Abstract

Direct seeding of rice reduces labor intensity and cost, helping alleviate labor shortages in cold-region rice production. To investigate the effects of mechanical precision hill-direct seeding versus mechanical transplanting on yield and nutrient accumulation in cold regions, a set of field split-plot experiments were conducted with cultivation method as the main plot and rice variety as the sub-plot. Our comprehensive measurement results indicate that transplanting significantly increased yield by enhancing tiller number, filled grains per panicle, and grain weight per hill, with significant varietal differences observed. No significant difference in 1000-grain weight was found between the two cultivation methods. Except for Zn content, different cultivation methods have no significant effect on other measured nutrients such as N, P, K, Fe, starch, and fat. Transplanting significantly increased effective tiller number (an increase of 2.6 tillers per hill) and filled grains per panicle (an increase of 12.4 grains), with a significant variety–cultivation method interaction. Qijing 2 (QJ2) and Tiandao 261 (TD261) were more suitable for transplanting to achieve high yield potential, whereas Longgeng 3038 (LG3038) and Tianxiangdao 9 (TXD9) obtained relatively high yields under direct seeding. Therefore, appropriate cultivation methods should be selected based on varietal characteristics: transplanting is recommended for high-yield-potential varieties, while simplified direct seeding is advised for varieties tolerant to direct seeding. Overall, this is a comprehensive consideration and rational strategy based on balancing rice yield, revenue, and benefit, as well as ensuring both food security and farmer income of the entire country and society.

1. Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.), one of the world’s most crucial staple crops, serves as the primary food source for over half of the global population. It is also one of China’s most important food grains. As the leading province in China for high-quality japonica rice production, Heilongjiang achieved a rice output of 28.021 million tons in 2023, ranking first in the country. However, in recent years, challenges such as rural labor shortages, growing water scarcity, and difficulties in obtaining soil for seedling beds have become increasingly prominent. These issues have emerged as bottleneck constraints restricting the development of the rice industry in Heilongjiang Province [1].

With ongoing advancements in agricultural technology, rice cultivation practices have diversified, with direct seeding and transplanting being the primary methods. Direct seeding involves sowing rice seeds directly into the paddy field, offering advantages such as labor savings and reduced production costs compared to the traditional seedling transplanting method [2]. Consequently, direct-seeded rice, recognized as a labor-saving and cost-effective approach, has gained increasing attention in Heilongjiang Province. Numerous studies, both domestically and internationally, have compared water-seeded rice with transplanted rice, examining factors such as yield components, weed control challenges, water use efficiency, and nutrient accumulation [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Some research indicates that under specific conditions, transplanting can lead to higher yields than water drill-seeding [3,4]. Mai et al. [5] found that the primary yield advantage of transplanting stemmed from a higher number of grains per panicle (averaging 25–30 more grains than drill-seeding), although panicle length showed no significant difference between the methods. Conversely, water drill-seeding often encounters more severe weed pressure due to its specific establishment dynamics [6,7], although modified practices, such as the System of Rice Intensification (SRI), can sometimes negate yield differences [8]. Water drill-seeding also demonstrates potential advantages in water savings, though optimal irrigation management remains context-dependent [9,10].

Regarding nutrient composition, similar to findings by Yuan et al. [11] and Amulya et al. [12], studies suggest that micronutrients like zinc can be influenced by cultivation methods. In contrast, research by Wu et al. [13] and Khattab et al. [14], as well as findings in the present study, indicate no significant effect of cultivation method on grain total nitrogen, total phosphorus, starch, or crude fat content. Research on iron accumulation under different cultivation regimes remains limited.

Heilongjiang Province is classified as a cold-region, early-maturing rice zone, with most areas experiencing an annual effective accumulated temperature of below 2700 °C—direct seeding technology, particularly when employing early-maturing cold-tolerant varieties and optimized sowing techniques, offers a means to utilize limited light and heat resources more efficiently, thereby enhancing production stability. Research teams led by Liu Qing and Zhang Xijuan have contributed significantly to direct-seeding rice research in Heilongjiang, focusing on variety screening and cultivation optimization. While Liu Qing’s work emphasized mechanized dry direct seeding and fertilization techniques, the present study proposes an optimized wide-narrow row drill-seeding pattern for water-seeded rice [1]. This pattern aims to improve canopy ventilation and light penetration, potentially unlocking higher yield potential for direct-seeded systems.

Employing a split-plot design, this study systematically compared the effects of water-seeding (wet direct seeding) and transplanting on yield and nutrient accumulation in different rice varieties (QiGeng 2, LongGeng 3038, TianDao 261, and TianXiangDao 9). The objective was to clarify varietal differences in yield and nutrient element accumulation under different cultivation conditions in cold rice regions, thereby providing theoretical and practical support for the rational selection of rice cultivation methods in these areas. The findings hold significant strategic importance for ensuring the stability and sustainable development of rice production in Heilongjiang Province.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The field experiment was conducted in 2024 at the Xiangshun Town research base of the Heilongjiang Engineering Technology Research Center of Rice Quality Improvement and Genetic Breeding, Tonghe County, Harbin City, Heilongjiang Province, China (46° N, 129° E). The site features a cold-region climate characterized by a low accumulated temperature and a short frost-free period. The preceding crop was rice. The experiment was conducted on typical black soil, which is suitable for rice production, with the baseline soil fertility properties presented in Table 1. Soil analysis was conducted by the Open Laboratory of the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Soil pH was measured in a 1 mol/L KCl suspension (soil–solution ratio of 1:2.5).

