Abstract

The Fantastic Four gene family encodes small, plant-specific regulatory proteins involved in developmental control; however, their roles in wheat remain poorly understood. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive genome-wide analysis of the Fantastic Four gene family in wheat. A total of 42 TaFAF genes were identified and systematically characterized in terms of their chromosomal distribution, phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, conserved motifs, and promoter cis-regulatory elements. Phylogenetic analysis classified TaFAF genes into four distinct clades, which exhibit high structural conservation but show divergent motif compositions. Expression profiling revealed tissue-specific expression patterns and suggested that a subset of TaFAF genes responded transcriptionally to heat stress in a genotype-dependent manner. Subcellular localization assays showed that representative Fantastic Four proteins were localized in the cytoplasm. Protein–protein interaction analyses indicated that TaFAF-1A.1 and TaFAF-5D.5 physically interact with the key flowering regulator TaFT1. Furthermore, haplotype analysis of TaFAF-5D.5 across 145 wheat accessions revealed a significant association with wheat growth habit, with a favorable haplotype preferentially enriched in winter wheat. Together, these results provide insights into the evolutionary diversification and functional relevance of the Fantastic Four genes and identify TaFAF-5D.5 as a candidate gene potentially associated with developmental adaptation and heat stress responses in wheat.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most widely cultivated cereal crops worldwide and provides a major source of calories and protein for the global human population [1]. Therefore, ensuring stable wheat production is a central objective of modern crop breeding programs. However, wheat growth and productivity are increasingly challenged by climate change, particularly rising temperatures and frequent heat stress episodes [2]. Heat stress adversely affects multiple stages of wheat development, from vegetative growth to reproductive processes, ultimately reducing yield and grain quality [3]. Thus, understanding the genetic mechanisms that integrate developmental regulation with stress responsiveness has become a priority for wheat improvement.

Plant development and environmental adaptation are governed by complex regulatory networks, in which small, plant-specific proteins often function as modulatory components [4]. The FAF gene family represents one such group of regulatory genes. FAF genes were first identified in Arabidopsis thaliana and encode small proteins that are highly conserved across land plants but lack recognizable functional domains [5]. Recent studies have identified FAF orthologs in tomato [6,7] and pepper [8], where they play key roles in plant development and responses to abiotic stress. FAF proteins, despite their simple structure, are crucial regulators of developmental processes. In Arabidopsis, they modulate meristem size and stem cell maintenance, suggesting their role as fine-tuners in developmental signaling [5]. Functional studies in dicot crops have further expanded the roles of FAF genes. In tomato, gain-of-function alleles and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations of FAF family members demonstrated that these genes regulate developmental progression and flowering time [7]. Notably, manipulation of specific FAF genes accelerated developmental transitions without obvious negative effects on yield, highlighting their potential value for crop improvement [6].

In addition to their roles in development, small regulatory proteins are increasingly recognized as contributors to abiotic stress responses [9,10]. Heat stress is particularly detrimental during the reproductive phase of wheat, where it disrupts key processes such as flowering, grain filling, and seed development [11]. As global temperatures rise, the occurrence of heat episodes during critical growth periods has become a major constraint on wheat productivity [12]. Elevated temperatures cause not only direct damage to cellular structures but also impair physiological processes like photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism, leading to reduced yield and quality. Although considerable progress has been made in identifying heat-responsive genes in model plants, the genetic basis of wheat’s heat stress responses is still poorly understood. This gap is mainly due to wheat’s complex hexaploid genome, which complicates the identification of heat tolerance genes. These challenges hinder the systematic identification of genetic variants linked to heat stress tolerance. While numerous heat-responsive genes encoding transcription factors, chaperones, and signaling proteins have been identified [13,14,15], the involvement of FAF genes in temperature-responsive pathways has not been well explored in major crops [8,16]. Given their regulatory roles in development, FAF genes may integrate developmental and stress-related signals, contributing to wheat’s adaptation to heat stress. Despite increasing evidence for the importance of FAF genes in dicot species, their roles in monocot crops remain poorly understood. In cereals such as rice, maize, and wheat, systematic analyses of FAF gene families are still lacking. Wheat presents a particular challenge due to its large and complex hexaploid genome, which consists of three homoeologous subgenomes (A, B, and D). Polyploidization has resulted in extensive gene duplication, with most genes present as multiple homoeologous copies, often leading to functional divergence, subfunctionalization, or differential regulation among homeologs [17,18]. Recent advances in wheat genomics, including fully annotated reference genomes and the availability of large-scale transcriptome and population-level SNP datasets, now enable comprehensive genome-wide analyses of gene families [18,19,20]. Integrating phylogenetic, structural, expression, and haplotype analyses provides a powerful framework for elucidating the evolutionary history and functional diversification of FAF genes and for linking their variation to biological functions and agronomic traits in wheat.

This study aims to address the limited understanding of the FAF gene family in wheat by conducting a systematic genome-wide analysis, with particular emphasis on its potential involvement in developmental processes and heat stress responses. We performed a comprehensive genome-wide characterization of the FAF gene family in wheat. We identified 42 TaFAF family members and analyzed their chromosomal distribution, phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, conserved motifs, and promoter cis-regulatory elements. We examined tissue-specific expression patterns and assessed transcriptional responses of TaFAF genes to heat stress. Furthermore, we investigated protein–protein interactions between selected TaFAF proteins and the key developmental regulator TaFT1 and analyzed natural sequence variation to identify haplotypes associated with wheat growth habit. Collectively, our results provide new insights into the functional diversification of TaFAF genes in wheat and highlight candidate genes that may contribute to heat stress responses and developmental adaptation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Molecular Characterization of TaFAF Genes

To identify putative TaFAF genes in wheat, all wheat peptide sequences were downloaded from the Ensembl Plants database (https://ftp.ensemblgenomes.ebi.ac.uk/pub/plants/release-61/fasta/triticum_aestivum/, accessed on 21 September 2023). The FAF domain (IPR046431) was retrieved from the InterPro database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/InterPro/, accessed on 24 September 2023) and used as a query for Hidden Markov Model (HMM)-based searches. For these searches, an E-value threshold of 1e-5 was applied, and domain coverage was set to 80% based on previous studies [21,22]. Candidate peptide sequences were further examined to confirm the presence of FAF domains using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd) and SMART (https://smart.embl-heidelberg.de). Redundant isoforms were handled by retaining only the longest isoform for each gene locus. Partial or truncated sequences were excluded using a minimum length cutoff of 100 amino acids. The wheat genome assembly used in this study was based on the IWGSC RefSeq v1.1, which is a fully annotated reference genome (https://www.ensemblgenomes.org). The chromosomal locations of the identified TaFAF genes were obtained from Ensembl Plants, and gene nomenclature was assigned according to their physical positions and genomic organization. Homoeologous relationships were determined based on sequence similarity greater than 90% among the A, B, and D subgenomes, and tandem or segmental duplication events were inferred through local sequence alignment analyses.

