Abstract

Microalgal amendments can improve soil structure by regulating extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs). However, the mechanisms underlying this process in red soils (characterized by high clay content and susceptibility to acidification) under different farming practices remain unclear. This study examined how Chlorella vulgaris (C. vulgaris) amendment influences EPS composition to enhance soil aggregate stability under arable land and rice paddy farming. A five-month pot experiment using a completely randomized design was conducted to investigate the effects of Chlorella vulgaris amendment on soils cultivated with Pennisetum × sinese and rice, two economically important crops commonly grown in South China. At the end of the experiment, Chlorella vulgaris amendment substantially increased both the mean weight diameter (MWD) and geometric mean diameter (GMD) of soil aggregates under both farming systems. Excitation–emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy revealed distinct changes in soil EPS components between the two farming types. Under arable land farming, humic-like and protein-like EPSs were dominant in Chlorella vulgaris-amended treatments, with fluorescence intensities more than doubling compared to the control. Conversely, under rice paddy farming, soil fulvic acid was the main component and showed a moderate increase. Partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) demonstrated that protein-like and humic-like EPSs had the strongest direct effects on aggregate stability in arable land red soil, while fulvic acid was the key factor in rice paddy red soil. The present study demonstrates that Chlorella vulgaris amendment improves aggregate stability in red soils through farming-specific, EPS-mediated pathways, providing a quantitative framework for researchers and land managers seeking to apply microalgal amendments for red soil enhancement and sustainable land management.

1. Introduction

Red soil is one of the world’s three major soil types, covering 13% of the world’s land area and widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions with semi-humid or arid climates [1]. This soil type is characterized by high clay content, rapid decomposition of organic matter, susceptibility to acidification, and poor structural stability [2]. Intense rainfall and inappropriate farming practices readily disrupt soil aggregates in these regions, leading to compaction, fertility decline, and severe degradation [3]. These challenges underscore the need for effective biological methods to enhance red soil aggregate stability.

Microbial extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) offer a promising alternative to conventional soil amendments [4]. Traditional approaches using inorganic and organic fertilizers can improve aggregate stability [5,6], but may cause toxic substance accumulation and accelerate soil acidification [7]. In contrast, EPSs secreted by soil microbes function as “transient binding agents” that adhere to mineral surfaces and promote organic-mineral complex formation. For example, Wang et al. demonstrated that soils inoculated with EPS-producing microorganisms contained 71.31% more macroaggregates than control soils [8], highlighting the potential of microbial biotechnologies for sustainable soil improvement.

Among microbial amendments, microalgae—particularly Chlorella vulgaris—have emerged as effective agents for improving soil aggregate stability through EPS production [9,10,11]. Research demonstrates that microalgal inoculation can significantly increase macroaggregate proportions and mean weight diameter [12], with EPS-mediated increases in fulvic acid and water-soluble organic carbon content being key mechanisms [13].

Critically, EPS composition and function vary with environmental conditions. Under drought stress, microalgae produce structurally simpler, lower-molecular-weight EPSs, whereas flooded conditions favor more complex polysaccharides [14]. Similarly, aerobic environments yield protein-rich EPSs, while anaerobic conditions promote humic-rich EPSs with stronger adhesive and metal-binding properties [15]. These findings have direct implications for agricultural systems: the contrasting microenvironments of arable land (aerobic, non-flooded) and rice paddies (anaerobic, flooded) likely elicit fundamentally different EPS profiles from inoculated microalgae [16]. However, no study has systematically examined how these farming system differences affect microalgal EPS production and, consequently, soil aggregate stability in red soils.

To characterize these environment-dependent changes in EPSs, we employed excitation–emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy coupled with parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC). This technique enables efficient semi-quantitative analysis of key EPS components, including proteins, humic acids, and fulvic acids [17,18,19]. Previous studies using EEM-PARAFAC have demonstrated compositional specificity of EPSs under different conditions, with protein-like components dominating aerobic environments and humic-like components enhanced under anaerobic conditions [20]. This approach provides an ideal framework for investigating how the distinct environments of arable and paddy farming systems differentially shape EPS composition following C. vulgaris amendment.

This study investigates how Chlorella vulgaris amendment affects soil aggregate stability under arable and paddy farming systems, with a focus on farming-induced changes in EPS composition as the underlying mechanism. We hypothesize that the aerobic environment of arable soil and the anaerobic, flooded environment of paddy soil will induce distinct EPS profiles—differing in quantity and biochemical composition—that differentially regulate aggregate stability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. Study Site and Soil Collection

The soil used in the Chlorella vulgaris addition experiment was collected in September 2023 from Zengcheng District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province. The region is situated in a subtropical zone with an average elevation of 21.3 m. Zengcheng District experiences a typical subtropical humid climate, with annual average temperatures ranging from 21 to 22 °C and yearly rainfall exceeding 1500 mm. During soil formation, leaching was significant, leading to considerable loss of soluble components like carbonates and silicates, and the residual accumulation of iron and aluminum oxides. Undisturbed topsoil (0–20 cm depth) was collected from an uncultivated field using a stainless-steel spade. Multiple sampling points were selected across the field following an S-shaped pattern to ensure representativeness. Plant residues and visible roots were carefully removed, and the soil was transported to the laboratory in sealed polyethylene bags. After air-drying at room temperature for seven days, the soil was gently crushed and passed through a 5 mm sieve to remove stones and coarse debris while preserving the natural aggregate structure. The processed soil was then homogenized and stored in a cool, dry place until use. Initial soil physicochemical properties are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initial soil physicochemical properties.

