Abstract

This study investigates the effects of nitrogen application and sprinkler irrigation on winter wheat growth, water use efficiency (WUE), and yield formation under dry-hot wind stress. The primary aim was to understand how nitrogen levels influence canopy structure, soil water–nitrogen coupling, and yield components under varying irrigation conditions. Field experiments were conducted with different nitrogen rates (N1, N2, N3, N4, N5) and sprinkler irrigation under heat stress. Plant height, leaf area index (LAI), canopy interception, and stemflow were measured, along with soil moisture and nitrogen content in the root zone. Results indicate that moderate nitrogen application (212 kg N ha−2) optimized yield and WUE, with a significant enhancement in canopy structure and water interception. High nitrogen levels resulted in increased water consumption but decreased nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), while lower nitrogen treatments showed reduced yield stability under heat stress. The findings suggest that balanced nitrogen management, in combination with timely irrigation, is essential for improving winter wheat productivity under climate stress. This study highlights the importance of optimizing water and nitrogen inputs to achieve sustainable wheat production in regions facing increasing climate variability.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen (N) transport and utilization in wheat agroecosystems are intricately regulated by soil water availability, fertilization management, and climatic stressors, with soil moisture dynamics playing a decisive role in mediating the vertical movement of nitrate and synchronizing nitrogen uptake with crop demand. Earlier work highlighted that fertilizer nitrogen efficiency in cereals remains limited due to leaching and denitrification losses, particularly under conditions of excessive rainfall or irrigation [1], whereas controlled irrigation allows for a closer alignment of soil N supply with the physiological requirements of wheat across critical growth stages [2]. The vertical distribution of nitrate has been shown to concentrate in the 0~20 cm layer with progressive migration to deeper soil horizons after irrigation events [3], while redistribution of nitrogen from vegetative organs to developing grains is accelerated under water-deficit conditions post-anthesis [4]. Dynamic shifts in soil water storage following repeated irrigation have been observed, with rapid increases in shallow layers immediately after water application followed by depletion due to evapotranspiration and root uptake [5]. Moreover, nitrogen application rates themselves influence soil water consumption, as higher N inputs stimulate canopy development and transpiration, thereby intensifying depletion in the upper soil profile [6].

At the same time, wheat production is constrained by episodic climatic extremes, particularly hot dry wind during grain filling, which induces accelerated leaf senescence, curtailed photosynthesis, and reduced assimilate partitioning to grains, ultimately shortening the grain-filling period and lowering yields [7]. Dry hot wind stress refers to a compound climatic event characterized by high air temperature, low relative humidity, and strong wind, which frequently occurs during the late spring to early summer period in the North China Plain, coinciding with the grain-filling stage of winter wheat [8]. This stress accelerates leaf senescence, suppresses photosynthetic activity, and disrupts assimilate translocation to developing grains, thereby shortening the grain-filling duration and reducing kernel weight and final yield. Moreover, dry hot wind stress exacerbates crop water loss by increasing vapor pressure deficit, further intensifying physiological drought conditions even under irrigated systems [9]. Physiological sensitivity of spikelet fertility and kernel weight to such stress has been widely documented, with yield reductions exceeding 20% in severe years [10]. Mitigation strategies emphasize the role of irrigation systems, especially sprinkler irrigation, which can moderate canopy temperature, elevate relative humidity, and reduce vapor pressure deficit, thus buffering crops against the adverse effects of hot dry winds [8]. This microclimatic regulation by sprinkler irrigation is therefore not merely a water-supply mechanism but a tool for heat-stress alleviation, ensuring more stable reproductive development and yield formation. Physiological perspectives further highlight that improving carbohydrate metabolism and sustaining photosynthetic efficiency under heat stress are essential for maintaining grain filling [11].

Equally important is the understanding of canopy interception processes under irrigation, which represent an interface between crop physiology, water management, and nitrogen dynamics. Classic interception models demonstrated that rainfall or irrigation water retained on plant surfaces depends strongly on canopy architecture [12], and more recent studies employing UAV-based remote sensing confirm that wheat canopy morphology under sprinkler irrigation critically determines interception magnitude [13]. Fertilization, particularly nitrogen, alters the leaf area index (LAI), plant height, and tiller density, thereby modifying interception capacity and influencing the balance between interception loss and soil water recharge [14,15,16]. High nitrogen inputs, while increasing interception, also enhance photosynthetic capacity and biomass accumulation, partially offsetting the evaporative losses. This interaction links nutrient management directly to microclimatic water fluxes, suggesting that canopy traits are pivotal in optimizing both water and nitrogen use efficiency. Furthermore, long-term assessments emphasize that nitrogen overuse in intensive regions such as North China leads not only to soil water imbalance but also to groundwater nitrate contamination, underlining the need for integrated practices [17].

While previous studies have explored nitrogen or sprinkler irrigation alone [6,9], the interactive effects of nitrogen rates, solid-set sprinkler irrigation, and dry-hot wind, three key factors for winter wheat production in the North China Plain, remain unquantified. Specifically, three critical knowledge gaps exist: (1) How does nitrogen supply regulate canopy interception and soil water–nitrogen dynamics under sprinkler irrigation? (2) What are the yield compensation mechanisms of winter wheat under dry-hot wind stress at different nitrogen levels? (3) What is the optimal nitrogen rate for balancing yield, WUE, and NUE when combining sprinkler irrigation and dry-hot wind mitigation?

This study aimed to address these gaps by: (1) Quantifying the effects of nitrogen rates on winter wheat canopy interception, soil water content dynamics, and nitrate-N distribution under solid-set sprinkler irrigation; (2) Clarifying the physiological mechanisms of yield compensation (e.g., spike number, grain filling) under dry-hot wind stress at different nitrogen levels, using indicators such as flag leaf SPAD value and grain-filling rate; (3) Identifying the optimal nitrogen application rate for improving yield stability and resource use efficiency in the North China Plain. The results are expected to provide a scientific basis for integrated water–nitrogen management of winter wheat under sprinkler irrigation and climate stress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Site

The field experiment was conducted from March to June 2025 at the Comprehensive Experimental Base of the Hebei Science and Technology Innovation Service Center in Hebei Province, China (37.93° N, 114.43° E). The experimental site is located on the alluvial fan plain at the eastern foothills of the Taihang Mountains in the North China Plain, with an average elevation of approximately 69 m. The region has a warm temperate, semi-humid continental monsoon climate, with a mean annual temperature of 13.7 °C and a long-term average precipitation of 604.7 mm. The major grain crops in this area are winter wheat and summer maize. The soil type is classified as loamy sand based on the soil texture triangle [18]. The average field capacity (FC) of the 0~40 cm soil layer was 0.34 cm3·cm−3, and the wilting point (WP) was 0.04 cm3·cm−3. The physicochemical properties of soil samples collected from the 100 cm depth were analyzed. The results showed that the soil organic matter content was 0.17%, available phosphorus was 23.4 mg·kg−1, nitrate nitrogen was 32.2 mg·kg−1, ammonium nitrogen was 10.58 mg·kg−1, and available potassium was 55.0 mg·kg−1 [19].

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Crop Cultivation and Basic Management

The winter wheat variety used in the experiment was Zhongxinmai-998, which was sown on 24 October 2024, and harvested on 10 June 2025. A wide-narrow row planting pattern was adopted, with the wide row spacing set at 35 cm and the narrow row spacing at 15 cm. The seeding rate was 265 kg·ha−1. The seeding density was set at 550 grains·m−2. During the experiment, weeds were mainly controlled manually, and pest management was conducted through pesticide spraying. Manual weeding was performed every 7 days, and insecticide was applied once at the jointing stage and once at the grain-filling stage. At sowing, basal fertilizer was applied uniformly. Based on the pure nutrient content, 50 kg·ha−1 of nitrogen, 102 kg·ha−1 of phosphorus, and 60 kg·ha−1 of potassium were applied.