2.2. Phylogenetic and Structural Analyses

Full-length amino acid sequences of TaFAF proteins were aligned using MUSCLE (http://www.drive5.com/muscle/ (accessed on 27 September 2023), default parameters). A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 7 with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The phylogenetic relationships of TaFAF genes and homologues from Aegilops tauschii, Triticum turgidum, and Triticum urartu were reconstructed using the maximum likelihood method in MEGA 7 software, based on the JTT model [23]. Gene structures, including exon–intron organization, were determined by aligning coding sequences (CDS) with their corresponding genomic DNA. Conserved motifs were identified using MEME (https://meme-suite.org) and visualized with TBtools [24]. BLASTn (v2.14.0) was used to perform pairwise sequence comparisons to detect homologous regions with sequence similarity greater than 90%. Tandem duplications were inferred by identifying repeated sequences within close proximity on the same chromosome, while segmental duplications were recognized by aligning large genomic regions across different chromosomes or subgenomes.

2.3. Calculation of Protein Molecular Weight, Isoelectric Point, Ka/Ks Values, and Divergence Time

The molecular weight (MW) and isoelectric point (pI) of FAF proteins were calculated using DNASTAR 7.1 software (https://www.dnastar.com/). The MW was determined by analyzing the amino acid sequence, taking into account the molecular weight of each amino acid residue along with the contributions from the terminal amino and carboxyl groups. The pI was calculated based on the amino acid composition, particularly the ionizable residues, using their respective pKa values. The software estimates the pH at which the protein carries no net charge, providing the theoretical pI value. The Ka/Ks ratios (the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions) for each gene pair were calculated using TBtools software (v2.390), a widely used tool for sequence analysis and Ka/Ks estimation. This software performs the calculation by aligning the gene sequences and identifying synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitutions. The Ka/Ks ratio provides insight into the selective pressure acting on the genes. The divergence time (T) between duplicated gene pairs was estimated using the formula [25]:

where λ represents the mutation rate, which was set at 6.5 × 10−9 substitutions per site per year.

2.4. cis-Regulatory Element Analysis

Promoter sequences (2 kb upstream of the transcription start sites) of TaFAF genes were retrieved from WheatOmics 1.0 (http://202.194.139.32/getfasta/index.html, accessed on 5 January 2024) and analyzed for cis-regulatory elements using PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare, accessed on 10 November 2024). The identified cis-regulatory elements were classified into four categories: development-related, hormone-responsive, stress-related, and light-responsive.

2.5. Expression Analysis

Transcriptome data for TaFAF genes across various tissues and developmental stages were retrieved from expVIP (http://www.wheat-expression.com). For experimental validation, total RNA was extracted from five tissues (root, leaf, sheath, spike, and grain) of wheat cv. ‘Chinese Spring’ at the heading stage using TRIzol reagent. The plants were grown under a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle at 22 °C in a growth chamber. After sampling, tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for preservation. For the expression–haplotype relationship analysis, 16 wheat accessions with different haplotypes from the Chinese wheat mini-core collection were selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis at the seedling stage. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). qRT-PCR was conducted on a CFX96 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using ChamQ SYBR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), with Actin serving as the internal reference gene. Actin is widely recognized as a reliable internal control in many species, including wheat, and has consistently shown stable expression under various experimental conditions. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Each reaction included three biological replicates and two technical replicates. Primer sequences are listed in Table S7.

2.6. Subcellular Localization

The CDS of TaFAF-5D.1, TaFAF-1A.1, and TaFAF-5D.5 were cloned into the pAN580-GFP vector at the BglII and PstI sites. The recombinant constructs were transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells via Agrobacterium tumefaciens infiltration (strain GV3101). An mCherry-tagged cytoplasmic protein was used as a cytoplasmic marker as previously described [26]. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence was visualized 48 h post-infiltration using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 880, Oberkochen, Germany). The empty pAN580-GFP construct expressing free GFP (35S::GFP) was used as the control.

2.7. Analysis of TaFAF Expressions in Response to Heat Stress

The RNA-seq data used to analyze TaFAF gene expression under heat stress were processed and analyzed using methods from an independent study, with the dataset having already been uploaded to NCBI (accession number: PRJNA1379895) as part of that study. Briefly, transcriptome sequencing was performed on the Illumina PE150 platform. Clean reads were aligned to the Chinese Spring reference genome (IWGSC RefSeq v1.1) using HISAT2 [27]. Expression levels were normalized using FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads), adjusting for sequencing depth and gene length. Differentially expressed genes were identified using DESeq2, based on raw gene count data, with Fold Change ≥ 2 and FDR < 0.01 as the thresholds for significant expression differences, as previously described [28]. Log2FC was used for comparisons, with larger absolute log2FC and smaller FDR indicating more significant differences.

2.8. Yeast Two-Hybrid Assays

The CDS of TaFAF-1A.1, TaFAF-4B.2, TaFAF-5D.5, TaFAF-2A, and TaFAF-4D.3 were cloned into the pGADT7 vector as prey constructs, while the TaFT1 CDS was inserted into the pGBKT7 vector as the bait. All constructs were co-transformed into the Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain Y2HGold using the lithium acetate method as previously described [22]. Transformed yeast cells were initially selected on SD/-Leu/-Trp medium to confirm co-transformation and subsequently plated on SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade medium to assess protein–protein interactions. Growth on the quadruple dropout medium indicated a positive interaction. The combination of pGBKT7-53 and pGADT7-T was used as the positive control, while empty vector combinations served as negative controls. Primer sequences used in vector constructions are listed in Table S7.