2.1.2. Chlorella vulgaris Inoculum Preparation

Chlorella vulgaris (C. vulgaris) was cultured in TAP-2 (Table S1) medium under sterile conditions at 25 °C with a 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle and light intensity of 50–200 μmol·m−2·s−1 (pH 6.8–7.0) for 14 days, yielding a cell suspension at 1 × 108 cells/mL of C. vulgaris biomass composition (proteins ~50%, carbohydrates ~20%).

2.1.3. Pot Experiment Setup

A five-month pot experiment (March–July 2024) was conducted at the greenhouse of the Institute of Eco-environmental and Soil Sciences, Guangdong Academy of Sciences (113.355695° E, 23.181472° N) using a completely randomized design with two farming systems. For the arable land system, Pennisetum × sinese was grown in 15 L pots containing 10 kg red soil and maintained at field capacity, while for the rice paddy system, rice was grown in 10 L pots containing 5 kg red soil under continuous flooding. Each system included five treatments with four replicates, and all pots received farmyard manure as basal fertilizer.

2.1.4. Chlorella vulgaris Inoculation Treatments

Each farming system included five treatments with four replicates: (1) CK—blank control; (2) ZL—heat-inactivated C. vulgaris suspension (70 °C, 20 mL); (3) Z5—5 mL C. vulgaris suspension; (4) Z10—10 mL C. vulgaris suspension; (5) Z20—20 mL C. vulgaris suspension. The suspension was inoculated weekly throughout the experiment.

The inoculation volumes were selected to establish a concentration gradient corresponding to final exogenous C. vulgaris contents of 0.012, 0.024, and 0.048 g/kg dry soil (Z5, Z10, Z20) for arable land, and 0.024, 0.048, and 0.096 g/kg for rice paddies, based on preliminary trials indicating these levels were effective for EPS-mediated aggregate improvement without causing nutrient overload.

2.2. Soil Sampling

At experiment termination, soil samples were collected using a stainless-steel soil auger. Three soil cores (0–15 cm) were randomly collected from each pot using a soil auger, with minimal disturbance to preserve soil structure. Plant roots were carefully removed with sterile tweezers, and the soil was passed through a 2 cm sieve. Each sample was divided into three subsamples: one fresh portion was immediately stored at 4 °C for microbial and EPS analyses, while the other two were air-dried for seven days under ventilated conditions, with one used for aggregate stability measurements and the other sealed in sterile bags for subsequent physicochemical property analyses.

2.3. Soil Aggregate Stability Analysis

The wet sieving method was employed to determine soil aggregate water stability [21]. Soil aggregate stability can be quantified using three indicators: mean weight diameter (MWD), geometric mean diameter (GMD), and the percentage of aggregates > 0.25 mm (R0.25). All three indicators demonstrate a positive correlation with soil aggregation levels [22].

In these equations, represents the mean diameter of each size class (mm); indicates the proportion of aggregates in size class ; n stands for the number of sieves (g); > 0.25 represents the percentage of aggregates with sizes > 0.25 mm (%); and denotes the total weight of all aggregate fractions (g) [23].

2.4. Soil Chemical and Biological Properties Analyses

All soil basic properties were measured using standard methods, with three replicates. Soil pH was determined using a calibrated pH meter (PHS-3C, INESA Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with a glass electrode at a soil-to-water ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v), following equilibration for 30 min [24]. Total nitrogen (TN) was measured by digesting 0.3 g of soil with 3 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid at 380 °C for 30 min, and then analyzing with an automatic Kjeldahl nitrogen analyzer (Biobase Biodustry Co., Ltd., Jinan, Shandong, China) [25]. Total phosphorus (TP) was assessed using the Mo-Sb colorimetric method [26]. Soil organic matter was determined by colorimetry [27]. Available potassium (AK) was extracted from soil samples using 1.0 mol/L ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) (Unilong Industry Co., Ltd., Jinan, Shandong, China) at pH 7.0, following standard procedures. The extracted potassium concentration was determined by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AA-7000 Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) [24]. Total potassium (TK) was determined after digestion of soil samples using a mixed acid system (HF–HClO4) (HF, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; HClO4, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The potassium concentration in the digest was measured by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry [24]. Available phosphorus (AP) was extracted with 0.5 mol/L NaHCO3 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) (pH = 8.5) and determined using the Olsen method [28]. Microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) in fresh soil samples were determined by the chloroform fumigation–extraction method [29].

2.5. Determination of Soil EPSs

Soil EPS was extracted using the cation exchange resin (CER) (Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) method [30]. The procedure involves mixing 3 g of soil with 25 mL CaCl2 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). solution (0.01 M) and adjusting the pH to 7 with 0.1 M Ca(OH)2 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), shaken at 120 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, and centrifuged at 3200× g for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was then resuspended in 25 mL PBS buffer (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with 5 g pre-washed CER and extracted for 2 h at 200 rpm. After centrifugation at 4200× g for 30 min, the supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm membrane) to obtain the EPS extract.

2.6. Excitation–Emission Matrix and Parallel Factor Analysis

Fluorescence spectroscopy measurements were performed at room temperature using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-7100, Hitachi, Hitachi City, Japan). Excitation–emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectra were collected over an excitation wavelength range of 220 to 450 nm (with 5 nm steps) and an emission wavelength range of 250 to 600 nm (with 1 nm steps). Scan parameters included excitation and emission slit widths of 5 nm, a scan speed of 2400 nm/min, and a voltage of 600 V [18]. Following the inter-laboratory standardized method proposed by Murphy, EEM data for the samples were corrected using the corresponding background treatments as blanks [31]. All blank-subtracted EEM data were further processed using the “staRdom” package in R software (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) to perform inner filter effect correction, Raman normalization, scatter removal, and dilution correction [32].

