Abstract

The Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. industry suffers significant losses due to fungal diseases. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of sodium benzoate (SB) and potassium sorbate (PS) on the incidence of fungal decay and fruit quality when used as preharvest treatments on Fino lemon trees over two consecutive seasons (2021–2023). Lower concentrations of SB and PS (0.1% and 0.5%) applied in one or two treatments successfully controlled fungal decay. On average, SB achieved a greater reduction in decay, ranging from 45% to 60%, compared to PS’s reduction of 25% to 50%. This approach minimised the negative impact on lemon fruit quality, in contrast to the highest doses (more than 1%) and the greatest number of applications (more than three times), which increased lemon susceptibility to decay. Furthermore, lemons treated with 0.5% SB twice enhanced antioxidant systems, showing a 35% increase in total phenolic content in the flavedo at harvest compared to the control. Consequently, the application of 0.5% SB twice at preharvest emerges as a promising and potential alternative to conventional fungicides for effective fungal decay control and maintenance of acceptable lemon quality traits during cold storage.

1. Introduction

Lemon (Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f.) is the third most widely produced citrus fruit after oranges and mandarins, with Spain being one of the main producers. Spain is responsible for 61% of total European production, with nearly 885 thousand tonnes produced in 2019 [1]. However, postharvest losses, ranging from 30 to 50% of the total production, are a significant issue due to physiological disorders and postharvest diseases, leading to waste and economic losses [2]. The main postharvest diseases affecting lemons are blue mould, green mould and sour rot, which are caused by Penicillium digitatum, Penicillium italicum and Geotrichum citri-aurantii, respectively. These fungi are considered wound pathogens, requiring a lesion in the skin to be able to initiate the infection [3]. Control of these diseases has traditionally relied on conventional fungicides, such as imazalil and thiabendazole [4]. However, growing concerns regarding environmental risks and the impact on human health emphasise the need for alternative control methods [5]. One emerging alternative is the use of compounds generally recognised as safe (GRAS), since they present low toxicity and quick degradation, thus minimising their impact on human health and the environment [2,6]. Nevertheless, it is crucial to optimise the application of these salts to minimise their negative impact on fruit quality. The key is to find the right balance between a salt concentration that controls fungal growth and one that does not harm the surface of the fruit or internal structure.

Potassium sorbate (PS), the salt of sorbic acid, has been widely used as a fungistatic agent in food products, including fruit and vegetables. PS is commonly used as a postharvest treatment, either alone or in combination with other strategies, such as heat treatments, synthetic fungicides and high carbon dioxide levels. It is also used as an ingredient in edible coatings. A large-scale experiment involving inoculated oranges and lemons with P. digitatum and P. italicum reported that PS was one of the most effective compounds tested, achieving an average fungal growth inhibition of 75% [7]. Previous studies on Fino lemons have also demonstrated that applying PS at 0.5%, 2% and 3% by dipping after harvest can reduce green mould incidence by 50% [8]. Sodium benzoate (SB) has shown high antimicrobial efficacy against bacteria and fungi at concentrations of up to 0.1% [9]. A previous in vitro study tested SB against P. digitatium achieving the highest inhibition at the highest concentration (75 µg/mL) [10]. In vivo experiments on stone fruits revealed that the most effective concentration for controlling Monilinia fructicola, Alternaria alternata and Botrytis cinerea was 200 mM of SB [11]. In citrus fruits, applying SB at 2% significantly reduced the incidence of green and blue mould by 70% after two weeks at 12 °C [12]. The antifungal mechanisms of action of PS and SB are fundamentally similar. They rely on pH alteration and the presence of Na+, K+ or NH4+ cations to promote the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the accumulation of sorbate and benzoate anions, which interfere with the activity of the key enzymes related to the electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation [13].

Furthermore, PS and SB have the potential to maintain high fruit quality parameters. PS coatings have been found to positively affect the quality of jujube [14] and pomegranate [15] fruits. They extend their shelf life by controlling the ripening process and preserving antioxidants such as phenolic compounds, flavonoids and ascorbic acid, while also improving physicochemical properties such as weight loss, firmness and the ratios of total soluble solids and titratable acidity. Cherry tomatoes [16] and pears [17] treated with SB exhibited improved firmness due to reduced enzymatic activity of cellulase, pectin methyl esterase and polyphenol oxidase. Additionally, higher sensory quality and total phenolic content were observed.

Most of these studies have been conducted in postharvest, and there is a lack of research investigating the preharvest use of SB and PS. Only a few studies have focused on the application of GRAS salts in preharvest for lemons [18,19], oranges [20] and mandarins [21]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to elucidate the effect of preharvest treatments with PS and SB on the incidence of fungal decay in lemons, and to optimise the number of applications required and their concentration, in order to minimize the negative effects on lemon fruit quality and functional properties at harvest and after 35 days of storage at 8 °C. These findings could be a significant contribution to the lemon industry, providing an alternative to conventional fungicides and enhancing food safety while minimising environmental residue and promoting sustainable practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

The experiments were conducted in a commercial lemon orchard in La Aparecida (Alicante, Spain) (38°04′52″ N 1°00′32″ O) over two consecutive growing seasons. The average temperature in the 2021–2022 season was 19.4 °C, with 280 mm of rainfall, and the average temperature in the 2022–2023 season was 18.9 °C, with 260 mm of rainfall. A single 13-year-old cultivar of Fino lemon trees grafted onto Citrus macrophylla was used. The trees were planted at 7 m × 5 m and cultivated using standard agronomical practices. Three blocks of three lemon trees were randomly allocated to each treatment, concentration and number of applications.

