Abstract

Spent mushroom substrate (SMS) is an excellent conditioner for livestock manure composting. However, existing studies have confirmed that it is difficult to achieve the desired effect by directly mixing SMS with manure. Coarse (≥2 mm) and fine (<2 mm) of SMS particles from an edible fungus (Auricularia auricula) were obtained after sieving and used for cow manure composting. In our study, the appropriate ratio of coarse SMS to fine SMS particles added to the manure was explored. Four treatments were designed, adding 20% coarse SMS (T1), 15% coarse SMS + 5% fine SMS (T2), 5% coarse SMS + 15% fine SMS (T3), and 20% fine SMS (T4) to cow manure for composting, respectively. The physicochemical properties, maturity, and nutrient content of the composts were analyzed in a 35-day composting trial. The optimal treatment was determined through a comprehensive evaluation using the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method. The results showed that the highest composting temperature reached 65.13 °C in T3, and the duration of the thermophilic phase of T2 was the longest. The relative germination rate was not affected, and the relative radicle growth (RRG) reflected the variation in phytotoxicity during composting. After composting, the pH of the finished composts was between 8.78 and 9.05. The electric conductivity was between 2207 and 2513 μS cm−1. The ammonium nitrogen content was less than 150 mg kg−1, which was at the level found in mature compost. The RRG was no less than 80%, indicating the compost was mature and had no phytotoxicity. The available phosphorus and potassium contents increased by 4.8% to 59.1% compared with that before composting. The comprehensive evaluation showed that the treatment supplemented with 15% coarse SMS and 5% fine SMS was optimal.

1. Introduction

China is the world’s largest producer of edible fungi, with a production of 43.34 million tons in 2023, accounting for over 85% of the global total [1,2]. Spent mushroom substrate (SMS) is the discarded cultivation substrate of edible fungus after harvesting [3]. Specifically, approximately 1 kg edible fungus could generate 5 kg SMS (by dry weight) [4]. Although the cultivation substrates differ among various edible fungi, they are mainly composed of sawdust, wheat bran, cotton seed hull, and corn cob, which are rich in lignocellulose [5,6].

Livestock manure can be rapidly converted into stable humic-like substances via composting. However, livestock manure is a high-moisture and viscous material with poor ventilation and usually requires the addition of conditioners for composting [7]. SMS is loose and porous, allowing it to be easily air-dried and then stored for a long time. Therefore, it is an ideal conditioner for animal manure composting. For example, the cultivation substrate of Auricularia auricula is mainly composed of sawdust and wheat bran, accounting for about 78% and 20% of its composition, respectively, with the remaining 2% being 1% gypsum and 1% lime [8]. After the cultivation of the edible fungus, its SMS was agglomerated and porous, which could be easily broken. The protein and polysaccharide contents of SMS decreased significantly by 50% and 79% after composting, indicating that the easily degradable organic matter in the SMS could provide carbon sources for microorganisms [9]. The content of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin did not change significantly after adding SMS in pig manure composting, indicating that most of the SMS was difficult for composting microorganisms to degrade and utilize [10]. In existing studies on the optimal proportion of SMS addition, Li et al. [11] added 5% to 10% SMS (by fresh weight) to the mixture of pig manure and corn straw for composting. It was found that SMS could make the composting process enter the thermophilic phase in advance and accelerate the maturation of the compost, mainly because the loose SMS increased the porosity and improved the air permeability of the composting pile. Lei et al. [12] mixed the SMS with cow manure at a fresh weight ratio of 7:3 for 90 d to achieve a high maturity. However, the relatively high SMS proportion prolonged the duration of composting. Zhou et al. [13] showed that the composting time was shorter when the mix ratio of SMS and pig manure was 1:4 (by fresh weight), reaching a high maturity after 33 d. Additionally, the compost maturity decreased as the proportion of SMS increased, indicating that excessive SMS was not favorable to composting. Moreover, Liu et al. [14] found that the temperature of the composting pile was low and the maturity was poor when the SMS was directly mixed with cow manure for composting. The above studies have confirmed that the conditioning effect of SMS in livestock manure composting was not fully exerted. However, through simple screening with a 2 mm sieve, the large recalcitrant part and small degradable part of the SMS can be separated. Therefore, we suggest that there is a suitable proportion of coarse (≥2 mm) and fine (<2 mm) of sieved SMS particles to be added to livestock manure composting, which requires further investigation.

