1. Introduction

Frequent droughts driven by global climate change pose a severe threat to the sustainable development of dryland agriculture, significantly increasing the risks and uncertainties in agricultural production in arid regions. This highlights the critical need for high-precision crop yield prediction [

1]. As China’s staple crop, maize constitutes 39% of the national grain output and sustains 120 million people in the arid Loess Plateau. Yet FAO estimates drought reduces its yield by 15–22% annually [

2]. Traditional yield estimation relies on inefficient manual sampling (>30 min per plot) and poor spatial generalization [

3], making it inadequate for precision agriculture under climate change [

4]. Developing a remote sensing and machine learning-based yield model is therefore essential for optimizing water and fertilizer use and ensuring food security [

5].

In recent years, UAV-based multispectral remote sensing—characterized by high spatiotemporal resolution (centimeter-scale) and operational flexibility—has been widely applied to monitor crop growth and estimate yields. Compared to satellite remote sensing, UAVs can better penetrate cloud cover, enabling the capture of fine-grained agricultural details and increasing effective observation frequency by 3–5 fold [

6]. Zhou et al. (2023) [

7] reported that UAV imagery provides 47% higher spatial detail density than Sentinel-2 data, significantly improving maize yield prediction accuracy (R

2 = 0.88 vs. 0.63). Commercial platforms such as the DJI Mavic 3M include a red-edge band (730 ± 16 nm), which accounts for 82% of leaf nitrogen accumulation and offers new insight into yield formation mechanisms [

8]. Concurrently, integrating machine learning with UAV data has advanced crop yield prediction [

9]. Research shows that UAV-based machine learning models effectively predict yields across various crops, supporting precision agricultural management [

10,

11].

In remote sensing data processing, machine learning offers distinct advantages, primarily due to its adaptability to high-dimensional and multicollinear data. Fan, J et al. (2023) [

12] verified that random forest (RF) models integrating multi-temporal UAV data can reduce maize yield prediction error to <8%, while gradient boosting (GB) algorithms enhance model generalization by capturing feature interactions [

13,

14]. Interpretable machine learning methods (e.g., SHAP, PDP) have quantified the “threshold plateau” response of vegetation indices, offering a theoretical basis for optimizing agronomic measures. Meanwhile, deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), excels in early and accurate pest and disease detection from high-resolution imagery, further advancing intelligent agriculture.

From the perspective of remote sensing features, vegetation indices—key variables in spectral remote sensing—excel in yield prediction because they serve as quantitative carriers of spectral information, sensitively capturing crop physiological status. For instance, the Modified Simple Ratio (MSR) exhibits a strong correlation with maize kernel number (R

2 = 0.91), the Ratio Vegetation Index (RVI) can diagnose the biomass accumulation threshold during the jointing stage [

15], and red-edge-derived indices (e.g., CLgreen) show greater robustness than the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) under drought stress [

11]. Machine learning algorithms further unlock data value by mining nonlinear relationships between these features and yield.

Two competing theories highlight the uncertainty of optimal remote sensing monitoring windows:

Heading-Dominant Theory: Highlights the core value of canopy spectral information during the critical window of transition from vegetative to reproductive growth (e.g., VT stage, heading stage). Maimaitijiang et al. (2020) [

16] confirmed that canopy spectra acquired during this period achieve peak explanatory power for maize yield, underscoring their prominent role in prediction models.

Maturity-Dominant Theory: Focuses on the strong correlation between remote sensing features near the physiological maturity stage (e.g., R6 stage) and final yield. Zhou et al. (2023) [

7] found through rigorous analysis that R6 stage features have the most significant correlation with maize yield, indicating that maturity-stage information is irreplaceable for accurately capturing yield formation outcomes. The coexistence of these two theories emphasizes the need to clarify the optimal remote sensing monitoring window to improve prediction accuracy [

17].

Additionally, the in-depth application of spatial statistical methods provides a new perspective for analyzing yield variation drivers.

Fowler et al. (2024) [

18], using spatial autocorrelation analysis (Moran’s I), demonstrated that the spatial distribution pattern of high-yield zones (“high-high” clusters) within maize fields is statistically significantly associated with the spatial heterogeneity of soil organic matter (I = 0.62,

p < 0.01). This finding strongly supports that the spatial pattern of basic soil fertility is a core driver of spatial yield variation.

In summary, the current field of maize yield prediction faces three key unresolved issues:

The current research faces three main limitations: First, the integration of UAV multispectral and meteorological data remains insufficient, and the accuracy and generalizability of existing models require improvement [

19]. Second, the optimal monitoring window for key growth stages is unclear, with a lack of systematic analysis on the role of remote sensing features across different stages—particularly regarding the timing for monitoring the VT and R6 stages [

20]. Third, spatial statistical analysis lacks depth, as most models ignore spatial dependence in yield between adjacent plots, hindering simultaneous yield prediction and spatial mapping and thus constraining evidence-based precision management decisions [

21].

This study was conducted at the Lifang Dryland Agricultural Experimental Base in Yuci District, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province. Leveraging UAV remote sensing data, ground survey data, and daily meteorological data covering the entire 2024 maize growing season (May–September), we aimed to develop an integrated yield prediction framework. The central hypothesis is that integrating high-resolution UAV multispectral data with daily-scale meteorological variables within a machine learning framework can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of maize yield prediction under drought stress, while also enabling the characterization of spatial yield patterns.

To test this hypothesis, the specific research objectives are as follows:

To construct a maize yield prediction model by integrating UAV multispectral and meteorological data, conduct comparative analyses of multiple machine learning algorithms, and identify the optimal modeling approach.

To use interpretive modeling tools (e.g., SHAP, PDP) to identify key spectral and meteorological variables influencing maize yield and analyze their contributions to model outputs.

To evaluate the role of remote sensing features during key growth stages (seedling, flowering, jointing, maturity) in yield prediction and determine the optimal monitoring window.