During the first growing season, lemon trees were treated by foliar and fruit spray containing sodium benzoate (SB) and potassium sorbate (PS) (Suministros Rivers, Alicante) at three different concentrations (0.5, 1 and 3% w/v). These salts and concentrations were selected according to the results previously published [4]. Salts were diluted in tap water containing 0.1% Tween 20 as a surfactant. Control trees were treated with tap water containing 0.1% Tween 20. Five litres of each treatment were applied to the entire canopy of the tree, with special attention given to the fruits. Salt treatments were applied four times, once a month, starting after the fruit had set, with the last treatment taking place four days before harvest. Based on the results obtained, the concentrations of SB applied in the second growing season were 0.1% and 0.5%. The decision to include a lower concentration of SB (0.1%) aimed to evaluate whether reducing the dose would still maintain fruit quality while reducing fungal decay. These treatments were prepared and applied using the same methodology as in the first season. Additionally, the number of foliar applications was controlled in this experiment to optimise the exposure of the crop to the salt, as shown in Table 1. In this second experiment, only the quality and functional parameters of the lemons treated once and twice were analysed due to the high incidence of fungal decay observed in the lots with three and four applications.

Table 1.

Number and dates of foliar application of SB 0.5 and 0.1% treatments in the 2022–2023 harvest season.

Lemons from the two seasons were harvested on 2 February 2022 and 8 January 2023, respectively. Lemons at the yellow commercial ripening stage and the optimal diameter (55 mm) were harvested and transferred to the laboratory within 2 h. Lots of 15 uniform lemons (three replicates of five lemons each), free from any physical damage and consistent in colour and size, were selected and evaluated at harvest and after 35 days at 8 °C and 85% relative humidity (RH).

A parallel experiment was conducted to evaluate the incidence of natural decay in lemons. Ten boxes, each containing 100 lemons, were stored under commercial conditions at 8 °C and 85% RH. Furthermore, a ventilation system was used to dissipate undesirable gases and prevent off-flavours, while maintaining air quality. Decay incidence was evaluated weekly for 35 days, with any lemons displaying disease symptoms such as water-soaked spots, mycelium or spores were identified and discarded. Fungal decay was expressed as accumulated decay, where the number of lemons that had decayed on each previous sampling day was summed up [22].

2.2. Physiological and Quality Parameters

The individual weight of each fruit was recorded on day 0 and after 35 days of cold storage using a Radwag WLC 2/A2 precision balance (Radwag Wagi Elektroniczne, Radom, Poland), and the weight loss (WL) was expressed as percentage (%). Individual fruit firmness was determined using a TX-xT2i texture analyser (Stable Microsystems, Godalming, UK) coupled to a steel plate causing a deformation of 5% of the diameter of the fruit and it was expressed as N mm−1. Colour was assessed on each fruit using a Minolta colourimeter (CRC200; Minolta, Osaka, Japan) and was reported as hue angle (h°). The respiration rate (RR) was measured using three replicates of five fruits each. Samples were held at room temperature in 3.7 L containers for 60 min; 1 mL of headspace was then analysed via gas chromatography (Shimadzu 14B-GC, Kyoto, Japan) with a thermal conductivity detector. The RR was expressed in mg of CO2 kg−1 h−1 [23]. Total soluble solids (TSS) and titratable acidity (TA) were measured in duplicate using lemon juice pooled from five fruits for each replicate per treatment. TSS was determined using a digital refractometer (Hanna Instruments, Rhode Island, USA) and expressed as g of sucrose equivalent per L−1. TA was measured by titrating 0.5 mL of juice (diluted in 25 mL distilled water) with 0.1 mM NaOH to a pH of 8.1 using an automatic titrator (OMNIS, Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland). TA results were expressed as g of citric acid equivalent per L−1.

2.3. Total Phenolic Content

Total phenolic content (TPC) was determined by homogenising 2 g of frozen flavedo in 15 mL of water–methanol (2:8, v/v) solution containing 2.0 mM NaF. The mixture was centrifuged at 10,000× g and 4 °C for 20 min. TPC was then measured in duplicate for each of the three replicates using the Folin–Ciocalteau reagent [24], with the results expressed as g of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) to kg of fresh weight (FW).

2.4. Total Antioxidant Activity

Total antioxidant activity (TAA) was measured by homogenising 2 g of frozen flavedo in 10 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.8 and 5 mL of ethyl acetate (Sigma Aldrich, Madrid, Spain). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C to separate the phases. Lipophilic (L-TAA) and hydrophilic (H-TAA) antioxidant activities were quantified in the upper and lower fractions of the extract, respectively, using the ABTS-peroxidase system as described [25]. TAA was calculated as the sum of both fractions and expressed as g of Trolox equivalent to kg of fresh weight (FW).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of three replicates. Data (decay incidence, WL, firmness, RR, colour, TSS, TA, TPC and TAA) were subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Tukey’s multiple-range test was used to determine significant differences between treatments (p-value < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software v. 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). PCA models were constructed with normalised data using Unscrambler 11 software (CAMO AS, Oslo, Norway).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Preharvest Treatments with Sodium Benzoate and Potassium Silicate (2021–2022 Experiment)