In this study, by adding different proportions of coarse SMS and fine SMS to cow manure for composting, we analyzed the influence of different parts of SMS on the composting process and its product. Using the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, we comprehensively evaluated the optimal addition ratio of coarse SMS and fine SMS based on the aspects of harmlessness, maturity, and nutrient composition, thereby providing a theoretical basis for optimizing the application effect of SMS in cow manure composting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composting Materials

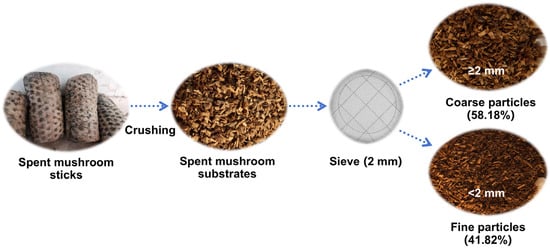

The cow manure used in this study was taken from a large-scale dairy farm in Shanxi Province, China, and the SMS of Auricularia auricula was obtained from an edible fungus plant in Shanxi Province, China. The moisture content, organic carbon, and total nitrogen content of cow manure were 80.18%, 20.11%, and 4.42%, respectively. The moisture content, organic carbon, and total nitrogen contents of the SMS were 42.47%, 40.13%, and 1.19%, respectively. According to the degree of crushing, the SMS were sieved into coarse SMS (≥2 mm) and fine SMS (<2 mm), accounting for 58.18% and 41.82%, respectively (Figure 1). Their physicochemical properties are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The procedures of different parts of SMS obtained through sieving.

Table 1.

The main physicochemical properties of different parts of SMS.

2.2. Composting Designs

Based on the results of the composting supplemented with SMS in our previous study [14], cow manure and SMS were mixed at a ratio of 4:1 by fresh weight. To study the conditioning effect of different parts of SMS, the ratio of coarse SMS and fine SMS added was adjusted, with a fixed total amount. Except for the treatment that was only supplemented with coarse SMS or fine SMS, a high proportion of coarse SMS and a high proportion of fine SMS were set, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

The design of the composting experiment.

The composting site was an experimental station of the College of Resources and Environment of Shanxi Agricultural University. Composting was carried out in 60 L plastic insulation boxes (63 cm in length, 48 cm in width, 36 cm in height, and 5 cm in wall thickness). The total weight of the materials was 25 kg, and the composting lasted for 35 d. The temperature at the center of the pile was collected by an automatic temperature recorder (RC-4, Elitech, Xuzhou, China). Turning and sampling of the pile were conducted on days 0, 3, 6, 10, 15, 25, 30 and 35. After air-drying, the samples were analyzed for physicochemical properties. The compost phytotoxicity was evaluated by a seed germination test [15].

2.3. Analysis Methods

2.3.1. Analysis of Physicochemical Properties

The volumetric weight and water absorption ratio of coarse SMS and fine SMS were measured by weighing [16]. The ash content was determined by burning at 550 °C. The air-dried sample and deionized water were mixed at a ratio of 1:20 (w/v) to prepare compost water extract. The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of compost water extract were determined by a pH/EC meter (MP521, APERA, Shanghai, China). Ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) and nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) were determined by a segmented flow analyzer (FUTURA, AMS Alliance, Frépillon, France). Total organic carbon and organic matter contents were determined with potassium dichromate. Total nitrogen content was determined by Kjeldahl. Available phosphorus content was determined by the NaHCO3 extraction method, and available potassium was determined by NH4OAc extraction. The contents were calculated by dry weight.

2.3.2. Seed Germination Test

A filter paper was placed in a 90 mm diameter Petri dish. Then, 6 mL of compost water extract was added (using deionized water as the control), followed by 30 Chinese cabbage seeds (Brassica rapa L. subsp. pekinensis). The culture dishes were placed in a constant-temperature incubator at 25 °C for 24 h in the dark. Seed germination was recorded; then, 3 mL of compost water extract was replenished. The seeds were further cultured in the dark for an additional 24 h. Subsequently, the radicle length of the germinated seeds was measured. Finally, the relative germination rate (RSG) and relative radicle growth (RRG) of seeds were calculated [17].

