Abstract

Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) cultivation in Italy is facing constraints related to climate change, causing decreases in production as a consequence of summer droughts and late spring heatwaves. This two-year study (2024–2025, i.e., Y1 and Y2) evaluated the effectiveness of two biostimulant protocols on the eco-physiological and productive performance of a hazelnut orchard (cv ‘Tonda Gentile Romana’) in Central Italy. Treatment A included a mixture of formulations (silicon, Ecklonia maxima and microalgae), while Treatment B featured an Ecklonia maxima-containing biostimulant. Data-gathering combined ground-level measurements and remote-sensing technologies, which allowed for the extraction and assessment of vegetation indexes such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), the Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE) and the Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI). Treatments A and B successfully maintained higher chlorophyll content; this beneficial effect was validated by the NDVI, but the NDRE might have suffered from soil interference due to its high sensitivity. The NDMI was positively influenced by both treatments. Treatment A brought to a remarkable production increase in both seasons, especially in Y1 with 7.75 kg plant−1 (+40% vs. Control) and without negatively affecting the shell/nut ratio. These findings suggest that biostimulants could represent an effective strategy for improving productivity and enhancing abiotic stress resilience in hazelnut cultivation.

1. Introduction

The European hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) represents a globally significant nut crop, valued for its wide environmental adaptability and the remarkable organoleptic and nutritional qualities of its kernels. Hazelnut cultivation in Italy has been going through a remarkable surge in the past decade, especially in terms of land use, which expanded both in well-established productive districts, such as Latium, Campania and Piedmont, and novel areas like the Basilicata, Calabria, Lombardy, Tuscany, Umbria and Veneto regions [1]. As of 2025, 95,470 hectares in Italy are devoted to European hazelnut cultivation, which accounts for a 30.4% growth in comparison to 2015 data [2]; this trend has been mainly driven by the growing demand for hazelnuts by the confectionery industry [3]. However, such expansion in terms of acreage was not always followed by an increase in total production; indeed, seasonal harvests within the 2021–2025 time frame have been recorded to be, on average, 19.45% less abundant than the total production harvested every year from 2015 to 2020 (106,657 t and 132,419 t, respectively) [2]. These impactful drops in domestic production were mainly caused by the negative impact of abiotic stresses, namely extreme temperatures and prolonged drought, which represent a common threat for all the major countries contributing to hazelnut cultivation [4,5]. It is well known, in fact, that temperatures above +35 °C can trigger stomata closure and photooxidation phenomena, while failure to meet the crop’s adequate watering requirements (i.e., 80–100 mm/month from April to August) may result in stunted production [6,7]. Finding novel agronomic tools that can effectively prevent abiotic stresses to dramatically impact hazelnut cultivation represents an urgent goal to accomplish. In this context, plant biostimulants might represent a promising innovation. As stated by European Regulation 2019/1009, a biostimulant is a product that stimulates plant metabolic processes independently of its nutrient content, with the sole aim of improving nutrient use efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stress, quality traits or the availability of confined nutrients in the soil or rhizosphere [8].

Biostimulants have gained remarkable attention from scientists and growers, especially in annual crop cultivation, with less consideration being paid to their potential in perennial species [9,10,11]. Studies evaluating biostimulant application on C. avellana are even more scarce, leaving little evidence regarding the usefulness of this practice in hazelnut cultivation: Cabo et al. [12] witnessed that kaolin and seaweed extracts were effective in increasing relative water content and enhancing water use efficiency in hazelnut, while another study conducted by Rovira et al. [13] highlighted significant yield improvements, albeit inconsistent across seasons, in a selection of hazelnut cultivars upon distributing a commercial seaweed extract. A trial involving the distribution diatomaceous earth as a source of silicon led to higher leaf-level chlorophyll concentrations and greater yield in terms of kg plant−1 [14]. Yield and qualitative traits were also found to be positively influenced by inoculating hazelnut trees with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi [15]. Finally, Pascoalino et al. [16] focused on the potential impact of a selection of biostimulants on hazelnuts’ organoleptic and nutritional properties, eventually obtaining encouraging results.

When trying to evaluate the effectiveness of biostimulant applications at a large scale (i.e., orchard-level), multispectral satellite imagery can represent a powerful resource. Computing high-resolution satellite acquisitions allow for the extraction of a wide range of bio-physical indicators, depicting the canopy current eco-physiological status in a non-destructive way [17,18]. For this reason, Vegetation Indexes (VIs) find broad usage in precision agriculture to assess key crop features like plant vigor, nutritional status and water content continuously over time [19]. Among the existing VIs, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is arguably the most common, as it represents a solid proxy for quantifying biomass and general vegetative health, albeit being susceptible to saturation in high-density canopies [20]. To overcome this limitation, more accurate VIs, like the Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE), have been proposed and successfully tested on several tree crops, such as pear [21], citrus and olive [22]. When assessing the canopy water content and its changes over time, the Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI) can be implemented as a reliable metric and can provide early detection of drought stress onset before visual symptoms occur, as demonstrated by works performed in almond [23] and olive [24].

Despite becoming an increasingly popular practice in orchard management, few examples of VIs’ application on hazelnut plants are available within the existent literature: Altieri et al. [25] successfully attempted monitoring the NDVI of a hazelnut orchard by resorting to remote-sensing technology, while other researchers [26] tested the adaptability of nine different VIs in capturing and predicting the eco-physiological status of individual hazelnut plants; however, no studies have investigated the application of VIs as a tool to assess the impact of biostimulant administration in European hazelnut orchards.

As an effort to fill this gap within the scientific literature, our study evaluates two distinct biostimulant protocols applied in a commercial hazelnut orchard in the Latium region, Central Italy, over a two-year period, by merging traditional, ground-level monitoring techniques and remote-sensing technology. This novel approach may foster the transition of hazelnut cultivation towards the innovative principles of the Agriculture 4.0 paradigm, possibly translating into a successful implementation of Variable Rate Technology (VRT) when administering biostimulants in commercial orchards.