2.2.2. Irrigation System and Scheduling

A fixed solid-set sprinkler irrigation system was used to conduct irrigation treatments. Irrigation amounts in the experiment were determined according to the cumulative difference between the reference evapotranspiration using the FAO-recommended Penman–Monteith method and the actual precipitation. Irrigation was applied when this cumulative difference reached 30~60 mm. The calculation formula is as follows [20]:

where Rn is the net radiation at the crop surface (MJ·m−2·d−1), G is the soil heat flux density (MJ·m−2·d−1), Δ is the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve at the mean air temperature (kPa·°C−1), γ is the psychrometric constant (kPa·°C−1), T is the mean air temperature at 2 m height (°C), u2 is the wind speed measured at 2 m height (m·s−1), and (es − ea) represents the saturation vapor pressure deficit (kPa).

2.2.3. Plot Layout and Replication

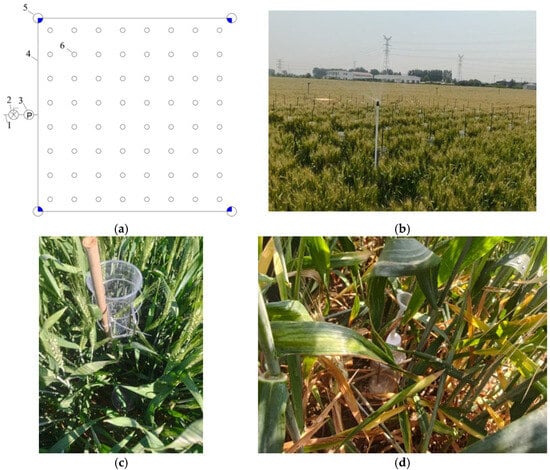

Five nitrogen (N) treatments were established, each with three replicates, resulting in a total of 15 experimental plots. Each plot measured 8 m × 8 m, with 1 m buffer strips separating adjacent plots. The spatial arrangement of the experimental plots is shown in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) Aerial view of the experimental plots. (b) Detailed illustration of the pipeline layout for an individual nitrogen-treatment plot with three replicates: 1—water supply source; 2—75-mm PVC main pipeline; 3—ball valve; 4—gate valve; 5—pressure gauge; 6—quick-coupling fertilizer injection port; 7—40-mm PVC sub-main pipeline.

A solid-set sprinkler irrigation system was used in the experiment. Water was supplied through a 75-mm PVC main pipeline (80 m in length), which delivered water from the source to the field. A ball valve was installed at the end of the main pipeline for pressure regulation. The plots of treatments N1–N5 were symmetrically arranged on both sides of the main pipeline. To facilitate fertigation, the three replicate plots of each nitrogen treatment shared a single 40-mm PVC sub-main pipeline. Each sub-main pipeline was equipped sequentially with a gate valve, a pressure gauge, and a quick-coupling fertilizer injection port, as illustrated in Figure 1b. Downstream, water was distributed to individual plots, where ball valves and pressure gauges were installed before entry for flow regulation and monitoring. The pipeline was then reduced to a 32-mm lateral within each plot.

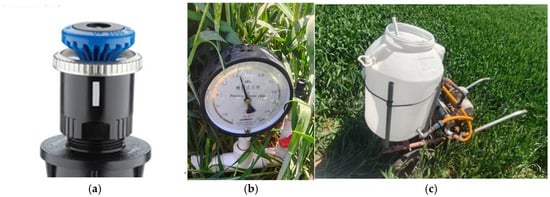

MP3000 rotary sprinklers (Hunter Industries Inc., San Marcos, TX, USA), as shown in Figure 2a, were installed in a solid-set configuration at the four corners of each plot. Each sprinkler was mounted on a 20-mm PVC riser at a height of 1.2 m above the ground, with a spraying angle of 90°, ensuring uniform water application confined within plot boundaries.

Figure 2.

Key components of the solid-set sprinkler irrigation system: (a) MP3000 rotary sprinkler head; (b) pressure gauge; (c) plunger pump unit with a fertilizer tank.

During irrigation, system pressure was maintained at 0.275 MPa, as shown in Figure 2b, corresponding to a sprinkler application rate of 11 mm h−1. The total irrigation amount was controlled by adjusting the irrigation duration.

2.3. Experimental Treatments

2.3.1. Nitrogen Application Treatments

In this experiment, water–fertilizer integrated irrigation (fertigation) was implemented using a piston injection pump as shown in Figure 2c, and nitrogen application treatments are summarized in Table 1. A ZFB150 single-cylinder plunger pump was used for fertigation, which is widely applied in agricultural irrigation systems due to its stable discharge and reliable pressure performance [21]. The pump had a nominal discharge capacity of 150 L·h−1 and a maximum operating pressure of 1.0 MPa, ensuring stable fertilizer delivery during fertigation [22].

Table 1.

Nitrogen application rates under different fertilization treatments.

To prevent fertilizer retention and clogging in pipelines and sprinkler nozzles, the irrigation system was flushed with clean water for at least 30 min before fertigation and immediately after completion, ensuring uniform fertilizer application and reliable system operation [21].

2.3.2. Dry-Hot Wind Mitigation Irrigation Treatments

The dry-hot wind mitigation irrigation treatments were implemented based on the nitrogen application treatments described in Section 2.3.1. Within each nitrogen treatment, the three replicate plots received different sprinkler irrigation depths prior to dry-hot wind events, forming a two-factor factorial design combining nitrogen level and mitigation irrigation.

Three irrigation regimes were applied following Cai et al. (2021) [23]: a non-irrigated control (0 mm) and two sprinkler irrigation depths (2.5 mm and 5 mm), as shown in Table 2. Preventive sprinkler irrigation was conducted 1~2 h before the predicted onset of dry-hot wind events, which were defined as air temperature exceeding 33 °C and relative humidity below 30%. Irrigation was scheduled between 10:00 and 11:00 under low wind speed conditions to minimize evaporation and drift losses.

Table 2.

Irrigation Treatments for Alleviating Hot Dry Wind Stress in Winter Wheat.

2.4. Measurement

2.4.1. Meteorological Data

Meteorological data were collected using a HOBO U30 automatic weather station (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA, USA) located approximately 100 m from the experimental plots. Air temperature, relative humidity, net radiation (Rn), sunshine duration, wind speed and direction, precipitation, dew point temperature, and atmospheric pressure were monitored by standard sensors mounted at 2 m height. Data were recorded at 10-min intervals and aggregated to hourly means for subsequent analysis.

2.4.2. Water Distribution and Canopy Interception

Figure 3a illustrates the pipeline connection details of the experimental plots. As shown in Figure 3b, each plot designated for canopy interception measurements was divided into 1 m × 1 m grid units, with interception measurement devices installed in each grid. Figure 3c,d presents field photographs of the rain gauges and stemflow collection devices, respectively. Immediately after sprinkler irrigation, the collected water volumes were measured using an electronic balance with a precision of 0.1 g. Canopy interception (CI) was determined through a combination of field measurements and controlled indoor experiments.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic diagram of a single experimental plot equipped with rain gauges: (1) 40-mm PVC pipeline; (2) ball valve; (3) pressure gauge; (4) 32-mm PVC pipeline; (5) MP3000 rotating sprinkler, with the blue shading indicating the spraying angle; (6) locations of canopy interception collectors. (b) Canopy interception devices. (c) Collectors used in the canopy interception experiment. (d) Runoff collector.