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS 22, and Tukey’s HSD test was used to compare differences among treatments at p < 0.05 (n = 3). Seven indexes of composting process and compost quality (effective accumulated temperature, NO3−-N/NH4+-N, RRG, organic matter, total nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium) were selected and weighted via the entropy weight method. The entropy-weighted TOPSIS method was used to rank the treatments from the best to the worst [18,19]. All figures were realized using Origin 2021.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Composting Temperature

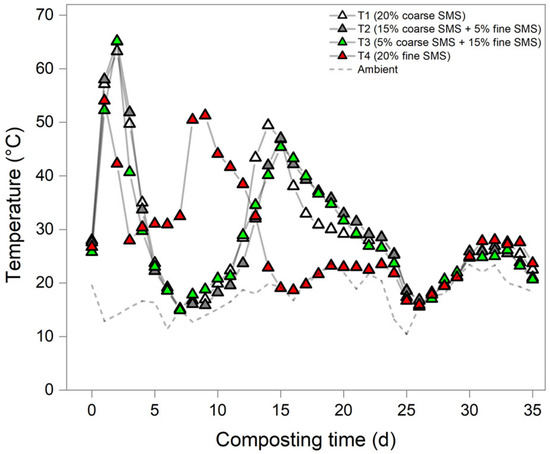

Temperature is a key indicator for dividing the composting process and determining the harmlessness of the compost [20]. As shown in Figure 2, all treatments entered the thermophilic phase (≥50 °C) on the first day. Their highest temperatures were reached on the second day, and were 63.28 °C, 65.05 °C, 65.13 °C, and 54.05 °C, respectively. The duration of the thermophilic phase was 2 d for both T1 and T3, while it lasted 3 d for both T2 and T4. Compared with pilot-scale or full-scale composting, the duration of the thermophilic phase of the lab-scale composting was shorter, which was mainly related to the rapid heat dissipation of the pile [10,21,22]. Moreover, the effective accumulated temperature is the integrated value of the difference between the temperatures of the composting pile and that of its environment, which can reflect the temperature differences among the treatments during composting [23]. During composting, the effective accumulated temperature ranked as follows: T1 (411.53 °C) > T2 (407.27 °C) > T3 (384.17 °C) > T4 (379.73 °C). The values of T1 and T2 were close and higher than those of T3 and T4.

Figure 2.

Changes in temperature during composting.

3.2. Compost Basic Properties

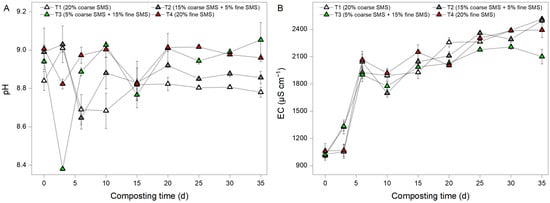

The pH was between 8.38 and 9.05 during composting (Figure 3A), which was at a suitable pH for microorganisms [24]. The pH of all treatments stabilized after 20 d, with final values of 8.78, 8.86, 9.05, and 8.96, respectively. There was no significant difference in pH changes before and after composting (p > 0.05). The EC can reflect the change in soluble salt content during composting. It is higher than 4000 μS cm−1, which can inhibit seed germination [25]. The change in EC rose rapidly before day 7 and gradually stabilized after day 25 (Figure 3B). The EC values of the treatments after composting were 2513, 2497, 2207, and 2393 μS cm−1, respectively. The EC of T3 was significantly less than those of the other treatments (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Changes in (A) pH and (B) electrical conductivity (EC) during composting. Data were means ± SD (n = 3).