2.9. Split-Luciferase Complementation Imaging Assays

To investigate the physical interactions between TaFT1 and selected TaFAF proteins, the TaFT1 CDS was fused to the C-terminal fragment of luciferase (cLUC), while TaFAF-1A.1, TaFAF-4B.2, and TaFAF-5D.5 were fused to the N-terminal fragment of luciferase (nLUC). The resulting constructs were co-expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves via Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101) infiltration. At 72 h post-infiltration, leaves were sprayed with 1 mM D-luciferin (GOLDBIO) and kept in the dark for 5 min. Luciferase activity was detected using a low-light cooled CCD imaging system (Tanon 5200, Tanon Biotech., Shanghai, China), and signal intensity was used as an indicator of protein–protein interaction. Negative controls included nLUC or cLUC co-expressed with the corresponding empty vector to confirm signal specificity. Primer sequences are listed in Table S7.

2.10. Protein–Protein Interaction Modeling and Structural Analysis

To investigate the protein–protein interactions between TaFT1 and TaFAF-5D.5, TaFAF-4B.2, structural simulations were performed using AlphaFold 3 (https://deepmind.google/science/alphafold/). The protein sequences for TaFT1, TaFAF-5D.5, and TaFAF-4B.2 were obtained from the Chinese Spring reference genome (IWGSC RefSeq v1.1). To visualize the interaction structures, the predicted models were analyzed using ChimeraX 1.9, a molecular visualization tool that enables detailed analysis of protein interactions and structural features [29].

2.11. Haplotype Analysis

The full-length sequences of TaFAF-5D.5 and TaFAF-1A.1 were used to identify SNP variations across 2789 wheat accessions deposited in the Wheat Union Database with default parameters [30]. SNPs were filtered using the criteria of a minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05 and a missing rate < 0.5. Haplotypes were defined based on different combinations of exonic SNPs. Geographic distribution and associations with growth habit (spring or winter wheat) were evaluated using 145 Chinese cultivars from the Chinese wheat mini-core collection [31].

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 26 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), where statistical significance between groups was assessed using the Student’s t-test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For data visualization, GraphPad Prism 8 (https://www.graphpad.com/) was used to generate bar graphs, scatter plots, and other relevant charts to illustrate the results [32]. The data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the FAF Genes in Wheat

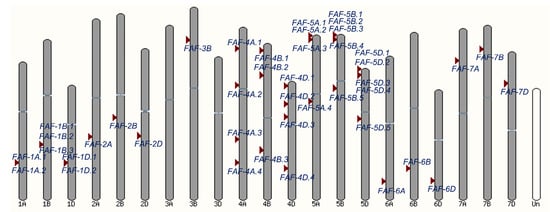

Homology-based searches provide an effective approach for identifying orthologs across plant species. A total of 42 putative TaFAF genes were identified in the hexaploid wheat genome (IWGSC RefSeq v1.1) using a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) search based on the FAF conserved domain (IPR046431) (Table S1). These genes were distributed across all wheat chromosomes except chromosomes 3A and 3D, with each chromosome containing one to five TaFAF genes (Figure 1). Homoeologous group 5 harbored the largest number of genes (14, 33.3%), followed by group 4 (11, 26.2%) and group 1 (6, 14.3%). Each TaFAF was named according to its chromosomal location and physical order (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Physical distribution of 42 TaFAF genes in wheat chromosomes.

Gene structure analysis showed that TaFAF genes ranged from 525 to 2631 bp in length (mean, 1028 bp) and encoded proteins of 169–430 amino acids (mean, 280 aa). The predicted molecular weights ranged from 18.0 to 46.4 kDa, and isoelectric points ranging from 4.87 to 9.88 (Table S2). To assess gene duplication, we compared coding sequences among TaFAF genes and identified 25 homoeologous gene sets across the A, B, and D subgenomes. In addition, 10 tandemly duplicated gene pairs were detected on eight chromosomes (Figure S1). The Ka/Ks ratios of these duplicated gene pairs ranged from 0.39 to 0.85, corresponding to estimated divergence times of 19.7–76.3 million years ago (Table S3). Taken together, these results suggest extensive gene duplication followed by evolutionary divergence of TaFAF genes in the wheat genome, with Ka/Ks ratios indicating that these gene pairs are predominantly subject to purifying selection.

3.2. Phylogenetics and Structure of TaFAF Genes

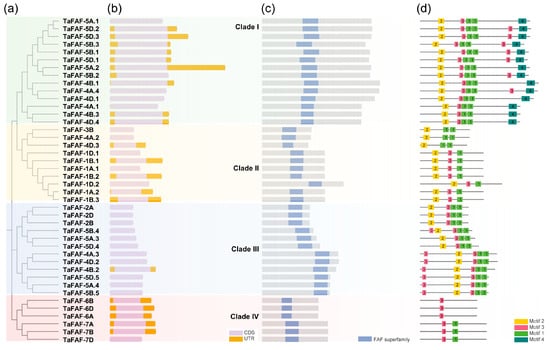

To investigate the evolutionary relationships among TaFAF genes, we constructed a phylogenetic tree based on their full-length amino acid sequences. The 42 TaFAF proteins were classified into four distinct clades, designated TaFAF-I to TaFAF-IV. TaFAF-I represented the largest clade, comprising 14 genes, all located on homoeologous groups 4 and 5. In contrast, TaFAF-IV was the smallest clade, containing six genes exclusively distributed on homoeologous groups 6 and 7 (Figure 2a). Furthermore, our analysis of TaFAF genes in comparison with their homologues from wheat progenitor species revealed that four triple homoeologous TaFAFs were located on chromosome groups five, six, and seven. These genes were more conserved than their orthologs in Aegilops tauschii, Triticum turgidum, and Triticum urartu (Figure S2). Despite substantial variation in gene length, gene structure analysis indicated that all TaFAF genes were highly conserved and consisted of a single exon (Figure 2b). Consistently, all TaFAF proteins contained only one conserved FAF domain (Figure 2c). Motif prediction analysis identified four conserved motifs, each 21–36 amino acids in length, across the TaFAF family (Figure S3). Notably, all TaFAF-I members contained at least four motifs, whereas TaFAF-IV members possessed only one or two motifs (Figure 2d). Together, these phylogenetic, structural, and motif analyses highlight the conserved organization and clade-specific diversification of the TaFAF gene family in wheat.

