Abstract

Groundwater resources are scarce in the cold and arid regions of north China. Moreover, regional water resource replenishment without external sources remains difficult. This water deficit has become a major factor restricting the sustainable development of regional vegetable production. The effective utilization of rainwater harvesting for irrigated agricultural production is necessary to suppress droughts and floods in farming under the semi-arid climate of this area in order to both guarantee a stable supply of vegetables to the market in south and north China and promote the balanced development of regional agriculture–resource–environment integration. In this study, based on continuous simulation and Python modeling, we simulated and analyzed the water supply and production effects of irrigation with harvests and stored rainwater on tomatoes under different water supply scenarios from 1992 to 2023. We then designed and tested a water-saving and high-yield project for rainwater-irrigated greenhouses in 2024 and 2025 under natural rainfall conditions in northwestern Hebei Province based on the reference irrigation scheme. The water supply satisfaction rate, water demand satisfaction rate, and volume of water inventory of tomato fields under different water supply scenarios increased with the rainwater tank size, and the corresponding drought yield reduction rate of tomato decreased. Under the actual rainfall scenarios in 2024 and 2025, a 480 m2 greenhouse with a 14.4 m3 rainwater tank for producing tomatoes irrigated with rainwater drip from the greenhouse film collected 127.7 and 120.5 m3 of rainwater, respectively. The volume of the rainwater tank was exceeded 8.3 and 8.0 times, and up to 93.8% and 95.0% of the irrigated groundwater was replaced; additionally, the average yield of the small-fruited tomato ‘Beisi’ was 50,076.6 kg·hm−2 and 48,110.2 kg·hm−2, reaching 96.1% and 92.3% of the expected yield. Conclusion: The irrigation strategy based on the innovative “greenhouse film–rainwater harvesting–groundwater replenishment” model developed in this study has successfully achieved a high substitution rate of groundwater for greenhouse tomato production in the cold and arid regions of north China while ensuring stable yields by mitigating drought and waterlogging risks. This model not only provides a replicable technical framework for sustainable agricultural water resource management in semi-arid areas but also offers critical theoretical and practical support for addressing water scarcity and ensuring food security under global climate change.

1. Introduction

In the context of global warming and frequent droughts and floods, farmland production in semi-arid areas is becoming increasingly more vulnerable and inefficient; thus, the demand for groundwater development for irrigation to stabilize crop yields and improve economic returns is also increasing [1]. However, profit-driven uncontrolled irrigation water consumption and the consequent slow onset of hydrogeological disasters, such as groundwater-level decline, have intensified regional water scarcity and ecological hazards [2,3]. Water resources are extremely scarce in China, and the wide variability in rainfall quantity and spatial and temporal distribution directly affects agricultural production. It has been reported that 61.2–63.6% of water resources are used for farmland irrigation across all of China [4], and the proportion is as high as 69.0–70.1% in north China. In this region, the area of arable land affected by drought or flooding still accounts for 2.5–50.2% of the area each year, resulting in crop yield reductions of 2.6–50.0% [5]. Therefore, stable and efficient water resource supply and sustainable water resource renewal are common issues facing agricultural progress in China and the many semi-arid regions of the world.

Located along the Great Wall, the alpine semi-arid region of north China, with more than 100 years of agricultural history, has experienced a loss of farmland to wind and water erosion, causing a continuous decline in the productivity of agriculture and forage production along with ecological disasters of sand and dust storms [6]. Into the 1990s, the development of cool-season vegetable production further exacerbated the tension between the supply and demand of regional water resources. In Hebei Province, a largely alpine semi-arid region, the year-round vegetable planting area of more than 40,000 hm2 spans about 25% of the arable land area [7]; to alleviate drought stress on crop production, the regional annual exploitation of groundwater of about 220 million m3, over-exploitation of about 50 million m3, accounted for 85.0% of water use in Hebei [8]. Therefore, technological innovations in replacing groundwater with regional precipitation and balancing the groundwater extraction–replenishment equilibrium have become essential to meeting the demand for sustainable water supply and ecological security in the hinterland of north China [9,10,11].