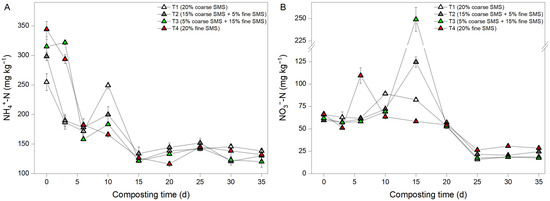

3.3. Compost Inorganic Nitrogens

Nitrifying bacteria can convert a part of NH4+-N to NO3−-N during composting, while a part of NH4+-N escapes in the form of NH3, resulting in nitrogen loss [26]. High temperatures can inhibit the activity of nitrifying bacteria, so the NO3−-N increases significantly during the cooling and curing phases, indicating that the compost is close to the mature level [27]. The NH4+-N in all treatments showed a trend of decreasing and then tending towards stability (Figure 4A). After day 15, the NH4+-N of all treatments gradually stabilized. At the end of composting, the NH4+-N of each treatment was 138, 130, 120, and 132 mg kg−1, respectively. As shown in Figure 4B, the NO3−-N of T1 reached its maximum value of 89 mg kg−1 on day 10; those of T2 and T3 reached their maximum values of 124 and 249 mg kg−1 on day 15, respectively; and that of T4 reached its maximum value of 109 mg kg−1 on day 6. All treatments tended to be stable after day 25, remaining below 25 mg kg−1. The NH4+-N content was at the maturity threshold (75–500 mg kg−1) for animal manure composts [28].

Figure 4.

Changes in (A) ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) and (B) nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) during composting. Data were means ± SD (n = 3).

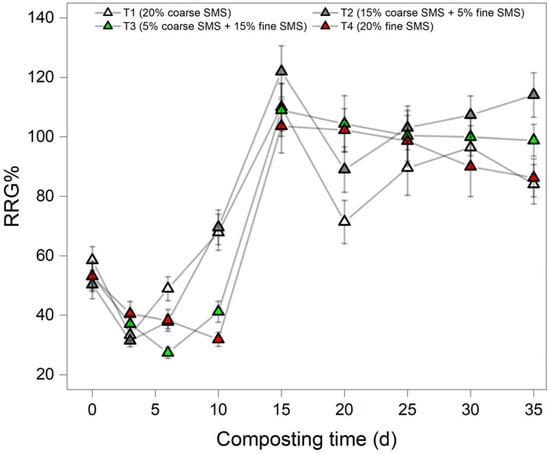

3.4. Compost Phytotoxicity

The phytotoxicity of compost is routinely evaluated by a seed germination test, including the indexes of relative germination rate (RSG) and relative radicle growth (RRG). The RRG is more sensitive than the RSG [17,29], because the phytotoxicity level that inhibits seed germination is higher than that which inhibits radicle elongation. The decrease in RSG indicates that the compost phytotoxicity is higher and the maturity is extremely poor. If the compost has no effect on RSG, its effect on seed radicle elongation needs to be further tested. Subsequently, the maturity can be determined by the RRG [17,29]. In general, the change in RSG in each treatment was small, which was between 88% and 102%, indicating that the compost had little effect on seed germination—that is, low phytotoxicity. The RRG of each treatment first decreased, then increased, then finally stabilized (Figure 5). T1 and T2 reached their minimum values of 33% and 31% on day 2, respectively. T3 and T4 reached their minimum values of 27% and 32% on days 5 and 10, respectively. If the RRG is no less than 80%, the compost can be considered mature and has no phytotoxicity [29,30]. All treatments reached their maximum values of 110%, 122%, 109%, and 104% on day 15, respectively. At the end of the composting process, the RRG values were 84%, 114%, 99%, and 86%, respectively. The RRG of T2 was the largest, which was significantly higher than those of the other treatments (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Changes in relative radicle growth (RRG) during composting. Data were means ± SD (n = 3).

3.5. Compost Quality

As shown in Table 3, after composting, the organic matter content decreased, while the nutrient contents increased. Compared with the initial compost, the organic matter content of T4 decreased by 7.1%, and the total nitrogen content increased by 167%. The total nitrogen content of T4 was significantly higher than those of the other treatments (p < 0.05). The increases in available phosphorus content were 14.3% for T1, 19.0% for T2, 13.6% for T3, and 4.8% for T4, while the increases in available potassium were 56.7% for T1, 59.1% for T2, 49.4% for T3, and 49.3% for T4. Both the increase in available phosphorus and the increase in available potassium content in T2 were the largest. After composting, the available phosphorus contents of T1, T2, and T3 were significantly higher than that of T4 (p < 0.05), and the available potassium contents of T1 and T4 were significantly higher than that of T3 (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Nutrient content of composts.

