Abstract

Weeds pose a significant threat to crop yields, both in quantitative and qualitative terms. Modern agriculture relies heavily on herbicides; however, their excessive use can lead to negative environmental impacts. As a result, recent research has increasingly focused on Integrated Weed Management (IWM), which employs multiple complementary strategies to control weeds in a holistic manner. Nevertheless, large-scale adoption of this approach requires a solid understanding of the underlying tactics. This systematic review analyses recent studies (2013–2022) on herbicide alternatives for weed control across major cropping systems in the EU-27 and the UK, providing an overview of current knowledge, the extent to which IWM tactics have been investigated, and the main gaps that help define future research priorities. The review relied on the IWMPRAISE framework, which classifies weed control tactics into five pillars (direct control, field and soil management, cultivar choice and crop establishment, diverse cropping systems, and monitoring and evaluation) and used Scopus as a scientific database. The search yielded a total of 666 entries, and the most represented pillars were Direct Control (193), Diverse Cropping System (183), and Field and Soil Management (172). The type of crop most frequently studied was arable crops (450), and the macro-area where the studies were mostly conducted was Southern Europe (268). The tactics with the highest number of entries were Tillage Type and Cultivation Depth (110), Cover Crops (82), and Biological Control (72), while those with the lowest numbers were Seed Vigor (2) and Sowing Depth (2). Overall, this review identifies research gaps and sets priorities to boost IWM adoption, leading policy and funding to expand sustainable weed management across Europe.

1. Introduction

Agriculture must tackle the dual challenge of nourishing a growing global population while preserving ecosystems that are vital for human survival. Weeds represent one of the main threats to food crops and agriculture in general, as they damage yields both quantitatively and qualitatively [1,2]. Byrne and Howell [3] observed that weed competition could lead to reductions in yield by as much as 37% in vineyards, a decrease in the number of clusters per vine by 28%, and a reduction in berry weight by 3%. Numerous studies documented yield reduction attributed to weeds in vegetable crops, e.g., in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica), the presence of ryegrass (Lolium spp.) at a density of 600 plants m−2 within the row resulted in complete loss of production [4]. In the context of arable crops, it has been observed that uncontrolled weed growth can reduce the yield of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. var. saccharifera L.) crop by as much as 90–95% [5,6]. Jain et al. [7] and Pant et al. [8], reported that weed infestation can reduce maize (Zea mays L.) yield by 60–85%. Indeed, weeds compete with crops for essential environmental resources, including space, nutrients, sunlight, and water [9]. They can also produce allelochemicals that disrupt the fundamental physiological processes of crops, thereby inhibiting their growth and development. Additionally, these allelochemicals can affect seed germination, causing delayed crop seedling emergence. On the other hand, in addition to quantitative damage, weeds can cause qualitative damage and a significant reduction in the market value of the product [10]. Therefore, their management is crucial.

Modern agricultural systems, especially in developed countries, are largely characterized by large-scale, intensive, and mechanized farming focused on a few major crops that are heavily reliant on mineral fertilizers and chemical crop protection products [11]. Reasons for the intensive use of herbicides include their cost-effectiveness in weed control, the absence of threshold-based spraying decisions, and the lack of an adequately effective and affordable non-chemical alternative [12]. Nevertheless, excessive use of herbicides can lead to unintended harm to crops, destruction of natural vegetation, and loss of soil biodiversity [13,14,15], environmental contamination [16], and adverse health effects on farmworkers [17] and the general public [18].

In the European Union (EU), the European Green Deal [19,20] presents a challenge for modern agriculture to sustain current crop production levels while reducing the overall use and risk of chemical pesticides by 50% to safeguard the environment and reverse ecosystem degradation.

The European Biodiversity Strategy [21] includes proposals for actions that impact not only the use of plant protection products but also promote the growth of the organic farming sector, conserve and restore ecosystems, enhance the biodiversity of natural resources, and encourage changes in the eating habits of European consumers.

In recent years, research on weed control has generally focused on replacing herbicides with single alternative strategies. Nevertheless, the high reproductive capacity and dispersal ability of certain weed species make individual control tactics insufficient for achieving effective management [22]. Integrating multiple strategies concurrently allows farmers to attack weeds at various life stages, significantly hindering their growth and reproductive success [23]. This highlights the crucial role of Integrated Weed Management (IWM), which shifts from an approach based on the use of a single tactic and consideration of one growing season, to a more holistic approach relying on multiple tactics, that considers more than one cropping season, and focuses on managing weed communities [24]. Effective IWM is not just the use of multiple control actions, but the combination of tools and techniques in ways that truly varies the type and timing of disturbance, and thus acts against adaptation trade-offs caused by weeds [11].

However, to date, IWM is still not widely adopted by farmers for various reasons. Among these reasons is the greater complexity and time required compared to the use of herbicides [25], as well as the potential increase in costs [26]. Indeed, the long-term profitability of IWM remains uncertain for many farmers [27]. Adopting IWM may require specialized equipment and trained personnel, which can be an additional barrier for some farmers [28].

There are also other aspects to consider, such as the lack of immediate visible results for the alternative tactics. Farmers usually cannot afford to evaluate the success of most alternative weed control methods in their own managed fields, due to a lack of access to specific knowledge, costly technologies, or solid set-up of on-farm tests (that normally rely on a single, unreplicated treatment without controls, making it difficult to assess its real effectiveness). On the other hand, researchers conducting on-station field experiments with side-by-side treatment comparisons are more confident in assessing the relative effectiveness of different techniques [29], but they could miss farm-related issues that may affect the applicability and the effect of the tested solutions. Another aspect to consider is the variability of the effects of alternative tactics. In fact, the effectiveness of non-chemical methods can be more variable and less predictable than herbicides, depending on factors such as climate and soil characteristics [25]. Consequently, farmers may perceive IWM as riskier compared to herbicides. Thus, knowledge exchange among stakeholders such as farmers, extension services and researchers, who collaborate within networks, about the available alternative strategies and related experiences on best practices, becomes essential to facilitate the adoption and adaptation of IWM practices in various specific contexts [23,30]. Therefore, from an academic point of view, it is crucial to redefine research priorities, focusing on the evaluation of practical solutions applicable to farmers’ needs and on effectively disseminating knowledge about IWM. To this end, it is necessary to understand the current state of knowledge regarding the weed control techniques underlying IWM. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to make the scientific community aware of the alternative techniques that have been studied more, and those that have been less studied, and therefore call attention to research gaps, in order to better direct further investigations to promote the use of IWM.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review focuses on the current state of art regarding latest scientific publications on alternative weed control methods to herbicide use produced within the 27 countries of the European Union (EU-27) and the UK.

This systematic review relied on the framework of Integrated Weed Management (IWM) [24] recently developed by the IWMPRAISE project [31] which classifies methods into five pillars as direct control, field and soil management, cultivar choice and crop establishment, diverse cropping systems, and monitoring and evaluation, with each pillar encompassing multiple tactics. Compared to [24], this review intentionally excluded tactics based on herbicide use (e.g., pre-emergence herbicides, post-emergence herbicides, patch/band spraying, and pre-harvest herbicide), focusing on alternatives to herbicides. The focus was solely placed on pre-harvest weed control. Overall, this systematic review explored a total of twenty-nine IWM tactics in latest scientific publications. The tactics were evaluated only in the context of major cropping systems such as arable crops, vineyards, olive groves, orchards, field vegetables, and grasslands.

2.1. Processing the Query String for Insertion into the Scientific Database for Each Tactic Assessed

The systematic review followed the protocol outlined by PRISMA (version PRISMA 2020) [32], i.e., the international standard for systematic reviews and meta-analysis in scientific publications. To carry out the online literature search, among the various scientific databases available, Scopus was selected for its extensive coverage of foremost scientific journals, with publications reporting peer-reviewed research, and topics related to IWM. For the development of search criteria to be used on Scopus, each tactic was treated as an individual topic, further subdivided into subcategories reflecting various operation/elements associated with itself in the context of weed control. Table 1 displays an example of subcategories from the topic “Tillage type”.