The construction of a rainwater harvesting and utilization system (RWHUS) [12,13,14] can directly promote and realize rainwater resource utilization, calm drought stress, and reduce the pressure of groundwater extraction in the ground–soil–plant–atmosphere continuum (GSPAC) water cycle [13]. Meanwhile, guiding rainwater flow in the field has the effect of reducing both soil erosion by water and the indirect effect of surface evaporation. In addition, the discharged rainwater supplies groundwater through its infiltration, which can effectively restore the hydrological cycle of agricultural fields and alleviate ecological problems such as ground subsidence caused by the over-exploitation of groundwater resources [15]. In the urban region of Islamabad, Pakistan, which has a humid subtropical climate, the use of both building roof rainwater harvesting systems and harvested rainwater for garden irrigation resulted in water-saving efficiencies and time reliability of 84% and 88%, respectively [16]; additionally, the use of ridge and furrow rainwater harvesting in combination with supplemental irrigation in fields in a temperate semi-arid climate increased potato, wheat, and maize yields by 56.2–109.2% with increases in water use efficiency of 1.1–17.8% [17,18,19,20]. Therefore, the supplemental irrigation of rainfed crops using a RWHUS has been widely recognized as a key strategy to minimize the risk of drought-induced crop failure and plays an important role in agricultural development in semi-arid areas [21]. However, relatively few studies have been conducted on the water supply effects of rainwater harvesting, storage and irrigation agriculture, which utilizes rainwater harvesting to replace or partially replace groundwater for irrigation in conjunction with crop irrigation schemes, particularly in terms of rainwater tank size, disaster mitigation and yield stabilization, irrigation supplementation, and yield enhancement. This study takes greenhouse tomato production in the Bashang cold and arid region of north China as its research subject. By applying the principle of dynamic water balance, it establishes a tank capacity—a water supply effect model for greenhouse tomatoes under the combined system of rainwater harvesting–storage and groundwater irrigation, and equipped it with a climate-resilient dynamic regulation strategy of “early overflow irrigation and supplemental watering during water scarcity”. This enables the production system to proactively manage extreme drought and flood events, transforming volatile climate risks into manageable production factors. Meanwhile, this study applied a model to simulate and analyze the water supply effect and influencing factors of the greenhouse tomato rainwater harvesting system based on a reference irrigation scheme under different 25-year precipitation scenarios, and it practiced the greenhouse film rainwater harvesting–water storage irrigation greenhouse tomato stable yield project. This study aims to provide practical knowledge and strategic support for technological innovations in utilizing precipitation resources, mitigating drought and waterlogging stress, substituting groundwater irrigation with rainwater, and promoting the sustainable renewal of water resources while also offering technical directions for the deeper application of digital agriculture in water resource management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

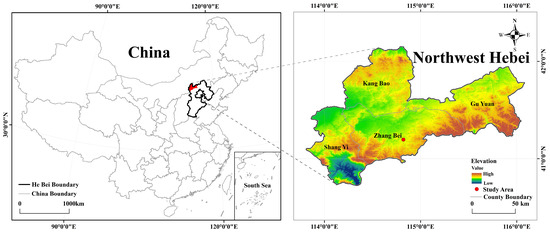

The experiment was conducted in 2023–2025 at the Zhangbei Key Field Observation Experiment Station of Agricultural Resources and Ecological Environment of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (114°42′ E, 41°09′ N) on the Bashang Plateau of Hebei Province, China, which had an alpine semi-arid continental monsoon climate zone typical of north China. The test area was at an altitude of 1420 m a.s.l. The average annual rainfall was 382.5 mm, the growing season (1 May to 30 September) received approximately 300 mm of precipitation, and the coefficient of variation in interannual rainfall was 28%; the potential evapotranspiration was 804.1 mm. The regional average annual temperature was 3.9 °C, with a frost-free period of 130 d and ≥10 °C cumulative temperature of 2426.3 °C·d, and the annual average number of hours of sunshine was 2900 h [22]. The regional inter-seasonal dry and wet differences were obvious; rain and heat were synchronized with crop fertility, and low temperature and drought were the main limiting factors for crop production. During the study period, the precipitation in the 2023 crop growing season (1 May to 30 September) was 201.7 mm, characterizing a relatively dry year; while the figures for 2024 and 2025 were 525.3 mm and 666.0 mm respectively, which were both classified as extremely wet years. The location of the study area is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

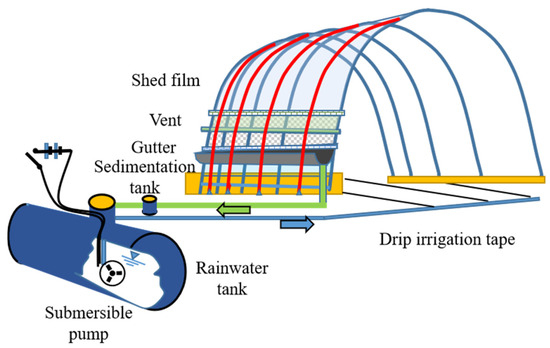

2.2. Rainwater Harvesting and Utilization System

This study evaluated a plastic greenhouse tomato production system as its research object with the water demand of tomato fields met through rainwater harvesting from the greenhouse film and its storage combined with supplemental groundwater irrigation. The rainwater harvesting and utilization system for the greenhouse area is depicted in Figure 2. It primarily consists of three components: rainwater harvesting facilities, a rainwater tank, and a reuse system for greenhouse crop irrigation. The standard greenhouse for the system is 60 m long and 8 m wide with a rainwater harvesting area of 480 m2, while the size of the rainwater harvesting tank in the test area is 14.4 m3. Galvanized steel sheet harvesting gutters, fixed along both sides of the greenhouse structure, were installed with a gradient of 2‰.

Figure 2.

Greenhouse rainwater harvesting, storage, and utilization system. Note: The green arrow indicates the direction of rainwater flow toward the tank, while the blue arrow shows the direction of stored rainwater used to irrigate greenhouse tomatoes.

2.3. Data and Methods

2.3.1. Test Crops and Soil

The greenhouse tomatoes were planted according to the cultivation mode of ridging the soil and covering it with black film, and the variety for the test was small-fruited ‘Beisi,’ which were obtained from a nursery before being planted once they each had six leaves. Transplantation occurred on 9 May 2024, while the harvest was finished on 1 October 2024. The ridge spacing of the greenhouse tomatoes was 140 cm, and two rows were planted in each ridge, with 40 cm row spacing and 45 cm plant spacing within rows; three drip irrigation strips were laid per ridge.