3.6. Comprehensive Evaluation

The harmlessness, maturity indexes, and nutrient content of composts were subjected to the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method. Using the entropy-weighted method to determine the weight of each index, and the treatments were finally ranked. The results are shown in Table 4. The smaller the distance to the optimal solution (D+) and the larger the distance to the worst solution (D−), the greater the relative closeness (Ci), indicating that the treatment evaluated was superior. The results pointed to the following order: T2 > T4 > T3 > T1. T2 ranked first, indicating that the treatment with 15% coarse SMS and 5% fine SMS added to cow manure for composting was optimal.

Table 4.

Comprehensive evaluation ranking of different treatments.

4. Discussion

Screening is an easy and essential operation in factory-scale composting. In this study, the crushed SMS was sieved into two parts based on its particle size, including coarse SMS (≥2 mm) and fine SMS (<2 mm), and their weight ratio was close to 1:1. There were significant differences in water absorption ratio, total organic carbon, ash, and other physicochemical properties between them. This was primarily because the larger sawdust particles were retained in the coarse SMS after sieving, leading to its higher total organic carbon content. The coarse SMS enhanced the porosity of the pile, so it was considered suitable as a bulking agent for composting [31]. The fine SMS is mainly composed of small sawdust, wheat bran, and inorganic salts, which can easily be utilized by microorganisms during composting [32]. Therefore, it was suitable as a nutrient supplement for composting. However, compared with the coarse SMS, the fine SMS contains more minerals, which makes it prone to forming clumps during composting. Excessive use can impede the composting process. The composting with 15% coarse SMS and 5% fine SMS added was optimal. This indicated that the two components achieved a favorable balance between maintaining sufficient porosity and providing available substances for microorganisms.

The addition ratio of coarse SMS and fine SMS had a substantial influence on the temperature of the pile. The highest temperature of the composting supplemented with 20% fine SMS did not reach more than 55 °C, indicating that it did not realize sufficient harmlessness. The main reason was that only fine SMS was added, so the porosity of the pile during the early composting stage was relatively small, which limited the oxygen supply inside the pile. The highest temperature of the composting supplemented with 15% coarse SMS and 5% fine SMS was close to that of the composting supplemented with 5% coarse SMS and 15% fine SMS, and the former had the longest thermophilic phase, which ensured the effective harmlessness of the compost. This can primarily be attributed to the appropriate ratio of coarse SMS to fine SMS added.

The addition of coarse SMS and fine SMS had little effect on the pH or EC. The decrease in pH was due to the production of organic acids and CO2 [33], while the increase in pH was due to the decomposition and utilization of organic acids by microorganisms and the accumulation of NH4+ [34]. The EC increased rapidly in the early composting stage because the microorganisms were active and multiplied, and the organic matter was decomposed into various soluble inorganic ions [35].

The low NO3−-N content during the curing phase of the composting process could be attributed to the fact that more NH4+-N was converted into organic nitrogen [36]. In addition, the curing phase is also an active period for denitrification to produce nitrous oxide (N2O) [37]. Further research is needed to determine whether the previously accumulated nitrate nitrogen is lost in the form of N2O during this period. Factors such as hypoxic conditions, low fermentation temperature, a pH below 5 or above 8, and excessive NH4+-N can inhibit nitrification [37]. The content of NO3−-N in the composting supplemented with 5% coarse SMS and 15% fine SMS reached its peak in the second heating period, which could be due to suitable temperature, humidity, and other conditions, and the nitrifying bacteria was active. The NH4+-N was lost in the form of NH3 or converted into NO3−-N during composting, resulting in a decreasing trend in NH4+-N [38].