Table 1.

Soil basal fertility.

2.2. Experimental Design

A split-plot design with five replications was employed. The main plot factor consisted of two cultivation methods: (1) water drill-seeding (direct seeding) and (2) mechanical transplanting. The subplot factor comprised four rice varieties: QJ2, LG3038, TD261, and TXD9 (Table 2). Variety information was obtained from the National Rice Data Center (www.ricedata.com, accessed on 5 June 2025). This resulted in a total of 40 experimental plots, each covering an area of 100 m2. Transplanting Treatment: Seedlings were raised in a nursery on 10 April and transplanted to the field on 15 May at a hill spacing of 30 cm × 16.5 cm. Direct Seeding Treatment: Seeds were sown directly using a drill seeder on 10 May with a row spacing of 23 cm × 16.5 cm. Fertilization: The total fertilizer application rate was identical for both cultivation methods and followed local production practices (Table 3). The applied bio-organic fertilizer contained ≥60% organic matter and a viable bacterial count of ≥2 × 108 CFU/g. The microbial consortium included Bacillus subtilis, Photosynthetic bacteria, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus mucilaginosus, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, and Paenibacillus mucilaginosus. Other Management: All other agronomic practices (irrigation, pest, and disease control) were consistent with local conventional rice field management. Soil management adhered to the conservation tillage practices conventional for the black soil region in this area, which included full residue return of the preceding crop, a tillage system combining autumn deep ploughing with spring rotary tillage, and an alternating “shallow-wet-dry” irrigation pattern maintained throughout the entire growing season. The costs and prices reported in this study were based on a market survey conducted in 2024.

Table 2.

Experimental materials information.

Table 3.

Fertilization rates and application methods.

2.3. Measurements

At physiological maturity, two representative plants were randomly selected from each replication. These plants were carefully harvested to ensure intactness for subsequent morphological and biochemical analyses. Effective Tillers: The number of productive tillers (those bearing panicles) per plant was counted. A tiller was considered effective if it possessed a panicle with at least one filled grain. Filled Grains: Grains that were fully developed and firm. Empty Grains: Grains that were completely unfilled. Shrunken Grains: Grains that were partially filled but visibly shrunken. Thousand-Grain Weight (TGW): One thousand filled grains from each sample were randomly selected and weighed, with the result expressed in grams. The measurements were conducted in triplicate. Grain Weight per Plant (GW): The total weight of all filled grains from a single plant. Straw Weight per Plant (SW): The total weight of the above-ground vegetative biomass (excluding grains) from a single plant after drying.

- Seed Setting Rate (%) = (Number of Filled Grains/Total Number of Grains) × 100

- Empty Grain Rate (%) = (Number of Empty Grains/Total Number of Grains) × 100

- Shrunken Grain Rate (%) = (Number of Shrunken Grains/Total Number of Grains) × 100

- Harvest Index (HI) = Grain Weight per Plant/(Grain Weight per Plant + Straw Weight per Plant)

Nutrient components were analyzed from the milled rice grains. All analyses were performed in triplicate. Total Nitrogen (N): Determined according to the NY/T 2017-2011 standard method. Total Phosphorus (P) and Total Potassium (K): Determined from the same digest following the NY/T 2017-2011 standard. Iron (Fe) and Zinc (Zn) Content: Iron content was determined using GB 5009.90-2016, and zinc content was determined using DB36/T 1243-2020. Starch Content: Determined using the polarimetric method specified in GB/T 20378-2006. Crude Fat Content: Determined by the Soxhlet extraction method using anhydrous ether or petroleum ether as the solvent, following GB 5009.6-2016.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Exploratory data analysis (including tests for normality, homogeneity of variance, and outlier detection) was conducted prior to the formal statistical analysis. Path analysis was employed to evaluate the effects of various factors on rice yield. The model specifically assessed the effects of cultivation practice (CP) on productive tillers (PT), number of filled grains (NFG), seed-setting rate (SSR), and zinc content (Zn), as well as the effects of these variables (PT, NFG, SSR, Zn) on single plant grain weight (SPGW). Data were statistically analyzed, and figures were generated using Microsoft Excel 2019, IBM SPSS Statistics 26, and GraphPad Prism 8. Path analysis was performed using SPSSPRO18.4.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Differences in Thermal Time Utilization Under Two Cultivation Methods

As shown in Table 4, the average annual temperature from April to October between 2020 and 2024 was 3309.3 °C. The temperature at the experimental site in 2024 was 3330.5 °C, indicating its representativeness.