3.1.1. Fungal Decay Incidence

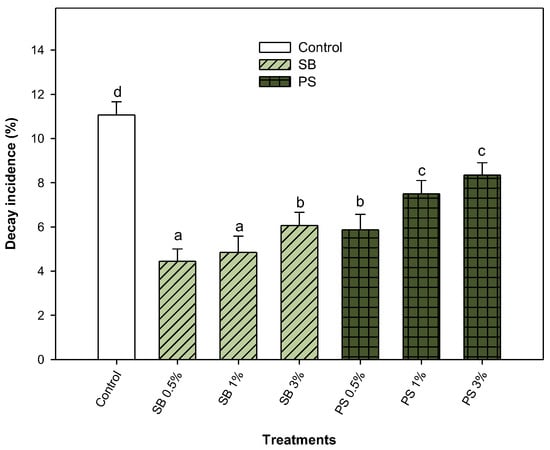

The effect of SB and PS at three different concentrations (0.5%, 1% and 3%) on the decay incidence after 35 days of storage at 8 °C was evaluated. The results showed that all preharvest treatments significantly (p < 0.05) reduced the incidence of decay after 35 days of storage (Figure 1). SB was more effective than PS in reducing fungal decay. A decay incidence of 11.06 ± 0.60% was observed in non-treated lemons. The best results in SB-treated lemons were observed at 0.5% and 1%, with a decay incidence of 4.45 ± 0.55% and 4.85 ± 0.73%, respectively. For PS-treated lemons, 0.1% achieved the highest decay reduction, resulting in a decay incidence of 5.87 ± 0.70% (Figure 1). Therefore, the highest reduction in fungal decay was observed applying medium or low salt concentrations; high concentrations were associated with negative results.

Figure 1.

Incidence of fungal decay (%) in Fino lemons from the 2021–2022 growing season, treated in preharvest with sodium benzoate (SB) and potassium sorbate (PS) at 0.5, 1 and 3% after 35 days of storage at 8 °C. Values are means ± standard error. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by different letters according to the Tukey test.

3.1.2. Physicochemical Parameters of Lemon Fruit Quality

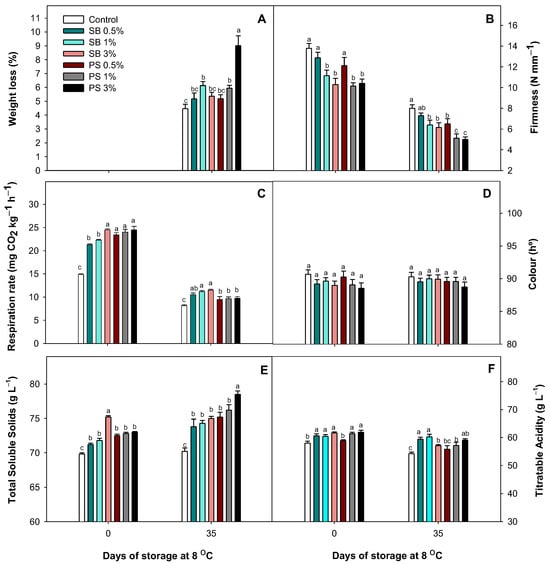

The application of SB and PS increased the WL of Fino lemons after 35 days of storage compared to the controls, although the highest values were detected in those treated with 1% SB and 3% PS. Thus, lemons treated in preharvest with 3% PS were negatively affected, resulting in a WL 2.25 times higher than non-treated lemons. Conversely, the best results for treated lemons were observed at concentrations of 0.5% and 1% for both GRAS salts (Figure 2A). The application of both organic salts decreased the fruit firmness at harvest and after 35 days of storage in most treatments. Only the application of 0.5% SB and 0.5% PS showed no significant differences (p > 0.05) compared to non-treated fruits at harvest. After 35 days of cold storage, PS-treated fruits at 1% and 3% exhibited the lowest firmness, with reductions of 36% and 37.5%, respectively, compared to the controls (Figure 2B). However, SB had a smaller effect on firmness. The RR decreased after storage, and it was significantly (p < 0.05) affected by the application of both organic salts, being higher than the control fruits at harvest and after 35 days of cold storage (Figure 2C). No significant (p > 0.05) differences in colour (hue angle) were observed between treatments at harvest and after 35 days of cold storage (Figure 2D). The application of both salts significantly (p < 0.05) increased the TSS content and the TA of lemons at harvest and after 35 days of storage. In this sense, TSS levels increased during storage, with the highest results found in those treated with 3% PS. Regarding TA, the highest levels after storage were observed in SB-treated lemons at 0.5% and 1% (Figure 2E,F).

Figure 2.

Effect of sodium benzoate (SB) and potassium sorbate (PS) at three concentrations (0.1, 1, 3%) on the weight loss (A), firmness (B), respiration rate (C), colour (D), total soluble solids (E) and titratable acidity (F) of Fino lemons at harvest and after 35 days of storage at 8 °C during the season 2021–2022. Values are means ± standard error. Significant (p < 0.05) differences between treatments are indicated by different letters according to the Tukey test.

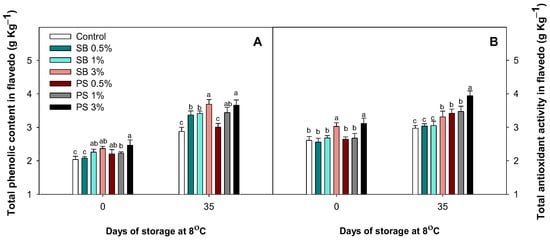

3.1.3. Phenolic Content and Total Antioxidant Activity

Total phenolic content (TPC) at harvest generally increased with the application of both salts, although it did not increase in fruits treated with 0.5% SB (Figure 3). After 35 days of cold storage, TPC increased in all treatments, although lower accumulation was observed in fruits treated with the lowest salt concentration (Figure 3A). In addition, at harvest, the impact of both high salt concentrations (3%) was observed, enhancing the TAA in the flavedo of lemon fruit. This effect was maintained during cold storage, with the highest TAA levels observed in PS-lemons independently of the dose, and in SB-lemons treated at 3%. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the treatments with the least impact on the TAA levels in lemon fruit flavedo were 0.5% and 1% SB, which maintained similar levels to those of the controls (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of sodium benzoate (SB) and potassium sorbate (PS) at three concentrations (0.1, 1, 3%) on the total phenolic content (A) and total antioxidant activity (B) of Fino lemon fruit flavedo at harvest and after 35 days of storage at 8 °C during the season 2021–2022. Values are means ± standard error. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by different letters according to the Tukey test.