2.7. Data Statistical Analysis

Soil chemical properties (OC; TN; TP and AP; TK and AK), microbial activity indicators (microbial biomass nitrogen, microbial biomass carbon), soil acidity/alkalinity (pH), aggregate stability indicators (MWD, GMD, R0.25), and fluorescence intensity of soil EPS components’ excitation–emission spectra are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test was used for statistical analysis. When parameters did not meet the assumptions for two-way ANOVA, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc multiple comparisons was used. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed on all soil physicochemical properties and EPS fluorescence intensities across the two cultivation farming systems to determine interactive effects between the cultivation modes. Spearman’s correlation analysis and partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) were employed to assess relationships among parameters, including soil fertility indicators (organic matter content; total nitrogen and available nitrogen; total potassium and available potassium; total phosphorus and available phosphorus), microbial activity indicators (microbial biomass nitrogen, microbial biomass carbon), soil acidity/alkalinity (pH), aggregate stability indicators (MWD, GMD, R0.25), and fluorescence intensities of various EPS components.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties

Soil physicochemical properties differed significantly among treatments (Table 2). Across both farming systems, OM, TN, TP, AP, AK, and pH increased significantly with higher C. vulgaris addition rates (p < 0.05). In arable land, OM under Z20 was 46.30% higher than CK (p < 0.001), while in rice paddies, Z20 increased OM by 33.11% compared to CK (p = 0.03). Soil pH under Z20 was significantly higher than CK in both arable land (p < 0.001) and rice paddies (p = 0.005). No significant differences were observed between ZL and CK for any measured property (p > 0.05). Active C. vulgaris addition dose-dependently increased soil nutrient content and pH, whereas heat-inactivated treatment (ZL) had no significant effect.

Table 2.

Effects of C. vulgaris treatments on soil physicochemical properties in arable land and rice paddy farming.

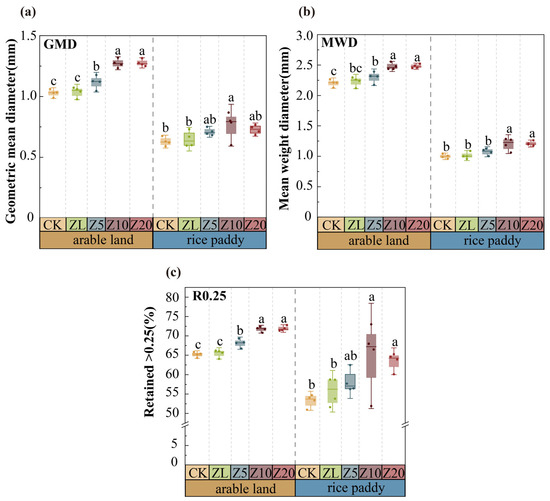

3.2. Soil Aggregate Stability

MWD, GMD, and R0.25 increased with higher C. vulgaris addition rates (Figure 1). In arable land, active C. vulgaris treatments significantly improved all three indices compared to CK (p < 0.05), with Z10 showing the highest values (p < 0.001). ZL showed no significant effect on GMD or R0.25 compared to CK (p > 0.05). In rice paddies, Z20 significantly increased MWD (p < 0.001) and R0.25 (p = 0.007). Active C. vulgaris addition significantly enhanced aggregate stability indices and increased macroaggregate proportions in both farming systems, with no significant effect from heat-inactivated treatment.

Figure 1.

Soil aggregate stability of different C. vulgaris treatment in arable land and rice paddy farming. Note: (a) GMD; (b) MWD; (c) R0.25. Error bars indicate standard error. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different C. vulgaris treatment gradients at the p < 0.05 level for the same cultivation farming. Refer to Table 2 for the abbreviation.

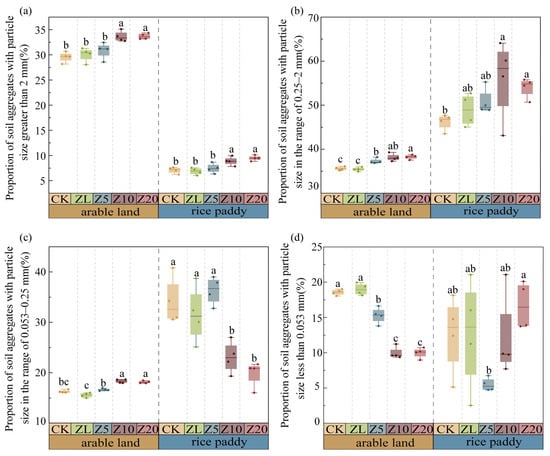

C. vulgaris addition increased macroaggregate proportions in both systems (Figure 2). In arable land, Z10 and Z20 increased the >2 mm fraction by 13.80% and 13.90% compared to CK, respectively (p < 0.001). In rice paddies, Z20 increased this fraction by 33.62% (p < 0.001). The relative increase in >2 mm aggregates was greater in rice paddies (62.83%) than in arable land (21.95%).

Figure 2.

Percentages of the <0.053, 0.053–0.25, 0.25–2.0 and >2.0 mm soil aggregate fractions under different C. vulgaris treatments in arable land and rice paddy farming. Note: (a–d) represent the proportions of soil aggregates with particle sizes greater than 2 mm, 0.25–2 mm, 0.053–0.25 mm, and less than 0.053 mm, respectively. Error bars indicate standard error. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different C. vulgaris treatment gradients at the p < 0.05 level for the same cultivation farming. Refer to Table 2 for the abbreviation.

