungbean (Vigna radiata). Crop Pasture Sci. 2020, 71, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. Fusarium Species Associated with Grain Sorghum and Mungbean in Queensland. Master’s Thesis, The University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia, 2018. Available online: http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:716902 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Wang, B.; Dale, M.L.; Kochman, J.K.; Obst, N.R. Effects of plant residue, soil characteristics, cotton cultivars and other crops on fusarium wilt of cotton in Australia. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1999, 39, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.M.; Colyer, P.D.; Rothrock, C.S.; Kochman, J.K. Fusarium Wilt of Cotton: Population Diversity and Implications for Management. Plant Dis. 2006, 90, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.J. The Effects of Crop Rotation with Wheat on the Incidence of Fusarium Wilt of Cotton in Australia. In Proceedings of the 2006 Beltwide Cotton Conferences, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–6 January 2006; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, A.M.; Araújo, S.d.S.; Rubiales, D.; Vaz Patto, M.C. Fusarium Wilt Management in Legume Crops. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, R.J. Management of tomato diseases caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Crop Prot. 2015, 73, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.S.; Spurgeon, D.W.; DeTar, W.R.; Gerik, J.S.; Hutmacher, R.B.; Hanson, B.D. Efficacy of Four Soil Treatments Against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum Race 4 on Cotton. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panth, M.; Hassler, S.C.; Baysal-Gurel, F. Methods for Management of Soilborne Diseases in Crop Production. Agriculture 2020, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, O.D.; Netto, R.A.C. Reservoir and Non-reservoir Hosts of Bean-Wilt Pathogen, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli. J. Phytopathol. 2008, 149, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanogo, S.; Zhang, J. Resistance sources, resistance screening techniques and disease management for Fusarium wilt in cotton. Euphytica 2016, 207, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.C.; Suresh, M.; Singh, B. Evaluation of Trichoderma species against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris for integrated management of chickpea wilt. Biol. Control 2007, 40, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Fan, B.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Su, Q.; Shi, H.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Identification and Screening for Resistance Germplasm Resources to Fusarium Wilt in Mungbean. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2022, 23, 1660–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, J. Fusarium wilt of peas (a review). Agronomie 1994, 14, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClendon, M.T.; Inglis, D.A.; McPhee, K.E.; Coyne, C.J. DNA markers linked to Fusarium wilt race 1 resistance in pea. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 127, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajal-Martìn, M.J.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Genomic Location of the Fw Gene for Resistance to Fusarium Wilt Race 1 in Peas. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubara, P.A.; Inglis, D.A.; Muehlbauer, F.J.; Coyne, C.J. A novel RAPD marker linked to the Fusarium wilt race 5 resistance gene (Fwf) in Pisum sativum. Pisum Genet. 2002, 34, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, C.J.; Inglis, D.A.; Whitehead, S.J.; McClendon, M.T.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Chromosomal location of Fwf, the Fusarium wilt race 5 resistance gene in Pisum sativum. Pisum Sativum 2000, 32, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Phee, K.E.; Inglis, D.A.; Gundersen, B.; Coyne, C.J. Mapping QTL for Fusarium wilt Race 2 partial resistance in pea (Pisum sativum). Plant Breed. 2012, 131, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Sun, S.; Wu, W.; Duan, C.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Z. Fine mapping and identification of a Fusarium wilt resistance gene FwS1 in pea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekeoglu, M.; Tullu, A.; Kaiser, W.J.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Inheritance and Linkage of Two Genes that Confer Resistance to Fusarium Wilt in Chickpea. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 1247–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.; Hajj-Moussa, E.; Kharrat, M.; Moreno, M.T.; Millan, T.; Gil, J. Two genes and linked RAPD markers involved in resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Ciceris race 0 in chickpea. Plant Breed. 