The soil in the study area is a shallow sandy chestnut calcium soil with a coarse texture and poor water and fertilizer retention capacity. The 0–20 cm soil layer had an organic matter content of 21.3 g·kg−1, while the contents of alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium were 103.9, 19.1, and 93.2 mg·kg−1, respectively. The soil pH was 7.32. The soil moisture physical properties are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Soil moisture physical properties of the tested soil.

2.3.2. Parameter Selection

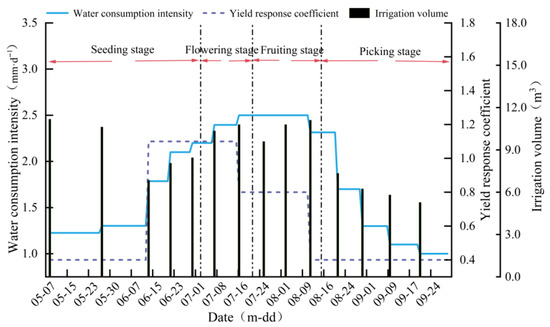

Based on the results of a study on the effects of different irrigation gradients (60%, 70%, 80% of the field water capacity) on the temporal and spatial water consumption characteristics, yield, and water-use efficiency of greenhouse tomato fields in the water-saving irrigation experiment at Zhangbei Experimental Station from 2023, 80% of soil field water capacity was chosen as the reference irrigation scheme (Figure 3). The tomato field required 14 rounds of irrigation totaling 122.5 m3 during the reproductive period; the yield of small-fruited ‘Beisi’ tomato under the reference irrigation scheme was 52,096.1 kg·hm−2.

Figure 3.

Irrigation requirements, water consumption intensity, and yield response coefficients (Ky) at different growth stages of ‘Beisi’ tomato.

In this study, the yield response coefficients (Ky, Figure 3) recommended by the FAO for different fertility stages of tomato [23] were used to evaluate the extent of the effect of drought stress on tomato yield in each period, which represents the proportion of yield reduction per unit reduction in water demand relative to maximum (non-stressed) conditions.

2.3.3. Model Construction and Simulation Analysis

This study was based on the principle of dynamic water balance [24]: that is, the temporal balance between the water demand of crops and rainwater harvesting and storage–groundwater supply in accordance with the principle of water supply priority. Python 3.11.x was used for programming, primarily utilizing the pandas and numpy libraries for data processing and numerical calculations, along with the datetime module for date processing. In this model, the determinants of rainwater volume dynamics include daily rainfall, rainwater harvesting surface area, rainwater tank size, rainwater harvesting inventory and overflow, irrigation demand, and groundwater supplements during storage shortages. The rainwater harvesting volume, water deficit, water discharge and inventory volume, water demand satisfaction rate, groundwater replacement rate, and yield reduction rate were used as indicators for assessing the irrigation effect of rainwater storage in tomato fields in this model.

Based on the extremely unstable characteristics of rainfall in the monsoon climate of the study area, this study simulated and compared 3 rainwater tank sizes and the effect of rainwater storage and irrigation in tomato fields under three rainfall scenarios: (1) the multi-year average rainfall scenario, based on the day-by-day average daily rainfall for the 25 years with complete rainfall data from the Zhangbei meteorological station during 1992–2023; (2) 80% guarantee rate of sub-annual rainfall (80% GRSR); and (3) the actual rainfall values in 2024 and 2025.

Based on the geological and geomorphological environments in the study area and the diversity of farmers’ operating practices, this study simulated and compared the effect of rainwater storage and irrigation in tomato fields using three different types of rainwater storage tanks: namely, a simple tank, a galvanized sheet tank, and a fiberglass-reinforced plastic (FRP) tank with corresponding economic tank sizes of 14.4, 9.7, and 4.8 m3, respectively [25]. The economic tank size is determined as the tank size where the combined costs of constructing water storage facilities and partially extracting groundwater equal the total cost of relying solely on groundwater extraction. Meanwhile, constructing water storage facilities with varying tank sizes can effectively reduce groundwater extraction.

The simulations were conducted utilizing the following equations.

- Rainwater harvesting volume (m3):

Q = C × H × Ψ × 0.001

- Water scarcity (m3)

- Water discharge (m3)

The water demand satisfaction rate refers to the ratio of the total rainfall supplied by the rainwater tank to the total water demand over a given period.

- Water demand satisfaction rate (%)

λ = (D − L)/D × 100

- Yield reduction rate of each growth period (%)

Yc = (1 − Wc/Dc) Ky × 100

- Yield reduction over the full growth stage (%)

- Water volume (m3)

Water volume = C (480 m2) × water volume × 0.001 (mm)

The water volume includes the water discharge volume, the water scarcity volume, the water inventory volume and the irrigation volume.

2.3.4. Model Verification and Application

Based on the reference irrigation scheme (Figure 3), the effect of harvested and stored rainwater irrigation on tomato production was demonstrated for the actual rainfall in 2024 and 2025. The experimental greenhouse tomato production area used a 14.4 m3 rainwater tank and real-time monitoring of the rainfall and rainwater tank water storage volume. The irrigation schedule and water volume are determined by utilizing the dynamic water levels of rainwater reservoirs and tomato field irrigation efficiency models, which are guided by the principle of ‘early irrigation during overflow periods and supplemental irrigation during water shortages’, to ensure optimal water supply for productive tomato cultivation.