To generate a spatial yield distribution map based on the optimal model, analyze yield spatial clustering using Moran’s Index and multidimensional statistics, and thereby provide quantitative support for precision agronomic decisions (e.g., targeted improvement of low-yield zones).

As a detailed case study, the primary contribution of this work lies in the integrated application of a UAV–meteorological–machine learning framework to address the challenges of yield prediction and spatial variability analysis in a drought-prone dryland maize system. This includes the systematic fusion of multi-source data, comparative algorithm evaluation enhanced by interpretability tools, and the combined use of spatial statistics to bridge yield prediction with actionable management insights.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

This study was conducted at the Lifang Organic Dryland Experimental Base in Yuci District, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province, China (approximately N 37°51′, E 112°45′). The base is situated in the central region of the Loess Plateau, characterized by a typical temperate continental monsoon climate. The elevation ranges from 767 to 1777 m above sea level. The mean annual temperature is about 9.8 °C, with annual precipitation of around 450 mm concentrated predominantly from June to September. The mean annual sunshine duration is 2000–3000 h, and annual evaporation is 1500–2300 mm. The soil is a loessial soil–loam complex. In the 0–30 cm soil layer, the organic matter content is 17.6 g·kg−1, total nitrogen content is 0.98 g·kg−1, and field capacity is 21% (v/v). This environment represents a typical dryland maize production system in the region.

The study area and its context are illustrated in

Figure 1, which shows (a) the geographic location of Jinzhong City within Shanxi Province and China, (b) the location of the experimental base in Yuci District, Jinzhong City, (c) a satellite image of the Yuci Organic Drought Test Base with the maize experimental field highlighted by a red box, and (d) a topographic map of Jinzhong City showing elevation gradients (519–2555 m), reflecting the drought-prone agricultural setting.

2.2. Research Subjects and Experimental Design

This study focused on maize yield prediction across different growth stages, with the core objective of establishing a multi-source data fusion model for yield prediction that integrates key spectral indices (including vegetation indices) and meteorological factors. Specifically, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) multispectral remote sensing and ground truth sampling were adopted as the primary data acquisition approaches, supplemented by meteorological data, to explore the correlations between spectral indices, vegetation indices, meteorological variables, and maize yield at distinct growth stages. The research workflow is illustrated in

Figure 2.

As outlined in the technical roadmap (

Figure 2), this involved integrated data acquisition, model construction, and spatial analysis. The field-based component of this workflow was implemented as follows.

2.2.1. Study Area and Experimental Field Layout

The field experiment was conducted within a continuous, uniform field of approximately 1 hectare (100 m × 100 m) located at the Lifang Organic Dryland Experimental Base in Yuci District, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province. The study was designed to simulate typical dryland maize production conditions. Therefore, no subdivided plots with differential treatments (e.g., varied irrigation, fertilization, or plant density) were established. A single, uniform set of agronomic practices was applied across the entire field.

2.2.2. Crop Cultivation and Management Practices

The locally adapted, drought-tolerant maize (Zea mays L.) cultivar ‘Chengxin 16’ was sown in spring 2024. A uniform planting geometry was maintained with a row spacing of 45 cm and a plant spacing of 15 cm. A basal compound fertilizer was applied in a single dose at sowing at a rate of N:P2O5:K2O = 12:10:8 kg·ha−1; no additional top-dressing was performed throughout the season. The crop relied entirely on natural precipitation, with no supplemental irrigation. Weed control was performed manually at the seedling stage to eliminate potential confounding effects of herbicides on crop spectral signatures. Key phenological stages (emergence, jointing, flowering, and maturity) were recorded.

2.2.3. Ground-Truth Yield Sampling Strategy

A systematic random sampling strategy was implemented at physiological maturity to obtain the target yield variable for model development and validation. Eighteen representative sampling quadrats, each measuring 1 m2 (1 m × 1 m), were established. The sampling locations were strategically designed to capture the primary sources of spatial heterogeneity within the field: (i) along the predominant north–south elevation gradient, (ii) across the east–west transition in soil texture, and (iii) proportionally across areas pre-classified from initial UAV imagery as having high, medium, and low vegetation vigor. To ensure spatial independence, all quadrats were spaced at least 5 m apart

The representativeness of this sampling design was validated by comparing the coefficient of variation (CV) of yield from the sampled plots (12.3%) with the field-scale yield CV estimated from UAV-derived vegetation indices (11.8%), confirming its adequacy in capturing the overall field variability (sampling point distribution is shown in

Supplementary Figure S1).

Maize plants from each georeferenced quadrat were harvested on September 25, 2024. Plants were air-dried to constant moisture, manually threshed, cleaned, and weighed. The grain weight from each quadrat was converted to dry yield per unit area (kg·ha−1) to serve as the ground-truth target variable.

2.2.4. Auxiliary Data Collection

Daily meteorological data, including air temperature (mean, maximum, minimum), precipitation, relative humidity, and sunshine duration, were collected from a small weather station within the experimental site throughout the growing season (May–September 2024).

2.3. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.3.1. Collection and Processing of Multispectral Data

During the 2024 maize growing season (May to September), the study systematically collected multispectral data at four key phenological stages-emergence, jointing, tasseling, and maturity-using a DJI Mavic 3M drone(DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen China). The flight altitude was set at 65 m, with operations carried out in clear weather between 10:00 and 12:00. The forward and side overlap rates were set at 70% and 80%, respectively, to ensure georeferencing accuracy. The drone’s four-channel spectral imaging system captured data in the red (650 ± 16 nm), green (560 ± 16 nm), red-edge (730 ± 16 nm), and near-infrared (860 ± 26 nm) bands. The onboard sunshine sensor was enabled for all flights to record ambient light conditions. Radiometric calibration was performed using a 0.5 m 1 m standard gray panel. Images of the panel were captured under full sunlight with minimal shadows at approximately 7–8 m above ground, both before and after each flight. Calibration was conducted using dedicated UAV multispectral image processing software (e.g., DJI Terra/Smart Agriculture platform), where the known reflectance of the panel was used to convert raw digital numbers to surface reflectance. This process minimized sensor response variations and illumination fluctuations, reducing spectral data variability by approximately 15–20% and enhancing the reliability of subsequent vegetation index calculation and yield modeling. Data were stitched and orthorectified using DJI Terra software (V4.2.5), and radiometric calibration was performed based on a 0.5 × 1 m standard gray panel. Subsequently, ArcMap was used to extract spectral reflectance data from each band, providing the basis for vegetation index calculation.