Table 1.

Subcategories of the tillage type topic.

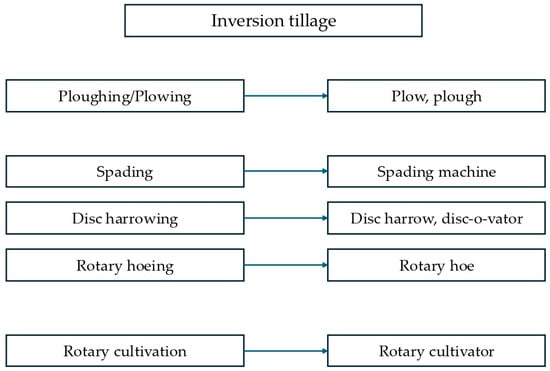

For each identified operation/element of each tactic, a comprehensive list of associated technical methods, operations, and relative technical means together with their synonyms was set and used as keywords. Figure 1 displays an example representing the identified keywords for the inversion tillage subcategory.

Figure 1.

Identification of keywords for the inversion tillage subcategory.

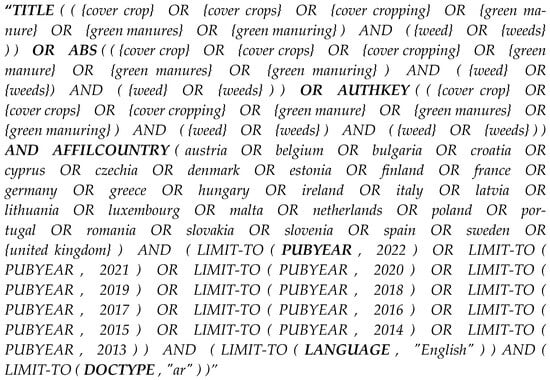

During this phase, it was determined that the “Tillage type” and “Cultivation depth” tactics should be merged into a single tactic, as distinguishing between them for categorization proved to be challenging. Keywords were then inserted into search strings, with one assigned for each tactic, following the Scopus guidelines. These strings were formulated combining keywords relative to the components and declinations of each IWM tactic, together with weed control, representing the performance indicator. Therefore, these elements were searched within article titles, authors’ keywords, and abstracts present in the Scopus database. Restrictions such as geographical coverage, timeframe, language, and publication typology were applied during the search on Scopus. Only papers authored by researchers affiliated with specific countries were considered. These countries included Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. Only papers published in English within the years 2013 and 2022 were included. Moreover, the search focused only on research articles. Therefore, articles were the document type specified in the search string. Figure 2 shows an example of a search string used.

Figure 2.

Search string used for the cover crops tactic.

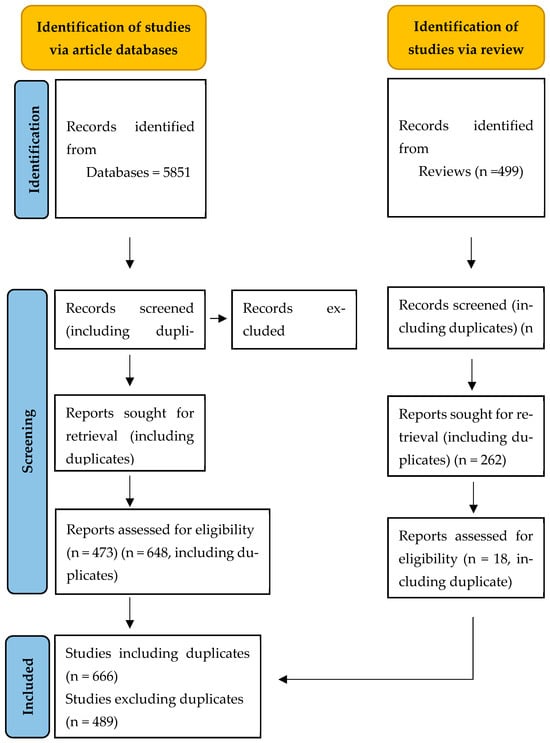

The queries were executed on Scopus on 15 July 2023, and the results were imported into a template on separate MS-Excel files, with one file used for each tactic. The literature search identified a total of 5851 papers of potential interest at this phase, including duplicates selected for different tactics.

2.2. The Screening Process of the Research Articles

The research papers imported were subjected to a screening process for eligibility. In the first screening, the information contained in the title, author keywords, and abstract of each paper were analyzed according to five exclusion criteria. Therefore, papers presenting the following characteristics were excluded from the study: (i) experimental trials conducted outside the European territory (EU-27 + UK) (G was used to identify this type of entry); (ii) papers not reporting any agronomic indicators, such as weed density (number of weed plants or seeds per unit area), weed soil cover (percentage of the unit area covered by weed plants), or weed biomass (dry or fresh weight of the above-ground total biomass of weed plants) (W was used to identify this type of entry); (iii) systemic trials in which it was not possible to isolate the effects of a single tactic from other elements of the cropping system (to be included in the dataset, and each single tactic had to correspond to a single factor or a single treatment) (S was used to identify this type of entry); (iv) papers not reporting findings from an agricultural field experiment (experiments carried out in greenhouses were retained only if they were conducted on soil, whereas those performed on turfgrass or forest were not included) (F was used to identify this type of entry); and (v) off-topic papers (O was used to identify this type of entry). After the first initial screening, 4343 documents were rejected, while 1508 advanced to the next screening phase. In the second screening process, whenever possible, full-text PDFs of the papers were retrieved from the web and thoroughly read to verify eligibility, thus leading to their inclusion in the dataset. Table 2 shows examples of papers excluded during the screening process for each eligibility criteria adopted.

Table 2.

The exclusion criteria and related examples of papers excluded during the screening process.

For each paper that passed the second screening, relevant information about the tactic was extracted, including the corresponding IWM pillar and specific tactic it belongs to, and its description. Details were also gathered about the country where the study took place, subsequently reporting for each the corresponding European macro-area [48], the type of crop involved in the trial, and the type and description of the reference system with which the tactic was compared. The types of reference systems were classified into “no-herbicide” and “herbicide”, which represent the categories of greatest interest for the purposes of the review, and into “others”. The latter category may include untreated or weed-free reference systems. Additionally, for each manuscript, the authors, title, year of publication, Digital Object Identifier (DOI), and Scopus web link (Uniform Resource Locator—URL) were documented. These extracted data were transferred into an MS-Excel template to create the final dataset. In case a single paper was linked to multiple IWM tactics, duplicate entries for the same paper were maintained in the database under different IWM tactics. If the experiment was conducted in multiple eligible countries, the entry for that paper was reported as many times as the number of countries involved. The latter rule was applied also for experiments that involved more than one crop typology, thus reporting the entry as many times as the number of the additional crop types involved, with the exception of papers where no specific reference to one crop type was given (e.g., papers where biological control products were tested against weed plants that can be present in several cropping systems), for which the attribute “MULTIPLE” was used. If the experiment documented in the paper involved multiple reference systems, only one entry was kept, prioritizing, in this order, herbicide-based systems, untreated systems, and weedy control. At the end of this phase, 473 papers were selected for inclusion in the review (648 papers in total, including duplicates).

2.3. Search for Any Missing Articles Within Review Papers

To ensure we collected all available research articles for each tactic, we also examined review papers related to each tactic, checking their references for any articles that might have been missed. For each tactic, the same search strings employed for the research articles as previously described were used, and the document type was specified as review paper.