Figure 2.

Molecular characterization of TaFAF genes and their encoded proteins: (a) Phylogenetic tree of all TaFAF proteins based on amino acid sequences. (b) Gene structures of the 42 TaFAF genes; gene lengths are shown proportionally. (c) Conserved domain composition of TaFAF proteins. (d) Motif identification in TaFAF proteins.

3.3. Identification of the Cis-Regulatory Elements

Cis-regulatory elements recognized by upstream transcription factors play important roles in regulating gene expression. To characterize the cis-regulatory elements of TaFAF genes, 2 kb promoter sequences were analyzed using the PlantCARE web server. Four major categories of cis-regulatory elements were identified: development-related (57.0%), hormone-responsive (19.5%), stress-related (16.2%), and light-responsive (7.3%). Among the development-related elements, the basal promoter elements CAAT-box and TATA-box were the most abundant, with average frequencies of 29 and 17 sites per gene, respectively (Figure 3). Hormone-responsive elements were mainly represented by MYB- and MYC-binding sites, whereas stress-related elements predominantly comprised Stress Response Element (STRE) and ABA-responsive Element (ABRE) core motifs. Light-responsive elements were largely dominated by G-box and AT–TATA-box motifs. Further analysis of these stress-related elements revealed that TaFAF-5A.1, TaFAF-4D.4, TaFAF-4B.2, and TaFAF-5B.5 exhibited the highest enrichment of stress-related cis-regulatory elements, such as STRE, ABRE, and WRKY Response Element (WRE3) (Table S4). The diversity and enrichment of these cis-regulatory elements suggest that TaFAF genes may participate in wheat development, hormone signaling, and responses to environmental stresses.

Figure 3.

Characterization of cis-regulatory elements in the 2 kb promoter sequences of TaFAF genes. The numbers in the boxes indicate the cis-regulatory elements in gene promoters. The histograms show the total number and types of cis-regulatory elements.

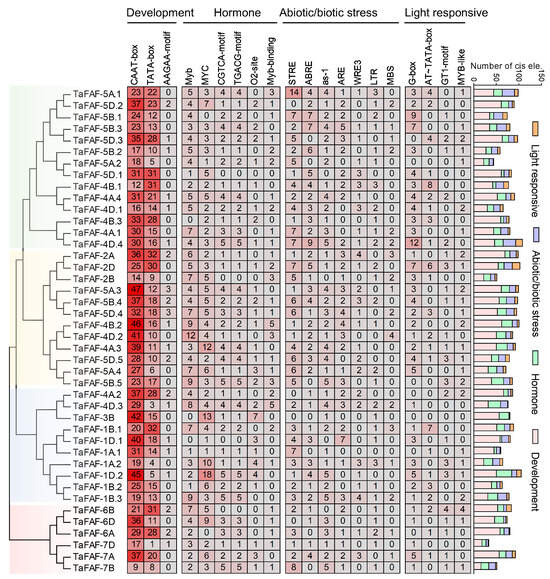

3.4. Expression Patterns and Subcellular Localization of TaFAF Genes

We analyzed the expression patterns of all TaFAF genes using transcriptome data obtained from the expVIP database. Phylogenetically closely related TaFAF genes tended to exhibit similar tissue-specific expression patterns. For example, 19 of the 25 genes in clades I and II were predominantly expressed in roots, whereas most clade III genes showed higher expression in shoots during the vegetative growth stage (Figure 4a). During the reproductive growth stage, the majority of clade I and II genes were highly expressed in anthers and grains, while clade III genes were mainly expressed in leaves and endosperm (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Expression profiling of TaFAF genes: (a) Expression heatmap of 42 TaFAF genes in different wheat tissues at the vegetative stage. (b) Expression heatmap of 42 TaFAF genes in different wheat tissues at the reproductive stage. Data were obtained from the expVIP database. (c) qRT-PCR analysis of eight selected TaFAF genes in five different tissues.

We next examined the tissue-specific expression of eight representative TaFAF genes at the heading stage using qRT-PCR. Two clade I genes (TaFAF-5D.1 and TaFAF-4A.4) and two clade II genes (TaFAF-1A.1 and TaFAF-1B.3) showed relatively high transcript abundance in spikes. In contrast, the clade III genes TaFAF-2B and TaFAF-5D.5 displayed peak expression in leaves, followed by spikes and sheaths (Figure 4c). In addition, TaFAF-6B and TaFAF-7D, both belonging to clade IV, exhibited distinct expression patterns across wheat tissues (Figure 4c). These results suggest that phylogenetic classification is associated with tissue-specific expression patterns of TaFAF genes, which may reflect their functional diversification.

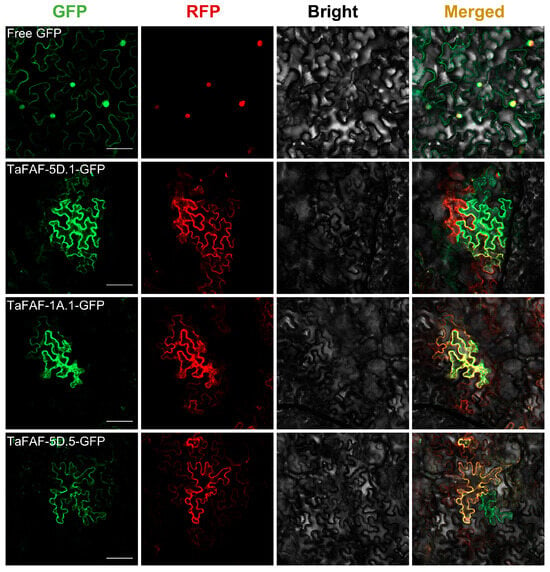

To determine the subcellular localization of TaFAFs, we selected three representative genes (TaFAF-5D.1, TaFAF-1A.1, and TaFAF-5D.5) and fused their coding sequences to GFP. The resulting fusion constructs were transiently co-expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells with an mCherry-tagged cytoplasmic protein under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Fluorescence microscopy showed that the GFP signals were well overlapped with the mCherry signals for all three fusion proteins (Figure 5), indicating that TaFAF-5D.1, TaFAF-1A.1, and TaFAF-5D.5 are localized in the cytoplasm.