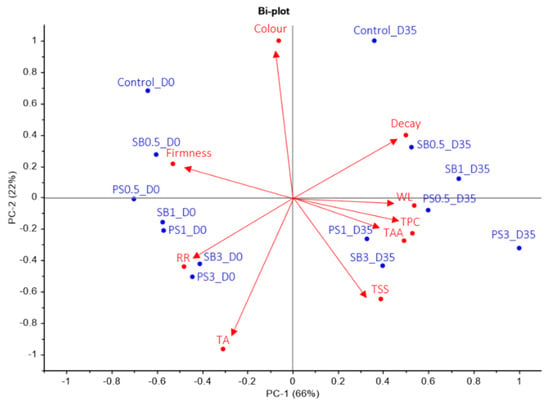

3.1.4. Principal Component Analysis

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on all the results, revealing that PC-1 and PC-2 explained 66% and 22% of the total variance in the X and Y variables, respectively (Figure 4). The cumulative variance contribution of PC-1 and PC-2 was 88%. PC-1 was clearly associated with WL (0.40), firmness (−0.39), RR (−0.35), decay (0.37), TPC (0.36) and TAA (0.36), while PC-2 was related to colour (0.58), TSS (−0.38) and TA (−0.58). Parameters on the negative side of PC-1 were colour, firmness, RR and TA, while on the positive side were found decay, TSS, TAA, TPC and WL. The most important parameters on the negative side of PC-2 were RR, TA, TSS, TAA, TPC and WL, and on the positive side were found firmness, colour and decay. The results showed that PC-1 allowed differentiation of postharvest storage into two groups: lemons analysed on day 0 were located on the negative side, while those analysed after 35 days of cold storage were located on the positive side. For PC-2, the results could be divided into three groups: the first group consisted of both controls; the second group included lemons treated with 0.5% and 1% SB and PS at harvest and after 35 days of cold storage; and the third group was mainly represented by lemons that were treated with 3% SB and PS.

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot of the physicochemical traits analysed, showing the relationship among lemons treated with sodium benzoate (SB) and potassium sorbate (PS) at 0.5, 1 and 3% and controls at harvest (D0) and after 35 days of storage at 8 °C (D35) during the 2021–2022 growing season. The treatments at harvest and after cold storage are shown in blue, while the vectors of the quality traits are shown in red.

3.2. Effect of Preharvest Treatments with Sodium Benzoate (2022–2023 Experiment)

Based on the previous results in controlling fungal decay incidence while maintaining optimal fruit quality parameters, it was decided to continue optimising the application of SB during the second harvest season (2022–2023). Furthermore, evidence of the negative effects of high salt doses on fruit quality was critical in deciding to include the 0.5% treatment and a treatment that reduced the SB concentration to 0.1%. Therefore, SB was applied at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.5% once to four times (1T to 4T) in order to reduce salt exposure, as shown in Table 1.

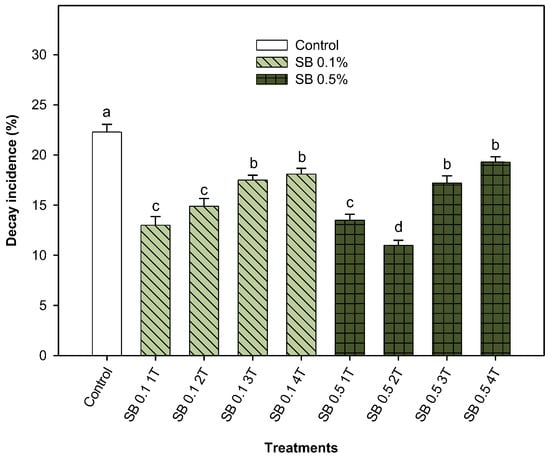

3.2.1. Fungal Decay Incidence

The incidence of decay was evaluated after 35 days of storage at 8 °C (Figure 5). All treatments resulted in a significantly (p < 0.05) lower fungal decay, regardless of the concentration and number of applications. However, it was observed that a lower number of applications, once (1T) or twice (2T), resulted in a greater reduction in decay incidence than in non-treated lemons. A single application of SB at 0.1% and 0.5% resulted in reductions of decay incidence of 41.70% and 39.46%, respectively, while two applications of SB at 0.1% and 0.5% resulted in reductions of 33.18% and 50.67%, respectively.

Figure 5.

The incidence of fungal decay (%) in Fino lemons from the 2022–2023 growing season was investigated. The lemons were treated in preharvest with sodium benzoate (SB) at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.5%, applied one time (1T), two times (2T), three times (3T) or four times (4T), and stored for 35 days at 8 °C. Values are means ± standard error. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are indicated by different letters according to the Tukey test.

Based on the incidence of decay results observed in Figure 5, quality parameters were determined for lots receiving one or two applications of SB before harvest. Then, the quality parameters of the lemons were evaluated at harvest and after 35 days of storage at 8 °C.