The queries relating to review papers were executed on Scopus on 9 May 2024. Also, in this case, the results were imported into a template on separate MS-Excel files, with one file for each tactic. A total of 499 review papers of potential interest were collected at this point, including duplicates for the different tactics. The title, abstract, and keywords of the reviews collected for each tactic were screened to verify eligibility according to the criteria O, G, F. From the review papers that passed to the next phase, all references were collected and then inserted into a single file for each tactic. By the end of this phase, a total of 4300 entries had been identified, including duplicates. The papers collected for each tactic underwent an initial screening, using the publication year (2013–2022) as the inclusion criteria. During the same screening process, duplicates present within the same tactic were also excluded. The papers that passed this screening were compared with the entries obtained from the queries executed on 15 July 2023, to exclude any duplicates. Therefore, for each tactic, the papers sourced from the review paper references were compared with the full dataset. At this point, 262 potential papers were identified. The information contained in the title, author keywords, and abstract of each identified paper were analyzed in terms of the exclusion criteria W, S, F, G, O. Selected papers that were not directly relevant to the tactic they were grouped under but were more applicable to others were moved to the collections of more appropriate tactics. For each paper that passed the second screening, relevant information was extracted as described above. At this point, a total of 16 entries (18 entries including duplicates) were included, and data was added to the previously created dataset. Therefore, at the end of the process, considering both the screening of the literature related to scientific articles and that of the references from scientific reviews on IWM tactics, a final dataset was obtained, including 489 entries without duplicates and 666 entries including duplicates, across the IWM tactics considered (Table 3). The final dataset is available in the Zenodo open access repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17672318, accessed on 11 November 2025).

Table 3.

Alternative weed control tactics encompassed within the five IWM pillars in the systematic review.

To analyze the temporal trend of entries over the period 2013–2022, a second-degree polynomial regression was performed, with the year acting as the independent variable and the number of entries as the dependent variable. The generic function of the model is expressed by (1):

where a is the intercept, b the linear coefficient (slope), and c the quadratic coefficient (curvature).

Figure 3 shows the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [32] for the systematic review process.

Figure 3.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the systematic review process, including the identification of entries through scientific article databases and through the screening of the reviews’ references related to IWM tactics.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Considerations on the Dataset

As highlighted by recent literature reviews [24,49,50], in recent years, the growing attention to sustainable agricultural practices has fostered the development of Integrated Weed Management (IWM) strategies aimed at reducing dependence on chemical herbicides and promoting more ecological and multifactorial approaches to weed control. Within this context, the present study analyses the evolution of publications over the last decade to identify the main trends and research areas related to alternative weed management methods.

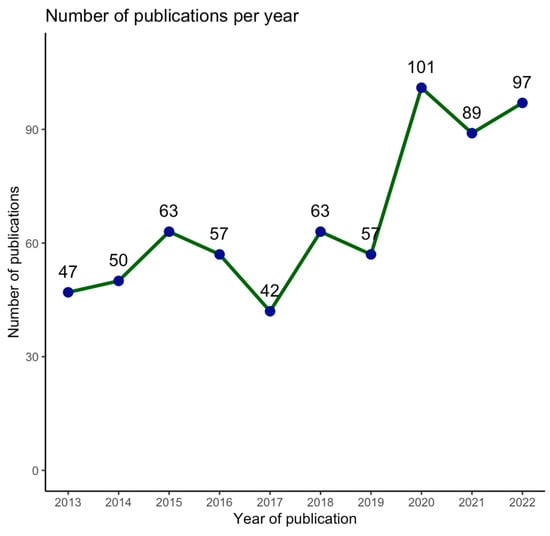

Considering the general trend of publications per year, Figure 4 shows that between 2013 and 2022, there was, on average, a steady level of research interest in alternative methods to herbicides for weed management. Notably, until 2019, the average number of publications per year was around 50, whereas from 2020 onwards this trend showed a significant increase, reaching an average of about 90 publications per year (approximately +45%).

Figure 4.

Number of publications per year included in the dataset, published between 2013 and 2022, on Integrated Weed Management solutions tested in in the EU-27 and the UK.

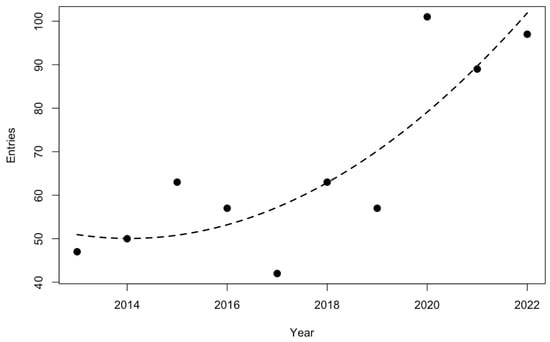

A second-degree polynomial regression was also performed to describe the temporal trend in entries between 2013 and 2022 (Figure 5). The model was significant (p = 0.0097) with multiple R2 = 0.734 (R2 adjusted = 0.657). The pattern shows a non-linear dynamic, with an initial growth phase, a central decrease, and a subsequent increase in the final years of the period analyzed. Overall, a generally increasing trend in entries can be observed over the study period.

Figure 5.

Non-linear second-degree polynomial regression curve describing the temporal trend of entries between 2013 and 2022.

This growing interest in recent years highlights the increasing need to develop alternative strategies to the use of herbicides, which is in line with the European Union’s policy and the Farm to Fork Strategy, which aims to reduce the use and risk of chemical pesticides by 50% by 2030 [21]. This increasing trend suggests an increasing scientific and societal awareness of the need for sustainable weed management approaches.

3.2. The Number of Observations in the Five Pillars of Integrated Weed Management

The analysis of publications distribution within Pillars (Table 4) shows that research has primarily focused on two areas: direct control (28.98%) and diverse cropping systems (27.48%), which together account for more than half of the total publications. Field and soil management (25.83%) also represents a substantial share, highlighting the importance of integrated agronomic practices in reducing herbicide dependence. Conversely, cultivar choice and crop establishment (10.21%) and monitoring and evaluation (7.51%) appear to be less investigated. Direct control tactics are the most extensively studied, likely because they represent the first and most immediate option for weed management, particularly in organic farming systems [51,52]. Moreover, research in this area tends to produce tangible and scientifically robust results within a relatively short timeframe. Indeed, findings from studies on direct control are generally easier to interpret, and the transfer of knowledge to farmers is often highly effective. However, even if direct control remains the pillar with the higher score, it is remarkable that other pillars, mostly focused on a more comprehensive approaches like diverse cropping systems and field and soil management, are progressively gaining ground. Regarding the diverse cropping system pillar, it showed slightly lower values, highlighting a growing scientific and practical interest in crop diversification as a sustainable weed management strategy. Diversification practices such as crop rotation, intercropping, and cover cropping are increasingly recognized for their long-term benefits in reducing weed pressure and enhancing agroecosystem resilience [53,54,55,56]. However, the implementation of these systems requires a solid technical knowledge base, appropriate machinery, and, in some cases, greater labor input, which may limit their immediate adoption compared to direct control tactics. Nonetheless, the integration of agroecological practices to effectively harness ecosystem services, also driven by European policy incentives, has, in recent years, intensified research efforts in this field.

Table 4.

Number of observations per pillar.

The field and soil management pillar obtained results comparable to the two most extensively investigated pillars and includes a set of practices and strategies that often influence weed dynamics indirectly. In general, these strategies affect the chemical and physical properties of the soil, thereby influencing weed seed germination, crop establishment, and overall productivity. The effect on weeds primarily results from the creation of soil conditions that are unfavorable for their emergence and development, while promoting crop growth. This pillar encompasses agronomic strategies such as conservation tillage practices (e.g., minimum tillage, no tillage, strip-tillage), which in the long term enhance soil structure, water retention, nutrient cycling, and consequently the sustainability and resilience of cropping systems. Field and soil management has attracted growing research interest, as soil management is fundamental to many agronomic and environmental processes that interact with weed dynamics, which is an approach that is fully consistent with the principles of IWM [57,58,59]. For practitioners, field and soil management represents a set of practices that are often already part of routine farm operations and can be further integrated or optimized without major machinery investments or radical system changes. This makes this area of research particularly relevant, and the associated practices suitable and feasible, emphasizing their importance within sustainable IWM systems.