2.3.2. Measurement of Maize Yield Data

Following the design in

Section 2.2.2, maize plants from each of the eighteen georeferenced quadrats were harvested on 25 September 2024. The plants were air-dried to a constant moisture content, manually threshed, cleaned, and weighed. The grain weight from each quadrat was converted to dry yield per unit area (kg·ha

−1). This dataset served as the ground-truth target variable for model training and validation.

2.3.3. Meteorological Data Collection

Daily meteorological data were collected from an on-site automated weather station throughout the maize growth period (May–September 2024). The variables included: daily mean, maximum, and minimum air temperature (°C) at 2 m height, daily cumulative precipitation (mm), daily mean relative humidity (%), daily mean wind speed at 2 m height (m/s), and sunshine duration (h). To align with the phenology-based structure of the remote sensing data, these daily variables were aggregated by growth stage (seedling, jointing, flowering, and maturity). For each stage, the mean values of temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and sunshine duration, and the cumulative sum of precipitation were calculated. These stage-aggregated meteorological variables were then paired with the corresponding UAV-derived spectral features and vegetation indices for each quadrat, forming the integrated feature set for model training.

2.3.4. Meteorological Data Processing for Model Input

The raw daily meteorological data were processed to create features aligned with the phenological stages of maize. For each of the four key growth stages (seedling, jointing, flowering, maturity), the following aggregations were performed: daily mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures were averaged to produce stage-mean temperature variables; precipitation was summed to yield stage-cumulative precipitation; and relative humidity, wind speed, and sunshine duration were averaged to create their respective stage-mean values. These stage-aggregated meteorological variables were then paired with the UAV-derived spectral features from the corresponding growth stage for each quadrat, forming an integrated feature set for model training.

2.4. Calculation of Vegetation Indices

Vegetation indices quantify canopy spectral characteristics, indirectly reflecting key physiological processes such as crop photosynthetic efficiency, nitrogen accumulation, and biomass formation, which have significant synergistic effects with yield components. Given the differences in sensitivity of various vegetation indices to specific agronomic traits, this study used the multispectral sensor channels of the UAV to establish 16 major vegetation indices (NDVI, RDVI, NLI, GNDVI, RVI, SAVI, NDGI, DVI, OSAVI, GI, MSR, GRVI, CLgreen, WDRVI, TVI, NDWI) [

22,

23,

24] to identify the optimal yield monitoring indicators. Details are shown in

Table 1.

2.5. Model Construction and Evaluation

This study systematically constructed eight machine learning regression models for maize yield prediction, including Lasso regression, Ridge regression, Elastic Net, Random Forest, Multilayer Perceptron, Support Vector Regression, Gradient Boosted Trees, and Linear Models. The modeling dataset comprised 18 independent samples, each corresponding to a georeferenced 1 m

2 quadrat. The input features consisted of the (1) four raw spectral band reflectances (Red, Green, Red-edge, NIR), (2) sixteen vegetation indices calculated from them (

Table 2), and (3) six stage-aggregated meteorological variables: mean temperature, maximum temperature, minimum temperature, cumulative precipitation, mean relative humidity, and sunshine duration for each of the four key growth stages.

To mitigate the risk of overfitting, given the limited sample size and to ensure a robust evaluation, a repeated 5-fold cross-validation framework was employed at the quadrat level. In each fold, 14–15 quadrats (about 80%) were used for training and 3–4 quadrats (about 20%) for testing, ensuring that no data from the same quadrat appeared in both training and test sets simultaneously. This approach prevents information leakage that could arise from pixel-level splitting within the same quadrat and provides a more reliable estimate of model generalization. Hyperparameters were optimized via grid search within this cross-validation loop. Model performance metrics (R2, RMSE, MAE) were averaged across all folds and repetitions to ensure the reported results reflect model stability and generalization capability.

The spatial independence of sampling quadrats (spaced ≥5 m apart) and the use of quadrat-level cross-validation also help to mitigate the influence of spatial autocorrelation. Additionally, ensemble methods such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting are inherently robust to correlated features and spatial structure due to their bootstrap aggregation and random feature selection mechanisms.

Model performance evaluation metrics included the coefficient of determination (R

2), root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) (Formulas (1)–(3)) to comprehensively assess prediction accuracy and stability.

2.6. Variable Importance Analysis

To analyze the explanatory power and influence of input variables in the optimal yield prediction model, we employed two interpretability methods on the best-performing Random Forest model. First, the SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) method was used to interpret the model’s predictions by calculating the average marginal contribution of each feature to the output, thereby identifying key variables. Second, the PDP (Partial Dependence Plot) method was applied to plot the partial dependence of predicted yield on individual variables, revealing the marginal effect of each feature while holding all other variables at their average values.

2.7. Implementation Platform and Dataset Details

All modeling and analysis were implemented in Python 3.9 using the scikit-learn (v1.2.2), SHAP (v0.41.0), and matplotlib (v3.6.3) libraries. Data preprocessing and geospatial processing were conducted using ArcMap 10.8 and GDAL tools. The deep learning component, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), was implemented using TensorFlow (v2.11). All computations were performed on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU running Windows 11 64-bit.