Table 4.

Accumulated growing degree days (GDD) during the growing season from 2020 to 2024. Data source: Tonghe County Meteorological Station.

Table 5 shows that under the transplanting (TP) method, the accumulated effective growing degree days (GDD) during the seedling stage increased by 293.7 °C compared to direct seeding (DS), accounting for 10.8% of the total GDD under DS.

Table 5.

Thermal time allocation under different cultivation methods.

3.2. Effects of Different Cultivation Methods on Yield Components

The cultivation method, variety, and their interaction significantly affected the number of filled grains per panicle (Table 6). Transplanting (TP) produced significantly more filled grains per panicle than direct seeding (DS) (87.4 vs. 75.0). Among the varieties, LG3038 had the lowest value (70.5), significantly lower than the others. A significant variety–cultivation method interaction was observed: TD261 showed the greatest increase under TP (+31.8 grains), followed by TXD9 (+14.9 grains), whereas QJ2 produced slightly (but not significantly) more grains under DS. Consequently, the combination TD261 under TP (Combination 6) yielded the highest number of filled grains (102.6), significantly exceeding all other combinations (Figure 1).

Table 6.

List of statistical analysis tables.

Figure 1.

Variation in filled grains per panicle under different cultivation methods, (A) Bar chart comparing mean values across different cultivation methods; (B) Box plot showing the distribution among different rice varieties; (C) Combined analysis illustrating the interaction effect of different cultivation-variety combinations. Note: Treatment Combination 1 (TC1): QJ2 MHSPF; Treatment Combination 2 (TC2): QJ2 MTRS; Treatment Combination 3 (TC3): LG3038 MHSPF; Treatment Combination 4 (TC4): LG3038 MTRS; Treatment Combination 5 (TC5): TD261 MHSPF; Treatment Combination 6 (TC6): TD261 MTRS; Treatment Combination 7 (TC7): TXD9 MHSPF; Treatment Combination 8 (TC8): TXD9 MTRS. Mechanical transplanting of raised seedlings (MTRS); mechanical hill-drop seeding in puddled fields (MHSPF). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) and asterisks (***, p < 0.001).

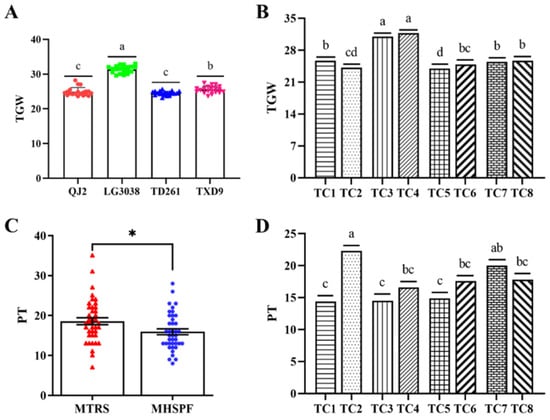

Analysis of variance indicated that transplanting (TP) produced significantly more effective tillers per plant than direct seeding (DS) (18.6 vs. 16.0), with a significant variety–cultivation method interaction. Among the varieties, QJ2 showed the greatest response, with the highest tiller number under TP (22.3) and the lowest under DS (14.4). In contrast, TXD9 produced more tillers under DS (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Comparison of 1000-grain weight and effective tillers under different cultivation methods. Note: 1000-grain weight (TGW), Productive tillers (PT). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) and asterisks (*, p < 0.05). (A) TGW of different varieties; (B) TGW of different combinations; (C) PT under different cultivation methods; (D) PT among different combinations.

For 1000-grain weight, significant differences were observed among varieties, with LG3038 having the highest value (31.4 g). Cultivation method had no significant main effect, but the variety–cultivation method interaction was highly significant (p < 0.01) (Figure 2).

Cultivation method, variety, and their interaction significantly affected the grain filling rate. Overall, the rate was higher under transplanting (TP, 84.9%) than under direct seeding (DS, 82.1%). QJ2 consistently achieved the highest rate among varieties (90.0%), whereas TXD9 showed the lowest (76.6%). A significant interaction was observed: while QJ2, LG3038, and TD261 had higher rates under DS, TXD9 performed significantly better under TP. Consequently, the highest grain filling rate (91.9%) was recorded in QJ2 under DS (Combination 1), and the lowest (66.3%) in TXD9 under DS (Combination 7) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Grain filling rate under different cultivation methods (A) Under different cultivation methods; (B) Of different varieties; (C) Of different combinations. Note: Seed-setting rate (SSR). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) and asterisks (*, p < 0.05).