Regarding the cultivar choice and crop establishment pillar, the results were significantly lower compared to the previously discussed pillars, indicating a reduced level of research focus in this area. Nevertheless, the current literature highlights the substantial potential of these practices for effective weed management. Strategies such as selecting varieties that rapidly accumulate biomass, achieve early canopy closure, or exhibit allelopathic effects, have shown promising results in suppressing weeds [60,61]. Despite this demonstrated potential, research and adoption of these approaches remain relatively limited. This is partly due to the limited availability of locally oriented, context-specific breeding research and programs, which would be essential to adapt cultivar selection to regional or even sub-regional pedoclimatic conditions. Moreover, from a strictly scientific perspective, these strategies are not often investigated within the framework of IWM, but rather with a primary focus on crop agronomic performance. However, interest in this field is expected to increase, particularly within broader agroecological research frameworks that emphasize resource-use efficiency and reduced dependence on direct control measures. In particular, the upgrowing bio-breeding programs established to select in organic farming conditions for the organic farming crop sectors are enhancing the selection of crop genotypes adapted to herbicide-free (organic) management, thus highlighting crop genotype traits related to competitiveness against weeds [62].

The monitoring and evaluation pillar emerged as the least investigated among the five, suggesting that the main limitation lies not in technological knowledge itself, but rather in its practical implementation and technology transfer. This concerns the use of decision support systems (DSSs), scouting tools, and sensing technologies such as remote and proximal sensing, which are designed to detect and quantify weed populations. Part of the challenge is that current research efforts often lack comparative data with reference systems (i.e., systems not based on monitoring systems), while the investment required to develop DSS platforms and acquire advanced sensors remains too high for practitioners. Moreover, these technologies are often complex and demand technical support and a high level of expertise, which limits their widespread adoption [63]. From a research perspective, although considerable progress is being made in the field of precision agriculture, these technologies are still typically considered auxiliary tools rather than core components of weed management strategies. Nonetheless, the increasing availability of highly sensitive sensors, machine learning algorithms, and open-access spatial datasets is expected to accelerate research efforts in this field [64,65,66,67]. In the near future, the integration of DSSs and proximal sensing systems will represent a crucial step for IWM, improving the timeliness of interventions, and enhancing the efficiency of resource use within sustainable cropping systems.

In conclusion, although direct control methods remain central to IWM strategies, future progress will rely on the development of more integrated systems, from both an agroecological and technological perspective, while enhancing the local applicability and scalability of management practices. Building increasingly adaptive approaches will be key to achieving more sustainable and herbicide-free weed management processes.

Considering the distribution of the pillars across different European regions (Central and Eastern, Northern, Southern, and Western), as shown in Table 5, the most represented area is Southern Europe, accounting for 40.24% of all entries, with the largest sharecoming from publications focused on direct control (15.17% of the total entries included in the review). This result identifies Southern Europe as a research hotspot, given that it is the region most affected by climate change [68] and therefore requires specific studies to address its impacts also from a weed management perspective. Moreover, this area is characterized by mild climatic conditions, especially in the coldest season, which might have favored high weed biodiversity, which might be challenging to manage [69,70]. The wide range of crops, the climatic variability and the pedoclimatic diversity typical of Southern Europe have likely also contributed to the high proportion of publications dealing with direct control practices as an adaptive response to agronomic emergencies.

Table 5.

Number of observations per pillar in the different macro-areas and for the different crop types.

Western Europe showed lower results, accounting for 26.13% of the total entries, indicating a central role in studying IWM practices at the EU level and highlighting the higher percentage observed for the pillar diverse cropping systems (11.11%). This result suggests increasing attention in countries with large agricultural areas, such as France and Germany, towards diversification practices, showing a greater predisposition of practitioners to test agroecological solutions, which can also be attributed to the support provided by the EU-CAP (European Union-Common Agricultural Policy) and national policy strategies [24,71,72]. Moreover, in this area, issues related to intensive agriculture, such as soil degradation, biodiversity loss, and water pollution, have led to the adoption of more environmentally friendly solutions [71,73].

In Central and Eastern Europe, entries accounted for 20.27% of the total, representing a relevant agricultural area. Although none of the pillars appeared to be more extensively investigated, the absence of entries for the monitoring and evaluation pillar is particularly relevant. Although Northern Europe accounted for significantly lower overall results (11.56%), a similar trend was observed, with no entries recorded for the monitoring and evaluation pillar. In Central and Eastern Europe, this could be linked to a more recent transition towards integrated and sustainable farming systems, together with limited investment in monitoring infrastructures and digital tools [74,75,76]. In Northern Europe, on the other hand, the lack of entries within the IWM monitoring and evaluation pillar likely reflects that such tools are disseminated via national IPM advisory platforms or technology-oriented research streams rather than framed as IWM-specific monitoring studies [77].

The analysis by crop type revealed an uneven distribution of entries, highlighting a predominance of arable crops (67.57%) followed by field vegetable crops (13.81%), while perennial and extensive systems such as orchards, vineyards, olive trees, and grasslands were less represented (Table 4). This pattern confirms that IWM research in Europe remains mainly focused on herbaceous, intensive systems where weed pressure and management complexity are higher, reflecting their strategic importance at the extensive scale of European agriculture, in terms of land coverage, contribution to food and feed supply, and concentration of agronomic inputs, which in turn attracts the bulk of IWM innovation and experimentation [24,78,79].

Within arable systems, the largest contributions to the overall dataset came from diverse cropping systems (20.72%) and field and soil management (19.82%), which together account for about 40% of all entries. This pattern indicates that, at the European scale, IWM efforts are oriented toward system-level strategies that prioritize prevention and resilience over purely reactive interventions [24,80]. Nonetheless, direct control contributed 11.41%, showing that tactical measures remain important in arable crops, particularly for summer crops, where timely interventions are often required [81]. Overall, the evidence points to a growing shift toward the agroecological redesign of weed management, with reduced reliance on external inputs and lower soil disturbance [82]. The only other well represented crop type was field vegetable crops. In these systems, the main contributions fell under direct control (5.41%), followed by diverse cropping systems (3.45%) and field and soil management (3.30%). This distribution reflects the high operational intensity associated with short crop cycles, where direct control predominates due to the need for timely interventions [83,84]. Notably, the relatively high shares within the pillars of diverse cropping systems and field and soil management indicate growing interest in diversification practices, such as living/dead mulches and stale seedbeds, to suppress weeds while supporting soil function [83,85].

Field vegetables are likely underrepresented because they occupy less area and attract less funding than arable systems, while their high heterogeneity, short cycles, and operational urgency favor time-critical direct control over long, monitored experiments [83,84].

Other crop types such as orchards, vineyards, olive trees, and permanent grasslands appear marginal, probably due to the following structural reasons: (i) they cover smaller agricultural areas than arable and vegetables, resulting in less research funding, and (ii) weed management is often related to routine mechanical/cultural practices such as direct control or green manuring, and therefore few publications are framed within the IWM context. Other crop types such as orchards, vineyards, olive trees, and permanent grasslands appear marginal mainly for structural reasons: (i) compared with arable and vegetable systems, they often cover smaller areas and attract more limited, crop-specific funding, and (ii) weed management is frequently embedded in routine mechanical/cultural practices (e.g., mowing/tillage, living or dead mulches/green manuring), so fewer studies are explicitly framed as IWM [86,87,88]. The multiple category accounted for 8.71% of entries and was dominated by direct control (8.56%), while the representation in the other pillars was negligible. Hence, entries reported as “MULTIPLE” primarily test the immediate efficacy of direct control tactics across different crop contexts. Lastly, the representation of the monitoring and evaluation pillar across crop types was negligible among the papers included in this study (i.e., those that met our eligibility criteria), suggesting that DSSs, sensing, and scouting remain underreported within IWM. This underrepresentation largely reflects methodological constraints: to qualify under our criteria, studies must deliver quantitative weed metrics (e.g., density, biomass, cover, seed bank) benchmarked against a reference system and collected, ideally, over multiple seasons, with robust field validation (i.e., comparing sensor outputs with actual field measurements) and standardized protocols across heterogeneous fields. These requirements raise costs and logistical complexity, thereby reducing the number of monitoring-oriented studies captured [81].