3. Results

3.1. Model Validation and Evaluation

To comprehensively assess the performance of each model in maize yield prediction, this study uses three statistical indicators—coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE)—to analyze the results of the test set.

Figure 3 shows the yield prediction results of 8 regression models. The R

2 of the linear models (Linear, Lasso, Ridge, ElasticNet) are all below 0.1, with the fitted lines being almost horizontal (slope < 0.1), indicating that they cannot capture the nonlinear relationship between spectral-meteorological data and yield (e.g., RMSE > 61, predicted values have no significant correlation with measured values).

In contrast, the tree models (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) achieved R2 values of 0.869 and 0.8165, respectively, with fitted line slopes close to 1 (0.6897, 0.6419), data points tightly clustered around the fitted line, and significantly reduced errors (RMSE < 25, MAE < 23), demonstrating strong fitting capability for nonlinear patterns. The performance of MLP and SVR (R2 < 0.27, RMSE > 42) was better than that of the linear models but far inferior to the tree models, possibly due to model complexity or parameters not being well adapted to the data distribution.

It should be noted that the scatter plots in

Figure 3 display the aggregated predicted versus observed yield values from all test folds across repeated cross-validation. Each point represents a single quadrat-level prediction from an independent test set, and the total number of points reflects the pooled predictions from the entire validation process.

In summary, Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Trees are the optimal models for this task, with their advantage stemming from effective modeling of nonlinear relationships in spectral and meteorological data.

To further evaluate the model’s ability to predict maize yield at different growth stages, the yield prediction results were validated separately for the seedling stage, flowering stage, jointing stage and maturity stage. Maize was divided into these four stages for validation and comparison, revealing significant differences in the contribution of features extracted at each growth stage to yield prediction. Among them, features from the jointing stage demonstrated the strongest predictive power, with generally higher model accuracy and an R

2 value significantly better than other stages, R

2 = 0.7161 (

Table 3), indicating that remote sensing and environmental information during this stage best reflect the final yield differences. The predictive ability in other stages was relatively weaker, possibly because the plants had not yet stabilized and yield differences had not fully emerged at those times.

In

Figure 4, the red dashed line denotes the 1:1 line, representing perfect prediction, while the green solid line illustrates the actual model fitting trend. Across stages, the jointing stage exhibits the highest predictive performance, followed by the maturity and flowering stages, whereas the seedling stage shows relatively poor prediction capability (

Table 4).

3.2. Analysis of Feature Variable Importance

To explain the prediction mechanism of the model and identify key features, this study conducted a SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) value analysis on the Random Forest model. SHAP analysis quantitatively assesses the relative importance of each feature and the way it influences the model’s predictions by calculating the contribution of each feature to the prediction results.

3.2.1. Dominant Role of Spectral Features

As shown in

Figure 5, features are ranked by mean absolute SHAP value (horizontal axis), with MSR and RVI being the most important predictors, followed by NLI, Green, and RedEdge. Violin plots show the distribution of SHAP values, where red dots indicate high feature values and blue dots indicate low feature values. Overall, vegetation indices dominate the prediction model compared to individual spectral bands. This plot highlights the top features, which are predominantly spectral indices, and a separate analysis of the contribution of meteorological variables is provided in

Section 3.2.2.

The SHAP swarm plot indicates that MSR, RVI, and NLI are the most influential core features in the model’s predictions, followed by vegetation indices such as Green, RedEdge, and NDVI. This demonstrates that spectral vegetation indices play a key role in research objectives such as diagnosing crop growth status, yield prediction, and inversion of physiological parameters.

For MSR, higher index values (red dots) are often associated with positive SHAP values, suggesting that higher MSR values indicate higher yield predictions; RVI exhibits a bidirectional influence pattern: both extremely high feature values (dark red) and extremely low feature values (dark blue) may correspond to positive SHAP values, while the influence of intermediate values is relatively scattered. The SHAP value distribution of NLI shows that high feature values (red) mainly have a positive impact, but there are discrete extreme negative values. This nonlinear relationship reflects the sensitivity of this index at specific growth stages.

The relationship between feature values and SHAP values reveals important patterns-these indices, by integrating multispectral band information, can accurately capture crop photosynthetic activity, canopy structure dynamics, and biomass accumulation, which are directly related to physiological and ecological characteristics tied to prediction targets such as yield formation and stress response, providing key clues for model interpretability.

The physiological interpretation of these key features aligns with fundamental maize growth processes: MSR is strongly correlated with leaf area index (LAI), reflecting canopy light interception and photosynthetic capacity during critical growth stages; RVI serves as a robust indicator of above-ground biomass accumulation, which is fundamental to yield formation; and NLI is sensitive to canopy nitrogen status, governing photosynthetic efficiency and carbohydrate allocation during grain filling. Their high SHAP importance confirms that the model effectively captures these fundamental yield-determining mechanisms.

In terms of spectral bands, vegetation indices such as Green, RedEdge, and NDVI show significant influence, with the RedEdge band exhibiting a clear nonlinear effect—its high values (red dots) are associated with positive SHAP values, reflecting the close relationship between red-edge reflectance, chlorophyll content, and crop health status. It is noteworthy that most features display a wide distribution of SHAP values, with both positive and negative impacts, indicating that the effect of a feature on yield is influenced by its own value and interactions with other features, highlighting the complexity of maize yield formation.

3.2.2. Complementary Contribution of Meteorological Variables

Although vegetation indices dominated the overall feature importance ranking (

Figure 5), an independent SHAP analysis was conducted to evaluate the specific contribution of the integrated meteorological variables. The results indicated that precipitation and relative humidity during the jointing and flowering stages were the most influential meteorological predictors (

Supplementary Table S1 and Figure S2). Their positive SHAP values align with agronomic principles, where adequate water availability during these critical periods is essential for yield formation. While the magnitude of their SHAP importance was generally lower than that of the top spectral indices (e.g., MSR, RVI), their inclusion provided complementary information on environmental stress, particularly drought conditions, which may not be fully captured by spectral reflectance alone. This complementary role enhanced the model’s robustness and interpretability within the integrated multi-source framework, especially under the variable climatic conditions of dryland agriculture. Other meteorological variables, such as temperature and sunshine duration, showed lesser direct influence in the final model, likely because their effects on crop physiology were already indirectly expressed through the spectral vegetation indices.