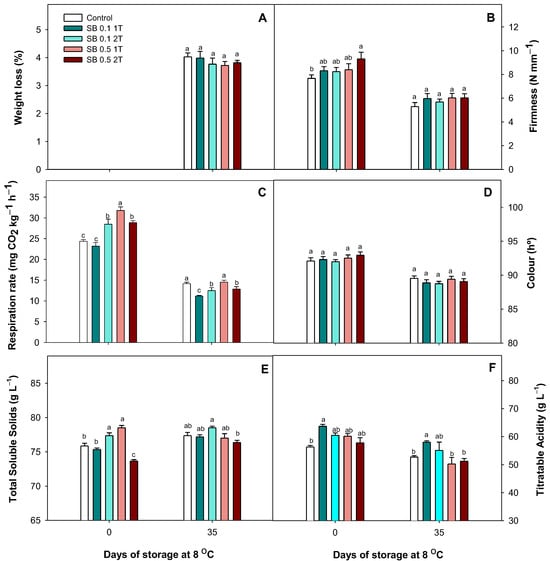

3.2.2. Physicochemical Parameters of Lemon Fruit Quality

Results for WL showed non-significant differences (p > 0.05) between treatments as shown in Figure 6A. The results for firmness at harvest showed the highest values for lemons treated with 0.5% SB 2T. Non-treated fruits presented a firmness of 7.67 ± 0.29 N mm−1 compared to 9.31 ± 0.57 N mm−1 for lemons treated with 0.5% SB 2T. This quality parameter decreased in all samples during storage, and no significant (p > 0.05) differences were observed after 35 days of cold storage (Figure 6B). The respiration rate at harvest was higher in lemons treated with 0.1% SB twice and 0.5% SB once or twice, with the fruits treated once with 0.1% SB being the only ones at the same level as the controls. After 35 days of cold storage, the RR decreased in all samples. However, the lowest values were found in fruits treated with 0.1% SB once or twice, with decreases of ca. 21% and 12%, respectively (Figure 6C). Colour was evaluated, and non-significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed at harvest and after 35 days among treatments (Figure 6D). Total soluble solids at harvest were higher in lemons treated with 0.1% SB 2T and 0.5% SB 1T, increasing ca. 6% and 9%, respectively. After 35 days of cold storage, the TSS values were similar for all samples except for those treated with 0.1% and 0.5% SB 2T (Figure 6E). Titratable acidity at harvest was higher in lemons treated with 0.1% SB 1T, while no significant (p > 0.05) differences were found in the rest of the treated lemons compared to the controls. Furthermore, these differences were maintained after 35 days of cold storage (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

The effect of preharvest treatment involving the application of sodium benzoate (SB) at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.5% applied once (1T) or twice (2T) on the weight loss (A), firmness (B), respiration rate (C), colour (D), total soluble solids (E) and titratable acidity (F) of Fino lemons at harvest and after 35 days of storage at 8 °C during the 2022–2023 growing season. Values are means ± standard error. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are presented with different letters according to the Tukey test.

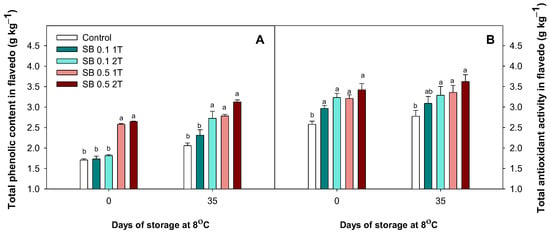

3.2.3. Phenolic Content and Total Antioxidant Activity

A 30% and 35% increase in TPC was observed at harvest in lemons treated with 0.5% SB 1T and 2T, respectively. After 35 days of cold storage, the lowest accumulation of phenolic compounds was observed in the controls and in lemons treated with 0.1% SB 1T, and the highest values were found in lemons treated with 0.1% SB 2T, 0.5% SB 1T and 2T (Figure 7A). Regarding TAA at harvest, all treatments showed higher values than the non-treated lemons, independently of the concentration or the number of applications. Moreover, the differences observed at the beginning of the experiment were maintained after 35 days of cold storage (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

The effect of preharvest treatment involving the application of sodium benzoate (SB) at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.5% applied once (1T) or twice (2T) on the total phenolic content (A) and total antioxidant activity (B) of Fino lemons at harvest and after 35 days of storage at 8 °C during the 2022–2023 growing season. Values are means ± standard error. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments are presented with different letters according to the Tukey test.