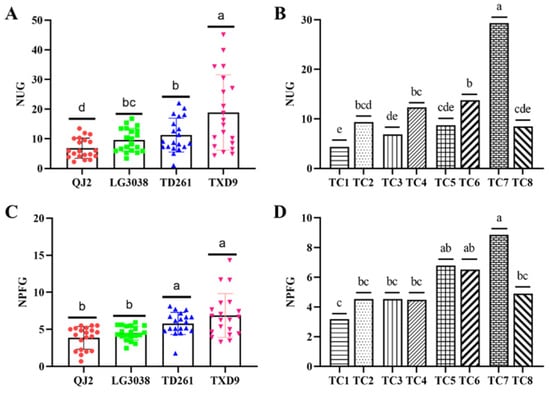

Cultivation method had no significant main effect on the number of empty grains per panicle, whereas variety and the variety–cultivation method interaction were highly significant. The key variety was TXD9, which produced the highest number of empty grains overall (18.9) and exhibited a severe increase under direct seeding (DS, 29.3) compared to transplanting (TP, 8.5). Consequently, the combination TXD9 under DS (Combination 7) resulted in the highest empty grain count, significantly exceeding all others. The trends for empty grain percentage and the number of unfilled grains per panicle were consistent with this pattern, confirming that TXD9 was most susceptible to poor grain filling, particularly under DS (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Empty and unfilled grains per panicle under different cultivation methods. (A) NUG of different varieties; (B) NUG of different combinations; (C) NPFG of different varieties; (D) NPFG of different combinations. Note: Number of unfilled grains (NUG); number of partially filled grains (NPFG). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05).

3.3. Effects of Different Cultivation Methods on Grain Weight per Hill, Straw Weight per Hill, and Harvest Index

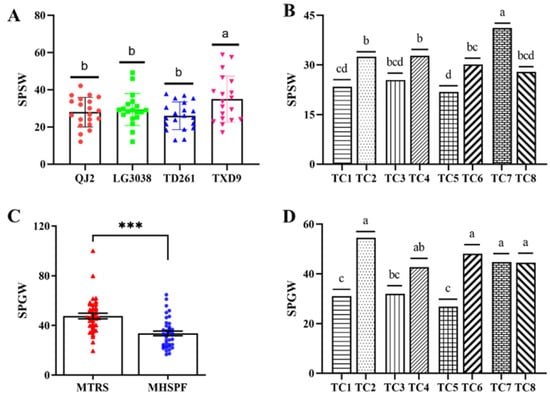

Cultivation method did not significantly affect straw weight per hill. However, variety and the variety–cultivation method interaction had significant effects on this trait. TXD9 exhibited the highest straw weight per hill (34.9 g), significantly greater than the other varieties (p < 0.05), among which there were no significant differences. LG3038, TD261, and QJ2 all produced higher straw weight per hill under transplanting (TP) than under direct seeding (DS). For TD261 and QJ2, the straw weight per hill under TP was significantly higher than under DS. Combination 7 had the highest straw weight per hill (41.2 g), significantly exceeding all other combinations (p < 0.01). Combination 5 had the lowest straw weight per hill and was significantly lower than Combinations 2, 4, 6, and 7 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Straw weight and grain weight per plant under different cultivation methods. (A) SPSW of different varieties; (B) SPSW of different combinations; (C) SPGW under different cultivation methods; (D) SPGW of different combinations. Note: Single plant straw weight (SPSW); single plant grain weight (SPGW). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) and asterisks (***, p < 0.001).

Variety did not significantly affect grain weight per hill. In contrast, cultivation method and the variety–cultivation method interaction significantly influenced grain weight per hill. The average grain weight per hill was significantly higher under TP (47.5 g) than under DS (33.6 g), representing a 41.4% increase. TXD9 had the highest grain weight per hill (44.6 g), while TD261 had the lowest (37.5 g) (Figure 5).

QJ2, LG3038, and TD261 all produced higher grain weight per hill under TP than DS. For QJ2, grain weight was significantly higher under TP (54.5 g) than under DS (31.0 g). Similarly, TD261 showed a significantly higher grain weight under TP (48.2 g) than under DS (26.8 g). LG3038 grain weight was higher under TP (42.7 g) than under DS (32.0 g), but this difference was not significant (Figure 5).

TXD9 showed similar grain weights per hill under TP (44.5 g) and DS (44.7 g), with no significant difference. Combination 2 had the highest grain weight per hill (54.5 g), which did not differ significantly from Combinations 6, 7, and 8. The grain weights of Combinations 2, 6, 7, and 8 were significantly higher than those of Combinations 1, 3, and 5. Combination 4 had a significantly higher grain weight than Combinations 1 and 5 (p < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Cultivation method, variety, and their interaction all significantly affected the harvest index (HI). The HI was higher under TP (0.603) than under DS (0.549). QJ2 had the highest HI (0.594), significantly higher than TXD9 (0.561) and LG3038 (0.564). For all varieties, HI was higher under TP than under DS. This difference was significant for all varieties except LG3038. Combinations 2, 6, and 8 had the highest HI values (0.618, 0.614, and 0.612, respectively), which were significantly greater than those of the other combinations (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Harvest index under different cultivation methods. (A) HI under different cultivation methods; (B) HI of different varieties; (C) HI of different combinations. Note: Harvest index (HI). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) and asterisks (***, p < 0.001).