2. Materials and Methods

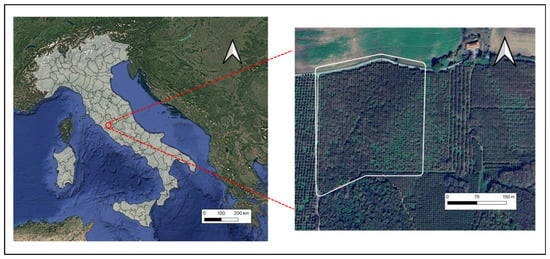

2.1. Site Description

A two-year-long trial (growing seasons 2024–2025, which will henceforth be referred to as Y1 and Y2) was carried out on a private European hazelnut orchard, held and managed by Tenuta Longinotti—Società Agricola Vico, and located in Ronciglione (Viterbo, Latium, Italy; 42°17′46.0″ N 12°10′02.1″ E; 643 m a.s.l.) (Figure A1). Soil analyses on the 0–30 cm layer highlighted a rather homogeneous profile throughout the orchard, with electrical conductivity (EC) values ranging from ~4 to ~16 mS m−1 (Figure A2) as detected using the ElectroMagnetic Interference (EMI) sensor GF Mini Explorer, by GF Instruments (Brno, Czech Republic). The soil of the experimental plots had a clay loam texture with an organic carbon content of 1.8% at a depth of 0–30 cm and sub-acid soil reaction. The orchard was composed of 35-year-old plants belonging to the ‘Tonda Gentile Romana’ cultivar, grown according to the multi-stem bush training system. The plantation was characterized by a 5 m × 5 m planting layout, ultimately resulting in ~400 plants ha−1, not irrigated and managed with standard orchard management techniques—namely, the soil was managed with a natural green cover crop, and annually, the orchard received applications of the following quantities of main fertilizers: 90 kg ha−1 nitrogen, 60 kg ha−1 phosphorus and 90 kg ha−1 potassium. Orchard management and integrated pest and disease control were also carried out yearly by the grower according to the guidelines of the current regional Rural Development Plan.

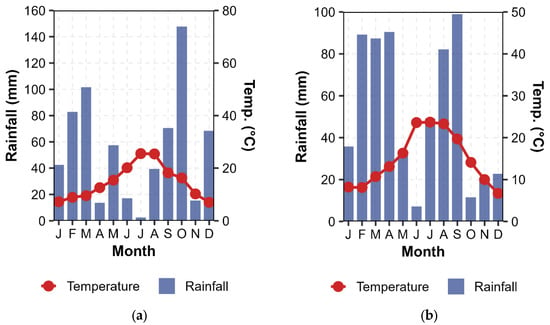

The agrometeorological outlook that shaped the two growing seasons was monitored by taking advantage of a fully equipped agrometeorological station (TERRASENSE AS100-AS300, Terrasystem s.r.l., Viterbo, Italy), installed near the farm center. Climographs depicting the climatological outlook of the two experimental seasons are reported in Figure A3a,b.

On-field activities such as eco-physiological data acquisition and manual harvest were conducted between late May and early September both in Y1 and Y2, while satellite multi-spectral imagery manipulation encompassed a time frame which extended from April to September for each experimental year.

Within each experimental plot, three checking plants (deemed as representative of the whole orchard, and not vulnerable to spray drift from neighboring plots) were identified and used for in planta measurements throughout the biennial trial.

2.2. Biostimulant Treatments

The hazelnut orchard was divided into three experimental plots, each having an area of roughly 2 ha (Figure A4). Two plots were subjected to two different biostimulant treatments (henceforth referred to as A and B, respectively), while the third served as an untreated control (i.e., C). Treatments were carried out by using a selection of four biostimulants, all of them professional formulations that are available for purchase as fertilizing products. Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview regarding the tested biostimulant products.

Interventions were performed by the orchard personnel with the aid of a towed sprayer in a 500 L ha−1 water solution. Treatment A was characterized by a mixture of three different biostimulant formulations, which were conjoined in a single solution and administered along three distinct interventions for each experimental year (23 May, 26 June and 9 August for Y1, and 26 May, 26 June and 8 August for Y2), thus intercepting the following phenological stages: fruit set, visible clusters and final nut size; Treatment B, on the other hand, was administered once per season, during the first seasonal administration event in late May (fruit set).

Timings and numbers of interventions were planned according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. In particular, Treatment A was composed of a series of products which are recommended to be sprayed prior to abiotic stress insurgence, hence the repeated administration throughout the productive season. Treatment B was administered in a single intervention, 2–3 weeks before fruit set, since that is the phenological stage at which the formulation is the most effective in delivering its claim, as stated by the product guidelines.

2.3. Eco-Physiological Measurements

The selected plants were regularly subjected to eco-physiological monitoring through non-destructive, leaf-level measurements performed with a handheld, portable optic sensor (Dualex®, Force-A, Orsay, France, no longer in business). Hence, data concerning chlorophyll and flavonol content (µg cm−2) and the Nitrogen Balance Index (NBI®, expressed as the ratio between chlorophyll and flavonol contents) were acquired. Within each plant, measurements were performed as follows: two readings per cardinal point (North, West, East, South), one on the inner portion of the canopy and another on the outer part (n = 8). Throughout each experimental year, four reading sessions were executed. The timing of measurements was planned in order to capture data at specific phenological stages (Table 2), determined according to the BBCH coding guidelines issued for C. avellana, referring to development of fruit (code 7) and ripening or maturity of the fruit (code 8) [27].

Table 2.

Phenological stages (description and BBCH coding) intercepted by field Dualex® readings in Y1 and Y2.

2.4. Bio-Physical Indexes via Remote Sensing

Elaborations relying on remote sensing were performed by acquiring multispectral satellite images from European Sentinel-2 satellites, hosted in the Copernicus Earth observation program (https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu/ accessed on 10 April 2024). For the sake of this experimental trial, three different bio-physical indexes were computed and analyzed in a continuous way, upon discarding cloudy and foggy days through visual inspection. All the elaborations have been performed on Bottom-of-Atmosphere (BOA) spectral bands (labeled as Level 2-A for Sentinel-2) as they exclude any atmospheric interference in reflectance values.

2.4.1. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

The NDVI gives an estimation of the eco-physiological status of the depicted vegetation, by evaluating red and near-infrared (NIR) reflectance, ultimately resulting in a “greenness” index ranging from −1 to +1. It is calculated by applying Equation (1) [28]:

where B08 and B04, respectively, stand for the NIR band (λ = 842 nm, res = 10 m × 10 m) and for the red band (λ = 665 nm, res = 10 m × 10 m).