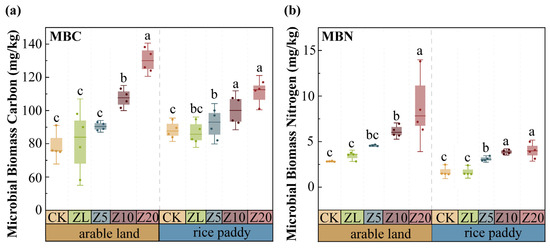

3.3. Soil Microbial Biomass

MBC and MBN increased with higher C. vulgaris addition rates in both farming systems (Figure 3). In arable land, Z20 increased MBC by 64.67% and MBN by 215.90% compared to CK (p < 0.001). In rice paddies, Z20 increased MBC by 25.53% and MBN by 134.50% compared to CK (p < 0.001). The effects were more pronounced in arable land than in rice paddies. ZL showed no significant effect on either parameter (p > 0.05). Active C. vulgaris addition substantially increased soil microbial biomass, with more pronounced effects in arable land than in rice paddies.

Figure 3.

Differences in soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen under different C. vulgaris treatments in arable land and rice paddy farming. Note: (a) microbial biomass carbon; (b) microbial biomass nitrogen. Error bars indicate standard error. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different C. vulgaris treatment gradients at the p < 0.05 level for the same cultivation farming. Refer to Table 2 for the abbreviation.

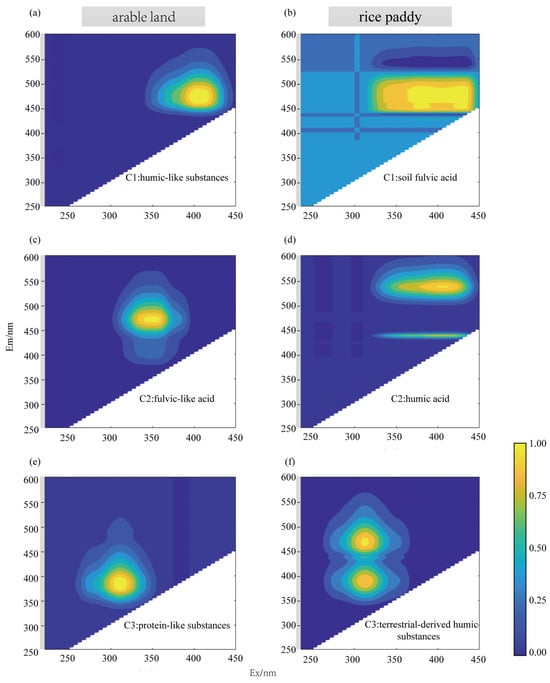

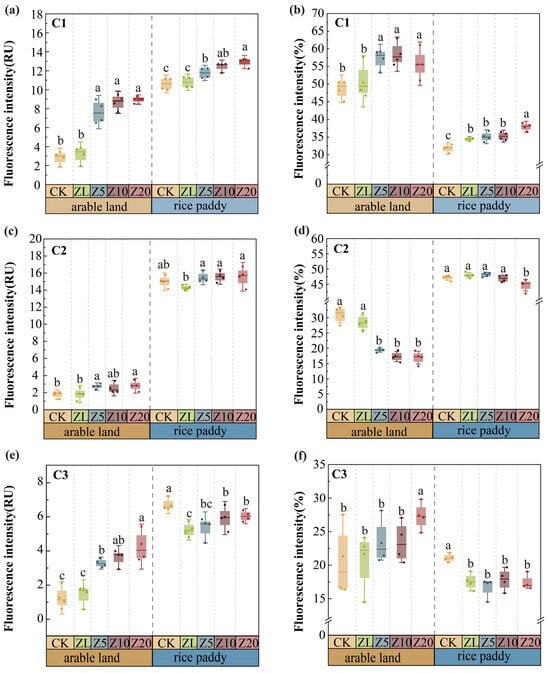

3.4. PARAFAC Component Analysis of EEM Fluorescence Spectra

PARAFAC analysis identified three distinct EPS fluorescence components in each farming system (Figure 4): Rice paddies: C1 = soil fulvic acid; C2 = humic acid; C3 = terrestrial-derived humic substances. Arable land: C1 = humic-like substances; C2 = fulvic-like acid; C3 = protein-like substances.

Figure 4.

Contour plots of the three components identified using the EEM-PARAFAC in different C. vulgaris treatments. Note: contour plots of three components were identified by the EEM-PARAFAC method for arable land soil (a,c,e) and rice paddy soil (b,d,f). The fluorescent components were identified as follows: for the arable farming: fulvic-like acid (component 2), protein-like substances (component 3), and humic-like substances (component 1); for the paddy farming: terrestrial-derived humic substances (component 3), humic acid (component 2), and soil fulvic acid (component 1).

In arable land, C. vulgaris addition significantly increased the fluorescence intensity of all three components, with Z20 showing the strongest effects (p < 0.05; Figure 5). The relative proportions of C1 and C3 increased with higher addition rates, while C2’s proportion decreased. C1’s proportion peaked under Z10 (p = 0.002), and C3 reached its highest proportion under Z20 (p = 0.021). In rice paddies, C. vulgaris addition significantly increased C1 fluorescence intensity and its relative proportion, reaching peak values under Z20 (p < 0.001). In contrast, C2 and C3’s proportions decreased (p < 0.05). C. vulgaris addition altered EPS composition differently between farming systems—increasing humic-like and protein-like components in arable land, but primarily fulvic acid in rice paddies.

Figure 5.

The intensity and percentage of fluorescence components in different C. vulgaris treatments in arable land and rice paddy farming. Note: Panels (a,c,e) show the fluorescence intensity, while panels (b,d,f) represent the relative percentage of the fluorescence components. Error bars indicate standard error. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different C. vulgaris treatment gradients at the p < 0.05 level for the same cultivation farming. Refer to Table 2 for the abbreviation.