When tomatoes entered the harvest period, ripe fruits were picked in five areas, and the total tomato production was recorded; the proportion of various types of non-commercial fruits was differentiated and recorded according to their commerciality.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation of Rainwater Storage and Water Supply–Production Effects in Greenhouse Tomato Fields Under Different Supply Scenarios

The water supply–production effects of three different economic rainwater tanks size, with sizes of 14.4, 9.7, and 4.8 m3, and a minimum tank size without water discharge were simulated based on the reference irrigation scenario. The water supply–production effects of irrigation from greenhouse film harvested rainwater on tomato production are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simulation of rainwater storage and water supply–production effects in greenhouse tomato fields under three water supply scenarios with different tank sizes.

Simulations showed that the minimum rainwater tank size for 480 m2 greenhouse tomato field production without water discharge under the scenarios of multi-year average rainfall, 80% GRSR, and actual rainfall values in 2024 were 18.7, 100.3, and 117.1 m3, respectively; even for such high rainwater tank sizes, the tomato field still suffered from water scarcity of 6.6, 14.9, and 3.7 m3, respectively, which resulted in corresponding reductions in tomato yields by 12.5%, 29.1%, and 6.9%, respectively. In the extremely wet year of 2025, characterized by a precipitation of 666.0 mm during the growing season, the rainwater harvesting and storage irrigation system could meet the temporal water demand of the tomato field under a minimum tank size of 154.6 m3 without water discharge. In the multi-year average rainfall scenario, three rainwater tank sizes of 14.4, 9.7, and 4.8 m3 were found to obtain 94.6%, 90.9% and 54.9% groundwater replacement rates, respectively, while accumulating water inventory and discharges equivalent to 1.22, 2.07 and 2.80 times the water scarcity. The rainwater tank size directly determines tomato productivity.

The comparison shows that when the rainwater tank size is 14.4 m3, the water supply satisfaction rate of tomato fields under the scenario of annual average rainfall reaches up to 106.3%, while the water demand satisfaction rate is only 94.6%. The scarcity of water supply for rainfall storage in a period of time leads to a yield reduction of 12.5%. Under the GRSR scenario, the average water supply satisfaction rate and water demand satisfaction rate of the tomato field decreased to 88.3% and 81.7%, respectively, and the corresponding average yield reduction rate increased to 41.4%. In 2024 and 2025, the water supply satisfaction rate reached 100.2% and 106.0%, respectively. But the inconsistency between rainfall and tomato water demand timing and quantity still led to yield reduction rates of 19.7% and 6.9%. The drought stress caused by the extremely unstable inter-annual and inter-seasonal precipitation and temporal distribution significantly restricted tomato productivity.

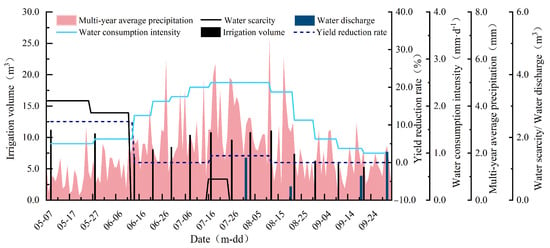

The water supply and production effects of greenhouse tomato fields irrigated with rainwater harvested from greenhouse film under the scenario of multi-year rainfall average values are summarized in Figure 4. The harvested rainfall during the growth period was 126.3 m3; including the rainfall harvested 30 days before transplantation, a total of 134.4 m3 of rainwater could be harvested. Considering the water discharge of 4.1 m3 during the growth period, the water supply satisfaction rate of tomato during the whole growth period reached 106.3%. As a consequence of the size of the rainwater tank (14.4 m3) and the wide variation in rainfall occurrences, there were still three tomato irrigation periods with different degrees of water scarcity. As the harvested rainfall 30 days before transplantation was only 8.0 m3, the water scarcity was 3.2 m3 and 2.8 m3, respectively, from 9 May to 24 and from 25 May to 4 June in the early tomato growth period, requiring supplemental irrigation with groundwater. Later, with the arrival of the rainy season and consequently more frequent rainfall water supply for rain storage, the tomato field water demand satisfaction rate reached 100%, and there was surplus water obtained. From 17 July to 25 July, the water scarcity was 0.7 m3 owing to the decrease in rainfall. Later, with the decreased water consumption intensity of tomato fields, irrigation with harvested rainwater alone met the water demand of tomato in its later stage.

Figure 4.

Simulation of water supply–production effects of irrigation with harvested and stored rainwater on tomatoes under multi-year average precipitation with a 14.4 m3 tank size in a plastic film greenhouse.