NDVI = (B08 − B04)/(B08 + B04)

NDVI elaborations were performed by processing satellite acquisitions falling into the April–September and March–September time frame for Y1 and Y2, respectively.

2.4.2. Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE)

The NDRE index represents an alternative metric to the NDVI, and it is tightly correlated with the chlorophyll content within the crop. It ranges from −1 to +1. Being less prone to saturation, the NDRE enables a more detailed spatial characterization of the canopy. Values were calculated through Equation (2) [29]:

where B05 indicates the red edge band (λ = 705 nm, res = 20 m × 20 m).

NDRE = (B08 − B05)/(B08 + B05)

Acquisitions involving NDRE extraction encompassed a period that ranged from early July to Late August in Y1 and from early July to early September in Y2.

2.4.3. Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI)

The NDMI can be considered a robust and reliable proxy of vegetation water content and serves as a tool to remotely detect potential water stress within the crop. It ranges from −1 to 1, and it can be calculated by applying Equation (3) [30]:

where B11 is the band related to short-wave infrared (SWIR, λ = 1610 nm, res = 20 m × 20 m).

NDMI = (B08 − B11)/(B08 + B11)

NDMI values were extracted according to the same calendarization followed for the NDRE elaborations.

2.4.4. NDVI/NDRE/NDMI Data Processing

Raw data were processed by using QGIS software ver. 3.42.3 (QGIS Development Team, 2024) [31]. Here, geo-referenced polygons depicting the three experimental parcels were used as a reference to compute the necessary bands and to extract the three indexes at the plot level. Bands 05 and 11, natively available at 20 m × 20 m resolution, were resampled by using the Resample (warp) processing algorithm and resampled to a 10 m × 10 m resolution (Cubic B-Spline resample method) before calculating the metrics and exporting graphical outputs. Pixel-level data were subsequently exported and aggregated according to day and plot in order to assess the evolution of the three indexes over time.

2.5. Production, Nut and Kernel Traits and Defect Frequency Assessment

Plants that were subjected to in planta readings were manually harvested in the first half of September for both Y1 and Y2. Hazelnuts were gathered in baskets and dried and weighed in the lab using an electronic scale. At the end of the harvest campaigns, data concerning parcel-level productions (t ha−1) were made available.

During the manual harvest sessions, aliquots of fifty hazelnuts per plant were taken and used to determine nut and kernel traits (nut weight, shell weight, kernel weight and kernel/nut ratio) according to literature protocols; the same aliquots were also processed to assess the incidence of the main commercial defects (i.e., empty shell, black shell, shrunk kernel, deformed kernel, double kernel and black tip).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data originating from in planta eco-physiological monitoring, as well as manual harvesting and nut and kernel trait evaluation, were analyzed by performing a one-way ANOVA with the biostimulant treatment as the independent variable (α = 0.05). Data belonging to Y1 and Y2 were analyzed independently. For Dualex® readings, each data point was individually analyzed to detect any significant differences among groups within the same measurement session. When analyzing percentage data (i.e., kernel/nut ratio and defect incidence), the data were processed through logarithmic transformation before subjecting them to ANOVA. Finally, statistically significant differences were further investigated by performing a post hoc test (i.e., Tukey test).

Plot-level NDVI/NDRE/NDMI values were investigated through a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (KS test); this statistical analysis compares the distribution of two series of data and detects significant variations in the way the two series are distributed. Pairwise comparisons were conducted between the treatments (Treatment A vs. C and Treatment B vs. C) utilizing the full, non-aggregated dataset containing raw pixel values extracted from the regions of interest. For each index, the KS test was run on values ranging from July 6th and August 30th for Y1, and from 6th July and 1st September for Y2. Data distributions were deemed to be significantly different by applying the following threshold: α = 0.05.

All analyses were performed by resorting to the R statistical software ver. 4.4.3 (R core team, Wien, Austria) [32].

3. Results

3.1. Leaf Eco-Physiological Measurements

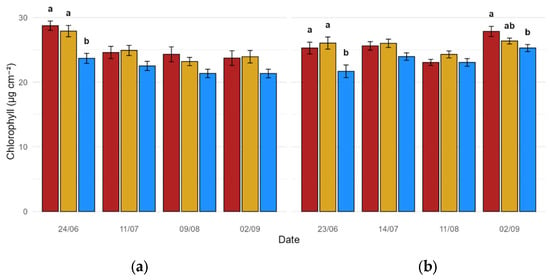

Statistical analyses concerning leaf pigments were carried out by performing one-way ANOVA on each reading session independently. Leaf pigments were shown to significantly respond to biostimulant treatments consistently throughout Y1 and Y2. Chlorophyll content showed a tendency of consistently being more abundant in treated plants, especially on the first seasonal readings, where such an increment was proven to be statistically significant (p < 0.001 and p = 0.004 for Y1 and Y2, respectively) when compared to Control data (Figure 1a,b); another significant comparison was detected in Y2 on the last day of measurements, where Treatment A confirmed its capability of keeping chlorophyll concentration significantly higher within leaves (p = 0.015, Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Chlorophyll content (µg cm−2) aggregated by date and treatment (red: Treatment A; gold: Treatment B; blue: Treatment C): (a) Y1; (b) Y2. Data expressed as mean values (n = 24, 8 measurements on 3 biological replicates per treatment). Bars represent the standard deviation (SD). Different lowercase letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences based on Tukey’s post hoc test (α = 0.05).

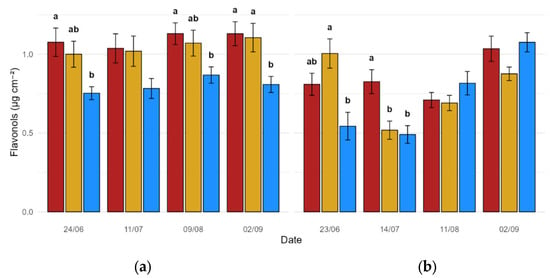

Leaf-level flavonol concentration was found to significantly react to the administration of biostimulant formulations in both experimental years (Figure 2a,b). This was reported to be especially true for Y1, where almost every data point featured meaningful variations among Treatments A, B and C, with the former consistently leading to significantly higher flavonol concentrations in comparison to untreated plants (p = 0.008, p = 0.02 and p = 0.005 for 24 June, 9 August and 2 September, respectively). This phenomenon was partly validated by Y2 data (Figure 2b), where the first two measurement sessions highlighted a significant effect to be ascribed to biostimulant application (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001 for 23 June and 14 July, respectively).