Figure 6 presents the SHAP value distribution for six key features (MSR, RVI, NLI, Green, RedEdge, and NDVI) in maize yield prediction. Each subplot shows the relationship between feature values and SHAP values (model prediction contribution), highlighting the nonlinear impact of these factors on yield. For MSR and RVI, the SHAP values alternate between positive and negative as the feature values change, indicating a bidirectional influence. NLI exhibits a more dispersed effect around 0, reflecting its significant nonlinear characteristics. Green values have an inverse relationship with yield prediction, where low values suppress predictions and high values promote them. RedEdge, with its narrow feature value range, displays more subtle fluctuations in its influence on yield. NDVI primarily contributes positively in the 0.2–0.8 range, with high-value areas (in red) showing a pronounced positive effect on predictions. Furthermore, the SHAP dependence plots reveal both intra-feature and cross-feature interactions, with color dimensions representing secondary features. These insights are crucial for understanding how remote sensing indices affect crop yield, helping to identify key regulatory intervals, and improving both model interpretability and agricultural phenotyping analysis.

3.3. Partial Dependence Analysis

Partial Dependence Analysis (PDP) is a method used to visualize the effect of a single feature on the model’s prediction output, revealing the marginal relationship between the target variable and the prediction result while keeping other variables constant. When performing PDP analysis on six spectral variables with greater influence in the maize yield prediction model (GRVI, NDGI, NDWI, NLI, RDVI, Red band), as shown in

Figure 7, we observe that different variables have significantly different impacts on predicted yield within their respective value ranges, with an overall nonlinear response trend.

For example, in the figure, both GRVI and NDGI show a rapid rise in partial dependence values in low-value ranges (e.g., GRVI < 0, NDGI < 0), producing a positive effect, followed by a wave-like trend. RDVI, in the mid-to-high range (0.2–0.6), and Red band, starting from low values (around 0.1), exhibit more pronounced fluctuations in dependence values. These patterns reflect the crop’s stage-specific response to different vegetation indices and bands: low values trigger positive associations, while mid-to-high values adjust or sustain the influence, highlighting the dynamic characteristics of reflectance effects.

The PDP curves also offer important agronomic insights. For instance, the positive slope of GRVI at low values may correspond to the initial rapid canopy development phase, where increasing greenness is strongly associated with higher yield potential. The plateau observed in NDGI beyond a certain value could indicate a sufficiency threshold for greenness-related traits. Fluctuations in RDVI and Red band dependence reveal varying sensitivities to canopy structure and chlorophyll content across growth stages. These inflection points provide actionable targets for precision agriculture management, such as guiding irrigation or nitrogen application to maintain vegetation indices within optimal ranges.