For field measurements, prior to irrigation, 20~30 uniformly growing wheat plants per plot were marked, with adjacent vegetation trimmed to eliminate canopy overlap-induced interference. After irrigation, once intercepted droplets had fully drained down the stems, each marked plant was enclosed in a 60 cm × 30 cm plastic bag (to capture residual intercepted water), cut at the stem base, and weighed fresh using a 0.01 g precision electronic balance. Samples were oven-dried (105 °C for 30 min for enzyme deactivation, then 75 °C until constant mass with ≤0.1% change over 2 h intervals) and reweighed to determine dry mass. For verification, 20 additional uniform plants per plot were harvested pre-irrigation, sealed immediately in plastic bags to prevent moisture loss, and measured for fresh/dry mass using the same balance (following the identical oven-drying protocol).

The volume of canopy interception was calculated using Equation (2) following the method of [16].

where CI is the canopy interception (mm); W3 is the mass of intercepted water collected from the canopy (g), calculated using Equation (5); n is the number of sampled wheat plants; is the population density of wheat at the sampling site (plants·m−2).

The Christian Uniformity Coefficient (CU) was used to assess the uniformity of water distribution both above and below the canopy. CU is calculated using the following formula based on the Chinese standard “Technical Code for Sprinkler Irrigation” [24]:

where Δh is the absolute difference in water depth (mm) between the i-th measurement, and h is the mean water depth over all measurements (mm).

The absolute difference is Δh calculated as:

where is the measured water depth at the -th measurement site (mm), h is the mean water depth (mm), and n is the total number of samples for each treatment, set to 64.

where W2 is the fresh weight of wheat plants after irrigation with intercepted water (g); W1 is the dry weight of the same wheat plants used for canopy interception sampling (g); θ is the crop moisture content coefficient, calculated using Equation (6) [16].

The indoor experiment was conducted using a simplified water-absorption method. In each plot used for the canopy interception experiment, wheat plants with similar growth characteristics to those selected for the field interception measurements were chosen for laboratory testing. The roots of the collected wheat plants were coated with petroleum jelly to prevent moisture loss, and plants were immediately weighed (0.01 g precision). Each plant was fully immersed in a urea solution for 15 min, then removed, held upright to drain excess water naturally, and reweighed (0.01 g precision). The difference between post- and pre-immersion weights represents the maximum canopy interception capacity of a single plant, calculated as follows [16]:

where W0 represents the fresh weight of the wheat plant (g), W is the plant weight after immersion (g), and denotes the maximum canopy interception capacity of a single wheat plant (g). Based on the total number of sampled plants and the sampling area, the canopy interception of fertilizer solution for winter wheat can be expressed in millimeters (mm).

In the simplified water-absorption laboratory test, the urea mass concentrations were determined to match the nitrogen application rates of each plot for both fertigation events. During the first fertigation, plots N1~N5 received 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 kg·hm−2 of nitrogen, corresponding to urea mass concentrations of 0, 0.030%, 0.063%, 0.091%, and 0.13%, respectively. During the second fertigation, nitrogen application rates for plots N1~N5 were 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 kg·hm−2, with corresponding urea mass concentrations of 0, 0.024%, 0.049%, 0.073%, and 0.096%, respectively.

The layout of sub-canopy collectors was identical to that of the above-canopy collectors, with collectors placed symmetrically beside the support rod to avoid mutual interference.

Stemflow was measured using a custom-made stemflow collection device installed directly on wheat stems. The device consisted of three components: (i) a 3-mm-diameter plastic funnel with a V-shaped notch that matched the stem diameter to ensure stable attachment without slipping; (ii) a silicone tube with an inner diameter of 6 mm and an outer diameter of 7 mm, used to transport the stemflow from the funnel to the container; and (iii) a 200-mL plastic cup equipped with a pointed-mouth cap to facilitate connection with the silicone tube. Each stemflow collector was installed on wheat plants with uniform growth status and placed within 10 cm of the rainfall gauges used for above- and sub-canopy water distribution measurements. After each irrigation event, all stemflow collectors were weighed simultaneously with the above- and sub-canopy collectors. The stemflow volume was calculated as follows [16]:

where SF is the stem flow (mm), m2 is the mass of the device after irrigation (g), m1 is the mass of the device when dry (g), and is the population density of winter wheat (plants·m−2).

2.4.3. Soil Samples and Analysis

To investigate post-irrigation soil water redistribution, soil samples were collected at the centers of 2 m × 2 m grid units and at the plot center within the canopy interception experimental plots. Sampling was conducted 1 h before irrigation and at 24 h and 48 h after sprinkler irrigation. Soil samples were taken from depths of 0~20, 20~40, 40~60, 60~80, and 80~100 cm. Gravimetric soil water content was determined using the oven-drying method (105 °C to constant mass) and calculated according to Equation (9). Soil samples collected after fertigation were also used to determine cumulative soil nitrogen content.

where represents the gravimetric soil water content (%), is the wet soil mass (g), and is the dry soil mass (g).

2.4.4. Nitrogen Accumulation

To quantify nitrogen accumulation in soil and crops, total soil nitrogen was measured one day before fertigation and sampled 2~3 times within one week after fertigation to analyze its temporal variation. Total nitrogen content was determined using the Kjeldahl method. Nitrogen use efficiency of crops was evaluated using multiple indicators, and grain protein content was calculated by multiplying grain nitrogen concentration by a conversion factor of 5.7 [25]:

where NT is the total nitrogen accumulation of the plant at maturity (kg·hm−2); DM is the plant biomass at maturity (kg·hm−2); NC is the total nitrogen concentration in the plant or grain (%); NUE is the nitrogen use efficiency (kg·kg−1); Y is the grain yield (kg·hm−2); NHI is the nitrogen harvest index; NG is the grain nitrogen accumulation (kg·hm−2); PFPN is the partial factor productivity of applied nitrogen (kg·kg−1); NF is the total nitrogen application amount during the growth period (kg).

2.4.5. Growth Index

After the first fertilization on 3 April, plant height, leaf area, and wheat population density were measured at 7-day intervals, with additional measurements conducted before each sprinkler irrigation event. Plant height was measured using a steel ruler with an accuracy of 0.01 m. Leaf length and maximum leaf width were measured using a digital caliper (0.01 mm), and leaf area was estimated accordingly. Wheat population density was determined using fixed 1 m × 1 m quadrats at each sampling point: the number of plants was counted before the heading stage, while spike number was recorded after heading, and the results were converted to plant or spike density per unit area (plants/spike·m−2).

Grain yield was determined at physiological maturity using a quadrat harvesting method. In each plot, a 1 m × 1 m quadrat was selected from the central area to minimize border effects, with three replicates per treatment. Spike number per unit area (SN) was counted before harvest. All aboveground biomass within each quadrat was harvested manually, air-dried, and threshed. Grain fresh weight was recorded, and grain moisture content was measured using a portable moisture meter. Grain yield was standardized to 14% moisture content and expressed on an area basis (kg·ha−1). After threshing, grain number per spike (GN) was determined from representative subsamples, and thousand-grain weight (TGW) was measured by weighing 1000 air-dried grains. Yield components were measured simultaneously to analyze yield formation under different treatments.

2.5. Data Processing

All data were initially organized using Microsoft Excel 2021. Prior to statistical analysis, tests for normality and homogeneity of variance were performed to ensure the validity of subsequent analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted in a Python environment configured in Visual Studio Code version 1.63.0 using Jupyter Notebook version 6.4.8. One-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was applied to evaluate the effects of different nitrogen application rates on wheat yield components and final grain yield under solid-set sprinkler irrigation. When significant differences were detected (p < 0.05), mean comparisons were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test. All figures were generated using Python version 3.11.5 within the vs. Code environment.