Figure 2.

Flavonol content (µg cm−2) aggregated by date and treatment (red: Treatment A; gold: Treatment B; blue: Treatment C): (a) Y1; (b) Y2. Data expressed as mean values (n = 24, 8 measurements on 3 biological replicates per treatment). Bars represent the standard deviation (SD). Different lowercase letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences based on Tukey’s post hoc test (α = 0.05).

While the Nitrogen Balance Index (NBI) did not seem to significantly respond to biostimulants during the first research year (Figure 3a), Y2 featured more of a heterogeneous outlook, where NBI values went through a transversal drop throughout the season (Figure 3b). More specifically, Treatment A led to significantly lower NBI metrics than the Control on 23 June (p = 0.008), and to Treatment B too on the following measurement date (p = 0.007).

Figure 3.

Nitrogen Balance Index (NBI, dimensionless) aggregated by date and treatment (red: Treatment A; gold: Treatment B; blue: Treatment C): (a) Y1; (b) Y2. Data expressed as mean values (n = 24, 8 measurements on 3 biological replicates per treatment). Bars represent the standard deviation (SD). Different lowercase letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences based on Tukey’s post hoc test (α = 0.05).

3.2. Bio-Physical Indexes via Remote Sensing

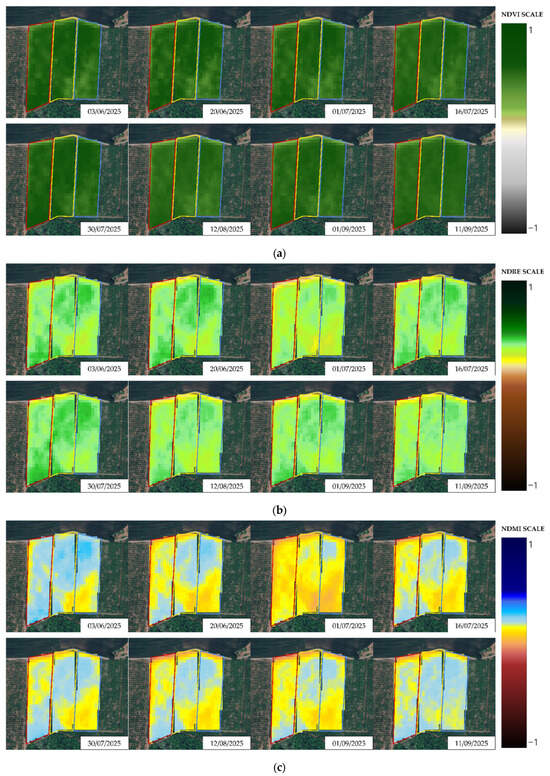

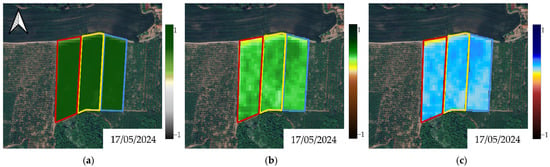

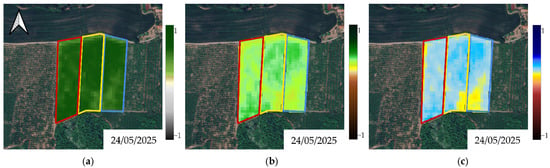

A series of graphical representations of the pre-treatment conditions of the experimental plots for Y1 and Y2, as represented by the NDVI, NDRE and NDMI, can be seen in Figure A5 and Figure A6. Graphical temporal progressions of the bio-physical metrics on a selection of acquisitions are depicted for visual evaluation in Figure 4a–c and Figure 5a–c. As a general trend, by looking at the outlook that shaped Y1, the eco-physiological status of the three plots went through a consistent worsening, which was successfully detected by all indexes (Figure 4a–c). This tendency was less evident and less coherent in Y2, where fluctuations and temporary improvements were found, for example, on 31 July 2025 and 1 July 2025 for NDRE and NDMI, respectively (Figure 5a–c).

Figure 4.

Temporal progression of (a) NDVI, (b) NDRE and (c) NDMI depicted through a selection of dates in Y1. Red: Treatment A; yellow: Treatment B; blue: Treatment C.

Figure 5.

Temporal progression of (a) NDVI, (b) NDRE and (c) NDMI depicted through a selection of dates in Y2. Red: Treatment A; yellow: Treatment B; blue: Treatment C.

Bio-physical indexes were investigated by running a Kolmogorov–Smirnov analysis, a non-parametric statistical test which can detect significant shifts within the temporal distribution of two data series (α = 0.05). Through this approach, the divergence between the temporal profiles of the treated (A, B) and untreated (C) plots was assessed.

In both years, the NDVI values were very similar across the three treatments in the early months of the growing season (Figure 6a,b); however, in Y1, the KS test performed throughout the critical part of the two growing seasons highlighted a progressive differentiation. In particular, Y1 was subjected to a steady drop in NDVI values, regardless of treatment; moreover, the data distribution that shaped Control data was found to proceed in a significantly different fashion in comparison to parcel A; indeed, C values were found to be consistently lower and resulted in a statistically significant A vs. C contrast (p = 0.01, Figure 6a). Such behavior, although sharing general similarities, did not result in any statistically meaningful difference in Y2.

Figure 6.

Temporal evolution of parcel-level NDVI values for Treatment A (red), Treatment B (gold) and Treatment C (blue) during (a) Y1 and (b) Y2. Data expressed as mean values (n ≥ 250 pixels per treatment). The dashed lines encompass the time frame considered for the execution of the KS test.