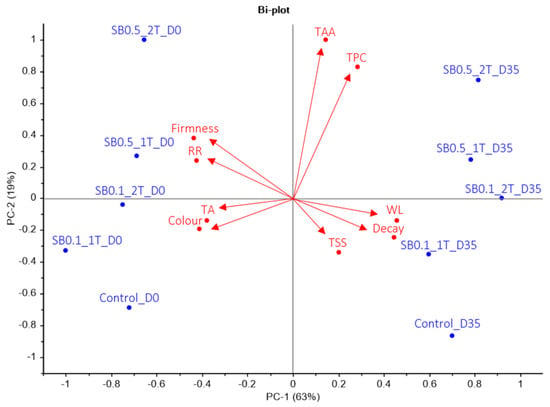

3.2.4. Principal Component Analysis

PCA was applied to all the results, revealing that PC-1 and PC-2 accounted for 63% and 19% of the total variance in the X and Y variables, respectively (Figure 8). The cumulative variance contribution of PC-1 and PC-2 was 82%. PC-1 was clearly associated with WL (0.41), firmness (−0.39), RR (−0.38), colour (−0.37), TA (−0.34) and decay (0.40), whereasPC-2 was associated with TSS (−0.33), TPC (0.57) and TAA (0.68). Parameters on the negative side of PC-1 were firmness, RR, TA and colour, while parameters on the positive side were found TAA, TPC, WL, decay and TSS. The most important parameters on the negative side of PC-2 were TA, colour, TSS, decay and WL, and on the positive side were found firmness, RR, TAA and TPC. The results showed that PC-1 enabled differentiation of postharvest storage into two groups: lemons analysed on day 0 were located on the negative side, while lemons analysed after 35 days of cold storage were located on the positive side. For PC-2, the results could be divided into four groups. The first group consisted of lemons treated with 0.5% SB 2T at harvest and after 35 days of storage. The second group included lemons treated with 0.1% SB 2T and 0.5% SB 1T at harvest and after 35 days of cold storage. The third group comprised lemons treated with 0.1% SB 2T, and the fourth included control lemons.

Figure 8.

The principal component analysis (PCA) biplot shows the relationship among lemons treated with sodium benzoate (SB) at 0.5% and 1%, once or twice, and the control group, at harvest (D0) and after 35 days of storage (D35) at 8 °C during the 2022–2023 growing season. The treatments at harvest and after cold storage are shown in blue, while the vectors of the quality traits are shown in red.

4. Discussion

Fungal diseases that occur during postharvest storage cause significant economic losses for the citrus industry. A large number of studies have focused on the effect of organic salts on fungi, providing valuable insights into their antifungal properties. However, the impact of organic salts applied in preharvest on natural lemon infections during storage remains an important area for the industry to explore. The development of phytopathogens depends on their intricate interactions with hosts and environments. It is essential to control fungal activity directly in the field. This is the critical first step, as the infection is initially triggered by two conditions: wet weather activates the fungal pathogenic process, while high winds cause wounds on the lemon rind. These initial events determine the level of infection in the later stages of lemon fruit production. The inhibitory effect of salts on fungal infection in lemons depends on the presence of residues that either physically block the fungus or interact with components of the lemon peel. The efficacy of organic acids is also highly pH-dependent, as their antimicrobial activity is primarily driven by their undissociated form [7]. The low-toxicity salts SB and PS are known to be more fungistatic than fungicidal. They effectively control decay when an optimal combination of factors is present, such as the pathogen, the fruit cultivar and the environmental conditions [26]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the preharvest application of SB and PS for controlling fungal decay in lemons.

In the present study, considering both seasons, the greatest reduction in fungal decay was achieved using SB at 0.5% (first season) and SB at 0.5% applied twice (second season) (Figure 1 and Figure 5). Similar results were reported by the authors of [3,27], who observed an effective inhibition of Penicillium, Alternaria and Cladosporium diseases in citrus and jujube treated with SB solutions. The most significant fungi causing lemon rot in postharvest are P. digitatum and P. italicum. These fungi are wound pathogens, and once a wound occurs the presence of the salt could create an unfavourable environment for the development of the pathogen and could potentially increase the resistance of the tissue [21]. It has been demonstrated that, in the acidic environment of wounded citrus fruit peel, the undissociated form of benzoic acid enters the fungal cells until the concentrations inside and outside are equal. This acidification inhibits the growth of the cells. The fall in internal pH caused by the accumulation of benzoic acid at a low external pH inhibits glycolysis, depleting the cell of ATP [28]. Furthermore, several studies have shown that preharvest applications of various GRAS salts, including sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, potassium carbonate, potassium silicate and sodium silicate, can significantly reduce fungal growth in oranges [20] and clementines [21] after cold storage.