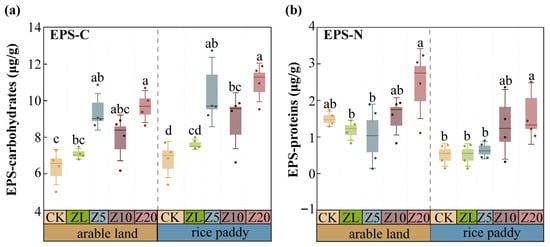

3.5. Soil EPS Content Analysis

EPS-C and EPS-N content increased with higher C. vulgaris addition rates in both farming systems (Figure 6). In arable land, Z20 increased EPS-C by 63.64% and EPS-N by 64.00% compared to CK (p < 0.001). In rice paddies, Z5, Z10, and Z20 increased EPS-C by 48.65%, 25.76%, and 53.26%, respectively (p < 0.05). Notably, ZL also increased EPS-C by 22.06% in arable land and 17.97% in rice paddies compared to CK, but showed no significant effect on EPS-N. Active C. vulgaris addition increased both EPS-C and EPS-N content, whereas heat-inactivated treatment increased only EPS-C, indicating that viable algal cells are required for EPS-N accumulation.

Figure 6.

Mass fractions of soil EPS-carbohydrates and EPS-proteins under different C. vulgaris treatment rates in arable land and rice paddy farming. Note: (a) extracellular polymeric substances—carbohydrates; (b) extracellular polymeric substances—proteins. Error bars indicate standard error. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different C. vulgaris treatment gradients at the p < 0.05 level for the same cultivation farming. Refer to Table 2 for the abbreviation.

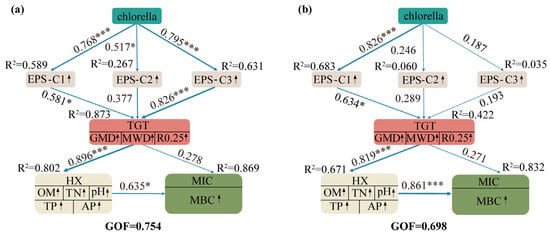

3.6. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) of Soil Parameters

PLS-PM analysis revealed significant pathways linking C. vulgaris addition to aggregate stability (TGT) via EPS components (Figure 7). In arable land (GoF = 0.754), the path coefficients from EPS components to TGT were highest for C3 (protein-like, 0.826) and C1 (humic-like, 0.581), followed by C2 (fulvic-like, 0.377). TGT showed strong positive correlations with soil chemical properties (HX, 0.896) and microbial biomass (MIC, 0.278). In rice paddies (GoF = 0.698), C1 (fulvic acid, 0.634) showed the highest path coefficient to TGT, followed by C2 (humic acid, 0.289). PLS-PM identified protein-like and humic-like EPSs as the strongest predictors of aggregate stability in arable land, while fulvic acid was the primary predictor in rice paddies.

Figure 7.

Results of PLS-PM models analyzing C. vulgaris effects on soil aggregates and biochemistry under different cultivation farming. Note: (a) causal relationships between C. vulgaris treatment, soil EPS components, soil aggregate stability (TGT), soil chemical properties (HX), and soil microbial viability (MIC) in the arable farming. Larger path coefficients are represented by wider arrows, with blue indicating positive effects, respectively. The goodness-of-fit (GoF) value for the arable farming model is 0.754. (b) Causal relationships between C. vulgaris treatment, soil EPS components, soil aggregate stability (TGT), soil chemical properties (HX), and soil microbial viability (MIC) in paddy farming. Larger path coefficients are represented by wider arrows, with blue indicating positive effects, respectively. The goodness-of-fit (GoF) value for the paddy farming model is 0.698. *, and *** indicate significance at p < 0.05, and p < 0.001, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Chlorella vulgaris Treatment Enhances Aggregate Stability via Specific EPS Components

We hypothesized that the contrasting aerobic (arable) and anaerobic (paddy) soil environments would induce distinct EPS profiles following C. vulgaris addition, with these differences driving the observed effects on aggregate stability. Our results support this hypothesis: EEM-PARAFAC analysis revealed that C. vulgaris addition was associated with increased protein-like and humic-like EPS components in arable soils, whereas fulvic acid dominated the EPS response in paddy soils.

The present study showed that applying active C. vulgaris was associated with increased EPS production, which improved the water stability of soil aggregates. These results were consistent with some previous studies [33]. For example, Rossi et al. [34] found that EPSs in biological soil crusts enhance hydraulic conductivity by improving pore connectivity, allowing for faster drainage, reduce fluctuations in soil matric potential, and prevent mechanical disruption of aggregate structures caused by swelling clay minerals, thereby boosting aggregate stability. Removal of EPSs leads to a decrease in hydraulic conductivity by a factor of 1.7 to 4.7.

While most previous studies considered overall EPS effects, our study distinguished the functional contributions from specific EPS components. Both EPS-protein-like and EPS-humic-like substances in arable land increased significantly with higher C. vulgaris treatment rates and showed a positive correlation with soil aggregate stability indicators. These findings suggest that C. vulgaris addition was associated with these two EPS components. While soil proteins form “micelle” structures via organic–mineral interactions, binding surrounding mineral particles through various chemical bonds, thereby improving soil aggregation [35], humic substances in clay-rich soils can adsorb onto Al-OH and Si-OH groups on clay surfaces to form water-stable aggregates [36]. Therefore, our findings suggest that C. vulgaris treatment in arable land farming enhances soil aggregate stability primarily by increasing specific EPS components, namely protein-like and humic-like substances.