Our comprehensive analysis showed (Table 2) that with annual average rainfall and a rainwater tank size of 14.4 m3, the total water scarcity of the greenhouse tomato field in the three periods of the whole growth period was 6.6 m3, and the yield was reduced by 12.5% relative to the expected maximum yield. The sum of water discharge (4.1 m3) and the water inventory (14.4 m3) was much greater than the water scarcity. Therefore, the wide variation in rainfall supply between seasons in the study area, under the regulation of utilizing stored water in rainwater tanks, effectively alleviated the damage associated with excessive rainfall waterlogging, but the water scarcity stress in some periods of time could still cause tomato drought. This is more impactful for tomato yield reduction caused by drought stress in a period of time when the annual rainfall is 80% GRSR, necessitating groundwater supplementation for high-yield tomato production

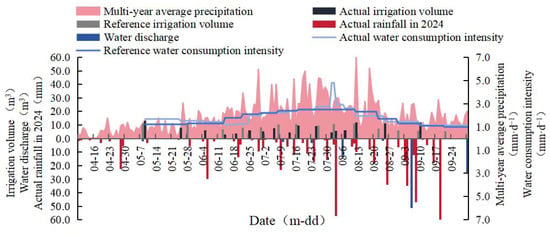

3.2. Effects of Water Supply on Tomato Production Under Greenhouse Film Rainwater Harvesting and the Actual Rainfall in 2024

Modeling the water volume dynamics of rainwater tanks and the irrigation effect of tomato fields, according to the principles of irrigating early to avoid tank overflow and irrigation under water scarcity, we determined the irrigation date and water volume, and we implemented a water supply scheme for tomato fields with high productivity. The irrigation situation and production effect of greenhouse tomato fields under the 2024 precipitation scenario are shown in Table 3 and Figure 5. The total irrigation volume of greenhouse tomatoes in the full growing season was 127.7 m3, while irrigation was applied 17 times in total, with each irrigation application between 2.8 and 12.9 m3, and the average supply irrigation water intensity was 1.8 mm·d−1.

Table 3.

The effects of irrigated tomato production in 2024.

Figure 5.

Precipitation distribution and water supply–demand in greenhouse tomato production in 2024.

The 2024 tomato growth period was characterized by relatively abundant precipitation, totaling 566.6 mm together with the 30 d before transplanting, which was 1.7 times the average multi-year precipitation corresponding to the same period. As the rainwater tank was already full at the time, both the 12th and 13th irrigation applications were advanced in accordance with the rainfall. Table 3 shows that a total of 100.6 m3 of water was discharged nine times during the reproductive period of greenhouse tomatoes, and 14.4 m3 of water remained in the rainwater tank during the harvest period. During the seventeen irrigation applications during the tomato fertility period, only two from 25 May to 13 June used supplementary groundwater, comprising a total volume of 8.0 m3. The comparison with the reference irrigation scheme indicated that irrigating tomatoes with supplemental groundwater through rainwater harvesting from the greenhouse film and storing it for later use completely guaranteed the temporal and quantitative water demand of the tomato field and replaced 93.8% of the groundwater use.

3.3. Effects of Water Supply on Tomato Production Under Greenhouse Film Rainwater Harvesting and the Actual Rainfall in 2025

Under the 2025 precipitation scenario, the irrigation practices and production outcomes for greenhouse tomato fields are presented in Table 4 and Figure 6. The 480 m2 greenhouse tomato field received 10 irrigation events throughout its growth cycle with a total irrigation volume of 120.5 m3 and an average water supply intensity of 1.7 mm·d−1. As shown in Table 4, precipitation during the 2025 tomato growing season was exceptionally abundant, with cumulative rainfall reaching 666.0 mm, including the 30 days prior to transplanting. The total discharge water during the greenhouse tomato growth period amounted to 153.0 m3, while the rainwater tank retained 4.2 m3 of residual moisture at the end of the growing season. By utilizing rainwater harvesting through greenhouse film and supplemental groundwater irrigation, the water requirements of the tomato field were fully met, achieving a 95.0% substitution rate of harvested rainwater for groundwater.

Table 4.

The effects of irrigated tomato production in 2025.

Figure 6.

Precipitation distribution and water supply–demand realities in greenhouse tomato fields in 2025.

3.4. Effectiveness of Greenhouse Tomato Production Under Irrigation with Harvested and Stored Rainwater Under Actual Rainfall in 2024 and 2025

Under the actual rainfall in 2024 and 2025, the tomato yield and commodity characteristics of tomato fields irrigated by rainwater harvested from greenhouse film and supplemental groundwater are shown in Table 5. With greenhouse-grown tomato plants receiving the proper timing and volume of irrigation, the total yields of the cherry tomato ‘Beisi’ in 2024 and 2025 were 50,076.6 kg·hm−2 and 48,110.2 kg·hm−2, respectively, which reached 96.1% and 92.3% of the reference value under a traditional irrigation scheme and thus essentially realized the high yield of tomato. In this harvest, 97.7% fruits were of commercial grade, and the proportion of malformed, cracked, and worm- or insect-damaged fruit was very small.

Table 5.

Yield characteristics of tomato under the actual irrigation scheme in 2024–2025.

Compared with the simulation results for water supply and the production of tomato fields under actual rainfall values in 2024–2025 (Table 5), the yield reduction rate of tomato in actual irrigation practice decreased from 19.7% to 3.9%, owing to 8.0 m3 of timely groundwater supplementary irrigation. The water discharge volume decreased from 107.8 m3 to 100.6 m3, and the stored rainwater volume increased from 9.1 m3 to 14.4 m3 during the corresponding harvest period. In actual irrigation application, irrigation according to rainwater played a key role in reducing the water discharge and increasing the water inventory. The rainwater storage water supply of tomato during the growth period was 119.7 m3, and the rainwater tank size turnover rate was as high as 8.3 times, owing to the synchronization of the rainy season and the water demand of tomato growing in the greenhouse in the study area.