Lemons suffer significant quality changes during postharvest storage, including WL, colour, firmness, TSS and TA [29]. Fungal activity can severely compromise the quality of lemons, leading to tissue softening, souring and changes in flavour and aroma. Furthermore, they can also promote water loss and reduce firmness, which has a negative effect on shelf-life [3]. Therefore, this experiment aimed to evaluate the effect of salts on the physicochemical attributes of fruits to ensure that its quality would not be negatively affected. The results of the first experimental season showed that preharvest application of SB and PS increased WL, although the highest values, found at 3% PS, resulted in double the WL of untreated lemons after 35 days of storage. However, no differences were found in WL with 0.5 to 1% SB and PS concentrations (Figure 2A). These results are consistent with those of [30], in which it was found that higher concentrations of PS increased WL in Nova mandarins. No differences were observed with the different SB treatments in the second season (Figure 6A), similar to results observed in oranges treated with SB after 42 days of cold storage [31]. Firmness is a critical quality parameter that was negatively affected with the highest doses of SB and PS at harvest and after storage, as shown in Figure 2B. Interestingly, the 0.1 and 0.5% SB treatments did not affect fruit firmness after storage in the second season (Figure 6B). The decrease in firmness could be linked to the toxicity of the salts, which could disrupt cell wall stability, altering water balance, interfering with calcium signalling and increasing the activity of cell wall-degrading enzymes [18]. High levels of respiration rate were observed for all treatments and number of applications. SB at 0.1% applied once (SB 1T) resulted in a similar RR compared to non-treated lemons (Figure 6C). An increase in RR has been previously observed in oranges treated with sodium bicarbonate and potassium silicate. This has been attributed to the salts’ toxicity, which compromises the ability of mitochondria to produce the energy needed for normal cellular processes, ultimately hindering energy-intensive activities like respiration [20]. The treatments were evaluated for their effect on two key juice parameters: TSS and TA, which serve as indicators of fruit maturity and consumer acceptance. In this regard, TSS increased in lemons treated with SB and PS, with a reduced difference in those treated with the lowest dose and number of applications (Figure 2E and Figure 6E). Conversely, the increase on TA observed at harvest in the Figure 2F and Figure 6F were not consistent with previous research on Barnfield oranges, where no significant differences were observed in TA between the control and treated fruits [31]. No colour changes were observed in lemons treated with SB or PS compared to the controls (Figure 2D and Figure 6D). These findings are consistent with those of previous postharvest studies on oranges [32], pitahayas [33] and cherry tomatoes [16], which also found no colour differences. Salt treatments were found to increase both TPC (Figure 3A; Figure 7A) and TAA (Figure 3B; Figure 7B) in the flavedo of lemons. These findings are particularly relevant considering that TPC is crucial for maintaining fruit quality during cold storage [25]. Furthermore, these results are supported by previous reports suggesting that salt treatments enhance the natural defence mechanisms of fruits, thereby increasing their resistance to fungal infections [32]. In particular, preharvest treatments with 3% and 4.5% potassium silicate increased the anthocyanins and TPC of nectarines [34]. It is important to highlight that both PCAs enhanced the interpretation of the results obtained in both seasons (Figure 4; Figure 8). For the first experiment, SB at 0.5% was the treatment more similar to the control in terms of the relationship between the main quality parameters of the lemons. This was associated with a reduced impact of the adverse effects of applying high salt doses. Consequently, the 0.5% SB treatment was replicated in the subsequent season, and a new 0.1% SB treatment was introduced. Overall, the second experiment revealed a clear difference between lemons treated with 0.5% SB 2T and the control group, providing evidence of the positive effects of this treatment on decay incidence and its minimisation of negative effects on fruit quality and functional properties.