Figure 5.

Subcellular localization of TaFAF-5D.1, TaFAF-1A.1 and TaFAF-5D.5 in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. Scale bar = 20 µm.

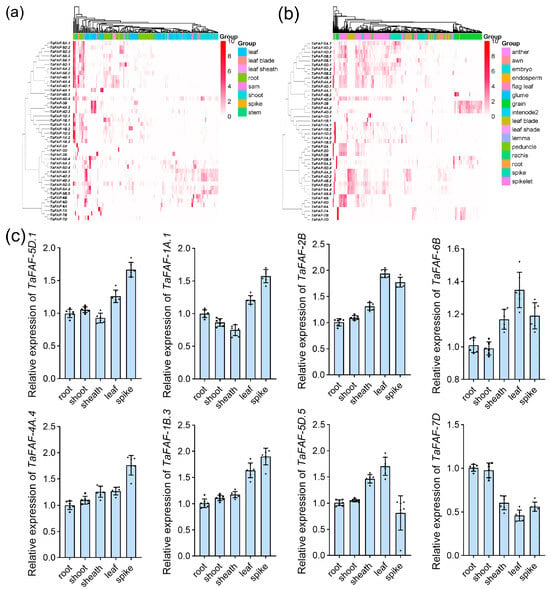

3.5. Expression Characterization of Temperature-Responsive TaFAF Genes

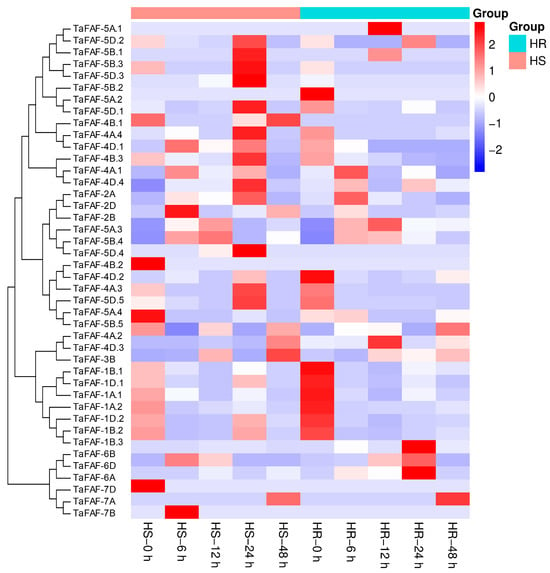

To examine the transcriptional regulation of TaFAF genes in response to heat stress, we analyzed RNA-seq-based expression profiles of 42 TaFAF genes in leaves of the heat-resistant (HR) wheat cultivar Huamai 211 and the heat-susceptible (HS) genotype Chuke 316 subjected to heat stress for four durations (6–48 h). The results showed that seven genes, including TaFAF-1D.2, TaFAF-4A.3, TaFAF-4D.2, TaFAF-4B.2, TaFAF-5D.5, TaFAF-5A.4, and TaFAF-5B.5 were consistently downregulated by heat stress at all time points in Huamai 211. In contrast, these genes were downregulated at only two or three time points in Chuke 316 (Figure 6, Table S5). Additionally, TaFAF-4D.4 and TaFAF-4A.1 were upregulated during early heat exposure in both Huamai 211 and Chuke 316. Moreover, a total of 31 TaFAF genes exhibited undetectable expression, defined as genes with zero or near-zero read counts across all replicates in both cultivars (Figure 6, Table S5). Collectively, these results indicate that TaFAF genes exhibit genotype-dependent and temporally distinct transcriptional responses to heat stress.

Figure 6.

RNA-seq-based temperature-responsive expression profiling of 42 TaFAF genes in the heat-resistant (HR) wheat cultivar Huamai 211 and the heat-susceptible (HS) genotype Chuke 316.

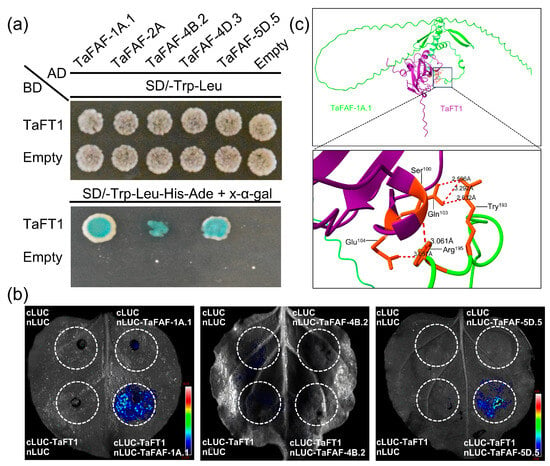

3.6. TaFAFs Interact with the Flowering Regulator TaFT1

TaFT1 functions as a key regulator of flowering time in wheat. To assess potential protein–protein interactions between TaFT1 and TaFAF family members, five representative TaFAFs were selected for Y2H assays. The results showed that TaFAF-1A.1, TaFAF-4B.2, and TaFAF-5D.5 interacted with TaFT1, whereas no interaction was detected for TaFAF-2A or TaFAF-4D.3 (Figure 7a). To validate these interactions in planta, split-luciferase complementation imaging assays were performed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. These assays confirmed interactions between TaFT1 and TaFAF-1A.1 as well as TaFAF-5D.5, but not between TaFT1 and TaFAF-4B.2 (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Validation of interactions between TaFT1 and selected TaFAF proteins: (a) Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay showing interactions between TaFT1 and three TaFAF proteins. Yeast growth on selective media indicates positive interactions. (b) Luciferase complementation imaging (LCI) assay confirming TaFT1–TaFAF interactions in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Luminescence signals indicate protein–protein interactions. (c) AlphaFold-based modeling of the interaction interface between TaFT1 and TaFAF-1A.1.

Structural modeling of the TaFT1–TaFAF-1A.1 and TaFT1–TaFAF-5D.5 complexes indicated potential interaction interfaces, with three residues of TaFT1 (Ser100, Gln103, and Glu104) predicted to form hydrogen bonds with Tyr193 and Arg195 of TaFAF-1A.1 (Figure 7c). Similarly, the modeling of the TaFT1–TaFAF-5D.5 complex suggested that Glu149 of TaFT1 might form hydrogen bonds with Ser209 and Arg211 of TaFAF-5D.5 (Figure S4). These results demonstrate that TaFAF-1A.1 and TaFAF-5D.5 physically interact with TaFT1 in yeast and in planta, and that potential interaction interfaces can be predicted by structural modeling.