The composts had a small impact on the seed germination rate, indicating a low phytotoxicity. The RRG of the composts showed a decreasing trend in the early composting stage. The decomposition of organic matter produced a large amount of organic acids and NH4+ [39,40], which had a toxic effect on seed radicle elongation. As the composting entered the cooling and maturing stages, the transformation of NH4+-N and the degradation of phytotoxic substances led to the gradual maturation of the composts. The RRG gradually increased and finally tended towards stability. At the end of the composting process, the RRG of the treatment supplemented with 15% coarse SMS and 5% fine SMS was the highest, indicating that this addition ratio of different SMS particles in the treatment was more effective in eliminating compost phytotoxicity and enhancing compost maturity.

The decrease in total amounts of organic matter and nitrogen during composting was due to these substances providing energy and nutrition for microorganisms [41]. During the decomposition of organic matter, a large amount of oxygen was consumed inside the composting pile, resulting in a local anaerobic environment. In this case, the phosphate adsorbed by metal oxides and hydroxides was released as the high-valence metal was reduced [42]. The main period for the increase in available phosphorus content occurred in the thermophilic phase, and microorganisms were the principal factor underlying phosphorus activation [43]. Among the treatments, the composting supplemented with 15% coarse SMS and 5% fine SMS had the longest thermophilic phase duration, which could better convert organic phosphorus into inorganic phosphorus. Consequently, it showed the highest increase in available phosphorus content. Thermophilic microorganisms played a major role in the release of potassium. The production of organic acids and humic acids during composting also improved the activation of potassium. At the later stage of the composting process, the temperature gradually decreased, and mesophilic microorganisms became active again and played a role in dissolving potassium [44]. Therefore, the available phosphorus and potassium contents increased after composting.

From the changes in the indexes, it can be seen that the conditioning effect neither increased nor decreased with the decrease in the proportion of coarse SMS or the increase in the proportion of fine SMS. By selecting representative indexes for a comprehensive evaluation with the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, we concluded that there is an optimal addition ratio of coarse and fine SMS particles in cow manure for composting; too much or too little of them will reduce the conditioning effect. However, in our evaluation, we only considered the harmlessness of composting and the maturity and nutrients of the composting product. In future study, we will need to account for greenhouse gas emissions during composting—that is, to take into account the impact of this process on the environment and to promote clean composting [45].

5. Conclusions and Prospects

The additional proportions of coarse SMS and fine SMS had a significant influence on the composting temperature, compost maturity, and available nutrients. The composting supplemented with a high proportion of coarse SMS and a low proportion of fine SMS had a superior effect on cow manure composting and its product. In conclusion, the fine SMS can be utilized during composting, while coarse SMS can increase the porosity of the composting pile. However, the coarse SMS is difficult to decompose and utilize, and its residues will affect composting humification. Therefore, it is necessary to further the research on the degradation dynamics of coarse SMS and to develop measures for improving its transformation during composting. Moreover, the coarse SMS recovered through screening can be recycled in animal manure composting, which also requires further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Y.Z.; methodology, Y.Z., Y.S. and Y.L.; investigation, Y.Z. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y. and Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Innovation Foundation of Science and Technology of Shanxi Agricultural University [2020BQ57], the Open bidding Programs of Science and Technology Major Special Plan of Shanxi Province [202201140601028], and the Key research and development project of Shanxi Province [202202140601012].

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| EC (μS cm−1) | Electric conductivity |