2003, 122, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos, M.J.; Fernández, M.J.; Rubio, J.; Kharrat, M.; Moreno, M.T.; Gil, J.; Millán, T. A linkage map of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) based on populations from Kabuli × Desi crosses: Location of genes for resistance to fusarium wilt race 0. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Kumar, J.; Smithson, J.B.; Haware, M.P. Complementation between genes for resistance to race 1 of Fusarium oxyspomm f. sp. ciceri in chickpea. Plant Pathol. 1987, 36, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.D.; Winter, P.; Kahl, G.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Molecular mapping of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris race 3 resistance gene in chickpea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullu, A.; Muehlbauer, F.J.; Simon, C.J.; Mayer, M.S.; Kumar, J.; Kaiser, W.J.; Kraft, J.M. Inheritance and linkage of a gene for resistance to race 4 of fusarium wilt and RAPD markers in chickpea. Euphytica 1998, 102, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumber, R.K.; Kumar, J.; Hanaware, M.P. Inheritance of resistance to fusarium wilt in chickpea. Plant Breed. 1995, 114, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.D.; Chen, W.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Genetics of Chickpea Resistance to Five Races of Fusarium Wilt and a Concise Set of Race Differentials for Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris. Plant Dis. 2005, 89, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.D.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Fusarium wilt of chickpea: Physiological specialization, genetics of resistance and resistance gene tagging. Euphytica 2007, 157, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, H.; Brick, M.A.; Schwartz, H.F.; Panella, L.W.; Byrne, P.F. Inheritance of Resistance to Fusarium Wilt in Two Common Bean Races. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamwieh, A.; Udupa, S.M.; Choumane, W.; Sarker, A.; Dreyer, F.; Jung, C.; Baum, M. A genetic linkage map of Lens sp. based on microsatellite and AFLP markers and the localization of fusarium vascular wilt resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.d.M.; Sultana, F.; Mostafa, M.; Khan, I.; Tran, L.-S.P.; Mostofa, M.G. Reinforced Defenses: R-Genes, PTI, and ETI in Modern Wheat Breeding for Blast Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdowell, J.M.; Simon, S.A. Recent insights into R gene evolution. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Niu, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Yin, W.; Xia, X. PTI-ETI synergistic signal mechanisms in plant immunity. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2113–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Mine, A.; Bethke, G.; Igarashi, D.; Botanga, C.J.; Tsuda, Y.; Glazebrook, J.; Sato, M.; Katagiri, F. Dual Regulation of Gene Expression Mediated by Extended MAPK Activation and Salicylic Acid Contributes to Robust Innate Immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1004015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Somssich, I.E. Transcriptional networks in plant immunity. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 932–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, G.; Groenendijk, J.; Wijbrandi, J.; Reijans, M.; Groenen, J.; Diergaarde, P. Dissection of the Fusarium I2 Gene Cluster in Tomato Reveals Six Homologs and One Active Gene Copy. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cendales, Y.; Catanzariti, A.-M.; Baker, B.; Mcgrath, D.J.; Jones, D.A. Identification of I7 expands the repertoire of genes for resistance to Fusarium wilt in tomato to three resistance gene classes: Tomato I7 gene for Fusarium wilt resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotman, Y.; Normantovich, M.; Goldenberg, Z.; Zvirin, Z.; Kovalski, I.; Stovbun, N.; Doniger, T.; Bolger, A.M.; Troadec, C.; Bendahmane, A.; et al. Dual Resistance of Melon to Fusarium oxysporum Races 0 and 2 and to Papaya ring-spot virus is Controlled by a Pair of Head-to-Head-Oriented NB-LRR Genes of Unusual Architecture. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzariti, A.; Lim, G.T.T.; Jones, D.A. The tomato I-3 gene: A novel gene for resistance to Fusarium wilt disease. New Phytol. 2015, 207, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, S.; Ma, J.; Shi, W.; Qin, T.; Xi, H.; Nie, X.; You, C.; Xu, Z.; et al. A Single-Nucleotide Mutation in a GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE Gene Confers Resistance to Fusarium Wilt in Gossypium hirsutum. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Sun, F.; Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Z. Transcriptome Analysis of Resistance to Fusarium Wilt in Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 679629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Ge, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Blair, M.W. Hairy root transgene expression analysis of a secretory peroxidase (PvPOX1) from common bean infected by Fusarium wilt. Plant Sci. 2017, 260, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Guo, X. The cotton MAPK kinase GhMPK20 negatively regulates resistance to Fusarium oxysporum by mediating the MKK4-MPK20-WRKY40 cascade: GhMPK20 regulates resistance to F. oxysporum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 1624–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, E.S.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, S.; Feng, Z.; Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; et al. A chitinase CsChi23 promoter polymorphism underlies cucumber resistance against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 1471–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Molina, A. Ethylene Response Factor 1 Mediates Arabidopsis Resistance to the Soilborne Fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.P.; Badruzsaufari, E.; Schenk, P.M.; Manners, J.M.; Desmond, O.J.; Ehlert, C.; Maclean, D.J.; Ebert, P.R.; Kazan, K. Antagonistic Interaction between Abscisic Acid and Jasmonate-Ethylene Signaling Pathways Modulates Defense Gene Expression and Disease Resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 3460–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delessert, C.; Kazan, K.; Wilson, I.W.; Straeten, D.V.D.; Manners, J.; Dennis, E.S.; Dolferus, R. The transcription factor ATAF2 represses the expression of pathogenesis-related genes in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005, 43, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, K.C.; Dombrecht, B.; Manners, J.M.; Schenk, P.M.; Edgar, C.I.; Maclean, D.J.; Scheible, W.-R.; Udvardi, M.K.; Kazan, K. Repressor- and Activator-Type Ethylene Response Factors Functioning in Jasmonate Signaling and Disease Resistance Identified via a Genome-Wide Screen of Arabidopsis Transcription Factor Gene Expression. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semagn, K. Leaf Tissue Sampling and DNA Extraction Protocols. Mol. Plant Taxon. 2014, 1115, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Maia, L.C.; Palmieri, D.A.; De Souza, V.Q.; Kopp, M.M.; De Carvalho, F.I.F.; Costa De Oliveira, A. SSR Locator: Tool for Simple Sequence Repeat Discovery Integrated with Primer Design and PCR Simulation. Int. J. Plant Genom. 2008, 2008, 412696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; Fan, B.; Xu, D.; Wu, J.; Cao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; et al. High-quality genome assembly and pan-genome studies facilitate genetic discovery in mung bean and its improvement. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, R.; Anandalakshmi, R.; Liu, Y.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. The tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene. N. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 3, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kwon, S.I.; Saha, D.; Anyanwu, N.C.; Gassmann, W. Resistance to the Pseudomonas syringae Effector HopA1 Is Governed by the TIR-NBS-LRR Protein RPS6 and Is Enhanced by Mutations in SRFR1. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Fang, H.; Peng, L.; Wei, S.; Li, C.; Zheng, S.; Lu, J. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals resistance-related genes and pathways in Musa acuminata banana “Guijiao 9” in response to Fusarium wilt. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 141, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Van Nocker, S.; Tu, M.; Fang, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Overexpression of VqWRKY31 enhances powdery mildew resistance in grapevine by promoting salicylic acid signaling and specific metabolite synthesis. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Lin, H. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.M.; Ferguson, J.N.; Gardiner, M.; Green, P.; Hubbard, A.; Moscou, M.J. Isolation and fine mapping of Rps6: An intermediate host resistance gene in barley to wheat stripe rust. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.; Kale, S.D.; Liu, T.; Tang, Q.; Wang, X.; Arredondo, F.D.; Basnayake, S.; Whisson, S.; Drenth, A.; Maclean, D.; et al. Different Domains of Phytophthora sojae Effector Avr4/6 Are Recognized by Soybean Resistance Genes Rps 4 and Rps 6. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, M.; Iwamoto, N.; Kubo, Y.; Morimoto, T.; Takagi, H.; Takahashi, F.; Nishiuchi, T.; Tanaka, K.; Taji, T.; Kaminaka, H.; et al. Arabidopsis SMN2/HEN2, Encoding DEAD-Box RNA Helicase, Governs Proper Expression of the Resistance Gene SMN1/RPS6 and Is Involved in Dwarf, Autoimmune Phenotypes of mekk1 and mpk4 Mutants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.