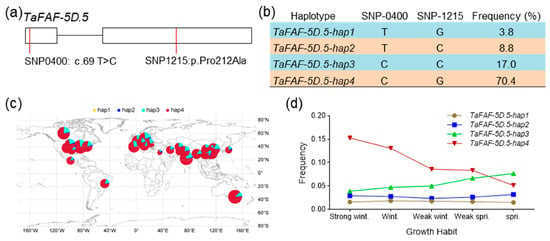

3.7. TaFAF-5D.5 Haplotypes Are Associated with Wheat Growth Habit

To investigate natural variation in TaFT1-interacting TaFAFs, we analyzed sequence polymorphisms of TaFAF-5D.5 using the Wheat Union Database, which catalogs genomic variation from 2789 wheat accessions. This analysis identified two major single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the exonic regions of TaFAF-5D.5 (Table S6). Variant annotation showed that SNP-0400 is located in the 5′ untranslated region, whereas SNP-1215 is a missense variant (Figure 8a). Based on the combinations of both SNPs, four haplotypes were defined, designated TaFAF-5D.5-hap1 to hap4, with frequencies ranging from 3.8% to 70.4% (Figure 8b). Geographic distribution analysis indicated that TaFAF-5D.5-hap4 has been preferentially selected in major global wheat-growing regions (Figure 8c). Haplotype frequencies were also analyzed in 145 landmark cultivars from the Chinese wheat mini-core collection. The favorable haplotype TaFAF-5D.5-hap4 occurred more frequently in winter wheat than in spring wheat, while hap3 was predominantly present in spring wheat (Figure 8d). Expression analysis of 16 wheat accessions from the collection revealed that TaFAF-5D.5 exhibited significantly higher expression levels in hap4 accessions compared to other accessions (p < 0.05, Figure S5). In addition, we analyzed sequence variation in TaFAF-1A.1 and identified four exonic SNPs (Table S6, Figure S6a), which defined one major haplotype (>90% frequency) and three minor haplotypes (Figure S6b). In contrast to TaFAF-5D.5, the haplotype distribution of TaFAF-1A.1 showed no clear association with wheat growth habit (Figure S6c). Together, these results demonstrate a significant association between TaFAF-5D.5 haplotypes, gene expression levels, and wheat growth habit.

Figure 8.

Haplotype analysis of TaFAF-5D.5 in wheat germplasm: (a) Schematic representation of the exon structure of TaFAF-5D.5 showing two SNP variation sites located in the exon region. (b) Four TaFAF-5D.5 haplotypes defined by SNP-0400 and SNP-1215, together with their frequencies in the population. (c) Geographic distribution of the four TaFAF-5D.5 haplotypes across different wheat-growing regions worldwide. (d) Frequency distribution of TaFAF-5D.5 haplotypes in wheat accessions with different growth habits. A total of 145 wheat accessions were analyzed.

4. Discussion

The FAF gene family has emerged as an important group of small regulatory proteins involved in plant developmental control [6,7]. Since their initial identification in Arabidopsis thaliana, FAF genes have been linked to shoot apical meristem maintenance, organ initiation, and developmental timing, positioning them as modulators that fine-tune growth-related signaling pathways [5]. Subsequent studies in tomato further expanded this view by demonstrating that FAF genes can influence developmental transitions relevant to crop improvement [6,7]. However, most existing knowledge derives from dicot species, and the evolutionary expansion, regulatory diversification, and potential functions of FAF genes in monocot crops remain largely unexplored [33]. In this context, wheat represents a particularly informative system because of its hexaploid genome and extensive gene duplication [34]. Our genome-wide analysis identified a markedly expanded FAF gene family in wheat compared with diploid plants, consistent with the well-documented effects of polyploidization on gene family size [22,35]. Although the TaFAF gene family is expanded, these genes retain a highly conserved single-exon structure and a conserved FAF domain. Similar structural conservation in tomato FAF genes suggests that maintaining the basic protein architecture might be important for FAF function [6,7]. At the same time, phylogenetic clustering and motif divergence among wheat FAF genes indicate lineage-specific diversification after duplication events. The presence of diverse cis-regulatory elements in TaFAF promoters, particularly those associated with development, hormone signaling, and stress responses, further suggests that regulatory divergence rather than structural innovation has driven functional differentiation of TaFAF genes in wheat, a pattern commonly observed for regulatory gene families in polyploid crops [36,37].

Beyond evolutionary considerations, previous studies have emphasized that FAF gene function is closely linked to the spatial and temporal regulation of expression. In Arabidopsis, FAF transcripts accumulate in meristematic tissues, whereas tomato FAF genes display stage-specific expression associated with developmental transitions [5,6,7]. Consistent with this framework, the expression patterns observed for TaFAF genes suggest broad regulatory potential across wheat tissues and developmental stages. Rather than indicating direct functional outputs, these expression patterns align with the idea that FAF proteins act as context-dependent modulators whose roles depend on tissue type and developmental status. Subcellular localization has not been extensively characterized for FAF proteins in plant species. The observed cytoplasmic localization and lack of recognizable DNA-binding domains and transcriptional activation motifs suggest that FAF proteins are unlikely to function as classical transcription factors and may instead act as modulatory components within protein complexes [38,39]. Increasing evidence points to the role of small regulatory proteins in abiotic stress responses. Although FAF genes have been less studied in this regard, reports from pepper suggest that FAF-like proteins can influence responses to salt stress [8]. Within this broader context, the heat stress-responsive expression patterns observed for a subset of TaFAF genes indicate that FAF genes might be involved in wheat’s response to heat stress.