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Conditions and Sprinkler Irrigation

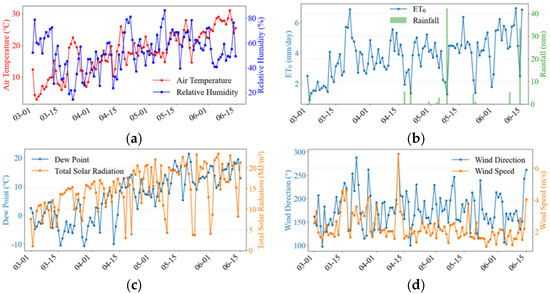

The meteorological station at the experimental site continuously recorded key weather variables, including temperature, humidity, dew point temperature, wind direction, wind speed, and solar radiation, from 1 March 2025 to 15 June 2025, the wheat harvest date. The temporal variations of these meteorological factors are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Daily variations of key meteorological factors during the 2025 winter wheat growing season: (a) air temperature and relative humidity; (b) reference evapotranspiration (ET0) and rainfall; (c) dew point temperature and daily total solar radiation; (d) wind direction and wind speed.

During the monitoring period, air temperature, dew point temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, and reference evapotranspiration (ET0) exhibited pronounced seasonal variations. The total rainfall recorded by the microclimate station was 110.84 mm. When the cumulative irrigation depth reached 20~60 mm, or when fertigation was required for the water–fertilizer integration experiment, the irrigation trial was initiated. As a result, 4 sprinkler irrigations were conducted and the total irrigation amount for winter wheat was 143.10 mm. The irrigation dates, irrigation depths, and key meteorological parameters are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Irrigation dates, irrigation depths, and major meteorological variables.

3.2. Canopy Interception and Water Distribution Responses to Nitrogen

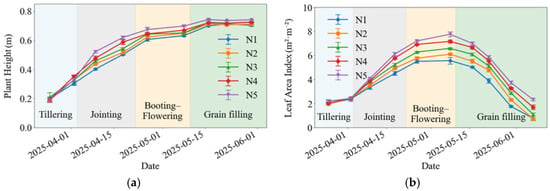

The temporal variations of winter wheat plant height and leaf area index (LAI) under different nitrogen treatments are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Temporal variance of the growth indices of winter wheat for different nitrogen treatments (a) plant height; (b) leaf area index (LAI).

Figure 5a illustrates the temporal dynamics of winter wheat plant height under different nitrogen treatments throughout the growing season. After the onset of the jointing stage on 3 April 2025, plant height increased continuously and maintained a relatively rapid growth rate until the booting–flowering stage on 22 April 2025, indicating that this period represented the main phase of stem elongation. Following the booting–flowering stage, the rate of increase in plant height gradually decreased. After the onset of the grain-filling stage on 10 May 2025, plant height remained nearly constant, suggesting that the maximum plant height had been reached at the early grain-filling stage.

Across all observation dates, the N5 treatment consistently exhibited the greatest plant height, whereas the N1 treatment showed the lowest values. Analysis of variance indicated that the advantage of the N5 treatment became apparent shortly after the first nitrogen application at the tillering stage on 2 April 2025, after which its plant height remained significantly higher than that of the other treatments. The N4 treatment showed relatively greater plant height during the jointing stage; however, this advantage was temporary, and no significant differences were observed between N4 and the other treatments during the subsequent booting–flowering and grain-filling stages. In addition, compared with the first nitrogen application, the second nitrogen application on 28 April 2025 during the booting–flowering stage resulted in a relatively smaller increase in plant height.

Figure 5b illustrates the temporal dynamics of the leaf area index (LAI) of winter wheat under different nitrogen application treatments throughout the growing season. Before the first nitrogen application on 2 April 2025, LAI values were similar among treatments. After the first nitrogen application, LAI began to diverge among treatments. With the initiation of nitrogen supply and the transition of wheat into the jointing stage, LAI increased rapidly in all treatments, while the magnitude of increase was closely related to nitrogen application level.

Compared with the low-nitrogen treatments, N4 and N5 exhibited more pronounced leaf area expansion, indicating a stronger promoting effect of higher nitrogen rates on canopy development. Following the second nitrogen application on 28 April 2025, LAI in the N4 and N5 treatments increased further and remained significantly higher than that in the other treatments during most of the growing period.

Across all treatments, LAI reached its maximum during the booting–flowering stage and then gradually declined after entering the grain-filling stage. The decrease in LAI during grain filling was more pronounced under low-nitrogen treatments, whereas N4 and N5 maintained relatively higher LAI levels, reflecting a greater capacity for leaf area retention.

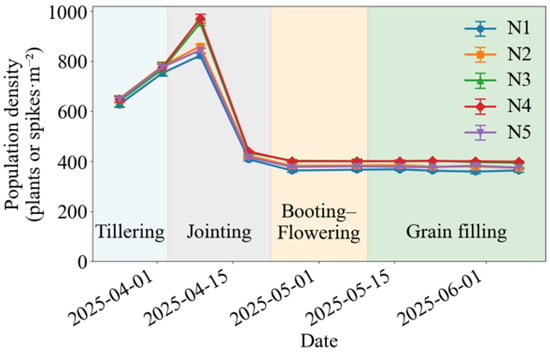

As shown in Figure 6, during the tillering stage, population density represented the number of wheat plants per unit area. All treatments received the same basal nitrogen rate (50 kg·hm−2), resulting in only minor differences in population density among treatments. After nitrogen application at the tillering stage, population density increased rapidly and reached a maximum in early April.

Figure 6.

Changes in wheat population density under different nitrogen application rates and split application regimes.

Following the first nitrogen application on 2 April 2025, population density increased with increasing nitrogen rate within a certain range. The highest population densities were observed under the N3 and N4 treatments. In contrast, a further increase in nitrogen input under the N5 treatment did not lead to a continued increase in population density; instead, population density under N5 was significantly lower than that under N3 and N4.

Subsequently, population density declined markedly across all treatments during the later jointing stage. From late April onward, when population density was expressed as the number of spikes per unit area during the booting–flowering stage, values became relatively stable, and differences among nitrogen treatments gradually diminished. The second nitrogen application on 28 April 2025 had a limited effect on spike number per unit area.

Table 4 summarizes the measured irrigation depths and their uniformities above and below the canopy, as well as canopy interception (CI) and stemflow (SF), during the irrigation events on 28 April and 28 May 2025.

Table 4.

The measured water above and below the crop canopy, distribution uniformity at both levels, canopy interception (CI), and stemflow (SF).

On 28 April, the average above-canopy irrigation depth ranged from 41.84 to 46.54 mm among treatments, with corresponding irrigation uniformity coefficients above the canopy (CUac) between 74.49% and 83.56%. The sub-canopy irrigation depth varied within a relatively narrow range (28.64~29.31 mm), and the irrigation uniformity coefficients below the canopy (CUbc) ranged from 76.59% to 83.72%. During this irrigation event, CI values ranged from 1.16 to 1.40 mm, while SF values varied from 3.39 to 4.52 mm.

On 28 May, the above-canopy irrigation depth decreased to 21.84–26.12 mm, with CUac values of 70.82~79.03%. The sub-canopy irrigation depth ranged from 11.54 to 16.24 mm, and CUbc values varied between 66.54% and 81.49%. Correspondingly, CI values ranged from 0.97 to 1.26 mm, while SF increased to 5.11~6.32 mm across treatments.

Compared with 28 April, canopy interception tended to be lower and stemflow higher during the 28 May irrigation event across all nitrogen treatments, indicating clear temporal differences in rainfall redistribution characteristics associated with crop growth stages.

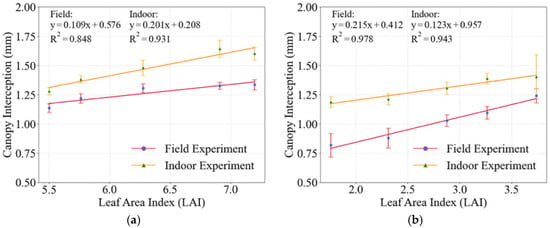

As shown in Figure 7, canopy interception (CI) increased with increasing leaf area index (LAI) in both field and indoor experiments on both measurement dates. Significant linear relationships between CI and LAI were observed in all cases (R2 = 0.848–0.978). On 28 April, the slope of the CI–LAI regression was lower in the field experiment (0.109) than in the indoor experiment (0.201). In contrast, on 28 May, the CI–LAI slope was higher in the field experiment (0.215) than in the indoor experiment (0.123). For both dates, the intercepts of the indoor regression lines were higher than those of the field experiments.