In 2025, despite frequent and abundant precipitation, tomato yield decreased by 7.7% due to insufficient irrigation during the seedling stage (9 May–13 June) and extended intervals between irrigation events (27 July–11 August). During the tomato growth period, the rainwater harvesting and storage system supplied 114.5 m3 of water with a reservoir capacity turnover rate as high as 8.0 times. The production results of rainwater harvesting and storage irrigation demonstrate that greenhouse film rainwater harvesting irrigation, combined with supplemental groundwater irrigation, has achieved a significant substitution of groundwater while maintaining high tomato yields.

4. Discussion

4.1. Utility of Rainwater Harvesting and Utilization Systems for Drought and Flood Protection

As the most critical factors in agricultural food production, water and energy scarcity and depletion have become among the greatest challenges facing the world in the 21st century [26,27]; changes in rainfall scenarios associated with global warming have exacerbated the threat of droughts and floods in crop production, further limiting the availability and productivity of water resources [28]. Sabbaghi et al. [1] used hydrological and agricultural modeling simulations to infer that the water resources of the Zayandrulu River Basin will decrease by 4.3% and 8.1% by 2040 and 2070, respectively, compared to the baseline period with a corresponding onion yield loss of 22.1% to 24.4%. The analysis in the present study shows that in the cold and arid region of north China, according to the multi-year average rainfall scenario simulation of harvesting rainwater from the tomato greenhouse film and using it for irrigation, even though the use of a 14.4 m3 rainwater tank effectively suppressed the wide fluctuation in rainfall timing and volume distribution, the period of water scarcity still allowed the tomato plants to suffer from drought stress and reduced the tomato yield by 12.5%. In the 80% GRSR scenario, which is more similar to the actual production conditions, the tomato yield reduction rate caused by drought stress increased by 41.4%. Production validation under actual rainfall conditions in 2024 and 2025 demonstrated that the rainwater harvesting and storage irrigation method achieved tomato yields equivalent to 96.1% and 92.3% of the reference yield, respectively. This is entirely due to the rainfall control provided by the plastic greenhouses, which transformed the unstable timing and amount of rainfall into a stable irrigation water source through rainwater harvesting, storage, and application. Consequently, this system demonstrates good reproducibility. The utilization of greenhouse facilities effectively mitigates rainfall and flooding [29] and further opens up new avenues for auxiliary rainwater harvesting and water supply [30], which becomes an opportunity for progress in rainfed agriculture to support resilience and production. Extending the greenhouse film rainwater harvesting system to a regional scale and incorporating artificial infiltration measures can establish a coordinated regulation model of “rainwater harvesting-storage-utilization/infiltration”. This approach would not only alleviate the encroachment on ecological water use downstream but also significantly mitigate the pressure on regional groundwater extraction, thereby promoting the long-term stability of the water cycle system.

4.2. Factors Affecting the Water Supply Effectiveness of Rainwater Harvesting Systems for Greenhouses

The water supply effectiveness of RWHUSs depends largely on several parameters, such as rainfall accumulation and timing, rainwater harvesting area, rainwater tank size, crop water consumption intensity, and rainwater harvesting efficiency [19,31]. Generally, water consumption intensity, as a model parameter, can be correspondingly adjusted when irrigation techniques are improved, thereby achieving greater water savings. Examples include utilizing hydroponics, shortening irrigation cycles, and adopting drought-resistant crop varieties. In addition, larger rainwater tanks, lower water demand scenarios, and RWHUS use in humid regions result in higher reliability and water-saving efficiency [32]. In semi-arid regions, the rainwater tank size and rainwater harvesting area are particularly important. In the present study, the crop water satisfaction rate and groundwater replacement rate increased with rainwater tank size, but the increase slowed down as the rainwater tank grew further in size, which is consistent with the results of Imteaz et al. [33], Wu et al. [34], and Jing et al. [35]. However, the increased rainwater tank size directly increases construction costs. Therefore, based on the regional hydrological and geomorphological conditions, harvesting rainwater in non-fertile seasons and non-production areas [36], developing and utilizing underground water tanks of available sizes [37], using adjacent building roofs and roads as supplementary rainwater harvesting surfaces, and organizing the water resources storage–supply pattern over broader temporal and spatial scales are important for ensuring the effectiveness of the water supply in a RWHUS and effectively replacing extracted groundwater, alongside promoting the balance of regional water resource harvesting and supplementation as well as the continuous renewal of water resources.