One of the most intriguing aspects of TaFAF function emerging from recent studies is the potential interaction of these genes with key developmental regulators. In wheat, TaFT1 is widely recognized as a central integrator of environmental and endogenous cues that coordinate developmental progression [26,40]. Although direct protein–protein interactions between FAF proteins and flowering-related regulators have not been systematically reported, genetic and functional studies in dicot systems have implicated FAF genes in developmental transitions. These observations raise the possibility that FAF proteins may act as modulators of key developmental hubs. The interactions between TaFAF-5D.5 and TaFAF-1A.1 with TaFT1 identified in this study support the conceptual framework. However, a weak interaction between TaFT1 and TaFAF-4B.2 was detected in the Y2H assay, whereas no interaction was observed in the split-luciferase assay. This difference may be attributed to the inherent sensitivity differences between the two methods. The Y2H assay, conducted in yeast cells, is often more sensitive to weak interactions, whereas the split-Luc assay, performed in plant cells, may have lower sensitivity due to variations in expression conditions, protein folding, or cellular context. Rather than implying a direct causal role in flowering regulation, these interactions suggest that FAF proteins may fine-tune TaFT1-associated protein complexes, thereby modulating downstream signaling outputs in a context-dependent manner. Such modulatory interactions are increasingly recognized as important mechanisms for achieving flexible developmental responses [41,42].