Figure 7.

Comparison of canopy water storage between field and indoor experiments on different dates: (a) Field and indoor canopy water storage on 28 April 2025; (b) Field and indoor canopy water storage on 28 May 2025.

3.3. Temporal and Spatial Variations of Soil Nitrate Content

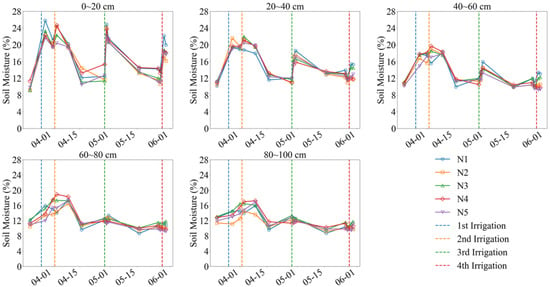

As shown in Figure 8, the average soil water content at different soil depths, calculated using the five-point sampling method, indicated that soil water content exhibited a clear depth-dependent response to sprinkler irrigation events throughout the observation period, with the magnitude of variation decreasing as soil depth increased. The 0~20 cm soil layer showed the largest fluctuation, with an average variation of approximately 15~18%. In contrast, the average variation in soil water content decreased to about 8~12% in the 20~40 cm layer and 6~9% in the 40~60 cm layer. The 60~80 cm layer exhibited a smaller variation of approximately 4~6%, while the deepest layer (80~100 cm) showed the smallest change, with an average variation of only 2~4%.

Figure 8.

Changes in Soil Moisture Content Before and After Irrigation.

Across different nitrogen treatments, the vertical distribution pattern and depth-dependent variation of soil water content were highly consistent. Soil water content in the 0~20 cm layer responded most sensitively to sprinkler irrigation events, exhibiting pronounced temporal fluctuations under all nitrogen treatments. Soil water content in the 20~60 cm layer also responded to irrigation events, but with a reduced magnitude compared to the surface layer. In contrast, soil water content in the 60~100 cm layer showed only slight increases following the first two irrigation events, with an average increase of less than 3%, and remained nearly unchanged during the subsequent irrigation events.

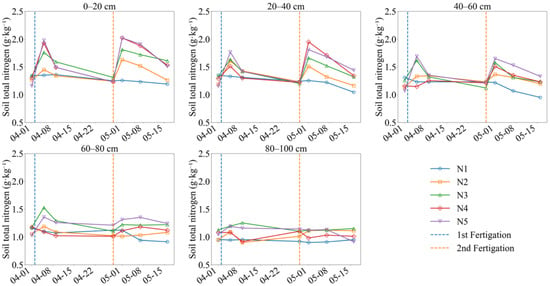

Figure 9 shows the temporal dynamics of soil total nitrogen content across different soil depths under different nitrogen treatments. The first nitrogen application was conducted on 2 April 2025, and soil samples were collected on 1 April, 5 April, and 9 April 2025 from the 0~100 cm profile at 20 cm intervals. In the 0~20 cm layer, soil total nitrogen was highly correlated with nitrogen application rates. Plots receiving nitrogen treatments N3, N4, and N5 showed substantially higher soil total nitrogen content than those under N1 and N2, with N5 exhibiting the largest increase following the fertigation event. Between 1 April and 5 April, total nitrogen in N5 increased from 1.33 g·kg−1 to 1.96 g·kg−1, an increment of 0.63 g·kg−1, whereas the N1 treatment (with no additional nitrogen applied) increased by only 0.01 g·kg−1 over the same period.

Figure 9.

Soil Total Nitrogen Dynamics at Different Depths Before and After Fertigation Under Nitrogen Treatments.

In the 20~40 cm soil layer, nitrogen content also increased with nitrogen application rate, but the magnitude of change was smaller than that observed in the 0~20 cm layer. For instance, in the N4 treatment, total nitrogen increased from 1.21 g·kg−1 to 2.03 g·kg−1, an increment of 0.82 g·kg−1. In deeper soil layers (40~60 cm and below), total nitrogen exhibited minimal variation, aligning with the observation that soil moisture changes were primarily concentrated in the upper 0~40 cm layer. This suggests that changes in soil total nitrogen are closely coupled with soil moisture dynamics.

Following the second fertilization event on 28 April 2025, the temporal variation in soil total nitrogen content was generally consistent with that observed after the first fertilization. Changes in soil total nitrogen were mainly concentrated within the 0~40 cm soil layer, and the vertical distribution pattern closely coincided with the temporal dynamics of soil moisture.

3.4. Yield and Resource Use Efficiency Responses to Nitrogen and Dry-Hot Wind

Table 5 indicates that different nitrogen application treatments had significant effects on the yield components and final grain yield of winter wheat. As the nitrogen application rate increased, the number of spikes per hectare increased significantly, rising from the lowest value of 3.632 × 106 hm−2 under the N1 treatment to the maximum value of 3.984 × 106 hm−2 under the N4 treatment.

Table 5.

Yield components and their coefficients of variation under different nitrogen application rates.

Based on Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05), thousand-grain weight showed no significant differences among nitrogen treatments overall, with only slight variation. Only the N5 treatment exhibited a significantly higher thousand-grain weight than the remaining treatments, indicating that thousand-grain weight is relatively less sensitive to nitrogen supply.

Significant differences in final grain yield were observed among the nitrogen application treatments. Yield under N4 (10,264.5 kg·hm−2) and N5 (10,195.5 kg·hm−2) was markedly higher than that under the other treatments. The yield improvement was primarily attributed to increases in spike number and grains per spike, rather than to changes in thousand-grain weight. Overall, appropriate nitrogen application substantially enhanced key yield components—particularly spike number and grain number per spike—thereby promoting grain yield in winter wheat. However, compared with the N4 treatment, further increasing nitrogen input under the N5 treatment did not result in additional yield gains.

Prior to sowing, the average soil water content in the 0~100 cm profile was 21.2%. After harvest, the corresponding value decreased to 16.7%, suggesting that approximately 45 mm of soil water was consumed by wheat during the entire growing season. Considering a natural rainfall amount of 110.84 mm and a total irrigation depth of 143.10 mm, the actual crop evapotranspiration (ETa) was calculated as 298.94 mm.

Clear differences in water use efficiency (WUE) were observed among nitrogen treatments. The N4 treatment exhibited the highest WUE at 3.43 kg·m−3, followed by N5 at 3.41 kg·m−3. In contrast, N1 had the lowest WUE (2.55 kg·m−3), while N2 and N3 exhibited intermediate values of 2.67 kg·m−3 and 2.98 kg·m−3, respectively. Under similar water consumption conditions, WUE increased progressively as nitrogen input increased up to 212 kg·hm−2. In this study, the N4 treatment (212 kg·m−3) resulted in both the highest yield and the maximum WUE. However, when nitrogen input was further elevated to 266 kg·hm−2 (N5), yield declined slightly compared with N4, and WUE also decreased marginally. This finding suggests that excessive nitrogen application may reduce the marginal benefits of nitrogen on water productivity and highlights the importance of identifying optimal nitrogen input levels.