3.4. Analysis of Spatial Variation Distribution Characteristics of Maize Yield

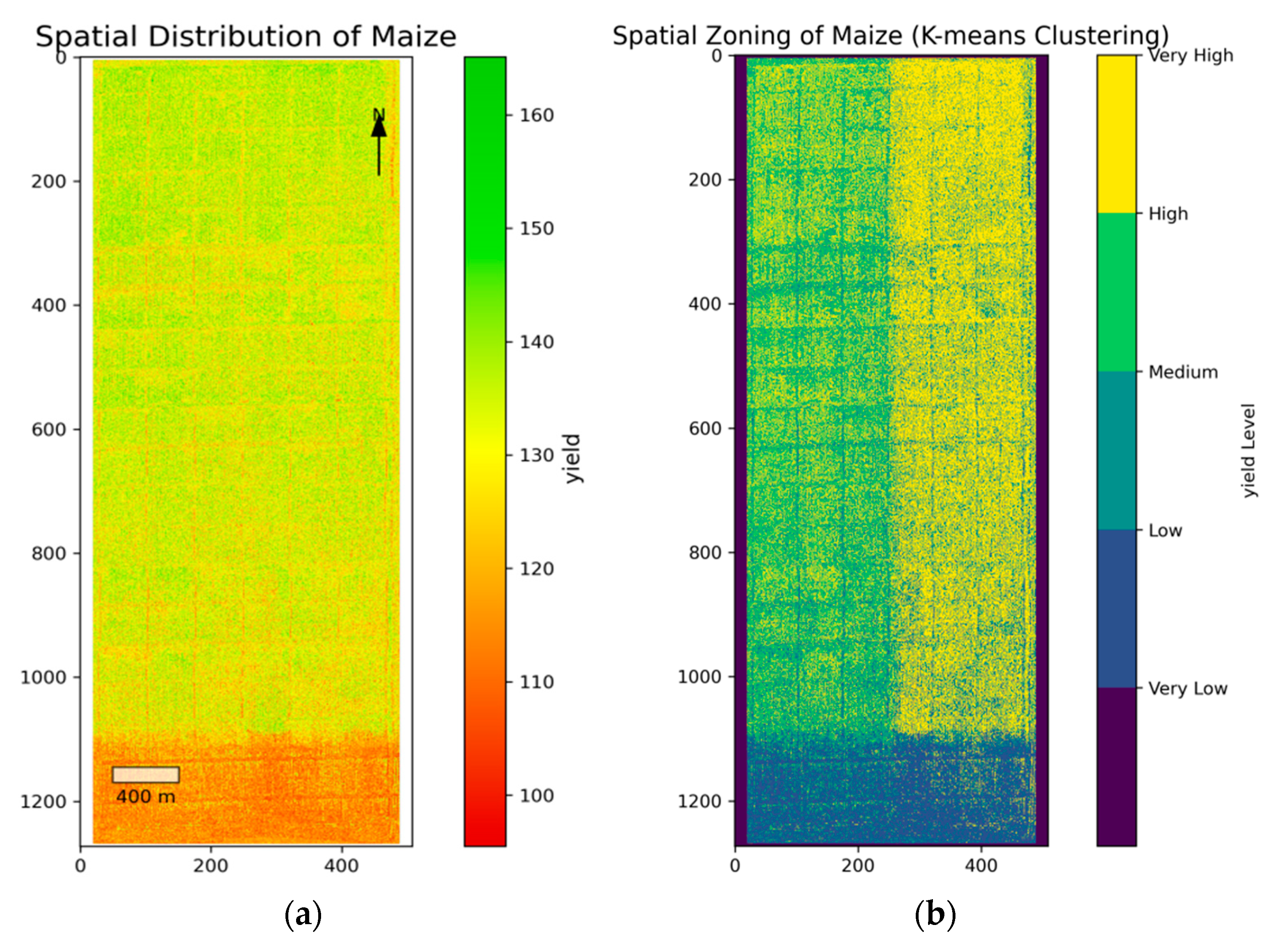

3.4.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Maize Yield

Based on the optimal maize yield prediction model developed earlier, we mapped the spatial distribution of maize yield across the study area. The results reveal clear spatial heterogeneity, with a well-defined distribution pattern. The yield values range from 6450 to 9600 kg ha

−1, showing distinct zones of high yield (green, 8250 to 9600 kg ha

−1) and medium yield (yellow, 7200 to 8250 kg ha

−1), arranged in alternating north–south oriented strip patterns (

Figure 8a). This regular pattern is further confirmed by the yield gradient analysis (

Figure 8b), where higher gradient values (represented by yellow strips) align with the boundaries of yield variation, highlighting the predominant east–west direction of yield differences.

The yield distribution map (

Figure 8a) clearly shows these alternating north–south oriented stripes of high- and low-yield zones. In addition, the spatial zoning map (

Figure 8b) generated through K-means clustering divides the yield into five distinct levels (Very High, High, Medium, Low, and Very Low). The gradual transition from high-yield to low-yield zones along the north–south gradient further underscores the systematic spatial heterogeneity of the area. This detailed zoning provides a solid foundation for implementing precision agriculture strategies tailored to specific yield zones.

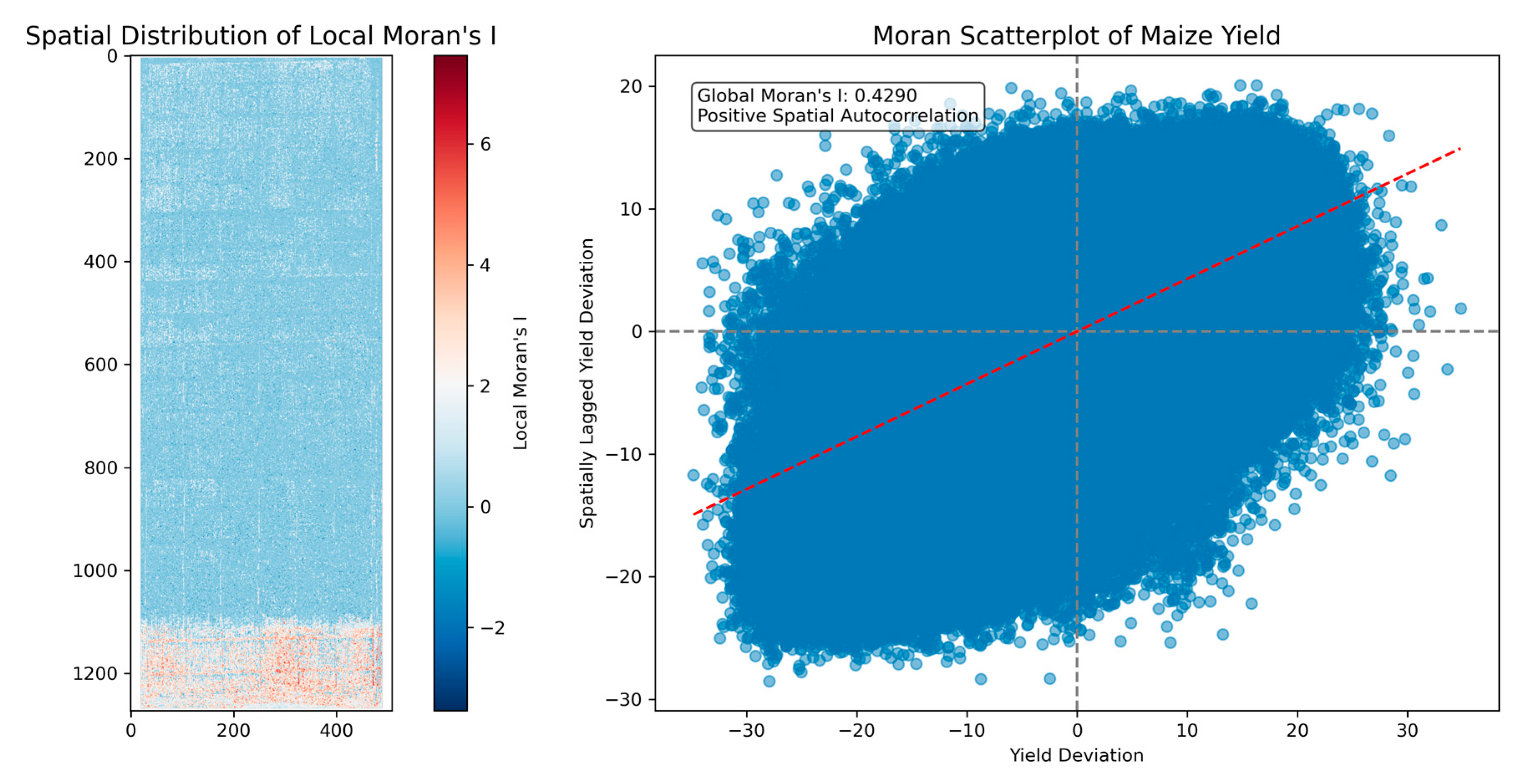

3.4.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Characteristics of Maize Yield

Moran’s I is a widely used spatial autocorrelation statistic that measures the degree of similarity in spatial data, helping to determine whether geographically close observations are similar. This statistic provides insights into whether the study area’s distribution is clustered, random, or dispersed. The results of spatial autocorrelation analysis indicate significant spatial dependence in maize yield across the study area (

Figure 9). The global Moran’s I value of 0.4290 suggests a moderate positive spatial autocorrelation in the yield distribution, meaning that areas with similar yield levels tend to cluster together.