A very similar pattern was observed upon analyzing the progression of the NDRE index over the course of the most challenging phase of the season (Figure 7a,b), with a coherent trend in comparison to NDVI data (Figure 6a,b), but lower values because of the superior sensitivity of this metric. In both years, NDRE values went through a generalized decrease, which occurred regardless of treatment typology. On the other hand, the evolution followed by this bio-physical index varied from Y1 to Y2: in fact, while both treatments were proven to significantly differ from the Control, only Treatment B resulted in higher NDRE values in both years, with Treatment A significantly underperforming in Y2 (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Temporal evolution of parcel-level NDRE values for Treatment A (red), Treatment B (gold) and Treatment C (blue) during (a) Y1 and (b) Y2. Data expressed as mean values (n ≥ 250 pixels per treatment). The dashed lines encompass the time frame considered for the execution of the KS test.

Finally, NDMI calculations allowed for an estimation of the crop’s water content and its variation over time, especially during the most demanding phases of the productive cycle (Figure 8a,b).

Figure 8.

Temporal evolution of parcel-level NDMI values for Treatment A (red), Treatment B (gold) and Treatment C (blue) during (a) Y1 and (b) Y2. Data expressed as mean values (n ≥ 250 pixels per treatment). The dashed lines encompass the time frame considered for the execution of the KS test.

Values at the beginning of the considered interval were recorded to be close to 0.175 across all treatments in both seasons, but subsequently underwent a general decrease, eventually reaching values below 0.1 for Treatment C in Y1. This generally decreasing trend was found to progress in a significantly different manner between the three groups. Untreated plants consistently showed lower NDMI values in comparison to treated plots: this difference was detected to be statistically significant for both A vs. C and B vs. C comparisons, both for Y1 and Y2.

3.3. Production, Nut and Kernel Traits and Defect Frequency Assessment

Figure 9a,b depict the seasonal trends of the manual harvest performed on the checked plants during both seasons. In addition, Table 3 hosts plot yield values in terms of tons per hectare, provided by the farm personnel at the end of the company’s harvesting campaigns. On a general view, both plant-level and plot-level data highlighted a systematic drop in production (−48.5% across all treatments). On the other hand, within the same experimental year, biostimulant treatments were reported to significantly influence plants’ production in Y1 as well as Y2 (p = 0.003 and p = 0.008, respectively): in this context, Treatment A consistently led to the highest amount of produce per plant (i.e., 7.75 kg plant−1 in Y1 and 3.77 kg plant−1 in Y2, respectively), significantly outperforming both Treatment B and C in the first season (Figure 9a). Along with the generalized decrease in yields, differences between Treatment A and B turned from significant to negligible in Y2 (Figure 9b), the latter characterized by a general decline in production due to significant infestations of brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys), which severely affected the entire local hazelnut-growing area.

Figure 9.

Gross productions in terms of kilograms per plant for Treatment A (red), Treatment B (gold) and Treatment C (blue) sorted by (a) Y1 and (b) Y2. Data expressed as mean values (n = 3 plants per treatment). Bars represent the standard deviation (SD). Different lowercase letters above the error bars denote statistically significant differences based on Tukey’s post hoc test (α = 0.05).

Table 3.

Parcel-level gross productions sorted by year and treatment, according to data gathered by the company personnel. Values are expressed in tons per hectare.

When looking at hazelnuts’ carpological traits, several parameters seemed to significantly respond to treatments (Table 4). Statistically meaningful differences were detected especially for nut, kernel and shell weight: in Y1, untreated plants seemed to produce the heaviest hazelnuts according to these three parameters (p < 0.001); however, this tendency was reversed in Y2, where plants administered with Treatment A yielded significantly heavier hazelnuts in terms of nut and shell weight (p < 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). On the other hand, it is worth noting that the most important carpological parameter for commercial purpose, i.e., the kernel/nut ratio, failed to significantly react to biostimulant treatments, regardless of experimental year. The impact of treatments was also found to be negligible in terms of defect incidence, where aggregated data, despite showing traces of heterogeneity, did not result in any significant outcome according to the analysis of variance.

Table 4.

Carpological outlook of examined hazelnuts, based on harvested aliquots, in terms of nut weight, kernel weight, shell weight, kernel/nut ratio and defect incidence, sorted by year and treatment. Data expressed as mean values (n = 150, 50 nuts for 3 plants per treatment). Values after the ± symbol represent the standard deviation (SD). Different superscript letters next to SD denote statistically significant differences based on Tukey’s post hoc test (α = 0.05).

4. Discussion

Results from leaf eco-physiological monitoring highlighted distinguishable tendencies in terms of chlorophyll content, which followed a similar trend in both experimental seasons. In this regard, our findings suggest a positive impact to be ascribed to Treatment A (silicon + seaweed/auxins + microalgae), which likely increased chlorophyll buildup within leaves before the critical stages of fruit ripening (Figure 1a), as already reported in hazelnut and other tree species like apple [33]. Applying a conjoined mixture of plant biostimulants may help the plants better withstanding adverse climatic conditions during challenging parts of their vegetative cycle [34,35]. Seaweed-derived formulations are thought to stimulate chlorophyll biosynthesis and delay leaf senescence by directly affecting gene expression [36], while silicon has been repeatedly reported to enhance leaves’ bio-mechanic properties, thus protecting the whole leaf structure, especially when facing abiotic stresses [37]. Moreover, abiotic stresses like thermal stress and drought are tackled by plants by synthetizing secondary metabolites such as flavonols, which are capable of reinforcing the antioxidant defense machinery [38]. The higher flavonol content ensured by the biostimulant treatments in Y1 suggests that this practice was effective in increasing plants’ resilience while facing sub-optimal growing conditions (Figure A3a,b).

The NBI, which represents the ratio between chlorophyll and flavonol concentrations, gives a reliable estimation of the overall nitrogen content at the leaf level [39]. In both seasons, untreated plants recorded consistently higher NBI values than Treatments A and B, with this trend being exacerbated in the first two measurements in Y2 (Figure 3a,b). We speculate that this behavior might be explained by biostimulants causing greater flavonol accumulation within the leaves (Figure 2a,b). Moreover, the increase in productivity caused by Treatment A (Figure 9a,b) might have triggered a larger resource translocation phenomenon that involved source and sink organs, thus leading to a drop in NBI values [40].