To evaluate nitrogen allocation to grain and the efficiency of nitrogen utilization under different nitrogen application treatments, the grain nitrogen content, nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), and partial factor productivity of applied nitrogen (PFPN) were calculated. The nitrogen harvest index (NHI) was set to 0.7 [26], and the grain protein content was assumed to be 5.7%. Based on these parameters, grain nitrogen content was estimated from the total plant nitrogen content, and grain protein content was subsequently calculated. Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and the partial factor productivity of applied nitrogen (PFPN) were determined using aboveground biomass at harvest and total nitrogen input. The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Mean values, standard deviations, and coefficients of variation of total plant nitrogen concentration, grain nitrogen concentration, grain protein content, total plant nitrogen accumulation, nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), and partial factor productivity of applied nitrogen (PFPN) under different nitrogen treatments.

The data indicate that nitrogen fertilization had significant effects on total plant nitrogen accumulation, grain nitrogen content, grain protein concentration, and nitrogen use efficiency (p < 0.05). Total plant nitrogen accumulation increased markedly with higher nitrogen application rates, rising from 422.5 kg·hm−2 under N1 to a maximum of 493.4 kg·hm−2 under N4, followed by a slight decline to 483.3 kg·hm−2 in N5.

Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) responded strongly to nitrogen application. NUE decreased from 18.0 kg·kg−1 in N1 to 17.0 kg·kg−1 in N2, but subsequently increased across treatments N3 to N5, reaching 21.1 kg·kg−1, indicating improved nitrogen utilization under medium-to-high nitrogen supply. In contrast, PFPN decreased sharply with increasing nitrogen rate, declining from 152.3 kg·kg−1 in N1 to 38.3 kg·kg−1 in N5. This substantial reduction indicates that yield gains per unit of nitrogen input diminish under high nitrogen application, suggesting possible nitrogen oversupply when irrigation remains constant.

Table 7 shows that under dry-hot wind conditions, different sprinkler irrigation levels had distinct effects on the yield components of winter wheat. At the same nitrogen application rate, variations in sprinkler irrigation amount used to mitigate dry-hot wind had no significant effects on spike number or grains per spike, indicating that dry-hot wind events occurring during the grain-filling stage had limited influence on yield components formed earlier.

Table 7.

Significance analysis of wheat yield components under different nitrogen application rates and irrigation levels following dry-hot wind treatment.

In contrast, thousand-grain weight exhibited a more sensitive response to sprinkler irrigation regulation. Across the three nitrogen treatments, applying 2.5 mm of sprinkler irrigation under dry-hot wind conditions significantly increased the thousand-grain weight, which consequently contributed to an increase in final grain yield. Among all nitrogen treatments, a significant yield increase was observed only in the N1 treatment, whereas no significant yield enhancement was detected in the remaining treatments. Excluding the N1 treatment, the yield variation induced by dry-hot wind ranged from −0.6% to 4.7%.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effects of Nitrogen Supply and Sprinkler Irrigation on Canopy Structure and Water Interception

Nitrogen supply and sprinkler irrigation jointly influenced canopy structure and water interception in winter wheat by regulating leaf area development, canopy closure, and the interactions between applied irrigation water and the crop canopy [6,16]. The results of this study showed that increasing nitrogen application significantly increased plant height and leaf area index (LAI), with more pronounced effects observed under the N4 and N5 treatments (Figure 5). Higher plant height and LAI promoted the development of a denser canopy with a more vertically structured architecture [27]. Previous studies have demonstrated that such changes in canopy structure can significantly increase leaf surface area and water retention interfaces, thereby enhancing canopy interception of rainfall and irrigation water and altering water redistribution within the canopy–soil system [15,28]. This is consistent with the canopy interception patterns presented in Figure 7 of the present study.

Under sprinkler irrigation, canopy interception of winter wheat increased significantly with increasing leaf area index (LAI) across nitrogen treatments (Table 4; Figure 7). This indicates that nitrogen, by promoting canopy expansion—primarily reflected by increased LAI and a denser canopy structure—became a dominant factor regulating canopy interception capacity. A denser canopy facilitates droplet retention on leaf surfaces and delays the passage of sprinkler-applied droplets through the crop canopy, thereby increasing canopy interception. However, this may also enhance evaporative losses of sprinkler water from wetted leaf surfaces [29]. Nevertheless, at the scale of individual sprinkler irrigation events, the absolute magnitude of canopy interception remained far lower than the total irrigation amount (with a maximum interception of 1.26 mm in this study). Therefore, when other influencing factors on sprinkler-applied water are excluded, the change in canopy interception induced by nitrogen-related canopy modifications could increase interception by no more than 0.3 mm under field conditions. However, in fertigation sprinkler irrigation systems, the amount of fertilizer intercepted by the canopy and the capacity of wheat leaves to absorb nitrogen from intercepted fertilizer solutions are issues that were not considered in the present study.

Sprinkler irrigation operations are generally scheduled under calm or light wind conditions to reduce evaporation–drift losses, which are primarily controlled by meteorological factors such as wind speed, air temperature, and relative humidity [30,31,32,33]. Despite these measures, the field-measured canopy interception of winter wheat was still 12~23% lower than that obtained under indoor experimental conditions (Figure 7). This difference may be attributed to the effective suppression of wind and evaporation processes in the indoor environment, and may also be related to the immersion method used in the indoor experiments, which increased the water retention interface [34]. Further experiments are therefore required to explore the maximum canopy interception capacity of winter wheat.

Field experiments better reflect canopy interception processes under actual production conditions, where interception is jointly influenced by atmospheric evaporative demand and irrigation methods. Similar differences between indoor and field measurements of canopy interception have been reported in previous studies [28,35], further indicating that canopy interception is determined not only by canopy structure but also by meteorological conditions and irrigation practices.

In addition, changes in canopy physiological status also affected interception dynamics. Comparisons of the crop moisture coefficient (θ) between the two observation periods suggest that both indoor experiments and outdoor measurements may be influenced by this coefficient, which may be related to the series of equations used to calculate the maximum canopy interception capacity of a single wheat plant.

Overall, this study demonstrates that under sprinkler irrigation, nitrogen supply indirectly affects canopy interception capacity by regulating canopy structure and physiological status, whereas sprinkler irrigation determines how this potential interception capacity is expressed under specific meteorological conditions. Therefore, optimizing nitrogen application to maintain an appropriate leaf area index (LAI), in combination with appropriate sprinkler irrigation scheduling strategies, is essential for balancing canopy interception, soil water replenishment, and overall water use efficiency.

4.2. Coupling Relationship Between Soil Moisture and Nitrogen Under Sprinkler Irrigation Conditions

Under fertigation conditions, fertilizers are first dissolved in irrigation water and then uniformly applied to the field through sprinkler irrigation, which facilitates the synchronized supply of water and nitrogen and improves nutrient use efficiency [6,36,37].

Soil inorganic nitrogen mainly exists in two forms: nitrate nitrogen, which is highly mobile and prone to leaching with water movement, and ammonium nitrogen, which is readily adsorbed by soil colloids and exhibits lower mobility. The transport of both nitrogen forms is highly dependent on soil water movement [38]. Therefore, the infiltration depth of sprinkler-applied water directly determines the primary zones of nitrogen transport and distribution, and the appropriate control of irrigation amounts can effectively reduce the risk of deep nitrogen leaching [39].

The results of this study showed that vertical redistribution of soil moisture following sprinkler irrigation was mainly confined to the 0~40 cm soil layer, with progressively weaker responses as soil depth increased (Figure 8). This distribution pattern closely corresponded to the variation in soil total nitrogen content (Figure 9), further confirming the coupling between soil water dynamics and nitrogen migration under fertigation conditions. Under high nitrogen treatments, nitrogen accumulation was more pronounced in the surface soil layer (0~20 cm), whereas only limited increases were observed below a 40 cm depth (Figure 9). Previous studies have reported that more than 90% of wheat roots are distributed within the 0~40 cm soil layer [40], indicating that under the irrigation regime applied in this experiment, most nitrogen remained within the active root zone of winter wheat. This pattern can be attributed to the downward transport of nitrate nitrogen driven by soil water, while ammonium nitrogen is initially retained in the surface soil and subsequently redistributed following nitrification [41]. By optimizing nitrogen application strategies (e.g., split applications) and irrigation regimes, nitrogen accumulation within the root zone can be further synchronized, thereby improving nitrogen use efficiency in winter wheat and reducing vertical nitrogen migration and associated environmental losses [42].