The reference systems used as benchmarks for assessing the innovative weed control tactics were based on the use of chemical herbicides, in a range between 9.84 and 17.44% of the entries within each IWM pillar (Table 6). Benchmarks for alternatives to chemical weed control were instead more variably represented in the dataset, with the field and soil management pillar showing the highest concentration (~38% of the pillar entries) and cultivar choice and crop establishment showing the lowest (~3%). For the field and soil management pillar, in many cases the reference system was based on farmer standard mechanical weeding, against which the alternative systems were tested and compared. Nevertheless, the majority of the entries of the datasets (~45–87% of each pillar) report on studies conducted against no reference systems, or the reference system was simply not explicitly reported.

Table 6.

Number of observations per pillar with the reference system “Herbicide”, “No-herbicide”, or “Others”.

3.3. Number of Observations per Tactic in Each Pillar

3.3.1. Pillar: Direct Control

Within the direct control pillar, the most investigated tactics are mechanical weeding and biological control, accounting for 33.68% and 37.31% of the entries in this pillar, respectively (Table 7).

Table 7.

Distribution of the number of entries per tactic of the direct control pillar, along with the corresponding counts for different crop types and macro-areas.

The result obtained with mechanical weeding can be explained by the practical relevance this weed management technique holds for farmers [24,89]. Moreover, the continuous technological development in agriculture contributes to encouraging research and experimentation in mechanical weed control. This method is in fact closely linked to the strong wave of technological innovation in areas such as sensors, autonomous navigation systems, and the development of smart actuators. These advancements make mechanical control increasingly sophisticated, with the goal of providing more effective and precise tools that reduce crop damage and promote greater sustainability through lower energy consumption [90,91].

The outcomes achieved with biological control confirm the considerable interest this technique arouses within experimental research. The use of biological control, i.e., “the use of an agent, a complex of agents, or biological processes to bring about weed suppression” [92], as an alternative to chemical methods can bring several benefits, such as reduced contamination of soil, water, and food, improved user safety, and a low risk of resistance development in weeds. Biological control can also contribute to biodiversity conservation. Bioherbicides, for instance, especially those based on fungi, often show high specificity toward the target weed species, selectively attacking certain weeds without harming crops or other plants or organisms of interest [93].

Following mechanical weeding and biological control, thermal weeding accounts for 11.92% of the entries within this pillar. Although thermal weeding offers notable advantages, such as reduced soil disturbance, the comparatively lower number of studies, relative to the two aforementioned techniques, may be attributed to its potentially high operational costs (as in the case of flame weeding) and its environmental impact associated with energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. In this context, advances in precision agriculture, through the development of increasingly efficient site-specific control systems, could play a crucial role in improving the energy and environmental sustainability of thermal weed control technologies [94].

Mowing and hand weeding show the lowest values, at 8.29% and 8.81%, respectively. For hand weeding, this low value is easily explained by the fact that it is a very costly technique in terms of time, labor, and economic expenses, which is an aspect to be considered in light of the growing problem of labor shortages [90]. Mowing, on the other hand, despite bringing significant environmental benefits such as soil conservation, may also present disadvantages compared to tillage, such as requiring multiple interventions during the season, which could potentially make it less attractive for farmers and, consequently, also in experimental research [95].

Regarding crop type, the mechanical weeding technique is more frequently tested in the context of arable crops. This may be due to the fact that it represents one of the few available solutions that farmers can rely on for weed control in this type of crop [96]. Biological control, on the other hand, obtained a particularly high percentage under the “Multiple” category. This category refers to entries in which the experimental trial does not concern a specific crop type but rather tests the solution on weeds potentially present in different crop types. This result may be explained by the fact that, in biological control studies (especially with pathogens, fungi, bacteria, and bioherbicides), the main interest lies in assessing how effective the agent is against the target weed species, evaluating the effect of different concentrations or formulations in order to establish the extent of its phytotoxic effect. This may therefore be due to the fact that much of the research is still at the proof-of-concept stage, where the question is whether the agent works, rather than at the stage of transferring protocols for practical application in weed control [97]. For thermal weeding, the entries concerned field vegetables (6.22%) and arable crops (4.66%). The slightly higher percentage for field vegetables may be due to the greater profitability of these crops compared to arable types, which more strongly justifies the costs involved and thus makes the technique more easily transferable from the experimental to the practical context [98]. In mowing, the entries mainly fall under the orchard category, probably because mowing is commonly used for managing spontaneous vegetation and/or cover crops in the inter-row, with these strategies being increasingly adopted for soil conservation [99,100,101]. Arables showed a somewhat lower value compared to orchards, probably because they are more sensitive to weed competition, and thus experiments more often rely on other techniques, such as mechanical weeding. Hand weeding showed similar results for both arable and field vegetable crops.

In general, within the pillar, most entries fall into the categories of arable crops and field vegetables, while in between, there are the “multiple” entries, which are almost entirely derived from biological weed control. The overall result obtained in terms of arable and field vegetable crops is probably linked to their sensitivity to weeds, their importance as food sources, and their profitability, especially for vegetables [102,103].

In terms of geographical area, most entries for the different tactics concern experimental trials conducted in Southern Europe. In Southern Europe, there is a high incidence of arable and vegetable crops that can experience strong weed pressure in the early stages, requiring immediate and effective interventions [104]. Particularly for vegetables, there is also a high added value per unit of area, which makes the use, and therefore the experimentation, of costly or complex practices, from biological to thermal control, economically more justified. In areas such as Northern and Central Europe, large-scale arable land tends to prevail, which makes the application of these types of tactics less manageable and sustainable. Here, research focuses more on preventive methods that are better suited for large-scale application.

3.3.2. Pillar: Field and Soil Management

In the pillar field and soil management, the tactic with the highest number of entries is tillage type and cultivation depth, accounting for 63.95% of the entries within the entire pillar (Table 8).

Table 8.

Distribution of the number of entries per tactic of the field and soil management pillar, along with the corresponding counts for different crop types and macro-areas.

As noted for the tactic mechanical weeding in the direct control pillar, this is probably due to the practical relevance these strategies have for farmers [24]. Indeed, this tactic includes primary tillage operations, which are considered one of the most important solutions for weed control, as they affect perennial weeds as well as seed distribution in the soil, preventing germination, in addition to secondary tillage operations [105,106]. The type and depth of tillage, whether conventional, reduced, or no tillage, significantly influence weed community density and composition [59,79]. However, while this strategy can reduce reliance on chemical inputs, it may also lead to further soil degradation or increased fuel consumption [107]. For this reason, research activity aims to bring improvements by testing machinery and different operational methods across various pedoclimatic contexts, in order to enhance efficiency as well as environmental and economic sustainability.

After tillage type and cultivation depth, the following tactic is dead mulching, accounting for 10.47% of the entries within the pillar. The strategy of dead mulch for weed control has long been studied, as it represents one of the few tools that integrates with, and in some cases replaces, tillage practices, both in organic systems and in no-tillage systems. Its effectiveness depends on the thickness of the mulch applied, its penetrability, and its persistence, which in turn relates to its resistance to degradation and weather conditions [108]. Experimental activities are therefore still being carried out to evaluate different aspects, such as materials and thicknesses, in order to obtain a resource that is effective, environmentally and economically sustainable, and that does not inhibit the establishment of the crop itself.

Stubble management accounts for 7.56% of the entries within the entire pillar. This strategy affects seed return to the soil, thereby influencing the weed seed bank [24,79]. Research continues to evaluate stubble management techniques, comparing chemical solutions with mechanical ones, including those based on conservation tillage strategies and the use of cover crops, in order to reduce the seed bank while ensuring the most sustainable implementation of the practice.