In contrast, EPS-fulvic acid in rice paddies increased significantly with higher C. vulgaris treatment rates and showed positive correlations with aggregate stability indicators. This suggests that in paddy environments, the C. vulgaris-mediated soil EPS-fulvic acid pathway enhances soil aggregate stability. Fulvic acid plays a crucial role in the formation and stabilization of macroaggregates [37], readily bonds with iron oxides to form a monomolecular layer that encases soil particle–iron oxide complexes, thereby improving aggregate water stability [38].

4.2. Divergent Mechanisms of Chlorella vulgaris-Induced Aggregate Stabilization in Arable Land and Rice Paddy Farming

EEM-PARAFAC analysis revealed distinct EPS compositions between arable land and rice paddy farming. Compared to the control group, the increase in MWD in rice paddies was 8.5% higher than in arable land, while that in R0.25 was 3.48% higher. Thus, C. vulgaris showed greater ecological efficiency in paddy soils. Currently, there is limited research on the differences in C. vulgaris treatment efficiency between these two farming methods, indicating the need for further investigation. Further analyses suggested EPS components differed between the two farming types.

The differences likely result from variations in dominant microbial populations and biofilm systems [39], and different environmental stress on microbial metabolism [40] under different cultivation practices. Active C. vulgaris provides the environmental foundation for soil microorganisms to cope with water stress [41]. In response, the microorganisms secrete large amounts of humic-like and protein-like substances, consistent with Flemming et al.’s [42] hypothesis of “drought stress-induced EPS synthesis. The protein and humic components of EPSs collectively promote the formation and stability of aggregates. The stability of these aggregates further enhances the soil’s water retention capacity. In arable land, EPSs promote aggregate development through electrostatic attraction of protein-like substances and hydrogen bond coupling with soil minerals [43] while simultaneously working with humic substances to bind soil particles [44].

In a rice paddy, the enhancement in soil aggregate water stability is mainly due to the key role of EPS-fulvic acid and the improved metabolic activity supported by aquatic conditions. The anaerobic conditions in surface soil limit microbial oxidative metabolism, resulting in EPSs dominated by hydrophilic fulvic acid, which forms stable organic–mineral complexes through complexation with Fe3+/Al3+ [45]. That is, EPSs exhibit specificity under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of Fu et al. [15], who demonstrated that under aerobic conditions, the adhesiveness of EPSs secreted by cyanobacteria primarily derives from proteinaceous components, such as tryptophan and tyrosine. In contrast, under anaerobic conditions, some components of EPSs are transformed into humic substances, which enhance the adhesiveness of EPSs through higher chemical reactivity [46]. The presence of oxygen decreases the stability of certain functional groups within the EPSs, thereby weakening its chelation with Fe ions [47].

4.3. Synergistic Microbial-Chemical Coupling Effects on Aggregate Stability

The PLS-PM model showed that in arable land, EPS components were positively correlated with aggregate stability through both direct effects and indirect effects by promoting MBC. Specifically, as an important soil “binding agent,” MBC directly participates in regulating the impact of organic carbon on MWD [48]. At the same time, elevated MBC signals more active soil microbial growth and metabolism [49]. It is noteworthy that soil microorganisms are essential for aggregate stability. Fungi stabilize soil by entangling particles and secreting substances that help particles stick together, while bacteria mainly depend on EPS secretion to encase microaggregates and enhance cohesion among mineral particles [50]. Soil microorganisms constantly produce EPSs, creating a positive feedback loop within the “algae–microbe–soil” system, which aligns with the “organic amendment–microbe–EPS” synergistic model [39]. The treatment partially reduced microbial stress caused by soil acidification, consistent with Deka’s [51] findings on EPS buffering low pH stress in soil, which highlights that our study further quantified the link between pH improvement and changes in EPS components. Negatively charged functional groups in EPSs, such as carboxyl groups, help reduce soil acidification and create a better microbial environment in the soil. This greatly boosts the role of microbial biofilms in maintaining soil aggregate stability.

In rice paddy conditions, both the absolute and relative content of fulvic acid in soil EPSs showed a positive correlation with C. vulgaris treatment volume. Fulvic acid typically contains O-alkyl and carboxyl groups, such as in peptides and organic acids. Alkyl groups form “hydration shells” in aqueous treatments, while carboxyl groups easily form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. These groups together increase the hydrophilicity and water solubility of fulvic acid, suggesting that fulvic acid in soil EPSs remains stable in aquatic environments [52,53]. Through experimental studies, Jiang et al. demonstrated that fulvic acid enhances glutathione metabolism in soil bacterial communities and improves soil ecological environments, significantly increasing the Shannon diversity index of soil microbes [52]. Under the influence of fulvic acid, soil microbial abundance increases, which may, in turn, raise biofilm metabolite levels and improve soil aggregate stability. This finding offers stronger support for the reliability of our results.

Overall, this study showed that C. vulgaris improved soil aggregate stability through EPS-mediated mechanisms, with different functional pathways in farming. Combining microbial viability and EPS chemistry highlights a synergistic model for enhancing soil structure.