3.4. Accumulation of Grain Nutrients Under Different Cultivation Methods

Grain nitrogen (N) concentration differed significantly among varieties (p < 0.05). LG3038 had the highest grain N concentration (15.3 g kg−1), followed by TXD9 (14.7 g kg−1). Both were significantly higher than QJ2 (12.8 g kg−1) and TD261 (12.3 g kg−1). No significant difference in grain N concentration was observed between transplanting (TP) and direct seeding (DS) cultivation methods, and the variety–cultivation method interaction was not significant (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Grain nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium concentrations under different cultivation methods. (A) TN content of different varieties; (B) TP content of different varieties; (C) TK content of different varieties; (D) TK content of different combinations. Note: Total nitrogen content (TN), total phosphorus content (TP), total potassium content (TK). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05).

Grain phosphorus (P) concentration varied significantly among varieties (p < 0.05). QJ2 exhibited the highest concentration (3.8 g kg−1), significantly exceeding the other varieties. Cultivation method did not significantly affect grain p concentration. However, a significant variety–cultivation method interaction was observed for grain P concentration (p < 0.05). The pattern for grain potassium (K) concentration was similar to that of P. Significant differences in grain K concentration occurred among all varieties (p < 0.05). TXD9 had the highest K concentration (2.7 g kg−1), while QJ2 had the lowest (2.2 g kg−1) (Figure 7).

Grain iron (Fe) concentration was highest in TD261 (0.58 g/kg−1), but no significant differences were observed among varieties or cultivation methods (p < 0.05). Both variety and cultivation method significantly affected grain zinc (Zn) concentration (p < 0.05). TD261 (0.225 g/kg−1) and TXD9 (0.228 g/kg−1) exhibited significantly higher Zn concentrations than LG3038 (0.148 g kg−1) and QJ2 (0.143 g kg−1). The variety–cultivation method interaction also significantly influenced Zn concentration (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Grain zinc concentration (A–C). Note: Zinc content (Zn). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) and asterisks (*, p < 0.05).

Starch content varied significantly among varieties (p < 0.05). LG3038, TD261, and QJ2 had significantly higher starch content than TXD9. No significant differences were detected between cultivation methods. Crude fat content followed a similar trend to starch: TXD9 and TD261 contained significantly higher crude fat than QJ2 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Starch content under different cultivation methods (D). Note: Starch content (SC). Statistical significance is indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05).

3.5. Path Analysis

As shown in Table 7 and Table 8, transplanting (TP) significantly increased grain weight per plant, primarily through enhanced effective tillering (path coefficient, β = 0.237 *) and increased filled grains per panicle (β = 0.223 *). These pathways accounted for 30.7% of the total effect. Table 9 reveals significant varietal differences in yield formation mechanisms: QJ2 relied predominantly on the tillering pathway for yield increase (β = 0.782 → 0.601). TD261 was governed mainly by the filled grains pathway (β = 0.635 → 0.703). No significant cultivation method effects (p > 0.05) were observed for LG3038 and TXD9, consistent with their field-observed adaptability to direct seeding (DS). Table 10 demonstrates that that grain zinc (Zn) concentration significantly reduced under TP (β = −0.258 **), but indirectly contributed to yield through a positive effect on filled grains per panicle (β = 0.021 *).

Table 7.

Path model results for the full sample (Model 1).

Table 8.

Path model results for the full sample (Model 2).

Table 9.

Variety-specific path effects.

Table 10.

Effect of zinc concentration on filled grains per panicle.

3.6. Economic Analysis Under Different Cultivation Methods

As presented in Table 11, direct seeding (DS) incurred significantly lower investment costs than transplanting (TP), which was primarily reflected in the seedling-raising and transplanting stages. TP required higher expenditures during seedling raising (+970 CNY/ha−1) and transplanting (+300 CNY/ha−1). However, DS incurred greater costs for seed input and field weed control. Market purchase prices varied among varieties due to differences in grain characteristics and quality. Economic returns differed accordingly:

Table 11.

Economic analysis of transplanting vs. direct seeding.

QJ2 and TD261 generated higher economic returns under TP than under DS, attributable to substantial yield gaps between cultivation methods. Conversely, LG3038 and TXD9 showed higher profitability under DS due to minimal yield differences between TP and DS. These results demonstrate that yield performance serves as the primary determinant of economic outcomes across cultivation methods.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion

Rice yield is determined by three primary components: panicles per unit area, grains per panicle, and 1000-grain weight [15]. Fluctuations in any factor can significantly impact the final yield.