4.3. Rainwater Harvesting and Storage for Supplementary Irrigation and Marginal Land Use

The regional hydrometeorological environment and geological soil conditions jointly determine the productivity of farmland. RWHUS use provides an effective means of crop water conservation and yield stabilization on marginal land for farming by enabling the management of spatial and temporal mismatches as well as differences in the distribution of supply and demand of soil and water resources [20,38]. Rainwater harvesting and storage can ensure national food security by providing safe and sustained irrigation water to agricultural systems under drought stress during erratic rainy and non-monsoon seasons [39]. Xu et al. [40] showed that the use of rainwater harvesting and storage and supplementary irrigation can successfully realize the production of vegetables, watermelons, and fruit trees in mountainous areas where cash crops could not previously be produced; in such areas, the income from dryland rainwater harvesting and recharge irrigation of vegetables reached 18,000–30,000 RMB·hm−2, increasing the economic return by 28%. This study, conducted on sandy chestnut soil farmland, achieved high yields of small-fruited greenhouse tomatoes at 50,076.6 kg·hm−2 in 2024 and 48,110.2 kg·hm−2 in 2025 by applying 6–8 m3 of groundwater through rainwater harvesting and supplementary irrigation in the respective years [41]. However, this study still has certain limitations, as the water discharge results in substantial resource wastage. Therefore, exploring diverse utilization pathways, such as irrigation for other crops or inter-seasonal storage, represents an effective approach to enhancing the overall water-use efficiency of the system. In addition, the construction and maintenance of rainwater harvesting and storage systems increase production costs, thereby hindering producer acceptance. Nevertheless, this innovation in rainwater harvesting and storage irrigation not only provides key technologies for crop production in drought-prone areas lacking groundwater supplementation and waterlogged regions with poor soil drainage but also provides solutions for stress-resistant production and vegetation establishment on marginal lands, including topographically complex areas, shallow-soil regions, infertile soils, salinized or acidified lands, and urban green spaces. Thus, the government can implement incentive policies to subsidize rainwater harvesting and restrict the excessive extraction of groundwater.