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this pot experiment under controlled greenhouse conditions may not fully represent field-scale responses influenced by soil heterogeneity, climate variability, and long-term management history. Second, the CER extraction method preferentially recovers loosely bound EPSs; tightly bound fractions that may also contribute to aggregate stability were not characterized. Third, we did not directly distinguish C. vulgaris-derived EPSs from native microbial EPSs. The significant chlorophyll-a increase under viable C. vulgaris treatments (Figure S1) and contrasting responses between active and heat-inactivated treatments suggest living algal cells contribute to the observed effects, but relative contributions remain undetermined. Future research should employ isotope labeling or molecular markers to directly trace C. vulgaris-derived EPS contributions and conduct longer-term field trials across multiple soil types and climatic conditions to validate these findings for practical agricultural applications.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Chlorella vulgaris amendment effectively enhances soil aggregate stability in red soils through farming system-specific EPS pathways. Four key findings emerged: (1) active C. vulgaris addition significantly improved aggregate stability indices (MWD, GMD, R0.25) in both arable land and rice paddy systems, while heat-inactivated treatment showed no effect; (2) the improvement was mediated by distinct EPS components—protein-like and humic-like substances in arable land versus fulvic acid in rice paddies; (3) PLS-PM analysis confirmed EPS composition as the primary predictor of aggregate stability; and (4) C. vulgaris addition concurrently enhanced soil nutrient status and microbial biomass. These findings provide a mechanistic basis for applying microalgal amendments to improve aggregate stability in degraded red soils under different farming practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020239/s1, Figure S1: Determination of Chlorophyll Content a in Soil; Table S1: TAP-2 medium.