4.3. Yield Formation Mechanisms Under Nitrogen Gradients and Heat Stress

In this study, the yield response of winter wheat to nitrogen input was mainly reflected through variations in spike number and grains per spike. Spike number formation primarily depends on plant population after the tillering stage and the survival of effective tillers into subsequent growth stages, whereas grains per spike are closely associated with wheat growth and development during the spike differentiation and flowering stages [6,43].

Dry-hot wind stress in winter wheat mainly occurs during the grain-filling period, when spike number and grains per spike have already been largely determined, and changes in yield structure are therefore more likely to be reflected in thousand-grain weight [9]. Among the nitrogen treatments, Duncan’s multiple range test showed that only the N5 treatment exhibited a significant advantage in thousand-grain weight (Table 5), indicating that grain mass during the grain-filling stage is more responsive to nitrogen supply at higher nitrogen levels [44]. As shown in Figure 7, differences in yield structure among plots under different nitrogen levels were mainly observed in thousand-grain weight, whereas spike number and grains per spike showed no significant differences [45]. Based on previous studies, this variation may be related to differences in the maintenance of leaf photosynthetic function during grain filling. As shown in Figure 5b, the moderate to high nitrogen treatments (N4 and N5) maintained relatively high LAI values during the late grain-filling stage, providing a physiological basis for sustained assimilate supply and helping to explain the observed differences in thousand-grain weight among nitrogen treatments [46].

Water use efficiency (WUE) increased significantly with nitrogen application up to the N4 treatment (Table 5), suggesting that moderate nitrogen input improves yield formation efficiency per unit water consumption. This trend may be associated with nitrogen-induced optimization of canopy structure and improvements in photosynthetic performance [47]. However, under the N5 nitrogen level, WUE did not further increase and even showed a slight decline, which may be attributed to increased transpiration and non-productive water consumption caused by excessive canopy density [48]. In contrast, partial factor productivity of nitrogen (PFPN) decreased significantly with increasing nitrogen rates (Table 6), indicating a continuous reduction in the marginal yield benefit per unit nitrogen input.