There are relatively few entries for the tactics liming (4.65%), nutrient placement (4.07%), and water management (3.49%). This could be due to the need for long-term trials and evaluation systems that are costly in terms of both equipment and time [109,110,111,112]. To increase the number of studies, it could be useful to direct future research funding toward these areas. The results also show that most of the techniques have been evaluated in arable crops (76.74%). It is important to highlight that the tactic tillage type and cultivation depth within the arable crops category (56.40%) contributes the most to this percentage, due to the relevance of primary and secondary tillage as a strategic resource for weed control in arable systems. Other techniques contribute less, with percentages ranging from 1.16% to 7.56%.

The category of field vegetables (12.79%) is mainly represented by the tactic dead mulch (6.98%), which is an important reference for weed control and easier to sustain in these crops given their higher added value compared to arable crops, where instead the contribution of dead mulch is lower (1.16%). The crop types orchards (4.07%), vineyards (3.49%), and olive trees (1.16%) show lower percentages, as do permanent grasslands (1.74%). For the pillar field and soil management, most of the entries concern experimental trials conducted in Southern Europe (37.21%) and Central and Eastern Europe (29.07%), while Northern and Western Europe show lower percentages of 16.28% and 17.44%, respectively.

3.3.3. Pillar: Cultivar Choice and Crop Establishment

Among the 68 entries selected for this pillar, 54% dealt with the tactic of cultivar choice, whereas sowing date was the second most represented one, accounting for 20.59% of total pillar entries (Table 9).

Table 9.

Distribution of the number of entries per tactic of the cultivar choice and crop establishment pillar, along with the corresponding counts for different crop types and macro-areas.

Very few entries were about seed vigor and sowing depth. This evidence may suggest that most of the research on IWM focused on sown crop management aspects more related to post-germination periods. High crop seed vigor, obtained, e.g., by seed priming or bioactivation, can lead to faster crop seed germination and bigger cotyledonal tissues and plantlets, thus contributing to avoid or reduce early competition with weed plantlets [113,114]. One may think that this tactic is senseful for small seed crops and slow early growth, such as some field vegetables (e.g., carrot), but in actuality the tactic was discussed by only one paper reporting on arable crops (specifically on meadow fescue). The same applies for sowing depth, which is a tactic aiming at giving an early advantage to the crop, usually characterized by low competitiveness with weeds at early stages (e.g., cotyledonal stage, first leaves stage), by placing the crop seed shallower than the standard deposition technique, consistently with seed physiology and dimensions [115]. Cultivar choice is gaining more peace within the pillar, thus unraveling an increasing importance given to competitiveness against weeds in many genetic development programs, embracing not only arable crops (i.e., the most represented group in our dataset, with 41% of the entries in the pillar) but also field vegetables (10%) and, at a minor extent, orchards (only one entry). We argue that weed competitiveness is a crop trait gaining attention especially in organic farming conditions, where crop robustness is a pre-requisite for an healthy crop development due to the banning of herbicide use, which is, conversely, very effective in keeping weeds under control in conventional agriculture conditions, regardless of the ability of the crop genotype in competing with weeds [116,117,118]. This evidence is extensively proven by the absence of weed competitiveness among the target traits in many crop breeding programs conducted in and for conventional farming [119,120]. Sowing date regulation could be an effective tactic to avoid crop-weed competition but requires in-depth knowledge of the weed community composition and the availability of alternative crop genotypes, and is able to be established during significantly different periods (e.g., early fall, late winter) to escape from the flashes of germination of most competitive weeds. Overall, it is a tactic that is not easy to transfer to real farm conditions, where the decision on the sowing date is usually determined by a number of uncontrolled factors, such as weather and soil conditions, crop seed, labor, and machinery availability. Furthermore, the uncertainty about weather trends and the fuzzier seasonal patterns of air temperatures and precipitations often make this tactic ineffective or inapplicable [42,121]. Seeding pattern and seeding rates, which in this dataset are equally represented (10% each) with combined scores that are the same as sowing date, can be considered more flexible and applicable tactics. Major options considered in studies conducted on seed pattern range across narrower or wider inter-row space for row crops (e.g., cereals and pulses), to broadcast or strip sowing. In any case, the adjustments of the sowing technique aim to increase crop plant density (to reduce ecological niches accessible to weed plants, e.g., for spinach [122]) or to allow inter-row cultivation (e.g., for chickpea [123] or lentils [124]) for post-emergence direct control of weeds. For sowing rate, the aim of increasing or decreasing the standard rate is to emphasize plant traits related to competitiveness against weeds [122,125,126,127]. In certain crops (e.g., spring barley [126]), a reduced crop density can lead to bigger plants, with higher leaf area or higher number of secondary stems, thereby enhancing soil coverage and, in some cases, potentially reducing or delaying weed growth. In other cases, where crop plasticity is rather low, higher seed or plant density is essential to subtract space from weed availability (e.g., chickpea [123] or spinach [122]). In this case, special attention should be paid to intra-species plant–plant competition, shading and diseases, that can be all reduced by fine-tuning the other crop management levers, such as crop nutrient supply and crop protection [123,124,127].

For this pillar, most of the entries were retrieved from studies conducted in Southern Europe (42.65% of total pillar entries), with the remaining European regions being similarly represented in the dataset. We may argue that one possible reason of this evidence could be due to climatic patterns affecting Mediterranean and Southern European countries, where because of heavy fluctuations in weather conditions around the crop establishment periods and along the entire crop cycle call for crop genotypes and crop establishment techniques characterized by high flexibility or adaptation to specific narrow conditions.

3.3.4. Pillar: Diverse Cropping Systems

In this study, the pillar diverse cropping systems comprises 183 entries. The evidence focuses on crop-based tactics such as cover crops (44.8%) and intercropping (27.9%), which together account for about 73% of the entries, whereas landscape management (11.5%), crop rotation (8.2%), and field margin management (7.7%) are less represented (Table 10).

Table 10.

Distribution of the number of entries per tactic of the diverse cropping systems pillar, along with the corresponding counts for different crop types and macro-areas.

This pattern is partly due to study design: crop-based tactics are typically implemented at plot scale and evaluated over a few seasons (i.e., 2–3 years), with meta-analyses reporting consistent short-term weed suppression for cover crops and annual intercrops [128,129]. By contrast, margin/landscape actions require broader spatial replication, coordination across management units at the landscape level, and longer monitoring to detect changes in weed community dynamics [130]. Crop rotation is frequently part of the reference or background system rather than a factorial treatment, and its effects tend to accumulate over multi-year sequences, hence they are captured mainly in long-term rotation studies rather than short trials [131,132]. As a result, this study mostly captures short-to medium-term, plot-level responses, whereas spatially mediated benefits may remain under-documented.

Studying the crop type into the tactic, within cover crops (n = 82), evidence clusters in arable (59.8%) and field vegetables (25.6%), with perennials less represented (orchards 7.3%, vineyards 6.1%, olive 1.2%). Annual systems are more frequently studied, likely because weed pressure is a more immediate constraint on production and because these systems offer a clear off-season window (post-harvest to pre-sowing) during which cover crops can produce biomass without overlapping the cash crop and can be cleanly terminated before planting. This window reduces agronomic risk, allows the use of standard machinery and replication, and targets short-cycle weeds for which suppression can be detected within a few seasons. Consistently, several studies show that cover crops substantially reduce weed biomass and density, with outcomes modulated by management choices (e.g., species/mixtures and termination timing) [82,133]. At the plot scale, weed suppression tends to increase with cover-crop biomass, while the independent effect of mixture diversity is context-dependent [134].