5. Conclusions

In this study, lemons treated with SB exhibited significantly less fungal decay than those treated with PS. The control of fungal decay was dose-dependent: concentrations of either salt higher than 1% were less effective, a phenomenon associated with salt-induced stress. This stress promoted the over-maturation of the fruit, which negatively impacted its fruit quality parameters. Further optimisation of the treatment schedule confirmed the critical role of salt exposure. The most favourable outcomes, including effective control of fungal decay, preservation of fruit quality and enhancement of antioxidant systems, were observed in fruits that received one or two treatments. In particular, the application of 0.5% SB applied twice emerges as a promising preharvest strategy for managing fungal decay and maintaining lemon fruit quality. These findings represent a significant contribution to the lemon industry, providing an alternative to conventional fungicides and enhancing food safety while minimising environmental residue and promoting sustainable practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.-P., V.S.-E., P.J.Z. and M.J.G.; methodology, M.G.-B.; software, M.G.-B.; validation, M.G.-P., V.S.-E. and M.J.G.; formal analysis, M.G.-P. and M.G.-B.; investigation, M.G.-P. and M.G.-B.; resources, P.J.Z.; data curation, M.G.-P. and V.S.-E.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.-P. and V.S.-E.; writing—review and editing, M.G.-P., V.S.-E., M.G.-B., M.Á.B., P.J.Z. and M.J.G.; visualization, M.G.-P., V.S.-E., M.Á.B., P.J.Z. and M.J.G.; supervision, M.G.-P. and P.J.Z.; project administration, P.J.Z.; funding acquisition, P.J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Data 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/statistics/en/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Strano, M.C.; Altieri, G.; Admane, N.; Genovese, F.; Di Renzo, G.C. Advance in citrus postharvest management: Diseases, cold Storage and quality evaluation. In Citrus Pathology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L. Penicillium digitatum, Penicillium italicum (green mold, blue mold). In Postharvest Decay: Control Strategies; Bautista-Baños, S., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 45–102. ISBN 978-0-12-411552-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L. Postharvest treatments with gras salts to control fresh fruit decay. Horticulturae 2018, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S.; Norelli, J.; Liu, J.; Schena, L. Alternative management technologies for postharvest disease control: The journey from simplicity to complexity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 122, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L.; Ali, A.; Fallik, E.; Romanazzi, G. GRAS, plant- and animal-derived compounds as alternatives to conventional fungicides for the control of postharvest diseases of fresh horticultural produce. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 122, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L.; Usall, J.; Smilanick, J.L.; Aguilar, M.J.; Viñas, I. Evaluation of food additives and low-toxicity compounds as alternative chemicals for the control of Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium italicum on citrus fruit. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Aquino, S.; Fadda, A.; Barberis, A.; Palma, A.; Angioni, A.; Schirra, M. Combined effects of potassium sorbate, hot water and thiabendazole against green mould of citrus fruit and residue levels. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilanick, J.L.; Mansour, M.F.; Gabler, F.M.; Sorenson, D. Control of citrus postharvest green mold and sour rot by potassium sorbate combined with heat and fungicides. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 47, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sama, V.; Molua, E.L.; Nkongho, R.N.; Ngosong, C. Potential of sodium benzoate additive to control food-borne pathogens and spoilage microbes on cassava (Manihot esculenta) fufu and shelf-life extension. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 11, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, E.I.; Kanan, G.J.M.; Al-Batayneh, K.M.; Alhussaen, K.; Al Khateeb, W.; Qar, M.; Jacob, J.H.; Muhaidat, R.; Hegazy, M.I. Evaluation of food preservatives, low toxicity chemicals, liquid fractions of plant extracts and their combinations as alternative options for controlling citrus post-harvest green and blue moulds in vitro. Res. J. Med. Plant. 2012, 6, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L.; Smilanick, J.L.; Crisosto, C.H. Evaluation of food additives as alternative or complementary chemicals to conventional fungicides for the control of major postharvest diseases of stone fruit. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilanick, J.L.; Margosan, D.A.; Mlikota, F.; Usall, J.; Michael, I.F. Control of citrus green mold by carbonate and bicarbonate salts and the influence of commercial postharvest practices on their efficacy. Plant Dis. 1999, 83, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanlong, L.; Qiongyin, L.; Xiaoyu, L.; Tan, H.; Abdul-Nabi, J.; Caili, Z.; Hansheng, G. Effects of postharvest chitosan and potassium sorbate coating on the storage quality and fungal community of fresh jujube. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 205, 112503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, S.; Soleimani, A.; Rabiei, V.; Razavi, F. Impact of chitosan in combination with potassium sorbate treatment on chilling injury and quality attributes of pomegranate fruit during cold storage. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaiquiong, C.; Yue, Z.; Qixin, Z. Potential of acidified sodium benzoate as an alternative wash solution of cherry tomatoes: Changes of quality, background microbes, and inoculated pathogens during storage at 4 and 21°C post-washing. Food Microbiol. 2019, 82, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Gill, P.P.S.; Jawandha, S.K. Effect of sodium benzoate application on quality and enzymatic changes of pear fruits during low temperature. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 3391–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, G.M.; Baigorria, C.G.; Ramallo, A.C.; Sepulveda, M.; Ramallo, J.; Volentini, S.I.; Rapisarda, V.A.; Cerioni, L. Inhibition of the lemon brown rot causal agent Phytophthora citrophthora by low-toxicity compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3613–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramallo, A.C.; Cerioni, L.; Olmedo, G.M.; Volentini, S.I.; Ramallo, J.; Rapisarda, V.A. Control of Phytophthora sp. brown rot of lemons by pre- and postharvest applications of potassium phosphite. European J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 154, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Escolano, V.; Gutiérrez-Pozo, M.; Dobón-Suárez, A.; Zapata, P.J.; Giménez, M.J. Effect of preharvest treatments with sodium bicarbonate and potassium silicate in ‘Navel’ and ‘Valencia’ oranges to control fungal decay and maintain quality traits during cold storage. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.; Ligorio, A.; Nigro, F.; Ippolito, A. Activity of salts incorporated in wax in controlling postharvest diseases of citrus fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 65, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Pozo, M.; Serna-Escolano, V.; Giménez-Berenguer, M.; Giménez, M.J.; Zapata, P.J. The Preharvest application of essential oils (Carvacrol, Eugenol, and Thymol) reduces fungal decay in lemons. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Esplá, A.; Zapata, P.J.; Valero, D.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Díaz-Mula, H.M.; Serrano, M. Preharvest treatments with salicylates enhance nutrient and antioxidant compounds in plum at harvest and after storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 2742–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Escolano, V.; Valverde, J.M.; García-Pastor, M.E.; Valero, D.; Castillo, S.; Guillén, F.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Zapata, P.J.; Serrano, M. Pre-harvest methyl jasmonate treatments increase antioxidant systems in lemon fruit without affecting yield or other fruit quality parameters. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5035–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serna-Escolano, V.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Giménez, M.J.; Serrano, M.; García-Martínez, S.; Valero, D.; Valverde, J.M.; Zapata, P.J. Enhancing antioxidant systems by preharvest treatments with methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid leads to maintain lemon quality during cold storage. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 128044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia-Chamorro, S.A.; Palou, L.; del Río, M.Á.; Pérez-Gago, M.B. Performance of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC)-lipid edible coatings with antifungal food additives during cold storage of ‘Clemenules’ mandarins. LWT 2011, 44, 2342–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanlong, L.; Wenjing, Z.; Zhengkai, W.; Huabin, W.; Li, L.; Abdul-Nabi, J.; Caili, Z. Sodium benzoate and chitosan composite coating synergistically reduces jujube fruit decay by inhibiting pathogenic fungi and increasing fungal diversity. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-Herrero, C.; Moscoso-Ramírez, P.A.; Palou, L. Evaluation of sodium benzoate and other food additives for the control of citrus postharvest green and blue molds. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 115, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, D.; Serrano, M. Postharvest Biology and Technology for Preserving Fruit Quality; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781439802670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, J.; Ripoll, G.; Orihuel-Iranzo, B. Potassium sorbate effects on citrus weight loss and decay control. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 96, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.E.R.; de la Fuente, B.; Pérez-Gago, M.B.; Andradas, C.; Carbó, R.; Mattiuz, B.H.; Palou, L. Antifungal activity of GRAS salts against Lasiodiplodia theobromae in vitro and as ingredients of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-lipid composite edible coatings to control Diplodia sp. stem-end rot and maintain postharvest quality of citrus fruit. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 301, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.; Hussien, A. Electrolysed water and salt solutions can reduce green and blue molds while maintain the quality properties of ‘Valencia’ late oranges. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 159, 111025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaplana, R.; Alba, P.; Valencia-Chamorro, S. Sodium bicarbonate salts for the control of postharvest black rot disease in yellow pitahaya (Selenicereus megalanthus). Crop Prot. 2018, 114, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, W.; Akrimi, R.; Hajlaoui, H.; Rejeb, H.; Gogorcena, Y. Foliar fertilization of potassium silicon improved postharvest fruit quality of peach and nectarine [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] cultivars. Agriculture 2023, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.