5. Conclusions

Based on the principle of dynamic water balance, this study established an integrated smart rainwater harvesting irrigation model combining “greenhouse film rainwater harvesting with groundwater recharge”. By integrating Python simulation models with a real-time scheduling strategy of “early overflow irrigation and supplemental watering during water scarcity,” it successfully transformed unstable temporal rainfall into a reliable water source for irrigation. Based on a multi-year average rainfall scenario in the cold and arid regions of north China, the simulation analysis showed that under the simple tank capacity of 14.4 m3, groundwater replacement rates of 94.6% for the irrigation of greenhouse tomatoes could be achieved. At the same time, stored and discharged rainwater volumes exceeding the groundwater volume required for supplementary irrigation were generated. Under the actual rainfall scenarios in 2024 and 2025, an irrigation scheme for tomato fields in greenhouses was determined and implemented based on the model of harvesting rainwater from the greenhouse film and providing supplementary irrigation as necessary. This approach achieved 96.1% and 92.3% of the yield of the over-yielding tomato irrigation scheme, and rainwater harvesting replaced 93.8% and 95.0% of groundwater use. This represents a breakthrough from the traditional rainwater harvesting irrigation system’s path dependency on large tank sizes. It demonstrates a significant technological advancement: a minimal tank size of just 14.4 m3 can stably achieve a groundwater replacement rate exceeding 90% for production in a 480 m2 greenhouse. This system provides a practical paradigm for innovation in drought resistance, waterlogging prevention, disaster mitigation, and yield stabilization for greenhouse crops in semi-arid regions. This approach not only alleviated ecological pressures caused by groundwater over-extraction but also, through its synergistic pathway of “water resource substitution–environmental stress reduction–guaranteed tomato yield stability,” offered technical references for groundwater-conserving irrigation practices and the development of sustainable water resource renewal projects. Additionally, the rainwater harvesting storage–groundwater supplemental irrigation tomato water supply capacity model developed in this study could be developed into a mobile-based application. By inputting local crop water requirements and rainfall data, growers could obtain specific rainwater supply results. It could also serve as a simple medium for analyzing all intermediate scenarios, thereby effectively avoiding the need for extensive experimental work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and L.Z.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, J.Z.; data curation, H.L. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., J.Q. and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.Z.; visualization, L.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1901104-5) and the earmarked fund for Hebei Agriculture Research System (HBCT2025140204). We deeply thank Mr. Mickey (and his colleagues), who graduated with a Master’s Degree in Engineering Management from Johns Hopkins University, for his technical support in Python programming and model construction.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aghapour Sabbaghi, M.; Nazari, M.; Araghinejad, S.; Soufizadeh, S. Economic impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in Zayandehroud river basin in Iran. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnadi, E.O.; Newman, A.P.; Coupe, S.J.; Mbanaso, F.U. Stormwater harvesting for irrigation purposes: An investigation of chemical quality of water recycled in pervious pavement system. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 147, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Lu, M.; Chen, L.; Kong, L.; Lei, X.; Wang, H. Analysis of Agricultural Water Use Efficiency Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process and Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation in Xinjiang, China. Water 2020, 12, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, S.; Biazin, B.; Muluneh, A.; Yimer, F.; Haileslassie, A. Rainwater harvesting for supplemental irrigation of onions in the southern dry lands of Ethiopia. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 178, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Chaoying, H. Climate Change and Its Impact on Water Resources in North China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2001, 18, 718–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, L.; Dou, T.; Zhang, L. The Agricultural Cooperative Production Effects on the Water Resource Stock and Agricultural Economic Efficiency in the Agropastoral Ecotone of Norh China. J. Nat. Resour. 2009, 24, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, L.; An, N. The Current Situation, Problems and Suggestions of the Organic Vegetable Industry Development in the Bashang Area of Hebei Province. China Veg. 2022, 5, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Mo, X.; Cai, Y.; Li, X. Analysis on groundwater table drawdown by land use and the quest for sustainable water use in the Hebei Plain in China. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 75, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Yan, J.; Li, H. Impacts of compatibility between rainwater availability and water demand on water saving performance of rainwater harvesting systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. Build well the water conservation functional area and ecological environment support area of the capital. Chin. People’s Political Consult. Conf. 2018, 8, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, I.C.M.; Ghisi, E. Rainwater harvesting through roofs and stormwater harvesting through pervious pavements: A Life Cycle Assessment and decision-making comparison. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Huang, X.; Bei, K.; Zhao, M.; Kong, H.; Zheng, X. A hydroponic green roof system for rainwater collection and greywater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, S.M.; de Farias, M.M.M. Potential for rainwater harvesting in a dry climate: Assessments in a semiarid region in northeast Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L. Stormwater treatment for reuse: Current practice and future development—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Huawei, C.; Shidong, F.; Fulin, L.; Zhen, W.; Xu, D. Analysis of exploitation control in typical groundwater over-exploited area in North China Plain. Hydrolog. Sci. J. 2021, 66, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Zhang, S.; Yue, T. Environmental and economic assessment of rainwater harvesting systems under five climatic conditions of Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Chen, X.; Jia, Z. Effect of Rainfall Collecting with Ridge and Furrow on Soil Moisture and Root Growth of Corn in Semiarid Northwest China. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2010, 196, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, D.; Dang, P.; Wei, L.; Qin, X.; Siddique, K.H.M. Combined ditch buried straw return technology in a ridge–furrow plastic film mulch system: Implications for crop yield and soil organic matter dynamics. Soil Till. Res. 2020, 199, 104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiang, S.; Zhang, G.; Sun, M.; Wen, X.; Liao, Y.; Gao, Z. Effects of ridge–furrow supplementary irrigation on water use efficiency and grain yield of winter wheat in Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dong, Z.; Guo, Q.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Wei, T.; Ding, R.; Cai, T.; Ren, X.; Han, Q.; et al. Ridge–furrow rainwater harvesting combined with supplementary irrigation: Water-saving and yield-maintaining mode for winter wheat in a semiarid region based on 8-year in-situ experiment. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisano, A.; Butler, D.; Ward, S.; Burns, M.J.; Friedler, E.; DeBusk, K.; Fisher-Jeffes, L.N.; Ghisi, E.; Rahman, A.; Furumai, H.; et al. Urban rainwater harvesting systems: Research, implementation and future perspectives. Water Res. 2017, 115, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kang, Y.; Wan, S. Drip fertigation regimes for winter wheat in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 228, 105885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D. Crop evapotranspiration. FAO Irrig. Drain. Pap. 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Sample, D.J.; Liu, J. Optimizing rainwater harvesting systems for the dual purposes of water supply and runoff capture. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 75, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, H. Selection and configuration of rainwater harvesting system substituting groundwater irrigation for greenhouse crops in the Bashang region of Hebei Province. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2025, 36, 218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.; Hubbard, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L. Water stewardship in agricultural supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1170–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershadfath, F.; Shahnazari, A.; Sarjaz, M.R.; Moghadasi, O.A.; Soheilifard, F.; Andaryani, S.; Khosravi, R.; Ebrahimi, R.; Hashemi, F.; Trolle, D.; et al. Water-energy-food-greenhouse gas nexus: An approach to solutions for water scarcity in agriculture of a semi-arid region. Agric. Syst. 2024, 219, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantin, A.B.; Jun, X.; Si, H.J. The impact of climate change on water resource of agricultural landscape and its adaptation strategies: A case study of Chari Basin, Chad. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2017, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, C.; Gonçalves, A.; Castro, P.; Loureiro, D.; Joyce, A. Modelling an agriculture production greenhouse. Renew. Energ. 2001, 22, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacı, S.; Atılgan, A.; Kocięcka, J.; Liberacki, D.; Rolbiecki, R. Use of Rainwater Harvesting from Roofs for Irrigation Purposes in Hydroponic Greenhouse Enterprises. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumit Gómez, Y.; Teixeira, L.G. Residential rainwater harvesting: Effects of incentive policies and water consumption over economic feasibility. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Tam, L.; Zeng, S.X. Cost effectiveness and tradeoff on the use of rainwater tank: An empirical study in Australian residential decision-making. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imteaz, M.A.; Shanableh, A.; Rahman, A.; Ahsan, A. Optimisation of rainwater tank design from large roofs: A case study in Melbourne, Australia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, F.; Feng, P.; Liu, C.; Wang, X. Rainwater harvesting and tomato irrigation schemes optimization for facilities agriculture. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, X.; Zhang, S. Volume calculation and analysis of rainwater collection and utilization reservoir in Beijing. Water Resour. Prot. 2017, 33, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ran, J.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Effect of Water Tank Size and Supply on Greenhouse-Grown Kidney Beans Irrigated by Rainwater in Cold and Arid Regions of North China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Keane, J.; Imteaz, M.A. Rainwater harvesting in Greater Sydney: Water savings, reliability and economic benefits. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 61, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M.; Mohd Hanafiah, M.; Abdul Halim, A.; Badusah, J. Rainwater harvesting as an alternative water resource in Malaysia: Potential, policies and development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, V.; Tulbure, M.G.; Fang, S.; Arumugam, S.; Reba, M.L.; Yaeger, M. Assessing the cumulative impact of on-farm reservoirs on modeled surface hydrology. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2024, 29, 6353–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, H. Vegetable rainwater collection and supplementary irrigation technology. Agric. Technol. Equip. 2011, 05, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Duan, L.; Zhong, H.; Cai, H.; Xu, J.; Li, Z. Effects of irrigation-fertilization-aeration coupling on yield and quality of greenhouse tomatoes. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 299, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.