The local Moran’s I spatial distribution map (

Figure 9) highlights a distinct banded pattern of positive spatial clustering (light blue areas), aligning with the earlier observed yield distribution, and reinforcing the spatial structure of maize yield. This clustering is further validated by the Moran scatter plot, which shows that the scatter points are densely clustered in the first quadrant (high yield deviation, high spatial lag deviation) and the third quadrant (low yield deviation, low spatial lag deviation). These clusters represent the “high-high” and “low-low” patterns, indicating spatial transmissibility of yield advantages and disadvantages: high-yield areas tend to form contiguous clusters, while low-yield areas are prone to persistent low yield.

Moreover, the scatter points are tightly distributed along the red trend line, which confirms a significant positive correlation between yield values and their spatial lag values, emphasizing the spatial continuity of high and low yields.

3.4.3. Analysis of the Multidimensional Statistical Distribution Characteristics of Maize Yield

Finally, focusing on the statistical distribution characteristics of maize yield, four major analytical dimensions—frequency distribution, box plot, Q-Q plot, and empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) (

Figure 10)—are integrated to build a multi-perspective quantitative analysis system, covering central tendency, dispersion, distribution shape, and cumulative probability, providing core evidence for precise field management measures:

The frequency distribution histogram shows a left-skewed (negative skew) pattern, with the median (131.14) higher than the mean (130.31), indicating a “long-tail effect” at the low-yield end (frequent extreme low-yield events), reflecting regional low-yield drivers such as heterogeneous soil fertility and drainage obstacles; meanwhile, over 80% of samples are concentrated in the 130–140 kg ha−1 range, highlighting the stability of the medium-to-high yield pattern.

The box plot, through quartiles (Q1/Q2/Q3), whiskers (1.5 × IQR range), and outliers, quantifies yield fluctuations: outliers on the low-yield side mark extreme deviation events, which should be cross-referenced with spatial locations (e.g., field survey points) to investigate causes such as missed machinery application or pest outbreaks, enabling precise remediation of “problem plots.”

In the Q-Q plot, the ordered yield values deviate significantly from the theoretical normal distribution quantile line; combined with the Shapiro–Wilk test (W = 0.9869, p-value 0.0001), the normality hypothesis is clearly rejected. This necessitates the use of non-parametric statistical methods (such as quantile regression) to avoid inference bias in traditional parametric models.

The ECDF shows a steep slope in the 120–140 kg ha−1 range (high proportion of main yields), and gentle slopes at both ends (<110 or >150) (low probability of extreme values). This pattern provides a quantitative basis for yield target setting (e.g., “85% probability of reaching 130”) and agricultural insurance pricing (defining thresholds for extremely low yields).

In summary, this set of plots, through multidimensional statistical analysis, reveals the distribution pattern of maize yield as “stable in the main body, heterogeneous at the tail,” providing quantitative evidence for constructing precise management zones and promoting the transformation of agricultural production from “experience-driven” to “data-driven.”

4. Discussion

This study integrated UAV multispectral and meteorological data to predict maize yield and analyze its spatial variability. Ensemble learning models, particularly Random Forest (R

2 = 0.8696) and Gradient Boosting Trees (R

2 = 0.8163), outperformed linear models, consistent with findings by Zhou et al. [

24] and Kumar et al. [

25], and demonstrated the ability of such algorithms to capture complex nonlinear relationships between crop growth and yield [

26].

SHAP analysis identified vegetation indices as the most influential predictors, with MSR and RVI being the most important. MSR is associated with kernel number accumulation, while RVI effectively reflects biomass thresholds during the jointing stage, aligning with conclusions from Zhang, D. et al. [

27] and van Klompenburg et al. [

14]. This also highlights the value of combining red-edge and near-infrared bands for monitoring maize canopy photosynthesis and biomass status [

28].

In terms of growth stage selection, the jointing stage provided the strongest predictive performance (R

2 = 0.7161), followed by the flowering stage. As a critical transition from vegetative to reproductive growth, the jointing stage involves rapid changes in canopy structure, leaf area index (LAI), and tassel initiation, all closely linked to final yield. Moreover, crops are highly sensitive to environmental stress during this period, making spectral features particularly indicative of yield potential [

29,

30,

31]. This finding is consistent with the viewpoint of Maimaitijiang et al. [

16] and Li et al. [

32] and suggest that monitoring efforts should prioritize key stages such as jointing and flowering [

33,

34].

The present study is based on 18 ground-truth yield samples, which, while limited in absolute number, were strategically distributed to capture the primary sources of spatial heterogeneity within the experimental field (elevation gradient, soil texture transition, and vegetation vigor classes). The sampling design was validated by comparing the coefficient of variation (CV) of sampled yields (12.3%) with the field-scale CV estimated from UAV-derived vegetation indices (11.8%), confirming that the sample adequately represented overall field variability (

Supplementary Figure S1). To mitigate overfitting and provide a robust performance estimate despite the modest sample size, we implemented a repeated 5-fold cross-validation framework at the quadrat level, ensuring that data from the same spatial unit never appeared in both training and testing sets. This approach, combined with the use of ensemble methods (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) that are inherently regularized and less prone to overfitting, allowed us to obtain stable performance metrics (

Table 3). Nevertheless, the sample size remains a constraint for fitting highly parameterized models (e.g., deep neural networks) and for assessing model transferability across seasons and locations. The results should therefore be interpreted as a proof-of-concept demonstration of the integrated UAV-meteorological-ML framework under the specific conditions of the 2024 growing season at the study site.