Spatial data coming from multi-spectral satellite acquisitions provided a thorough and multi-faceted outlook regarding eco-physiological status at the parcel level and its evolution over time. NDVI and NDRE metrics were partly validated by Dualex® chlorophyll readings (Figure 1a,b), which were found to coherently follow the NDVI progression in Y1 and Y2 (Figure 6a,b), as already confirmed by previous works [41,42]. However, the correspondence between ground data and the NDRE index was found to be weaker, especially for Y2 data, where Treatment A was unexpectedly associated with lower average values across the whole analyzed time frame (Figure 7a). This result is in contradiction with other works within the literature, where the NDRE index was certified as the best predictor for crops’ chlorophyll content [43,44]. This discrepancy might be ascribed to soil background effects, exacerbated by NDRE’s increased sensitivity, which might have interfered with canopy-driven data.

Multitemporal data involving NDMI acquisitions gave insights regarding water stress onset throughout the most critical part of both seasons, where high temperatures and poor rainfall pose a threat to many physiological processes, like fruit development and ripening (Figure 8a,b). NDMI takes advantage of computing SWIR, influenced by leaf water content, internal structure and dry matter, along with NIR, which reacts only to the latter two factors [45]. Our elaborations confirm that the NDMI can represent a reliable proxy to assess plants’ water status, even in tree species, as already suggested by other works [23,24,46]. Biostimulant treatments were reported to exert an important role in keeping NDMI values higher than the ones that characterized the Control plot; this finding is in line with previously performed studies concerning biostimulant application in hazelnut trees, where seaweed extracts (present both in Treatment A and Treatment B) were shown to increase leaf relative water content (RWC) by optimizing stomatal regulation [12]. Likewise, silicon has been largely associated with drought stress mitigation strategies enforced by plants facing water limitations, as it is thought to trigger the expression of various stress-associated genes [47].

On a final note, results deriving from remote-sensing techniques might also be correlated with the heterogeneous soil properties among parcels, as highlighted by EC readings performed on the 0–30 cm horizon (Figure A2) and as already established by previous research [48].

Seasonal hazelnut productions were remarkably affected by different climatic conditions (Figure A3a,b), which led to an alternate bearing behavior within all plots. This physiological alternation is intrinsic to hazelnut cultivation, often amplified by summer droughts during the induction phase of the previous year [49]. Nevertheless, manual harvests gave clear indication of a positive effect being exerted by Treatment A, which consistently ensured more abundant production in comparison to untreated plants, in both Y1 and Y2 (Figure 9a,b). This was particularly evident in the first experimental year, where this protocol led to a ~40% increase in production. Such an effect had previously been described by other studies that evaluated the impact of seaweed-based [13,50] and silicon-based [14] biostimulants on hazelnut. Treatment A might also have caused an amplification of the sink and source dynamic, as it led to significantly smaller hazelnuts in Y1, likely as compensation for the enhanced production in terms of kg plant−1 (and t ha−1), which, however, did not result in lower kernel/nut ratios in comparison to the other treatments (Table 4). Overall, carpological traits of the ‘Tonda Gentile Romana’ hazelnut were in line with available data [51]. Similarly, commercial defects were not significantly influenced by Treatment A or Treatment B. Commercial defects in hazelnut mainly have a biotic origin, as the most important ones are derived from the trophic action of Halyomorpha halys and mold infecting the kernel. Plant biostimulants might provide extra resources for crops to become indirectly more tolerant towards biotic stresses, but this is not their main purpose [52]. Therefore, since H. halys attacks are becoming more and more detrimental for hazelnut cultivation [53], biostimulant administration might have proved to be negligible towards the mitigation of this phytosanitary issue, even in the case of silicon-containing products (Treatment A), regardless of its alleged properties in improving crops’ physical resistance against the feeding activity of herbivorous insects [54].

5. Conclusions

This biennial trial represents a robust contribution to the biostimulant discourse as it involved their application on hazelnut, a species in which these novel products have rarely been tested, despite the climatic challenges for this valuable crop becoming increasingly serious.

Leaf eco-physiological readings performed with proximal machinery certified a favorable effect deriving from Treatment A, and these findings were found to coherently fit with NDVI acquisitions, while NDRE values might have suffered from soil data interference. Both treatments, on the other hand, were deemed useful in keeping water content at higher levels in comparison to the Control plot by elaborations based on the NDMI biophysical marker. Production-wise, the positive effect of Treatment A could be distinguished even in between alternate bearing behavior; most importantly, while increasing hazelnut production, usage of Treatment A did not lead to significantly smaller and/or lighter hazelnuts, keeping the kernel/nut ratio unchanged in relation to Treatments B and C. In this regard, Treatment B showed intermediate results, confirming that while Ecklonia maxima alone is beneficial, the complex mix (Treatment A) provides a more robust support for yield stability. However, H. halys-derived damage, as well as other defects of biotic origin, was not effectively contrasted by the treatments.

Upon analyzing data belonging to two different years, we conclude that the seasonal outlook can affect the impact of biostimulants on eco-physiological parameters, while productions were proven to consistently improve, especially in plants administered with Treatment A, with little impact being exerted by specific climatic conditions. As a conclusive remark, the conjoined application of silicon and algal extracts seemed to emerge as the most promising practice among the tested ones, and it might serve as a pivotal tool in securing stable yields and optimizing resource use in Italian hazelnut orchards, old and new alike.

Future research should continue to explore VIs to test their potential specifically for hazelnut, possibly implementing the usage of Unnamed Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to significantly increase accuracy in remote-sensing activities on small-scale orchards. Ultimately, the pursuit of new biostimulant formulations and their on-field assessment through long-term trials will represent a pivotal factor to enrich our understanding of biostimulant usage in hazelnut cultivation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C. and F.G.; methodology, V.C., F.G. and A.P.; formal analysis, F.G. and C.S.; investigation, V.C., F.G., C.S. and A.P.; data curation, F.G., A.P. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G.; writing—review and editing, V.C., F.G. and A.P.; supervision, V.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the following: (1) Agreement between Department of Agricultural and Forest Sciences (DAFNE) and Parco Scientifico e Tecnologico dell’Alto Lazio S.C. a r.l. for Ph.D. scholarship SPVA—Cycle XXXVIII (University of Tuscia), and (2) by the Italian Ministry for University and Research (MUR) for financial support (Law 232/2016, Italian University Departments of excellence) under the D.I.Ver.So. project.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank “Tenuta Longinotti—Società Agricola Vico” and its general manager Stefano Silvio Rosa for hosting the research and for technical support in field management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Map depicting the geographical collocation of the experimental site (encompassed by the white line) within the Italian peninsula.