Author Contributions

S.H.: Writing—Review and Editing, Writing—Original Draft, Investigation. X.J.: Writing—Review and Editing, Writing—Original Draft, Investigation. H.L.: Writing—Original Draft, Investigation. H.J. (Hongtao Jiang): Writing—Original Draft, Investigation. J.C.: Writing—Original Draft, Investigation. H.J. (Heng Jiang): Writing—Review and Editing, Methodology, Formal Analysis. S.Y.: Writing—Review and Editing, Conceptualization. S.C.: Writing—Review and Editing, Project Administration, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2025A1515010758), the GDAS’ Project of Science and Technology Development (Grant Nos. 2020GDASYL-20200103084 and 2023GDASZH-2023010103), the Guangdong Foundation for Program of Science and Technology Research (Grant No. 2023B1212060044), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42201057). This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42101401), and the Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Project (Grant No. 2023A04J1517).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions and key supporting data presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biswas, B.; Chakraborty, D.; Timsina, J.; Bhowmick, U.R.; Dhara, P.K.; Ghosh Lkn, D.K.; Sarkar, A.; Mondal, M.; Adhikary, S.; Kanthal, S.; et al. Agroforestry offers multiple ecosystem services in degraded lateritic soils. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Leng, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Lin, Y.; Xiang, X.; Liu, J. Changes in fertility and microbial communities of red soil and their contribution to crop yield following long-term different fertilization. J. Soils Sediments 2025, 25, 1115–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Hussain, S.; Chen, J.; Hu, F.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Yang, M. Cover crop root-derived organic carbon influences aggregate stability through soil internal forces in a clayey red soil. Geoderma 2023, 429, 116271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Parvez, S.S.; Goswami, A.; Banik, A. Exopolysaccharides from agriculturally important microorganisms: Conferring soil nutrient status and plant health. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Gu, F.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. Assessing of the influence of organic and inorganic amendments on the physical-chemical properties of a red soil (Ultisol) quality. Catena 2019, 183, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Xu, M.G.; Shah, S.; Abrar, M.M.; Sun, N.; Wang, B.R.; Cai, Z.J.; Saeed, Q.; Naveed, M.; Mehmood, K.; et al. Soil aggregation and soil aggregate stability regulate organic carbon and nitrogen storage in a red soil of southern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Su, S.; Meng, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Bi, X. Potentially toxic trace element pollution in long-term fertilized agricultural soils in China: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-J.; Li, M.-Y.; Wang, W.-L.; Wang, S.-M.; Chen, S.-S. Effect of Single Cell and Filamentous Microorganisms on Formation of Soil Aggregates. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 52, 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Duan, H.; Dong, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S.; Xu, T.; Guo, B. Improved effects of combined application of nitrogen-fixing bacteria Azotobacter beijerinckii and microalgae Chlorella pyrenoidosa on wheat growth and saline-alkali soil quality. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Gong, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Ye, F.; et al. Physiological and transcriptomic responses of soil green alga Desmochloris sp. FACHB-3271 to salt stress. Algal Res. 2025, 88, 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, M.M.A.; Mahreni; Murni, S.W.; Setyoningrum, T.M.; Hadi, F.; Widayati, T.W.; Jaya, D.; Sulistyawati, R.R.E.; Puspitaningrum, D.A.; Dewi, R.N.; et al. Innovative strategies for utilizing microalgae as dual-purpose biofertilizers and phycoremediators in agroecosystems. Biotechnol. Rep. 2025, 45, e870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malam Issa, O.; Défarge, C.; Le Bissonnais, Y.; Marin, B.; Duval, O.; Bruand, A.; D’Acqui, L.P.; Nordenberg, S.; Annerman, M. Effects of the inoculation of cyanobacteria on the microstructure and the structural stability of a tropical soil. Plant Soil 2007, 290, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Ni, S.; Wang, J.; Cai, C. Aggregate pore structure, stability characteristics, and biochemical properties induced by different cultivation durations in the Mollisol region of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 233, 105797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnai, G.; Rossi, F.; Felde, V.J.M.N.; Colesie, C.; Büdel, B.; Peth, S.; Kaplan, A.; De Philippis, R. Development of the polysaccharidic matrix in biocrusts induced by a cyanobacterium inoculated in sand microcosms. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Xia, M.; Lai, L.; Lu, S.; Chen, S.; Liu, G. Corrosion mechanisms of EH40 steel induced by extracellular polymeric substances from Halomonas titanicae cultivated under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Corros. Sci. 2025, 246, 112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pan, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L. Interactions of metal oxide nanoparticles with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of algal aggregates in an eutrophic ecosystem. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 94, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, T.; Yu, R. A calibration model transfer method based on quadrilinear model for excitation-emission matrix fluorescence measurements on different fluorescence spectrophotometers. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 110053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, K.; Gao, C.; Wang, S.; Zhu, D.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Cai, P. Characterising soil extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) by application of spectral-chemometrics and deconstruction of the extraction process. Chem. Geol. 2023, 618, 121271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Yu, H. Characterization of extracellular polymeric substances of aerobic and anaerobic sludge using three-dimensional excitation and emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy. Water Res. 2006, 40, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Yan, P.; Dong, Y.; Shen, Y.; Guo, J.; Zeng, N.; Zhang, P. Composition and aggregation of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in hyperhaline and municipal wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, W.D.; Rosenau, R.C. Aggregate stability and size distribution. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1. Physical and Mineralogical Methods, 2nd ed.; Klute, A., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America/American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1986; pp. 425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Han, Y.; Zou, H.; Zhang, Y. Organic fertilizer enhances soil aggregate stability by altering greenhouse soil content of iron oxide and organic carbon. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, A.N.; McKyes, E.; Kimpe, C.D. Effect of tillage reduction and fertilizer on soil macro-and microaggregation. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1989, 69, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.M. Nitrogen-total. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 1085–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agro-Chemistrical Analysis, 3rd ed.; Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties; American Society of Agronomy; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1965; pp. 403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Singh, A.K.; Yang, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, W. Effect of termite mounds on soil microbial communities and microbial processes: Implications for soil carbon and nitrogen cycling. Geoderma 2023, 431, 116368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zheng, Y. Overview of microalgal extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and their applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.R.; Butler, K.D.; Spencer, R.G.; Stedmon, C.A.; Boehme, J.R.; Aiken, G.R. Measurement of dissolved organic matter fluorescence in aquatic environments: An interlaboratory comparison. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 9405–9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, M.; Wünsch, U.; Weigelhofer, G.; Murphy, K.; Hein, T.; Graeber, D. staRdom: Versatile software for analyzing spectroscopic data of dissolved organic matter in R. Water 2019, 11, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau, S.; Imran, M.; Ray, R.L. Algae: A cutting-edge solution for enhancing soil health and accelerating carbon sequestration—A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Potrafka, R.M.; Pichel, F.G.; De Philippis, R. The role of the exopolysaccharides in enhancing hydraulic conductivity of biological soil crusts. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wershaw, R.L.; Llaguno, E.C.; Leenheer, J.A. Mechanism of formation of humus coatings on mineral surfaces 3. Composition of adsorbed organic acids from compost leachate on alumina by solid-state 13C NMR. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1996, 108, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Morton, D.W.; Johnson, B.B.; Angove, M.J. Adsorption of humic and fulvic acids onto a range of adsorbents in aqueous systems, and their effect on the adsorption of other species: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 247, 116949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Sun, B.; Li, Q. Soil aggregation and aggregating agents as affected by long term contrasting management of an Anthrosol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Feng, Z. Assessing the formation and stability of paddy soil aggregate driven by organic carbon and Fe/Al oxides in rice straw cyclic utilization strategies: Insight from a six-year field trial. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Lopez, J.B.G.; van Veelen, H.P.J.; Kok, D.D.; Postma, R.; Thijssen, D.; Sechi, V.; ter Heijne, A.; Bezemer, T.M.; Buisman, C.J. Effects of different soil organic amendments (OAs) on extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2024, 121, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, N.S.N.; Abdul Hamid, N.W.; Nadarajah, K. Effects of abiotic stress on soil microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.S.; Wu, J.T. Tolerance of soil algae and cyanobacteria to drought stress. J. Phycol. 2014, 50, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Huang, Q.; Cai, P.; Rong, X.; Chen, W. Adsorption of Pseudomonas putida on clay minerals and iron oxide. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 54, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, X.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Y.; Qu, J.; Tao, Y.; Kang, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Harnessing microbial biofilms in soil ecosystems: Enhancing nutrient cycling, stress resilience, and sustainable agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Hou, E.; Guo, J.; Gilliam, F.S.; Li, J.; Tang, S.; Kuang, Y. Nitrogen addition stimulates soil aggregation and enhances carbon storage in terrestrial ecosystems of China: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2780–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Dai, X.; Dong, B.; Guo, Y.; Dai, L. Humification in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) dominates methane release and EPS reconstruction during the sludge stabilization of high-solid anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2020, 175, 115686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassler, C.S.; Norman, L.; Mancuso Nichols, C.A.; Clementson, L.A.; Robinson, C.; Schoemann, V.; Watson, R.J.; Doblin, M.A. Iron associated with exopolymeric substances is highly bioavailable to oceanic phytoplankton. Mar. Chem. 2015, 173, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y. Soil aggregation is more important than mulching and nitrogen application in regulating soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in a semiarid calcareous soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, G.; Xue, S.; Song, Z. Rhizosphere soil microbial activity under different vegetation types on the Loess Plateau, China. Geoderma 2011, 161, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sae-Tun, O.; Bodner, G.; Rosinger, C.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Mentler, A.; Keiblinger, K. Fungal biomass and microbial necromass facilitate soil carbon sequestration and aggregate stability under different soil tillage intensities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 179, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, B. Dryland cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides show protection against acid deposition damage. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 24300–24304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, R.; Lyu, J.; Qin, L.; Wang, G.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, C.; Mao, Z. Remediation of the microecological environment of heavy metal-contaminated soil with fulvic acid, improves the quality and yield of apple. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Hur, J.; Shin, H. Changes in structural characteristics of humic and fulvic acids under chlorination and their association with trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids formation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.