4.1.1. Effects on Effective Tillers

Tiller dynamics reflect the regulation of cold-region ecology on cultivation efficacy. Transplanting (TP) significantly increased the number of effective tillers compared to water-sowing (WS). This advantage is attributed to the buffering effect of TP against low-temperature stress through accumulated thermal time during the seedling-raising phase, whereas direct-seeded rice roots are directly exposed to cold soil, potentially delaying tiller initiation. This aligns with previous studies indicating that while WS may reach a tillering peak faster, it often exhibits lower productive tiller efficiency [16,17]. The longer vegetative growth period in TP promotes more effective tillering. Conversely, some studies have reported earlier tillering in WS due to the absence of transplanting root injury [18,19], a discrepancy that may arise from differences in varietal response, planting density, or management practices—all known influencers of tillering [18,19]. Notably, one variety (TXD9) under WS exhibited a relatively excellent performance of tiller number but a relatively poor performance of productive panicle conversion rate (high percentage of unfilled grains), indicating a potential genetic decoupling between tillering potential and panicle formation efficiency under direct-seeding stress. This fully underscores that the rice breeding goal of future simplified cultivation should focus on the balance between tillers’ ability and stress resilience.

4.1.2. Effects on Filled Grains, Grain Filling Rate, and Grain Weight per Hill

Filled grains per panicle and grain filling rate critically determine yield [20]. TP significantly increased the number of filled grains per panicle. This benefit likely stems from multiple factors: TP allows for a longer growth period and higher thermal time accumulation, facilitating better panicle development and a higher capacity for sink formation. In contrast, the shorter growth cycle of WS demands precise nutrient management. The conservative panicle fertilizer strategy employed in WS in this study (to avoid risks associated with late-season cold) may have limited nitrogen availability during the critical grain-filling stages, contributing to fewer filled grains. Furthermore, WS is generally more vulnerable to early-season weed competition and pest pressure, which can further compromise assimilate partitioning and grain filling [21,22]. The higher grain weight per hill under TP is a direct consequence of increased productive tillers and filled grains. Optimized hill spacing in manual TP systems has been shown to improve canopy microclimate (light interception and ventilation), enhancing photosynthesis and biomass accumulation per hill [23,24,25], which supports greater grain yield. Path analysis confirmed that the yield advantage of TP was primarily mediated by enhancing productive tillers and filled grains per panicle.

4.1.3. Effects on 1000-Grain Weight

While genetic improvement of 1000-grain weight remains crucial for yield enhancement [26,27], our study found no significant cultivation-method effect on this trait. Chen similarly reported comparable yields between WS and TP under optimal conditions [8]. LG3038 exhibited the highest 1000-grain weight (31.4 g), consistent with its large-grain genotype, and maintained stability across cultivation methods—indicating strong genetic control. Some studies report a slightly lower 1000-grain weight in WS [28], potentially due to early weed competition or nutrient deficiency impairing grain filling. Conversely, optimized water/weed management, a recipe for increasing rice production in cold regions, can achieve comparable or superior 1000-grain weight in WS [29].

4.1.4. Micronutrient Accumulation Patterns

Cultivation method significantly influenced grain zinc (Zn) concentration, corroborating Yuan, Amulya et al. [11,12]. Deng, JIANG, and Patra attributed this to root–soil interactions: WS roots access soil Zn earlier, whereas TP seedlings experience transplant shock that temporarily impairs nutrient uptake [30,31,32]. Physiological differences between WS and TP systems also modulate Zn assimilation [33]. Grain iron (Fe) concentration showed no cultivation-method effect, reflecting Fe’s stable soil–plant translocation. WS roots inhabit shallower soil layers and may be more sensitive to surface conditions, while TP roots regenerate rapidly after transplanting.

Path analysis identified a compensatory mechanism: Zn indirectly increased yield by +1.4% through promoting filled grains (β = 0.193 *; Table 8). This implies that high-yield and Zn biofortification goals require variety-specific coordination in cold regions. For example, TD261 under TP achieved 102.6 filled grains panicle−1 but only 0.225 g kg−1 Zn concentration.

4.1.5. Macronutrient Accumulation Characteristics

Significant varietal differences in grain nitrogen (N) concentration under TP and WS [13,14] indicate predominant genetic control over N accumulation, consistent with Wu and Khattab. Similarly, Riboni et al. reported genetic variation in phosphorus (P) uptake efficiency [34]. QJ2 showed the highest P concentration (3.8 g kg−1), with significant variety–cultivation method interaction—likely linked to genotypic differences in root P-absorption efficiency [34]. Beyond root architecture, physiological traits also govern P uptake [35,36]. Potassium (K) accumulation mirrored P patterns, confirming varietal specificity in mineral acquisition.

4.1.6. Starch and Fat Accumulation Traits

Starch content varied significantly among varieties [34] but not between cultivation methods, indicating genetic control over starch synthesis. Crude fat content was higher in TXD9 and TD261. Grain fat concentration correlates positively with eating quality [37,38], though it is influenced by both genetics and the environment.

Notably, TXD9 under WS accumulated 8% less starch, despite higher crude fat (positively associated with palatability). Economic analysis showed higher WS profitability for this variety (7426.6 vs. 6463.9 CNY ha−1 under TP), suggesting that simplified cultivation requires balancing yield and quality premiums. Optimizing hill spacing (e.g., wide-narrow row configuration) may mitigate WS-induced starch inhibition—a hypothesis requiring further validation.