Overall, nitrogen application played an important role in regulating winter wheat canopy structure, soil water–nitrogen coupling processes, and the formation of spike number and grains per spike, thereby influencing final yield. Under dry-hot wind stress, sprinkler irrigation applied during the grain-filling period at an irrigation amount of 2.5 mm significantly increased thousand-grain weight across different nitrogen levels, contributing to yield formation. In this study, a nitrogen application rate of 212 kg N ha−1 achieved a relatively balanced performance in terms of grain yield, water use efficiency, and nitrogen use efficiency. Sprinkler irrigation not only provided essential water and nitrogen supply to the crop, but also acted as a microclimate regulator during dry-hot wind events at the grain-filling stage by reducing air temperature, increasing air humidity, and lowering vapor pressure deficit [8,29]. It is worth noting that, in contrast to some previous studies, the maximum thousand-grain weight in this study did not occur under the 5 mm irrigation treatment, but was more frequently observed under the 2.5 mm irrigation treatment. However, several studies have also suggested that sprinkler irrigation amounts should not be excessively high, and that irrigation depths of approximately 1–2 mm are sufficient to effectively reduce canopy temperature during dry-hot wind events. Therefore, the mechanisms underlying the relationship between sprinkler irrigation amount and dry-hot wind mitigation still require further investigation through additional experiments [8,11,23]. Overall, under increasing climate variability, combining moderate nitrogen application with timely sprinkler irrigation and appropriate irrigation amounts in response to dry-hot wind stress can contribute to stable, high winter wheat yields and efficient resource use. Excessive nitrogen input provides limited yield benefits while reducing water and nitrogen use efficiency, whereas insufficient nitrogen restricts canopy development and weakens wheat resistance to dry-hot wind stress. Therefore, coordinated optimization of water and nitrogen management remains a key approach for improving productivity and resource use efficiency in winter wheat production systems of the North China Plain.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the interactive effects of nitrogen application rates, solid-set sprinkler irrigation, and dry-hot wind stress on winter wheat in the North China Plain. Nitrogen application significantly regulated canopy development, soil water–nitrogen dynamics, and dry-hot wind tolerance, with yield and water-nitrogen use efficiency (WUE, NUE) showing a first-increasing-then-decreasing trend with increasing nitrogen input. The moderate nitrogen rate of 212 kg N ha−1 (N4 treatment) achieved the optimal balance of high yield (10,264.5 kg·hm−2), WUE (3.43 kg·m−3), and NUE (20.8 kg·kg−1), while excessive nitrogen reduced marginal benefits. Preventive sprinkler irrigation synergized with moderate nitrogen application to mitigate dry-hot wind damage, providing a practical management strategy for sustainable winter wheat production. Long-term multi-location trials are needed to verify the generalizability of the optimal nitrogen rate across different soil and climatic conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and D.H.; methodology, Y.X. and D.H.; software, D.H.; validation, D.H. and Y.X.; formal analysis, D.H. and Y.X.; investigation, D.H. and Y.X.; resources, Y.X.; data curation, D.H. and T.X.; writing—original draft preparation, D.H. and Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.X., T.X., J.W. and H.Y.; visualization, D.H.; supervision, Y.X.; project administration, Y.X.; funding acquisition, Y.X. and H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers 2023YFD1900701-01 and 2023YFE0208200) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 52509077).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon any request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the workers who assisted in setting up the experimental platform, conducting weeding in the experimental field, and providing general support during the experiments. We also acknowledge the assistance of a generative AI tool in optimizing the English expression, grammar, and formatting of the manuscript. The tool was not involved in any core research procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ladha, J.K.; Pathak, H.; Krupnik, T.J.; Six, J.; Van Kessel, C. Efficiency of Fertilizer Nitrogen in Cereal Production: Retrospects and Prospects. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 87, pp. 85–156. ISBN 978-0-12-000785-1. [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes, M.J.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Weightman, R.; Snape, J.W. Identifying Physiological Traits Associated with Improved Drought Resistance in Winter Wheat. Field Crops Res. 2007, 103, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.-B.; Liu, B.-C.; He, L.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Feng, W.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Jiao, N.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Guo, T.-C. Root and Nitrate-N Distribution and Optimization of N Input in Winter Wheat. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Bragado, R.; Serret, M.D.; Araus, J.L. The Nitrogen Contribution of Different Plant Parts to Wheat Grains: Exploring Genotype, Water, and Nitrogen Effects. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kang, Y.; Wan, S. Winter Wheat Growth and Water Use under Different Drip Irrigation Regimes in the North China. Irrig. Sci. 2020, 38, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Gao, Z. Effects of Nitrogen Application at Different Levels by a Sprinkler Fertigation System on Crop Growth and Nitrogen-Use Efficiency of Winter Wheat in the North China Plain. Plants 2024, 13, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hou, L.; Lu, Y.; Wu, B.; Gong, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Vierling, E.; Xu, S. Metabolic Adaptation of Wheat Grains Contributes to a Stable Filling Rate under Heat Stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 5531–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, R. Mitigating Dry–Hot–Windy Climate Disasters in Wheat Fields Using the Sprinkler Irrigation Method. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, L.; Kirkham, M.B.; Welch, S.M.; Nielsen-Gammon, J.W.; Bai, G.; Luo, J.; Andresen, D.A.; Rice, C.W.; Wan, N.; et al. U.S. Winter Wheat Yield Loss Attributed to Compound Hot-Dry-Windy Events. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Bramley, H.; Palta, J.A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Heat Stress in Wheat during Reproductive and Grain-Filling Phases. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-J.; Kang, Y. Effect of Sprinkler Irrigation on Microclimate in the Winter Wheat Field in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 84, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, J.H.C.; Lloyd, C.R.; Lachaud, G. Estimating Sparse Forest Rainfall Interception with an Analytical Model. J. Hydrol. 1995, 170, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Li, L. Estimation of Water Interception of Winter Wheat Canopy Under Sprinkler Irrigation Using UAV Image Data. Water 2024, 16, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Mao, T.; Ma, L.; Pan, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Yang, L.; Zhai, Y. Effects of Delayed Application of Nitrogen Fertilizer on Yield, Canopy Structure, and Microenvironment of Winter Wheat with Different Planting Densities. Agronomy 2025, 15, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Jing, M.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z. Canopy Structure, Light Intensity, Temperature and Photosynthetic Performance of Winter Wheat under Different Irrigation Conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chang, J.; Tang, X.; Zhang, J. In Situ Measurement of Stemflow, Throughfall and Canopy Interception of Sprinkler Irrigation Water in a Wheat Field. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.T.; Kou, C.L.; Zhang, F.S.; Christie, P. Nitrogen Balance and Groundwater Nitrate Contamination: Comparison among Three Intensive Cropping Systems on the North China Plain. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 143, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.A.; Boersma, L.; Hart, J.W. A Unifying Quantitative Analysis of Soil Texture: Improvement of Precision and Extension of Scale. Soil Science Soc. Amer. J. 1988, 52, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Hui, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, D.; Yan, H. Detecting Water Stress in Winter Wheat Based on Multifeature Fusion from UAV Remote Sensing and Stacking Ensemble Learning Method. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Pandey, V. Reference Evapotranspiration (ETo) and Crop Water Requirement (ETc) of Wheat and Maize in Gujarat. J. Agrometeorol. 2015, 17, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Hossain, M.Z.; Khair, M.A. Design and Development of Pedal Pump for Low-Lift Irrigation. J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2007, 5, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackett, H.H.; Cripe, J.A.; Dyson, G. Positive Displacement Reciprocating Pump Fundamentals—Power and Direct Acting Types. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Pump Users Symposium, College Station, TX, USA, 22 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, D.; Shoukat, M.R.; Zheng, Y.; Tan, H.; Meng, F.; Yan, H. Optimizing Center Pivot Irrigation to Regulate Field Microclimate and Wheat Physiology under Dry-Hot Wind Conditions in the North China Plain. Water 2022, 14, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhussiny, K.T.; Hassan, A.M.; Habssa, A.A.; Mokhtar, A. Prediction of Water Distribution Uniformity of Sprinkler Irrigation System Based on Machine Learning Algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruisi, P.; Saia, S.; Badagliacca, G.; Amato, G.; Frenda, A.S.; Giambalvo, D.; Di Miceli, G. Long-Term Effects of No Tillage Treatment on Soil N Availability, N Uptake, and 15 N-Fertilizer Recovery of Durum Wheat Differ in Relation to Crop Sequence. Field Crops Res. 2016, 189, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, M.J.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Barraclough, P.B.; Holdsworth, M.J.; Kerr, S.; Kightley, S.; Shewry, P.R. Identifying Traits to Improve the Nitrogen Economy of Wheat: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Field Crops Res. 2009, 114, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Wei, X.; Song, Q.; Wang, F. Research on Estimating Rice Canopy Height and LAI Based on LiDAR Data. Sensors 2023, 23, 8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.-G.; Kang, Y.; Liu, H.-J.; Liu, S.-P. Method for Measurement of Canopy Interception under Sprinkler Irrigation. J. Irrig. Drain Eng. 2006, 132, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Li, L.; Chang, J. Energy Balance, Microclimate, and Crop Evapotranspiration of Winter Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) under Sprinkler Irrigation. Agriculture 2022, 12, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazar, A. Evaporation and Drift Losses from Sprinkler Irrigation Systems under Various Operating Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 1984, 8, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, M.A.; Roy, D.K.; Al-Ghobari, H.M.; Dewidar, A.Z. Machine Learning and Regression-Based Techniques for Predicting Sprinkler Irrigation’s Wind Drift and Evaporation Losses. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 265, 107529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, J.; Rao, M. Winter wheat canopy interception under sprinkler irrigatio. Zhongguo Nong Ye Ke Xue 2006, 39, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Araus, J.L.; Tapia, L. Photosynthetic Gas Exchange Characteristics of Wheat Flag Leaf Blades and Sheaths during Grain Filling: The Case of a Spring Crop Grown under Mediterranean Climate Conditions. Plant Physiol. 1987, 85, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.-G.; Wang, J.-P.; Ge, S.; Su, S.-K.; Bai, M.-H.; Francois, B. Investigation of Canopy Interception Characteristics in Slope Protection Grasses: A Laboratory Experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Shen, X.; Cai, X.; Yan, F.; Lu, W.; Shi, Y.-C. Effects of Heat Stress during Grain Filling on the Structure and Thermal Properties of Waxy Maize Starch. Food Chem. 2014, 143, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Shoukat, M.R.; Zheng, Y.; Tan, H.; Sun, M.; Yan, H. Improving Wheat Grain Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency by Optimizing the Fertigation Frequency Using Center Pivot Irrigation System. Water 2023, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Shan, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Effects of Fertigation Splits through Center Pivot on the Nitrogen Uptake, Yield, and Nitrogen Use Efficiency of Winter Wheat Grown in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 240, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, B.R.; Šimůnek, J.; Hopmans, J.W. Evaluation of Urea–Ammonium–Nitrate Fertigation with Drip Irrigation Using Numerical Modeling. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 86, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Jiao, Y.; Yang, M.; Wen, H.; Gu, P.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, J. Minimizing Soil Nitrogen Leaching by Changing Furrow Irrigation into Sprinkler Fertigation in Potato Fields in the Northwestern China Plain. Water 2020, 12, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, Y.; Chen, G.; Wu, Q.; Liang, X.; Zhai, Y. Effects of Planting Density on Root Spatial and Temporal Distribution and Yield of Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J.; Ouyang, Y. Controls and Adaptive Management of Nitrification in Agricultural Soils. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Wang, J.; Gong, S.; Xu, D.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Nitrogen and Irrigation Application on Water Movement and Nitrogen Transport for a Wheat Crop under Drip Irrigation in the North China Plain. Water 2015, 7, 6651–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem Kubar, M.; Feng, M.; Sayed, S.; Hussain Shar, A.; Ali Rind, N.; Ullah, H.; Ali Kalhoro, S.; Xie, Y.; Yang, C.; Yang, W.; et al. Agronomical Traits Associated with Yield and Yield Components of Winter Wheat as Affected by Nitrogen Managements. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 4852–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fang, B.; Zhang, Y. Improving Winter Wheat Grain Yield and Water-/Nitrogen-Use Efficiency by Optimizing the Micro-Sprinkling Irrigation Amount and Nitrogen Application Rate. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Reducing Nitrogen Application Rate under Different Irrigation Methods on Grain Yield, Water and Nitrogen Utilization in Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Optimizing Nitrogen Application Strategies Can Improve Grain Yield by Increasing Dry Matter Translocation, Promoting Grain Filling, and Improving Harvest Indices. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1565446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, Y.; Li, P.; Qi, X.; Rahman, S.U.; Guo, W. Effects of Nitrogen Application on Winter Wheat Growth, Water Use, and Yield under Different Shallow Groundwater Depths. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1114611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Deng, X. Physiological Mechanisms Contributing to Increased Water-Use Efficiency in Winter Wheat under Organic Fertilization. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.