Spatial analysis revealed a strip-like distribution of maize yield, with a global Moran’s I of 0.4290 indicating moderate positive autocorrelation and distinct “high-high” and “low–low” clusters, providing a spatial basis for precision management [

35]. Yield data followed a left-skewed, non-normal distribution with a long tail at the lower end, suggesting that non-parametric methods such as quantile regression may be more appropriate for subsequent analysis and targeted agronomic intervention [

36].

Some limitations should be noted in this study. Firstly, the data originate from a single site and year (2024), with a limited though representative ground-truth sample size (n = 18). This restricts the assessment of model stability across interannual climate variations and warrants caution against overfitting, despite the cross-validation strategy employed.

Secondly, the model’s input variables are confined to spectral and meteorological data; key soil physicochemical parameters (e.g., organic matter, pH) and detailed field-management records (e.g., irrigation and fertilization timing) are not included. Their omission may constrain a mechanistic understanding of the spatial variability in yield.

Thirdly, the study was conducted in the dryland farming region of Jinzhong, Shanxi. The model’s transferability to other ecological zones—such as the semi-arid Northwest or the black-soil region of Northeast China-remains unverified. As noted by Koutsos et al. [

37], transferring yield-prediction models across different climate regions remains challenging and requires more generalizable approaches. Lobell et al. [

38] further highlighted the need for multi-region, multi-year studies to fully exploit remote-sensing data in yield-gap analysis.

Based on the above limitations, future research should be directed along the following pathways to enhance both scientific understanding and practical utility:

Enhanced data integration and model validation: Priority should be given to conducting multi-year studies and obtaining independent validation datasets from contrasting sites. This is essential for testing model stability and transferability. Furthermore, data fusion should be upgraded by integrating soil sensor data (moisture, nutrients), high-resolution thermal infrared (for stress detection), and radar data (for canopy structure), building a comprehensive “spectral-meteorological-edaphic” input system [

39].

Advanced algorithm development: Moving beyond traditional ML, future work can explore deep learning architectures (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks) to automatically extract spatio-spectral features from raw UAV imagery, and attention mechanisms to better identify key phenological traits (e.g., ear development) during critical stages like jointing [

40].

Generalizable modeling frameworks: To address the “single-location” limitation, transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques should be investigated to efficiently adapt pre-trained models to new environments with limited local data, thereby improving universality [

41].

From prediction to prescription: To maximize practical impact, future efforts should focus on closing the loop between prediction and action. This involves integrating the yield prediction model with farm management systems to enable prescriptive decision support, such as triggering site-specific irrigation or variable-rate fertilization, ultimately realizing a full-chain “sensing–prediction–decision–execution” solution for precision agriculture [

42].

In addition, with the improvement of the spatiotemporal resolution of remote sensing platforms such as Sentinel satellites, exploring the fusion application of high-resolution UAV data with large-area satellite coverage data is expected to achieve the combination of “small-area precision monitoring” and “large-area yield estimation,” providing more comprehensive technical support for regional food security assessment [

43,

44].

5. Conclusions

This study presented an exploratory case study demonstrating the feasibility of a maize yield prediction framework based on the integration of UAV multispectral data as the primary information source with complementary meteorological data. The main findings are as follows:

UAV multispectral data combined with machine learning methods showed indicative potential for predicting maize yield under the studied conditions. Ensemble learning algorithms performed best, with Random Forest (R2 = 0.8696) and Gradient Boosting Tree (R2 = 0.8163) significantly outperforming traditional linear models. They effectively captured nonlinear relationships between spectral data, meteorological data, and yield, suggesting a promising methodological approach for high-precision maize yield prediction.

Vegetation indices derived from multispectral data emerged as the dominant predictors. Feature importance analysis identified MSR and RVI as key vegetation indices, reflecting kernel number formation and biomass accumulation processes. The combination of red-edge and near-infrared bands proved valuable for monitoring maize growth status, as different vegetation indices captured various physiological characteristics linked to final yield.

Under the specific conditions of the 2024 season at our study site, the jointing stage provided the strongest predictive power for maize yield (R2 = 0.7161), suggesting its potential as a key monitoring window in similar drought-affected environments. Remote sensing data during this critical transition period captured information relevant to both vegetative and reproductive growth.

Maize yield exhibited significant spatial patterning, with a clear strip-like distribution supported by a global Moran’s I of 0.4290, indicating moderate positive spatial autocorrelation. Multidimensional statistical analysis confirmed the non-normal, left-skewed distribution of yield data, providing a preliminary quantitative basis for delineating precision management zones.

While spectral features were the primary drivers of predictive accuracy, the integration of growth-stage-aggregated meteorological variables, particularly precipitation and relative humidity, provided complementary information on drought stress within the multi-source assessment framework.

In summary, this research provides a proof-of-concept for a field-scale maize yield prediction and spatial analysis framework under dryland conditions. However, it is crucial to emphasize that the framework’s development is based on a single-year dataset from a specific location and the ground-truth sample size (n = 18), while representative, was constrained by practical sampling feasibility. Therefore, the study is primarily exploratory and demonstrative in nature. The immediate operational applicability of the presented models to other regions or seasons is limited. The findings underscore the potential and feasibility of integrated UAV–meteorological–machine learning approaches but also highlight the critical necessity for future validation across multiple years and diverse agroecological environments with larger datasets to confirm robustness, generalizability, and progress towards a reliable decision-support tool.