5. Conclusions

This study elucidates the effects of transplanting (TP) versus water seeding (WS) on yield components and grain zinc (Zn) concentration of rice in cold-region, highlighting the critical role of varietal specificity and the variety–cultivation method interaction.

Key findings indicate that TP generally enhanced yield by significantly increasing productive tillers, filled grains per panicle, and grain weight per hill compared to WS, while no significant effect was observed on 1000-grain weight. Cultivation method significantly affected grain Zn content but had no consistent impact on other measured nutrients (N, P, K, Fe, starch, and fat). Most importantly, a significant variety–cultivation method interaction was observed for most traits, underscoring the inconsistent response of varieties to cultivation methods, which requires further in-depth research.

Based on this interaction, variety-specific cultivation strategies are proposed: QJ2 and TD261 are better suited to TP to realize their high yield potential, whereas LG3038 and TXD9 exhibit strong adaptability and can achieve competitive yields under a simpler WS system.

This research provides a theoretical basis and practical framework for matching rice varieties with optimal cultivation methods in cold regions. It demonstrates that maximizing productivity and resource efficiency requires a synergistic approach that considers both genotypic traits and agronomic management. Future studies should focus on multi-year and multi-location validations of these interactions, as well as deeper investigations into the trade-offs among yield, grain quality, and economic and environmental benefits under different cultivation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D.; Software, H.D. and Z.C.; Investigation, H.D., J.H., S.Z., and Y.L. (Yingying Liu); Writing—original draft, H.D.; Writing—review and editing, P.S.; Funding acquisition, C.S. and W.-R.S.; Supervision, Y.L. (Yu Luo) and K.L.; Validation, C.S.; Formal analysis, G.Y. and L.C.; Methodology, C.S. and H.D.; Visualization, M.B. and L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2024 Science and Technology Support Project of the Inner Mongolia Innovation Center of Biological Breeding Technology (2024NSZC06); the Major Science and Technology Innovation Research Project for Critical Needs of the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Leap Program in Heilongjiang Province (CX23ZD02); the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences Outstanding Youth Project (CX25JC04); Fundamental Research Funds for the Research Institutes of Heilongjiang Province (CZKYF2023-1-C019); and the National Rice Industry Technology System (CARS-01-57).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Q.; Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Chang, H.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Nie, S. Selection of Rice Varieties Suitable for Dry Direct Seeding in Middle and Late Maturity Areas of Hei long jiang. Hei Long Jiang Agric. Sci. 2025, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, A.; Roychowdhury, S.; Kundu, D.; Singh, R. Evaluation of planting methods in irrigated rice. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2004, 50, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konwar, J.M.; Sarmah, M.; Das, K.; Pegu, L.; Rahman, S.W.; Phukon, S.K. Performance of direct seeded sali rice as influenced by sowing dates, sowing methods and nutrient management practices. Agric. Sci. Dig.-A Res. J. 2018, 38, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jabran, K.; Ullah, E.; Hussain, M.; Farooq, M.; Haider, N.; Chauhan, B.S. Water saving, water productivity and yield outputs of fine-grain rice cultivars under conventional and water-saving rice production systems. Exp. Agric. 2015, 51, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.; Abliz, B.; Xue, X. Increased number of spikelets per panicle is the main factor in higher yield of transplanted vs. Direct-seeded rice. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokilam, M.V.; Rathika, S.; Ramesh, T.; Baskar, M. Weed dynamics and productivity of direct wet seeded rice under different weed management practices. Indian J. Agric. Res. 2023, 57, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.M.; Bhuiyan, S.I.; Moody, K. Water, tillage and weed management options for wet seeded rice in the Philippines. Soil Tillage Res. 1999, 52, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, X.; Wang, D.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X. Influence of the improved system of rice intensification (SRI) on rice yield, yield components and tillering characteristics under different rice establishment methods. Plant Prod. Sci. 2013, 16, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Buttar, G.S.; Brar, A.S.; Deol, J.S. Crop establishment method and irrigation schedule effect on water productivity, quality, economics and energetics of aerobic direct-seeded rice (Oryza sativa L.). Paddy Water Environ. 2017, 15, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoko, K.; Miki, S.; Nobuo, I.T.O.; Kazumasa, N. Comparison of irrigation requirements between transplanting cultivation and direct-seeding cultivation in large-sized paddy fields with groundwater level control systems. J. Teknol. (Sci. Eng.) 2015, 76, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, L. Coated urea enhances iron and zinc concentrations in rice grain under different cultivation methods. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amulya, D.; Chaitanya, K.A.; Kumar, S.R.; Rajanikanth, E. Effect of Different Rice Establishment Methods on Soil Nutrient Status and Carbon Stock in Paddy Growing Soils of Jagtial, Telangana, India. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1372–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Que, R.; Qi, W.; Duan, G.; Wu, J.; Zeng, Y.; Pan, X.; Xie, X. Varietal Variances of Grain Nitrogen Content and Its Relations to Nitrogen Accumulation and Yield of High-Quality Rice under Different Nitrogen Rates. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, A.E. Performance Evaluation of Some Rice Varieties under the System of Planting in Egypt. Asian J. Res. Crop Sci. 2019, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhang, L.; He, N.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, M.; Wang, C.; Zheng, W.; Yin, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of Mechanical Direct Dry Seeding on Rice Growth, Photosynthetic Characteristics and Yield. Crops 2021, 5, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Yang, X.; Wu, L.; Ma, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Evaluation of Nitrogen Fertilizer and Cultivation Methods for Agronomic Performance of Rice. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1907–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dhaliwal, L.K.; Sandhu, S.K.; Singh, S. Effect of plant spacing and transplanting time on phenology, tiller production and yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 7, 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.G.; Huang, S.Q.; Jiang, Y.; Cai, M.L.; Cao, C.G.; Tang, X.R.; Li, G.X. Effects of Rice Seedling Age and Transplanting Density on the Biological Characteristics of Rice. Acta Agric. Boreali-Sin. 2011, 26, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal, Y.S.; Nagi, H.P.S.; Sidhu, G.S.; Sekhon, K.S. Physicochemical, milling and cooking quality of rice as affected by sowing and transplanting dates. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1986, 37, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhang, N.; Shu, X.L.; Wu, D.X.; Han, J.Y. Research Progress on Influence Factors of Rice Grain Filling and its Related Genes and Proteins. China Rice 2018, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Luo, Y.; Guo, C.; Li, B.; Li, F.; Xing, M.; Yang, Z.; Ma, J. Effects of Water and Nitrogen on Grain Filling Characteristics, Canopy Microclimate with Chalkiness of Directly Seeded Rice. Agriculture 2022, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, V.N.; Thach, N.T.; Hoang, N.N.; Binh, N.C.Q.; Tâm, D.M.; Hau, T.T.; Anh, D.T.T.; Khuong, T.Q.; Chi, V.T.B.; Lien, T.T.K.; et al. Mechanized wet direct seeding for increased rice production efficiency and reduced carbon footprint. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2226–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.A.; Singh, G. Effect of seedling density and planting geometry on hybrid rice. Oryza 2005, 42, 327–328. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Tong, P.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, Y. Effects of Different Seedling Ages and Planting Densities on Physiological Characteristics and Grain Yield of Hybrid Rice Ⅱ You 498 under Triangle Planted System of Rice Intensification During Filling Stage. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2011, 25, 508–514. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Lü, T.; Jiang, M.; Yan, F.; Ma, J. Effects of Mechanical-transplanted Modes and Density on Root Growth and Characteristics of Nitrogen Utilization in Hybrid Rice at Different Seedling-ages. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2017, 31, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.W.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Huang, D.R.; Fan, Y.Y.; Zhuang, J.Y. Mapping of qTGW1.1, a Quantitative Trait Locus for 1000-Grain Weight in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice Sci. 2015, 22, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravois, K.A. Genetic effects determining rice grain weight and grain density. Euphytica 1992, 64, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, M. Grain-filling pattern of super hybrid rice Liangyoupeijiu under direct seeding and transplanting condition. Int. J. Agric. Res. Innov. Technol. 2014, 4, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, Q.; Li, L.; Xu, H.; Zheng, H.; Wang, J.; Hua, Y.; Ren, L.; Tang, J. Ratoon rice with direct seeding improves soil carbon sequestration in rice fields and increases grain quality. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, Q. Variations in iron plaque, root morphology and metal bioavailability response to seedling establishment methods and their impacts on Cd and Pb accumulation and translocation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yang, Y.; Fu, M.; Chi, Z.Z.; Zheng, J.G. Effects of direct seeding and sowing methods on growth and yield of direct-seeding rice. China Rice 2018, 24, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, B.; Jena, S.; Phonglosa, A.; Panda, N.; Sahu, S.G.; Mangaraj, S.; Mishra, P. Effect of Transplanting Dates and Nutrient Management Options on Nutrient Partitioning and Accumulation in Rice. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2024, 55, 3247–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cai, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, G.P. Genotypic Differences in Growth and Physiological Responses to Transplanting and Direct Seeding Cultivation in Rice. Rice Sci. 2009, 16, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riboni, M.; Galbiati, M.; Tonelli, C.; Conti, L. Gigantea enables drought escape response via abscisic acid-dependent activation of the florigens and suppressor of overexpression of constans. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1706–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejchasarn, P.; Lynch, J.P.; Brown, K.M. Genetic Variability in Phosphorus Responses of Rice Root Phenotypes. Rice 2016, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Dong, L.; Lü, W.; Meng, Q.; Liu, P. Transcriptome analysis of maize seedling roots in response to nitrogen-, phosphorus-, and potassium deficiency. Plant Soil Int. J. Plant-Soil Relatsh. 2020, 447, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, R.M.; Lee, C.S.; Kang, Y.M. The lipid composition of rice cultivars with different eating qualities. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2012, 55, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, L.; Geng, X.; Xia, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Xu, Q. Deciphering the Environmental Impacts on Rice Quality for Different Rice Cultivated Areas. Rice 2018, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.