| NH4+-N (mg kg−1) | Ammonium nitrogen |

| NO3−-N (mg kg−1) | Nitrate nitrogen |

| RRG% | Relative radicle growth |

| RSG% | Relative germination rate |

| SMS | Spent mushroom substrate |

References

- Ling, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhao, R.; Cao, B.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Tan, H.; Kong, F.; He, M.; Hyde, K. Overview of the Chinese Edible Fungi Industry of and Developing Trends Analysis. Mycosphere 2025, 16, 2712–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, M. Analysis of Current Status and Problem for Industrialized Production of Edible Fungi in China. Agric. Eng. Technol. 2021, 41, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Li, T.; Liu, C.; Liang, Y.; Sun, H.; Chai, Y.; Yang, T.; Gong, X.; Wu, Z. Extraction and Utilization of Active Substances from Edible Fungi Substrate and Residue: A Review. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilik, B.; Akdağ, A.; Ocak, N. Different Milling Byproduct Supplementations in Mushroom Production Compost Composed of Wheat or Rice Straw Could Upgrade the Properties of Spent Mushroom Substrate as a Feedstuff. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2024, 48, e000524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdullah, H.U.; Xu, Y.; Abbas, A.; Hassan, M.A.; Sajad, S.; Rafiq, M.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y. Impact of Artemisia argyi and Stevia rebaudiana Substrate Composition on the Nutritional Quality, Yield and Mycelial Growth of L. edodes Addressing Future Food Challenges. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Sun, H.; Chai, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, C.; Gong, X.; Liang, Y.; Qin, P. Expanding the Valorization of Waste Mushroom Substrates in Agricultural Production: Progress and Challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 2355–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Advance on Composting of Solid Waste and Utilization of Additives. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2003, 22, 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, Q.; Ma, Y.; Xi, X.; Liu, J.; Dai, X.; Han, Z.; Kong, X.; Zhang, P. Study on Optimal Formula of Sawdust and Wheat Bran for Auricularia heimuer Cultivation. Edible Fungi China 2020, 39, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, J. Conversion of Spent Mushroom Substrate to Biofertilizer Using a Stress-Tolerant Phosphate-Solubilizing Pichia farinose FL7. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 111, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wang, X.; Zhen, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Peng, H.; Lei, L.; Zhao, W. Effects of Inoculating with Lignocellulose-Degrading Consortium on Cellulose-Degrading Genes and Fungal Community during Co-Composting of Spent Mushroom Substrate with Swine Manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 291, 121876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, L. Effects of Bacterial Bran on Maturity Index of Aerobic Composting of Pig Manure and Its Relevant Evaluation Analysis. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2023, 60, 242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, W.; Li, M.; He, D.; Sheng, B.; Li, F.; Zhou, C.; Wang, N. Effects of Different Ratios of Spent Mushroom Substrate to Cattle Manure on Nutrient Property and Germination Index of Composting. J. Northeast Agric. Sci. 2021, 46, 52–56, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, X. Optimum Ratio of Pig Manure to Edible Fungi Residue Improving Quality of Organic Fertilizer by Composting. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2015, 31, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J.; Cheng, H.; Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Analysis of the Phytotoxicity Sources During Aerobic Composting of Cow Manure. J. Shanxi Agric. Univ. 2022, 42, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Dang, R.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. Determining the Extraction Conditions and Phytotoxicity Threshold for Compost Maturity Evaluation Using the Seed Germination Index Method. Waste Manag. 2023, 171, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Liu, J.; Kang, L.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Q. Characteristics and Environmental Impact of the Waste Material Cultured. Environ. Pollut. Control 2012, 34, 45–48, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Yuan, J.; Li, G.; Li, S.; Jiang, T.; Tan, J.; Xing, W. Applicability of Seed Germination Test to Evaluation of Low C/N Compost Maturity. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Sun, H.; Dong, X.; Chen, P.; Zhang, X.; Tian, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Did Manure Improve Saline Water Irrigation Threshold of Winter Wheat? A 3-Year Field Investigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 258, 107203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Lou, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, H.; Liang, J.; Guo, J.; Li, N.; Yang, Q. Combined Application of Coffee Husk Compost and Inorganic Fertilizer to Improve the Soil Ecological Environment and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Arabica Coffee. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthod, J.; Rumpel, C.; Dignac, M. Composting with Additives to Improve Organic Amendments. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Toyoda, S.; Shimojima, R.; Osada, T.; Hanajima, D.; Morioka, R.; Yoshida, N. Source of Nitrous Oxide Emissions during the Cow Manure Composting Process as Revealed by Isotopomer Analysis of and amoA Abundance in Betaproteobacterial Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Yuan, X.; Cui, Z. Co-Composting of the Biogas Residues and Spent Mushroom Substrate: Physicochemical Properties and Maturity Assessment. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 276, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Luo, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Li, G. Effects of the Aeration Pattern, Aeration Rate, and Turning Frequency on Municipal Solid Waste Biodrying Performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 218, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, T.; Zhang, X.; Wan, Y.; Deng, R.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Effect of Different Livestock Manure Ratios on the Decomposition Process of Aerobic Composting of Wheat Straw. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Aziz, H.A. Evaluation of Thermochemical Pretreatment and Continuous Thermophilic Condition in Rice Straw Composting Process Enhancement. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 133, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, Z.; Tang, Y.-Q.; Kida, K. Insight into the Microbiology of Nitrogen Cycle in the Dairy Manure Composting Process Revealed by Combining High-Throughput Sequencing and Quantitative PCR. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Zhuo, Q.; Su, Y.; Qu, H.; He, X.; Han, L.; Huang, G. Nitrogen Evolution during Membrane-Covered Aerobic Composting: Interconversion between Nitrogen Forms and Migration Pathways. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.P.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Moral, R. Composting of Animal Manures and Chemical Criteria for Compost Maturity Assessment. A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liang, J.; Zeng, G.; Chen, M.; Mo, D.; Li, G.; Zhang, D. Seed Germination Test for Toxicity Evaluation of Compost: Its Roles, Problems and Prospects. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.J.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, C.N.; Umeda, M. Evaluation of Maturity Parameters and Heavy Metal Contents in Composts Made from Animal Manure. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Ren, N. Succession of Bacterial Community Function in Cow Manure Composing. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 267, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Zang, B.; Li, Y. Effect of Spent Mushroom Substrate as a Bulking Agent on Gaseous Emissions and Compost Quality during Pig Manure Composting. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 12398–12406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Qian, W.; Li, G.; Luo, W. Performance of Mature Compost to Control Gaseous Emissions in Kitchen Waste Composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Romero, S.; Gavilanes-Terán, I.; Idrovo-Novillo, J.; Idrovo-Gavilanes, A.; Valverde-Orozco, V.; Paredes, C. Cheese Whey Characterization for Co-Composting with Solid Organic Wastes and the Agronomic Value of the Compost Obtained. Agriculture 2025, 15, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Dong, G.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, C.; Wu, H.; Guo, C.; Zhang, H.; Han, Y. Product Maturation and Antibiotic Resistance Genes Enrichment in Food Waste Digestate and Chinese Medicinal Herbal Residues Co-Composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 388, 129765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Du, G.; Wu, C.; Li, Q.; Zhou, P.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Z. Effect of Thermophilic Microbial Agents on Nitrogen Transformation, Nitrogen Functional Genes, and Bacterial Communities during Bean Dregs Composting. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 31846–31860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, R.; Malińska, K.; Marfà, O. Nitrification within Composting: A Review. Waste Manag. 2018, 72, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A. Phytotoxicity and Heavy Metals Speciation of Stabilised Sewage Sludges. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 108, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Gu, J.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D. Influence of Aeration on Volatile Sulfur Compounds (VSCs) and NH3 Emissions during Aerobic Composting of Kitchen Waste. Waste Manag. 2016, 58, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Cheng, H.; Luo, Y.; Oh, K.; Meng, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, N.; Chang, M. Seedling Establishment Test for the Comprehensive Evaluation of Compost Phytotoxicity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G.; Li, W.; Tan, W.; Bao, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhu, L.; Chen, L.; Xi, B. Effect of the Aqueous Phase from the Hydrothermal Carbonization of Sewage Sludge as a Moisture Regulator on Nitrogen Retention and Humification during Chicken Manure Composting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Fan, B.; Chang, R.; Chen, Q. Effects of Chemical and Clay Mineral Additives on Phosphorus Transformation During Cow Manure and Corn Stover Composting. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Dang, Q. Regulating Method of Microbial Driving the Phosphorus Bioavailability in Factory Composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 387, 129676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Li, R.; Qu, H.; Wang, P.; Fu, J.; Gong, Y.; Chen, M. Effects of Expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene Porous Membrane Covering and Biochar on Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Contents in Aerobic Composting. BioResources 2024, 20, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, R.; Li, L.; Zheng, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Bao, Z.; Yin, Z.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. A Global Meta-Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Carbon and Nitrogen Losses during Livestock Manure Composting: Influencing Factors and Mitigation Strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 885, 163900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.