Figure A2.

Electrical conductivity (EC) of the experimental site, expressed in mS m−1. Values refer to the 0–30 cm layer. Left polygon: Treatment A; center polygon: Treatment B; right polygon: Treatment C. Data acquired on 16 May 2025.

Figure A3.

Climograph representing monthly accumulated rainfall and average temperatures (°C) for (a) Y1 and (b) Y2.

Figure A4.

Parcels’ layout. Red: Treatment A; yellow: Treatment B; blue: Treatment C.

Figure A5.

Multispectral elaborations for (a) NDVI, (b) NDRE and (c) NDMI depicting parcels’ status before the beginning of biostimulant treatments in Y1. Red polygon: Treatment A; yellow polygon: Treatment B; blue polygon: Treatment C (Control).

Figure A6.

Multispectral elaborations for (a) NDVI, (b) NDRE and (c) NDMI depicting parcels’ status before the beginning of biostimulant treatments in Y2. Red polygon: Treatment A; yellow polygon: Treatment B; blue polygon: Treatment C (Control).

References

- Pacchiarelli, A.; Priori, S.; Chiti, T.; Silvestri, C.; Cristofori, V. Carbon Sequestration of Hazelnut Orchards in Central Italy. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 333, 107955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). Superfici e Produzione—Dati in Complesso. Available online: https://esploradati.istat.it/databrowser/#/it/dw (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Correia, P.M.R. Hazelnut: A Valuable Resource. Int. J. Food Eng. 2020, 6, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.K.; Materia, S.; Zizzi, G.; Costa-Saura, J.M.; Trabucco, A.; Evans, J.; Bregaglio, S. Climate Change Impacts on Phenology and Yield of Hazelnut in Australia. Agric. Syst. 2021, 186, 102982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, A. AI-Enhanced Projections of Hazelnut Production Under Climate Change: A Regional Analysis from Turkey. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2025, 67, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, C.; Bacchetta, L.; Bellincontro, A.; Cristofori, V. Advances in Cultivar Choice, Hazelnut Orchard Management, and Nut Storage to Enhance Product Quality and Safety: An Overview. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagetti, E.; Pancino, B.; Martella, A.; Porta, I.M.L.; Cicatiello, C.; Gregorio, T.D.; Franco, S.; Biagetti, E.; Pancino, B.; Martella, A.; et al. Is Hazelnut Farming Sustainable? An Analysis in the Specialized Production Area of Viterbo. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 Laying Down Rules on the Making Available on the Market of EU Fertilising Products and Amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003 (Text with EEA Relevance). 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/oj/eng (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in Plant Science: A Global Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Basile, B. Rate and Timing of Application of Biostimulant Substances to Enhance Fruit Tree Tolerance toward Environmental Stresses and Fruit Quality. Agronomy 2022, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, B.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Soppelsa, S.; Andreotti, C. Appraisal of Emerging Crop Management Opportunities in Fruit Trees, Grapevines and Berry Crops Facilitated by the Application of Biostimulants. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 267, 109330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabo, S.; Morais, M.C.; Aires, A.; Carvalho, R.; Pascual-Seva, N.; Silva, A.P.; Gonçalves, B. Kaolin and Seaweed-Based Extracts Can Be Used as Middle and Long-Term Strategy to Mitigate Negative Effects of Climate Change in Physiological Performance of Hazelnut Tree. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2020, 206, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovira, M.; Romero, A.; Del Castillo, N. Efficacy of Manvert Foliplus (Complete Biostimulant) in Two Hazelnut Cultivars in Tarragona, Spain. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1226, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Hernández, T.; Padilla-Contreras, D.; Godoy, K.; Cayunao, B.; Manterola-Barroso, C.; Alarcón, D.; Biško, A.; Meriño-Gergichevich, C. Diatomaceous Earth as Silicon Source Involved on Antioxidant, Morphology and Productive Traits of Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 3002–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, P.; Anastasia, F.; Massa, N.; Todeschini, V.; Cassino, C.; Gamalero, E.; Novello, G.; Lingua, G. Sustainable Hazelnut Production: Improving Yield and Quality with Microbial Inoculant. Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2025, 159, 1390–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoalino, L.A.; Reis, F.S.; Barros, L.; Rodrigues, M.Â.; Correia, C.M.; Vieira, A.L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Pascoalino, L.A.; Reis, F.S.; et al. Effect of Plant Biostimulants on Nutritional and Chemical Profiles of Almond and Hazelnut. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Dao, P.D.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Shang, J. Recent Advances of Hyperspectral Imaging Technology and Applications in Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra, J.; Buchaillot, M.L.; Araus, J.L.; Kefauver, S.C. Remote Sensing for Precision Agriculture: Sentinel-2 Improved Features and Applications. Agronomy 2020, 10, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.L.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; López-Herrera, P.J.; Pérez-Martín, E.; Alonso-Ayuso, M.; Quemada, M. Airborne and Ground Level Sensors for Monitoring Nitrogen Status in a Maize Crop. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 160, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.M.; Goodwin, I.; Cornwall, D. Remote Sensing Using Canopy and Leaf Reflectance for Estimating Nitrogen Status in Red-Blush Pears. HortScience 2018, 53, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, G.; Messina, G.; De Luca, G.; Fiozzo, V.; Praticò, S. Monitoring the Vegetation Vigor in Heterogeneous Citrus and Olive Orchards. A Multiscale Object-Based Approach to Extract Trees’ Crowns from UAV Multispectral Imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 175, 105500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla-Albornoz, M.; Miarnau, X.; Pamies-Sans, M.; Bellvert, J. Almond Yield Prediction at Orchard Scale Using Satellite-Derived Biophysical Traits and Crop Evapotranspiration Combined with Machine Learning. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1667674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.; Pádua, L.; Paredes, P.; Rebollo, F.J.; Moral, F.J.; Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Crespo, N.; Pádua, L.; Paredes, P.; et al. Spatial–Temporal Dynamics of Vegetation Indices in Response to Drought Across Two Traditional Olive Orchard Regions in the Iberian Peninsula. Sensors 2025, 25, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, G.; Maffia, A.; Pastore, V.; Amato, M.; Celano, G.; Altieri, G.; Maffia, A.; Pastore, V.; Amato, M.; Celano, G. Use of High-Resolution Multispectral UAVs to Calculate Projected Ground Area in Corylus avellana L. Tree Orchard. Sensors 2022, 22, 7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morisio, M.; Noris, E.; Pagliarani, C.; Pavone, S.; Moine, A.; Doumet, J.; Ardito, L.; Morisio, M.; Noris, E.; Pagliarani, C.; et al. Characterization of Hazelnut Trees in Open Field Through High-Resolution UAV-Based Imagery and Vegetation Indices. Sensors 2025, 25, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghavi, T.; Rahemi, A.; Suarez, E. Development of a Uniform Phenology Scale (BBCH) in Hazelnuts. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 296, 110837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strashok, O.; Ziemiańska, M.; Strashok, V. Evaluation and Correlation of Normalized Vegetation Index and Moisture Index in Kyiv (2017–2021). J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Tang, W.; Gao, D.; Zhao, R.; An, L.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Song, D. UAV-Based Chlorophyll Content Estimation by Evaluating Vegetation Index Responses under Different Crop Coverages. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varouchakis, E.A.; Komnitsas, K.; Galetakis, M. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Vegetation Health and Moisture Dynamics in Rehabilitated Mining Quarries Using Satellite Imagery. Environ. Process. 2025, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.; Fischer, J.; Kuhn, M.; Pasotti, A.; Rouzaud, D.; Bruy, A.; Sutton, T.; Dobias, M.; Pellerin, M.; Rouault, E.; et al. qgis/QGIS: Ver. 3.42.3. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15437799 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Spinelli, F.; Fiori, G.; Noferini, M.; Sprocatti, M.; Costa, G. Perspectives on the Use of a Seaweed Extract to Moderate the Negative Effects of Alternate Bearing in Apple Trees. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battacharyya, D.; Babgohari, M.Z.; Rathor, P.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed Extracts as Biostimulants in Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, R.; Cocetta, G.; Trivellini, A.; Vernieri, P.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulants and Crop Responses: A Review. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2015, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannin, L.; Arkoun, M.; Etienne, P.; Laîné, P.; Goux, D.; Garnica, M.; Fuentes, M.; Francisco, S.S.; Baigorri, R.; Cruz, F.; et al. Brassica Napus Growth Is Promoted by Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. Seaweed Extract: Microarray Analysis and Physiological Characterization of N, C, and S Metabolisms. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvas, D.; Ntatsi, G. Biostimulant Activity of Silicon in Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Rasheed, Y.; Asif, K.; Ashraf, H.; Maqsood, M.F.; Shahbaz, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Sardar, R.; Haider, F.U. Plant Biostimulants: Mechanisms and Applications for Enhancing Plant Resilience to Abiotic Stresses. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 6641–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartelat, A.; Cerovic, Z.G.; Goulas, Y.; Meyer, S.; Lelarge, C.; Prioul, J.-L.; Barbottin, A.; Jeuffroy, M.-H.; Gate, P.; Agati, G.; et al. Optically Assessed Contents of Leaf Polyphenolics and Chlorophyll as Indicators of Nitrogen Deficiency in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Field Crop. Res. 2005, 91, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, F.; Silvestri, C.; Cristofori, V.; Giovanelli, F.; Silvestri, C.; Cristofori, V. Effect of Biostimulant Applications on Eco-Physiological Traits, Yield, and Fruit Quality of Two Raspberry Cultivars. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wylie, B.K.; Howard, D.M.; Phuyal, K.P.; Ji, L. NDVI Saturation Adjustment: A New Approach for Improving Cropland Performance Estimates in the Greater Platte River Basin, USA. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Tian, J.; Philpot, W.; Tian, Q.; Feng, H.; Fu, Y. VNAI-NDVI-Space and Polar Coordinate Method for Assessing Crop Leaf Chlorophyll Content and Fractional Cover. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.; Andriolo, U.; Paiva, L.; Premebida, C.; Ferraz, A. Modelling the Dependence of Chlorophyll Leaf-Clip Measures on Vegetation Indices Derived from Multispectral UAS Images in Vineyards Parcels. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023—2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 2775–2778. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Fu, Z.; Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J.; et al. Evaluation of Three Portable Optical Sensors for Non-Destructive Diagnosis of Nitrogen Status in Winter Wheat. Sensors 2021, 21, 5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, P.; Flasse, S.; Tarantola, S.; Jacquemoud, S.; Grégoire, J.-M. Detecting Vegetation Leaf Water Content Using Reflectance in the Optical Domain. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 77, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanguri, R.; Laneve, G.; Hościło, A. Mapping Forest Tree Species and Its Biodiversity Using EnMAP Hyperspectral Data along with Sentinel-2 Temporal Data: An Approach of Tree Species Classification and Diversity Indices. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Kapoor, D. Fascinating Regulatory Mechanism of Silicon for Alleviating Drought Stress in Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frary, A.; Öztürk, S.C.; Balık, H.I.; Balık, S.K.; Kızılcı, G.; Doğanlar, S.; Frary, A. Association Mapping of Agro-Morphological Traits in European Hazelnut (Corylus avellana). Euphytica 2019, 215, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellena, M.; González, A.; Romero, I. Effect of Seaweed Extracts (Ascophyllum nodosum) on Yield and Nut Quality in Hazelnut. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1379, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofori, V.; Ferramondo, S.; Bertazza, G.; Bignami, C. Nut and Kernel Traits and Chemical Composition of Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) Cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonia, F.; Battaglia, V.; Righi, L.; Pascali, G.; La Torre, A. Plant Biostimulant Regulatory Framework: Prospects in Europe and Current Situation at International Level. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, L.; Moraglio, S.T.; Tavella, L. Halyomorpha Halys, a Serious Threat for Hazelnut in Newly Invaded Areas. J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, O.L.; Keeping, M.G.; Meyer, J.H. Silicon-Augmented Resistance of Plants to Herbivorous Insects: A Review. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2009, 155, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.