In perennial systems, by contrast, floor management is often split between inter-row covers and within-row strips; replication is more challenging, and reporting of weed metrics is less uniform, indeed, many papers prioritize soil cover, erosion, or habitat indicators. Moreover, in many perennial systems weed suppression, especially in the inter-row, is not a primary management objective compared with soil protection, trafficability, or habitat provision for beneficial organisms (e.g., natural enemies and pollinators), while within-row control typically receives most attention. Consequently, the dataset captures a robust signal for cover crops in annuals, whereas evidence for perennials remains often thin and heterogeneous [135,136,137]. Permanent grasslands are absent in the cover crop tactic, as the herbaceous sward is itself the production surface, so we cannot apply the notion of “cover crop”.

Within the diverse cropping systems pillar, entries outside cover crops are concentrated in arable crops. Intercropping is almost exclusively arable (49/51), crop rotation is entirely arable by design (15/15), and field margin management is reported mainly in arable contexts (13/14). Only landscape management shows a broader spread (arable 52.4%; permanent grasslands 28.6%; scattered cases in vineyards/vegetables/olive). This pattern might be so interpretated: (i) rotation presupposes annually replanted cash crops and is structurally inapplicable to perennial systems [55,138]; (ii) in orchards and vineyards, practices resembling intercropping are typically classified as under-canopy covers/floor vegetation, so they could appear under the cover-crop tactic rather than “intercropping” [87,135,139]; and (iii) field margin management studies are concentrated in arable because margins are discrete external habitats targeted by agri-environmental schemes and evaluated mostly for annual fields, whereas in perennial systems similar actions are recorded as floor vegetation or broader landscape elements rather than “field margins” [140,141,142]. Notably, within landscape management, permanent grasslands contribute a substantial share of entries (6/21), typically focusing on habitat configuration, connectivity, and management mosaics rather than plot-level weed outcomes [143,144].

Geographically, the evidence is concentrated in Western and Southern Europe, which together account for ~72% of entries, whereas the remaining tactics are smaller in absolute terms and unevenly distributed across areas. Considering the tactics individually, Western Europe concentrates the evidence for intercropping, while in Southern Europe dominates cover crops. Central and Eastern Europe carries the largest share of crop rotation and a substantial portion of landscape management. By contrast, Northern Europe contributes only cover crops and intercropping, with just a few entries for rotation. This regional pattern is agronomically and methodologically coherent. Cover crops are concentrated in Southern Europe primarily because autumn–winter windows are more reliable for establishing biomass before spring planting, and because maintaining soil cover between cash crops is promoted to reduce soil and nutrient losses [145,146,147]. The clustering of intercropping in Western Europe likely reflects strong research programs on cereal–legume and oilseed–legume consociations and established trial infrastructure, aimed at reducing reliance on external inputs and increasing resource-use efficiency [132,148]. In Northern Europe, the bulk of the few entries observed consists of cover crops and intercropping, and there is little or no landscape/field margin work in our dataset; it might be due because many studies on margins/landscapes prioritize biodiversity or ecosystem-service outcomes over weed metrics [140,142].

3.3.5. Pillar: Monitoring and Evaluation

In this review, the fifth pillar (monitoring and evaluation) was represented by a limited number of entries (50), mostly because the literature search aimed to catch only papers dealing with this set of tactics specifically to assist Integrated Weed Management in the field, and not to improve general crop management, for bench/in vitro testing innovative weed control practices or to study per se weed spatial variability as related to the effect of the application of weed control strategies. 56% of the entries was classified under the sensing technologies tactic, i.e., the use of sensors for proximal (i.e., ground-level) or remote assessment of weed infestation, coverage, abundance, and composition (Table 11).

Table 11.

Distribution of the number of entries per tactic of the monitoring and evaluation pillar, along with the corresponding counts for different crop types and macro-areas.

This evidence is supported by the dominance of entries collected for this tactic from studies conducted on arable crops, which are more sensitive to damages from imprecise weed control operations compared to tree species. The remaining part of the entries were equally distributed between the decision support system (DSS) and the scouting tactics, that were similarly related to arable crops. Weed scouting for identification and quantification of weed communities in the field is unanimously considered as a pre-condition for implementing a true Integrated Weed Management approach [149,150]. Indeed, knowing the exact weeds and their biological cycles and competitiveness traits is essential to design a weed management strategy and to deploy consistently all the most effective tactics [151]. In our review it was thus difficult to find papers where scouting was considered part of the innovation in weed management. In some cases [152,153,154] what was tested was an improvement in weed scouting strategy or technique, making it interesting to compare it with the standard strategy. The development of decision support systems for weed management has been increasing in recent years, but was mostly focusing on tools to support the identification of weeds by non-expert end users (e.g., systems that uses digital cameras and recognition software to automatically adjust the intensity of weed control intervention, enabling selective weed control while preventing crop damage [155,156]) or to identify economic threshold for weed control intervention, mostly by herbicide application [157,158,159]. New advancements have been recently made in on-field automatic weed species identification thanks to the simultaneous exponential development and improvement of artificial intelligence (AI) systems, empowered by machine learning and 5G networks, fed by high definition imagery caught from tractors, robots, s or end users’ mobile devices [160,161,162]. Nevertheless, these kinds of tools and applications are the object of papers validating them or documenting their development and improvement, but very few papers tested their efficacy in supporting weed control in field conditions, possibly in comparison with alternative methods [163,164].

3.4. Overall Considerations for the Systematic Review

The present review allows us to understand how many studies have been conducted, and therefore how extensively the various tactics within the different pillars forming the foundation of IWM have been investigated. Scopus was used to carry out the online literature search. Although it limited access to some regional or technical publications, the database offered robust and comprehensive coverage of leading scientific journals. This provided access to high-quality, peer-reviewed research on topics relevant to IWM, thus supporting retrieval of a wide range of evidence available in the scientific literature. However, some limitations were also identified such as those inherently linked to the methodology adopted and the types of scientific studies available. These limitations are structural and methodological in nature with respect to the objective of evaluating IWM. In fact, although the systematic review approach allows the isolation of the effects of individual practices or crop management operations on weeds, it led to a reductionist perspective. This reductionist approach did not allow the importance of a systems-based perspective to emerge, and this is recognized as the only true win–win solution in IWM [24]. Consequently, aspects arising from the synergistic interaction among the various components of IWM, and thus among different tactics within the agricultural system, fundamental for an effective weed management strategy, may not have been adequately addressed. The reductionist approach, by focusing on studies investigating single tactics, has partly favored short-term studies, such as those on mechanical weeding for example, which are well represented in the results. The eligibility criterion based on agronomic indicators, according to which scientific articles not reporting the effects of the tactic in terms of at least one weed indicator (cover, density, biomass) were not included, may have limited the number of entries for tactics and pillars that are less assessable from such perspectives. This is the case, for example, of the monitoring and evaluation pillar.

The results showed that the most investigated practices are those that are easier to test in the field, both from a practical standpoint and in terms of the time required, as evidenced by the entries found for the direct control pillar. Moreover, the most studied practices are usually those that can be more easily transferred to end users, the farmers. These are tactics that meet criteria such as applicability, being feasible in real agricultural contexts, readiness for practical implementation, and adaptability to different pedoclimatic conditions more easily compared to others. Conversely, the number of entries is lower for practices that are more challenging to evaluate, such as agronomic techniques fundamental to IWM, including crop diversification or landscape diversification. Some tactics still at the proof-of-concept stage, such as biological control, have achieved a relatively high score.

This systematic review represents a first attempt to provide an updated overview of the current state of the art of alternative techniques to the use of chemical herbicides within the context of IWM in Europe. It is based on the recent IWM framework developed within the EU-H2020 IWMPRAISE project. Through this review, the state of scientific knowledge regarding these techniques has been assessed across the twenty-seven EU Member States and the UK. The use of the IWMPRAISE framework proved highly useful for organizing and systematizing the collected information. Based on the extracted data, this review may pave the way for future meta-analyses on the effectiveness and readiness of IWM tactics that serve as alternatives to herbicides. The document also allows an evaluation of how extensively IWM tactics have been investigated in scientific research, by considering different crop types and European regions. Importantly, the state-of-the-art analysis highlights existing gaps in scientific knowledge for specific tactics and helps to identify research priorities for the future. The findings provide valuable indications of which tactics require further study, and which crops or regions would benefit most from additional evaluation to strengthen the current knowledge base. The results also offer insights relevant to policy development, helping to guide funding and support mechanisms that can encourage scientific research. All this contributes to increasing knowledge and understanding of the different tactics that make up IWM among all stakeholders—from farmers and technical advisors to policymakers—thereby fostering their adoption for more effective, efficient, and sustainable weed management.

4. Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to provide an updated synthesis of recent scientific publications (2013–2022) addressing alternative methods to chemical herbicides for weed management across the EU-27 and the UK, covering the main cropping systems. Overall, an increasing trend in entries was observed over the study period, reflecting growing scientific and societal awareness of the need to develop alternative strategies, in line with European Union policies to reduce the use and risk of chemical pesticides.

The primary goal of the present study was to identify which Integrated Weed Management (IWM) tactics have received greater or lesser scientific attention. The analysis revealed a marked predominance of studies within the direct control pillar (28.98%), followed by diverse cropping systems (27.48%). The first likely reflects the greater applicability and immediacy of these tactics for end users, as well as the possibility of obtaining transferable results in shorter timeframes. Conversely, the interest in diverse cropping systems may stem from the long-term agronomic and ecological benefits they provide, reinforced by European policies promoting ecosystem services. Arable crops dominated the dataset (67.57% of entries), which is consistent with their extensive territorial coverage, key role in food and feed production, and higher susceptibility to weed pressure. Geographically, Southern Europe accounted for the largest share of studies (40.24%), possibly due to its greater exposure to climate change impacts, high biodiversity, and the complexity of weed management under diverse pedoclimatic conditions. Therefore, the amount of scientific literature produced appears to reflect the practical needs and specific characteristics of the different areas considered. Among individual tactics, tillage type and cultivation depth, cover crops, and biological control were the most frequently investigated, owing to their practical relevance, short-term weed suppression potential, and environmental advantages. Conversely, tactics such as seed vigor, sowing depth, and water management were rarely studied, likely because of the need for long-term experiments, higher investment requirements, and limited transferability. Overall, this review highlights existing research gaps and provides useful insights for setting future research priorities aimed at strengthening the scientific basis of IWM. Moreover, the findings may inform policy development and guide funding strategies to promote broader knowledge and adoption of sustainable weed management practices across Europe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A., C.F., L.G. and L.G.T.; methodology, D.A., C.F., L.G., L.G.T. and M.S.; software, D.A., C.F., L.G., L.G.T. and M.S.; validation, D.A., L.G. and L.G.T.; formal analysis, L.G. and L.G.T.; investigation, D.A., C.F., L.G., L.G.T., M.S., G.S., E.M., L.P., N.D., O.K., B.E.G., A.K., N.A., I.G., E.L., A.T., K.G., L.T., C.G., F.P., T.B., F.J.R.-R., M.R.M.-L., M.F. and V.Z.; resources, D.A. and C.F.; data curation, L.G. and L.G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G., L.G.T. and D.A.; writing—review and editing, C.F., M.S., G.S., E.M., L.P., N.D., O.K., B.E.G., A.K., N.A., I.G., E.L., A.T., K.G., L.T., C.G., F.P., T.B., F.J.R.-R., M.R.M.-L., M.F., V.Z. and S.F.; visualization, L.G. and L.G.T.; supervision, D.A. and C.F.; project administration, D.A., C.F. and S.F.; funding acquisition, D.A., C.F. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2021–2027) under grant agreement No. 1010606591 (OPER8—European Thematic Network for unlocking the full potential of Operational Groups on alternative weed control).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Zenodo open access repository at the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17672318, accessed on 11 November 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Kevin Godfrey and Lynn Tatnell were employed by the company RSK ADAS Ltd. Author Thomas Börjesson was employed by the company Agroväst Livsmedel AB. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Monteiro, A.; Santos, S. Sustainable Approach to Weed Management: The Role of Precision Weed Management. Agronomy 2022, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennan, H.; Jabran, K.; Zandstra, B.H.; Pala, F. Non-Chemical Weed Management in Vegetables by Using Cover Crops: A Review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.E.; Howell, G.S. Initial Response of Baco Noir Grapevine to Pruning Severity, Sucker Removal, and Weed Control. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1978, 29, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.E. Broccoli (Brassica Oleracea Var. Botrytis) Yield Loss from Italian Ryegrass (Lolium perenne) Interference. Weed Sci. 1995, 43, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbmann, A.; Christen, O.; Petersen, J. Development of Herbicide Resistance in Weeds in a Crop Rotation with Acetolactate Synthase-tolerant Sugar Beets under Varying Selection Pressure. Weed Res. 2019, 59, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, D.; Akça, A. Assessment of Weed Competition Critical Period in Sugar Beet. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 24, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, L.K. Growth and Productivity of Maize (Zea mays L.) as Influenced by Organic Weed and Nutrient Management Practices in Western Rajasthan. Ann. Plant Soil Res. 2022, 24, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, C.; Sah, S.K.; Marahatta, S.; Dhakal, S. Weed Dynamics in No-Till Maize System and Its Management: A Review. Agron. J. Nepal 2021, 5, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumari, S.; Rana, S.S.; Rana, R.S.; Anwar, T.; Qureshi, H.; Saleh, M.A.; Alamer, K.H.; Attia, H.; Ercisli, S.; et al. Weed Management Challenges in Modern Agriculture: The Role of Environmental Factors and Fertilization Strategies. Crop Prot. 2024, 185, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, A.; Wolna-Maruwka, A.; Niewiadomska, A.; Pilarska, A.A. The Problem of Weed Infestation of Agricultural Plantations vs. the Assumptions of the European Biodiversity Strategy. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, C.; Storkey, J.; Menegat, A.; Metcalfe, H.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K. An Ecological Future for Weed Science to Sustain Crop Production and the Environment. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munier-Jolain, N.M.; Chavvel, B.; Gasquez, J. Long-term Modelling of Weed Control Strategies: Analysis of Threshold-based Options for Weed Species with Contrasted Competitive Abilities. Weed Res. 2002, 42, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.J.P. Biodiversity, Herbicides and Non-Target Plants; Researchgate: Brighton, UK, 2001; pp. 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Druille, M.; Omacini, M.; Golluscio, R.A.; Cabello, M.N. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Are Directly and Indirectly Affected by Glyphosate Application. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2013, 72, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.T.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Scanlan, C.A.; Rose, T.J.; Vancov, T.; Kimber, S.; Kennedy, I.R.; Kookana, R.S.; Zwieten, L.V. Impact of Herbicides on Soil Biology and Function. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; Volume 136, pp. 133–220. [Google Scholar]

- Relyea, R.A. The impact of insecticides and herbicides on the biodiversity and productivity of aquatic communities. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamane, A.; Baldi, I.; Tessier, J.-F.; Raherison, C.; Bouvier, G. Occupational Exposure to Pesticides and Respiratory Health. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2015, 24, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almberg, K.; Turyk, M.; Jones, R.; Rankin, K.; Freels, S.; Stayner, L. Atrazine Contamination of Drinking Water and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Community Water Systems with Elevated Atrazine in Ohio, 2006–2008. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commmission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Commmittee and the Commmittee of the Regions, the European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commmission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Commmittee and the Commmittee of the Regions, Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti, S. Weed Seed Movement and Dispersal Strategies in the Agricultural Environment. Weed Biol. Manag. 2007, 7, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Andujar, J.L. Integrated Weed Management: A Shift towards More Sustainable and Holistic Practices. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemens, M.; Sønderskov, M.; Moonen, A.-C.; Storkey, J.; Kudsk, P. An Integrated Weed Management Framework: A Pan-European Perspective. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 133, 126443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S.R. Non-Chemical Methods of Weed Control: Benefits and Limitations. In Proceedings of the 17th Australasian Weed Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 26–30 September 2010. [Google Scholar]