From an evolutionary perspective, natural variation within regulatory genes often underlies adaptive traits in crops [43]. Growth habit variation in wheat reflects long-term adaptation to different climatic regimes, and many contributing loci encode regulatory rather than structural proteins [44,45]. The association between TaFAF-5D.5 haplotypes and wheat growth habit aligns with broader observations that subtle allelic variation in modulatory genes can have significant adaptive consequences. Given that wheat growth habit is strongly influenced by population background, such as the distinction between winter and spring types, population structure may confound the observed haplotype–growth habit relationship. Therefore, future studies should consider population structure and relatedness to more accurately assess the relationship between TaFAF-5D.5 haplotypes and growth habit. Our findings also highlight TaFAF-5D.5 as a promising candidate gene associated with both developmental adaptation and heat stress responses in wheat. This gene may represent a promising candidate for further investigation into the genetic basis of developmental adaptation and stress responsiveness in wheat. The functional diversification of the TaFAF gene family in wheat, driven by polyploidization and gene duplication, suggests that these genes play a crucial role in fine-tuning developmental and stress response pathways. Further studies on additional TaFAF genes that show differential expression under heat stress conditions could provide deeper insights into their specific contributions to wheat’s phenotypic plasticity under heat stress, helping to identify potential markers for climate-resilient wheat breeding programs.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, this study highlights the role of the wheat FAF gene family within the broader landscape of plant developmental and stress regulatory networks. By integrating evolutionary, regulatory, and population-level perspectives, our work supports a model in which FAF genes act as conserved yet flexible modulators that have diversified in polyploid wheat primarily through regulatory changes. Rather than redefining the FAF function, our findings extend existing concepts from dicot systems to a major monocot crop and highlight the relevance of FAF genes to traits associated with environmental adaptation. These insights provide a foundation for future functional studies aimed at dissecting the precise molecular roles of individual TaFAF genes. Ultimately, understanding how FAF-mediated modulation contributes to developmental stability and stress resilience may inform strategies for improving wheat performance under increasingly variable climatic conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020221/s1, Figure S1: Homoeologous relationships and duplication events of TaFAF genes. Figure S2: Phylogenetic analysis of TaFAFs and their homoeologous counterparts from Aegilops tauschii, Triticum turgidum, and Triticum urartu. Figure S3: Motif sequences identified in TaFAF proteins. Figure S4: AlphaFold-based modeling of the interaction interface between TaFT1 and Ta-FAF-5D.5. Figure S5: Association analysis of TaFAF-5D.5 expressions and haplotypes in 16 wheat accessions from the Chinese wheat mini-core collection. Figure S6: Haplotype analysis of TaFAF-1A.1 in wheat germplasm. Table S1: List of TaFAF genes and their corresponding gene IDs. Table S2: Molecular and physicochemical properties of the 42 TaFAF genes identified in the wheat genome. Table S3: Molecular characterization of 10 duplicated gene pairs in wheat. Table S4: TaFAF genes with the most enriched stress-related cis-regulatory elements. Table S5: Expression profiles of 42 TaFAF genes in two wheat cultivars under different durations of heat treatment. Table S6: Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified in the TaFAF-5D.5 and TaFAF-1A.1 genes across 2789 wheat accessions. Table S7: Primer sequences used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Z.F.; methodology, J.J.; software, J.J.; validation, Z.H., J.J. and S.W.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, Z.H.; resources, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, J.J.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Z.F.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and Z.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025M784051), the Hubei Province Technology Innovation Program (2024BBB004), and the Hubei Key Laboratory of Waterlogging Disaster and Agricultural Use of Wetland (KFG202508).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC). Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding using a fully annotated reference genome. Science 2018, 361, eaar7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, K.K.; Naik, J.; Barthakur, S.; Chandra, V. High-temperature stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): Unfolding the impacts, tolerance and methods to mitigate the detrimental effects. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 1171–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, K.; Kumar, M.; Singh, V.; Chaudhary, L.; Sharma, R.; Yashveer, S.; Dalal, M.S. Heat stress tolerance indices for identification of the heat tolerant wheat genotypes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Wei, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Si, H. Roles of TCP transcription factors in plant growth and development. Physiol. Plant 2025, 177, e70357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, V.; Brand, L.H.; Guo, Y.-L.; Schmid, M. The FANTASTIC FOUR proteins influence shoot meristem size in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Ai, G.; Ji, K.; Huang, R.; Chen, C.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Cui, L.; Li, G.; Tahira, M.; et al. EARLY FLOWERING is a dominant gain-of-function allele of FANTASTIC FOUR 1/2c that promotes early flowering in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 22, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Tao, J.; Song, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ge, P.; Li, F.; Dong, H.; Gai, W.; Grierson, D.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations of FANTASTIC FOUR gene family for creating early flowering mutants in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 22, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, Y.; Baek, W.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. A pepper RING-finger E3 ligase, CaFIRF1, negatively regulates the high-salt stress response by modulating the stability of CaFAF1. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 1319–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu-Neto, J.B.; Turchetto-Zolet, A.C.; de Oliveira, L.F.V.; Bodanese Zanettini, M.H.; Margis-Pinheiro, M. Heavy metal-associated isoprenylated plant protein (HIPP): Characterization of a family of proteins exclusive to plants. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 1604–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbler, S.M.; Wigge, P.A. Wigge, Temperature sensing in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Y.; Mu, X.-R.; Gao, J.; Lin, H.-X.; Lin, Y. The molecular basis of heat stress responses in plants. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1612–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhad, M.; Kumar, U.; Tomar, V.; Bhati, P.K.; Krishnan, J.N.; Barek, V.; Brestic, M.; Hossain, A. Heat stress in wheat: A global challenge to feed billions in the current era of the changing climate. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1203721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Baranwal, V.K.; Kumar, R.; Sircar, D.; Chauhan, H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of Hsp70, Hsp90, and Hsp100 heat shock protein genes in barley under stress conditions and reproductive development. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2019, 19, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Geng, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, X.; Ni, Z.; Yao, Y.; Xin, M.; et al. Overexpression of wheat ferritin gene TaFER-5B enhances tolerance to heat stress and other abiotic stresses associated with the ROS scavenging. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Cai, X.; Wang, Q.; Dai, S. Heat-responsive photosynthetic and signaling pathways in plants: Insight from proteomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.W.; Bae, Y.; Lee, S.C. Differential role of Capsicum annuum FANTASTIC FOUR-like gene CaFAF1 on drought and salt stress responses. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 199, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, C.; Leroy, T.; Seidel, M.A.; Tondelli, A.; Duchemin, W.; Armisen, D.; Lang, D.; Bustos-Korts, D.; Goué, N.; Balfourier, F.; et al. Tracing the ancestry of modern bread wheats. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrill, P.; Adamski, N.; Uauy, C. Genomics as the key to unlocking the polyploid potential of wheat. New Phytol. 2015, 208, 1008–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Liu, B.; Yao, Y.; Guo, Z.; Jia, H.; Kong, L.; Zhang, A.; Ma, W.; Ni, Z.; Xu, S.; et al. Wheat genomic study for genetic improvement of traits in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 1718–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Gonzalez, R.H.; Borrill, P.; Lang, D.; Harrington, S.A.; Brinton, J.; Venturini, L.; Davey, M.; Jacobs, J.; van Ex, F.; Pasha, A.; et al. The transcriptional landscape of polyploid wheat. Science 2018, 361, eaar6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Yang, D.; Li, L.; Yin, H. Genome-wide identification of the nuclear redox protein gene family revealed its potential role in drought stress tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1562718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, H.; Guo, H.; Zhao, L.; Xie, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhao, S.; Ding, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, C.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of two homeobox families identifies key genes associated with grain-related traits in wheat. Plant Sci. 2023, 336, 111862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Gojobori, T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1986, 3, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, H.; Guo, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gu, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, C.; et al. A gain-of-function mutation at the C-terminus of FT-D1 promotes heading by interacting with 14-3-3A and FDL6 in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, H.; Guo, H.; Zhou, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gu, J.; Zhao, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, L. Identification of the vernalization gene VRN-B1 responsible for heading date variation by QTL mapping using a RIL population in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Ni, Z.; Hu, Z.; Xin, M.; Peng, H.; Yao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Guo, W. SnpHub: An easy-to-set-up web server framework for exploring large-scale genomic variation data in the post-genomic era with applications in wheat. Gigascience 2020, 9, giaa060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Hou, J.; Hao, C.; Wang, L.; Ge, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X. The wheat (T. aestivum) sucrose synthase 2 gene (TaSus2) active in endosperm development is associated with yield traits. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2010, 11, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.L. GraphPad Prism, Data Analysis, and Scientific Graphing. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1997, 37, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zeng, W.; Wang, C.; Xu, D.; Guo, H.; Xiong, H.; Fang, H.; Zhao, L.; Gu, J.; Zhao, S.; et al. Fine mapping of qd1, a dominant gene that regulates stem elongation in bread wheat. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 793572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yao, Y.; Xin, M.; Peng, H.; Ni, Z.; Sun, Q. Shaping polyploid wheat for success: Origins, domestication, and the genetic improvement of agronomic traits. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 536–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ma, G.; Chen, J.; Gichovi, B.; Cao, L.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L. The B3 gene family in Medicago truncatula: Genome-wide identification and the response to salt stres. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yao, Y.; Ye, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Sun, F.; Xi, Y. Genome-wide identification of wheat KNOX gene family and functional characterization of TaKNOX14-D in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, N.; Liu, H.; Ma, B.; Huang, X.; Zhuo, L.; Sun, Y. Roles of the 14-3-3 gene family in cotton flowering. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, N.; Guo, Y.Y.; Bai, Y.; Wu, T.; Yu, T.; Feng, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Comprehensive identification and characterization of simple sequence repeats based on the whole-genome sequences of 14 forest and fruit trees. Forestry Res. 2021, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, L.T. The rice VCS1 is identified as a molecula tool to mark and visualize the vegetative cell of pollen. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, e1924502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Si, X.; Pan, Y.; Guo, M.; Wu, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. TaFT-D1 positively regulates grain weight by acting as a coactivator of TaFDL2 in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2207–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Dong, L.L.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.L.; Yan, H.W. Comprehensive evolutionary analysis of the MAPK gene family from non-seed plants to angiosperm and interaction of PagMAPK3-1 with PagVQ13. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 781, 152554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Shen, C.C.; Li, W.J.; Peng, L.; Hu, M.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhao, X.Q.; Teng, W.; Tong, Y.P.; He, X. TaLBD41 interacts with TaNAC2 to regulate nitrogen uptake and metabolism in response to nitrate availability. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, S.; Song, W.W.; Abdul, M.; Khan, A.; Sun, S.; Zhang, C.S.; Wu, T.T.; Wu, C.X.; Han, T.F. Natural variations of FT family genes in soybean varieties covering a wide range of maturity groups. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Liu, B.; Xie, L.; Wang, K.; Xu, D.; Tian, X.; Xie, L.; Li, L.; Ye, X.; He, Z.; et al. The TaSOC1-TaVRN1 module integrates photoperiod and vernalization signals to regulate wheat flowering. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 22, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Luo, X.; Xu, D.; Tian, X.; Li, L.; Ye, X.; Xia, X.; Li, W.; et al. TaVrt2, an SVP-like gene, cooperates with TaVrn1 to regulate vernalization-induced flowering in wheat. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.